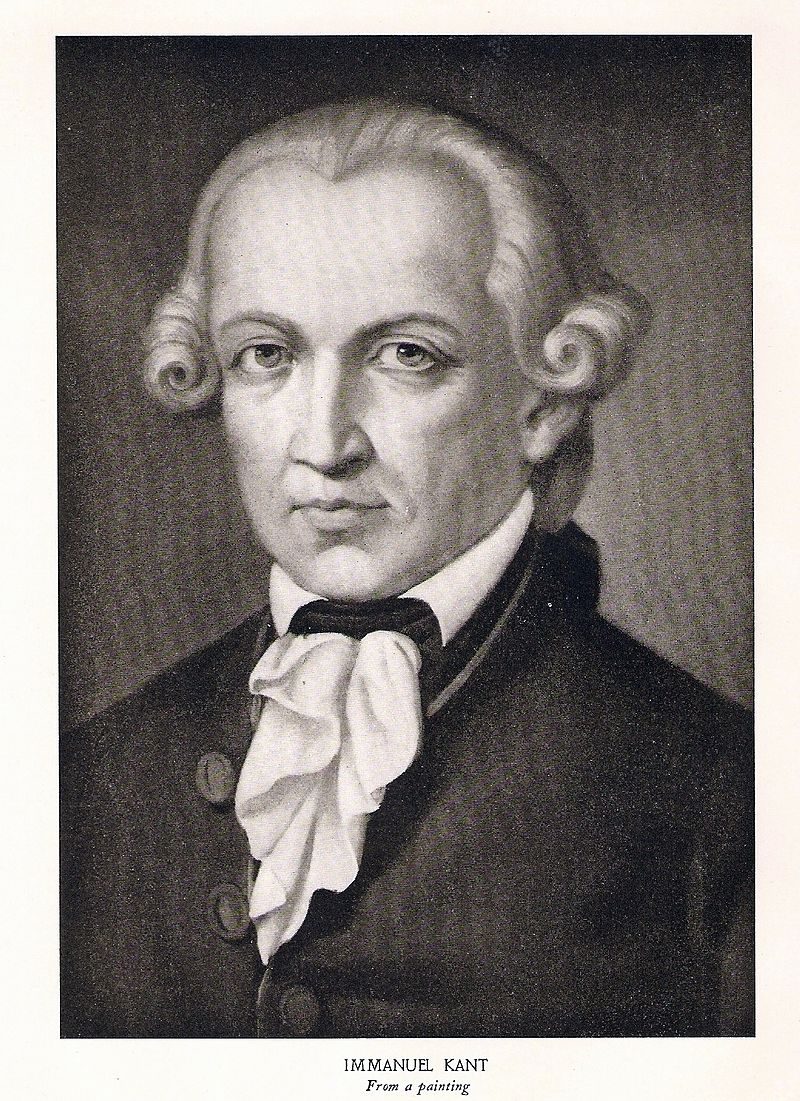

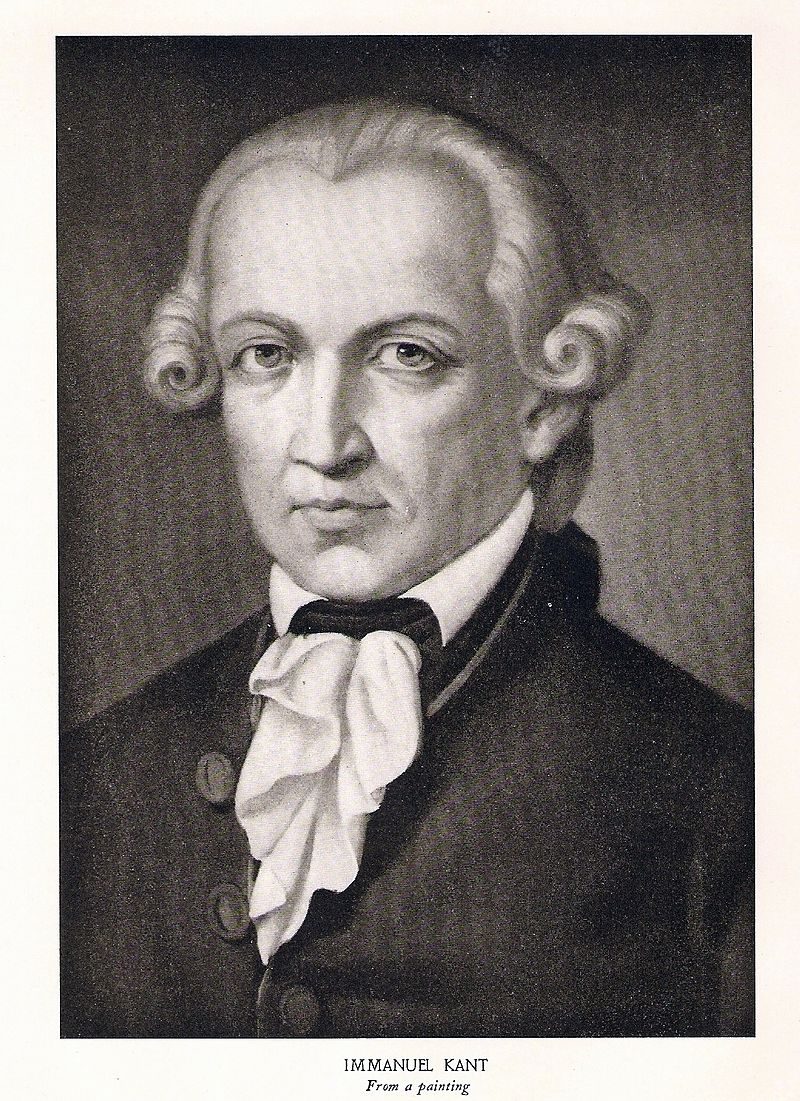

Immanuel

Kant, 1724-1804

デプラー画のエッチングによるImmanuel Kant 1791年

Immanuel

Kant, 1724-1804

デプラー画のエッチングによるImmanuel Kant 1791年

このページでは、カントの生涯を中心に、その思想的影響力などについて紹介します。カントの理論については「カント入門」を参照してください(→カント年譜)。

| Immanuel Kant

(* 22. April 1724 in Königsberg (Preußen); † 12. Februar 1804 ebenda)

war ein deutscher Philosoph der Aufklärung sowie unter anderem

Professor der Logik und Metaphysik in Königsberg. Kant zählt zu den

bedeutendsten Vertretern der abendländischen Philosophie. Sein Werk

Kritik der reinen Vernunft kennzeichnet einen Wendepunkt in der

Philosophiegeschichte und den Beginn der modernen Philosophie. Kant schuf eine neue, umfassende Perspektive in der Philosophie, welche die Diskussion bis ins 21. Jahrhundert maßgeblich beeinflusst. Dazu gehört nicht nur sein Einfluss auf die Erkenntnistheorie und Metaphysik mit der Kritik der reinen Vernunft, sondern auch auf die Ethik mit der Kritik der praktischen Vernunft und die Ästhetik mit der Kritik der Urteilskraft. Zudem verfasste Kant bedeutende Schriften zur Religions-, Rechts- und Geschichtsphilosophie sowie Beiträge zur Astronomie und den Geowissenschaften. Immanuel Kant (UK: /kænt/,[1][2] US: /kɑːnt/,[3][4] German: [ɪˈmaːnu̯eːl ˈkant];[5][6] 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher (a native of the Kingdom of Prussia) and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics have made him one of the most influential figures in modern Western philosophy. In his doctrine of transcendental idealism, Kant argued space and time are mere "forms of intuition" that structure all experience and that the objects of experience are mere "appearances". The nature of things as they are in themselves is unknowable to us. In an attempt to counter the philosophical doctrine of skepticism, he wrote the Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1787), his most well-known work. Kant drew a parallel to the Copernican revolution in his proposal to think of the objects of experience as conforming to our spatial and temporal forms of intuition and the categories of our understanding, so that we have a priori cognition of those objects. Kant believed that reason is the source of morality, and that aesthetics arises from a faculty of disinterested judgment. Kant's religious views were deeply connected to his moral theory. Their exact nature, however, remains in dispute. He hoped that perpetual peace could be secured through universal democracy and international cooperation. His cosmopolitan reputation, however, is called into question by his promulgation of scientific racism for much of his career, even though he changed those views in the last decade of his life. ︎︎︎︎ |

イ

マヌエル・カント(* 1724年4月22日ケーニヒスベルク(プロイセン)、†

1804年2月12日同)は、啓蒙主義のドイツの哲学者で、とりわけケーニヒスベルクの論理学と形而上学教授であった。カントは、西洋哲学の最も重要な代

表者の一人である。彼の著作『純粋理性批判』は、哲学史の転換点であり、近代哲学の始まりである。 カントは哲学において新しい包括的な視点を生み出し、21世紀に至るま で議論に決定的な影響を及ぼしてきた。これには、『純粋理性批判』による認識論や形而上 学への影響だけでなく、『実践理性批判』による倫理学や『判断力批判』 による美学への影響も含まれる。さらに、カントは宗教哲学、法学、歴史学に関する重要な著作を残し、天文学や地球科学にも貢献した。 イマヌエル・カント(1724年4月22日 - 1804年2月12日)は、ドイツの哲学者(プロイセン王国出身)であり、啓蒙思想の中心人物 の一人である。ケーニヒスベルクに生まれたカントは、認識 論、形而上学、倫理学、美学における包括的かつ体系的な著作によって、近代西洋哲学において最も影響力のある人物の一人となった。 カントは、超越論的観念論の教義において、空間と時間はすべての経験を構成する単なる「直観の形式」であり、経験の対象は単なる「外観」であると主張し た。物事の本質がそれ自体であることは、私たちにはわからないのである。懐疑主義という哲学的教義に対抗するために、彼は最もよく知られた著作である 『純粋理性批判』(1781/1787)を書いた。カントは、コペルニクス革命と並行し て、経験の対象を、私たちの空間的・時間的直観形態と理解のカテゴ リーに適合するものとして考え、それらの対象について先験的に認識することを提案した(→コペルニクス的転回)。 カントは、理性が道徳の源であり、美学は無欲な判断力から生まれると考えた。カントの宗教観は、彼 の道徳論と深く結びついていた。しかし、その正確な性質 については、今も論争が続いている。カントは、普遍的な民主主義と国際協調によって、恒久的な平和が確保されることを望んでいた。しかし、カントの国際的 な評価は、科学的な人種差別主義をその生涯の大半に おいて広めたことで、疑問視されている。 |

| ︎︎https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immanuel_Kant |

(→「啓蒙思想

の中に人種主義が潜んでいる」) |

| Immanuel Kant[a]

