アフロ系エクアドル人

Afro-Ecuadorians

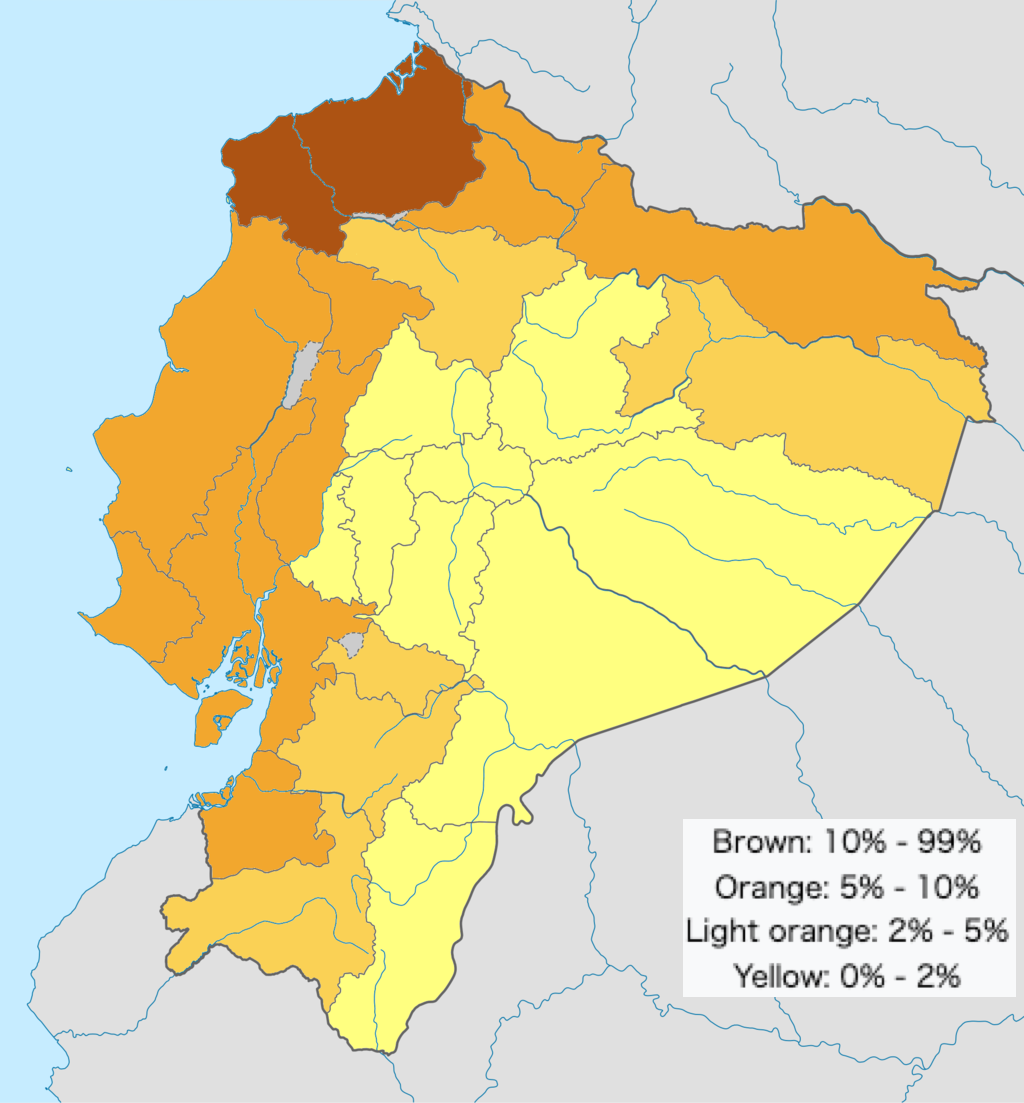

Población afrodescendiente del Ecuador por provincia en 2010 // Los tres mulatos de Esmeraldas (1599) by Sánchez Galque.

