On

reading Alexandre Kojeve's "Introduction to read Hegel"

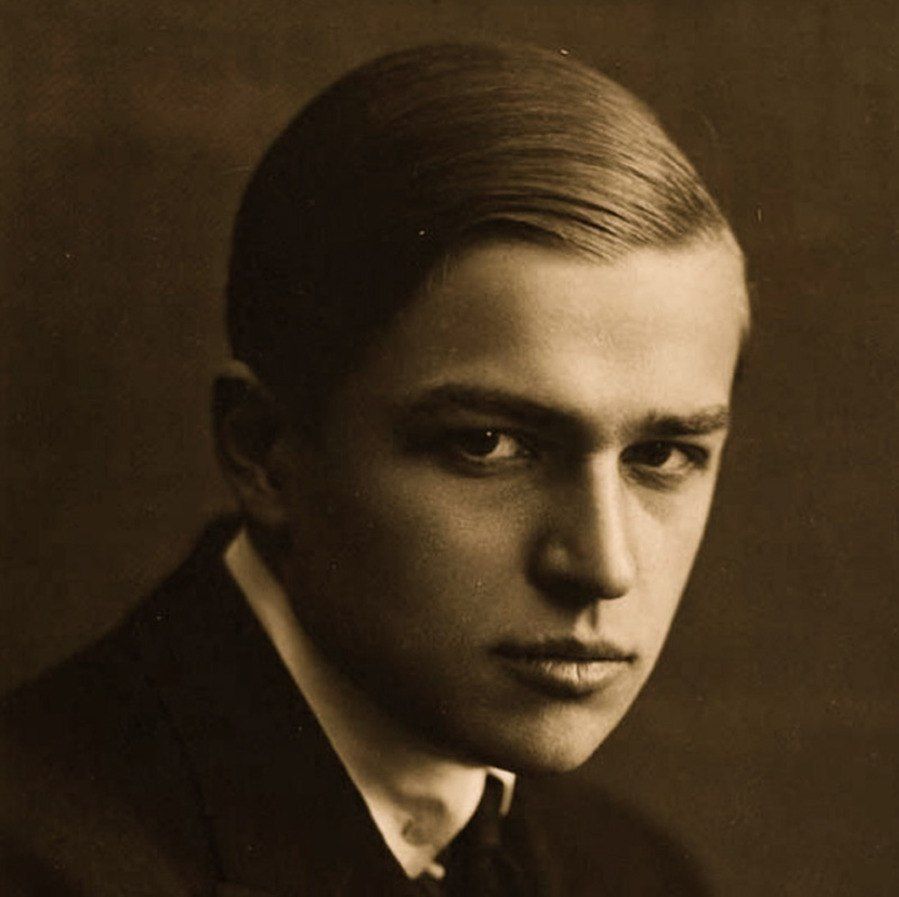

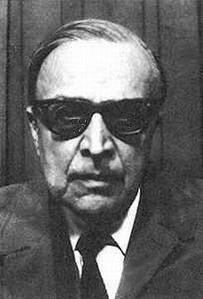

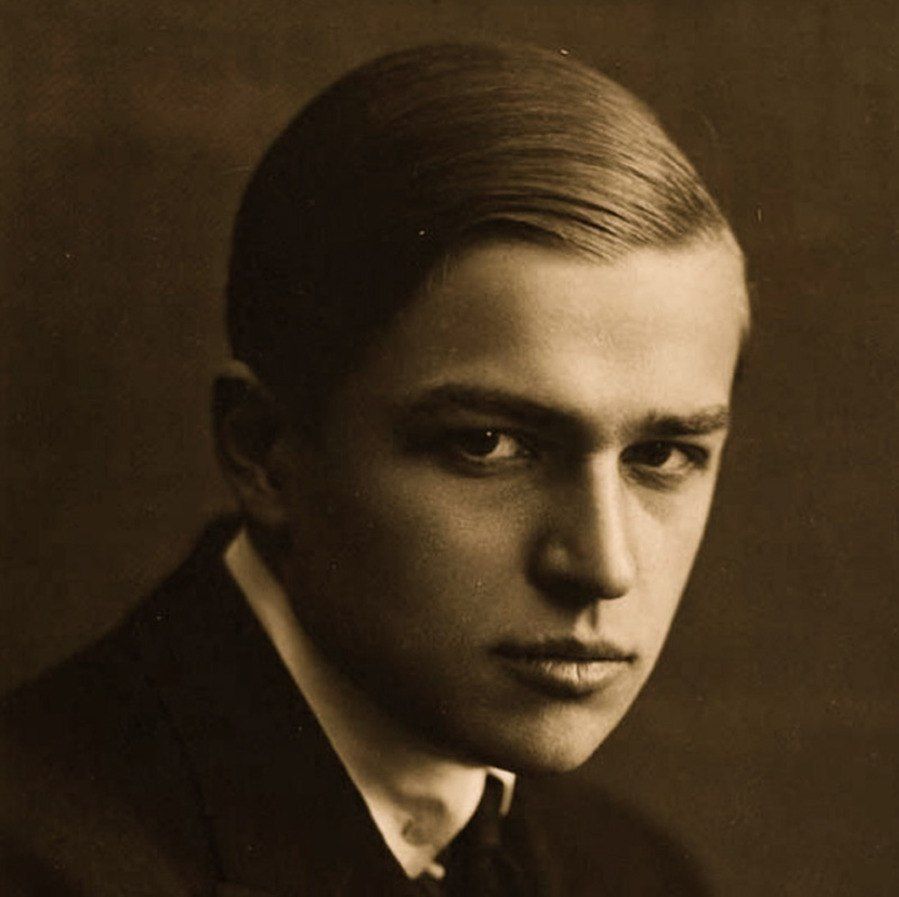

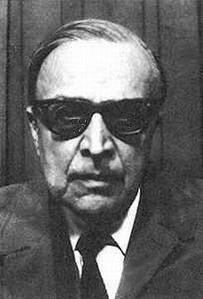

Kojève in Berlin, 1922 / Kojève, n.d.

On

reading Alexandre Kojeve's "Introduction to read Hegel"

Kojève in Berlin, 1922 / Kojève, n.d.

アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ『ヘーゲル読解入門』を読むのページ。アレクサンドル・コジェーヴについてはリンク先を参照してください。

このテキストは、上妻と今野の日本抄訳版 (1987)全9章プラス付録に準拠している。

ヘーゲル精神現象学(→「G.W.F.ヘーゲル」Georg

Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, 1770-1831, Phänomenologie des Geistes,

1807.)(→「ヘーゲル『精神現象学』1807ノート」)

| アレクサンドル・コジェーヴ | ヘーゲルを人間的な行為者中心に理解しようと試みる。ヘーゲルはある意味で個人主義者。 |

| ジョルジュ・バタイユ |

人間をほとんど必要のないものにする。脱人間性、蕩尽を通して欲望から解放される否定性を主張 |

| ジャン=ポール・サルトル |

『存在と無』では反個人主義者。ひとつの自己意識が他の自己意識とむきあう。しかし、その個人間の闘争はうやむやにされて、最後は自己意識の確立へと回収される。 |

章立て

++++++++++++

★Introduction to

the reading of Hegel : lectures on the Phenomenology of spirit /

by Alexandre Kojève ; assembled by Raymond Queneau ; edited by Allan

Bloom ; translated from the French by James H. Nichols, Jr, Bloom ;

translated from the French by James H. Nichols, Jr [pdf]

++++++++++++

★

| G.W.F. Hegel, Phänomenologie des Geistes, (1807) |

||

| Vorrede Einleitung I. Die sinnliche Gewißheit; oder das Diese und das Meinen II. Die Wahrnehmung; oder das Ding, und die Täuschung III. Kraft und Verstand, Erscheinung und übersinnliche Welt IV. Die Wahrheit der Gewißheit seiner selbst A. Selbstständigkeit und Unselbstständigkeit des Selbstbewußtseins; Herrschaft und Knechtschaft

