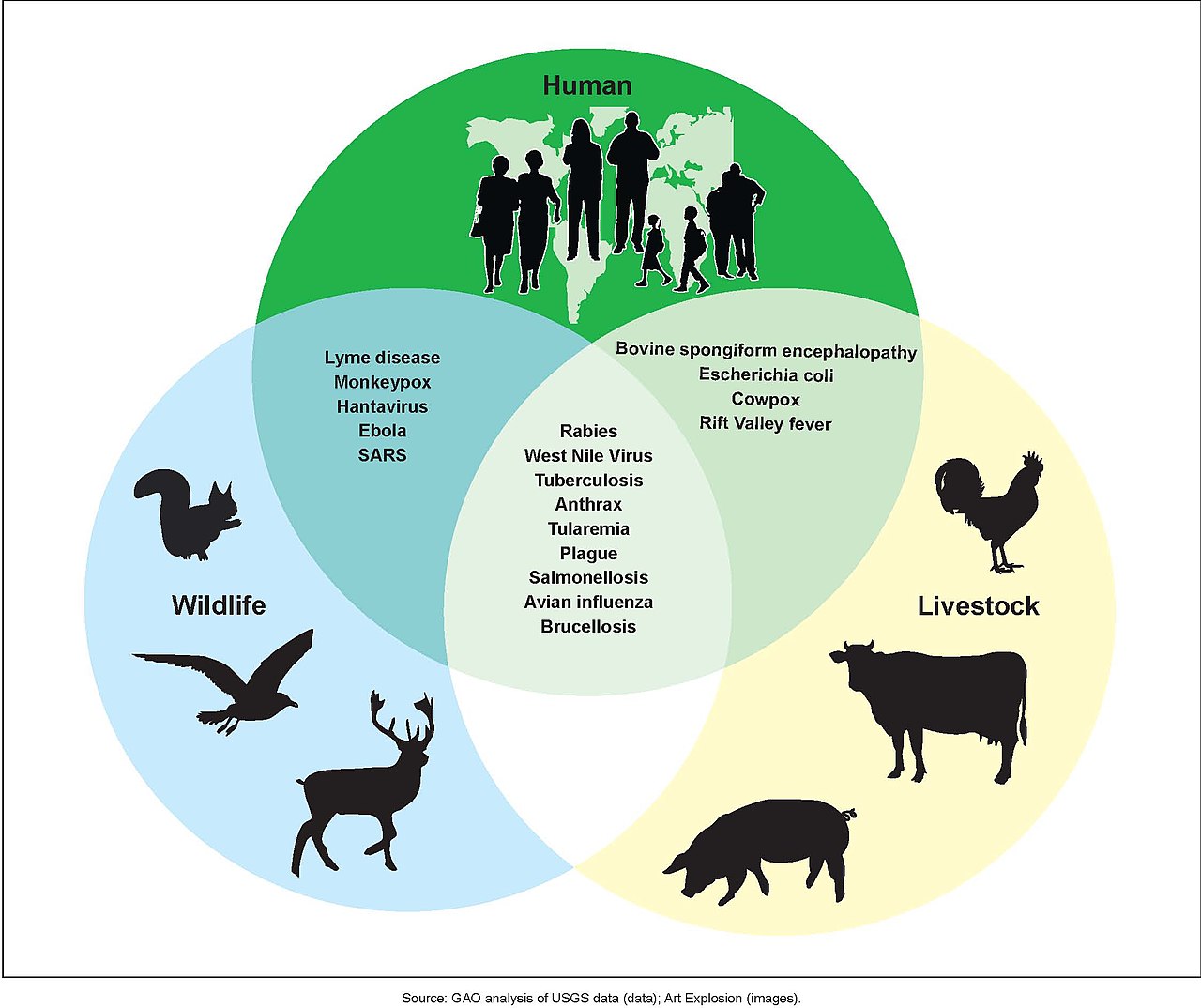

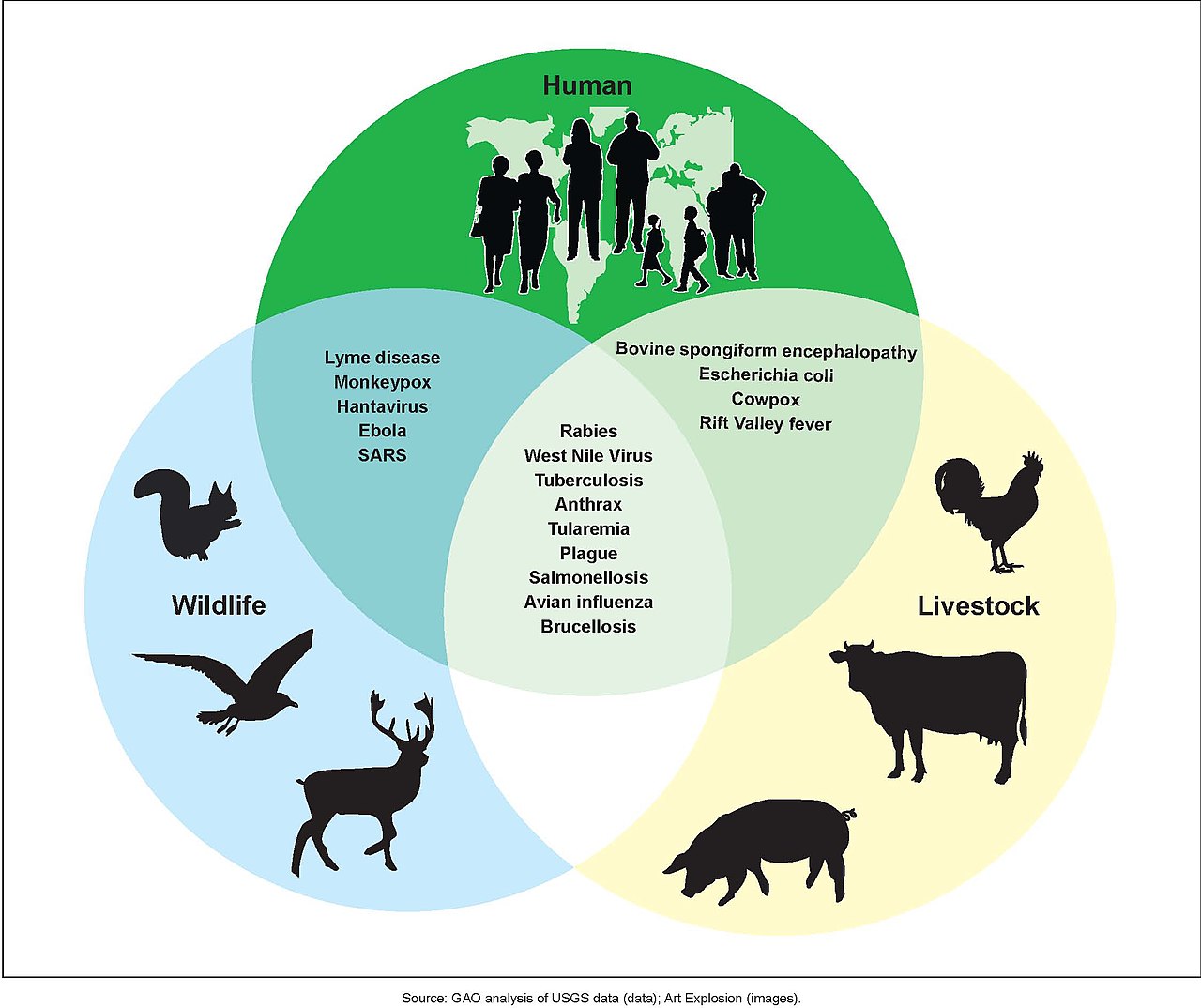

人獣共通感染症

Zoonosis

☆人獣共通感染症(じんじゅうきょうつうかんせんしょう; zoonosis

)とは、非ヒト脊椎動物からヒトへ感染する病原体(ウイルス、細菌、寄生虫、真菌、

プリオンなどの感染性因子)によって引き起こされるヒトの感染症である。人間が非人間に感染させる場合は、逆人獣共通感染症または人獣共通感染症と呼ばれ

る。[2][1][3][4]

