アバター

Avatar (computing)

An

avatar in the virtual world Second Life

☆ コンピューティングにおいて、アバターとは、ユーザー、ユーザーのキャラクター、またはペルソナをグラフィカルに表現したものである。アバターは、イン ターネット・フォーラムやその他のオンライン・コミュニティでは二次元のアイコンであり、プロフィール写真、ユーザー写真、または以前はピコン(パーソナ ル・アイコン、あるいは「ピクチャー・アイコン」)としても知られていた。あるいは、アバターはオンラインワールドやビデオゲームで使われるような三次元 モデルの形をとることもあれば、テキストベースのゲームやMUDのような世界で使われるような、グラフィックを持たない想像上のキャラクター[1]の形を とることもある。 アバターラ(/ˈævətɑː)という用語はサンスクリット語に由来し、初期のコンピュータゲームやSF小説家によって採用された。1985年にリチャード・ギャリオットがこの用語を画面上のユーザー表現に拡張し、インターネットフォーラムやMUDで 広く使われるようになった。現在、アバターはソーシャルメディア、バーチャルアシスタント、インスタントメッセージングプラットフォーム、World of WarcraftやSecond Lifeなどのデジタルワールドなど、さまざまなオンライン環境で使われている。アバターは、FacebookやLinkedInのようなプラットフォー ムでよく見られるように、現実の自分のイメージの形をとることもあれば、現実世界とはかけ離れたバーチャルなキャラクターの形をとることもある。多くの場 合、アバターはさまざまな原因への支持を示すためにカスタマイズされたり、ユニークなオンライン上の表現を作り出すために作られたりする。 学術研究は、アバターがコミュニケーション[デザイン]やデジタル・アイデン ティティの結果にどのような影響を与えるかに焦点を当てている。ユーザーは、社会的受容を得たり、社会的相互作用を容易にするために、架空の特徴を持つア バターを採用することができる。しかし、大半のユーザーは現実世界の自分に似たアバターを選ぶという研究結果もある。

| In computing, an

avatar is a graphical representation of a user, the user's character,

or persona. Avatars can be two-dimensional icons in Internet forums and

other online communities, where they are also known as profile

pictures, userpics, or formerly picons (personal icons, or possibly

"picture icons"). Alternatively, an avatar can take the form of a

three-dimensional model, as used in online worlds and video games, or

an imaginary character with no graphical appearance,[1] as in

text-based games or worlds such as MUDs. The term avatāra (/ˈævətɑːr, ˌævəˈtɑːr/) originates from Sanskrit, and was adopted by early computer games and science fiction novelists. Richard Garriott extended the term to an on-screen user representation in 1985, and the term gained wider adoption in Internet forums and MUDs. Nowadays, avatars are used in a variety of online settings including social media, virtual assistants, instant messaging platforms, and digital worlds such as World of Warcraft and Second Life. They can take the form of an image of one's real-life self, as often seen on platforms like Facebook and LinkedIn, or a virtual character that diverges from the real world. Often, these are customised to show support for different causes, or to create a unique online representation. Academic research has focused on how avatars can influence the outcomes of communication and digital identity. Users can employ avatars with fictional characteristics to gain social acceptance or ease social interaction. However, studies have found that the majority of users choose avatars that resemble their real-world selves. |

コンピューティングにおいて、アバターとは、ユーザー、ユーザーのキャ

ラクター、またはペルソナをグラフィカルに表現したものである。アバターは、インターネット・フォーラムやその他のオンライン・コミュニティでは二次元の

アイコンであり、プロフィール写真、ユーザー写真、または以前はピコン(パーソナル・アイコン、あるいは「ピクチャー・アイコン」)としても知られてい

た。あるいは、アバターはオンラインワールドやビデオゲームで使われるような三次元モデルの形をとることもあれば、テキストベースのゲームやMUDのよう

な世界で使われるような、グラフィックを持たない想像上のキャラクター[1]の形をとることもある。 アバターラ(/ˈævətɑː)という用語はサンスクリット語に由来し、初期のコンピュータゲームやSF小説家によって採用された。1985年にリチャー ド・ギャリオットがこの用語を画面上のユーザー表現に拡張し、インターネットフォーラムやMUDで広く使われるようになった。現在、アバターはソーシャル メディア、バーチャルアシスタント、インスタントメッセージングプラットフォーム、World of WarcraftやSecond Lifeなどのデジタルワールドなど、さまざまなオンライン環境で使われている。アバターは、FacebookやLinkedInのようなプラットフォー ムでよく見られるように、現実の自分のイメージの形をとることもあれば、現実世界とはかけ離れたバーチャルなキャラクターの形をとることもある。多くの場 合、アバターはさまざまな原因への支持を示すためにカスタマイズされたり、ユニークなオンライン上の表現を作り出すために作られたりする。 学術研究は、アバターがコミュニケーションやデジタル・アイデンティティの結果にどのような影響を与えるかに焦点を当てている。ユーザーは、社会的受容を 得たり、社会的相互作用を容易にするために、架空の特徴を持つアバターを採用することができる。しかし、大半のユーザーは現実世界の自分に似たアバターを 選ぶという研究結果もある。 |

| Origins See also: Player character The word avatar is ultimately derived from the Sanskrit word (avatāra /ˈævətɑːr, ˌævəˈtɑːr/); in Hinduism, it stands for the "descent" of a deity into a terrestrial form.[2][3] It was first used in a computer game by the 1979 PLATO role-playing game Avatar. In Norman Spinrad's novel Songs from the Stars (1980), the term avatar is used in a description of a computer generated virtual experience. In the story, humans receive messages from an alien galactic network that wishes to share knowledge and experience with other advanced civilizations through "songs". The humans build a "galactic receiver" that allows its users to engage in "artificial realities". One experience is described as such:[4] You stand in a throng of multifleshed being, mind avatared in all its matter, on a broad avenue winding through a city of blue trees with bright red foliage and living buildings growing from the soil in a multitude of forms. The use of the term avatar for the on-screen representation of the user was coined in 1985 by Richard Garriott for the computer game Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar. In this game, Garriott desired the player's character to be their Earth self manifested into the virtual world. Due to the ethical content of his story, Garriott wanted the real player to be responsible for their character; he thought only someone playing "themselves" could be properly judged based on their in-game actions. Because of its ethically nuanced narrative approach, he took the Hindu word associated with a deity's manifestation on earth in physical form, and applied it to a player in the game world.[5] Other early uses of the term include Lucasfilm and Chip Morningstar's 1986 online role-playing game Habitat,[6] and the 1989 pen and paper role-playing game Shadowrun.[citation needed] The use of avatar to mean online virtual bodies was popularised by Neal Stephenson in his 1992 cyberpunk novel Snow Crash.[7] In Snow Crash, the term avatar was used to describe the virtual simulation of the human form in the Metaverse, a fictional virtual-reality application on the Internet. Social status within the Metaverse was often based on the quality of a user's avatar, as a highly detailed avatar showed that the user was a skilled hacker and programmer while the less talented would buy off-the-shelf models in the same manner a beginner would today. Stephenson wrote in the "Acknowledgments" to Snow Crash: The idea of a "virtual reality" such as the Metaverse is by now widespread in the computer-graphics community and is being used in a number of different ways. The particular vision of the Metaverse as expressed in this novel originated from idle discussion between me and Jaime (Captain Bandwidth) Taaffe ... The words avatar (in the sense used here) and Metaverse are my inventions, which I came up with when I decided that existing words (such as virtual reality) were simply too awkward to use ... after the first publication of Snow Crash, I learned that the term avatar has actually been in use for a number of years as part of a virtual reality system called Habitat...in addition to avatars, Habitat includes many of the basic features of the Metaverse as described in this book.[8] |

