Emotional labour

感情労働

Emotional labour

感情労働とは、相手(=顧客)に特定の精神状態を創り出すために、自分の感情を誘発し たり、逆に抑圧したりすることを職務にする、精神と感情の 協調作業を基調とする労働である。

この用語は、社会学者A・R・ホックシー ルド(Arlie Russell Hochschild, 1940-)による。感情労働の典型として表されたのは、航空機における白人女性の客室乗務員であるが、現在で は、医療者をはじめ、ファストフードの販売担当者、コールセンターの対応員、企業のクレーム処理担当者など、さまざまな生活の局面で感情労働に従事する人 たちを観察することができ る。あるいは、交渉相手の個人情報が入手できなかったり、あるいはその必要がない、私たちの日常生活の中では、感情労働は、誰しもが身につけている「作 法」の一部と言うこともできる(→これは、現代社会における「労働の女性化」ないしは「労働のジェンダーフリー化」と関係あるかもしれない。→「労働のジェンダー化」)。

アーリー・ホックシールド理論のテーゼ は、感情は社会的に構成されるものであるが、その社会の構成員が理解しているフォークセオリー=エスノサ イエンス(民族知識)としてのルールを内面化し、外部表出を管理しているということである。彼女は、感情に関して、内部に抱くものと外部に表出されるもの に齟齬があるとすると、それを修正(「感情管理」)しようとする。こ の修正には浅いレベルもの(「表層演技」)と深いレベルのもの(「深層演技」) の2種類のものがある。前者「表層演技」は、齟齬があるのを自覚したまま、それを相手に気づかれないようにする操作=「感情管理」である。他方、「深層演 技」は、心の中の対話のようなもので、つねに「正しい感情」を抱こうとする「感情管理」である。後者のものは、私(池田)にとって、神父や坊主——時には 学校の教師——などの聖職能者が言うような胡散臭いものである。しかし、彼女に言わせれば、「正しい感情」や「ほんとうの気持ち」(トリリング 1989)は、行為者がリラックスできるような私的領域では表出しやすい(私は古臭いゴフマニアン[ゴッ フマン主義者]なので、死体にも敬意をはらう人間特性からみて非現実だと思う)。そして、公的領域では、感情表出(感情管理)は、エスノサイエン ス(民族知識)としてのルールが優先しやすいことは、ゴッフマンが明らかにしたとうりである。

理論用語としての感情労働が意味するもの は、労働力商品として感情を表出したり制御することが労働者に要求されていたり、日常生活の 「普通」の 感情表出が阻害(疎外でもある)されているということである。

したがって、この用語の理論的難点は、感情の商品化の測定が果たして可能 であるのか、あるいは、感情労働に対するストレス負荷の個人的差異 を、 労働にともなう疎外と考えるかという、感情労働の負荷の測定に関わる問題である。現代社会が抱える質的な問題として、感情労働を議論する際 には何の問題も ないだろうが、感情という曖昧で、歴史的社会的文化的に相対的な概念を、量的に評価することは難しいだろう。

純粋に社会学的議論だった感情労働論が、

ビジネス管理という観点からは、労働者へのストレスマネジメントが可能なのか、あるいは労働組合が感情

労働に対する付加的な対価(賃上げ)を求めることが正当化なのかという議論に展開しやすい。また、感情労働というものが、ビジネス・グローバリゼーション

の広がりのなかで、どれだけ多文化状況に対して理論分析にとって「有効」なのか、あるいは、労務管理においてどれだけ「役に立つ」のか、ということについ

ては大いに議論の余地がある。言い方を変えると、この用語は労働者の不満の用語法、クレームメイキングの手段にもなってしまった。

もともと、「ホックシールドの感情労働論」は、社会学のゴッフマン と、マルクスを節合させるという、スリリングな議論であったが、日本国内で感情労 働を議論する場合は、その多くはジェンダー論での枠組みの話になりやすい。しかし、マルクスの『資本論』(1867,1885,1894)の時代と異な り、労働環境もジェンダーに関する社会的意味付けも変化してきたことから、先に述べた ように、現代社会における「労働の女性化」ないしは「労働のジェン ダーフリー化」から、今一度、感情労働の議論を、精査してみることも必要だと思われる。女性に感情労働がもとめられやすいのも世界的動向である。言い方を 変えると、女性の感情労働は、より「自然化」されやすい。

感情労働について考えるためには、私的価 値と公共的価値、私的疎外と公的疎外という2極から始めるのがいい。また、下の図は、パーソンズの 医師-患者関係を図式化した時に使ったものだが、当然、これらの時相の間にはさま ざまな感情労働がみられることは、明らかであろう。

| ドメイン |

私的領域(心理的領域) |

公的領域(労働あるいは社会学領域) |

| エージェント |

自己あるいは客我(Me)、我 |

社会的存在としての私あるいは主我(I)、汝 |

| パフォーマンス |

本物の自分(もちろん構成された架空のもの) |

演技(表層演技、深層演技) |

そして、ビジネス管理と感情労働の結びつ きは、ますます、高まってきている。

●感情労働の現場は、意外と多様性がある

ホックシールドは、感情を内面とは無関係に取り繕う労働を感情労働としたが、もしそうであるなら、無愛想にふるまったり、感情を押し殺すこ とも、「広義の感情労働」のはずである。ホックシールドは、ポジティブな感情をその労働概念に全面的に出しているが、『日常生活における自己提示』には、 詐欺師とサクラの関係や、シェットランド諸島における「観察されていない観察者を観察する者」の振る舞いのあり方などについても考察されている。

「同じ女性は、知り合いのAさんが、別の知り合いのBさん対して「実際に」どう考えて

いるのかを知るために、Aさんがいるにも関わらず[話はじめることを控え]Bさんが別のCさんと話し始めるまでは、様子眺めでそれを待つことがある。Bさ

んとの会話がないということ、そして彼(=Bさん)によって直接観察されていないことから、Aさんはしばしば[この人に向けられている]普段の緊張と狡猾

な企みから解放されて、彼が「実際に」Bさんに抱く感情について自由に表現することができるのである。このシェットランド島民[の女性]は、要約して言え

ば、観察されていない観察者を観察しているのだ、 と言えるのである」観察されていない観

察者を観察すること)

● 私の感情労働論批判

感情労働あるいは感情の社会学の最大の問題は、現代人の感情の動態が一望監視的に理解できるないしはその「理解」に基づいてマネジメントで

きるという西洋中心主義=自己オクシデンタリズム(self-occidentalism)ということに尽きるのではないでしょうか?(岡原 1998)

●客我(Me)と主我(I)の違い

「私が何を考えているときでも、私はそれと同時にいつも私自身、私の人格的存在を多少とも自覚している。また、同時にそれを自覚しているの

も私である。したがって私の全自我(セルフ)はいわば二重であって、半ば知者であり半ば被知者であり、半ば客体であり半ば主体であって、その中に識別でき

る2つの側面がある。この二側面を簡単に言い表すために一つを客我(Me)、他を主我(I)と呼ぶことにする」(ジェームズ 1992:245)

★キャバクラ嬢の感情労働(→出典「新宿タワマン殺人事件」)

「キャ バクラ嬢が隣に座り、接待する。通常のキャバクラでは性的な行為などは禁止され ている。ハウスボトル(ブランデー・ウイスキー・焼酎等)は飲み放題であることが多い。料金は時間制でのセット料金である。他に指名料、キャストドリンク 等が発生する。店舗によっては「テーブルチャージ・税金・サービス料」等として5~20%程度割増となることがある。延長確認の有無は店舗によって異な る。また店外デートについては「同伴」出勤や店の閉店後にキャバクラ嬢と客で酒などを飲みに行ったりカラオケに行ったりする「アフター」がある。同伴出勤 の回数はキャバクラ嬢の給与体系の中に組み込まれており、同伴回数にノルマを設けている店なども存在する。また同伴回数と指名(本指名・場内指名)本数や ドリンクの売り上げ等は給与にインセンティブとして上乗せされる。客の指名が被った場合には一方の客に指名以外のキャストが付くが、これをヘルプという。 どの客にどのキャストを付けるかといったことも重要なホール業務となってくる」

「女 性従業員(キャバ嬢・キャスト)には「笑顔での応対」や「相手に話を合わせながらいい気分でお酒を飲ませる」など、感情労働を 求められる。」

★ウィキペディア「感情労働」入門

| Emotional labor is

the act of managing one's own emotions and the emotions of others to

meet job or relationship expectations. It requires the capacity to

manage and produce a feeling to fulfill the emotional requirements of a

job.[1][2] More specifically, workers are expected to regulate their

personas during interactions with customers, co-workers, clients, and

managers. This includes analysis and decision-making in terms of the

expression of emotion, whether actually felt or not, as well as its

opposite: the suppression of emotions that are felt but not expressed.

