人間と動物の情動の表現

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, 1872

☆『人間と動物の表情における感情表現』

は、チャールズ・ダーウィンの進化論に関する主要な著作3作目であり、『種の起源』(1859年)と『人間の由来』、『性淘汰』(1871年)に続くもの

である。当初は『人間の由来』の章として執筆されたが、分量が増えたため、1872年に単独で出版された。ダーウィンは、感情的な行動の生物学的な側面

や、微笑みやしかめっ面、肩をすくめる、驚いて眉を上げる、怒りの嘲笑で歯をむき出すといった人間の特徴の動物的な起源について探求している。

1872年に『表情』のドイツ語訳が出版され、1873年と1874年にはオランダ語版とフランス語版が続いた。『表情』は初版以来絶版になったことはな

いが[要出典]、ダーウィンの「忘れられた傑作」とも評されている[1][2]。心理学者ポール・エクマンは、『表情』は現代の科学心理学の基礎となるテ

キストであると主張している。

ダーウィンの以前には、人間の感情生活は、伝統的な哲学における心と身体のカテゴリーに問題を提起していた。[3][4]

ダーウィンがこのテーマに関心を持ったのは、エディンバラの医学生時代にさかのぼり、1824年に出版されたチャールズ・ベル著『表情の解剖学と哲学』

が、このテーマに精神的な次元を主張していたからである。これに対し、ダーウィンの生物学的なアプローチでは、感情を動物行動に由来するものとして関連づ

け、文化的な要因は感情表現の形成において補助的な役割しか果たさないとしている。この生物学的な強調により、幸福、悲しみ、恐怖、怒り、驚き、嫌悪とい

う6つの異なる感情状態が強調されている。また、表現の普遍的な性質も評価しており、これは人類全体に共通する進化の遺産を暗示している。さらに、ダー

ウィンは、子供の心理的発達における感情的なコミュニケーションの重要性を指摘している。

ダーウィンは、この本の準備として、著名な精神科医、特にジェームズ・クライストン・ブラウン(James

Crichton-Browne)の意見を求めた。この本は、心理学への彼の主な貢献である。

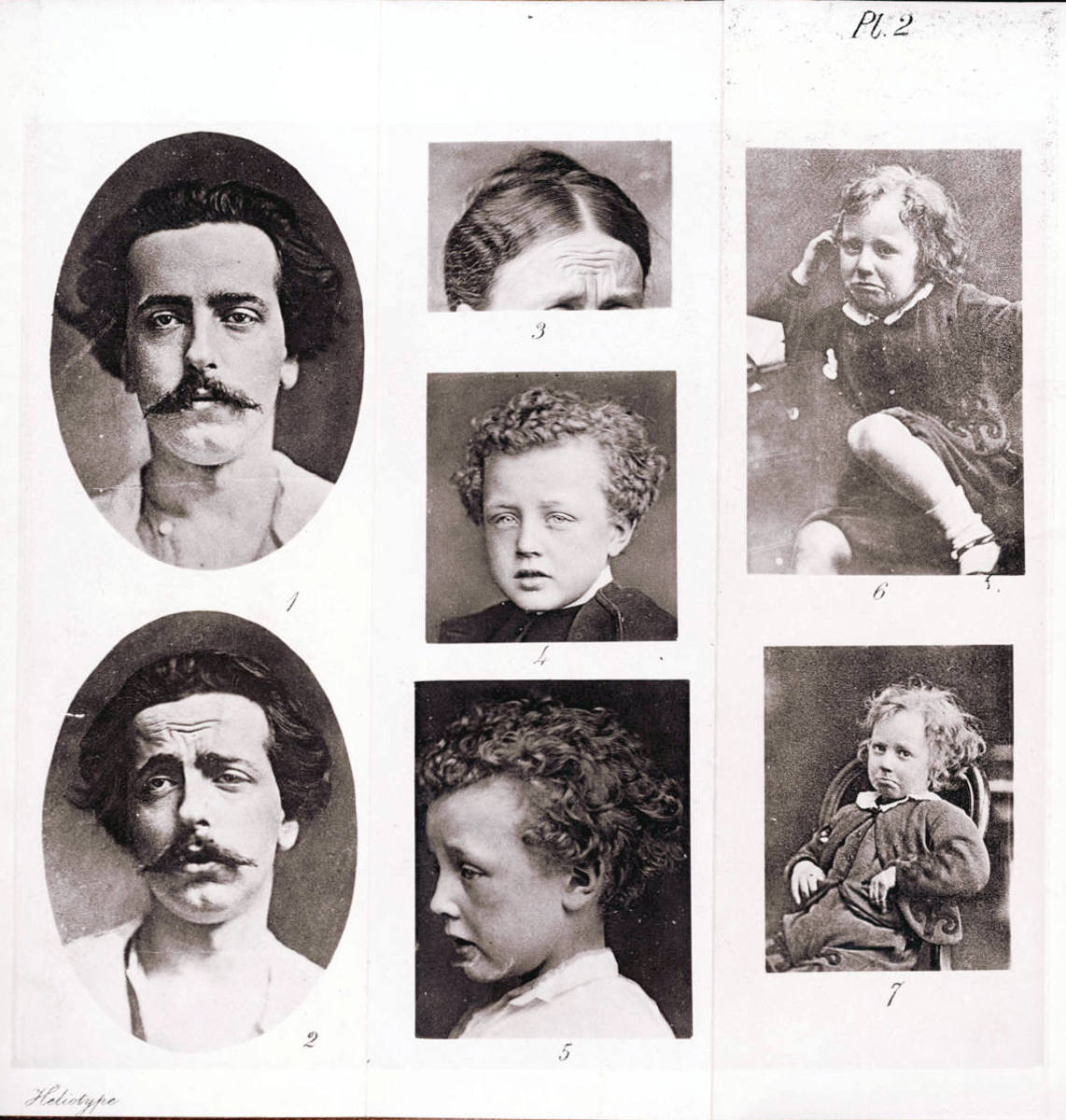

この本にはいくつかの革新が含まれている。ダーウィンは準備研究中に、おそらく従兄弟のフランシス・ガルトンから着想を得たと思われるアンケートを配布し

た[要出典]。また、友人や家族を対象に感情の認識に関する簡単な心理学実験を行い[6]、科学情報の提示に写真を使用した(サレペトリエール病院の医師

デュシェンヌ・ド・ブローニュと同様)。ダーウィンの出版社は、写真を含めると本の利益に「穴が開く」と彼に警告した。[7]

表現は、[誰によって?]本のイラストの歴史における重要な画期的な出来事と考えられている。

| The Expression of

the Emotions in Man and Animals is Charles Darwin's third major work of

evolutionary theory, following On the Origin of Species (1859) and The

Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871). Initially

intended as a chapter in Descent of Man, Expression grew in length and

was published separately in 1872. Darwin explores the biological

aspects of emotional behaviour and the animal origins of human

characteristics like smiling and frowning, shrugging shoulders, lifting

eyebrows in surprise, and baring teeth in an angry sneer. A German translation of Expression appeared in 1872, and Dutch and French versions followed in 1873 and 1874. Though Expression has never been out of print since its first publication,[citation needed] it has also been described as Darwin's "forgotten masterpiece".[1][2] Psychologist Paul Ekman has argued that Expression is the foundational text for modern scientific psychology. Before Darwin, human emotional life had posed problems to the traditional philosophical categories of mind and body.[3][4] Darwin's interest in the subject can be traced to his time as an Edinburgh medical student and the 1824 edition of Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression by Charles Bell, which argued for a spiritual dimension to the subject. In contrast, Darwin's biological approach links emotions to their origins in animal behaviour, allowing cultural factors only an auxiliary role in shaping the expression of emotion. This biological emphasis highlights six different emotional states: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust. It also appreciates the universal nature of expression, implying a shared evolutionary heritage for the entire human species. Darwin also points to the importance of emotional communication with children in their psychological development. Darwin sought out the opinions of some leading psychiatrists, notably James Crichton-Browne, in preparation for the book, which forms his main contribution to psychology.[5] The book involves several innovations: Darwin circulated a questionnaire (probably inspired by his cousin, Francis Galton)[citation needed] during his preparatory research; simple psychology experiments on the recognition of emotions with his friends and family;[6] and (like Duchenne de Boulogne, a physician at the Salpêtrière Hospital) the use of photography in his presentation of scientific information. Darwin's publisher warned him that including the photographs would "make a hole in the profits" of the book.[7] Expression is considered[by whom?] an important landmark in the history of book illustration. |

