衒示的消費

conspicuous consumption, げんじてきしょうひ

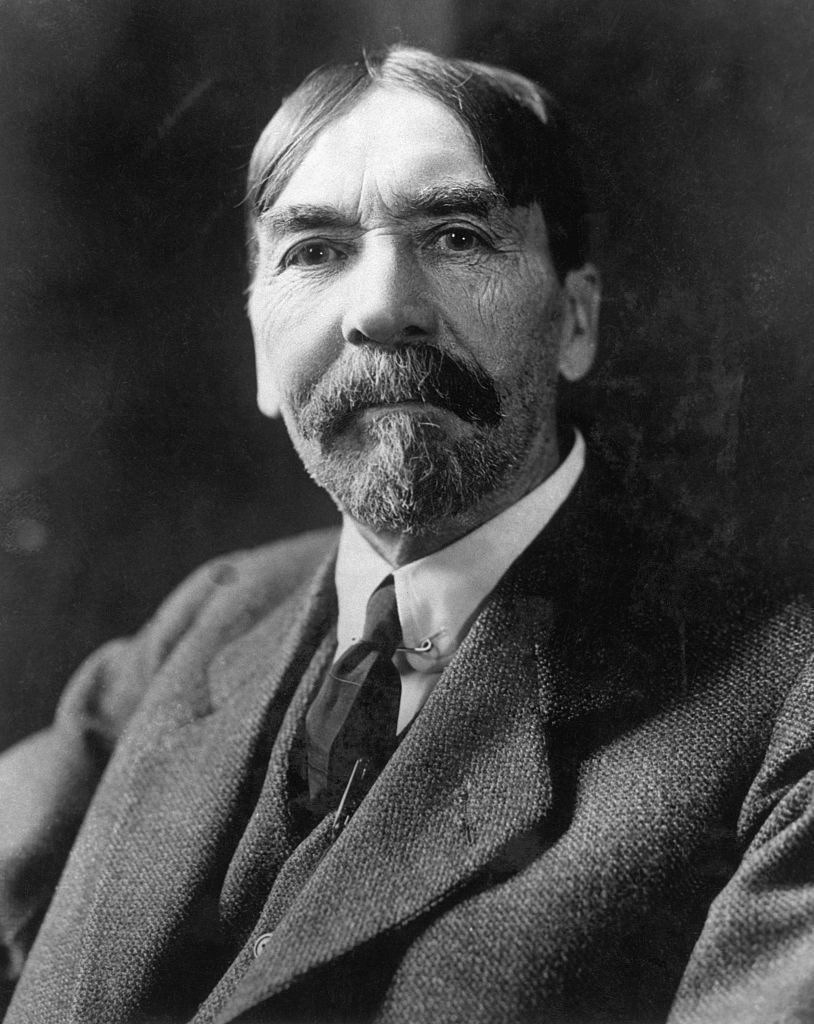

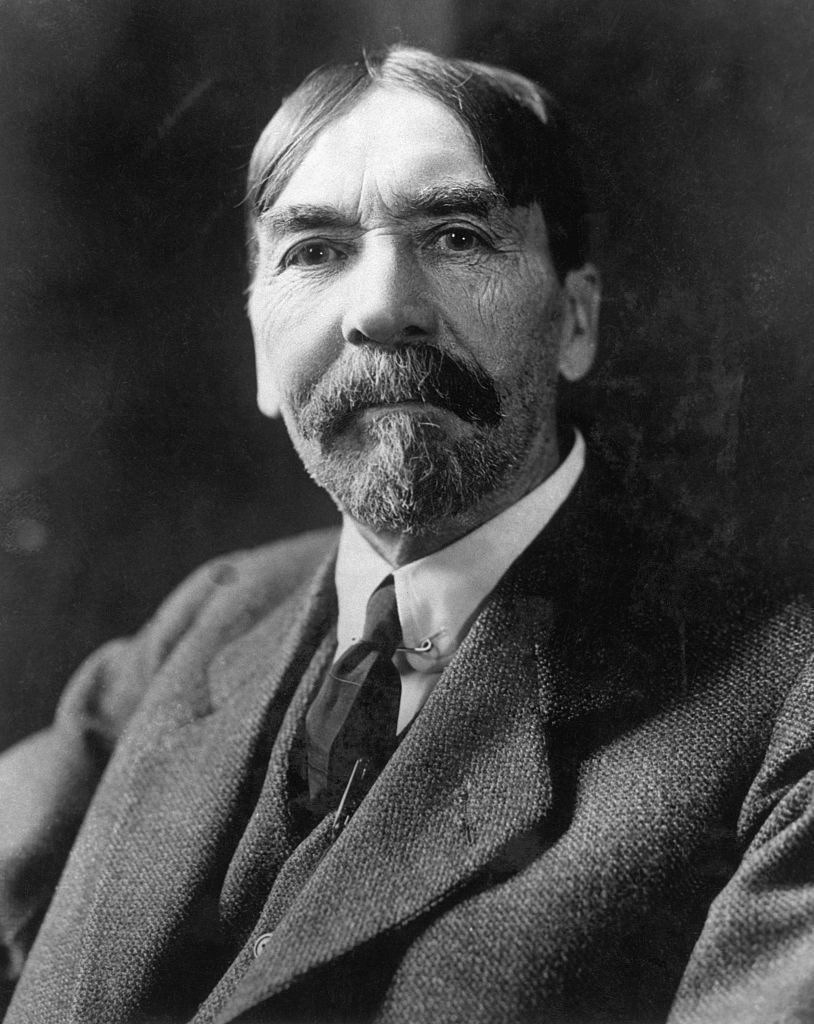

Thorstein Veblen, 1857-1929

☆ 19世紀末の富裕階級を「余暇階級」(leisure class)としたT・ヴェブレンは、彼らの消費パターンの目的が実質的なものの消費にあるのではなく、他者に「見せびらかす消費=衒示的消費(げんじて きしょうひ)」 (conspicuous consumption)であるとした。20世紀末の日本の外車(とくにヨーロッパ車)の崇拝と購入などは、「質がよく安全性が高く、機能の充実した車」 であると消費者を煽るメディアの追い風にのった、ある種の見せびらかす消費といえよう。しかし、このようなひねくれた見方を取らなくても、現代の中産階級 は、その見せびらかしの程度は慎ましいもののさまざまな差異の記号――たとえばブランド品、家具調度、生活スタイルなど――をもって小さな見せびらかしの 消費そのものを実行している(→「エコ・ツーリストと熱帯生態学」)。

| ★In sociology and in

economics, the term conspicuous consumption describes and explains the

consumer practice of buying and using goods of a higher quality, price,

or in greater quantity than practical.[1] In 1899, the sociologist

Thorstein Veblen coined the term conspicuous consumption to explain the

spending of money on and the acquiring of luxury commodities (goods and

services) specifically as a public display of economic power—the income

and the accumulated wealth—of the buyer. To the conspicuous consumer,

the public display of discretionary income is an economic means of

either attaining or of maintaining a given social status.[2][3] The development of Veblen's sociology of conspicuous consumption also identified and described other economic behaviours such as invidious consumption, which is the ostentatious consumption of goods, an action meant to provoke the envy of other people; and conspicuous compassion, the ostentatious use of charity meant to enhance the reputation and social prestige of the donor;[4] thus the socio-economic practices of consumerism derive from conspicuous consumption.[5] |

社会学や経済学において、衒示的消費(げんじてきしょうひ)という用語

は、実用的なものよりも高い品質、価格、または大量の商品を購入し、使用する消費者の習慣を説明し、記述するものである[1]。1899年、社会学者ソー

スタイン・ヴェブレンは、特に買い手の経済力(収入や蓄積された富)を公に示すものとして、贅沢品(商品やサービス)への出費や取得を説明するために、目

立ちたがり屋消費という用語を作り出した。衒示的消費者にとって、裁量的な収入を公に示すことは、与えられた社会的地位を獲得する、あるいは維持するため

の経済的手段である[2][3]。 ヴェブレンの衒示的消費の社会学の発展は、他の人々の羨望を引き起こすことを意図した行為である商品の仰々しい消費であるinvidious consumptionや、寄付者の評判や社会的威信を高めることを意図したチャリティーの仰々しい使用であるconspicuous compassionといった他の経済行動も特定し、記述した[4]。 したがって、消費主義の社会経済的実践は、衒示的消費から派生している[5]。 |

