Alexandre

Kojeve,

1902-1968

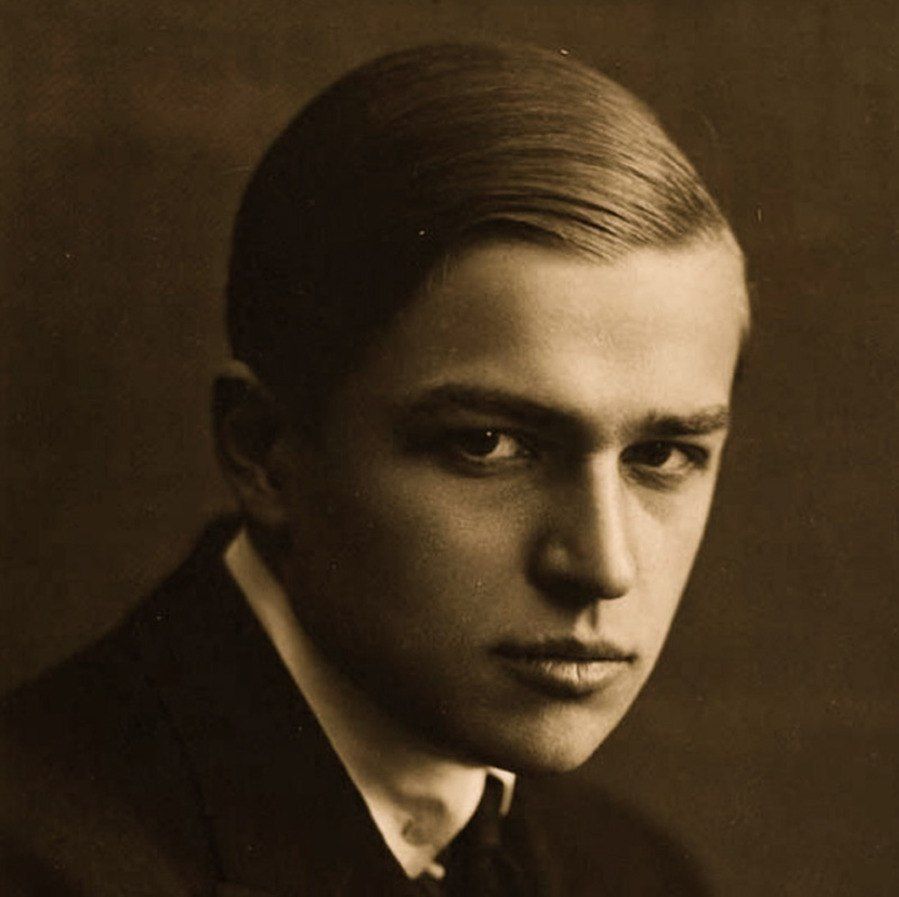

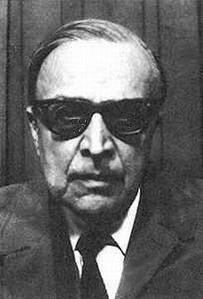

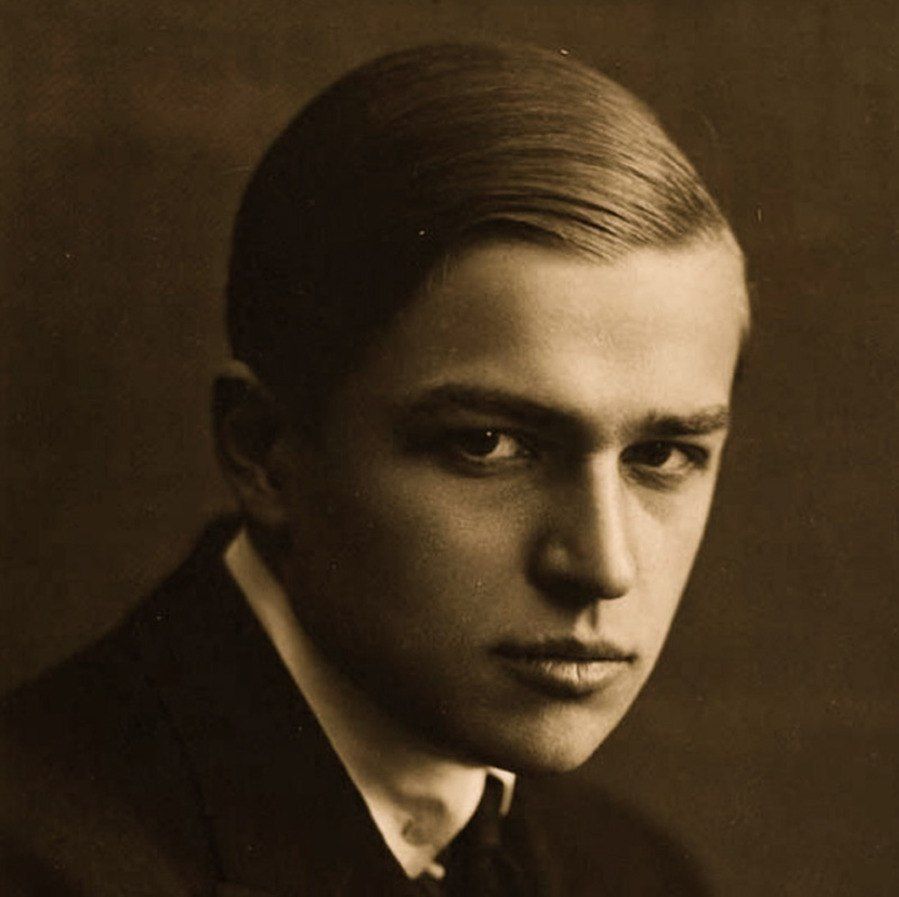

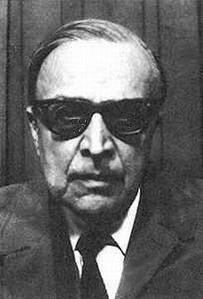

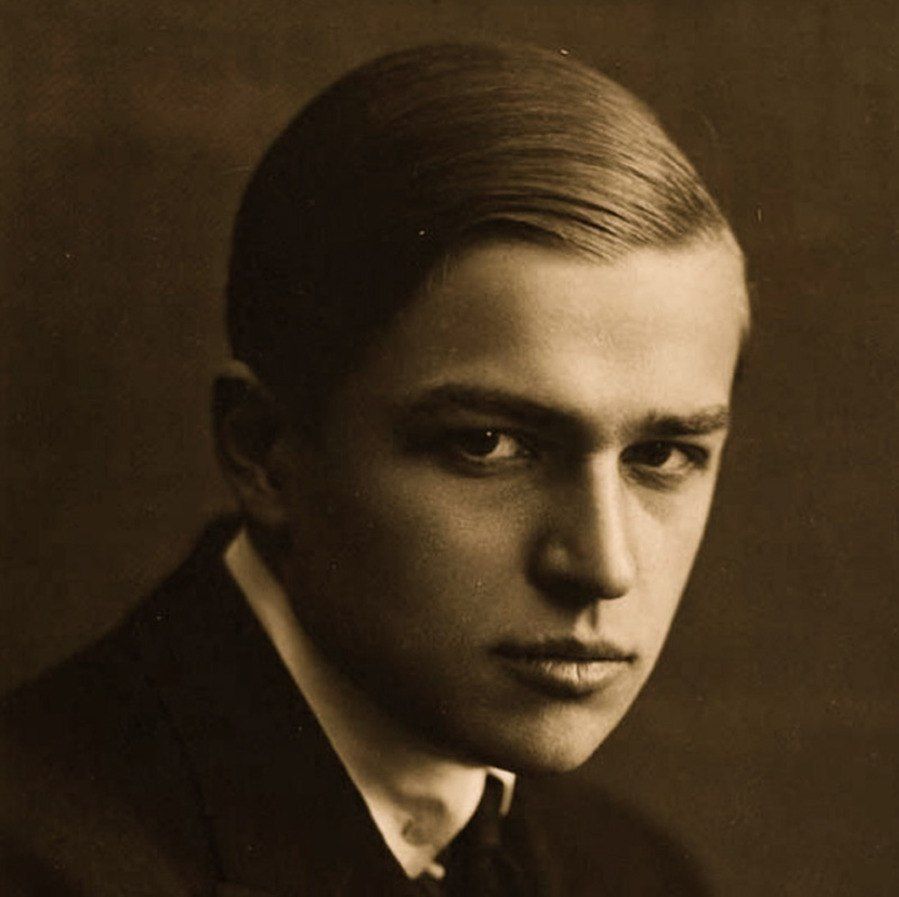

Kojève in Berlin, 1922 / Kojève, n.d.

Alexandre

Kojeve,

1902-1968

Kojève in Berlin, 1922 / Kojève, n.d.

アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ[a] (Aleksandr Vladimirovich Kozhevnikov、[b] 1902年4月28日 - 1968年6月4日)はロシア生まれのフランスの哲学者、国際公務員であり、その哲学セミナーは20世紀のフランス哲学、特に20世紀の大陸哲学へのヘー ゲル概念の統合を通じて一定の影響を与えた[2][3](→「アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ『ヘーゲル読解入門』を読む」)。

| Alexandre Kojève (1902-1968) - An Encyclopedia of Russian Thought Born Aleksandr Kozhevnikov to a wealthy family of industrialists in Moscow, Alexandre Kojève garnered acclaim as a philosopher only after his emigration to Western Europe in 1920. His lectures on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, held at the École pratique des hautes études in Paris from 1933-1939, are thought to have greatly renewed interest in Hegel in the West and inaugurated the “generation of three H’s”: a constellation of postwar French philosophers whose work sought to synthesize Hegel, Heidegger, and Husserl. After the Second World War, Kojève served in the French Ministry of Economy and Finance, where his theory of the post-historical state, allegedly inspired by Stalinism, is often considered to have played some conceptual role in the formation of the European Union. In the aftermath of the Cold War, Kojève’s interpretation of the “End of History” in Hegel’s Phenomenology has since seen renewed interest from the perspective of post-Soviet philosophy, in light of a growing critique of teleological thinking in the philosophy of history. |

アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ(1902-1968) アレクサンドル・コジェーヴは、モスクワの裕福な実業家一家にアレクサンドル・コジェフニコフとして生まれた。1920年に西ヨーロッパへ亡命した後、哲 学者として評価を得た。1933年から1939年にかけてパリの実践高等研究院で行ったヘーゲルの『精神現象学』に関する講義は、西洋におけるヘーゲル研 究の大きな再興をもたらし、戦後フランス哲学者の群像である「三つのHの世代」の幕開けとなった。この世代はヘーゲル、ハイデガー、フッサールを統合しよ うとする試みで知られている。第二次世界大戦後、コジェーヴはフランス経済財務省に勤務した。そこで提唱した「ポスト歴史的国家」理論は、スターリン主義 に影響を受けたとされ、欧州連合の形成において概念的な役割を果たしたとよく言われる。冷戦終結後、ヘーゲルの『精神現象学』における「歴史の終焉」に関 するコジェーヴの解釈は、歴史哲学における目的論的思考への批判が高まる中で、ポストソビエト哲学の観点から再び注目を集めている。 |

| The “Russian” Period: Emigration, Vladimir Solovyov, and Atheism Kojève emigrated shortly after the October Revolution at the age of eighteen, yet his political allegiances remained ambivalent throughout his life—he once paradoxically described his own conversion to communism in a Soviet jail, having been arrested for trading soap on the black market. Instead of emigration for political reasons, the nascent philosopher justified his relocation abroad through his philosophical studies at the University of Heidelberg. At Heidelberg, Kojève studied under Karl Jaspers and Heinrich Rickert and wrote his master’s dissertation on Vladimir Solovyov’s philosophy of history. Although his dissertation on Solovyov did little more than summarize the religious philosopher’s work, it was published as his first article, in French in 1927 and in German in 1930. The article was positively received by the émigré philosophical community, with figures such as Fedor Stepun and Nikolai von Bubnoff writing to congratulate him and Georges Florovsky even inviting him to join the Russian Society in Paris, of which Nikolai Berdiaev and Lev Shestov served as President and Vice-President, respectively. In the dissertation, Kojève outlined three major periods in the development of Solovyov’s thought: an earlier Slavophile period, a Catholic or ecumenical period, and a later historical period embodied in Solovyov’s final work on the figure of the anti-Christ, Three Conversations. In the first two periods, Kojève sees Solovyov articulating a theogonic principle, whereby the kingdom of God is incarnated on earth in the theory of Godmanhood and fallen Sophia. Humanity slowly reveals to itself the Absolute—in the Slavophile period, Solovyov uniquely tasked the Russian people with this revelation, whereas the ecumenical period attributed this revelation to Christendom more broadly. Kojève was most interested, however, in the third later period, in which he argued that Solovyov had abandoned his belief in humanity’s reconciliation with a religious Absolute: Solovyov no longer believed that history leads in a steady progression to the realization of “total life,” of the “kingdom of God on Earth,” or that with this realization history finds its natural conclusion. He now in fact takes the opposite position, that history ends in the construction of an earthly empire which however is only a caricature of a theocracy, because it is run by the principle of evil embodied in the figure of the Antichrist. […] One sees that history is for Solov’ev no longer the gradual surmounting of the evil principle but rather a perpetual strengthening of it. (“Die Geschichtsphilosophie Wladimir Solowjews”) Kojève interpreted this pessimistic, final period of Solovyov’s philosophy as a decisive move toward a definition of the historical, although what the definition was remains unclear, given Solovyov’s death shortly after the publication of Three Conversations. The connection between the historical and a disbelief in religious thought, nevertheless culminated in Kojève’s posthumously published manuscript Atheism. Written in Russian in 1931 but published for the first time in French in 1998, Atheism illustrates a clear trajectory from Kojève’s early interest in Solovyov to his later atheist, anthropological interpretation of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. In the manuscript, Kojève claimed that all atheist thought emerges originally from a religious worldview, rather than vice versa, and sought to articulate his theory of an “atheist religion.” According to Kojève, and in language that later paralleled in his seminars on Hegel, personhood is formed through interrelation: each person understands themselves in relationship to what is not them. Extending this construct further, Kojève claims that humankind begins with a religious worldview, in that it articulates God as “the ultimate Other” to themselves, yet the first step toward atheism is to deny the existence of this other: As for the atheist, for him God is not something. It is nothingness, and between myself and God there cannot be a relation, nor anything in common, since I know to a certain extent that I exist (I am a something), whereas God simply doesn’t exist. (L’Athéisme, 72) The paradox for Kojève lies in that the atheist must necessarily acknowledge God in order to deny God’s non-existence—the very act of negation implies the existence of that which is negated. For Kojève, then, both the atheist and the theist are united in this “path toward God” as an Other, and the “atheist religion” is understood as the conscientious negation of this path. Kojève’s intent was to establish an atheist anthropology, in which human existence is grounded in nothing but its own immanent being. By denying the existence of God (the ultimate Other in that it is completely unqualifiable and foreign) the atheist thereby establishes an equivalency with all other things, in that these things are qualifiable like the atheist themself. Borrowing from Heidegger the notion of Being-in-World, Kojève therefore claims that the atheist worldview creates a homogeneous, immanent community with the material likeness of things which are not God: In seeing outside of myself other people, I cease to perceive the world as something completely foreign to me, as something other, radically different from this something that I myself am. I can fear an “empty” world, that is, it could seem to me “foreign,” but the fear disappears (or becomes something else, dread without object transforms into concrete fear before an enemy, etc.) as soon as I recognize another person: I see immediately that my fear is in vain, that the world is not as strange to me as it seemed before. (92) In Atheism, Kojève therefore followed through on Solovyov’s late transition toward a historical world, embodied in the Anti-Christ, in which (Kojève claims) a transcendental relation with God has become impossible, yet a material, earthly community is established in its wake. |

