認識

Cognition

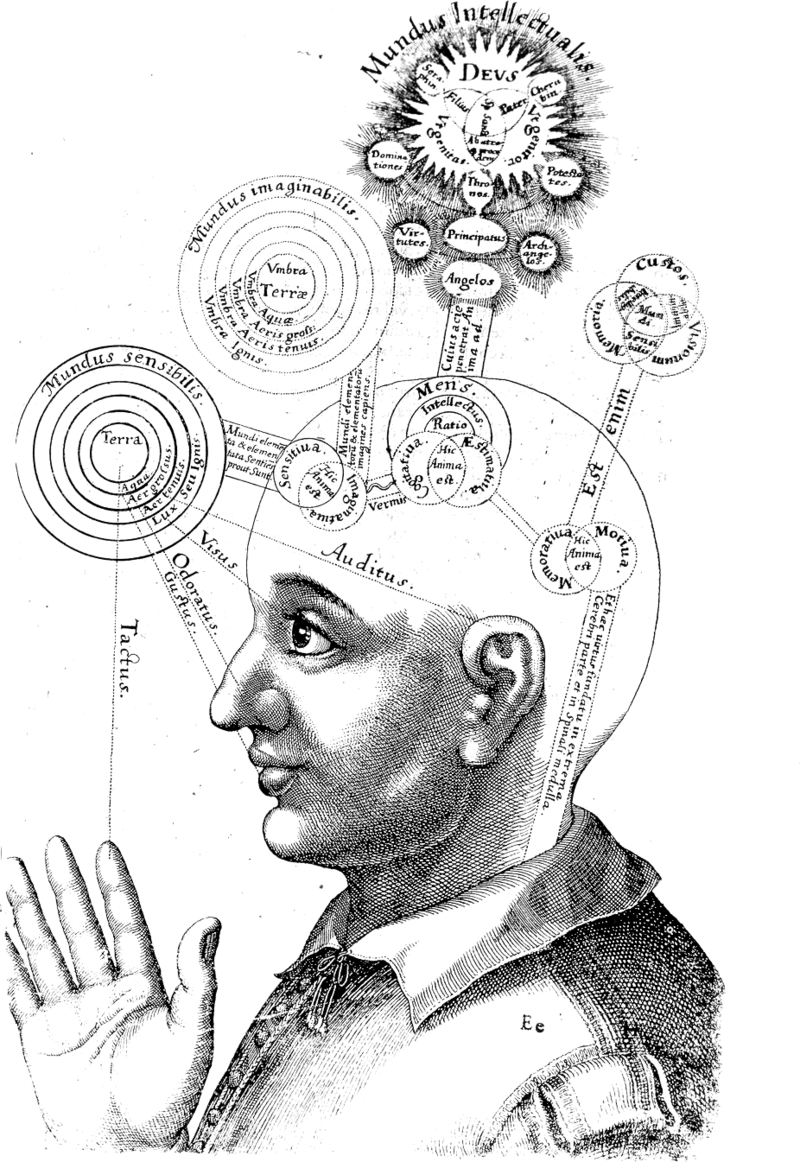

A cognitive model, as illustrated by Robert Fludd (1619)

☆認知(Cognition) とは、「思考、経験、感覚を通じて知識と理解を獲得する精神的な作用または過程」である。[2] 認知は、知覚、注意、思考、想像力、知能、知識の形成、記憶と作業記憶、判断と評価、推論と計算、問題解決と意思決定、言語の理解と生成など、知的機能と 過程のすべての側面を含みます。認知過程は、既存の知識を用いて新しい知識を発見する。 認知プロセスは、言語学、音楽学、麻酔学、神経科学、精神医学、心理学、教育学、哲学、人類学、生物学、システム学、論理学、コンピュータサイエンスな ど、さまざまな分野において、非常に異なる観点から分析されている[3]。認知の分析に関するこれらのアプローチやその他のアプローチ(具体化認知など) は、徐々に自立した学問分野として発展している認知科学の分野において統合されている。

| Cognition is the

"mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding

through thought, experience, and the senses".[2] It encompasses all

aspects of intellectual functions and processes such as: perception,

attention, thought, imagination, intelligence, the formation of

knowledge, memory and working memory, judgment and evaluation,

reasoning and computation, problem-solving and decision-making,

comprehension and production of language. Cognitive processes use

existing knowledge to discover new knowledge. Cognitive processes are analyzed from very different perspectives within different contexts, notably in the fields of linguistics, musicology, anesthesia, neuroscience, psychiatry, psychology, education, philosophy, anthropology, biology, systemics, logic, and computer science.[3] These and other approaches to the analysis of cognition (such as embodied cognition) are synthesized in the developing field of cognitive science, a progressively autonomous academic discipline. |

認知とは、「思考、経験、感覚を通じて知識と理解を獲得する精神的な作

用または過程」である。[2]

認知は、知覚、注意、思考、想像力、知能、知識の形成、記憶と作業記憶、判断と評価、推論と計算、問題解決と意思決定、言語の理解と生成など、知的機能と

過程のすべての側面を含む。認知過程は、既存の知識を用いて新しい知識を発見する。 認知プロセスは、言語学、音楽学、麻酔学、神経科学、精神医学、心理学、教育学、哲学、人類学、生物学、システム学、論理学、コンピュータサイエンスな ど、さまざまな分野において、非常に異なる観点から分析されている[3]。認知の分析に関するこれらのアプローチやその他のアプローチ(具体化認知など) は、徐々に自立した学問分野として発展している認知科学の分野において統合されている。 |

| Etymology The word cognition dates back to the 15th century, where it meant "thinking and awareness".[4] The term comes from the Latin noun cognitio ('examination', 'learning', or 'knowledge'), derived from the verb cognosco, a compound of con ('with') and gnōscō ('know'). The latter half, gnōscō, itself is a cognate of a Greek verb, gi(g)nósko (γι(γ)νώσκω, 'I know,' or 'perceive').[5][6] |