| History and development In The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study in the Evolution of Institutions (1899), Thorstein Veblen identified, described, and explained the behavioural characteristics of the nouveau riche (new rich) social class that emerged from capital accumulation during the Second Industrial Revolution (1860–1914).[6] In that 19th-century social and historical context, the term "conspicuous consumption" applied narrowly in association with the men, women, and families of the upper class who applied their great wealth as a means of publicly manifesting their social power and prestige, either real or perceived. The strength of one's reputation is in direct relationship to the amount of money possessed and displayed; that is to say, the basis "of gaining and retaining a good name, are leisure and conspicuous consumption."[7] In the 1920s, economists such as Paul Nystrom proposed that changes in lifestyle as result of the industrial age led to massive expansion of the "pecuniary emulation."[8] That conspicuous consumption had induced in the mass of society a "philosophy of futility" that would increase the consumption of goods and services as a social fashion; consumption for the sake of consumption. In 1949, James Duesenberry proposed the "demonstration effect" and the "bandwagon effect", whereby a person's conspicuous consumption psychologically depends upon the actual level of spending, but also depends upon the degree of his or her spending, when compared with and to the spending of other people. That the conspicuous consumer is motivated by the importance, to him or to her, of the opinion of the social and economic reference groups for whom he or she are performed the conspicuous consumption.[9][10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspicuous_consumption |

歴史とその発展 『制度の進化に関する経済学的研究』(1899年)において、ソーシュタイン・ヴェブレンは、第二次産業革命(1860-1914年)の資本蓄積によって 生まれたヌーヴォー・リッチ(新富裕層)の社会階層の行動特性を特定し、記述し、説明した。19世紀の社会的・歴史的文脈では、"衒示的消費 "という言葉は、上流階級の男性、女性、家族が、その莫大な富を、現実のものであれ認識されているものであれ、社会的権力や威信を公に示す手段として適用 する、という狭い意味合いで使われていた。つまり、"良い評判を得、維持するための基本は、余暇と衒示的消費 "である。 1920年代、ポール・ナイストロムのような経済学者は、工業化時代の結果としてのライフスタイルの変化が、「金銭的エミュレーション」の大規模な拡大を もたらしたと提唱した。 衒示的消費は、社会の大衆に「無益の哲学」を誘発し、社会的ファッションとしての財やサービスの消費を増大させた。 1949 年、ジェームズ・デューセンベリーは「デモンストレーション効果」と「バンドワゴン効果」を提唱した、 そこでは衒示的消費は、心理的には実際の消費水準に依存するが、他の人の消費と比較したときのその人の消費の度合いにも依存する。 衒示的消費者は、自分が衒示的消費費を行っている社会的・経済的参照集団の意見が、自分にとって重要であることに突き動かされている。 |