(22

April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the

central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's

comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics,

ethics, and aesthetics have made him one of the most influential and

controversial figures in modern Western philosophy.[7][8][9] In his doctrine of transcendental idealism, Kant argued space and time are mere "forms of intuition" that structure all experience and that the objects of experience are mere "appearances". The nature of things as they are in themselves is unknowable to us. In an attempt to counter the philosophical doctrine of skepticism, he wrote the Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1787), his best-known work. Kant drew a parallel to the Copernican revolution in his proposal to think of the objects of experience as conforming to our spatial and temporal forms of intuition and the categories of our understanding, so that we have a priori cognition of those objects. These claims have proved especially influential in the social sciences, particularly sociology and anthropology, which regard human activities as pre-oriented by cultural norms.[10] Kant believed that reason is the source of morality, and that aesthetics arises from a faculty of disinterested judgment. Kant's religious views were deeply connected to his moral theory. Their exact nature, however, remains in dispute. He hoped that perpetual peace could be secured through an international federation of republican states and international cooperation. His Cosmopolitan reputation, however, is called into question by his promulgation of scientific racism for much of his career, although he altered his views on the subject in the last decade of his life.  |

イマヌエル・カント[a](1724年4月22日 -

1804年2月12日)はドイツの哲学者であり、啓蒙思想の中心的思想家の一人である。ケーニヒスベルクに生まれたカントは、認識論、形而上学、倫理学、

美学における包括的かつ体系的な著作によって、近代西洋哲学において最も影響力があり、論争的な人物の一人となった[7][8][9]。 カントは超越論的観念論の教義において、空間と時間はすべての経験を構造化する単なる「直観の形式」であり、経験の対象は単なる「出現」であると主張し た。物事の本質を知ることはできない。懐疑主義の哲学的教義に対抗する試みとして、彼は最もよく知られた著作である『純粋理性批判』 (1781/1787)を書いた。カントはコペルニクス革命と並行して、経験の対象を我々の空間的・時間的直観形態と理解の範疇に適合するものとして考え ることで、それらの対象をアプリオリに認識することを提案した。これらの主張は、人間の活動を文化的規範によって事前に方向づけられたものとみなす社会科 学、特に社会学や人類学において特に影響力を持つことが証明されている[10]。 カントは理性が道徳の源であり、美学は利害関係のない判断力から生じると信じていた。カントの宗教観は彼の道徳論と深く結びついていた。しかし、その正確 な性質については論争が続いている。カントは、共和制国家の国際連合と国際協力によって恒久的な平和が確保されることを望んだ。しかし、カントのコスモポ リタンとしての評価は、晩年の10年間は科学的人種差別を改めたものの、そのキャリアの大半は科学的人種差別を広めていたことから疑問視されている。  |

| Biography Immanuel Kant was born on 22 April 1724 into a Prussian German family of Lutheran Protestant faith in Königsberg, East Prussia (since 1946 the Russian city of Kaliningrad). His mother, Anna Regina Reuter (1697–1737), was born in Königsberg to a father from Nuremberg.[11] Her surname is sometimes erroneously given as Porter. Kant's father, Johann Georg Kant (1682–1746), was a German harness-maker from Memel, at the time Prussia's most northeastern city (now Klaipėda, Lithuania). It is possible that the Kants got their name from the village of Kantvainiai (German: Kantwaggen – today part of Priekulė) and were of Kursenieki origin.[12][13] Baptized Emanuel, Kant later changed the spelling of his name to Immanuel after learning Hebrew.[14] He was the fourth of nine children (six of whom reached adulthood).[15] The Kant household stressed the pietist values of religious devotion, humility, and a literal interpretation of the Bible.[16] The young Immanuel's education was strict, punitive and disciplinary, and focused on Latin and religious instruction over mathematics and science.[17] In his later years, Kant lived a strictly ordered life. It was said that neighbors would set their clocks by his daily walks. He never married but seems to have had a rewarding social life; he was a popular teacher as well as a modestly successful author, even before starting on his major philosophical works.[18] |

バイオグラフィー イマヌエル・カントは1724年4月22日、東プロイセンのケーニヒスベルク(1946年以降はロシアのカリーニングラード)でルター派プロテスタントを 信仰するプロイセン系ドイツ人の家庭に生まれた。母アンナ・レギーナ・ロイター(1697-1737)は、ニュルンベルク出身の父のもとにケーニヒスベル クで生まれた[11]。カントの父ヨハン・ゲオルク・カント(1682-1746)は、当時プロイセンの最北東部の都市メメル(現在のリトアニアのクライ ペダ)出身のドイツ人の馬具職人であった。カンツ家の名前はカントヴァイニアイ村(ドイツ語:Kantwaggen、現在のプリエクレの一部)に由来し、 クルセニキ出身であった可能性がある[12][13]。 エマヌエルの洗礼を受けたカントは、後にヘブライ語を学んでインマヌエルに改名した[14]。 カント家では、宗教的献身、謙遜、聖書の文字通りの解釈といった敬虔主義的な価値観が強調されていた[16]。幼いインマヌエルの教育は厳しく、懲罰的で 規律的であり、数学や科学よりもラテン語や宗教的な指導に重点が置かれていた[17]。 晩年、カントは厳格な規則正しい生活を送った。近所の人々は、カントが毎日散歩する時間に時計を合わせていたという。彼は結婚することはなかったが、実り ある社交生活を送っていたようで、哲学の主要著作に着手する以前から、人気のある教師であると同時に、ささやかな成功を収めた作家でもあった[18]。 |

|

Young scholar Kant showed a great aptitude for study at an early age. He first attended the Collegium Fridericianum, from which he graduated at the end of the summer of 1740. In 1740, aged 16, he enrolled at the University of Königsberg, where he would later remain for the rest of his professional life.[19] He studied the philosophy of Gottfried Leibniz and Christian Wolff under Martin Knutzen (Associate Professor of Logic and Metaphysics from 1734 until he died in 1751), a rationalist who was also familiar with developments in British philosophy and science and introduced Kant to the new mathematical physics of Isaac Newton. Knutzen dissuaded Kant from the theory of pre-established harmony, which he regarded as "the pillow for the lazy mind".[20] He also dissuaded Kant from idealism, the idea that reality is purely mental, which most philosophers in the 18th century regarded negatively. The theory of transcendental idealism that Kant later included in the Critique of Pure Reason was developed partially in opposition to traditional idealism. Kant had contacts with students, colleagues, friends and diners who frequented the local Masonic lodge.[21] His father's stroke and subsequent death in 1746 interrupted his studies. Kant left Königsberg shortly after August 1748;[22] he would return there in August 1754.[23] He became a private tutor in the towns surrounding Königsberg, but continued his scholarly research. In 1749, he published his first philosophical work, Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces (written in 1745–1747).[24] |

若き学者 カントは、幼い頃から学問に優れた才能を示していた。1740年の夏の終わりに卒業した。1740年、16歳のときにケーニヒスベルク大学に入学し、のち に生涯を過ごすことになる。マルティン・クヌッツェン(1734年から1751年に亡くなるまで論理学と形而上学の助教授)のもとで、ゴットフリート・ラ イプニッツとクリスティアン・ヴォルフの哲学を学んだ。クヌッツェンは、カントを「怠け者の心の枕」と見なした既成調和論から思いとどまらせた[20]。 彼はまた、現実は純粋に精神的なものであるという考え方である観念論からもカントを思いとどまらせた。後にカントが『純粋理性批判』に盛り込んだ超越論的 観念論の理論は、部分的には伝統的な観念論に対抗して発展したものであった。 カントは、学生、同僚、友人、地元のメーソンロッジに頻繁に通う食堂の人たちと交流があった[21]。 1746年に父親が脳卒中で倒れ、死去したため、カントの学業は中断された。1754年8月にケーニヒスベルクに戻るが[23]、ケーニヒスベルク周辺の 町で家庭教師となり、学問的研究を続けた。1749年には最初の哲学的著作『Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces』(1745-1747年執筆)を出版した[24]。 |