This is done so as to produce a certain feeling in the customer or

client that will allow the company or organization to succeed.[1] Roles that have been identified as requiring emotional labor include those involved in education, public administration, law, childcare, health care, social work, hospitality, media, advocacy, aviation and espionage.[3][4] As particular economies move from a manufacturing to a service-based economy, more workers in a variety of occupational fields are expected to manage their emotions according to employer demands when compared to sixty years ago.[citation needed] |

感情労働とは、仕事や人間関係の期待に応えるために、自身の感情や他者

の感情を管理する行為である。仕事における感情的要求を満たすために、感情を管理し生み出す能力が求められる。[1][2]

具体的には、労働者は顧客、同僚、クライアント、管理職とのやり取りにおいて、自身のペルソナを調整することが求められる。これには、実際に感じているか

否かにかかわらず感情を表現する判断と分析、そしてその反対である、感じているが表現しない感情の抑制が含まれる。これは、企業や組織の成功につながるよ

う、顧客やクライアントに特定の感情を生み出すために行われる。[1] 感情労働が必要とされる役割として特定されているものには、教育、公共行政、法律、保育、医療、社会福祉、接客、メディア、擁護活動、航空、諜報活動など が含まれる。[3][4] 特定の経済が製造業中心からサービス業中心へと移行するにつれ、様々な職業分野の労働者が、雇用主の要求に応じて感情を管理することが、60年前と比べて より多く期待されるようになっている。[出典が必要] |

Definition A waitress at a restaurant is expected to do emotional labor, such as smiling and expressing positive emotion towards customers The sociologist Arlie Hochschild provided the first definition of emotional labor, which is displaying certain emotions to meet the requirements of a job.[1] The related term emotion work refers to displaying emotions you don't feel within the private sphere of one's home or interactions with family and friends. Hochschild identified three emotion regulation strategies: cognitive, bodily, and expressive.[5] Within cognitive emotion work, one attempts to change images, ideas, or thoughts in hopes of changing the feelings associated with them.[5] For example, one may associate a family picture with feeling happy and think about said picture whenever attempting to feel happy. Within bodily emotion work, one attempts to change physical symptoms in order to create a desired emotion.[5] For example, one may attempt deep breathing in order to reduce anger. Within expressive emotion work, one attempts to change expressive gestures to change inner feelings, such as smiling when trying to feel happy.[5] While emotion work happens within the private sphere, emotional labor is emotion management within the workplace according to employer expectations. Jobs involving emotional labor are defined as those that: 1. require face-to-face or voice-to-voice contact with the public. 2. require the worker to produce an emotional state in another person. 3. allow the employer, through training and supervision, to exercise a degree of control over the emotional activities of employees.[1] Hochschild (1983) argues that within this commodification process, service workers are estranged from their own feelings in the workplace.[1] |

定義 レストランのウェイトレスは、顧客に対して笑顔を見せたり前向きな感情を表現したりするといった感情労働が求められる 社会学者アーリー・ホックシールドは、感情労働を「仕事の要求を満たすために特定の感情を示すこと」と初めて定義した[1]。関連用語である感情作業と は、家庭内の私的領域や家族・友人との交流において、実際には感じていない感情を表現することを指す。ホックシールドは三つの感情調節戦略を特定した:認 知的、身体的、表現的である。[5] 認知的感情労働では、イメージや考えを変えようとし、それに関連する感情を変えようとする。[5] 例えば、家族写真を幸せな気分と結びつけ、幸せを感じたい時にその写真を思い浮かべる。身体的感情労働では、望ましい感情を生み出すために身体的症状を変 えようとする。[5] 例えば、怒りを抑えるために深呼吸を試みる場合がある。表現的感情労働では、内面の感情を変えるために表現的なジェスチャーを変える試みが行われる。例え ば、幸せを感じようとする時に笑顔を作るような場合だ。[5] 感情労働が私的領域で行われるのに対し、感情労働とは雇用主の期待に沿った職場内での感情管理を指す。感情労働を伴う職務は以下のように定義される: 1. 一般客との対面または音声による接触を必要とする。 2. 労働者が他の人格に特定の感情状態を引き起こすことを要求される。 3. 雇用主が訓練や監督を通じて、従業員の感情活動に対して一定の統制を行使できる。[1] ホックシールド(1983)は、この商品化プロセスにおいて、サービス業従事者は職場で自らの感情から疎外されると論じている。[1] |

| Alternate usage The term has been applied in modern contexts to refer to household tasks, specifically unpaid labor that is often expected of women, e.g. having to remind their partner of chores.[6] The term can also refer to informal counseling, such as providing advice to a friend or helping someone through a breakup.[7] When Hochschild was interviewed about this shifting usage, she described it having undergone concept creep, expressing that it made the concept blurrier and was sometimes being applied to things that were simply just labor, although how carrying out this labor made a person feel could make it emotional labor as well.[8] |

別の用法 この用語は現代の文脈では家事労働、特に女性に期待される無償労働を指すようになった。例えばパートナーに家事の催促をしなければならないことなどだ [6]。また友人への助言や別れの相談に乗るといった非公式なカウンセリングを指すこともある。[7] この用法の変化についてホックシールドがインタビューを受けた際、彼女は概念の拡散(コンセプト・クリープ)が生じたと説明した。これにより概念が曖昧に なり、単なる労働に過ぎない事柄にも適用されることがあると述べた。ただし、この労働を行うことが人格にどのような感情をもたらすかによって、感情労働と 見なされる可能性もあると付け加えた。[8] |

| Determinants 1. Societal, occupational, and organizational norms. For example, empirical evidence indicates that in typically "busy" stores there is more legitimacy to express negative emotions than there is in typically "slow" stores, in which employees are expected to behave in accordance with the display rules.[9] Hence, the emotional culture to which one belongs influences the employee's commitment to those rules.[10] 2. Dispositional traits and inner feeling on the job; such as employees' emotional expressiveness, which refers to the capability to use facial expressions, voice, gestures, and body movements to transmit emotions;[11] or employees' level of career identity (the importance of the career role to self-identity), which allows them to express the organizationally-desired emotions more easily (because there is less discrepancy between expressed behavior and emotional experience when engaged in their work).[12] 3. Supervisory regulation of display rules; Supervisors are likely to be important definers of display rules at the job level, given their direct influence on workers' beliefs about high-performance expectations. Moreover, supervisors' impressions of the need to suppress negative emotions on the job influence the employees' impressions of that display rule.[13] |

決定要因 1. 社会・職業・組織の規範。例えば、実証研究によれば、典型的な「忙しい」店舗では、典型的な「閑散とした」店舗よりも、ネガティブな感情を表現する正当性 が高い。閑散店舗では従業員は展示ルールに沿った行動が求められる。[9] したがって、所属する感情文化は、従業員のルールへの順守姿勢に影響する。[10] 2. 職務における気質的特性と内面的感情。例えば従業員の感情表現性(表情・声・身振り・動作を用いて感情を伝達する能力)[11]や、キャリアアイデンティ ティのレベル(キャリア役割が自己同一性に占める重要性)が挙げられる。キャリアアイデンティティが高い従業員は、職務遂行時(表情と感情体験の乖離が少 ないため)に組織が求める感情をより容易に表現できる[12]。(仕事に従事している時は、表現された行動と感情体験の間に矛盾が少ないため)。[12] 3. 表示ルールの監督的規制;監督者は、従業員の高業績期待に関する信念に直接影響を与えることから、職務レベルにおける表示ルールの重要な定義者となり得 る。さらに、監督者が職場でネガティブな感情を抑える必要性について抱く印象は、従業員がその表示ルールについて抱く印象に影響を与える。[13] |

| Surface and deep acting Arlie Hochschild's foundational text divided emotional labor into two components: surface acting and deep acting.[1] Surface acting occurs when employees display the emotions required for a job without changing how they actually feel.[1] Deep acting is an effortful process through which employees change their internal feelings to align with organizational expectations, producing more natural and genuine emotional displays.[14] Although the underlying processes differ, the objective of both is typically to show positive emotions, which are presumed to impact the feelings of customers and bottom-line outcomes (e.g. sales, positive recommendations, and repeat business).[14][15][16] However, research generally has shown surface acting is more harmful to employee health.[17][18][19] Without a consideration of ethical values, the consequences of emotional work on employees can easily become negative. Business ethics can be used as a guide for employees on how to present feelings that are consistent with ethical values, and can show them how to regulate their feelings more easily and comfortably while working.[20] |

表層演技と深層演技 アーリー・ホックシールドの基礎的な著作は、感情労働を二つの要素に分類した:表層演技と深層演技である。[1] 表層演技とは、従業員が実際の感情を変えることなく、職務に必要な感情を表現する行為を指す。[1] 深層演技は、従業員が組織の期待に沿うよう内面の感情を変化させる労力を伴うプロセスであり、より自然で本物の感情表現を生み出す。[14] 基礎となるプロセスは異なるが、両者の目的は通常、顧客の感情や最終的な成果(売上、好意的な推薦、リピート購入など)に影響を与えると想定される肯定的 な感情を示すことにある。[14][15][16] しかし研究では、表層演技の方が従業員の健康に有害であることが一般的に示されている。[17][18][19] 倫理的価値を考慮しなければ、感情労働が従業員に及ぼす影響は容易に悪化する。ビジネス倫理は、倫理的価値に沿った感情の表現方法を従業員に指針として示 し、業務中に感情をより容易かつ快適に調節する方法を教えることができる。[20] |