V. Gewißheit und Wahrheit der VernunftB. Freiheit des Selbstbewußtseins; Stoizismus, Skeptizismus und das unglückliche Bewußtsein A. Beobachtende Vernunft a. Beobachtung der Natur b. Die Beobachtung des Selbstbewußtseins in seiner Reinheit und seiner Beziehung auf äußre Wirklichkeit; logische und psychologische Gesetze c. Beobachtung der Beziehung des Selbstbewußtseins auf seine unmittelbare Wirklichkeit; Physiognomik und Schädellehre B. Die Verwirklichung des vernünftigen Selbstbewußtseins durch sich selbst a. Die Lust und die Notwendigkeit b. Das Gesetz des Herzens und der Wahnsinn des Eigendünkels c. Die Tugend und der Weltlauf C. Die Individualität, welche sich an und für sich selbst reell ist a. Das geistige Tierreich und der Betrug, oder die Sache selbst b. Die gesetzgebende Vernunft c. Gesetzprüfende Vernunft VI. Der Geist A. Der wahre Geist, die Sittlichkeit a. Die sittliche Welt, das menschliche und göttliche Gesetz, der Mann und das Weib b. Die sittliche Handlung, das menschliche und göttliche Wissen, die Schuld und das Schicksal c. Rechtszustand B. Der sich entfremdete Geist; die Bildung I. Die Welt des sich entfremdeten Geistes a. Die Bildung und ihr Reich der Wirklichkeit b. Der Glauben und die reine Einsicht II. Die Aufklärung a. Der Kampf der Aufklärung mit dem Aberglauben b. Die Wahrheit der Aufklärung III. Die absolute Freiheit und der Schrecken C. Der seiner selbst gewisse Geist. Die Moralität a. Die moralische Weltanschauung b. Die Verstellung c. Das Gewissen, die schöne Seele, das Böse und seine Verzeihung VII. Die Religion A. Natürliche Religion a. Das Lichtwesen b. Die Pflanze und das Tier c. Der Werkmeister B. Die Kunst-Religion a. Das abstrakte Kunstwerk b. Das lebendige Kunstwerk c. Das geistige Kunstwerk C. Die offenbare Religion VIII. Das absolute Wissen |

The Preface Introduction Consciousness I. Sense-Certainty, This, & Meaning II. Perception, Thing, & Deceptiveness III. Force & Understanding Self-Consciousness IV. True Nature of Self-Certainty

A. Lordship & Bondage

(AA) ReasonB. Unhappy Consciousness V. Certainty & Truth of Reason A. Observation as Reason B. Realization of rational self-consciousness C. Individuality (BB). Spirit VI. Spirit A. Objective Spirit: the Ethical order B. Culture & civilization I. World of spirit in self-estrangement II. Enlightenment III. Absolute Freedom & Terror C. Morality a. The Moral View of the World b. Dissemblance c. Conscience: The “Beautiful Soul”:Evil and the Forgiveness of it (CC). Religion VII. Religion in General A. Natural Religion B. Religion as Art C. Revealed Religion (DD). Absolute Knowledge VIII.Absolute Knowledge |

序文 はじめに 意識 I. 感覚-確かさ、これ、そして意味 II. 知覚、物事、そして欺瞞性 III. 力と理解 自己意識 IV. 自己確信の本質 A. 支配と束縛 B. 不幸な意識 (AA) 理性 V. 理性の確実性と真理 A. 理性としての観察 B. 理性的自己意識の実現 C. 個性 (BB)精神 VI. スピリット(精神) A. 客観的精神:倫理的秩序 B. 文化と文明 I. 自己分離した精神の世界 II. 啓蒙 III. 絶対的自由と恐怖 C. 道徳 a. 世界の道徳観 b. 普及 c. 良心 美しい魂」:悪とその赦し (CC)。宗教 VII. 宗教一般 A. 自然宗教 B. 芸術としての宗教 C. 啓示された宗教 (DD)絶対的知識 VIII.絶対的知識 |

| https://www.marxists.org/deutsch/philosophie/hegel/phaenom/ |

★

| 序文 はじめに 意識 I. 感覚-確かさ、これ、そして意味 II. 知覚、物事、そして欺瞞性 III. 力と理解 自己意識 IV. 自己確信の本質 A. 支配と束縛 B. 不幸な意識 (AA) 理性 V. 理性の確実性と真理 A. 理性としての観察 B. 理性的自己意識の実現 C. 個性 (BB)。精神 VI. スピリット A. 客観的精神:倫理的秩序 B. 文化と文明 I. 自己分離した精神の世界 II. 啓蒙 III. 絶対的自由と恐怖 C. 道徳 a. 世界の道徳観 b. 普及 c. 良心 美しい魂」:悪とその赦し (CC)。宗教 VII. 宗教一般 A. 自然宗教 B. 芸術としての宗教 C. 啓示された宗教 (DD)。絶対的知識 VIII.絶対的知識 |