『人間と動物の表情における感情表現』は、チャールズ・ダーウィンの進

化論に関する主要な著作3作目であり、『種の起源』(1859年)と『人間の由来』、『性淘汰』(1871年)に続くものである。当初は『人間の由来』の

章として執筆されたが、分量が増えたため、1872年に単独で出版された。ダーウィンは、感情的な行動の生物学的な側面や、微笑みやしかめっ面、肩をすく

める、驚いて眉を上げる、怒りの嘲笑で歯をむき出すといった人間の特徴の動物的な起源について探求している。 1872年に『表情』のドイツ語訳が出版され、1873年と1874年にはオランダ語版とフランス語版が続いた。『表情』は初版以来絶版になったことはな いが[要出典]、ダーウィンの「忘れられた傑作」とも評されている[1][2]。心理学者ポール・エクマンは、『表情』は現代の科学心理学の基礎となるテ キストであると主張している。 ダーウィンの以前には、人間の感情生活は、伝統的な哲学における心と身体のカテゴリーに問題を提起していた。[3][4] ダーウィンがこのテーマに関心を持ったのは、エディンバラの医学生時代にさかのぼり、1824年に出版されたチャールズ・ベル著『表情の解剖学と哲学』 が、このテーマに精神的な次元を主張していたからである。これに対し、ダーウィンの生物学的なアプローチでは、感情を動物行動に由来するものとして関連づ け、文化的な要因は感情表現の形成において補助的な役割しか果たさないとしている。この生物学的な強調により、幸福、悲しみ、恐怖、怒り、驚き、嫌悪とい う6つの異なる感情状態が強調されている。また、表現の普遍的な性質も評価しており、これは人類全体に共通する進化の遺産を暗示している。さらに、ダー ウィンは、子供の心理的発達における感情的なコミュニケーションの重要性を指摘している。 ダーウィンは、この本の準備として、著名な精神科医、特にジェームズ・クライストン・ブラウン(James Crichton-Browne)の意見を求めた。この本は、心理学への彼の主な貢献である。 この本にはいくつかの革新が含まれている。ダーウィンは準備研究中に、おそらく従兄弟のフランシス・ガルトンから着想を得たと思われるアンケートを配布し た[要出典]。また、友人や家族を対象に感情の認識に関する簡単な心理学実験を行い[6]、科学情報の提示に写真を使用した(サレペトリエール病院の医師 デュシェンヌ・ド・ブローニュと同様)。ダーウィンの出版社は、写真を含めると本の利益に「穴が開く」と彼に警告した。[7] 表現は、[誰によって?]本のイラストの歴史における重要な画期的な出来事と考えられている。 |

The book's development: biographical aspects Figure 21, "Horror and Agony", from a photograph by Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne (more images) Background In the weeks before Queen Victoria's coronation in 1838, Charles Darwin sought medical advice for his mysterious physical symptoms. He then travelled to Scotland for rest and a "geologising expedition" but also revisited the old haunts of his undergraduate days. On the day of the coronation, 28 June 1838, Darwin was in Edinburgh. Two weeks later, he opened a private notebook—Notebook M—for philosophical and psychological commentary and, over the next three months, filled it with his thoughts about possible interactions of hereditary influences with the psychological aspects of life.[8] Darwin made his first attempt at autobiography in August 1838.[9] Darwin fully grasps his conception of natural selection towards the end of September 1838, after encountering the sixth edition of Essay on Population (1826) by Thomas Malthus.[8][10][11] Unlike in Notebook D and Notebook N, Malthus and his essay are not mentioned in Notebook M. In Notebook M, Darwin writes about conversations with his father—a successful doctor with a special interest in psychiatric problems—about recurring patterns of behavior in successive generations of his patients' families. Howard E. Gruber comments that these passages hint about the genetics of emotions and thought, and there is emphasis on the continuity between sane and insane.[12] Darwin was concerned about the materialistic drift in his thinking and the suspicions this might arouse in early Victorian England. At the time, he was mentally preparing for marriage with his cousin Emma Wedgwood, who held firm Christian beliefs. On 21 September 1838, Notebook M discloses a "confusing" dream where Darwin found himself involved in a public execution; the corpse had come to life and joked about not running away and facing death like a hero.[13] Darwin assembled the central features of his evolutionary theory while developing an appreciation of human behavior and family life; during this period, he experienced significant emotional turmoil. A detailed discussion of the significance of Notebook M can be found in Paul H. Barrett's Metaphysics, Materialism and the Evolution of Mind – Early Writings of Charles Darwin (1980). |

本の展開:伝記的な側面 図21「恐怖と苦悩」ギヨーム・デュシェンヌ・ド・ブローニュ撮影の写真より(他の画像 背景 1838年のヴィクトリア女王の戴冠式を数週間後に控えた頃、チャールズ・ダーウィンは自身の謎めいた身体的症状について医師の診察を受けていた。その 後、休息と「地質学探検」のためにスコットランドを訪れたが、同時に学生時代の旧居も再訪した。戴冠式が行われた1838年6月28日、ダーウィンはエ ディンバラにいた。その2週間後、彼は哲学や心理学に関する考察を書き留めるために、個人用のノートブックMを開き、その後3か月間、遺伝の影響と心理的 側面が相互に作用する可能性について考えを書き留めた。[8] 1838年8月、ダーウィンは初めて自伝の執筆を試みた。[9] トマス・マルサスの『人口論』(1826年)第6版を読んだ後、1838年9月末にダーウィンは自然淘汰の概念を完全に理解した。[8][10][11] ノートブックDやノートブックNとは異なり、ノートブックMではマルサスと彼の論文は言及されていない。 ノートブックMでは、ダーウィンは父親(精神医学問題に特別な関心を持つ成功した医師)との会話について記している。その会話では、患者の家族の世代間で 繰り返される行動パターンについて語られている。ハワード・E・グルーバーは、これらの記述は感情と思考の遺伝について暗示していると指摘しており、正気 と狂気の連続性に重点が置かれていると述べている。 ダーウィンは、自身の考え方が唯物論に傾いていること、そしてそれがヴィクトリア朝初期の英国で疑念を招くのではないかと懸念していた。当時、ダーウィン は、キリスト教の信仰を固く守る従姉妹のエマ・ウェッジウッドとの結婚を控え、精神的に準備を進めていた。1838年9月21日、ノートブックMには、 ダーウィンが公開処刑に立ち会うという「混乱した」夢が記されている。死体が生き返り、逃げずに英雄のように死を迎えるべきだと冗談を言っていたというの だ。 ダーウィンは、人間行動や家庭生活への理解を深めながら、進化論の主要な特徴をまとめあげた。この時期、彼は大きな精神的苦悩を経験した。 ノートブックMの重要性に関する詳細な考察は、ポール・H・バレット著『形而上学、唯物論、そして心の進化 - チャールズ・ダーウィンの初期著作』(1980年)に記載されている。 |

| Development of the text in 1866–1872 In its public management, Darwin understood that his evolutionary theory's relevance to human emotional life could draw an anxious and hostile response. While preparing the text of The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication in 1866, Darwin began to explore topics related to human ancestry, sexual selection, and emotional life. After his initial correspondence with the psychiatrist James Crichton-Browne,[14] Darwin set aside his material concerning emotional expression to complete Descent of Man, which covered human ancestry and sexual selection. He finished work on The Descent of Man on 15 January 1871. Two days later, he began work on The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals and completed most of the text within four months; progress then slowed because of work required on the sixth (and final) edition of The Origin of Species and criticism from St. George Jackson Mivart. Darwin finished his work on the proofs on 22 August 1872. Darwin brings his evolutionary theory close to behavioural science in Expression, although several commentators have perceived a spectral Lamarckism within its text.[15] |

1866年から1872年のテキストの執筆 公的な立場において、ダーウィンは、自身の進化論が人間の感情生活に深く関わっていることが、不安や敵意を招く可能性があることを理解していた。 1866年に『飼育下における動植物の変異』の原稿を準備する中で、ダーウィンは人間の祖先、性的淘汰、感情生活に関するテーマの探究を始めた。精神科医 ジェームズ・クライトン・ブラウンとの最初の書簡のやり取りの後、[14] ダーウィンは感情表現に関する資料を脇に置き、人間の祖先と性的淘汰を扱った『人間の由来』を完成させた。1871年1月15日に『人間の進化』の執筆を 終えた。その2日後には『人間と動物の感情表現』の執筆に取り掛かり、4か月以内にほとんどの文章を書き上げた。その後、『種の起源』の第6版(最終版) の作業と、セント・ジョージ・ジャクソン・ミバートの批判により、作業は遅れた。ダーウィンは1872年8月22日に校正刷りの作業を終えた。 ダーウィンは『表現』で進化論を行動科学に近づけたが、その文章にはラマルク主義の影が潜んでいると指摘する評論家もいる。[15] |

| Universal nature of expression In the book, Darwin notes the universal nature of expressions: "The young and the old of widely different races, both with man and animals, express the same state of mind by the same movements." This connection of mental states to the neurological organisation of movement, suggested by the shared etymological roots of motive and emotion, is central to Darwin's understanding of emotion. Darwin displayed several biographical links between his psychological life and locomotion: taking long, solitary walks around Shrewsbury after his mother died in 1817; in his seashore rambles near Edinburgh with the Lamarckian evolutionist Robert Edmond Grant in 1826 and 1827;[16][17][18] and in laying out the sandwalk, his "thinking path", at Down House in Kent in 1846.[19] These aspects of Darwin's personal life are discussed in the psychoanalytic biography Charles Darwin, A Biography (1990) by John Bowlby.[20] Darwin contrasts his idea of a shared human and animal ancestry to the ideas of Charles Bell, which are aligned with natural theology. Bell claimed that facial muscles were designed to express uniquely human feelings. In the fifth edition of The Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression (1865), Bell stated: "Expression is to passion what language is to thought."[21] In Expression, Darwin reformulates the issues at play: "The force of language is much aided by the expressive movements of the face and body", hinting at a neurological connection between language and psychomotor function.[22] |

