意識

Consciousness

☆

意識(Consciousness)とは、最も単純に言えば、自分自身の内部または外部環境において、ある状態または対象を認識することである[1]。

しかし、その性質は、哲学者、科学者、神学者の間で、何千年にもわたる分析、説明、議論を引き起こしてきた。意識とはいったい何を研究する必要があるの

か、あるいは意識とみなす必要があるのかについては、意見が異なっている。ある説明では、意識は心と同義であり、またある時は心の一側面である。過去にお

いては、意識とは自分の「内面」であり、内観の世界であり、私的な思考、想像、意志の世界であった。それは意識、意識の意識、メタ認知、自己認識であり、

継続的に変化するかしないかのいずれかであるかもしれない[3][4]。

自己と環境の間の秩序だった区別、単純な覚醒、「内を見る」ことによって探求される自己の感覚や魂、内容の隠喩的な「流れ」であること、または脳の精神状

態、精神的な出来事、精神的なプロセスであることなどである。

| Consciousness,

at its simplest, is awareness of a state or object, either internal to

oneself or in one's external environment.[1] However, its nature has

led to millennia of analyses, explanations, and debate among

philosophers, scientists, and theologians. Opinions differ about what

exactly needs to be studied or even considered consciousness. In some

explanations, it is synonymous with the mind, and at other times, an

aspect of it. In the past, it was one's "inner life", the world of

introspection, of private thought, imagination, and volition.[2] Today,

it often includes any kind of cognition, experience, feeling, or

perception. It may be awareness, awareness of awareness, metacognition,

or self-awareness, either continuously changing or not.[3][4] The

disparate range of research, notions, and speculations raises a

curiosity about whether the right questions are being asked.[5] Examples of the range of descriptions, definitions or explanations are: ordered distinction between self and environment, simple wakefulness, one's sense of selfhood or soul explored by "looking within"; being a metaphorical "stream" of contents, or being a mental state, mental event, or mental process of the brain. |

意識とは、最も単純に言えば、自分自身の内部または外部環境において、

ある状態または対象を認識することである[1]。しかし、その性質は、哲学者、科学者、神学者の間で、何千年にもわたる分析、説明、議論を引き起こしてき

た。意識とはいったい何を研究する必要があるのか、あるいは意識とみなす必要があるのかについては、意見が異なっている。ある説明では、意識は心と同義で

あり、またある時は心の一側面である。過去においては、意識とは自分の「内面」であり、内観の世界であり、私的な思考、想像、意志の世界であった。それは

意識、意識の意識、メタ認知、自己認識であり、継続的に変化するかしないかのいずれかであるかもしれない[3][4]。 自己と環境の間の秩序だった区別、単純な覚醒、「内を見る」ことによって探求される自己の感覚や魂、内容の隠喩的な「流れ」であること、または脳の精神状 態、精神的な出来事、精神的なプロセスであることなどである。 |

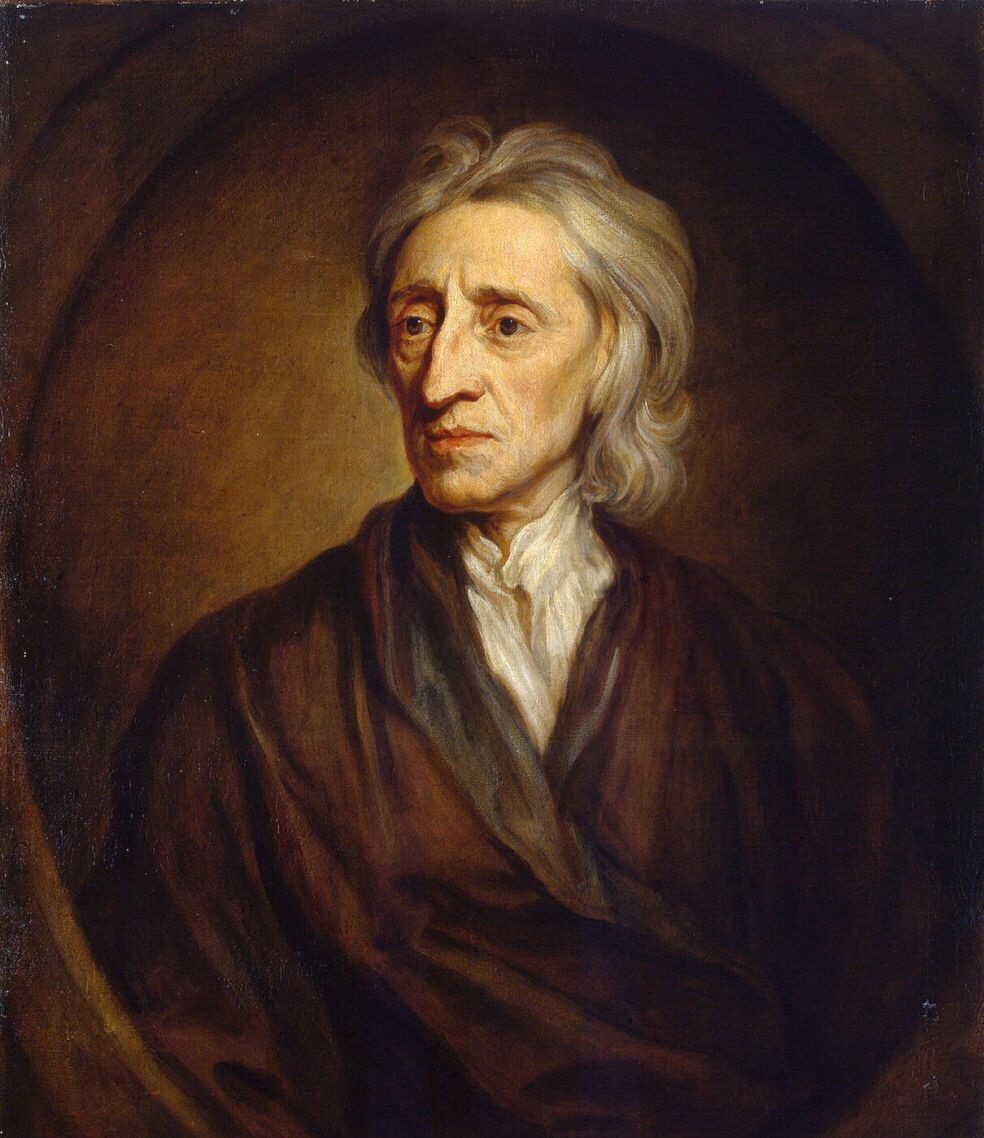

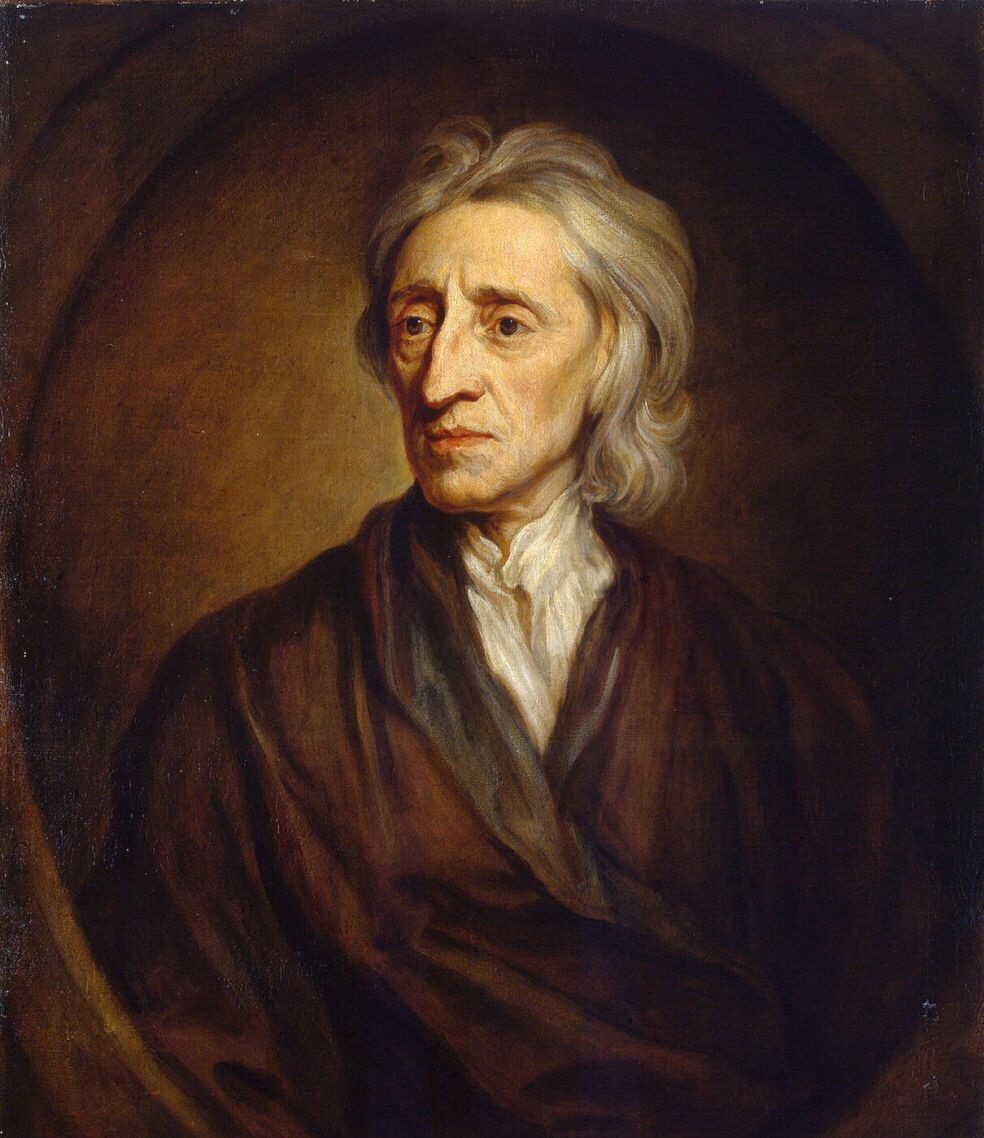

| Etymology The words "conscious" and "consciousness" in the English language date to the 17th century, and the first recorded use of "conscious" as a simple adjective was applied figuratively to inanimate objects ("the conscious Groves", 1643).[6]: 175 It derived from the Latin conscius (con- "together" and scio "to know") which meant "knowing with" or "having joint or common knowledge with another", especially as in sharing a secret.[7] Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan (1651) wrote: "Where two, or more men, know of one and the same fact, they are said to be Conscious of it one to another".[8] There were also many occurrences in Latin writings of the phrase conscius sibi, which translates literally as "knowing with oneself", or in other words "sharing knowledge with oneself about something". This phrase has the figurative sense of "knowing that one knows", which is something like the modern English word "conscious", but it was rendered into English as "conscious to oneself" or "conscious unto oneself". For example, Archbishop Ussher wrote in 1613 of "being so conscious unto myself of my great weakness".[9] The Latin conscientia, literally 'knowledge-with', first appears in Roman juridical texts by writers such as Cicero. It means a kind of shared knowledge with moral value, specifically what a witness knows of someone else's deeds.[10][11] Although René Descartes (1596–1650), writing in Latin, is generally taken to be the first philosopher to use conscientia in a way less like the traditional meaning and more like the way modern English speakers would use "conscience", his meaning is nowhere defined.[12] In Search after Truth (Regulæ ad directionem ingenii ut et inquisitio veritatis per lumen naturale, Amsterdam 1701) he wrote the word with a gloss: conscientiâ, vel interno testimonio (translatable as "conscience, or internal testimony").[13][14] It might mean the knowledge of the value of one's own thoughts.[12]  John Locke, a 17th-century British Age of Enlightenment philosopher The origin of the modern concept of consciousness is often attributed to John Locke who defined the word in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, published in 1690, as "the perception of what passes in a man's own mind".[15][16] The essay strongly influenced 18th-century British philosophy, and Locke's definition appeared in Samuel Johnson's celebrated Dictionary (1755).[17] The French term conscience is defined roughly like English "consciousness" in the 1753 volume of Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopédie as "the opinion or internal feeling that we ourselves have from what we do".[18] |

語源 英語における 「conscious 」や 「consciousness 」の語源は17世紀に遡り、単純な形容詞として 「conscious 」が初めて使われたのは、無生物に対して比喩的に適用されたものである(「the conscious Groves」, 1643)[6]: 175ラテン語のconsciousius(con-「一緒に」、scio「知る」)に由来し、「一緒に知っている」、「他の人と共 同または共通の知識を持つ」、特に秘密を共有することを意味する[7]。トマス・ホッブズは『リヴァイアサン』(1651年)の中で、「2人以上の人間が 1つの同じ事実を知っている場合、彼らはそれを互いに意識していると言われる」と書いている。 [8]また、ラテン語の著作には、conscius sibiという表現が多く登場する。これは、直訳すると「自分自身で知っている」、言い換えると「何かについて自分自身で知識を共有している」となる。こ のフレーズは「自分が知っていることを知っている」という比喩的な意味を持っており、現代英語の「conscious(意識的な)」に似ているが、英語で は「conscious to oneself(自分自身に意識的な)」あるいは「conscious unto oneself(自分自身に意識的な)」と表現された。例えば、アッシャー大司教は1613年に「自分の大きな弱さを自分自身に自覚している」と書いてい る[9]。 ラテン語のconscientiaは、文字通り「知識-共に」という意味で、キケロなどのローマ法学書に初めて登場する。ルネ・デカルト(1596- 1650)はラテン語で著述しており、一般的には、伝統的な意味よりも現代の英語話者が「conscientia」を使用する方法に近い形で conscientiaを使用した最初の哲学者であると考えられているが、彼の意味はどこにも定義されていない。 [12] 彼は『真理の探究』(Regulæ ad directionem ingenii ut et inquisitio veritatis per lumen naturale、アムステルダム、1701年)の中で、この言葉を「conscientiâ, vel interno testimonio」(「良心、あるいは内的証言」と訳すことができる)という用語とともに記している[13][14]。  ジョン・ロック、17世紀イギリスの啓蒙時代の哲学者 現代的な意識の概念の起源は、しばしばジョン・ロックにあるとされ、彼は1690年に出版された『人間理解に関する試論』において、この言葉を「人間自身 の心の中を通過するものの知覚」と定義した[15][16]。この試論は18世紀のイギリス哲学に強い影響を与え、ロックの定義はサミュエル・ジョンソン の有名な『辞書』(1755年)に掲載された[17]。 フランス語の良心という用語は、ディドロとダランベールの『百科全書』(1753年)の中で、英語の「consciousness(意識)」と大まかに同じように、「私たちが行うことから私たち自身が抱く意見や内的感情」と定義されている[18]。 |

| Problem of definition About forty meanings attributed to the term consciousness can be identified and categorized based on functions and experiences. The prospects for reaching any single, agreed-upon, theory-independent definition of consciousness appear remote.[19] Scholars are divided as to whether Aristotle had a concept of consciousness. He does not use any single word or terminology that is clearly similar to the phenomenon or concept defined by John Locke. Victor Caston contends that Aristotle did have a concept more clearly similar to perception.[20] Modern dictionary definitions of the word consciousness evolved over several centuries and reflect a range of seemingly related meanings, with some differences that have been controversial, such as the distinction between inward awareness and perception of the physical world, or the distinction between conscious and unconscious, or the notion of a mental entity or mental activity that is not physical. The common-usage definitions of consciousness in Webster's Third New International Dictionary (1966) are as follows: awareness or perception of an inward psychological or spiritual fact; intuitively perceived knowledge of something in one's inner self inward awareness of an external object, state, or fact concerned awareness; INTEREST, CONCERN—often used with an attributive noun [e.g. class consciousness] the state or activity that is characterized by sensation, emotion, volition, or thought; mind in the broadest possible sense; something in nature that is distinguished from the physical the totality in psychology of sensations, perceptions, ideas, attitudes, and feelings of which an individual or a group is aware at any given time or within a particular time span—compare STREAM OF CONSCIOUSNESS waking life (as that to which one returns after sleep, trance, fever) wherein all one's mental powers have returned . . . the part of mental life or psychic content in psychoanalysis that is immediately available to the ego—compare PRECONSCIOUS, UNCONSCIOUS The Cambridge English Dictionary defines consciousness as "the state of understanding and realizing something".[21] The Oxford Living Dictionary defines consciousness as "[t]he state of being aware of and responsive to one's surroundings", "[a] person's awareness or perception of something", and "[t]he fact of awareness by the mind of itself and the world".[22] Philosophers have attempted to clarify technical distinctions by using a jargon of their own. The corresponding entry in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1998) reads: |