|

| 池田光穂の■読書メモ 承前 9 ノートの来歴 11 自己意識、自己感情、19 12 欲望 31 承認、主と奴(主人と奴隷) 32 自立的意識の真理は奴の意識である 32 歴史とは労働する奴の歴史である 33 奴は当初から他者(主)を承認していた 34 奴は自由を知っている 35 労働が奴を自然から解放するとき…… 38 動物から発して人間を形成=教化するのは労働である 42 主人は世界に隷属する |

|

| 第2章 49 デカルトの哲学が不十分であるのは…… 51 自己意識 52 そして、欲望 53 闘争と労働(行動) 54 動物と動物的欲望 56 闘争、歴史、主と奴 57 奴の労働の意味 58 主と奴の間の闘争、歴史の誕生 59 主と奴の本質 61 闘争の果てに彼(主人)は、奴に承認されているにすぎない 62 主であることは現存在の袋小路である 63 人間は恐れたために奴となった 68 生命を危険にさらすこと 69 奴のイデオロギーの最初のものがストア主義 70 人間は存在を否定することにより無化する無である 71 独我論 72 キリスト教、74 75 非キリスト教的社会 76 主と奴の対立が廃棄される 77 国家 80 非キリスト教的世界は労働を排除するために滅亡する 81 キリスト教的人間の誕生 81 ブルジョア、84 82 私的権利 86 死すべき人間の意味 88 ナポレオンの帝国 89 イエス・キリスト 90 観念、悟性、労働 |

|

| 第3章 91 宗教、92 93 精神 94 本質的実在、客観的精神 95 神 96 国家と個人 98 民族=フォルクの絶対精神、ヘーゲルからの引用 99 人倫の体系からの引用、民族の神(Goertlichkeit des Volks) 100 ニュートン物理学 102 キリスト教徒の心理 103 彼岸、人格神 104 知識人、芸術家 108 自己自身を知る精神 109 宗教と自己意識 111 プロテスタンティズムと無神論の親和性 112 人間は自己に至高の価値を帰属せしめる 114 有神論と革命 116 神学のかたちで人間学をつくる人間 |

|

| 第4章 |

|

| 第5章 134 賢者、139、141 138 完全であるためには 145 知恵の理想 146 哲学者、哲学者と賢者 148 151 現存在の態度には3つの類型が可能であり…… 152 失敗するヘーゲル 153 なぜヘーゲルは『精神現象学』を書いたか? 158 誤謬にあらず、真理にあらざるもの、それは観念 160 賢者、スピノザ |

|

| 第6章 163 真理 世界内人間 164 観念、概念、時間 165 概念は永遠 167 イデア 169 永遠性は時間の外にある(プラトン)、永遠性は時間の中にある(アリストテレス) 171 犬という語は、犬の本質を開示する(→狗類学) 176 プラトンは徳を教えることが可能であると信じる 178 アリストテレスは永遠を時間の内にみる 178 (プラトンの永遠を時間の外にみるという)永遠性が犬のイデアである 182 スピノザの体系は、非合理な完全な体系である、192 184 スピノザの体系は、絶対知の観念である 194 超越論自我(カント)は、スピノザの神に相当する 198 パルメニデス、時間の講釈 199 ヘーゲルにおける概念と時間 201 経験的に——現存在する——概念 202 未来によって生み出される運動 203 他者の欲望に向かう欲望 205 世界における時間の実在的現前が人間と呼ばれる。時間は世界—内—人間 205 精神は時間(イエナ講義) 206 時間は経験的に現存在する概念そのものだ 207 ロゴス、222 210 労働、概念が労働でり、労働は概念だ 211 労働は人間本質そのもの 211 生命の否定 213 概念と時間の同一化の重要性 214 世界史 216 言説による思惟 218 時間が穴 219 アリストテレスにおける「犬」、実在する犬 220 定立 221 存在、概念、時間 |