☆アフロ・エクアドル人(スペイン語: Afroecuatorianos)は、主にサハラ以南アフリカ系祖先を持つエクアドル人を指す。別名として黒人エクアドル人(スペイン語: Ecuatorianos Negros)とも呼ばれる。

| Afro-Ecuadorians

(Spanish: Afroecuatorianos), also known as Black Ecuadorians (Spanish:

Ecuatorianos Negros), are Ecuadorians of predominantly Sub-Saharan

African descent.[2] |

アフロ・エクアドル人(スペイン語: Afroecuatorianos)は、主にサハラ以南アフリカ系祖先を持つエクアドル人を指す。別名として黒人エクアドル人(スペイン語: Ecuatorianos Negros)とも呼ばれる。 |

History and background Los tres mulatos de Esmeraldas (1599) by Sánchez Galque. Most Afro-Ecuadorians are the descendants of enslaved Africans who were transported by predominantly British slavers to Ecuador from the early 16th century.[3] In 1553, the first enslaved Africans reached Ecuador in Quito when a slave ship heading to Peru was stranded off the Ecuadorian coast. The enslaved Africans escaped and established maroon settlements in Esmeraldas, which became a safe haven as many Africans fleeing slave conditions either escaped to there or were forced to live there. Eventually, they started moving from their traditional homeland and were settling everywhere in Ecuador.[4]  Portrait of a Quito Matron Lady with Her Black Slave (1783) by Vicente Albán. Racism is an issue on an individual basis and societally. Afro-Ecuadorians are strongly discriminated against by the mestizo and criollo populations.[5][6] As a result of this racism, along with lack of government funding and low social mobility, poverty affects their community more so than the white and mestizo population of Ecuador.[7][8] After slavery was abolished in 1851, Africans became marginalized in Ecuador, dominated by the plantation owners.[9]  A typical street scene in Esmeraldas (2005). Afro-Ecuadorian people and culture are found primarily in the country's northwest coastal region. The majority of the Afro-Ecuadorian population (70%)[10] are found in the province of Esmeraldas and the Valle del Chota in the Imbabura Province, where they are the majority.[11] They can be also found in significant numbers in Guayaquil, and in Ibarra, where in some neighborhoods, they make up a majority.[12] Many Afro-Ecuadorians have participated in sports, for instance playing with the Ecuador national football team, many of whom hail from Valle del Chota.[13] |

歴史と背景 サンチェス・ガルケ作「エスメラルダスの三人のムラートたち」(1599年)。 ほとんどのアフロ・エクアドル人は、16世紀初頭から主に英国人奴隷商人によってエクアドルに運ばれた奴隷アフリカ人の子孫である[3]。1553年、ペ ルーに向かう奴隷船がエクアドル沿岸で座礁し、最初の奴隷アフリカ人がキトのエクアドルに到着した。奴隷にされたアフリカ人は脱走し、エスメラルダスに逃 亡者たちの集落を設立した。この集落は、奴隷の生活から逃れた多くのアフリカ人が逃亡先として、あるいは強制的に住まわせられた場所として、安全な避難所 となった。やがて、彼らは伝統的な故郷から移動を始め、エクアドルの各地に定住していった。[4]  ビセンテ・アルバン作『黒人奴隷を連れたキトの貴婦人の肖像』(1783年) 人種主義は個人レベルでも社会レベルでも問題だ。アフリカ系エクアドル人はメスティソやクリオージョ層から強い差別を受けている。[5] [6] この人種主義に加え、政府資金の不足と社会的流動性の低さから、貧困はエクアドルの白人やメスティーソ人口よりも彼らのコミュニティに深刻な影響を与えて いる。[7][8] 1851年に奴隷制が廃止された後、アフリカ系住民はプランテーション所有者に支配され、エクアドルで周縁化されていった。[9]  エスメラルダスの典型的な街の風景(2005年)。 アフロ・エクアドル系の人民と文化は、主に国の北西沿岸地域に存在する。アフロ・エクアドル系人口の大半(70%)[10]はエスメラルダス県とインバブ ラ県のチョタ渓谷に集中し、これらの地域では彼らが多数派を占める。[11] またグアヤキルやイバラでも相当数が確認され、イバラでは特定の地区で多数派を形成している。[12] 多くのアフリカ系エクアドル人がスポーツ分野で活躍しており、例えばエクアドル代表サッカーチームにはチョタ渓谷出身の選手が多数在籍している。[13] |

Culture Afro-Ecuadorians at a convention to receive cultural recognition, traditional instruments can be seen in the background Afro-Ecuadorian culture may be analysed by considering the two main epicenters of historical presence: the province of Esmeraldas, and the Chota Valley.[14] In Ecuador it is often said that Afro Ecuadorians live predominantly in warm places like Esmeraldas.[15] Afro-Ecuadorian culture is a result of the Trans-atlantic slave trade.[11] Their culture and its impact on Ecuador has led to many aspects from West and Central Africa cultures being preserved via ordinary acts of resistance and commerce.[16] Examples of these include the use of polyrhythmic techniques, traditional instruments and dances; along with food ways such as the use of crops brought from Africa, like the Plantain and Pigeon pea, and oral traditions and mythology like La Tunda.[17][18][19][20] When women wear their hair as it grows naturally, it is often associated with poverty, which is why successful or upwardly mobile women tended to straighten their hair.[21] |