エボラ出血熱やサルモネラ症などの現代の主要な疾病は人獣共通感染症である。HIVは20世紀初頭に人間に伝播した人獣共通感染症だったが、現在では人間

のみに感染する独立した疾病へと進化した。[5][6][7]

動物由来のインフルエンザウイルスのヒトへの感染は稀である。これらのウイルスはヒト間やヒトへの伝播が容易ではないからだ。[8]

しかし特に鳥インフルエンザウイルスや豚インフルエンザウイルスは高い人獣共通感染症の潜在性を有し、これらがヒト型インフルエンザウイルスと再結合する

ことで、2009年の新型インフルエンザのようなパンデミックを引き起こすことがある。[10]

動物由来感染症は、新興ウイルス、細菌、真菌、寄生虫など様々な病原体によって引き起こされる。ヒトに感染することが知られている1,415種の病原体の

うち、61%が動物由来であった。[11]

ヒトの病気のほとんどは非ヒト生物に起源を持つが、狂犬病のように非ヒトからヒトへの伝播が常態化している疾患のみが直接的な動物由来感染症と見なされ

る。[12]

人獣共通感染症には異なる感染経路がある。直接感染では、空気(インフルエンザ)、咬傷や唾液(狂犬病)、[13]糞口感染、あるいは汚染食品を介して非

人間から人間へ直接伝播する。また、病原体を保有しながら自身は発症しない中間宿主(媒介生物と呼ばれる)を介した伝播も起こり得る。この用語は古代ギリ

シャ語のζῷον(zoon)「動物」とνόσος(nosos)「病気」に由来する。

宿主の遺伝的特性は、どの非ヒトウイルスがヒト体内での自己複製を可能にするかを決定する上で重要な役割を果たす。危険な非ヒトウイルスとは、ヒト細胞内

で自己複製を開始するために必要な変異が少ないものである。これらのウイルスは、必要な変異の組み合わせが自然界の保菌宿主において偶然に生じうるため危

険である。

| A zoonosis

(/zoʊˈɒnəsɪs, ˌzoʊəˈnoʊsɪs/ ⓘ;[1] plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease

is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious

agent, such as a virus, bacterium, parasite, fungi, or prion) that can

jump from a non-human vertebrate to a human. When humans infect

non-humans, it is called reverse zoonosis or anthroponosis.[2][1][3][4] Major modern diseases such as Ebola and salmonellosis are zoonoses. HIV was a zoonotic disease transmitted to humans in the early part of the 20th century, though it has now evolved into a separate human-only disease.[5][6][7] Human infection with animal influenza viruses is rare, as they do not transmit easily to or among humans.[8] However, avian and swine influenza viruses in particular possess high zoonotic potential,[9] and these occasionally recombine with human strains of the flu and can cause pandemics such as the 2009 swine flu.[10] Zoonoses can be caused by a range of disease pathogens such as emergent viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites; of 1,415 pathogens known to infect humans, 61% were zoonotic.[11] Most human diseases originated in non-humans; however, only diseases that routinely involve non-human to human transmission, such as rabies, are considered direct zoonoses.[12] Zoonoses have different modes of transmission. In direct zoonosis the disease is directly transmitted between non-humans and humans through the air (influenza), bites and saliva (rabies),[13] faecal-oral transmission or through contaminated food. Transmission can also occur via an intermediate species (referred to as a vector), which carry the disease pathogen without getting sick. The term is from Ancient Greek ζῷον (zoon) 'animal' and νόσος (nosos) 'sickness'. Host genetics plays an important role in determining which non-human viruses will be able to make copies of themselves in the human body. Dangerous non-human viruses are those that require few mutations to begin replicating themselves in human cells. These viruses are dangerous since the required combinations of mutations might randomly arise in the natural reservoir.[14] |

人獣共通感染症(じんじゅうきょうつうかんせんしょう)とは、非ヒト脊

椎動物からヒトへ感染する病原体(ウイルス、細菌、寄生虫、真菌、プリオンなどの感染性因子)によって引き起こされるヒトの感染症である。人間が非人間に

感染させる場合は、逆人獣共通感染症または人獣共通感染症と呼ばれる。[2][1][3][4] エボラ出血熱やサルモネラ症などの現代の主要な疾病は人獣共通感染症である。HIVは20世紀初頭に人間に伝播した人獣共通感染症だったが、現在では人間 のみに感染する独立した疾病へと進化した。[5][6][7] 動物由来のインフルエンザウイルスのヒトへの感染は稀である。これらのウイルスはヒト間やヒトへの伝播が容易ではないからだ。[8] しかし特に鳥インフルエンザウイルスや豚インフルエンザウイルスは高い人獣共通感染症の潜在性を有し、これらがヒト型インフルエンザウイルスと再結合する ことで、2009年の新型インフルエンザのようなパンデミックを引き起こすことがある。[10] 動物由来感染症は、新興ウイルス、細菌、真菌、寄生虫など様々な病原体によって引き起こされる。ヒトに感染することが知られている1,415種の病原体の うち、61%が動物由来であった。[11] ヒトの病気のほとんどは非ヒト生物に起源を持つが、狂犬病のように非ヒトからヒトへの伝播が常態化している疾患のみが直接的な動物由来感染症と見なされ る。[12] 人獣共通感染症には異なる感染経路がある。直接感染では、空気(インフルエンザ)、咬傷や唾液(狂犬病)、[13]糞口感染、あるいは汚染食品を介して非 人間から人間へ直接伝播する。また、病原体を保有しながら自身は発症しない中間宿主(媒介生物と呼ばれる)を介した伝播も起こり得る。この用語は古代ギリ シャ語のζῷον(zoon)「動物」とνόσος(nosos)「病気」に由来する。 宿主の遺伝的特性は、どの非ヒトウイルスがヒト体内での自己複製を可能にするかを決定する上で重要な役割を果たす。危険な非ヒトウイルスとは、ヒト細胞内 で自己複製を開始するために必要な変異が少ないものである。これらのウイルスは、必要な変異の組み合わせが自然界の保菌宿主において偶然に生じうるため危 険である。 |

| Causes The emergence of zoonotic diseases originated with the domestication of animals.[15][16] Zoonotic transmission can occur in any context in which there is contact with or consumption of animals, animal products, or animal derivatives. This can occur in a companionistic (pets)[16], economic (farming, trade, butchering, etc.), predatory (hunting, butchering, or consuming wild game), or research context.[17][18] Recently, there has been a rise in frequency of appearance of new zoonotic diseases. "Approximately 1.67 million undescribed viruses are thought to exist in mammals and birds, up to half of which are estimated to have the potential to spill over into humans", says a study[19] led by researchers at the University of California, Davis. According to a report from the United Nations Environment Programme and International Livestock Research Institute a large part of the causes are environmental like climate change, unsustainable agriculture, exploitation of wildlife, and land use change. Others are linked to changes in human society such as an increase in mobility. The organizations propose a set of measures to stop the rise.[20][21] |