|

Early work Kant is best known for his work in the philosophy of ethics and metaphysics, but he made significant contributions to other disciplines. In 1754, while contemplating on a prize question by the Berlin Academy about the problem of Earth's rotation, he argued that the Moon's gravity would slow down Earth's spin and he also put forth the argument that gravity would eventually cause the Moon's tidal locking to coincide with the Earth's rotation.[b][26] The next year, he expanded this reasoning to the formation and evolution of the Solar System in his Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens.[26] In 1755, Kant received a license to lecture in the University of Königsberg and began lecturing on a variety of topics including mathematics, physics, logic, and metaphysics. In his 1756 essay on the theory of winds, Kant laid out an original insight into the Coriolis force. In 1756, Kant also published three papers on the 1755 Lisbon earthquake.[27] Kant's theory, which involved shifts in huge caverns filled with hot gases, though inaccurate, was one of the first systematic attempts to explain earthquakes in natural rather than supernatural terms. In 1757, Kant began lecturing on geography making him one of the first lecturers to explicitly teach geography as its own subject.[28][29] Geography was one of Kant's most popular lecturing topics and, in 1802, a compilation by Friedrich Theodor Rink of Kant's lecturing notes, Physical Geography, was released. After Kant became a professor in 1770, he expanded the topics of his lectures to include lectures on natural law, ethics, and anthropology, along with other topics.[28]  Kant's house in Königsberg in an 1842 painting In the Universal Natural History, Kant laid out the nebular hypothesis, in which he deduced that the Solar System had formed from a large cloud of gas, a nebula. Kant also correctly deduced that the Milky Way was a large disk of stars, which he theorized formed from a much larger spinning gas cloud. He further suggested that other distant "nebulae" might be other galaxies. These postulations opened new horizons for astronomy, for the first time extending it beyond the solar system to galactic and intergalactic realms.[30] From then on, Kant turned increasingly to philosophical issues, although he continued to write on the sciences throughout his life. In the early 1760s, Kant produced a series of important works in philosophy. The False Subtlety of the Four Syllogistic Figures, a work in logic, was published in 1762. Two more works appeared the following year: Attempt to Introduce the Concept of Negative Magnitudes into Philosophy and The Only Possible Argument in Support of a Demonstration of the Existence of God. By 1764, Kant had become a notable popular author, and wrote Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime; he was second to Moses Mendelssohn in a Berlin Academy prize competition with his Inquiry Concerning the Distinctness of the Principles of Natural Theology and Morality (often referred to as "The Prize Essay"). In 1766 Kant wrote a critical piece on Emanuel Swedenborg's Dreams of a Spirit-Seer. In 1770, Kant was appointed Full Professor of Logic and Metaphysics at the University of Königsberg. In defense of this appointment, Kant wrote his inaugural dissertation On the Form and Principles of the Sensible and the Intelligible World[c] This work saw the emergence of several central themes of his mature work, including the distinction between the faculties of intellectual thought and sensible receptivity. To miss this distinction would mean to commit the error of subreption, and, as he says in the last chapter of the dissertation, only in avoiding this error does metaphysics flourish. It is often claimed that Kant was a late developer, that he only became an important philosopher in his mid-50's after rejecting his earlier views. While it is true that Kant wrote his greatest works relatively late in life, there is a tendency to underestimate the value of his earlier works. Recent Kant scholarship has devoted more attention to these "pre-critical" writings and has recognized a degree of continuity with his mature work.[31] |

初期の著作 カントは倫理哲学と形而上学における業績で最もよく知られているが、他の学問分野にも多大な貢献をした。1754年、ベルリン・アカデミーの懸賞問題で地 球の自転の問題について考えていたとき、彼は月の重力が地球の自転を減速させると主張し、また、重力がやがて月の潮汐ロッキングを地球の自転と一致させる という議論を展開した。 [1755年、カントはケーニヒスベルク大学で講義をする許可を得て、数学、物理学、論理学、形而上学などさまざまなテーマで講義を始めた。1756年、 風の理論に関するエッセイで、カントはコリオリの力に関する独自の洞察を示した。 1756年、カントは1755年のリスボン地震に関する3つの論文も発表した[27]。カントの理論は、高温のガスで満たされた巨大な洞窟の中でのシフト を含むものであったが、不正確であったものの、地震を超自然的な用語ではなく、自然的な用語で説明する最初の体系的な試みの一つであった。1757年、カ ントは地理学の講義を開始し、地理学をそれ自身の科目として明確に教えた最初の講師の一人となった[28][29]。地理学はカントにとって最も人気のあ る講義テーマの一つであり、1802年にはフリードリヒ・テオドール・リンクがカントの講義ノートをまとめた『物理地理学』が出版された。1770年にカ ントが教授になってからは、講義のテーマを自然法、倫理学、人間学などに広げた[28]。  1842年に描かれたケーニヒスベルクのカントの家 カントは『普遍博物誌』の中で、太陽系が大きなガスの雲、星雲から形成されたと推論する星雲仮説を打ち立てた。カントはまた、天の川銀河が星の大きな円盤 であることを正しく推論し、その円盤はもっと大きな回転するガス雲から形成されたと説いた。さらに彼は、他の遠くの「星雲」が他の銀河である可能性を示唆 した。これらの仮説は天文学に新たな地平を開き、初めて天文学を太陽系から銀河系や銀河間領域にまで拡張した[30]。 それ以降、カントは生涯を通じて科学に関する著作を書き続けたものの、ますます哲学的な問題に傾倒していった。1760年代初頭、カントは哲学における一 連の重要な著作を生み出した。1762年、論理学の著作『4つの論理図形の偽りの微妙さ』が出版された。翌年にはさらに2つの著作が発表された: 哲学に負の大きさの概念を導入する試み』と『神の存在の実証を支持する唯一可能な論証』である。1764年までにカントは著名な人気作家となり、『美と崇 高の感覚に関する観察』を著し、ベルリン・アカデミーの懸賞論文でモーゼ・メンデルスゾーンに次いで2位になった。1766年、カントはエマニュエル・ス ウェーデンボルグの『霊能者の夢』について批評を書いた。 1770年、カントはケーニヒスベルク大学の論理学および形而上学の正教授に任命された。この就任を擁護するために、カントは『感覚的世界と知性的世界の 形式と原理について』という学位論文を執筆した[c]。この論文には、知的思考能力と感覚的受容能力の区別など、カントの成熟した研究の中心的なテーマが いくつか現れている。この区別を見落とすことは、副読本の誤りを犯すことを意味し、論文の最終章で彼が言うように、この誤りを回避してこそ形而上学は花開 くのである。 カントは後発の哲学者であり、それまでの見解を否定して50代半ばになって初めて重要な哲学者になったと主張されることが多い。カントが比較的晩年に偉大 な著作を残したことは事実だが、それ以前の著作の価値を過小評価する傾向がある。近年のカント研究は、これらの「批判以前」の著作により多くの注意を払 い、彼の成熟した著作との連続性をある程度認めている[31]。 |

|

Publication of The Critique of Pure Reason Main article: Critique of Pure Reason At age 46, Kant was an established scholar and an increasingly influential philosopher, and much was expected of him. In correspondence with his ex-student and friend Markus Herz, Kant admitted that, in the inaugural dissertation, he had failed to account for the relation between our sensible and intellectual faculties.[32] He needed to explain how we combine what is known as sensory knowledge with the other type of knowledge—that is, reasoned knowledge—these two being related, but having very different processes.  Portrait of philosopher David Hume Kant also credited David Hume with awakening him from a "dogmatic slumber" in which he had unquestioningly accepted the tenets of both religion and natural philosophy.[33][34] Hume, in his 1739 Treatise on Human Nature, had argued that we only know the mind through a subjective, essentially illusory series of perceptions. Ideas such as causality, morality, and objects are not evident in experience, so their reality may be questioned. Kant felt that reason could remove this skepticism, and he set himself to solving these problems. Although fond of company and conversation with others, Kant isolated himself, and resisted friends' attempts to bring him out of his isolation.[d] When Kant emerged from his silence in 1781, the result was the Critique of Pure Reason. Kant countered Hume's empiricism by claiming that some knowledge exists inherently in the mind, independent of experience.[33] He drew a parallel to the Copernican revolution in his proposal that worldly objects can be intuited a priori, and that intuition is consequently distinct from objective reality. He acquiesced to Hume somewhat by defining causality as a "regular, constant sequence of events in time, and nothing more".[36] Although now uniformly recognized as one of the greatest works in the history of philosophy, this Critique disappointed Kant's readers upon its initial publication.[37] The book was long, over 800 pages in the original German edition, and written in a convoluted style. Kant was quite upset with its reception.[38] His former student, Johann Gottfried Herder criticized it for placing reason as an entity worthy of criticism instead of considering the process of reasoning within the context of language and one's entire personality.[39] Similar to Christian Garve and Johann Georg Heinrich Feder, he rejected Kant's position that space and time possessed a form that could be analyzed. Additionally, Garve and Feder also faulted Kant's Critique for not explaining differences in perception of sensations.[40] Its density made it, as Herder said in a letter to Johann Georg Hamann, a "tough nut to crack", obscured by "all this heavy gossamer".[41] Its reception stood in stark contrast to the praise Kant had received for earlier works, such as his Prize Essay and shorter works that preceded the first Critique. Recognizing the need to clarify the original treatise, Kant wrote the Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics in 1783 as a summary of its main views. Shortly thereafter, Kant's friend Johann Friedrich Schultz (1739–1805), a professor of mathematics, published Explanations of Professor Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (Königsberg, 1784), which was a brief but very accurate commentary on Kant's Critique of Pure Reason.[42]  Engraving of Immanuel Kant Kant's reputation gradually rose through the latter portion of the 1780s, sparked by a series of important works: the 1784 essay, "Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?"; 1785's Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (his first work on moral philosophy); and, from 1786, Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science. But Kant's fame ultimately arrived from an unexpected source. In 1786, Karl Leonhard Reinhold published a series of public letters on Kantian philosophy.[43] In these letters, Reinhold framed Kant's philosophy as a response to the central intellectual controversy of the era: the pantheism controversy. Friedrich Jacobi had accused the recently deceased Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (a distinguished dramatist and philosophical essayist) of Spinozism. Such a charge, tantamount to atheism, was vigorously denied by Lessing's friend Moses Mendelssohn, leading to a bitter public dispute among partisans. The controversy gradually escalated into a debate about the values of the Enlightenment and the value of reason. Reinhold maintained in his letters that Kant's Critique of Pure Reason could settle this dispute by defending the authority and bounds of reason. Reinhold's letters were widely read and made Kant the most famous philosopher of his era. |

