トランスヒューマニズム

Transhumanism

☆トランスヒューマニズム(Transhumanism)は、長寿、認知、幸福を大幅に向上させることが できる高度な技術を開発し、広く利用できるようにすることによって、人間の状態を向上させることを提唱する哲学的・知的運動である

| Transhumanism is a

philosophical and intellectual movement that advocates the enhancement

of the human condition by developing and making widely available

sophisticated technologies that can greatly enhance longevity,

cognition, and well-being.[1][2][3] Transhumanist thinkers study the potential benefits and dangers of emerging technologies that could overcome fundamental human limitations, as well as the ethics[4] of using such technologies. Some transhumanists believe that human beings may eventually be able to transform themselves into beings with abilities so greatly expanded from the current condition as to merit the label of posthuman beings.[2] Another topic of transhumanist research is how to protect humanity against existential risks, such as nuclear war or asteroid collision.[5][better source needed] Julian Huxley was a biologist who popularised the term transhumanism in a 1957 essay.[6] The contemporary meaning of the term "transhumanism" was foreshadowed by one of the first professors of futurology, a man who changed his name to FM-2030. In the 1960s, he taught "new concepts of the human" at The New School when he began to identify people who adopt technologies, lifestyles, and worldviews "transitional" to posthumanity as "transhuman".[7] The assertion would lay the intellectual groundwork for the British philosopher Max More to begin articulating the principles of transhumanism as a futurist philosophy in 1990, and organizing in California a school of thought that has since grown into the worldwide transhumanist movement.[7][8][9] Influenced by seminal works of science fiction, the transhumanist vision of a transformed future humanity has attracted many supporters and detractors from a wide range of perspectives, including philosophy and religion.[7] In 2017, Penn State University Press, in cooperation with philosopher Stefan Lorenz Sorgner and sociologist James Hughes, established the Journal of Posthuman Studies[10] as the first academic journal explicitly dedicated to the posthuman, with the goal of clarifying the notions of posthumanism and transhumanism, as well as comparing and contrasting both. Transhumanism is often compared, especially in the media, to the Nazi project to improve the race in a eugenic sense. This is denied by Sorgner: "It is also false to identify transhumanists with Nazi ideology, as Habermas does, because Nazis are in favor of a totalitarian political organization, whereas transhumanists uphold the value of liberal democracies."[11] |

トランスヒューマニズムは、長寿、認知、幸福を大幅に向上させることが

できる高度な技術を開発し、広く利用できるようにすることによって、人間の状態を向上させることを提唱する哲学的・知的運動である[1][2][3]。 トランスヒューマニストの思想家は、人間の根本的な限界を克服しうる新たなテクノロジーの潜在的な利点と危険性、またそのようなテクノロジーを使用するこ との倫理[4]について研究している。トランスヒューマニストの中には、人間はいずれポストヒューマンビーイングというレッテルを貼られるに値するほど、 現状から大きく拡張された能力を持つ存在へと変貌を遂げることができると考える者もいる[2]。 核戦争や小惑星の衝突といった存亡の危機から人類をいかにして守るかということもトランスヒューマニストの研究のテーマである[5][要出典]。 ジュリアン・ハクスリーは生物学者であり、1957年のエッセイでトランスヒューマニズムという言葉を広めた[6]。「トランスヒューマニズム」という言 葉の現代的な意味は、FM-2030と名前を変えた最初の未来学教授の一人によって予兆された。1960年代、ニュースクールで「人間の新しい概念」を教 えていた彼は、ポストヒューマニティに「過渡的」な技術、ライフスタイル、世界観を採用する人々を「トランスヒューマン」と認識し始めた[7]。この主張 は、イギリスの哲学者マックス・モアが1990年に未来派の哲学としてトランスヒューマニズムの原則を明確にし始め、カリフォルニアでそれ以降世界的なト ランスヒューマニズム運動へと成長した思想の学派を組織するための知的基盤を築くことになる[7][8][9]。 SFの代表作に影響を受けたトランスヒューマニズムのビジョンは、未来の人類を変革するというものであり、哲学や宗教を含む幅広い観点から多くの支持者と 否定者を集めている[7]。 2017年、ペンシルベニア州立大学出版局は、哲学者のステファン・ローレンツ・ソルグナー、社会学者のジェームズ・ヒューズと協力し、ポストヒューマニ ズムとトランスヒューマニズムの概念を明確にし、両者を比較対照することを目的として、ポストヒューマンを明示的に専門とする初の学術誌として「ポスト ヒューマン研究ジャーナル」[10]を創刊した。 トランスヒューマニズムは、特にメディアにおいて、優生学的な意味での人種改良を目指したナチスのプロジェクトと比較されることが多い。ソルグナーはこれ を否定する: 「ハーバーマスのように、トランスヒューマニズムをナチスのイデオロギーと同一視するのも誤りである。ナチスは全体主義的な政治組織を支持しているのに対 し、トランスヒューマニズムは自由民主主義の価値を支持しているからである」[11]。 |