「ロシア」時代:亡命、ウラジーミル・ソロヴィヨフ、そして無神論 コジェーヴは十月革命直後、十八歳で亡命した。しかし彼の政治的立場は生涯を通じて曖昧なままであった。皮肉なことに、彼はソ連の刑務所で共産主義に改宗 したと語っている。その理由は闇市場で石鹸を取引した罪で逮捕されたためだ。政治的理由による亡命ではなく、この若き哲学者はハイデルベルク大学での哲学 研究を国外移住の正当化理由とした。ハイデルベルクではカール・ヤスパースとハインリヒ・リッカートの指導を受け、ウラジーミル・ソロヴィヨフの歴史哲学 に関する修士論文を執筆した。 ソロヴィヨフに関するこの論文は、宗教哲学者の著作を要約したに過ぎなかったが、1927年にフランス語で、1930年にはドイツ語で彼の最初の論文とし て出版された。この論文は亡命哲学者のコミュニティで好評を博し、フェドール・ステプーンやニコライ・フォン・ブブノフらが祝意を伝える書簡を送り、ジョ ルジュ・フロロフスキーはパリのロシア協会への参加を勧誘した。同協会ではニコライ・ベルジャエフが会長、レフ・シェストフが副会長を務めていた。論文の 中でコジェーヴは、ソロヴィヨフの思想発展における三つの主要な時期を概説した。初期のスラヴ主義期、カトリック的あるいはエキュメニカルな期、そして反 キリストの人物像に関するソロヴィヨフの最終著作『三つの対話』に体現された後期歴史的期である。最初の二つの時期において、コジェーヴはソロヴィヨフが 神生成原理を明示していると見る。すなわち神人論と堕落したソフィアの理論によって、神の王国が地上に具現化されるという原理である。人類は徐々に自らに 絶対者を啓示する――スラヴ主義期にはソロヴィヨフはロシア民族にこの啓示の使命を独自に課したが、エキュメニカル期にはより広範なキリスト教世界全体に この啓示を帰した。しかしコジェーヴが最も関心を寄せたのは、第三の後期段階である。彼はこの時期のソロヴィヨフが、人類と宗教的絶対者との和解を信じる 立場を放棄したと論じた: ソロヴィヨフはもはや、歴史が「総体的な生命」や「地上の神の国」の実現へと着実に進展するとも、この実現をもって歴史が自然な終結を迎えるとも信じてい なかった。むしろ彼は逆の立場を取る。すなわち歴史は地上帝国の建設をもって終焉するが、それは反キリストという悪の原理に支配されるため、神政政治の滑 稽な模倣に過ぎない。[…] ソロヴィエフにとって歴史はもはや悪の原理の漸進的克服ではなく、むしろその永続的強化であることがわかる。(「ウラジーミル・ソロヴィエフの歴史哲 学」) コジェーヴは、ソロヴィエフ哲学のこの悲観的な最終段階を、歴史的実体の定義に向けた決定的な動きと解釈した。ただし、その定義が何を指すかは不明のままである。というのも、『三つの対話』刊行直後にソロヴィエフが死去したためだ。 しかし「歴史的」概念と宗教思想への不信との結びつきは、コジェーヴの遺稿『無神論』において頂点を迎えた。1931年にロシア語で執筆されながら 1998年に初めてフランス語で出版された『無神論』は、コジェーヴの初期におけるソロヴィエフへの関心から、後年のヘーゲルの『精神現象学』に対する無 神論的人類学的解釈に至る明確な軌跡を示している。この原稿でコジェーヴは、あらゆる無神論的思想は本来、宗教的世界観から派生するものであり、その逆で はないと主張し、「無神論的宗教」という自身の理論を明確にしようとした。 コジェフによれば、後にヘーゲルに関するセミナーで展開されるのと同じ言葉遣いで、人格は相互関係を通じて形成される。各人は、自分ではないものとの関係 性において自己を理解するのだ。この概念をさらに推し進め、コジェフは人類は宗教的世界観から出発すると主張する。つまり、神を自己に対する「究極の他 者」として規定するのだ。しかし無神論への第一歩は、この他者の存在を否定することにある: 無神論者にとって神は何かではない。それは無であり、私と神の間には関係も共通点も存在し得ない。なぜなら私はある程度自分が存在することを知っている(私は何かである)が、神は単に存在しないからだ。(『無神論』72頁) コジェーヴにとってのパラドックスは、無神論者が神の非存在を否定するためには必然的に神を認めざるを得ない点にある。否定という行為そのものが、否定さ れるものの存在を暗示するのだ。したがってコジェーヴによれば、無神論者と有神論者はともに、他者としての「神への道」において結ばれており、「無神論的 宗教」とはこの道を自覚的に否定するものと理解される。 コジェフの意図は、人間の存在が自らの内在的存在以外に何ものにも根ざさないという無神論的人類学を確立することにあった。神(完全に規定不能で異質な究 極の他者)の存在を否定することで、無神論者は他のあらゆるものと等価性を確立する。なぜならそれらのものは無神論者自身と同様に規定可能だからだ。ハイ デガーの「世界内存在」概念を借用し、コジェーヴはこう主張する。無神論的世界観は、神ではない物質的類似性を持つものとの均質的で内在的な共同体を創出 するのだと: 他者を自己の外に認識するとき、私は世界を完全に異質な存在、すなわち自己とは根源的に異なる他者として捉えることをやめる。「空虚な」世界を恐れること はある。つまり世界が「異質」に映ることもある。しかし他者を認識した瞬間、その恐怖は消える(あるいは別のものへ変わる。対象なき恐怖は敵を前にした具 体的な恐怖へ変容するなど)。直ちに自分の恐怖が無駄だと気づくのだ。世界は以前思っていたほど自分にとって異質ではないと。(92) したがってコジェーヴは『無神論』において、ソロヴィヨフの晩年の転換——反キリストに体現される歴史的世界への移行——を継承した。そこでは(コジェーヴによれば)神との超越的関係は不可能となったが、その代わりに物質的・地上的共同体が確立されるのである。 |

| The Hegel Seminars: 1933 to 1939 Undoubtedly his greatest legacy in French philosophy, Kojève’s seminars on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit mark in many ways a continuation of his interest in an “atheist anthropology” from his early years. Kojève inherited the seminars from his friend and in-law Alexandre Koyré, another Russo-French philosopher who played an influential role in the dissemination of phenomenology in France. Koyré studied with Husserl in Germany and served as the editor of Recherches philosophiques, a philosophy journal responsible for publishing Heidegger, Levinas, Sartre, and others. In 1933, Koyré accepted work through the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs at the University of Cairo and bequeathed his teaching position to Kojève, who was familiar with the material after having previously attended the seminars. When Koyré led the seminars, the topic was “The History of Religious Ideas in Europe,” and in its section on Hegel, Koyré traced Hegel’s mature later period out of an early period of religious idealism and German Romanticism. In parallel with his thesis on Solovyov, Atheism, and Koyré’s interest in Hegel’s philosophical development, Kojève in his own seminars interpreted Hegel’s philosophy of Absolute Spirit as a secularization of Christian anthropology, claiming that “according to Hegel, one cannot realize the Christian anthropological ideal […] except in ‘eliminating’ Christian theology” (Introduction à la lecture de Hegel, 224). Kojève’s interpretation of the Phenomenology of Spirit relied overwhelming on its fourth chapter, in which Hegel described the formation of self-consciousness and the dialectic of Lord and Bondsman. If in Hegel, the Lord and Bondsman dialectic signals a struggle for recognition, in which the Lord momentarily “succeeds” in forcing the Bondsman to recognize his independence by risking death, Kojève instead chose to interpret this dialectical relationship as the struggle for desire. Kojève notably canonized the translation of Hegel’s dialectic to Master and Slave and transformed recognition of the Master by the Slave into the human subject’s desire to be desired by another being. When, for example, a knight risks his life in accordance with chivalric code, he has risked death in order to be desired by others: a princess, other knights, and society writ large. The supremacy of the Master, however, is but a fleeting moment in the dialectic, as the Slave ultimately holds over the Master the power of recognition. In resonance with Marx, Kojève moreover attributes to the Slave the motor of history through his labor: by being forced to recognize the Master, the Slave works and therefore propels forward historical development by negating the givens of the world through action. Kojève follows Hegel in tracing the dialectical development of these contradictory relationships across history, claiming their various manifestations to be indicative of the development of Absolute Spirit. Unique however to Kojève’s interpretation is the anthropomorphizing of Spirit: the various stages of negation and sublation in Hegel’s dialectical progression of Spirit ultimately turn out to be for Kojève the human being itself. This progression concludes with the image of modern, atheist and scientific man, who is satisfied, has overcome an opposition of Master and Slave by embodying both, and therefore no longer struggles: “History ends when Man no longer acts in strict sense of the word, that is, when he no longer negates or transforms the natural and social given through bloody Struggle and creative Work” (Introduction, 547). The vague nature of Kojève’s interpretation of Hegel encouraged diverse definitions of the end of History. Nevertheless, Kojève outlined that at the end of History, the modern human would be the embodiment of Absolute Spirit in the form of anthropomorphized wisdom: if the historical process was symbolized by the philosopher (in the desire for wisdom), the modern human is the sage who has come to embody this wisdom. Solovyov’s Anti-Christ, and the “homogeneous community” in Atheism, all presaged this teleological figure, yet this view of the end of History held the widest resonance in political theory. |

ヘーゲル・セミナー:1933年から1939年 フランス哲学における彼の最大の遺産であることは疑いない。コジェーヴのヘーゲル『精神現象学』に関するセミナーは、多くの点で彼の初期からの「無神論的 人類学」への関心の継続を示している。コジェーヴはこのセミナーを友人であり義理の兄弟でもあるアレクサンドル・コイレから引き継いだ。コイレもまたロシ ア系フランス人哲学者であり、フランスにおける現象学の普及に重要な役割を果たした人物である。コイレはドイツでフッサールに師事し、ハイデガー、レヴィ ナス、サルトルらを掲載した哲学雑誌『哲学研究』の編集者を務めた。1933年、コイレはフランス外務省の派遣でカイロ大学に赴任することになり、自身の 教職をコジェーヴに譲った。コジェーヴは以前セミナーに参加していたため、教材に精通していた。 コイレがセミナーを主導した際のテーマは「ヨーロッパにおける宗教思想の歴史」であり、ヘーゲルに関するセクションでは、宗教的観念論とドイツ・ロマン主 義の初期段階から、ヘーゲルの成熟した後期思想を辿った。コジェーヴはソロヴィヨフに関する自身の論文や無神論論考、そしてヘーゲル哲学の発展への関心に 並行して、自身のセミナーにおいてヘーゲルの絶対精神哲学をキリスト教的人類学の世俗化として解釈した。彼は「ヘーゲルによれば、キリスト教的人類学的理 想は[…]キリスト教神学を『排除』することによってのみ実現し得る」と主張した (『ヘーゲル読解入門』224頁)。 コジェーヴの『精神現象学』解釈は、第四章に圧倒的に依拠していた。そこではヘーゲルが自己意識の形成と主従弁証法を論じている。ヘーゲルにおいて主人と 奴隷の弁証法が承認をめぐる闘争を示す場合、主人は死を賭して奴隷に自らの独立性を認めさせることで一時的に「成功」する。しかしコジェーヴはこの弁証法 的関係を欲望をめぐる闘争として解釈することを選んだ。コジェーヴは特に、ヘーゲルの弁証法を主人と奴隷に置き換える解釈を正統化し、奴隷による主人の承 認を、人間的主体が他者から渇望されることを求める欲望へと変容させた。例えば騎士が騎士道に従って命を危険に晒す時、それは他者――姫君、他の騎士、そ して社会全体――から渇望されるために死を賭したのである。しかし主人の優位性は弁証法における一瞬の現象に過ぎない。奴隷は最終的に主人に対して承認の 力を握るからだ。マルクスと共鳴するように、コジェーヴはさらに労働を通じて歴史の推進力を奴隷に帰する。主人を承認せざるを得ない状況下で、奴隷は働 き、行動によって世界の既成事実を否定することで歴史的発展を推進するのである。 コジェーヴはヘーゲルに従い、これらの矛盾した関係が歴史を通じて弁証法的に発展する軌跡を辿り、その多様な現れが絶対精神の発展を示すと主張する。しか しコジェーヴ解釈の独自性は、精神を擬人化することにある。ヘーゲルの精神の弁証法的進展における否定と揚棄の諸段階は、コジェーヴにとって究極的には人 間そのものとなるのだ。この進展は、現代的で無神論的かつ科学的な人間のイメージをもって完結する。この人間は満足し、主人と奴隷の対立を両者を体現する ことで克服したため、もはや闘争しない。「歴史は、人間が厳密な意味での行動、すなわち血なまぐさい闘争と創造的労働を通じて自然的・社会的既成事実を否 定したり変革したりしなくなった時に終わる」(序文、547頁)。 コジェーヴのヘーゲル解釈の曖昧さは、歴史の終焉に関する多様な定義を生んだ。それでもコジェーヴは、歴史の終焉において現代人は擬人化された知恵という 形で絶対精神を体現すると示した。歴史的過程が哲学者(知恵への渇望)によって象徴されるなら、現代人はこの知恵を体現するに至った賢者である。ソロヴィ ヨフの反キリストや『無神論』における「均質な共同体」は、いずれもこの目的論的な存在を予見していた。しかし歴史の終焉に関するこの見解は、政治理論に おいて最も広範な反響を呼んだのである。 |