原因 人獣共通感染症の出現は、動物の家畜化に端を発する。[15][16] 動物、動物製品、動物由来物質との接触や摂取が伴うあらゆる状況で人獣共通感染症の伝播は起こり得る。これは伴侶動物(ペット)[16]、経済活動(農 業、取引、屠殺など)、捕食(狩猟、解体、野生動物の摂取)、研究活動といった文脈で発生し得る。[17] [18] 最近、新しい人獣共通感染症が出現する頻度が高まっている。カリフォルニア大学デイヴィス校の研究者らが主導した研究[19]によると、「哺乳類や鳥類に は、約 167 万種の未発見のウイルスが存在すると考えられており、その最大半数がヒトに感染する可能性がある」と推定されている。国連環境計画と国際家畜研究所の報告 書によると、その原因の大部分は、気候変動、持続不可能な農業、野生生物の搾取、土地利用の変化などの環境要因である。その他は、移動性の増加など、人間 社会の変化に関連している。これらの組織は、その増加を食い止めるための一連の対策を提案している。 |

| Contamination of food or water supply Foodborne zoonotic diseases are caused by a variety of pathogens that can affect both humans and animals. The most significant zoonotic pathogens causing foodborne diseases are: Bacterial pathogens Escherichia coli O157:H7, Campylobacter, Caliciviridae, and Salmonella.[22][23][24] Viral pathogens Hepatitis E: Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is primarily transmitted through pork products, especially in developing countries with limited sanitation. The infection can lead to acute liver disease and is particularly dangerous for pregnant women.[25] Norovirus: Often found in contaminated shellfish and fresh produce, norovirus is a leading cause of foodborne illness globally. It spreads easily and causes symptoms like vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach pain.[26] Parasitic pathogens Toxoplasma gondii: This parasite is commonly found in undercooked meat, especially pork and lamb, and can cause toxoplasmosis. While typically mild, toxoplasmosis can be severe in immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women, potentially leading to complications.[27] Trichinella spp. is transmitted through undercooked pork and wild game, causing trichinellosis. Symptoms range from mild gastrointestinal distress to severe muscle pain and, in rare cases, can be fatal.[28] |

食品や水供給の汚染 食中毒を引き起こす人獣共通感染症は、人間と動物の両方に影響を与える様々な病原体によって引き起こされる。食中毒を引き起こす最も重要な人獣共通病原体は以下の通りである: 細菌性病原体 大腸菌O157:H7、カンピロバクター、カリシウイルス科、サルモネラ菌。[22][23][24] ウイルス性病原体 E型肝炎:E型肝炎ウイルス(HEV)は主に豚肉製品を介して感染し、衛生環境が整っていない発展途上国で特に問題となる。感染は急性肝疾患を引き起こす可能性があり、妊婦にとって特に危険である。[25] ノロウイルス:汚染された貝類や生鮮食品に多く見られるノロウイルスは、世界的に食中毒の主要な原因である。感染力が強く、嘔吐、下痢、腹痛などの症状を引き起こす。[26] 寄生虫病原体 トキソプラズマ・ゴンディイ:この寄生虫は加熱不十分な肉、特に豚肉や羊肉に広く存在し、トキソプラズマ症を引き起こす。通常は軽症だが、免疫不全者や妊婦では重篤化し合併症を招く可能性がある。[27] トリキネラ属は加熱不十分な豚肉や野生肉を介して感染し、トリキネラ症を引き起こす。症状は軽度の胃腸障害から重度の筋肉痛まで様々で、稀に致命的となる場合もある。[28] |

| Farming, ranching and animal husbandry See also: Intensive animal farming § Human health impact Contact with farm animals can lead to disease in farmers or others that come into contact with infected farm animals. Glanders primarily affects those who work closely with horses and donkeys. Close contact with cattle can lead to cutaneous anthrax infection, whereas inhalation anthrax infection is more common for workers in slaughterhouses, tanneries, and wool mills.[29] Close contact with sheep who have recently given birth can lead to infection with the bacterium Chlamydia psittaci, causing chlamydiosis (and enzootic abortion in pregnant women), as well as increase the risk of Q fever, toxoplasmosis, and listeriosis, in the pregnant or otherwise immunocompromised. Echinococcosis is caused by a tapeworm, which can spread from infected sheep by food or water contaminated by feces or wool. Avian influenza is common in chickens, and, while it is rare in humans, the main public health worry is that a strain of avian influenza will recombine with a human influenza virus and cause a pandemic like the 1918 Spanish flu.[30] In 2017, free-range chickens in the UK were temporarily ordered to remain inside due to the threat of avian influenza.[31] Cattle are an important reservoir of cryptosporidiosis,[32] which mainly affects the immunocompromised. Reports have shown mink can also become infected.[33] In Western countries, hepatitis E burden is largely dependent on exposure to animal products, and pork is a significant source of infection, in this respect.[25] Similarly, the human coronavirus OC43, the main cause of the common cold, can use the pig as a zoonotic reservoir,[34] constantly reinfecting the human population. Veterinarians are exposed to unique occupational hazards when it comes to zoonotic disease. In the US, studies have highlighted an increased risk of injuries and lack of veterinary awareness of these hazards. Research has proved the importance for continued clinical veterinarian education on occupational risks associated with musculoskeletal injuries, animal bites, needle-sticks, and cuts.[35] A July 2020 report by the United Nations Environment Programme stated that the increase in zoonotic pandemics is directly attributable to anthropogenic destruction of nature and the increased global demand for meat and that the industrial farming of pigs and chickens in particular will be a primary risk factor for the spillover of zoonotic diseases in the future.[36] Habitat loss of viral reservoir species has been identified as a significant source in at least one spillover event.[37] |