オリジン こちらも参照のこと: プレイヤーキャラクター アバターという言葉は最終的にサンスクリット語(avatāra /ˈævətɑː)に由来し、ヒンドゥー教では神が地上の姿に「降臨」することを意味する[2][3]。 コンピュータゲームで初めて使われたのは1979年のPLATOロールプレイングゲーム『アバター』である。ノーマン・スピンラッドの小説『Songs from the Stars』(1980年)では、アバターという用語がコンピュータが生成した仮想体験の説明の中で使われている。この物語の中で人間は、「歌」を通じて 他の先進文明と知識や経験を共有することを望む異星人の銀河系ネットワークからのメッセージを受け取る。人類は、ユーザーが「人工現実」に参加できる「銀 河受信機」を作る。ある体験は次のように説明されている[4]。 真っ赤な葉を茂らせた青い木々が生い茂り、土の中から生きている建物がマルチチュードで生えている都市の中を曲がりくねった大通りに、あらゆる物質で心をアバター化された多肉植物の群れの中に立っている。 アバターという用語が画面上のユーザーの表現に使われるようになったのは、1985年、リチャード・ギャリオットがコンピューターゲーム『ウルティマ IV:クエスト・オブ・ザ・アバター』のために作った造語である。このゲームにおいて、ギャリオットはプレイヤーのキャラクターを、仮想世界に現れた地球 人であることを望んだ。そのストーリーの倫理的な内容から、ギャリオットは現実のプレイヤーが自分のキャラクターに責任を持つことを望んだ。彼は「自分自 身」を演じている人だけが、ゲーム内での行動に基づいて適切に判断されると考えたのだ。その倫理的なニュアンスの物語的アプローチのため、彼は神が物理的 な形で地上に現れることに関連するヒンドゥー語を取り上げ、ゲーム世界のプレイヤーに適用した[5]。この用語の他の初期の使用には、ルーカスフィルムと チップ・モーニングスターによる1986年のオンライン・ロールプレイング・ゲーム『ハビタット』[6]、1989年のペンと紙のロールプレイング・ゲー ム『シャドウラン』などがある[要出典]。 1992年のサイバーパンク小説『スノウ・クラッシュ』では、ニール・スティーヴンソンによってオンライン上の仮想身体を意味するアバターの使用が一般化 された[7]。『スノウ・クラッシュ』では、アバターという用語はインターネット上の架空の仮想現実アプリケーションであるメタバースにおける人間の姿の 仮想シミュレーションを表すために使用された。メタバース内での社会的地位は、しばしばユーザーのアバターの質に基づいていた。高度に詳細なアバターは、 そのユーザーが熟練したハッカーやプログラマーであることを示す一方で、才能のないユーザーは、今日初心者がするのと同じように、既製のモデルを購入し た。スティーブンソンは『スノウ・クラッシュ』の「謝辞」にこう書いている: メタヴァースのような 「仮想現実 」のアイデアは、今やコンピューターグラフィックス界に広く浸透し、さまざまな方法で利用されている。この小説で表現されているメタバースの個別主義は、 私とハイメ(帯域幅キャプテン)・タフとの漫然とした議論に端を発している。アバター(ここで使われている意味での)とメタバースという言葉は私の発明で あり、既存の言葉(バーチャルリアリティなど)は単に使いにくすぎると判断したときに思いついたものである......『スノウ・クラッシュ』の最初の出 版後、アバターという言葉が実はハビタットというバーチャルリアリティシステムの一部として何年も前から使われていることを知った......アバターに 加え、ハビタットには本書で説明されているメタバースの基本的な機能の多くが含まれている[8]。 |

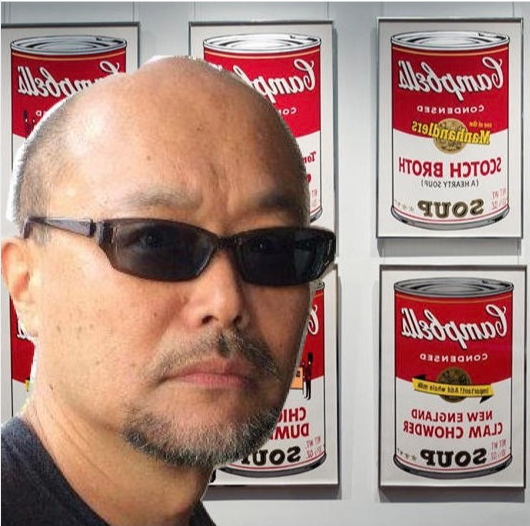

| Types and usage This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Avatar" computing – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  2016 Facebook post from Barack Obama, with his photo next to his name at the top of the post An avatar can refer to a two-dimensional picture akin to an icon in Internet forums and other online communities.[9][10] This is also known as a profile picture or userpic, or in early Internet parlance, a 'picon' (personal icon).[11] With the advent of social media platforms like Facebook, where users are not typically anonymous, these pictures often are a photo of the user in real life.[12][13] Alternatively, avatars can also be three-dimensional digital representations, as in games such as World of Warcraft or virtual worlds like Second Life.[14][15] In MUDs and other early systems, they were a construct composed of text.[16] The term has been also sometimes extended to refer to the personality connected with the screen name, or handle, of an Internet user.[17] |

種類と使用法 このセクションの検証には追加の引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは、異議申し立てがなされ削除されることがある。 出典を探す 「Avatar" computing - news - newspapers - books - scholar - JSTOR (November 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) (このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)  2016年のバラク・オバマのFacebookの投稿、投稿上部の名前の横に彼の写真がある アバターとは、インターネット・フォーラムやその他のオンライン・コミュニティにおけるアイコンのような二次元の写真を指すことがある[9][10]。こ れはプロフィール写真やユーザー写真、あるいは初期のインターネット用語では「ピコン」(人格アイコン)としても知られている[11]。フェイスブックの ようなソーシャルメディア・プラットフォームの出現により、ユーザーは通常匿名ではないため、これらの写真はしばしば現実のユーザーの写真である[12] [13]。 また、アバターは、World of WarcraftのようなゲームやSecond Lifeのような仮想世界のように、3次元のデジタル表現であることもある[14][15]。 MUDや他の初期のシステムでは、アバターはテキストで構成された構成物であった[16]。 この用語は、インターネットユーザーのスクリーンネームやハンドルネームに関連する人格を指すように拡張されることもある[17]。 |

| Internet forums Despite the widespread use of avatars, it is unknown which Internet forums were the first to use them; the earliest forums did not include avatars as a default feature, and they were included in unofficial "hacks" before eventually being made standard. Avatars on Internet forums serve the purpose of representing users and their actions, personalizing their contributions to the forum, and may represent different parts of their persona, beliefs, interests or social status in the forum.  Example of an avatar image on an internet forum The traditional avatar system used on most Internet forums is a small (80x80 to 100x100 pixels, for example) square-shaped area close to the user's forum post, where the avatar is placed in order for other users to easily identify who has written the post without having to read their username. Some forums allow the user to upload an avatar image that may have been designed by the user or acquired from elsewhere. Other forums allow the user to select an avatar from a preset list or use an auto-discovery algorithm to extract one from the user's homepage. Some avatars are animated, consisting of a sequence of multiple images played repeatedly. In such animated avatars, the number of images as well as the time in which they are replayed vary considerably.[18] Other avatar systems exist, such as on Gaia Online, WeeWorld, Frenzoo or Meez, where a pixelized representation of a person or creature is used, which can then be customized to the user's wishes.[19] There are also avatar systems (e.g. Trutoon) where a representation is created using a person's face with customized characters and backgrounds. Another avatar-based system is one wherein an image is automatically generated based on the identity of the poster. Identicons are formed as visually distinct geometric images derived from a digest hash of the poster's IP address or user ID. These serve as a means to associate a particular user with a particular geometric representation. When used with an IP address, a particular anonymous user can be visually identified without the need for registration or authentication. If an account is compromised, a dissimilar identicon will be formed as the attacker is posting from an unfamiliar IP address.[20][21] Internet chat and messaging GIF avatars were introduced as early as 1990 in the ImagiNation Network (also known as Sierra On-Line) game and chat hybrid. In 1994, Virtual Places offered VOIP capabilities which were later abandoned for lack of bandwidth. In 1996 Microsoft Comic Chat, an IRC client that used cartoon avatars for chatting, was released. America Online introduced instant messaging for its membership in 1996 and included a limited number of "buddy icons," picking up on the avatar idea from PC games. When AOL later introduced the free version of its messenger, AIM, for use by anyone on the Internet, the number of icons offered grew to be more than 1,000 and the use of them grew exponentially, becoming a hallmark feature of instant messaging. In 2002, AOL introduced "Super Buddies," 3D animated icons that talked to users as they typed messages and read messages. The term Avatar began to replace the moniker of "buddy icon" as 3D customizable icons became known to its users from the mainstream popularity of PC Games. Yahoo's instant messenger was the first to adopt the term "avatar" for its icons. Instant messaging avatars were usually very small; AIM icons have been as small as 16×16 pixels but are used more commonly at the 48×48 pixel size, although many icons can be found online that typically measure anywhere from 50×50 pixels to 100×100 pixels in size. More recently, services such as Discord have added avatars. With a paid subscription, users can select individual identities for different communities.[22] |