『純粋理性批判』の出版 主な記事 純粋理性批判 46歳の時、カントは確立された学者であり、ますます影響力のある哲学者となっていた。元教え子であり友人でもあったマルクス・ヘルツとの手紙の中で、カ ントは学位論文の中で、人間の感覚的能力と知的能力との関係を説明できていなかったことを認めた[32]。  哲学者デイヴィッド・ヒュームの肖像 カントはまた、宗教と自然哲学の両方の信条を疑うことなく受け入れていた「独断的な眠り」から目覚めさせたとして、デイヴィッド・ヒュームの功績を認めて いる[33][34]。ヒュームは1739年に発表した『人間本性論』の中で、主観的で本質的に幻想的な一連の知覚を通してしか心を知ることはできないと 主張していた。因果性、道徳、対象といった観念は経験において明らかではないため、その実在性が疑われることがある。カントは理性がこの懐疑を取り除くこ とができると考え、これらの問題の解決に乗り出した。1781年にカントが沈黙から覚めると、その結果生まれたのが『純粋理性批判』であった。カントは ヒュームの経験主義に対抗して、ある知識は経験とは無関係に心の中に本質的に存在すると主張した[33]。彼はコペルニクス的革命と並行して、この世の物 体は先験的に直観することができ、直観は結果的に客観的現実とは異なるという提案をした。彼は因果性を「時間における規則的で一定の出来事の連続であり、 それ以上のものではない」と定義することによって、ヒュームにいくらか同意した[36]。 現在では哲学史上最高の著作の一つとして一様に認められているが、この『批判』は出版当初はカントの読者を失望させた[37]。この本は長く、原著のドイ ツ語版では800ページを超え、複雑な文体で書かれていた。彼の元教え子であるヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダーは、言語と全人格の文脈における推論のプ ロセスを考慮する代わりに、批判に値する実体として理性を置いていると批判した[39]。クリスティアン・ガルヴェやヨハン・ゲオルク・ハインリッヒ・ フェーダーと同様に、彼は空間と時間が分析可能な形式を持っているというカントの立場を否定した。さらに、ガーヴェとフェーダーは、カントの『批評』が感 覚の知覚の差異を説明していないことを非難した[40]。その密度は、ヘルダーがヨハン・ゲオルク・ハマンに宛てた手紙の中で述べたように、「この重いゴ ザすべて」によって不明瞭にされ、「割るのが難しい難物」であった[41]。原論を明確にする必要性を認識したカントは、1783年にその主要な見解の要 約として『未来の形而上学へのプロレゴメナ』を書いた。その直後、カントの友人で数学の教授であったヨハン・フリードリヒ・シュルツ(Johann Friedrich Schultz, 1739-1805)は、『カント教授の純粋理性批判の説明』(Königsberg, 1784)を出版した。  イマヌエル・カントの版画像 カントの名声は1780年代後半にかけて徐々に高まっていった: 1784年のエッセイ『啓蒙とは何か』、1785年の『道徳形而上学の基礎づけ』(道徳哲学に関する最初の著作)、1786年の『自然科学の形而上学的基 礎づけ』などである。しかし、カントの名声は、最終的には意外なところからもたらされた。1786年、カール・レオンハルト・ラインホルトは、カント哲学 に関する一連の公開書簡を発表した[43]。これらの書簡の中で、ラインホルトはカント哲学を、当時の中心的な知的論争であった汎神論論争への応答として 位置づけた。フリードリヒ・ヤコービは、最近亡くなったゴットホルト・エフライム・レッシング(著名な劇作家であり哲学エッセイスト)をスピノザ主義で非 難した。無神論に等しいこの非難を、レッシングの友人モーゼス・メンデルスゾーンは激しく否定した。論争は次第に啓蒙主義の価値と理性の価値についての論 争へとエスカレートしていった。 ラインホルトは手紙の中で、カントの『純粋理性批判』が理性の権威と限界を擁護することによってこの論争に決着をつけることができると主張した。ラインホ ルトの手紙は広く読まれ、カントは同時代で最も有名な哲学者となった。 |