農業、牧畜、畜産 関連項目:集約的畜産 § 人間の健康への影響 家畜との接触は、農家や感染した家畜と接触する者に疾病を引き起こす可能性がある。鼻疽は主に馬やロバと密接に働く者に影響する。牛との密接な接触は皮膚 炭疽感染を引き起こす一方、食肉処理場、皮革工場、羊毛工場の労働者には吸入炭疽感染がより一般的である。[29] 出産直後の羊との密接な接触は、クラミジア・シッタチ菌による感染を引き起こす可能性がある。これによりクラミジア症(妊婦ではエンゾーティック流産)が 発生するほか、妊娠中または免疫不全状態にある者においてQ熱、トキソプラズマ症、リステリア症のリスクが高まる。エキノコックス症は条虫によって引き起 こされ、感染した羊の糞便や羊毛で汚染された食物や水を介して広がる。鳥インフルエンザは鶏に広く見られ、人間への感染は稀だが、公衆健康上の主な懸念は 鳥インフルエンザ株がヒトインフルエンザウイルスと再結合し、1918年のスペイン風邪のようなパンデミックを引き起こす可能性である。[30] 2017年、英国では鳥インフルエンザの脅威により、放し飼いの鶏を一時的に屋内飼育するよう命令が出された。[31] 牛はクリプトスポリジウム症の重要な保菌動物であり、[32] 主に免疫不全者に影響を与える。ミンクも感染することが報告されている[33]。西洋諸国では、E型肝炎の感染リスクは主に動物性食品への曝露に依存して おり、この点で豚肉は重要な感染源である[25]。同様に、風邪の主な原因であるヒトコロナウイルスOC43は、豚を人獣共通感染症の保菌宿主として利用 し[34]、人間集団に絶えず再感染を引き起こしている。 獣医師は人獣共通感染症に関して特有の職業的危険に晒されている。米国では、負傷リスクの増加と獣医師の危険性認識不足が研究で指摘されている。筋骨格系 損傷、動物咬傷、針刺し、切創に関連する職業的リスクについて、臨床獣医師の継続教育の重要性が研究で証明されている[35]。 国連環境計画(UNEP)の2020年7月報告書は、人獣共通感染症のパンデミック増加が、人為的な自然破壊と世界的な肉需要の増加に直接起因すると指摘 した。特に豚や鶏の工業的飼育が、将来の人獣共通感染症の拡散における主要なリスク要因となるだろうと述べている[36]。ウイルス保菌種の生息地喪失 は、少なくとも1件の拡散事例において重要な要因と特定されている[37]。 |

| Wildlife trade or animal attacks The wildlife trade may increase spillover risk because it directly increases the number of interactions across animal species, sometimes in small spaces.[38] The origin of the COVID-19 pandemic[39][40] is traced to the wet markets in China.[41][42][43][44] Zoonotic disease emergence is demonstrably linked to the consumption of wildlife meat, exacerbated by human encroachment into natural habitats and amplified by the unsanitary conditions of wildlife markets.[45][46] These markets, where diverse species converge, facilitate the mixing and transmission of pathogens, including those responsible for outbreaks of HIV-1,[47] Ebola,[48] and mpox,[49] and potentially even the COVID-19 pandemic.[50] Notably, small mammals often harbor a vast array of zoonotic bacteria and viruses,[51] yet endemic bacterial transmission among wildlife remains largely unexplored. Therefore, accurately determining the pathogenic landscape of traded wildlife is crucial for guiding effective measures to combat zoonotic diseases and documenting the societal and environmental costs associated with this practice. |

野生生物取引や動物による襲撃 野生生物取引は、動物種間の接触機会を直接的に増加させるため、時には狭い空間で発生する。これにより感染リスクが高まる可能性がある[38]。COVID-19パンデミックの起源[39][40]は、中国の生鮮市場に遡るとされている[41][42][43][44]。 人獣共通感染症の発生は、野生動物の肉類の消費と明らかに関連しており、人間の自然生息地への侵入によって悪化し、野生動物市場の非衛生的な状況によって 増幅される。[45][46] 多様な種が集まるこれらの市場は、HIV-1[47]、 エボラ出血熱[48]、サル痘[49]、さらにはCOVID-19パンデミック[50]の原因となる病原体も含まれる。特に小型哺乳類は多様な人獣共通感 染症の細菌やウイルスを保有することが多い[51]が、野生動物間での固有細菌の伝播はほとんど解明されていない。したがって、取引される野生動物の病原 体分布を正確に把握することは、人獣共通感染症対策の効果的な指針策定と、この慣行に伴う社会的・環境的コストの記録において極めて重要である。 |

| Insect vectors ++++++++++++ African sleeping sickness Dirofilariasis Eastern equine encephalitis Japanese encephalitis Saint Louis encephalitis Scrub typhus Tularemia Venezuelan equine encephalitis West Nile fever Western equine encephalitis Zika fever |

昆虫媒介 +++++++ アフリカ睡眠病 犬糸状虫症 東部馬脳炎 日本脳炎 セントルイス脳炎 森林斑点熱 野兎病 ベネズエラ馬脳炎 西ナイル熱 西部馬脳炎 ジカ熱 |

| Pets Further information: Feline zoonosis Pets can transmit a number of diseases. Dogs and cats are routinely vaccinated against rabies. Pets can also transmit ringworm and Giardia, which are endemic in both animal and human populations. Toxoplasmosis is a common infection of cats; in humans it is a mild disease although it can be dangerous to pregnant women.[52] Dirofilariasis is caused by Dirofilaria immitis through mosquitoes infected by mammals like dogs and cats. Cat-scratch disease is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana, which are transmitted by fleas that are endemic to cats. Toxocariasis is the infection of humans by any of species of roundworm, including species specific to dogs (Toxocara canis) or cats (Toxocara cati). Cryptosporidiosis can be spread to humans from pet lizards, such as the leopard gecko. Encephalitozoon cuniculi is a microsporidial parasite carried by many mammals, including rabbits, and is an important opportunistic pathogen in people immunocompromised by HIV/AIDS, organ transplantation, or CD4+ T-lymphocyte deficiency.[53] Pets may also serve as a reservoir of viral disease and contribute to the chronic presence of certain viral diseases in the human population. For instance, approximately 20% of domestic dogs, cats, and horses carry anti-hepatitis E virus antibodies and thus these animals probably contribute to human hepatitis E burden as well.[54] For non-vulnerable populations (e.g., people who are not immunocompromised) the associated disease burden is, however, small.[55][56] Furthermore, the trade of non-domestic animals such as wild animals as pets can also increase the risk of zoonosis spread.[57][58] Bats are frequently unjustly portrayed as the primary instigators of the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic; nevertheless, the true origins of this and other zoonotic spillover occurrences should be attributed to human environmental impacts, especially the proliferation of pets.[16] For example, bat predation by cats poses a significant danger to biodiversity conservation and carries zoonotic consequences that must be acknowledged.[16] |