| Debates on the Political and the Universal State After World War II, Kojève took up an advisory role in the French Ministry of Economy and Finance, thanks in large part to the recommendations of French politicians who had attended his seminars on Hegel. His role in pursuing the reduction of tariffs within the European Economic Community has spurred rumors that his political philosophy inspired the foundation of the European Union. Regardless of the veracity of these claims, in the post-war period Kojève found himself on opposing sides of debates within political theory. At the heart of the debate lay the very nature of what defines the political. In his The Concept of the Political (1927), Carl Schmitt had defined the political as the distinction between friend and enemy, with the political state’s coalescence dependent upon an opposition to an external enemy. In the most important work of Kojève’s later period, An Outline for a Phenomenology of Right (1943), Kojève relied on this definition of the political by Schmitt, claiming: For there to be a State the following two conditions must be met: 1) there must be a Society in which all members are “friends,” and which treats as an enemy every non-member whoever it may be; 2) in the interior of this Society a group of “governors” must clearly distinguish themselves from the other members who constitute the “governed.” (Esquisse d’une phénoménologie du droit, 143). This opposition of friend and enemy within the political sphere paralleled the struggle for recognition within Kojève’s Master/Slave dialectic. In 1955, however, Kojève began a correspondence with Schmitt concerning the possibility of a political order without conflict. In their exchange, Schmitt asked Kojève whether in Hegelian philosophy an eternal enemy is possible, given the passing nature of the Master/Slave dialectic as a placeholder for societal conflict. Kojève responded by claiming that history is the “history of enmity between peoples” and that this enmity ends when history has concluded (“Correspondence,” 107). In this line of argumentation, therefore, the political could not exist after history. According to Kojève, the post-historical state is the guarantor of the resolution of conflict: in his Outline of a Phenomenology of Right, Kojève defined legal right as the role played by state as a “disinterested intervention of a third,” arbitrating a juridical conflict between two parties (Esquisse, 24). Once history has concluded, a universal, homogeneous state will play this role and eliminate all conflict whatsoever, effectively eliminating the political. While this concept of the political has regularly encouraged comparisons with the European Union, and its resolution of conflict between its various states, scholars on Kojève such as Boris Groys, Jeff Love, and Hager Weslati have instead attributed Kojève’s philosophy of the post-historical state to Stalinism. From his early years up until his death, Kojève called himself a “Marxiste de droite” and claimed to be “Stalin’s consciousness,” one who saw in Stalin the herald of the End of History just as Hegel had seen it in Napoleon. Through archival research, Weslati has discovered a letter written in 1940 by Kojève and intended for Stalin. In the letter Kojève claimed that his interpretation of Hegel was written as a philosophical descriptor of Stalinism, and heralded in Stalin “a new opportunity for revolutionary action that will ‘Sovietize’ (that is to say, unify) the realized consciousness of ‘the man of action’ with the revealed self-consciousness of ‘discursive wisdom’” (“Kojève’s letter to Stalin,” 10). Siarhei Biareishyk situates Kojève’s End of History in the context of Stalin’s “socialism in one country,” whereby the advent of post-historical time […] is signaled by the coincidence (identity) of form and content, being and consciousness, thus engendering a condition where change is impossible, precisely because the motor of this change—the disjunction between material conditions and consciousness—has been eliminated. Needless to say, such a coincidence for Stalin is only possible under the societal conditions of socialism/communism, when a homogeneous state as classless society has materialized. (248) Love has similarly claimed that Kojève “develops a concept of freedom as the radical extirpation of individual interest” (“Alexandre Kojève and philosophical Stalinism,” 264). |

政治と普遍国家をめぐる論争 第二次世界大戦後、コジェーヴはフランス経済財務省の顧問職に就いた。これは主に、彼のヘーゲルに関するセミナーに参加したフランス政治家たちの推薦によ るものだ。欧州経済共同体における関税削減を推進した彼の役割は、その政治哲学が欧州連合の創設に影響を与えたという噂を呼んだ。こうした主張の真偽はと もかく、戦後、コジェーヴは政治理論における論争の対立軸に自らを位置づけることとなった。 論争の核心には、政治を定義する本質そのものが横たわっていた。カール・シュミットは『政治的概念』(1927年)において、政治を友と敵の区別と定義 し、政治国家の結束は外部敵への対抗に依存すると論じた。コジェフ後期における最重要著作『権利の現象学の概説』(1943年)において、コジェフはこの シュミットの政治的定義を援用し、次のように主張した。 国家が存在するためには、次の二つの条件が満たされねばならない。第一に、全ての成員が「友」であり、いかなる非成員も敵として扱う社会が存在すること。 第二に、この社会の内部において、「統治者」の集団が「被統治者」を構成する他の成員から明確に区別されていることである。(『権利の現象学概論』143 頁)。 この政治領域における友と敵の対立は、コジェーヴの主従弁証法における承認をめぐる闘争と並行していた。しかし1955年、コジェーヴはシュミットと、対 立のない政治秩序の可能性について書簡のやり取りを始めた。彼らのやり取りの中で、シュミットはヘーゲル哲学において、社会的対立の仮説としての主従弁証 法の通過的性質を考慮すれば、永遠の敵は可能かとコジェーヴに問うた。コジェーヴは歴史は「民族間の敵意の歴史」であり、この敵意は歴史が終結した時に終 わる、と応答した(「書簡集」、107頁)。したがってこの論理では、歴史の終焉後に政治が存在することはありえない。 コジェフによれば、ポストヒストリカルな国家こそが対立解決の保証者である。『権利の現象学概論』において、コジェフは法的権利を「第三者の無関心な介 入」として国家が果たす役割と定義し、二者間の司法的対立を仲裁すると述べた(Esquisse, 24)。歴史が終結すれば、普遍的で均質な国家がこの役割を担い、あらゆる対立を根絶し、政治を事実上消滅させる。この政治概念は欧州連合(EU)との比 較を頻繁に招き、加盟国間の対立解決を想起させるが、ボリス・グロイス、ジェフ・ラブ、ハーガー・ウェスラティらコジェーヴ研究者は、むしろ彼のポスト歴 史的国家哲学をスターリン主義に帰属させている。 コジェーヴは若き日から死に至るまで自らを「右派マルクス主義者」と称し、ヘーゲルがナポレオンに見出したように、スターリンこそが歴史の終焉の先駆者で あると主張した。ウェスラティはアーカイブ調査により、1940年にコジェーヴがスターリン宛てに書いた書簡を発見している。その書簡でコジェーヴは、自 身のヘーゲル解釈がスターリニズムの哲学的記述として書かれたものであり、スターリンにおいて「『行動する人間』の実現された意識と『論理的知恵』の啓示 された自己意識を『ソビエト化』(すなわち統一する)革命的行動の新たな機会」が到来したと宣言している(「コジェーヴのスターリン宛て書簡」、10 頁)。。シアルヘイ・ビャレイシクは、コジェーヴの『歴史の終焉』をスターリンの「一国社会主義」の文脈に位置づける。そこでは ポスト歴史的時代の到来は[…]形式と内容、存在と意識の一致(同一性)によって示され、それゆえ変化が不可能な状態を生み出す。まさにこの変化の原動力 ——物質的条件と意識の乖離——が排除されたからこそである。言うまでもなく、スターリンにとってこのような一致は、社会主義/共産主義という社会的条 件、すなわち階級のない社会としての均質な国家が実現した状況下でのみ可能である。(248) 同様にラブは、コジェーヴが「個人の利害を根絶する自由の概念を展開した」と主張している(「アレクサンドル・コジェーヴと哲学的スターリン主義」、264)。 |

| The “End of History” and Post-Soviet Reception While Kojève’s End of History arguably has the strongest connection to both the European Union and the Soviet Union under Stalin, the most well-known use of Kojève’s theory of the end of history was that of Francis Fukuyama, who in the 1990s claimed the End of History and that liberal democracy would be the definitive, enduring political form worldwide after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Fukuyama’s citation effectively introduced Kojève to an American audience, where he would also find relevance as a political philosopher due to his friendship with Leo Strauss. The end of the Cold War, however, simultaneously introduced Kojève to a receptive post-Soviet audience, itself grappling with the collapse of the Soviet regime as a teleological project and the new assumption of inevitable liberal democracy in Russia. Philosopher Sergei Prozorov has sought to reconceptualize Kojève’s philosophy of the end of history in order to describe the inoperability of the post-Soviet state. If, for Kojève, history concluded when humankind no longer labored, and therefore no longer negated the givens of the world, Prozorov attributes this inaction less to a state of completion but rather to a breakdown in the very sense of societal progress: the end of history is not an event that takes place in accordance with its own inherent logic outside our experience but is rather a possibility that is permanently available to social praxis in the here and now, to anyone in any context. In order words, history does not end by fulfilling its logic but is rather brought to an end in the social practices that suspend its progress. (Ethics of Postcommunism, 8) Prozorov argues that post-Soviet society was inoperable due to its disaffection toward social progress, having effectively exhausted its teleological view of praxis from the Soviet period. Prozorov imagines this exhaustion through the image of Kojève’s Slave, asking “what if we imagine, for a moment, a figure of the Slave who was stopped working without at the same time taking up the fight for recognition” (11). Rather than viewing this abandonment of work pessimistically, Prozorov instead sees in it an opportunity to ask “what politics might be in the absence of any mobilization of humanity for historical tasks of bringing about a bright future” (“Why Giorgio Agamben is an optimist,” 247). Kojève’s philosophy of the end of history has therefore been heavily adapted so as to speak to an aversion to teleological thinking in the post-Soviet sphere. Oksana Timofeeva, for example, has accused Kojève’s philosophy of anthropomorphism, given that labor in Kojève’s philosophy is thought to be unique to humanity. Arguing instead that humans are not the only animals which negate the givens of the world, Timofeeva reads the work of Andrei Platonov through Kojève, Giorgio Agamben, and Georges Bataille in order to attribute to the natural world its own form of historical development: “bare life is the life of animals and plants, but also the life of people who from this very life create happiness and communism […] everything great, including revolution, is made from this meager, weak substance” (Istoriia zhivotnykh, 162). Lastly, philosophers such as Artemy Magun have relied on Kojève’s philosophy of history to reignite the possibility of radical politics and revolution in contemporary Russia. In his Negative Revolution (2008), Magun relies on Kojève’s belief in labor as a negation of the givens in order to define the term negative revolution. Magun employs the term “negative revolution” to highlight the role of symbolic destruction in the creation of the new: “society first unites and destroys—almost unanimously—the symbolic façade of the Old order” in order to then construct a new regime (Otritsatel’naia revoliutsiia, 88). His theory of revolution, inspired by political resistance under Putin, finds direct parallel with Kojève’s dialectical philosophy of history, in which first “the Revolutionary acts consciously not to establish an (ideal) World, but rather to destroy the given World” (Introduction, 170). Trevor Wilson, December 2020 |

「歴史の終焉」とポストソビエトにおける受容 コジェーヴの「歴史の終焉」は、欧州連合とスターリン時代のソビエト連邦の両方との関連性が最も強いと言えるが、コジェーヴの歴史終焉論が最も広く知られ るようになったのは、フランシス・フクヤマによる利用である。フクヤマは1990年代、ソビエト連邦崩壊後、自由民主主義が世界的に決定的かつ永続的な政 治形態となると主張し、「歴史の終焉」を宣言した。フクヤマの引用は、コジェーヴをアメリカ読者に効果的に紹介した。レオ・シュトラウスとの交友関係か ら、彼は政治哲学者としても関連性を認められるようになった。しかし冷戦の終結は同時に、ソ連体制の崩壊という目的論的プロジェクトと、ロシアにおける自 由民主主義の必然性という新たな前提に直面していた受容的なポストソビエトの聴衆にもコジェーヴを紹介したのである。 哲学者セルゲイ・プロゾロフは、ポストソビエト国家の機能不全を説明するため、コジェーヴの歴史終焉論を再概念化しようとした。コジェーヴにとって歴史 は、人類がもはや労働せず、したがって世界の既定事実を否定しなくなった時点で終結した。しかしプロゾロフはこの不作為を、完成の状態というよりむしろ、 社会進歩そのものの感覚の崩壊に帰する。 歴史の終焉とは、我々の経験の外側で内在的論理に従って起こる出来事ではなく、むしろ今ここにおける社会的実践、あらゆる文脈のあらゆる者にとって恒常的 に開かれた可能性である。言い換えれば、歴史はその論理を成就することで終わるのではなく、その進歩を停止させる社会的実践によって終焉を迎えるのだ。 (『ポスト共産主義の倫理』8頁) プロゾロフは、ポストソビエト社会が機能不全に陥ったのは、社会進歩への関心を失い、ソビエト期の実践に対する目的論的見解を事実上枯渇させたためだと論 じる。彼はこの枯渇をコジェーヴの「奴隷」のイメージを通じて想像し、「もしも、承認を求める闘争を同時に放棄せずに労働を停止した『奴隷』の姿を一瞬想 像するとしたら」と問いかける(11頁)。プロゾロフはこの労働放棄を悲観的に見るのではなく、むしろ「人類が明るい未来をもたらすという歴史的課題のた めに動員されない状況下で、政治とは何であるか」を問う機会と捉える(「ジョルジョ・アガンベンが楽観主義者である理由」、247頁)。 したがってコジェーヴの歴史終焉哲学は、ポストソビエト圏における目的論的思考への嫌悪に応えるべく大きく改変されてきた。例えばオクサーナ・ティモ フィーヴァは、コジェーヴ哲学における労働が人類固有のものと考えられている点を指摘し、その哲学を擬人化論と批判している。ティモフェーワは、世界の既 成事実を否定する動物は人間だけではないと反論し、アンドレイ・プラトノフの作品をコジェーヴ、ジョルジョ・アガンベン、ジョルジュ・バタイユを通して読 み解くことで、自然界に独自の歴史的発展形態を帰属させている: 「裸の生とは動物や植物の生命であり、同時にこの生命そのものから幸福と共産主義を創造する人々の生命でもある[…]革命を含むあらゆる偉大なものは、こ の貧弱で脆弱な物質から作られるのだ」(『動物の歴史』162頁)。 最後に、アルテミー・マグーンのような哲学者たちは、現代ロシアにおける急進的政治と革命の可能性を再燃させるため、コジェーヴの歴史哲学に依拠してき た。マグーンは『ネガティブ革命』(2008年)において、労働が既成事実の否定であるというコジェーヴの信念を根拠に、「ネガティブ革命」という概念を 定義している。マグーンは「否定的な革命」という用語を用い、新たな創造における象徴的破壊の役割を強調する。「社会はまず、旧体制の象徴的な表層を── ほぼ満場一致で──結束して破壊する」ことで、新たな体制を構築するのだ(『否定的な革命』88頁)。プーチン政権下での政治的抵抗に触発された彼の革命 論は、コジェフの弁証法的歴史哲学と直接的に類似している。コジェフの哲学では、まず「革命家は(理想的な)世界を構築するためではなく、与えられた世界 を破壊するために意識的に行動する」とされている(序文、170)。 トレバー・ウィルソン、2020年12月 |