語源 認知(cognition)の語源は15世紀にまで遡り、「思考と認識」を意味する[4]。この語はラテン語の名詞cognitio(「試験」、「学 習」、「知識」)に由来し、con(「~と共に」)とgnōscō(「知っている」)の合成語である動詞cognoscoに由来する。後半のgnōscō はギリシア語の動詞gi(g)nósko(γι(γ)νώσκω、「知っている」または「知覚する」)の同義語である[5][6]。 |

| Early studies Despite the word cognitive itself dating back to the 15th century,[4] attention to cognitive processes came about more than eighteen centuries earlier, beginning with Aristotle (384–322 BCE) and his interest in the inner workings of the mind and how they affect the human experience. Aristotle focused on cognitive areas pertaining to memory, perception, and mental imagery. He placed great importance on ensuring that his studies were based on empirical evidence, that is, scientific information that is gathered through observation and conscientious experimentation.[7] Two millennia later, the groundwork for modern concepts of cognition was laid during the Enlightenment by thinkers such as John Locke and Dugald Stewart who sought to develop a model of the mind in which ideas were acquired, remembered and manipulated.[8] During the very early nineteenth century cognitive models were developed both in philosophy—particularly by authors writing about the philosophy of mind—and within medicine, especially by physicians seeking to understand how to cure madness. In Britain, these models were studied in the academy by scholars such as James Sully at University College London, and they were even used by politicians when considering the national Elementary Education Act 1870 (33 & 34 Vict. c. 75).[9] As psychology emerged as a burgeoning field of study in Europe, whilst also gaining a following in America, scientists such as Wilhelm Wundt, Herman Ebbinghaus, Mary Whiton Calkins, and William James would offer their contributions to the study of human cognition.[citation needed] |

初期の研究 コグニティブという言葉自体は15世紀にまでさかのぼるが[4]、コグニティブ・プロセスへの注目はそれよりも18世紀以上前に、アリストテレス(紀元前 384~322年)と彼の心の内部の働きへの関心、そしてそれらが人間の経験にどのような影響を与えるかへの関心から始まった。アリストテレスは、記憶、 知覚、心的イメージに関する認知領域に焦点を当てた。その2千年後、ジョン・ロックやデュガルド・スチュワートといった思想家たちによって、認識に関する 近代的概念の基礎が啓蒙主義時代に築かれた。 19世紀のごく初期には、哲学、特に心の哲学について執筆している著者たちによって、また医学、特に狂気を治療する方法を理解しようとする医師たちによっ て、認知モデルが開発された。イギリスでは、これらのモデルはユニヴァーシティ・カレッジ・ロンドンのジェームズ・サリーなどの学者によって学会で研究さ れ、1870年に国民初等教育法(33 & 34 Vict. 心理学がヨーロッパで急成長する研究分野として台頭する一方で、アメリカでも支持を集めるようになり、ヴィルヘルム・ヴント、ヘルマン・エビングハウス、 メアリー・ウィトン・カルキンズ、ウィリアム・ジェイムズなどの科学者が人間の認知の研究に貢献するようになる[要出典]。 |

| Early theorists Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) emphasized the notion of what he called introspection: examining the inner feelings of an individual. With introspection, the subject had to be careful with describing their feelings in the most objective manner possible in order for Wundt to find the information scientific.[10][11] Though Wundt's contributions are by no means minimal, modern psychologists find his methods to be too subjective and choose to rely on more objective procedures of experimentation to make conclusions about the human cognitive process.[citation needed] Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850–1909) conducted cognitive studies that mainly examined the function and capacity of human memory. Ebbinghaus developed his own experiment in which he constructed over 2,000 syllables made out of nonexistent words (for instance, 'EAS'). He then examined his own personal ability to learn these non-words. He purposely chose non-words as opposed to real words to control for the influence of pre-existing experience on what the words might symbolize, thus enabling easier recollection of them.[10][12] Ebbinghaus observed and hypothesized a number of variables that may have affected his ability to learn and recall the non-words he created. One of the reasons, he concluded, was the amount of time between the presentation of the list of stimuli and the recitation or recall of the same. Ebbinghaus was the first to record and plot a "learning curve" and a "forgetting curve".[13] His work heavily influenced the study of serial position and its effect on memory [citation needed] Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930) was an influential American pioneer in the realm of psychology. Her work also focused on human memory capacity. A common theory, called the recency effect, can be attributed to the studies that she conducted.[14] The recency effect, also discussed in the subsequent experiment section, is the tendency for individuals to be able to accurately recollect the final items presented in a sequence of stimuli. Calkin's theory is closely related to the aforementioned study and conclusion of the memory experiments conducted by Hermann Ebbinghaus.[15] William James (1842–1910) is another pivotal figure in the history of cognitive science. James was quite discontent with Wundt's emphasis on introspection and Ebbinghaus' use of nonsense stimuli. He instead chose to focus on the human learning experience in everyday life and its importance to the study of cognition. James' most significant contribution to the study and theory of cognition was his textbook Principles of Psychology which preliminarily examines aspects of cognition such as perception, memory, reasoning, and attention.[15] René Descartes (1596–1650) was a seventeenth-century philosopher who came up with the phrase "Cogito, ergo sum", which means "I think, therefore I am." He took a philosophical approach to the study of cognition and the mind, with his Meditations he wanted people to meditate along with him to come to the same conclusions as he did but in their own free cognition.[16] |

