さんかのがいねん, the concept of participation

参加の概念

さんかのがいねん, the concept of participation

「報道であれ、広告であれ、高尚な芸術で あれ、現代の コミュニケーションの傾向は、概念の理解よりも、過程に参加する方向に向かっている」。 (p.86)マクルーハンとジングローン編『エッセンシャル・マクルーハン』有馬哲夫訳、NTT 出版、2007年

参加(participation)と

は、学習者が実践を生

成する過程であると同時に実践共同体に関わる環境の変化についての過

程のことである。したがって、参加

は、学習者の技能と知識の変化、周りの外部環境との学

習者との関係の変化、学習者自身の自己理解(内部環境)の変化から分析される。——池田光穂(1999)出典:「実践共同体・基礎用語・定義集」

***

現場力研究において「参加」は重要な概念 のひとつである。参加と聞くと、ふつうはレイブとウェンガーが提唱した「正統的周辺参加」の 理論が気がかりになる。しかし、参加は日常語であり、その理論に呪縛される必 要はない。ここで私は、参加を次の3つの視点から考えてみよう。すなわち(1)参加の様態、(2)参加がもつ強度、(3)参加による効果、である。

まず参加の様態を明確にしよう。「お前は 参加していない」という先輩(上司や教授)の叱責に後輩(部下や院生)が反発するように、ある社会活動 に参加しているとしても「何をもって参加しているのか」という意識は、参与者のあいだで多様な広がりをもつ。それは後輩の反発を受けた先輩が言う「君たち は意見を言うだけで活動に関わっていない」という反論が空虚に感じられるように、言葉をもって正確に表現することも難しい。にも関わらず、参与者たちが置 かれた状況(つまり現場)に即して、何をもって参加とみなすのかという点を明確にしなければ、議論は焦点をもたず迷子になってしまう。

実践共

同体における参加の概念/ Pie chart showing the proportion of lurkers, contributors and creators under the 90–9–1 principle

次に着目すべきは、参加がもつ強度(つよ さ)である。もちろん、それはさまざまな社会活動を数値化したりやチェックポイントの個数で計測するこ とではない。参加の様態に関して、参与者たちが先の定義に一定の合意を示したならば、「はたしてどういうことが〈よく〉参加していると言えるのだろうか」 という議論が必要になろう。参加してからの時間経過、参与者間の関わりあい、本人および他人の評価、分業の有無、参加の場にみられる権力関係など、さまざ まな要素が、「参加の強度」に関連づけられて説明されることに気づくはずである。

最後は、参加による効果である。人が集団 で活動している時には、その活動の理由が参与者によって充分に自覚され明確に語られる場合がある。他方 で、他者の眼からみると十全に参加している人じしんが「私は十分に参加していない」と表明して周囲の人が驚くことがある。つまり参加の効果をめぐり、その 評価に個人差があるということだ。しかし参加を通して、人は何らかの変化、つまり参加の効果を感じているのも確かである。参加による効果も、集団全体に対 してと、参与者個々人に対しては、それぞれ異なる場合もある。活動の時間軸の長短や周期性をみて、変化があるかどうかも、参加の効果を説明する重要な観点 になる。

現代生活において参加の重要性が叫ばれて

久しい。しかし、参加の基本的な定義と、参加概念が我々の日常生活にもたらすものについて、上のように

自問すれば明らかなように、我々は必ずしも「参加」の意識を明確にもって行動しているわけではない。現場から「参加」を問い直すこととは、参与者が自分じ

しんで、ないしは対話を通して集団で、その都度、それらの問題に解答を与えていく行為である。そう考えると「参加」の概念の自己再帰的な検討は、まさに現場力の源泉であるとも言える。

現場における「参加」が、これまでの人文 社会学においてどのように研究されてきたかについては、拙稿(池田光穂)の「参加の理論」 を参照してください。

★日本のバリアフリーの法的根拠は主に

「高齢者、障害者等の移動等の円滑化の促進に関する法律(バリアフリー法)」であり2006年に施行

バ

リアフリーの発想は、障害者が日本の交通という文脈の中に参加するという、《社会的参加の平等》という理念を実現するために施行されたと解釈することがで

きる。

| In Internet culture, the 1% rule is

a general rule of thumb pertaining to participation in an Internet

community, stating that only 1% of the users of a website actively

create new content, while the other 99% of the participants only lurk.

