Emotion

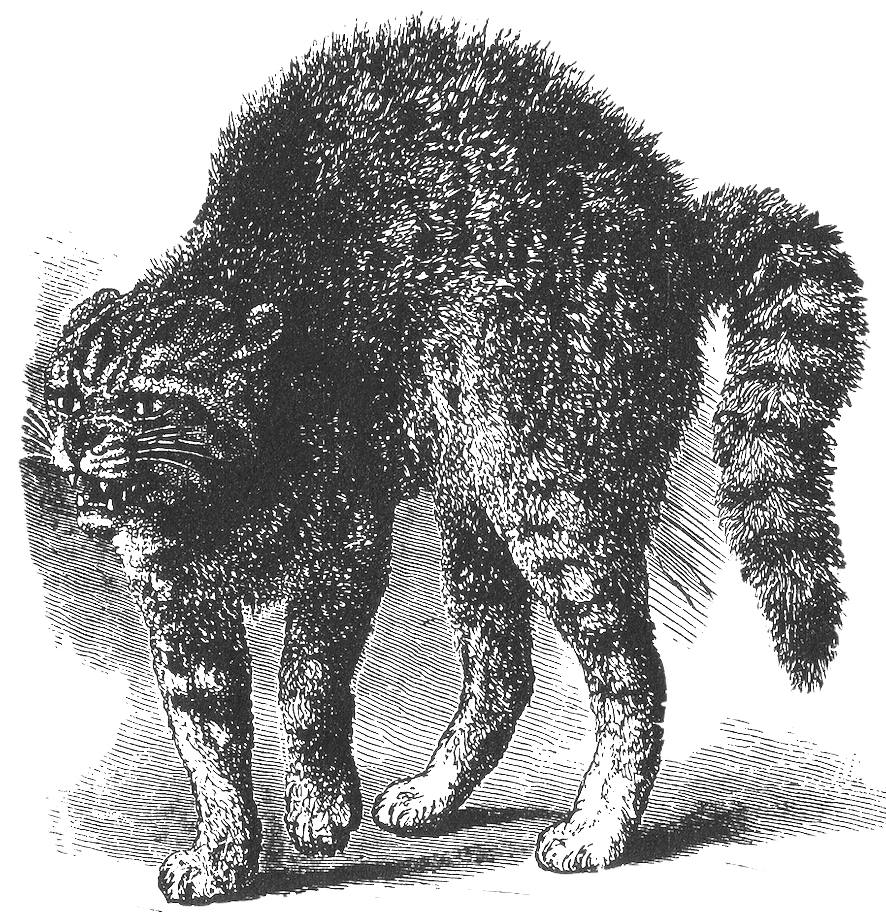

Illustration from Charles Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in

Man and Animals (1872)

Emotion

Illustration from Charles Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in

Man and Animals (1872)

■感情(ないしは情動:emotion)は神経生理学的変化によっても たらされる精神 状態であり、思考、感 情、行動反応、快不快の度合いなど様々な関連性がある。現在では、定義に関する科学的コンセンサスはない。感情はしばしば気分、気質、性格、性質、創造性 と絡められているようである。西洋近代の概念では、情動=感情の反対語は「理性/合理性」と見なされることが多い(→「情動と理性」)。

★感情の語彙

★情動あるいは感情(emotion)と区別がつき難いのが 情熱/熱情/情念と訳されることの多いパッション(Passions)

である。エモーションの説明の後に、このパッション(その哲学的側面)について説明する。

★感情(サンチマン)が対象によって決められるもののように思い、また情動をすべて、なんら かの知的対象が感受性のうちに起こしてきた反響だと考えるのは主知主義の過剰による(ベルクソン 1969:253/Bergson 1941:37)

★Paradoxia epidemica, emotion as cultural construction

| Emotions are mental

states

brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with

thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or

displeasure.[1][2][3][4][5] There is currently no scientific consensus

on a definition.[6] Emotions are often intertwined with mood,

temperament, personality, disposition, or creativity.[7] Research on emotion has increased over the past two decades with many fields contributing including psychology, medicine, history, sociology of emotions, and computer science. The numerous theories that attempt to explain the origin, function and other aspects of emotions have fostered more intense research on this topic. Current areas of research in the concept of emotion include the development of materials that stimulate and elicit emotion. In addition, PET scans and fMRI scans help study the affective picture processes in the brain.[8] From a mechanistic perspective, emotions can be defined as "a positive or negative experience that is associated with a particular pattern of physiological activity." Emotions produce different physiological, behavioral and cognitive changes. The original role of emotions was to motivate adaptive behaviors that in the past would have contributed to the passing on of genes through survival, reproduction, and kin selection.[9][10] In some theories, cognition is an important aspect of emotion. Other theories, however, claim that emotion is separate from and can precede cognition. Consciously experiencing an emotion is exhibiting a mental representation of that emotion from a past or hypothetical experience, which is linked back to a content state of pleasure or displeasure.[11] The content states are established by verbal explanations of experiences, describing an internal state.[12] Emotions are complex. There are various theories on the question of whether or not emotions cause changes in our behaviour.[5] On the one hand, the physiology of emotion is closely linked to arousal of the nervous system. Emotion is also linked to behavioral tendency. Extroverted people are more likely to be social and express their emotions, while introverted people are more likely to be more socially withdrawn and conceal their emotions. Emotion is often the driving force behind motivation.[13] On the other hand, emotions are not causal forces but simply syndromes of components, which might include motivation, feeling, behaviour, and physiological changes, but none of these components is the emotion. Nor is the emotion an entity that causes these components.[14]  Emotions involve different components, such as subjective

experience,

cognitive processes, expressive behavior, psychophysiological changes,

and instrumental behavior. At one time, academics attempted to identify

the emotion with one of the components: William James with a subjective

experience, behaviorists with instrumental behavior,

psychophysiologists with physiological changes, and so on. More

recently, emotion is said to consist of all the components. The

different components of emotion are categorized somewhat differently

depending on the academic discipline. In psychology and philosophy,

emotion typically includes a subjective, conscious experience

characterized primarily by psychophysiological expressions, biological

reactions, and mental states. A similar multi-componential description

of emotion is found in sociology. For example, Peggy Thoits[15]

described emotions as involving physiological components, cultural or

emotional labels (anger, surprise, etc.), expressive body actions, and

the appraisal of situations and contexts. Emotions involve different components, such as subjective

experience,

cognitive processes, expressive behavior, psychophysiological changes,

and instrumental behavior. At one time, academics attempted to identify

the emotion with one of the components: William James with a subjective

experience, behaviorists with instrumental behavior,

psychophysiologists with physiological changes, and so on. More

recently, emotion is said to consist of all the components. The

different components of emotion are categorized somewhat differently

depending on the academic discipline. In psychology and philosophy,

emotion typically includes a subjective, conscious experience

characterized primarily by psychophysiological expressions, biological

reactions, and mental states. A similar multi-componential description

of emotion is found in sociology. For example, Peggy Thoits[15]

described emotions as involving physiological components, cultural or

emotional labels (anger, surprise, etc.), expressive body actions, and

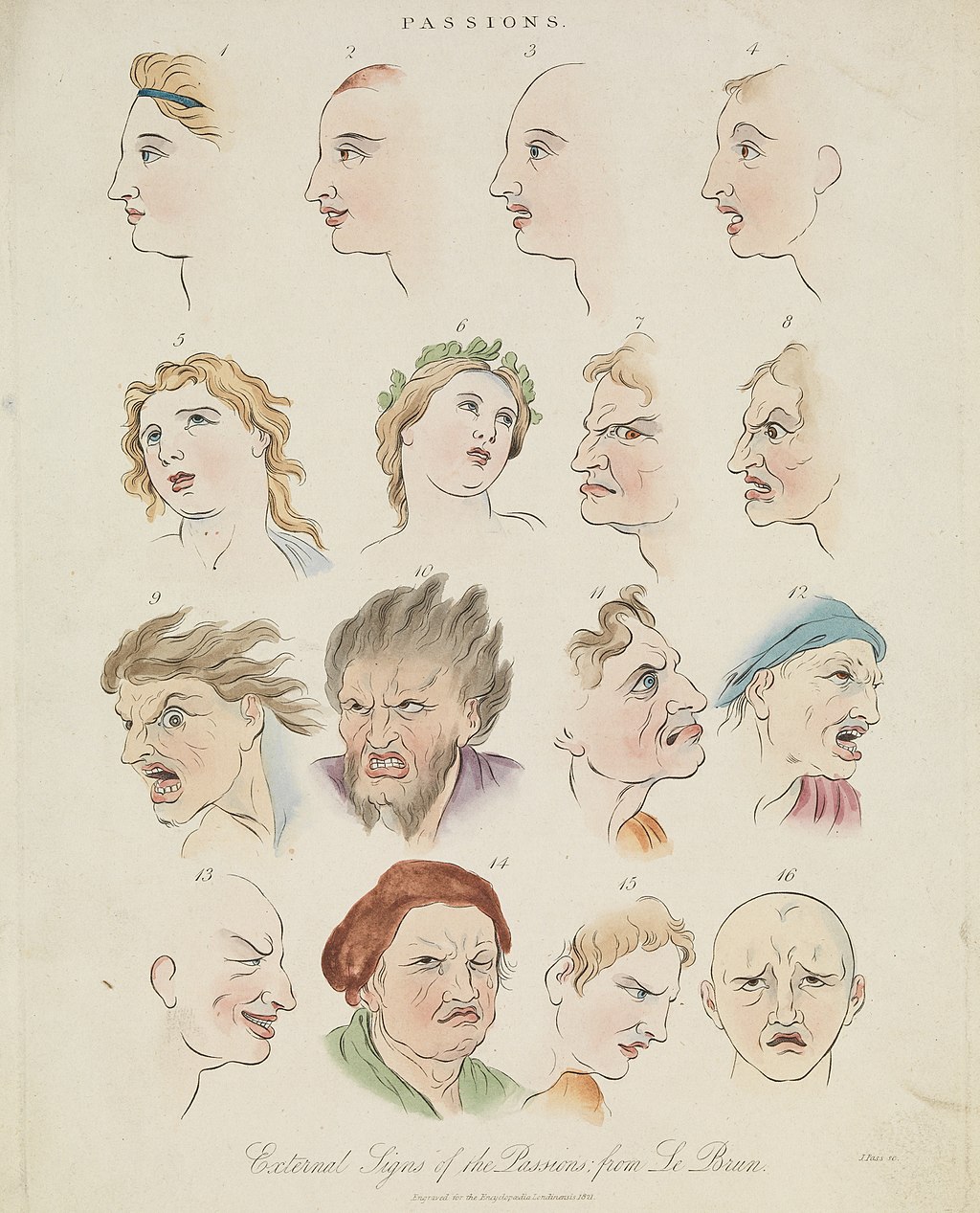

the appraisal of situations and contexts.Sixteen faces expressing the human passions – colored engraving by J. Pass, 1821, after Charles Le Brun |

感情は神経生理学的変化によってもたらされる精神状態であり、思考、感

情、行動反応、快不快の度合いなど様々な関連性がある[1][2][3][4][5]。現在定義に関する科学的コンセンサスはない[6]

感情はしばしば気分、気質、性格、性質、創造性と絡められている[7]。 感情に関する研究は、心理学、医学、歴史、感情の社会学、コンピュータ科学など多くの分野が貢献し、過去20年間で増加している。感情の起源、機能、その 他の側面を説明しようとする数多くの理論が、このテーマのより熱心な研究を育んできた。現在の感情概念の研究分野には、感情を刺激し誘発する材料の開発な どがある。また、PETスキャンやfMRIスキャンは、脳内の感情画像プロセスの研究に役立っている[8]。 力学的な観点から、情動は "生理的活動の特定のパターンと関連するポジティブまたはネガティブな経験 "と定義することができる。感情は、さまざまな生理的、行動的、認知的な変化をもたらす。感情の本来の役割は、過去には生存、生殖、血縁選択を通じて遺伝 子の継承に貢献したであろう適応的行動を動機付けることであった[9][10]。 ある理論では、認知は情動の重要な側面であるとする。しかし、他の理論では、感情は認知とは別個のものであり、認知に先行することができると主張してい る。感情を意識的に経験することは過去または仮説的な経験からその感情の精神的表現を示すことであり、それは喜びまたは不快の内容状態にリンクされている [11]。内容状態は経験の言語的説明によって成立し、内部状態を記述している[12]。 感情は複雑である。感情が行動の変化を引き起こすかどうかという問題には様々な説がある[5] 一方では、感情の生理は神経系の覚醒と密接に関連している。また、情動は行動傾向とも関連している。外向的な人は社交的で感情を表に出す傾向があり、内向 的な人は社交的でなく感情を隠す傾向がある。感情はしばしば動機づけの原動力となる[13]。一方、感情は因果的な力ではなく、単に構成要素の症候群であ り、動機づけ、感情、行動、生理的変化などが考えられるが、これらの構成要素はいずれも感情ではない。また感情はこれらの構成要素を引き起こす実体でもな い[14]。  感情は主観的経験、認知過程、表現行動、心理生理学的変化、道具的行動などの異なる構成要素を含んでいる。一時期、学者たち