初期の理論家たち ヴィルヘルム・ヴント(1832-1920)は、内観と呼ばれる、個人の内なる感情を調べるという概念を重視した。内観では、ヴントが情報を科学的である と判断するために、被験者は自分の感情をできるだけ客観的な方法で記述することに注意しなければならなかった[10][11]。ヴントの貢献は決して小さ いものではないが、現代の心理学者は彼の方法が主観的すぎると判断し、人間の認知プロセスについて結論を出すために、より客観的な実験手順に頼ることを選 択した[要出典]。 ヘルマン・エビングハウス(1850-1909)は、主に人間の記憶の機能と能力を調べる認知研究を行った。エビングハウスは、存在しない単語(たとえば 「EAS」)から2,000以上の音節を作るという独自の実験を開発した。そして、これらの非単語を学習する自分自身の人格能力を調べた。エビングハウス は、自分が作った非単語を学習し想起す る能力に影響を与える可能性のある多くの変数を観察し、仮説 を立てた。その理由のひとつは、刺激のリストが提示されてから、それを暗唱したり思い出したりするまでの時間の長さであると彼は結論づけた。エビングハウ スは、「学習曲線」と「忘却曲線」を記録し、プロットした最初の人物である[13]。彼の研究は、直列位置とそれが記憶に及ぼす影響の研究に大きな影響を 与えた[要出典]。 メアリー・ホイットン・カルキンズ(1863-1930)は、心理学の領域で影響力のあるアメリカの先駆者であった。彼女の研究は人間の記憶能力にも焦点 を当てていた。再帰性効果と呼ばれる一般的な理論は、彼女が行った研究に起因している[14]。再帰性効果とは、この後の実験のセクションでも説明する が、一連の刺激の中で最後に提示された項目を正確に思い出すことができるという傾向のことである。カルキンの理論は、前述のヘルマン・エビングハウスによ る記憶実験の研究と結論と密接に関連している[15]。 ウィリアム・ジェームズ(1842-1910)は認知科学の歴史におけるもう一人の重要人物である。ジェームズは、ヴントが内観を重視し、エビングハウス が無意味な刺激を用いることに強い不満を抱いていた。彼はその代わりに、日常生活における人間の学習経験と、認知の研究におけるその重要性に焦点を当てる ことを選んだ。認知の研究と理論に対するジェームズの最も重要な貢献は、知覚、記憶、推論、注意などの認知の側面を予備的に検討した彼の教科書『心理学原 理』であった[15]。 ルネ・デカルト(1596-1650年)は17世紀の哲学者であり、「Cogito, ergo sum 」という言葉を考え出した。彼は認識と心の研究に対して哲学的なアプローチをとり、『瞑想録』では、人々が彼と一緒に瞑想し、彼と同じ結論に達することを 望んだが、彼ら自身の自由な認識においてであった[16]。 |

