ワシントン・コンセンサス

Washington Consensus

☆

ワシントン・コンセンサスとは、1980年代から1990年代にかけて、ワシントンD.C.に本拠を置く国際通貨基金(IMF)、世界銀行、米国財務省

が、危機に瀕した発展途上国に対して推進した「標準的な」改革パッケージを構成する10の経済政策処方箋である。[1]

この用語は、1989年にイギリスの経済学者ジョン・ウィリアムソンによって初めて使用された。[2]

この処方箋には、貿易自由化、民営化、金融自由化などの自由市場促進政策が含まれていた。[3][4]

また、財政赤字とインフレを最小限に抑えることを目的とした財政政策と金融政策も伴っていた。[4]

ウィリアムソンがこの用語を使用した後、彼の強い反対にもかかわらず、「ワシントン・コンセンサス」という表現は、より広範な第二の意味で、強い市場主義

的アプローチ(市場原理主義や新自由主義とも呼ばれる)に対するより一般的な方向性を指すために、かなり広く使用されるようになった。2つの異なる定義の

相違の大きさを強調して、ウィリアムソンは、彼の10の狭義の処方箋は、ほぼ「母性愛とアップルパイ」のような地位(すなわち、広く当然のこととみなされ

る)を獲得した一方で、その後のより広義の定義は、新自由主義の宣言の一形態であり、「(ワシントンでも)他のどこでも合意を得ることがなかった」と主張

している。

ワシントン・コンセンサスに関する議論は、長い間論争の的となっている。これは、この用語の意味について合意が得られていないことを部分的に反映している

が、関連する政策処方箋のメリットと結果についても実質的な意見の相違がある。一部の批評家は、開発途上国の世界市場への開放と新興市場への移行を強調し

た当初のコンセンサスに異議を唱えている。彼らは、国内市場の影響力強化に過度に重点が置かれ、国家の重要な機能に影響を与えるガバナンスが犠牲になって

いると主張している。他の論者にとっては、問題はむしろ欠落している点にある。具体的には、制度構築や、機会均等・社会的公正・貧困削減を通じて社会で最

も弱い立場にある人々の機会を改善するための的を絞った取り組みといった分野が挙げられる。

| The Washington

Consensus is a set of ten economic policy prescriptions considered in

the 1980s and 1990s to constitute the "standard" reform package

promoted for crisis-wracked developing countries by the Washington,

D.C.-based institutions the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World

Bank and United States Department of the Treasury.[1] The term was

first used in 1989 by English economist John Williamson.[2] The

prescriptions encompassed free-market promoting policies such as trade

liberalization, privatization and finance liberalization.[3][4] They

also entailed fiscal and monetary policies intended to minimize fiscal

deficits and minimize inflation.[4] Subsequent to Williamson's use of the terminology, and despite his emphatic opposition, the phrase Washington Consensus has come to be used fairly widely in a second, broader sense, to refer to a more general orientation towards a strongly market-based approach (sometimes described as market fundamentalism or neoliberalism). In emphasizing the magnitude of the difference between the two alternative definitions, Williamson has argued[a] that his ten original, narrowly defined prescriptions have largely acquired the status of "motherhood and apple pie" (i.e., are broadly taken for granted), whereas the subsequent broader definition, representing a form of neoliberal manifesto, "never enjoyed a consensus [in Washington] or anywhere much else" and can reasonably be said to be dead. Discussion of the Washington Consensus has long been contentious. Partly this reflects a lack of agreement over what is meant by the term, but there are also substantive differences over the merits and consequences of the policy prescriptions involved. Some critics take issue with the original Consensus's emphasis on the opening of developing countries to the global marketplace and transitioning to an emerging market in what they see as an excessive focus on strengthening the influence of domestic market forces, arguably at the expense of governance which will affect key functions of the state. For other commentators, the issue is more what is missing, including such areas as institution-building and targeted efforts to improve opportunities for the weakest in society through equal opportunity, social justice and poverty reduction.  Desaturated red globe, designed as a kind of logo for neoliberalism |

ワシントン・コンセンサスとは、1980年代から1990年代にかけ

て、ワシントンD.C.に本拠を置く国際通貨基金(IMF)、世界銀行、米国財務省が、危機に瀕した発展途上国に対して推進した「標準的な」改革パッケー

ジを構成する10の経済政策処方箋である。[1]

この用語は、1989年にイギリスの経済学者ジョン・ウィリアムソンによって初めて使用された。[2]

この処方箋には、貿易自由化、民営化、金融自由化などの自由市場促進政策が含まれていた。[3][4]

また、財政赤字とインフレを最小限に抑えることを目的とした財政政策と金融政策も伴っていた。[4] ウィリアムソンがこの用語を使用した後、彼の強い反対にもかかわらず、「ワシントン・コンセンサス」という表現は、より広範な第二の意味で、強い市場主義 的アプローチ(市場原理主義や新自由主義とも呼ばれる)に対するより一般的な方向性を指すために、かなり広く使用されるようになった。2つの異なる定義の 相違の大きさを強調して、ウィリアムソンは、彼の10の狭義の処方箋は、ほぼ「母性愛とアップルパイ」のような地位(すなわち、広く当然のこととみなされ る)を獲得した一方で、その後のより広義の定義は、新自由主義の宣言の一形態であり、「(ワシントンでも)他のどこでも合意を得ることがなかった」と主張 している。 ワシントン・コンセンサスに関する議論は、長い間論争の的となっている。これは、この用語の意味について合意が得られていないことを部分的に反映している が、関連する政策処方箋のメリットと結果についても実質的な意見の相違がある。一部の批評家は、開発途上国の世界市場への開放と新興市場への移行を強調し た当初のコンセンサスに異議を唱えている。彼らは、国内市場の影響力強化に過度に重点が置かれ、国家の重要な機能に影響を与えるガバナンスが犠牲になって いると主張している。他の論者にとっては、問題はむしろ欠落している点にある。具体的には、制度構築や、機会均等・社会的公正・貧困削減を通じて社会で最 も弱い立場にある人々の機会を改善するための的を絞った取り組みといった分野が挙げられる。  新自由主義のロゴのようなものとして(wikiによって)デザインされた、彩度の低い赤い球体 |

| History Original sense: Williamson's Ten Points The concept and name of the Washington Consensus were first presented in 1989 by John Williamson, an economist from the Institute for International Economics, an international economic think tank based in Washington, D.C.[5] The consensus as originally stated by Williamson included ten broad sets of relatively specific policy recommendations:[1][3] 1. Fiscal policy discipline, with avoidance of large fiscal deficits relative to GDP; 2. Redirection of public spending from subsidies ("especially indiscriminate subsidies") toward broad-based provision of key pro-growth, pro-poor services like primary education, primary health care and infrastructure investment; 3. Tax reform, broadening the tax base and adopting moderate marginal tax rates; 4. Interest rates that are market determined and positive (but moderate) in real terms; 5. Competitive exchange rates; 6. Trade liberalization: liberalization of imports, with particular emphasis on elimination of quantitative restrictions (licensing, etc.); any trade protection to be provided by low and relatively uniform tariffs; 7. Liberalization of inward foreign direct investment; 8. Privatization of state enterprises; 9. Deregulation: abolition of regulations that impede market entry or restrict competition, except for those justified on safety, environmental and consumer protection grounds, and prudential oversight of financial institutions; 10. Legal security for property rights. |

歴史 本来の意味:ウィリアムソンの10項目 ワシントン・コンセンサスの概念と名称は、1989年にワシントンD.C.に拠点を置く国際経済シンクタンク、国際経済研究所の経済学者ジョン・ウィリアムソンによって初めて提唱された[5]。 ウィリアムソンが当初述べたコンセンサスには、10の比較的具体的な政策提言が含まれていた[1][3]。 1. 財政政策の規律、GDP に対する大きな財政赤字の回避 2. 補助金(「特に無差別的な補助金」)から、初等教育、初等健康、インフラ投資など、成長促進と貧困層支援に資する幅広いサービスへの公共支出の転換 3. 税制改革、課税ベースの拡大、適度な限界税率の採用 4. 市場で決定され、実質ベースでプラス(ただし緩やかな)金利。 5. 競争力のある為替レート。 6. 貿易自由化:輸入の自由化、特に数量制限(ライセンスなど)の撤廃を重視。貿易保護は、低くて比較的均一な関税によって行う。 7. 対内直接投資の自由化。 8. 国有企業の民営化 9. 規制緩和:市場参入を阻害したり競争を制限する規制の廃止。ただし安全・環境・消費者保護上の理由による規制、及び金融機関の健全性監督は除く 10. 財産権の法的保障 |

| Origins of policy agenda Although Williamson's label of the Washington Consensus draws attention to the role of the Washington-based agencies in promoting the above agenda, a number of authors have stressed that Latin American policy-makers arrived at their own packages of policy reforms primarily based on their own analysis of their countries' situations. Thus, according to Joseph Stanislaw and Daniel Yergin, authors of The Commanding Heights, the policy prescriptions described in the Washington Consensus were "developed in Latin America, by Latin Americans, in response to what was happening both within and outside the region."[6] Joseph Stiglitz has written that "the Washington Consensus policies were designed to respond to the very real problems in Latin America and made considerable sense" (though Stiglitz has at times been an outspoken critic of IMF policies as applied to developing nations).[7] In view of the implication conveyed by the term Washington Consensus that the policies were largely external in origin, Stanislaw and Yergin report that the term's creator, John Williamson, has "regretted the term ever since", stating "it is difficult to think of a less diplomatic label."[6] Williamson regretted the use of "Washington" in the Washington Consensus, as it incorrectly suggested that development policies stemmed from Washington and were externally imposed on others.[8] Williamson said in 2002, "The phrase "Washington Consensus" is a damaged brand name... Audiences the world over seem to believe that this signifies a set of neoliberal policies that have been imposed on hapless countries by the Washington-based international financial institutions and have led them to crisis and misery. There are people who cannot utter the term without foaming at the mouth. My own view is of course quite different. The basic ideas that I attempted to summarize in the Washington Consensus have continued to gain wider acceptance over the past decade, to the point where Lula has had to endorse most of them in order to be electable. For the most part they are motherhood and apple pie, which is why they commanded a consensus."[9] According to a 2011 study by Nancy Birdsall, Augusto de la Torre, and Felipe Valencia Caicedo, the policies in the original consensus were largely a creation of Latin American politicians and technocrats, with Williamson's role having been to gather the ten points in one place for the first time, rather than to "create" the package of policies.[10] Kate Geohegan of Harvard University's Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies credited Peruvian neoliberal economist Hernando de Soto for inspiring the Washington Consensus.[11] Williamson partly credited de Soto himself for the prescriptions, saying his work was "the outcome of the worldwide intellectual trends to which Latin America provided" and said that de Soto was directly responsible for the recommendation on legal security for property rights.[11] |