Variants include the 1–9–90 rule (sometimes 90–9–1 principle or the

89:10:1 ratio),[1] which states that in a collaborative website such as

a wiki, 90% of the participants of a community only consume content, 9%

of the participants change or update content, and 1% of the

participants add content. Similar rules are known in information science; for instance, the 80/20 rule known as the Pareto principle states that 20 percent of a group will produce 80 percent of the activity, regardless of how the activity is defined. |

インターネット文化において、1%ルールとはインターネットコミュニ

ティへの参加に関する一般的な経験則である。これは、ウェブサイトのユーザーのわずか1%だけが積極的に新しいコンテンツを作成し、残りの99%の参加者

はただ閲覧しているだけだと述べている。変種として1-9-90ルール(90-9-1原則や89:10:1比率とも呼ばれる)[1]があり、ウィキのよう

な共同編集サイトでは、参加者の90%がコンテンツを消費するだけで、9%がコンテンツを変更・更新し、1%が新規コンテンツを追加するとされる。 情報科学においても類似の法則が知られている。例えば、パレートの法則として知られる80/20の法則は、活動の内容に関わらず、集団の20%が活動の80%を生み出すと述べている。 |

| Definition and review According to the 1% rule, about 1% of Internet users create content, while 99% are just consumers of that content. For example, for every person who posts on a forum, generally about 99 other people view that forum but do not post. The term was coined by authors and bloggers Ben McConnell and Jackie Huba,[2] although there were earlier references this concept[3] that did not use the name. The terms lurk and lurking, in reference to online activity, are used to refer to online observation without engaging others in the Internet community.[4] A 2007 study of radical jihadist Internet forums found 87% of users had never posted on the forums, 13% had posted at least once, 5% had posted 50 or more times, and only 1% had posted 500 or more times.[5] A 2014 peer-reviewed paper entitled "The 1% Rule in Four Digital Health Social Networks: An Observational Study" empirically examined the 1% rule in health-oriented online forums. The paper concluded that the 1% rule was consistent across the four support groups, with a handful of "Superusers" generating the vast majority of content.[6] A study later that year, from a separate group of researchers, replicated the 2014 van Mierlo study in an online forum for depression.[7] Results indicated that the distribution frequency of the 1% rule fit followed Zipf's law, which is a specific type of power law. The "90–9–1" version of this rule states that for websites where users can both create and edit content, 1% of people create content, 9% edit or modify that content, and 90% view the content without contributing. However, the actual percentage is likely to vary depending upon the subject. For example, if a forum requires content submissions as a condition of entry, the percentage of people who participate will probably be significantly higher than 1%, but the content producers will still be a minority of users. This is validated in a study conducted by Michael Wu, who uses economics techniques to analyze the participation inequality across hundreds of communities segmented by industry, audience type, and community focus.[8] The 1% rule is often misunderstood to apply to the Internet in general, but it applies more specifically to any given Internet community. It is for this reason that one can see evidence for the 1% principle on many websites, but aggregated together one can see a different distribution. This latter distribution is still unknown and likely to shift, but various researchers and pundits have speculated on how to characterize the sum total of participation. Research in late 2012 suggested that only 23% of the population (rather than 90%) could properly be classified as lurkers, while 17% of the population could be classified as intense contributors of content.[9] Several years prior, results were reported on a sample of students from Chicago where 60% of the sample created content in some form.[10] |

定義と考察 1%の法則によれば、インターネットユーザーの約1%がコンテンツを作成し、99%はそのコンテンツの消費者である。例えば、フォーラムに投稿する人格1 人につき、通常99人がそのフォーラムを閲覧するが投稿はしない。この用語は作家兼ブロガーのベン・マッコンネルとジャッキー・ヒューバによって提唱され た[2]が、名称を用いずにこの概念に言及した先行研究も存在する[3]。 オンライン活動における「潜伏(lurk)」や「潜伏行為(lurking)」という用語は、インターネットコミュニティ内で他者と関わりを持たずに観察する行為を指す[4]。 2007年の過激派ジハード主義インターネットフォーラム調査では、ユーザーの87%がフォーラムに一度も投稿したことがなく、13%が少なくとも1回は投稿し、5%が50回以上投稿し、わずか1%が500回以上投稿していた。[5] 2014年の査読付き論文「4つのデジタル健康ソーシャルネットワークにおける1%ルール:観察研究」は、健康志向のオンラインフォーラムにおける1% ルールを実証的に検証した。論文は、4つの支援グループすべてで1%ルールが成立し、ごく少数の「スーパーユーザー」がコンテンツの大部分を生産している と結論づけた。[6] 同年後半に別の研究者グループが実施した研究では、うつ病向けオンラインフォーラムにおいて2014年のファン・ミールロ研究を再現した。[7] その結果、1%ルールの分布頻度はジップの法則(特定のべき乗則)に従うことが示された。 この法則の「90-9-1」版は、ユーザーがコンテンツの作成と編集の両方が可能なウェブサイトにおいて、1%の人がコンテンツを作成し、9%がそのコン テンツを編集または修正し、90%は貢献せずにコンテンツを閲覧すると述べている。ただし、実際の割合は主題によって異なる可能性が高い。例えば、フォー ラムへの参加条件としてコンテンツ投稿を義務付ける場合、参加者の割合は1%より大幅に高くなるが、コンテンツ作成者は依然として少数派である。この点は マイケル・ウーの研究で実証されている。彼は経済学的手法を用いて、業界・対象読者層・コミュニティの焦点を基準に分類した数百のコミュニティにおける参 加格差を分析した。[8] 1%ルールはインターネット全体に適用されるものと誤解されがちだが、実際には特定のインターネットコミュニティに限定される。このため多くのサイトで 1%原則の証拠は確認できるが、それらを集計すると異なる分布が浮かび上がる。後者の分布は未だ不明で変動する可能性もあるが、様々な研究者や評論家が参 加の総量をどう特徴付けるかについて推測を重ねている。2012年末の研究によれば、人口の23%(90%ではなく)のみが「閲覧者」として適切に分類さ れ、17%が「コンテンツの積極的投稿者」に分類された[9]。数年前にはシカゴの学生サンプル調査で、60%が何らかの形でコンテンツを作成していたと 報告されている[10]。 |