定義の問題 意識という用語には、機能や経験に基づいて約40の意味が特定され、分類することができる。単一の、合意された、理論に依存しない意識の定義に到達する見込みは遠いと思われる[19]。 アリストテレスに意識の概念があったかどうかについては、学者の間でも意見が分かれている。アリストテレスは、ジョン・ロックが定義した現象や概念と明ら かに類似した単語や用語を使用していない。ヴィクター・カストンは、アリストテレスは知覚にもっと明確に似た概念を持っていたと主張している[20]。 現代の辞書による意識という言葉の定義は数世紀にわたって発展し、一見関連するように見える様々な意味を反映しているが、内なる意識と物理的世界の知覚の区別や、意識と無意識の区別、物理的ではない精神的実体や精神活動の概念など、論争を呼んでいるいくつかの相違もある。 ウェブスター第3新国際辞典(1966年)における意識の一般的な定義は以下の通りである: 内面的な心理的または精神的な事実に対する意識または認識;自己の内面にある何かを直感的に認識する。 外的な対象、状態、または事実に対する内向きの認識。 関係する意識;INTEREST、CONCERN-しばしば属性名詞[例えば階級意識]とともに用いられる。 感覚、感情、意志、または思考によって特徴づけられる状態または活動。 心理学において、個人または集団が任意の時点または特定の時間スパンで認識している感覚、知覚、アイデア、態度、および感情の総体-STREAM OF CONSCIOUSNESSと比較する。 覚醒生活(睡眠、トランス状態、発熱の後に戻る生活として)。 精神分析における精神生活または精神的内容のうち、自我がすぐに利用できる部分。 ケンブリッジ英語辞典は意識を「何かを理解し、実現する状態」と定義している[21]。オックスフォード・リビング辞典は意識を「周囲を認識し、それに反応する状態」、「人格が何かを認識すること」、「自分自身と世界について心が認識すること」と定義している[22]。 哲学者たちは独自の専門用語を用いることで、技術的な区別を明確にしようとしてきた。Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy』(1998年)の該当項目にはこうある: |

| Consciousness Philosophers have used the term consciousness for four main topics: knowledge in general, intentionality, introspection (and the knowledge it specifically generates) and phenomenal experience... Something within one's mind is 'introspectively conscious' just in case one introspects it (or is poised to do so). Introspection is often thought to deliver one's primary knowledge of one's mental life. An experience or other mental entity is 'phenomenally conscious' just in case there is 'something it is like' for one to have it. The clearest examples are: perceptual experience, such as tastings and seeings; bodily-sensational experiences, such as those of pains, tickles and itches; imaginative experiences, such as those of one's own actions or perceptions; and streams of thought, as in the experience of thinking 'in words' or 'in images'. Introspection and phenomenality seem independent, or dissociable, although this is controversial.[23] |

意識 哲学者たちは、意識という言葉を、知識一般、意図主義、内省(と、内省が特に生み出す知識)、現象体験という4つの主要なトピックに使ってきた。自分の心 の中にある何かが「内観的に意識される」のは、それを内観した場合(あるいは内観する態勢にある場合)だけである。内観はしばしば、自分の精神生活に関す る主要な知識を提供すると考えられている。経験やその他の精神的実体は、それを持つ「ような何か」がある場合にのみ、「現象的に意識される」のである。最 も明確な例は、味覚や視覚などの知覚的経験、痛みやくすぐったさ、かゆみなどの身体感覚的経験、自分自身の行動や知覚などの想像的経験、「言葉で」「イ メージで」考える経験などの思考の流れである。内観と現象性は独立したもの、あるいは解離可能なもののように思われるが、これには議論の余地がある [23]。 |

| Traditional metaphors for mind During the early 19th century, the emerging field of geology inspired a popular metaphor that the mind likewise had hidden layers "which recorded the past of the individual".[24]: 3 By 1875, most psychologists believed that "consciousness was but a small part of mental life",[24]: 3 and this idea underlies the goal of Freudian therapy, to expose the unconscious layer of the mind. Other metaphors from various sciences inspired other analyses of the mind, for example: Johann Friedrich Herbart described ideas as being attracted and repulsed like magnets; John Stuart Mill developed the idea of "mental chemistry" and "mental compounds", and Edward B. Titchener sought the "structure" of the mind by analyzing its "elements". The abstract idea of states of consciousness mirrored the concept of states of matter. In 1892, William James noted that the "ambiguous word 'content' has been recently invented instead of 'object'" and that the metaphor of mind as a container seemed to minimize the dualistic problem of how "states of consciousness can know" things, or objects;[25]: 465 by 1899 psychologists were busily studying the "contents of conscious experience by introspection and experiment".[26]: 365 Another popular metaphor was James's doctrine of the stream of consciousness, with continuity, fringes, and transitions.[25]: vii [a] James discussed the difficulties of describing and studying psychological phenomena, recognizing that commonly-used terminology was a necessary and acceptable starting point towards more precise, scientifically justified language. Prime examples were phrases like inner experience and personal consciousness: The first and foremost concrete fact which every one will affirm to belong to his inner experience is the fact that consciousness of some sort goes on. 'States of mind' succeed each other in him. [...] But everyone knows what the terms mean [only] in a rough way; [...] When I say every 'state' or 'thought' is part of a personal consciousness, 'personal consciousness' is one of the terms in question. Its meaning we know so long as no one asks us to define it, but to give an accurate account of it is the most difficult of philosophic tasks. [...] The only states of consciousness that we naturally deal with are found in personal consciousnesses, minds, selves, concrete particular I's and you's.[25]: 152–153 |

心の伝統的隠喩 19世紀初頭、地質学という新たな分野に触発され、心にも同様に「個人の過去を記録した」層が隠されているという隠喩が流行した[24]: 3 1875年までには、ほとんどの心理学者は「意識は精神生活のごく一部に過ぎない」と考えていた[24]: そしてこの考えは、心の無意識の層を暴くとい うフロイトの治療の目標の根底にある。 様々な科学からの他の隠喩は、例えば、心の他の分析に影響を与えた: ジョン・スチュアート・ミルは「精神化学」と「精神化合物」の考えを発展させ、エドワード・B・ティッチナーはその「要素」を分析することによって心の 「構造」を探った。意識の状態という抽象的な考え方は、物質の状態という概念を反映していた。 1892年、ウィリアム・ジェームズは「『物体』の代わりに『内容』というあいまいな言葉が最近発明された」と指摘し、容器としての心の隠喩は、「意識の 状態がどのように物事、つまり物体を知ることができるのか」という二元論的な問題を最小化するように思えたと述べている[25]: 465 1899年までに心理学者たちは「内観と実験によって意識的経験の内容」を忙しく研究していた[26]: 365 もう一つのよく知られた隠喩は、連続性、縁、移行を伴うジェイムズの意識の流れの教義であった[25]: vii [a]。 ジェイムズは、心理学的現象を記述し研究することの難しさについて議論し、一般的に使用されている用語は、より正確で科学的に正当化された言語に向けて必要かつ許容可能な出発点であると認識していた。その典型的な例が、内的経験や人格意識といった表現である: 誰もが自分の内的体験に属すると断言する第一の具体的事実は、ある種の意識が続いているという事実である。心の状態」は、彼の中で互いに引き継がれる。 [...)しかし、誰もがその用語の意味を(大まかにしか)知らない。私があらゆる「状態」や「思考」が人格意識の一部であると言うとき、「人格意識」は 問題の用語の一つである。誰もその定義を求めない限り、その意味はわかるが、それを正確に説明することは、哲学の仕事の中でも最も難しいことである。[私 たちが自然に扱う意識の状態は、個人意識、人格、自我、個別主義的な「私」と「あなた」の中にしかない: 152-153 |

| From introspection to awareness and experience Prior to the 20th century, philosophers treated the phenomenon of consciousness as the "inner world [of] one's own mind", and introspection was the mind "attending to" itself,[b] an activity seemingly distinct from that of perceiving the 'outer world' and its physical phenomena. In 1892 William James noted the distinction along with doubts about the inward character of the mind: 'Things' have been doubted, but thoughts and feelings have never been doubted. The outer world, but never the inner world, has been denied. Everyone assumes that we have direct introspective acquaintance with our thinking activity as such, with our consciousness as something inward and contrasted with the outer objects which it knows. Yet I must confess that for my part I cannot feel sure of this conclusion. [...] It seems as if consciousness as an inner activity were rather a postulate than a sensibly given fact...[25]: 467 By the 1960s, for many philosophers and psychologists who talked about consciousness, the word no longer meant the 'inner world' but an indefinite, large category called awareness, as in the following example: It is difficult for modern Western man to grasp that the Greeks really had no concept of consciousness in that they did not class together phenomena as varied as problem solving, remembering, imagining, perceiving, feeling pain, dreaming, and acting on the grounds that all these are manifestations of being aware or being conscious.[28]: 4 Many philosophers and scientists have been unhappy about the difficulty of producing a definition that does not involve circularity or fuzziness.[29] In The Macmillan Dictionary of Psychology (1989 edition), Stuart Sutherland emphasized external awareness, and expressed a skeptical attitude more than a definition: Consciousness—The having of perceptions, thoughts, and feelings; awareness. The term is impossible to define except in terms that are unintelligible without a grasp of what consciousness means. Many fall into the trap of equating consciousness with self-consciousness—to be conscious it is only necessary to be aware of the external world. Consciousness is a fascinating but elusive phenomenon: it is impossible to specify what it is, what it does, or why it has evolved. Nothing worth reading has been written on it.[29] Using 'awareness', however, as a definition or synonym of consciousness is not a simple matter: If awareness of the environment . . . is the criterion of consciousness, then even the protozoans are conscious. If awareness of awareness is required, then it is doubtful whether the great apes and human infants are conscious.[26] In 1974, philosopher Thomas Nagel used 'consciousness', 'conscious experience', 'subjective experience' and the 'subjective character of experience' as synonyms for something that "occurs at many levels of animal life ... [although] it is difficult to say in general what provides evidence of it."[30] Nagel's terminology also included what has been described as "the standard 'what it's like' locution"[31] in reference to the impenetrable subjectivity of any organism's experience which Nagel referred to as "inner life" without implying any kind of introspection. On Nagel's approach, Peter Hacker commented:[32]: 158 "Consciousness, thus conceived, is extended to the whole domain of 'experience'—of 'Life' subjectively understood." He regarded this as a "novel analysis of consciousness"[5]: 14 and has been particularly critical of Nagel's terminology and its philosophical consequences.[5] In 2002 he attacked Nagel's 'what it's like' phrase as "malconstructed" and meaningless English—it sounds as if it asks for an analogy, but does not—and he called Nagel's approach logically "misconceived" as a definition of consciousness.[32] In 2012 Hacker went further and asserted that Nagel had "laid the groundwork for ... forty years of fresh confusion about consciousness" and that "the contemporary philosophical conception of consciousness that is embraced by the 'consciousness studies community' is incoherent".[5]: 13-15 |

内観から意識と経験へ 20世紀以前、哲学者たちは意識という現象を「自分自身の心の内なる世界」として扱い、内観とは心が自分自身に「意識を向ける」ことであり[b]、「外 界」やその物理現象を知覚することとは一見異なる活動であった。1892年、ウィリアム・ジェームズは、心の内面的な性格についての疑念とともに、この区 別を指摘した: 物」は疑われてきたが、思考や感情は疑われたことがない。外界は疑われてきたが、内界が否定されることはなかった。誰もが、自分の思考活動や、自分の意識 は内側にあるものであり、その意識が知っている外側の対象とは対照的なものであるということを、直接的に内観的に知っていると思い込んでいる。しかし正直 言って、私はこの結論に確信を持てない。[内面的な活動としての意識は、感覚的に与えられた事実というよりも、むしろ仮定であるかのようである... [25]: 467 1960年代になると、意識について語る多くの哲学者や心理学者にとって、この言葉はもはや「内なる世界」を意味するのではなく、次の例のように、意識と呼ばれる不定で大きなカテゴリーを意味するようになった: 問題解決、記憶、想像、知覚、痛覚、夢想、行動など、さまざまな現象を、これらはすべて意識的であること、あるいは意識的であることの現れであるという理 由で分類しなかったという点で、ギリシア人が本当に意識という概念を持っていなかったということを、現代の西洋人が理解するのは難しい[28]: 4 マクミラン心理学辞典』(1989年版)の中で、スチュアート・サザーランドは外的な意識を強調し、定義よりも懐疑的な態度を表明している: 意識-知覚、思考、感情を持つこと。この用語は、意識が何を意味するのかを把握しなければ理解できない用語でしか定義することは不可能である。多くの人 が、意識を自己意識と同一視する罠に陥る。意識とは何なのか、何をしているのか、なぜ進化したのかを特定することは不可能である。読むに値するものは何も 書かれていない[29]。 しかし、「意識」を意識の定義や同義語として使うことは、単純な問題ではない: 環境を意識することが意識の基準であるなら、「意識」の定義や同義語として「意識」を使うことは単純な問題ではない。環境に対する意識が意識の基準である ならば、原生動物でさえ意識があることになる。もし意識に対する認識が必要であるならば、類人猿や人間の幼児が意識を持っているかどうかは疑わしい [26]。 1974年、哲学者トーマス・ネーゲルは「意識」、「意識的経験」、「主観的経験」、「経験の主観的性格」を、「動物生活の多くのレベルで生じ る......」何かの同義語として使用した。[ネーゲルの用語法には、「標準的な『それはどのようなものか』という言い回し」[31]と表現されるもの も含まれており、これはネーゲルが「内的生活」と呼んでいるあらゆる生物の経験の不可解な主観性に言及している。ネーゲルのアプローチについてピーター・ ハッカーは次のようにコメントしている[32]: 158「このように考えられた意識は、主観的に理解される『経験』-『生命』-の全領域に拡張され る」。彼はこれを「意識の斬新な分析」とみなした[5]: 2002年、ハッカーはネーゲルの「What it's like(それはどのようなものなのか)」というフレーズを「malconstructed(誤った構造化)」で無意味な英語であり、類推を求めているよ うに聞こえるがそうではないとして攻撃し、ネーゲルのアプローチを意識の定義として論理的に「misconceived(誤った考え)」と呼んだ [32]。 [32]2012年、ハッカーはさらに踏み込んで、ネーゲルは「意識に関する40年にわたる新鮮な混乱の基礎を築いた」とし、「『意識研究コミュニティ』 によって受け入れられている現代の意識の哲学的概念は支離滅裂である」と主張した[5]: 13-15 |