ペット 詳細情報:猫由来の動物由来感染症 ペットは様々な病気を媒介する。犬や猫は狂犬病の予防接種を定期的に受ける。ペットはまた、動物と人間の両方に広く存在する白癬やジアルジアを媒介する。 トキソプラズマ症は猫によく見られる感染であり、人間では軽度の病気だが、妊婦には危険となる場合がある。[52] 犬糸状虫症は、犬や猫などの哺乳類に感染した蚊を介してディロフィラリア・イミティスが引き起こす。猫ひっかき病は、猫に寄生するノミによって伝播される バルトネラ・ヘンセラエとバルトネラ・キンタナが原因である。トキソカラ症は、犬(トキソカラ・カニス)や猫(トキソカラ・カティ)に特有の種を含む、あ らゆる回虫種によるヒトの感染である。(トキソカラ・カティ)など)によるヒトへの感染である。クリプトスポリジウム症は、レオパードゲッコーなどのペッ ト用トカゲからヒトへ感染する可能性がある。エンセファリトゾオン・クニクリはウサギを含む多くの哺乳類が保有する微胞子虫寄生虫であり、 HIV/AIDS、臓器移植、CD4+ Tリンパ球欠乏症などにより免疫不全状態にある人々において重要な日和見病原体である。[53] ペットはウイルス性疾患の保菌源となり、ヒト集団における特定ウイルス性疾患の慢性的な存在に寄与する可能性がある。例えば、飼い犬、飼い猫、飼い馬の約 20%がE型肝炎ウイルスに対する抗体を保有しており、これらの動物もおそらくヒトのE型肝炎負担の一因となっている。[54] ただし、免疫不全状態にない非脆弱集団における関連疾病負担は小さい。[55][56] さらに、野生動物などの非家畜動物をペットとして取引することも、人獣共通感染症拡散のリスクを高める。[57] [58] コウモリは、現在進行中のCOVID-19流行の主な原因として不当に描かれることが多い。しかしながら、この事例やその他の人獣共通感染症の発生源は、 人間の環境への影響、特にペットの増加に起因すると考えるべきである。[16] 例えば、猫によるコウモリの捕食は生物多様性保全にとって重大な脅威であり、認識すべき人獣共通感染症のリスクを伴う。[16] |

| Exhibition Outbreaks of zoonoses have been traced to human interaction with, and exposure to, other animals at fairs, live animal markets,[59] petting zoos, and other settings. In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an updated list of recommendations for preventing zoonosis transmission in public settings.[60] The recommendations, developed in conjunction with the National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians,[61] include educational responsibilities of venue operators, limiting public animal contact, and animal care and management. |

展示会 人獣共通感染症の発生は、見本市、生きた動物の市場[59]、ふれあい動物園、その他の環境における人間と他の動物との接触や曝露に起因することが確認さ れている。2005年、米国疾病予防管理センター(CDC)は公共の場における人獣共通感染症伝播防止のための推奨事項を更新した[60]。全米州公衆健 康獣医師協会[61]と共同で策定されたこの推奨事項には、施設運営者の教育責任、一般市民の動物接触制限、動物の世話と管理が含まれている。 |

| Hunting and bushmeat Main articles: Hunting and Bushmeat Hunting involves humans tracking, chasing, and capturing wild animals, primarily for food or materials like fur. However, other reasons like pest control or managing wildlife populations can also exist. Transmission of zoonotic diseases, those leaping from animals to humans, can occur through various routes: direct physical contact, airborne droplets or particles, bites or vector transport by insects, oral ingestion, or even contact with contaminated environments.[62] Wildlife activities like hunting and trade bring humans closer to dangerous zoonotic pathogens, threatening global health.[63] According to the Center for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) hunting and consuming wild animal meat ("bushmeat") in regions like Africa can expose people to infectious diseases due to the types of animals involved, like bats and primates. Unfortunately, common preservation methods like smoking or drying aren't enough to eliminate these risks.[64] Although bushmeat provides protein and income for many, the practice is intricately linked to numerous emerging infectious diseases like Ebola, HIV, and SARS, raising critical public health concerns.[63] A review published in 2022 found evidence that zoonotic spillover linked to wildmeat consumption has been reported across all continents.[65] |

狩猟とブッシュミート 主な記事:狩猟とブッシュミート 狩猟とは、人間が野生動物を追跡し、追い詰め、捕獲する行為を指す。主な目的は食料や毛皮などの材料を得るためである。ただし、害虫駆除や野生生物の個体 数管理といった他の理由も存在する。人獣共通感染症(動物から人間へ感染する病気)の伝播は、様々な経路で起こる:直接的な物理的接触、飛沫や粒子による 空気感染、咬傷や昆虫媒介、経口摂取、さらには汚染環境との接触などである[62]。狩猟や取引といった野生生物に関わる活動は、人間を危険な人獣共通病 原体に近づけ、世界の健康を脅かす。[63] 米国疾病予防管理センター(CDC)によれば、アフリカなどの地域における野生動物の肉(「ブッシュミート」)の狩猟・消費は、コウモリや霊長類など対象 動物の種類により、人民に感染症への曝露リスクをもたらす。残念ながら、燻製や乾燥といった一般的な保存方法では、これらのリスクを消去法による排除する には不十分だ。[64] ブッシュミートは多くの人々にタンパク質と収入をもたらすが、この慣行はエボラ、HIV、SARSなど数多くの新興感染症と複雑に結びついており、重大な 公衆健康上の懸念を引き起こしている。[63] 2022年に発表されたレビューでは、野生肉消費に関連する人獣共通感染症の流出が全大陸で報告されている証拠が確認された。[65] |

| Deforestation, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation Main articles: Deforestation, Biodiversity loss, and Environmental degradation Kate Jones, Chair of Ecology and Biodiversity at University College London, says zoonotic diseases are increasingly linked to environmental change and human behavior. The disruption of pristine forests driven by logging, mining, road building through remote places, rapid urbanization, and population growth is bringing people into closer contact with animal species they may never have been near before. The resulting transmission of disease from wildlife to humans, she says, is now "a hidden cost of human economic development".[66] In a guest article, published by IPBES, President of the EcoHealth Alliance and zoologist Peter Daszak, along with three co-chairs of the 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Josef Settele, Sandra Díaz, and Eduardo Brondizio, wrote that "rampant deforestation, uncontrolled expansion of agriculture, intensive farming, mining and infrastructure development, as well as the exploitation of wild species have created a 'perfect storm' for the spillover of diseases from wildlife to people."[67] Joshua Moon, Clare Wenham, and Sophie Harman said that there is evidence that decreased biodiversity has an effect on the diversity of hosts and frequency of human-animal interactions with potential for pathogenic spillover.[68] An April 2020 study, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society's Part B journal, found that increased virus spillover events from animals to humans can be linked to biodiversity loss and environmental degradation, as humans further encroach on wildlands to engage in agriculture, hunting, and resource extraction they become exposed to pathogens which normally would remain in these areas. Such spillover events have been tripling every decade since 1980.[69] An August 2020 study, published in Nature, concludes that the anthropogenic destruction of ecosystems for the purpose of expanding agriculture and human settlements reduces biodiversity and allows for smaller animals such as bats and rats, which are more adaptable to human pressures and also carry the most zoonotic diseases, to proliferate. This in turn can result in more pandemics.[70] In October 2020, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services published its report on the 'era of pandemics' by 22 experts in a variety of fields and concluded that anthropogenic destruction of biodiversity is paving the way to the pandemic era and could result in as many as 850,000 viruses being transmitted from animals – in particular birds and mammals – to humans. The increased pressure on ecosystems is being driven by the "exponential rise" in consumption and trade of commodities such as meat, palm oil, and metals, largely facilitated by developed nations, and by a growing human population. According to Peter Daszak, the chair of the group who produced the report, "there is no great mystery about the cause of the Covid-19 pandemic, or of any modern pandemic. The same human activities that drive climate change and biodiversity loss also drive pandemic risk through their impacts on our environment."[71][72][73] |