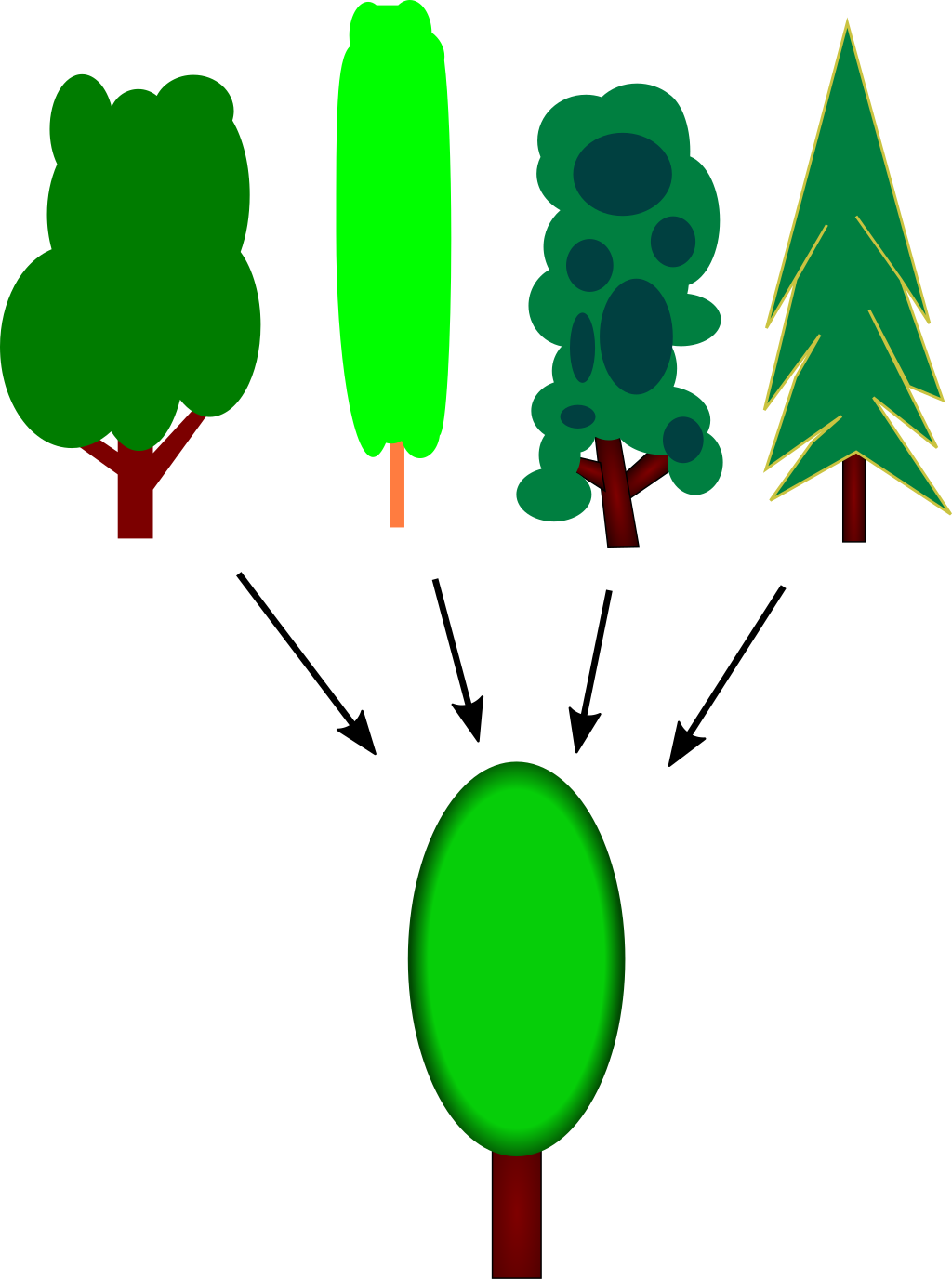

| Psychology Diagram  When the mind makes a generalization such as the concept of tree, it extracts similarities from numerous examples; the simplification enables higher-level thinking (abstract thinking). See also: Cognitivism (psychology) In psychology, the term "cognition" is usually used within an information processing view of an individual's psychological functions,[17] and such is the same in cognitive engineering.[18] In the study of social cognition, a branch of social psychology, the term is used to explain attitudes, attribution, and group dynamics.[17] However, psychological research within the field of cognitive science has also suggested an embodied approach to understanding cognition. Contrary to the traditional computationalist approach, embodied cognition emphasizes the body's significant role in the acquisition and development of cognitive capabilities.[19][20] Human cognition is conscious and unconscious, concrete or abstract, as well as intuitive (like knowledge of a language) and conceptual (like a model of a language). It encompasses processes such as memory, association, concept formation, pattern recognition, language, attention, perception, action, problem solving, and mental imagery.[21][22] Traditionally, emotion was not thought of as a cognitive process, but now much research is being undertaken to examine the cognitive psychology of emotion; research is also focused on one's awareness of one's own strategies and methods of cognition, which is called metacognition. The concept of cognition has gone through several revisions through the development of disciplines within psychology.[citation needed] Psychologists initially understood cognition governing human action as information processing. This was a movement known as cognitivism in the 1950s, emerging after the Behaviorist movement viewed cognition as a form of behavior.[23] Cognitivism approached cognition as a form of computation, viewing the mind as a machine and consciousness as an executive function.[19] However; post cognitivism began to emerge in the 1990s as the development of cognitive science presented theories that highlighted the necessity of cognitive action as embodied, extended, and producing dynamic processes in the mind.[24] The development of Cognitive psychology arose as psychology from different theories, and so began exploring these dynamics concerning mind and environment, starting a movement from these prior dualist paradigms that prioritized cognition as systematic computation or exclusively behavior.[19] |

心理学 ダイアグラム  樹木の概念のような一般化をするとき、心は多くの例から類似点を抽出し、単純化することでより高度な思考(抽象思考)を可能にする。 こちらも参照のこと: 認知主義(心理学) 社会心理学の一分野である社会的認知の研究では、この用語は態度、帰属、グループダイナミクスを説明するために使用される。伝統的な計算論的アプローチとは反対に、身体化された認知は、認知能力の獲得と発達における身体の重要な役割を強調している[19][20]。 人間の認知は、意識的であるか無意識的であるか、具体的であるか抽象的であるか、直観的であるか(言語の知識のような)、概念的であるか(言語のモデルの ような)である。伝統的に、情動は認知のプロセスとは考えられていな かったが、現在では情動の認知心理学を調べるために多くの 研究が行われている。認知の概念は、心理学における学問分野の発展を通じて、いくつかの改訂を経てきた。 心理学者は当初、人間の行動を支配する認知を情報処理として理解していた。これは1950年代に認知主義として知られる運動であり、行動主義運動が認知を 行動の一形態と見なした後に出現した[23]。認知主義は認知を計算の一形態としてアプローチし、心を機械として、意識を実行機能として見なした [19]。 [24]。認知心理学の発展は、異なる理論から心理学として生じ、そのため、心と環境に関するこれらのダイナミクスを探求し始め、認知を体系的な計算とし て、または排他的な行動として優先させるこれらの先行する二元論的パラダイムからの動きを開始した。 |

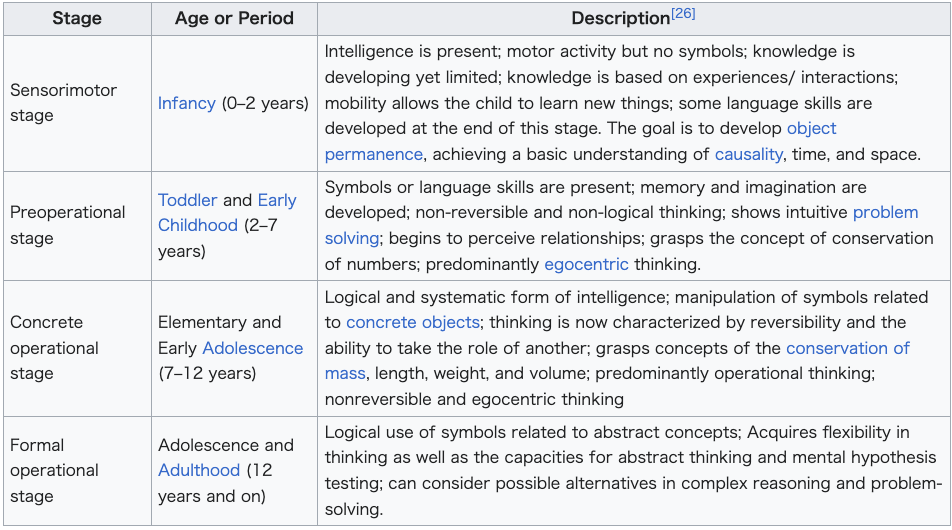

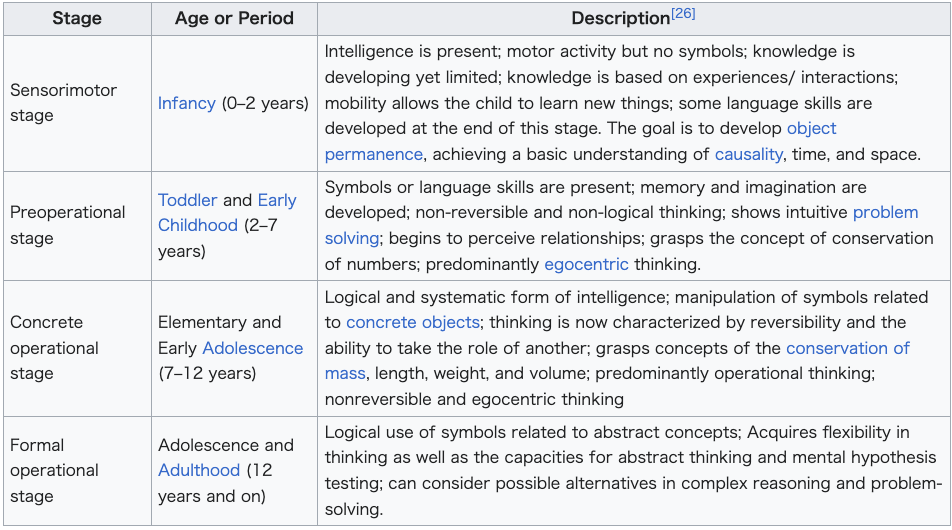

| Piaget's theory of cognitive development Main article: Piaget's theory of cognitive development For years, sociologists and psychologists have conducted studies on cognitive development, i.e. the construction of human thought or mental processes.[citation needed] Jean Piaget was one of the most important and influential people in the field of developmental psychology. He believed that humans are unique in comparison to animals because we have the capacity to do "abstract symbolic reasoning". His work can be compared to Lev Vygotsky, Sigmund Freud, and Erik Erikson who were also great contributors in the field of developmental psychology. Piaget is known for studying the cognitive development in children, having studied his own three children and their intellectual development, from which he would come to a theory of cognitive development that describes the developmental stages of childhood.[25]  |