インターネットフォーラム アバターが広く使われているにもかかわらず、どのインターネット・フォーラムが最初にアバターを使用したかは不明である。初期のフォーラムにはデフォルト 機能としてアバターは含まれておらず、非公式な「ハック」に含まれていたが、最終的に標準化された。インターネット・フォーラムにおけるアバターは、ユー ザーとその行動を表し、フォーラムへの投稿を個人化するという目的を果たし、フォーラムにおける人格、信念、興味、社会的地位の異なる部分を表すことがあ る。  インターネットフォーラムのアバター画像の例 ほとんどのインターネット・フォーラムで使用されている伝統的なアバター・システムは、ユーザーのフォーラム投稿の近くに小さな(例えば80x80から 100x100ピクセル)正方形の形をした領域があり、他のユーザーがユーザー名を読まなくても誰がその投稿を書いたかを簡単に識別できるようにアバター が配置されている。一部のフォーラムでは、ユーザーがアバター画像をアップロードすることができる。アバター画像は、ユーザーがデザインしたものでも、他 の場所から入手したものでもよい。他のフォーラムでは、ユーザーがあらかじめ設定されたリストからアバターを選択したり、自動検出アルゴリズムを使って ユーザーのホームページからアバターを抽出したりすることができる。 アバターの中には、繰り返し再生される複数の画像のシーケンスで構成されるアニメーションもある。このようなアニメーションアバターでは、画像の数や再生される時間はかなり異なる[18]。 他のアバターシステムは、Gaia Online、WeeWorld、Frenzoo、Meezなどに存在し、人物や生物のピクセル化された表現が使用され、ユーザーの希望に応じてカスタマイズすることができる[19]。 もう1つのアバターベースのシステムは、投稿者のIDに基づいて画像が自動的に生成されるものである。アイコンは、投稿者のIPアドレスまたはユーザー IDのダイジェスト・ハッシュから得られる、視覚的に明確な幾何学的画像として形成される。これらは、特定のユーザーと特定の幾何学的表現を関連付ける手 段として機能する。IPアドレスとともに使用されると、登録や認証を必要とせずに、特定の匿名ユーザーを視覚的に識別することができる。アカウントが侵害 された場合、攻撃者は見慣れないIPアドレスから投稿しているため、類似しないidenticonが形成される[20][21]。 インターネットチャットとメッセージング GIFアバターは早くも1990年にImagiNation Network(Sierra On-Lineとしても知られる)のゲームとチャットのハイブリッドで導入された。1994年、Virtual PlacesはVOIP機能を提供したが、後に帯域幅不足のために放棄された。1996年には、漫画のアバターを使ってチャットするIRCクライアント、 Microsoft Comic Chatがリリースされた。 アメリカ・オンラインは1996年に会員制のインスタント・メッセージングを導入し、PCゲームのアバターのアイデアを取り入れて、限られた数の「バ ディ・アイコン」を搭載した。その後、AOLがインターネット上で誰でも使える無料版のメッセンジャー、AIMを導入すると、提供されるアイコンの数は 1,000以上に増え、その利用は飛躍的に拡大し、インスタント・メッセージングの特徴的な機能となった。2002年、AOLは「スーパーバディ」と呼ば れる3Dアニメーションのアイコンを導入し、ユーザーがメッセージを入力したり、メッセージを読んだりするときに話しかけてくるようになった。3Dでカス タマイズ可能なアイコンは、PCゲームの主流からユーザーに知られるようになり、アバターという言葉は「バディアイコン」という呼び名に取って代わり始め た。ヤフーのインスタントメッセンジャーは、アイコンに「アバター」という言葉を採用した最初のメッセンジャーだった。AIMのアイコンは16×16ピク セルと小さかったが、一般的には48×48ピクセルのサイズで使われている。 最近では、Discordなどのサービスにもアバターが追加された。有料のサブスクリプションを利用すれば、ユーザーは異なるコミュニティ用に個別のアイデンティティを選択できる[22]。 |

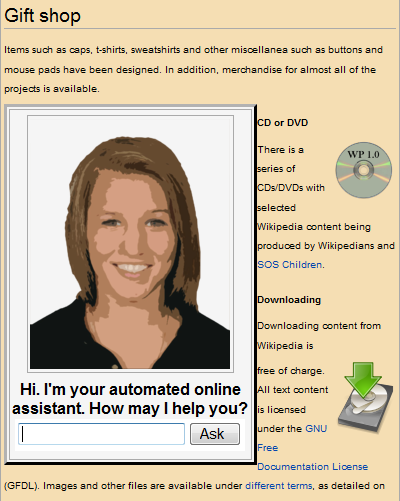

Online assistants An avatar used by an automated online assistant providing customer service on a web page Avatars can be used as virtual embodiments of embodied agents, which are driven more or less by artificial intelligence rather than real people. Automated online assistants are examples of avatars used in this way. Such avatars are used by organizations as a part of automated customer services in order to interact with consumers and users of services. This can avail for enterprises to reduce their operating and training cost.[23] A major underlying technology to such systems is natural language processing.[23] Some of these avatars are commonly known as "bots". Famous examples include IKEA's Anna, an avatar designed to guide users around the IKEA website. Such avatars can also be powered by a digital conversation which provides a little more structure than those using NLP, offering the user options and clearly defined paths to an outcome. This kind of avatar is known as a Structured Language Processing or SLP Avatar. |

オンラインアシスタント ウェブページ上で顧客サービスを提供する自動オンラインアシスタントが使用するアバター アバターは、多かれ少なかれ、実際の人間ではなく人工知能によって動かされる、具現化されたエージェントの仮想的な具現化として使用することができる。自動化されたオンラインアシスタントは、この方法で使用されるアバターの例である。 このようなアバターは、消費者やサービスの利用者と対話するために、自動化された顧客サービスの一部として企業によって使用される。このようなシステムの 主要な基礎技術は、自然言語処理である。有名な例としては、IKEAのAnnaが挙げられる。Annaは、IKEAのウェブサイト内でユーザーを案内する ためにデザインされたアバターである。 このようなアバターは、NLPを使用するものよりももう少し構造を提供し、ユーザーに選択肢を提供し、結果への道筋を明確に定義するデジタル会話によって動くこともできる。この種のアバターは、構造化言語処理またはSLPアバターとして知られている。 |