森林破壊、生物多様性の喪失、環境悪化 主な記事:森林破壊、生物多様性の喪失、環境悪化 ロンドン大学ユニバーシティ・カレッジの生態学・生物多様性学部長であるケイト・ジョーンズは、人獣共通感染症が環境変化と人間の行動にますます関連して いると述べている。伐採、鉱業、僻地での道路建設、急速な都市化、人口増加によって原生林が破壊されることで、人々はこれまで近づくことのなかった動物種 とより密接に接触するようになった。その結果生じる野生生物から人間への疾病伝播は、今や「人間経済発展の隠れた代償」だと彼女は言う。[66] IPBESが発表した寄稿記事で、エコヘルス・アライアンス会長で動物学者のピーター・ダザックは、2019年生物多様性・生態系サービスに関する世界評 価報告書の共同議長3名——ヨーゼフ・ゼッテレ、 サンドラ・ディアス、エドゥアルド・ブロンディジオは、「森林の乱伐、農業の無秩序な拡大、集約農業、鉱業、インフラ開発、そして野生生物の搾取が、野生 生物から人々への病気の波及に「最悪の事態」を招いている」と記している。[67] ジョシュア・ムーン、クレア・ウェナム、ソフィー・ハーマンは、生物多様性の減少が宿主の多様性や人間と動物の接触頻度に影響を与え、病原体の感染拡大の可能性を高めるという証拠があると述べている[68]。 2020年4月に英国王立協会紀要B誌に掲載された研究によると、動物から人間へのウイルス感染の増加は、生物多様性の損失や環境悪化と関連している可能 性がある。人間は農業、狩猟、資源採掘のために野生地域への侵入を進め、通常はこれらの地域に留まっているはずの病原体にさらされるようになった。このよ うな感染事例は、1980年以降、10年ごとに3倍に増加している。[69] 2020年8月に『ネイチャー』誌に掲載された研究は、農業拡大や人間居住地拡大のための人為的な生態系破壊が生物多様性を減少させ、コウモリやネズミな ど人間による圧力に適応しやすく、かつ最も多くの人獣共通感染症を媒介する小型動物の繁殖を許すと結論づけている。これがさらにパンデミックの増加につな がる可能性がある。[70] 2020年10月、生物多様性及び生態系サービスに関する政府間科学政策プラットフォーム(IPBES)は、様々な分野の専門家22名による「パンデミッ クの時代」に関する報告書を発表した。そこでは、人為的な生物多様性の破壊がパンデミックの時代への道を開き、最大85万種のウイルスが動物(特に鳥類と 哺乳類)から人間へ伝播する可能性があると結論づけられた。生態系への圧力増大は、主に先進国民によって促進された肉、パーム油、金属などの商品消費・取 引の「指数関数的増加」と、増加する人口によって駆動されている。報告書作成グループの議長ピーター・ダザックによれば、「COVID-19パンデミック や現代のあらゆるパンデミックの原因に、大きな謎はない。」 気候変動や生物多様性の喪失を招く人間活動は、環境への影響を通じてパンデミックリスクも高めているのだ」と述べている。[71][72][73] |

| Climate change Further information: Climate change and infectious diseases According to a report from the United Nations Environment Programme and International Livestock Research Institute, entitled "Preventing the next pandemic – Zoonotic diseases and how to break the chain of transmission", climate change is one of the 7 human-related causes of the increase in the number of zoonotic diseases.[20][21] The University of Sydney issued a study, in March 2021, that examines factors increasing the likelihood of epidemics and pandemics like the COVID-19 pandemic. The researchers found that "pressure on ecosystems, climate change and economic development are key factors" in doing so. More zoonotic diseases were found in high-income countries.[74] A 2022 study dedicated to the link between climate change and zoonosis found a strong link between climate change and the epidemic emergence in the last 15 years, as it caused a massive migration of species to new areas, and consequently contact between species which do not normally come in contact with one another. Even in a scenario with weak climatic changes, there will be 15,000 spillover of viruses to new hosts in the next decades. The areas with the most possibilities for spillover are the mountainous tropical regions of Africa and southeast Asia. Southeast Asia is especially vulnerable as it has a large number of bat species that generally do not mix, but could easily if climate change forced them to begin migrating.[75] A 2021 study found possible links between climate change and transmission of COVID-19 through bats. The authors suggest that climate-driven changes in the distribution and robustness of bat species harboring coronaviruses may have occurred in eastern Asian hotspots (southern China, Myanmar, and Laos), constituting a driver behind the evolution and spread of the virus.[76][77] |

気候変動 詳細情報:気候変動と感染症 国連環境計画と国際家畜研究所の報告書「次のパンデミックを防ぐ―人獣共通感染症と感染連鎖の断ち切り方」によれば、気候変動は人獣共通感染症の増加をも たらす7つの人為的要因の一つである。[20][21] シドニー大学は2021年3月、COVID-19パンデミックのような流行やパンデミック発生の可能性を高める要因を検証した研究を発表した。研究者らは 「生態系への圧力、気候変動、経済発展が主要な要因である」と結論付けた。高所得国ではより多くの動物由来感染症が確認された。[74] 気候変動と人獣共通感染症の関連性を専門に調査した2022年の研究では、気候変動が過去15年間の感染症発生と強い関連性を持つことが判明した。気候変 動が生物種の新地域への大規模な移動を引き起こし、通常接触しない種同士の接触を生んだためである。気候変動の影響が弱いシナリオであっても、今後数十年 で15,000件のウイルスが新たな宿主へ感染する可能性があると予測されている。ウイルスが最も飛び移る可能性が高い地域は、アフリカと東南アジアの山 岳熱帯地域だ。東南アジアは特に脆弱で、通常はミヘしない多数のコウモリ種が生息しているが、気候変動によって移動を余儀なくされれば容易にミヘする可能 性がある。[75] 2021年の研究では、気候変動とコウモリを介したCOVID-19感染の伝播との関連性が示唆された。著者らは、コロナウイルスを保有するコウモリ種の 分布範囲と生存力の気候変動による変化が、東アジアの感染ホットスポット(中国南部、ミャンマー、ラオス)で生じ、ウイルスの進化と拡散の要因となった可 能性を指摘している。[76][77] |

| Secondary transmission Zoonotic diseases contribute significantly to the burdened public health system as vulnerable groups such the elderly, children, childbearing women and immune-compromised individuals are at risk.[citation needed] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), any disease or infection that is primarily "naturally" transmissible from vertebrate animals to humans or from humans to animals is classified as a zoonosis.[78] Factors such as climate change, urbanization, animal migration and trade, travel and tourism, vector biology, anthropogenic factors, and natural factors have greatly influenced the emergence, re-emergence, distribution, and patterns of zoonoses.[78] Zoonotic diseases generally refer to diseases of animal origin in which direct or vector mediated animal-to-human transmission is the usual source of human infection. Animal populations are the principal reservoir of the pathogen and horizontal infection in humans is rare. A few examples in this category include lyssavirus infections, Lyme borreliosis, plague, tularemia, leptospirosis, ehrlichiosis, Nipah virus, West Nile virus, and hantavirus infections.[79] Secondary transmission encompasses a category of diseases of animal origin in which the actual transmission to humans is a rare event but, once it has occurred, human-to-human transmission maintains the infection cycle for some period of time. Some examples include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), certain influenza A strains, Ebola virus and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).[79] One example is Ebola, which is spread by direct transmission to humans from handling bushmeat (wild animals hunted for food) and contact with infected bats or close contact with infected animals, including chimpanzees, fruit bats, and forest antelope. Secondary transmission also occurs from human to human by direct contact with blood, bodily fluids, or skin of patients with or who died of Ebola virus disease.[80] Some examples of pathogens with this pattern of secondary transmission are human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, influenza A, Ebola virus, and SARS. Recent infections of these emerging and re-emerging zoonotic infections have occurred as a results of many ecological and sociological changes globally.[79] |