政策課題の起源 ウィリアムソンが「ワシントン・コンセンサス」と命名したことで、上記の課題の推進におけるワシントンに拠点を置く機関の役割が注目されるようになった が、多くの著者は、ラテンアメリカの政策立案者たちが、自国の状況に関する独自の分析に基づいて、独自の政策改革パッケージを策定したと強調している。し たがって、『The Commanding Heights』の著者であるジョセフ・スタニスラウとダニエル・ヤーギンによれば、ワシントン・コンセンサスで述べられている政策処方箋は、「ラテンア メリカ内外で起こっていた事態に対応するために、ラテンアメリカ人自身によってラテンアメリカで開発された」ものである。[6] ジョセフ・スティグリッツは、「ワシントン・コンセンサスの政策は、ラテンアメリカの非常に現実的な問題に対応するために設計され、非常に理にかなってい た」と書いている(ただし、スティグリッツは、開発途上国民に適用される IMF の政策を率直に批判してきたこともある)。[7] ワシントン・コンセンサスという用語が、その政策は主に外部から持ち込まれたものであるという含意を伝えていることを踏まえ、スタニスラフとヤーギンは、 この用語の創始者であるジョン・ウィリアムソンが「それ以来、この用語を後悔している」と報告し、「これほど外交的でない名称は考えにくい」と述べてい る。[6] ウィリアムソンは、ワシントン・コンセンサスに「ワシントン」という語が使われていることを後悔していた。この語は、開発政策がワシントンに由来し、外部 から他国に押し付けられたものであると誤って示唆していたからだ。ウィリアムソンは 2002 年に、「ワシントン・コンセンサスという語は、傷ついたブランド名である」と述べた。世界中の聴衆は、この言葉が、ワシントンに拠点を置く国際金融機関に よって不運な国々に押し付けられ、それらを危機と悲惨に陥れた一連の新自由主義政策を意味すると信じているようだ。この言葉を口にするだけで口角泡を飛ば す人々もいる。もちろん、私自身の見解はまったく異なる。ワシントン・コンセンサスで私が要約しようとした基本的な考え方は、この 10 年間でより広く受け入れられるようになり、ルラ大統領でさえ、選挙で当選するためにそのほとんどを支持せざるを得なかったほどだ。その大部分は、母性愛や アップルパイのような、誰もが当然と思うようなことであり、だからこそコンセンサスを得ることができたのだ」[9] ナンシー・バーズオール、アウグスト・デ・ラ・トーレ、フェリペ・バレンシア・カイセドによる 2011 年の研究によると、当初のコンセンサスにおける政策は、主にラテンアメリカの政治家やテクノクラートによって作成されたものであり、ウィリアムソンの役割 は、一連の政策を「作成」したのではなく、10 のポイントを初めて 1 か所にまとめたことだった。[10] ハーバード大学デイヴィス・ロシア・ユーラシア研究センターのケイト・ジオヘガンは、ペルーの新自由主義経済学者エルナンド・デ・ソトがワシントン・コン センサスに影響を与えたと評価している。[11] ウィリアムソンは、その処方箋について、デ・ソト自身の功績も一部あると評価し、彼の研究は「ラテンアメリカが提供した世界的な知的潮流の成果」であり、 財産権の法的安定性に関する提言についてはデ・ソトが直接の責任者であると述べている。[11] |

| Broad sense The Washington Consensus is not interchangeable with the term "neoliberalism."[3] Williamson recognizes that the term has commonly been used with a different meaning from his original prescription; he opposes the alternative use of the term, which became common after his initial formulation, to cover a broader market fundamentalism or "neoliberal" agenda.[12] I of course never intended my term to imply policies like capital account liberalization (...I quite consciously excluded that), monetarism, supply-side economics, or a minimal state (getting the state out of welfare provision and income redistribution), which I think of as the quintessentially neoliberal ideas. If that is how the term is interpreted, then we can all enjoy its wake, although let us at least have the decency to recognize that these ideas have rarely dominated thought in Washington and certainly never commanded a consensus there or anywhere much else...[9] — John Williamson, Did the Washington Consensus Fail? More specifically, Williamson argues that the first three of his ten prescriptions are uncontroversial in the economic community, while recognizing that the others have evoked some controversy. He argues that one of the least controversial prescriptions, the redirection of spending to infrastructure, health care, and education, has often been neglected. He also argues that, while the prescriptions were focused on reducing certain functions of government (e.g., as an owner of productive enterprises), they would also strengthen government's ability to undertake other actions such as supporting education and health. Williamson says that he does not endorse market fundamentalism, and believes that the Consensus prescriptions, if implemented correctly, would benefit the poor.[13] In a book edited with Pedro-Pablo Kuczynski in 2003, Williamson laid out an expanded reform agenda, emphasizing crisis-proofing of economies, "second-generation" reforms, and policies addressing inequality and social issues.[14] As noted, in spite of Williamson's reservations, the term Washington Consensus has been used more broadly to describe the general shift towards free market policies that followed the displacement of Keynesianism in the 1970s. In this broad sense the Washington Consensus is sometimes considered to have begun at about 1980.[15][16] Many commentators see the consensus, especially if interpreted in the broader sense of the term, as having been at its strongest during the 1990s. Some have argued that the consensus in this sense ended at the turn of the century, or at least that it became less influential after about the year 2000.[10][17] More commonly, commentators have suggested that the Consensus in its broader sense survived until the 2008 financial crisis.[16] Following the 2008–2009 Keynesian resurgence undertaken by governments in response to market failures, a number of journalists, politicians and senior officials from global institutions such as the World Bank began saying that the Washington Consensus was dead.[18][19] These included former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, who following the 2009 G-20 London summit, declared "the old Washington Consensus is over".[20] Williamson was asked by The Washington Post in April 2009 whether he agreed with Gordon Brown that the Washington Consensus was dead. He responded: It depends on what one means by the Washington Consensus. If one means the ten points that I tried to outline, then clearly it's not right. If one uses the interpretation that a number of people—including Joe Stiglitz, most prominently—have foisted on it, that it is a neoliberal tract, then I think it is right.[21] After the 2010 G-20 Seoul summit announced that it had achieved agreement on a Seoul Development Consensus, the Financial Times editorialized that "Its pragmatic and pluralistic view of development is appealing enough. But the document will do little more than drive another nail into the coffin of a long-deceased Washington consensus."[22] |

広い意味 ワシントン・コンセンサスは「新自由主義」という用語と互換性があるわけではない[3]。ウィリアムソンは、この用語が彼の当初の定義とは異なる意味で一 般的に使用されていることを認識している。彼は、この用語が彼の最初の定義後に一般的になった、より広範な市場原理主義や「新自由主義」の政策を網羅する 代替的な使用法に反対している。[12] もちろん、私の用語が、資本勘定の自由化(...私はそれを意識的に除外した)、金融政策、供給側経済学、あるいは最小限の国家(福祉の提供や所得の再分 配から国家を排除すること)といった政策を意味することを意図したことは決してない。もしその用語がそう解釈されるのであれば、我々は皆その余波を楽しむ ことができるだろう。ただし、少なくとも、これらの考え方がワシントンで支配的な思想となったことはほとんどなく、ワシントンでも、その他の場所でも、決 して合意を形成したことはなかったという事実を認識する良識は持っておくべきである... [9] — ジョン・ウィリアムソン、ワシントン・コンセンサスは失敗したか? より具体的には、ウィリアムソンは、彼の10の処方箋のうち最初の3つは経済界では議論の余地がないと主張する一方で、他の処方箋はいくつかの論争を引き 起こしていることを認めている。彼は、最も論争の少ない処方箋の一つである、インフラ、健康、教育への支出の方向転換は、しばしば軽視されてきたと主張す る。また、処方箋は政府の特定の機能(例えば、生産的企業の所有者としての機能)の削減に焦点を当てていたが、教育や健康の支援など、他の行動を取る政府 の能力も強化するだろうとも主張している。ウィリアムソンは、市場原理主義を支持しておらず、コンセンサスの処方箋は、正しく実施されれば、貧困層にも利 益をもたらすだろうと考えている。[13] 2003年にペドロ・パブロ・クチンスキーと共同編集した著書の中で、ウィリアムソンは、経済の危機耐性、「第二世代」の改革、不平等や社会問題に対処す る政策を強調し、改革の課題を広げた。[14] 前述のように、ウィリアムソンの留保にもかかわらず、「ワシントン・コンセンサス」という用語は、1970年代にケインズ主義が退いた後に起こった自由市 場政策への一般的な移行を表すために、より広く使用されてきた。この広い意味でのワシントン・コンセンサスは、1980年頃に始まったとみなされることも ある。[15][16] 多くの評論家は、特にこの用語の広い意味で解釈した場合、このコンセンサスは1990年代に最も強力だったとみなしている。この意味でのコンセンサスは、 世紀の変わり目に終焉を迎えた、あるいは少なくとも2000年頃以降、その影響力は弱まったと主張する者もいる。[10][17] より一般的には、より広い意味でのコンセンサスは 2008 年の金融危機まで存続していたと論評されている。[16] 市場の失敗に対応して各国政府が 2008 年から 2009 年にかけてケインズ主義を復活させたことを受け、多くのジャーナリスト、政治家、世界銀行などの国際機関の高官たちが、ワシントン・コンセンサスは死んだ と主張し始めた。[18][19] 2009年のG20ロンドンサミットの後、「旧ワシントン・コンセンサスは終わった」と宣言したゴードン・ブラウン元英国首相もその一人である。[20] 2009年4月、ワシントン・ポスト紙はウィリアムソンに、ワシントン・コンセンサスは死んだというゴードン・ブラウンの見解に同意するか尋ねた。彼は次 のように答えた。 それは、ワシントン・コンセンサスをどういう意味で捉えるかによる。私が概説しようとした 10 項目を意味するのであれば、明らかにそれは正しくない。ジョー・スティグリッツをはじめとする多くの人々が押し付けた解釈、つまり新自由主義の書物である という意味で捉えるのであれば、それは正しいと思う。[21] 2010年のG20ソウルサミットが「ソウル開発コンセンサス」の合意達成を発表した後、フィナンシャル・タイムズ紙は社説でこう論じた。「その現実的で 多元的な開発観は十分に魅力的だ。しかしこの文書は、とっくに死んだワシントン・コンセンサスの棺桶に、もう一本の釘を打つ以上のことはしないだろう」 [22] |

| Context The widespread adoption by governments of the Washington Consensus was to a large degree a reaction to the macroeconomic crisis that hit much of Latin America, and some other developing regions, during the 1980s. The crisis had multiple origins: the drastic rise in the price of imported oil following the emergence of OPEC, mounting levels of external debt, the rise in US (and hence international) interest rates, and—consequent to the foregoing problems—loss of access to additional foreign credit. The import-substitution policies that had been pursued by many developing country governments in Latin America and elsewhere for several decades had left their economies ill-equipped to expand exports at all quickly to pay for the additional cost of imported oil (by contrast, many countries in East Asia, which had followed more export-oriented strategies, found it comparatively easy to expand exports still further, and as such managed to accommodate the external shocks with much less economic and social disruption). Unable either to expand external borrowing further or to ramp up export earnings easily, many Latin American countries faced no obvious sustainable alternatives to reducing overall domestic demand via greater fiscal discipline, while in parallel adopting policies to reduce protectionism and increase their economies' export orientation.[23] Many countries have endeavored to implement varying components of the reform packages, the implementation sometimes being a condition for receiving loans from the IMF and World Bank.[15] |

文脈 ワシントン・コンセンサスが各国政府に広く採用されたのは、1980年代にラテンアメリカやその他の発展途上地域を襲ったマクロ経済危機への反応が大きな 要因であった。この危機には複数の原因があった。OPECの台頭に伴う輸入石油価格の急騰、対外債務の累積、米国(ひいては国際)金利の上昇、そしてこれ らに起因する追加的な対外信用へのアクセス喪失である。ラテンアメリカをはじめとする多くの途上国政府が数十年にわたり推進してきた輸入代替政策は、輸入 石油の追加コストを賄うために輸出を迅速に拡大する経済基盤を全く整えられなかった(対照的に、より輸出志向型の戦略を取った東アジアの多くの国々は、輸 出をさらに拡大することが比較的容易であり、その結果、はるかに少ない経済的・社会的混乱で外部ショックに対応できた)。対外借入をさらに拡大すること も、輸出収益を容易に増大させることもできなかった多くのラテンアメリカ諸国は、財政規律の強化を通じて国内総需要を削減する以外に、持続可能な選択肢が 明らかに存在しなかった。同時に、保護主義を削減し、経済の輸出志向性を高める政策を採用する必要があった。[23] 多くの国々が改革パッケージの様々な要素の実施に努めてきた。その実施は、IMFや世界銀行からの融資を受ける条件となる場合もあった。[15] |

| Effects According to a 2020 study, the implementation of policies associated with the Washington Consensus significantly raised real GDP per capita over a 5- to 10-year horizon.[24] According to a 2021 study, the implementation of the Washington Consensus in Brazil, Chile, and Mexico had "mixed results": "macroeconomic stability is much improved, but economic growth has been heterogeneous and generally disappointing, despite improvement relative to the 1980s."[25] Another 2021 study found that the implementation of the Washington Consensus in sub-Saharan Africa led to "initial declines in per capita economic growth over the 1980s and 1990s" but "notable increases in per capita real GDP growth in the post–2000 period."[26] The study found that "the ability to implement pro-poor policies alongside market-oriented reforms played a central role in successful policy performance."[26] Williamson has summarized the overall results on growth, employment and poverty reduction in many countries as "disappointing, to say the least". He attributed this limited impact to three factors: (a) the Consensus per se placed no special emphasis on mechanisms for avoiding economic crises, which proved very damaging; (b) the reforms—both those listed in his article and, a fortiori, those actually implemented—were incomplete; and (c) the reforms cited were insufficiently ambitious with respect to targeting improvements in income distribution, and need to be complemented by stronger efforts in this direction. Rather than an argument for abandoning the original ten prescriptions, though, Williamson concludes that they are "motherhood and apple pie" and "not worth debating".[9] |