文化 文化的な認知を得るための集会に参加するアフリカ系エクアドル人。背景には伝統楽器が見える アフリカ系エクアドル文化は、歴史的な存在の二大中心地であるエスメラルダス県とチョタ渓谷を考慮することで分析できる。[14] エクアドルでは、アフロ系エクアドル人が主にエスメラルダスのような温暖な地域に住んでいると言われることが多い。[15] アフロ系エクアドル文化は大西洋奴隷貿易の結果である。[11] 彼らの文化とエクアドルへの影響は、抵抗や商業といった日常的な行為を通じて、西・中央アフリカ文化の多くの側面が保存される結果をもたらした。[16] その例としては、ポリリズム技法や伝統楽器・舞踊の使用、プランテンやピジョンピーといったアフリカ由来作物の利用といった食文化、ラ・トゥンダのような 口承伝承や神話などが挙げられる。[17][18][19] [20] 女性が髪を自然なまま伸ばして着けることは、しばしば貧困と結びつけられる。そのため、成功した女性や社会的地位を上昇させた女性は、髪をストレートに伸 ばす傾向があった。[21] |

Music A typical marimba from Esmeraldas. Marimba music is popular from Esmeraldas to the Pacific Region of Colombia. It was considered an Intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO in 2010.[22] It gets its name from the prominent use of marimbas, but is accompanied along with dances, chants, drums and other instruments specific to this region such as the bombo, the cununo and the guasá.[23]  An example of the Cununo in the semi-final round of a championship in Esmeraldas. Sometimes this music is played in religious ceremonies, as well as in celebrations and parties. It features call-and-response chanting along with the music. Some of the rhythms associated with it are currulao, bambuco and andarele.[24]  Afro-Ecuadorian style drum from Esmeralda. On the other hand, in the Chota Valley there is bomba music. It can vary from mid-tempo to a very fast rhythm. It is usually played with guitars, as well as the main local instrument called bomba, which is a drum, along with a guiro, and sometimes bombos and bongos. A variation of it played by la banda mocha, groups who play bomba with a bombo, guiro and plant leaves to give melody.[25] Religion The religious practice among Afro-Ecuadorians is usually Catholic. Catholic worship is distinctive in Esmeraldas, and sometimes is done with marimba.[26][27] |

音楽 エスメラルダス地方の典型的なマリンバ。 マリンバ音楽はエスメラルダスからコロンビア太平洋地域にかけて人気がある。2010年にユネスコ無形文化遺産に登録された[22]。マリンバを主楽器とするが、踊りや詠唱、太鼓に加え、ボンボ、クヌノ、グアサなどこの地域特有の楽器も伴奏に用いられる[23]。  エスメラルダス州選手権準決勝におけるクヌノの演奏例。 この音楽は宗教儀式や祝祭、宴会で演奏されることもある。音楽に合わせて応答形式の詠唱が特徴だ。関連するリズムにはクルラオ、バンブコ、アンダレレなどがある。[24]  エスメラルダス産のアフロ・エクアドル様式ドラム。 一方、チョタ渓谷ではボンバ音楽が存在する。中速から非常に速いリズムまで様々だ。通常はギターと、ボンバと呼ばれる主要な現地楽器(太鼓)に加え、ギ ロ、時にはボンボやボンゴで演奏される。ボンボ、ギロ、植物の葉で旋律を奏でる「ラ・バンダ・モチャ」というグループによる演奏形態もある。[25] 宗教 アフリカ系エクアドル人の宗教的慣習は、通常カトリックである。エスメラルダスにおけるカトリックの礼拝は独特で、時にマリンバを用いて行われることがある。[26][27] |

Political framework Dr. Diana Salazar Méndez, Attorney General - Quito (2019) Numerous organizations have been established in Ecuador to for Afro-Ecuadorian issues. The Afro-Ecuadorian Development Council (CONDAE). Afro-Ecuadorian Development Corporation (Corporación de Desarrollo Afroecuatoriano, CODAE), institutionalized in 2002, Asociación de Negros Ecuatorianos (ASONE), founded in 1988, Afro-Ecuadorian Institute, founded 1989, the Agustín Delgado Foundation, the Black Community Movement (El Proceso de Comunidades Negras) and The National Confederation of Afro-Ecuadorians (Confederación Nacional Afroecuatoriana, CNA) are amongst some of the institutional frameworks in place in Ecuador.[9] The World Bank has given loans for Afro-Ecuadorian development proposals in Ecuador since 1998, loaning $34 million for related projects between 2003 and 2007, and USAID also monitored the 2006 elections in Ecuador to ensure that Afro-Ecuadorians were not being unfairly underrepresented.[9] |