は感情を構成要素のうちの1つ

に特定しようとした。ウィリアム・ジェームズは主観的経験、行動学者は道具的行動、心理物理学者は生理的変化、といった具合に。最近では、感情はすべての

要素から構成されていると言われている。感情の構成要素は、学問分野によって多少異なる分類がなされている。心理学や哲学では、情動は主に心理生理学的表

現、生物学的反応、精神状態によって特徴づけられる主観的、意識的な経験を含むのが一般的である。社会学でも、同様の多成分からなる情動の記述が見られ

る。例えば、Peggy

Thoits[15]は、感情を、生理的要素、文化的または感情的なラベル(怒り、驚きなど)、表現的な身体動作、および状況や文脈の評価を含むものとし

て記述している。 感情は主観的経験、認知過程、表現行動、心理生理学的変化、道具的行動などの異なる構成要素を含んでいる。一時期、学者たち

は感情を構成要素のうちの1つ

に特定しようとした。ウィリアム・ジェームズは主観的経験、行動学者は道具的行動、心理物理学者は生理的変化、といった具合に。最近では、感情はすべての

要素から構成されていると言われている。感情の構成要素は、学問分野によって多少異なる分類がなされている。心理学や哲学では、情動は主に心理生理学的表

現、生物学的反応、精神状態によって特徴づけられる主観的、意識的な経験を含むのが一般的である。社会学でも、同様の多成分からなる情動の記述が見られ

る。例えば、Peggy

Thoits[15]は、感情を、生理的要素、文化的または感情的なラベル(怒り、驚きなど)、表現的な身体動作、および状況や文脈の評価を含むものとし

て記述している。人間の情熱を表現する16の顔 - シャルル・ル・ブランに倣ったJ.パスによる彩色版画、1821年 |

| Etymology The word "emotion" dates back to 1579, when it was adapted from the French word émouvoir, which means "to stir up". The term emotion was introduced into academic discussion as a catch-all term to passions, sentiments and affections.[16] The word "emotion" was coined in the early 1800s by Thomas Brown and it is around the 1830s that the modern concept of emotion first emerged for the English language.[17] "No one felt emotions before about 1830. Instead they felt other things – 'passions', 'accidents of the soul', 'moral sentiments' – and explained them very differently from how we understand emotions today."[17] Some cross-cultural studies indicate that the categorization of "emotion" and classification of basic emotions such as "anger" and "sadness" are not universal and that the boundaries and domains of these concepts are categorized differently by all cultures.[18] However, others argue that there are some universal bases of emotions (see Section 6.1).[19] In psychiatry and psychology, an inability to express or perceive emotion is sometimes referred to as alexithymia.[20] |

語源 感情」という言葉は、「かき立てる」という意味のフランス語の単語émouvoirから適応された1579年にさかのぼる。感情という言葉は、情熱、 感情、情緒へのキャッチオール用語として学術的な議論に導入された[16]。「感情」という言葉はトーマス・ブラウンによって1800年代初頭に作られ、 それは英語のために最初に感情の近代的な概念が現れた1830年代頃である[17]「誰も1830年くらい前に感情を感じていない。その代わりに彼らは他 のもの-「情熱」、「魂の事故」、「道徳的感情」-を感じ、それらを今日の感情の理解方法とは全く異なる方法で説明した」[17]。 いくつかの異文化研究は、「感情」の分類や「怒り」や「悲しみ」といった基本的な感情の分類は普遍的ではなく、これらの概念の境界や領域はすべての文化に よって異なって分類されることを示している[18]。 しかし、感情にはいくつかの普遍的基盤(セクション 6.1 参照)があると主張する者もいる[19] 精神医学や心理学において、感情を表現または認識できないことは時にアレキシサイミアと呼ばれている [20]。 |

| History Human nature and the accompanying bodily sensations have always been part of the interests of thinkers and philosophers. Far more extensively, this has also been of great interest to both Western and Eastern societies. Emotional states have been associated with the divine and with the enlightenment of the human mind and body.[21] The ever-changing actions of individuals and their mood variations have been of great importance to most of the Western philosophers (including Aristotle, Plato, Descartes, Aquinas, and Hobbes), leading them to propose extensive theories—often competing theories—that sought to explain emotion and the accompanying motivators of human action, as well as its consequences. In the Age of Enlightenment, Scottish thinker David Hume[22] proposed a revolutionary argument that sought to explain the main motivators of human action and conduct. He proposed that actions are motivated by "fears, desires, and passions". As he wrote in his book Treatise of Human Nature (1773): "Reason alone can never be a motive to any action of the will… it can never oppose passion in the direction of the will… The reason is, and ought to be, the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them".[23] With these lines, Hume attempted to explain that reason and further action would be subject to the desires and experience of the self. Later thinkers would propose that actions and emotions are deeply interrelated with social, political, historical, and cultural aspects of reality that would also come to be associated with sophisticated neurological and physiological research on the brain and other parts of the physical body. |

歴史 人間の本質とそれに伴う身体感覚は、常に思想家や哲学者の興味の対象であった。さらに広範に、これは西洋と東洋の両方の社会にとって大きな関心事であっ た。感情の状態は神や人間の心と体の啓蒙と関連付けられてきた[21]。個人の常に変化する行動とその気分の変化は、アリストテレス、プラトン、デカル ト、アクィナス、ホッブズを含む西洋哲学者のほとんどにとって重要であり、彼らは感情や人間の行動の伴う動機づけ、その結果を説明しようとする広範な理論 (しばしば競合する理論)を提案するに至った。 啓蒙の時代には、スコットランドの思想家ヒューム[22]が、人間の行動や行為の主な動機づけを説明しようとする画期的な議論を展開した。彼は、行動は 「恐怖、欲望、情熱」によって動機づけられると提唱した。彼は『人間本性論』(1773年)の中でこう書いている。「理性は情熱の奴隷であり、そうである べきで、情熱に仕え、従うこと以外には決して務めを果たせない」[23] これらの行によって、ヒュームは理性とさらなる行動が自己の欲望と経験に従うことを説明しようとしたのである。後の思想家たちは、行動と感情は現実の社会 的、政治的、歴史的、文化的側面と深く関係しており、それはまた脳や肉体の他の部分に関する高度な神経学的、生理学的研究と関連付けられるようになると提 唱することになる。 |

| Definitions The Lexico definition of emotion is "A strong feeling deriving from one's circumstances, mood, or relationships with others."[24] Emotions are responses to significant internal and external events.[25] Emotions can be occurrences (e.g., panic) or dispositions (e.g., hostility), and short-lived (e.g., anger) or long-lived (e.g., grief).[26] Psychotherapist Michael C. Graham describes all emotions as existing on a continuum of intensity.[27] Thus fear might range from mild concern to terror or shame might range from simple embarrassment to toxic shame.[28] Emotions have been described as consisting of a coordinated set of responses, which may include verbal, physiological, behavioral, and neural mechanisms.[29] Emotions have been categorized, with some relationships existing between emotions and some direct opposites existing. Graham differentiates emotions as functional or dysfunctional and argues all functional emotions have benefits.[30] In some uses of the word, emotions are intense feelings that are directed at someone or something.[31] On the other hand, emotion can be used to refer to states that are mild (as in annoyed or content) and to states that are not directed at anything (as in anxiety and depression). One line of research looks at the meaning of the word emotion in everyday language and finds that this usage is rather different from that in academic discourse.[32] In practical terms, Joseph LeDoux has defined emotions as the result of a cognitive and conscious process which occurs in response to a body system response to a trigger.[33] |

定義 感情のLexicoの定義は「状況、気分、または他者との関係から派生する強い感情」[24]であり、感情は重要な内外の出来事に対する反応である [25]。 感情は発生(例:パニック)または処分(例:敵意)であり、短命(例:怒り)または長命(例:悲しみ)であることができる[26]。26] 心理療法士のマイケル・C・グラハムはすべての感情が強度の連続体に存在すると説明している[27]。したがって、恐怖は軽度の懸念から恐怖まで、恥は単 純な恥ずかしさから毒性のある恥まで及ぶかもしれない[28] 感情は言語、生理、行動および神経メカニズムを含むかもしれない反応の協調セットからなると記述されてきた[29]。 感情は、感情間に存在するいくつかの関係と存在するいくつかの正反対とに分類されている。グラハムは感情を機能的または機能不全として区別し、すべての機 能的な感情が利益を有すると主張している[30]。 一方、感情は穏やかな状態(イライラや満足のように)や何にも向けられていない状態(不安や落ち込みのように)を指すために使われることもある。ある研究 では、日常言語における感情という言葉の意味を調べ、この用法が学術的な言説におけるそれとはかなり異なることを見出している[32]。 実用的な用語としては、Joseph LeDouxは感情をトリガーに対する身体システムの反応に反応して起こる認知的・意識的なプロセスの結果として定義している[33]。 |

| Components According to Scherer's Component Process Model (CPM) of emotion,[34] there are five crucial elements of emotion. From the component process perspective, emotional experience requires that all of these processes become coordinated and synchronized for a short period of time, driven by appraisal processes. Although the inclusion of cognitive appraisal as one of the elements is slightly controversial, since some theorists make the assumption that emotion and cognition are separate but interacting systems, the CPM provides a sequence of events that effectively describes the coordination involved during an emotional episode. Cognitive appraisal: provides an evaluation of events and objects. Bodily symptoms: the physiological component of emotional experience. Action tendencies: a motivational component for the preparation and direction of motor responses. Expression: facial and vocal expression almost always accompanies an emotional state to communicate reaction and intention of actions. Feelings: the subjective experience of emotional state once it has occurred. Emotion can be differentiated from a number of similar constructs within the field of affective neuroscience:[29] Feeling: not all feelings include emotion, such as the feeling of knowing. In the context of emotion, feelings are best understood as a subjective representation of emotions, private to the individual experiencing them.[35][better source needed] Moods: diffuse affective states that generally last for much longer durations than emotions; they are also usually less intense than emotions and often appear to lack a contextual stimulus.[31] Affect: used to describe the underlying affective experience of an emotion or a mood. |

構成要素 シェーラーの情動のコンポーネントプロセス・モデル(CPM)[34]によると、情動には5つの重要な要素がある。構成要素プロセスの観点からは、情動体 験は評価プロセスによってこれらすべてのプロセスが短時間に調整され同期されることが必要である。情動と認知は分離しているが相互作用するシステムである とする理論家もいるため、認知的評価を要素の1つとして含めることには若干の異論があるが、CPMは情動エピソードに関わる調整を効果的に記述する一連の 事象を提供するものである。 認知的評価:出来事や対象に対する評価を提供する。 身体症状:感情体験の生理的要素。 行動傾向:運動反応の準備と方向付けのための動機づけの構成要素。 表情: 感情的な状態には、反応や行動の意図を伝えるために、ほとんどの場合、顔や声の表情が伴います。 感情: 感情状態が発生した後の主観的な経験。 情動は、感情神経科学の分野における多くの類似した構成要素から区別することができる[29]。 感情:すべての感情が感情を含むわけではなく、例えば「知 る」という感情などがある。感情の文脈では、感情は感情の主観的な表現として最もよく理解され、それを経験する個人に私的である[35][より良いソース が必要]。 気分: 一般的に感情よりもはるかに長い時間持続する拡散性の感情状態; それらはまた通常、感情よりも激しくなく、しばしば文脈的な刺激を欠いているように見える[31]。 感情:感情や気分の根底にある感情的な経験を表現するために使われる。 |

| Purpose and value One view is that emotions facilitate adaptive responses to environmental challenges. Emotions have been described as a result of evolution because they provided good solutions to ancient and recurring problems that faced our ancestors.[36] Emotions can function as a way to communicate what's important to individuals, such as values and ethics.[37] However some emotions, such as some forms of anxiety, are sometimes regarded as part of a mental illness and thus possibly of negative value.[38] |

目的と価値 1つの見解は、感情は環境上の課題に対する適応的な反応を促進するというものである。感情は我々の祖先が直面した古くから繰り返される問題に対して良い解 決策を提供したため、進化の結果として説明されている[36]。感情は価値や倫理など、個人にとって重要なことを伝える方法として機能しうる[37]。 しかし、ある種の不安など一部の感情は時に精神疾患の一部とみなされ、したがって負の価値を持つ可能性がある[38]。 |