効果 2020年の研究によれば、ワシントン・コンセンサスに関連する政策の実施は、5年から10年の期間において実質一人当たりGDPを大幅に押し上げた。 [24] 2021年の研究によれば、ブラジル、チリ、メキシコにおけるワシントン・コンセンサスの実施は「結果が混血の」であった。「マクロ経済の安定性は大幅に 改善されたが、経済成長は不均一で、1980年代に比べれば改善したとはいえ、全体的には期待外れだった」。[25] 別の2021年の研究では、サハラ以南のアフリカにおけるワシントン・コンセンサスの実施は、「1980年代および1990年代には一人当たりの経済成長 が当初低下した」が、「2000年以降は一人当たりの実質GDP成長が著しく増加した」と結論づけている。[26] この研究は、「市場志向の改革と並行して貧困層支援政策を実施できる能力が、政策の成功に重要な役割を果たした」と結論づけている。[26] ウィリアムソンは、多くの国々における成長、雇用、貧困削減に関する全体的な結果を「控えめに言っても期待外れ」と総括している。彼は、この限定的な影響 を 3 つの要因に起因すると考えている。(a) コンセンサス自体は、経済危機を回避するためのメカニズムを特に重視しておらず、それが非常に大きな損害をもたらした。(b) 彼の論文に挙げられた改革、そして当然のことながら実際に実施された改革は、不完全であった。(c) 引用された改革は、所得分配の改善を目標とする点で野心的さに欠けており、この方向性におけるより強力な取り組みによって補完される必要がある。しかし、 ウィリアムソンは、当初の 10 の処方箋を放棄すべきだと主張するのではなく、それらは「当然のこと」であり、「議論する価値もない」と結論づけている。[9] |

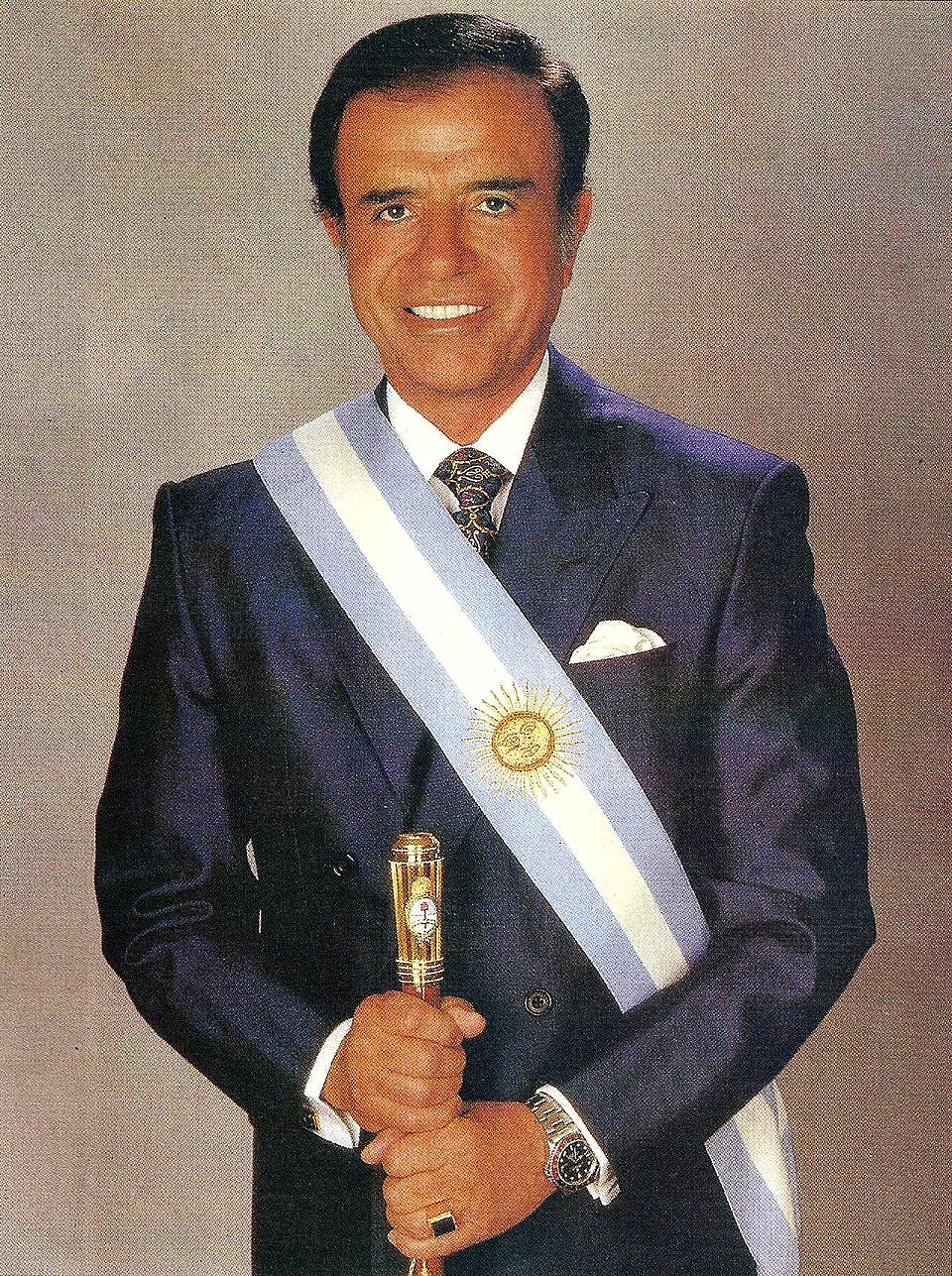

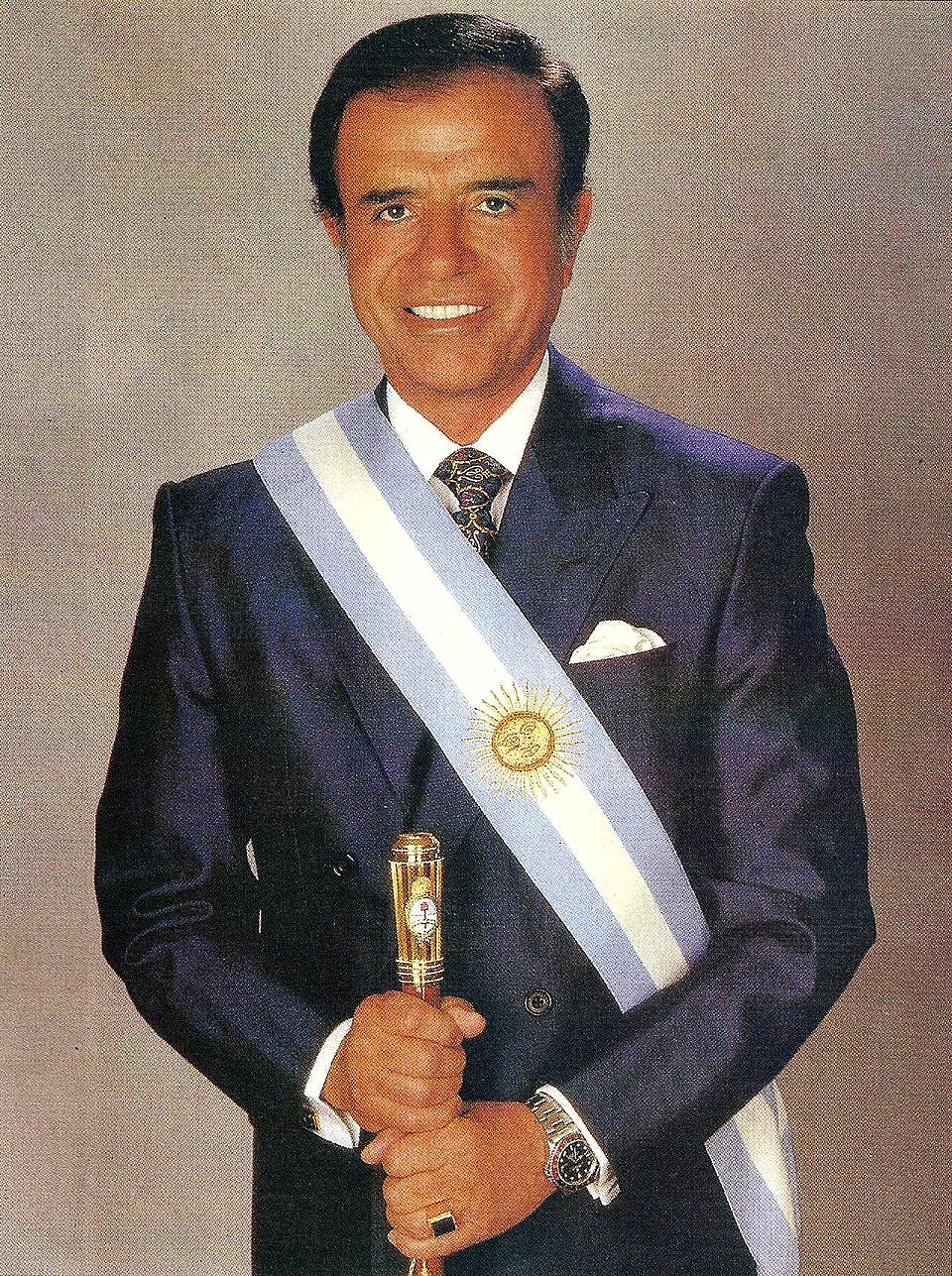

| Latin America The Washington Consensus resulted with the La Década Perdida or "The Lost Decade" in Latin America, when many nations in the region faced sovereign debt crises.[27] It has been argued that the Washington Consensus resulted in socioeconomic exclusion and weakened trade unions in Latin America, resulting with unrest in the region.[28][29] Countries who followed the consensus initially alleviated high inflation and excessive regulation, though economic growth and poverty relief was insignificant.[30] The consensus resulted with a shrinking middle class in Latin America that prompted dissatisfaction of neoliberalism, a turn to the political left and populist leaders by the late-1990s, with economists saying that the consensus established support for Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Evo Morales in Bolivia and Rafael Correa in Ecuador.[4][29][30] Argentina See also: Argentine debt restructuring  Argentine President Carlos Menem The Argentine economic crisis of 1999–2002 is held out as an example of the economic consequences said by some to have been wrought by application of the Washington Consensus. In October 1998, the IMF invited Argentine President Carlos Menem, to talk about the successful Argentine experience, at the Annual Meeting of the Board of Governors.[31] President Menem's Minister of Economy (1991–1996), Domingo Cavallo, the architect of the Menem administration's economic policies, specifically including "convertibility", said: On the second semester of 1998 Argentina was considered in Washington the most successful economy among the ones that had restructured its debt within the Brady's Plan framework. None of the Washington Consensus' sponsors were interested in pointing out that the Argentine economic reforms had differences with its 10 recommendations. On the contrary, Argentina was considered the best pupil of the IMF, the World Bank and the USA government.[32] The problems which arise with reliance on a fixed exchange rate mechanism (above) are discussed in the World Bank report Economic Growth in the 1990s: Learning from a Decade of Reform, which questions whether expectations can be "positively affected by tying a government's hands". In the early 1990s there was a point of view that countries should move to either fixed or completely flexible exchange rates to reassure market participants of the complete removal of government discretion in foreign exchange matters. After the Argentina collapse, some observers believe that removing government discretion by creating mechanisms that impose large penalties may, on the contrary, actually itself undermine expectations. Velasco and Neut (2003)[33] "argue that if the world is uncertain and there are situations in which the lack of discretion will cause large losses, a precommitment device can actually make things worse".[34] In chapter 7 of its report (Financial Liberalization: What Went Right, What Went Wrong?) the World Bank analyses what went wrong in Argentina, summarizes the lessons from the experience, and draws suggestions for its future policy.[34] The IMF's Independent Evaluation Office has issued a review of the lessons of Argentina for the institution, summarized in the following quotation: The Argentine crisis yields a number of lessons for the IMF, some of which have already been learned and incorporated into revised policies and procedures. This evaluation suggests ten lessons, in the areas of surveillance and program design, crisis management, and the decision-making process.[35] While President Néstor Kirchner's reliance on price controls and similar administrative measures (often aimed primarily at foreign-invested firms such as utilities) clearly ran counter to the spirit of the Consensus, his administration in fact ran an extremely tight fiscal ship and maintained a highly competitive floating exchange rate; Argentina's immediate bounce-back from crisis, further aided by abrogating its debts and a fortuitous boom in prices of primary commodities, leaves open issues of longer-term sustainability.[36] The Economist has argued that the Néstor Kirchner administration will end up as one more in Argentina's long history of populist governments.[37] In October 2008, Kirchner's wife and successor as president, Cristina Kirchner, announced her government's intention to nationalize pension funds from the privatized system implemented by Menem-Cavallo.[38] Accusations have emerged of the manipulation of official statistics under the Kirchners (most notoriously, for inflation) to create an inaccurately positive picture of economic performance.[39] The Economist removed Argentina's inflation measure from its official indicators, saying that they were no longer reliable.[40] In 2003, Argentina's and Brazil's presidents, Néstor Kirchner and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, signed the "Buenos Aires Consensus", a manifesto opposing the Washington Consensus' policies.[41] Skeptical political observers note, however, that Lula's rhetoric on such public occasions should be distinguished from the policies actually implemented by his administration.[42] |