Careers A nurse working in a hospital is expected to express positive emotions towards patients, such as warmth and compassion. In the past, emotional labor demands and display rules were viewed as a characteristic of particular occupations, such as restaurant workers, cashiers, hospital workers, bill collectors, counselors, secretaries, and nurses. However, display rules have been conceptualized not only as role requirements of particular occupational groups, but also as interpersonal job demands, which are shared by many kinds of occupations.[13] Teachers Zhang et al. (2019) looked at teachers in China, using questionnaires the researchers asked about their teaching experience and their interaction with the children and their families.[21] According to numerous studies, early childhood education is important to a child's development, which can have an effect on the amount of emotional labor a teacher must perform, and that the teacher's emotional labor has an effect on the children. Zhang et al. (2019) found that surface acting was used significantly less than deep and natural acting in kindergarten teachers, and that early childhood teachers were less likely to fake or suppress their feelings. They also found that more experienced teachers had higher levels of emotional labor, because they either had more skills to suppress their emotions, or they are less driven to use surface acting. Bill collectors In 1991, Sutton did an in-depth qualitative study into bill collectors at a collection agency.[22] He found that unlike the other jobs described here where employees need to act cheerful and concerned, bill collectors are selected and socialized to show irritation to most debtors. Specifically, the collection agency hired agents who seemed to be easily aroused. The newly hired agents were then trained on when and how to show varying emotions to different types of debtors. As they worked at the collection agency, they were closely monitored by their supervisors to make sure that they frequently conveyed urgency to debtors. Bill collectors' emotional labor consists of not letting angry and hostile debtors make them angry and to not feel guilty about pressuring friendly debtors for money.[22] They coped with angry debtors by publicly showing their anger or making jokes when they got off the phone.[22] They minimized the guilt they felt by staying emotionally detached from the debtors.[22] Childcare workers  Childcare worker at a daycare in Nigeria The skills involved in childcare are often viewed as innate to women, making the components of childcare invisible.[23][24] However, a number of scholars have not only studied the difficulty and skill required for childcare, but also suggested that the emotional labor of childcare is unique and needs to be studied differently.[24][25][26][27] Performing emotional labor requires the development of emotional capital, and that can only be developed through experience and reflection.[25] Through semi-structured interviews, Edwards (2016) found that there were two components of emotional labor in childcare in addition to Hochschild's original two: emotional consonance and suppression.[1][27] Edwards (2016) defined suppression as hiding emotion and emotional consonance as naturally experiencing the same emotion that one is expected to feel for the job.[27] Caring for those with special needs [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2025) Caring for those with special needs may be paid or unpaid work. |

キャリア 病院で働く看護師は、患者に対して温かさや思いやりといった前向きな感情を示すことが求められる。 かつて感情労働の要求と感情表現のルールは、レストラン従業員、レジ係、病院職員、債権回収担当者、カウンセラー、秘書、看護師といった特定の職業の特徴 と見なされていた。しかし、感情表現のルールは特定の職業グループの役割要件としてだけでなく、多くの職種に共通する対人関係の職務要求としても概念化さ れている。[13] 教師 Zhangら(2019)は中国の教師を対象に調査を行い、研究者が作成した質問票を用いて、教師の教育経験や児童・家族との関わりについて尋ねた。 [21] 多くの研究によれば、幼児教育は子どもの発達に重要であり、これは教師が遂行すべき感情労働の量に影響を与え得る。また教師の感情労働は子どもたちに影響 を及ぼす。Zhangら(2019)は、幼稚園教諭において表面演技が深層演技や自然演技より有意に少なく、幼児教育者が感情を偽装・抑制する傾向が低い ことを発見した。また、経験豊富な教師ほど感情労働のレベルが高いことも判明した。これは感情を抑制するスキルが高いか、あるいは表面演技を用いる動機が 弱いからである。 債権回収担当者 1991年、サットンは債権回収会社の回収担当者について詳細な質的研究を行った[22]。ここで述べた他の職種が従業員に陽気さや気遣いを求めるのとは 異なり、債権回収業者は大半の債務者に対して苛立ちを示すよう選抜・社会化されている。具体的には、回収会社は興奮しやすい傾向のある担当者を採用した。 新入社員はその後、債務者のタイプに応じて異なる感情をいつ・どのように示すか訓練を受けた。勤務中は上司による厳重な監視下に置かれ、債務者に対して頻 繁に緊急性を伝えるよう徹底された。 債権回収業者の感情労働とは、怒りや敵意を示す債務者に自らが怒らされないこと、友好的な債務者から金銭を要求する際に罪悪感を抱かないことにある [22]。怒る債務者への対処法は、公の場で怒りを露わにするか、電話を切った後に冗談を言うことだった[22]。債務者との感情的距離を保つことで、感 じる罪悪感を最小限に抑えていた。[22] 保育従事者  ナイジェリアの保育施設で働く保育士 保育に関わる技能は、しばしば女性に先天的に備わっているものと見なされ、保育の構成要素は見えなくなる。[23][24] しかし、多くの研究者は保育の困難さや必要な技能を研究しただけでなく、保育の感情労働は独特であり、異なる方法で研究されるべきだと示唆している。 [24][25][26][27] 感情労働を遂行するには感情資本の育成が必要であり、それは経験と内省を通じてのみ培われる。[25] エドワーズ(2016)は半構造化インタビューにより、ホックシールドの提唱した感情労働の二要素(感情共鳴と感情抑制)に加え、保育における感情労働に はさらに二つの要素が存在することを明らかにした。[1][27] エドワーズ(2016)は、感情の抑制を「感情を隠すこと」、感情の調和を「仕事において期待される感情を自然に共有すること」と定義した。[27] 特別な支援を必要とする人々のケア [icon] この節は拡充が必要です。編集して内容を充実させましょう。(2025年5月) 特別な支援を必要とする人々のケアは、有償または無償の労働である場合がある。 |

| Food-industry workers Wait staff  A waitress taking an order in an American restaurant In her 1991 study of waitresses in Philadelphia, Paules examines how these workers assert control and protect their self identity during interactions with customers. In restaurant work, Paules argues, workers' subordination to customers is reinforced through "cultural symbols that originate from deeply rooted assumptions about service work." Because the waitresses were not strictly regulated by their employers, waitresses' interactions with customers were controlled by the waitresses themselves. Although they are stigmatized by the stereotypes and assumptions of servitude surrounding restaurant work, the waitresses studied were not negatively affected by their interactions with customers. To the contrary, they viewed their ability to manage their emotions as a valuable skill that could be used to gain control over customers. Thus, the Philadelphia waitresses took advantage of the lack of employer-regulated emotional labor in order to avoid the potentially negative consequences of emotional labor.[28] Though Paules highlights the positive consequences of emotional labor for a specific population of waitresses, other scholars have also found negative consequences of emotional labor within the waitressing industry. Through eighteen months of participant observation research, Bayard De Volo (2003) found that casino waitresses are highly monitored and monetarily bribed to perform emotional labor in the workplace.[29] Specifically, Bayard De Volo (2003) argues that through a sexualized environment and a generous tipping system, both casino owners and customers control waitresses' behavior and appearance for their own benefit and pleasure. Even though the waitresses have their own forms of individual and collective resistance mechanisms, intense and consistent monitoring of their actions by casino management makes it difficult to change the power dynamics of the casino workplace.[29] Fast-food employees By using participant observation and interviews, Leidner (1993) examines how employers in fast food restaurants regulate workers' interactions with customers.[30] According to Leidner (1993), employers attempt to regulate workers' interactions with customers only under certain conditions. Specifically, when employers attempt to regulate worker–customer interactions, employers believe that "the quality of the interaction is important to the success of the enterprise", that workers are "unable or unwilling to conduct the interactions appropriately on their own", and that the "tasks themselves are not too complex or context-dependent."[30] According to Leidner (1993), regulating employee interactions with customers involves standardizing workers' personal interactions with customers. At the McDonald's fast food restaurants in Leidner's (1993) study, these interactions are strictly scripted, and workers' compliance with the scripts and regulations are closely monitored.[30] Along with examining employers' attempts to regulate employee–customer interactions, Leidner (1993) examines how fast-food workers' respond to these regulations.[30] According to Leidner (1993), meeting employers' expectations requires workers to engage in some form of emotional labor. For example, McDonald's workers are expected to greet customers with a smile and friendly attitude independent of their own mood or temperament at the time. Leidner (1993) suggests that rigid compliance with these expectations is at least potentially damaging to workers' sense of self and identity. However, Leidner (1993) did not see the negative consequences of emotional labor in the workers she studied. Instead, McDonald's workers attempted to individualize their responses to customers in small ways. Specifically, they used humor or exaggeration to demonstrate their rebellion against the strict regulation of their employee–customer interactions.[30] |