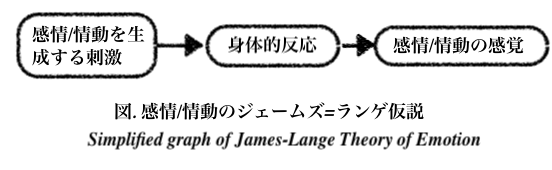

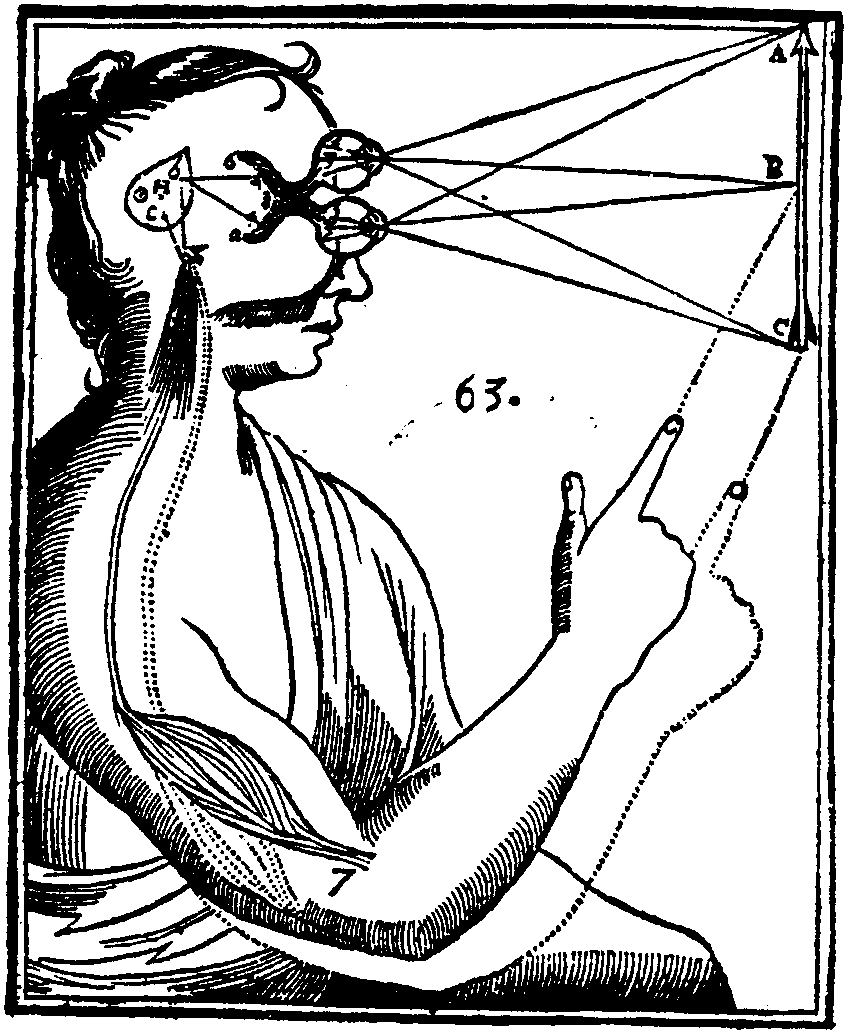

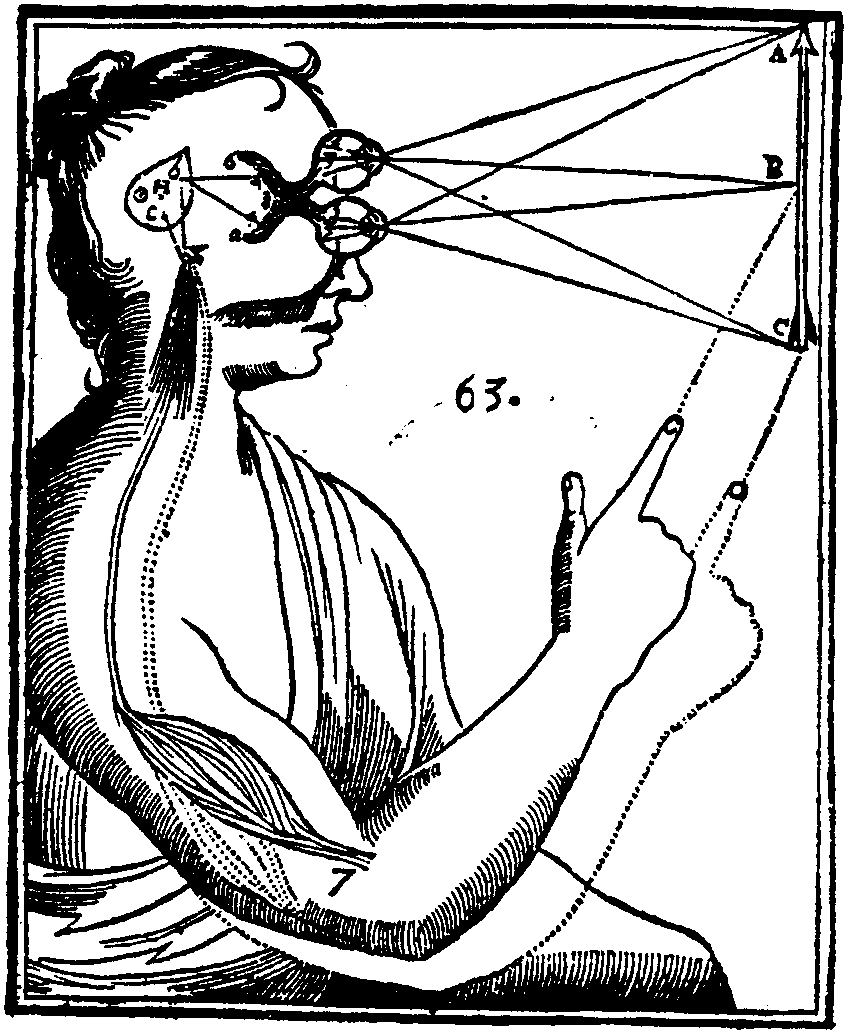

| Classification A distinction can be made between emotional episodes and emotional dispositions. Emotional dispositions are also comparable to character traits, where someone may be said to be generally disposed to experience certain emotions. For example, an irritable person is generally disposed to feel irritation more easily or quickly than others do. Finally, some theorists place emotions within a more general category of "affective states" where affective states can also include emotion-related phenomena such as pleasure and pain, motivational states (for example, hunger or curiosity), moods, dispositions and traits.[39] Basic emotions For more than 40 years, Paul Ekman has supported the view that emotions are discrete, measurable, and physiologically distinct. Ekman's most influential work revolved around the finding that certain emotions appeared to be universally recognized, even in cultures that were preliterate and could not have learned associations for facial expressions through media. Another classic study found that when participants contorted their facial muscles into distinct facial expressions (for example, disgust), they reported subjective and physiological experiences that matched the distinct facial expressions. Ekman's facial-expression research examined six basic emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise.[40] Later in his career,[41] Ekman theorized that other universal emotions may exist beyond these six. In light of this, recent cross-cultural studies led by Daniel Cordaro and Dacher Keltner, both former students of Ekman, extended the list of universal emotions. In addition to the original six, these studies provided evidence for amusement, awe, contentment, desire, embarrassment, pain, relief, and sympathy in both facial and vocal expressions. They also found evidence for boredom, confusion, interest, pride, and shame facial expressions, as well as contempt, relief, and triumph vocal expressions.[42][43][44] Robert Plutchik agreed with Ekman's biologically driven perspective but developed the "wheel of emotions", suggesting eight primary emotions grouped on a positive or negative basis: joy versus sadness; anger versus fear; trust versus disgust; and surprise versus anticipation.[45] Some basic emotions can be modified to form complex emotions. The complex emotions could arise from cultural conditioning or association combined with the basic emotions. Alternatively, similar to the way primary colors combine, primary emotions could blend to form the full spectrum of human emotional experience. For example, interpersonal anger and disgust could blend to form contempt. Relationships exist between basic emotions, resulting in positive or negative influences.[46] Jaak Panksepp carved out seven biologically inherited primary affective systems called SEEKING (expectancy), FEAR (anxiety), RAGE (anger), LUST (sexual excitement), CARE (nurturance), PANIC/GRIEF (sadness), and PLAY (social joy). He proposed what is known as "core-SELF" to be generating these affects.[47] Two dimensions of emotion Psychologists have used methods such as factor analysis to attempt to map emotion-related responses onto a more limited number of dimensions. Such methods attempt to boil emotions down to underlying dimensions that capture the similarities and differences between experiences.[49] Often, the first two dimensions uncovered by factor analysis are valence (how negative or positive the experience feels) and arousal (how energized or enervated the experience feels). These two dimensions can be depicted on a 2D coordinate map.[50] This two-dimensional map has been theorized to capture one important component of emotion called core affect.[51][52] Core affect is not theorized to be the only component to emotion, but to give the emotion its hedonic and felt energy. Using statistical methods to analyze emotional states elicited by short videos, Cowen and Keltner identified 27 varieties of emotional experience: admiration, adoration, aesthetic appreciation, amusement, anger, anxiety, awe, awkwardness, boredom, calmness, confusion, craving, disgust, empathic pain, entrancement, excitement, fear, horror, interest, joy, nostalgia, relief, romance, sadness, satisfaction, sexual desire and surprise.[53] Pre-modern history In Buddhism, emotions occur when an object is considered as attractive or repulsive. There is a felt tendency impelling people towards attractive objects and impelling them to move away from repulsive or harmful objects; a disposition to possess the object (greed), to destroy it (hatred), to flee from it (fear), to get obsessed or worried over it (anxiety), and so on.[54] In Stoic theories, normal emotions (like delight and fear) are described as irrational impulses which come from incorrect appraisals of what is 'good' or 'bad'. Alternatively, there are 'good emotions' (like joy and caution) experienced by those that are wise, which come from correct appraisals of what is 'good' and 'bad'.[55][56] Aristotle believed that emotions were an essential component of virtue.[57] In the Aristotelian view all emotions (called passions) corresponded to appetites or capacities. During the Middle Ages, the Aristotelian view was adopted and further developed by scholasticism and Thomas Aquinas[58] in particular. In Chinese antiquity, excessive emotion was believed to cause damage to qi, which in turn, damages the vital organs.[59] The four humours theory made popular by Hippocrates contributed to the study of emotion in the same way that it did for medicine. In the early 11th century, Avicenna theorized about the influence of emotions on health and behaviors, suggesting the need to manage emotions.[60] Early modern views on emotion are developed in the works of philosophers such as René Descartes, Niccolò Machiavelli, Baruch Spinoza,[61] Thomas Hobbes[62] and David Hume. In the 19th century emotions were considered adaptive and were studied more frequently from an empiricist psychiatric perspective. Western theological Christian perspective on emotion presupposes a theistic origin to humanity. God who created humans gave humans the ability to feel emotion and interact emotionally. Biblical content expresses that God is a person who feels and expresses emotion. Though a somatic view would place the locus of emotions in the physical body, Christian theory of emotions would view the body more as a platform for the sensing and expression of emotions. Therefore, emotions themselves arise from the person, or that which is "imago-dei" or Image of God in humans. In Christian thought, emotions have the potential to be controlled through reasoned reflection. That reasoned reflection also mimics God who made mind. The purpose of emotions in human life are therefore summarized in God's call to enjoy Him and creation, humans are to enjoy emotions and benefit from them and use them to energize behavior.[63][64] Evolutionary theories Main articles: Evolution of emotion and Evolutionary psychology Illustration from Charles Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) 19th century Perspectives on emotions from evolutionary theory were initiated during the mid-late 19th century with Charles Darwin's 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.[65] Darwin argued that emotions served no evolved purpose for humans, neither in communication, nor in aiding survival.[66] Darwin largely argued that emotions evolved via the inheritance of acquired characters.[67] He pioneered various methods for studying non-verbal expressions, from which he concluded that some expressions had cross-cultural universality. Darwin also detailed homologous expressions of emotions that occur in animals. This led the way for animal research on emotions and the eventual determination of the neural underpinnings of emotion. Contemporary More contemporary views along the evolutionary psychology spectrum posit that both basic emotions and social emotions evolved to motivate (social) behaviors that were adaptive in the ancestral environment.[13] Emotion is an essential part of any human decision-making and planning, and the famous distinction made between reason and emotion is not as clear as it seems.[68] Paul D. MacLean claims that emotion competes with even more instinctive responses, on one hand, and the more abstract reasoning, on the other hand. The increased potential in neuroimaging has also allowed investigation into evolutionarily ancient parts of the brain. Important neurological advances were derived from these perspectives in the 1990s by Joseph E. LeDoux and Antonio Damasio. Research on social emotion also focuses on the physical displays of emotion including body language of animals and humans (see affect display). For example, spite seems to work against the individual but it can establish an individual's reputation as someone to be feared.[13] Shame and pride can motivate behaviors that help one maintain one's standing in a community, and self-esteem is one's estimate of one's status.[13][69] Somatic theories Somatic theories of emotion claim that bodily responses, rather than cognitive interpretations, are essential to emotions. The first modern version of such theories came from William James in the 1880s. The theory lost favor in the 20th century, but has regained popularity more recently due largely to theorists such as John T. Cacioppo,[70] Antonio Damasio,[71] Joseph E. LeDoux[72] and Robert Zajonc[73] who are able to appeal to neurological evidence.[74] James–Lange theory  Simplified graph of James-Lange Theory of Emotion In his 1884 article[75] William James argued that feelings and emotions were secondary to physiological phenomena. In his theory, James proposed that the perception of what he called an "exciting fact" directly led to a physiological response, known as "emotion."[76] To account for different types of emotional experiences, James proposed that stimuli trigger activity in the autonomic nervous system, which in turn produces an emotional experience in the brain. The Danish psychologist Carl Lange also proposed a similar theory at around the same time, and therefore this theory became known as the James–Lange theory. As James wrote, "the perception of bodily changes, as they occur, is the emotion." James further claims that "we feel sad because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble, and either we cry, strike, or tremble because we are sorry, angry, or fearful, as the case may be."[75] An example of this theory in action would be as follows: An emotion-evoking stimulus (snake) triggers a pattern of physiological response (increased heart rate, faster breathing, etc.), which is interpreted as a particular emotion (fear). This theory is supported by experiments in which by manipulating the bodily state induces a desired emotional state.[77] Some people may believe that emotions give rise to emotion-specific actions, for example, "I'm crying because I'm sad," or "I ran away because I was scared." The issue with the James–Lange theory is that of causation (bodily states causing emotions and being a priori), not that of the bodily influences on emotional experience (which can be argued and is still quite prevalent today in biofeedback studies and embodiment theory).[78] Although mostly abandoned in its original form, Tim Dalgleish argues that most contemporary neuroscientists have embraced the components of the James-Lange theory of emotions.