|

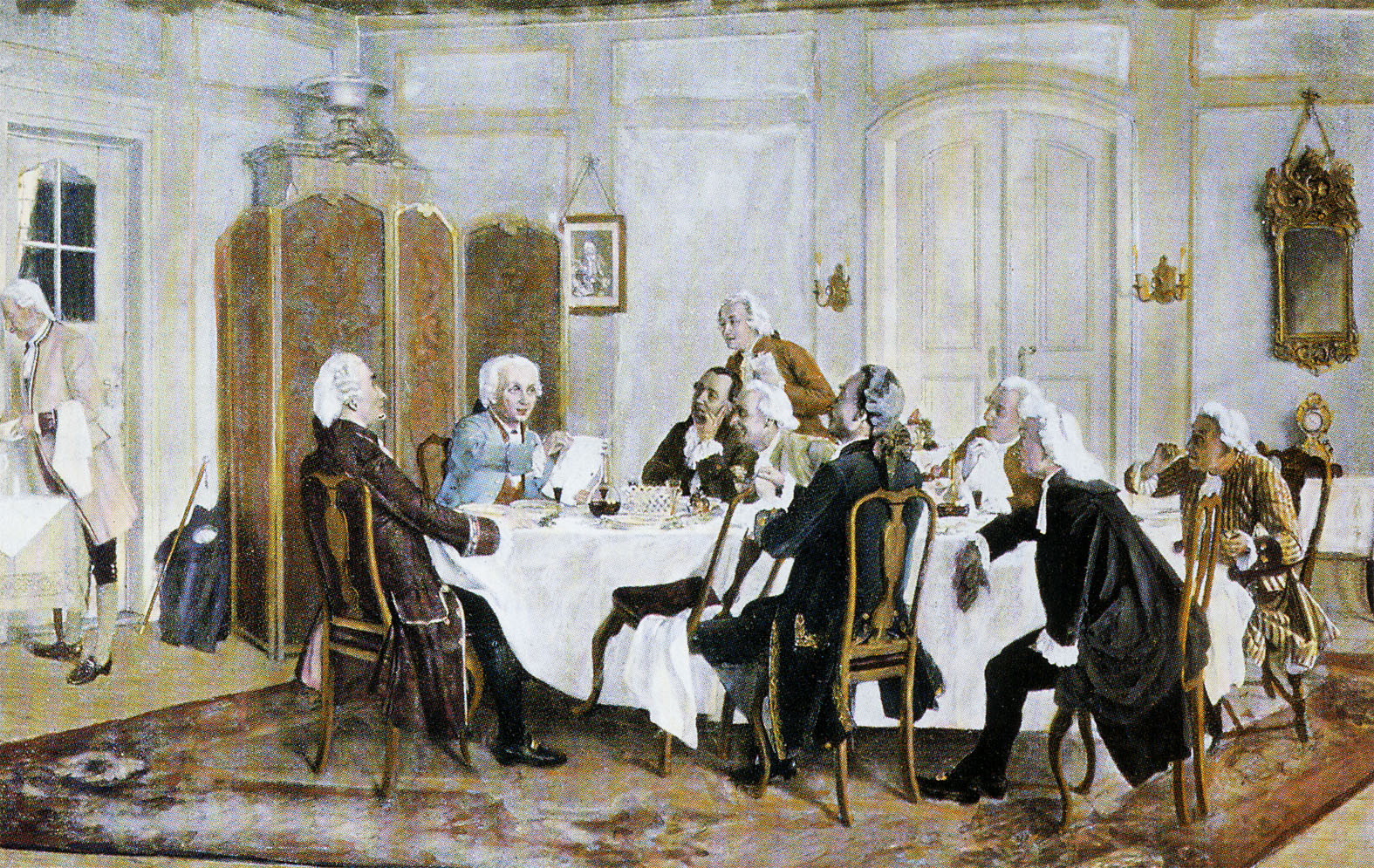

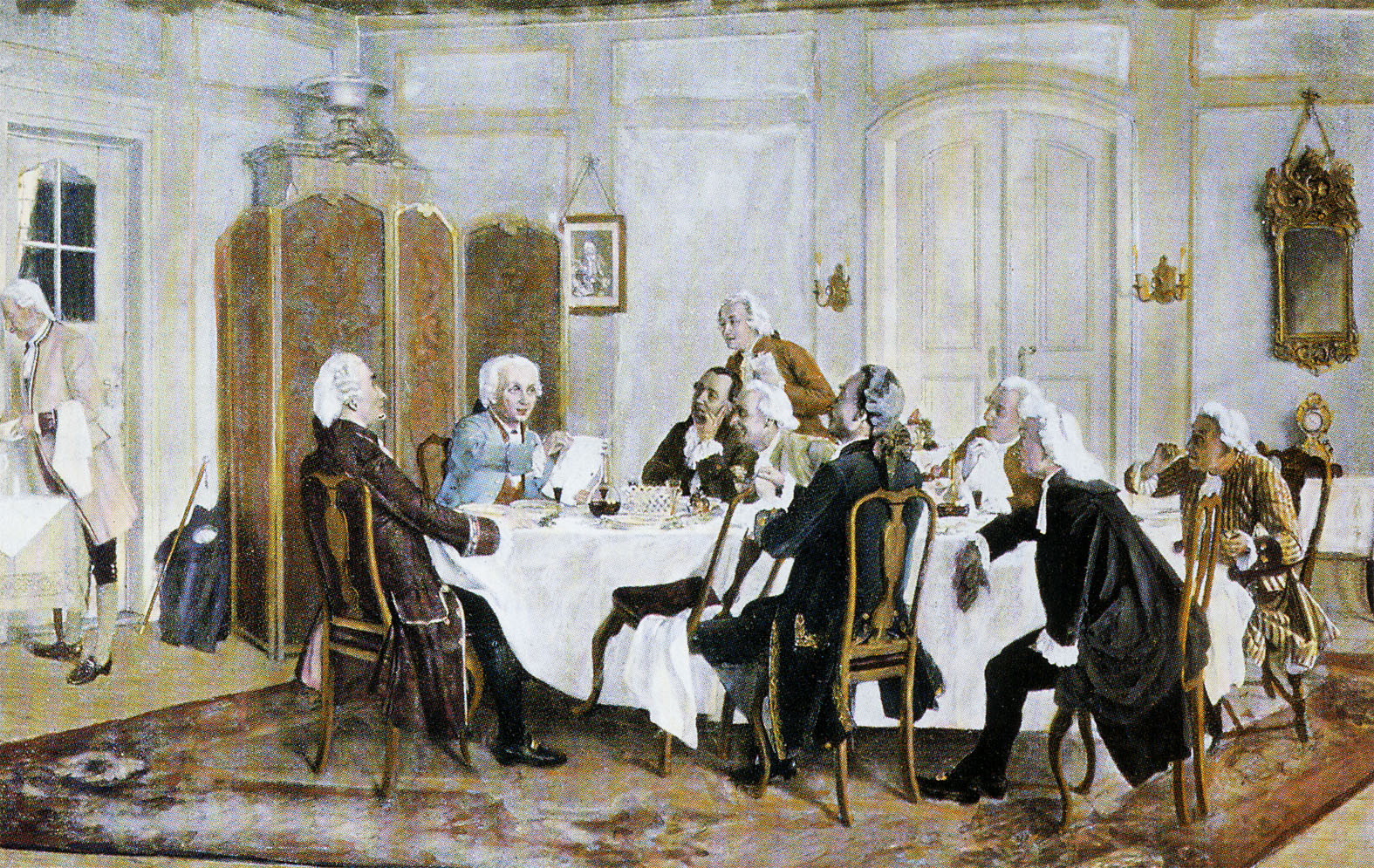

Later work Kant published a second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason in 1787, heavily revising the first parts of the book. Most of his subsequent work focused on other areas of philosophy. He continued to develop his moral philosophy, notably in 1788's Critique of Practical Reason (known as the second Critique), and 1797's Metaphysics of Morals. The 1790 Critique of the Power of Judgment (the third Critique) applied the Kantian system to aesthetics and teleology. In 1792, Kant's attempt to publish the Second of the four Pieces of Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason,[44] in the journal Berlinische Monatsschrift, met with opposition from the King's censorship commission, which had been established that same year in the context of the French Revolution.[45] Kant then arranged to have all four pieces published as a book, routing it through the philosophy department at the University of Jena to avoid the need for theological censorship.[45] This insubordination earned him a now-famous reprimand from the King.[45] When he nevertheless published a second edition in 1794, the censor was so irate that he arranged for a royal order that required Kant never to publish or even speak publicly about religion.[45] Kant then published his response to the King's reprimand and explained himself in the preface of The Conflict of the Faculties.[45]  Kant with friends, including Christian Jakob Kraus, Johann Georg Hamann, Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel and Karl Gottfried Hagen He also wrote a number of semi-popular essays on history, religion, politics, and other topics. These works were well received by Kant's contemporaries and confirmed his preeminent status in eighteenth-century philosophy. There were several journals devoted solely to defending and criticizing Kantian philosophy. Despite his success, philosophical trends were moving in another direction. Many of Kant's most important disciples and followers (including Reinhold, Beck, and Fichte) transformed the Kantian position. The progressive stages of revision of Kant's teachings marked the emergence of German idealism. Kant opposed these developments and publicly denounced Fichte in an open letter in 1799.[46] It was one of his final acts expounding a stance on philosophical questions. In 1800, a student of Kant named Gottlob Benjamin Jäsche (1762–1842) published a manual of logic for teachers called Logik, which he had prepared at Kant's request. Jäsche prepared the Logik using a copy of a textbook in logic by Georg Friedrich Meier entitled Excerpt from the Doctrine of Reason, in which Kant had written copious notes and annotations. The Logik has been considered of fundamental importance to Kant's philosophy, and the understanding of it. The great 19th-century logician Charles Sanders Peirce remarked, in an incomplete review of Thomas Kingsmill Abbott's English translation of the introduction to Logik, that "Kant's whole philosophy turns upon his logic."[47] Also, Robert Schirokauer Hartman and Wolfgang Schwarz wrote in the translators' introduction to their English translation of the Logik, "Its importance lies not only in its significance for the Critique of Pure Reason, the second part of which is a restatement of fundamental tenets of the Logic, but in its position within the whole of Kant's work."[48] |

その後の仕事 カントは1787年に『純粋理性批判』の第2版を出版し、最初の部分を大幅に改訂した。その後の研究の大半は、哲学の他の分野に焦点を当てたものであっ た。特に1788年の『実践理性批判』(第二批判として知られる)や1797年の『形而上学』では、道徳哲学を発展させ続けた。1790年の『判断力批 判』(第三批判)は、カント体系を美学と目的論に応用したものである。 1792年、カントが雑誌『Berlinische Monatsschrift』に『裸の理性の範囲内における宗教の4篇』の第2篇を発表しようとしたが[44]、同年フランス革命の文脈で設置された国王 の検閲委員会の反対に遭った[45]。カントはその後、神学的検閲の必要性を避けるためにイエナ大学の哲学科を通じて4篇すべてを書籍として出版するよう 手配した。 [この反抗的な態度は、国王から有名な叱責を受けた[45]。それでも1794年に第2版を出版すると、検閲官は激怒し、カントが宗教について出版した り、公の場で話したりすることを禁じる勅令を手配した[45]。 カントはその後、国王の叱責に対する返答を発表し、『学問の対立』の序文で自らを釈明した[45]。  クリスチャン・ヤコブ・クラウス、ヨハン・ゲオルク・ハマン、テオドール・ゴットリープ・フォン・ヒッペル、カール・ゴットフリート・ハーゲンら友人たち と。 彼はまた、歴史、宗教、政治、その他のトピックについて、多くの準人気のエッセイを書いた。これらの著作はカントと同時代の哲学者たちに高く評価され、 18世紀哲学におけるカントの傑出した地位を確かなものにした。カント哲学の擁護と批判だけに専念した雑誌もいくつかあった。彼の成功にもかかわらず、哲 学の潮流は別の方向に進んでいた。カントの最も重要な弟子や追随者(ラインホルト、ベック、フィヒテを含む)の多くは、カントの立場を変革した。カントの 教えが段階的に修正され、ドイツ観念論が出現した。カントはこのような動きに反対し、1799年に公開書簡でフィヒテを公然と非難した[46]。これは哲 学的な問題に対する姿勢を表明した彼の最後の行為のひとつであった。 1800年、カントの弟子であったゴットロープ・ベンジャミン・イェーシェ(1762-1842)は、カントの依頼で作成した『論理学』という教師向けの 論理学のマニュアルを出版した。イェーシェは、ゲオルク・フリードリッヒ・マイヤーによる論理学の教科書『理性の教義からの抜粋』のコピーを用いて『ロ ジック』を作成したが、そこにはカントが大量の注釈や注釈を書き込んでいた。この『論理学』は、カントの哲学とその理解にとって根本的に重要であると考え られてきた。19世紀の偉大な論理学者チャールズ・サンダース・パイアースは、トーマス・キングスミル・アボットによる『論理学』序論の英訳の不完全な批 評の中で、「カントの哲学全体は彼の論理学の上に成り立っている」と述べている[47]。 また、ロバート・シロカウアー・ハルトマンとヴォルフガング・シュヴァルツは『論理学』の英訳版の訳者序文で「その重要性は、『純粋理性批判』(その第二 部は『論理学』の基本的な教義の再述である)にとって重要であるだけでなく、カントの著作全体におけるその位置づけにある」と書いている[48]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immanuel_Kant |

|

| Death and burial Kant's health, long poor, worsened. He died at Königsberg on 12 February 1804, uttering "Es ist gut" (It is good) before expiring.[49] His unfinished final work was published as Opus Postumum. Kant always cut a curious figure in his lifetime for his modest, rigorously scheduled habits, which have been referred to as clocklike. However, Heinrich Heine noted the magnitude of "his destructive, world-crushing thoughts" and considered him a sort of philosophical "executioner", comparing him to Robespierre with the observation that both men "represented in the highest the type of provincial bourgeois. Nature had destined them to weigh coffee and sugar, but Fate determined that they should weigh other things and placed on the scales of the one a king, on the scales of the other a god."[50] When his body was transferred to a new burial spot, his skull was measured during the exhumation and found to be larger than the average German male's with a "high and broad" forehead.[51] His forehead has been an object of interest ever since it became well known through his portraits: "In Döbler's portrait and in Kiefer's faithful if expressionistic reproduction of it—as well as in many of the other late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century portraits of Kant—the forehead is remarkably large and decidedly retreating."[52]  Kant's tomb in Kaliningrad, Russia Kant's mausoleum adjoins the northeast corner of Königsberg Cathedral in Kaliningrad, Russia. The mausoleum was constructed by the architect Friedrich Lahrs and was finished in 1924, in time for the bicentenary of Kant's birth. Originally, Kant was buried inside the cathedral, but in 1880 his remains were moved to a neo-Gothic chapel adjoining the northeast corner of the cathedral. Over the years, the chapel became dilapidated and was demolished to make way for the mausoleum, which was built on the same location. The tomb and its mausoleum are among the few artifacts of German times preserved by the Soviets after they captured the city.[53] Today, many newlyweds bring flowers to the mausoleum. Artifacts previously owned by Kant, known as Kantiana, were included in the Königsberg City Museum. However, the museum was destroyed during World War II. A replica of the statue of Kant that in German times stood in front of the main University of Königsberg building was donated by a German entity in the early 1990s and placed in the same grounds. After the expulsion of Königsberg's German population at the end of World War II, the University of Königsberg where Kant taught was replaced by the Russian-language Kaliningrad State University, which appropriated the campus and surviving buildings. In 2005, the university was renamed Immanuel Kant State University of Russia. The name change was announced at a ceremony attended by President Vladimir Putin of Russia and Chancellor Gerhard Schröder of Germany, and the university formed a Kant Society, dedicated to the study of Kantianism. The university was again renamed in the 2010s, to Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University.[54] |