ラテンアメリカ ワシントン・コンセンサスはラテンアメリカにおいて「失われた10年」をもたらした。この期間、地域の多くの国民が国家債務危機に直面したのである。 [27] ワシントン・コンセンサスはラテンアメリカにおいて社会経済的排除と労働組合の弱体化を招き、地域の不安定化につながったと指摘されている。[28] [29] 当初この合意に従った国々は、高インフレと過剰な規制を緩和したものの、経済成長と貧困緩和はほとんど見られなかった。[30] この合意はラテンアメリカの中産階級の縮小を招き、1990年代後半には新自由主義への不満、政治的左派への転換、ポピュリスト指導者の台頭を促した。経 済学者らは、この合意がベネズエラのウーゴ・チャベス、ボリビアのエボ・モラレス、エクアドルのラファエル・コレアへの支持基盤を築いたと指摘している。 [4][29] [30] アルゼンチン 関連項目: アルゼンチン債務再編  アルゼンチン大統領カルロス・メネム 1999年から2002年にかけてのアルゼンチン経済危機は、ワシントン・コンセンサスの適用によって引き起こされたとされる経済的結果の一例として挙げられている。 1998年10月、IMFはアルゼンチン大統領カルロス・メネムを理事会年次総会に招き、アルゼンチンの成功体験について講演させた[31]。メネム政権 の経済政策(特に「通貨交換性」政策)の立案者であるドミンゴ・カバジョ経済相(1991-1996年)は次のように述べた: 1998年後半、ワシントンではアルゼンチンがブレイディ計画枠組み内で債務再編を行った国々の中で最も成功した経済と見なされていた。ワシントン・コン センサスの提唱者たちは、アルゼンチンの経済改革がその10項目の提言と異なる点を有することを指摘しようとはしなかった。むしろアルゼンチンはIMF、 世界銀行、米国政府にとって最も優秀な生徒と見なされていたのだ。[32] 固定為替レート制度への依存から生じる問題(上記)は、世界銀行報告書『1990年代の経済成長:改革の10年から学ぶ』で論じられている。同報告書は 「政府の裁量権を制限することで期待が好影響を受けるか」を疑問視している。1990年代初頭には、市場参加者に為替問題における政府の裁量権が完全に排 除されたことを確信させるため、各国は固定相場制か完全な変動相場制のいずれかに移行すべきだという見解があった。アルゼンチン崩壊後、一部の観察者は、 大きなペナルティを課す仕組みを作ることで政府の裁量権を排除することは、逆に期待そのものを損なう可能性があると考えるようになった。ベラスコとニュー ト(2003)[33]は「世界が不確実であり、裁量権の欠如が大きな損失をもたらす状況がある場合、事前約束装置は実際に事態を悪化させる」と主張して いる。[34] 世界銀行は報告書(『金融自由化:成功と失敗』)の第7章で、アルゼンチンで何が失敗したかを分析し、その経験から得られた教訓をまとめ、将来の政策に向 けた提言を行っている。[34] IMFの独立評価室は、アルゼンチンから機関が得た教訓に関するレビューを発表し、以下の引用文に要約されている: アルゼンチン危機はIMFに数多くの教訓をもたらした。その一部は既に学ばれ、改訂された政策と手続きに組み込まれている。本評価は、監視とプログラム設計、危機管理、意思決定プロセスの分野において10の教訓を示唆している。[35] ネストール・キルチネル大統領が価格統制や類似の行政措置(主に公益事業などの外資系企業を対象としたもの)に依存した姿勢は、コンセンサスの精神に明ら かに反していた。しかし同政権は実際には極めて厳格な財政運営を行い、競争力のある変動相場制を維持した。債務免除と一次産品価格の好況という追い風も相 まって、アルゼンチンが危機から即座に回復したことは、長期的な持続可能性に関する課題を未解決のまま残している。[36] エコノミスト誌は、ネストール・キルチネル政権はアルゼンチンの長いポピュリスト政権の歴史にまた一つ加わるに過ぎないと論じている。[37] 2008年10月、キルチネルの妻で後継大統領となったクリスティーナ・キルチネルは、メネム=カバジョ政権が導入した民営化制度の年金基金を国有化する 意向を表明した。[38] キルチネル政権下では、経済実績を不当に良好に見せるため(特にインフレ率において)公式統計が操作されたとの指摘が浮上している。[39] エコノミスト誌はアルゼンチンのインフレ指標を公式指標から除外し、信頼性が失われたと表明した。[40] 2003年、アルゼンチンのネストール・キルチネル大統領とブラジルのルイス・イナシオ・ルーラ・ダ・シルヴァ大統領は「ブエノスアイレス・コンセンサ ス」に署名した。これはワシントン・コンセンサスの政策に反対する宣言である。[41] しかし懐疑的な政治評論家は、ルーラ大統領がこうした公の場で示すレトリックと、実際に彼の政権が実施した政策とは区別すべきだと指摘している。[42] |

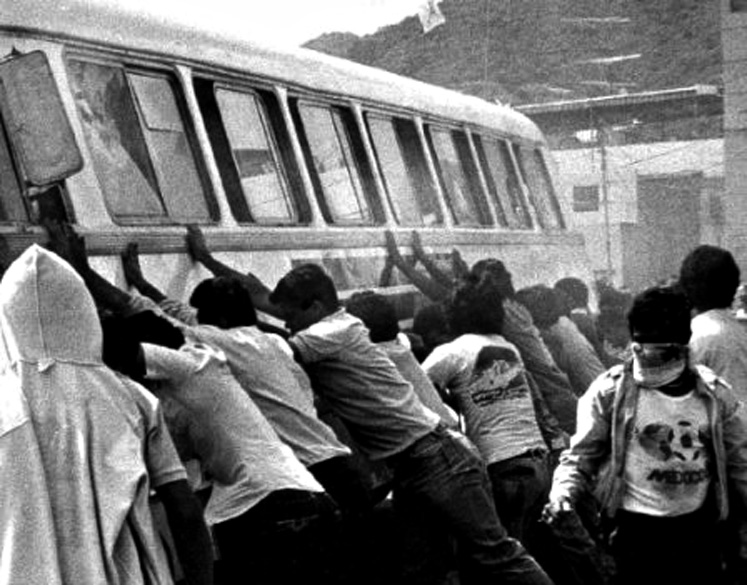

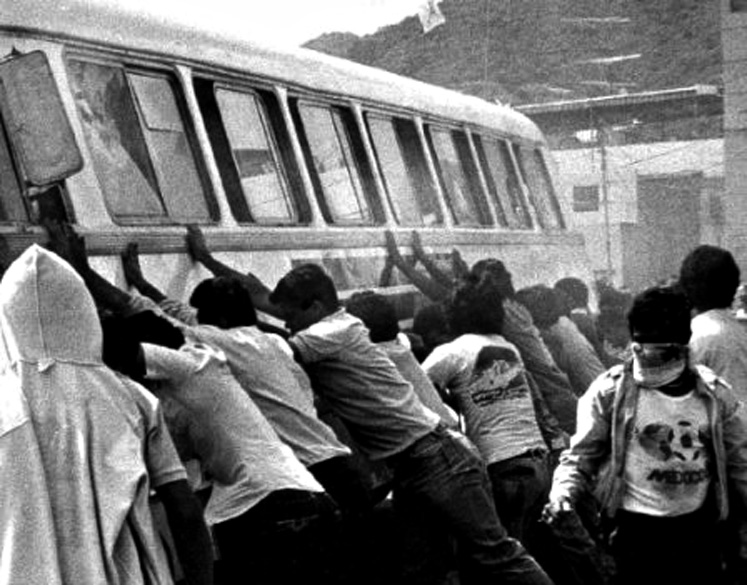

| Venezuela Main article: Second presidency of Carlos Andrés Pérez  A group of rioters attempting to push over a bus during the Caracazo  Venezuelan troops responding during the Caracazo  CANTV's old logo, state telecommunications company privatized in 1991 In the 1980s, a fall in oil prices and the start of the Latin American debt crisis brought economic difficulties to Venezuela. Additionally, President Luis Herrera Campins' economic policies led to the devaluation of the Venezuelan bolívar against the US dollar in a day that would be known as Viernes Negro (English: Black Friday).[43] Following the oil price crisis, the Herrera Campins government declared bankruptcy to the international banking community and then enacted currency restrictions.[43] The policies centred on the establishment of an exchange-rate regime, imposing a restriction on the movement of currencies, and were strongly objected to by the then-president of the Central Bank of Venezuela, Leopoldo Díaz Bruzual.[44] The currency controls devalued Venezuelan purchasing power by 75% in a matter of hours;[45] banks did not open on Viernes Negro, and even the Central Bank did not have many reserves of foreign currencies, causing the government to devalue the bolívar by 100%.[43] Carlos Andrés Pérez based his campaign for the 1988 Venezuelan general election in his legacy of abundance during his first presidential period[46] and initially rejected liberalization policies.[47] Venezuela's international reserves were only US$300 million at the time of Pérez' election into the presidency; Pérez decided to respond to the debt, public spending, economic restrictions and rentier state by liberalizing the economy[46] and proceeded to implement Washington consensus reforms.[48][47] He announced a technocratic cabinet and a group of economic policies to fix macroeconomic imbalances known as El Gran Viraje (es) (English: The Great Turn), called by detractors as El Paquetazo Económico (English: The Economic Package). Among the policies there was the reduction of fuel subsidies and the increase of public transportation fares by thirty percent (VEB 16 Venezuelan bolívares, or US$0.4).[49][50][51] The increase was supposed to be implemented on 1 March 1989, but bus drivers decided to apply the price rise on 27 February, a day before payday in Venezuela. In response, protests and rioting began on the morning of 27 February 1989 in Guarenas, a town near Caracas;[52] a lack of timely intervention by authorities, as the Caracas Metropolitan Police (es) was on a labor strike, led to the protests and rioting quickly spreading to the capital and other towns across the country.[53][47][48] By late 1991, as part of the economic reforms, Carlos Andrés Pérez' administration had sold three banks, a shipyard, two sugar mills, an airline, a telephone company and a cell phone band, receiving a total of US$2,287 million.[54] The most remarkable auction was CANTV's, a telecommunications company, which was sold at the price of US$1,885 million to the consortium composed of American AT&T International, General Telephone Electronic and the Venezuelan Electricidad de Caracas and Banco Mercantil. The privatization ended Venezuela's monopoly over telecommunications and surpassed even the most optimistic predictions, with over US$1,000 million above the base price and US$500 million more than the bid offered by the competition group.[55] By the end of the year, inflation had dropped to 31%, Venezuela's international reserves were now worth US$14,000 million and there was an economic growth of 9% (called as an "Asian growth"), the largest in Latin America at the time.[54] The Caracazo and previous inequality in Venezuela were used to justify the subsequent 1992 Venezuelan coup d'état attempts and led to the rise of Hugo Chávez's Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement-200,[56] who in 1982 had promised to depose the bipartisanship governments.[57] Once elected in 1998, Chávez began to revert the policies of his predecessors.[58] |