| Participation inequality Main article: Participation inequality A similar concept was introduced by Will Hill of AT&T Laboratories[11] and later cited by Jakob Nielsen; this was the earliest known reference to the term "participation inequality" in an online context.[12] The term regained public attention in 2006 when it was used in a strictly quantitative context within a blog entry on the topic of marketing.[2] |

参加の不平等 詳細な記事: 参加の不平等 AT&T研究所のウィル・ヒル[11]によって類似の概念が提唱され、後にヤコブ・ニールセンによって引用された。これがオンライン環境における 「参加の不平等」という用語の最も古い知られている言及である[12]。この用語は2006年、マーケティングに関するブログ記事内で厳密に定量的な文脈 で使用されたことで再び注目を集めた[2]。 |

| Digital citizen Internet culture List of Internet phenomena Lotka's law Netocracy Silent majority Sturgeon's law User-generated content |

デジタル市民 インターネット文化 インターネット現象一覧 ロットカの法則 ネットクラシー 沈黙の多数派 スタージョンの法則 ユーザー生成コンテンツ |

| References 1. Arthur, Charles (20 July 2006). "What is the 1% rule?". The Guardian. 2. McConnell, Ben; Huba, Jackie (May 3, 2006). "The 1% Rule: Charting citizen participation". Church of the Customer Blog. Archived from the original on 11 May 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-10. 3. Horowitz, Bradley (February 16, 2006). "Creators, Synthesizers, and Consumers". Elatable. Blogger. Retrieved 2010-07-10. 4. "What is Lurking? – Definition from Techopedia". Techopedia.com. Retrieved 2019-11-05. 5. Awan, A. N. (2007). "Virtual Jihadist media: Function, legitimacy, and radicalising efficacy" (PDF). European Journal of Cultural Studies. 10 (3): 389–408. doi:10.1177/1367549407079713. S2CID 140454270. 6. van Mierlo, T. (2014). "The 1% Rule in Four Digital Health Social Networks: An Observational Study". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 16 (2): e33. doi:10.2196/jmir.2966. PMC 3939180. PMID 24496109. 7. Carron-Arthur, B; Cunningham, JA; Griffiths, KM (2014). "Describing the distribution of engagement in an Internet support group by post frequency: A comparison of the 90–9–1 Principle and Zipf's Law". Internet Interventions. 1 (4): 165–168. doi:10.1016/j.invent.2014.09.003. hdl:1885/22422. 8. Wu, Michael (April 1, 2010). "The Economics of 90–9–1: The Gini Coefficient (with Cross Sectional Analyses)". Lithosphere Community. Lithium Technologies, Inc. Retrieved 2010-07-10. 9. "BBC Online Briefing Spring 2012: The Participation Choice". 10. Hargittai, E; Walejko, G. (2008). "The Participation Divide: Content creation and sharing in the digital age". Information, Communication & Society. 11 (2): 389–408. doi:10.1080/13691180801946150. S2CID 4650775. 11. Hill, William C.; Hollan, James D.; Wroblewski, Dave; McCandless, Tim (1992). "Edit wear and read wear". Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems - CHI '92. ACM. pp. 3–9. doi:10.1145/142750.142751. ISBN 978-0-89791-513-7. S2CID 15416019. 12. Nielsen, Jakob (15 Aug 1997). "Community is Dead; Long Live Mega-Collaboration (Alertbox)". useit.com. Archived from the original on 28 Jan 1998. Retrieved 9 June 2022. |