政治的枠組み ダイアナ・サラザール・メンデス博士、検事総長 - キト (2019) エクアドルでは、アフリカ系エクアドル人の問題に取り組むために数多くの組織が設立されている。アフリカ系エクアドル人開発評議会(CONDAE)。 2002年に制度化されたアフリカ系エクアドル人開発公社(Corporación de Desarrollo Afroecuatoriano, CODAE)、1988年に設立されたエクアドルニグロ協会(Asociación de Negros Ecuatorianos, ASONE)、 1989年創設のアフロ・エクアドル研究所、アグスティン・デルガド財団、黒人コミュニティ運動(El Proceso de Comunidades Negras)、全国アフロ・エクアドル人連合(Confederación Nacional Afroecuatoriana, CNA)などが、エクアドルに存在する制度的枠組みの一部である。[9] 世界銀行は1998年以降、エクアドルにおけるアフリカ系エクアドル人の開発提案に対して融資を行っており、2003年から2007年にかけて関連プロ ジェクトに3400万ドルを貸し付けた。また米国国際開発庁(USAID)は、アフリカ系エクアドル人が不当に過小評価されないよう、2006年のエクア ドル選挙を監視した。[9] |

| Notable Afro-Ecuadorians Historical Alonso de Illescas (1528-1600s), African Maroon leader in Esmeraldas in colonial Ecuador Francisco de Arobe (1543 - after 1606) leader of Afro-indigenous maroon communities María del Tránsito Sorroza, midwife and formerly enslaved woman Martina Carrillo (1750–1778), Ecuadorian activist, born enslaved, who fought for the rights of Afro-Ecuadorians Politics Government Diana Salazar Méndez, Attorney General of Ecuador Lucía Sosa, Mayor of Esmeraldas from 2005 to 2013 and 2014 to 2018 Paola Cabezas, first Afro-Ecuadorian presenter of Ecuador TV and politician[28] Activism Jaime Hurtado, from Guayaquil; known for fighting for the rights of the working people of Ecuador; founder and leader of the Democratic People's Movement (MPD); assassinated in the winter of 1999[29] Music Guillermo Ayoví Erazo, Ecuadorian Marimba player and singer Karla Kanora, Ecuadorian singer Eddy More, Ecuadorian songwriter Jordan Quintero, Ecuadorian singer Literature Adalberto Ortiz (1914–2003), poet, diplomat and author Nelson Estupiñán Bass (1912–2012), poet and author Sports Boxing Carlos Andrés Mina, Ecuadorian Light heavyweight boxer María José Palacios, Ecuadorian women's Olympic lightweight boxer Érika Pachito, Ecuadorian women's Olympic middleweight boxer Judo Carmen Chalá, Ecuadorian Olympic Judoka Diana Chalá, Ecuadorian Olympic Judoka Vanessa Chalá, Ecuadorian Olympic Judoka Discus Juan José Caicedo, Ecuadorian discus thrower that competed in the 2020 Summer Olympics Weightlifting Neisi Dajomes, Gold medalist for women's weightlifting in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics Tamara Salazar, Silver medalist for women's weightlifting in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics Angie Palacios, Ecuadorian Olympic weightlifter and sister of Neisi Dajomes Alexandra Escobar, Ecuadorian Olympic weightlifter Oliba Nieve, Gold medalist for women's weightlifting in 2007 Pan American Games Sprinting Álex Quiñónez, Ecuadorian Olympic sprinter; finalist in 200-meter dash at the 2012 Summer Olympics Ángela Tenorio, Ecuador Olympic sprinter Yuliana Angulo, Ecuadorian Olympic sprinter Virginia Villalba, Ecuadorian Olympic sprinter[30][31] Football Gabriel Achilier, player Darío Aimar, player Franklin Anangonó, player and manager Brayan Angulo, player Nilson Angulo, player Tamara Angulo, player Rorys Aragón, player Robert Arboleda, player Michael Arroyo, player Jaime Ayoví, player Walter Ayoví, player Óscar Bagüí, player Maximo Banguera, player Christian Benítez, player Álex Bolaños, player Alexander Bolaños, player Nayely Bolaños, player Miller Bolaños, player Adrián Bone, player Carina Caicedo, player Felipe Caicedo, player Jessy Caicedo, player Moisés Caicedo, player Wilson Carabalí, player and manager Byron Castillo, player Segundo Castillo, player and manager Juan Cazares, player Walter Chalá, player Nicole Charcopa, player José Cifuentes, player Janner Corozo, player Ulises de la Cruz, player Agustin Delgado, player hailing from Juncal village; signed a $3.5 million deal with the team from Southampton, England in 2001 Alexander Domínguez, player Frickson Erazo, player Giovanny Espinoza, player Pervis Estupiñán, player Christian García, player Carlos Gruezo, player Jorge Guagua, player Joffre Guerrón, player Renato Ibarra, player Romario Ibarra, player Anderson Julio, player Ivan Hurtado, player Jhojan Julio, player Jefferson Lara, player Juan Carlos León, player and manager Fidel Martínez, player Édison Méndez, player and manager Sebas Méndez, player for the Orlando City SC Arturo Mina, player Katherine Ortiz, player Willian Pacho, player Jairo Padilla, player Diego Palacios, player Juan Carlos Paredes, player Gonzalo Plata, player Joao Plata, player Ángelo Preciado, player Ayrton Preciado, player Mónica Quinteros, player Hólger Quiñónez, player and manager Djorkaeff Reasco, player Néicer Reasco, player Moisés Ramírez, player Kerlly Real, player Jhafets Reyes, player Kevin Rodríguez, player Alberto Spencer (1937–2006), player and all-time top scorer of the Copa Libertadores Antonio Valencia, player for Manchester United and Ecuador national team Enner Valencia, player for Internacional and Ecuador national team José Valencia, player Gustavo Vallecilla, player Erika Vásquez, player Pedro Velasco, player Wendy Villón, player and manager John Yeboah, player |