死と埋葬 カントの健康状態は長い間思わしくなかった。1804年2月12日、ケーニヒスベルクで死去。息を引き取る前に「Es ist gut(それは良いことだ)」と口にした[49]。未完の遺作は『Opus Postumum』として出版された。カントは生前、その控えめで、厳格に予定調和を重んじる習慣のために、常に不思議な人物であった。しかし、ハイン リッヒ・ハイネは、「彼の破壊的で、世界を打ち砕くような思想」の大きさを指摘し、彼を一種の哲学的「処刑人」とみなし、ロベスピエールと比較して、両者 とも「地方ブルジョワの最高のタイプを代表している。自然は彼らにコーヒーと砂糖を量るよう運命づけたが、運命は彼らが他のものを量るよう定め、一方の天 秤には王を、他方の天秤には神を載せた」[50]。 彼の遺体が新しい埋葬地に移されたとき、発掘の際に頭蓋骨が測定され、平均的なドイツ人男性よりも大きく、「高くて広い」額であることが判明した [51]: 「デーブラーの肖像画とキーファーの忠実な、しかし表現主義的な複製において、また18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけてのカントの肖像画の多くにおい て、額は驚くほど大きく、明らかに後退している」[52]。  ロシアのカリーニングラードにあるカントの墓 ロシアのカリーニングラードにあるケーニヒスベルク大聖堂の北東角に隣接するカントの霊廟。この霊廟は建築家フリードリヒ・ラーフスによって建設され、カ ントの生誕200年に合わせて1924年に完成した。当初、カントは大聖堂内に埋葬されていたが、1880年に遺骸は大聖堂の北東角に隣接するネオ・ゴ シック様式の礼拝堂に移された。長い年月の間に礼拝堂は老朽化し、同じ場所に建てられた霊廟のために取り壊された。 墓と霊廟は、ソビエトがこの街を占領した後、ドイツ時代の数少ない遺物として保存されている。カンティアーナとして知られるカントが以前所有していた工芸 品は、ケーニヒスベルク市立博物館に含まれていた。しかし、博物館は第二次世界大戦中に破壊された。ドイツ時代にケーニヒスベルク大学本館の前にあったカ ント像のレプリカは、1990年代初頭にドイツの団体によって寄贈され、同じ敷地内に置かれた。 第二次世界大戦末期にケーニヒスベルクのドイツ系住民が追放された後、カントが教鞭を執っていたケーニヒスベルク大学はロシア語のカリーニングラード国立 大学に取って代わられ、同大学がキャンパスと現存する建物を譲り受けた。2005年、同大学はロシア国立イマヌエル・カント大学と改称された。改名は、ロ シアのプーチン大統領とドイツのゲルハルト・シュレーダー首相が出席した式典で発表され、大学にはカント主義の研究を目的とするカント協会が設立された。 大学は2010年代に再び改名され、イマヌエル・カント・バルト連邦大学となった[54]。 |