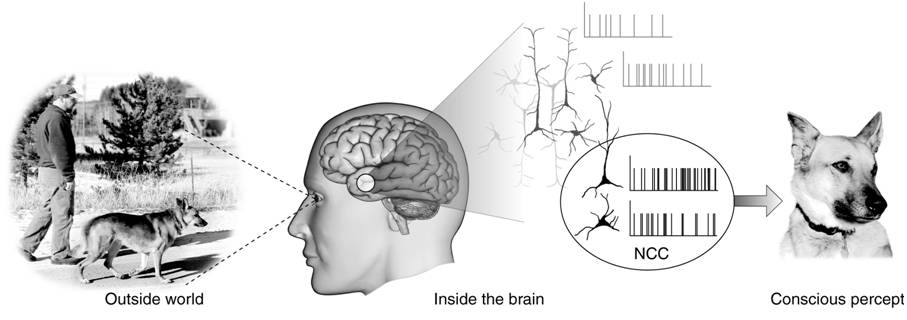

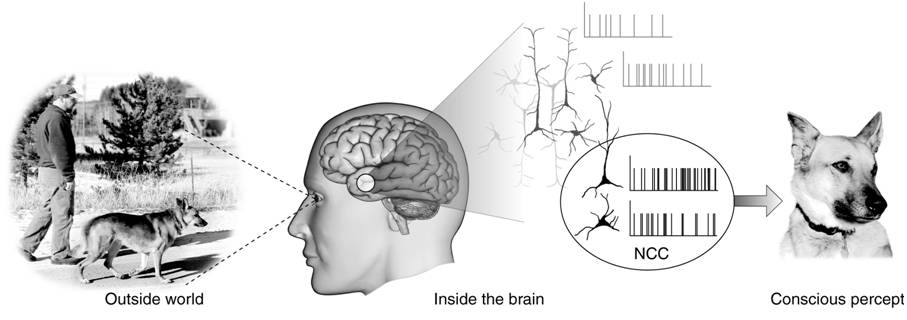

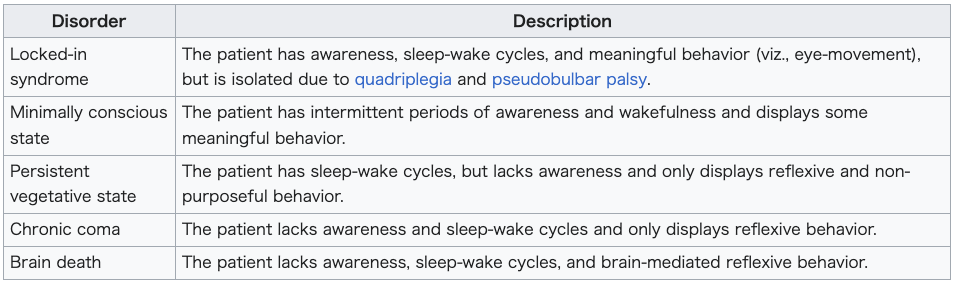

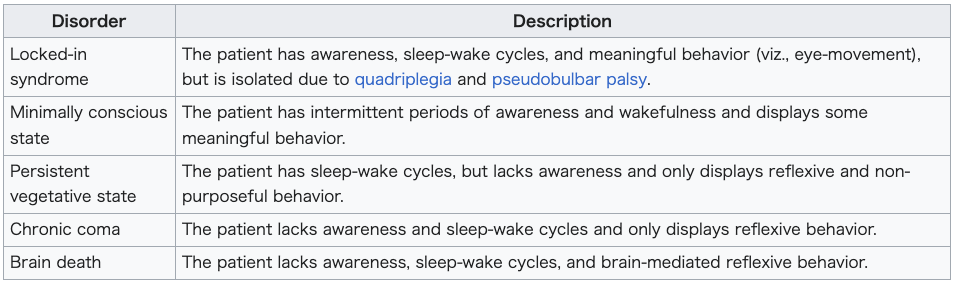

| Influence on research Many philosophers have argued that consciousness is a unitary concept that is understood by the majority of people despite the difficulty philosophers have had defining it.[33] The term 'subjective experience', following Nagel, is amibiguous, as philosophers seem to differ from non-philosophers in their intuitions about its meaning.[34] Max Velmans proposed that the "everyday understanding of consciousness" uncontroversially "refers to experience itself rather than any particular thing that we observe or experience" and he added that consciousness "is [therefore] exemplified by all the things that we observe or experience",[35]: 4 whether thoughts, feelings, or perceptions. Velmans noted however, as of 2009, that there was a deep level of "confusion and internal division"[35] among experts about the phenomenon of consciousness, because researchers lacked "a sufficiently well-specified use of the term...to agree that they are investigating the same thing".[35]: 3 He argued additionally that "pre-existing theoretical commitments" to competing explanations of consciousness might be a source of bias. Within the "modern consciousness studies" community the technical phrase 'phenomenal consciousness' is a common synonym for all forms of awareness, or simply 'experience',[35]: 4 without differentiating between inner and outer, or between higher and lower types. With advances in brain research, "the presence or absence of experienced phenomena"[35]: 3 of any kind underlies the work of those neuroscientists who seek "to analyze the precise relation of conscious phenomenology to its associated information processing" in the brain.[35]: 10 This neuroscientific goal is to find the "neural correlates of consciousness" (NCC). One criticism of this goal is that it begins with a theoretical commitment to the neurological origin of all "experienced phenomena" whether inner or outer.[c] Also, the fact that the easiest 'content of consciousness' to be so analyzed is "the experienced three-dimensional world (the phenomenal world) beyond the body surface"[35]: 4 invites another criticism, that most consciousness research since the 1990s, perhaps because of bias, has focused on processes of external perception.[37] From a history of psychology perspective, Julian Jaynes rejected popular but "superficial views of consciousness"[2]: 447 especially those which equate it with "that vaguest of terms, experience".[24]: 8 In 1976 he insisted that if not for introspection, which for decades had been ignored or taken for granted rather than explained, there could be no "conception of what consciousness is"[24]: 18 and in 1990, he reaffirmed the traditional idea of the phenomenon called 'consciousness', writing that "its denotative definition is, as it was for René Descartes, John Locke, and David Hume, what is introspectable".[2]: 450 Jaynes saw consciousness as an important but small part of human mentality, and he asserted: "there can be no progress in the science of consciousness until ... what is introspectable [is] sharply distinguished"[2]: 447 from the unconscious processes of cognition such as perception, reactive awareness and attention, and automatic forms of learning, problem-solving, and decision-making.[24]: 21-47 The cognitive science point of view—with an inter-disciplinary perspective involving fields such as psychology, linguistics and anthropology[38]—requires no agreed definition of "consciousness" but studies the interaction of many processes besides perception. For some researchers, consciousness is linked to some kind of "selfhood", for example to certain pragmatic issues such as the feeling of agency and the effects of regret[37] and action on experience of one's own body or social identity.[39] Similarly Daniel Kahneman, who focused on systematic errors in perception, memory and decision-making, has differentiated between two kinds of mental processes, or cognitive "systems":[40] the "fast" activities that are primary, automatic and "cannot be turned off",[40]: 22 and the "slow", deliberate, effortful activities of a secondary system "often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration".[40]: 13 Kahneman's two systems have been described as "roughly corresponding to unconscious and conscious processes".[41]: 8 The two systems can interact, for example in sharing the control of attention.[40]: 22 While System 1 can be impulsive, "System 2 is in charge of self-control",[40]: 26 and "When we think of ourselves, we identify with System 2, the conscious, reasoning self that has beliefs, makes choices, and decides what to think about and what to do".[40]: 21 Some have argued that we should eliminate the concept from our understanding of the mind, a position known as consciousness semanticism.[42] In medicine, a "level of consciousness" terminology is used to describe a patient's arousal and responsiveness, which can be seen as a continuum of states ranging from full alertness and comprehension, through disorientation, delirium, loss of meaningful communication, and finally loss of movement in response to painful stimuli.[43] Issues of practical concern include how the level of consciousness can be assessed in severely ill, comatose, or anesthetized people, and how to treat conditions in which consciousness is impaired or disrupted.[44] The degree or level of consciousness is measured by standardized behavior observation scales such as the Glasgow Coma Scale. |

研究への影響 ネーゲルに倣って「主観的経験」という用語はあいまいであり、哲学者はその意味についての直感において哲学者でない人々と異なるようである。 [34]マックス・ヴェルマンスは、「意識の日常的な理解」は議論の余地なく「私たちが観察したり経験したりする特定の事柄ではなく、経験そのものを指し ている」と提唱し、意識は「したがって、私たちが観察したり経験したりするすべての事柄によって例証される」と付け加えた[35]: 4 思考であれ、感情であれ、知覚であれ、である。しかしヴェルマンスは、2009年の時点で、研究者が「同じことを調査しているということに同意するため に...この用語を十分に特定した使い方」を欠いているため、意識の現象について専門家の間に深いレベルの「混乱と内部分裂」[35]があると指摘してい た[35]: 3 彼はさらに、意識の競合する説明に対する「既存の理論的コミットメント」がバイアスの原因かもしれないと主張した。 「現代意識研究」のコミュニティでは、「現象的意識」という専門的な言い回しは、あらゆる形態の意識、あるいは単に「経験」に対する一般的な同義語である [35]: 内的なものと外的なもの、あるいは高次のものと低次のものを区別することなくである。脳研究の進歩により、「経験された現象の有無」 [35]: 3 が、脳における「意識的現象論とそれに関連する情報処理との正確な関係を分析」しようとする神経科学者の研究の根底にある: 10 この神経科学的目標は「意識の神経相関」(NCC)を見つけることである。この目標に対する一つの批判は、それが内面であれ外面であれ、すべての「経験さ れた現象」の神経学的起源に対する理論的コミットメントから始まっていることである[c]。また、そのように分析される最も容易な「意識の内容」が「身体 表面を超えた経験された三次元世界(現象世界)」であるという事実である[35]: 4は、1990年代以降の意識研究のほとんどが、おそらく偏りのため に、外的知覚のプロセスに焦点を当てているという別の批判を招いている[37]。 心理学史の観点から、ジュリアン・ジェインズは一般的だが「表面的な意識観」[2]を否定した: 1976 年、彼は、何十年もの間、説明されるよりもむしろ無視されるか当然視されてきた内観がなければ、「意識とは何かについての概念」[24] はあり得ないと主張した: 18、1990年には「意識」と呼ばれる現象についての伝統的な考え方を再確認し、「その意味上の定義は、ルネ・デカルト、 ジョン・ロック、デイヴィッド・ヒュームにとってそうであったように、内観可能なものである」と書いている[2]: 450ジェインズは意識を人間の精神 性の重要だが小さな部分とみなし、こう主張した: 「意識の科学においては、......内観可能なものが[鋭く]区別されるまでは、進歩はありえない」[2]: 447 を、知覚、反応的な意識と注意、自動的な学習、問題解決、意思決定といった認知の無意識的な過程から区別することができない」[24]: 21-47 と主張した。 認知科学の視点-心理学、言語学、人類学[38]などの分野を含む学際的な視点-は、「意識」の合意された定義を必要としないが、知覚以外の多くのプロセ スの相互作用を研究している。一部の研究者にとっては、意識はある種の「自己性」、例えば主体性の感覚や後悔[37]の影響、自分自身の身体や社会的アイ デンティティの経験に対する行動といったある種のプラグマティックな問題と結びついている。 [39] 同様に、知覚、記憶、意思決定における系統的な誤りに 焦点を当てたダニエル・カーネマンは、2種類の心的プロセス、ま たは認知の「システム」を区別している:[40] 一次的で自動的で「オフにできない」「速い」活動[40]: 22 と、「しばしば主体性、選択、集中の主観的経験と関連する」二次的なシ ステムの「遅い」、意図的で努力的な活動[40]: 13 カーネマンの2つのシステムは「無意識と意識のプロセスにほぼ 対応する」と説明されている[41]: 8 2つのシステムは相互作用することができ、例えば注意の制御を共 有することができる[40]: 22 システム1は衝動的になることがあるが、「システム2は自制を 担当している」[40]: 26 そして「自分自身について考えるとき、私たちはシステム 2、すなわち信念を持ち、選択を行い、何について考え、 何をすべきかを決定する意識的で推論的な自己と同一化する」[40]: 21。 意識の意味論として知られる立場から、心の理解からこの概念を消去す べきだと主張する人もいる[42]。 医学においては、患者の覚醒と反応性を表すために「意識レベル」という用語が使用されており、これは、完全な覚醒と理解から、見当識障害、せん妄、意味の あるコミュニケーションの喪失、そして最終的には苦痛を伴う刺激に反応して動かなくなるまでの連続した状態として捉えることができる。 [43] 実践的な問題としては、重症患者、昏睡患者、麻酔患者において意識レベルをどのように評価するか、また、意識が損なわれている、または中断されている状態 をどのように治療するかがある。 |

| Philosophy of mind While historically philosophers have defended various views on consciousness, surveys indicate that physicalism is now the dominant position among contemporary philosophers of mind.[45] For an overview of the field, approaches often include both historical perspectives (e.g., Descartes, Locke, Kant) and organization by key issues in contemporary debates. An alternative is to focus primarily on current philosophical stances and empirical findings. Coherence of the concept Philosophers differ from non-philosophers in their intuitions about what consciousness is.[46] While most people have a strong intuition for the existence of what they refer to as consciousness,[33] skeptics argue that this intuition is too narrow, either because the concept of consciousness is embedded in our intuitions, or because we all are illusions. Gilbert Ryle, for example, argued that traditional understanding of consciousness depends on a Cartesian dualist outlook that improperly distinguishes between mind and body, or between mind and world. He proposed that we speak not of minds, bodies, and the world, but of entities, or identities, acting in the world. Thus, by speaking of "consciousness" we end up leading ourselves by thinking that there is any sort of thing as consciousness separated from behavioral and linguistic understandings.[47] |