[79] The James–Lange theory has remained influential. Its main contribution is the emphasis it places on the embodiment of emotions, especially the argument that changes in the bodily concomitants of emotions can alter their experienced intensity. Most contemporary neuroscientists would endorse a modified James–Lange view in which bodily feedback modulates the experience of emotion. (p. 583) Cannon–Bard theory Walter Bradford Cannon agreed that physiological responses played a crucial role in emotions, but did not believe that physiological responses alone could explain subjective emotional experiences. He argued that physiological responses were too slow and often imperceptible and this could not account for the relatively rapid and intense subjective awareness of emotion.[80] He also believed that the richness, variety, and temporal course of emotional experiences could not stem from physiological reactions, that reflected fairly undifferentiated fight or flight responses.[81][82] An example of this theory in action is as follows: An emotion-evoking event (snake) triggers simultaneously both a physiological response and a conscious experience of an emotion. Phillip Bard contributed to the theory with his work on animals. Bard found that sensory, motor, and physiological information all had to pass through the diencephalon (particularly the thalamus), before being subjected to any further processing. Therefore, Cannon also argued that it was not anatomically possible for sensory events to trigger a physiological response prior to triggering conscious awareness and emotional stimuli had to trigger both physiological and experiential aspects of emotion simultaneously.[81] Two-factor theory Main article: Two-factor theory of emotion Stanley Schachter formulated his theory on the earlier work of a Spanish physician, Gregorio Marañón, who injected patients with epinephrine and subsequently asked them how they felt. Marañón found that most of these patients felt something but in the absence of an actual emotion-evoking stimulus, the patients were unable to interpret their physiological arousal as an experienced emotion. Schachter did agree that physiological reactions played a big role in emotions. He suggested that physiological reactions contributed to emotional experience by facilitating a focused cognitive appraisal of a given physiologically arousing event and that this appraisal was what defined the subjective emotional experience. Emotions were thus a result of two-stage process: general physiological arousal, and experience of emotion. For example, the physiological arousal, heart pounding, in a response to an evoking stimulus, the sight of a bear in the kitchen. The brain then quickly scans the area, to explain the pounding, and notices the bear. Consequently, the brain interprets the pounding heart as being the result of fearing the bear.[83] With his student, Jerome Singer, Schachter demonstrated that subjects can have different emotional reactions despite being placed into the same physiological state with an injection of epinephrine. Subjects were observed to express either anger or amusement depending on whether another person in the situation (a confederate) displayed that emotion. Hence, the combination of the appraisal of the situation (cognitive) and the participants' reception of adrenaline or a placebo together determined the response. This experiment has been criticized in Jesse Prinz's (2004) Gut Reactions.[84] Cognitive theories With the two-factor theory now incorporating cognition, several theories began to argue that cognitive activity in the form of judgments, evaluations, or thoughts were entirely necessary for an emotion to occur. One of the main proponents of this view was Richard Lazarus who argued that emotions must have some cognitive intentionality. The cognitive activity involved in the interpretation of an emotional context may be conscious or unconscious and may or may not take the form of conceptual processing. Lazarus' theory is very influential; emotion is a disturbance that occurs in the following order: Cognitive appraisal – The individual assesses the event cognitively, which cues the emotion. Physiological changes – The cognitive reaction starts biological changes such as increased heart rate or pituitary adrenal response. Action – The individual feels the emotion and chooses how to react. For example: Jenny sees a snake. Jenny cognitively assesses the snake in her presence. Cognition allows her to understand it as a danger. Her brain activates the adrenal glands which pump adrenaline through her blood stream, resulting in increased heartbeat. Jenny screams and runs away. Lazarus stressed that the quality and intensity of emotions are controlled through cognitive processes. These processes underline coping strategies that form the emotional reaction by altering the relationship between the person and the environment. George Mandler provided an extensive theoretical and empirical discussion of emotion as influenced by cognition, consciousness, and the autonomic nervous system in two books (Mind and Emotion, 1975,[85] and Mind and Body: Psychology of Emotion and Stress, 1984[86]) There are some theories on emotions arguing that cognitive activity in the form of judgments, evaluations, or thoughts are necessary in order for an emotion to occur. A prominent philosophical exponent is Robert C. Solomon (for example, The Passions, Emotions and the Meaning of Life, 1993[87]). Solomon claims that emotions are judgments. He has put forward a more nuanced view which responds to what he has called the 'standard objection' to cognitivism, the idea that a judgment that something is fearsome can occur with or without emotion, so judgment cannot be identified with emotion. The theory proposed by Nico Frijda where appraisal leads to action tendencies is another example. It has also been suggested that emotions (affect heuristics, feelings and gut-feeling reactions) are often used as shortcuts to process information and influence behavior.[88] The affect infusion model (AIM) is a theoretical model developed by Joseph Forgas in the early 1990s that attempts to explain how emotion and mood interact with one's ability to process information. ++++++++++++++++ Perceptual theory Theories dealing with perception either use one or multiples perceptions in order to find an emotion.[89] A recent hybrid of the somatic and cognitive theories of emotion is the perceptual theory. This theory is neo-Jamesian in arguing that bodily responses are central to emotions, yet it emphasizes the meaningfulness of emotions or the idea that emotions are about something, as is recognized by cognitive theories. The novel claim of this theory is that conceptually-based cognition is unnecessary for such meaning. Rather the bodily changes themselves perceive the meaningful content of the emotion because of being causally triggered by certain situations. In this respect, emotions are held to be analogous to faculties such as vision or touch, which provide information about the relation between the subject and the world in various ways. A sophisticated defense of this view is found in philosopher Jesse Prinz's book Gut Reactions,[84] and psychologist James Laird's book Feelings.[77] Affective events theory Affective events theory is a communication-based theory developed by Howard M. Weiss and Russell Cropanzano (1996),[90] that looks at the causes, structures, and consequences of emotional experience (especially in work contexts). This theory suggests that emotions are influenced and caused by events which in turn influence attitudes and behaviors. This theoretical frame also emphasizes time in that human beings experience what they call emotion episodes –\ a "series of emotional states extended over time and organized around an underlying theme." This theory has been used by numerous researchers to better understand emotion from a communicative lens, and was reviewed further by Howard M. Weiss and Daniel J. Beal in their article, "Reflections on Affective Events Theory", published in Research on Emotion in Organizations in 2005.[91] Situated perspective on emotion A situated perspective on emotion, developed by Paul E. Griffiths and Andrea Scarantino, emphasizes the importance of external factors in the development and communication of emotion, drawing upon the situationism approach in psychology.[92] This theory is markedly different from both cognitivist and neo-Jamesian theories of emotion, both of which see emotion as a purely internal process, with the environment only acting as a stimulus to the emotion. In contrast, a situationist perspective on emotion views emotion as the product of an organism investigating its environment, and observing the responses of other organisms. Emotion stimulates the evolution of social relationships, acting as a signal to mediate the behavior of other organisms. In some contexts, the expression of emotion (both voluntary and involuntary) could be seen as strategic moves in the transactions between different organisms. The situated perspective on emotion states that conceptual thought is not an inherent part of emotion, since emotion is an action-oriented form of skillful engagement with the world. Griffiths and Scarantino suggested that this perspective on emotion could be helpful in understanding phobias, as well as the emotions of infants and animals. Genetics Emotions can motivate social interactions and relationships and therefore are directly related with basic physiology, particularly with the stress systems. This is important because emotions are related to the anti-stress complex, with an oxytocin-attachment system, which plays a major role in bonding. Emotional phenotype temperaments affect social connectedness and fitness in complex social systems.[93] These characteristics are shared with other species and taxa and are due to the effects of genes and their continuous transmission. Information that is encoded in the DNA sequences provides the blueprint for assembling proteins that make up our cells. Zygotes require genetic information from their parental germ cells, and at every speciation event, heritable traits that have enabled its ancestor to survive and reproduce successfully are passed down along with new traits that could be potentially beneficial to the offspring. In the five million years since the lineages leading to modern humans and chimpanzees split, only about 1.2% of their genetic material has been modified. This suggests that everything that separates us from chimpanzees must be encoded in that very small amount of DNA, including our behaviors. Students that study animal behaviors have only identified intraspecific examples of gene-dependent behavioral phenotypes. In voles (Microtus spp.) minor genetic differences have been identified in a vasopressin receptor gene that corresponds to major species differences in social organization and the mating system.[94] Another potential example with behavioral differences is the FOCP2 gene, which is involved in neural circuitry handling speech and language.[95] Its present form in humans differed from that of the chimpanzees by only a few mutations and has been present for about 200,000 years, coinciding with the beginning of modern humans.[96] Speech, language, and social organization are all part of the basis for emotions. |