ベネズエラ 主な記事: カルロス・アンドレス・ペレスの第二期大統領任期  カラカソ暴動でバスを押し倒そうとする暴徒の一団  カラカソ暴動に対応するベネズエラ軍  1991年に民営化された国営通信会社CANTVの旧ロゴ 1980年代、石油価格の下落とラテンアメリカ債務危機の始まりがベネズエラに経済的困難をもたらした。さらに、ルイス・エレラ・カンピンス大統領の経済 政策は、ベネズエラ・ボリバルの対米ドル相場を一日で切り下げる結果となり、この日「ビエルネス・ニグロ(英語:ブラックフライデー)」として知られるよ うになった。[43] 石油価格危機を受け、エレラ・カンピンス政権は国際銀行界に対し債務不履行を宣言し、通貨規制を実施した[43]。政策の中心は為替レート制度の確立と通 貨移動の制限であり、当時のベネズエラ中央銀行総裁レオポルド・ディアス・ブルサルは強く反対した。[44] 通貨規制によりベネズエラの購買力は数時間で75%下落した[45]。ブラックフライデーには銀行は営業せず、中央銀行でさえ外貨準備が乏しかったため、 政府はボリバルを100%切り下げた。[43] カルロス・アンドレス・ペレスは1988年ベネズエラ総選挙の選挙運動において、自身の大統領第一期における豊かさの遺産を基盤とし[46]、当初は自由 化政策を拒否した。[47] ペレスが大統領に当選した時点で、ベネズエラの国際準備高はわずか3億米ドルだった。ペレスは債務、公共支出、経済規制、レントシーカー国家への対応策と して経済自由化を決定し[46]、ワシントン・コンセンサス改革の実施に着手した。[48][47] 彼は技術官僚内閣を発表し、マクロ経済の不均衡を是正するための経済政策群「エル・グラン・ビラヘ(スペイン語:大転換)」を打ち出した。批判派からは 「エル・パケタソ・エコノミコ(スペイン語:経済パッケージ)」と呼ばれた。政策の中には燃料補助金の削減と公共交通運賃の30%値上げ(ベネズエラ・ボ リバル16ベネズエラ・ボリバル、約0.4米ドル)が含まれていた[49][50][51]。値上げは1989年3月1日に実施される予定だったが、バス 運転手たちはベネズエラの給料日である2月28日の前日に値上げを実施することを決めた。これに対し、1989年2月27日朝、カラカス近郊の町グアレナ スで抗議活動と暴動が発生した[52]。カラカス首都警察(es)が労働争議中であったため、当局の迅速な介入が欠如し、抗議活動と暴動は瞬く間に首都及 び国内の他の町へ拡大した[53][47]。[48] 1991年末までに、経済改革の一環としてカルロス・アンドレス・ペレス政権は3つの銀行、造船所、2つの製糖工場、航空会社、電話会社、携帯電話周波数 帯を売却し、総額22億8700万ドルを得た。[54] 最も注目された売却は通信会社CANTVで、米AT&Tインターナショナル、ジェネラル・テレフォン・エレクトロニック、ベネズエラのエレクトリ シダッド・デ・カラカス、バンコ・メルカンティルのコンソーシアムに18億8500万ドルで売却された。この民営化によりベネズエラの通信独占は終焉を迎 え、最低入札価格を10億米ドル以上、競合グループの入札額を5億米ドルも上回る結果となり、最も楽観的な予測さえも上回った。[55] 年末までにインフレ率は31%まで低下し、ベネズエラの国際準備高は140億米ドルに達した。経済成長率は9%(「アジア的成長」と呼ばれた)を記録し、 当時ラテンアメリカ最大であった。[54] カラカソ事件とベネズエラにおける従来の不平等は、1992年のクーデター未遂の正当化に利用され、ウーゴ・チャベスの「ボリバル革命運動200」 [56]の台頭を招いた。チャベスは1982年に二大政党制政府の打倒を公約していた[57]。1998年に当選すると、チャベスは前任者たちの政策を覆 し始めた。[58] |

| Criticism See also: Post-neoliberalism As of the 2000s, several Latin American countries were led by socialist or other left wing governments, some of which—including Argentina and Venezuela—have campaigned for (and to some degree adopted) policies contrary to the Washington Consensus policies. Other Latin American countries with governments of the left, including Brazil, Chile and Peru, in practice adopted the bulk of the policies included in Williamson's list, even though they criticized the market fundamentalism that these are often associated with. General criticism of the economics of the consensus is now more widely established, such as that outlined by US scholar Dani Rodrik, Professor of International Political Economy at Harvard University, in his paper Goodbye Washington Consensus, Hello Washington Confusion?.[59] As Williamson has pointed out, the term has come to be used in a broader sense than its original intention, as a synonym for market fundamentalism or neoliberalism. In this broader sense, Williamson states, it has been criticized by people such as George Soros and Joseph Stiglitz.[13] The Washington Consensus is also criticized by others such as some Latin American politicians and heterodox economists such as Erik Reinert.[60] The term has become associated with neoliberal policies in general and drawn into the broader debate over the expanding role of the free market, constraints upon the state, and the influence of the United States, and globalization more broadly, on countries' national sovereignty.[citation needed] Some US economists, such as Joseph Stiglitz and Dani Rodrik, have challenged what are sometimes described as the 'fundamentalist' policies of the IMF and the US Treasury for what Stiglitz calls a 'one size fits all' treatment of individual economies. According to Stiglitz the treatment suggested by the IMF is too simple: one dose, and fast—stabilize, liberalize and privatize, without prioritizing or watching for side effects.[61] The reforms did not always work out the way they were intended. While growth generally improved across much of Latin America, it was in most countries less than the reformers had originally hoped for (and the "transition crisis", as noted above deeper and more sustained than hoped for in some of the former socialist economies). Success stories in Sub-Saharan Africa during the 1990s were relatively few and far in between, and market-oriented reforms by themselves offered no formula to deal with the growing public health emergency in which the continent became embroiled. The critics, meanwhile, argue that the disappointing outcomes have vindicated their concerns about the inappropriateness of the standard reform agenda.[62] Besides the excessive belief in market fundamentalism and international economic institutions in attributing the failure of the Washington consensus, Stiglitz provided a further explanation about why it failed. In his article "The Post Washington Consensus Consensus",[63] he claims that the Washington consensus policies failed to efficiently handle the economic structures within developing countries. The cases of East Asian states such as Korea and Taiwan are known as a success story in which their remarkable economic growth was attributed to a larger role of the government by undertaking industrial policies and increasing domestic savings within their territory. From the cases, the role for government was proven to be critical at the beginning stage of the dynamic process of development, at least until the markets by themselves can produce efficient outcomes.[citation needed] The policies pursued by the international financial institutions which came to be called the Washington consensus policies or neoliberalism entailed a much more circumscribed role for the state than were embraced by most of the East Asian countries, a set of policies which (in another simplification) came to be called the development state.[63] The critique laid out in the World Bank's study Economic Growth in the 1990s: Learning from a Decade of Reform (2005)[64] shows how far discussion has come from the original ideas of the Washington Consensus. Gobind Nankani, a former vice-president for Africa at the World Bank, wrote in the preface: "there is no unique universal set of rules.... [W]e need to get away from formulae and the search for elusive 'best practices'...." (p. xiii). The World Bank's new emphasis is on the need for humility, for policy diversity, for selective and modest reforms, and for experimentation.[65] The World Bank's report Learning from Reform shows some of the developments of the 1990s. There was a deep and prolonged collapse in output in some (though by no means all) countries making the transition from communism to market economies (many of the Central and East European countries, by contrast, made the adjustment relatively rapidly). Academic studies show that more than two decades into the transition, some of the former communist countries, especially parts of the former Soviet Union, had still not caught up to their levels of output before 1989.[66][67] A 2001 study by economist Steven Rosefielde posits that there were 3.4 million premature deaths in Russia from 1990 to 1998, which he party blames on the shock therapy imposed by the Washington Consensus.[68] Neoliberal policies associated with the Washington Consensus, including pension privatization, the imposition of a flat tax, monetarism, cutting of corporate taxes, and central bank independence, continued into the 2000s.[69] Many Sub-Saharan African's economies failed to take off during the 1990s, in spite of efforts at policy reform, changes in the political and external environments, and continued heavy influx of foreign aid. Uganda, Tanzania, and Mozambique were among countries that showed some success, but they remained fragile. There were several successive and painful financial crises in Latin America, East Asia, Russia, and Turkey. The Latin American recovery in the first half of the 1990s was interrupted by crises later in the decade. There was less growth in per capita GDP in Latin America than in the period of rapid post-War expansion and opening in the world economy, 1950–80. Argentina, described by some as "the poster boy of the Latin American economic revolution",[70] came crashing down in 2002.[65] A significant body of economists and policy-makers argues that what was wrong with the Washington Consensus as originally formulated by Williamson had less to do with what was included than with what was missing.[71] This view asserts that countries such as Brazil, Chile, Peru and Uruguay, largely governed by parties of the left in recent years, did not—whatever their rhetoric—in practice abandon most of the substantive elements of the Consensus. Countries that have achieved macroeconomic stability through fiscal and monetary discipline have been loath to abandon it: Lula, the former President of Brazil (and former leader of the Workers' Party of Brazil), has stated explicitly that the defeat of hyperinflation[72] was among the most important positive contributions of the years of his presidency to the welfare of the country's poor, although the remaining influence of his policies on tackling poverty and maintaining a steady low rate of inflation are being discussed and doubted in the wake of the Brazilian Economic Crisis currently occurring in Brazil.[73] These economists and policy-makers would, however, overwhelmingly agree that the Washington Consensus was incomplete, and that countries in Latin America and elsewhere need to move beyond "first generation" macroeconomic and trade reforms to a stronger focus on productivity-boosting reforms and direct programs to support the poor.[74] This includes improving the investment climate and eliminating red tape (especially for smaller firms), strengthening institutions (in areas like justice systems), fighting poverty directly via the types of Conditional Cash Transfer programs adopted by countries like Mexico and Brazil, improving the quality of primary and secondary education, boosting countries' effectiveness at developing and absorbing technology, and addressing the needs of historically disadvantaged groups including indigenous peoples and Afro-descendant populations across Latin America.[citation needed] In a book edited with future president of Peru, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski in 2003, John Williamson laid out an expanded reform agenda, emphasizing crisis-proofing of economies, "second-generation" reforms, and policies addressing inequality and social issues.[14] Nobel laureate Michael Spence has defended the Washington Consensus, arguing "I continue to find that when properly interpreted as a guide to the formulation of country-specific development strategies, the Washington Consensus has withstood the test of time quite well."[8] According to Spence, "The Washington Consensus was never intended as a complete or a one-size-fits-all development program."[8] He does however note that the Washington Consensus "was vulnerable to misuse due to the absence of an accompanying and explicit development model."[8] |