二次感染 人獣共通感染症は、高齢者、子供、妊婦、免疫不全者などの脆弱な集団が危険にさらされるため、公衆健康システムに大きな負担をもたらす。[出典が必要] 世界保健機関(WHO)によれば、主に脊椎動物から人間へ、あるいは人間から動物へ「自然」に伝染するあらゆる疾病や感染は人獣共通感染症に分類される。 [78] 気候変動、都市化、動物の移動と取引、旅行と観光、媒介生物の生態、人為的要因、自然要因といった要素が、人獣共通感染症の発生、再出現、分布、およびパ ターンに大きく影響している。[78] 人獣共通感染症は一般に、動物由来の疾患を指し、直接または媒介生物を介した動物から人間への伝播が、通常の人間感染源となる。動物集団が病原体の主要な 保菌源であり、人間における水平感染は稀である。このカテゴリーに属する例としては、リッサウイルス感染症、ライム病、ペスト、野兎病、レプトスピラ症、 エールリキア症、ニパウイルス、ウエストナイルウイルス、ハンタウイルス感染症などが挙げられる。二次感染は、動物由来疾患のうち、ヒトへの実際の感染は 稀であるが、一度発生するとヒトからヒトへの感染が一定期間感染サイクルを維持するカテゴリーに属する。例としては、ヒト免疫不全ウイルス(HIV)/後 天性免疫不全症候群(AIDS)、特定のA型インフルエンザウイルス株、エボラウイルス、重症急性呼吸器症候群(SARS)などが挙げられる。 一例としてエボラが挙げられる。これは、ブッシュミート(食用に狩猟された野生動物)の取り扱い、感染したコウモリとの接触、あるいはチンパンジー、オオ コウモリ、森林アンテロープなどの感染動物との密接な接触による人間への直接感染で広がる。二次感染は、エボラウイルス感染症患者または死亡者の血液、体 液、皮膚との直接接触による人間同士の感染でも発生する。[80] この二次感染パターンを示す病原体の例としては、ヒト免疫不全ウイルス/後天性免疫不全症候群、A型インフルエンザ、エボラウイルス、SARSが挙げられ る。これらの新興・再興の人獣共通感染症の最近の感染は、世界的な多くの生態学的・社会学的変化の結果として発生している。[79] |

| History During most of human prehistory groups of hunter-gatherers were probably very small. Such groups probably made contact with other such bands only rarely. Such isolation would have caused epidemic diseases to be restricted to any given local population, because propagation and expansion of epidemics depend on frequent contact with other individuals who have not yet developed an adequate immune response.[81] To persist in such a population, a pathogen either had to be a chronic infection, staying present and potentially infectious in the infected host for long periods, or it had to have other additional species as reservoir where it can maintain itself until further susceptible hosts are contacted and infected.[82][83] In fact, for many "human" diseases, the human is actually better viewed as an accidental or incidental victim and a dead-end host. Examples include rabies, anthrax, tularemia, and West Nile fever. Thus, much of human exposure to infectious disease has been zoonotic.[84]  Possibilities for zoonotic disease transmissions Many diseases, even epidemic ones, have zoonotic origin and measles, smallpox, influenza, HIV, and diphtheria are particular examples.[85][86] Various forms of the common cold and tuberculosis also are adaptations of strains originating in other species.[87][88] Some experts have suggested that all human viral infections were originally zoonotic.[89] Zoonoses are of interest because they are often previously unrecognized diseases or have increased virulence in populations lacking immunity. The West Nile virus first appeared in the United States in 1999, in the New York City area. Bubonic plague is a zoonotic disease,[90] as are salmonellosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Lyme disease. A major factor contributing to the appearance of new zoonotic pathogens in human populations is increased contact between humans and wildlife.[91] This can be caused either by encroachment of human activity into wilderness areas or by movement of wild animals into areas of human activity. An example of this is the outbreak of Nipah virus in peninsular Malaysia, in 1999, when intensive pig farming began within the habitat of infected fruit bats.[92] The unidentified infection of these pigs amplified the force of infection, transmitting the virus to farmers, and eventually causing 105 human deaths.[93] Similarly, in recent times avian influenza and West Nile virus have spilled over into human populations probably due to interactions between the carrier host and domestic animals.[94] Highly mobile animals, such as bats and birds, may present a greater risk of zoonotic transmission than other animals due to the ease with which they can move into areas of human habitation. Because they depend on the human host[95] for part of their life-cycle, diseases such as African schistosomiasis, river blindness, and elephantiasis are not defined as zoonotic, even though they may depend on transmission by insects or other vectors.[citation needed] |

歴史 人類の先史時代の大半において、狩猟採集民の集団はおそらく非常に小規模だった。こうした集団が他の同種の集団と接触するのは稀だっただろう。このような 孤立状態は、伝染病が特定の地域集団に限定される原因となった。伝染病の拡大と蔓延は、十分な免疫反応を発達させていない他の個人との頻繁な接触に依存す るからだ。[81] このような集団で病原体が持続するには、慢性感染となるか、あるいは感染した宿主内で長期間存在し感染力を維持するか、あるいは他の追加的な宿主種を保菌 宿主として維持し、新たな感受性宿主と接触して感染させる必要があった。[82][83] 実際、多くの「ヒト」疾患において、ヒトは偶然の被害者あるいは最終宿主と見なす方が適切である。例としては狂犬病、炭疽、野兎病、ウエストナイル熱が挙 げられる。したがって、人間が感染性疾患に曝される多くのケースは人獣共通感染症によるものである。[84]  人獣共通感染症伝播の可能性 多くの疾患、流行性疾患でさえも人獣共通起源を持ち、麻疹、天然痘、インフルエンザ、HIV、ジフテリアが特に顕著な例である。[85][86] 風邪や結核の様々な形態も、他の種に由来する株が適応したものだ。[87][88] 一部の専門家は、ヒトのウイルス感染は全て元々は人獣共通感染だったと示唆している。[89] 人獣共通感染症が注目されるのは、それらがしばしばこれまで認識されていなかった疾患であるか、免疫を持たない集団において病原性が増強されるためだ。ウ エストナイルウイルスは1999年、米国ニューヨーク市周辺で初めて確認された。腺ペストは人獣共通感染症であり[90]、サルモネラ症、ロッキー山紅斑 熱、ライム病も同様である。 ヒト集団における新たな人獣共通病原体の出現に寄与する主要因は、ヒトと野生生物の接触増加である[91]。これは人間の活動が自然地域に侵入するか、野 生動物が人間の活動地域に移動することで引き起こされる。1999年にマレーシア半島で発生したニパウイルス感染症がその例だ。感染したフルーツコウモリ の生息域内で集約的な養豚が始まったことが原因である[92]。これらの豚における未特定感染が感染力を増幅させ、ウイルスが農家に伝播し、最終的に 105人の死者を出した。[93] 同様に近年では、鳥インフルエンザやウエストナイルウイルスが、おそらく媒介宿主と家畜との相互作用により、ヒト集団へ波及している。[94]コウモリや 鳥類のような移動性の高い動物は、人間の居住地域へ容易に移動できるため、他の動物よりも人獣共通感染症伝播のリスクが高い可能性がある。 ライフサイクルの一部をヒト宿主に依存する[95]ため、アフリカ住血吸虫症、河川盲目症、象皮病などの疾患は、昆虫や他の媒介生物による伝播に依存する可能性があるにもかかわらず、人獣共通感染症とは定義されない。[出典が必要] |