分類 感情のエピソードと感情的な気質は区別されることがある。感情的性質は性格的特徴にも相当し、一般的にある種の感情を経験しやすいと言われることがある。 例えば、イライラしやすい人は、他の人よりもイライラを感じやすい、あるいはすぐに感じてしまうという性質がある。最後に、一部の理論家は感情をより一般 的な「感情状態」のカテゴリーに位置づけ、感情状態には喜びや痛み、動機づけ状態(例えば、空腹感や好奇心)、気分、性質、特徴などの感情に関連する現象 も含めることができる[39]。 基本的な感情 ポール・エクマンは40年以上にわたって、感情は個別的で測定可能であり、生理学的に異なるものであるという見解を支持してきた。エクマンの最も影響力の ある研究は、文字が読めずメディアを通して顔の表情の連想を学ぶことができなかった文化圏においても、特定の感情が普遍的に認識されているように見えると いう発見を中心に展開された。また、被験者が顔の筋肉を歪めて明確な表情(例えば嫌悪感)を作ると、その表情に合った主観的・生理的体験が報告されるとい う古典的な研究結果もある。エクマンの顔表情研究は、怒り、嫌悪、恐怖、幸福、悲しみ、驚きの6つの基本的な感情について調べた[40]。 その後、エクマンはこの6つ以外の普遍的感情が存在する可能性を説いた[41]。このことを踏まえて、エクマンの元生徒であるダニエル・コルダロとダッ チャー・ケルトナーによって導かれた最近の異文化研究は、普遍的感情のリストを拡張した。この研究では、当初の6つの感情に加え、楽しさ、畏怖、満足、欲 求、恥ずかしさ、痛み、安堵、共感が表情と音声で確認された。彼らはまた、退屈、混乱、興味、プライド、恥の表情と同様に軽蔑、安堵、勝利の声の表情の証 拠も見つけた[42][43][44]。 ロバート・プラッチクはエクマンの生物学的に駆動する視点に同意したが、「感情の車輪」を開発し、ポジティブまたはネガティブベースでグループ化された8 つの主要感情(喜び対悲しみ、怒り対恐れ、信頼対嫌悪、驚き対期待)を示唆した[45]。いくつかの基本感情は、複雑な感情を形成するために変更すること が可能である。複雑な感情は文化的な条件付けや基本的な感情と組み合わされた連想から生じる可能性がある。あるいは、原色が組み合わされるのと同様に、一 次感情は人間の感情経験の完全なスペクトルを形成するために混ざり合うことができる。例えば、対人関係における怒りと嫌悪が混ざり合い、軽蔑を形成する可 能性がある。基本的な感情の間には関係が存在し、結果として肯定的または否定的な影響をもたらす[46]。 Jaak Pankseppは、SEEKING(期待)、FEAR(不安)、RAGE(怒り)、LUST(性的興奮)、CARE(養育)、PANIC/GRIEF (悲しみ)、PLAY(社会的喜び)という生物学的に継承された7つの主要感情システムを切り分けた[47]。彼はこれらの影響を生み出しているのは「コ ア-セルフ」と呼ばれるものであると提唱した[47]。 情動の2つの次元 心理学者は、感情関連の反応をより限定された数の次元にマッピングしようとする因子分析のような方法を使われました。このような方法は、感情を経験間の類 似点と相違点を捕らえる基礎的な次元に煮詰めることを試みる[49]。多くの場合、因子分析によって明らかになった最初の2つの次元は、価(経験がどのよ うにネガティブまたはポジティブに感じるか)と覚醒(経験がどのように元気または過敏に感じるか)である。この2次元マップは中核的情 動と呼ばれる感情の重要な構成要素を捕らえることが理論化されてい る[51][52]。中核的情動は感情に対する唯一の構成要素ではない が、感情にその快楽性とフェルトエネルギーを与えることが理論化されて いる。 短いビデオによって引き出された感情状態を分析するために統計的な方法を使用して、CowenとKeltnerは感情経験の27種類を特定した:賞賛、崇 拝、美的鑑賞、娯楽、怒り、不安、畏怖、厄介、退屈、冷静、混乱、渇望、嫌悪、共感の痛み、入場、興奮、恐怖、恐怖、関心、喜び、郷愁、安心、ロマンス、 悲しみ、満足、性的欲求と驚き[53]。 前近代史 仏教では、ある対象が魅力的、または嫌悪的とみなされたときに感情が生じる。人を魅力的な対象に向かわせ、反発や有害な対象から遠ざけようとする感じられ る傾向、対象を所有しようとする傾向(貪欲)、破壊しようとする傾向(憎悪)、対象から逃げようとする傾向(恐怖)、対象に執着したり心配したりする(不 安)、などがある[54]。 ストア派の理論では、通常の感情(喜びや恐れなど)は、何が「良い」か「悪い」かの誤った評価から来る不合理な衝動として説明される。代わりに、賢者に よって経験される「良い感情」(喜びや警戒のような)があり、それは何が「良い」のか「悪い」のかについての正しい評価から来るものである[55] [56]。 アリストテレスは感情が美徳の本質的な構成要素であると信じていた[57]。アリストテレスの見解ではすべての感情(情熱と呼ばれる)は食欲または能力に 対応していた。中世においては、アリストテレスの見解が採用され、特にスコラ学とトマス・アクィナス[58]によってさらに発展させられた。 ヒポクラテスによって広められた四体液説は、医学と同じように感情の研究にも貢献した[59]。 11世紀初頭には、アヴィセンナが健康や行動に対する感情の影響について理論化し、感情を管理する必要性を示唆していた[60]。 感情に関する近世の見解はルネ・デカルト、ニコロ・マキアヴェリ、バルーク・スピノザ[61]、トマス・ホッブス[62]、デイヴィッド・ヒュームといっ た哲学者の作品において展開されている。19世紀には、感情は適応的であると考えられ、経験主義的な精神医学の観点からより頻繁に研究されていた。 西洋神学 キリスト教の感情観は、人間の起源が神道的であることを前提にしている。人間を創造した神は、人間に感情を感じ、感情的に交流する能力を与えた。聖書の内 容は、神が感情を感じ、表現する人であることを表現している。体性論は、感情の所在を肉体に置くが、キリスト教的感情論は、肉体をより感情を感知し表現す るためのプラットフォームとして見ることになる。したがって、感情そのものは、人間、すなわち人間の中にある「イマゴ・デイ」(神の像)から生じるもので ある。キリスト教思想では、感情は理性的な反省によってコントロールされる可能性を持っている。その理性的な反省もまた、心をつくった神に擬態している。 したがって、人間の生活における感情の目的は、神と被造物を楽しめという神の呼びかけに要約され、人間は感情を楽しみ、そこから利益を得て、行動を活性化 するためにそれを利用することである[63][64]。 進化論 主な記事 感情の進化論、進化心理学 チャールズ・ダーウィンの『人間と動物における感情の表現』(1872年)の挿絵 19世紀 ダーウィンは、感情はコミュニケーションにおいても生存を助けることにおいても、人間にとって進化した目的を果たしていないと主張した[66]。また、 ダーウィンは動物で起こる感情の相同表現を詳しく説明した。これは、感情に関する動物研究への道を開き、最終的に感情の神経基盤の決定を導いた。 現代 進化心理学に沿ったより現代的な見解では、基本的な感情と社会的感情の両方が祖先の環境において適応的であった(社会的)行動を動機づけるために進化した と仮定している[13] 感情は人間の意思決定と計画には不可欠な部分であり、理性と感情の間になされた有名な区別は見かけほど明確ではない[68] ポールDマクリーンは、感情は一方ではさらに本能的反応、他方ではさらに抽象的な理性と競争するとしている。神経画像における可能性の増大は、脳の進化的 に古い部分の調査も可能にした。1990年代には、ジョセフ・E・ルドゥーとアントニオ・ダマシオによって、こうした観点から神経学的な重要な進歩が導き 出された。 社会的情動に関する研究は、動物や人間のボディランゲージを含む身体的な情動表出にも焦点を当てている(情動表出を参照)。例えば、腹いせは個人に不利に 働くように見えるが、恐れるべき人物として個人の評判を確立することができる[13]。恥や誇りはコミュニティにおける自分の地位を維持するための行動を 動機づけることができ、自尊心は自分の地位に対する推定である[13][69]。 ソマティック・セオリー 感情の身体的理論は、認知的解釈よりもむしろ身体的な反応が感情に不可欠であると主張している。このような理論の最初の現代版は、1880年代にウィリア ム・ジェームズによってもたらされた。この理論は20世紀に人気を失ったが、ジョン・T・カシオッポ[70]、アントニオ・ダマシオ[71]、ジョセフ・ E・ルドゥー[72]、ロバート・ザジョンク[73]などの理論家が神経学の証拠に訴えることによって主に最近人気を回復してきた[74]。 ジェームズ=ランゲ(James-Lange)理論  ジェイムズ・ランゲ理論の感情(情動)の図式 ウィリアム・ジェームズは1884年の論文[75]で、感情や情動は生理的現象に次ぐものであると主張した。彼の理論では、ジェームズは彼が「刺激的な事 実」と呼んだものの知覚が直接「感情」として知られる生理的反応をもたらすことを提案した[76]。異なるタイプの感情体験を説明するために、ジェームズ は刺激が自律神経系の活動を誘発し、それが脳内で感情体験を生じさせることを提案した。デンマークの心理学者カール・ランゲもほぼ同時期に同様の理論を提 唱していたため、この理論はジェームズ=ランゲ説と呼ばれるようになった。ジェームズは、"身体の変化を、その都度、認識することが感情である "と書いている。ジェームズはさらに、"私たちは泣くから悲しいと感じ、打つから怒ると感じ、震えるから怖いと感じ、泣くのも打つのも震えるのも、場合に よっては、悲しい、怒る、怖いと感じるからだ"[75]と主張している。 この理論が実際に使われる例としては、以下のようなものがある。感情を誘発する刺激(蛇)が生理的反応のパターン(心拍数の増加、呼吸の速さなど)を誘発 し、それが特定の感情(恐怖)として解釈される。この説は、身体の状態を操作することで望ましい情動を誘発する実験によって支持されている[77]。"悲 しいから泣く""怖いから逃げる "など、情動が情動特有の行動を生じさせると考える人もいるかもしれない。ジェームズ=ランゲ説の問題は因果関係(身体的状態が感情を引き起こし、先験的 であること)の問題であり、感情経験に対する身体的影響の問題ではない(これはバイオフィードバック研究や身体論において主張することができ、今日もかな り普及している)[78]。 その原型はほとんど放棄されているが、ティム・ダルグリーシュは、現代の神経科学者のほとんどがジェームズ=ランゲの感情論の構成要素を受け入れていると 主張している[79]。 ジェームズ=ランゲ理論は依然として影響力を持ち続けている。その主な貢献は、感情の体現に重点を置いていることであり、特に感情の身体的付随物の変化が その経験された強度を変えることができるという議論である。現代の神経科学者の多くは、身体的フィードバックが感情の経験を調節するという、修正された ジェームズ・ランゲの見解を支持するだろう。(p. 583) キャノン-バード理論 ウォルター・ブラッドフォード・キャノンは、生理的反応が感情において重要な役割を果たすことに同意したが、生理的反応だけで主観的な感情体験を説明でき るとは考えなかった。彼は生理的反応はあまりにも遅く、しばしば知覚できないため、感情の比較的迅速で強烈な主観的認識を説明できないと主張した [80]。 また、彼は感情経験の豊かさ、多様さ、時間的経過は、かなり未分化な闘争または逃走反応を反映する生理的反応から生じることはできないと考えた[81] [82]。 この理論の実行例は以下の通りである。感情を誘発する出来事(蛇)は、生理的反応と感情の意識的な経験の両方を同時に誘発する。 フィリップ・バードは動物に関する研究によってこの理論に貢献した。バルドは、感覚、運動、生理の情報はすべて、それ以上の処理を受ける前に、間脳(特に 視床)を通過する必要があることを見つけた。したがってキャノンはまた、感覚的な出来事が意識的な認識を引き起こす前に生理的な反応を引き起こすことは解 剖学的に不可能であり、感情的な刺激は感情の生理的側面と経験的側面の両方を同時に引き起こさないといけないと主張した[81]。 二因子説 主な記事 感情の二要因説(Two-factor theory of emotion スタンレー・シャッターは、スペインの医師であるグレゴリオ・マラニョンが、患者にエピネフリンを注射し、その後にどのように感じるかを尋ねたという初期 の研究に基づいて、この理論を構築した。マラニョンは、患者のほとんどが何かを感じていることを見つけたが、実際に感情を引き起こすような刺激がない限 り、患者は自分の生理的覚醒を経験した感情として解釈することができないのである。シャッターは、生理的反応が感情に大きな役割を果たすことに同意してい た。彼は、生理的反応は、与えられた生理的興奮を認知的に評価することを容易にすることによって、情動体験に貢献し、この評価こそが主観的情動体験を定義 するものであると示唆した。このように、情動は、一般的な生理的覚醒と、情動の経験という2段階のプロセスの結果である。例えば、台所に熊がいる、という 刺激に反応して、心臓がドキドキするという生理的興奮が起こる。そのとき、脳はドキドキを説明するために、すばやく周囲をスキャンし、熊に気づく。その結 果、脳は心臓のドキドキを熊に対する恐怖の結果であると解釈する[83]。シャッターは弟子のジェローム・シンガーとともに、エピネフリンを注射して同じ 生理状態に置かれても、被験者が異なる感情反応を示すことを実証した。被験者は、その場にいる別の人物(共犯者)がその感情を示すかどうかに応じて、怒り や楽しみを表現することが観察された。つまり、状況の評価(認知)とアドレナリンまたはプラセボの投与との組み合わせが反応を決定していたのである。この 実験はJesse Prinz (2004) のGut Reactionsで批判されている[84]。 認知理論 2因子理論が認知を含むようになると、いくつかの理論は判断、評価、または思考の形で認知活動が感情が発生するために完全に必要であると主張し始めた。こ の見解の主唱者の一人がリチャード・ラザロで、感情には何らかの認知的意図性がなければならないと主張した。感情文脈の解釈に関与する認知活動は、意識的 であるか無意識的であるか、また概念的な処理の形をとるかとらないかであろう。 Lazarusの理論は非常に影響力がある。感情は次の順序で起こる障害である。 認知的評価 - 個人が認知的に出来事を評価し、それが感情の手がかりとなる。 生理的変化 - 認知的反応により、心拍数の増加や下垂体副腎反応などの生物学的変化が始まる。 行動 - 個人が感情を感じ、どのように反応するかを選択する。 例えば ジェニーは蛇を見た。 ジェニーは自分の目の前にいる蛇を認知的に評価する。認知によって、彼女はそれが危険であると理解することができます。 彼女の脳は副腎を活性化し、血液中にアドレナリンを送り込み、その結果、心拍が増加する。 ジェニーは悲鳴を上げ、逃げ出す。 Lazarusは、感情の質と強さは認知プロセスを通じて制御されると強調した。これらのプロセスは、人と環境との関係を変化させることによって感情的な 反応を形成する対処戦略を下敷きにしています。 ジョージ・マンドラーは2冊の本(Mind and Emotion, 1975,[85] and Mind and Body.で認知、意識、自律神経系に影響される感情について広範囲な理論的、経験的議論を提供した。Psychology of Emotion and Stress, 1984[86])がある。 感情に関する理論には、感情が生じるためには判断や評価、思考といった認知活動が必要であると主張するものがある。著名な哲学的提唱者はロバート・C・ソ ロモンである(例えば、『情熱・感情・人生の意味』1993年[87])。ソロモンは、感情は判断であると主張する。彼は、認知主義に対する「標準的な反 論」と呼んでいる、何かが恐ろしいという判断は感情の有無にかかわらず起こりうるので、判断は感情と同一視できないという考え方に対応する、よりニュアン スの異なる見解を提示している。ニコ・フリダの提唱する、鑑定が行動傾向につながるという理論もその一例である。 また、情動(情動ヒューリスティック、感情、直感的な反応)が情報を処理し、行動に影響を与えるための近道として使われることが多いことも示唆されている [88]。情動注入モデル(AIM)は1990年代初頭にジョセフ・フォージャスが開発した理論モデルで、情動と気分が人の情報処理能力にどのように作用 するかを説明しようとするものである。 ++++++++++++++++ 知覚理論 知覚を扱う理論は感情を見つけるために1つまたは複数の知覚を使う。[89]感情に関する身体理論と認知理論の最近のハイブリッドは知覚理論である。この 理論は身体的反応が感情の中心であると主張する点でネオ・ジェームス的であるが、認知理論で認識されているように、感情の意味性あるいは感情が何かについ てであるという考えを強調するものである。この理論の新しい主張は、そのような意味づけのために概念に基づく認知は不要であるということである。むしろ、 ある状況によって因果的に引き起こされる身体的変化そのものが、感情の意味内容を認識する。この点で、情動は、視覚や触覚のような、主体と世界との関係を 様々な形で情報提供する能力に類似しているとされる。この見解の洗練された擁護は哲学者ジェシー・プリンツの著書「Gut Reactions」や心理学者ジェームズ・レアードの著書「Feelings」に見つけることができる[84]。 感情的事象理論 感情事象理論はハワード・M・ワイスとラッセル・クロパンツァーノ(1996)によって開発されたコミュニケーションに基づいた理論であり、感情的経験 (特に仕事の文脈で)の原因、構造、結果に注目する[90]。この理論は、感情は出来事によって影響され、引き起こされ、その結果、態度や行動に影響を与 えることを示唆している。また、この理論では、人間は感情エピソードと呼ばれる「時間的に拡張され、根底にあるテーマを中心に組織化された一連の感情状 態」を経験するとし、時間を重視する。この理論は、コミュニケーションレンズから感情をよりよく理解するために多くの研究者によって使われており、 2005年にResearch on Emotion in Organizationsに掲載されたHoward M. Weiss and Daniel J. Bealの論文「Reflections on Affective Events Theory」でさらに見直されている[91]。 情動の位置づけの視点 ポール・E・グリフィスとアンドレア・スカランティーノによって開発された感情に関する状況主義の視点は、心理学における状況主義のアプローチを利用し て、感情の発達とコミュニケーションにおける外部要因の重要性を強調している[92]。この理論は、感情の認知主義者と新ジャームス主義の理論の両方とは 著しく異なり、どちらも感情は純粋に内部のプロセスとして見られ、環境は感情への刺激としてのみ作用している。これに対して、情動の状況論的視点は、情動 を、生物が環境を調査し、他の生物の反応を観察することによって生み出されたものと見なす。感情は、社会的関係の進化を刺激し、他の生物の行動を媒介する 信号として作用する。ある文脈では、感情の表現(自発的、非自発的の両方)は、異なる生物間の取引における戦略的な動きとみなすことができる。情動の状況 的視点は、情動は世界との巧みな関わりの行動指向の形態であるため、概念的思考は情動に固有の部分ではないと述べている。グリフィスとスカランティーノ は、この情動の視点が、恐怖症や、幼児や動物の情動を理解する上で有用であることを示唆した。 遺伝学 感情は、社会的相互作用や人間関係の動機づけとなるため、基本的な生理機能、特にストレス系と直接関係している。このことは、情動が抗ストレス複合体、す なわち絆に大きな役割を果たすオキシトシン-愛着システムと関連していることから重要である。感情表現型の気質は複雑な社会システムにおける社会的なつな がりやフィットネスに影響を与える[93]。これらの特性は他の種や分類群にも共通し、遺伝子とその継続的な伝達による効果である。DNA配列にコード化 された情報は、私たちの細胞を構成するタンパク質を組み立てるための青写真を提供します。接合体は親の生殖細胞からの遺伝情報を必要とし、種分化のたび に、その祖先が生存し繁殖を成功させた遺伝的形質が、子孫にとって潜在的に有益な新しい形質とともに受け継がれる。 現代人とチンパンジーにつながる系統が分かれてから500万年の間に、彼らの遺伝子のわずか1.2%程度が改変されたに過ぎない。このことから、私たちと チンパンジーを分けるものは、私たちの行動も含めて、そのごくわずかなDNAにコード化されているに違いないと考えられる。動物の行動を研究している学生 たちは、遺伝子に依存した行動表現型の種内例を確認したに過ぎない。ハタネズミ(Microtus spp.)では、社会組織と交尾システムにおける大きな種の違いに対応するバソプレシン受容体遺伝子において、わずかな遺伝子の違いが同定されている [94]。行動上の違いを伴うもう一つの潜在的例はFOCP2遺伝子で、これは音声と言語を扱う神経回路に関与している[95]。 [95] ヒトにおけるその現在の形は、チンパンジーのそれとわずかな突然変異によって異なっており、約20万年前から存在しており、現代人の始まりと一致する [96]。 音声、言語、社会組織はすべて感情の基礎の一部である。 |