| Bibliography Auffret, Dominique. Alexandre Kojève. Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1990. Biareishyk, Siarhei. “Fire-year plan of philosophy: Stalinism after Kojève, Hegel after Stalinism.” Studies in East European Thought 65.3/4 (2013): 243-258. Butler, Judith. Subjects of Desire: Hegelian Reflections in Twentieth-Century France. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999. Fukuyama, Francis. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: The Free Press, 1992. Groys, Boris. Introduction to Antiphilosophy. London: Verso, 2012. Jubara, Annett [Annet Zhubara]. “Ideia kontsa istorii: Vl. Solov’ev i A. Kozhev.” Vladimir Solov’ev i kul’tura Serebrianogo veka. Moscow: Nauka, 2005: 397-401. Kojève, Alexandre. L’Athéisme. Paris: Gallimard, 1998. —. “Colonialism from a European Perspective.” Interpretation vol. 29, no. 1, 2001, pp. 115-130. —. “L’Empire latin. Esquisse d’une doctrine de la politique française (27 août 1945).” La Règle du jeu no. 1, 1990. 89-123. —. Esquisse d’une phénoménologie du droit. Paris: Gallimard, 1981 [1943]. —. [A. V. Kozhevnikov]. “Filosofiia i V.K.P.” Evraziia 16, 9 March 1929, p. 7. —. [Alexander Koschewnikoff]. “Die Geschichtsphilosophie Wladimir Solowjews.” Der Russische Gedanke, vol. 1, no. 3, 1930, pp. 1-20. —. Introduction à la lecture de Hegel: Leçons sur la Phénoménologie de l’Esprit, professées de 1933 à 1939 à l’École des Hautes Études, réunies et publiées par Raymond Queneau. Paris: Gallimard, 1947. —. “La métaphysique religieuse de Vladimir Soloviev (1).” Revue d’histoire et philosophie religieuses 14 (1934): 534-554. —. “La métaphysique religieuse de Vladimir Soloviev (2).” Revue d’histoire et philosophie religieuses 15 (1935): 110-152. —.“L’origine chrétienne de la science moderne.” Mélanges Alexandre Koyré. Vol 2. Paris: Hermann, 1964. Kojève, Alexandre and Carl Schmitt. “Correspondence.” Interpretation vol. 29, no. 1, 2001, pp. 91-115. Love, Jeff. “Alexandre Kojève and philosophical Stalinism.” Studies in East European Thought 70 (2018): 263-271. —. The Black Circle: A Life of Alexandre Kojève. New York: Columbia University Press, 2018. Magun, Artemii. Otritsatel’naia revoliutsiia: K dekonstruktsii politicheskogo sub”ekta. Saint Petersburg: Izdatel’stvo Evropeiskogo universiteta v Sankt-Peterburge, 2008. Penzin, Alexei. “Stalin Beyond Stalin: A Paradoxical Hypothesis of Communism by Alexandre Kojève and Boris Groys.” Crisis and Critique 3.1 (2016): 301-340. Prozorov, Sergei. The Ethics of Postcommunism: History and Social Praxis in Russia. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. —. “Why Giorgio Agamben is an optimist.” Philosophy and Social Criticism 36.9 (2010): 1053-1073. Rossman, Vadim. “Posle filosofii: Kozhev, ‘konets istorii’ i russkaia mysl’.” Neprikosnovennyi zapas 5 (1999). Timofeeva, Oksana. Istoriia zhivotnykh. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2017. Weslati, Hager. “Kojève’s Letter to Stalin.” Radical Philosophy 184 (2014): 7-18. |

参考文献 オーフレ、ドミニク。『アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ』パリ:ベルナール・グラッセ、1990年。 ビアレイシク、シアーヘイ。「哲学の火の年計画:コジェーヴ後のスターリン主義、スターリン主義後のヘーゲル」『東欧思想研究』65巻3/4号(2013年):243-258頁。 バトラー、ジュディス。『欲望の主体:20世紀フランスにおけるヘーゲル的省察』。ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版局、1999年。 フクヤマ、フランシス。『歴史の終わりと最後の人間』。ニューヨーク:フリープレス、1992年。 グロイス、ボリス。『反哲学入門』。ロンドン:ヴァーソ、2012年。 ジュバラ、アネット[アネット・ジュバラ]。「歴史終焉の思想:ヴラジーミル・ソロヴィヨフとアレクサンドル・コジェーヴ」。『ヴラジーミル・ソロヴィヨフと銀の世紀の文化』。モスクワ:ナウカ、2005年:397-401頁。 コジェーヴ、アレクサンドル。『無神論』。パリ:ガリマール、1998年。 ——。「ヨーロッパ的視点からの植民地主義」。『解釈』第29巻第1号、2001年、115-130頁。 ——。「ラテン帝国。フランス政治の教義の概説(1945年8月27日)」。『ゲームのルール』第1号、1990年、89-123頁。 ——。『法の現象学概説』。パリ:ガリマール、1981年[1943年]。 ——[A. V. コジェフニコフ]。『 「Filosofiia i V.K.P.」 Evraziia 16、1929年3月9日、7ページ。 —. [アレクサンダー・コシェヴニコフ]。「Die Geschichtsphilosophie Wladimir Solowjews」 Der Russische Gedanke、第1巻、第3号、1930年、1-20ページ。 —. 『ヘーゲル読解入門:1933年から1939年にかけて高等研究学院で講義された「精神の現象学」を、レイモン・ケノーが編集・出版』。パリ:ガリマール、1947年。 ——「ウラジーミル・ソロヴィエフの宗教的形而上学(1)」。『宗教史・宗教哲学評論』14号(1934年):534-554頁。 ――「ウラジーミル・ソロヴィエフの宗教形而上学(2)」。『宗教史・宗教哲学評論』15号(1935年):110-152頁。 ――「近代科学のキリスト教的起源」。『アレクサンドル・コイレ論文集』第2巻。パリ:エルマン社、1964年。 コジェーヴ、アレクサンドルとカール・シュミット。「書簡集」。『解釈』第29巻第1号、2001年、91-115頁。 ラブ、ジェフ。「アレクサンドル・コジェーヴと哲学的スターリン主義」。『東欧思想研究』70号(2018年):263-271頁。 ——『黒い円環:アレクサンドル・コジェーヴの生涯』ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版局、2018年。 マグン、アルテミー『否定的な革命:政治的主体の脱構築へ』サンクトペテルブルク:サンクトペテルブルク欧州大学出版局、2008年。 ペンジン、アレクセイ。「スターリンを超えたスターリン:アレクサンドル・コジェーヴとボリス・グロイスによる共産主義の逆説的仮説」『危機と批判』3.1号(2016年):301-340頁。 プロゾロフ、セルゲイ。『ポスト共産主義の倫理:ロシアにおける歴史と社会実践』ロンドン:パルグレイブ・マクミラン、2009年。 ――「ジョルジョ・アガンベンが楽観主義者である理由」『哲学と社会批評』36巻9号(2010年)1053-1073頁。 ロスマン、ヴァディム「哲学の後に:コジェーヴ、『歴史の終焉』、そしてロシア思想」『不可侵の蓄積』5号(1999年)。 ティモフィーエワ、オクサーナ。『動物の歴史』。モスクワ:ノヴォエ・リテラトゥルヌエ・オボズレーニエ、2017年。 ウェスラティ、ハーガー。「コジェーヴのスターリンへの手紙」。『ラディカル・フィロソフィー』184号(2014年):7-18頁。 |

| Druskin, Yakov Gaidenko, Piama Ginzburg, Lidiya Horujy, Sergey Khazanov, Boris |

ドルスキン、ヤコフ ガイデンコ、ピアマ ギンズブルグ、リディア ホルジュイ、セルゲイ ハザノフ、ボリス |

| https://filosofia.dickinson.edu/encyclopedia/kojeve-alexandre/ |

アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ(Alexandre Kojève, 1902-1968)アレクサンドル・ヴラジーミロヴィチ・コジェーヴニコフ. ワシリー・カンディンスキー(Wassily Kandinsky, 1866-1944)の父方の甥。

| 1902 | モスクワ旧市街の一角で生まれる。父は 富裕な商人で、父方の伯父は、画家のヴァシーリー・カンディンスキー |

| 1904 | コジェーヴの父は、1904年に勃発し た日露戦争に招集 |

| 1905 | 父、1905年、満洲で戦死。母は、父 と共に満洲に来ていたが、夫の死後、モスクワに帰還するその際、コジェーヴの義父であり、後の夫であるレムキュールと出会う |

| n.d. | コジェーヴは、モスクワでも評判の私立 学校に入学し、個人教授も受ける。以後、コジェーヴは、ラテン語、フランス語、英語、ドイツ語を学ぶ。 |

| 1917 | 二月革命、十月革命の時、コジェーヴは 15歳になっており、彼はこのときから、「哲学日記」という手記を始める。このとき、すでに後にコジェーヴにとっての主要なモチーフとなる「死の観念」に ついての考察が始まっていた。 |

| n.d. | 革命の混乱の中、コジェーヴの義父レム キュールは、賊に暗殺される。この頃コジェーヴは、慢性的な食料難のため、闇市に出入りし、その咎で投獄される。仲間たちは銃殺されるが、コジェーヴ自身 は親戚の口利きによって助かる。 |

| これら一連の経験が、コジェーヴをして大きく動揺せしめた。このこと

が、彼に「死=実在せざること」をどう理解するか、ということについて、生涯を通じて考察させるきっかけとなった。この「死についての考察」は、後に

『ヘーゲル読解入門』において、大きく展開されることになる。 |

|

| 1920 |

1920年、コジェーヴは祖国を捨て、ドイツに亡命する。1926年に

至るまで、ドイツのハイデルベルクとベルリンで研究を続ける。この間彼は、ドイツ語、哲学、東洋語(サンスクリット語、中国語、チベット語)、ロシア文学

について学ぶ。 |

| 1926 |

1926年、ハイデルベルクで学位を取得したコジェーヴは、フランス・

パリに移り、ソルボンヌ大学で研究生活を続ける。この頃、高等研究院で教鞭をとっていた科学史家アレクサンドル・コイレと知り合い、1933年(『精神現

象学』講義の始まる年)まで、高等研究院で研究活動をした。ソルボンヌでは数学と物理学、高等研究院では宗教哲学と東洋語を主に研究する。この頃、マル

ティン・ハイデッガーは『存在と時間』を著している。 |

| 1933 |

1933年、「ソロヴィヨフの宗教哲学」という論文を著す。1933年 (『精神現象学』講義の始まる年)まで、高等研究院で研究活動をした。 |

| 1934 |

「ソロヴィヨフの宗教哲学」という論文を著す。この論文により、

1934年、高等研究院の修了証書を取得。この頃、ヒトラーが首相に就任。同年、コイレがカイロに招聘されることになり、それまで高等研究院で行われてい

た講義がコジェーヴに託される。夏の間、準備のために『精神現象学』を数度、読み返す。このときに、「ナポレオンに具現化された歴史の終焉」という手がか

りを見付け、このことが、コジェーヴのヘーゲル解釈に大きく影響することになる。またこの頃、講義と共に著述活動も活発になり、それらはフランス語、ドイ

ツ語、ロシア語で著され、いくつかの雑誌に掲載される。 |

| 1943 |

1943年、コジェーヴの記念碑的著作である『法の現象学(権利の現象

学)』を著す。 |

| 1945 |

1945年、ヒトラー自殺。ドイツ政府は無条件降伏。原爆投下。コ

ジェーヴは、フランスの政策に関する覚書を数編著し、また、講義の参加者の1人であるロベール・マルジョラン(フランス対外経済関係局の局長)によって、

特務官に任ぜられる。この年以降、コジェーヴはフランス政府の仕事を続けることになる。 |

| 1947 |

1947年、レイモン・クノーにより、高等研究院での講義録である

『ヘーゲル読解入門』が公刊される。6月、米国のマーシャル国務長官がヨーロッパ支援計画(マーシャル・プラン)を発表する[1]が、ソ連がこれを拒否

[2]。7月、ヨーロッパ16か国はパリに集まり、ヨーロッパ経済協力委員会を創設[3]。コジェーヴはハバナで開催された国際貿易機関に関する会議に参

加。 |

| 1948 |

1948年3月、53か国がハバナ憲章に調印。これに、コジェーヴはフ

ランス代表団の一員として参加。この憲章をアメリカが批准しなかったため、これは発効しなかった。そのため、暫定的に形成されたのが、GATTである

[4]。4月、トルーマンが対外援助法に署名し、マーシャル・プランが始動する[5]。援助金はヨーロッパにおける機関設立によって投入されることになっ

たが、そのための機関として、ヨーロッパ経済協力機構が創設される[6]。事務総長はロベール・マルジョランであり[7][8]、コジェーヴは対外経済関

係局特務官として活動。 |

| 1953 |

1953年、コジェーヴは結核に冒され政府活動を停止、その間に、自身

の知の体系の充実に着手する。「カント論」、「概念・時間・言説」の執筆を始める。この年の3月、スターリンが死去。その死に際して、コジェーヴは「父を

失ったようだ」と語った。 |

| 1959 |

日本を訪問し、感銘を伴い帰国する。そこに、「歴史の終焉」後の人間の

存在様式のある形を見出した。 |

| 1962 |

1962年、ジュネーヴで行われた国連貿易開発会議の準備会議に、フラ

ンス代表として出席し、貧しい国々のために演説をする。彼はそのとき、ケネディ・ラウンドに大きな期待を寄せていたが、しかし11月、ケネディは暗殺され

る。 |

| 1964 |

1964年になると、交渉はジョンソンの下で開始され、コジェーヴはこ

れに参加。 |

| 1967 |

定年になる時期だったが、官僚としての活動を続けることを望み、将来の

国際貿易問題検討会の座長に任命される。 |

| 1968 |

歴史の終わりに関して、『ヘーゲル読解入門』の注に日本のことを付け加

える。6月、ブリュッセルにおける共同市場の会議に出席している最中、心臓発作で急死した(享年66歳?か)。 |

| 1987 |

『ヘーゲル読解入門――『精神現象学』を読む』

上妻精・今野雅方訳、国文社、1987年 |

| 1996-2015 |

『法の現象学』

今村仁司・堅田研一訳、法政大学出版局、1996年、新装版2015年 |

| 2000 |

『概念・時間・言説――ヘーゲル「知の体系」改訂の試み』

三宅正純・根田隆平・安川慶治訳、法政大学出版局、2000年 |

| 2001 |

ドミニック・オフレ 『評伝 アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ』

今野雅方訳、パピルス、2001年。 |

| 2010 |

『権威の概念』 今村真介訳、法政大学出版局、2010年 |

| 2015 |

『無神論』 今村真介訳、法政大学出版局、2015年 |

★アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ伝

| Alexandre

Kojève[a]