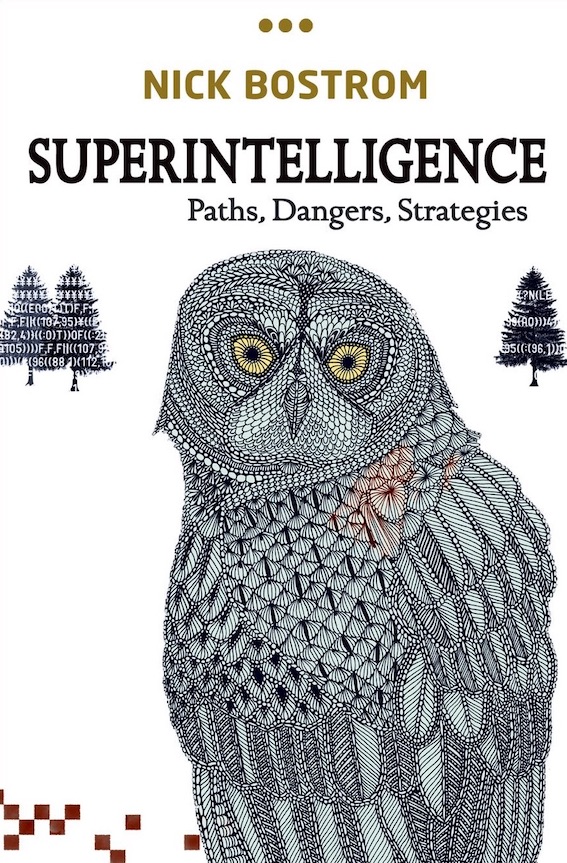

| History Precursors of transhumanism According to Nick Bostrom, transcendentalist impulses have been expressed at least as far back as the quest for immortality in the Epic of Gilgamesh, as well as in historical quests for the Fountain of Youth, the Elixir of Life, and other efforts to stave off aging and death.[2] Transhumanists draw upon and claim continuity from intellectual and cultural traditions such as the ancient philosophy of Aristotle or the scientific tradition of Roger Bacon.[12] In his Divine Comedy, Dante coined the word trasumanar meaning "to transcend human nature, to pass beyond human nature" in the first canto of Paradiso.[13][14][15][16] The interweaving of transhumanist aspirations with the scientific imagination can be seen in the works of some precursors of Enlightenment such as Francis Bacon.[17][18] One of the early precursors to transhumanist ideas is Discourse on Method (1637) by René Descartes. In the Discourse, Descartes envisioned a new kind of medicine that could grant both physical immortality and stronger minds.[19] In his first edition of Political Justice (1793), William Godwin included arguments favoring the possibility of "earthly immortality" (what would now be called physical immortality). Godwin explored the themes of life extension and immortality in his gothic novel St. Leon, which became popular (and notorious) at the time of its publication in 1799, but is now mostly forgotten. St. Leon may have provided inspiration for his daughter Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein.[20] Ether Day, marking a significant milestone in human history, celebrated its 175th anniversary on October 16, 2021. It was on this day that dentist William T. G. Morton achieved a groundbreaking feat by administering the first public ether anesthesia in Boston. This breakthrough not only allowed for the alleviation of pain with a reasonable level of risk but also helped safeguard individuals from psychological trauma by inducing unconsciousness.[21] There is debate about whether the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche can be considered an influence on transhumanism, despite its exaltation of the Übermensch (overhuman), due to its emphasis on self-actualization rather than technological transformation.[2][22][23][24] The transhumanist philosophies of Max More and Stefan Lorenz Sorgner have been influenced strongly by Nietzschean thinking.[22] By way of contrast, The Transhumanist Declaration "...advocates the well-being of all sentience (whether in artificial intellects, humans, posthumans, or non-human animals)".[25] The late 19th to early 20th century movement known as Russian cosmism, by Russian philosopher N. F. Fyodorov, is noted for anticipating transhumanist ideas.[26] In 1966, FM-2030 (formerly F. M. Esfandiary), a futurist who taught "new concepts of the human" at The New School, in New York City, began to identify people who adopt technologies, lifestyles and worldviews transitional to posthumanity as "transhuman".[27] Early transhumanist thinking  Julian Huxley, the biologist who popularised the term transhumanism in an influential 1957 essay[6] Fundamental ideas of transhumanism were first advanced in 1923 by the British geneticist J. B. S. Haldane in his essay Daedalus: Science and the Future, which predicted that great benefits would come from the application of advanced sciences to human biology—and that every such advance would first appear to someone as blasphemy or perversion, "indecent and unnatural".[28] In particular, he was interested in the development of the science of eugenics, ectogenesis (creating and sustaining life in an artificial environment), and the application of genetics to improve human characteristics, such as health and intelligence. His article inspired academic and popular interest. J. D. Bernal, a crystallographer at Cambridge, wrote The World, the Flesh and the Devil in 1929, in which he speculated on the prospects of space colonization and radical changes to human bodies and intelligence through bionic implants and cognitive enhancement.[29] These ideas have been common transhumanist themes ever since.[2] The biologist Julian Huxley is generally regarded as the founder of transhumanism after using the term for the title of an influential 1957 article.[6] The term itself, however, derives from an earlier 1940 paper by the Canadian philosopher W. D. Lighthall.[30] Huxley describes transhumanism in these terms: Up till now human life has generally been, as Hobbes described it, "nasty, brutish and short"; the great majority of human beings (if they have not already died young) have been afflicted with misery… we can justifiably hold the belief that these lands of possibility exist, and that the present limitations and miserable frustrations of our existence could be in large measure surmounted… The human species can, if it wishes, transcend itself—not just sporadically, an individual here in one way, an individual there in another way, but in its entirety, as humanity.[6] Huxley's definition differs, albeit not substantially, from the one commonly in use since the 1980s. The ideas raised by these thinkers were explored in the science fiction of the 1960s, notably in Arthur C. Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey, in which an alien artifact grants transcendent power to its wielder.[31] Japanese Metabolist architects produced a manifesto in 1960 which outlined goals to "encourage active metabolic development of our society"[32] through design and technology. In the Material and Man section of the manifesto, Noboru Kawazoe suggests that: After several decades, with the rapid progress of communication technology, every one will have a "brain wave receiver" in his ear, which conveys directly and exactly what other people think about him and vice versa. What I think will be known by all the people. There is no more individual consciousness, only the will of mankind as a whole.[33] Artificial intelligence and the technological singularity The concept of the technological singularity, or the ultra-rapid advent of superhuman intelligence, was first proposed by the British cryptologist I. J. Good in 1965: Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an "intelligence explosion," and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make.[34] Computer scientist Marvin Minsky wrote on relationships between human and artificial intelligence beginning in the 1960s.[35] Over the succeeding decades, this field continued to generate influential thinkers such as Hans Moravec and Raymond Kurzweil, who oscillated between the technical arena and futuristic speculations in the transhumanist vein.[36][37] The coalescence of an identifiable transhumanist movement began in the last decades of the 20th century. In 1972, Robert Ettinger, whose 1964 Prospect of Immortality founded the cryonics movement,[38] contributed to the conceptualization of "transhumanity" with his 1972 Man into Superman.[39] FM-2030 published the Upwingers Manifesto in 1973.[40] Growth of transhumanism The first self-described transhumanists met formally in the early 1980s at the University of California, Los Angeles, which became the main center of transhumanist thought. Here, FM-2030 lectured on his "Third Way" futurist ideology.[41] At the EZTV Media venue, frequented by transhumanists and other futurists, Natasha Vita-More presented Breaking Away, her 1980 experimental film with the theme of humans breaking away from their biological limitations and the Earth's gravity as they head into space.[42][43] FM-2030 and Vita-More soon began holding gatherings for transhumanists in Los Angeles, which included students from FM-2030's courses and audiences from Vita-More's artistic productions. In 1982, Vita-More authored the Transhumanist Arts Statement[44] and, six years later, produced the cable TV show TransCentury Update on transhumanity, a program which reached over 100,000 viewers. In 1986, Eric Drexler published Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology,[45] which discussed the prospects for nanotechnology and molecular assemblers, and founded the Foresight Institute. As the first non-profit organization to research, advocate for, and perform cryonics, the Southern California offices of the Alcor Life Extension Foundation became a center for futurists. In 1988, the first issue of Extropy Magazine was published by Max More and Tom Morrow. In 1990, More, a strategic philosopher, created his own particular transhumanist doctrine, which took the form of the Principles of Extropy, and laid the foundation of modern transhumanism by giving it a new definition:[46] Transhumanism is a class of philosophies that seek to guide us towards a posthuman condition. Transhumanism shares many elements of humanism, including a respect for reason and science, a commitment to progress, and a valuing of human (or transhuman) existence in this life. [...] Transhumanism differs from humanism in recognizing and anticipating the radical alterations in the nature and possibilities of our lives resulting from various sciences and technologies [...]. In 1992, More and Morrow founded the Extropy Institute, a catalyst for networking futurists and brainstorming new memeplexes by organizing a series of conferences and, more importantly, providing a mailing list, which exposed many to transhumanist views for the first time during the rise of cyberculture and the cyberdelic counterculture. In 1998, philosophers Nick Bostrom and David Pearce founded the World Transhumanist Association (WTA), an international non-governmental organization working toward the recognition of transhumanism as a legitimate subject of scientific inquiry and public policy.[47] In 2002, the WTA modified and adopted The Transhumanist Declaration.[25][48][5] The Transhumanist FAQ, prepared by the WTA (later Humanity+), gave two formal definitions for transhumanism:[49] The intellectual and cultural movement that affirms the possibility and desirability of fundamentally improving the human condition through applied reason, especially by developing and making widely available technologies to eliminate aging and to greatly enhance human intellectual, physical, and psychological capacities. The study of the ramifications, promises, and potential dangers of technologies that will enable us to overcome fundamental human limitations, and the related study of the ethical matters involved in developing and using such technologies. In possible contrast with other transhumanist organizations, WTA officials considered that social forces could undermine their futurist visions and needed to be addressed.[7] A particular concern is the equal access to human enhancement technologies across classes and borders.[50] In 2006, a political struggle within the transhumanist movement between the libertarian right and the liberal left resulted in a more centre-leftward positioning of the WTA under its former executive director James Hughes.[50][51] In 2006, the board of directors of the Extropy Institute ceased operations of the organization, stating that its mission was "essentially completed".[52] This left the World Transhumanist Association as the leading international transhumanist organization. In 2008, as part of a rebranding effort, the WTA changed its name to "Humanity+".[53] In 2012, the transhumanist Longevity Party had been initiated as an international union of people who promote the development of scientific and technological means to significant life extension, that for now has more than 30 national organisations throughout the world.[54][55] The Mormon Transhumanist Association was founded in 2006.[56] By 2012, it consisted of hundreds of members.[57] The first transhumanist elected member of a parliament has been Giuseppe Vatinno, in Italy.[58] |