| Social class and consumption Veblen said that conspicuous consumption comprised socio-economic behaviours practised by rich people as activities usual and exclusive to people with much disposable income;[8] yet a variation of Veblen's theory is presented in the conspicuous consumption behaviours that are very common to the middle class and to the working class, regardless of the person's race and ethnic group. Such upper-class economic behaviour is especially common in societies with emerging economies in which the conspicuous consumption of goods and services ostentatiously signals that the buyer rose from poverty and has something to prove to society.[11] In The Millionaire Next Door: The Surprising Secrets of America's Wealthy (1996), Thomas J. Stanley and William D. Danko reported conspicuous frugality, another variation of Veblen's social-class relation to conspicuous consumption. That Americans with a net worth of more than a million dollars usually avoid conspicuous consumption, and tend to practise frugality, such as paying cash for a used car rather using credit, in order to avoid material depreciation and paying interest upon a car loan.[12] |

社会階級と消費 ヴェブレンは、顕示的消費とは、富裕層が、可処分所得の多い人々に特有かつ日常的な活動として行う社会経済的行動であると述べた[8]。しかし、ヴェブレ ンの理論には、人種や民族に関係なく、中流階級や労働者階級に非常に一般的な顕示的消費行動というバリエーションがある。このような上流階級の経済行動 は、新興経済社会において特に一般的で、商品やサービスの目立つ消費が、購入者が貧困から脱却し、社会に対して何かを証明しようとしていることを派手に見 せつけるものとなっている。[11] 『The Millionaire Next Door: The Surprising Secrets of America's Wealthy』(1996年)の中で、トーマス・J・スタンレーとウィリアム・D・ダンコは、ヴェブレンの社会階級と顕示的消費の関係のもう一つのバリ エーションである、顕著な倹約について報告している。純資産が100万ドルを超えるアメリカ人は、目立つ消費を避け、中古車を購入する際はクレジットカー ドではなく現金で支払うなど、物質的な価値の低下や自動車ローンの利息支払いを避けるために倹約を実践する傾向がある。[12] |

| Consumerism theory Since the 19th century, conspicuous consumption explains the psychology behind the economics of a consumer society, and the increase in the types of goods and services that people consider necessary to and for their lives in a developed economy. Supporting interpretations and explanations of contemporary conspicuous consumption are presented in Consumer Culture (1996) by Celia Lury,[13] Consumer Culture and Modernity (1997) by Don Slater,[14] Symbolic Exchange and Death (1998) by Jean Baudrillard,[15] and Spent: Sex, Evolution, and the Secrets of Consumerism (2009) by Geoffrey Miller.[16] Moreover, D. Hebdige, in Hiding in the Light (1994), proposes that conspicuous consumption is a form of displaying a personal identity,[14][17][18] and a consequent function of advertising, as proposed in Ads, Fads, and Consumer Culture (2000), by A. A. Berger.[19] Each variant interpretation and complementary explanation is derived from Veblen's original sociologic proposition in The Theory of the Leisure Class: that conspicuous consumption is a psychological end in itself, from which the practitioner (man, woman, family) derived the honour of superior social status. |

消費主義理論 19 世紀以来、派手で贅沢な消費は、消費社会経済の裏にある心理、および先進経済社会において人々が生活に必要な、あるいは生活のために必要だと考える商品や サービスの種類の増加を説明する。現代の派手で贅沢な消費に関する解釈や説明は、セリア・ルリー著『Consumer Culture(1996 年)』、[13] ドン・スレーター『消費者文化と現代性』(1997年)、[14] ジャン・ボードリヤール『象徴的交換と死』(1998年)、[15] ジェフリー・ミラー『消費された:セックス、進化、そして消費主義の秘密』(2009年)で示されている。[16] さらに、D. ヘブディッジは『Hiding in the Light』(1994年)で、顕示的消費は個人のアイデンティティを誇示する一種の表現であり[14][17][18]、A. A. バーガーの『Ads, Fads, and Consumer Culture』(2000年)で提唱されているように、広告の副次的な機能であると主張している。[19] 各々の変種解釈と補足説明は、ヴェブレンの『レジャー階級の理論』における元の社会学的命題から導き出されている。すなわち、顕示的消費はそれ自体を目的 とする心理的行為であり、実践者(男性、女性、家族)はそこから優越的な社会的地位の栄誉を得るとする。 |

| Materialism and gender In An Examination of Materialism, Conspicuous Consumption and Gender Differences (2013), the researchers Brenda Segal and Jeffrey S. Podoshen reported great differences in the consumerism practised by men and women. The data about materialism and impulse purchases of 1,180 Americans indicate that men have greater scores for materialism and conspicuous consumption; and that women tended to buy goods and services on impulse; and both sexes were equally loyal to a given brand of goods and services.[20] |