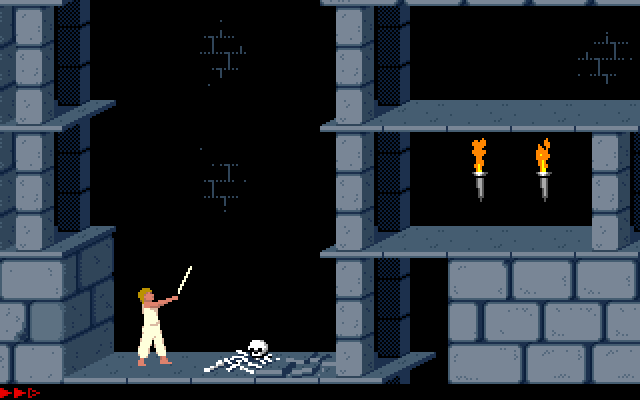

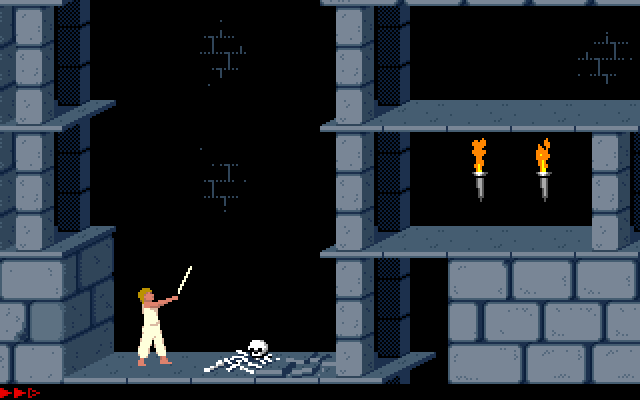

| Video games Main article: Player character  The player character picks up a sword in the 1989 video game Prince of Persia Avatars in video games are the player's representation in the game world. The first video games to include a representation of the player were Basketball (1974) which represented players as humans,[24][25] and Maze War (1974) which represented players as eyeballs.[26] In some games, the player's representation is fixed, however many games offer a basic character model, or template, and then allow customization of the physical features as the player sees fit. For example, Carl Johnson, the avatar from Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, can be dressed in a wide range of clothing, can be given tattoos and haircuts, and can even body build or become obese depending upon player actions.[27] One video game in which the avatar and player are two separate entities is the game Perspective, where the player controls both themself in a 3-dimensional world and the avatar in a 2-dimensional world. Aside from an avatar's physical appearance, its dialogue, particularly in cutscenes, may also reveal something of its character. A good example is the crude, action hero stereotype, Duke Nukem.[28] Other avatars, such as Gordon Freeman from Half-Life, who never speaks at all, reveal very little of themselves (the original game never showed the player what he looked like without the use of a console command for third-person view). Many Massively multiplayer online games (MMOGs) also include customizable avatars. Customization levels differ between games; for instance, in EVE Online, players construct a wholly customized portrait, using a software that allows for several changes to facial structure as well as preset hairstyles, skin tones, etc.[18] However, these portraits appear only in in-game chats and static information view of other players. Usually, all players appear in gigantic spacecraft that give no view of their pilot, unlike in most other RPGs. Alternatively, City of Heroes offers one of the most detailed and comprehensive in-game avatar creation processes, allowing players to construct anything from traditional superheroes to aliens, medieval knights, monsters, robots, and many more. Robbie Cooper's 2007 book "Alter Ego, Avatars and their creators" pairs photographs of players of a variety of MMO's with images of their in-game avatars and profiles; recording the player's motivations and intentions in designing and using their avatars. The survey reveals wide variation in the ways in which players of MMO's use avatars.[29] Felicia Day, creator and star of The Guild web series, created a song called "(Do You Wanna Date My) Avatar" which satirizes avatars and virtual dating. |

ビデオゲーム 主な記事 プレイヤーキャラクター  1989年のビデオゲーム「プリンス・オブ・ペルシャ」で剣を手にするプレイヤーキャラクター。 ビデオゲームにおけるアバターは、ゲーム世界におけるプレイヤーの表現である。プレイヤーを表現した最初のビデオゲームは、プレイヤーを人間として表現し た『バスケットボール』(1974年)と[24][25]、プレイヤーを目玉として表現した『メイズウォー』(1974年)である[26]。 ゲームによっては、プレイヤーの表現は固定されているが、多くのゲームでは基本的なキャラクターモデル(テンプレート)が用意されており、プレイヤーの好 みで身体的特徴をカスタマイズできるようになっている。例えば、『グランド・セフト・オート:サンアンドレアス』のアバターであるカール・ジョンソンは、 さまざまな服装に身を包むことができ、タトゥーやヘアカットを施し、プレイヤーの行動次第で体格を良くしたり肥満になったりすることもできる[27]。ア バターとプレイヤーが2つの別個の存在であるビデオゲームの1つに、プレイヤーが3次元世界の自分と2次元世界のアバターの両方を操作するゲーム『パース ペクティブ』がある。 アバターの外見だけでなく、セリフ、特にカットシーンでその性格が明らかになることもある。その良い例が、粗野でアクションヒーローのステレオタイプであ るデューク・ヌケムである[28]。他のアバター、例えば『Half-Life』のゴードン・フリーマンは全く喋らず、人格をほとんど明らかにしない(オ リジナルのゲームでは、三人称視点用のコンソールコマンドを使わない限り、プレイヤーに彼の姿を見せることはなかった)。 多人数同時参加型オンラインゲーム(MMOG)の多くにも、カスタマイズ可能なアバターがある。カスタマイズのレベルはゲームによって異なる。例えば、 EVE Onlineでは、プレイヤーはプリセットのヘアスタイルや肌の色などに加えて、顔の構造をいくつか変更できるソフトウェアを使用して、完全にカスタマイ ズされたポートレートを構築する[18]。通常、すべてのプレイヤーは巨大な宇宙船に乗っており、他の多くのRPGとは異なり、パイロットの姿は見えな い。代わりに、『シティ・オブ・ヒーローズ』では最も詳細かつ包括的なゲーム内アバター作成プロセスが用意されており、プレイヤーは伝統的なスーパーヒー ローからエイリアン、中世の騎士、モンスター、ロボットなど、あらゆるものを作ることができる。ロビー・クーパーの2007年の著書「アルターエゴ、アバ ターとその作成者」は、さまざまなMMOのプレイヤーの写真と、ゲーム内のアバターやプロフィールの画像を対にしており、アバターをデザインしたり使用し たりする際のプレイヤーの動機や意図主義を記録している。この調査では、MMOのプレイヤーのアバターの使い方は千差万別であることが明らかになった [29]。ギルドのウェブ・シリーズのクリエイター兼スターであるフェリシア・デイは、アバターとバーチャル・デートを風刺した「(Do You Wanna Date My) Avatar」という曲を作った。 |

A Xbox 360 avatar A Nintendo Mii avatar Universal animated avatars from the Xbox 360 (shown left) and Nintendo Wii (shown right) Nintendo's Wii, 3DS and Switch consoles allow for the creation of avatars called "Miis" that take the form of stylized, cartoonish people and can be used in some games as avatars for players, as in Wii Sports.[30][31] In some games, the ability to use a Mii as an avatar must be unlocked, such as in Mario Kart 8.[32] In late 2008, Microsoft released an Xbox 360 Dashboard update which featured the introduction of Avatars as part of the console's New Xbox Experience.[33] With the update installed users can personalize the look of their Avatars by choosing from a range of clothing and facial features. In October 2018, Microsoft launched a new version of their Xbox avatars for Xbox One and Xbox on Windows 10, featuring increased detail and having a focus on inclusivity.[34] PlayStation Home for Sony's PlayStation 3 console also featured the use of avatars, but with a more realistic style than Nintendo's Miis or Microsoft's Avatars.[35] |

Xbox 360のアバター 任天堂のMiiアバター Xbox 360(左)と任天堂Wii(右)のユニバーサルアニメーションアバター 任天堂のWii、3DS、Switchコンソールでは、様式化された漫画のような人物の形をした「Mii」と呼ばれるアバターを作成することができ、 『Wii Sports』のようにプレイヤーのアバターとして一部のゲームで使用することができる[30][31]。一部のゲームでは、『マリオカート8』のように Miiをアバターとして使用する機能をアンロックする必要がある[32]。 2008年後半、マイクロソフトはXbox 360のダッシュボードアップデートをリリースし、コンソールのNew Xbox Experienceの一部としてアバターを導入した[33]。アップデートをインストールすると、ユーザーはさまざまな服装や顔の特徴から選択すること で、アバターの外観をパーソナライズすることができる。2018年10月、マイクロソフトはXbox OneとXbox on Windows 10向けにXboxアバターの新バージョンを発表し、ディテールを増やし、包括性に重点を置いていることを特徴とした[34]。ソニーの PlayStation 3コンソール向けのPlayStation Homeもアバターの使用を特徴としたが、任天堂のMiやマイクロソフトのアバターよりもリアルなスタイルであった[35]。 |