心の哲学 歴史的に哲学者たちは意識に関する様々な見解を擁護してきたが、調査によれば、現代の心の哲学者の間では物理主義が支配的な立場となっている[45]。また、現在の哲学的スタンスや経験的知見に焦点を当てる方法もある。 概念の一貫性 哲学者は、意識が何であるかについての直観において非哲学者と異なる[46]。ほとんどの人が意識と呼ばれるものの存在について強い直観を持っている一方 で[33]、懐疑論者は、意識の概念が私たちの直観に埋め込まれているためか、あるいは私たちは皆幻想であるためか、この直観は狭すぎると主張している。 例えばギルバート・ライルは、伝統的な意識の理解は、心と身体、あるいは心と世界を不適切に区別するデカルト主義的な二元論に依存していると主張した。彼 は、私たちは心、身体、世界について語るのではなく、世界で作用する実体、つまりアイデンティティーについて語るのだと提唱した。したがって、「意識」に ついて語ることで、私たちは行動や言語的理解から切り離された意識というものが存在すると考えることで、自らを導いてしまうことになる[47]。 |

| Types Ned Block argues that discussions on consciousness have often failed properly to distinguish phenomenal consciousness from access consciousness. The terms had been used before Block used them, but he adopted the short forms P-consciousness and A-consciousness.[48] According to Block: P-consciousness is raw experience: it is moving, colored forms, sounds, sensations, emotions and feelings with our bodies and responses at the center. These experiences, considered independently of any impact on behavior, are called qualia. A-consciousness is the phenomenon whereby information in our minds is accessible for verbal report, reasoning, and the control of behavior. So, when we perceive, information about what we perceive is access conscious; when we introspect, information about our thoughts is access conscious; when we remember, information about the past is access conscious, and so on. Block adds that P-consciousness does not allow of easy definition: he admits that he "cannot define P-consciousness in any remotely noncircular way.[48] Although some philosophers, such as Daniel Dennett, have disputed the validity of this distinction,[49] others have broadly accepted it. David Chalmers has argued that A-consciousness can in principle be understood in mechanistic terms, but that understanding P-consciousness is much more challenging: he calls this the hard problem of consciousness.[50] Some philosophers believe that Block's two types of consciousness are not the end of the story. William Lycan, for example, argued in his book Consciousness and Experience that at least eight clearly distinct types of consciousness can be identified (organism consciousness; control consciousness; consciousness of; state/event consciousness; reportability; introspective consciousness; subjective consciousness; self-consciousness)—and that even this list omits several more obscure forms.[51] There is also debate over whether or not A-consciousness and P-consciousness always coexist or if they can exist separately. Although P-consciousness without A-consciousness is more widely accepted, there have been some hypothetical examples of A without P. Block, for instance, suggests the case of a "zombie" that is computationally identical to a person but without any subjectivity. However, he remains somewhat skeptical concluding "I don't know whether there are any actual cases of A-consciousness without P-consciousness, but I hope I have illustrated their conceptual possibility".[52] |

タイプ ネッド・ブロックは、意識に関する議論はしばしば現象意識とアクセス意識を適切に区別できていないと主張している。これらの用語はブロックが使用する以前から使われていたが、ブロックはP意識とA意識という短い形を採用した[48]: P-意識は生の経験であり、私たちの身体と反応を中心とした、動くもの、色のついた形、音、感覚、感情、情動である。これらの経験は行動への影響とは無関係に考えられ、クオリアと呼ばれる。 A意識とは、私たちの心の中にある情報が、言葉による報告、推論、行動のコントロールのためにアクセスできる現象である。つまり、私たちが知覚するとき、 知覚したものについての情報がアクセス意識され、内省するとき、自分の考えについての情報がアクセス意識され、記憶するとき、過去についての情報がアクセ ス意識される、といった具合である。 ブロックは、P-consciousnessは簡単には定義できないと付け加えている。彼は「P-consciousnessを少しでも非円形的な方法で定義することはできない」と認めている[48]。 ダニエル・デネットのようにこの区別の妥当性に異議を唱える哲学者もいるが[49]、広く受け入れている哲学者もいる。デイヴィッド・チャルマーズはA意 識は原理的には機械論的な用語で理解することができるが、P意識を理解することはより困難であると主張しており、彼はこれを意識の難問と呼んでいる [50]。 哲学者の中には、ブロックが提唱した意識の2つのタイプで話が終わるわけではないと考える者もいる。例えば、ウィリアム・ライカンはその著書 『Consciousness and Experience(意識と経験)』において、少なくとも8つの明確に区別されるタイプの意識(有機体意識、制御意識、意識、状態/事象意識、報告可能 性、内省的意識、主観的意識、自己意識)を特定することが可能であり、このリストにはさらにいくつかの不明瞭な形態が省かれていると主張している [51]。 また、A-意識とP-意識が常に共存するのか、それとも別々に存在することができるのかという議論もある。A意識のないP意識はより広く受け入れられてい るが、P意識のないAという仮説的な例もある。例えば、ブロックは、計算上は人格と同じだが主観性のない「ゾンビ」のケースを提案している。しかし、彼は 「P意識のないA意識の事例が実際にあるかどうかはわからないが、概念的な可能性は説明できたと思う」と結論付けており、やや懐疑的である[52]。 |

| Distinguishing consciousness from its contents Sam Harris observes: "At the level of your experience, you are not a body of cells, organelles, and atoms; you are consciousness and its ever-changing contents".[53] Seen in this way, consciousness is a subjectively experienced, ever-present field in which things (the contents of consciousness) come and go. Christopher Tricker argues that this field of consciousness is symbolized by the mythical bird that opens the Daoist classic the Zhuangzi. This bird's name is Of a Flock (peng 鵬), yet its back is countless thousands of miles across and its wings are like clouds arcing across the heavens. "Like Of a Flock, whose wings arc across the heavens, the wings of your consciousness span to the horizon. At the same time, the wings of every other being's consciousness span to the horizon. You are of a flock, one bird among kin."[54] |

意識とその内容を区別する サム・ハリスはこう言う: 「あなたの経験のレベルでは、あなたは細胞、細胞小器官、原子からなる身体ではなく、意識とその変化し続ける内容物なのだ」[53]。このように考える と、意識は主観的に経験される、常に存在する場であり、その中で物事(意識の内容物)が行き交う。 クリストファー・トリッカーは、この意識の場は道教の古典『荘子』の冒頭に登場する神話的な鳥によって象徴されていると主張する。この鳥の名前は鵬(Of a Flock)であるが、その背は数千マイルに及び、その翼は天を弧を描く雲のようである。「翼が弧を描いて天を渡る群れのように、あなたの意識の翼は地平 線まで広がっている。同時に、他のすべての存在の意識の翼も地平線まで伸びている。あなたは群れの一員であり、親族の中の一羽の鳥である」[54]。 |