(born Aleksandr Vladimirovich Kozhevnikov;[b] 28 April 1902 – 4 June

1968) was a Russian-born French philosopher and international civil

servant whose philosophical seminars had some influence on 20th-century

French philosophy, particularly via his integration of Hegelian

concepts into twentieth-century continental philosophy.[2][3] |

アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ[a](Aleksandr

Vladimirovich Kozhevnikov、[b] 1902年4月28日 -

1968年6月4日)はロシア生まれのフランスの哲学者、国際公務員であり、その哲学セミナーは20世紀のフランス哲学、特に20世紀の大陸哲学へのヘー

ゲル概念の統合を通じて一定の影響を与えた[2][3]。 |

Life Kojève in Berlin, 1922 Aleksandr Vladimirovich Kozhevnikov was born in the Russian Empire to a wealthy and influential family. His uncle was the abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky, about whose work he would write an influential essay in 1936. He was educated at the University of Berlin and the University of Heidelberg, both in Germany. In Heidelberg, he completed in 1926 his PhD thesis on the Russian religious philosopher Vladimir Soloviev's views on the union of God and man in Christ under the direction of Karl Jaspers. The title of his thesis was Die religiöse Philosophie Wladimir Solowjews (The Religious Philosophy of Vladimir Soloviev). Early influences included the philosopher Martin Heidegger and the historian of science Alexandre Koyré. Kojève spent most of his life in France and from 1933 to 1939 delivered in Paris a series of lectures on Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's work Phenomenology of Spirit. After the Second World War, Kojève worked in the French Ministry of Economic Affairs as one of the chief planners to form the European Economic Community. Kojève studied and used Sanskrit, Chinese, Tibetan, Latin and Classical Greek. He was also fluent in French, German, Russian and English.[4] Kojève died in 1968, shortly after giving a talk to civil servants and state representatives for the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in Brussels on behalf of the French government.[5][6] |

人生 1922年、ベルリンにて アレクサンドル・ウラジーミロヴィチ・コジェーヴニコフは、ロシア帝国の裕福で影響力のある家庭に生まれた。叔父は抽象画家のワシリー・カンディンスキー で、1936年に彼の作品について影響力のあるエッセイを書くことになる。ドイツのベルリン大学とハイデルベルク大学で教育を受ける。ハイデルベルクで は、カール・ヤスパースの指導の下、1926年にロシアの宗教哲学者ウラジーミル・ソロヴィエフのキリストにおける神と人間の結合に関する見解に関する博 士論文を完成させた。論文のタイトルは『ウラジーミル・ソロヴィエフの宗教哲学』(Die religiöse Philosophie Wladimir Solowjews)であった。 初期には哲学者のマルティン・ハイデガーや科学史家のアレクサンドル・コイレに影響を受けた。コジェーヴは人生の大半をフランスで過ごし、1933年から 1939年にかけて、ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルの『精神の現象学』に関する一連の講義をパリで行った。第二次世界大戦後、コジェー ヴはフランス経済省に勤務し、欧州経済共同体結成の主席計画者の一人として活躍した。 コジェーヴは、サンスクリット語、中国語、チベット語、ラテン語、古典ギリシア語を学び、使用した。フランス語、ドイツ語、ロシア語、英語にも堪能だった [4]。 コジェーヴは1968年、フランス政府を代表してブリュッセルで欧州経済共同体(現在の欧州連合)のために公務員や国家代表に講演を行った直後に死去した [5][6]。 |

| Hegel lectures Although not an orthodox Marxist,[7] Kojève was known as an influential and idiosyncratic interpreter of Hegel, reading him through the lens of both Karl Marx and Martin Heidegger. The well-known end of history thesis advanced the idea that ideological history in a limited sense had ended with the French Revolution and the regime of Napoleon and that there was no longer a need for violent struggle to establish the "rational supremacy of the regime of rights and equal recognition". Kojève's end of history is different from Francis Fukuyama's later thesis of the same name in that it points as much to a socialist-capitalist synthesis as to a triumph of liberal capitalism.[8][9] Kojève's lectures on Hegel were collected, edited and published by Raymond Aron in 1947, and published in abridged form in English in the now classic Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit. His interpretation of Hegel has been one of the most influential of the past century. His lectures were attended by a small but influential group of intellectuals including Raymond Queneau, Georges Bataille, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, André Breton, Jacques Lacan, Raymond Aron, Michel Leiris, Henry Corbin and Éric Weil. His interpretation of the master–slave dialectic was an important influence on Jacques Lacan's mirror stage theory. Other French thinkers who have acknowledged his influence on their thought include the post-structuralist philosophers Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. Friendship with Leo Strauss Kojève had a close and lifelong friendship with Leo Strauss which began when they were philosophy students in Berlin. The two shared a deep philosophical respect for each other. Kojève would later write that he "never would have known [...] what philosophy is" without Strauss.[10] In the 1930s, the two began a debate on the relation of philosophy to politics that would come to fruition with Kojève's response to Strauss' On Tyranny. Kojève, a senior statesman in the French government, argued that philosophers should have an active part in shaping political events. On the other hand, Strauss believed that philosophy and politics were fundamentally opposed and that philosophers should not have a substantial role in politics, noting the disastrous results of Plato in Syracuse. Philosophers should influence politics only to the extent that they can ensure that philosophical contemplation remains free from the seduction and coercion of power.[11] In spite of this debate, Strauss and Kojève remained friendly. In fact, Strauss would send his best students to Paris to finish their education under Kojève's personal guidance. Among these were Allan Bloom, who endeavored to make Kojève's works available in English and published the first edition of Kojève's lectures in English, and Stanley Rosen. |

ヘーゲル講義 コジェーヴは正統的なマルクス主義者ではなかったが[7]、ヘーゲルをカール・マルクスとマルティン・ハイデガー両方のレンズを通して読み解き、影響力の ある特異な解釈者として知られていた。よく知られた歴史の終わりというテーゼは、限定的な意味でのイデオロギー史はフランス革命とナポレオン政権で終わ り、「権利と平等承認の体制の合理的優位」を確立するための暴力的な闘争はもはや必要ないという考えを提唱した。コジェーヴの歴史の終わりは、フランシ ス・フクヤマの後の同名のテーゼとは異なり、自由資本主義の勝利と同様に社会主義-資本主義の統合を指し示している[8][9]。 コジェーヴのヘーゲルに関する講義は、1947年にレイモンド・アロンによって収集、編集、出版され、現在では古典的な『ヘーゲル読解入門』として要約さ れた形で英語で出版されている: 精神現象学講義』である。彼のヘーゲル解釈は、前世紀において最も影響力のあるもののひとつである。彼の講義には、レイモン・クノー、ジョルジュ・バタイ ユ、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティ、アンドレ・ブルトン、ジャック・ラカン、レイモン・アロン、ミシェル・レイリス、ヘンリー・コルバン、エリック・ワイル など、少数ではあるが影響力のある知識人たちが参加した。彼の主従弁証法の解釈は、ジャック・ラカンの鏡像段階説に重要な影響を与えた。彼の思想への影響 を認めるフランスの思想家には、ポスト構造主義の哲学者ミシェル・フーコーやジャック・デリダがいる。 レオ・シュトラウスとの友情 コジェーヴはレオ・シュトラウスと、ベルリンで哲学を学ぶ学生時代に始まった親密で生涯にわたる友情を持っていた。二人は互いに哲学的に深い尊敬の念を共 有していた。1930年代、2人は哲学と政治の関係について議論を始め、シュトラウスの『専制について』に対するコジェーヴの回答によって結実した。 フランス政府の高官であったコジェーヴは、哲学者は政治的出来事の形成に積極的に関与すべきだと主張した。一方、シュトラウスは、哲学と政治は根本的に対 立するものであり、哲学者は政治に実質的な役割を持つべきではないと考え、シラクサにおけるプラトンの悲惨な結果に言及した。哲学者は、哲学的思索が権力 の誘惑や強制から自由であり続けることを保証できる範囲においてのみ、政治に影響を与えるべきである[11]。 このような論争にもかかわらず、シュトラウスとコジェーヴは友好的であり続けた。実際、シュトラウスは優秀な学生をパリに送り、コジェーヴの人格指導の下 で教育を受けさせた。その中には、コジェーヴの著作を英語で読めるようにしようと努力し、コジェーヴの講義の初版を英語で出版したアラン・ブルームや、ス タンリー・ローゼンもいた。 |

| Political views Marxism According to his own account shortly before his death, Kojève was a communist from youth, and was enthusiastic regarding Bolshevik revolution. However, he "knew that the establishment of communism meant thirty terrible years.", so he ran away.[12] From now on, he once claimed in his letter to Tran Duc Thao, dated October 7, 1948, that his "... course was essentially a work of propaganda intended to strike people's minds. This is why I consciously reinforced the role of the dialectic of Master and Slave and, in general, schematized the content of phenomenology."[13][14] His articles from 1920s, talked positively about the USSR, saw it as something developing new. In an article to magazine Yevraziya, a left Eurasianist journal, he praised the CPSU's struggle against bourgeois philosophy, arguing that it would lead to something new, whether one calls it proletarian or not:[15] "(...) Marxist philosophy can express the world view of the new ruling class and new culture, and every other philosophy is subject to destruction. (...) Everything currently taking place in the USSR is so significant and new that any assessment of the Party's cultural or 'philosophical' politics cannot be founded on preconceived cultural values or preformed philosophical systems. (...) the question of the Party's 'philosophical politics' can be assessed, it seems, not entirely negatively. (...) Toward the end of the nineteenth century Western thought effectively concluded its development [...] turning into a philosophical school of 'scholasticism' in the popular, negative sense of the term. (...) being a philosopher, one can nevertheless welcome 'philosophical politics' leading to the complete prohibition of the study of philosophy. (...) The Party is fighting against bourgeois culture in the name of proletarian culture. Many find the word 'proletariat' not to their taste. This is after all only a word. The essence of the matter does not change, and the essence consists in the fact that a battle is raging with something old, already existing, in the name of something new, which has yet to be created. Anyone who will welcome the appearance of a truly new culture and philosophy – either because it will be neither Eastern nor Western, but Eurasian, or simply because it will be new and lively in contrast to the already crystallised and dead cultures of the West and East – should also accept everything that contributes to this appearance. It seems to me, for the time being of course, that the Party's policies directed against bourgeois (that is, ultimately Western) culture is really preparation for a new culture of the future. (...)" Mark Lilla notes that Kojève rejected the prevailing concept among some European intellectuals of the 1930s that capitalism and democracy were failed artifacts of the Enlightenment that would be destroyed by either communism or fascism.[16] While initially somewhat more sympathetic to the Soviet Union than the United States, Kojève devoted much of his thought to protecting western European autonomy, particularly relating to France, from domination by either the Soviet Union or the United States. He believed that the capitalist United States represented right-Hegelianism while the state-socialist Soviet Union represented left-Hegelianism. Thus, victory by either side, he posited, would result in what Lilla describes as "a rationally organized bureaucracy without class distinctions".[17] |

政治的見解 マルクス主義 亡くなる直前の本人の証言によると、コジェーヴは若い頃から共産主義者で、ボリシェヴィキ革命に熱狂していた。1948年10月7日付のトラン・ドゥッ ク・タオ宛の手紙の中で、コジェーヴは「......自分の講座は本質的に、人々の心を打つことを意図したプロパガンダの仕事であった。だからこそ、私は 意識的に主人と奴隷の弁証法の役割を強化し、一般的に現象学の内容を図式化したのである」[13][14] 1920年代からの彼の記事は、ソ連について肯定的に語り、ソ連を何か新しいものを発展させるものとして見ていた。ユーラシア左派の雑誌『イェヴラジヤ』 への寄稿で、彼はブルジョア哲学に対するCPSUの闘争を賞賛し、それがプロレタリア的であるか否かにかかわらず、何か新しいものにつながると論じている [15]。 「マルクス主義哲学は、新しい支配階級と新しい文化の世界観を表現することができる。(...)現在ソ連で起こっているすべてのことは、非常に重要で新し いことであり、党の文化的政治や『哲学的』政治に対するいかなる評価も、先入観にとらわれた文化的価値観やあらかじめ形成された哲学的体系に基礎を置くこ とはできない。(中略)党の「哲学的政治」の問題は、完全に否定的に評価できるわけではないようだ。(...)19世紀の終わりには、西洋思想は事実上、 その発展を終え[...]、一般的で否定的な意味での「スコラ哲学」の哲学学派となった。(...)哲学者であれば、哲学の研究が完全に禁止される「哲学 的政治」を歓迎することができる。(中略)党は、プロレタリア文化の名の下に、ブルジョア文化と戦っている。多くの人は、「プロレタリアート」という言葉 は好みに合わないと思う。結局のところ、これは単なる言葉にすぎない。問題の本質は変わらない。その本質は、まだ創造されていない新しいものの名の下に、 すでに存在する古いものとの戦いが繰り広げられているという事実にある。真に新しい文化や哲学の出現を歓迎する人は、それが東洋でも西洋でもなくユーラシ ア的なものであるため、あるいは単に、西洋や東洋のすでに結晶化し死滅した文化とは対照的に新しく生き生きとしたものであるため、この出現に貢献するすべ てのものを受け入れるべきである。もちろん、当面は、ブルジョア(つまり究極的には西洋)文化に反対する党の政策は、未来の新しい文化のための準備なのだ と私には思える。(...)」 マーク・リラは、コジェーヴが、資本主義と民主主義は啓蒙主義の失敗作であり、共産主義かファシズムのどちらかによって破壊されるだろうという1930年 代のヨーロッパの一部の知識人の間で一般的だった考え方を否定していたと指摘している[16]。 コジェーヴは、当初はアメリカよりもソ連にやや同情的であったが、西ヨーロッパの自治、特にフランスに関する自治をソ連やアメリカによる支配から守ること に思想の多くを捧げた。彼は、資本主義のアメリカが右ヘーゲル主義を代表し、国家社会主義のソ連が左ヘーゲル主義を代表すると考えていた。したがって、ど ちらか一方が勝利すれば、リラが言うところの「階級的区別のない合理的に組織された官僚制」になると彼は仮定していた[17]。 |