|

| 第8章 250 真なるものと概念 250 存在と思惟 251 フッサール的意味での現象学 254 真理において、概念と対象との完全な一致がある 258 ヘーゲルの方法は、弁証法的ではない 263 神的対話者は実は虚構 264 自分(ヘーゲル)は、プラトンの弁証法を再発見したにすぎない 268 人間だけが誤謬を犯す 269-270 労働という誤謬 270 真理は必然的に弁証法的である 271 暗殺者、闘争 272 哲学的方法としての弁証法 274 闘争、労働、行動 275 思惟のすべて 276 全歴史 276 ヘーゲルの方法は現象学的 278 悟性の思惟と同一性 280 真理と存在、そして理性 288 実在する弁証法 292 弁証法的揚棄 293 自由=行動=否定性 296 ヘーゲルの精神 300 自然の弁証法はよくわからない 301 骨相学 302 即自、対自存在 303 動物と自由、否定性 305 否定を通して自由になる人間 306 否定と創造 307 主と奴、承認、闘争 308 主と奴 311 否定性の実現、労働は自己を否定する活動 312 労働する奴が創造する理由 313 奴と主、そして消費 314 奴の労働 315 闘争と労働 317 創造的行動 319 総合の意味、総体性(325) 320 社会と人間 324 同一性、動物性など 327 愛の分析断片 328 公民と賢者、主と奴 329 死の本源的役割、愛する者の死 330 人間の死の意味 332 否定する絶対者 333 死は自由の補完的な一側面 336 死、ロマン主義、歴史、国家 337 歴史における人間の死 338 存在の否定性 339 人間の否定性と死 340 自己の死の意識 343 歴史を仕上げる人間 344 ヘーゲルの弁証法 344 注釈、量子力学の講釈!(ヘーゲルではなくコジェーヴ) 345 ロゴス、実在するもの 346 存在と思惟は同一である(パルメニデス) 347 『エンチクロペディー』関連の、どんぐりや樫(柏?と記載) 348 否定性の注釈、総体など 349 人間と自然の関係 350-351 二元論的存在、二元的存在論 352 存在と無 353 観念は欲望から生まれる 353 技術 355-356 愛と存在、危険 356 ドストエフスキー『悪霊』キリーロフの自殺 358 イエスの個体性 |

|

| 第9章 361 真なるもの、主体 364 真なるものは全体 367 絶対者は精神 368 自由とコスモス、イデア、本質 369 ヘーゲルにとって人間とは?、人間=死すべきもの(372) 373 精神とは世界—内—人間である 374 人間は自己の死を意識する 375 分離 376 直接態、知恵、賢者 378 概念がつくられるとき、今ここから引き離される 378 プラトンのイデア、アリストテレスのエンテレケイア 380 存在 381 存在と悟性 383 奇跡 383 自然的世界と人間 384 否定なるもの(das Nagative) 385 精神の生 386 精神が再度、自己を見出す、真理を知る 388 自己の死 389 死の観念へのこだわり、『精神現象学』序文 391 経験的現存在(原文引用) 392 動物の有限性との関連 393 動物の病いあるいは精神の生成 394 人間と動物、病いと死の位相 394 動物は死ぬ(イエナ講義、1805-1806年) 395 人間は自然に内在する死に至る病いである 396 否定的絶対者 398 恐怖政治、革命、国家 399 歴史は死を前提にする 400 北アメリカの未開人は親を殺し、我々も同じことをする(→「ヘーゲルと親殺し」) 400 子供を教育することにより…… 401 『自然法』論文 402 普遍者としての国家 403 殺しあう戦争の必要性 406 国家の公民 407 個体は個別なもの普遍なものとの総合だ! 409 死は完成——ヘーゲルは、死は完成といったけど、私は、「よい死に方」を主張した講演会で、会場の聴衆の1人から、子供の死もよい死ですか?と聞 かれてはじめて、自分が、人生において理想的な死(ヘーゲル的死)を前提にしていることに気付かされた。 410 主と奴の血の闘争 415 他者を死に至らしめねば他者が総体であるかどうかを知ることができぬ(→「先住民による人体実験とその推論に関する資料と紹介」pdf) 416 意識が他者の死を目的としている 418 奴の人間性を認めること 420 宗教は表象された精神 423 人間は空虚な無 424 ヘーゲル以外の哲学者は、魂は不死という同一性の概念から自由になれなかった 425 ハイデガーは、人間の現存在は死への生である 426 闘争と労働はマルクスへのバトンタッチ |