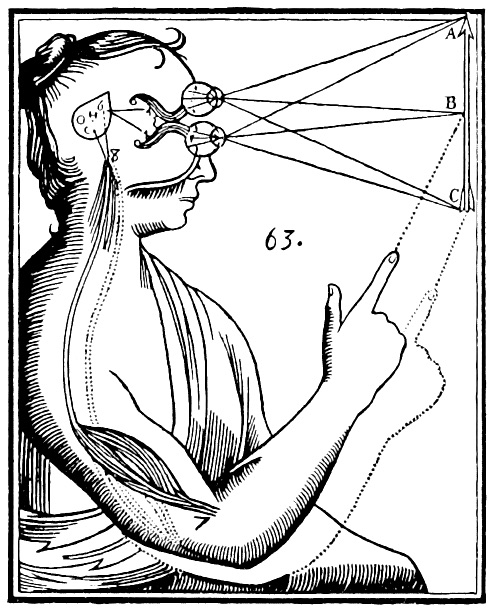

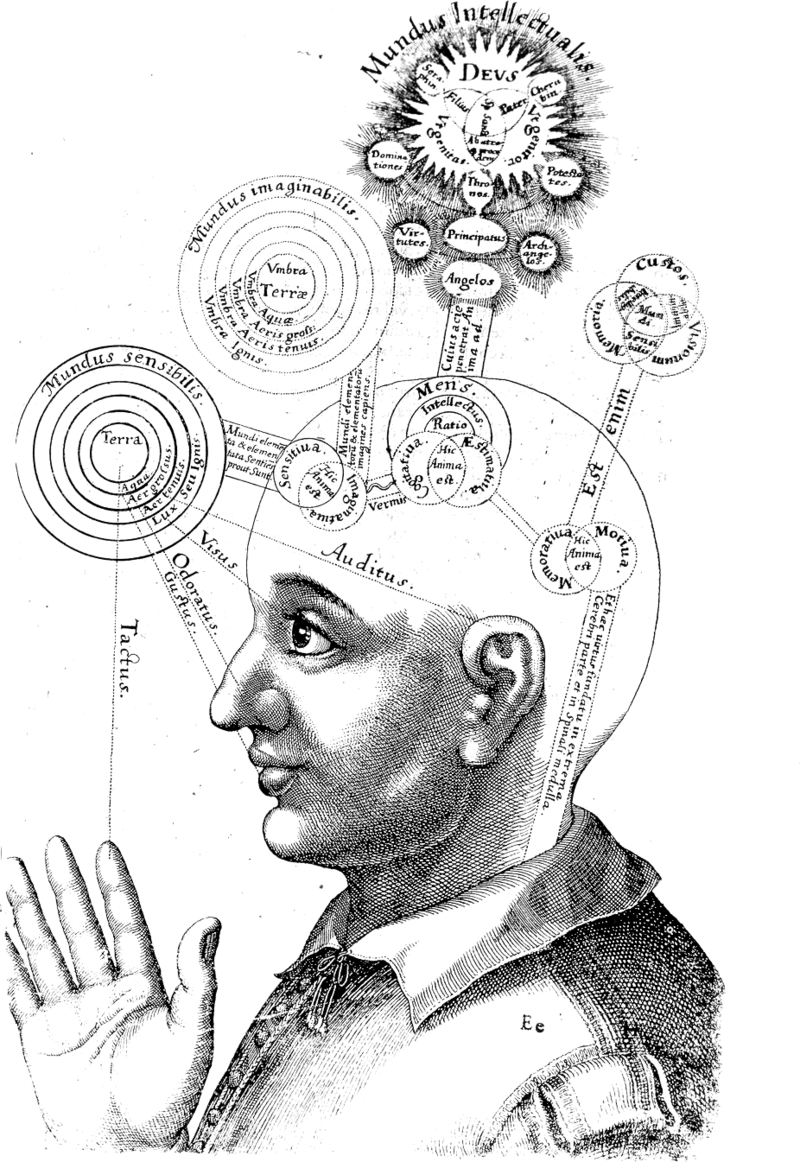

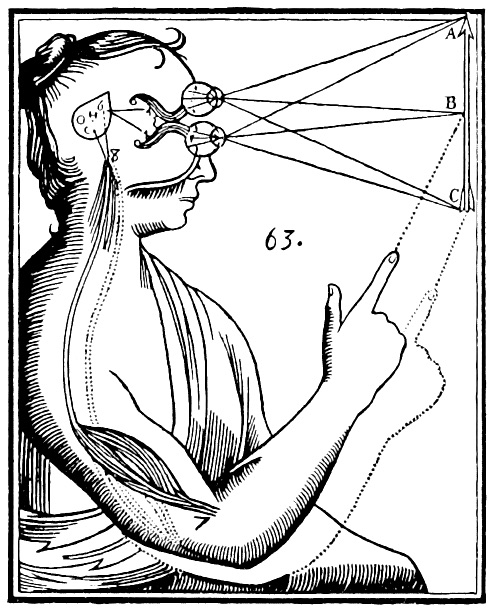

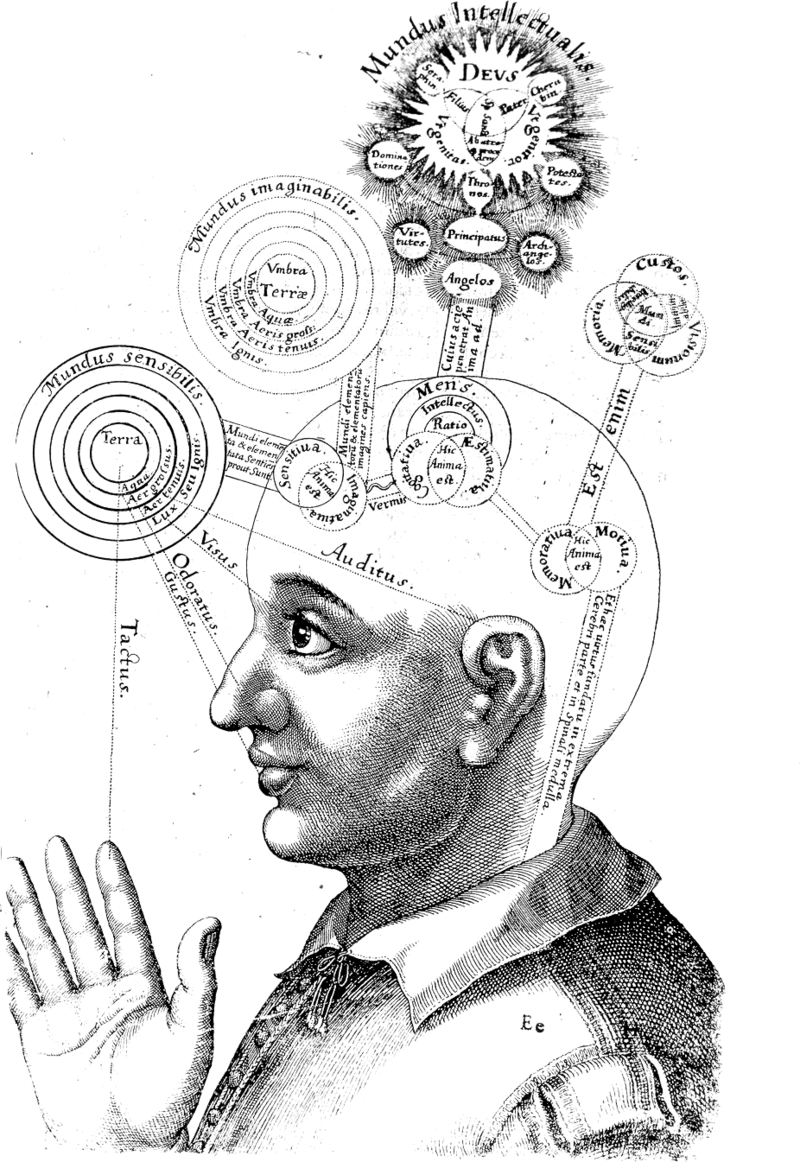

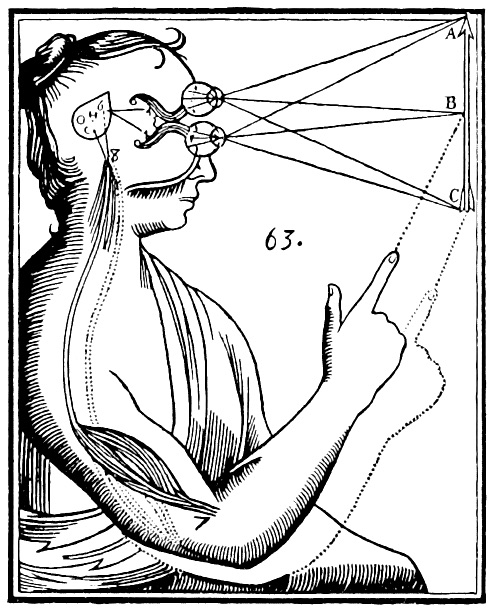

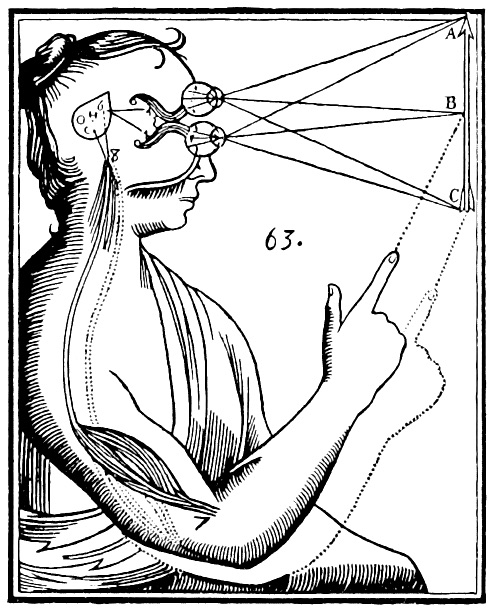

| Mind–body problem Main article: Mind–body problem  Illustration of mind–body dualism by René Descartes. Inputs are passed by the sensory organs to the pineal gland, and from there to the immaterial spirit. Mental processes (such as consciousness) and physical processes (such as brain events) seem to be correlated, however the specific nature of the connection is unknown. The first influential philosopher to discuss this question specifically was Descartes, and the answer he gave is known as mind–body dualism. Descartes proposed that consciousness resides within an immaterial domain he called res cogitans (the realm of thought), in contrast to the domain of material things, which he called res extensa (the realm of extension).[55] He suggested that the interaction between these two domains occurs inside the brain, perhaps in a small midline structure called the pineal gland.[56] Although it is widely accepted that Descartes explained the problem cogently, few later philosophers have been happy with his solution, and his ideas about the pineal gland have especially been ridiculed.[56] However, no alternative solution has gained general acceptance. Proposed solutions can be divided broadly into two categories: dualist solutions that maintain Descartes's rigid distinction between the realm of consciousness and the realm of matter but give different answers for how the two realms relate to each other; and monist solutions that maintain that there is really only one realm of being, of which consciousness and matter are both aspects. Each of these categories itself contains numerous variants. The two main types of dualism are substance dualism (which holds that the mind is formed of a distinct type of substance not governed by the laws of physics), and property dualism (which holds that the laws of physics are universally valid but cannot be used to explain the mind). The three main types of monism are physicalism (which holds that the mind is made out of matter), idealism (which holds that only thought or experience truly exists, and matter is merely an illusion), and neutral monism (which holds that both mind and matter are aspects of a distinct essence that is itself identical to neither of them). There are also, however, a large number of idiosyncratic theories that cannot cleanly be assigned to any of these schools of thought.[57] Since the dawn of Newtonian science with its vision of simple mechanical principles governing the entire universe, some philosophers have been tempted by the idea that consciousness could be explained in purely physical terms. The first influential writer to propose such an idea explicitly was Julien Offray de La Mettrie, in his book Man a Machine (L'homme machine). His arguments, however, were very abstract.[58] The most influential modern physical theories of consciousness are based on psychology and neuroscience. Theories proposed by neuroscientists such as Gerald Edelman[59] and Antonio Damasio,[60] and by philosophers such as Daniel Dennett,[61] seek to explain consciousness in terms of neural events occurring within the brain. Many other neuroscientists, such as Christof Koch,[62] have explored the neural basis of consciousness without attempting to frame all-encompassing global theories. At the same time, computer scientists working in the field of artificial intelligence have pursued the goal of creating digital computer programs that can simulate or embody consciousness.[63] A few theoretical physicists have argued that classical physics is intrinsically incapable of explaining the holistic aspects of consciousness, but that quantum theory may provide the missing ingredients. Several theorists have therefore proposed quantum mind (QM) theories of consciousness.[64] Notable theories falling into this category include the holonomic brain theory of Karl Pribram and David Bohm, and the Orch-OR theory formulated by Stuart Hameroff and Roger Penrose. Some of these QM theories offer descriptions of phenomenal consciousness, as well as QM interpretations of access consciousness. None of the quantum mechanical theories have been confirmed by experiment. Recent publications by G. Guerreshi, J. Cia, S. Popescu, and H. Briegel[65] could falsify proposals such as those of Hameroff, which rely on quantum entanglement in protein. At the present time many scientists and philosophers consider the arguments for an important role of quantum phenomena to be unconvincing.[66] Empirical evidence is against the notion of quantum consciousness, an experiment about wave function collapse led by Catalina Curceanu in 2022 suggests that quantum consciousness, as suggested by Roger Penrose and Stuart Hameroff, is highly implausible.[67] Apart from the general question of the "hard problem" of consciousness (which is, roughly speaking, the question of how mental experience can arise from a physical basis[68]), a more specialized question is how to square the subjective notion that we are in control of our decisions (at least in some small measure) with the customary view of causality that subsequent events are caused by prior events. The topic of free will is the philosophical and scientific examination of this conundrum. |

心と体の問題 主な記事 心身問題  ルネ・デカルトによる心身二元論の図解。入力は感覚器官から松果体に伝えられ、そこから非物質的な精神に至る。 精神的プロセス(意識など)と物理的プロセス(脳内事象など)には相関関係があるように見えるが、その具体的な性質は不明である。 この疑問を具体的に論じた最初の影響力のある哲学者はデカルトであり、彼の出した答えは心身二元論として知られている。デカルトは、意識がres cogitans(思考の領域)と呼ばれる非物質的な領域内に存在し、res extensa(伸張の領域)と呼ばれる物質的なものの領域とは対照的であると提唱した[55]。この2つの領域間の相互作用は脳の内部、おそらく松果体 と呼ばれる正中線の小さな構造で起こると示唆した[56]。 デカルトがこの問題を理路整然と説明したことは広く受け入れられているが、彼の解決策に満足した後世の哲学者はほとんどおらず、特に松果体に関する彼の考 えは嘲笑されている[56]。すなわち、意識の領域と物質の領域との間のデカルトの厳格な区別は維持するが、2つの領域が互いにどのように関係するかにつ いては異なる答えを与える二元論的な解決策と、意識と物質が両方の側面である存在の領域は実際には1つしかないとする一元論的な解決策である。これらのカ テゴリーはそれぞれ、数多くの変種を含んでいる。二元論の2つの主要なタイプは、物質二元論(心は物理法則に支配されない別個のタイプの物質で形成されて いるとする)と性質二元論(物理法則は普遍的に有効であるが、心を説明するのに用いることはできないとする)である。一元論の3つの主要なタイプは、物理 主義(心は物質からできているとする)、観念論(思考または経験のみが真に存在し、物質は幻想に過ぎないとする)、中立的一元論(心と物質の両方が、その どちらとも同一でない別個の本質の側面であるとする)である。しかしながら、これらの学派のいずれにもきれいに割り当てることができない特異な理論も数多 く存在する[57]。 宇宙全体を支配する単純な機械的原理のビジョンを持つニュートン科学の黎明期以来、一部の哲学者は意識が純粋に物理的な用語で説明できるという考えに誘惑 されてきた。そのような考えを明確に提唱した最初の影響力のある作家は、ジュリアン・オフレイ・ド・ラ・メトリ(Julien Offray de La Mettrie)であり、彼の著書『機械としての人間(L'homme machine)』の中に登場する。しかし、彼の議論は非常に抽象的であった[58]。意識に関する最も影響力のある現代の物理学理論は、心理学と神経科 学に基づいている。ジェラルド・エデルマン[59]やアントニオ・ダマシオ[60]などの神経科学者や、ダニエル・デネット[61]などの哲学者によって 提唱された理論は、脳内で起こる神経事象の観点から意識を説明しようとするものである。クリストフ・コッホ[62]のような他の多くの神経科学者は、包括 的なグローバル理論を構築しようとすることなく、意識の神経基盤を探求してきた。同時に、人工知能の分野で働くコンピュータ科学者たちは、意識をシミュ レートしたり具現化したりできるデジタル・コンピュータ・プログラムを作成するという目標を追求してきた[63]。 少数の理論物理学者は、古典物理学は本質的に意識の全体論的側面を説明できないが、量子論は欠けている要素を提供できるかもしれないと主張している。この カテゴリーに分類される著名な理論には、カール・プリブラムとデイヴィッド・ボームのホロノミック脳理論や、スチュアート・ハメロフとロジャー・ペンロー ズが提唱したOrch-OR理論などがある。これらの量子力学理論の中には、現象的意識の記述やアクセス意識の量子力学的解釈を提供するものもある。どの 量子力学理論も実験によって確認されていない。G. Guerreshi、J. Cia、S. Popescu、H. Briegelによる最近の発表[65]は、タンパク質の量子もつれに依存するハメロフの提案などを反証する可能性がある。現在、多くの科学者や哲学者 は、量子現象が重要な役割を果たすという主張は説得力がないと考えている[66]。2022年にカタリナ・クルセアヌが主導した波動関数の崩壊に関する実 験は、ロジャー・ペンローズやスチュアート・ハメロフが示唆した量子意識は非常にあり得ないことを示唆している[67]。 意識の「難問」(大雑把に言えば、精神的経験が物理的基盤からどのように生じ得るかという問題[68])という一般的な問題とは別に、より専門的な問題 は、私たちは自分の決定を(少なくともいくらかは)制御しているという主観的な概念と、後続の事象は先行する事象によって引き起こされるという慣習的な因 果観とをどのように折り合わせるかということである。自由意志というテーマは、この難問を哲学的・科学的に検討するものである。 |

| Problem of other minds Main article: Problem of other minds Many philosophers consider experience to be the essence of consciousness, and believe that experience can only fully be known from the inside, subjectively. The problem of other minds is a philosophical problem traditionally stated as the following epistemological question: Given that I can only observe the behavior of others, how can I know that others have minds?[69] The problem of other minds is particularly acute for people who believe in the possibility of philosophical zombies, that is, people who think it is possible in principle to have an entity that is physically indistinguishable from a human being and behaves like a human being in every way but nevertheless lacks consciousness.[70] Related issues have also been studied extensively by Greg Littmann of the University of Illinois,[71] and by Colin Allen (a professor at the University of Pittsburgh) regarding the literature and research studying artificial intelligence in androids.[72] The most commonly given answer is that we attribute consciousness to other people because we see that they resemble us in appearance and behavior; we reason that if they look like us and act like us, they must be like us in other ways, including having experiences of the sort that we do.[73] There are, however, a variety of problems with that explanation. For one thing, it seems to violate the principle of parsimony, by postulating an invisible entity that is not necessary to explain what we observe.[73] Some philosophers, such as Daniel Dennett in a research paper titled "The Unimagined Preposterousness of Zombies", argue that people who give this explanation do not really understand what they are saying.[74] More broadly, philosophers who do not accept the possibility of zombies generally believe that consciousness is reflected in behavior (including verbal behavior), and that we attribute consciousness on the basis of behavior. A more straightforward way of saying this is that we attribute experiences to people because of what they can do, including the fact that they can tell us about their experiences.[75] |

他者の心の問題 主な記事 他者の心の問題 多くの哲学者は、経験こそが意識の本質であると考え、経験は内面から主観的にしか知ることができないと信じている。他者の心の問題とは、伝統的に次のよう な認識論的疑問として語られる哲学的問題である: つまり、物理的には人間と区別がつかず、あらゆる点で人間のように振る舞うが、それにもかかわらず意識を持たない存在を持つことは原理的に可能であると考 える人々である。 [70] 関連する問題は、イリノイ大学のグレッグ・リットマンや[71]、アンドロイドの人工知能を研究する文献や研究に関してコリン・アレン(ピッツバーグ大学 教授)によっても幅広く研究されている[72]。 最も一般的に言われている答えは、私たちが他者に意識を帰属させるのは、他者の外見や行動が私たちに似ているからだとするものである。私たちは、他者の外 見や行動が私たちに似ているのであれば、私たちと同じような経験をしているなど、他の点でも私たちに似ているに違いないと推論する。73]。「ゾンビの想 像を絶する荒唐無稽さ」と題された研究論文に登場するダニエル・デネットのような哲学者の中には、このような説明をする人は自分たちが言っていることを本 当に理解していないと主張する人もいる。 [より広義には、ゾンビの可能性を認めない哲学者は、一般的に、意識は行動(言語的行動を含む)に反映され、我々は行動に基づいて意識を帰属させると信じ ている。より端的な言い方をすれば、人が自分の経験について語ることができるという事実を含め、人が何をすることができるからこそ、私たちは人に経験を帰 属させるということである[75]。 |

| Qualia Main article: qualia The term "qualia" was introduced in philosophical literature by C. I. Lewis. The word is derived from Latin and means "of what sort". It is basically a quantity or property of something as perceived or experienced by an individual, like the scent of rose, the taste of wine, or the pain of a headache. They are difficult to articulate or describe. The philosopher and scientist Daniel Dennett describes them as "the way things seem to us", while philosopher and cognitive scientist David Chalmers expanded on qualia as the "hard problem of consciousness" in the 1990s. When qualia is experienced, activity is simulated in the brain, and these processes are called neural correlates of consciousness (NCCs). Many scientific studies have been done to attempt to link particular brain regions with emotions or experiences.[76][77][78] Species which experience qualia are said to have sentience, which is central to the animal rights movement, because it includes the ability to experience pain and suffering.[76] |