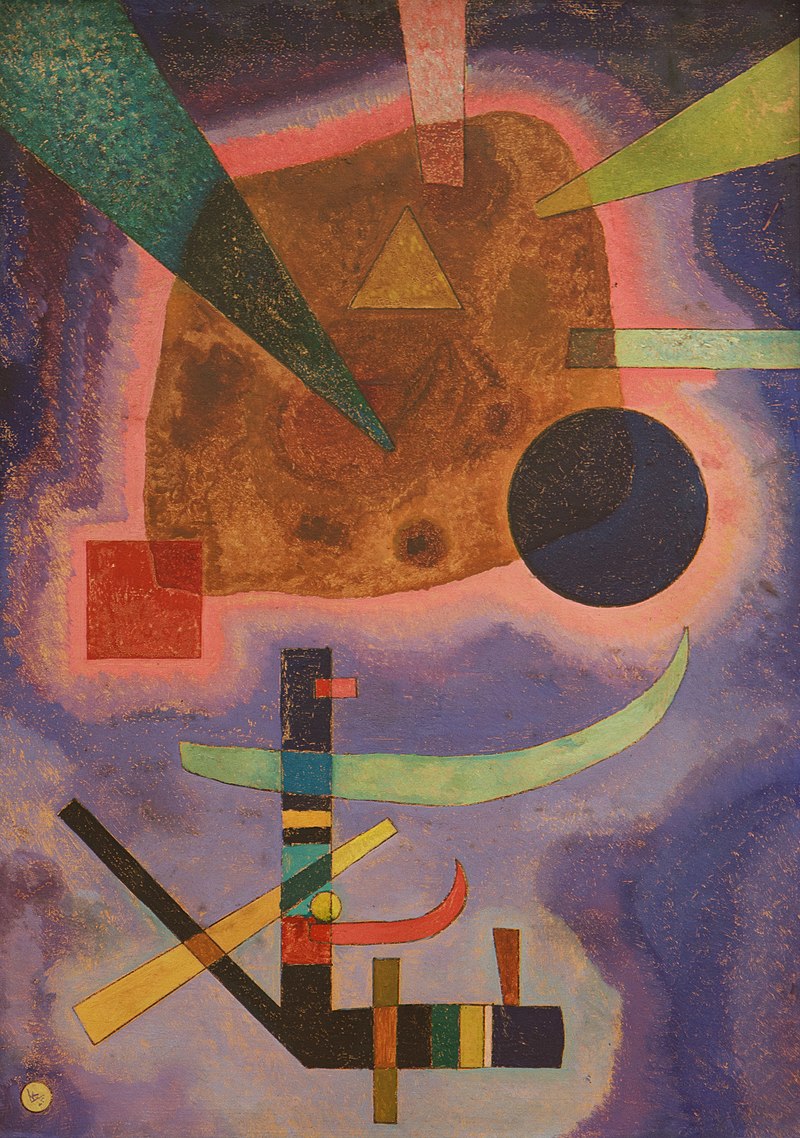

| Stalin and the Soviet Union Kojève's views of Stalin, while changing after World War II, was positive. Kojève's interest for Stalin, however, might have been continued, whether positive or negative, after World War II. According to Isaiah Berlin, a contemporary of Kojève and his friend, during their meeting in Paris c. 1946-1947, they talked about Stalin and the USSR. Berlin comments on his relations with Stalin, saying "(...) Kojéve was an ingenious thinker and imagined that Stalin was one too. (...) He said that he wrote to Stalin, but received no reply. I think that perhaps he identified himself with Hegel, and Stalin with Napoleon. (...)"[18] The most important result of this era was Kojève's work addressed to Stalin, Sofia, filo-sofia i fenomeno-logia (Sophia, Philo-sophy and Phenomeno-logy), a manuscript of more than 900 pages that was penned between 1940 and 1941.[19] In that manuscript, according to Boris Groys, Kojève defended his thesis that the "universal and homogeneous state in which the Sage can emerge and live is none other than Communism" and "scientific Communism of Marx–Lenin–Stalin is an attempt to expand the philosophical project to its ultimate historical and social borders". According to Groys, "Kojève sees the end of history as the moment of the spread of wisdom through the whole population – the democratization of wisdom; a universalization that leads to homogenization. He believes that the Soviet Union moves towards the society of wise men in which every member will have self-consciousness."[20] According to Weslati, several versions of Sofia, including a typesetted copy, had been completed in the first week of March 1941, and one of them was given to Soviet vice consul in person by Kojève. Soviet consul "... promised to send the letter with the next diplomatic bag to Moscow." However, "[l]ess than three months later, the embassy and its contents would be put to the torch by Nazi troops."[19] It's not known whether Kojève's work had reached the USSR or was burned with the embassy. In 1999, Le Monde published an article reporting that a French intelligence document showed that Kojève had spied for the Soviets for over thirty years.[21][22]  Three Elements, by Wassily Kandinsky (1925). The painting belonged to Kojève and later to his widow Nina. Although Kojève often claimed to be a Stalinist,[23] he largely regarded the Soviet Union with contempt, calling its social policies disastrous and its claims to be a truly classless state ludicrous. Kojève's cynicism towards traditional Marxism as an outmoded philosophy in industrially well-developed capitalist nations prompted him to go as far as idiosyncratically referring to capitalist Henry Ford as "the one great authentic Marxist of the twentieth century".[24] He specifically and repeatedly called the Soviet Union the only country in which 19th-century capitalism still existed. His Stalinism was quite ironic, but he was serious about Stalinism to the extent that he regarded the utopia of the Soviet Union under Stalin and the willingness to purge unsupportive elements in the population as evidence of a desire to bring about the end of history and as a repetition of the Reign of Terror of the French Revolution.[25] |

スターリンとソ連 コジェーヴのスターリン観は、第二次世界大戦後に変化したものの、肯定的なものであった。しかし、コジェーヴのスターリンに対する関心は、肯定的であれ否 定的であれ、第二次世界大戦後も続いていたのかもしれない。コジェーヴと同時代の友人であるアイザイア・バーリンによれば、1946年から1947年頃に パリで会った際、二人はスターリンとソ連について語り合った。コジェーヴは独創的な思想家であり、スターリンもそうであると想像していた。(スターリンに 手紙を書いたが、返事はなかったという。おそらく彼は自分自身をヘーゲルと同一視し、スターリンをナポレオンと同一視していたのだと思う。(...)" [18] この時代の最も重要な成果は、コジェーヴがスターリンに宛てた著作『ソフィア、フィロソフィア、現象学』(Sofia, filo-sofia i fenomeno-logia)で、1940年から1941年にかけて書かれた900ページを超える原稿であった。 [19] ボリス・グロイスによれば、コジェーヴはその原稿の中で、「賢者が出現し生きることのできる普遍的で均質な国家は共産主義にほかならない」「マルクス= レーニン=スターリンの科学的共産主義は、哲学的プロジェクトをその究極的な歴史的・社会的境界まで拡大しようとする試みである」というテーゼを擁護し た。グロイスによれば、「コジェーヴは、歴史の終わりを、全人口を通じて知恵が広がる瞬間、つまり知恵の民主化、均質化につながる普遍化としてとらえてい る」。コジェーヴは、ソビエト連邦が、すべての構成員が自意識を持つようになる賢者の社会へと向かうと信じている」[20]。 ウェスラーティによると、1941年3月の第1週には、活字を含む『ソフィア』のいくつかの版が完成しており、そのうちの1つがコジェーヴによってソ連副 領事に人格的に渡された。ソ連領事は「...次の外交鞄と一緒にモスクワに送ることを約束した」。しかし、「3カ月も経たないうちに、大使館とその内容は ナチス軍によって放火されることになった」[19]。コジェーヴの作品がソ連に届いたのか、大使館とともに燃やされたのかはわかっていない。 1999年、ル・モンド紙は、コジェーヴが30年以上にわたってソビエトのためにスパイ活動をしていたことを示すフランスの諜報機関の文書があったという 記事を掲載した[21][22]。  ワシリー・カンディンスキー作『3つの要素』(1925年)。この絵はコジェーヴが所有していたもので、後に未亡人のニーナが所有していた。 コジェーヴはしばしばスターリニストであると主張していたが[23]、ソ連を軽蔑の目で見ており、その社会政策は悲惨であり、真に階級なき国家であるとい う主張は滑稽であった。工業的に発達した資本主義国民においては、伝統的なマルクス主義は時代遅れの哲学であるというコジェーヴの皮肉は、資本主義者であ るヘンリー・フォードを「20世紀における唯一の偉大な本物のマルクス主義者」と特異に呼ぶまでに至らせた[24]。彼のスターリニズムは非常に皮肉なも のであったが、スターリンのもとでのソビエト連邦のユートピアと、国民の中の支持しない要素を粛清する意欲を、歴史の終わりをもたらしたいという願望の証 拠であり、フランス革命のテロールの治世の繰り返しであるとみなす程度には、彼はスターリニズムに対して真剣であった[25]。 |

| Kojève and Zionism According to Isaiah Berlin, Kojève was not fond of the idea of a state of Israel. Berlin's several different accounts, like the ones published in the Jewish Chronicle in 1973, in The Jerusalem Report in October 1990, and in his interview with Ramin Jahanbegloo in 1991 (also published as a book), are about his meeting with Kojève. According to the 1973 account, "ten years ago or more" he was "dining in Paris with a distinguished historian of philosophy who was also a high official of the French Government", namely, Kojève.[26] 1990 account also records that they were talking in Russian.[27] While talking, the issue of Israel and Zionism was also discussed. Kojève, who "was plainly taken aback" at Berlin's defence of Zionism, asked Berlin:[26] "[...] Jews [...], with their rich and extraordinary history, miraculous survivors from the classical age of our common civilisation – that this fascinating people should choose to give up its unique status, and for what? To become Albania? How could they want this? Was this not [...] a failure of national imagination, a betrayal of all that the Jews were and stood for?" In return, according to the interview with Jahanbegloo, Berlin replied: "For the Jews to be like Albania constitutes progress. Some 600,000 Jews in Romania were trapped like sheep to be slaughtered by the Nazis and their local allies. A good many escaped. But 600,000 Jews in Palestine did not leave because Rommel was at their door. That is the difference. They considered Palestine to be their own country, and if they had to die, they would die not like trapped animals, but for their country."[28][29] "We reached no agreement.", records Berlin.[26] |

コジェーヴとシオニズム アイザイア・バーリンによれば、コジェーヴはイスラエルという国家の構想が好きではなかった。1973年の『ユダヤ人クロニクル』誌、1990年10月の 『エルサレム・レポート』誌、1991年のラミン・ジャハンベグルーとのインタビュー(単行本化もされている)など、バーリンはコジェーヴとの出会いにつ いていくつかの異なる証言をしている。 1973年の記述によれば、「10年以上前」、彼は「フランス政府の高官でもある著名な哲学史家、すなわちコジェーヴとパリで会食」していた[26]。 1990年の記述には、彼らがロシア語で話していたことも記録されている[27] 。コジェーヴは、ベルリンのシオニズム擁護に「あきれ果て」、ベルリンに次のように尋ねた[26]。 「ユダヤ人[......]は、その豊かで並外れた歴史を持ち、われわれ共通の文明の古典的時代からの奇跡的な生き残りである。アルバニアになるためか? どうしてこんなことを望むのか?これはナショナリズムの失敗であり、ユダヤ人という存在とその象徴のすべてに対する裏切りではないのか? ジャハンベグルとのインタビューによると、ベルリンはこう答えたという: 「ユダヤ人がアルバニアのようになることは進歩である。ルーマニアにいた約60万人のユダヤ人は、ナチスとその同盟国によって、羊のように捕らえられ虐殺 された。逃げ延びた者も大勢いた。しかし、パレスチナの60万人のユダヤ人は、ロンメルが彼らの前に立ちはだかったので、逃げなかった。そこが異なる。彼 らはパレスチナを自分たちの国だと考えていたし、もし死ななければならないとしたら、罠にかけられた動物のようにではなく、自分たちの国のために死ぬだろ う」[28][29] 「私たちは合意に達しなかった」とベルリンは記録している[26]。 |

| Critics In a commentary on Francis Fukuyama's The End of History and the Last Man, the traditionalist conservative thinker[30][31] Roger Scruton calls Kojève "a life-hating Russian at heart, a self-declared Stalinist, and a civil servant who played a leading behind-the-scenes role in establishing both the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the European Economic Community" and states his opinion that Kojève was "a dangerous psychopath".[32] |