物質主義と性別 物質主義、顕示的消費、および性差に関する調査(2013年)において、研究者ブレンダ・シーガルとジェフリー・ポドシェンは、男性と女性の間で消費行動 に大きな違いがあることを報告しています。1,180人のアメリカ人を対象にした物質主義と衝動買いに関するデータによると、男性は物質主義と顕示的消費 のスコアが高く、女性は衝動的に商品やサービスを購入する傾向があり、両性とも特定のブランドの商品やサービスに対する忠誠心は同程度だった。[20] |

| Distinctions of type The term conspicuous consumption denotes the act of buying something, especially something expensive, that is not necessary to one's life, in a noticeable way.[21] Scholar Andrew Trigg (2001) defined conspicuous consumption as behaviour by which one can display great wealth, by means of idleness—expending much time in the practice of leisure activities, and spending much money to consume luxury goods and services.[22] Conspicuous compassion, the practice of publicly donating large sums of money to charity to enhance the social prestige of the donor, is sometimes described as a type of conspicuous consumption.[4] This behaviour has long been recognised and sometimes attacked—for example, the New Testament story Lesson of the widow's mite criticises wealthy people who make large donations ostentatiously, while praising poorer people who make small but comparatively more difficult donations in private.[23] Possible motivations for conspicuous consumption include: Demonstration/bandwagon effect — In the book Income, Saving and the Theory of Consumer Behavior (1949), James Duesenberry proposed that a person's conspicuous consumption psychologically depends not only upon the actual level of spending, but also upon the degree of his or her spending, as compared with the spending of other people. Thus the conspicuous consumer is motivated by the importance, to him or to her, of the opinion of the social and economic reference groups for whom are performed the patterns of conspicuous consumption.[9][10] Aggressive ostentation — In a 2006 CBSNews.com article, Dick Meyer said that conspicuous consumption is a form of anger towards society, an "aggressive ostentation" that is an antisocial behaviour, which arose from the social alienation suffered by men, women, and families who feel they have become anonymous in and to their societies. This feeling of alienation is aggravated by the decay of the communitarian ethic essential to a person feeling him or herself part of the whole society.[24] Shelter and transport — In the United States, the trend towards building houses that were larger than needed by a nuclear family began in the 1950s. Decades later, in the year 2000, that practice of conspicuous consumption resulted in people buying houses that were double the average size needed to comfortably house a nuclear family.[25] Negative consequences of either buying or building an oversized house might include: the loss of or reduction in the family's domestic recreational space—the backyard and the front yard; the spending of old-age retirement funds to pay for a too-big house; over-long commuting time, from house to job, and vice versa, because the required plot of land was unavailable near a city. Oversized houses facilitated other forms of conspicuous consumption, such as an oversized garage for the family's oversized motor vehicles or buying more clothing to fill larger clothes closets. Conspicuous consumption becomes a self-generating cycle of spending money for the sake of social prestige. Analogous to the consumer trend for oversized houses is the trend towards buying oversized light trucks, specifically the off-road sport utility vehicle type (cf. station wagon/estate car), as a form of psychologically comforting conspicuous consumption, because such large vehicles usually are bought by city-dwellers, an urban nuclear family.[25] Prestige – In a 1999 article, Jacqueline Eastman, Ronald Goldsmith, and Leisa Reinecke Flynn said that status consumption is based upon conspicuous consumption; however, the literature of contemporary marketing does not establish definitive meanings for the terms status consumption and conspicuous consumption.[26][27] Moreover, A. O'Cass and H. Frost (2002) claim that sociologists often incorrectly used the two terms as interchangeable and equivalent terms. In a later study, O'Cass and Frost determined that, as sociological constructs, the terms status consumption and conspicuous consumption denote different sociological behaviours.[28] About the ambiguities of denotation and connotation of the term conspicuous consumption, R. Mason (1984) reported that the classical, general theories of consumer decision-processes do not readily accommodate the construct of "conspicuous consumption", because the nature of said socio-economic behaviours varies according to the social class and the economic group studied.[29] Motivations – Paurav Shukla (2010) says that, whilst marketing and sales researchers recognise the importance of the buyer's social and psychological environment, the definition of the term status-directed consumption remains ambiguous, because the development of a comprehensive general theory requires that social scientists accept two fundamental assumptions, which usually do not concord. First, though the "rational" (economic) and the "irrational" (psychologic) elements of consumer decision-making often influence a person's decision to buy particular goods and services, marketing and sales researchers usually consider the rational element dominant in a person's decision to buy the particular goods and services. Second, the consumer perceives the utility of the product (the goods, the services) as a prime consideration in evaluating its usefulness, i.e. the reason to buy the product.[30] These assumptions, required for the development of a general theory of brand selection and brand purchase, are problematic, because the resultant theories tend either to misunderstand or to ignore the "irrational" element in the behaviour of the buyer-as-consumer; and because conspicuous consumption is a behaviour predominantly "psychological" in motivation and expression, Therefore, a comprehensive, general theory of conspicuous consumption would require a separate construct for the psychological (irrational) elements of the socio-economic phenomenon that is conspicuous consumption. |