|

++++++++++++++

★

| Although not an orthodox Marxist,[6] Kojeve was known as an influential and idiosyncratic interpreter of Hegel, reading him through the lens of both Karl Marx and Martin Heidegger. The well-known end of history thesis advanced the idea that ideological history in a limited sense had ended with the French Revolution and the regime of Napoleon and that there was no longer a need for violent struggle to establish the "rational supremacy of the regime of rights and equal recognition". Kojeve's end of history is different from Francis Fukuyama's later thesis of the same name in that it points as much to a socialist-capitalist synthesis as to a triumph of liberal capitalism.[7][8] Mark Lilla notes that Kojève rejected the prevailing concept among European intellectuals of the 1930s that capitalism and democracy were failed artifacts of the Enlightenment that would be destroyed by either communism or fascism.[9] In contrast, while initially somewhat more sympathetic to the Soviet Union than the United States, Kojève devoted much of his thought to protecting western European autonomy, particularly so France, from domination by either the Soviet Union or the United States. He believed that the capitalist United States represented right-Hegelianism while the state-socialist Soviet Union represented left-Hegelianism. Thus, victory by either side, he posited, would result in what Lilla describes as "a rationally organized bureaucracy without class distinctions".[10] | コジェーヴは正統派のマルクス主義者ではない(=もちろんソビエト信奉 者ではあった:オフレの所論)が、カール・マルクスとマルティン・ハイデガーの両方のレンズを通してヘーゲルを読み解く、影響力のある特異な解釈者として 知られていた。よく知られている歴史の終わりのテーゼは、限定的な意味でのイデオロギーの歴史はフランス革命とナポレオンの政権で終わり、「権利と平等な 承認の体制の合理的な優位性」を確立するために暴力的な闘争をする必要はもはやないという考えを進めた。コジェーヴの歴史の終わりは、後にフランシス・フ クヤマが発表した同名の論文とは異なり、自由主義資本主義の勝利ではなく、社会主義と資本主義の統合を指し示している。マーク・リラは、コジェーヴが、資 本主義と民主主義は啓蒙主義の失敗作であり、共産主義かファシズムによって破壊されるという1930年代のヨーロッパの知識人の一般的な概念を否定したこ とを指摘している。一方、コジェーヴは、当初はアメリカよりもソ連にやや同情的であったが、西ヨーロッパの自治、特にフランスをソ連やアメリカの支配から 守ることに思想の多くを費やした。彼は、資本主義のアメリカは右ヘゲリアニズム、国家社会主義のソ連は左ヘゲリアニズムだと考えていました。そのため、ど ちらかが勝利すれば、リラが言うところの「階級の区別のない合理的に組織された官僚主義」が実現すると考えていた。 |

| Kojève's lectures on Hegel were collected, edited and published by Raymond Aron in 1947, and published in abridged form in English in the now classic Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit. His interpretation of Hegel has been one of the most influential of the past century. His lectures were attended by a small but influential group of intellectuals including Raymond Queneau, Georges Bataille, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, André Breton, Jacques Lacan, Raymond Aron, Michel Leiris, Henry Corbin and Éric Weil. His interpretation of the master–slave dialectic was an important influence on Jacques Lacan's mirror stage theory. Other French thinkers who have acknowledged his influence on their thought include the post-structuralist philosophers Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. | コジェーヴのヘーゲルに関する講義は、1947年にレイモンド・アロン によって収集・編集・出版され、現在では古典的な『Introduction to the Reading of Hegel』として英語で要約されて出版されている。Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit(精神現象学についての講義)』として英語で出版された。彼のヘーゲル解釈は、過去100年で最も影響力のあるものの一つである。彼の講義に は、レイモン・クノー、ジョルジュ・バタイユ、モーリス・メルロ=ポンティ、アンドレ・ブルトン、ジャック・ラカン、レイモン・アロン、ミシェル・レイリ ス、ヘンリー・コービン、エリック・ワイルなど、少数ながらも影響力のある知識人たちが参加していた。彼の主従弁証法の解釈は、ジャック・ラカンの鏡像段 階説に重要な影響を与えた。また、ポスト構造主義の哲学者であるミシェル・フーコーやジャック・デリダなども彼の影響を認めている。 |