歴史 トランスヒューマニズムの先駆け ニック・ボストロムによれば、超越主義的な衝動は、少なくともギルガメシュ叙事詩における不老不死の探求や、若さの泉、不老不死の薬、その他老化や死を食 い止めようとする歴史的な探求にまで遡り表現されてきた[2]。 トランスヒューマニストは、アリストテレスの古代哲学やロジャー・ベーコンの科学的伝統といった知的・文化的伝統に依拠し、その連続性を主張している [12]。ダンテは『神曲』において、『パラディソ』の第1カントで「人間性を超越する、人間性を超える」を意味するtrasumanarという言葉を 作った[13][14][15][16]。 フランシス・ベーコン[17][18]のような啓蒙主義の先駆者たちの作品には、トランスヒューマニズムの願望と科学的想像力が織り交ざっていることが見 て取れる。デカルトは『方法論』の中で、肉体的な不死と精神的な強さの両方を与えることができる新しい種類の医学を構想していた[19]。 ウィリアム・ゴドウィンは『ポリティカル・ジャスティス』(1793年)の初版で、「地上的不死」(現在では肉体的不死と呼ばれるもの)の可能性を支持す る議論を盛り込んだ。ゴドウィンはゴシック小説『セント・レオン』で延命と不死のテーマを探求し、1799年の出版当時は人気を博した(そして悪名高い) が、現在ではほとんど忘れ去られている。セント・レオンは、娘のメアリー・シェリーの小説『フランケンシュタイン』にインスピレーションを与えたかもしれ ない[20]。 人類の歴史における重要な節目を示すエーテルの日は、2021年10月16日に175周年を迎えた。この日、歯科医のウィリアム・T・G・モートンがボス トンで初めて公開エーテル麻酔を行い、画期的な偉業を成し遂げた。この画期的な発明は、妥当なリスクレベルで痛みを和らげることを可能にしただけでなく、 無意識を誘発することで心理的外傷から個人を守ることにも役立った[21]。 フリードリッヒ・ニーチェの哲学は、超人間(Übermensch)を称揚しているにもかかわらず、技術的変革よりも自己実現に重きを置いているため、ト ランスヒューマニズムに影響を与えたとみなすことができるかどうかについては議論がある。 [2][22][23][24]マックス・モアとシュテファン・ローレンツ・ソルグナーのトランスヒューマニズム哲学はニーチェ思想の影響を強く受けてい る[22]。 19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけてのロシアの哲学者N.F.フョードロフによるロシア宇宙論として知られる運動は、トランスヒューマニズムの思想を先取 りしていたことで知られている[26]。 1966年、ニューヨークのニュースクールで「人間の新しい概念」を教えていた未来学者FM-2030(旧F.M.エスファンディアリー)は、ポスト ヒューマニティに過渡的な技術、ライフスタイル、世界観を採用する人々を「トランスヒューマン」として特定し始めた[27]。 初期のトランスヒューマニズムの考え方 1957年の影響力のあるエッセイ[6]でトランスヒューマニズムという言葉を広めた生物学者ジュリアン・ハクスリー。 トランスヒューマニズムの基本的な考え方は、1923年にイギリスの遺伝学者であるJ.B.S.ハルデインによって初めて提唱されたエッセイ『ダイダロ ス:科学と未来』において、先端科学を人間の生物学に応用することによって大きな利益がもたらされ、そのような進歩はすべて、まず誰かにとっては冒涜や倒 錯、「わいせつで不自然」なものとして映るだろうと予測していた。 [28] 特に彼は、優生学、体外発生(人工的な環境で生命を創造し維持すること)、健康や知能といった人間の特性を改善するための遺伝学の応用といった科学の発展 に関心を寄せていた。 彼の論文は学術的にも一般的にも大きな関心を呼んだ。ケンブリッジ大学の結晶学者であったJ.D.バーナルは、1929年に『世界と肉体と悪魔』を執筆 し、その中で宇宙植民地化の展望や、バイオニック・インプラントや認知機能強化による人間の身体や知能の根本的な変化について推測している[29]。これ らの考えは、それ以来、トランスヒューマニズムの共通のテーマとなっている[2]。  生物学者ジュリアン・ハクスリーは、1957年の影響力のある論文のタイトルにこの言葉を使用したことから、一般的にトランスヒューマニズムの創始者とみ なされている[6]。しかし、この言葉自体は、カナダの哲学者W・D・ライトホールが1940年に発表した論文に由来している[30]: これまで人間の人生は、ホッブズが表現したように、一般的に「厄介で、残忍で、短い」ものであった。人類という種は、もし望むならば、自分自身を超越する ことができる。 [6] ハクスリーの定義は、1980年代以降に一般的に使われている定義とは、実質的ではないものの異なっている。これらの思想家たちによって提起されたアイデ アは、1960年代のSF、特にアーサー・C・クラークの『2001年宇宙の旅』において探求された。 日本のメタボリストの建築家たちは1960年にマニフェストを作成し、デザインとテクノロジーを通じて「私たちの社会の積極的な代謝的発展を奨励する」 [32]という目標を概説した。マニフェストの「物質と人間」のセクションで、川添登は次のように提言している: 数十年後、通信技術の急速な進歩に伴い、誰もが自分の耳に「脳波受信機」を装着し、他人が自分についてどう考えているかを直接正確に伝えるようになるだろ う。私が考えていることは、すべての人が知ることになる。個人の意識はなくなり、人類全体の意志だけが存在する。 人工知能と技術的特異点 技術的特異点、すなわち超人的知性の超高速出現という概念は、1965年にイギリスの暗号学者I・J・グッドによって初めて提唱された: 超知的機械とは、どんなに賢い人間の知的活動を遥かに凌駕する機械と定義しよう。機械の設計も知的活動の一つであるから、超知的機械はさらに優れた機械を 設計することができる。そうなれば、間違いなく「知性の爆発」が起こり、人間の知性ははるか後方に取り残されるだろう。したがって、最初の超知的機械は、 人間が作る必要のある最後の発明なのである[34]。 その後数十年にわたり、この分野はハンス・モラヴェックやレイモンド・カーツヴァイルといった影響力のある思想家を生み出し続け、彼らは技術的な領域とト ランスヒューマニズムの流れを汲む未来的な思索との間で揺れ動いた。1964年に『不死の展望』で人体冷凍保存運動を創設したロバート・エッティンガー [38]は、1972年に『人間をスーパーマンに』で「トランスヒューマニティ」の概念化に貢献した[39]。 トランスヒューマニズムの成長 最初の自称トランスヒューマニストたちは、1980年代初頭にカリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校で正式に会合した。ここでFM-2030は彼の「第三の 道」未来主義思想について講義を行った[41]。 トランスヒューマニストや他の未来主義者がよく訪れるEZTVメディアの会場で、ナターシャ・ヴィタ=モアは1980年に彼女が製作した実験映画『ブレイ キング・アウェイ』を発表した。 [42][43]FM-2030とヴィタ=モアはすぐに、FM-2030の講座の受講生やヴィタ=モアの芸術作品の観客を含むトランスヒューマニストのた めの集会をロサンゼルスで開催し始めた。1982年、ヴィタ=モアは「トランスヒューマニスト・アーツ・ステートメント」[44]を執筆し、6年後には ケーブルテレビでトランスヒューマニティに関する番組「TransCentury Update」を制作し、10万人以上の視聴者を獲得した。 1986年、エリック・ドレクスラーは『創造のエンジン』を出版した: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology』[45]を出版し、ナノテクノロジーと分子集合体の展望を論じ、フォーサイト研究所を設立した。クライオニクスの研究、提 唱、実施を行う最初の非営利団体として、アルコー延命財団の南カリフォルニア事務所は未来学者の中心地となった。1988年、マックス・モアとトム・モ ローによって『エクストロピー・マガジン』が創刊された。1990年、戦略哲学者であったモアは、「エクストロピーの原則」という形をとった彼独自のトラ ンスヒューマニズムの教義を生み出し、新しい定義を与えることによって、現代のトランスヒューマニズムの基礎を築いた[46]。 トランスヒューマニズムとは、ポストヒューマンな状態へと私たちを導こうとする哲学の一群である。トランスヒューマニズムは、理性と科学の尊重、進歩への コミットメント、現世における人間(あるいはトランスヒューマン)の存在の価値など、ヒューマニズムと多くの要素を共有している。[トランスヒューマニズ ムがヒューマニズムと異なるのは、さまざまな科学技術によってもたらされる、私たちの生活の本質と可能性の根本的な変化を認識し、予期している点である。 1992年、モアとモローはエクストロピー・インスティテュートを設立し、一連の会議を開催し、さらに重要なこととしてメーリングリストを提供すること で、未来学者をネットワーク化し、新たなミームプレックスをブレインストーミングする触媒となった。1998年、哲学者のニック・ボストロムとデイヴィッ ド・ピアースは、世界トランスヒューマニスト協会(WTA)を設立した。2002年、WTAはトランスヒューマニスト宣言を修正し、採択した。 応用理性によって人間の状態を根本的に改善する可能性と望ましさを肯定する知的・文化的運動、特に老化をなくし、人間の知的・身体的・心理的能力を大幅に 向上させる技術を開発し、広く利用できるようにすること。 人間の根本的な限界を克服することを可能にする技術の影響、約束、潜在的な危険性の研究、およびそのような技術の開発と使用に関連する倫理的事項の研究。 他のトランスヒューマニスト団体とは対照的に、WTAの関係者は、社会的な力が未来主義的なビジョンを損なう可能性があり、それに対処する必要があると考 えた。 [50]2006年、トランスヒューマニスト運動におけるリバタリアン右派とリベラル左派の政治闘争の結果、前事務局長ジェームズ・ヒューズの下、WTA はより中道左派的な位置づけとなった[50][51]。2006年、エクストロピー・インスティテュートの理事会は、その使命は「基本的に完了した」とし て、組織の運営を停止した[52]。2008年、リブランディングの一環として、WTAはその名称を「Humanity+」に変更した[53]。2012 年、トランスヒューマニスト長寿党は、大幅な延命のための科学的・技術的手段の開発を推進する人々の国際的な連合体として発足し、現在では世界中に30以 上の国内組織を有している[54][55]。 モルモン・トランスヒューマニスト協会は2006年に設立され[56]、2012年までに数百人のメンバーで構成されている[57]。 トランスヒューマニストとして初めて国会議員に選出されたのは、イタリアのジュゼッペ・ヴァティーノである[58]。 |