タイプの区別 「派手で贅沢な消費」という用語は、生活に必要なものではない、特に高価なものを、人目に付くように購入する行為を指す。[21]学者アンドルー・トリッ グ(2001)は、派手で贅沢な消費を、怠惰によって、つまり余暇活動に多くの時間を費やし、高級品やサービスの消費に多額の資金を使うことで、自分の富 を誇示する行動と定義している。[22] 目立つ慈善活動、つまり、寄付者の社会的威信を高めるために、慈善団体に多額の寄付を公に行う行為は、目立つ消費の一種と表現されることもある。[4] このような行動は、古くから認識されており、時には批判の対象にもなっている。例えば、新約聖書の「寡婦の献金」の物語では、多額の寄付を誇示して行う富 裕層を批判し、少額ながらも、比較的困難な寄付を人知れず行う貧しい人々を称賛している。[23] 顕示的消費の考えられる動機としては、次のようなものが挙げられる。 デモンストレーション/バンドワゴン効果 — ジェームズ・デューセンベリーは、著書『所得、貯蓄、消費者行動の理論』(1949 年)の中で、人の顕示的消費は、実際の支出額だけでなく、他の人々と比較した支出の程度にも心理的に依存すると提唱した。したがって、派手で贅沢な消費を する人は、その消費行動の対象となる社会的・経済的参照集団の意見が自分にとって重要であることから、その行動に動機付けられている[9][10]。 攻撃的な誇示 — 2006年のCBSNews.comの記事で、ディック・メイヤーは、顕示的消費は社会に対する怒りの表現であり、社会から疎外され、社会の中で自分が無 名になったと感じている男性、女性、家族によって生じる反社会的行動である「攻撃的な誇示」であると述べている。この疎外感は、自分が社会全体の一部であ ると感じるために不可欠な共同体倫理の衰退によってさらに悪化している。[24] 住居と交通 — 米国では、1950年代から、核家族が必要とする以上の広さの住宅を建設する傾向が見られた。その数十年後の 2000 年には、その派手で贅沢な消費行動の結果、核家族が快適に暮らすために必要な平均的な住宅面積の 2 倍もの広さの住宅を購入する人が現れました[25]。過大な住宅を購入または建設することの悪影響としては、次のようなものが挙げられます。 家族のためのレクリエーションスペース(裏庭や前庭)の喪失または減少 過大な住宅の購入資金に老後の退職金を使うこと 都市近郊に適切な土地が不足しているため、自宅と職場間の通勤時間が過度に長くなること。 過剰な住宅は、家族の過剰な自動車のための過剰なガレージや、より大きなクローゼットに合わせるための衣服の過剰な購入など、他の目立つ消費形態を促進し た。目立つ消費は、社会的地位のために金銭を費やす自己増殖的なサイクルとなる。過剰な住宅の消費傾向と類似する傾向として、心理的な安心感を得るための 目立つ消費として、特にオフロード型スポーツユーティリティビークル(ステーションワゴン/エステートカー参照)のような過剰なライトトラックの購入が挙 げられる。このような大型車両は通常、都市部の核家族によって購入される。[25] 威信 – 1999年の記事で、ジャクリーン・イーストマン、ロナルド・ゴールドスミス、レイサ・ラインケ・フリンは、ステータス消費は顕示的消費に基づいていると 述べた。しかし、現代のマーケティングの文献では、ステータス消費と顕示的消費という用語の明確な意味は確立されていない。[26][27] さらに、A. O『Cass と H. Frost (2002) は、社会学者たちはこの 2 つの用語を、しばしば誤って同義語、同義語として用いていると主張している。その後の研究で、O』Cass と Frost は、社会学的概念として、ステータス消費と顕示的消費という用語は、異なる社会学的行動を表すものと決定した。[28] 「顕示的消費」という用語の含意と意味の曖昧さについて、R. Mason (1984) は、消費者意思決定プロセスの古典的な一般理論は、「顕示的消費」という概念を容易に受け入れることができないと報告している。その理由は、この社会経済 的行動の性質は、研究対象とする社会階級や経済集団によって異なるためだ。[29] 動機 – パウラヴ・シュクラ(2010)は、マーケティングおよび販売の研究者は、購入者の社会的および心理的環境の重要性を認識しているものの、包括的な一般理 論の構築には、社会科学者が通常一致しない2つの基本的な仮定を受け入れる必要があるため、ステータス指向消費という用語の定義は依然として曖昧であると 述べている。まず、消費者の意思決定における「合理的」(経済的)要素と「非合理的」(心理的)要素は、特定の商品やサービスを購入する人格の決定にしば しば影響を与えるが、マーケティングおよび販売の研究者は通常、特定の商品やサービスを購入する人格の決定には合理的要素が支配的であると考える。第二 に、消費者は、製品の有用性(商品やサービス)を評価する際の主要な考慮事項として、その製品の有用性(購入する理由)を認識している。[30] これらの仮定は、ブランド選択とブランド購入の一般理論の構築に必要なものですが、問題があります。なぜなら、これらの仮定に基づく理論は、消費者の行動 における「非合理的な」要素を誤解したり無視したりする傾向があるからです。また、顕示的消費は、動機と表現の面で主に「心理的」な行動であるためです。 したがって、顕示的消費の包括的で一般的な理論を構築するには、顕示的消費という社会経済現象の心理的(非合理的な)要素を説明する別の概念が必要とな る。 |

| Examples Conspicuous consumption is exemplified by purchasing goods that are exclusively designed to serve as symbols of wealth, such as luxury-brand clothing, high-tech tools, and vehicles.[5] Luxury fashion Materialistic consumers are likely to engage in conspicuous luxury consumption.[31] The global yearly revenue of the luxury fashion industry was €1.64 trillion in 2019.[32] Buying of conspicuous goods is likely to be influenced by the spending habits of others. This view of luxury conspicuous consumption is being incorporated into social media platforms which is impacting consumer behaviour.[31] During periods of economic downturn, consumers tend to turn away from "logomania" products and instead purchase luxury goods that signal affluence more subtly.[33] |