食品産業労働者 接客係  アメリカのレストランで注文を取るウェイトレス 1991年のフィラデルフィアにおけるウェイトレス研究で、ポーレスはこれらの労働者が顧客とのやり取りの中で、いかに支配権を主張し自己アイデンティ ティを守るかを検証している。レストラン業務において、従業員の顧客への従属関係は「サービス労働に関する根深い前提から生まれた文化的象徴」によって強 化されるとポールズは主張する。ウェイトレスは雇用主による厳格な規制を受けていなかったため、顧客とのやり取りは彼女たち自身によって制御されていた。 レストラン業務を取り巻く従属的なステレオタイプや前提によって汚名を着せられてはいたが、調査対象のウェイトレスたちは顧客とのやり取りによって悪影響 を受けることはなかった。むしろ彼女たちは、感情を管理する能力を顧客を掌握する手段として有用なスキルと見なしていた。つまりフィラデルフィアのウェイ トレスたちは、雇用主による感情労働の規制が欠如している状況を利用し、感情労働がもたらす潜在的な悪影響を回避していたのである。[28] ポーレスが特定のウェイトレス集団における感情労働の好影響を強調する一方で、他の研究者たちはウェイトレス業界における感情労働の負の影響も指摘してい る。ベイヤード・デ・ヴォロ(2003)は18ヶ月にわたる参与観察研究を通じ、カジノのウェイトレスが職場で感情労働を行うよう厳しく監視され、金銭的 誘惑を受けていることを明らかにした[29]。具体的には、性的要素の強い環境と寛大なチップ制度を通じて、カジノ経営者と顧客双方が自らの利益と快楽の ためにウェイトレスの行動や外見を支配していると論じている。ウェイトレスたちが個人や集団としての抵抗メカニズムを持つにもかかわらず、カジノ経営陣に よる行動への強固かつ継続的な監視が、カジノ職場の力関係を変えることを困難にしている。[29] ファストフード従業員 参与観察とインタビューを用い、Leidner(1993)はファストフード店における雇用主が従業員と顧客の相互作用をどのように規制するかを検証し た。[30] ライドナー(1993)によれば、雇用主が従業員と顧客の相互作用を規制しようとするのは特定の条件下でのみである。具体的には、雇用主が従業員と顧客の 相互作用を規制しようとする場合、雇用主は「相互作用の質が事業の成功に重要である」と信じ、「従業員は自ら適切に相互作用を行うことができない、あるい は行おうとしない」と考えており、「タスク自体が複雑すぎず、文脈依存的でもない」と認識している。[30] Leidner(1993)によれば、従業員と顧客の交流を規制するとは、従業員の顧客に対する個人的な交流を標準化することを意味する。Leidner (1993)の研究対象となったマクドナルドのファストフード店では、こうした交流は厳格に台本化されており、従業員が台本や規則に従うかどうかは厳しく 監視されている。[30] 従業員と顧客の相互作用を規制しようとする雇用主の試みを検証するとともに、Leidner(1993)は、ファストフード従業員がこれらの規制にどう対 応するかも検討している。[30] Leidner(1993)によれば、雇用主の期待に応えるためには、従業員は何らかの形の感情労働に従事する必要がある。例えば、マクドナルドの従業員 は、その時の自身の気分や気質に関係なく、笑顔と友好的な態度で顧客に挨拶することが期待されている。Leidner(1993)は、こうした期待への硬 直的な順守が、少なくとも潜在的には労働者の自己認識やアイデンティティを損なう可能性があると示唆している。しかしLeidner(1993)が調査し た労働者には、感情労働の負の帰結は見られなかった。代わりにマクドナルドの従業員は、顧客対応を些細な方法で個別化しようとしていた。具体的には、ユー モアや誇張を用いて、従業員と顧客の交流に対する厳格な規制への反抗を示していたのである。[30] |

| Physicians According to Larson and Yao (2005), empathy should characterize physicians' interactions with their patients because, despite advancement in medical technology, the interpersonal relationship between physicians and patients remains essential to quality healthcare.[31] Larson and Yao (2005) argue that physicians consider empathy a form of emotional labor. Specifically, according to Larson and Yao (2005), physicians engage in emotional labor through deep acting by feeling sincere empathy before, during, and after interactions with patients. On the other hand, Larson and Yao (2005) argue that physicians engage in surface acting when they fake empathic behaviors toward the patient. Although Larson and Yao (2005) argue that deep acting is preferred, physicians may rely on surface acting when sincere empathy for patients is impossible. Overall, Larson and Yao (2005) argue that physicians are more effective and enjoy more professional satisfaction when they engage in empathy through deep acting due to emotional labor.[31] Police work According to Martin (1999), police work involves substantial amounts of emotional labor by officers, who must control their own facial and bodily displays of emotion in the presence of other officers and citizens.[32] Although policing is often viewed as stereotypically masculine work that focuses on fighting crime, policing also requires officers to maintain order and provide a variety of interpersonal services. For example, police must have a commanding presence that allows them to act decisively and maintain control in unpredictable situations while having the ability to actively listen and talk to citizens. According to Martin (1999), a police officer who displays too much anger, sympathy, or other emotion while dealing with danger on the job will be viewed by other officers as someone unable to withstand the pressures of police work, due to the sexist views of many police officers.[32] While being able to balance this self-management of emotions in front of other officers, police must also assertively restore order and use effective interpersonal skills to gain citizen trust and compliance. Ultimately, the ability of police officers to effectively engage in emotional labor affects how other officers and citizens view them.[32] Public administration Many scholars argue that the amount of emotional work required between all levels of government is greatest on the local level. It is at the level of cities and counties that the responsibility lies for day to day emergency preparedness, firefighters, law enforcement, public education, public health, and family and children's services. Citizens in a community expect the same level of satisfaction from their government, as they receive in a customer service-oriented job. This takes a considerate amount of work for both employees and employers in the field of public administration. Mastracci and Adams (2017) looks at public servants and how they may be at risk of being alienated because of their unsupported emotional labor demands from their jobs. This can cause surface acting and distrust in management.[33] There are two comparisons that represent emotional labor within public administration, "Rational Work versus Emotion Work", and "Emotional Labor versus Emotional Intelligence."[34] Performance Many scholars argue that when public administrators perform emotional labor, they are dealing with significantly more sensitive situations than employees in the service industry. The reason for this is because they are on the front lines of the government, and are expected by citizens to serve them quickly and efficiently. When confronted by a citizen or a co-worker, public administrators use emotional sensing to size up the emotional state of the citizen in need. Workers then take stock of their own emotional state in order to make sure that the emotion they are expressing is appropriate to their roles. Simultaneously, they have to determine how to act in order to elicit the desired response from the citizen as well as from co-workers. Public Administrators perform emotional labor through five different strategies: Psychological First Aid, Compartments and Closets, Crazy Calm, Humor, and Common Sense.[35] Definition: rational work vs. emotion work According to Mary Guy, Public administration does not only focus on the business side of administration but on the personal side as well. It is not just about collecting the water bill or land ordinances to construct a new property, it is also about the quality of life and sense of community that is allotted to individuals by their city officials. Rational work is the ability to think cognitively and analytically, while emotional work means to think more practically and with more reason.[36] Definition: intelligence vs. emotional intelligence Knowing how to suppress and manage one's own feelings is known as emotional intelligence. The ability to control one's emotions and to be able to do this at a high level guarantees one's own ability to serve those in need. Emotional intelligence is performed while performing emotional labor, and without one the other can not be there.[37] |