| Theory It is a matter of debate whether transhumanism is a branch of posthumanism and how this philosophical movement should be conceptualised with regard to transhumanism.[59][60] The latter is often referred to as a variant or activist form of posthumanism by its conservative,[61] Christian[62] and progressive[63][64] critics.[65] A common feature of transhumanism and philosophical posthumanism is the future vision of a new intelligent species, into which humanity will evolve and eventually will supplement or supersede it. Transhumanism stresses the evolutionary perspective, including sometimes the creation of a highly intelligent animal species by way of cognitive enhancement (i.e. biological uplift),[7] but clings to a "posthuman future" as the final goal of participant evolution.[66][67] Nevertheless, the idea of creating intelligent artificial beings (proposed, for example, by roboticist Hans Moravec) has influenced transhumanism.[36] Moravec's ideas and transhumanism have also been characterised as a "complacent" or "apocalyptic" variant of posthumanism and contrasted with "cultural posthumanism" in humanities and the arts.[68] While such a "cultural posthumanism" would offer resources for rethinking the relationships between humans and increasingly sophisticated machines, transhumanism and similar posthumanisms are, in this view, not abandoning obsolete concepts of the "autonomous liberal subject", but are expanding its "prerogatives" into the realm of the posthuman.[69] Transhumanist self-characterisations as a continuation of humanism and Enlightenment thinking correspond with this view. Some secular humanists conceive transhumanism as an offspring of the humanist freethought movement and argue that transhumanists differ from the humanist mainstream by having a specific focus on technological approaches to resolving human concerns (i.e. technocentrism) and on the issue of mortality.[70] However, other progressives have argued that posthumanism, whether it be its philosophical or activist forms, amounts to a shift away from concerns about social justice, from the reform of human institutions and from other Enlightenment preoccupations, toward narcissistic longings for a transcendence of the human body in quest of more exquisite ways of being.[71] As an alternative, humanist philosopher Dwight Gilbert Jones has proposed a renewed Renaissance humanism through DNA and genome repositories, with each individual genotype (DNA) being instantiated as successive phenotypes (bodies or lives via cloning, Church of Man, 1978). In his view, native molecular DNA "continuity" is required for retaining the "self" and no amount of computing power or memory aggregation can replace the essential "stink" of our true genetic identity, which he terms "genity". Instead, DNA/genome stewardship by an institution analogous to the Jesuits' 400 year vigil is a suggested model for enabling humanism to become our species' common credo, a project he proposed in his speculative novel The Humanist – 1000 Summers (2011), wherein humanity dedicates these coming centuries to harmonizing our planet and peoples. The philosophy of transhumanism is closely related to technoself studies, an interdisciplinary domain of scholarly research dealing with all aspects of human identity in a technological society and focusing on the changing nature of relationships between humans and technology.[72] Aims You awake one morning to find your brain has another lobe functioning. Invisible, this auxiliary lobe answers your questions with information beyond the realm of your own memory, suggests plausible courses of action, and asks questions that help bring out relevant facts. You quickly come to rely on the new lobe so much that you stop wondering how it works. You just use it. This is the dream of artificial intelligence.— Byte, April 1985[73]  Ray Kurzweil believes that a countdown to when "human life will be irreversibly transformed" can be made through plotting major world events on a graph. While many transhumanist theorists and advocates seek to apply reason, science and technology for the purposes of reducing poverty, disease, disability and malnutrition around the globe,[49] transhumanism is distinctive in its particular focus on the applications of technologies to the improvement of human bodies at the individual level. Many transhumanists actively assess the potential for future technologies and innovative social systems to improve the quality of all life, while seeking to make the material reality of the human condition fulfill the promise of legal and political equality by eliminating congenital mental and physical barriers. Transhumanist philosophers argue that there not only exists a perfectionist ethical imperative for humans to strive for progress and improvement of the human condition, but that it is possible and desirable for humanity to enter a transhuman phase of existence in which humans enhance themselves beyond what is naturally human. In such a phase, natural evolution would be replaced with deliberate participatory or directed evolution. Some theorists such as Ray Kurzweil think that the pace of technological innovation is accelerating and that the next 50 years may yield not only radical technological advances, but possibly a technological singularity, which may fundamentally change the nature of human beings.[74] Transhumanists who foresee this massive technological change generally maintain that it is desirable. However, some are also concerned with the possible dangers of extremely rapid technological change and propose options for ensuring that advanced technology is used responsibly. For example, Bostrom has written extensively on existential risks to humanity's future welfare, including ones that could be created by emerging technologies.[75] In contrast, some proponents of transhumanism view it as essential to humanity's survival. For instance, Stephen Hawking points out that the "external transmission" phase of human evolution, where knowledge production and knowledge management is more important than transmission of information via evolution, may be the point at which human civilization becomes unstable and self-destructs, one of Hawking's explanations for the Fermi paradox. To counter this, Hawking emphasizes either self-design of the human genome or mechanical enhancement (e.g., brain-computer interface) to enhance human intelligence and reduce aggression, without which he implies human civilization may be too stupid collectively to survive an increasingly unstable system, resulting in societal collapse.[76] While many people believe that all transhumanists are striving for immortality, it is not necessarily true. Hank Pellissier, managing director of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies (2011–2012), surveyed transhumanists. He found that, of the 818 respondents, 23.8% did not want immortality.[77] Some of the reasons argued were boredom, Earth's overpopulation and the desire "to go to an afterlife".[77] Empathic fallibility and conversational consent See also: Uplift (science fiction) Certain transhumanist philosophers hold that since all assumptions about what others experience are fallible, and that therefore all attempts to help or protect beings that are not capable of correcting what others assume about them no matter how well-intentioned are in danger of actually hurting them, all sentient beings deserve to be sapient. These thinkers argue that the ability to discuss in a falsification-based way constitutes a threshold that is not arbitrary at which it becomes possible for an individual to speak for themselves in a way that is not dependent on exterior assumptions. They also argue that all beings capable of experiencing something deserve to be elevated to this threshold if they are not at it, typically stating that the underlying change that leads to the threshold is an increase in the preciseness of the brain's ability to discriminate. This includes increasing the neuron count and connectivity in animals as well as accelerating the development of connectivity to shorten or ideally skip non-sapient childhood incapable of independently deciding for oneself. Transhumanists of this description stress that the genetic engineering that they advocate is general insertion into both the somatic cells of living beings and in germ cells, and not purging of individuals without the modifications, deeming the latter not only unethical but also unnecessary due to the possibilities of efficient genetic engineering.[78][79][80][81] |