| Non-gaming online worlds Avatars in non-gaming online worlds are used as two- or three-dimensional human or fantastic representations of a person's inworld self. Such representations are a tool which facilitates the exploration of the virtual universe, or acts as a focal point in conversations with other users, and can be customized by the user. Usually, the purpose and appeal of such universes is to provide a large enhancement to common online conversation capabilities, and to allow the user to peacefully develop a portion of a non-gaming universe without being forced to strive towards a pre-defined goal.[36]  Avatars socialising in the 2003 virtual world Second Life The earliest avatars of this form were text-based descriptions employed by players within MUDs. These often allowed players to express an identity disparate from their public one within an interactive environment. For instance, LambdaMOO allowed a choice of 11 different genders, which could be changed at the user's will.[14] The visually-based game Habitat also used the term to refer to players within the game world. A later example is Linden Lab's Second Life, which has the player use a custom avatar to interact in a virtual 3D world; after peaking in 2007, its user count declined due to the encroachment of more traditional platforms such as Facebook. More recently, the concept has been combined with virtual reality; VRChat allows the user to interact with other avatars in custom environments, and Mark Zuckerberg's Meta Platforms has promoted it as part of his vision of a metaverse.[37][38] Many modern virtual worlds provide users with advanced tools to customize their representations, allowing them to change shapes, hair, skins and also genre. Moreover, there is a secondary industry devoted to the creations of products and items for the avatars. Some companies have also launched social networks[39] and other websites for avatars such as Koinup, Myrl, and Avatars United. Lisa Nakamura has suggested that customizable avatars in non-gaming worlds tend to be biased towards lighter skin colors and against darker skin colors, especially in those of the male gender.[40] In Second Life avatars are created by residents and take any form, and range from lifelike humans to robots, animals, plants and legendary creatures. Avatar customization is one of the most important entertainment aspects in non gaming virtual worlds, such as Second Life, IMVU, and Active Worlds.[41] Some evidence suggests that avatars that are more anthropomorphic are perceived to be less credible and likeable than images that are less anthropomorphic.[j 1] Social scientists at Stanford's Virtual Human Interaction Lab[42] examine the implications, possibilities, and transformed social interaction that occur when people interact via avatars. |

ノンゲーム・オンライン・ワールド ゲーム以外のオンライン・ワールドにおけるアバターは、2次元または3次元の人間またはファンタジーの表現として、その人格のインワールドでの自己表現と して使用される。このような表現は、仮想世界の探索を容易にしたり、他のユーザーとの会話で中心的な役割を果たすツールであり、ユーザーによってカスタマ イズすることができる。通常、このようなユニバースの目的と魅力は、一般的なオンライン会話機能を大幅に強化し、ユーザーがあらかじめ定義された目標に向 かって努力することを強いられることなく、非ゲームユニバースの一部を平和的に発展させることができるようにすることである[36]。  2003年の仮想世界Second Lifeで社交するアバター この形式の最も初期のアバターは、MUD内でプレイヤーが使用するテキストベースの記述であった。これによって、プレイヤーはしばしば、インタラクティブ な環境の中で、公的なものとは異なるアイデンティティを表現することができた。例えば、LambdaMOOでは11種類の性別を選択することができ、ユー ザーの意志で変更することができた[14]。また、視覚ベースのゲームであるHabitatでも、ゲーム世界内のプレイヤーを指す言葉として使用されてい た。後の例としては、リンデンラボのセカンドライフがあり、プレイヤーはカスタムアバターを使って仮想3D世界で交流する。2007年にピークを迎えた 後、フェイスブックなどのより伝統的なプラットフォームの侵食によりユーザー数は減少した。より最近では、このコンセプトは仮想現実と組み合わされてい る。VRChatは、ユーザがカスタム環境で他のアバターと交流することを可能にし、マーク・ザッカーバーグのMeta Platformsは、メタヴァースのビジョンの一部としてこれを推進している[37][38]。 現代の仮想世界の多くは、ユーザーが自分の表現をカスタマイズするための高度なツールを提供し、形、髪、スキン、またジャンルを変えることを可能にしてい る。さらに、アバターのための製品やアイテムの制作に専念する第二次産業も存在する。Koinup、Myrl、Avatars Unitedなど、アバターのためのソーシャルネットワーク[39]やその他のウェブサイトを立ち上げている企業もある。 リサ・ナカムラは、ゲーム以外の世界でカスタマイズ可能なアバターは、肌の色が明るい方に偏り、肌の色が暗い方、特に男性のものに偏る傾向があることを示 唆している[40]。セカンドライフのアバターは住人によって作成され、あらゆる形をとり、本物そっくりの人間からロボット、動物、植物、伝説上の生き物 までさまざまである。アバターのカスタマイズは、Second Life、IMVU、Active Worldsのようなゲーム以外の仮想世界では最も重要なエンターテイメントの一つである[41]。 |

| Social media Another use of the avatar has emerged with the widespread use of social media platforms. There is a practice in social media sites: uploading avatars in place of real profile image. Profile picture is a distinct graphics that represent the identity of profile holder. It is usually the portrait of an individual, logo of an organization, organizational building or distinctive character of book, cover page etc. Using avatars as profile pictures can increase users' perceived level of social presence which in turn fosters reciprocity and sharing behavior in online environments.[43] According to MIT professor Sherry Turkle: "... we think we will be presenting ourselves, but our profile ends up as somebody else – often the fantasy of who we want to be".[44] Motion capture Another form of use for avatars is for video chats/calls. Some services, such as Skype (through some external plugins) allow users to use talking avatars during video calls, replacing the image from the user's camera with an animated, talking avatar.[45] Through the use of facial motion capture and a webcam, an avatar can be configured to mimic the motions and expressions of the user. This can be integrated directly into games, such as Star Citizen, and via standalone software such as FaceRig.[46][47] Both 3D and 2D avatars have been used in Learning and Development content for education, onboarding, employee training and more. Photorealistic 3D AI avatars have been used as stand-ins for real actors via video editing tools like those made by Synthesia among others.[48] Virtual YouTubers use animated avatars designed in software such as Live2D, which often resemble anime characters.[49] A whole ecosystem of talent agencies and investors exists to manage these online personalities, which often differ from the creator's real-life persona.[50] YouTube's 2020 Culture and Trends report highlighted VTubers as one of the notable trends of that year, with 1.5 billion views per month by October,[51] and in May 2021, Twitch added a VTuber tag for streams as part of a wider expansion of its tag system.[52] Miscellaneous Samsung's AR Emoji which comes on Samsung Galaxy smartphones lets users create animated avatars of themselves.[53][54] In popular culture Cartoons and stories sometimes have a character based on their creator, either a fictionalised version (e.g. the Matt Groening character in some episodes of The Simpsons) or an entirely fictional character (e.g. Hermione Granger in the Harry Potter series has been said[55] by J. K. Rowling to be based upon herself). Such characters are sometimes known as "author surrogates", "author avatars" or Self Inserts[56]. |

ソーシャルメディア ソーシャルメディア・プラットフォームの普及に伴い、アバターのもう一つの使い方が登場した。ソーシャルメディアサイトでは、実際のプロフィール画像の代 わりにアバターをアップロードするという慣習がある。プロフィール画像は、プロフィール保持者のアイデンティティを表す明確なグラフィックである。それは 通常、個人の肖像画、組織のロゴ、組織の建物、本の特徴的なキャラクター、表紙などである。プロフィール画像としてアバターを使用することで、ユーザーの 社会的存在感を高めることができ、オンライン環境における互恵性と共有行動が促進される[43]: 「......私たちは自分自身を提示するつもりだが、プロフィールは結局別の誰かになってしまう。 モーションキャプチャー アバターのもう一つの用途は、ビデオチャット/通話である。Skypeのようないくつかのサービスでは(外部プラグインを通じて)、ビデオ通話中にしゃべ るアバターを使うことができる。これはStar Citizenのようなゲームに直接統合することも、FaceRigのようなスタンドアローンのソフトウェアを介して統合することもできる[46] [47]。 3Dアバターと2Dアバターの両方が、教育、オンボーディング、従業員トレーニングなどの学習開発コンテンツに使用されている。フォトリアリスティックな 3D AIアバターは、Synthesia社製などのビデオ編集ツールを介して、本物の俳優の代役として使用されている[48]。 バーチャルYouTuberは、Live2Dなどのソフトウェアでデザインされたアニメーションのアバターを使用しており、アニメのキャラクターに似てい ることが多い[49]。これらのオンライン人格を管理するタレントエージェンシーや投資家のエコシステム全体が存在し、クリエイターの現実の人格とは異な ることが多い。 [50]YouTubeの2020年のカルチャーとトレンドのレポートでは、その年の注目すべきトレンドの一つとしてVTuberが取り上げられており、 10月までに月間15億ビューを記録している[51]。 その他 サムスンのGalaxyスマートフォンに搭載されているサムスンのAR Emojiは、ユーザーが自分自身のアニメーションアバターを作成することができる[53][54]。 大衆文化 漫画や物語には、その作者に基づいたキャラクターが登場することがある。架空の人物(例えば、『ザ・シンプソンズ』のいくつかのエピソードに登場するマッ ト・グルーニングのキャラクター)や、完全に架空のキャラクター(例えば、『ハリー・ポッター』シリーズのハーマイオニー・グレンジャーは、J・K・ロー リングが自分自身をモデルにしていると語っている[55])。このようなキャラクターは、「作者サロゲート」、「作者アバター」、または「自己挿入」 [56]として知られることがある。 |