表現の普遍性 本の中で、ダーウィンは表現の普遍性について次のように述べている。「人や動物において、異なる人種間の老若男女が、同じ動きによって同じ心理状態を表 す」 動機と感情の語源が同じであることから示唆される、精神状態と神経組織化された動きの関連性は、ダーウィンの感情に対する理解の中心である。 ダーウィンは、自身の心理と移動との間にいくつかの共通点を見出している。1817年に母親が亡くなった後、シュルーズベリー周辺を長時間、一人で散歩し たこと、1826年と1827年にラマルク進化論者のロバート・エドモンド・グラントとエディンバラ近郊の海岸を散策したこと、[16][17][18] そして1846年にケント州のダウン・ハウスに「思考の小道」である砂の小道を敷設したことなどである。 [19] これらのダーウィンの私生活の側面は、ジョン・ボウルビーによる精神分析的伝記『チャールズ・ダーウィン、伝』(1990年)で論じられている。[20] ダーウィンは、人間と動物の共通祖先という自身の考えを、自然神学と一致するチャールズ・ベルの考えと対比させた。ベルは、顔の筋肉は人間特有の感情を表 現するように設計されていると主張した。『表情の解剖学と哲学』(1865年)の第5版で、ベルは「表情は情動にとって、言語が思考にとってそうであるよ うに」と述べている。[21] ダーウィンは『表現』の中で、この問題を再定義し、「言語の力は、顔や身体の表現力豊かな動きによって大いに助けられている」と述べ、言語と精神運動機能 の神経学的つながりを示唆している。[22] |

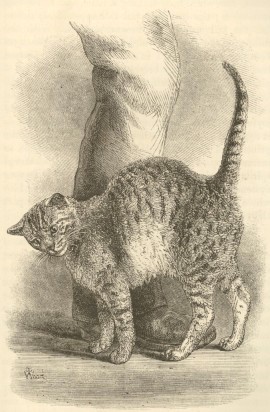

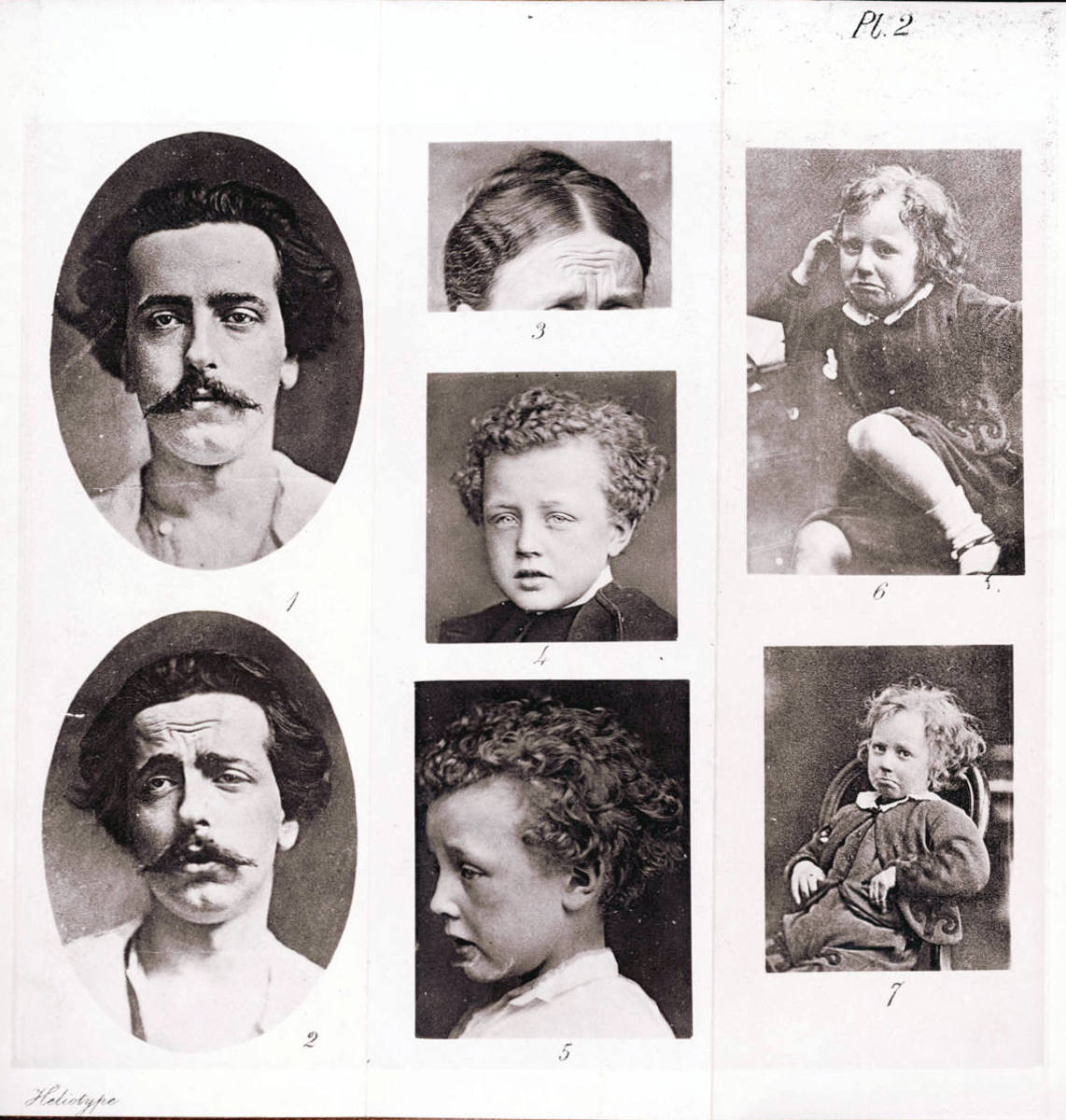

| Darwin's sources on emotional expression Darwin attended debates about psychology at the Plinian Society in December 1826 and March 1827 as a medical student at Edinburgh University. These were prompted by the publication of the second edition of Charles Bell's Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression (1824). In his presentations, the phrenologist William A.F. Browne ridiculed Bell's theological explanations, pointing instead to the similarities of human and animal biology. Both meetings ended in uproar. Darwin revisits these debates 45 years later and refers to Duchenne de Boulogne's Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine as he shifts the debate from philosophical to scientific discourse and highlights the social value of facial expression over vocalisations, tears, and posture. Darwin's response to Bell's natural theology is discussed in Lucy Hartley's Physiognomy and the Meaning of Expression in Nineteenth Century Culture (2001).[23] In the composition of the book, Darwin drew on worldwide responses to his research and findings: His questionnaire (circulated in the early months of 1867) concerning emotional expression in different ethnic groups Anthropological memories from his time on HMS Beagle Conversations with livestock breeders and pigeon fanciers Observations on his infant son William Erasmus Darwin (A Biographical Sketch of an Infant, published in 1877 in the philosophical journal Mind), his family's dogs and cats, and the orangutans at London Zoo Simple psychology experiments with members of his family concerning the recognition of emotional expression The neurological insights of Duchenne de Boulogne, a physician at the Salpêtrière asylum in Paris Hundreds of photographs of actors, babies, and children Descriptions of psychiatric patients in West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum in Wakefield As a result of his domestic psychology experiments, Darwin reduced the number of commonly observed emotions from Duchenne's calculation of more than sixty facial expressions to six "core" expressions: anger, fear, surprise, disgust, happiness, and sadness. Darwin corresponded with James Crichton-Browne, the son of the phrenologist William A. F. Browne and the then medical director of West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum. At the time, Crichton-Browne was publishing The West Riding Lunatic Asylum Medical Reports. Recognising the significant contributions of Crichton-Browne, Darwin suggested to him that Expression "ought to be called by Darwin and Browne?"[24] Darwin also drew on his personal experience of the symptoms of bereavement and studied the text of Henry Maudsley's 1870 Gulstonian Lectures on Body And Mind.[25] Darwin considered other approaches to the study of emotions, such as their depiction in the arts—as discussed by the actor Henry Siddons in his Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action (1807) and by the anatomist Robert Knox in his Manual of Artistic Anatomy (1852)—but abandoned the approaches as unreliable. Only a few sections in Expression mention deception.[26] |