理論 トランスヒューマニズムがポストヒューマニズムの一派であるかどうか、またこの哲学的運動がトランスヒューマニズムに対してどのように概念化されるべきか は議論の分かれるところである[59][60]。後者は保守的[61]、キリスト教的[62]、進歩的[63][64]な批評家たちによって、しばしばポ ストヒューマニズムの変種あるいは活動的形態と呼ばれている[65]。 トランスヒューマニズムと哲学的ポストヒューマニズムに共通する特徴は、人類が進化し、最終的には人類を補完するか、人類に取って代わる新たな知的種族の 未来像である。トランスヒューマニズムは、時には認知機能の強化(すなわち生物学的な向上)によって高度に知的な動物種を創造することも含めて、進化の視 点を強調する[7]が、参加者の進化の最終的な目標として「ポストヒューマンの未来」に固執している[66][67]。 とはいえ、(例えばロボット工学者であるハンス・モラヴェックによって提唱された)知的な人工生命を創造するという考えはトランスヒューマニズムに影響を 与えている[36]。モラヴェックの考えやトランスヒューマニズムはまた、ポストヒューマニズムの「自己満足的」あるいは「終末論的」な変種として特徴づ けられ、人文学や芸術における「文化的ポストヒューマニズム」と対比されている。 [このような「文化的ポストヒューマニズム」は、人間と高度化する機械との関係を再考するためのリソースを提供する一方で、トランスヒューマニズムや類似 のポストヒューマニズムは、「自律した自由主義的主体」の時代遅れの概念を放棄しているのではなく、ポストヒューマンの領域へとその「特権」を拡大してい るのである[69]。 世俗的なヒューマニストの中には、トランスヒューマニズムをヒューマニストの自由思想運動から生まれたものと考え、トランスヒューマニストは、人間の問題 を解決するための技術的アプローチ(すなわち技術中心主義)と死生観の問題に特定の焦点を当てることによって、ヒューマニストの主流とは異なると主張する 者もいる。 [70]しかしながら、他の進歩主義者たちは、ポストヒューマニズムは、それが哲学的な形態であれ活動的な形態であれ、社会正義に関する懸念や人間機構の 改革、その他の啓蒙主義的な関心から、より精妙な存在のあり方を求めて人間の肉体の超越を求める自己愛的な憧れへとシフトするものであると主張している [71]。 代替案として、ヒューマニスト哲学者のドワイト・ギルバート・ジョーンズは、DNAとゲノムのリポジトリを通じて、個々の遺伝子型(DNA)が連続する表 現型(クローンによる身体や生命、Church of Man、1978年)としてインスタンス化される、新たなルネサンス・ヒューマニズムを提案している。彼の見解によれば、「自己」を保持するためには、分 子DNAの「連続性」が必要であり、いくらコンピューティング・パワーやメモリーを集約しても、彼が「ジェニティ」と呼ぶ、私たちの真の遺伝的アイデン ティティの本質的な「臭い」に取って代わることはできない。その代わりに、イエズス会の400年警護に類似した組織によるDNA/ゲノム管理は、ヒューマ ニズムを私たちの種の共通の信条とするための提案モデルであり、人類がこの先の数世紀を地球と民族の調和に捧げるというプロジェクトを、彼は推理小説 『ヒューマニスト-1000の夏』(2011年)で提案している。 トランスヒューマニズムの哲学は、テクノロジー社会における人間のアイデンティティのあらゆる側面を扱い、人間とテクノロジーの関係性の変化に焦点を当てた学際的な研究領域であるテクノセルフ・スタディーズと密接に関連している[72]。 目的 ある朝目覚めると、脳がもう一つの葉として機能していることに気づく。この補助葉は目に見えないが、自分の記憶の範疇を超えた情報を使ってあなたの質問に 答え、もっともらしい行動指針を提案し、関連する事実を引き出すのに役立つ質問をする。あなたはすぐに新しい葉に頼るようになり、それがどのように機能す るのか不思議に思わなくなる。ただ使うだけだ。これが人工知能の夢なのだ。- 『バイト』1985年4月号[73]  レイ・カーツワイルは、世界の主要な出来事をグラフにプロットすることで、「人間の生活が不可逆的に変化する」時期のカウントダウンができると考えている。 トランスヒューマニズムの理論家や提唱者の多くは、世界中の貧困、病気、障害、栄養失調を減らす目的で、理性、科学、技術を応用しようとしているが [49]、トランスヒューマニズムは、個人レベルでの人体の改善への技術の応用に特に焦点を当てている点で特徴的である。多くのトランスヒューマニスト は、未来のテクノロジーや革新的な社会システムが、あらゆる生活の質を向上させる可能性を積極的に評価する一方で、先天的な精神的・肉体的障壁を取り除く ことによって、人間の物質的現実が法的・政治的平等の約束を果たすようにすることを求めている。 トランスヒューマニズムの哲学者たちは、人間には進歩や人間状態の改善に努めるという完全主義的な倫理的要請が存在するだけでなく、人間が本来人間である 以上に自らを高めるトランスヒューマンな存在の段階に入ることは可能であり、望ましいことであると主張する。そのような段階では、自然進化は意図的な参加 型進化や指示型進化に取って代わられるだろう。 レイ・カーツワイルのような理論家の中には、技術革新のペースが加速しており、今後50年の間に、急激な技術進歩がもたらされるだけでなく、もしかすると 技術的特異点(シンギュラリティ)が発生し、人間の本質が根本的に変わるかもしれないと考えている者もいる[74]。このような大規模な技術的変化を予見 するトランスヒューマニストは、一般的にそれが望ましいと主張している。しかし、極めて急速な技術革新がもたらしうる危険性を懸念し、先端技術が責任を 持って使用されるようにするための選択肢を提案する者もいる。例えば、ボストロムは、新たなテクノロジーによって生み出される可能性のあるものを含め、人 類の将来の福祉に対する実存的リスクについて広範に執筆している[75]。対照的に、トランスヒューマニズムの支持者の中には、トランスヒューマニズムを 人類の生存に不可欠なものとみなす者もいる。例えば、スティーヴン・ホーキングは、進化による情報の伝達よりも知識の生産と知識管理の方が重要である人類 の進化の「外部伝達」段階は、人類の文明が不安定になり自滅する時点かもしれないと指摘しており、これはホーキングによるフェルミのパラドックスの説明の ひとつである。これに対抗するために、ホーキング博士はヒトゲノムの自己設計か、人間の知性を高めて攻撃性を低下させるための機械的強化(例えば、ブレイ ン・コンピューター・インターフェイス)を強調している。 トランスヒューマニストはみな不老不死を目指していると考える人が多いが、必ずしもそうではない。Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologiesのマネージングディレクターであるハンク・ペリシエは、2011年から2012年にかけて、トランスヒューマニストを調査した。 その結果、818人の回答者のうち23.8%が不老不死を望んでいないことがわかった[77]。その理由としては、退屈、地球の人口過剰、「死後の世界に 行きたい」という願望などが主張されている[77]。 共感的誤謬性と会話の同意 こちらも参照: アップリフト(SF) ある種のトランスヒューマニスト哲学者は、他者が経験することについての仮定はすべて誤りうるものであり、したがって、他者が自分について仮定することを 修正する能力のない存在を助けたり保護しようとする試みは、どんなに善意であっても、実際にその存在を傷つける危険性があるため、すべての知覚を持つ生物 はサピエントであるに値すると主張する。これらの思想家は、改竄に基づく方法で議論する能力は、外的な仮定に依存しない方法で個人が自分自身のために話す ことが可能になる、恣意的ではない閾値を構成していると主張する。彼らはまた、何かを経験することができるすべての存在は、もし閾値に達していないのであ れば、この閾値まで引き上げられるに値すると主張し、典型的には、閾値をもたらす根本的な変化は、脳の識別能力の精度の向上であると述べている。これに は、動物におけるニューロン数の増加や連結性の向上、連結性の発達を加速させ、自分で判断できない非利口な子供時代を短縮したり、理想的にはスキップする ことも含まれる。このような記述のトランスヒューマニストは、彼らが提唱する遺伝子工学は、生物の体細胞と生殖細胞の両方への一般的な挿入であり、改変の ない個体のパージではないことを強調し、後者は非倫理的であるだけでなく、効率的な遺伝子工学の可能性のために不必要であるとみなす[78][79] [80][81]。 |