医師 ラーソンとヤオ(2005)によれば、医療技術の進歩にもかかわらず、医師と患者の間の対人関係は質の高い医療に不可欠であるため、医師の患者との関わり には共感性が求められる。[31] ラーソンとヤオ(2005)は、医師が共感を感情労働の一形態と捉えていると論じている。具体的には、ラーソンとヤオ(2005)によれば、医師は患者と の関わり前・中・後に真摯な共感を抱くという深層演技を通じて感情労働を行う。一方で、医師が患者に対して共感的な行動を装う場合、それは表層演技にあた るという。ラーソンとヤオ(2005)は、深い演技が望ましいと主張しているが、医師は患者に対して誠実な共感が不可能な場合には、表面的な演技に頼るこ ともある。全体として、ラーソンとヤオ(2005)は、医師は感情労働による深い演技を通じて共感を行う場合、より効果的で、より専門的な満足感を得られ ると主張している。[31] 警察の仕事 マーティン(1999)によれば、警察の仕事は、他の警官や市民の前で自分の表情や身体の動きによる感情表現をコントロールしなければならない警官によ る、かなりの量の感情労働を伴う。[32] 警察の仕事は、犯罪との戦いに焦点を当てた、ステレオタイプ的な男性的な仕事とよく見なされるが、警察の仕事は、秩序を維持し、さまざまな対人サービスを 提供することも警官に要求する。例えば、警察官は、市民に積極的に耳を傾け、話をする能力を持ちながら、予測不可能な状況でも決断力を持って行動し、統制 を維持できる威厳のある存在でなければならない。マーティン(1999)によれば、職務上の危険に対処する際に、怒りや同情、その他の感情を過度に表に出 す警察官は、多くの警察官の性差別的な見方により、警察業務のプレッシャーに耐えられない人物として他の警察官から見なされる。[32] 他の警官の前で感情を自己管理しながら、警察は断固として秩序を回復し、効果的な対人スキルを用いて市民の信頼と協力を得なければならない。結局のとこ ろ、警察官が感情労働に効果的に取り組む能力は、他の警官や市民が彼らをどのように見るかに影響する。[32] 行政 多くの学者は、あらゆるレベルの政府間で必要とされる感情労働の量は、地方レベルで最も大きいと主張している。日常的な緊急事態対応、消防、法執行、公教 育、公衆衛生、家族・児童サービスといった責任は、市や郡のレベルに存在する。地域社会の市民は、顧客サービス志向の職場で受けるのと同等の満足度を政府 に求める。これは公共行政分野の従業員と雇用主双方にとって、かなりの労力を要する。MastracciとAdams(2017)は、公務員が職務上の感 情労働の要求に対して支援を得られず疎外されるリスクについて考察している。これは表層演技や管理層への不信感を引き起こしうる[33]。行政における感 情労働を表す二つの比較概念として、「合理的労働対感情労働」と「感情労働対感情知能」がある[34]。 パフォーマンス 多くの研究者は、公共行政担当者が感情労働を行う際、サービス業の従業員よりもはるかに繊細な状況に対処していると主張する。その理由は、彼らが政府の最 前線に立っており、市民から迅速かつ効率的なサービス提供を期待されているためだ。市民や同僚と対峙する際、公共行政担当者は感情的感知を用いて、支援を 必要とする市民の感情状態を測る。その後、自身の感情状態を点検し、表現する感情が役割に適っているか確認する。同時に、市民や同僚から望ましい反応を引 き出すための行動方針を決定しなければならない。公共行政担当者は五つの戦略で感情労働を遂行する:心理的応急処置、区分けと隠蔽、異常な平静、ユーモ ア、常識である。[35] 定義:合理的労働 vs 感情労働 メアリー・ガイによれば、公共行政は管理業務のビジネス面だけでなく、個人的側面にも焦点を当てる。水道料金の徴収や新築物件の土地規律制定だけでなく、 市職員が個人に提供する生活の質や共同体意識も含まれる。合理的労働とは認知的・分析的に思考する能力であり、感情的労働とはより実践的かつ理性的思考を 意味する。[36] 定義:知性 vs. 感情的知性 自身の感情を抑制し管理する方法を理解することを感情的知性と呼ぶ。感情を制御する能力、そしてこれを高度に行う能力は、困っている人々への奉仕能力を保証する。感情的知性は感情労働を行う過程で発揮され、一方がなければ他方も存在し得ない。[37] |

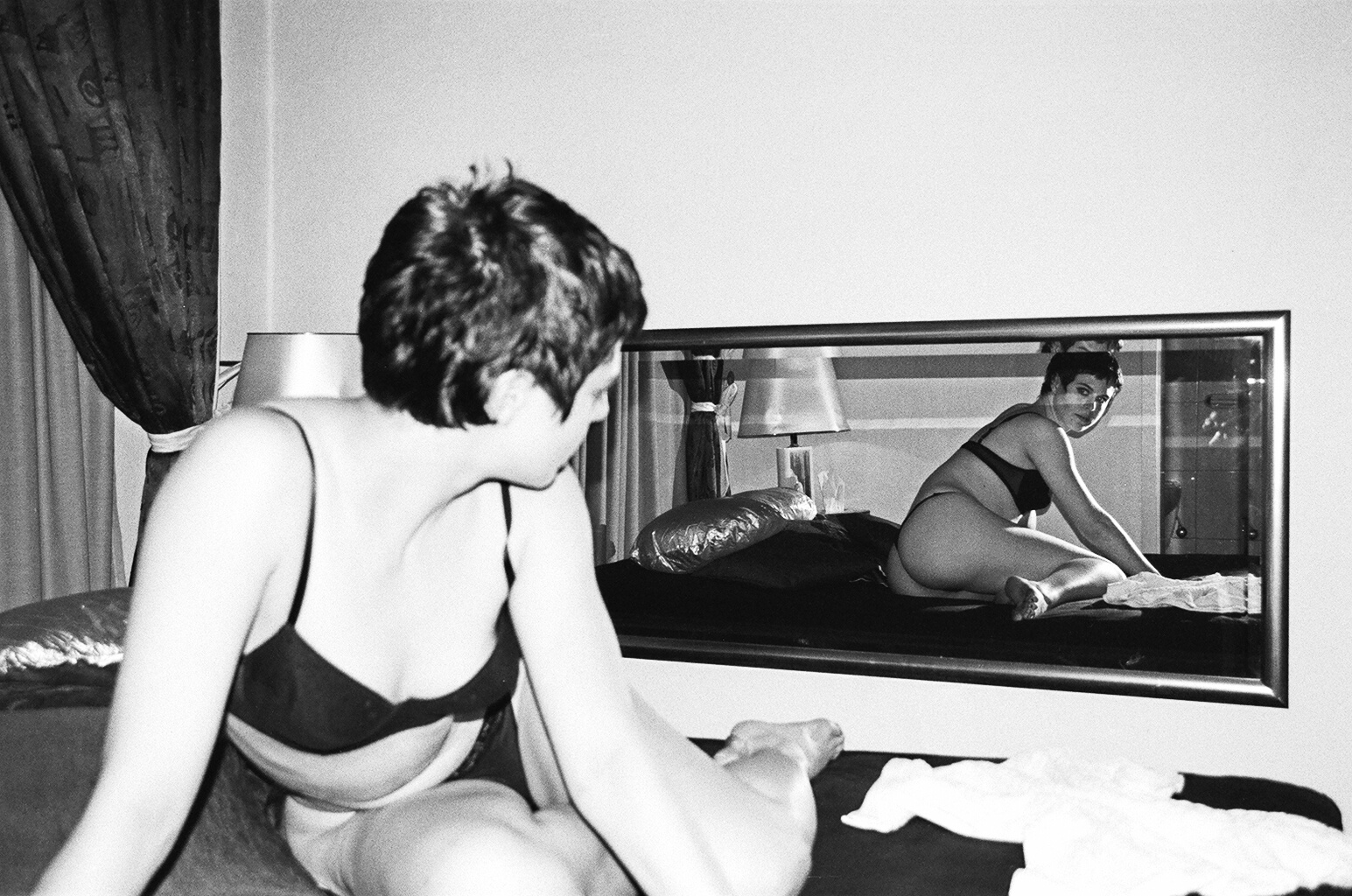

| Sex work This section is an excerpt from Sex work § Emotional labor.[edit] Emotional labor is an essential part of many service jobs, including many types of sex work. Through emotional labor sex workers engage in different levels of acting known as surface acting and deep acting. These levels reflect a sex worker's engagement with the emotional labor. Surface acting occurs when the sex worker is aware of the dissonance between their authentic experience of emotion and their managed emotional display. In contrast deep acting occurs when the sex worker can no longer differentiate between what is authentic and what is acting; acting becomes authentic.[38]  A sex worker in Berlin in 2001 Sex workers engage in emotional labor for many different reasons. First, sex workers often engage in emotional labor to construct performances of gender and sexuality.[39][40][41] These performances frequently reflect the desires of a clientele which is mostly composed of heterosexual men. In the majority of cases, clients value women who they perceive as normatively feminine. For women sex workers, achieving this perception necessitates a performance of gender and sexuality that involves deference to clients and affirmation of their masculinity, as well as physical embodiment of traditional femininity.[39][42] The emotional labor involved in sex work may be of a greater significance when race differences are involved. For instance Mistress Velvet, a black, femme dominatrix, advertises herself using her most fetishized attributes. She makes her clients, who are mostly white heterosexual men, read Black feminist theory before their sessions. This allows the clients to see why their participation, as white heterosexual men, contributes to the fetishization of black women.[43] Both within sex work and in other types of work, emotional labor is gendered in that women are expected to use it to construct performances of normative femininity, whereas men are expected to use it to construct performances of normative masculinity.[38] In both cases, these expectations are often met because this labor is necessary to maximizing monetary gain and potentially to job retention. Indeed, emotional labor is often used as a means to maximize income. It fosters a better experience for the client and protects the worker thus enabling the worker to make the most profit.[39][40][44] In addition, sex workers often engage in emotional labor as a self-protection strategy, distancing themselves from the sometimes emotionally volatile work.[45][40] Finally, clients often value perceived authenticity in their transactions with sex workers; thus, sex workers may attempt to foster a sense of authentic intimacy.[39][44] Some scholars note that expectations surrounding emotional labour can also intersect with broader social, cultural, and institutional contexts that shape how sex workers’ labour is understood. |