著名なアフリカ系エクアドル人 歴史 アロンソ・デ・イレスカス(1528年~1600年代)、植民地時代のエクアドル、エスメラルダスにおけるアフリカ系逃亡奴隷の指導者 フランシスコ・デ・アロベ(1543年~1606年以降)、アフリカ系先住民逃亡奴隷コミュニティの指導者 マリア・デル・トランシト・ソロサ、助産師、元奴隷 マルティナ・カリージョ(1750年~1778年)、エクアドルの活動家、奴隷として生まれ、アフリカ系エクアドル人の権利のために戦った。 政治 政府 ダイアナ・サラサール・メンデス、エクアドル司法長官 ルシア・ソーサ、2005年から2013年、2014年から2018年までエスメラルダス市長 パオラ・カベサス、エクアドルテレビ初のアフロ系エクアドル人司会者、政治家[28] 活動 ハイメ・ウルタド、グアヤキル出身。エクアドルの労働人民の権利のために戦ったことで知られる。民主人民運動(MPD)の創設者であり指導者。1999年の冬に暗殺された[29] 音楽 ギジェルモ・アヨビ・エラソ、エクアドルのマリンバ奏者兼歌手 カーラ・カノラ、エクアドルの歌手 エディ・モア、エクアドルの作詞家 ジョーダン・キンテロ、エクアドルの歌手 文学 アダルベルト・オルティス(1914–2003)、詩人、外交官、作家 ネルソン・エストゥピニャン・バス(1912–2012)、詩人、作家 スポーツ ボクシング カルロス・アンドレス・ミナ、エクアドルのライトヘビー級ボクサー マリア・ホセ・パラシオス、エクアドルの女子オリンピックライト級ボクサー エリカ・パチート、エクアドルの女子オリンピックミドル級ボクサー 柔道 カルメン・チャラ、エクアドルのオリンピック柔道家 ダイアナ・チャラ、エクアドルのオリンピック柔道家 ヴァネッサ・チャラ、エクアドルのオリンピック柔道家 円盤投げ フアン・ホセ・カイセド、2020年夏季オリンピックに出場したエクアドルの円盤投げ選手 重量挙げ ネイシ・ダホメス、2020年東京オリンピック女子重量挙げ金メダリスト タマラ・サラザール、2020年東京オリンピック女子重量挙げ銀メダリスト アンジー・パラシオス、エクアドルのオリンピック重量挙げ選手。ネイシ・ダホメスの妹 アレクサンドラ・エスコバル、エクアドルのオリンピック重量挙げ選手 オリバ・ニエベ、2007年パンアメリカン競技大会女子重量挙げ金メダリスト 短距離 アレックス・キニョネス、エクアドルのオリンピック短距離選手、2012年夏季オリンピック200メートル走決勝進出者 アンヘラ・テノリオ、エクアドルのオリンピック短距離選手 ユリアナ・アングロ、エクアドルのオリンピック短距離選手 バージニア・ビジャルバ、エクアドルのオリンピック短距離選手[30][31] サッカー ガブリエル・アチリエル、選手 