| Formation Neurobiological explanation Based on discoveries made through neural mapping of the limbic system, the neurobiological explanation of human emotion is that emotion is a pleasant or unpleasant mental state organized in the limbic system of the mammalian brain. If distinguished from reactive responses of reptiles, emotions would then be mammalian elaborations of general vertebrate arousal patterns, in which neurochemicals (for example, dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin) step-up or step-down the brain's activity level, as visible in body movements, gestures and postures. Emotions can likely be mediated by pheromones (see fear).[35] For example, the emotion of love is proposed to be the expression of Paleocircuits of the mammalian brain (specifically, modules of the cingulate cortex (or gyrus)) which facilitate the care, feeding, and grooming of offspring. Paleocircuits are neural platforms for bodily expression configured before the advent of cortical circuits for speech. They consist of pre-configured pathways or networks of nerve cells in the forebrain, brainstem and spinal cord. Other emotions like fear and anxiety long thought to be exclusively generated by the most primitive parts of the brain (stem) and more associated to the fight-or-flight responses of behavior, have also been associated as adaptive expressions of defensive behavior whenever a threat is encountered. Although defensive behaviors have been present in a wide variety of species, Blanchard et al. (2001) discovered a correlation of given stimuli and situation that resulted in a similar pattern of defensive behavior towards a threat in human and non-human mammals.[97] Whenever potentially dangerous stimuli is presented additional brain structures activate that previously thought (hippocampus, thalamus, etc.). Thus, giving the amygdala an important role on coordinating the following behavioral input based on the presented neurotransmitters that respond to threat stimuli. These biological functions of the amygdala are not only limited to the "fear-conditioning" and "processing of aversive stimuli", but also are present on other components of the amygdala. Therefore, it can referred the amygdala as a key structure to understand the potential responses of behavior in danger like situations in human and non-human mammals.[98] The motor centers of reptiles react to sensory cues of vision, sound, touch, chemical, gravity, and motion with pre-set body movements and programmed postures. With the arrival of night-active mammals, smell replaced vision as the dominant sense, and a different way of responding arose from the olfactory sense, which is proposed to have developed into mammalian emotion and emotional memory. The mammalian brain invested heavily in olfaction to succeed at night as reptiles slept – one explanation for why olfactory lobes in mammalian brains are proportionally larger than in the reptiles. These odor pathways gradually formed the neural blueprint for what was later to become our limbic brain.[35] Emotions are thought to be related to certain activities in brain areas that direct our attention, motivate our behavior, and determine the significance of what is going on around us. Pioneering work by Paul Broca (1878),[99] James Papez (1937),[100] and Paul D. MacLean (1952)[101] suggested that emotion is related to a group of structures in the center of the brain called the limbic system, which includes the hypothalamus, cingulate cortex, hippocampi, and other structures. More recent research has shown that some of these limbic structures are not as directly related to emotion as others are while some non-limbic structures have been found to be of greater emotional relevance. Prefrontal cortex There is ample evidence that the left prefrontal cortex is activated by stimuli that cause positive approach.[102] If attractive stimuli can selectively activate a region of the brain, then logically the converse should hold, that selective activation of that region of the brain should cause a stimulus to be judged more positively. This was demonstrated for moderately attractive visual stimuli[103] and replicated and extended to include negative stimuli.[104] Two neurobiological models of emotion in the prefrontal cortex made opposing predictions. The valence model predicted that anger, a negative emotion, would activate the right prefrontal cortex. The direction model predicted that anger, an approach emotion, would activate the left prefrontal cortex. The second model was supported.[105] This still left open the question of whether the opposite of approach in the prefrontal cortex is better described as moving away (direction model), as unmoving but with strength and resistance (movement model), or as unmoving with passive yielding (action tendency model). Support for the action tendency model (passivity related to right prefrontal activity) comes from research on shyness[106] and research on behavioral inhibition.[107] Research that tested the competing hypotheses generated by all four models also supported the action tendency model.[108][109] Homeostatic/primordial emotion Another neurological approach proposed by Bud Craig in 2003 distinguishes two classes of emotion: "classical" emotions such as love, anger and fear that are evoked by environmental stimuli, and "homeostatic emotions" – attention-demanding feelings evoked by body states, such as pain, hunger and fatigue, that motivate behavior (withdrawal, eating or resting in these examples) aimed at maintaining the body's internal milieu at its ideal state.[110] Derek Denton calls the latter "primordial emotions" and defines them as "the subjective element of the instincts, which are the genetically programmed behavior patterns which contrive homeostasis. They include thirst, hunger for air, hunger for food, pain and hunger for specific minerals etc. There are two constituents of a primordial emotion – the specific sensation which when severe may be imperious, and the compelling intention for gratification by a consummatory act."[111] Emergent explanation Emotions are seen by some researchers to be constructed (emerge) in social and cognitive domain alone, without directly implying biologically inherited characteristics. Joseph LeDoux differentiates between the human's defense system, which has evolved over time, and emotions such as fear and anxiety. He has said that the amygdala may release hormones due to a trigger (such as an innate reaction to seeing a snake), but "then we elaborate it through cognitive and conscious processes".[33] Lisa Feldman Barrett highlights differences in emotions between different cultures,[112] and says that emotions (such as anxiety) are socially constructed (see theory of constructed emotion). She says that they "are not triggered; you create them. They emerge as a combination of the physical properties of your body, a flexible brain that wires itself to whatever environment it develops in, and your culture and upbringing, which provide that environment."[113] She has termed this approach the theory of constructed emotion. |

フォーメーション 神経生物学的説明 大脳辺縁系の神経地図作成による発見に基づいて、人間の情動を神経生物学的に説明すると、情動は哺乳類の脳の大脳辺縁系で組織化された快・不快の精神状態 であるとされます。このとき、神経化学物質(例えば、ドーパミン、ノルアドレナリン、セロトニン)が脳の活動レベルを上げたり下げたりして、体の動き、身 振り、姿勢に表れます。感情はおそらくフェロモンによって媒介されることができる(恐怖を参照)[35]。 例えば、愛という感情は、哺乳類の脳の古回路(具体的には帯状皮質(または回)のモジュール)の発現であると提案されており、この回路は子孫の世話、給 餌、およびグルーミングを容易にするものであるとされている。古皮質回路は、発声のための皮質回路が出現する以前に構成された身体表現のための神経基盤で ある。前脳、脳幹、脊髄にある神経細胞の経路やネットワークがあらかじめ構成されている。 恐怖や不安といった感情も、脳の最も原始的な部分(脳幹)でのみ生成され、行動の闘争・逃走反応に関連すると考えられてきたが、脅威が生じたときの防衛行 動の適応的表現として関連付けられてきた。防衛行動は様々な種で見られるが、Blanchardら(2001)は与えられた刺激と状況の相関を発見し、ヒ トとヒト以外の哺乳類で脅威に対する防衛行動の類似パターンをもたらした[97]。 潜在的に危険な刺激が提示されるたびに、それまで考えられていた脳構造がさらに活性化する(海馬、視床など)。このように、扁桃体は、脅威刺激に反応する 神経伝達物質の提示に基づいて、次の行動入力を調整する上で重要な役割を担っているのである。このような扁桃体の生物学的機能は、「恐怖の条件付け」と 「嫌悪刺激の処理」だけにとどまらず、扁桃体の他の構成要素にも存在している。したがって、ヒトやヒト以外の哺乳類における危険な状況下での行動の潜在的 な反応を理解するために、扁桃体を重要な構造として参照することができる[98]。 爬虫類の運動中枢は、視覚、聴覚、触覚、化学物質、重力、運動の感覚的な手がかりに反応し、あらかじめ設定された体の動きとプログラムされた姿勢をとる。 夜間活動的な哺乳類の到来によって、視覚に代わって匂いが支配的な感覚となり、嗅覚から異なる反応の仕方が生じ、それが哺乳類の感情と感情記憶に発展した と提唱されている。哺乳類の脳は、爬虫類が眠っている間に夜間活動を成功させるために嗅覚に大きく投資した。哺乳類の脳の嗅覚小葉が爬虫類よりも割合的に 大きい理由の1つは、このような理由によるものである。これらの匂いの経路は、後に我々の大脳辺縁系となるものの神経設計図を徐々に形成していった [35]。 感情は、注意を向け、行動を動機付け、周りで起こっていることの重要性を判断する脳領域における特定の活動に関連していると考えられている。ポール・ブ ローカ(1878年)[99]、ジェームズ・パペス(1937年)[100]、ポール・D・マクレーン(1952年)[101]による先駆的研究は、情動 が視床下部、帯状皮質、海馬、その他の構造を含む辺縁系という脳の中心部の構造のグループと関連していると示唆するものであった。最近の研究では、これら の辺縁系構造の中には、他の構造ほど情動に直接関係しないものがある一方で、非辺縁系構造の中には、より情動と関連性の高いものがあることが見つかってい る。 前頭前野 もし魅力的な刺激が脳のある領域を選択的に活性化するのであれば、論理的には逆が成り立つはずであり、脳のその領域の選択的活性化は刺激をより肯定的に判 断させるはずである。これは適度に魅力的な視覚刺激に対して実証され[103]、否定的な刺激を含むように再現され拡張された[104]。 前頭前野における感情に関する2つの神経生物学的モデルは相反する予言を行った。価数モデルは、負の感情である怒りが右の前頭前野を活性化すると予測し た。方向性モデルは、怒りは接近する感情であり、左の前頭前野を活性化すると予測した。2番目のモデルが支持された[105]。 このことは、前頭前野における接近の反対は、離れていくこと(方向モデル)、動かないが強さと抵抗があること(運動モデル)、あるいは受動的降伏で動かな いこと(行動傾向モデル)としてよりよく説明されるのかという疑問をまだ残したままであった。行動傾向モデル(右前頭前野の活動に関連する受動性)の支持 は、シャイネスに関する研究[106]や行動抑制に関する研究[107]から得られる。 4つのモデルすべてによって生み出される競合仮説を検証した研究もまた行動傾向モデルを支持した[108][109]。 恒常的・原初的な感情 2003年にBud Craigによって提唱されたもう一つの神経学的アプローチは、感情を2つのクラスに区別するものである。愛、怒り、恐怖といった環境刺激によって喚起さ れる「古典的」感情と、痛み、空腹、疲労といった身体の状態によって喚起され、身体の内部環境を理想的な状態に維持することを目的とした行動(これらの例 では撤退、食事、休憩)を動機づける「恒常性維持感情」である[110]。 デレク・デントンは後者を「原初的感情」と呼び、「本能の主観的要素であり、恒常性を維持するために遺伝的にプログラムされた行動様式である」と定義して いる。喉の渇き、空気への飢え、食べ物への飢え、痛み、特定のミネラルへの飢えなどである。原初的な感情には2つの構成要素がある-厳しいときには命令的 であるかもしれない特定の感覚と、消費的行為による満足のための強制的な意図である」[111]。 創発的説明 感情は生物学的に継承された特徴を直接的に示唆することなく、社会的および認知的領域だけで構築される(出現する)と見る研究者もいる。 ジョセフ・ルドゥーは時間をかけて進化してきた人間の防衛システムと、恐怖や不安などの感情を区別している。彼は扁桃体がトリガー(蛇を見たときの生得的 な反応など)によりホルモンを放出するかもしれないが、「その後、我々は認知的・意識的プロセスを通じてそれを精緻化する」[33]と述べている。 リサ・フェルドマン・バレットは異なる文化間の感情の違いを強調し[112]、感情(不安など)は社会的に構築されるとしている(構築された感情の理論を 参照)。彼女は、それらは「引き金になるのではなく、あなたが創り出すものである」と言う。それらは、あなたの身体の物理的特性、それが発達するどんな環 境にも自分自身を配線する柔軟な脳、そしてその環境を提供するあなたの文化と生い立ちの組み合わせとして出現する」[113]と彼女はこのアプローチを構 築された感情の理論と呼んでいる。 |

| Affect measures Affective forecasting Emotion and memory Emotion Review Emotional intelligence Emotional isolation Emotions in virtual communication Facial feedback hypothesis Fuzzy-trace theory Group emotion Moral emotions Social sharing of emotions Two-factor theory of emotion |