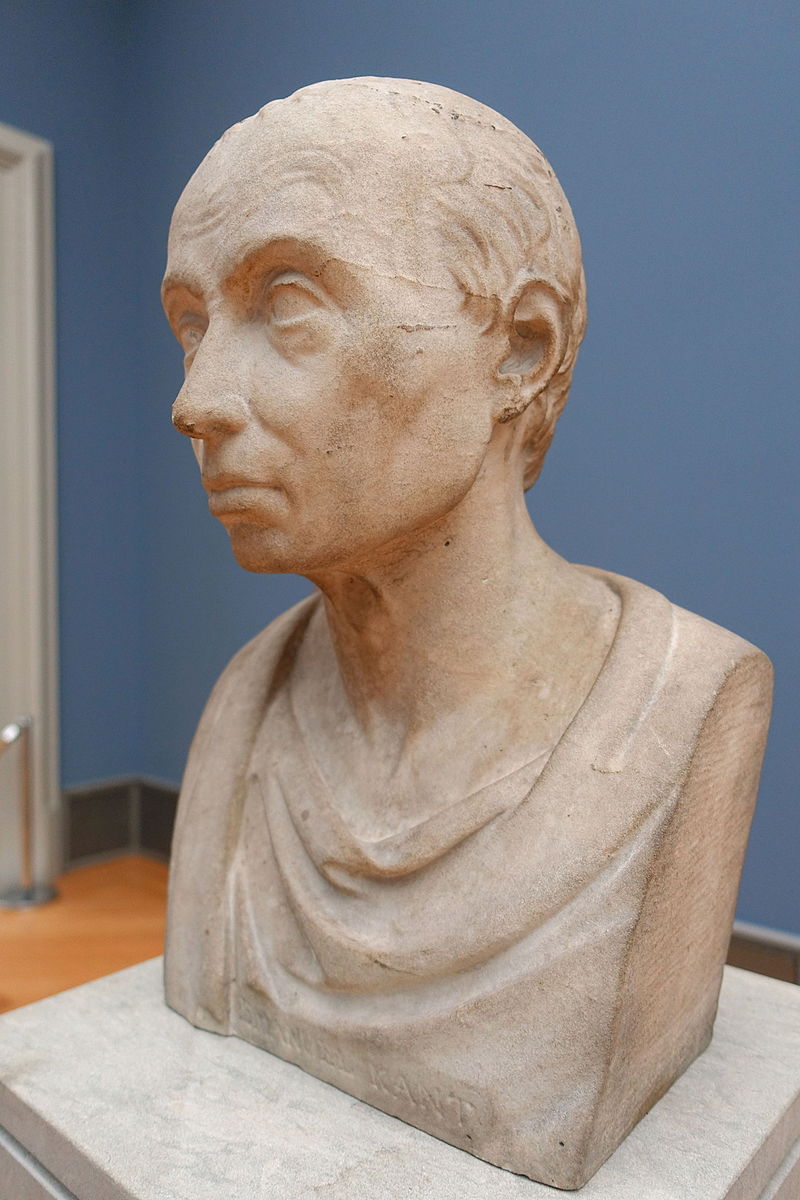

Bust of Immanuel Kant by Emanuel Bardou, 1798 |

カントの哲学は「カント入門」に移転しています |

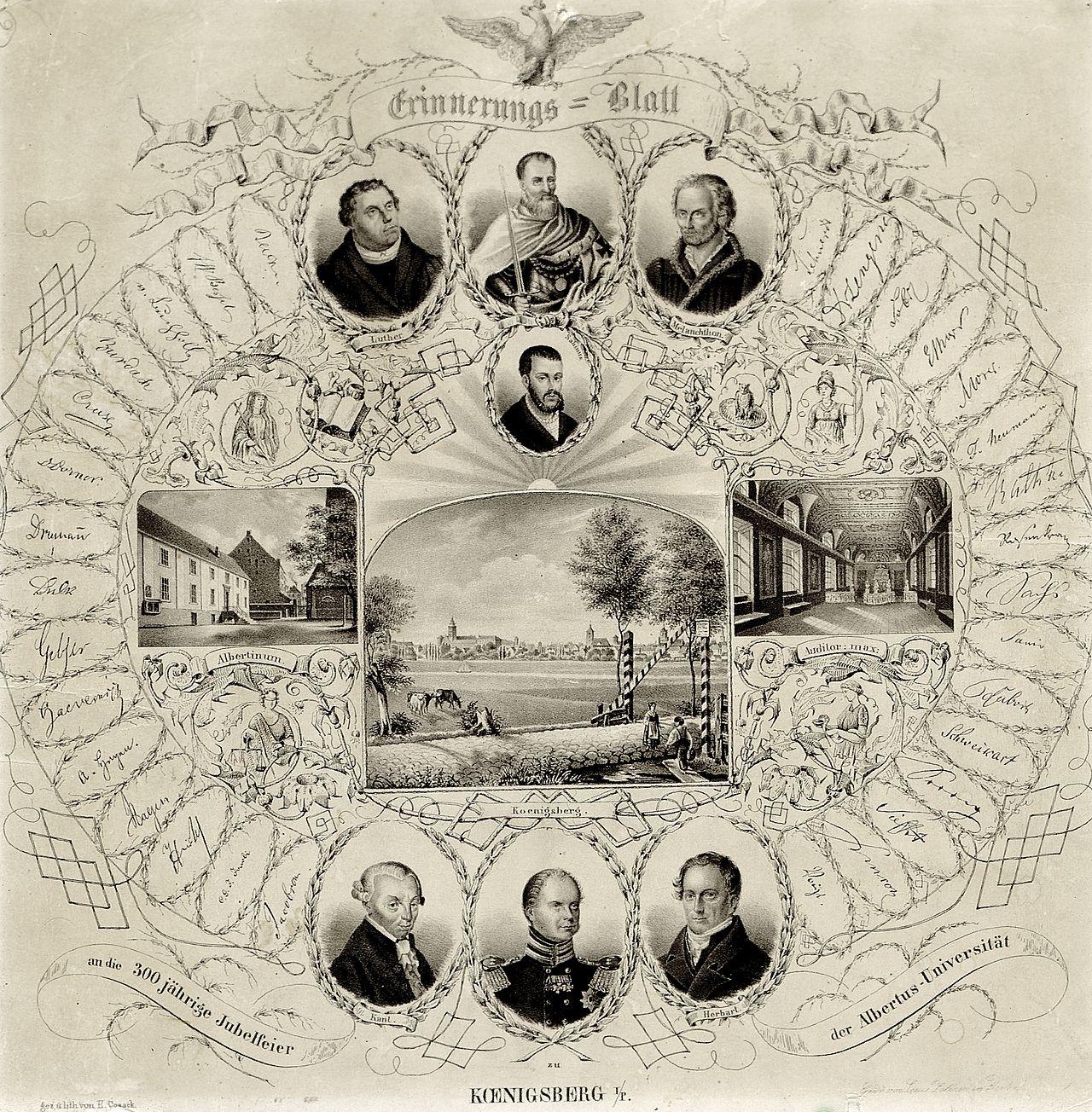

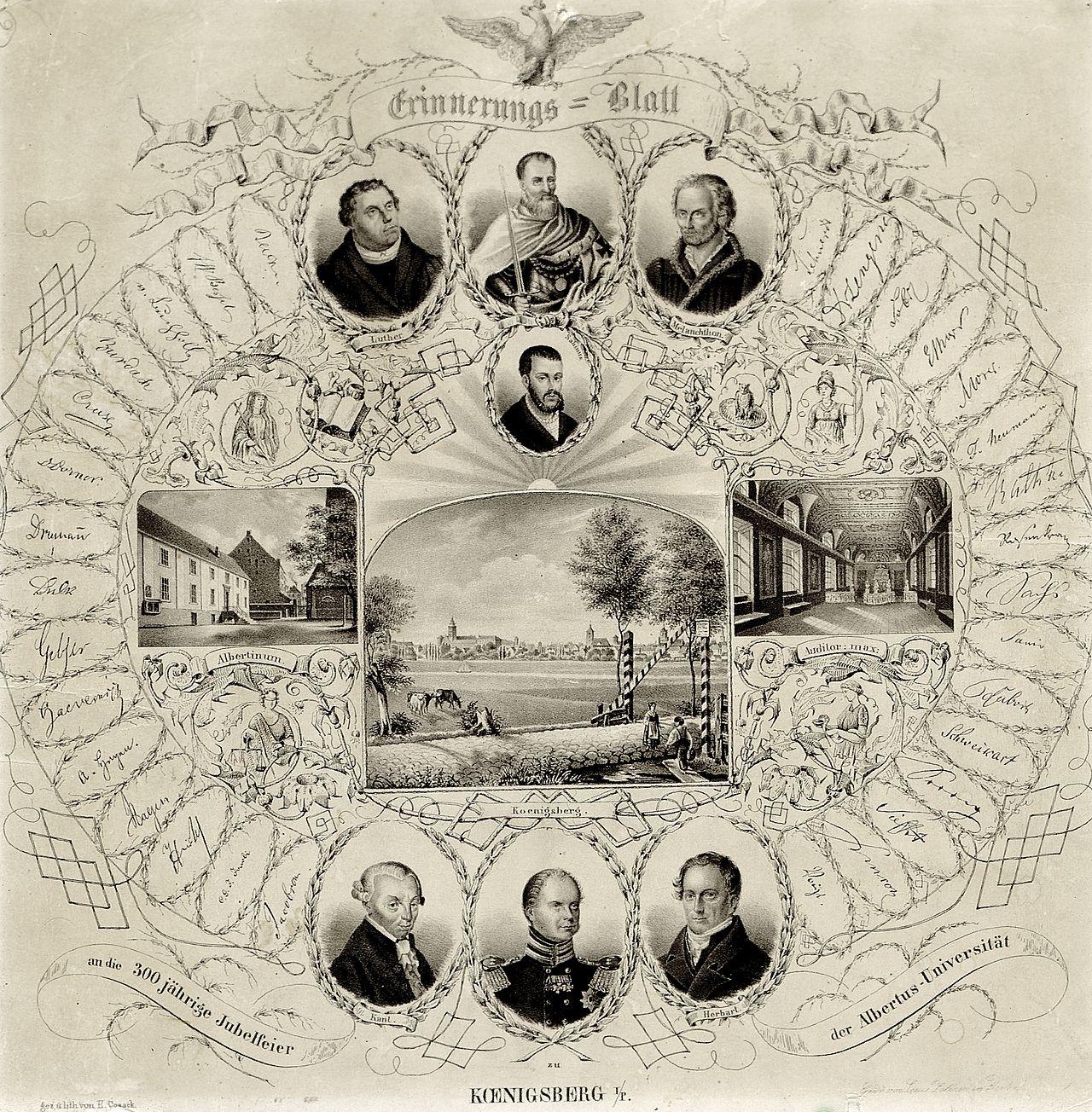

| Influence and legacy This article may contain unverified or indiscriminate information in embedded lists. Please help clean up the list. (April 2023)  Poster celebrating the 300 years of the University of Königsberg, 1844. Among others, Kant and Herbart are honored. Kant's influence on Western thought has been profound.[i] Although the basic tenets of Kant's transcendental idealism (i.e., that space and time are a priori forms of human perception rather than real properties and the claim that formal logic and transcendental logic coincide) have been claimed to be falsified by modern science and logic,[207][208][209] and no longer set the intellectual agenda of contemporary philosophers, Kant is credited with having innovated the way philosophical inquiry has been carried on at least up to the early nineteenth century. This shift consisted of several closely related innovations that, although highly contentious in themselves, have become important in subsequent philosophy and in the social sciences broadly construed: The human subject seen as the center of inquiry into human knowledge, such that it is impossible to philosophize about things as they exist independently of human perception or of how they are "for us";[210] the notion that is possible to discover and systematically explore the inherent limits of the human ability to know entirely a priori; the notion of the "categorical imperative", an assertion that people are naturally endowed with the ability and obligation toward right reason and acting. Perhaps his most famous quote is drawn from the Critique of Practical Reason: "Two things fill my mind with ever new and increasing admiration and reverence...: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me";[211] the concept of "conditions of possibility", as in his notion of "the conditions of possible experience"; that is, that things, knowledge, and forms of consciousness rest on prior conditions that make them possible, so that, to understand or to know them, several conditions must be understood; the claim that objective experience is actively constituted or constructed by the functioning of the human mind; the concept of moral autonomy as central to humanity; and the assertion of the principle that human beings should be treated as ends rather than as mere means. Kant's ideas have been incorporated into a variety of schools of thought. These include German idealism,[212] Marxism, positivism, phenomenology, existentialism, critical theory, linguistic philosophy, structuralism, post-structuralism, and deconstruction.[citation needed] Historical influence This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) During his own life, much critical attention was paid to Kant's thought. He influenced Reinhold, Fichte, Schelling, Hegel, and Novalis during the 1780s and 1790s. Statue of Immanuel Kant in Kaliningrad (Königsberg), Russia. Replica by Harald Haacke [de] of the original by Christian Daniel Rauch lost in 1945. Samuel Taylor Coleridge was greatly influenced by Kant and helped to spread awareness of him, and of German Idealism generally, in the UK and the US. In his Biographia Literaria (1817), he credits Kant's ideas in coming to believe that the mind is not a passive, but an active agent in the apprehension of reality. Hegel was one of Kant's first major critics. In Hegel's view the entire project of setting a "transcendental subject" (i.e., human consciousness) apart from the living individual as well as from nature, history, and society was fundamentally flawed,[213] although parts of that very project could be put to good use in a new direction. Similar concerns motivated Hegel's criticisms of Kant's concept of moral autonomy, to which Hegel opposed an ethic focused on the "ethical life" of the community.[j] In a sense, Hegel's notion of "ethical life" is meant to subsume, rather than replace, Kantian ethics. And Hegel can be seen as trying to defend Kant's idea of freedom as going beyond finite "desires", by means of reason. Thus, in contrast to later critics like Nietzsche or Russell, Hegel shares some of Kant's concerns.[k] Kant's thinking on religion was used in Britain by philosophers such as Thomas Carlyle[214] to challenge the nineteenth-century decline in religious faith. British Catholic writers, notably G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, followed this approach.[citation needed] Criticisms of Kant were common in the realist views of the new positivism at that time. Arthur Schopenhauer was strongly influenced by Kant's transcendental idealism. He, like G. E. Schulze, Jacobi, and Fichte before him, was critical of Kant's theory of the thing-in-itself. Things-in-themselves, they argued, are neither the cause of what we observe, nor are they completely beyond our access. Ever since the Critique of Pure Reason, philosophers have been critical of Kant's theory of the thing-in-itself. Many have argued that, if such a thing exists beyond experience, then one cannot posit that it affects us causally, since that would entail stretching the category "causality" beyond the realm of experience.[l] With the success and wide influence of Hegel's writings, Kant's own influence began to wane, but a re-examination of his ideas began in Germany in 1865 with the publication of Kant und die Epigonen by Otto Liebmann, whose motto was "Back to Kant". There proceeded an important revival of Kant's theoretical philosophy, known as Neo-Kantianism. Weimar Republic stamp honoring Kant, 1926 Kant's notion of "critique" has been more broadly influential. The early German Romantics, especially Friedrich Schlegel in his "Athenaeum Fragments", used Kant's reflexive conception of criticism in their Romantic theory of poetry.[215] Also in aesthetics, Clement Greenberg, in his classic essay "Modernist Painting", uses Kantian criticism, what Greenberg refers to as "immanent criticism", to justify the aims of abstract painting, a movement Greenberg saw as aware of the key limitation—flatness—that makes up the medium of painting.[216] French philosopher Michel Foucault was also greatly influenced by Kant's notion of "critique" and wrote several pieces on Kant for a re-thinking of the Enlightenment as a form of "critical thought". He went so far as to classify his own philosophy as a "critical history of modernity, rooted in Kant".[217] Kant believed that mathematical truths were forms of synthetic a priori knowledge, which means they are necessary and universal, yet known through the a priori intuition of space and time, as transcendental preconditions of experience.[218] Kant's often brief remarks about mathematics influenced the mathematical school known as intuitionism, a movement in philosophy of mathematics opposed to Hilbert's formalism, and Frege and Bertrand Russell's logicism.[m] Influence on modern thinkers West German postage stamp, 1974, commemorating the 250th anniversary of Kant's birth With his Perpetual Peace, Kant is considered to have foreshadowed many of the ideas that have come to form the democratic peace theory, one of the main controversies in political science.[219] More concretely, Constructivist theorist Alexander Wendt proposed that the anarchy of the international system could evolve from the 'brutish' Hobbesian anarchy understood by Realist theorists, through Lockean anarchy, and ultimately a Kantian anarchy in which states would see their self-interests as inextricably linked to the well being of other states, thus transforming international politics into a far more peaceful form.[220] Prominent recent Kantians include the British philosophers P. F. Strawson,[n] Onora O'Neill,[221] and Quassim Cassam,[222] and the American philosophers Wilfrid Sellars[223] and Christine Korsgaard.[o] Due to the influence of Strawson and Sellars, among others, there has been a renewed interest in Kant's view of the mind. Central to many debates in philosophy of psychology and cognitive science is Kant's conception of the unity of consciousness.[p] Jürgen Habermas and John Rawls are two significant political and moral philosophers whose work is strongly influenced by Kant's moral philosophy.[q] They have argued against relativism,[224] supporting the Kantian view that universality is essential to any viable moral philosophy. Mou Zongsan's study of Kant has been cited as a highly crucial part in the development of Mou's personal philosophy, namely New Confucianism. Widely regarded as the most influential Kant scholar in China, Mou's rigorous critique of Kant's philosophy—having translated all three of Kant's critiques—served as an ardent attempt to reconcile Chinese and Western philosophy whilst increasing pressure to westernize in China.[225][226] East German commemorative coin honoring Kant, 1974 Kant's influence has also extended to the social, behavioral, and physical sciences—as in the sociology of Max Weber, the psychology of Jean Piaget and Carl Gustav Jung,[227][228] and the linguistics of Noam Chomsky. Kant's work on mathematics and synthetic a priori knowledge is also cited by theoretical physicist Albert Einstein as an early influence on his intellectual development, though one which he later criticized and rejected.[229] In recent years, there has also been renewed interest in Kant's theory of mind from the point of view of formal logic and computer science.[230] Because of the thoroughness of Kant's paradigm shift, his influence extends well beyond this to thinkers who neither specifically refer to his work nor use his terminology. |