批評家 フランシス・フクヤマの『歴史の終わりと最後の人間』の解説で、伝統主義的な保守思想家[30][31]であるロジャー・スクルトンはコジェーヴを「根っ からの生命を憎むロシア人であり、スターリニストを自認し、関税貿易一般協定と欧州経済共同体の設立において舞台裏で主導的な役割を果たした公務員」と呼 び、コジェーヴは「危険な精神病質者」であったという意見を述べている[32]。 |

| His works Kojève's correspondence with Leo Strauss has been published along with Kojève's critique of Strauss's commentary on Xenophon's Hiero.[11] In the 1950s, Kojève also met the rightist legal theorist Carl Schmitt, whose "Concept of the Political" he had implicitly criticized in his analysis of Hegel's text on "Lordship and Bondage" [additional citation(s) needed]. Another close friend was the Jesuit Hegelian philosopher Gaston Fessard, whom with also had correspondence. In addition to his lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit, Kojève's other publications include a little noticed book on Immanuel Kant and articles on the relationship between Hegelian and Marxist thought and Christianity. His 1943 book Esquisse d'une phenomenologie du droit, published posthumously in 1981, elaborates a theory of justice that contrasts the aristocratic and bourgeois views of the right. Le Concept, le temps et le discours extrapolates on the Hegelian notion that wisdom only becomes possible in the fullness of time. Kojève's response to Strauss, who disputed this notion, can be found in Kojève's article "The Emperor Julian and his Art of Writing".[33] Kojève also challenged Strauss' interpretation of the classics in the voluminous Esquisse d'une histoire raisonnée de la pensée païenne which covers the pre-Socratic philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, as well as Neoplatonism. While the first volume of the previous work was still published during his life-time, most of his writings remained unpublished until recently. These are becoming the subject of increased scholarly attention. The books that have so far been published are the two remaining volumes of the Esquisse d'une histoire raisonnée de la pensée païenne (1972, 1973 [1952]), Outline of a Phenomenology of Right (1981 [1943]), L'idée du déterminisme dans la physique classique et dans la physique moderne (1990 [1932]), Le Concept, le Temps et Le Discours (1990 [1952]), L'Athéisme (1998 [1931]), The Notion of Authority (2004 [1942]), and Identité et Réalité dans le "Dictionnaire" de Pierre Bayle (2010 [1937]). Several of his shorter texts are also gathering greater attention and some are being published in book form as well. |

コジェーヴの著作 1950年代、コジェーヴは右派の法学者カール・シュミットとも知り合い、ヘーゲルの「領主権と束縛」に関するテクストの分析において、彼の「政治的概 念」を暗に批判していた[11]。もう一人の親友はイエズス会のヘーゲル哲学者ガストン・フェサールであり、彼とも文通をしていた。 精神現象学』に関する講義のほか、コジェーヴの出版物には、イマヌエル・カントに関する本や、ヘーゲル思想やマルクス主義思想とキリスト教との関係に関す る論文などがある。1943年に出版された『権利の現象学』(Esquisse d'une phenomenologie du droit)は、1981年に遺著として出版され、貴族的な権利観とブルジョア的な権利観を対比させた正義論を展開している。Le Concept, le temps et le discours(概念、時間、そして言説)』は、知恵は時間の充足の中で初めて可能になるというヘーゲル的な概念を外挿したものである。この考え方に異 論を唱えたシュトラウスに対するコジェーヴの反論は、コジェーヴの論文『ユリウス皇帝とその文章術』に見られる[33]。コジェーヴはまた、ソクラテス以 前の哲学者であるプラトンやアリストテレス、新プラトン主義を扱った膨大な『Esquisse d'une histoire raisonnée de la pensée païenne』の中で、シュトラウスの古典解釈に異議を唱えている。前著の第1巻はまだ生前に出版されていたが、彼の著作のほとんどは最近まで未発表の ままだった。これらは、学術的に注目されるようになってきている。 現在までに出版されているのは、『Esquisse d'une histoire raisonnée de la pensée païenne』(1972年、1973年[1952年])の残り2巻、『Outline of a Phenomenology of Right』(1981年[1943年])である、 L'idée du déterminisme dans la physique and dans la physique moderne (1990 [1932]), Le Concept, le Temps et Le Discours (1990 [1952]), L'Athéisme (1998 [1931]), The Notion of Authority (2004 [1942]), and Identité et Réalité dans le 「Dictionnaire」 de Pierre Bayle (2010 [1937]). また、彼の短いテクストにも注目が集まっており、書籍化されているものもある。 |

| Bibliography Books Alexander Koschewnikoff, Die religiöse Philosophie Wladimir Solowjews. Heidelberg Univ., Dissertation 1926. (Online) Alexander Koschewnikoff, Die Geschichtsphilosophie Wladimir Solowjews (Sonderabdruck). Verlag von Friedrich Cohen. 1st Ed., 1930. Bonn. Offprint of an article he penned (see below section). Alexandre Kojève, Introduction à la Lecture de Hegel. Paris, Gallimard, 1947. Alexandre Kojève (ed. Allan Bloom, transl. James H. Nichols, Jr.), Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit. Basic Books, Inc., Publishers. 1st Ed., 1969. New York-London. / Cornell University Press. 1980. Ithaca. An abridged translation edited by Allan Bloom, roughly half of the original book. According to the translator's note: "The present translation includes slightly under one half of the original volume: the pasages translated correspond to pp. 9-34, 161-195, 265-267, 271-291, 336-380, 427-443, 447-528, and 576-597 of the French text." (p. XIII) Alexandre Kojève (transl. Joseph J. Carpino), The idea of death in the philosophy of Hegel. Interpretation: a journal of political philosophy. Winter 1973. Vol.: 3. No.: 2-3. Pages: 114-156. Includes the complete text of the last two lectures of the academic year 1933-1934, published in French text as an appendix named L'idée de la mort dans la philosophie de Hegel (pp. 527–573). Alexandre Kojève (transl. Ian Alexander Moore), Interpretation of the general introduction to chapter VII [The religion chapter of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit]. Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy. 2014. No.: 20. Pages: 15-39. Online. Includes the fourth and fifth lectures of the academic year 1937-1938. Alexandre Kojève, Essai d'une histoire raisonée de la philosophie païenne. Tome 1–3 (Vol.: 1 [1968], Vol.: 2 [1972], Vol.: 3 [1973]). Gallimard. Paris. 1968-1973 [1997]. Alexandre Kojève, Kant. Gallimard. 1st Ed., 1973. Paris. Alexandre Kojève (transl. Hager Weslati), Kant. Verso. 1st Ed., 2025. [to be published] Alexandre Kojève, Esquisse d'une phénoménologie du Droit [1943]. Gallimard. Paris. 1982. Alexandre Kojève (ed. Bryan-Paul Frost, transl. Bryan-Paul Frost and Robert Howse), Outline of a Phenomenology of Right, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2000. Alexandre Kojève and Auffret D., L'idée du determinisme dans la physique classique et dans la physique moderne. Paris, 1990. Alexandre Kojève (transl. Robert B. Williamson), The Idea of Determinism. St. Augustine's Press, South Bend IN, 2025 [to be published]. Alexandre Kojève, Le concept, le temps et le discours. Paris, 1991. Alexandre Kojève (transl. Robert B. Williamson), The Concept, Time and Discourse. St. Augustine's Press, South Bend IN, 2013. Alexandre Kojève, L'empereur Julien et son art d'écrire. Paris, 1997. Alexandre Kojève (transl. Nina Ivanoff and Laurent Bibard, ed. Laurent Bibard), L'athéisme. Gallimard. 1st Ed., 1998. Paris. Александр Кожев (Пер. с фр. А.М. Руткевича), Атеизм и другие работы. Праксис. 1st Ed., 2006. Moscow. Includes the original Russian text and his several other writings (translated by A. M. Rutkevich): Descartes and Buddha (1920), The Religious Metaphysics of Vladimir Solovyov (1934-1935) Kandinsky's Concrete (Objective) Painting (1936), An Essay on the Phenomenology of Law: Chapter 1 (1943), Tyranny and Wisdom (1954), Colonialism from a European Point of View (1957), Moscow, August 1957 (1957) and The Christian Origin of Science (1964) Alexandre Kojève, Les peintures concrètes de Kandinsky [1936]. La Lettre volée. 1st Ed., 2002. Paris. Alexandre Kojève, La notion d'autorité [1942]. Gallimard. 1st Ed., 2004. Paris. Alexandre Kojève (transl. Hager Weslati), The Notion of Authority. Verso. 1st Ed., 2014. London-New York. Alexandre Kojève, Identité et Réalité dans le «Dictionnaire» de Pierre Bayle [1936-1937]. Gallimard. 1st Ed., 2010. Paris. Alexandre Kojève, Oltre la fenomenologia. Recensioni (1932-1937), Italian Translation by Giampiero Chivilò, «I volti», n. 68, Mimesis, Udine-Milano, 2012. ISBN 978-88-5750-877-1. Alexandre Kojève, Sophia, tome I : Philosophie et phénoménologie [1940-1941]. Gallimard. 2025. [to be published] Articles, chapters, speeches Alexandre Kojève, Die Geschichtsphilosophie Wladimir Solowjews. Der Russische Gedanke. 1930. Jahrg.: I. Heft: 3. Pages: 305-324. A short article based on the dissertation. Alexandre Kojevnikoff, La métaphysique religieuse de Vladimir Soloviev. Revue d'Histoire et de Philosophie religieuses. Novembre-décembre 1934. Année: 14. № 6. (Online) Alexandre Kojevnikoff, La métaphysique religieuse de Vladimir Soloviev (suite et fin). Revue d'Histoire et de Philosophie religieuses. Janvier-avril 1935. Année: 15. № 1-2. (Online) Famous two parts article based on the dissertation. Alexandre Kojève (transll. Ilya Merlin, Mikhail Pozdniakov), The Religious Metaphysics of Vladimir Solovyov. Palgrave Macmillan. 1st Ed., 2018. ISBN 978-3-030-02338-6. Translated from the French edition. Alexandre Kojève, L'origine chrétienne de la science moderne [1961]. in: Mélanges Alexandre Koyré: publiés à l'occasion de son soixante-dixième anniversaire (Tome II - « L'aventure de l'esprit »). Hermann. 1st Ed., 1964. Paris. Alexandre Kojève, The Christian Origin of Modern Science. The St. John's Review. Winter 1984. Pages: 22-26. (Online) Alexandre Kojève, The Emperor Julian and His Art of Writing. in: Joseph Cropsey, Ancients and Moderns: Essays on the Tradition of Political Philosophy in Honor of Leo Strauss. Basic Books. 1st Ed., 1964. Pages: 95-113. New York. Alexandre Kojève, Tyranny and Wisdom. in: Leo Strauss, On Tyranny - Revised and Expanded Edition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 135-176, 2000. Alexandre Kojève, Esquisse d'une doctrine de la politique française (27.8.1945). La règle du jeu. Mai 1990. 1re année. № 1. Alexandre Kojève (transl. Erik De Vries), Outline of a Doctrine of French Policy. Policy Review. August-September 2004. Pages: 3-40. (Online) German language lecture given in Düsseldorf on January 16, 1957. It wasn't published during the lifetime of Kojève, although a French translation was circulated. According to De Vries (see below, p. 94) some parts of it were omitted in French. Alexandre Kojève, Capitalisme et socialisme : Marx est Dieu, Ford est son prophète. Commentaire. Printemps 1980. Vol.: 3. № 9 (1980/1). Pages: 135-137. Alexandre Kojève, Du colonialisme au capitalisme donnant. Commentaire. Automne 1999. Vol.: 21. № 87 (1999/3). Pages: 557-565. Alexandre Kojève, Le colonialisme dans une perspective européenne. Philosophie. Septembre 2017. № 135 (2017/4). Pages: 28-40. Publication of the French text with the added passages from German. Alexandre Kojève, Düsseldorfer Vortrag: Kolonialismus in europäischer Sicht. In: Piet Tommissen (Hg.): Schmittiana. Beiträge zu Leben und Werk Carl Schmitts. Band 6, Berlin 1998, pp. 126–143. Alexandre Kojève (transl. and comment. Erik De Vries), Alexandre Kojève — Carl Schmitt Correspondence and Alexandre Kojève, "Colonialism from a European Perspective". Interpretation. Fall 2001. Vol.: 29. No.: 1. Pages: 91–130 [given speech in pp. 115-128]. |