| Ethics Transhumanists engage in interdisciplinary approaches to understand and evaluate possibilities for overcoming biological limitations by drawing on futurology and various fields of ethics.[citation needed] Unlike many philosophers, social critics and activists who place a moral value on preservation of natural systems, transhumanists see the very concept of the specifically natural as problematically nebulous at best and an obstacle to progress at worst.[82] In keeping with this, many prominent transhumanist advocates, such as Dan Agin, refer to transhumanism's critics, on the political right and left jointly, as "bioconservatives" or "bioluddites", the latter term alluding to the 19th century anti-industrialisation social movement that opposed the replacement of human manual labourers by machines.[83] A belief of counter-transhumanism is that transhumanism can cause unfair human enhancement in many areas of life, but specifically on the social plane. This can be compared to steroid use, where athletes who use steroids in sports have an advantage over those who do not. The same scenario happens when people have certain neural implants that give them an advantage in the work place and in educational aspects.[84] Additionally, there are many, according to M.J. McNamee and S.D. Edwards, who fear that the improvements afforded by a specific, privileged section of society will lead to a division of the human species into two different and distinct species.[85] The idea of two human species, one being at a great physical and economic advantage in comparison with the other, is a troublesome one at best. One may be incapable of breeding with the other, and may by consequence of lower physical health and ability, be considered of a lower moral standing than the other.[85] Nick Bostrom stated that transhumanism advocates for the wellbeing of all sentient beings, whether in non-human animals, extra-terrestrials or artificial forms of life.[86] This view is reiterated by David Pearce, who advocates for the use of biotechnology to eradicate suffering in all sentient beings.[87] Currents There is a variety of opinions within transhumanist thought. Many of the leading transhumanist thinkers hold views that are under constant revision and development.[88] Some distinctive currents of transhumanism are identified and listed here in alphabetical order: Abolitionism, the concept of using biotechnology to eradicate suffering in all sentient beings.[87] Democratic transhumanism, a political ideology synthesizing liberal democracy, social democracy, radical democracy and transhumanism.[89] Equalism, a socioeconomic theory based upon the idea that emerging technologies will put an end to social stratification through even distribution of resources in the technological singularity era.[90] Extropianism, an early school of transhumanist thought characterized by a set of principles advocating a proactive approach to human evolution.[46] Immortalism, a moral ideology based upon the belief that radical life extension and technological immortality is possible and desirable, and advocating research and development to ensure its realization.[91] Libertarian transhumanism, a political ideology synthesizing libertarianism and transhumanism.[83] Postgenderism, a social philosophy which seeks the voluntary elimination of gender in the human species through the application of advanced biotechnology and assisted reproductive technologies.[92] Postpoliticism, a transhumanist political proposal that aims to create a "postdemocratic state" based on reason and free access of enhancement technologies to people.[93] Singularitarianism, a moral ideology based upon the belief that a technological singularity is possible, and advocating deliberate action to effect it and ensure its safety.[74] Technogaianism, an ecological ideology based upon the belief that emerging technologies can help restore Earth's environment and that developing safe, clean, alternative technology should therefore be an important goal of environmentalists.[89] Spirituality Although many transhumanists are atheists, agnostics, and/or secular humanists, some have religious or spiritual views.[47] Despite the prevailing secular attitude, some transhumanists pursue hopes traditionally espoused by religions, such as immortality,[91] while several controversial new religious movements from the late 20th century have explicitly embraced transhumanist goals of transforming the human condition by applying technology to the alteration of the mind and body, such as Raëlism.[94] However, most thinkers associated with the transhumanist movement focus on the practical goals of using technology to help achieve longer and healthier lives, while speculating that future understanding of neurotheology and the application of neurotechnology will enable humans to gain greater control of altered states of consciousness, which were commonly interpreted as spiritual experiences, and thus achieve more profound self-knowledge.[95] Transhumanist Buddhists have sought to explore areas of agreement between various types of Buddhism and Buddhist-derived meditation and mind-expanding neurotechnologies.[96] However, they have been criticised for appropriating mindfulness as a tool for transcending humanness.[97] Some transhumanists believe in the compatibility between the human mind and computer hardware, with the theoretical implication that human consciousness may someday be transferred to alternative media (a speculative technique commonly known as mind uploading).[98] One extreme formulation of this idea, which some transhumanists are interested in, is the proposal of the Omega Point by Christian cosmologist Frank Tipler. Drawing upon ideas in digitalism, Tipler has advanced the notion that the collapse of the Universe billions of years hence could create the conditions for the perpetuation of humanity in a simulated reality within a megacomputer and thus achieve a form of "posthuman godhood". Before Tipler, the term Omega Point was used by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a paleontologist and Jesuit theologian who saw an evolutionary telos in the development of an encompassing noosphere, a global consciousness.[99][100][101] Viewed from the perspective of some Christian thinkers, the idea of mind uploading is asserted to represent a denigration of the human body, characteristic of gnostic manichaean belief.[102] Transhumanism and its presumed intellectual progenitors have also been described as neo-gnostic by non-Christian and secular commentators.[103][104] The first dialogue between transhumanism and faith was a one-day conference held at the University of Toronto in 2004.[105] Religious critics alone faulted the philosophy of transhumanism as offering no eternal truths nor a relationship with the divine. They commented that a philosophy bereft of these beliefs leaves humanity adrift in a foggy sea of postmodern cynicism and anomie. Transhumanists responded that such criticisms reflect a failure to look at the actual content of the transhumanist philosophy, which, far from being cynical, is rooted in optimistic, idealistic attitudes that trace back to the Enlightenment.[106] Following this dialogue, William Sims Bainbridge, a sociologist of religion, conducted a pilot study, published in the Journal of Evolution and Technology, suggesting that religious attitudes were negatively correlated with acceptance of transhumanist ideas and indicating that individuals with highly religious worldviews tended to perceive transhumanism as being a direct, competitive (though ultimately futile) affront to their spiritual beliefs.[107] Since 2006, the Mormon Transhumanist Association sponsors conferences and lectures on the intersection of technology and religion.[108] The Christian Transhumanist Association[109] was established in 2014. Since 2009, the American Academy of Religion holds a "Transhumanism and Religion" consultation during its annual meeting, where scholars in the field of religious studies seek to identify and critically evaluate any implicit religious beliefs that might underlie key transhumanist claims and assumptions; consider how transhumanism challenges religious traditions to develop their own ideas of the human future, in particular the prospect of human transformation, whether by technological or other means; and provide critical and constructive assessments of an envisioned future that place greater confidence in nanotechnology, robotics and information technology to achieve virtual immortality and create a superior posthuman species.[110] The physicist and transhumanist thinker Giulio Prisco states that "cosmist religions based on science, might be our best protection from reckless pursuit of superintelligence and other risky technologies."[111] Prisco also recognizes the importance of spiritual ideas, such as the ones of Russian Orthodox philosopher Nikolai Fyodorovich Fyodorov, to the origins of the transhumanism movement. |