例 顕示的消費の例としては、高級ブランドの衣類、ハイテク機器、自動車など、富の象徴としてのみ設計された商品の購入が挙げられる。[5] 高級ファッション 物質主義的な消費者は、顕示的な高級消費を行う傾向がある。[31] 2019年の高級ファッション業界の年間世界売上高は1兆6400億ユーロだった。[32] 目立つ商品の購入は、他者の消費習慣に影響される傾向がある。この贅沢な目立つ消費の観点は、ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームに取り入れられ、消費者 の行動に影響を与えている。[31] 経済不況期には、消費者は「ロゴマニア」製品から離れ、より控えめに富を象徴する高級品を購入する傾向がある。[33] |

| Criticism In 1919, the journalist H. L. Mencken addressed the sociological and psychological particulars of the socio-economic behaviours that are conspicuous consumption, by asking: Do I enjoy a decent bath because I know that John Smith cannot afford one—or because I delight in being clean? Do I admire Beethoven's Fifth Symphony because it is incomprehensible to Congressmen and Methodists—or because I genuinely love music? Do I prefer terrapin à la Maryland to fried liver because plowhands must put up with the liver—or because the terrapin is intrinsically a more charming dose? Do I prefer kissing a pretty girl to kissing a charwoman, because even a janitor may kiss a charwoman—or because the pretty girl looks better, smells better, and kisses better?[24][34] |

批判 1919年、ジャーナリストのH. L. メンケンは、顕著な消費という社会経済的行動の社会学的および心理学的特徴について、次のように問いかけました。 私は、ジョン・スミスにはその余裕がないことを知っているから、あるいは清潔であることを喜んでいるから、快適な風呂を楽しむのか?私は、連邦議会議員や メソジスト教徒には理解できないから、あるいは純粋に音楽が好きだから、ベートーベンの「第5交響曲」を賞賛するのか?私は、メリーランド風テラピンをフ ライドレバーよりも好むのは、農夫がレバーを食べなければならないからなのか——それともテラピンが本質的により魅力的な料理だからなのか?私は、美しい 女性とキスするのを、清掃婦とキスするよりも好むのは、清掃婦でもキスできるからなのか——それとも美しい女性がより美しく、より良い匂いがし、より良い キスをするからなのか?[24][34] |

| Inequality and debt In The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899) Veblen said that "among the motives which lead men to accumulate wealth, the primacy, both in scope and intensity, therefore, continues to belong to this motive of pecuniary emulation of the rich".[2] In the study "Borrowing to Keep Up (with the Joneses): Inequality, Debt, and Conspicuous Consumption" (2020), Sheheryar Banuri and Ha Nguyen reported three findings: Consumption tends to increase when the buying and the using of goods and services is conspicuous: Consumption signals status to other people. Conspicuous consumption increases the frequency of borrowing money: Poor people take out loans in order to compete at consumption. Economic inequality is worsened with access to credit: Poor people borrow money in order to signal status, which becomes a vicious circle.[35] The findings that Banuri and Nguyen reported indicate that the cyclical effect of borrowing money for conspicuous consumption leads to and perpetuates economic inequality. That poor people imitate, try to match, and emulate the consumption patterns of rich people in order to increase their social status, and perhaps rise in society. That such socio-economic behaviours, facilitated by easy access to credit, generate macroeconomic volatility and support Veblen's concept of pecuniary emulation used to finance a person's social standing.[35] Other research supports these and similar results. For example income inequality has been found to be associated with reduced savings rates.[36][37][38] One hypothesized mechanism for this relationship is 'expenditure cascades'[39] whereby consumption norms are set by the relatively wealthy, who then have more income and consumption relative to others as inequality rises. This emulation of the consumption norms of relatively wealthy peers is supported by a large literature.[40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47] One complication found in the macro literature is that the link between inequality and savings may depend on context, in particular on the degree of financialisation. When the degree of financialisation is high, inequality tends to reduce the national savings rate as the emulation effect is more powerful when finance is readily available, but the opposite effect may occur when financialisation is low as the emulation effect is weak, and the rich tend to save at a higher rate than the poor.[48] The effect of inequality on savings is also found to be positive in Asia, where financialization is lower.[49][50] The relationship is also found to depend on economic policy and institutions. For example inequality appears to lower savings in market economies but to rather reduce aggregate demand in planned economies.[51] In the case where inequality lowers savings, and increases leverage and a tendency to run large current account imbalances via the expenditure cascade mechanism, this has been associated with more frequent and/or severe economic crisis.[52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59] |