批判 参照:ポスト新自由主義 2000年代、ラテンアメリカのいくつかの国々は社会主義またはその他の左翼政権によって統治されており、そのうちのいくつかは、アルゼンチンやベネズエ ラを含め、ワシントン・コンセンサス政策とは相反する政策を提唱し(そしてある程度は採用している)。ブラジル、チリ、ペルーなど、左派政権を持つ他のラ テンアメリカ諸国も、実際には、ウィリアムソンのリストに含まれる政策の大部分を採用している。 コンセンサスの経済学に対する一般的な批判は、現在ではより広く定着している。例えば、ハーバード大学の国際政治経済学教授である米国の学者、ダニ・ロドリックが、彼の論文「さようなら、ワシントン・コンセンサス、こんにちは、ワシントン・コンフュージョン?[59] ウィリアムソンが指摘しているように、この用語は、市場原理主義や新自由主義の同義語として、本来の意図よりも広い意味で使われるようになった。ウィリア ムソンは、この広い意味で、ジョージ・ソロスやジョセフ・スティグリッツなどの人々から批判されていると述べている。[13] ワシントン・コンセンサスは、ラテンアメリカの政治家や、エリック・ライナートなどの非正統派経済学者など、他の者たちからも批判されている。[60] この用語は、新自由主義政策全般に関連付けられ、自由市場の役割の拡大、国家に対する制約、米国の影響力、そしてより広くはグローバル化が各国の国民主権 に与える影響に関する幅広い議論に巻き込まれている。[要出典] ジョセフ・スティグリッツやダニ・ロドリックといった米国人経済学者らは、IMFや米国財務省の政策を「原理主義的」と評し、スティグリッツが「画一的な 処方箋」と呼ぶ個別経済への対応を問題視している。スティグリッツによれば、IMFが提案する処方箋は単純すぎる。つまり「安定化・自由化・民営化」とい う単一の処方箋を迅速に適用するだけで、優先順位付けや副作用の監視を怠っているというのだ。[61] これらの改革は必ずしも意図した通りに機能しなかった。ラテンアメリカ全域で成長は概ね改善したものの、ほとんどの国では改革派が当初期待した水準には達 せず(前述の「移行危機」は、旧社会主義経済圏の一部では予想以上に深刻かつ長期化した)。1990年代のサハラ以南アフリカにおける成功事例は比較的少 なく、市場志向の改革だけでは、大陸が巻き込まれた公衆衛生上の緊急事態に対処する定式とはならなかった。一方、批判派は、期待外れの結果が標準的な改革 アジェンダの不適切性に関する彼らの懸念を正当化したと主張している。[62] ワシントン・コンセンサスの失敗要因として、市場原理主義や国際経済機関への過信に加え、スティグリッツは別の説明を加えた。論文「ポスト・ワシントン・ コンセンサス・コンセンサス」[63]で、彼はワシントン・コンセンサス政策が途上国の経済構造を効率的に処理できなかったと主張している。韓国や台湾と いった東アジア諸国の事例は成功事例として知られており、その目覚ましい経済成長は、産業政策の実施や国内貯蓄の増加といった政府のより大きな役割に起因 するとされている。これらの事例から、少なくとも市場が自力で効率的な成果を生み出せるようになるまでの間、ダイナミックな発展プロセスの初期段階におい て政府の役割が決定的に重要であることが証明された。[出典が必要] ワシントン・コンセンサス政策あるいは新自由主義と呼ばれるようになった国際金融機関の政策は、東アジア諸国の多くが採用した「開発国家」政策(別の単純化表現)よりも、国家の役割をはるかに限定するものであった。[63] 世界銀行の研究『1990年代の経済成長:改革の10年から学ぶこと』(2005年)[64]に示された批判は、議論がワシントン・コンセンサスの当初の 考えからどれほど離れたかを示している。世界銀行元アフリカ担当副総裁ゴビンド・ナンカニは序文でこう記した:「唯一の普遍的なルールなど存在しない。我 々は定式や捉えどころのない『ベストプラクティス』の探求から脱却する必要がある...」(p. xiii)。世界銀行が新たに重視するのは、謙虚さ、政策の多様性、選択的かつ控えめな改革、そして実験の必要性である[65]。 世界銀行の報告書『改革から学ぶ』は、1990年代の進展の一部を示している。共産主義から市場経済への移行期にある一部の国々(決して全てではないが) では、生産高が深刻かつ長期にわたって落ち込んだ(対照的に、中東欧諸国の多くは比較的迅速に適応した)。学術研究によれば、移行開始から20年以上経っ た後も、旧共産圏諸国、特に旧ソ連地域の一部では、1989年以前の生産水準にまだ回復していなかった[66]。[67] 経済学者スティーブン・ローズフィールドによる2001年の研究では、1990年から1998年にかけてロシアで340万人の早死が発生したと推定され、 その一因としてワシントン・コンセンサスに基づくショック療法が指摘されている。[68] 年金民営化、均一税率の導入、金融政策重視、法人税減税、中央銀行の独立性確保といったワシントン・コンセンサスに連なる新自由主義政策は、2000年代 に入っても継続された。[69] 政策改革の試み、政治的・外部環境の変化、継続的な多額の外国援助にもかかわらず、1990年代にサハラ以南アフリカの多くの経済は離陸に失敗した。ウガ ンダ、タンザニア、モザンビークは一定の成功を示した国々だったが、依然として脆弱な状態だった。ラテンアメリカ、東アジア、ロシア、トルコでは相次ぐ痛 ましい金融危機が発生した。1990年代前半のラテンアメリカの回復は、同年代後半の危機によって中断された。ラテンアメリカの 1 人当たり GDP の伸びは、1950 年から 1980 年にかけての、戦後の急速な拡大と世界経済の開放の時期よりも低かった。一部から「ラテンアメリカの経済革命の象徴」と評されていたアルゼンチンは、 2002 年に崩壊した。[65] 多くの経済学者や政策立案者は、ウィリアムソンが当初策定したワシントン・コンセンサスの問題点は、その内容よりも、欠けている部分にあると主張している [71]。この見解は、近年、左派政党が政権を握っているブラジル、チリ、ペルー、ウルグアイなどの国々は、そのレトリックはともかく、実際にはコンセン サスの実質的な要素のほとんどを放棄していないと主張している。財政および金融の規律によってマクロ経済の安定を達成した国々は、それを放棄することを 嫌っている。ブラジルのルラ前大統領(およびブラジル労働者党の元党首)は、ハイパーインフレの克服[72] が、大統領在任中の貧困層福祉に対する最も重要な貢献の一つであったと明言している。しかし、貧困対策と安定した低インフレ率の維持に関する彼の政策の残 された影響は、現在ブラジルで発生しているブラジル経済危機を受けて議論され、疑問視されている。[73] しかし、これらの経済学者や政策立案者は、ワシントン・コンセンサスが不完全であったこと、そしてラテンアメリカやその他の地域の国々が「第一世代」のマ クロ経済・貿易改革を超えて、生産性向上改革と貧困層支援の直接プログラムに重点を移す必要がある点については、圧倒的に同意するだろう。[74] これには、投資環境の改善と(特に中小企業向けの)官僚的な手続きの排除、司法制度などの分野における制度の強化、メキシコやブラジルなどの国々が採用し ている条件付き現金給付プログラムによる貧困の直接的な撲滅、初等中等教育の質の向上、技術開発と吸収における各国の効率性の向上、そしてラテンアメリカ 全域の先住民やアフリカ系住民など、歴史的に不利な立場にある集団のニーズへの対応などが含まれる。 2003年にペルーの次期大統領ペドロ・パブロ・クチンスキーと共同編集した著書の中で、ジョン・ウィリアムソンは、経済の危機に対する耐性、「第二世代」の改革、不平等や社会問題に対処する政策を強調し、拡大された改革アジェンダを提示した。[14] ノーベル賞受賞者のマイケル・スペンスは、ワシントン・コンセンサスを擁護し、「ワシントン・コンセンサスは、各国固有の開発戦略の策定の指針として適切 に解釈された場合、時の試練に十分耐えてきたと私は引き続き考えている」と主張している。[8] スペンスによれば、「ワシントン・コンセンサスは、完全な、あるいは万能の開発プログラムとして意図されたものではない」[8]。しかし、ワシントン・コ ンセンサスは「付随する明確な開発モデルがないため、誤用されやすい」[8]とも指摘している。 |

| Anti-globalization movement Many critics of trade liberalization, such as Noam Chomsky, Tariq Ali, Susan George, and Naomi Klein, see the Washington Consensus as a way to open the labor market of underdeveloped economies to exploitation by companies from more developed economies. The prescribed reductions in tariffs and other trade barriers allow the free movement of goods across borders according to market forces, but labor is not permitted to move freely due to the requirements of a visa or a work permit. This creates an economic climate where goods are manufactured using cheap labor in underdeveloped economies and then exported to rich First World economies for sale at what the critics argue are huge markups, with the balance of the markup said to accrue to large multinational corporations. The criticism is that workers in the Third World economy nevertheless remain poor, as any pay raises they may have received over what they made before trade liberalization are said to be offset by inflation, whereas workers in the First World country become unemployed, while the wealthy owners of the multinational grow even more wealthy.[75] Despite macroeconomic advances, poverty and inequality remain at high levels in Latin America. About one of every three people—165 million in total—still live on less than $2 a day. Roughly a third of the population has no access to electricity or basic sanitation, and an estimated 10 million children suffer from malnutrition. These problems are not, however, new: Latin America was the most economically unequal region in the world in 1950, and has continued to be so ever since, during periods both of state-directed import-substitution and (subsequently) of market-oriented liberalization.[76] Some socialist political leaders in Latin America have been vocal and well-known critics of the Washington Consensus, such as the late Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, Cuban ex-President Fidel Castro, Bolivian President Evo Morales, and Rafael Correa, President of Ecuador. In Argentina, too, the recent Justicialist Party government of Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner undertook policy measures which represented a repudiation of at least some Consensus policies.[77] |

反グローバリゼーション運動 ノーム・チョムスキー、タリク・アリ、スーザン・ジョージ、ナオミ・クラインといった貿易自由化批判派の多くは、ワシントン・コンセンサスを発達途上国の 労働市場を先進国企業の搾取に開放する手段と見なしている。関税やその他の貿易障壁の削減が義務付けられることで、市場原理に従い国境を越えた商品の自由 な移動は可能となる。しかし労働者は、ビザや就労許可の要件により自由に移動することが許されない。これにより、発展途上経済圏で安価な労働力を用いて製 造された商品が、富裕な先進国経済圏へ輸出され、批判者らが主張する巨額の値上げを経て販売される経済環境が生まれる。この値上げ分の差益は、大企業であ る多国籍企業に蓄積されると言われている。批判の焦点は、第三世界経済の労働者が依然として貧困状態にある点だ。貿易自由化前に比べて賃金が上昇したとし ても、その増加分はインフレによって相殺されるとされる。一方で第一世界国の労働者は失業に追い込まれ、多国籍企業の富裕な所有者はさらに富を増大させて いる。[75] マクロ経済の進展にもかかわらず、ラテンアメリカでは貧困と不平等が依然として高い水準にある。約3人に1人、総計1億6500万人が、1日2ドル未満で 生活している。人口の約3分の1が電気や基本的な衛生設備を利用できず、推定1000万人の子どもが栄養不良に苦悩している。しかしこれらの問題は新たな ものではない。ラテンアメリカは1950年時点で世界でもっとも経済的不平等が深刻な地域であり、国家主導の輸入代替政策期も、その後の市場志向の自由化 期も、その状態は変わっていない。[76] ラテンアメリカの社会主義系政治指導者の中には、ワシントン・コンセンサスを声高に批判する著名な人物が存在する。故ベネズエラ大統領ウーゴ・チャベス、 キューバ元大統領フィデル・カストロ、ボリビア大統領エボ・モラレス、エクアドル大統領ラファエル・コレアらがその例だ。アルゼンチンでも、ネストール・ キルチネルとクリスティーナ・フェルナンデス・デ・キルチネルによる最近の正義党政権は、少なくとも一部のコンセンサス政策を否定する政策措置を実施した [77]。 |

| Proponents of the "European model" and the "Asian way" Some European and Asian economists suggest that "infrastructure-savvy economies" such as Norway, Singapore, and China have partially rejected the underlying Neoclassical "financial orthodoxy" that characterizes the Washington Consensus, instead initiating a pragmatist development path of their own[78] based on sustained, large-scale, government-funded investments in strategic infrastructure projects: "Successful countries such as Singapore, Indonesia, and South Korea still remember the harsh adjustment mechanisms imposed abruptly upon them by the IMF and World Bank during the 1997–1998 'Asian Crisis' […] What they have achieved in the past 10 years is all the more remarkable: they have quietly abandoned the Washington Consensus by investing massively in infrastructure projects […] this pragmatic approach proved to be very successful".[79] While opinion varies among economists, Rodrik pointed out what he claimed was a factual paradox: while China and India increased their economies' reliance on free market forces to a limited extent, their general economic policies remained the exact opposite to the Washington Consensus' main recommendations. Both had high levels of protectionism, no privatization, extensive industrial policies planning, and lax fiscal and financial policies through the 1990s. Had they been dismal failures they would have presented strong evidence in support of the recommended Washington Consensus policies. However they turned out to be successes.[80] According to Rodrik: "While the lessons drawn by proponents and skeptics differ, it is fair to say that nobody really believes in the Washington Consensus anymore. The question now is not whether the Washington Consensus is dead or alive; it is what will replace it".[59] Rodrik's account of Chinese or Indian policies during the period is not universally accepted. Among other things those policies involved major turns in the direction of greater reliance upon market forces, both domestically and internationally.[81] |