ピアジェの認知発達理論 主な記事 ピアジェの認知発達理論 長年にわたり、社会学者や心理学者は認知発達、すなわち人間の思考や精神過程の構築に関する研究を行ってきた[要出典]。 ジャン・ピアジェは、発達心理学の分野で最も重要で影響力のある人物の一人である。彼は、人間は「抽象的な象徴的推論」をする能力を持っているため、動物 と比較してユニークであると考えた。彼の研究は、同じく発達心理学の分野で偉大な貢献をしたレフ・ヴィゴツキー、ジークムント・フロイト、エリック・エリ クソンと比較することができる。ピアジェは子どもの認知発達を研究したことで知られており、彼自身の3人の子どもと彼らの知的発達を研究し、そこから子ど も時代の発達段階を記述する認知発達理論を導き出した[25]。  |

| Beginning of cognition Studies on cognitive development have also been conducted in children beginning from the embryonal period to understand when cognition appears and what environmental attributes stimulate the construction of human thought or mental processes. Research shows the intentional engagement of fetuses with the environment, demonstrating cognitive achievements.[27] However, organisms with simple reflexes cannot cognize the environment alone because the environment is the cacophony of stimuli (electromagnetic waves, chemical interactions, and pressure fluctuations).[28] Their sensation is too limited by the noise to solve the cue problem–the relevant stimulus cannot overcome the noise magnitude if it passes through the senses (see the binding problem). Fetuses need external help to stimulate their nervous system in choosing the relevant sensory stimulus for grasping the perception of objects.[29] The Shared intentionality approach proposes a plausible explanation of perception development in this earlier stage. Initially, Michael Tomasello introduced the psychological construct of Shared intentionality, highlighting its contribution to cognitive development from birth.[30] This primary interaction provides unaware collaboration in mother-child dyads for environmental learning. Later, Igor Val Danilov developed this notion, expanding it to the intrauterine period and clarifying the neurophysiological processes underlying Shared intentionality.[31] According to the Shared intentionality approach, the mother shares the essential sensory stimulus of the actual cognitive problem with the child.[32] By sharing this stimulus, the mother provides a template for developing the young organism's nervous system.[33] Recent findings in research on child cognitive development [29][31][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][excessive citations] and advances in inter-brain neuroscience experiments[41][42][43][44][45] have made the above proposition plausible. Based on them, the shared intentionality hypothesis introduced the notion of pre-perceptual communication in the mother-fetus communication model due to nonlocal neuronal coupling.[27][31][33] This nonlocal coupling model refers to communication between two organisms through the copying of the adequate ecological dynamics by biological systems indwelling one environmental context, where a naive actor (Fetus) replicates information from an experienced actor (Mother) due to intrinsic processes of these dynamic systems (embodied information) but without interacting through sensory signals.[27][31][33] The Mother's heartbeats (a low-frequency oscillator) modulate relevant local neuronal networks in specific subsystems of both her and the nervous system of the fetus due to the effect of the interference of the low-frequency oscillator (Mother heartbeats) and already exhibited gamma activity in these neuronal networks (interference in physics is the combination of two or more electromagnetic waveforms to form a resultant wave).[27][31][33] Therefore, the subliminal perception in a fetus emerges due to Shared intentionality with the mother that stimulates cognition in this organism even before birth.[27][31][33] Further, cognition and emotions develop with the association of affective cues with stimuli responsible for triggering the neuronal pathways of simple reflexes.[46] This pre-perceptual multimodal integration can succeed owing to neuronal coherence in mother-child dyads beginning from pregnancy.[46] According to the pre-perceptual multimodal integration hypothesis based on empirical evidence, these cognitive-reflex and emotion-reflex stimuli conjunctions further form simple innate neuronal assemblies, shaping the cognitive and emotional neuronal patterns in statistical learning that are continuously connected with the neuronal pathways of reflexes.[46] Another crucial question in understanding the beginning of cognition is memory storage about the relevant ecological dynamics by the naive nervous system (i.e., memorizing the ecological condition of relevant sensory stimulus) at the molecular level – an engram. Evidence derived using optical imaging, molecular-genetic and optogenetic techniques in conjunction with appropriate behavioural analyses continues to offer support for the idea that changing the strength of connections between neurons is one of the major mechanisms by which engrams are stored in the brain.[47] Two (or more) possible mechanisms of cognition can involve both quantum effects[48] and synchronization of brain structures due to electromagnetic interference.[49][27][31][33] |