ダリオ・アイマール、選手 フランクリン・アナンゴノ、選手、監督 ブレイアン・アングロ、選手 ニルソン・アングロ、選手 タマラ・アングロ、選手 ロリス・アラゴン、選手 ロベルト・アルボレダ、選手 マイケル・アロヨ、選手 ハイメ・アヨビ、選手 ウォルター・アヨビ、選手 オスカル・バギ、選手 マキシモ・バンゲラ、選手 クリスチャン・ベニテス、選手 アレックス・ボラニョス、選手 アレクサンダー・ボラニョス、選手 ナイエリ・ボラニョス、選手 ミラー・ボラニョス、選手 アドリアン・ボーン、選手 カリーナ・カイセド、選手 フェリペ・カイセド、選手 ジェシー・カイセド、選手 モイセス・カイセド、選手 ウィルソン・カラバリ、選手兼監督 バイロン・カスティーヨ、選手 セグンド・カスティーヨ、選手兼監督 フアン・カサレス、選手 ウォルター・チャラ、選手 ニコール・チャルコパ、選手 ホセ・シフエンテス、選手 ジャナー・コロソ、選手 ウリセス・デ・ラ・クルス、選手 アグスティン・デルガド、選手。ジュンカル村出身。2001年にイングランドのサウサンプトンと350万ドルで契約した。 アレクサンダー・ドミンゲス、選手 フリクソン・エラゾ、選手 ジョバンニ・エスピノサ、選手 パーヴィス・エストゥピニャン、選手 クリスチャン・ガルシア、選手 カルロス・グルエゾ、選手 ホルヘ・グアグア、選手 ホフレ・ゲロン、選手 レナート・イバラ、選手 ロマリオ・イバラ、選手 アンダーソン・フリオ、選手 イバン・ウルタド、選手 ジョハン・フリオ、選手 ジェファーソン・ララ、選手 フアン・カルロス・レオン、選手兼監督 フィデル・マルティネス、選手 エディソン・メンデス、選手兼監督 セバス・メンデス、オルランド・シティSCの選手 アルトゥーロ・ミナ、選手 キャサリン・オルティス、選手 ウィリアン・パチョ、選手 ハイロ・パディージャ、選手 ディエゴ・パラシオス、選手 フアン・カルロス・パレデス、選手 ゴンサロ・プラタ、選手 ジョアン・プラタ、選手 アンジェロ・プレシアド、選手 アイルトン・プレシアド、選手 モニカ・キンテロス、選手 ホルガー・キニョネス、選手兼監督 ジョルカエフ・レアスコ、選手 ネイセル・レアスコ、選手 モイセス・ラミレス、選手 カーリー・リアル、選手 ジャフェッツ・レイエス、選手 ケビン・ロドリゲス、選手 アルベルト・スペンサー(1937–2006)、選手。コパ・リベルタドーレス歴代最多得点者 アントニオ・バレンシア、マンチェスター・ユナイテッド及びエクアドル代表選手 エンネル・バレンシア、インテルナシオナル及びエクアドル代表選手 ホセ・バレンシア、選手 グスタボ・バレシーヤ、選手 エリカ・バスケス、選手 ペドロ・ベラスコ、選手 ウェンディ・ビヨン、選手兼監督 ジョン・イェボア、選手 |