| Kojeve's correspondence with Leo Strauss has been published along with Kojève's critique of Strauss's commentary on Xenophon's Hiero.[11] In the 1950s, Kojève also met the rightist legal theorist Carl Schmitt, whose "Concept of the Political" he had implicitly criticized in his analysis of Hegel's text on "Lordship and Bondage"[additional citation(s) needed] . Another close friend was the Jesuit Hegelian philosopher Gaston Fessard. | コジェーヴとレオ・シュトラウスとの往復書簡は、クセノフォンの『ヒエ ロ』に対するシュトラウスの注釈に対するコジェーヴの批判とともに出版されている。1950年代、コジェーヴは右派の法理論者カール・シュミットにも会っ ている。彼の「政治的概念」は、ヘーゲルの「領主権と束縛」に関するテキストの分析において暗に批判していた[要追加引用]。もう一人の親しい友人は、イ エズス会のヘーゲル哲学者ガストン・フェサールである。 |

| In addition to his lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit, Kojève's other publications include a little noticed book on Immanuel Kant and articles on the relationship between Hegelian and Marxist thought and Christianity. His 1943 book Esquisse d'une phenomenologie du droit, published posthumously in 1981, elaborates a theory of justice that contrasts the aristocratic and bourgeois views of the right. Le Concept, le temps et le discours extrapolates on the Hegelian notion that wisdom only becomes possible in the fullness of time. Kojève's response to Strauss, who disputed this notion, can be found in Kojève's article "The Emperor Julian and his Art of Writing".[12] | コジェーヴは、『精神現象学』の講義のほかに、あまり注目されていない イマヌエル・カントについての著書や、ヘーゲル思想やマルクス主義思想とキリスト教との関係についての論文などを発表している。1943年に出版された "Esquisse d'une phenomenologie du droit"(『法の現象学』)は、1981年に死後出版されたもので、貴族とブルジョアの右派の見解を対比させた正義論を詳述している。"Le Concept, le temps et le discours"(『概念・時間・言説』)は、知恵は時が満ちることで初めて可能になるというヘーゲルの考え方を外挿したものである。この考え方に異議 を唱えたシュトラウスに対するコジェーヴの回答は、コジェーヴの論文「皇帝ユリウスとその著述術」にある。 |

| Kojève also challenged Strauss' interpretation of the classics in the voluminous Esquisse d'une histoire raisonnée de la pensée païenne which covers the pre-Socratic philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, as well as Neoplatonism. While the first volume of the previous work was still published during his life-time, most of his writings remained unpublished until recently. These are becoming the subject of increased scholarly attention. The books that have so far been published are the two remaining volumes of the Esquisse d'une histoire raisonnée de la pensée païenne (1972, 1973 [1952]), Outline of a Phenomenology of Right (1981 [1943]), L'idée du déterminisme dans la physique classique et dans la physique moderne (1990 [1932]), Le Concept, le Temps et Le Discours (1990[1952]), L'Athéisme (1998[1931]), The Notion of Authority (2004[1942]), and "Identité et Réalité dans le "Dictionnaire" de Pierre Bayle" (2010[1937]). Several of his shorter texts are also gathering greater attention and some are being published in book form as well. | コジェーヴは、また、ソクラテス以前の哲学者であるプラトンやアリスト テレス、そして新プラトン主義を網羅した広闊な分量のある"Esquisse d'une histoire raisonnée de la pensée païenne"で、シュトラウスの古典解釈に挑戦している。前作の第1巻は生前にも出版されていたが、彼の著作の多くは近年まで未発表であった。これら は、学術的にも注目されるようになってきた。これまでに出版された書籍は、"Esquisse d'une histoire raisonnée de la pensée païenne"(1972年、1973年[1952])、"Outline of a Phenomenology of Right"(1981年[1943])の残りの2巻である。L'idée du déterminisme dans la physique classique et dans la physique modernne (1990[1932]), Le Concept, le Temps et Le Discours (1990[1952]), L'Athéisme (1998[1931]), The Notion of Authority (2004[1942]), and "Identité et Réalité dans le "Dictionnaire" de Pierre Bayle" (2010[1937])などがある。また、短い文章も注目されており、書籍化されているものもある。 |

★

★

●

■5分割ファイル(with

password):Kojev_Hegel_jap_Part1.pdf/Kojev_Hegel_jap_Part2.pdf/Kojev_Hegel_jap_Part3.pdf/Kojev_Hegel_jap_Part4.pdf/Kojev_Hegel_jap_Part5.pdf/

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

☆

☆

☆