倫理 トランスヒューマニストは、未来学や倫理学の様々な分野を活用することで、生物学的限界を克服する可能性を理解し評価する学際的なアプローチに取り組んで いる[要出典]。自然システムの保全に道徳的価値を置く多くの哲学者や社会批評家、活動家とは異なり、トランスヒューマニストは、特に自然という概念その ものを、良く言えば漠然とした問題であり、悪く言えば進歩の障害であると考えている[82]。 [82]これに合わせて、ダン・アギンのような多くの著名なトランスヒューマニストの支持者は、政治的な右派と左派が共同でトランスヒューマニズムの批判 者を「バイオコンサーバティブ」または「バイオラッダイト」と呼んでいる。 反トランスヒューマニズムの信念は、トランスヒューマニズムは生活の様々な領域において、特に社会的な面において、人間の不当な強化を引き起こす可能性が あるというものである。これはステロイドの使用に例えることができ、スポーツでステロイドを使用する選手はそうでない選手よりも有利になる。さらに、 M.J.マクナミーとS.D.エドワーズによれば、社会の特定の特権的な部分によってもたらされる向上が、人類の種を2つの異なる別個の種に分裂させるの ではないかと危惧する者も多い[85]。一方はもう一方と交配することができず、身体的な健康状態や能力が低いために、他方よりも道徳的な地位が低いとみ なされるかもしれない[85]。 ニック・ボストロムは、トランスヒューマニズムは、人間以外の動物であれ、地球外生命体であれ、人工生命体であれ、全ての感覚を持つ存在の幸福を提唱して いると述べている[86]。この見解は、全ての感覚を持つ存在の苦しみを根絶するためにバイオテクノロジーの使用を提唱するデイヴィッド・ピアースによっ て繰り返し述べられている[87]。 潮流 トランスヒューマニスト思想の中にも様々な意見がある。トランスヒューマニズムを代表する思想家の多くは、常に修正と発展の途上にある見解を持っている[88]。ここでは、トランスヒューマニズムのいくつかの特徴的な潮流を特定し、アルファベット順に列挙する: 廃絶主義(Abolitionism):バイオテクノロジーを利用して、あらゆる生物の苦しみを根絶するという概念[87]。 民主的トランスヒューマニズム:自由民主主義、社会民主主義、急進的民主主義、トランスヒューマニズムを統合した政治思想[89]。 平等主義(Equalism):技術的特異点(シンギュラリティ)時代において、新たなテクノロジーが資源の均等な分配を通じて社会階層に終止符を打つという考えに基づく社会経済理論[90]。 エクストロピアニズム(Extropianism):人類の進化に対する積極的なアプローチを提唱する一連の原則によって特徴づけられるトランスヒューマニスト思想の初期の学派[46]。 不死主義(Immortalism):根本的な延命と技術的な不死は可能であり望ましいという信念に基づく道徳的イデオロギーであり、その実現を確実にするための研究開発を提唱している[91]。 リバタリアン・トランスヒューマニズム(Libertarian transhumanism):リバタリアニズムとトランスヒューマニズムを統合した政治思想[83]。 ポストジェンダリズム(Postgenderism):高度なバイオテクノロジーと生殖補助医療技術の応用を通じて、人類種におけるジェンダーの自発的な排除を目指す社会哲学[92]。 ポストポリティシズム(Postpoliticism):理性に基づいた「ポスト民主主義国家」の創設を目指すトランスヒューマニストによる政治的提案であり、人々が強化技術を自由に利用できるようにすることを目的としている[93]。 シンギュラリタリアニズム(Singularitarianism):技術的特異点が可能であるという信念に基づく道徳的イデオロギーであり、特異点を実現し、その安全を確保するための意図的な行動を提唱する[74]。 テクノガイアニズム(Technogaianism):新興技術が地球環境の回復に役立つという信念に基づく生態学的イデオロギーであり、それゆえ安全でクリーンな代替技術の開発は環境保護主義者の重要な目標であるべきである[89]。 スピリチュアリティ 多くのトランスヒューマニストは無神論者、無宗教者、世俗的ヒューマニストであるが、宗教的、霊的な見解を持っている者もいる[47]。世俗的な態度が一 般的であるにもかかわらず、トランスヒューマニストの中には不老不死など、伝統的に宗教が信奉してきた希望を追求する者もいる[91]。 [しかし、トランスヒューマニズム運動に関連するほとんどの思想家は、より長く健康的な生活を実現するためにテクノロジーを利用するという現実的な目標に 焦点を当てる一方で、神経神学の将来的な理解とニューロテクノロジーの応用によって、一般的にスピリチュアルな体験と解釈されていた意識の変容状態を人間 がよりコントロールできるようになり、その結果、より深い自己認識を達成できるようになるだろうと推測している。 [95]トランスヒューマニスト仏教徒は、様々なタイプの仏教と仏教由来の瞑想と心を拡張するニューロテクノロジーの間に一致する領域を探求しようとして いる[96]。しかし、彼らはマインドフルネスを人間性を超越するためのツールとして流用していると批判されている[97]。 トランスヒューマニストの中には、人間の意識はいつの日か代替メディアに転送されるかもしれないという理論的含意をもって、人間の心とコンピュータのハー ドウェアの間の互換性を信じている者もいる(一般にマインド・アップロードとして知られる投機的手法)[98]。一部のトランスヒューマニストが関心を寄 せているこの考えの一つの極端な定式化は、キリスト教宇宙学者のフランク・ティプラーによるオメガ・ポイントの提案である。ティプラーは、デジタリズムの 考え方を基に、数十億年後の宇宙の崩壊が、メガコンピューター内のシミュレートされた現実の中で人類を永続させるための条件を作り出し、その結果「ポスト ヒューマン神性」の形態を達成することができるという概念を提唱した。ティプラー以前には、オメガ・ポイントという用語は、古生物学者でありイエズス会の 神学者であったピエール・テイヤール・ド・シャルダンによって使われており、彼は包括的なヌースフィア、つまり地球規模の意識の発達に進化のテロスを見出 していた[99][100][101]。 一部のキリスト教思想家の視点から見ると、マインド・アップロードのアイデアは、グノーシス的なマニ教の信念に特徴的な、人間の身体の否定を表していると主張されている[102]。 トランスヒューマニズムと信仰との最初の対話は、2004年にトロント大学で開催された1日の会議であった[105]。宗教批評家たちは、トランスヒュー マニズムの哲学は永遠の真理も神との関係も提供しないと非難した。これらの信念を失った哲学は、人類をポストモダンのシニシズムとアノミーの霧の海に漂わ せる、と彼らはコメントした。トランスヒューマニストたちは、このような批判はトランスヒューマニズム哲学の実際の内容を見ていないことの反映であり、シ ニカルであるどころか、啓蒙主義にまで遡る楽観的で理想主義的な態度に根ざしていると反論した。 [この対話を受けて、宗教社会学者であるウィリアム・シムズ・ベインブリッジは、『Journal of Evolution and Technology』誌に掲載されたパイロット研究を実施し、宗教的態度がトランスヒューマニズムの思想の受容と負の相関関係があることを示唆し、宗教 的世界観の強い人々は、トランスヒューマニズムが彼らの精神的信念に対する直接的で競争的な(最終的には無益ではあるが)侮辱であると認識する傾向がある ことを示している[107]。 2006年以降、モルモン・トランスヒューマニスト協会はテクノロジーと宗教の交差点に関する会議や講演会を主催している[108]。2014年にはクリスチャン・トランスヒューマニスト協会[109]が設立された。 2009年以降、米国宗教学会は年次総会において「トランスヒューマニズムと宗教」コンサルテーションを開催しており、宗教学の分野の学者たちは、トラン スヒューマニズムの主要な主張や仮定の根底にある可能性のある暗黙の宗教的信念を特定し、批判的に評価することを求めている; トランスヒューマニズムが、人間の未来について宗教的伝統がどのように独自の考えを発展させるか、特に技術的あるいはその他の手段による人間の変容の見通 しについてどのように挑戦しているかを検討し、仮想的な不死を達成し、優れたポストヒューマン種を創造するためにナノテクノロジー、ロボット工学、情報技 術により大きな信頼を置く、想定される未来について批判的かつ建設的な評価を提供する。 [110] 物理学者でトランスヒューマニストの思想家であるジュリオ・プリスコは、「科学に基づいた宇宙主義的な宗教は、超知能やその他の危険な技術の無謀な追求か ら私たちを守ってくれるかもしれない」と述べている[111]。プリスコはまた、ロシア正教の哲学者であるニコライ・フョードロヴィチ・フョードロフのよ うな精神的な思想がトランスヒューマニズム運動の起源において重要であることも認識している。 |