性産業 この節は「性産業 § 感情労働」からの抜粋である。[編集] 感情労働は多くのサービス業、特に様々な形態の性産業において不可欠な要素だ。性産業従事者は感情労働を通じて、表面演技と深層演技と呼ばれる異なるレベ ルの演技を行う。これらのレベルは、性産業従事者が感情労働にどの程度関与しているかを反映している。表層演技は、性労働者が自身の真の感情体験と管理さ れた感情表現の間の不協和を自覚している時に生じる。対照的に深層演技は、性労働者がもはや本物と演技の区別がつかなくなった時に生じる。演技が本物とな るのだ。[38]  2001年ベルリンの性労働者 性労働者が感情労働に従事する理由は様々である。第一に、性労働者はしばしばジェンダーや性的指向のパフォーマンスを構築するために感情労働を行う。 [39][40][41] こうしたパフォーマンスは、主に異性愛男性で構成される顧客層の欲望を反映していることが多い。大半の場合、顧客は規範的に女性的と認識される女性を重視 する。女性性労働者にとって、この認識を得るには、顧客への従順さや彼らの男性性の肯定、そして伝統的な女性性の身体的体現を含む、ジェンダーとセクシュ アリティのパフォーマンスが必要となる。[39] [42] 性産業における感情労働は、人種の差異が関わる場合、より重大な意味を持つ。例えば黒人でフェムなドミナトリックスであるミストレス・ベルベットは、自身 の最もフェティッシュ化された特質を用いて宣伝する。彼女は主に白人異性愛男性であるクライアントに、セッション前に黒人フェミニズム理論を読ませる。こ れによりクライアントは、白人異性愛男性としての自らの関与が、黒人女性のフェティッシュ化に寄与する理由を理解するのだ。[43] 性産業内でも他の職種でも、感情労働はジェンダー化されている。つまり女性は規範的な女性性を演じるために、男性は規範的な男性性を演じるために、それぞ れ感情労働を用いることが期待されるのだ。[38] いずれの場合も、こうした期待はしばしば満たされる。なぜならこの労働は金銭的利益を最大化し、場合によっては職を維持するために必要だからだ。実際、感 情労働は収入最大化の手段として頻繁に用いられる。それはクライアントの体験を向上させ、労働者を保護することで、労働者が最大の利益を得られるようにす るのだ。[39][40][44] さらに、性労働者は自己防衛戦略として感情労働に従事し、時に感情的に不安定な仕事から距離を置く。[45][40] 最後に、顧客はセックスワーカーとの取引において「本物らしさ」を重視する傾向がある。そのためセックスワーカーは、本物の親密さを演出しようとする場合 がある。[39][44] 一部の研究者は、感情労働への期待が、セックスワーカーの労働理解を形作るより広範な社会的・文化的・制度的文脈と交差する可能性にも言及している。 |

| Gender Macdonald and Sirianna (1996) use the term "emotional proletariat" to describe service jobs in which "workers exercise emotional labor wherein they are required to display friendliness and deference to customers."[46] Because of deference, these occupations tend to be stereotyped as female jobs, independent of the actual number of women working the job. According to Macdonald and Sirianna (1996), because deference is a characteristic demanded of all those in disadvantaged structural positions, especially women, when deference is made a job requirement, women are likely to be overrepresented in these jobs. Macdonald and Sirianna (1996) claim that "[i]n no other area of wage labor are the personal characteristics of the workers so strongly associated with the nature of the work."[46] Thus, according to Macdonald and Sirianna (1996), although all workers employed within the service economy may have a difficult time maintaining their dignity and self-identity due to the demands of emotional labor, such an issue may be especially problematic for women workers.[46] Emotional labor also affects women by perpetuating occupational segregation and the gender wage gap.[47] Job segregation, which is the systematic tendency for men and women to work in different occupations, is often cited as the reason why women lack equal pay when compared to men. According to Guy and Newman (2004), occupational segregation and ultimately the gender wage gap can at least be partially attributed to emotional labor. Specifically, work-related tasks that require emotional work thought to be natural for women, such as caring and empathizing are requirements of many female-dominated occupations. However, according to Guy and Newman (2004), these feminized work tasks are not a part of formal job descriptions and performance evaluations: "Excluded from job descriptions and performance evaluations, the work is invisible and uncompensated. Public service relies heavily on such skills, yet civil service systems, which are designed on the assumptions of a bygone era, fail to acknowledge and compensate emotional labor." According to Guy and Newman (2004), women working in positions that require emotional labour in addition to regular work are not compensated for this additional labour because of the sexist notion that the additional labour is to be expected of them by the fact of being a woman. Guy and Azhar (2018) found that emotive expressions between sexes is affected by culture. This study found that there is variability to how women and men interpret emotive words, and specifically results showed that culture played a huge role in these gender differences.[48] |

ジェンダー マクドナルドとシリアナ(1996)は「感情プロレタリアート」という用語を用いて、サービス業の職種を説明している。そこでは「労働者は感情労働を行使 し、顧客に対して友好的で恭順な態度を示すことが求められる」[46]。恭順性が求められるため、こうした職種は実際に働く女性の数とは無関係に、女性向 けの仕事として固定観念化されがちだ。マクドナルドとシリアナ(1996)によれば、従順さは構造的に不利な立場にある者、特に女性に要求される特性であ るため、従順さが職務要件となると、女性はこうした職種に過度に集中する傾向がある。同著者らは「賃金労働の他のいかなる分野においても、労働者の個人的 特性が仕事の性質とこれほど強く結びつくことはない」と主張している。[46] したがってマクドナルドとシリアナ(1996)によれば、サービス経済で働く全ての労働者が感情労働の要求により尊厳や自己同一性を維持するのが困難な状 況にあっても、この問題は特に女性労働者にとって深刻である。[46] 感情労働は職業分離とジェンダー賃金格差を永続させることで、女性にも影響を及ぼす。[47] 男女が異なる職業に就く体系的な傾向である職業分離は、女性が男性と同等の賃金を得られない理由としてしばしば挙げられる。ガイとニューマン(2004) によれば、職業分離、ひいてはジェンダー賃金格差は少なくとも部分的に感情労働に起因するとされる。具体的には、思いやりや共感といった感情労働を必要と する業務は、女性にとって自然なものと見なされ、女性優位の職業では必須とされる。しかしGuyとNewman(2004)によれば、こうした女性化され た業務は正式な職務記述書や業績評価に含まれない:「職務記述書や業績評価から除外されるため、この労働は目に見えず、報酬も支払われない。」 公共サービスはこうしたスキルに大きく依存しているにもかかわらず、過去の時代を前提に設計された公務員制度は、感情労働を認識せず、報酬も支払わな い。」ガイとニューマン(2004)によれば、通常の業務に加えて感情労働を必要とする職位に就く女性は、この追加労働に対して報酬を受け取れない。その 理由は、追加労働は女性であるという事実によって当然期待されるべきだという性差別的な考えがあるからだ。ガイとアズハル(2018)は、性別の間の感情 表現が文化の影響を受けることを発見した。この研究では、女性と男性が感情的な言葉を解釈する方法に差異があり、特に文化がこれらのジェンダー差に大きな 役割を果たしていることが結果として示された。[48] |

| Disability [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2024) People with disabilities are becoming increasingly part of the labor force due to societal attitudes about inclusion and neoliberal pressures around reducing welfare.[example needed] Roles that require emotional labor may be more difficult for people with certain kinds of disabilities to perform.[example needed] People with disabilities may also have to put more time and energy to perform a task than non-disabled people, for instance, when they routinely encounter prejudice and stigma (as would be the case for many groups experiencing prejudice) including disability-unfriendly structures (accessibility, administrative or social). On the other hand, due to the routine experience of navigating unhelpful structures and prejudice, people with disabilities can have the dual advantage of better skills in finding ways around problems without expending emotional energy, like feeling surprised, and a more empathetic understanding of the experiences of other people with similar problems. Inclusive or unfriendly organizational culture also has an impact,[further explanation needed] and workplaces may require workers with disabilities to downplay their impairments in order to "fit in" creating an extra burden of emotional labor.[49] Most individuals will experience complex effects of their disabilities on their emotional labor in a given job role at a specified organisation. |