| Afro-Latin Americans List of Afro-Latinos |

アフリカ系ラテンアメリカ人 アフリカ系ラテンアメリカ人の一覧 |

| References 1. "Ecuador: Censo de Población y Vivienda 2022" (PDF). censoecuador.gob.ec. 21 September 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2024. 2. "MAR | Data | Assessment for Blacks in Ecuador". www.mar.umd.edu. Retrieved 2021-08-12. 3. "Up from slavery, Afro-Ecuadorians continue the struggle for their place in society". CuencaHighLife. 2018-10-15. Archived from the original on 2020-11-06. Retrieved 2021-08-12. 4. "Afro-Ecuadorian - Afropedea". www.afropedea.org. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved 2021-08-12. 5. "Much work needed to 'target unacceptable levels' of racism in Ecuador: UN experts". UN News. 2019-12-23. Retrieved 2021-05-27. 6. "Afro-Ecuadorians". Minority Rights Group. Retrieved 2021-05-27. 7. "Poverty rates in Ecuador". Statista. Retrieved 2021-05-27. 8. "Government should do more to reduce poverty among Afro-Ecuadorians, UN says". CuencaHighLife. 2019-12-26. Retrieved 2021-05-27. 9. "Assessment for Blacks in Ecuador". CIDCM. Archived from the original on June 22, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2012. 10. "Esmeraldas and its Afro-Ecuadorian Cultural Legacy". Sounds and Colours. 2015-06-19. Retrieved 2021-05-27. 11. "How Afro-Ecuadorians shaped the country's culture". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2021-05-27. 12. "Afro Ecuador – Freedom Is Mine". Retrieved 2021-08-12. 13. "In Ecuador, a poor valley gets a kick start". Christian Science Monitor. 2006-12-27. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2021-08-12. 14. "Ecuadorian Culture: Customs, History, Society, Food | don Quijote". www.donquijote.org. Retrieved 2021-05-27. 15. "Mónica, the first | Translation". Radio Ambulante. 2022-04-26. Retrieved 2022-05-28. 16. Ph. D., History; M. A., History; B. A., Rhodes College. "There Were 3 Major Ways That Enslaved People Resisted a Life in Bondage". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2021-05-27. 17. "A Botanical Story of Slavery and the Survival of the Wisdom of Africa". Hidden Garden. 2016-08-04. Retrieved 2021-05-27. 18. "Pigeonpea". Crop Wild Relatives. Retrieved 2021-05-27. 19. Breslin, Patrick (2007). "Juan Garcia and the Oral Tradition of Afro-Ecuador". hdl:10644/5940. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) 20. "La Tunda es un mito afroecuatoriano con fondo emancipador". El Comercio (in Spanish). Retrieved 2021-05-27. 21. Lago, Ivonne. "Paola Cabezas: "A la vida hay que ponerle tumbao"". www.expreso.ec. Retrieved 2022-05-28. 22. "UNESCO - Marimba music, traditional chants and dances from the Colombia South Pacific region and Esmeraldas Province of Ecuador". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 2021-08-12. 23. Cornejo, Santiago Carcélen; Ordóñez, Fabricio Morales, The Guardians of the Marimba, the Cununo and the Guasa (in Spanish), retrieved 2021-08-12 24. "Discover the Afroecuadorian culture". This Is Ecuador. 2019-02-27. Retrieved 2021-08-12. 25. Velasco, Estefanía. "La Bomba, símbolo musical de resistencia de la minoría afroecuatoriana". El Comercio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2021-08-12. Retrieved 2021-08-12. 26. "Marimba importance on the religious aspects of Afro-Ecuadorians" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-01-14. 27. Gonzalez, David; Alarcón, Johis (2019-05-31). "Afro-Ecuadoreans Maintain Identity Through Spiritual Practices". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-08-12. 28. "Paola Cabezas: "A la vida hay que ponerle tumbao"". 2020-12-21. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 2022-05-28. 29. "Black Latin America". Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2006-11-29. 30. "Athletics VILLALBA Virginia Elizabeth". Tokyo 2020 Olympics. Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games. Archived from the original on 2021-08-10. Retrieved 2021-08-10. 31. "'We are one big heart' - how Ecuador's 4x100m women made Olympic history in Silesia | FEATURE | WRE 21 | World Athletics". www.worldathletics.org. Retrieved 2021-08-10. |