認知の始まり 認知がいつ現れるのか、どのような環境属性が人間の思考や心的プロセスの構築を刺激するのかを理解するために、胎児期から始まる子どもの認知発達に関する 研究も行われてきた。しかし、環境は刺激(電磁波、化学的相互作用、圧力変動)の不協和音であるため、単純な反射神経を持つ生物は単独で環境を認知するこ とはできない[28]。胎児は、物体の知覚を把握するために関連する感覚刺激を選択する際に、神経系を刺激する外部からの助けを必要としている。当初、マ イケル・トマセロは共有意図性という心理学的構成概念を導入し、出生時からの認知発達への寄与を強調した[30]。この主要な相互作用は、環境学習のため に母子ダイアドにおける無自覚な協働を提供する。その後、イゴール・ヴァル・ダニロフはこの概念を発展させ、子宮内期にまで拡大し、意図主義の基礎となる 神経生理学的プロセスを明らかにした[31]。意図主義の共有アプローチによると、母親は実際の認知問題の本質的な感覚刺激を子どもと共有する[32]。 子どもの認知発達に関する研究[29][31][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][過剰引用]における最近の知見や、脳間神経科 学実験[41][42][43][44][45]の進歩によって、上記の命題はもっともらしくなってきた。この非局所的結合モデルは、1つの環境コンテク ストを内在する生物システムによる適切な生態学的ダイナミクスのコピーを通じた2つの生物間のコミュニケーションを意味し、ナイーブな行為者(胎児)は、 これらのダイナミック・システムの内在的プロセス(具現化された情報)により、経験豊富な行為者(母親)からの情報を複製するが、感覚信号を通じて相互作 用することはない。 [27][31][33]母親の心拍(低周波発振器)は、低周波発振器(母親 の心拍)とこれらのニューロン・ネットワークにおいてすでに示され ているガンマ活動(物理学における干渉とは、2つ以上の電磁波 形が組み合わさって結果として1つの波動を形成することであ る)の干渉の影響によって、母親と胎児の神経系の両方の特定の サブシステムの関連する局所的なニューロン・ネットワークを変調 する。 [27][31][33]したがって、胎児におけるサブリミナル知覚は、出生前からこの生物の認知を刺激する母親との意図主義の共有によって出現する [27][31][33]。 さらに、認知と情動は、単純反射のニューロン経路を引き起こす刺激と情動的手がかりの関連付けによって発達する[46]。 [経験的証拠に基づく前認知的マルチモーダル統合仮説によれば、これらの認知-反射刺激および情動-反射刺激の結合は、さらに単純な生得的ニューロン集合 体を形成し、反射のニューロン経路と連続的に接続される統計的学習において、認知および情動ニューロンパターンを形成する[46]。 認知の始まりを理解する上でのもう一つの重要な疑問は、素朴神経系による関連する生態学的動態に関する記憶(すなわち、関連する感覚刺激の生態学的条件を 記憶すること)であり、分子レベルでのエングラムである。光イメージング、分子遺伝学的手法、光遺伝学的手法を適切な行動分析とともに用いて得られた証拠 は、ニューロン間の結合の強さを変化させることが、エングラムが脳に記憶される主要なメカニズムの一つであるという考えを支持し続けている[47]。 認知のメカニズムとしては、量子効果[48]と電磁干渉による脳構造の同期の2つ(またはそれ以上)が考えられる[49][27][31][33]。 |

| Common types of tests on human cognition Serial position The Serial-position effect is meant to test a theory of memory that states that when information is given in a serial manner, we tend to remember information at the beginning of the sequence, called the primacy effect, and information at the end of the sequence, called the recency effect. Consequently, information given in the middle of the sequence is typically forgotten, or not recalled as easily. This study predicts that the recency effect is stronger than the primacy effect, because the information that is most recently learned is still in working memory when asked to be recalled. Information that is learned first still has to go through a retrieval process. This experiment focuses on human memory processes.[50] Word superiority The word superiority effect experiment presents a subject with a word, or a letter by itself, for a brief period of time, i.e. 40 ms, and they are then asked to recall the letter that was in a particular location in the word. In theory, the subject should be better able to correctly recall the letter when it was presented in a word than when it was presented in isolation. This experiment focuses on human speech and language.[51] Brown–Peterson In the Brown–Peterson cohomology experiment, participants are briefly presented with a trigram and in one particular version of the experiment, they are then given a distractor task, asking them to identify whether a sequence of words is in fact words, or non-words (due to being misspelled, etc.). After the distractor task, they are asked to recall the trigram from before the distractor task. In theory, the longer the distractor task, the harder it will be for participants to correctly recall the trigram. This experiment focuses on human short-term memory.[52] Memory span During the memory span experiment, each subject is presented with a sequence of stimuli of the same kind; words depicting objects, numbers, letters that sound similar, and letters that sound dissimilar. After being presented with the stimuli, the subject is asked to recall the sequence of stimuli that they were given in the exact order in which it was given. In one particular version of the experiment, if the subject recalled a list correctly, the list length was increased by one for that type of material, and vice versa if it was recalled incorrectly. The theory is that people have a memory span of about seven items for numbers, the same for letters that sound dissimilar and short words. The memory span is projected to be shorter with letters that sound similar and with longer words.[53] Visual search In one version of the visual search experiment, a participant is presented with a window that displays circles and squares scattered across it. The participant is to identify whether there is a green circle on the window. In the featured search, the subject is presented with several trial windows that have blue squares or circles and one green circle or no green circle in it at all. In the conjunctive search, the subject is presented with trial windows that have blue circles or green squares and a present or absent green circle whose presence the participant is asked to identify. What is expected is that in the feature searches, reaction time, that is the time it takes for a participant to identify whether a green circle is present or not, should not change as the number of distractors increases. Conjunctive searches where the target is absent should have a longer reaction time than the conjunctive searches where the target is present. The theory is that in feature searches, it is easy to spot the target, or if it is absent, because of the difference in color between the target and the distractors. In conjunctive searches where the target is absent, reaction time increases because the subject has to look at each shape to determine whether it is the target or not because some of the distractors if not all of them, are the same color as the target stimuli. Conjunctive searches where the target is present take less time because if the target is found, the search between each shape stops.[54] Knowledge representation The semantic network of knowledge representation systems have been studied in various paradigms. One of the oldest paradigms is the leveling and sharpening of stories as they are repeated from memory studied by Bartlett. The semantic differential used factor analysis to determine the main meanings of words, finding that the ethical value of words is the first factor. More controlled experiments examine the categorical relationships of words in free recall. The hierarchical structure of words has been explicitly mapped in George Miller's WordNet. More dynamic models of semantic networks have been created and tested with computational systems such as neural networks, latent semantic analysis (LSA), Bayesian analysis, and multidimensional factor analysis. The meanings of words are studied by all the disciplines of cognitive science.[55] |