書誌 書籍 Alexander Koschewnikoff, Die religiöse Philosophie Wladimir Solowjews. ハイデルベルク大学、学位論文1926年。(オンライン) Alexander Koschewnikoff, Die Geschichtsphilosophie Wladimir Solowjews (Sonderabdruck). Verlag von Friedrich Cohen. 1st Ed., 1930. ボン。 彼が執筆した論文のオフプリントである(下段参照)。 Alexandre Kojève, Introduction à la Lecture de Hegel. パリ、ガリマール、1947年。 アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ(アラン・ブルーム編、ジェイムズ・H・ニコルス・ジュニア訳)『ヘーゲル読解入門』: 精神現象学講義. Basic Books, Inc. 1st Ed., 1969. New York-London. / コーネル大学出版局。1980. イサカ。 アラン・ブルームの編集による抄訳で、原著の約半分である。訳者の注によれば、「本訳は原著の半分弱を含んでいる。」訳されたパサージュは仏文の9-34 頁、161-195頁、265-267頁、271-291頁、336-380頁、427-443頁、447-528頁、576-597頁に相当する。 (p. XIII) アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ(ジョゼフ・J・カルピノ訳)『ヘーゲル哲学における死の思想』(岩波書店)。Interpretation: a journal of political philosophy. 1973年冬号。第3巻、第2-3号。ページ: 114-156. ヘーゲルの哲学における死生観(527-573頁)という付録として仏文で出版された1933-1934年度の最後の2つの講義の全文を含む。 アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ(イアン・アレクサンダー・ムーア訳)、第VII章[ヘーゲルの精神現象学の宗教の章]一般序説の解釈。Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy. 2014. 第20号。ページ: 15-39. オンライン。 1937-1938年度の第4回と第5回の講義を含む。 Alexandre Kojève, Essai d'une histoire raisonée de la philosophie païenne. Tome 1-3 (Vol.: 1 [1968], Vol.: 2 [1972], Vol.: 3 [1973]). Gallimard. パリ。1968-1973 [1997]. アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ『カント』。ガリマール. 1973年初版。パリ。 アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ(ヘーガー・ウェスラティ訳)『カント』. Verso. 初版, 2025. [出版予定] Alexandre Kojève, Esquisse d'une phénoménologie du Droit [1943]. Gallimard. Paris. 1982. Alexandre Kojève (ed. Bryan-Paul Frost, transl. Bryan-Paul Frost and Robert Howse), Outline of a Phenomenology of Right, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2000. Alexandre Kojève and Auffret D., L'idée du determinisme dans la physique classique et dans la physique modernne. Paris, 1990. アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ(ロバート・B・ウィリアムソン訳)『決定論の思想』。St. Augustine's Press, South Bend IN, 2025[出版予定]。 Alexandre Kojève, Le concept, le temps et le discours. パリ、1991年 アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ(ロバート・B・ウィリアムソン訳)『概念・時間・言説』。St. Augustine's Press, South Bend IN, 2013. Alexandre Kojève, L'empereur Julien et son art d'écrire. Paris, 1997. Alexandre Kojève (Nina Ivanoff and Laurent Bibard, ed. Laurent Bibard), L'athéisme. Gallimard. 1st Ed., 1998. パリ。 Александр Кожев (Пер. с фр. А.М. Руткевича), Атеизм и другие работы. Праксис. 1st Ed., 2006. モスクワ。 ロシア語原文と彼の他の著作(A. M. Rutkevich訳)を含む: デカルトとブッダ』(1920年)、『ウラジーミル・ソロヴィヨフの宗教形而上学』(1934-1935年)、『カンディンスキーの具体的(客観的)絵 画』(1936年)、『法の現象学に関する試論』(1943年)、『法の現象学に関する試論』(1943年): 第1章』(1943年)、『専制と知恵』(1954年)、『ヨーロッパから見た植民地主義』(1957年)、『モスクワ、1957年8月』(1957 年)、『科学のキリスト教的起源』(1964年) Alexandre Kojève, Les peintures concrètes de Kandinsky [1936]. La Lettre volée. 1st Ed., 2002. Paris. Alexandre Kojève, La notion d'autorité [1942]. Gallimard. 第1版、2004年。パリ。 アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ(ヘーガー・ウェスラティ訳)『権威の概念』。Verso. 1st Ed., 2014. ロンドン-ニューヨーク。 Alexandre Kojève, Identité et Réalité dan le 「Dictionnaire」 de Pierre Bayle [1936-1937]. Gallimard. 1st Ed., 2010. Paris. Alexandre Kojève, Oltre la fenomenologia. Recensioni (1932-1937), Italian Translation by Giampiero Chivilò, 「I volti」, n. 68, Mimesis, Udine-Milano, 2012. ISBN 978-88-5750-877-1。 Alexandre Kojève, Sophia, tome I : Philosophie et phénoménologie [1940-1941]. Gallimard. 2025. [出版予定] 論文、章、講演 Alexandre Kojève, Die Geschichtsphilosophie Wladimir Solowjews. Der Russische Gedanke. 1930. Jahrg: Heft: 3. ページ: 305-324. 論文に基づく小論。 Alexandre Kojevnikoff, La métaphysique religieuse de Vladimir Soloviev. Revue d'Histoire et de Philosophie religieuses. Revue d'Histire et de Philosophie religieuses. オンライン)。 Alexandre Kojevnikoff, La métaphysique religieuse de Vladimir Soloviev (suite et fin). Revue d'Histoire et de Philosophie religieuses. Janvier-avril 1935. 年:15。(オンライン) 学位論文に基づく2部構成の有名な論文。 Alexandre Kojève (transll. Ilya Merlin, Mikhail Pozdniakov), The Religious Metaphysics of Vladimir Solovyov. Palgrave Macmillan. 1st Ed., 2018. ISBN 978-3-030-02338-6. フランス語版からの翻訳。 Alexandre Kojève, L'origine chrétienne de la science modernne [1961]: Mélanges Alexandre Koyré: publiés à l'occasion de son soixante-dixième anniversaire (Tome II - 「 L'aventure de l'esprit 」). Hermann. 1964年初版。パリ。 Alexandre Kojève, The Christian Origin of Modern Science. The St. 1984年冬。ページ: 22-26. (オンライン) アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ『ユリアヌス帝とその筆記術』: Joseph Cropsey, Ancients and Moderns: Joseph Cropsey, Ancients and Moderns: Essays on the Tradition of Political Philosophy in Honoror of Leo Strauss. Basic Books. 1st Ed., 1964. ページ: 95-113. ニューヨーク。 Alexandre Kojève, Tyranny and Wisdom: Leo Strauss, On Tyranny - Revised and Expanded Edition, Chicago: シカゴ大学出版局, p. 135-176, 2000. Alexandre Kojève, Esquisse d'une doctrine de la politique française (27.8.1945). La règle du jeu. 1990年5月。1re année. № 1. アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ(訳:エリック・デ・ヴリース)『フランス政策学説概説』。Policy Review. 2004年8月-9月。ページ: 3-40. (オンライン) 1957年1月16日にデュッセルドルフで行われたドイツ語講演。コジェーヴ存命中には出版されなかったが、フランス語訳が出回った。デ・フリースによれ ば(後述、p.94)、フランス語では一部が省略されている。 Alexandre Kojève, Capitalisme et socialisme : Marx est Dieu, Ford est son prophète. コメント。Printemps 1980. 巻: 3. № 9 (1980/1). ページ: 135-137. Alexandre Kojève, Du colonialisme au capitalisme donnant. コメント。1999年秋。Vol. 21. № 87 (1999/3). ページ: 557-565. Alexandre Kojève, Le colonialisme dans une perspective européenne. Philosophie. Septembre 2017. № 135 (2017/4). ページ: 28-40. フランス語のテキストにドイツ語の文章を追加した出版物。 Alexandre Kojève, Düsseldorfer Vortrag: Kolonialismus in europäischer Sicht. で: Piet Tommissen (Hg.): Schmittiana. Beiträge z Leben und Werk Carl Schmitts. Band 6, Berlin 1998, pp.126-143. Alexandre Kojève (transl. and comment. Erik De Vries), Alexandre Kojève - Carl Schmitt Correspondence and Alexandre Kojève, 「Colonialism from a European Perspective」. Interpretation. 2001年秋号。第 29 巻第 1 号: 91-130 [115-128頁で講演]. |

| Jean Wahl Post-Kojèvian discourse Jean Hyppolite Bernard Bourgeois |

ジャン・ウォール ポスト・コジェーヴ的言説 ジャン・ヒポリット ベルナール・ブルジョワ |

| Sources Butler, Judith (1987), Subjects of Desire: Hegelian Reflections in Twentieth-Century France, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-06450-0 Lilla, Mark (2001), "Alexandre Kojève", The Reckless Mind. Intellectuals in Politics, New York: New York Review Books, ISBN 0-940322-76-5 Further reading Bibard, Laurent, la Sagesse et le Féminin, L'Harmattan, 2005 Agamben, Giorgio (2004), The Open: Man and Animal, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-4737-7 Anderson, Perry (1992), "The Ends of History", A Zone of Engagement, New York: Verso, pp. 279–375, ISBN 0-86091-377-5 Auffret, D. (2002), Alexandre Kojeve. La philosophie, l'Etat, la fin de l'histoire, Paris: B. Grasset, ISBN 2-246-39871-1 Chivilò, Giampiero; Menon, Marco (eds.) (2015), Tirannide e filosofia: Con un saggio di Leo Strauss ed un inedito di Gaston Fessard sj, Venezia: Edizioni Ca' Foscari, pp. 335–416, ISBN 978-88-6969-032-7 Cooper, Barry (1984), The End of History: An Essay on Modern Hegelianism, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-8020-5625-3 Darby, Tom (1982), The Feast: Meditations on Politics and Time, Toronto: Toronto University Press, ISBN 0-8020-5578-8 Devlin, F. Roger (2004), Alexandre Kojeve and the Outcome of Modern Thought, Lanham: University Press of America, ISBN 0-7618-2959-8 Drury, Shadia B. (1994), Alexandre Kojeve: The Roots of Postmodern Politics, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-12089-3 Filoni, Marco (2008), Il filosofo della domenica: La vita e il pensiero di Alexandre Kojève, Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, ISBN 978-88-339-1855-6 Filoni, Marco (2013), Kojève mon ami, Turin: Nino Aragno Fukuyama, Francis (1992), The End of History and the Last Man, New York: Macmillan, ISBN 0-02-910975-2 Geroulanos, Stefanos (2010), An Atheism That Is Not Humanist Emerges in French Thought, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-6299-1 Kleinberg, Ethan (2005), Generation Existential: Heidegger's Philosophy in France, 1927-1961, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, ISBN 0-8014-4391-1 Kovacevic, Filip (2014), Kožev u Podgorici: Ciklus predavanja o Aleksandru Koževu, Podgorica, Montenegro: Centar za građansko obrazovanje, ISBN 978-86-85591-29-7 Nichols, James H. (2007), Alexandre Kojeve: Wisdom at the End of History, Lanham MA: Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0742527775 Niethammer, Lutz (1992), Posthistoire: Has History Come to an End?, New York: Verso, ISBN 0-86091-395-3 Rosen, Stanley (1987), Hermeneutics as Politics, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 87–140, ISBN 0-19-504908-X Rosen, Stanley (1999), "Kojève", A Companion to Continental Philosophy, London: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-21850-0 Rossman, Vadim (2006-01-18), Alexandre Kojeve i jego trzy wieloryby, Poland: Europa, pp. 7–12 Roth, Michael S. (1988), Knowing and History: Appropriations of Hegel in Twentieth-Century France, Ithaca: Cornell, ISBN 0-8014-2136-5 Singh, Aakash (2005), Eros Turannos: Leo Strauss & Alexandre Kojeve Debate on Tyranny, Lanham: University Press of America, ISBN 0-7618-3259-9 Strauss, Leo (2000), On Tyranny (Rev. and expanded ed.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-77687-5 Tremblay, Frédéric (2020), "Alexandre Kojève, The Religious Metaphysics of Vladimir Solovyov, transl. by I. Merlin and M. Pozdniakov, Palgrave Pivot, 2018", Sophia: International Journal of Philosophy and Traditions, vol. 51, pp. 181–183 Vidali, Cristiano (2020), Fine senza compimento. La fine della storia in Alexandre Kojève tra accelerazione e tradizione. (Preface by Massimo Cacciari), Milano-Udine: Mimesis, ISBN 978-8857565606 Violence and Conflict in Alexandre Kojève’s Works, Philosophical Journal of Conflict and Violence, Volume 8, Issue 1. 2024. ISSN 2559-9798 |

情報源 Butler, Judith (1987), Subjects of Desire: Hegelian Reflections in Twentieth-Century France, New York: コロンビア大学出版局、ISBN 0-231-06450-0 Lilla, Mark (2001), 「Alexandre Kojève」, The Reckless Mind. Intellectuals in Politics, New York: New York Review Books, ISBN 0-940322-76-5 さらに読む Bibard, Laurent, la Sagesse et le Féminin, L'Harmattan, 2005. Agamben, Giorgio (2004), The Open: 人間と動物, Stanford: スタンフォード大学出版局, ISBN 0-8047-4737-7 Anderson, Perry (1992), 「The Ends of History」, A Zone of Engagement, New York: Verso, pp.279-375, ISBN 0-86091-377-5 Auffret, D. (2002), Alexandre Kojeve. La philosophie, l'Etat, la fin de l'histoire, Paris: B. Grasset, ISBN 2-246-39871-1 Chivilò, Giampiero; Menon, Marco (eds.) (2015), Tirannide e filosofia: Con un saggio di Leo Strauss ed un inedito di Gaston Fessard sj, Venezia: Edizioni Ca' Foscari, pp.335-416, ISBN 978-88-6969-032-7. Cooper, Barry (1984), The End of History: An Essay on Modern Hegelianism, Toronto: トロント大学出版局, ISBN 0-8020-5625-3 Darby, Tom (1982), The Feast: Meditations on Politics and Time, Toronto: トロント大学出版局, ISBN 0-8020-5578-8 Devlin, F. Roger (2004), Alexandre Kojeve and the Outcome of Modern Thought, Lanham: University Press of America, ISBN 0-7618-2959-8 Drury, Shadia B. (1994), Alexandre Kojeve: The Roots of Postmodern Politics, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-12089-3 Filoni, Marco (2008), Il filosofo della domenica: La vita e il pensiero di Alexandre Kojève, Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, ISBN 978-88-339-1855-6. Filoni, Marco (2013), Kojève mon ami, Turin: Nino Aragno. Fukuyama, Francis (1992), The End of History and the Last Man, New York: マクミラン, ISBN 0-02-910975-2 Geroulanos, Stefanos (2010), An Atheism That Is Not Humanist Emerges in French Thought, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-6299-1 Kleinberg, Ethan (2005), Generation Existential: Heidegger's Philosophy in France, 1927-1961, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, ISBN 0-8014-4391-1 Kovacevic, Filip (2014), Kožev u Podgorici: Ciklus predavanja o Aleksandru Koževu, Podgorica, Montenegro: Centar za građansko obrazovanje, ISBN 978-86-85591-29-7 Nichols, James H. (2007), Alexandre Kojeve: Wisdom at the End of History, Lanham MA: Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0742527775 Niethammer, Lutz (1992), Posthistoire: Has History Come to an End? Verso, ISBN 0-86091-395-3 Rosen, Stanley (1987), Hermeneutics as Politics, New York: オックスフォード大学出版局、87-140頁、ISBN 0-19-504908-X Rosen, Stanley (1999), 「Kojève」, A Companion to Continental Philosophy, London: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-21850-0 Rossman, Vadim (2006-01-18), Alexandre Kojeve i jego trzy wieloryby, Poland: Europa, pp. Roth, Michael S. (1988), Knowing and History: 20世紀フランスにおけるヘーゲルの適用, Ithaca: Cornell, ISBN 0-8014-2136-5. Singh, Aakash (2005), Eros Turannos: Leo Strauss & Alexandre Kojeve Debate on Tyranny, Lanham: University Press of America, ISBN 0-7618-3259-9 Strauss, Leo (2000), On Tyranny (Rev. and expanded ed.), Chicago: シカゴ大学出版局, ISBN 0-226-77687-5 Tremblay, Frédéric (2020), 「Alexandre Kojève, The Religious Metaphysics of Vladimir Solovyov, transl. I. Merlin and M. Pozdniakov, Palgrave Pivot, 2018」, Sophia: International Journal of Philosophy and Traditions』51巻、181-183頁。 Vidali, Cristiano (2020), Fine senza compimento. La fine da storia in Alexandre Kojève tra accelerazione e tradizione. (Preface by Massimo Cacciari), Milanoo-Udine: Mimesis, ISBN 978-8857565606 アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ作品における暴力と紛争、『紛争と暴力の哲学雑誌』、第8巻、第1号。2024. ISSN 2559-9798 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandre_Koj%C3%A8ve |

★