参考文献 1. 「エクアドル:2022年人口・住宅センサス」 (PDF). censoecuador.gob.ec. 2023年9月21日. 2024年5月22日閲覧。 2. 「MAR | データ | エクアドルにおける黒人に関する評価」. www.mar.umd.edu. 2021年8月12日閲覧。 3. 「奴隷制からの解放後も、アフリカ系エクアドル人は社会における自らの地位を求める闘いを続けている」。クエンカ・ハイライフ。2018年10月15日。2020年11月6日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2021年8月12日に閲覧。 4. 「アフリカ系エクアドル人 - Afropedia」。www.afropedea.org. 2020年9月18日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2021年8月12日に取得。 5. 「エクアドルにおける人種主義の『許容できない水準』に対処するには多くの取り組みが必要:国連専門家」。国連ニュース。2019年12月23日。2021年5月27日に取得。 6. 「アフロ・エクアドル人」. マイノリティ・ライツ・グループ. 2021年5月27日閲覧. 7. 「エクアドルの貧困率」. スタティスタ. 2021年5月27日閲覧. 8. 「国連、アフロ・エクアドル人の貧困削減に向け政府のさらなる取り組みを要請」. クエンカ・ハイライフ. 2019年12月26日。2021年5月27日閲覧。 9. 「エクアドルにおける黒人に関する評価」。CIDCM。2012年6月22日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2012年8月28日閲覧。 10. 「エスメラルダスとそのアフリカ系エクアドル人の文化的遺産」. サウンズ・アンド・カラーズ. 2015-06-19. 2021-05-27 閲覧. 11. 「アフリカ系エクアドル人が国の文化をどう形作ったか」. ロンリープラネット. 2021-05-27 閲覧. 12. 「アフロ・エクアドル – 自由は我がもの」。2021年8月12日閲覧。 13. 「エクアドル、貧しい谷間に活気が戻る」。クリスチャン・サイエンス・モニター。2006年12月27日。ISSN 0882-7729。2021年8月12日閲覧。 14. 「エクアドルの文化:習慣、歴史、社会、食 | ドン・キホーテ」。www.donquijote.org。2021年5月27日閲覧。 15. 「モニカ、最初の | 翻訳」。ラジオ・アンブランテ。2022年4月26日。2022年5月28日閲覧。 16. 歴史学博士号、歴史学修士号、ローズ大学文学士号。「奴隷たちは束縛された生活に抵抗する3つの主要な方法があった」。「人々」 ThoughtCo。2021年5月27日閲覧。 17. 「奴隷制とアフリカの知恵の生存に関する植物学的な物語」。ヒドゥン・ガーデン。2016年8月4日。2021年5月27日閲覧。 18. 「ピジョンピー」。作物野生近縁種。2021年5月27日閲覧。 19. ブレズリン、パトリック(2007)。「 フアン・ガルシアとアフロ・エクアドルの口承伝統」. hdl:10644/5940. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) 20. 「ラ・トゥンダは解放を背景とするアフロ・エクアドルの神話である」. エル・コメルシオ (スペイン語). 2021-05-27 取得. 21. ラゴ, イボンヌ. 「パオラ・カベサス:『人生にはタンバオを加えるべきだ』」。www.expreso.ec。2022年5月28日閲覧。 22. 「ユネスコ - コロンビア南太平洋地域及びエクアドル・エスメラルダス州のマリンバ音楽、伝統的詠唱及び舞踊」。ich.unesco.org。2021年8月12日閲覧。 23. コルネホ、サンティアゴ・カルセレン; オルドニェス、ファブリシオ・モラレス, 『マリンバ、クヌノ、グアサの守護者たち』(スペイン語), 2021年8月12日閲覧 24. 「アフロエクアドル文化を発見せよ」. This Is Ecuador. 2019年2月27日. 2021年8月12日閲覧. 25. ヴェラスコ、エステファニア。「ラ・ボンバ、アフロ・エクアドル人少数派の抵抗の音楽的象徴」。エル・コメルシオ(スペイン語)。2021年8月12日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2021年8月12日に取得。 26. 「アフロ・エクアドル人の宗教的側面におけるマリンバの重要性」(PDF)。2014年1月14日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた(PDF)。 27. ゴンザレス、デイビッド;アラルコン、ジョイス(2019年5月31日)。「アフロ・エクアドル人は精神的実践を通じてアイデンティティを維持する」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ。ISSN 0362-4331。2021年8月12日に取得。 28. 「パオラ・カベサス:『人生にはタンバオを加えねばならない』」. 2020年12月21日. 2020年12月21日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2022年5月28日に閲覧. 29. 「黒人ラテンアメリカ」. 2021年8月29日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2006年11月29日に取得。 30. 「陸上競技 ヴィジャルバ・バージニア・エリザベス」. 東京2020オリンピック. 東京オリンピック・パラリンピック競技大会組織委員会. 2021年8月10日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2021年8月10日に取得. 31. 「『私たちは一つの大きな心』― エクアドル女子4×100mリレーチームがシレジアでオリンピック史に名を刻んだ経緯 | FEATURE | WRE 21 | World Athletics」. www.worldathletics.org. 2021年8月10日に閲覧. |

| Centro Cultural Afroecuatoriano Website with much information on this subject |

アフロエクアドル文化センターウェブサイト。この主題に関する情報が豊富にある。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afro-Ecuadorians |

Indio Yumbo de Maynas con su carga

(1783; Museo de América, Madrid)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099