感情表現に関するダーウィンの情報源 ダーウィンは、1826年12月と1827年3月に、エディンバラ大学の医学生としてプリニウス協会で心理学に関する討論会に参加した。これは、チャール ズ・ベル著『解剖学と表現の哲学』(1824年)の第2版が出版されたことを受けて行われたものである。発表の中で、フレノロジスト(頭蓋相学者)のウィ リアム・A・F・ブラウンは ブラウンの発表は、ベルの神学的説明を嘲笑し、代わりに人間と動物の生物学の類似性を指摘するものであった。両方の会議は騒動に終わった。ダーウィンは 45年後にこれらの論争を再訪し、デュシェンヌ・ド・ブローニュの『人間の表情のメカニズム』に言及しながら、論争を哲学的な議論から科学的な議論へと移 行させ、発声、涙、姿勢よりも表情の社会的価値を強調した。 ベルの自然神学に対するダーウィンの反応については、ルーシー・ハーティリーの著書『19世紀文化における人相学と表情の意味』(2001年)で論じられている。[23] この本の構成において、ダーウィンは自身の研究と発見に対する世界中の反応を参考にした。 異なる民族集団における感情表現に関する彼のアンケート(1867年初頭に配布) ビーグル号乗船中の人類学的な記憶 家畜の飼育者や鳩の愛好家との会話 幼い息子ウィリアム・エラスムス・ダーウィン(1877年に哲学誌『マインド』に掲載された「幼児の略歴」)や、家族の犬や猫、ロンドン動物園のオランウータンに関する観察 感情表現の認識に関する家族との簡単な心理学実験 パリのサルペトリエール病院の医師デュシェンヌ・ド・ブローニュによる神経学的な洞察 俳優、赤ちゃん、子供たちの何百枚もの写真 ウェイクフィールドのウェスト・ライディング貧民精神病院の精神科患者の記述 ダーウィンは、国内で実施した心理学実験の結果、デュシェンヌが60以上と算定した顔の表情から、一般的に観察される感情を6つの「コア」な感情、すなわち「怒り」「恐怖」「驚き」「嫌悪」「幸福」「悲しみ」にまで絞り込んだ。 ダーウィンは、フランネル学者ウィリアム・A・F・ブラウンの息子であり、ウェスト・ライディング貧民精神病院の当時の医療ディレクターであったジェーム ズ・クリクトン=ブラウンと文通していた。当時、クリクトン=ブラウンは『ウェスト・ライディング精神病院医療レポート』を発行していた。クリクトン=ブ ラウンの多大な貢献を認めたダーウィンは、彼に「この表現は『ダーウィンとブラウンによるべきである』と提案した。 また、ダーウィンは自身の喪失感の症状に関する個人的な経験を活かし、ヘンリー・モードルジーの1870年のガルストン講義「身体と精神」のテキストを研究した。 ダーウィンは、芸術作品における感情表現の描写など、感情の研究に対する他のアプローチも検討した。俳優ヘンリー・シドンズが著書『修辞的ジェスチャーと アクションの実用的な図解』(1807年)で、また解剖学者ロバート・ノックスが著書『芸術的解剖学マニュアル』(1852年)で論じているようなアプ ローチである。しかし、ダーウィンはそのアプローチを信頼できないとして放棄した。『表現』の中で、欺瞞について言及しているのはわずか数節である。 [26] |

Structure Illustration of grief from The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals Expression opens with three chapters (1–3) entitled "General Principles of Expression", where Darwin introduces three principles: "The principle of serviceable associated Habits" – describes how initially voluntary actions constitute complex expressions of emotion by association of habit. "The principle of Antithesis" – explains how opposite mental states induce directly opposing movements. "The principle of actions due to the constitution of the Nervous System, independently from the first of the Will, and independently to a certain extent of Habit" – discusses the interplay between physiological reactions (e.g., sweating, muscle trembling, blushing) and emotional experiences. In the following chapters (4–6), Darwin presents his findings on modes of emotional expression peculiar to particular species, including humans. Chapters 7–8 contain Darwin's observations on "low spirits" (anxiety, grief, dejection, and despair) and "high spirits" (joy, love, tender feelings, and devotion). Darwin claims that high spirits, exemplified by joy, find their purest expression in laughter. Subsequent chapters (9–13) discuss various emotions and their expression. In his discussion of the emotion "disgust", Darwin notes its close links to the sense of smell and conjectures an association with offensive odours. In chapter 13 (which highlights the emotional states of self-attention, shame, shyness, modesty, and blushing), Darwin describes blushing as "the most peculiar and the most human of all expressions". Darwin closes the book with chapter 14, where he summarises his central argument, demonstrating how human emotions link mental states with bodily movement. He argues that these expressions are genetically determined and derive from purposeful actions observed in animals. He comments on the book's implications, proposing a single origin for the entire human species, with universal human expressions. Darwin emphasises the social value of expression, especially the emotional communication between mother and child. |

構造 『人間と動物の表情における感情表現』より、悲しみのイラスト 表現』は、「表現の一般原則」と題された3つの章(1~3)から始まり、ダーウィンは3つの原則を紹介している。 「役立つ関連習慣の原則」 - 当初は自発的な行動が、習慣の関連によって感情の複雑な表現を構成する仕組みを説明する。 「対立の原則」 - 相反する精神状態が、直接的に相反する動きを引き起こす仕組みを説明する。 「神経系の構成による行動の原理、すなわち、意志によるものとは独立して、またある程度は習慣からも独立して」では、生理的反応(発汗、筋肉の震え、赤面など)と感情体験の相互作用について論じている。 続く第4章から第6章では、人間を含む特定の種に特有な感情表現の様式について、ダーウィンが発見したことを紹介している。 第7章から第8章では、「憂うつ」(不安、悲しみ、落胆、絶望)と「快活」(喜び、愛、優しい感情、献身)に関するダーウィンの観察が述べられている。ダーウィンは、喜びを例とする快活な感情は、笑いによって最も純粋な形で表現されると主張している。 続く第9章から第13章では、さまざまな感情とその表現について論じている。感情「嫌悪」について論じる中で、ダーウィンはその感覚が嗅覚と密接な関係が あることに言及し、不快な臭いとの関連性を推測している。第13章(自己意識、羞恥心、恥じらい、謙虚さ、赤面などの感情状態に焦点を当てている)では、 ダーウィンは赤面を「最も特異的で、最も人間らしい表情」と表現している。 ダーウィンは第14章でこの本を締めくくり、自身の中心的主張を要約し、人間の感情が精神状態と身体の動きをどのように結びつけているかを示している。彼 は、これらの表現は遺伝的に決定され、動物に見られる目的を持った行動から派生していると主張している。彼は、この本が暗示する意味についてコメントし、 人間全体に共通する表現を持つ、人間という種全体の単一の起源を提案している。ダーウィンは、表現の社会的価値、特に母親と子供の間の感情的なコミュニ ケーションを強調している。 |