クオリア 主な記事:クオリア クオリア」という言葉は、C.I.ルイスによって哲学文献に紹介された。語源はラテン語で「どのような」という意味である。基本的には、バラの香り、ワイ ンの味、頭痛の痛みのように、個人が知覚・経験する何かの量や性質のことである。これらを明確に表現したり、説明したりするのは難しい。哲学者であり科学 者でもあるダニエル・デネットは、クオリアを「物事の見え方」と表現し、哲学者であり認知科学者でもあるデイヴィッド・チャルマーズは、1990年代にク オリアを「意識の難しい問題」として拡張した。クオリアが経験されると、脳内で活動がシミュレートされ、これらのプロセスは意識の神経相関(NCC)と呼 ばれる。特定の脳領域と感情や経験を結びつけることを試みる多くの科学的研究が行われてきた[76][77][78]。 クオリアを経験する生物種は感覚を持つと言われているが、これは痛みや苦しみを経験する能力を含むため、動物愛護運動の中心的存在となっている[76]。 |

| Identity Main article: Personal identity An unsolved problem in the philosophy of consciousness is how it relates to the nature of personal identity.[79] This includes questions regarding whether someone is the "same person" from moment to moment. If that is the case, another question is what exactly the "identity carrier" is that makes a conscious being "the same" being from one moment to the next. The problem of determining personal identity also includes questions such as Benj Hellie's vertiginous question, which can be summarized as "Why am I me and not someone else?".[80] The philosophical problems regarding the nature of personal identity have been extensively discussed by Thomas Nagel in his book The View from Nowhere. A common view of personal identity is that an individual has a continuous identity that persists from moment to moment, with an individual having a continuous identity consisting of a line segment stretching across time from birth to death. In the case of an afterlife as described in Abrahamic religions, one's personal identity is believed to stretch infinitely into the future, forming a ray or line. This notion of identity is similar to the form of dualism advocated by René Descartes. However, some philosophers argue that this common notion of personal identity is unfounded. Daniel Kolak has argued extensively against it in his book I am You.[81] Kolak refers to the aforementioned notion of personal identity being linear as "Closed individualism". Another view of personal identity according to Kolak is "Empty individualism", in which one's personal identity only exists for a single moment of time. However, Kolak advocates for a view of personal identity called Open individualism, in which all consciousness is in reality a single being and individual personal identity in reality does not exist at all. Another philosopher who has contested the notion of personal identity is Derek Parfit. In his book Reasons and Persons,[82] he describes a thought experiment known as the teletransportation paradox. In Buddhist philosophy, the concept of anattā refers to the idea that the self is an illusion. Other philosophers have argued that Hellie's vertiginous question has a number of philosophical implications relating to the metaphysical nature of consciousness. Christian List argues that the vertiginous question and the existence of first-personal facts is evidence against physicalism, and evidence against other third-personal metaphysical pictures, including standard versions of dualism.[83] List also argues that the vertiginous question implies a "quadrilemma" for theories of consciousness. He claims that at most three of the following metaphysical claims can be true: 'first-person realism', 'non-solipsism', 'non-fragmentation', and 'one world' – and at at least one of these four must be false.[84] List has proposed a model he calls the "many-worlds theory of consciousness" in order to reconcile the subjective nature of consciousness without lapsing into solipsism.[85] Vincent Conitzer argues that the nature of identity is connected to A series and B series theories of time, and that A-theory being true implies that the "I" is metaphysically distinguished from other perspectives.[86] Giovanni Merlo has argued that the subjectivist view of mental phenomena goes a considerable way towards solving various long-standing philosophical puzzles related to various aspects of consciousness, such as the unity of consciousness, the contents of self-awareness, and the problems with transmitting information related to the contents of subjective experience.[87] Other philosophical theories regarding the metaphysical nature of self are Caspar Hare's theories of perspectival realism,[88] in which things within perceptual awareness have a defining intrinsic property that exists absolutely and not relative to anything, and egocentric presentism, in which the experiences of other individuals are not present in the way that one's current perspective is.[89][90] |

アイデンティティ 主な記事 人格の同一性 意識の哲学における未解決の問題は、それが個人のアイデンティティの本質とどのように関係しているかということである。もしそうであるならば、もう一つの 問題は、意識を持つ存在をある瞬間から次の瞬間まで「同じ」存在にする「同一性保持者」とは一体何なのかということである。個人のアイデンティティを決定 する問題には、「なぜ私は私であり、他の誰かではないのか」と要約できるベンジー・ヘリーのvertiginous questionのような問いも含まれる[80]。個人のアイデンティティの本質に関する哲学的問題は、トーマス・ネーゲルによってその著書『The View from Nowhere』の中で広範に論じられている。 個人の同一性についての一般的な見解は、個人は瞬間から瞬間まで持続する連続的な同一性を持っており、個人は誕生から死までの時間を横切って伸びる線分か らなる連続的な同一性を持っているというものである。アブラハムの宗教で説明されるような死後の世界の場合、人格のアイデンティティは未来に無限に伸び、 光線または線を形成すると信じられている。このアイデンティティーの概念は、ルネ・デカルトが唱えた二元論の形に似ている。しかし、この一般的な人格の概 念は根拠がないと主張する哲学者もいる。ダニエル・コラックは、著書『I am You』[81]の中で、この概念に対して広範に反論している。コラックは、個人のアイデンティティが直線的であるという前述の概念を「閉鎖的個人主義」 と呼んでいる。コラックによれば、個人のアイデンティティに関する別の見解は「空っぽの個人主義」であり、そこでは個人のアイデンティティは一瞬の間だけ 存在する。しかし、コラックは「開かれた個人主義」と呼ばれる人格観を提唱しており、そこでは、すべての意識は現実には単一の存在であり、現実には個人の 人格はまったく存在しないとしている。個人の同一性という概念に異議を唱えたもう一人の哲学者は、デレク・パーフィットである。彼は著書『Reasons and Persons』[82]の中で、テレトランスポーテーションのパラドックスとして知られる思考実験について述べている。仏教哲学では、自己は幻想である という考え方をアナターという概念で表している。 他の哲学者は、ヘリーの暈のような問いには、意識の形而上学的性質に関連する多くの哲学的含意があると主張している。クリスチャン・リスト (Christian List)は、垂直な問いと一人称的事実の存在は、物理主義に対する証拠であり、標準的な二元論を含む他の三人称的形而上学に対する証拠であると主張して いる。彼は次の形而上学的主張のうち、真である可能性があるのはせいぜい3つ、すなわち「一人称実在論」、「非ソリュプシス主義」、「非断片化」、「一つ の世界」であり、これら4つのうち少なくとも1つは偽でなければならないと主張している[84]。リストは、ソリュプシス主義に陥ることなく意識の主観的 性質を調和させるために、彼が「意識の多世界理論」と呼ぶモデルを提唱している。 [85] ヴィンセント・コニッツァーは、アイデンティティの性質は時間のA系列とB系列の理論と結びついており、A系列理論が真であるということは、「私」が他の 視点から形而上学的に区別されることを意味していると論じている。 [ジョヴァンニ・メルロは、心的現象に対する主観主義的見解は、意識の統一性、自己認識の内容、主観的経験の内容に関連する情報伝達の問題など、意識の様 々な側面に関連する様々な長年の哲学的パズルを解決する上でかなりの役割を果たすと主張している。 [87] 自己の形而上学的性質に関する他の哲学的理論には、知覚的認識の中にある事物は何に対しても相対的ではなく絶対的に存在する定義的な内在的特性を持つとい うキャスパー・ヘアの視点実在論の理論[88]や、他の個人の経験は自分の現在の視点がそうであるように存在しないという自己中心的現在論の理論がある [89][90]。 |

| Scientific study For many decades, consciousness as a research topic was avoided by the majority of mainstream scientists, because of a general feeling that a phenomenon defined in subjective terms could not properly be studied using objective experimental methods.[91] In 1975 George Mandler published an influential psychological study which distinguished between slow, serial, and limited conscious processes and fast, parallel and extensive unconscious ones.[92] The Science and Religion Forum[93] 1984 annual conference, 'From Artificial Intelligence to Human Consciousness' identified the nature of consciousness as a matter for investigation; Donald Michie was a keynote speaker. Starting in the 1980s, an expanding community of neuroscientists and psychologists have associated themselves with a field called Consciousness Studies, giving rise to a stream of experimental work published in books,[94] journals such as Consciousness and Cognition, Frontiers in Consciousness Research, Psyche, and the Journal of Consciousness Studies, along with regular conferences organized by groups such as the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness[95] and the Society for Consciousness Studies. Modern medical and psychological investigations into consciousness are based on psychological experiments (including, for example, the investigation of priming effects using subliminal stimuli),[96] and on case studies of alterations in consciousness produced by trauma, illness, or drugs. Broadly viewed, scientific approaches are based on two core concepts. The first identifies the content of consciousness with the experiences that are reported by human subjects; the second makes use of the concept of consciousness that has been developed by neurologists and other medical professionals who deal with patients whose behavior is impaired. In either case, the ultimate goals are to develop techniques for assessing consciousness objectively in humans as well as other animals, and to understand the neural and psychological mechanisms that underlie it.[62] |

科学的研究 何十年もの間、主観的な用語で定義された現象は客観的な実験方法を用いて適切に研究できないという一般的な感覚から、研究テーマとしての意識は主流派の科 学者の大多数によって避けられていた[91]。 1975年、ジョージ・マンドラーは影響力のある心理学的研究を発表し、遅い、直列的、限定的な意識プロセスと、速い、並列的、広範な無意識プロセスを区 別した[92]。 科学と宗教フォーラム[93]は1984年の年次会議「人工知能から人間の意識へ」で、意識の本質を調査すべき問題として特定し、ドナルド・ミッチーは基 調講演を行った。1980年代から、神経科学者や心理学者のコミュニティが拡大し、「意識研究」と呼ばれる分野と結びつき、「意識と認知」、「フロンティ アズ・イン・コンシャスネス・リサーチ」、「サイケ」、「ジャーナル・オブ・コンシャスネス・スタディーズ」といった書籍[94]や雑誌に発表される実験 的研究の流れが生まれ、「意識の科学的研究のための協会」[95]や「意識研究学会」といったグループが主催する定期的な会議が開催されるようになった。 意識に関する現代の医学的および心理学的研究は、心理学的実験(例えば、サブリミナル刺激を用いたプライミング効果の調査を含む)[96]、およびトラウ マ、病気、または薬物によって生じた意識の変化の事例研究に基づいている。大まかに見て、科学的アプローチは2つの中核概念に基づいている。もうひとつ は、神経科医や、行動に障害のある患者を扱う他の医療専門家によって開発された意識の概念を利用するものである。いずれにせよ、最終的な目標は、ヒトだけ でなく他の動物においても意識を客観的に評価する技術を開発し、その根底にある神経的・心理的メカニズムを理解することである[62]。 |

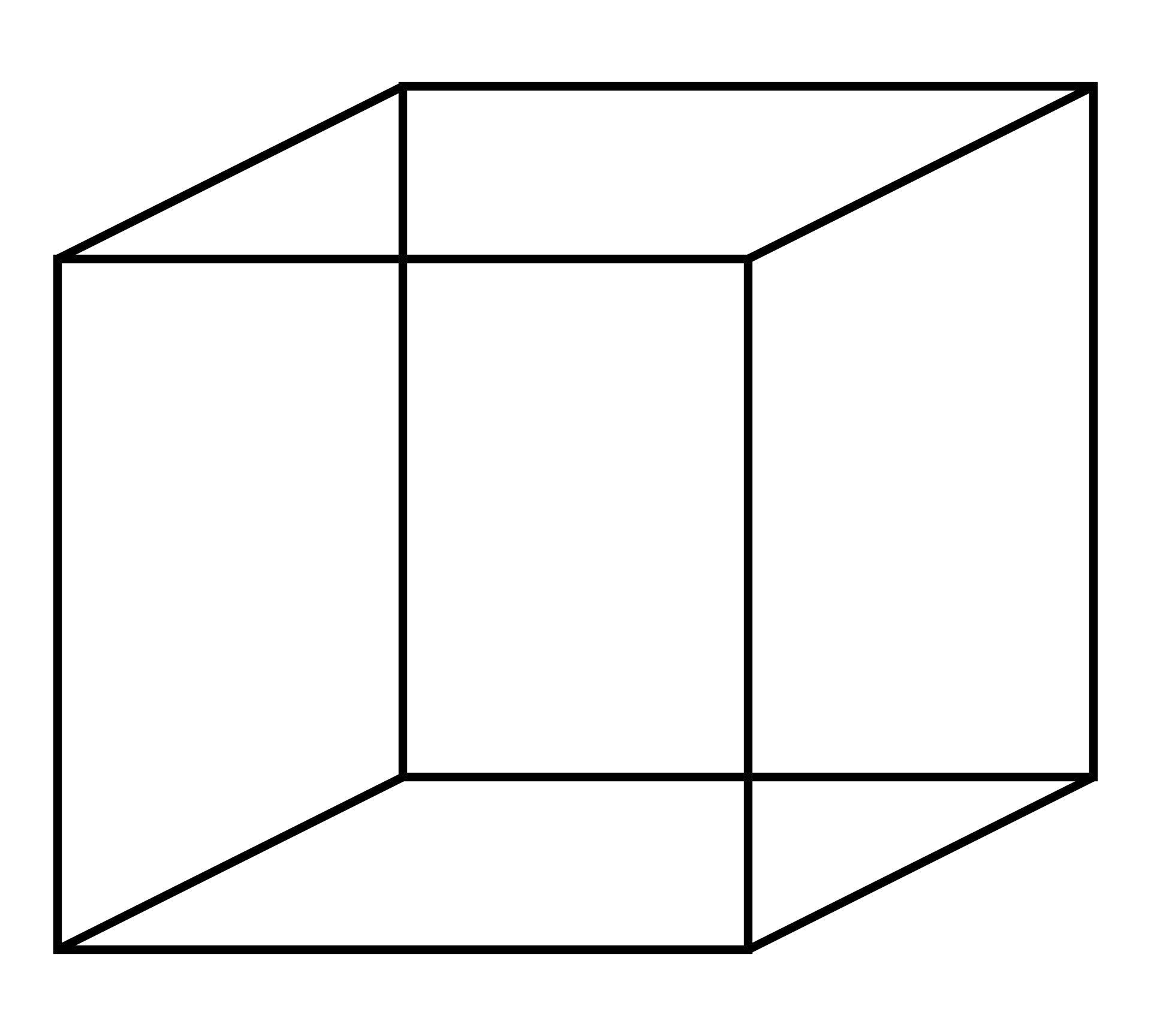

Measurement via verbal report The Necker cube, an ambiguous image Experimental research on consciousness presents special difficulties, due to the lack of a universally accepted operational definition. In the majority of experiments that are specifically about consciousness, the subjects are human, and the criterion used is verbal report: in other words, subjects are asked to describe their experiences, and their descriptions are treated as observations of the contents of consciousness.[97] For example, subjects who stare continuously at a Necker cube usually report that they experience it "flipping" between two 3D configurations, even though the stimulus itself remains the same.[98] The objective is to understand the relationship between the conscious awareness of stimuli (as indicated by verbal report) and the effects the stimuli have on brain activity and behavior. In several paradigms, such as the technique of response priming, the behavior of subjects is clearly influenced by stimuli for which they report no awareness, and suitable experimental manipulations can lead to increasing priming effects despite decreasing prime identification (double dissociation).[99] Verbal report is widely considered to be the most reliable indicator of consciousness, but it raises a number of issues.[100] For one thing, if verbal reports are treated as observations, akin to observations in other branches of science, then the possibility arises that they may contain errors—but it is difficult to make sense of the idea that subjects could be wrong about their own experiences, and even more difficult to see how such an error could be detected.[101] Daniel Dennett has argued for an approach he calls heterophenomenology, which means treating verbal reports as stories that may or may not be true, but his ideas about how to do this have not been widely adopted.[102] Another issue with verbal report as a criterion is that it restricts the field of study to humans who have language: this approach cannot be used to study consciousness in other species, pre-linguistic children, or people with types of brain damage that impair language. As a third issue, philosophers who dispute the validity of the Turing test may feel that it is possible, at least in principle, for verbal report to be dissociated from consciousness entirely: a philosophical zombie may give detailed verbal reports of awareness in the absence of any genuine awareness.[103] Although verbal report is in practice the "gold standard" for ascribing consciousness, it is not the only possible criterion.[100] In medicine, consciousness is assessed as a combination of verbal behavior, arousal, brain activity, and purposeful movement. The last three of these can be used as indicators of consciousness when verbal behavior is absent.[104][105] The scientific literature regarding the neural bases of arousal and purposeful movement is very extensive. Their reliability as indicators of consciousness is disputed, however, due to numerous studies showing that alert human subjects can be induced to behave purposefully in a variety of ways in spite of reporting a complete lack of awareness.[99] Studies related to the neuroscience of free will have also shown that the influence consciousness has on decision-making is not always straightforward.[106] |