「欧州モデル」と「アジア方式」の支持者たち 一部の欧州およびアジアの経済学者たちは、ノルウェー、シンガポール、中国といった「インフラに精通した経済」が、ワシントン・コンセンサスを特徴づける 新古典派の「金融正統主義」を部分的に拒否し、代わりに戦略的インフラプロジェクトへの持続的かつ大規模な政府資金による投資に基づく独自の現実主義的発 展経路を模索していると指摘する[78]: 「シンガポール、インドネシア、韓国といった成功国は、1997~1998年の『アジア危機』時にIMFと世界銀行が突然押し付けた厳しい調整メカニズム を今も覚えている[…]。彼らが過去10年間で成し遂げたことはさらに注目に値する。インフラ事業への大規模投資によってワシントン・コンセンサスを静か に放棄したのだ[…]。この現実主義的アプローチは非常に成功したことが証明された」。[79] 経済学者の間では意見が分かれるが、ロドリックは事実上のパラドックスを指摘した。中国とインドは自由市場への依存度を限定的に高めた一方で、経済政策全 体はワシントン・コンセンサスの主要提言とは正反対だった。両国とも1990年代を通じて、高い保護主義、民営化なし、広範な産業政策計画、緩い財政・金 融政策を維持した。もしこれらが惨憺たる失敗に終わっていたなら、推奨されたワシントン・コンセンサス政策を支持する強力な証拠となったはずだ。しかし実 際には成功を収めたのである。[80] ロドリックによれば:「支持者と懐疑派が導き出す教訓は異なるが、もはや誰もワシントン・コンセンサスを真に信じていないと言うのが妥当だろう。現在の問 題はワシントン・コンセンサスが存続するか否かではなく、それに代わるものは何かということだ」 [59] ロドリックによるこの期間の中国やインドの政策に関する記述は、普遍的に受け入れられているわけではない。とりわけ、それらの政策には、国内外を問わず市場原理への依存度を高める方向への大きな転換が含まれていた。[81] |

| Subsidies for agriculture The Washington Consensus as formulated by Williamson includes provision for the redirection of public spending from subsidies ("especially indiscriminate subsidies") toward broad-based provision of key pro-growth, pro-poor services like primary education, primary health care and infrastructure investment. This definition leaves some room for debate over specific public spending programs. One area of public controversy has focused on the issues of subsidies to farmers for fertilizers and other modern farm inputs: on the one hand, these can be criticized as subsidies, on the other, some experts argued that smallholder farmers often lack access to technical information, and these funding can generate positive externalities that might justify the subsidy involved.[82] Some critics of the Washington Consensus cite Malawi's experience with agricultural subsidies, for example, as exemplifying perceived flaws in the package's prescriptions. For decades, the World Bank and donor nations pressed Malawi, a predominantly rural country in Africa, to cut back or eliminate government fertilizer subsidies to farmers. World Bank experts also urged the country to have Malawi farmers shift to growing cash crops for export and to use foreign exchange earnings to import food.[83] For years, Malawi hovered on the brink of famine; after a particularly disastrous corn harvest in 2005, almost five million of its 13 million people needed emergency food aid. Malawi's president Bingu wa Mutharika then decided to reverse policy. Introduction of deep fertilizer subsidies (and lesser ones for seed), abetted by good rains, helped farmers produce record-breaking corn harvests in 2006 and 2007; according to government reports, corn production leapt from 1.2 million metric tons in 2005 to 2.7 million in 2006 and 3.4 million in 2007. The prevalence of acute child hunger has fallen sharply and Malawi turned away emergency food aid in 2006.[84] In a commentary on the Malawi experience prepared for the Center for Global Development,[85] development economists Vijaya Ramachandran and Peter Timmer argue that fertilizer subsidies in parts of Africa (and Indonesia) can have benefits that substantially exceed their costs. They caution, however, that how the subsidy is operated is crucial to its long-term success, and warn against allowing fertilizer distribution to become a monopoly. Ramachandran and Timmer also stress that African farmers need more than just input subsidies—they need better research to develop new inputs and new seeds, as well as better transport and energy infrastructure. The World Bank reportedly now sometimes supports the temporary use of fertilizer subsidies aimed at the poor and carried out in a way that fosters private markets: "In Malawi, Bank officials say they generally support Malawi's policy, though they criticize the government for not having a strategy to eventually end the subsidies, question whether its 2007 corn production estimates are inflated and say there is still a lot of room for improvement in how the subsidy is carried out".[83] |

農業への補助金 ウィリアムソンが策定したワシントン・コンセンサスには、補助金(「特に無差別な補助金」)から、初等教育、初等医療、インフラ投資など、成長と貧困層支 援に資する重要なサービスを広く提供することへ、公共支出の方向転換を図るという規定が含まれている。この定義は、具体的な公共支出プログラムについて議 論の余地を残している。公的な論争の一つは、肥料やその他の近代的な農業投入材に対する農家への補助金問題に集中している。一方では、これらは補助金とし て批判される可能性があるが、他方では、小規模農家は技術情報へのアクセスが不足していることが多いと一部の専門家は主張し、こうした資金援助は、関連す る補助金を正当化するようなプラスの外部性を生み出す可能性があると主張している。[82] ワシントン・コンセンサス批判派は、例えばマラウイの農業補助金事例を、同政策パッケージの欠陥を示す典型例として挙げる。数十年にわたり、世界銀行と援 助国民は、主に農村部からなるアフリカの国マラウイに対し、農家への政府肥料補助金の削減または廃止を迫った。世界銀行の専門家らはさらに、マラウイの農 民が輸出向け換金作物の栽培に転換し、外貨収入で食料を輸入するよう促した[83]。長年にわたりマラウイは飢饉の瀬戸際にあり、特に壊滅的な被害を受け た2005年のトウモロコシ収穫後には、1300万人の人口のうち約500万人が緊急食糧援助を必要とした。これを受け、マラウイのビンゴ・ワ・ムタリカ 大統領は政策転換を決断した。大幅な肥料補助金(種子への補助金は小幅)の導入と好天に助けられ、農民は2006年と2007年に記録的なトウモロコシ収 穫を達成した。政府報告によれば、トウモロコシ生産量は2005年の120万トンから2006年には270万トン、2007年には340万トンへと急増し た。子どもの急性飢餓の発生率は急激に低下し、マラウイは2006年に緊急食糧援助を拒否した[84]。 グローバル開発センター向けに作成されたマラウイの事例に関する論評[85]で、開発経済学者のヴィジャヤ・ラマチャンドランとピーター・ティマーは、ア フリカの一部地域(およびインドネシア)における肥料補助金は、そのコストを大幅に上回る利益をもたらし得ると主張している。ただし、補助金の運用方法が 長期的な成功の鍵であり、肥料供給が独占状態になることを警戒すべきだと警告している。ラマチャンドランとティマーはさらに、アフリカの農民には投入物資 の補助金だけでなく、新たな投入物資や種子を開発するための優れた研究、そしてより良い輸送・エネルギーインフラが必要だと強調している。世界銀行は現 在、貧困層を対象とし民間市場を育成する形で実施される肥料補助金を一時的に支援する場合があると報じられている。「マラウイでは、銀行当局者は同国の政 策を概ね支持すると述べている。ただし政府が補助金を最終的に廃止する戦略を持たない点を批判し、2007年のトウモロコシ生産量推計が過大ではないかと 疑問を呈し、補助金の実施方法には依然として改善の余地が大きいと指摘している」。[83] |

| Alternative usage vis-à-vis foreign policy In early 2008, the term "Washington Consensus" was used in a different sense as a metric for analyzing American mainstream media coverage of U.S. foreign policy generally and Middle East policy specifically. Marda Dunsky writes, "Time and again, with exceedingly rare exceptions, the media repeat without question, and fail to challenge the "Washington consensus"—the official mind-set of US governments on Middle East peacemaking over time."[86] According to syndicated columnist William Pfaff, Beltway centrism in American mainstream media coverage of foreign affairs is the rule rather than the exception: "Coverage of international affairs in the US is almost entirely Washington-driven. That is, the questions asked about foreign affairs are Washington's questions, framed in terms of domestic politics and established policy positions. This invites uninformative answers and discourages unwanted or unpleasant views."[87] |

外交政策における代替的用法 2008年初頭、「ワシントン・コンセンサス」という用語は、米国の外交政策全般、特に中東政策に関するアメリカ主流メディアの報道を分析する尺度とし て、異なる意味で用いられた。マーダ・ダンスキーはこう記している。「極めて稀な例外を除き、メディアは繰り返し疑問も持たず『ワシントン・コンセンサ ス』——つまり米国政府が長年にわたり中東和平プロセスに対して抱いてきた公式的な考え方——を無批判に受け入れる」 [86] コラムニストのウィリアム・プファフによれば、アメリカ主流メディアの外交報道におけるベルトウェイ・セントリズム(ワシントン中心主義)は例外ではなく 常態である。「米国の国際情勢報道はほぼ完全にワシントン主導だ。つまり、外交問題に関する問いかけはワシントンの問いかけであり、国内政治と既定の政策 立場に基づいて構成されている。これは情報価値の低い回答を招き、望ましくない見解や不快な見解を排除する」[87] |

| American imperialism Beijing Consensus Bretton Woods system Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) Democratic capitalism The End of History and the Last Man Andre Gunder Frank Gross domestic product Hyperinflation Immanuel Wallerstein Lima Consensus Mumbai Consensus North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper Structural adjustment World Systems Theory |

アメリカ帝国主義 北京コンセンサス ブレトン・ウッズ体制 中米自由貿易協定(CAFTA) 民主的資本主義 歴史の終わりと最後の人間 アンドレ・ギュンダー・フランク 国内総生産 ハイパーインフレーション イマニュエル・ウォーラスティン リマ・コンセンサス ムンバイ・コンセンサス 北米自由貿易協定(NAFTA) 貧困削減戦略文書 構造調整 世界システム論 |

| References |

|

| Sources Primary sources Accelerated Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Agenda for Action, Eliot Berg, coord., (World Bank, 1981). The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism, by Michael Novak (1982). El Otro Sendero (The Other Path), by Hernando de Soto (1986). Toward Renewed Economic Growth in Latin America, by Bela Balassa, Gerardo M. Bueno, Pedro-Pablo Kuczynski, and Mario Henrique (Institute for International Economics, 1986). Latin American Adjustment: How Much Has Happened, edited by John Williamson (Institute for International Economics, 1990). The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America, edited by Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards (1991). Global Linkages: Macroeconomic Interdependence and Cooperation in the World Economy, by Jeffrey Sachs and Warwick McKibbin (1991). World Development Report 1991: The Challenge of Development, by Lawrence Summers, Vinod Thomas, et al. (World Bank, 1991). "Development and the "Washington Consensus"", in World Development Vol 21:1329–1336 by John Williamson (1993). "Recent Lessons of Development", Lawrence H. Summers & Vinod Thomas (1993). Latin America's Journey to the Market: From Macroeconomic Shocks to Institutional Therapy, by Moises Naím (1994). Economistas y Politicos: La Política de la Reforma Económica, by Agustín Fallas-Santana (1996). The Crisis of Global Capitalism: Open Society Endangered, by George Soros (1997). Beyond Tradeoffs: Market Reform and Equitable Growth in Latin America, edited by Nancy Birdsall, Carol Graham, and Richard Sabot (Brookings Institution, 1998). The Third Way: Toward a Renewal of Social Democracy, by Anthony Giddens (1998). The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization, by Thomas Friedman (1999). "Fads and Fashion in Economic Reforms: Washington Consensus or Washington Confusion?", by Moisés Naím (IMF, 1999). Washington Contentious: Economic Policies for Social Equity in Latin America, by Nancy Birdsall and Augusto de la Torre (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and Inter-American Dialogue, 2001) "Did the Washington Consensus Fail?", by John Williamson (Speech at PIIE, 2002). Kuczynski, Pedro-Pablo; Williamson, John, eds. (2003). After the Washington Consensus: Restarting Growth and Reform in Latin America. Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics. ISBN 9780881324518. Williamson, John (2003). "An Agenda for Restarting Growth and Reform" (PDF). In Kuczynski, Pedro-Pablo; Williamson, John (eds.). After the Washington Consensus: Restarting Growth and Reform in Latin America. Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics. ISBN 9780881324518. Implementing Economic Reforms in Mexico: The Washington Consensus as a Roadmap for Developing Countries by Terrence Fluharty (2007) Implementing Economic Reforms in Mexico: The Washington Consensus as a Roadmap for Developing Countries |