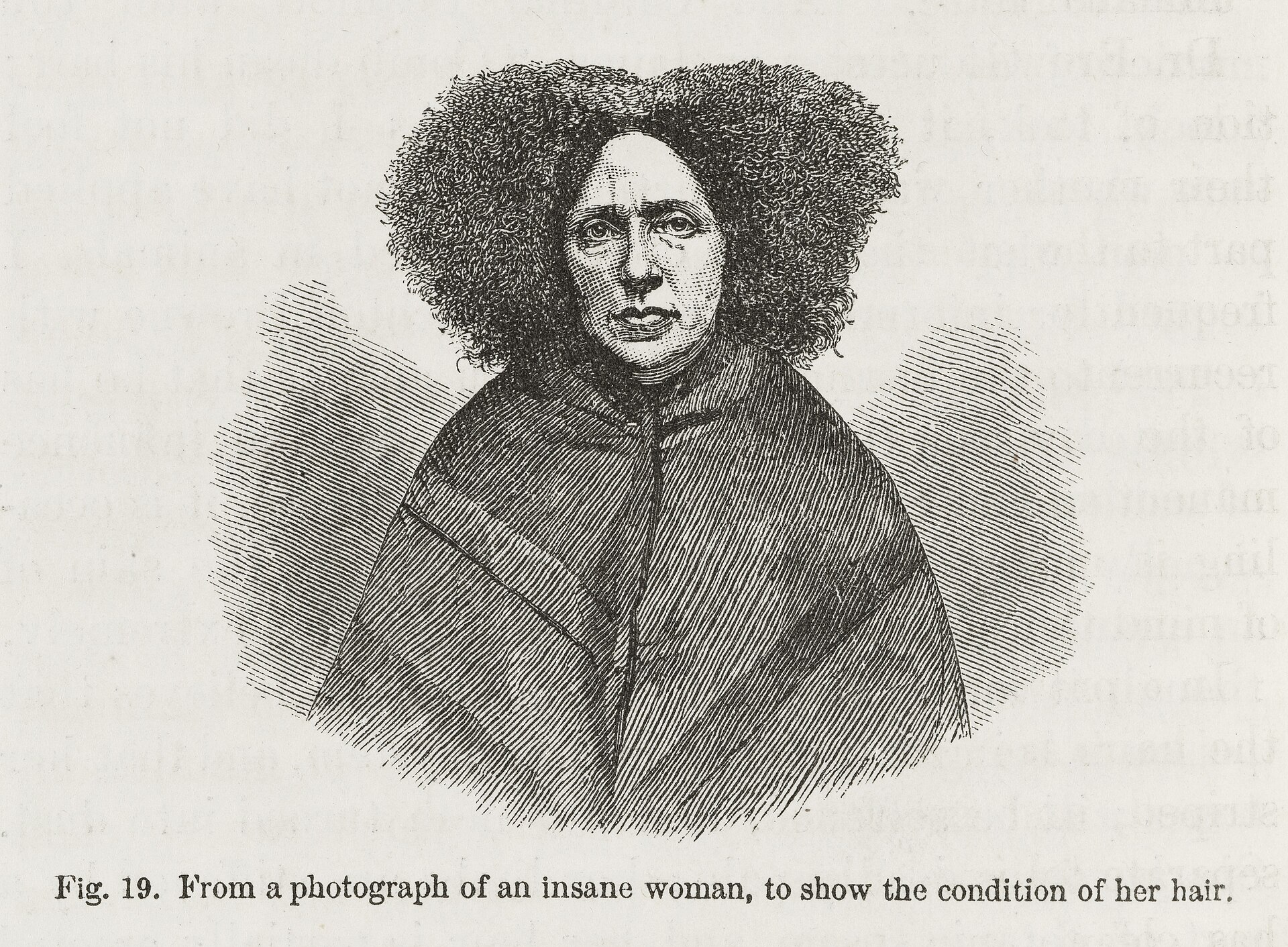

Illustrations Figure 19: "From a photograph of an insane woman, to show the condition of her hair." Because of the limited printing techniques of the 1800s, photographs were usually tipped into the pages of books. This process was expensive and labour-intensive since each photograph had to be printed and tipped in individually. Darwin proposed using heliotype to print the photographs to his publisher—John Murray—believing it would be cheaper.[27] It allowed the illustrations to be bound directly with the pages of text, and the printing plates could be reused, which reduced costs. The printing company Darwin chose for the photographs proved to be expensive. Robert F. Cooke, John Murray III's cousin and partner in his publishing company, expressed concern about the increasing production costs and warned Darwin that including the photographs "will make a terrible hole in the profits of each edition".[7][28] Darwin proceeded with the printing process, and most of Expression was illustrated by photographic prints—with seven heliotype plates; figures 19–21 were printed using woodcuts.[29] The published book contains the work of several artists: Engravings of the Darwin family's domestic pets by the zoological illustrator T. W. Wood Drawings and sketches by Briton Rivière, A. May, and Joseph Wolf Portraits by the Swedish photographer Oscar Rejlander Anatomical diagrams by Charles Bell and Friedrich Henle Illustrative quotations from Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine (1862) by the French neurologist Duchenne de Boulogne (1806–1875).[30] Darwin received dozens of photographs of psychiatric patients from James Crichton-Browne but only included one—photoengraved by James Davis Cooper—titled "Figure 19". It depicts a patient under the care of Dr James Gilchrist at the Southern Counties Asylum in Dumfries. |

イラスト 図19:「狂気の女性の写真から、彼女の髪の毛の状態を示す」 1800年代の印刷技術の限界により、写真は通常、本のページに差し込まれた。このプロセスは、各写真が個別に印刷され、差し込まれる必要があったため、 費用がかかり、手間がかかるものだった。ダーウィンは、より安価であると考え、写真の印刷にヘリオタイプ(写真製版法)の使用を出版社ジョン・マレーに提 案した。[27] ヘリオタイプを使用すれば、図版をテキストのページに直接綴じることができ、印刷版も再利用できるため、コストを削減できる。 ダーウィンが写真の印刷に選んだ印刷会社は、高額な費用がかかった。ジョン・マレー3世の従兄弟であり、彼の出版社の共同経営者でもあったロバート・F・ クックは、増大する制作コストを懸念し、ダーウィンに「写真を含めると、各版の利益に大きな穴が開く」と警告した。[7][28] ダーウィンは印刷工程を進め、ほとんどの『表現』は写真版画で図解された。7枚のヘリオタイプ版を使用し、図19から21は木版画で印刷された。[29] 出版された本には、複数の芸術家の作品が含まれている。 動物画家のT. W. Woodによるダーウィン家のペットの版画 ブリトン・リヴィエール、A. メイ、ジョセフ・ウォルフによる絵画やスケッチ スウェーデンの写真家オスカー・レイランダーによる肖像画 チャールズ・ベルとフリードリヒ・ヘンレによる解剖図 フランス人神経学者デュシェンヌ・ド・ブローニュ(1806年-1875年)著『人間の表情の仕組み』(1862年)からの引用。[30] ダーウィンはジェイムズ・クライストン・ブラウンから何十枚もの精神科患者の写真を受け取ったが、その中にはジェイムズ・デイヴィス・クーパーが写真製版 した「図19」と題された1枚だけが含まれていた。これは、ダンフリースのサザン・カウンティーズ・アサイラムのジェイムズ・ギルクリスト医師の治療を受 けていた患者の写真である。 |

| Publication Darwin concluded work on the book with a sense of relief. The proofs, tackled by his daughter Henrietta ("Ettie") and son Leo, required a major revision, which made Darwin "sick of the subject and myself, and the world".[31] Expression was published by John Murray on 26 November 1872 as a sequel to The Descent of Man and was expected to reach a broad audience in mid-Victorian England. It quickly sold almost 7,000 copies.[32][33] A revised edition was published by Darwin's son in 1890, excluding several revisions suggested by Darwin; these were not published until the 1999 edition, edited by Paul Ekman.[34] |

出版 ダーウィンは安堵の気持ちでこの本の執筆を終えた。娘のヘンリエッタ(愛称エティ)と息子のレオが校正を手がけたが、大幅な修正が必要となり、ダーウィンは「このテーマと私自身、そして世界に嫌気がさした」[31]。 表現』は、1872年11月26日にジョン・マレー社から『人間の由来』の続編として出版され、ヴィクトリア朝中期のイギリスで幅広い読者層に受け入れられることが期待された。この本はすぐに7,000部近くを売り上げた。[32][33] 1890年には、ダーウィンが提案したいくつかの修正を除外した改訂版が、ダーウィンの息子によって出版された。これらの修正は、ポール・エクマンが編集した1999年版まで出版されなかった。[34] |

| Reception [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2013) Contemporary A review in the January 1873 Quarterly Journal of Science concluded that "although some parts are a little tedious, from the amount of minute detail required, there is throughout so much of acute observation and amusing anecdote as to render it perhaps more attractive to general readers than any of Mr. Darwin's previous work".[35] On 24 January 1895, James Crichton-Browne delivered the lecture "On Emotional Expression" in Dumfries, Scotland, presenting some of his reservations about Darwin's views. He argued for a greater role for the higher cortical centres in regulating emotional responses and discussed gender differences in emotional expression.[36] Modern In a 1998 review of Expression, edited by Paul Ekman, Eric Korn argues in the London Review of Books that Margaret Mead and her followers had claimed and subverted the book before Ekman reinterpreted it. Korn notes that Ekman collected evidence supporting Darwin's views on the universality of human expression of emotions, indirectly challenging Mead's views. Korn challenges Ekman's calling Expression "Darwin's lost masterpiece", pointing out that the book has never been out of print since 1872.[37] The editors of the Mead Project website comment that Expression is among the most enduring contributions of 19th-century psychology and argue that although the book lays its foundation on an arguable interpretation of the nature of expression, its ideas continue to influence discussions on emotional experience. The editors cite John Dewey's comments on the book, writing that Darwin's arguments are "wrong but ... compelling".[38] In 2003, the New York Academy of Sciences published Emotions Inside Out: 130 Years after Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, a collection of 37 papers (edited by Paul Ekman) with recent research on the subject. |

レセプション [アイコン] この節は拡大が必要である。 あなたはそれを追加することで手助けができる。 (2013年4月) 現代 1873年1月の『Quarterly Journal of Science』誌の書評では、「多少退屈な部分もあるが、必要とされる詳細の多さから、鋭い観察と興味深い逸話が随所に見られ、おそらくダーウィンのこ れまでのどの著作よりも一般読者にとって魅力的である」と結論づけている。[35] 1895年1月24日、ジェームズ・クライトン・ブラウンはスコットランドのダンフリースで「感情表現について」という講演を行い、ダーウィンの見解に対 する自身の懸念をいくつか提示した。彼は、感情反応を制御する上で大脳皮質の高次中枢がより大きな役割を果たしていると主張し、感情表現における性差につ いても論じた。[36] 現代 ポール・エクマンが編集した『表現』の1998年の書評で、エリック・コーンはロンドン・レビュー・オブ・ブックス誌において、マーガレット・ミードとそ の信奉者たちが、エクマンが再解釈する前にこの本を主張し、転覆させていたと論じている。コーンは、エクマンが人間の感情表現の普遍性に関するダーウィン の見解を裏付ける証拠を集めており、間接的にミードの見解に異議を唱えていると指摘している。コーンは、エクマンが『表現』を「失われたダーウィンの傑 作」と呼んだことに異議を唱え、この本は1872年以来一度も絶版になっていないことを指摘している。 ミード・プロジェクトのウェブサイト編集者は、『表現』は19世紀の心理学における最も不朽の貢献のひとつであると述べ、この本は表現の本質に関する議論 の余地のある解釈を基盤としているが、その考え方は感情体験に関する議論に影響を与え続けていると論じている。編集者は、ジョン・デューイがこの本につい て述べたコメントを引用し、ダーウィンの主張は「誤りではあるが、説得力がある」と書いている。[38] 2003年には、ニューヨーク科学アカデミーが『Emotions Inside Out: 130 Years after Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals』を出版した。これは、このテーマに関する最新の研究論文37編(ポール・エクマン編集)をまとめたものである。 |