口頭報告による測定 曖昧なイメージのネッカーキューブ 意識に関する実験研究は、普遍的に受け入れられた操作上の定義がないため、特別な困難を伴う。意識に特化した実験の大部分では、被験者は人間であり、使用 される基準は言語による報告である。言い換えれば、被験者は自分の経験を記述するよう求められ、その記述は意識の内容の観察として扱われる[97]。 例えば、ネッカー・キューブを凝視し続ける被験者は通常、刺激自体は変わらないにもかかわらず、それが2つの3次元構成の間で「反転」するのを体験したと 報告する[98]。その目的は、(言語的報告によって示される)刺激に対する意識的認識と、刺激が脳活動や行動に及ぼす影響との関係を理解することであ る。反応プライミングの技法などいくつかのパラダイムでは、被験者の行動は、被験者が何も意識していないと報告する刺激によって明らかに影響を受け、適切 な実験操作によって、プライム識別(二重解離)が減少するにもかかわらずプライミング効果が増加することがある[99]。 言語報告は意識の最も信頼できる指標であると広く考えられているが、多くの問題を提起している[100]。1つには、言語報告が他の科学分野の観察と同様 に観察として扱われる場合、誤りが含まれている可能性が生じるが、被験者が自分の経験について間違っている可能性があるという考えを理解することは困難で あり、そのような誤りをどのように検出できるかを見ることはさらに困難である。 [101] ダニエル・デネットは、異質現象学と呼ぶアプローチを主張している。異質現象学とは、言語による報告を、真実であるかもしれないし、真実でないかもしれな い物語として扱うことを意味するが、これを行う方法に関する彼の考えは広く採用されていない[102]。基準としての言語による報告のもう一つの問題は、 研究対象が言語を持つ人間に限定されることである。第三の問題として、チューリング・テストの有効性に異議を唱える哲学者は、言語による報告が意識から完 全に切り離されることは、少なくとも原理的には可能であると感じるかもしれない。 医学では、意識は言語行動、覚醒、脳活動、目的意識をもった運動の組み合わせとして評価される。覚醒と目的運動の神経基盤に関する科学的文献は非常に広範 である。自由意志の神経科学に関連する研究は、意識が意思決定 に及ぼす影響が必ずしも一筋縄ではいかないことも示してい る[106]。 |

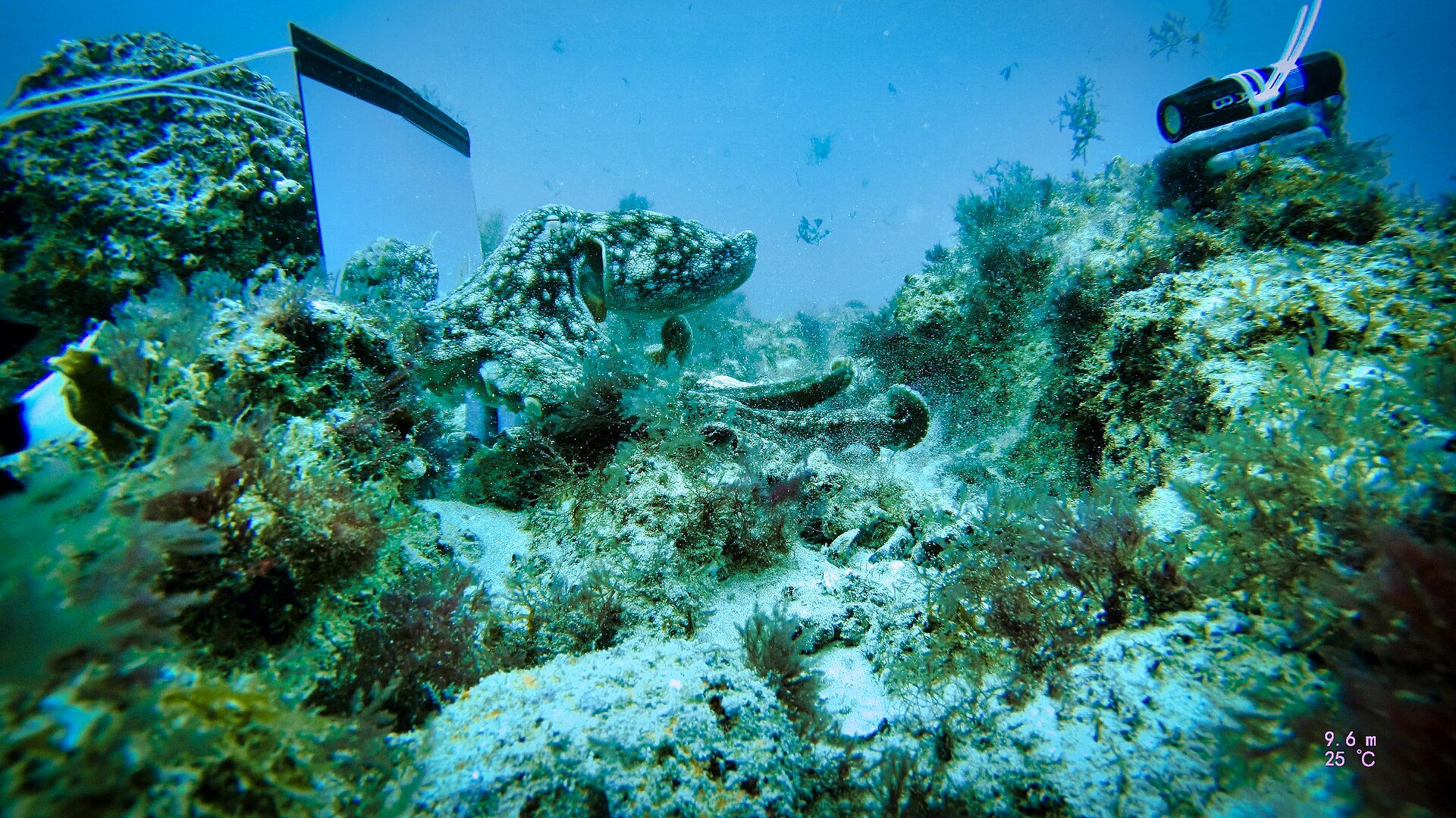

| Mirror test and contingency awareness See also: Mirror test  Mirror test subjected on a common octopus Another approach applies specifically to the study of self-awareness, that is, the ability to distinguish oneself from others. In the 1970s Gordon Gallup developed an operational test for self-awareness, known as the mirror test. The test examines whether animals are able to differentiate between seeing themselves in a mirror versus seeing other animals. The classic example involves placing a spot of coloring on the skin or fur near the individual's forehead and seeing if they attempt to remove it or at least touch the spot, thus indicating that they recognize that the individual they are seeing in the mirror is themselves.[107] Humans (older than 18 months) and other great apes, bottlenose dolphins, orcas, pigeons, European magpies and elephants have all been observed to pass this test.[108] While some other animals like pigs have been shown to find food by looking into the mirror.[109] Contingency awareness is another such approach, which is basically the conscious understanding of one's actions and its effects on one's environment.[110] It is recognized as a factor in self-recognition. The brain processes during contingency awareness and learning is believed to rely on an intact medial temporal lobe and age. A study done in 2020 involving transcranial direct current stimulation, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and eyeblink classical conditioning supported the idea that the parietal cortex serves as a substrate for contingency awareness and that age-related disruption of this region is sufficient to impair awareness.[111] |

ミラーテストと偶発性意識 こちらも参照のこと: ミラーテスト  タコを使ったミラーテスト もうひとつのアプローチは、自己認識、つまり自分と他者を区別する能力の研究に特化している。1970年代、ゴードン・ギャラップは、ミラーテストとして 知られる自己認識のテストを開発した。このテストでは、動物が鏡に映った自分と他の動物を見た自分を区別できるかどうかを調べる。古典的な例では、個体の 額の近くの皮膚や毛皮に着色料のスポットを置き、それを取り除こうとするか、少なくともスポットに触れるかどうかを見ることで、鏡に映っている個体が自分 自身であることを認識していることを示す[107]。ヒト(18ヶ月以上)、その他の類人猿、バンドウイルカ、シャチ、ハト、ヨーロッパカササギ、ゾウは すべて、このテストに合格することが観察されている[108]。 偶発性認知もそのようなアプローチのひとつで、基本的には自分の行動とそれが環境に及ぼす影響を意識的に理解することである[110]。偶発性認知と学習 の脳内プロセスは、無傷の内側側頭葉と年齢に依存していると考えられている。経頭蓋直流電流刺激、磁気共鳴画像法(MRI)、アイブリンク古典的条件付け を含む2020年に行われた研究では、頭頂皮質が偶発性意識の基質として機能し、この領域の加齢による障害は意識を損なうのに十分であるという考えが支持 された[111]。 |

Neural correlates Schema of the neural processes underlying consciousness, from Christof Koch A major part of the scientific literature on consciousness consists of studies that examine the relationship between the experiences reported by subjects and the activity that simultaneously takes place in their brains—that is, studies of the neural correlates of consciousness. The hope is to find that activity in a particular part of the brain, or a particular pattern of global brain activity, which will be strongly predictive of conscious awareness. Several brain imaging techniques, such as EEG and fMRI, have been used for physical measures of brain activity in these studies.[112] Another idea that has drawn attention for several decades is that consciousness is associated with high-frequency (gamma band) oscillations in brain activity. This idea arose from proposals in the 1980s, by Christof von der Malsburg and Wolf Singer, that gamma oscillations could solve the so-called binding problem, by linking information represented in different parts of the brain into a unified experience.[113] Rodolfo Llinás, for example, proposed that consciousness results from recurrent thalamo-cortical resonance where the specific thalamocortical systems (content) and the non-specific (centromedial thalamus) thalamocortical systems (context) interact in the gamma band frequency via synchronous oscillations.[114] A number of studies have shown that activity in primary sensory areas of the brain is not sufficient to produce consciousness: it is possible for subjects to report a lack of awareness even when areas such as the primary visual cortex (V1) show clear electrical responses to a stimulus.[115] Higher brain areas are seen as more promising, especially the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in a range of higher cognitive functions collectively known as executive functions.[116] There is substantial evidence that a "top-down" flow of neural activity (i.e., activity propagating from the frontal cortex to sensory areas) is more predictive of conscious awareness than a "bottom-up" flow of activity.[117] The prefrontal cortex is not the only candidate area, however: studies by Nikos Logothetis and his colleagues have shown, for example, that visually responsive neurons in parts of the temporal lobe reflect the visual perception in the situation when conflicting visual images are presented to different eyes (i.e., bistable percepts during binocular rivalry).[118] Furthermore, top-down feedback from higher to lower visual brain areas may be weaker or absent in the peripheral visual field, as suggested by some experimental data and theoretical arguments;[119] nevertheless humans can perceive visual inputs in the peripheral visual field arising from bottom-up V1 neural activities.[119][120] Meanwhile, bottom-up V1 activities for the central visual fields can be vetoed, and thus made invisible to perception, by the top-down feedback, when these bottom-up signals are inconsistent with the brain's internal model of the visual world.[119][120] Modulation of neural responses may correlate with phenomenal experiences. In contrast to the raw electrical responses that do not correlate with consciousness, the modulation of these responses by other stimuli correlates surprisingly well with an important aspect of consciousness: namely with the phenomenal experience of stimulus intensity (brightness, contrast). In the research group of Danko Nikolić it has been shown that some of the changes in the subjectively perceived brightness correlated with the modulation of firing rates while others correlated with the modulation of neural synchrony.[121] An fMRI investigation suggested that these findings were strictly limited to the primary visual areas.[122] This indicates that, in the primary visual areas, changes in firing rates and synchrony can be considered as neural correlates of qualia—at least for some type of qualia. In 2013, the perturbational complexity index (PCI) was proposed, a measure of the algorithmic complexity of the electrophysiological response of the cortex to transcranial magnetic stimulation. This measure was shown to be higher in individuals that are awake, in REM sleep or in a locked-in state than in those who are in deep sleep or in a vegetative state,[123] making it potentially useful as a quantitative assessment of consciousness states. Assuming that not only humans but even some non-mammalian species are conscious, a number of evolutionary approaches to the problem of neural correlates of consciousness open up. For example, assuming that birds are conscious—a common assumption among neuroscientists and ethologists due to the extensive cognitive repertoire of birds—there are comparative neuroanatomical ways to validate some of the principal, currently competing, mammalian consciousness–brain theories. The rationale for such a comparative study is that the avian brain deviates structurally from the mammalian brain. So how similar are they? What homologs can be identified? The general conclusion from the study by Butler, et al.[124] is that some of the major theories for the mammalian brain[125][126][127] also appear to be valid for the avian brain. The structures assumed to be critical for consciousness in mammalian brains have homologous counterparts in avian brains. Thus the main portions of the theories of Crick and Koch,[125] Edelman and Tononi,[126] and Cotterill[127] seem to be compatible with the assumption that birds are conscious. Edelman also differentiates between what he calls primary consciousness (which is a trait shared by humans and non-human animals) and higher-order consciousness as it appears in humans alone along with human language capacity.[126] Certain aspects of the three theories, however, seem less easy to apply to the hypothesis of avian consciousness. For instance, the suggestion by Crick and Koch that layer 5 neurons of the mammalian brain have a special role, seems difficult to apply to the avian brain, since the avian homologs have a different morphology. Likewise, the theory of Eccles[128][129] seems incompatible, since a structural homolog/analogue to the dendron has not been found in avian brains. The assumption of an avian consciousness also brings the reptilian brain into focus. The reason is the structural continuity between avian and reptilian brains, meaning that the phylogenetic origin of consciousness may be earlier than suggested by many leading neuroscientists. Joaquin Fuster of UCLA has advocated the position of the importance of the prefrontal cortex in humans, along with the areas of Wernicke and Broca, as being of particular importance to the development of human language capacities neuro-anatomically necessary for the emergence of higher-order consciousness in humans.[130] A study in 2016 looked at lesions in specific areas of the brainstem that were associated with coma and vegetative states. A small region of the rostral dorsolateral pontine tegmentum in the brainstem was suggested to drive consciousness through functional connectivity with two cortical regions, the left ventral anterior insular cortex, and the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex. These three regions may work together as a triad to maintain consciousness.[131] |