情動測定 情動予測 感情と記憶 感情レビュー 感情知能 感情的孤立 仮想コミュニケーションにおける感情 顔面フィードバック仮説 ファジー・トレース理論 集団感情 道徳的感情 感情の社会的共有 感情の二要因理論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emotion |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

☆Les Passions de l'âme (魂の情念:デカルトの作品)

Elisabeth of Bohemia (1636)/ボボヘミアのエリザベート王女

| Les

Passions de l'âme

(parfois appelé Traité des passions de l'âme) est un traité

philosophique écrit par René Descartes et publié à Paris en 1649. Il

s'agit du dernier livre de Descartes publié de son vivant. Celui-ci est

écrit en français et dédié à la Princesse Élisabeth de Bohême. Dans cette œuvre, Descartes se concentre sur la question des passions. Il s'agit donc d'un traité de philosophie morale, le dernier domaine de la philosophie abordé par Descartes. Celui-ci s'inscrit, avec cet ouvrage, dans la tradition de la réflexion philosophique sur les passions, tout en abordant ces dernières d'un point de vue physiologique novateur car précurseur de la neurophysiologie. Ce traité est aussi l'occasion pour Descartes d'éclaircir plusieurs problèmes qu'il avait posés dans ses précédents ouvrages. Ainsi, concernant le problème de l'interaction corps-esprit, il propose dans cet ouvrage des théories sur les « esprits-animaux » et le rôle selon lui central de la glande pinéale (ou épiphyse), établissant un lien entre les émotions humaines et la chimie du corps. Par ailleurs, concernant la théorie de l'action, Descartes présente une philosophie morale plus aboutie que les règles provisoires qu'il avait ébauchées dans les Discours de la méthode, et fondée sur la connaissance des lois physiologiques. |

『魂の情念』(『魂の情念に関する論文』とも呼ばれる)は、ルネ・デカ

ルトによって書かれ、1649年にパリで出版された哲学論文である。これはデカルトが生前に出版した最後の著書である。この著作はフランス語で書かれてお

り、ボヘミアのエリザベート王女に捧げられている。 この作品の中で、デカルトは情念の問題に焦点を当てている。したがって、これは道徳哲学の論文であり、デカルトが取り組んだ哲学の最後の分野である。この 著作は、情念に関する哲学的考察の伝統に則りながら、神経生理学の先駆けとなる革新的な生理学的観点から情念を論じている。 また、この論文は、デカルトがこれまでの著作で提起してきたいくつかの問題を解明する機会ともなった。例えば、心身の相互作用の問題に関しては、この著作 の中で「動物精神」に関する理論と、松果体(エピフィシス)が果たす中心的な役割について論じ、人間の感情と体の化学的反応との関連性を明らかにしてい る。また、行動の理論に関しては、デカルトは『方法序説』で概説した暫定的な規則よりも完成度の高い道徳哲学を提示し、それは生理学的法則の知識に基づい ている。 |

| Genèse et sens du traité Origine de l'œuvre Descartes entame en 1643 une abondante correspondance écrite avec la Princesse Élisabeth de Bohême (voir Correspondance avec Élisabeth), dans laquelle il traite de questions de morale en réponse aux interrogations de la Princesse, en particulier sur le bonheur, les passions et la manière de conduire sa vie. Le Traité des passions de l'âme se présente comme une synthèse du résultat de ces échanges épistolaires. |

やりとりの起源と意味 作品の起源 デカルトは1643年、ボヘミアのエリザベート王女と豊富な書簡のやり取りを始めた(エリザベートとの書簡を参照)。その書簡の中で、彼は王女の質問、特 に幸福、情念、人生の生き方について、道徳的な問題について論じている。『魂の情念に関する論文』は、この文通の成果をまとめたものとなっている。 |

| Rapport entre philosophie morale

et science Dans le contexte scientifique du xviie siècle, qui abandonne l'idée de cosmos au profit d'un univers ouvert dont il importe de saisir les lois (voir Alexandre Koyré), l'action humaine ne dépend plus (à l'inverse de ce que pensait la philosophie grecque) de la connaissance de l'ordre de l'univers, mais plutôt de la connaissance de la nature, dont l'humain est un élément. Pour bien agir, il faut étudier et connaître la nature dans son fonctionnement intime. C'est pourquoi Descartes veut parler des passions, non pas comme un moraliste, ni dans une perspective psychologique, mais avant tout en s'appuyant sur la science de la nature : « Mon dessein n’a pas été d’expliquer les passions en Orateur, ni même en Philosophe, mais seulement en Physicien » (Lettre à son éditeur, 14 août 1649). En cela, Descartes rompt non seulement avec la tradition aristotélicienne, pour laquelle les mouvements du corps ont leur origine dans l'âme[1], mais aussi avec les traditions stoïcienne et chrétienne, pour lesquelles les passions sont des maladies de l'âme, qu'il faut traiter comme telles. Descartes peut ainsi affirmer que les passions « sont toutes bonnes de leur nature, et nous n’avons rien à éviter que leurs mauvais usages ou leurs excès » (Les passions de l’âme, art. 211). Dans le contexte de la vision mécaniste du vivant, liée à l'apparition de la science moderne au xviie siècle, Descartes conçoit le corps comme une machine disposant d'une certaine autonomie : il peut se mouvoir indépendamment de l'âme. D'où cette approche physiologique des passions de l'âme. Autrefois conçues comme une anomalie, les passions deviennent un objet naturel dont il s'agit d'expliquer le fonctionnement. |

道徳哲学と科学の関係 17世紀の科学の文脈では、宇宙の概念は放棄され、その法則を理解することが重要な、開かれた宇宙という概念が採用された(アレクサンドル・コイレ参 照)。そのため、人間の行動は(ギリシャ哲学が考えていたこととは逆に)、宇宙の秩序に関する知識に依存するものではなく、人間もその一部である自然に関 する知識に依存するものとなった。正しい行動をとるためには、自然の内部の仕組みを研究し、理解しなければならない。 そのため、デカルトは、道徳家として、また心理学的観点からではなく、何よりも自然科学に基づいて、情念について語ろうとしている。「私の意図は、演説家 として、あるいは哲学者として情念を説明することではなく、物理学者としてのみ説明することである 」(1649年8月14日付の出版者への手紙)。この点で、デカルトは、身体の動きは魂に起源があるとするアリストテレスの伝統[1]だけでなく、情念は 魂の病気であり、そのように扱うべきであるとするストア派やキリスト教の伝統とも決別している。したがってデカルトは、情念は「その性質上、すべて良いも のであり、我々が避けるべきは、その誤用や過剰だけである」と断言できるのだ(『魂の情念』第211条)。 17世紀の近代科学の出現に伴う、生命の機械論的見解の文脈において、デカルトは身体を一定の自律性を持つ機械として捉えている。つまり、身体は魂とは独 立して動くことができる。そこから、魂の情念に対する生理学的アプローチが生まれたのである。かつては異常と捉えられていた情念は、その機能を説明すべき 自然の対象となった。 |

La notion de « passion » Portrait de Descartes par Jan Baptist Weenix, vers 1648 (Centraal Museum, Utrecht). Le traité s'appuie sur la philosophie que Descartes a développée dans ses précédents ouvrages, en particulier à propos de la distinction de l'âme et du corps : l’âme est une chose qui pense (« res cogitans »), inétendue et sans parties ; le corps est une chose étendue (« res extensa ») et qui ne pense pas, principalement définie par son étendue, sa forme et son mouvement. C'est ce qu'on appelle le dualisme cartésien. Mais ce traité est l'occasion d'approfondir surtout le mystère de l'union de ces deux substances (la pensée et le corps). Les passions telles que Descartes les comprend correspondent en effet approximativement à ce qu'on appelle aujourd'hui les « émotions ». Mais il existe des différences significatives entre ce qu'on appelait « passion » à l'époque, et ce qu'on appelle « émotion » de nos jours. La principale d'entre elles est que les passions, comme le suggère l'étymologie du mot[2], sont de nature passive ou subie, c'est-à-dire que l'expérience d'une passion est causée par un objet extérieur au sujet. Alors que, dans la psychologie contemporaine, une émotion est généralement conçue comme un événement qui se déroule à l'intérieur du sujet, et par conséquent plutôt produite par le sujet. Dans les Passions de l'âme, Descartes définit les passions comme « des perceptions ou des sentiments, ou des émotions de l’âme, qu’on rapporte particulièrement à elle, et qui sont causées, entretenues et fortifiées par quelque mouvement des esprits » (art. 27). Les « esprits » mentionnés ici sont les esprits animaux, notion centrale pour comprendre la physiologie de Descartes. Ceux-ci fonctionnent de façon semblable à la manière dont la médecine comprend aujourd'hui le système nerveux. Descartes explique que ces esprits animaux sont produits par le sang, et sont responsables des stimulations des mouvements du corps. En affectant les muscles, par exemple, les esprits animaux « meuvent le corps en toutes les diverses façons qu’il peut être mû » (art. 10). Descartes ne rejette donc pas a priori les passions, il en souligne même le rôle bénéfique dans l'existence humaine : « La Philosophie que je cultive n’est pas si barbare ni si farouche qu’elle rejette l’usage des passions ; au contraire, c’est en lui seul que je mets toute la douceur et la félicité de cette vie » (Lettre au Marquis de Newcastle, mars ou avril 1648). Il s'agit plutôt de mieux comprendre leur mécanisme, pour les maîtriser davantage au lieu d'en pâtir. Ainsi, « ceux mêmes qui ont les plus faibles âmes pourraient acquérir un empire très absolu sur toutes leurs passions, si on employait assez d'industrie à les dresser et à les conduire » (art. 50). |