Influence Figure 4: "A small dog watching a cat on a table", made from a photograph by Oscar Gustave Rejlander Psychology George Romanes (1848–1894), an advocate of Darwin in comparative psychology, died prematurely, diminishing Darwin's impact on academic psychology. Darwin's impact was further compromised by Wilhelm Wundt's dimensional approach to emotions and the widespread influence of behaviourism during the 20th century. |

影響 図4:「テーブルの上の猫を見つめる小型犬」オスカー・グスタフ・レランダー撮影の写真から作成 心理学 比較心理学におけるダーウィンの支持者であったジョージ・ロマネス(1848年~1894年)は早世し、学術心理学におけるダーウィンの影響力は弱まっ た。ダーウィンの影響力は、ヴィルヘルム・ヴントの感情に対する次元アプローチや、20世紀における行動主義の広範な影響によってさらに損なわれた。 |

| Psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud's early publications on the symptoms of hysteria (with his influential concept of unconscious emotional conflict) acknowledged debts to Darwin's work on emotional expression.[39] All these sensations and innervations belong to the field of The Expression of the Emotions, which, as Darwin (1872) has taught us, consists of actions which originally had a meaning and served a purpose. These may now for the most part have become so much weakened that the expression of them in words seems to us to be only a figurative picture of them, whereas in all probability the description was once meant literally; and hysteria is right in restoring the original meaning of the words.... — Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud, Studies on Hysteria (1895) In 1905, Arthur Mitchell, a psychiatrist and former deputy to William A.F. Browne in the Scottish Lunacy Commission, published About Dreaming, Laughing and Blushing,[40] linking some of Darwin's concerns with those of developing psychology. Psychiatrist John Bowlby extensively references Darwin's ideas in his presentations on attachment theory. Darwin's impact on psychoanalysis is discussed in detail by Lucille Ritvo in Darwin's Influence on Freud: A Tale of Two Sciences (1990).[41] |

精神分析 ジークムント・フロイトによるヒステリーの症状に関する初期の著作(無意識の情動葛藤という影響力のある概念を含む)は、感情表現に関するダーウィンの研究に負うところがある。 これらの感覚や神経のすべては『情動の表現』の分野に属するものであり、ダーウィン(1872年)が教えたように、もともと意味を持ち、目的を果たす行動 から成り立っている。これらの感覚や神経支配は、現在ではほとんどが弱体化しているため、言葉による表現はそれらの比喩的な描写にすぎないように思われる が、おそらくかつてはその記述は文字通りの意味で用いられていたはずであり、ヒステリーは言葉の本来の意味を回復しようとしているのだ。 — ヨーゼフ・ブロイアーとジークムント・フロイト、『ヒステリーに関する研究』(1895年) 1905年には、スコットランド精神異常者委員会のウィリアム・A・F・ブラウン(William A.F. Browne)の元副官であり精神科医であったアーサー・ミッチェル(Arthur Mitchell)が『夢と笑いと赤面について』(About Dreaming, Laughing and Blushing)を出版し、ダーウィンの関心事のいくつかと心理学の発展とを関連付けた。精神科医のジョン・ボウルビー(John Bowlby)は、愛着理論に関する発表の中で、ダーウィンの考え方を広く引用している。 精神分析学におけるダーウィンの影響については、ルシール・リトヴォが『フロイトにおけるダーウィンの影響:2つの科学の物語』(1990年)で詳細に論じている。[41] |

| Evolutionary psychology William James followed up Darwin's ideas in his What Is An Emotion? (1884). In the James–Lange theory of emotions, James develops Darwin's emphasis on the physical aspects, including the autonomically mediated components of emotions. In Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage (1915) by Walter Cannon,[42] Cannon introduces the phrase fight-or-flight response, formulating emotions in terms of strategies for interpersonal behaviour and how these emotions are amplified in groups or crowds—herd behavior. Psychological theories of emotion have also been set out in the Two-factor theory of emotion, put forth by Schachter and Singer, the Papez–Maclean hypothesis, and the theory of constructed emotion.[43] Theories on psychosomatic factors in personality were elaborated by psychiatrist Ernst Kretschmer; neurologist Paul Schilder, with his notion of body image in The Image and Appearance of the Human Body: Studies in the Constructive Energies of the Psyche (1950); and in the theory on somatotypology proposed by William Herbert Sheldon in the 1940s—now largely discredited. Zoologist Desmond Morris further explored the biological aspects of human emotions in his illustrated scientific book Manwatching (1978),[44] and recent research has confirmed that while cultural factors are critical to determining gestures, genetic factors are crucial to forming facial expressions.[citation needed] |

進化心理学 ウィリアム・ジェームズは、ダーウィンの考えを『感情とは何か』(1884年)でさらに発展させた。ジェームズの感情理論では、ジェームズは感情の自律神経による媒介成分を含む身体的側面を強調するダーウィンの考えを発展させた。 ウォルター・キャノンによる『苦痛、飢餓、恐怖、怒りにおける身体の変化』(1915年)[42]では、キャノンは「闘争・逃走反応」という表現を導入 し、感情を対人行動の戦略という観点から、また、これらの感情が集団や群衆の中でどのように増幅されるか(群畜行動)という観点から定式化している。感情 に関する心理学的理論は、シャクターとシンガーによる「感情の2因子理論」、パペッツ・マクリーン仮説、構成感情理論にも示されている。 人格における心身因に関する理論は、精神科医エルンスト・クレッチマー、神経学者ポール・シルダーが著書『人間の身体のイメージと外観:精神の建設的エネ ルギーに関する研究』(1950年)で身体イメージの概念を提示し、また、ウィリアム・ハーバート・シェルドンが1940年代に提唱した体質論(現在はほ とんど否定されている)で詳細に説明されている。動物学者のデズモンド・モリスは、イラスト入りの科学書『人間観察』(1978年)で、人間の感情の生物 学的側面をさらに掘り下げた。[44] 最近の研究では、ジェスチャーを決定する上で文化的要因が重要である一方で、顔の表情を形成する上で遺伝的要因が極めて重要であることが確認されている。 [要出典] |

| Biological illustration The detailed approach to illustrating biological subjects[45] continued in contributions from various authors: photographer Eadweard Muybridge's work on animal locomotion,[46][47] which influenced the development of cinematography; Scottish naturalist James Bell Pettigrew's studies on animal locomotion, documented in his works Animal Locomotion, or, Walking, Swimming and Flying, with a dissertation on Aeronautics (1874) and Design in Nature (1908); the illustrated and controversial works of evolutionary biologist Ernst Haeckel; and to a lesser extent, in On Growth and Form (1917) by D'Arcy Thompson.[48] |

生物のイラスト 生物のイラストを詳細に描くというアプローチは、さまざまな著者による寄稿で継続された。写真家のエドワード・マイブリッジによる動物運動学に関する研究 は、[46][47] 映画撮影技術の発展に影響を与えた。スコットランドの自然主義者ジェームズ・ベル・ペティグリューによる動物運動学の研究は、 『動物運動、あるいは歩行、遊泳、飛行』、『航空学に関する論文』(1874年)、『自然におけるデザイン』(1908年)にまとめられた。また、進化生 物学者エルンスト・ヘッケルの図解付きの論争を呼んだ著作や、ダーシー・トムソンの『成長と形態』(1917年)にも、より限定的ながら影響を受けてい る。[48] |

| Affect display Body language Book illustration Charles Darwin's health Emotion and memory Emotional intelligence Emotions in animals Evolution of emotion Facial expression Nonverbal communication Posture (psychology) |

表情に影響を与えるもの ボディランゲージ 本の挿絵 チャールズ・ダーウィンの保健 感情と記憶 感情的知性 動物における感情 感情の進化 顔の表情 非言語コミュニケーション 姿勢(心理学)17)D'Arcy Thompsonによる。[48] |