障害 [icon] この節は拡充が必要である。追加することで貢献できる。(2024年1月) 障害を持つ人々は、社会的な包摂の姿勢や福祉削減をめぐる新自由主義的圧力により、労働力としてますます参加している。[例が必要] 感情労働を必要とする役割は、特定の障害を持つ人々にとって遂行がより困難である可能性がある。[例が必要] 障害を持つ人々は、非障害者と比べて、あるタスクを遂行するためにより多くの時間とエネルギーを費やさなければならない場合もある。例えば、日常的に偏見 やスティグマ(多くの偏見を受ける集団が直面する状況と同様)に遭遇する場合や、障害に配慮されていない構造(アクセシビリティ、行政的・社会的構造)に 直面する場合などが挙げられる。一方で、障害を持つ人々は、役に立たない構造や偏見を日常的に経験する中で、二つの利点を獲得し得る。一つは、驚きを感じ るといった感情的エネルギーを消費せずに問題を回避する方法を見つけるスキルが向上すること。もう一つは、同様の問題を抱える他者の経験をより共感的に理 解できることである。包括的か否かの組織文化も影響を及ぼす[詳細説明が必要]。職場では、障害を持つ労働者が「周囲に溶け込む」ために障害を軽視するよ う求められる場合があり、これは感情労働の追加的負担となる[49]。ほとんどの個人は、特定の組織における特定の職務において、障害が感情労働に及ぼす 複合的な影響を経験するだろう。 |

| Implications Positive affective display in service interactions, such as smiling and conveying friendliness, are positively associated with customer positive feelings,[50] and important outcomes, such as intention to return, intention to recommend a store to others, and perception of overall service quality.[51] There is evidence that emotional labor may lead to employees' emotional exhaustion and burnout over time, and may also reduce employees' job satisfaction. That is, higher degree of using emotion regulation on the job is related to higher levels of employees' emotional exhaustion,[10] and lower levels of employees' job satisfaction.[52] There is empirical evidence that higher levels of emotional labor demands are not uniformly rewarded with higher wages. Rather, the reward is dependent on the level of general cognitive demands required by the job. That is, occupations with high cognitive demands show wage returns with increasing emotional labor demands; whereas occupations low in cognitive demands evidence a wage "penalty" with increasing emotional labor demands.[53] Additionally, innovations that increase employee empowerment — such as conversion into worker cooperatives, co-managing schemes, or flattened workplace structures — have been found to increase workers' levels of emotional labor as they take on more workplace responsibilities.[54] Coping skills Coping occurs in response to psychological stress—usually triggered by changes—in an effort to maintain mental health and emotional well-being. Life stressors are often described as negative events (loss of a job). However, positive changes in life (a new job) can also constitute life stressors, thus requiring the use of coping skills to adapt. Coping strategies are the behaviors, thoughts, and emotions that you use to adjust to the changes that occur in your life.[55] The use of coping skills will help a person better themselves in the work place and perform to the best of their ability to achieve success. There are many ways to cope and adapt to changes. Some ways include: sharing emotions with peers, having a healthy social life outside of work, being humorous, and adjusting expectations of self and work. These coping skills will help turn negative emotion to positive and allow for more focus on the public in contrast to oneself.[56] |

示唆 サービス提供時の笑顔や親しみやすさの表現といったポジティブな感情表現は、顧客の好意的な感情[50]や、再来店意向、他者への店舗推薦意向、総合的な サービス品質の認識といった重要な成果と正の相関がある[51]。感情労働は時間の経過とともに従業員の感情的消耗やバーンアウトを引き起こし、職務満足 度を低下させる可能性があるという証拠がある。つまり、職場での感情調節の度合いが高いほど、従業員の感情的消耗は高まり[10]、職務満足度は低下する [52]。 感情労働の要求度が高いからといって、必ずしも高い賃金で報われるわけではないという実証的証拠がある。むしろ、その報酬は職務に求められる一般的な認知 的負荷のレベルに依存する。つまり、認知的負荷が高い職種では感情労働の要求が増すほど賃金リターンが向上する一方、認知的負荷が低い職種では感情労働の 要求が増すほど賃金が「ペナルティ」を受ける傾向が確認されている[53]。さらに、労働者協同組合への転換、共同管理スキーム、フラットな職場構造な ど、従業員のエンパワーメントを高めるイノベーションは、労働者がより多くの職場責任を担うことで感情労働のレベルを増加させることが判明している。 [54] 対処スキル 対処とは、心理的ストレス(通常は変化によって引き起こされる)への反応として、精神的健康と感情的な幸福を維持しようとする努力である。生活ストレス要 因は、往々にしてネガティブな出来事(失業など)として説明される。しかし、人生におけるポジティブな変化(新たな就職など)も生活ストレス要因となり得 るため、適応には対処スキルの活用が求められる。対処戦略とは、人生に生じる変化に適応するために用いる行動、思考、感情を指す。[55] 対処スキルの活用は、職場における人格の自己成長を促し、能力を最大限に発揮して成功を収める助けとなる。変化に対処し適応する方法は多岐にわたる。例え ば:同僚と感情を共有する、仕事以外の健全な社交生活を持つ、ユーモアを保つ、自己や仕事への期待を調整する、といった方法がある。これらの対処スキル は、ネガティブな感情をポジティブに変え、自己よりも公的な対象に集中することを可能にする。[56] |

| Hazing Anxiety Bullying Harassment Social stress Affect display Emotion work Affective labor Cognitive labor Compassion fatigue Emotional detachment Emotional self-regulation Kinkeeping Mental health Display rules Peer pressure Toxic positivity Group emotion Dispositional affect Emotions and culture Thought suppression Postponement of affect Afterburn (psychotherapy) Sexism Social influence Superficial charm Verbal self defense Smile mask syndrome Vicarious traumatization Marx's theory of alienation Organizational psychology Keeping up with the joneses Customer relationship management |

ハージング 不安 いじめ 嫌がらせ 社会的ストレス 感情表現 感情労働 感情的労働 認知的労働 思いやりの疲労 感情的距離感 感情の自己調整 キーンキーピング メンタル健康 表現ルール 仲間からの圧力 有害なポジティブ思考 集団感情 気質的感情 感情と文化 思考抑制 感情の後延 アフターバーン (心理療法) 性差別 社会的影響 表面的な魅力 言語的自己防衛 スマイルマスク症候群 代理トラウマ マルクスの疎外理論 組織心理学 隣人との競争 顧客関係管理 |

| References | |

| Further reading Abraham, R (May 1998). "Emotional dissonance in organizations: Antecedents, consequences, and moderators". Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 124 (2): 229–246. PMID 9597747. Adelman, P.K. (1995), "Emotional labor as a potential source of job stress", in Sauter, S.L.; Murphy, L.R. (eds.), Organizational risk factors for job stress, Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 371–381, ISBN 978-1-55798-297-1 Ashforth, B. E.; Humphrey, R. H. (1993). "Emotional labor in service roles: The influence of identity". Academy of Management Review. 18 (1): 88–115. doi:10.5465/amr.1993.3997508. JSTOR 258824. Brotheridge, C. M.; Grandey, A. A. (2002). "Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of 'people work'". Journal of Vocational Behavior. 60: 17–39. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2001.1815. S2CID 37027572. Brotheridge, C. M.; Lee, R. T. (2002). "Testing a conservation of resources model of the dynamics of emotional labor". Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 7 (1): 57–67. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.7.1.57. PMID 11827234. Cropanzano, R.; Rupp, D.E.; Byrne, Z.S. (2003). "The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance and organizational citizenship behaviors" (PDF). Journal of Applied Psychology. 88 (1): 160–169. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.160. PMID 12675403. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-15. Diefendorff, J. M.; Richard, E. M. (2003). "Antecedents and consequences of emotional display rule perceptions". Journal of Applied Psychology. 88 (2): 284–294. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.284. PMID 12731712. Erickson, R. J.; Wharton, A. S. (1997). "Inauthenticity and depression: Assessing the consequences of interactive service work". Work and Occupations. 24 (2): 188–213. doi:10.1177/0730888497024002004. S2CID 145001059. Friedman, H. S.; Prince, L. M.; Riggio, R. E.; DiMatteo, R. (1980). "Understanding and assessing nonverbal expressiveness: The affective communication test". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 39 (2): 333–351. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.2.333. S2CID 444767. Glomb, T.M.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.; Rotundo, M. (2004). "Emotional Labor Demands and Compensating Wage Differentials" (PDF). Journal of Applied Psychology. 89 (4): 700–714. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.700. PMID 15327355. Pdf. Grandey, A.A. (2000). "Emotion regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor". Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 5 (1): 59–100. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95. PMID 10658889. S2CID 18404826. Pdf. Archived 2006-09-20 at the Wayback Machine Grandey, A.; Dickter, D.; Sin, H.P. (2004). "The customer is not always right: Customer verbal aggression toward service employees". Journal of Organizational Behavior. 25 (3): 397–418. doi:10.1002/job.252. S2CID 144661055. Pdf. Archived 2023-04-15 at the Wayback Machine Grandey, A.A.; Fisk, G.M.; Steiner, D.D. (2005). "Must "service with a smile" be stressful? The moderate role of personal control for American and French employees". Journal of Applied Psychology. 90 (5): 893–904. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.893. PMID 16162062. S2CID 41790033. Archived from the original on 2015-07-27. Retrieved 2007-08-29. Grove, S.J.; Fisk, R.P. (1989), "Impression management in services marketing: a dramaturgical perspective", in Giacalone, R.A.; Rosenfeld, P. (eds.), Impression Management in the Organization, Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 427–438, ISBN 978-0-8058-0696-0 Gross, J (1998a). "Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 74 (1): 224–237. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.688.783. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.224. PMID 9457784. S2CID 3031566. Gross, J (1998b). "The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review" (PDF). Review of General Psychology. 2 (3): 271–299. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.476.7042. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271. S2CID 6236938. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 22, 2005. Hochschild, A.R. (1983). The managed heart: commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05454-7. Ito, J.; Brotheridge, C. (2003). "Resources, coping strategies, and emotional exhaustion: A conservation of resources perspective". Journal of Vocational Behavior. 63 (3): 490–509. doi:10.1016/s0001-8791(02)00033-7. Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. (Spring 1988). "SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring customer perceptions of service quality". Journal of Retailing. 64 (1): 12–40. Pdf. Pugliesi, K (1999). "The consequences of emotional labor in a complex organization". Motivation and Emotion. 23 (2): 125–154. doi:10.1023/A:1021329112679. S2CID 141064709. Rafaeli, A.; Sutton, R. I. (1989). "The expression of emotion in organizational life". Research in Organizational Behavior. 11: 1–42. Pdf. Ragin, Charles C. (1994). Constructing social research: the unity and diversity of method. Thousand Oaks, California: Pine Forge Press. ISBN 978-0-8039-9021-0. Sutton, R. I.; Rafaeli, I. (1988). "Untangling the relationship between displayed emotions and organizational sales: The case of convenience stores". Academy of Management Journal. 31 (3): 461–487. JSTOR 256456. Tracy, S (2000). "Becoming a character for commerce emotion". Management Communication Quarterly. 14 (1): 90–128. doi:10.1177/0893318900141004. S2CID 144163747. Wichroski, M.R. (1994). "The secretary: invisible labor in the workworld of women". Human Organization. 53 (1): 33–41. doi:10.17730/humo.53.1.a1205g53j7334631. Wilding, M.; Chae, K.; Jang, J. (2014). "Emotional labor in Korean local government: testing the consequences of situational factors and emotional dissonance". Public Performance & Management Review. 38 (2): 316–336. doi:10.1080/15309576.2015.983838. S2CID 144172415. Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R. (1998). "Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover". Journal of Applied Psychology. 83 (3): 486–493. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.486. PMID 9648526. Zapf, D (2002). "Emotion work and psychological well-being. A review of the literature and some conceptual considerations". Human Resource Management Review. 12 (2): 237–268. doi:10.1016/s1053-4822(02)00048-7. |