「情念」という概念 ヤン・バプティスト・ウェニックスによるデカルトの肖像、1648年頃(セントラル美術館、ユトレヒト)。 この論文は、デカルトが以前の著作、特に魂と身体の区別について展開した哲学に基づいている。魂は思考する存在(「res cogitans」)であり、広がりも部分も持たない。体は、思考能力を持たない、広がりのあるもの(「res extensa」)であり、主にその広がり、形、動きによって定義される。これは、デカルトの二元論として知られる。しかし、この論文は、とりわけ、この 二つの物質(思考と体)の結合という謎を深く掘り下げる機会となっている。 デカルトが理解する情念は、今日の「感情」とほぼ同じである。しかし、当時「情念」と呼ばれていたものと、今日の「感情」とは、重要な違いがある。その主 な違いは、情念は、その語源が示唆するように、受動的あるいは被動的な性質を持つ、つまり情念の経験は、主体以外の対象によって引き起こされるということ だ。一方、現代心理学では、感情は一般的に、主体の中で起こる出来事、つまり主体によって生み出されるものと理解されている。 『魂の情念』の中で、デカルトは情念を「知覚や感情、あるいは魂の感情であり、特に魂に関連し、精神の動きによって引き起こされ、維持され、強化されるも の」と定義している(第27条)。ここで言及されている「精神」とは、デカルトの生理学を理解する上で中心的な概念である動物精神のことだ。これは、今日 の医学が神経系を理解している方法とよく似ている。デカルトは、この動物精神は血液によって生み出され、身体の動きを刺激する役割を担っていると説明して いる。例えば、筋肉に影響を与えることで、動物精神は「身体をあらゆる方法で動かす」のである(第10条)。 したがって、デカルトは情念を先入観で否定しているわけではなく、人間の存在におけるその有益な役割を強調している。「私が追求する哲学は、情念の利用を 否定するほど野蛮でも過激でもない。それどころか、私はこの人生のすべての喜びと幸福を情念にのみ求めている」 (ニューカッスル侯爵への手紙、1648年3月または4月)。むしろ、情念のメカニズムをよりよく理解し、それに苦しむのではなく、よりよく制御すること である。したがって、「最も弱い魂を持つ者たちでさえ、彼らを訓練し、導くために十分な努力を払えば、あらゆる情念に対して絶対的な支配力を獲得すること ができる」のである(第50条)。 |

| Organisation du traité L'organisation du traité de Descartes est significative de la philosophie de l'auteur. En effet, appliquant sa fameuse méthode[3] à la philosophie morale, Descartes décompose le problème des passions de l'âme dans ses parties les plus simples, les plus élémentaires. Il distingue dans cette perspective six passions fondamentales, six passions claires et distinctes : « On peut facilement remarquer qu'il n'y en a que six qui soient telles [simples et primitives] ; à savoir l'admiration, l'amour, la haine, le désir, la joie et la tristesse ; et que toutes les autres sont composées de quelques-unes de ces six, ou bien en sont des espèces. — Descartes, Les Passions de l'âme, art. 69[4]. » C'est à partir de ces six passions primitives (l'admiration, l'amour, la haine, le désir, la joie, la tristesse) que Descartes commence son investigation sur leurs effets physiologiques et leurs implications sur le comportement humain. Il va ensuite combiner ces six passions entre elles pour retrouver l'ensemble du spectre des passions. L'ouvrage est divisé en trois grandes parties intitulées : Des passions en général, et par occasion de toute la nature de l'homme ; Du nombre et de l'ordre des passions et l'explication des six primitives ; Des passions particulières. Le traité se subdivise, au sein de ces trois grandes parties, en 212 courts articles, qui font rarement plus de quelques paragraphes. La manière très systématique de procéder de Descartes n'est pas sans annoncer l'intérêt de Leibniz pour la combinatoire ou l'Éthique de Spinoza. Partant, au début de l'ouvrage, d'une affirmation de la tradition selon laquelle action et passion sont deux noms pour une seule et même chose selon que nous considérons ce qui la produit (action) ou celui qui la supporte (passion), Descartes en déduit la nécessité de distinguer les fonctions (l'activité) du corps (articles 7 à 16) des fonctions de l'âme (art. 17 à 26), pour arriver à la définition des passions (art. 27 à 29) et pour étudier l'interaction de l'âme et du corps (art. 30 à 39), ce qui permettra d'affirmer le pouvoir de l'âme sur le corps (art. 41 à 50). |

やりとりの構成 デカルトの条約(=やりとり)の構成は、著者の哲学を象徴している。実際、彼の有名な方法[3]を道徳哲学に適用し、デカルトは魂の情念の問題を最も単純 で基本的な要素に分解している。この観点から、彼は6つの基本的な情念、6つの明確かつ異なる情念を区別している。 「そのような(単純で原始的な)情念は6つしかないことは容易に理解できる。すなわち、賞賛、愛、憎しみ、欲望、喜び、悲しみである。他のすべての情念 は、この6つのうちのいくつかで構成されているか、あるいはその一種である。 — デカルト、『魂の情念』、第69条[4]。」 デカルトは、この6つの原始的な情念(賞賛、愛、憎しみ、欲望、喜び、悲しみ)から、それらの生理学的効果や人間の行動への影響についての調査を始めた。 そして、この6つの情念を組み合わせて、情念の全容を明らかにしていく。 この著作は、以下の3つの大きな部分に分かれている。 情念全般、および人間の本性全般について 情念の数と順序、および6つの原始的な情念の説明 特定の情念 この論文は、これら3つの大きな部分の中で、212の短い記事に分かれており、そのほとんどは数段落以上の長さではない。デカルトの非常に体系的な手法 は、ライプニッツの組み合わせ論やスピノザの『倫理学』への関心を予見するものである。 したがって、この著作の冒頭で、行動と情念は、それを生み出すもの(行動)とそれを耐えるもの(情念)のどちらを考慮するかによって、同じものの2つの名 称であるとする伝統的な主張から出発し、 そこから、身体の機能(活動)(第7条から第16条)と魂の機能(第17条から第26条)を区別する必要性を導き出し、受動の定義(第27条から第29 条)に到達し、魂と身体の相互作用(第30条から第39条)を研究する。これにより、魂が身体に対して持つ力(第41条から第50条)を主張することが可 能となる。 |

Problèmes philosophiques en jeu Illustration du rapport corps-esprit par Descartes. Les entrées sensorielles sont transmises par les organes sensoriels à la glande pinéale dans le cerveau, puis à l’esprit immatériel. Le statut du sujet Cela peut sembler surprenant au premier abord, mais le traité des Passions de l'âme est certainement le livre le plus important de toute l'œuvre de Descartes[5]. En effet, si Descartes écrit ce livre, c'est en partie parce qu'il est en proie à un problème philosophique aigu. Ce problème risquerait même de détruire tout l'édifice cartésien. Le problème est le suivant : les passions, inextricablement liées à la nature humaine, mettent en danger la suprématie du sujet pensant que Descartes avait mis au centre de son système philosophique, notamment dans le Discours de la méthode. Descartes avait fait du sujet pensant (« Je suis, j'existe, toutes les fois que je pense ») le fondement de la certitude objective, il en avait fait la base de la possibilité de connaître le monde. Or si les passions perturbent l'être humain, autant dans son comportement que dans ses pensées, comment encore croire à ce sujet tout puissant ? Comment le rapport au réel de l'humain n'est-il pas biaisé, comment en être sûr ? |

哲学的な問題 デカルトによる心身の関係の説明。感覚器官から脳内の松果体へ、そして非物質的な精神へと感覚入力が伝達される。 主題の地位 一見意外に思えるかもしれないが、『魂の情念』は、デカルトの全著作の中で間違いなく最も重要な本だ。実際、デカルトがこの本を書いた理由の一つは、彼が 深刻な哲学的問題に悩まされていたからだ。この問題は、デカルトの哲学体系全体を破壊する恐れさえあった。 その問題とは、人間の本性に密接に結びついた情念が、デカルトが、特に『方法序説』において、その哲学体系の中心に据えた、思考する主体の優位性を脅かす というものである。デカルトは、思考する主体(「私は考える、だから私は存在する」)を客観的な確信の基盤とし、世界を知ることの可能性の基礎とした。し かし、情念が人間の行動や思考を乱すならば、この全能の主体をどうして信じ続けられるだろうか?人間の現実との関係が偏っていないと、どうして確信できる だろうか? |

| Le rapport corps-esprit Le problème du traité des passions est aussi le problème du dualisme cartésien. Dans la première partie de son ouvrage, Descartes s'interroge sur le lien qui existe entre la substance pensante et le corps. Pour Descartes, le seul lien entre les deux substances est la glande pinéale (art. 31), lieu où l'âme est rattachée au corps en quelque sorte. Les passions que Descartes étudie sont en réalité les actions du corps sur l'âme (art. 25). L'âme pâtit de l'influence du corps et est soumise entièrement à l'influence des passions. Dans la manière qu'a Descartes d'expliquer le corps humain, les esprits animaux (qui sont des espèces de corpuscules très subtils véhiculés dans le sang) viennent titiller la glande pinéale et causent maints troubles dans l'âme. |

心と体の関係 情念に関する論考の問題は、デカルトの二元論の問題でもある。著作の最初の部分で、デカルトは思考する物質と体との関連について考察している。デカルトに とって、この二つの物質を結びつける唯一のものは松果体(第31条)であり、そこでは魂が体にある意味で結びついている。 デカルトが研究する情念は、実際には身体による魂への作用である(第25条)。魂は身体の影響を受け、情念の影響に完全に支配されている。デカルトが人体 を説明する方式では、動物情(血液中に運ばれる非常に微細な粒子の一種)が松果体を刺激し、魂にさまざまな混乱を引き起こす。 |

| La combinatoire des passions Les passions attaquent l'âme et celle-ci, aveuglée, pousse le corps à agir de telle ou telle façon inappropriée. Il est donc nécessaire pour Descartes d'étudier dans la deuxième partie du traité les effets particuliers des passions, et la façon dont elles se manifestent. L'étude des passions permettra par la suite de mieux appréhender ces éléments perturbateurs de la raison. Mais il faut tout de même noter toute la modernité de Descartes. En effet, celui-ci ne jette jamais le ban sur les passions, comme des tares de la nature humaine à éviter à tout prix. Elles sont inhérentes à la nature humaine, et elles ne doivent pas être prises pour des aberrations. D'ailleurs le rôle des passions pour le corps n'est pas anodin. Descartes indique qu'elles doivent être utilisées pour savoir ce qui est bon ou nuisible pour le corps, et donc pour l'individu (art. 211 et 212). Ainsi passe-t-il la majeure partie du traité à dénombrer les passions et leurs effets. Il commence par les six passions primitives avant de s'attaquer aux passions particulières qui découlent de leur combinaison. Par exemple, le mépris et l'estime sont toutes deux des passions dérivées de la passion plus primitive : l'admiration (art. 150). La passion que Descartes estime le plus est sans conteste la générosité pour ce qu'elle apporte à l'homme (art. 153). |

情念の組み合わせ 情念は魂を攻撃し、魂は盲目になって、体を不適切な行動へと駆り立てる。したがって、デカルトは、この論文の第二部で、情念の特定の効果と、それがどのよ うに現れるかを研究する必要がある。情念の研究は、その後、理性を乱すこれらの要素をよりよく理解することを可能にするだろう。 しかし、デカルトの現代性にも注目すべきだ。彼は、情念を、何としても避けるべき人間性の欠陥として非難することは決してない。情念は人間性に内在するも のであり、異常とみなすべきではない。さらに、情念は身体にとって重要な役割を担っている。デカルトは、情念は、身体、ひいては個人にとって何が良くて何 が悪いかを知るために利用すべきだと述べている(第211条および第212条)。 こうして彼は、この論文の大部分を、情念とその影響を列挙することに費やしている。彼は、6つの原始的な情念から始め、それらの組み合わせから生じる特定 の情念について論じている。例えば、軽蔑と尊敬は、どちらもより原始的な情念である賞賛から派生した情念である(第150条)。 デカルトが最も高く評価する情念は、人間にもたらすものから見て、間違いなく寛大さである(第153条)。 |

| Contrôler les passions Pour Descartes, rien n'est donc plus nuisible à l'âme, et donc à la pensée qui est sa fonction propre (art. 17), que le corps (art. 2). Mais comme nous l'avons dit, les passions ne sont pas nuisibles en elles-mêmes. Pour sauvegarder l'indépendance de la pensée et garantir à l'homme une connaissance certaine du réel, Descartes indique qu'il est nécessaire de connaître les passions, et de savoir les contrôler pour en faire le meilleur usage possible. Il faut aussi que l'homme parvienne à se maîtriser au point de parfaire la séparation qui existe entre la substance pensante et le corps. |

情念を制御する デカルトにとって、魂、ひいては魂の本来の機能である思考(第17条)にとって、身体(第2条)ほど有害なものはない。しかし、前述したように、情熱はそ れ自体が有害というわけではない。思考の独立性を守り、人間に現実を確実に認識させるためには、デカルトは、情念を知り、それを制御して最大限に活用する 方法を知る必要があると述べている。また、人間は、思考する実体と身体との分離を完全なものにするほど、自分自身を制御できるほどになる必要がある。 |

| Notes et références 1. Voir Aristote, De l'âme. 2. Le mot « passion » vient du latin patior : « souffrir, subir ». Le sens premier du mot « passion » est donc : toute émotion subie par l'âme. 3. « Le troisième [précepte], de conduire par ordre mes pensées, en commençant par les objets les plus simples et les plus aisés à connaître, pour monter peu à peu, comme par degrés, jusques à la connaissance des plus composés [...] » (R. DESCARTES, Discours de la méthode suivi des Méditations, Paris, Éditions Montaigne, 1951, p. 38, 2e partie de l'ouvrage). 4. René Descartes, Les Passions de l'âme, LGF, coll. « Poche », Paris, 1990, p. 84. Nous indiquerons désormais les références au traité en signalant simplement le numéro de l'article concerné, directement dans le corps du texte 5. C'est aussi l'avis de Michel Meyer dans son introduction à l'édition du traité : René Descartes, Les Passions de l'âme, LGF, coll. « Poche », Paris, 1990, p. 5 (introduction de Michel Meyer). |

注釈と参考文献 1. アリストテレス『魂について』を参照。 2. 「情念」という言葉は、ラテン語の patior(「苦しむ、耐える」)に由来する。したがって、「情念」という言葉の本来の意味は、魂が経験するあらゆる感情である。 3. 「第三の(教訓)は、最も単純で理解しやすい対象から始め、段階的に、より複雑な対象へと徐々に進んでいくことで、自分の考えを秩序立てて導くことである [...] 」(R. DESCARTES, Discours de la méthode suivi des Méditations, Paris, Éditions Montaigne, 1951, p. 38, 2e partie de l『ouvrage)。 4. René Descartes, Les Passions de l』âme, LGF, coll. 「Poche」, Paris, 1990, p. 84. 今後、この論文への参照は、該当する項目の番号を本文中に直接記載することで示す 5. ミシェル・マイヤーも、この論文の版への序文で同様の見解を示している:ルネ・デカルト『魂の情念』、LGF、「ポケット」シリーズ、パリ、1990年、 5ページ(ミシェル・マイヤーによる序文)。 |