| References Abed, Riadh; St John-Smith, Paul (2023). "The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals : Darwin's forgotten masterpiece". BJPsych Advances. 30 (3): 192–194. doi:10.1192/bja.2023.46. ISSN 2056-4678. "Darwin's Other Masterpiece". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 15 July 2024. see, for example, Sartre, Jean-Paul (1971) Sketch for a Theory of the Emotions (with a Preface by Mary Warnock) London: Methuen & Co., originally published (1939) as Esquisse d'une théorie des émotions.[ISBN missing][page needed] Young, Robert M. (1970) Mind, Brain and Adaptation in the Nineteenth Century Oxford: Clarendon Press; reprinted (1990) in History of Neuroscience Series New York: OUP[ISBN missing][page needed] Darwin, Charles (1998). Ekman, Paul (ed.). The expression of the emotions in man and animals (3rd ed.). New York Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511271-9. Snyder, Peter J. et al (2010) Charles Darwin's Emotional Expression "Experiment" and His Contribution to Modern Neuropharmacology Journal of the History of Neurosciences, 19:2, pp. 158–70 Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 8473,” accessed on 17 July 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-8473.xml Darwin, Charles; Barrett, Paul H.; Gruber, Howard E. (1980). Metaphysics, Materialism, & the evolution of mind: the early writings of Charles Darwin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-226-13659-2. Darwin, Charles (2002) Autobiographies, edited by Michael Neve and Sharon Messenger, and introduced by Michael Neve. London: Penguin Classics. In his Introduction (pp. ix–xxiii), Neve makes a detailed survey of this complex area of Darwin's psychological life. Ospovat, Dov (1981) The Development of Darwin's Theory Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Mayr, Ernst (1991) One Long Argument: Charles Darwin and the genesis of modern evolutionary thought Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press Darwin, Charles; Barrett, Paul H.; Gruber, Howard E. (1980). Metaphysics, Materialism, & the evolution of mind: the early writings of Charles Darwin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 6–37, 47–48. ISBN 978-0-226-13659-2. Browne, E. Janet (1995) Charles Darwin: Voyaging, London: Jonathan Cape, pp. 383–84. Pearn, Alison M. (2010) "This Excellent Observer..." : the Correspondence between Charles Darwin and James Crichton-Browne, 1869–75, History of Psychiatry, 21, 160–75 see, for example, Paul Ekman's textual commentary in Darwin, Ekman, Prodger (1998) The Expression of the Emotions, 3rd edition, London: HarperCollins, pp. 45, 54; and see also "Introduction" by Steven Pinker (2008) The Expression of the Emotions London: The Folio Society, pp. xix–xxii. Desmond, Adrian (1982) Archetypes and Ancestors: Palaeontology in Victorian London 1850–1875 Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 116–21 Desmond, Adrian (1989) The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine and Reform in Radical London Chicago: University of Chicago Press Stott, Rebecca (2003) Darwin and the Barnacle London: Faber and Faber Boulter, Michael (2006) Darwin's Garden: Down House and the Origin of Species London: Constable Bowlby, John (1990) Charles Darwin, A Biography London: Hutchinson. Bell, Sir Charles (1865). The Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression: As Connected with the Fine Arts. Henry G. Bohn. p. 198. Bowlby, pp. 6–14 Hartley, Lucy (2001) Physiognomy and the Meaning of Expression in Nineteenth Century Culture Cambridge University Press; see especially chapter 5: Universal expressions: Darwin and the naturalisation of expression, pp. 142 - 179. Walmsley, Tom (December 1993). "Psychiatry in descent: Darwin and the Brownes". Psychiatric Bulletin. 17 (12): 748–751. doi:10.1192/pb.17.12.748. ISSN 0955-6036. Maudsley, Henry (1870) Body And Mind: The Gulstonian Lectures for 1870 London: Macmillan and Co. Ekman, Paul (2003). "Darwin, Deception, and Facial Expression". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1000 (1): 205–221. Bibcode:2003NYASA1000..205E. doi:10.1196/annals.1280.010. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 14766633. Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 7773,” accessed on 17 July 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-7773.xml Charles Darwin (1998). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Oxford University Press. pp. 401–. ISBN 978-0-19-977197-4. Retrieved 4 August 2013. Darwin's English publisher, John Murray, was at first opposed to the idea of using photographs to illustrate the book. He advised Darwin that the inclusion of photographs would make Expression a money-losing proposition Phillip Prodger Curator of Photography Peabody Essex Museum (2009). Darwin's Camera : Art and Photography in the Theory of Evolution. Oxford University Press. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-0-19-972230-3. Retrieved 4 August 2013. Heliotype was a new photomechanical method of reproduction invented by the photographer Ernest Edwards (1837–1903), for whom Darwin had sat for a portrait in 1868. Although he had no experience in photographic publishing, Darwin suggested this new technique to John Murray. ... heliotype reduced the cost of production considerably, enabling Darwin to afford the unprecedented number of photographs appearing in Expression. Duchenne (de Boulogne), G.-B., (1990) The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression by Guillaume-Benjamin (Amand) Duchenne de Boulogne edited and translated by R. Andrew Cuthbertson, Cambridge University Press and Paris: Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de L'Homme, originally published (1862) Paris: Éditions Jules Renouard, Libraire Frederick Burkhardt; Sydney Smith; David Kohn; William Montgomery (1994). A Calendar of the Correspondence of Charles Darwin, 1821–1882. Cambridge University Press. pp. 366–. ISBN 978-0-521-43423-2. To [Leonard Darwin] 29 July [1872] [Down] CD cannot improve style [of Expression] without great changes. 'I am sick of the subject, and myself, and the world'. Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 8763,” accessed on 18 July 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-8763.xml "The success of your work 'on Expression' has been so decided & the Sale so rapid that there is no need for further delay in settling with you for the first 7000—copies, although I have still on hand some 500 copies" Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 9071,” accessed on 18 July 2024, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-9071.xml "I have 404 copies left out of the 7000 previously printed & paid for." Black, J (June 2002), "Darwin in the world of emotions" (Free full text), Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 95 (6): 311–13, doi:10.1177/014107680209500617, ISSN 0141-0768, PMC 1279921, PMID 12042386 Anon (January 1873). "Darwin's 'The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals'". Quarterly Journal of Science: 113–18. Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society. (1896). Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society (Series II, Session 1894-95) (pp. 72–77). Dumfries: The Courier and Herald Offices. Retrieved from https://dgnhas.org.uk/contents_2011 Korn, Eric (November 1998). "How far down the dusky bosom?". London Review of Books. 20 (23): 23–24. "A Mead Project". brocku.ca. 2007. Editors' notes. Retrieved 17 July 2024. Sulloway, Frank J. (1979) Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend London: Burnett Books/Andre Deutsch Mitchell, Sir Arthur (1905) About Dreaming, Laughing and Blushing Edinburgh and London: William Green and Sons. Mitchell (pp. 153–157) provides a useful bibliography on emotional expression at the dawn of the twentieth century. Ritvo, Lucille B. (1990) Darwin's Influence on Freud: A Tale of Two Sciences New Haven and London: Yale University Press Cannon, Walter B. (1915) Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage – An Account of Recent Researches into the Function of Emotional Excitement New York: D. Appleton and Co. Barrett, Lisa Feldman (2017) How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of The Brain New York: Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt and London: Macmillan Morris, Desmond (1978) Manwatching: A Field Guide To Human Behaviour London: Triad Panther. Prodger, Phillip (2009) Darwin's Camera: Art and Photography in the Theory of Evolution Oxford University Press Muybridge, Eadweard (1984) The Male and Female Figure in Motion: 60 classic photographic sequences New York: Dover Publications Prodger, Phillip (2003) Time Stands Still: Muybridge and the instantaneous photography movement The Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for the Visual Arts, Stanford University, in association with Oxford University Press Smith, Jonathan (2006) Charles Darwin and Victorian Visual Culture Cambridge University Press, especially pp. 179–243 Sources Barrett, Paul (1980), Metaphysics, Materialism, & the Evolution of Mind: the early writings of Charles Darwin, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-13659-0, Early writings of Charles Darwin. With a commentary by Howard E. Gruber |