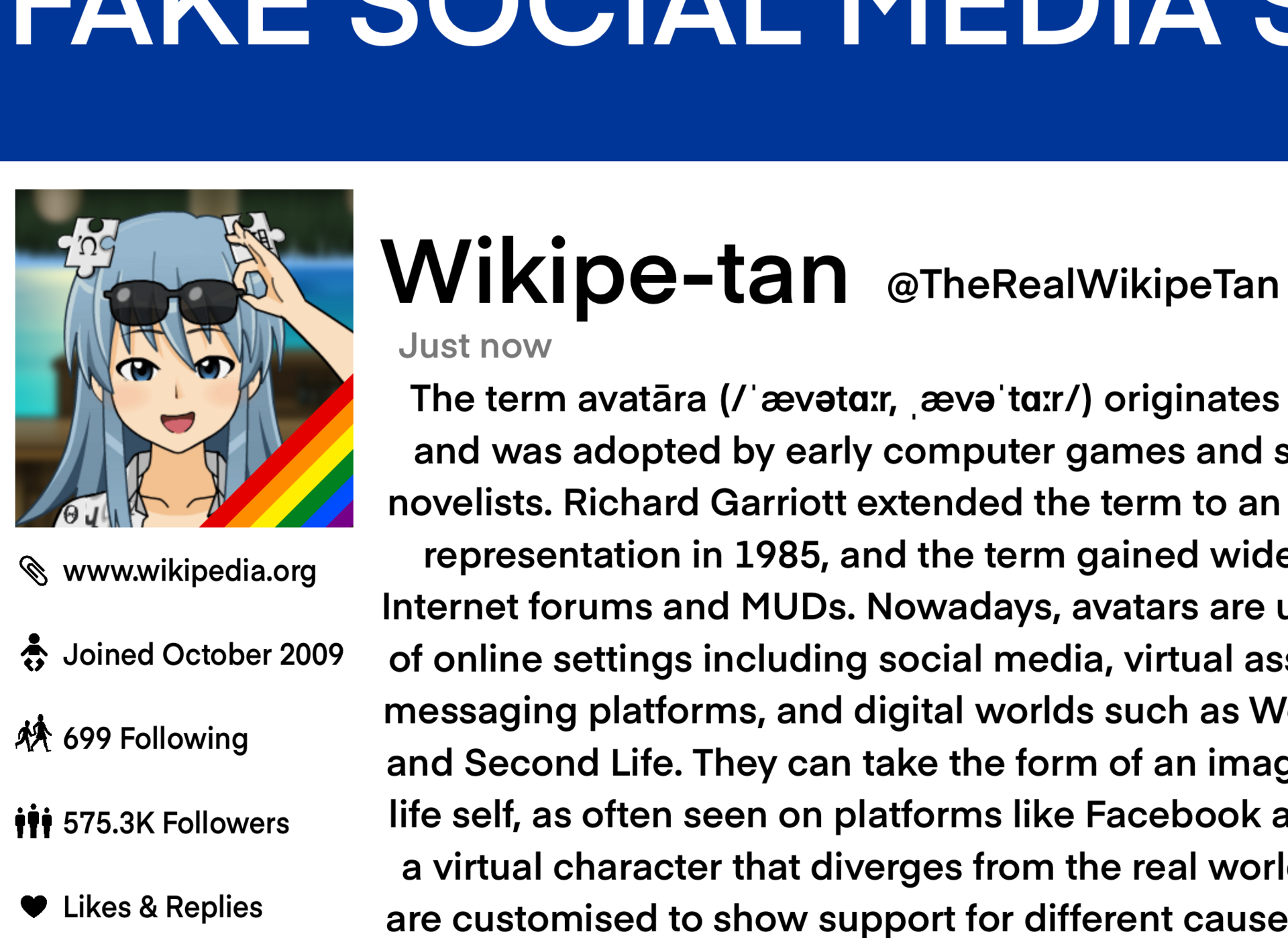

| Customization Early examples of customizable avatars include multi-user systems, including MUDs.[57] Gaia Online has a customizable avatar where users can dress it up as desired.[58] Users may earn credits for completing sponsored surveys or certain tasks to purchase items and upgrades to customize their avatar.[59] Linden Lab's Second Life creates a virtual world in which avatars, homes, decorations, buildings and land are for sale.[60] Less-common items may be designed to appear better than common items, and an experienced player may be identified from a group of new characters before in-game statistics are seen.[57] Avatar Generators To meet the demand for millions of unique, customized avatars, generator tools and services have been created.[61] Many of them, such as the website Picrew, are based around works by original artists.[62] The 2021 Electronic Entertainment Expo featured an avatar creator, to align with its new all-digital nature.[63] Awareness avatars  Example user image with a rainbow flag across one corner Some people add visual details or effects to their avatars to show support for a movement or issue, in a similar way to a physical awareness ribbon. The awareness avatar may have first been used in the New Zealand Internet Blackout, to protest copyright law changes in New Zealand. Globally, protesters replaced their icons with black squares to show solidarity. The protest was successful and proved the method effective at both raising awareness and effecting change. Campaigns have used this method include: Black avatar: February 16–23, 2009 New Zealand Internet Blackout protesting copyright law changes in New Zealand.[64] Yellow tint: Beginning June 17, 2009, to protest the increasing size and role of the United States government.[65] Green tint: Beginning June 18, 2009 support for Iran election protests.[66] French flag tint: Beginning November 13, 2015 to show support for France after the November 2015 Paris attacks.[67] During the COVID-19 pandemic, users added surgical masks and respirators on the faces of characters and avatars.[citation needed] Websites such as Facebook officially supported these efforts by adding the option for several frames supporting the COVID-19 vaccine.[68] Conversely, anti-vaccine advocates have used profile frames to state their opposition to it.[69] Rainbow patterns to represent membership or solidarity with the LGBT community.[70] |