認知に関する一般的なテスト 直列位置 直列位置効果は、情報が直列的に与えられると、優先効果(primacy effect)と呼ばれる直列の先頭の情報を記憶し、再帰効果(recency effect)と呼ばれる直列の末尾の情報を記憶する傾向がある、という記憶の理論を検証するためのものである。その結果、シーケンスの途中で与えられた 情報は、一般的に忘れ去られるか、容易に想起されない。この研究では、再帰性効果はプライマシー効果よりも強いと予測している。なぜなら、最も最近に学習 された情報は、想起を求められたときにまだワーキングメモリに残っているからである。最初に学習された情報は、まだ検索プロセスを経なければならない。こ の実験は人間の記憶プロセスに焦点を当てている[50]。 単語の優越性 単語の優越性効果実験は、被験者に単語、または文字単体を40ミリ秒という短い時間提示し、その後、単語の特定の位置にあった文字を想起するよう求めるも のである。理論的には、その文字が単独で提示された場合よりも、単語中に提示された場合の方が、被験者はその文字を正しく想起できるはずである。この実験 は人間の音声と言語に焦点を当てている[51]。 ブラウン・ピーターソン ブラウン・ピーターソンのコホモロジー実験では、被験者に三角形が短時間提示され、実験の個別主義バージョンでは、次に、一連の単語が実際に単語なのか、 (スペルミスなどによる)非単語なのかを識別するよう求める注意散漫課題が与えられる。注意散漫課題の後、注意散漫課題の前の三段論法を思い出してもら う。理論的には、注意散漫課題が長ければ長いほど、参加者が三項対立文を正しく思い出すのは難しくなる。この実験はヒトの短期記憶に焦点を当てている [52]。 記憶スパン 記憶スパン実験では、各被験者に同じ種類の一連の刺激が提示される;物体を表す単語、数字、似ているように聞こえる文字、似ていないように聞こえる文字で ある。刺激が提示された後、被験者は与えられた一連の刺激を正確に順番に思い出すよう求められる。ある個別バージョンの実験では、被験者がリストを正しく 想起した場合、その種類の資料のリストの長さが1つ増え、誤って想起した場合はその逆となった。理論的には、人の記憶スパンは数字で約7項目、似て非なる 音の文字や短い単語でも同じである。記憶スパンは、音が似ている文字や長い単語では短くなると予測されている[53]。 視覚的探索 視覚的探索実験の1つのバージョンでは、参加者は、丸と四角が散在して表示されたウィンドウを提示される。参加者は、窓の上に緑の円があるかどうかを識別 する。特徴的探索では、被験者には、青い四角または丸と1つの緑の丸、あるいは緑の丸がまったくない複数の試行ウィンドウが提示される。結合的探索では、 被験者には青い丸または緑の四角と、その存在を識別するよう求められる緑の丸があるかないかの試行ウィンドウが提示される。期待されるのは、特徴探索で は、反応時間、つまり参加者が緑の丸があるかないかを識別するのにかかる時間は、注意散漫の数が増えても変わらないはずだということである。ターゲットが 存在しない接続検索は、ターゲットが存在する接続検索よりも反応時間が長くなるはずである。理論的には、特徴的な検索では、ターゲットと注意散漫なものの 色が異なるので、ターゲットを見つけるのは簡単である。ターゲットが存在しない接続的探索では、すべてではないにせよ、散漫な刺激の一部がターゲット刺激 と同じ色であるため、被験者はターゲットかどうかを判断するためにそれぞれの形状を見なければならず、反応時間が長くなる。標的が存在する接続的探索で は、標的が見つかれば各形状間の探索が停止するため、反応時間が短くなる[54]。 知識表現 知識表現システムの意味ネットワークは様々なパラダイムで研究されてきた。最も古いパラダイムの一つは、バートレットによって研究された、記憶から繰り返 されるストーリーの平準化と鮮明化である。セマンティック・ディファレンシャルは因子分析を使って単語の主な意味を決定し、単語の倫理的価値が第一因子で あることを発見した。より統制された実験では、自由想起における単語のカテゴリー的関係が検討されている。ジョージ・ミラーのワードネットでは、単語の階 層構造が明示的にマッピングされている。意味ネットワークのより動的なモデルは、ニューラルネットワーク、潜在意味分析(LSA)、ベイズ分析、多次元因 子分析などの計算システムで作成され、テストされている。言葉の意味は認知科学のあらゆる分野で研究されている[55]。 |

| Metacognition This section is an excerpt from Metacognition.[edit]  Metacognition and self directed learning Metacognition is an awareness of one's thought processes and an understanding of the patterns behind them. The term comes from the root word meta, meaning "beyond", or "on top of".[56] Metacognition can take many forms, such as reflecting on one's ways of thinking, and knowing when and how oneself and others use particular strategies for problem-solving.[56][57] There are generally two components of metacognition: (1) cognitive conceptions and (2) cognitive regulation system.[58][59] Research has shown that both components of metacognition play key roles in metaconceptual knowledge and learning.[60][61][59] Metamemory, defined as knowing about memory and mnemonic strategies, is an important aspect of metacognition.[62] Writings on metacognition date back at least as far as two works by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC): On the Soul and the Parva Naturalia.[63] |

メタ認知 このセクションはメタ認知からの抜粋である[編集]。  メタ認知と自己指示学習 メタ認知とは、自分の思考プロセスを認識し、その背後にあるパターンを理解することである。メタ認知は、自分の思考方法を振り返ったり、自分自身や他人が 問題解決のためにいつ、どのように個別主義を使うかを知るなど、様々な形をとることができる[56]。 [56][57]メタ認知には一般的に(1)認知的概念と(2)認知的調節システムという2つの構成要素がある[58][59]。メタ認知の両構成要素が メタ認知的知識と学習において重要な役割を果たすことが研究によって示されている[60][61][59]。記憶とニーモニック戦略について知ることと定 義されるメタ記憶はメタ認知の重要な側面である[62]。 メタ認知に関する著作は、少なくともギリシャの哲学者アリストテレス(紀元前384-322年)の2つの著作にまで遡る: それは『魂について』と『博物学』である[63]。 |

| Improving cognition Main article: Nootropic Physical exercise Aerobic and anaerobic exercise have been studied concerning cognitive improvement.[64] There appear to be short-term increases in attention span, verbal and visual memory in some studies. However, the effects are transient and diminish over time, after cessation of the physical activity.[65] People with Parkinson's disease have also seen improved cognition while cycling, while pairing it with other cognitive tasks.[66] Exercise, even at light intensity, significantly improves general cognition across all populations, with the largest cognitive gains seen from shorter interventions (1–3 months), light to moderate intensity activity.[67] Dietary supplements Studies evaluating phytoestrogen, blueberry supplementation and antioxidants showed minor increases in cognitive function after supplementation but no significant effects compared to placebo.[68][69][70] Another study on the effects of herbal and dietary supplements on cognition in menopause show that soy and Ginkgo biloba supplementation could improve women's cognition.[71] Pleasurable social stimulation Exposing individuals with cognitive impairment (i.e. dementia) to daily activities designed to stimulate thinking and memory in a social setting, seems to improve cognition. Although study materials are small, and larger studies need to confirm the results, the effect of social cognitive stimulation seems to be larger than the effects of some drug treatments.[72] Other methods Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has been shown to improve cognition in individuals without dementia 1 month after treatment session compared to before treatment. The effect was not significantly larger compared to placebo.[73] Computerized cognitive training, utilizing a computer based training regime for different cognitive functions has been examined in a clinical setting but no lasting effects has been shown.[74] |