参考文献 Abed, Riadh; St John-Smith, Paul (2023). 「The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals : Darwin's forgotten masterpiece」. BJPsych Advances. 30 (3): 192–194. doi:10.1192/bja.2023.46. ISSN 2056-4678. 「ダーウィンのもう一つの傑作」『ディスカバー』誌。2024年7月15日取得。 例えば、ジャン=ポール・サルトル著『感情の理論のためのスケッチ』(メアリー・ウォーノックによる序文)ロンドン:メスエン・アンド・カンパニー(1971年初版(1939年)『感情の理論のためのスケッチ』として出版)[ISBN欠落][要ページ番号] ヤング、ロバート・M. (1970) 『19世紀における心、脳、適応』オックスフォード:Clarendon Press; ニューヨーク:OUP、ニューヨーク:OUP[ISBN欠落][ページ必要] ダーウィン、チャールズ (1998). エックマン、ポール (編). 『人間と動物における感情表現』(第3版). ニューヨークオックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-511271-9。 Snyder, Peter J. 他 (2010) チャールズ・ダーウィンの感情表現「実験」と現代神経薬理学への貢献 Journal of the History of Neurosciences, 19:2, pp. 158–70 ダーウィン書簡プロジェクト、「手紙第8473号」、2024年7月17日アクセス、https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-8473.xml ダーウィン、チャールズ; バレット、ポール・H.; グルーバー、ハワード・E. (1980). 『形而上学、唯物論、および心の進化:チャールズ・ダーウィンの初期著作』. シカゴ大学出版局. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-226-13659-2. ダーウィン、チャールズ (2002) 『自伝』マイケル・ニーヴとシャロン・メッセンジャー編、マイケル・ニーヴ序文。ロンドン:ペンギン・クラシックス。ニーヴは序文(ix~xxiiiペー ジ)で、ダーウィンの心理的な人生におけるこの複雑な領域について詳細に調査している。 オスポヴァット、ドヴ (1981) 『ダーウィンの理論の発展』ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局 マイヤー、エルンスト(1991)『一つの長い議論:チャールズ・ダーウィンと近代進化思想の起源』マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局 ダーウィン、チャールズ; バレット、ポール H.; グルーバー、ハワード E. (1980). 『形而上学、唯物論、そして心の進化:チャールズ・ダーウィンの初期著作』シカゴ大学出版局。 pp. 6–37, 47–48. ISBN 978-0-226-13659-2. ブラウン、E. ジャネット(1995年)『チャールズ・ダーウィン:航海』ロンドン:ジョナサン・ケープ社、383-84ページ。 ピアーン、アリソン・M.(2010年)「この優れた観察者...」:チャールズ・ダーウィンとジェームズ・クリクトン=ブラウン間の書簡、1869-75年、『精神医学史』21、160-75ページ 例えば、ポール・エクマンのテキスト注釈を参照(ダーウィン、エクマン、プロジャー著『感情表現』第3版、1998年、ロンドン: HarperCollins、45、54ページ)。また、スティーブン・ピンカー著『感情表現』の「序文」(2008年、ロンドン:フォリオ・ソサエ ティ、19~22ページ)も参照のこと。 デズモンド、エイドリアン(1982年)『原形質と祖先:ヴィクトリア朝ロンドンにおける古生物学(1850年~1875年)』シカゴ大学出版、116~121ページ デズモンド、エイドリアン(1989年)『進化の政治学:急進的なロンドンにおける形態学、医学、改革』シカゴ大学出版 ストット、レベッカ(2003年)『ダーウィンとフジツボ』ロンドン: ファベル・アンド・ファベル Boulter, Michael (2006) 『ダーウィンの庭:ダーウッド邸と種の起源』ロンドン:コンスタブル Bowlby, John (1990) 『チャールズ・ダーウィン、伝記』ロンドン:ハッチンソン Bell, Sir Charles (1865). 『表現の解剖学と哲学:美術と関連して』ヘンリー・G・ボーン、198ページ。 ボウルビー、6-14ページ ハートレー、ルーシー(2001年)『19世紀文化における人相学と表情の意味』ケンブリッジ大学出版局、特に第5章「普遍的な表情:ダーウィンと表情の自然化」、142-179ページを参照。 ウォームズリー、トム(1993年12月)「系譜における精神医学:ダーウィンとブラウン家」。Psychiatric Bulletin. 17 (12): 748–751. doi:10.1192/pb.17.12.748. ISSN 0955-6036. Maudsley, Henry (1870) Body And Mind: The Gulstonian Lectures for 1870 London: Macmillan and Co. ポール・エクマン(2003年)「ダーウィン、欺瞞、そして顔の表情」。『ニューヨーク科学アカデミー紀要』1000(1):205-221。 Bibcode:2003NYASA1000..205E. doi:10.1196/annals.1280.010. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 14766633. ダーウィン書簡プロジェクト、「手紙第7773号」、2024年7月17日アクセス、https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-7773.xml チャールズ・ダーウィン (1998年). 『人間と動物の感情表現』オックスフォード大学出版局。401ページ。ISBN 978-0-19-977197-4。2013年8月4日取得。ダーウィンの英語の出版社ジョン・マレーは、当初、この本を写真で説明するというアイデア に反対していた。彼はダーウィンに、写真を入れると『表現』は金銭的に損失を被るだろうと助言した フィリップ・プロジャー(Peabody Essex Museum写真部門学芸員、2009年)。『ダーウィンのカメラ:進化論における芸術と写真』オックスフォード大学出版局、108-110ページ。 ISBN 978-0-19-972230-3。2013年8月4日取得。 ヘリオタイプは、写真家アーネスト・エドワーズ(1837年-1903年)が発明した新しい写真製版技術である。エドワーズは1868年にダーウィンの肖 像写真を撮影した人物である。彼は写真出版の経験はなかったが、ダーウィンはジョン・マレーにこの新しい技術を提案した。... ヘリオタイプは生産コストを大幅に削減し、ダーウィンは『表現』誌に前例のない数の写真を掲載することが可能となった。 デュシェンヌ(ド・ブローニュ)、G.-B.、(1990) 『ヒューマン・フェイシャル・エクスプレッションのメカニズム』 ギヨーム=ベンジャミン(アマンド)・デュシェンヌ・ド・ブローニュ編、R. アンドリュー・カスバートソン訳、ケンブリッジ大学出版局およびパリ:Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de L'Homme、初版(1862)パリ:Éditions Jules Renouard、Libraire フレデリック・ブルクハルト; シドニー・スミス; デイヴィッド・コーエン; ウィリアム・モンゴメリ(1994年)。チャールズ・ダーウィンの書簡集、1821年~1882年。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。366ページ。ISBN 978-0-521-43423-2。レナード・ダーウィン宛て] 1872年7月29日 [下] CDは、表現様式を大幅に変更することなく改善することはできない。「私はこのテーマ、そして自分自身、そして世界にうんざりしている」。 ダーウィン書簡プロジェクト、「手紙第8763号」、2024年7月18日アクセス、https://www.darwinproject。 ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-8763.xml 「『表現について』の成功はすでに決定しており、販売も急速に進んでいるため、最初の7000部についてあなたと清算をさらに遅らせる必要はない。ただ し、まだ500部ほど手元に残っている」 ダーウィン・コレスポンデンス・プロジェクト、「手紙第9071号」、2024年7月18日アクセス、https: //www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-9071.xml 「以前に印刷して支払った7000部中、404部が残っている。」 Black, J (June 2002), 「Darwin in the world of emotions」 (Free full text), Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 95 (6): 311–13, doi:10.1177/014107680209500617, ISSN 0141-0768, PMC 1279921, PMID 12042386 匿名 (1873年1月). 「ダーウィンの『人間と動物の感情表現』」. Quarterly Journal of Science: 113–18. Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society. (1896). Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society (Series II, Session 1894-95) (pp. 72–77). Dumfries: The Courier and Herald Offices. https://dgnhas.org.uk/contents_2011 より取得 Korn, Eric (1998年11月). 「How far down the dusky bosom?」. London Review of Books. 20 (23): 23–24. 「A Mead Project」. brocku.ca. 2007. Editors' notes. Retrieved 17 July 2024. Sulloway, Frank J. (1979) 『精神分析の伝説を超えて:フロイト、心の生物学者』ロンドン:Burnett Books/Andre Deutsch Mitchell, Sir Arthur (1905) 『夢、笑い、赤面について』エディンバラおよびロンドン:William Green and Sons. Mitchell (pp. 153–157) は、20世紀初頭における感情表現に関する有益な参考文献を提供している。 Ritvo, Lucille B. (1990) 『ダーウィンのフロイトへの影響:2つの科学の物語』ニューヘイブン、ロンドン:イェール大学出版局 Cannon, Walter B. (1915) 『苦痛、飢え、恐怖、怒りにおける身体の変化:感情の高ぶりの機能に関する最近の研究報告』ニューヨーク:D. Appleton and Co. Barrett, Lisa Feldman (2017) 『感情はいかにしてつくられるか:脳の秘密の生活』ニューヨーク:Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt、ロンドン:Macmillan Morris, Desmond (1978) 『人間観察:人間行動のフィールドガイド』ロンドン:Triad Panther. Prodger, Phillip (2009) 『ダーウィンのカメラ:進化論における芸術と写真』オックスフォード大学出版局 Muybridge, Eadweard (1984) 『The Male and Female Figure in Motion: 60 classic photographic sequences』ニューヨーク:Dover Publications Prodger, Phillip (2003) 『Time Stands Still: Muybridge and the instantaneous photography movement』スタンフォード大学アイリス・アンド・B・ジェラルド・カントール視覚芸術センター、オックスフォード大学出版局との共同出版 スミス、ジョナサン(2006年)『チャールズ・ダーウィンとヴィクトリア朝の視覚文化』ケンブリッジ大学出版局、特に179~243ページ 出典 ポール・バレット著『形而上学、唯物論、そして心の進化:チャールズ・ダーウィンの初期著作』(1980年、シカゴ大学出版、ISBN 0-226-13659-0)チャールズ・ダーウィンの初期著作。ハワード・E・グルーバーによる解説付き |

| External links Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Darwin, Charles (1872), The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, London: John Murray. Freeman, R. B. (1977), The Works of Charles Darwin: An Annotated Bibliographical Handlist (2nd ed.), Folkestone: Dawson. Ekman, Paul, ed. (2003), Emotions Inside Out: 130 Years after Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1st ed.), New York: New York Academy of Sciences, archived from the original on 1 March 2012, retrieved 29 August 2010. Free e-book versions: D. Appleton, New York, 1899 The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals public domain audiobook at LibriVox |

外部リンク ウィキメディア・コモンズには、人間と動物の表情に関するメディアがある。 チャールズ・ダーウィン (1872年). 『人間と動物の表情における感情表現』. ロンドン: ジョン・マレー. R. B. フリーマン (1977年). 『チャールズ・ダーウィンの著作:注釈付き書誌ハンドリスト(第2版)』. フォークストン: ドーソン. ポール・エクマン編 (2003年), 『Emotions Inside Out: 130 Years after Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1st ed.)』, ニューヨーク: ニューヨーク科学アカデミー, 2012年3月1日にオリジナルからアーカイブ, 2010年8月29日取得. 無料電子書籍版: D. Appleton, New York, 1899 The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals パブリックドメインのオーディオブック、LibriVox |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Expression_of_the_Emotions_in_Man_and_Animals |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099