不平等と債務 『レジャー階級論』(1899年)の中で、ヴェブレンは「人間が富を蓄積する動機の中で、その範囲と強度の両面で、依然として最も重要なのは、富裕層への 金銭的な模倣という動機である」と述べている。[2] 「Borrowing to Keep Up (with the Joneses): 不平等、債務、および派手で贅沢な消費」 (2020) で、シェヘヤール・バヌリとハ・グエンは 3 つの発見を報告している。 商品やサービスの購入や使用が目立つ場合、消費は増加する傾向がある。消費は他の人々に自分のステータスを示す。 派手で贅沢な消費は、借金の頻度を高める。貧しい人々は、消費競争に打ち勝つためにローンを組む。 経済的不平等は、クレジットの利用によって悪化する:貧しい人々は、自分のステータスを示すために借金をし、それが悪循環になる。 Banuri と Nguyen が報告した調査結果は、見栄を張るための借金による循環的な影響が、経済的不平等を引き起こし、それを永続させていることを示している。貧しい人々は、社 会的地位を高め、おそらくは社会で上昇するために、富裕層の消費パターンを模倣し、それに追いつこうとし、真似をする。このような社会経済的行動は、クレ ジットの容易な利用によって促進され、マクロ経済の不安定さを生じさせ、個人の社会的地位の維持のために資金を提供する、ヴェブレンの「金銭的模倣」の概 念を裏付けるものとなっている[35]。 他の研究も、これらの結果や同様の結果を裏付けている。例えば、所得の不平等は貯蓄率の低下と関連していることが明らかになっている[36][37]。 [38] この関係の一つの仮説的なメカニズムは「支出の連鎖」[39]で、相対的に裕福な層が消費規範を設定し、不平等が拡大するにつれ、彼らは他者よりも収入と 消費が増加する。この相対的に裕福な同輩の消費規範の模倣は、多くの研究で支持されている。[40][41][42][43][44][45][46] [47] マクロ経済学の文献で指摘されている複雑な問題の一つは、不平等と貯蓄の関係は、状況、特に金融化の程度によって異なる可能性があるということだ。金融化 の程度が高い場合、金融が利用しやすい状況では模倣効果が強いため、不平等は国民貯蓄率を低下させる傾向がある。しかし、金融化の程度が低い場合、模倣効 果が弱いため、逆の現象が起こり、富裕層は貧困層よりも貯蓄率が高くなる傾向がある。[48] 格差が貯蓄に与える影響は、金融化が低いアジアでも正の関連性が確認されている。[49][50] この関係は経済政策や制度にも依存する。例えば、市場経済では格差が貯蓄を低下させるが、計画経済ではむしろ総需要を減少させる傾向がある。[51] 不平等が貯蓄を減らし、支出カスケードメカニズムを通じてレバレッジと大きな経常収支の不均衡の傾向を高める場合、これはより頻繁かつ/または深刻な経済危機と関連している。[52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59] |

| Solutions In the case of conspicuous consumption, taxes upon luxury goods diminish societal expenditures on high-status goods, by rendering them more expensive than non-positional goods. In this sense, luxury taxes can be seen as a Pigouvian tax correcting market failure—with an apparent negative deadweight loss, these taxes are a more efficient mechanism for increasing revenue than 'distorting' labour or capital taxes.[60] A luxury tax applied to goods and services for conspicuous consumption is a type of progressive sales tax that at least partially corrects the negative externality associated with the conspicuous consumption of positional goods.[61] In Utility from Accumulation (2009), Louis Kaplow said that assets exercise an objective social-utility function, i.e. the rich man and the rich woman hoard material assets, because the hoard, itself, functions as status goods that establish his and her socio-economic position within society.[62] When utility is derived directly from accumulation of assets, this lowers the dead weight loss associated with inheritance taxes and raises the optimal rate of inheritance taxation.[63]  In the 19th century, the philosopher John Stuart Mill recommended taxing the practice of conspicuous consumption. In place of luxury taxes, economist Robert H. Frank proposed the application of a progressive consumption tax; in a 1998 New York Times article, John Tierney said that as a remedy for the social and psychological malaise that is conspicuous consumption, the personal income tax should be replaced with a progressive tax upon the yearly sum of discretionary income spent on the conspicuous consumption of goods and services.[64] Another option is the redistribution of wealth, either by means of an incomes policy – for example the conscious efforts to promote wage compression under variants of social corporatism such as the Rehn–Meidner model and/or by some mix of progressive taxation and transfer policies, and provision of public goods. When individuals are concerned with their relative income or consumption in comparison to their peers, the optimal degree of public good provision and of progression of the tax system is raised.[65][66][67] Because the activity of conspicuous consumption, itself, is a form of superior good, diminishing the income inequality of the income distribution by way of an egalitarian policy reduces the conspicuous consumption of positional goods and services. In Wealth and Welfare (1912), the economist A. C. Pigou said that the redistribution of wealth might lead to great gains in social welfare: Now the part played by comparative, as distinguished from absolute, income is likely to be small for incomes that only suffice to provide the necessaries and primary comforts of life, but to be large with large incomes. In other words, a larger proportion of the satisfaction yielded by the incomes of rich people comes from their relative, rather than from their absolute, amount. This part of it will not be destroyed if the incomes of all rich people are diminished together. The loss of economic welfare suffered by the rich when command over resources is transferred from them to the poor will, therefore, be substantially smaller relatively to the gain of economic welfare to the poor than a consideration of the law of diminishing utility taken by itself suggests.[68] The economic case for the taxation of positional, luxury goods has a long history; in the mid-19th century, in Principles of Political Economy with some of their Applications to Social Philosophy (1848), John Stuart Mill said: I disclaim all asceticism, and by no means wish to see discouraged, either by law or opinion, any indulgence which is sought from a genuine inclination for, any enjoyment of, the thing itself; but a great portion of the expenses of the higher and middle classes in most countries ... is not incurred for the sake of the pleasure afforded by the things on which the money is spent, but from regard to opinion, and an idea that certain expenses are expected from them, as an appendage of station; and I cannot but think that expenditure of this sort is a most desirable subject of taxation. If taxation discourages it, some good is done, and if not, no harm; for in so far as taxes are levied on things which are desired and possessed from motives of this description, nobody is the worse for them. When a thing is bought not for its use but for its costliness, cheapness is no recommendation.[69] In the case where conspicuous consumption mediates a link between inequality and unsustainable borrowing, one suggested policy response is tighter financial regulation.[70][71] "Conspicuous non-consumption" is a phrase used to describe a conscious choice to opt out of consumption with the intention of sending deliberate social signals.[72][73] |