影響力と遺産 この記事には、検証されていない情報や無差別な情報が埋め込まれている可能性があります。リストのクリーンアップにご協力ください。(2023年4月)  ケーニヒスベルク大学300周年を祝うポスター(1844年)。とりわけカントとヘルバルトが表彰されている。 カントが西洋思想に与えた影響は多大である[i]、 カントの超越論的観念論の基本的な信条(空間と時間は実在的な性質というよりもむしろ人間の知覚のアプリオリな形式であり、形式論理学と超越論的論理学は 一致するという主張)は近代科学と論理学によって反証されたと主張されており[207][208][209]、もはや現代の哲学者の知的課題を設定するこ とはないが、カントは少なくとも19世紀初頭までの哲学的探究の進め方を革新したと評価されている。この転換は、いくつかの密接に関連した革新から成って おり、それ自体は非常に論争的ではあるが、その後の哲学や広く解釈される社会科学において重要なものとなった: 人間の知覚から独立して存在する物事や、それらが「我々にとって」どのようなものであるかについて哲学することは不可能であるというような、人間の知識に 関する探究の中心であるとみなされる人間主体[210]。 完全にアプリオリに知るという人間の能力に内在する限界を発見し、体系的に探求することが可能であるという概念; 定言命法」という概念、すなわち、人間には正しい理性と行動に対する能力と義務が生まれながらに備わっているという主張。おそらく彼の最も有名な言葉は 『実践理性批判』から引用されたものであろう:「私の心を常に新しく増大する賞賛と畏敬の念で満たすものが二つある:私の頭上にある星空と私の内にある道 徳律である」[211]。 つまり、物事、知識、意識の形態は、それらを可能にする事前の条件の上に成り立っており、それらを理解したり知るためには、いくつかの条件を理解しなけれ ばならないということである; 客観的経験は、人間の心の働きによって積極的に構成または構築されるという主張; 人間性の中心としての道徳的自律性の概念。 人間は単なる手段としてではなく、目的として扱われるべきであるという原則の主張。 カントの思想はさまざまな学派に取り入れられてきた。その中には、ドイツ観念論、[212]マルクス主義、実証主義、現象学、実存主義、批判理論、言語哲 学、構造主義、ポスト構造主義、脱構築などが含まれる[要出典]。 歴史的影響 このセクションでは、検証のために追加の引用が必要です。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。 ソースのないものは異議申し立てされ、削除される可能性があります。(2016年7月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 生前、カントの思想には多くの批判的注目が集まった。彼は1780年代から1790年代にかけて、ラインホルト、フィヒテ、シェリング、ヘーゲル、ノ ヴァーリスに影響を与えた。 ロシア、カリーニングラード(ケーニヒスベルク)のイマヌエル・カント像。1945年に失われたクリスチャン・ダニエル・ラウフ作のオリジナルをハラル ド・ハーケ[de]が複製。 サミュエル・テイラー・コールリッジはカントに大きな影響を受け、イギリスやアメリカでカントやドイツ観念論全般に対する認識を広めるのに貢献した。 Biographia Literaria』(1817年)の中で、彼は、心は受動的なものではなく、現実を理解するための能動的な主体であると信じるようになったのは、カント の思想のおかげであると述べている。 ヘーゲルはカントの最初の主要な批判者の一人であった。ヘーゲルの見解では、「超越論的主体」(すなわち人間の意識)を生きている個人だけでなく自然、歴 史、社会からも切り離して設定するプロジェクト全体には根本的な欠陥があった[213]。同様の懸念は、カントの道徳的自律性の概念に対するヘーゲルの批 判を動機づけるものであり、ヘーゲルは共同体の「倫理的生活」に焦点を当てた倫理に反対していた[j]。ある意味で、ヘーゲルの「倫理的生活」という概念 は、カント的倫理に取って代わるのではなく、むしろそれを包摂することを意図している。そしてヘーゲルは、有限の「欲望」を超える自由というカントの思想 を、理性によって擁護しようとしていると見ることができる。したがって、ニーチェやラッセルのような後の批評家とは対照的に、ヘーゲルはカントの懸念のい くつかを共有している[k]。 宗教に関するカントの考え方は、イギリスではトマス・カーライル[214]のような哲学者によって、19世紀の宗教的信仰の衰退に異議を唱えるために利用 されていた。イギリスのカトリック作家、特にG・K・チェスタートンやヒレール・ベロックはこのアプローチを踏襲していた[citation needed]。カントに対する批判は、当時の新しい実証主義の現実主義的な見解において一般的であった。 アーサー・ショーペンハウアーはカントの超越論的観念論の影響を強く受けていた。彼は、彼以前のG. E. シュルツェ、ヤコービ、フィヒテと同様に、カントの「物自体論」に批判的であった。物自体とは、私たちが観察するものの原因でもなければ、私たちが完全に アクセスできないものでもない、と彼らは主張した。純粋理性批判』以来、哲学者たちはカントの物自体論に批判的である。そのようなものが経験を超えて存在 するのであれば、それが因果的に私たちに影響を及ぼすと仮定することはできないと多くの人が主張してきた。 ヘーゲルの著作の成功と幅広い影響力によって、カント自身の影響力は衰え始めたが、1865年にドイツで「カントへの回帰」をモットーとするオットー・ リープマンによる『カントとエピゴーネン』の出版によって、カントの思想の再検討が始まった。新カント主義として知られるカントの理論哲学の重要な復興が 始まったのである。 カントを称えるワイマール共和国の切手(1926年 カントの「批評」という概念は、より広範に影響を及ぼした。美学においても、クレメント・グリーンバーグはその古典的なエッセイ『モダニズム絵画』におい て、抽象絵画の目的を正当化するためにカント的な批評、すなわちグリーンバーグが「内在的批評」と呼ぶものを用いている。 フランスの哲学者ミシェル・フーコーもまたカントの「批評」の概念に大きな影響を受けており、「批評的思考」の一形態として啓蒙主義を再考するためにカン トに関するいくつかの作品を書いた。彼は自身の哲学を「カントに根ざした近代の批判史」と分類するほどであった[217]。 カントは数学的真理が合成的先験的知識の一形態であると信じていた。つまり、それらは必要かつ普遍的でありながら、経験の超越論的前提条件として空間と時 間の先験的直観を通して知られている。 現代思想家への影響 1974年、カント生誕250周年を記念した西ドイツの切手。 カントは『恒久平和論』によって、政治学における主要な論争のひとつである民主主義的平和論を形成するようになった思想の多くを予見したと考えられている [219]。 [219] より具体的には、構成主義の理論家であるアレクサンダー・ウェントは、国際システムの無政府状態は、現実主義の理論家が理解する「残忍な」ホッブズ的無政 府状態から、ロック的無政府状態を経て、最終的にはカント的無政府状態へと発展し得ると提唱した。 最近の著名なカント主義者には、イギリスの哲学者であるP・F・ストローソン[n]、オノラ・オニール[221]、クアシム・カッサム[222]、アメリ カの哲学者であるウィルフリッド・セラーズ[223]、クリスティーン・コルスガード[o]などがいる。心理学や認知科学の哲学における多くの議論の中心 となっているのは、意識の統一性に関するカントの概念である[p]。 ユルゲン・ハーバーマスとジョン・ロールズは、カントの道徳哲学から強い影響を受けている2人の重要な政治哲学者であり道徳哲学者である[q]。彼らは相 対主義に反対し、普遍性が実行可能な道徳哲学に不可欠であるというカントの見解を支持している[224]。 孟宗三のカント研究は、孟宗三の個人的な哲学、すなわち新儒教の発展において非常に重要な役割を果たしたとされている。中国において最も影響力のあるカン ト学者として広く知られており、カント哲学に対する厳密な批評は、カントの3つの批評をすべて翻訳したものであり、中国における西洋化への圧力が高まる 中、中国哲学と西洋哲学を調和させるための熱心な試みであった[225][226]。 カントを称える東ドイツの記念硬貨、1974年 カントの影響は、マックス・ウェーバーの社会学、ジャン・ピアジェとカール・グスタフ・ユングの心理学、[227][228]ノーム・チョムスキーの言語 学のように、社会科学、行動科学、物理科学にも及んでいる。数学と総合的アプリオリ知識に関するカントの研究はまた、理論物理学者であるアルベルト・アイ ンシュタインによって、後に批判され否定されたものの、彼の知的発達における初期の影響として引用されている[229]。近年、形式論理学とコンピュータ 科学の観点からカントの心の理論に対する関心が再び高まっている[230]。 カントのパラダイムシフトは徹底していたため、カントの影響はこれをはるかに超えて、特にカントの著作に言及することもなく、カントの用語を使用すること もない思想家にまで及んでいる。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immanuel_Kant | |

池内紀『カント先生の散

歩』新潮社、2013,2016年 池内紀『カント先生の散

歩』新潮社、2013,2016年「難解にして深遠、時計の針のように正確無比で謹厳実直、容易に人を寄せ付けない…そんなイメージがガラガラと崩れてしまう、人間「カント先生」の生涯を 描いた伝記風エッセイが、待望の文庫化。就職、友情、お金、そして老い—さらに「批判三部作」完成までの知られざるドラマを、ドイツ文学者で名エッセイス トが優しい筆致で描く。 |

目次 ++++++++++++ バルト海の真珠 教授のポスト メディアの中で 友人の力 永遠の一日 カントの書き方 時代閉塞の中で 教授の時間割 独身者のつれ合い カント総長 一卵性双生児 フランス革命 老いの始まり 検閲闘争 『永遠平和のために』 老いの深まり 「遺作」の前後 死を待つ |

★カントの年譜より(ウィキペディア日本 語などを参照にした)——年譜は「イマヌエル・カント年譜」に引っ越しました!!!

リンク

▶︎カントの哲学について知るには「カント入門」▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

◎福谷茂「カント」加藤尚武編『哲学の歴 史7:理性の劇場』中央公論新社、Pp.76-176、2007年(→「イマ ヌエル・カント入門」)

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Do not paste, but [Re]Think our message for all undergraduate students!!!

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