カスタマイズ カスタマイズ可能なアバターの初期の例には、MUDを含むマルチユーザーシステムが含まれる[57]。ガイアオンラインにはカスタマイズ可能なアバターが あり、ユーザーは好きなように着飾ることができる[58]。 [59] リンデンラボのセカンドライフは、アバター、家、装飾品、建物、土地が販売されている仮想世界を作り出している[60]。一般的でないアイテムは一般的な アイテムよりも良く見えるようにデザインされている場合があり、経験豊富なプレイヤーはゲーム内の統計が見られる前に新しいキャラクターのグループから識 別される場合がある[57]。 アバタージェネレーター 何百万というユニークでカスタマイズされたアバターの需要を満たすために、ジェネレーター・ツールやサービスが作られてきた[61]。 ウェブサイトのPicrewのようなそれらの多くは、オリジナル・アーティストによる作品に基づいている[62]。2021年のElectronic Entertainment Expoでは、その新しいオールデジタルな性質に合わせるために、アバター・クリエイターが紹介された[63]。 アウェアネス・アバター  片隅にレインボーフラッグがあるユーザー画像の例 物理的なアウェアネス・リボンと同じように、アバターに視覚的なディテールやエフェクトを追加して、運動や問題への支持を示す人もいる。 アウェアネス・アバターが最初に使われたのは、ニュージーランドの著作権法改正に抗議するための「ニュージーランド・インターネット・ブラックアウト」 だったかもしれない。世界的に、抗議者たちは自分のアイコンを黒い四角に置き換えて連帯を示した。この抗議活動は成功し、この方法が意識の向上と変革の両 方に効果的であることを証明した。この方法を使ったキャンペーンには次のようなものがある: 黒いアバター:2009年2月16日から23日まで、ニュージーランドの著作権法改正に抗議するニュージーランドのインターネットブラックアウト[64]。 黄色の色合い: 2009年6月17日から、米国政府の規模と役割の増大に抗議する[65]。 緑の色合い: 2009年6月18日から、イラン選挙への抗議活動を支援する[66]。 フランス国旗の色合い: 2015年11月13日から、2015年11月のパリ同時多発テロ後のフランスへの支持を示す[67]。 COVID-19のパンデミックの間、ユーザーはキャラクターやアバターの顔にサージカルマスクや人工呼吸器を追加した[要出典]。フェイスブックなどの ウェブサイトは、COVID-19ワクチンを支持するいくつかのフレームのオプションを追加することで、これらの取り組みを公式に支持した[68]。逆 に、反ワクチン擁護者は、それへの反対を表明するためにプロフィールフレームを使用した[69]。 LGBTコミュニティへの加入や連帯を表すレインボーパターン[70]。 |

| Academic study Avatars have become an area of study in the world of academics. According to psychiatrist David Brunski, the emergence of online avatars have implications for domains of scholarly research such as technoself studies, which is concerned with all aspects of identity in a technological society.[j 2] Across the literature, scholars have focused on three overlapping aspects that influence users' perceptions of the social potential of avatars: agency, anthropomorphism, and realism.[j 3] According to researchers K. L. Novak and J. Fox, researchers must differentiate perceived agency (whether an entity is perceived to be human), anthropomorphism (having human form or behavior), identomorphism [71](how much the form of the avatar resembles the player), and realism (the perceived viability of something realistically existing). Perceived agency influences people's responses in the interaction regardless of who or what is actually controlling the representation. An earlier meta-analysis of studies comparing agents and avatars found that both agency and perceived agency mattered: representations controlled by humans were more persuasive than those controlled by bots, and representations believed to be controlled by humans were more persuasive than those believed to be controlled by bots.[j 4] Additionally, researchers have investigated how anthropomorphic representations influence communicative outcomes and found that more human-like representations are judged more favorably; people consider them more attractive, credible, and competent.[j 5] Higher levels of anthropomorphism also lead to higher involvement, social presence, and communication satisfaction.[j 6] Moreover, people communicate more naturally with more anthropomorphic avatars.[j 7] Anthropomorphism is also tied to social influence, as more human-like representations can be more persuasive.[j 8] For the Harvard Business Review, Paul Hemp analysed the effects of avatars on real-world business. He focuses on the game "Second Life", demonstrating that the creators of virtual avatars are willing to spend real money to purchase goods marketed solely to their virtual selves.[72] In addition, research in data collection via Second Life avatars suggested important considerations related to research participant engagement, burden, and retention, as well as accuracy of the data collected.[73] Representation of identity The Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication published a study of the reactions to certain types of avatars by a sample group of human users. The results showed that users commonly chose avatars which were humanoid and matched their gender. The conclusion was that in order to make users feel more "at home" in their avatars, designers should maximise the customizability of visual criteria common to humans, such as skin and hair color, age, gender, hair styles and height.[j 9] Researchers at York University studied whether avatars reflected a user's real-life personality.[74] Student test groups were able to infer upon extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism, but could not infer upon openness and conscientiousness.[74] Researchers have also studied avatars that differ from real-life identity. Sherry Turkle described a middle-aged man who played an aggressive, confrontational female character in his online communities, displaying personality traits he was embarrassed to display in the offline world.[75] Research by Nick Yee of the Daedelus Project demonstrates that an avatar may differ considerably from a player's offline identity, based on gender.[76] However, most players will make an avatar that is (proportionately) equal to their height (or slightly taller).[76] Turkle has observed that some players seek an emotional connection they cannot establish in the real world. She described a case in which a man with a serious heart condition preventing him from ordinary socializing found acceptance and friendship through his online identity.[75] Others have pointed out similar findings in those with mental disorders making social interaction difficult, such as those with autism or similar disabilities.[77] |

学術的研究 アバターは学問の世界でも研究分野となっている。精神科医のデイヴィッド・ブルンスキーによれば、オンライン・アバターの出現は、テクノロジー社会におけ るアイデンティティのあらゆる側面に関わるテクノセルフ研究などの学術研究の領域に影響を与えるものである。 [研究者のK. L. NovakとJ. Foxによれば、研究者は知覚された主体性(実体が人間であると知覚されるかどうか)、擬人化(人間の形や振る舞いを持つこと)、同一性 (identomorphism [71])(アバターの形がプレイヤーにどれだけ似ているか)、リアリズム(何かが現実的に存在すると知覚される可能性)を区別しなければならない。知覚 されたエージェンシーは、誰が、あるいは何が実際に表現をコントロールしているかに関係なく、インタラクションにおける人々の反応に影響を与える。エー ジェントとアバターを比較した先行研究のメタアナリシスによると、エージェンシーと知覚されたエージェンシーの両方が重要であることがわかった。つまり、 人間によってコントロールされた表現は、ボットによってコントロールされたものよりも説得力があり、人間によってコントロールされていると信じられている 表現は、ボットによってコントロールされていると信じられているものよりも説得力があった[j 4]。 さらに、研究者は擬人化された表現がコミュニケーションの結果にどのような影響を与えるかを調査し、より人間に近い表現がより好意的に判断され、人々はより魅力的で、信頼でき、有能であると考えることを発見した[j 5]。 ハーバード・ビジネス・レビュー』誌のために、ポール・ヘンプは現実世界のビジネスにおけるアバターの効果を分析した。彼は「Second Life」というゲームに焦点を当て、仮想アバターの作成者が、仮想の自分だけに販売されている商品を購入するために現実のお金を使うことを厭わないこと を示している[72]。さらに、Second Lifeのアバターを介したデータ収集の研究では、収集されたデータの正確さだけでなく、研究参加者の関与、負担、定着に関する重要な考慮事項が示唆され ている[73]。 アイデンティティの表現 Journal of Computer-Mediated Communicationは、人間のユーザーのサンプルグループによる、ある種のアバターに対する反応についての研究を発表した。その結果、ユーザーは 一般的に人型で自分の性別に合ったアバターを選ぶことがわかった。ヨーク大学の研究者は、アバターがユーザーの現実の人格を反映しているかどうかを研究し た[74]。学生のテストグループは、外向性、快感性、神経質性を推測することができたが、開放性と良心性を推測することはできなかった[74]。 研究者たちは現実のアイデンティティとは異なるアバターについても研究している。シェリー・タークル(Sherry Turkle)氏は、オンラインコミュ ニティで攻撃的で対立的な女性キャラクターを演じ、オフラインの 世界では恥ずかしくて見せられないような性格的特徴を見せる中年男性に ついて述べている[75]。彼女は、通常の社交を妨げる深刻な心臓疾患を持つ男性が、オンライン上のアイデンティティを通じて受容と友情を見出した事例を 紹介している[75]。他の人々は、自閉症や同様の障害を持つ人々など、社会的相互作用を困難にする精神障害を持つ人々においても同様の発見があることを 指摘している[77]。 |

| Artificial intelligence and elections – Use and impact of AI on political elections Michaelmas (novel) – 1977 novel by Algis Budrys NECA Project – Net Environment for Embodied Emotional Conversational Agents Online identity – Social identity that an Internet user establishes in online communities and website Persona (user experience) – Personalized fictional characters representing a consumer or user category Player character – Character controlled by a game player Pointman (user interface) – User interface used in a 3D environment Proteus effect – Behavioral effect in virtual worlds Ready Player One – 2011 science fiction novel by Ernest Cline Ready Player One (film) – 2018 film by Steven Spielberg Thumbnail – Reduced-size versions of images or videos Viverse – Virtual reality platform VTuber – Streamers that use virtual avatars |