解決策 顕著な消費の場合、高級品に対する課税は、それらを非地位財よりも高価にすることで、高地位財に対する社会的支出を減少させる。この点で、贅沢品税は市場 失敗を是正するピグー税と見なすことができる。明らかな負の死重損失を伴うこれらの税は、労働や資本を歪める税よりも、歳入を増やすためのより効率的なメ カニズムだ。[60] 顕示的消費の対象となる商品やサービスに課される贅沢品税は、地位財の顕示的消費に関連する負の外部性を少なくとも一部是正する累進的な消費税の一種だ。 [61] 『蓄積からの効用』(2009年)の中で、ルイス・カプロウは、資産は客観的な社会的効用機能を発揮すると述べている。つまり、富裕層は、その蓄積自体が 社会における自分の社会経済的地位を確立するステータスグッズとして機能するため、物質的な資産を蓄積するのだ。[62] 効用が資産の蓄積から直接得られる場合、相続税に伴う死重損失は減少し、相続税の最適税率は上昇する。  19 世紀、哲学者ジョン・スチュワート・ミルは、顕示的消費に課税することを推奨した。 贅沢税に代わるものとして、経済学者ロバート・H・フランクは累進消費税の適用を提案した。1998年のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の記事で、ジョン・ティ アニーは、派手で贅沢な消費という社会的・心理的な不健全な現象の解決策として、個人所得税を、派手で贅沢な消費に費やされる年間可処分所得の額に課され る累進課税に置き換えるべきだと述べた。[64] もう一つの選択肢は、所得政策、例えば、レン・メイドナー・モデルなどの社会コーポラティズムの変種の下での賃金抑制の意識的な推進、および/または累進 課税と移転政策、公共財の提供の何らかの組み合わせによる富の再分配だ。個人が同世代と比較した相対的な収入や消費に関心を持つ場合、公共財の提供と税制 の累進性の最適な程度は高まる。[65][66][67] 目立つ消費活動そのものが上位財の一種であるため、平等主義政策により所得分配の格差を縮小すると、地位財やサービスの目立つ消費が減少する。経済学者 A.C.ピグーは『富と福祉』(1912年)で、財の再分配が社会福祉に大きな利益をもたらす可能性があると指摘している: 絶対的な所得とは区別される比較的な所得が果たす役割は、生活必需品や基本的な快適さを提供するために必要なだけの所得では小さいが、高所得では大きくな る傾向がある。つまり、富裕層の所得がもたらす満足の大部分は、その絶対的な額よりも相対的な額によるものなのだ。この部分は、富裕層全員の所得が同時に 減少しても失われることはない。したがって、資源の支配権が富裕層から貧困層に移転された場合に富裕層が被る経済的福祉の損失は、効用の逓減の法則だけを 考えるよりも、貧困層の経済的福祉の利益に比べてかなり小さくなるだろう。[68] 地位的、贅沢な物品に課税する経済的な根拠は長い歴史がある。19 世紀半ば、ジョン・スチュワート・ミルは『政治経済学の原理とその社会哲学への応用』(1848 年)の中で、次のように述べている。 私は、禁欲主義を一切否定し、法律や世論によって、その物自体に対する純粋な嗜好や楽しみから生じるあらゆる快楽の追求を妨げることを決して望んでいな い。しかし、ほとんどの国の高・中流階級の支出の大部分は... そのお金が費やされるものから得られる喜びのためではなく、世間の意見や、その立場にふさわしい支出であるとの考えから生じている。私は、この種の支出は 課税の対象として最も望ましいと考えるほかはない。課税がこれを抑制すれば、何らかの利益が生じ、抑制されなければ害はない。なぜなら、このような動機か ら望まれ、所有されるものに課税される限り、誰も不利益を被らないからである。物がその用途ではなく、その高価さのために購入される場合、安価さは推奨事 項ではない。[69] 顕著な消費が、不平等と持続不可能な借入との関連を仲介する場合、提案されている政策対応の一つは、金融規制の強化だ。[70][71] 「顕著な非消費」とは、意図的な社会的シグナルを送ることを目的として、消費を意図的に回避する選択を表す言葉だ。[72][73] |

| Affluenza Anti-consumerism Bling Class consciousness Commodity fetishism Conspicuous conservation Conspicuous leisure Costly signaling theory in evolutionary psychology Elitism Frugality Giffen good Handicap principle Haul video Hoarding Izikhothane Keeping up with the Joneses Materialism Mottainai Post-purchase rationalization Potlatch Prestige pricing Sign value Signalling theory Simple living Status symbol Structural functionalism Sumptuary law Sumptuary taxes Surplus economics Veblen good |

アフルエンザ 反消費主義 ブリング 階級意識 商品崇拝 目立つための節約 目立つための余暇 進化心理学における高価なシグナリング理論 エリート主義 倹約 ギッフェン財 ハンディキャップ原理 haul ビデオ 貯め込み イジコタネ 隣人競争 物質主義 もったいない 購入後の合理化 ポトラッチ ステータス価格 記号価値 シグナリング理論 シンプルな生活 ステータスシンボル 構造機能主義 奢侈禁止法 奢侈税 余剰経済学 ヴェブレン財 |

| Thorstein Veblen (1899). Theory of the Leisure Class at Project Gutenberg Thorstein Veblen: Conspicuous Consumption, 1902 at Fordham University's "Modern History Sourcebook" The Good Life: An International Perspective, a short article by Amitai Etzioni |

ソーシュタイン・ヴェブレン(1899)。プロジェクト・グーテンベルク『レジャー階級の理論 ソーシュタイン・ヴェブレン:1902年、フォードハム大学の「現代史資料集」に掲載された「顕示的消費 良い人生:国際的視点、アミタイ・エツィオーニによる短編記事 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspicuous_consumption |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099