神経相関 クリストフ・コッホによる、意識の根底にある神経プロセスの模式図 意識に関する科学文献の大部分は、被験者が報告した体験と、同時に脳内で起こった活動の関係を調べる研究、つまり意識の神経相関に関する研究である。つま り、意識の神経相関に関する研究である。脳の特定部位の活動、あるいは全体的な脳活動の特定パターンを見つけることで、意識を強く予測することができると 期待されている。EEGやfMRIといったいくつかの脳画像技術が、こうした研究における脳活動の物理的測定に用いられてきた[112]。 数十年にわたって注目されてきたもう一つの考え方は、意識は脳活動の高周波数(ガンマ帯域)の振動と関連しているというものである。この考え方は、 1980年代にクリストフ・フォン・デア・マルスブルグとウルフ・シンガーが、脳の異なる部分に表現された情報を統一された経験に結びつけることによっ て、ガンマ振動がいわゆる結合問題を解決できるという提案をしたことから生まれた[113]。 [例えば、ロドルフォ・リナスは、意識は、特定の視床皮質系(内容)と非特異的(視床中部)視床皮質系(文脈)が同期振動を介してガンマ帯周波数で相互作 用する、視床-皮質共鳴の反復から生じるという仮説を提唱した[114]。 一次視覚野(V1)のような領域が刺激に対して明瞭な電気的 反応を示していても、被験者が意識の欠如を報告することは可 能である、 しかし、前頭前皮質だけが候補領域というわけではない。例えば、Nikos Logothetisと彼の同僚による研究では、側頭葉の一部の視覚に反応するニューロンは、相反する視覚像が異なる眼に提示された状況(すなわち、両眼 視時の双安定知覚)における視覚知覚を反映することが示されている、 さらに、いくつかの実験データや理論的な議論から示唆されているように、高次視覚野から低次視覚野へのトップダウン・フィードバックは、周辺視野では弱い か、あるいは存在しない可能性がある[119]。 [119][120]一方、中心視野に対するボトムアップのV1活動は、これらのボトムアップ信号が視覚世界に関する脳の内部モデルと矛盾している場合、 トップダウンフィードバックによって拒否され、知覚から見えなくなることがある[119][120]。 神経反応の変調は現象的経験と相関する可能性がある。意識と相関しない生の電気的反応とは対照的に、他の刺激によるこれらの反応の変調は、意識の重要な側 面、すなわち刺激強度(明るさ、コントラスト)の現象的経験と驚くほどよく相関する。Danko Nikolićの研究グループでは、主観的に知覚される明るさの変化の一部は発火率の変調と相関し、他の変化は神経同期の変調と相関することが示されてい る[121]。 2013年に、経頭蓋磁気刺激に対する皮質の電気生理学的反応のアルゴリズム的複雑さの尺度である摂動的複雑さ指数(PCI)が提案された。この指標は、 覚醒状態、レム睡眠状態、ロックイン状態にある個体では、深い睡眠状態や植物状態にある個体よりも高いことが示されており[123]、意識状態の定量的評 価として有用である可能性がある。 ヒトだけでなく、哺乳類以外の種でさえも意識があると仮定すると、意識の神経相関の問題に対する進化論的アプローチが数多く開けてくる。例えば、鳥類に意 識があると仮定すると、これは鳥類の広範な認知レパートリーのため、神経科学者や倫理学者の間では一般的な仮定であるが、現在競合している主要な哺乳類の 意識脳理論のいくつかを検証する比較神経解剖学的方法がある。このような比較研究を行う根拠は、鳥類の脳は哺乳類の脳から構造的に逸脱しているからであ る。では、どの程度似ているのだろうか?どのようなホモログが確認できるのだろうか?バトラーら[124]の研究から得られた一般的な結論は、哺乳類の脳 に関する主要な理論[125][126][127]のいくつかは、鳥類の脳にも有効であると思われるということである。哺乳類の脳で意識に重要であると想 定される構造は、鳥類の脳でも相同な構造を持つ。したがって、クリックとコッホ[125]、エーデルマンとトノーニ[126]、コッテリル[127]の理 論の主要部分は、鳥類に意識があるという仮定と互換性があるように思われる。エーデルマンはまた、彼が一次意識と呼ぶもの(これはヒトとヒト以外の動物に 共通する特徴である)と、ヒトの言語能力とともにヒトだけに現れる高次の意識とを区別している[126]。しかし、3つの理論のある側面は、鳥類の意識の 仮説に適用するのは容易ではないように思われる。例えば、哺乳類の脳の第5層ニューロンが特別な役割を担っているというクリックとコッホの示唆は、鳥類の ホモログが異なる形態を持っているため、鳥類の脳に適用するのは難しいように思われる。同様に、エクルズの理論[128][129]も、鳥類の脳ではデン ドロンの構造的なホモログ/アナログが見つかっていないため、相容れないように思われる。鳥類の意識を仮定すると、爬虫類の脳にも焦点が当たる。鳥類の脳 と爬虫類の脳には構造的な連続性があり、意識の系統的起源は、多くの主要な神経科学者が示唆するよりも早い可能性があるからだ。 UCLAのホアキン・フスターは、ウェルニッケとブローカの領域とともに、ヒトにおける前頭前皮質がヒトの言語能力の発達に個別主義的に重要であり、ヒトにおける高次の意識の出現に神経解剖学的に必要であるという立場を提唱している[130]。 2016年の研究では、昏睡状態や植物状態と関連する脳幹の特定領域の病変が調べられた。脳幹の吻側背外側脳橋の小領域が、2つの皮質領域、左腹側前島皮 質、および前前帯状皮質との機能的結合を通じて意識を駆動することが示唆された。これら3つの領域は、意識を維持するために三位一体となって働いている可 能性がある[131]。 |

| Models Further information: Models of consciousness A wide range of empirical theories of consciousness have been proposed.[132][133][134] Adrian Doerig and colleagues list 13 notable theories,[134] while Anil Seth and Tim Bayne list 22 notable theories.[133] Global workspace theory Global workspace theory (GWT) is a cognitive architecture and theory of consciousness proposed by the cognitive psychologist Bernard Baars in 1988. Baars explains the theory with the metaphor of a theater, with conscious processes represented by an illuminated stage. This theater integrates inputs from a variety of unconscious and otherwise autonomous networks in the brain and then broadcasts them to unconscious networks (represented in the metaphor by a broad, unlit "audience"). The theory has since been expanded upon by other scientists including cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene and Lionel Naccache.[135][136] Integrated information theory Integrated information theory (IIT), pioneered by neuroscientist Giulio Tononi in 2004, postulates that consciousness resides in the information being processed and arises once the information reaches a certain level of complexity. Additionally, IIT is one of the only leading theories of consciousness that attempts to create a 1:1 mapping between conscious states and precise, formal mathematical descriptions of those mental states. Proponents of this model suggest that it may provide a physical grounding for consciousness in neurons, as they provide the mechanism by which information is integrated. This also relates to the "hard problem of consciousness" proposed by David Chalmers. The theory remains controversial, because of its lack of credibility.[clarification needed][137][138][76] Orchestrated objective reduction Orchestrated objective reduction (Orch-OR), or the quantum theory of mind, was proposed by scientists Roger Penrose and Stuart Hameroff, and states that consciousness originates at the quantum level inside neurons. The mechanism is held to be a quantum process called objective reduction that is orchestrated by cellular structures called microtubules, which form the cytoskeleton around which the brain is built. The duo proposed that these quantum processes accounted for creativity, innovation, and problem-solving abilities. Penrose published his views in the book The Emperor's New Mind. In 2014, the discovery of quantum vibrations inside microtubules gave new life to the argument.[76] Attention schema theory In 2011, Graziano and Kastner[139] proposed the "attention schema" theory of awareness. In that theory, specific cortical areas, notably in the superior temporal sulcus and the temporo-parietal junction, are used to build the construct of awareness and attribute it to other people. The same cortical machinery is also used to attribute awareness to oneself. Damage to these cortical regions can lead to deficits in consciousness such as hemispatial neglect. In the attention schema theory, the value of explaining the feature of awareness and attributing it to a person is to gain a useful predictive model of that person's attentional processing. Attention is a style of information processing in which a brain focuses its resources on a limited set of interrelated signals. Awareness, in this theory, is a useful, simplified schema that represents attentional states. To be aware of X is explained by constructing a model of one's attentional focus on X. Entropic brain theory The entropic brain is a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. The theory suggests that the brain in primary states such as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, early psychosis and under the influence of psychedelic drugs, is in a disordered state; normal waking consciousness constrains some of this freedom and makes possible metacognitive functions such as internal self-administered reality testing and self-awareness.[140][141][142][143] Criticism has included questioning whether the theory has been adequately tested.[144] Projective consciousness model In 2017, work by David Rudrauf and colleagues, including Karl Friston, applied the active inference paradigm to consciousness, leading to the projective consciousness model (PCM), a model of how sensory data is integrated with priors in a process of projective transformation. The authors argue that, while their model identifies a key relationship between computation and phenomenology, it does not completely solve the hard problem of consciousness or completely close the explanatory gap.[145] Claustrum being the conductor for consciousness In 2004, a proposal was made by molecular biologist Francis Crick (co-discoverer of the double helix), which stated that to bind together an individual's experience, a conductor of an orchestra is required. Together with neuroscientist Christof Koch, he proposed that this conductor would have to collate information rapidly from various regions of the brain. The duo reckoned that the claustrum was well suited for the task. However, Crick died while working on the idea.[76] The proposal is backed by a study done in 2014, where a team at the George Washington University induced unconsciousness in a 54-year-old woman suffering from intractable epilepsy by stimulating her claustrum. The woman underwent depth electrode implantation and electrical stimulation mapping. The electrode between the left claustrum and anterior-dorsal insula was the one which induced unconsciousness. Correlation for interactions affecting medial parietal and posterior frontal channels during stimulation increased significantly as well. Their findings suggested that the left claustrum or anterior insula is an important part of a network that subserves consciousness, and that disruption of consciousness is related to increased EEG signal synchrony within frontal-parietal networks. However, this remains an isolated, hence inconclusive study.[76][146] |

モデル さらに詳しい情報 意識のモデル 意識に関する様々な経験的理論が提案されている[132][133][134]。Adrian Doerigと同僚は13の注目すべき理論を挙げており[134]、Anil SethとTim Bayneは22の注目すべき理論を挙げている[133]。 グローバルワークスペース理論 グローバル・ワークスペース理論(Global workspace theory, GWT)は、1988年に認知心理学者のバーナード・バースによって提唱された認知アーキテクチャと意識の理論である。バースはこの理論を劇場の隠喩で説 明し、意識的プロセスを照明された舞台で表している。この劇場は、脳内のさまざまな無意識のネットワークや自律的なネットワークからの入力を統合し、それ を無意識のネットワーク(隠喩では、照明のない広い「観客」で表される)に放送する。この理論はその後、認知神経科学者のスタニスラス・デヘーヌやライオ ネル・ナカシュを含む他の科学者によって拡張されてきた[135][136]。 統合情報理論 統合情報理論(IIT)は、2004年に神経科学者のジュリオ・トノーニによって提唱された理論で、意識は処理される情報の中に存在し、情報が一定の複雑 さに達すると発生すると仮定している。さらにIITは、意識状態とそれらの精神状態の正確で正式な数学的記述との間に1対1の対応付けを作ろうとする、意 識に関する唯一の主要な理論のひとつである。このモデルの支持者は、情報が統合されるメカニズムをニューロンが提供することで、ニューロンに意識の物理的 根拠を与える可能性があると示唆している。これは、デイヴィッド・チャルマーズが提唱した「意識のハード・プロブレム」とも関連している。この理論は信憑 性に欠けるため、依然として議論の的となっている[要解説][137][138][76]。 オーケストレーションされた客観的還元 オーケストレイテッド・オブジェクティブ・リダクション(Orch-OR)、すなわち心の量子論は、科学者のロジャー・ペンローズとスチュアート・ハメロ フによって提唱されたもので、意識はニューロン内部の量子レベルで発生するとしている。そのメカニズムは、脳を構築する細胞骨格を形成する微小管と呼ばれ る細胞構造によって編成される目的還元と呼ばれる量子プロセスであるとされている。二人は、この量子プロセスが創造性、革新性、問題解決能力を説明すると 提唱した。ペンローズは『The Emperor's New Mind』という本の中で彼の見解を発表した。2014年、微小管内の量子振動が発見され、この議論に新たな命が吹き込まれた[76]。 注意スキーマ理論 2011年、グラツィアーノとカストナー[139]は意識の「注意スキーマ」理論を提唱した。この理論では、特に上側頭溝と側頭-頭頂接合部にある特定の 皮質領域が、意識という概念を構築し、それを他者に帰属させるために使用される。同じ皮質機械は、自分自身に意識を帰属させるためにも使われる。これらの 皮質領域の損傷は、半側空間無視のような意識障害を引き起こす。注意スキーマ理論では、意識の特徴を説明し、それをある人格に帰属させることの価値は、そ の人格の注意処理に関する有用な予測モデルを得ることにある。注意とは、脳が相互に関連する限られた信号の集合にリソースを集中させる情報処理様式であ る。この理論における「気づき」とは、注意状態を表す有用で単純化されたスキーマである。Xを意識することは、Xへの注意集中のモデルを構築することで説 明できる。 エントロピー脳理論 エントロピック脳は、サイケデリック薬物を使った神経画像研究によってもたらされた意識状態の理論である。この理論では、急速眼球運動(REM)睡眠、精 神病初期、サイケデリック薬物の影響下などの一次的な状態における脳は無秩序な状態にあり、通常の覚醒意識はこの自由をある程度制約し、内的自己管理現実 テストや自己認識などのメタ認知機能を可能にしているとしている[140][141][142][143]。批判には、この理論が十分に検証されているか どうかを疑問視するものがある[144]。 投影意識モデル 2017年、Karl Fristonを含むDavid Rudraufと同僚たちによる研究は、能動的推論のパラダイムを意識に適用し、投影変換のプロセスにおいて感覚データがどのようにプライアと統合される かのモデルである投影意識モデル(PCM)を導いた。著者らは、彼らのモデルは計算と現象学の間の重要な関係を特定するものの、意識の難問を完全に解決し たり、説明のギャップを完全に埋めるものではないと主張している[145]。 クラウストラムは意識の指揮者である 2004年、分子生物学者のフランシス・クリック(二重らせんの共同発見者)によって、個人の経験を束ねるにはオーケストラの指揮者が必要であるという提 案がなされた。彼は神経科学者のクリストフ・コッホと共同で、この指揮者は脳の様々な領域からの情報を迅速に照合する必要があると提唱した。二人は、クラ ウストラムがその仕事に適していると考えた。しかし、クリックはこのアイデアに取り組んでいる最中に亡くなった[76]。 この提案は2014年に行われた研究によって裏付けられている。ジョージ・ワシントン大学の研究チームは、難治性てんかんを患っている54歳の女性に対 し、クラウストラムを刺激することで無意識を誘発した。この女性は深部電極の埋め込みと電気刺激マッピングを受けた。左の鎖骨と前背側島皮質との間の電極 が、意識を誘発するものであった。刺激中の内側頭頂および後前頭チャネルに影響する相互作用の相関も有意に増加した。この結果は、左の耳介または前部島が 意識を司るネットワークの重要な一部であること、そして意識の混乱が前頭-頭頂ネットワーク内の脳波信号同期の増加と関連していることを示唆した。しか し、これはまだ孤立した研究であるため、結論は出ていない[76][146]。 |