認知力の向上 主な記事 向精神薬 身体運動 有酸素運動と無酸素運動は、認知の改善に関して研究されている[64]。いくつかの研究では、注意持続時間、言語記憶、視覚記憶の短期的な増加がみられ る。しかし、その効果は一過性であり、身体活動の中止後、時間の経過とともに減少する[65]。パーキンソン病患者もまた、他の認知タスクと組み合わせな がらサイクリングを行っており、認知の改善を認めている[66]。運動は、たとえ軽い強度であっても、すべての集団において一般的な認知を有意に改善し、 短期間の介入(1~3ヵ月)、軽度~中等度の強度の活動で最大の認知改善が認められる[67]。 栄養補助食品 植物性エストロゲン、ブルーベリーサプリメントおよび抗酸化物質を評価した研究では、サプリメント摂取後の認知機能の軽微な増加が示されたが、プラセボと 比較して有意な効果は認められなかった[68][69][70]。更年期の認知に対するハーブおよび栄養補助食品の効果に関する別の研究では、大豆および イチョウ葉のサプリメント摂取が女性の認知を改善しうることが示された[71]。 楽しい社会的刺激 認知障害(すなわち認知症)のある人に、社会的な場で思考や記憶を刺激するようにデザインされた日常的な活動をさせると、認知が改善するようである。研究 資料が少なく、より大規模な研究で結果を確認する必要があるが、社会的認知刺激の効果は、いくつかの薬物治療の効果よりも大きいようである[72]。 その他の方法 経頭蓋磁気刺激(TMS)は、認知症のない人において、治療セッションの1ヵ月後に治療前と比較して認知を改善することが示されている。この効果は、プラ セボと比較して有意に大きいものではなかった[73]。コンピュータを利用した認知訓練は、異なる認知機能に対するコンピュータベースの訓練レジメを利用 するもので、臨床の場で検討されているが、持続的な効果は示されていない[74]。 |

| Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument Cognitive biology Cognitive computing Cognitive holding power Cognitive liberty Cognitive musicology Cognitive psychology Cognitive science Cognitivism Comparative cognition Embodied cognition Cognitive shuffle Information processing technology and aging Mental chronometry – i.e., the measuring of cognitive processing speed Nootropic Outline of human intelligence – a list of traits, capacities, models, and research fields of human intelligence, and more. Outline of thought – a list that identifies many types of thoughts, types of thinking, aspects of thought, related fields, and more. Shared intentionality Sex differences in cognition |

認知能力スクリーニング検査 認知生物学 認知コンピューティング 認知的保持力 認知的自由 認知音楽学 認知心理学 認知科学 認知主義 比較認知 身体化された認知 認知的シャッフル 情報処理技術と加齢 メンタル・クロノメトリー(認知処理速度の測定法 向精神薬 人間の知能の概要 - 人間の知能の特徴、能力、モデル、研究分野などのリスト。 思考の概要 - 多くの種類の思考、思考の種類、思考の側面、関連分野などを特定したリスト。 意図主義の共有 認知における性差 |

| Further reading Ardila A (2018). Historical Development of Human Cognition. A Cultural-Historical Neuropsychological Perspective. Springer. ISBN 978-9811068867. Coren S, Ward LM, Enns JT (1999). Sensation and Perception. Harcourt Brace. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-470-00226-1. Lycan WG, ed. (1999). Mind and Cognition: An Anthology (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. Stanovich, Keith (2009). What Intelligence Tests Miss: The Psychology of Rational Thought. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12385-2. Stix, Gary, "Thinking without Words: Cognition doesn't require language, it turns out" (interview with Evelina Fedorenko, a cognitive neuroscientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), Scientific American, vol. 332, no. 3 (March 2025), pp. 86–88. "[I]n the tradition of linguist Noam Chomsky... we use language for thinking: to think is why language evolved in our species. [However, evidence that thought and language are separate systems is found, for example, by] looking at deficits in different abilities – for instance, in people with brain damage... who have impairments in language – some form of aphasia [ – yet are clearly able to think]." (p. 87.) Conversely, "large language models such as GPT-2... do language very well [but t]hey're not so good at thinking, which... nicely align[s] with the idea that the language system by itself is not what makes you think." (p. 88.) |

さらに読む アルディラ A (2018). 人間の認知の歴史的発展。A Cultural-Historical Neuropsychological Perspective. Springer. ISBN 978-9811068867. Coren S, Ward LM, Enns JT (1999). 感覚と知覚. Harcourt Brace. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-470-00226-1. ライカンWG編 (1999). Mind and Cognition: An Anthology (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. Stanovich, Keith (2009). 知能検査は何をミヘているか:合理的思考の心理学. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12385-2. Stix, Gary, "Thinking without Words: Cognition doesn't require language, it turns out" (interview with Evelina Fedorenko, a cognitive neuroscist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), Scientific American, vol. 332, no. 3 (March 2025), pp.86-88. 「言語学者ノーム・チョムスキーの伝統に従えば、我々は思考するために言語を使う。[しかし、思考と言語が別個のシステムであるという証拠は、例え ば......脳に損傷を受けた人たちのような、言語に障害があり、失語症のような状態でありながら、明らかに思考することができる人たちのような、異な る能力における障害を見ることによって見出される。(p.87.)逆に、「GPT-2のような大規模な言語モデルは...言語は非常によくできるが、思考 はあまり得意ではない。(p. 88.) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognition |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