| Use in vaccines The first vaccine against smallpox by Edward Jenner in 1800 was by infection of a zoonotic bovine virus which caused a disease called cowpox.[96] Jenner had noticed that milkmaids were resistant to smallpox. Milkmaids contracted a milder version of the disease from infected cows that conferred cross immunity to the human disease. Jenner abstracted an infectious preparation of 'cowpox' and subsequently used it to inoculate persons against smallpox. As a result of vaccination, smallpox has been eradicated globally, and mass inoculation against this disease ceased in 1981.[97] There are a variety of vaccine types, including traditional inactivated pathogen vaccines, subunit vaccines, live attenuated vaccines. There are also new vaccine technologies such as viral vector vaccines and DNA/RNA vaccines, which include many of the COVID-19 vaccines.[98] |

ワクチンへの応用 1800年にエドワード・ジェンナーが開発した最初の天然痘ワクチンは、牛痘と呼ばれる病気を引き起こす人獣共通牛ウイルスによる感染を利用したものであ る。[96] ジェンナーは、搾乳婦が天然痘に抵抗性を持つことに気づいた。搾乳婦は感染した牛からより軽度の病気を感染し、それがヒトの病気に対する交差免疫をもたら したのである。ジェンナーは「牛痘」の感染性製剤を抽出し、その後これを用いて人々に天然痘予防接種を行った。このワクチン接種の結果、天然痘は世界的に 根絶され、この病気に対する集団予防接種は1981年に終了した[97]。ワクチンには様々な種類があり、従来の不活化病原体ワクチン、サブユニットワク チン、弱毒生ワクチンなどが含まれる。また、ウイルスベクターワクチンやDNA/RNAワクチンといった新たなワクチン技術も存在する。これには多くの COVID-19ワクチンが含まれる。[98] |

| List of zoonotic diseases |

人獣共通感染症の一覧 |

| Animal welfare#Animal welfare organizations – Well-being of non-human animals Conservation medicine Cross-species transmission – Transmission of a pathogen between different species Emerging infectious disease – Infectious disease of emerging pathogen, often novel in its outbreak range or transmission mode Foodborne illness – Illness from eating spoiled or contaminated food Spillover infection – Occurs when a reservoir population causes an epidemic in a novel host population Wildlife disease Veterinary medicine – Branch of medicine for non-human animals Wildlife smuggling and zoonoses – Health risks associated with the trade in exotic wildlife List of zoonotic primate viruses |

動物福祉#動物福祉団体 – 非人間動物の福祉 保全医学 種間感染 – 異なる種間での病原体の伝播 新興感染症 – 新たな病原体による感染症。発生範囲や感染経路が新規であることが多い 食中毒 – 腐敗した食品や汚染された食品を摂取することで起こる病気 スピルオーバー感染 – 貯蔵宿主集団が新たな宿主集団で流行を引き起こす際に発生する 野生動物疾病 獣医学 – 非人間動物を対象とする医学の一分野 野生動物密輸と人獣共通感染症 – 希少野生動物取引に伴う健康リスク 霊長類人獣共通ウイルス一覧 |

| Bibliography Bardosh K (2016). One Health: Science, Politics and Zoonotic Disease in Africa. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-96148-7.. Crawford D (2018). Deadly Companions: How Microbes Shaped our History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-881544-0. Felbab-Brown V (6 October 2020). "Preventing the next zoonotic pandemic". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021. Greger M (2007). "The human/animal interface: emergence and resurgence of zoonotic infectious diseases". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 33 (4): 243–299. doi:10.1080/10408410701647594. PMID 18033595. S2CID 8940310. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020. H. Krauss, A. Weber, M. Appel, B. Enders, A. v. Graevenitz, H. D. Isenberg, H. G. Schiefer, W. Slenczka, H. Zahner: Zoonoses. Infectious Diseases Transmissible from Animals to Humans. 3rd Edition, 456 pages. ASM Press. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C., 2003. ISBN 1-55581-236-8. González JG (2010). Infection Risk and Limitation of Fundamental Rights by Animal-To-Human Transplantations. EU, Spanish and German Law with Special Consideration of English Law (in German). Hamburg: Verlag Dr. Kovac. ISBN 978-3-8300-4712-4. Quammen D (2013). Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-34661-9. |

参考文献 Bardosh K (2016). 『ワン・ヘルス:アフリカにおける科学、政治、人獣共通感染症』. ロンドン:Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-96148-7. Crawford D (2018). 『致死的な共生者:微生物が歴史を形作った方法』. オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-881544-0. フェルバブ=ブラウン V (2020年10月6日). 「次なる人獣共通感染症のパンデミックを防ぐ」. ブルッキングス研究所. 2021年1月21日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2021年1月19日に閲覧. グレガー M (2007). 「ヒトと動物の接点:人獣共通感染症の出現と再興」. クリティカル・レビューズ・イン・マイクロバイオロジー. 33 (4): 243–299. doi:10.1080/10408410701647594. PMID 18033595。S2CID 8940310。2020年8月1日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2020年9月29日に取得。 H. Krauss、A. ヴェーバー、M. アペル、B. エンダース、A. v. グレーヴェニッツ、H. D. アイゼンバーグ、H. G. シーファー、W. スレンツカ、H. ザーナー:人獣共通感染症。動物から人間に感染する感染症。第 3 版、456 ページ。ASM Press。米国微生物学会、ワシントン D.C.、2003 年。ISBN 1-55581-236-8。 González JG (2010)。動物から人間への移植による感染リスクと基本的人権の制限。EU、スペイン、ドイツの法律、特に英国の法律について(ドイツ語)。ハンブルク:Verlag Dr. Kovac。ISBN 978-3-8300-4712-4。 クアメン D (2013). 『スピルオーバー:動物感染と次なる人類のパンデミック』. W. W. ノートン・アンド・カンパニー. ISBN 978-0-393-34661-9. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zoonosis |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099