追加文献(さらに読む) Abraham, R (1998年5月). 「組織における感情的不協和:先行要因、結果、および緩和要因」. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 124 (2): 229–246. PMID 9597747. Adelman, P.K. (1995), 「仕事のストレスの潜在的な原因としての感情労働」, Sauter, S.L.; Murphy, L.R. (eds.), 仕事のストレスに関する組織的リスク要因, ワシントン DC: アメリカ心理学会, pp. 371–381, ISBN 978-1-55798-297-1 Ashforth, B. E.; Humphrey, R. H. (1993). 「サービス職における感情労働:アイデンティティの影響」. Academy of Management Review. 18 (1): 88–115. doi:10.5465/amr.1993.3997508. JSTOR 258824. Brotheridge, C. M.; Grandey, A. A. (2002). 「感情労働とバーンアウト:『人と関わる仕事』の二つの視点の比較」. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 60: 17–39. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2001.1815. S2CID 37027572. Brotheridge, C. M.; Lee, R. T. (2002). 「感情労働の力学に関する資源保存モデルの検証」. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 7 (1): 57–67. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.7.1.57. PMID 11827234. クロパンザーノ、R.;ラップ、D.E.;バーン、Z.S. (2003). 「感情的消耗と仕事への態度、職務遂行能力、組織市民行動の関係」 (PDF). 応用心理学ジャーナル. 88 (1): 160–169. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.160. PMID 12675403. 2010年2月15日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブされた。 Diefendorff, J. M.; Richard, E. M. (2003). 「感情表現ルールの認識の前提条件と結果」. Journal of Applied Psychology. 88 (2): 284–294. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.284. PMID 12731712. エリクソン、R. J.;ワートン、A. S. (1997). 「不誠実さと抑うつ:対話型サービス業務の結果評価」. 仕事と職業. 24 (2): 188–213. doi:10.1177/0730888497024002004. S2CID 145001059. フリードマン, H. S.; プリンス, L. M.; リッジョ, R. E.; ディマッテオ, R. (1980). 「非言語的表現性の理解と評価:感情的コミュニケーションテスト」. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 39 (2): 333–351. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.2.333. S2CID 444767. Glomb, T.M.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.; Rotundo, M. (2004). 「感情労働の要求と補償的賃金格差」 (PDF). Journal of Applied Psychology. 89 (4): 700–714. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.700. PMID 15327355. Pdf. Grandey, A.A. (2000). 「職場における感情調節:感情労働を概念化する新たな方法」 . 職業健康心理学ジャーナル. 5 (1): 59–100. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95. PMID 10658889. S2CID 18404826. Pdf. 2006年9月20日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ Grandey, A.; Dickter, D.; Sin, H.P. (2004). 「顧客は常に正しいとは限らない:サービス従業員に対する顧客の言語的攻撃性」. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 25 (3): 397–418. doi:10.1002/job.252. S2CID 144661055. Pdf. 2023-04-15 ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ Grandey, A.A.; Fisk, G.M.; Steiner, D.D. (2005). 「笑顔のサービス」はストレスになるものなのか?アメリカとフランスの従業員における個人的な自己制御の適度な役割」. Journal of Applied Psychology. 90 (5): 893–904. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.893. PMID 16162062. S2CID 41790033. 2015年7月27日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2007年8月29日に取得。 Grove, S.J.; フィスク, R.P. (1989), 「サービス・マーケティングにおける印象管理:ドラマトゥルギー的視点」, ジャカローン, R.A.; ローゼンフェルド, P. (編), 『組織における印象管理』, ニュージャージー州ヒルズデール: ローレンス・エルバウム, pp. 427–438, ISBN 978-0-8058-0696-0 Gross, J (1998a). 「先行要因と反応に焦点を当てた感情調節:経験、表現、生理への異なる結果」. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 74 (1): 224–237. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.688.783. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.224. PMID 9457784. S2CID 3031566. Gross, J (1998b). 「感情調節という新興分野:統合的レビュー」 (PDF). Review of General Psychology. 2 (3): 271–299. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.476.7042. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271. S2CID 6236938. 2005年5月22日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブされた。 ホックシールド, A.R. (1983). 『管理された心:人間の感情の商業化』. バークレー: カリフォルニア大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-520-05454-7. 伊藤, J.; ブラザリッジ, C. (2003). 「資源、対処戦略、および感情的消耗:資源保全の視点」. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 63 (3): 490–509. doi:10.1016/s0001-8791(02)00033-7. Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. (1988年春). 「SERVQUAL:サービス品質に対する顧客の認識を測定する多項目尺度」. Journal of Retailing. 64 (1): 12–40. Pdf. Pugliesi, K (1999). 「複雑な組織における感情労働の結果」. 動機付けと感情. 23 (2): 125–154. doi:10.1023/A:1021329112679. S2CID 141064709. ラファエリ、A.;サットン、R. I.(1989)。「組織生活における感情表現」。『組織行動研究』。11: 1–42。PDF。 レイジン、チャールズ・C.(1994)。『社会調査の構築:方法の統一性と多様性』。カリフォルニア州サウザンドオークス:パインフォージプレス。ISBN 978-0-8039-9021-0. サットン, R. I.; ラファエリ, I. (1988). 「表出された感情と組織売上高の関係の解明:コンビニエンスストアの事例」. 『経営学会ジャーナル』. 31 (3): 461–487. JSTOR 256456. トレーシー、S(2000)。「商業感情のためのキャラクターになること」。『マネジメント・コミュニケーション・クォータリー』。14(1): 90–128。doi:10.1177/0893318900141004。S2CID 144163747。 ウィクロスキー、M.R. (1994). 「秘書:女性の職場における見えない労働」. 『ヒューマン・オーガニゼーション』. 53 (1): 33–41. doi:10.17730/humo.53.1.a1205g53j7334631. ワイルディング, M.; チェ, K.; チャン, J. (2014). 「韓国地方政府における感情労働:状況的要因と感情的不協和の結果の検証」. 『公共パフォーマンス&マネジメントレビュー』. 38 (2): 316–336. doi:10.1080/15309576.2015.983838. S2CID 144172415. ライト、T.A.;クロパンザーノ、R. (1998). 「職務遂行能力と自発的離職の予測因子としての感情的消耗」. 応用心理学ジャーナル. 83 (3): 486–493. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.486. PMID 9648526. ザップフ、D (2002). 「感情労働と心理的幸福感。文献レビューと概念的考察」. 『人的資源管理レビュー』. 12 (2): 237–268. doi:10.1016/s1053-4822(02)00048-7. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emotional_labor |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099