参考文献 1. アーサー、チャールズ (2006年7月20日)。「1%の法則とは何か?」。ガーディアン紙。 2. マコーネル、ベン;フバ、ジャッキー (2006年5月3日)。「1%の法則:市民参加のチャート化」。顧客教会ブログ。2010年5月11日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2010年7月10日取得。 3. ホロウィッツ、ブラッドリー(2006年2月16日)。「クリエイター、シンセサイザー、そして消費者」。Elatable。Blogger。2010年7月10日取得。 4. 「潜伏とは?– Techopedia の定義」。Techopedia.com。2019年11月5日取得。 5. Awan, A. N. (2007). 「仮想ジハード主義者メディア:機能、正当性、および過激化の有効性」 (PDF). European Journal of Cultural Studies. 10 (3): 389–408. doi:10.1177/1367549407079713. S2CID 140454270. 6. van Mierlo, T. (2014). 「4つのデジタル健康ソーシャルネットワークにおける1%ルール:観察研究」. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 16 (2): e33. doi:10.2196/jmir.2966. PMC 3939180. PMID 24496109. 7. Carron-Arthur, B; Cunningham, JA; Griffiths, KM (2014). 「投稿頻度によるインターネット支援グループへの関与の分布の説明:90-9-1 の法則とジップの法則の比較」。インターネット介入。1 (4): 165–168. doi:10.1016/j.invent.2014.09.003. hdl:1885/22422. 8. Wu, Michael (2010年4月1日). 「90-9-1の経済学:ジニ係数(横断的分析を含む)」. Lithosphere Community. Lithium Technologies, Inc. 2010年7月10日閲覧. 9. 「BBCオンラインブリーフィング2012年春:参加の選択」. 10. Hargittai, E; Walejko, G. (2008). 「参加の格差:デジタル時代におけるコンテンツの創作と共有」. Information, Communication & Society. 11 (2): 389–408. doi:10.1080/13691180801946150. S2CID 4650775. 11. Hill, William C.; Hollan, James D.; Wroblewski, Dave; McCandless, Tim (1992). 「編集疲労と読解疲労」. コンピュータシステムにおける人間工学に関するSIGCHI会議論文集 - CHI '92. ACM. pp. 3–9. doi:10.1145/142750.142751. ISBN 978-0-89791-513-7. S2CID 15416019. 12. Nielsen, Jakob (1997年8月15日). 「コミュニティは死んだ。メガコラボレーション万歳 (Alertbox)」. useit.com. 1998年1月28日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2022年6月9日に閲覧. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1%25_rule |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

winndow for communication-design, picture taken by Mitzub'ixi

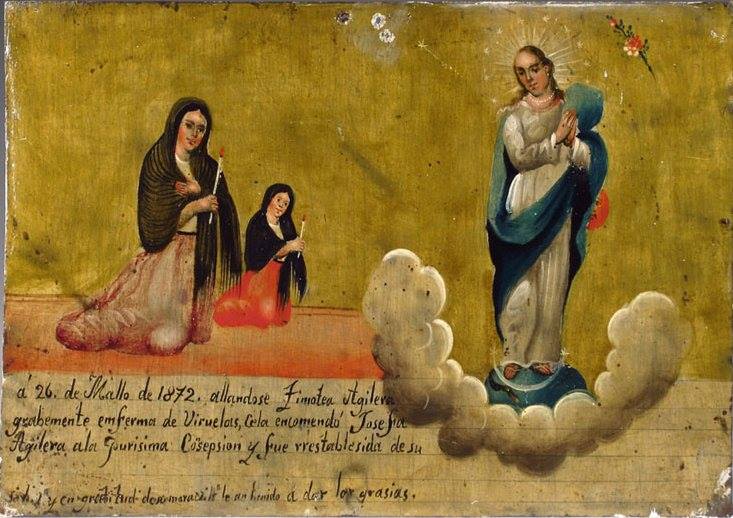

Ex-voto painting, 1872, Mexico.

"An ex-voto is a votive offering to a saint or to a divinity. It is given in fulfillment of a vow (hence the Latin term, short for ex voto suscepto, "from the vow made") or in gratitude or devotion. Ex-votos are placed in a church or chapel where the worshiper seeks grace or wishes to give thanks. The destinations of pilgrimages often include shrines decorated with ex-votos."Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099