人工知能と選挙 - 政治選挙におけるAIの利用と影響 マイケルマス(小説) - アルギス・ブドリスによる1977年の小説 NECAプロジェクト - 実体化された感情会話エージェントのためのネット環境 オンライン・アイデンティティ - インターネット・ユーザーがオンライン・コミュニティやウェブサイトで確立する社会的アイデンティティ ペルソナ(ユーザー・エクスペリエンス) - 消費者やユーザー・カテゴリーを代表するパーソナライズされた架空のキャラクター。 プレイヤーキャラクター - ゲームプレイヤーが操作するキャラクター ポイントマン(ユーザーインターフェース) - 3D環境で使用されるユーザーインターフェース プロテウス効果 - 仮想世界における行動効果 レディ・プレイヤー・ワン - アーネスト・クラインによる2011年のSF小説 レディ・プレイヤー・ワン(映画) - 2018年スティーブン・スピルバーグ監督作品 Thumbnail - 画像や動画の縮小版。 Viverse - バーチャルリアリティプラットフォーム VTuber - バーチャルアバターを使うストリーマー。 |

| Academic sources Nowak, Kristine L. (2004). "The Influence of Anthropomorphism and Agency on Social Judgment in Virtual Environments". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 9 (2): n.p. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00284.x. Brunskill, David (December 2013). "Social media, social avatars and the psyche: is Facebook good for us?". Australasian Psychiatry. 21 (6): 527–532. doi:10.1177/1039856213509289. PMID 24159052. S2CID 7526092. Nowak, K. L.; Fox, J. (2018). "Avatars and Computer-Mediated Communication: A Review of the Definitions, Uses, and Effects of Digital Representations". Review of Communication Research. 6: 30–53. doi:10.12840/issn.2255-4165.2018.06.01.015 (inactive November 2, 2024). Fox, J.; Ahn, S. J.; Janssen, J. H.; Yeykelis, L.; Segovia, K. Y.; Bailenson, J. N. (2015). "Avatars versus agents: A metaanalysis quantifying the effects of agency on social influence". Human-Computer Interaction. 30 (5): 401–432. doi:10.1080/07370024.2014.921494. S2CID 21235038. Westerman, D.; Tamborini, R.; Bowman, N. D. (2015). "The effects of static avatars on impression formation across different contexts on social networking sites". Computers in Human Behavior. 53: 111–117. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.026. S2CID 43018984. Kang, S. H.; Watt, J. H. (2013). "The Impact of Avatar Realism and Anonymity on Effective Communication via Mobile Devices". Computers in Human Behavior. 29 (3): 1169–1181. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.010. Heyselaar, E.; Hagoort, P.; Segaert, K. (2017). "In dialogue with an avatar, language behavior is identical to dialogue with a human partner". Behavior Research Methods. 49 (1): 46–60. doi:10.3758/s13428-015-0688-7. PMC 5352801. PMID 26676949. Gong, L (2008). "How social is social responses to computers? The function of the degree of anthropomorphism in computer representations". Computers in Human Behavior. 24 (4): 1494–1509. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2007.05.007. Nowak, K. L.; Rauh, C. (2005). "The Influence of the Avatar on Online Perceptions of Anthropomorphism, Androgyny, Credibility, Homophily, and Attraction". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 11 (1): 153–178. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.tb00308.x. Further reading Cooper, Robbie 2007. Alter Ego: Avatars and Their Creators. London: Chris Boot. ISBN 978-1-905712-02-1. Holzwarth, Martin; Janiszewski, Chris; Neumann, Marcus (2006). "The Influence of Avatars on Online Consumer Shopping Behavior". Journal of Marketing. 70 (4): 19–36. doi:10.1509/jmkg.70.4.19. Nowak, K. L.; Fox, J. (2018). "Avatars and Computer-Mediated Communication: A Review of the Definitions, Uses, and Effects of Digital Representations". Review of Communication Research. 6: 30–53. doi:10.12840/issn.2255-4165.2018.06.01.015 (inactive November 2, 2024). Sloan, R. J. S., Robinson, B., Cook, M., and Bown, J. (2008). "Dynamic Emotional Expression Choreography: Perception of Naturalistic Facial Expressions". In M. Capey, B. Ip and F. Blastland, editors, SAND Conference Proceedings, Swansea, UK 24–28 November 2008. Swansea Metropolitan University: Swansea. Wood, Natalie T.; Solomon, Michael R.; Englis, Basil G. (2005). "Personalization of Online Avatars: Is the Messenger as Important as the Message?". International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising. 2 (1/2): 143–161. doi:10.1504/ijima.2005.007509. |

学術資料 Nowak, Kristine L. (2004). 「仮想環境における社会的判断における擬人化とエージェンシーの影響」. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 9 (2): n.p. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00284.x. Brunskill, David (December 2013). 「ソーシャルメディア、社会的アバターと精神:Facebookは私たちのために良いですか?」. Australasian Psychiatry. 21 (6): 527–532. doi:10.1177/1039856213509289. PMID 24159052. S2CID 7526092. Nowak, K. L.; Fox, J. (2018). 「Avatars and Computer-Mediated Communication: A Review of the Definitions, Uses, and Effects of Digital Representations」. Review of Communication Research. 6: 30-53. doi:10.12840/issn.2255-4165.2018.06.01.015 (inactive November 2, 2024). Fox, J.; Ahn, S. J.; Janssen, J. H.; Yeykelis, L.; Segovia, K. Y.; Bailenson, J. N. (2015). 「アバター対エージェント: A metaanalysis quantifying the effects of agency on social influence」. Human-Computer Interaction. 30 (5): 401–432. doi:10.1080/07370024.2014.921494. s2cid 21235038. Westerman, D.; Tamborini, R.; Bowman, N. D. (2015). 「The effects of static avatars on impression formation across different contexts on social networking sites」. Computers in Human Behavior. 53: 111-117. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.026. s2cid 43018984. Kang, S. H.; Watt, J. H. (2013). 「The Impact of Avatar Realism and Anonymity on Effective Communication via Mobile Devices」. Computers in Human Behavior. 29 (3): 1169–1181. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.010. Heyselaar, E.; Hagoort, P.; Segaert, K. (2017). 「アバターとの対話において、言語行動は人間相手との対話と同一である」. Behavior Research Methods. 49 (1): 46–60. doi:10.3758/s13428-015-0688-7. PMC 5352801. PMID 26676949. Gong, L (2008). 「コンピュータに対する社会的反応はどの程度社会的なのか?コンピュータ表現における擬人化の程度の機能」. Computers in Human Behavior. 24 (4): 1494–1509. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2007.05.007. Nowak, K. L.; Rauh, C. (2005). 「アバターが擬人化、アンドロジニー、信頼性、同類性、および魅力のオンライン知覚に与える影響」。Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 11 (1): 153–178. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.tb00308.x. さらに読む Cooper, Robbie 2007. Alter Ego: Avatars and Their Creators. ロンドン: クリス・ブーツ. ISBN 978-1-905712-02-1. Holzwarth, Martin; Janiszewski, Chris; Neumann, Marcus (2006). 「The Influence of Avatars on Online Consumer Shopping Behavior」. Journal of Marketing. 70 (4): 19–36. doi:10.1509/jmkg.70.4.19. Nowak, K. L.; Fox, J. (2018). 「アバターとコンピュータ媒介コミュニケーション: A Review of the Definitions, Uses, and Effects of Digital Representations」. Review of Communication Research. 6: 30-53. doi:10.12840/issn.2255-4165.2018.06.01.015 (inactive November 2, 2024). Sloan, R. J. S., Robinson, B., Cook, M., and Bown, J. (2008). 「ダイナミックな感情表現の振り付け: 自然な表情の知覚」。M. Capey, B. Ip and F. Blastland, editors, SAND Conference Proceedings, Swansea, UK 24-28 November 2008. Swansea Metropolitan University: Swansea. Wood, Natalie T.; Solomon, Michael R.; Englis, Basil G. (2005). 「オンラインアバターの人格化: メッセンジャーはメッセージと同じくらい重要か?International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising. 2 (1/2): 143–161. doi:10.1504/ijima.2005.007509. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avatar_(computing) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