出典 一次資料 『サハラ以南アフリカにおける加速的発展:行動計画』エリオット・バーグ編(世界銀行、1981年)。 『民主的資本主義の精神』マイケル・ノバック著(1982年)。 『エル・オトロ・センデロ(もう一つの道)』エルナンド・デ・ソト著(1986年)。 『ラテンアメリカの経済成長の再生に向けて』ベラ・バラッサ、ヘラルド・M・ブエノ、ペドロ・パブロ・クチンスキー、マリオ・エンリケ著(国際経済研究所、1986年)。 『ラテンアメリカの調整:これまでの成果』ジョン・ウィリアムソン編(国際経済研究所、1990年)。 ラテンアメリカにおけるポピュリズムのマクロ経済学、ルディガー・ドルンブッシュとセバスチャン・エドワーズ編(1991年)。 グローバル・リンケージ:世界経済におけるマクロ経済的相互依存と協力、ジェフリー・サックスとワーウィック・マッキビン著(1991年)。 『世界開発報告書 1991:開発という課題』ローレンス・サマーズ、ヴィノッド・トーマス他著(世界銀行、1991年)。 「開発と『ワシントン・コンセンサス』」『世界開発』第21巻:1329-1336、ジョン・ウィリアムソン著(1993年)。 「開発に関する最近の教訓」ローレンス・H・サマーズ&ヴィノッド・トーマス著 (1993)。 ラテンアメリカの市場への道:マクロ経済ショックから制度的治療へ、モイセス・ナイム著(1994)。 エコノミスタス・イ・ポリティコス:ラ・ポリティカ・デ・ラ・レフォルマ・エコノミカ、アグスティン・ファラス・サンタナ著(1996)。 グローバル資本主義の危機:危機に瀕する開かれた社会、ジョージ・ソロス著 (1997). トレードオフを超えて:ラテンアメリカにおける市場改革と公平な成長、ナンシー・バーズオール、キャロル・グラハム、リチャード・サボット編(ブルッキングス研究所、1998年)。 第三の道:社会民主主義の再生に向けて、アンソニー・ギデンズ著(1998年)。 レクサスとオリーブの木:グローバリゼーションを理解する、トーマス・フリードマン著(1999年)。 「経済改革における流行とファッション:ワシントン・コンセンサスか、ワシントン・コンフュージョンか?」、モイセス・ナイム著(IMF、1999年)。 『論争の的となるワシントン:ラテンアメリカの社会的公平のための経済政策』、ナンシー・バーズオール、アウグスト・デ・ラ・トーレ著(カーネギー国際平和財団、米州対話、2001年) 「 ワシントン・コンセンサスは失敗したか?」、ジョン・ウィリアムソン著(PIIE でのスピーチ、2002年)。 クシンスキー、ペドロ・パブロ、ウィリアムソン、ジョン編(2003)。『ワシントン・コンセンサスの後:ラテンアメリカにおける成長と改革の再始動』。ワシントン D.C.:国際経済研究所。ISBN 9780881324518。 ウィリアムソン、ジョン(2003)。「成長と改革を再開するための課題」(PDF)。クシンスキー、ペドロ・パブロ、ウィリアムソン、ジョン(編)。 『ワシントン・コンセンサス後:ラテンアメリカにおける成長と改革の再開』。ワシントン D.C.:国際経済研究所。ISBN 9780881324518。 メキシコにおける経済改革の実施:発展途上国のためのロードマップとしてのワシントン・コンセンサス テレンス・フルハーティ (2007) メキシコにおける経済改革の実施:発展途上国のためのロードマップとしてのワシントン・コンセンサス |

| Secondary sources Ip, Greg. (2021) "How Bidenomics Seeks to Remake the Economic Consensus: Declaring end to neoliberalism, new thinkers play down constraints of deficits, inflation and incentives" Wall Street Journal April 7, 2021 Risen, Clay. (2021) "John Williamson, 83, Dies; Economist Defined the ‘Washington Consensus': A careful pragmatist, he regretted the way his term, aimed at developing countries, was misinterpreted by free-market ideologues and anti-globalization activists." New York Times April 15, 2021 Babb, Sarah, and Alexander Kentikelenis. (2021) "People have long predicted the collapse of the Washington Consensus. It keeps reappearing under new guises: 30 years later, global financial institutions still condition loans on policies like 'structural reforms’" Washington Post April 16, 2021 Kläffling, David. (2021) "Quick & New: Washington consensus 2.0? The Washington consensus has for long time been the symbol of market liberalism. Now, there may be a 'new Washington consensus', writes Martin Sandbu from the Financial Times based on what the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank argue in recent publications around their traditional spring meetings." New Paradigm (April 12, 2021) Rodrik, Dani (2006). "Goodbye Washington Consensus, Hello Washington Confusion? A Review of the World Bank's Economic Growth in the 1990s: Learning from a Decade of Reform" (PDF). Journal of Economic Literature. 44 (4): 973–987. doi:10.1257/jel.44.4.973. JSTOR 30032391. Yergin, Daniel; Stanislaw, Joseph (2002). The Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780743229630. Retrieved July 3, 2015. Santiso, Carlos (2004). "The contentious Washington Consensus: Reforming the reforms in emerging markets". Review of International Political Economy. 11 (4): 828–844. doi:10.1080/0969229042000279810. JSTOR 4177523. S2CID 153363966. [1] Stability with Growth: Macroeconomics, Liberalization, and Development (Initiative for Policy Dialogue Series C) ; by Joseph E. Stiglitz, Jose Antonio Ocampo, Shari Spiegel, Ricardo French-Davis, and Deepak Nayyar; Oxford University Press 2006] Archived April 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Economic Crisis and Policy Choice: The Politics of Adjustment in the Third World, edited by Joan M. Nelson (1990). Crisis and Reform in Latin America: From Despair to Hope, by Sebastian Edwards (1995). Fault Lines of Democracy in Post-Transition Latin America, Felipe Agüero and Jeffrey Stark (1998). What Kind of Democracy? What Kind of Market? Latin America in the Age of Neoliberalism, by Philip D. Oxhorn and Graciela Ducatenzeiler (1998). Latin America Transformed: Globalization and Modernity, by Robert N. Gwynne and Cristóbal Kay (1999). The Internationalization of Palace Wars: Lawyers, Economists, and the Contest to Transform Latin American States, by Yves Dezalay and Bryant G. Garth (2002). FONDAD: Diversity in Development: Reconsidering the Washington Consensus, edited by Jan Joost Teunissen and Age Akkerman (2004). The Washington Consensus as Policy Prescription for Development (World Bank) What Should the World Bank Think about the Washington Consensus?, by John Williamson. Fabian Global Forum for Progressive Global Politics: The Washington Consensus, by Adam Lent. Unraveling the Washington Consensus, An Interview with Joseph Stiglitz Developing Brazil: overcoming the failure of the Washington consensus/ Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira/ Lynne Rienner Publishers,2009 |

二次情報源 Ip, Greg. (2021) 「バイデノミクスが経済コンセンサスの再構築を目指す方法:新自由主義の終焉を宣言し、新しい思想家たちは赤字、インフレ、インセンティブの制約を軽視する」 ウォールストリートジャーナル 2021年4月7日 ライゼン、クレイ。(2021) 「ジョン・ウィリアムソン、83歳で死去。経済学者、『ワシントン・コンセンサス』を定義した人物。慎重な実用主義者であり、発展途上国を対象とした彼の 用語が、自由市場イデオロギーや反グローバル化活動家によって誤解されたことを残念に思っていた。」 ニューヨーク・タイムズ 2021年4月15日 バブ、サラ、アレクサンダー・ケンティケレニス。(2021) 「人々は長い間、ワシントン・コンセンサスの崩壊を予測してきた。しかし、それは新しい姿で再び現れ続けている。30年経った今でも、世界の金融機関は 「構造改革」のような政策を融資の条件としている」 ワシントン・ポスト 2021年4月16日 クレッフリング、デビッド。(2021) 「クイック&ニュー:ワシントン・コンセンサス 2.0?ワシントン・コンセンサスは長い間、市場自由主義の象徴であった。今、国際通貨基金と世界銀行が、従来の春季会合に関する最近の出版物で主張して いることに基づいて、フィナンシャル・タイムズのマーティン・サンドゥが「新しいワシントン・コンセンサス」があるかもしれない、と書いている。ニュー・ パラダイム (2021年4月12日) ロドリック、ダニ(2006)。「さようなら、ワシントン・コンセンサス、こんにちは、ワシントン・コンフュージョン?1990年代の世界銀行の経済成長 に関するレビュー:10年にわたる改革から学んだこと」(PDF)。経済文献誌。44 (4): 973–987. doi:10.1257/jel.44.4.973. JSTOR 30032391. ヤーギン、ダニエル; スタニスラフ、ジョセフ (2002). 『支配の高み:世界経済をめぐる戦い』. ニューヨーク: サイモン&シュスター. ISBN 9780743229630. 2015年7月3日取得. サンティソ、カルロス (2004). 「論争の的となっているワシントン・コンセンサス:新興市場における改革の改革」『国際政治経済レビュー』11 (4): 828–844. doi:10.1080/0969229042000279810. JSTOR 4177523. S2CID 153363966. [1] 『成長と安定:マクロ経済学、自由化、そして開発』(政策対話イニシアチブシリーズ C); ジョセフ・E・スティグリッツ、ホセ・アントニオ・オカンポ、シャリ・スピーゲル、リカルド・フレンチ=デイヴィス、ディーパック・ナイヤー著; オックスフォード大学出版局 2006年] 2016年4月5日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ 経済危機と政策選択:第三世界の調整政策、ジョーン・M・ネルソン編(1990年)。 ラテンアメリカの危機と改革:絶望から希望へ、セバスチャン・エドワーズ著(1995年)。 移行期後のラテンアメリカの民主主義の断層、フェリペ・アグエロ、ジェフリー・スターク著(1998年)。 どのような民主主義か?どのような市場か?新自由主義時代のラテンアメリカ、フィリップ・D・オックスホーン、グラシエラ・ドゥカテンゼイラー著(1998年)。 変貌したラテンアメリカ:グローバル化と現代性、ロバート・N・グウィン、クリストバル・ケイ著(1999年)。 宮殿戦争の国際化:弁護士、経済学者、そしてラテンアメリカ諸国の変革をめぐる争い、イヴ・デザレイ、ブライアント・G・ガース著(2002年)。 FONDAD:開発における多様性:ワシントン・コンセンサスを再考する、ヤン・ヨスト・テウニセン、エイジ・アッカーマン編(2004年)。 開発のための政策処方箋としてのワシントン・コンセンサス(世界銀行) 世界銀行はワシントン・コンセンサスについてどう考えるべきか、ジョン・ウィリアムソン著。 進歩的なグローバル政治のためのファビアン・グローバル・フォーラム:ワシントン・コンセンサス、アダム・レント著。 ワシントン・コンセンサスの解明、ジョセフ・スティグリッツへのインタビュー 発展するブラジル:ワシントン・コンセンサスの失敗を克服する/ ルイス・カルロス・ブレッサー・ペレイラ/ リン・リエンナー出版社、2009年 |

| Bibliography Márquez, Laureano; Sanabria, Eduardo (2018). "La democracia pierde energía". Historieta de Venezuela: De Macuro a Maduro (1st ed.). Gráficas Pedrazas. ISBN 978-1-7328777-1-9. Rivero, Mirtha (2011). La rebelión de los náufragos (9th ed.). Alfa. ISBN 978-980-354-295-5. |

参考文献 マルケス、ラウレアノ;サナブリア、エドゥアルド(2018)。『民主主義は勢いを失う』。ベネズエラの漫画:マクロからマドゥロまで(第1版)。グラフィカス・ペドラサス。ISBN 978-1-7328777-1-9。 リベロ、ミルサ(2011)。『漂流者たちの反乱』(第9版)。アルファ。ISBN 978-980-354-295-5。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Washington_Consensus |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099