| Practice While some transhumanists[who?] take an abstract and theoretical approach to the perceived benefits of emerging technologies, others have offered specific proposals for modifications to the human body, including heritable ones. Transhumanists are often concerned with methods of enhancing the human nervous system. Though some, such as Kevin Warwick, propose modification of the peripheral nervous system, the brain is considered the common denominator of personhood and is thus a primary focus of transhumanist ambitions.[112] In fact, Warwick has gone a lot further than merely making a proposal. In 2002 he had a 100 electrode array surgically implanted into the median nerves of his left arm to link his nervous system directly with a computer and thus to also connect with the internet. As a consequence, he carried out a series of experiments. He was able to directly control a robot hand using his neural signals and to feel the force applied by the hand through feedback from the fingertips. He also experienced a form of ultrasonic sensory input and conducted the first purely electronic communication between his own nervous system and that of his wife who also had electrodes implanted.[113]  Neil Harbisson's antenna implant allows him to extend his senses beyond human perception. As proponents of self-improvement and body modification, transhumanists tend to use existing technologies and techniques that supposedly improve cognitive and physical performance, while engaging in routines and lifestyles designed to improve health and longevity.[114] Depending on their age, some[who?] transhumanists express concern that they will not live to reap the benefits of future technologies. However, many have a great interest in life extension strategies and in funding research in cryonics to make the latter a viable option of last resort, rather than remaining an unproven method.[115] Regional and global transhumanist networks and communities with a range of objectives exist to provide support and forums for discussion and collaborative projects.[citation needed] While most transhumanist theory focuses on future technologies and the changes they may bring, many today are already involved in the practice on a very basic level. It is not uncommon for many to receive cosmetic changes to their physical form via cosmetic surgery, even if it is not required for health reasons. Human growth hormones attempt to alter the natural development of shorter children or those who have been born with a physical deficiency. Doctors prescribe medicines such as Ritalin and Adderall to improve cognitive focus, and many people take "lifestyle" drugs such as Viagra, Propecia, and Botox to restore aspects of youthfulness that have been lost in maturity.[116] Other transhumanists, such as cyborg artist Neil Harbisson, use technologies and techniques to improve their senses and perception of reality. Harbisson's antenna, which is permanently implanted in his skull, allows him to sense colours beyond human perception such as infrareds and ultraviolets.[117] Technologies of interest Main article: Human enhancement technologies Transhumanists support the emergence and convergence of technologies including nanotechnology, biotechnology, information technology and cognitive science (NBIC), as well as hypothetical future technologies like simulated reality, artificial intelligence, superintelligence, 3D bioprinting, mind uploading, chemical brain preservation and cryonics. They believe that humans can and should use these technologies to become more than human.[118] Therefore, they support the recognition and/or protection of cognitive liberty, morphological freedom and procreative liberty as civil liberties, so as to guarantee individuals the choice of using human enhancement technologies on themselves and their children.[119] Some speculate that human enhancement techniques and other emerging technologies may facilitate more radical human enhancement no later than at the midpoint of the 21st century. Kurzweil's book The Singularity is Near and Michio Kaku's book Physics of the Future outline various human enhancement technologies and give insight on how these technologies may impact the human race.[74][120] Some reports on the converging technologies and NBIC concepts have criticised their transhumanist orientation and alleged science fictional character.[121] At the same time, research on brain and body alteration technologies has been accelerated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Defense, which is interested in the battlefield advantages they would provide to the supersoldiers of the United States and its allies.[122] There has already been a brain research program to "extend the ability to manage information", while military scientists are now looking at stretching the human capacity for combat to a maximum 168 hours without sleep.[123] Neuroscientist Anders Sandberg has been practicing on the method of scanning ultra-thin sections of the brain. This method is being used to help better understand the architecture of the brain. As of now, this method is currently being used on mice. This is the first step towards hypothetically uploading contents of the human brain, including memories and emotions, onto a computer.[124][125] |

実践 トランスヒューマニスト[誰?]のなかには、新たなテクノロジーがもたらす恩恵について抽象的かつ理論的なアプローチをとる者もいるが、遺伝的なものも含 め、人体の改造について具体的な提案をしている者もいる。トランスヒューマニストはしばしば、人間の神経系を強化する方法に関心を寄せている。ケヴィン・ ワーウィックのように、末梢神経系の改造を提案する者もいるが、脳は人間性の共通項と考えられており、それゆえトランスヒューマニストの野望の主要な焦点 となっている[112]。 実際、ワーウィックは単に提案を行うだけでなく、さらに多くのことを行っている。2002年、彼は100個の電極アレイを左腕の正中神経に外科的に埋め込 み、神経系をコンピュータと直接リンクさせることで、インターネットにも接続できるようにした。その結果、彼は一連の実験を行った。彼は神経信号を使って ロボットハンドを直接操作し、指先からのフィードバックによってハンドが加える力を感じることができた。彼はまた、一種の超音波感覚入力を経験し、自分自 身の神経系と、同じく電極を埋め込んだ妻の神経系との間で、初めて純粋に電子的な通信を行った[113]。  ニール・ハービッソンのアンテナ・インプラントにより、彼は人間の知覚を超えて感覚を拡張することができる。 自己改善と身体改造の推進者として、トランスヒューマニストは、認知的・身体的パフォーマンスを向上させるとされる既存の技術やテクニックを利用する傾向 があり、一方で健康と長寿を向上させるように設計された日常生活やライフスタイルに従事する[114]。しかし、その多くは延命戦略や、人体冷凍保存を実 証されていない方法のままで終わらせるのではなく、最後の手段として実行可能な選択肢とするための研究に資金を提供することに大きな関心を持っている [115]。 トランスヒューマニストの理論のほとんどは、未来のテクノロジーとそれがもたらすかもしれない変化に焦点を当てているが、今日の多くの人々は、すでに非常 に基本的なレベルで実践に携わっている。健康上の理由で必要でなくても、美容整形手術によって肉体的な変化を受けることは珍しくない。ヒト成長ホルモン は、背の低い子供や生まれつき身体的欠陥のある人の自然な発育を変えようとするものである。医師は認知集中力を向上させるためにリタリンやアデロールなど の医薬品を処方し、多くの人々は成熟して失われた若々しさを取り戻すためにバイアグラ、プロペシア、ボトックスなどの「ライフスタイル」薬を服用する [116]。 サイボーグ・アーティストのニール・ハービッソンのような他のトランスヒューマニストは、自分の感覚や現実の知覚を向上させるために技術やテクニックを 使っている。ハービッソンは頭蓋骨に永久的に埋め込まれているアンテナによって、赤外線や紫外線といった人間の知覚を超えた色を感じることができる [117]。 関心のある技術 主な記事 人間強化技術 トランスヒューマニストは、ナノテクノロジー、バイオテクノロジー、情報技術、認知科学(NBIC)、さらにはシミュレーテッド・リアリティ、人工知能、 超知能、3Dバイオプリンティング、マインド・アップロード、化学的脳保存、クライオニクスなどの仮想的な未来技術の出現と融合を支持する。そのため、認 知的自由、形態学的自由、子作りの自由を市民的自由として認め、あるいは保護することで、個人が自分自身や自分の子供に人間強化技術を使用する選択肢を保 証することを支持している[119]。人間強化技術やその他の新たな技術によって、遅くとも21世紀の半ばまでには、より根本的な人間強化が促進されると 推測する者もいる。カーツワイルの著書『The Singularity is Near』やミチオ・カクの著書『Physics of the Future』では、様々な人間強化技術について概説しており、これらの技術が人類にどのような影響を与える可能性があるかについての洞察を与えている [74][120]。 収斂技術やNBICのコンセプトに関するいくつかの報告書は、そのトランスヒューマニズム的志向やSF的性格を批判している[121]。国防総省は、それらが米国とその同盟国のスーパーソルジャーにもたらすであろう戦場での優位性に関心を抱いている[122]。 神経科学者のアンダース・サンドバーグは、脳の超薄切片をスキャンする方法を実践している。この方法は脳の構造をより深く理解するために使われている。現 在のところ、この方法はマウスに使われている。これは、記憶や感情を含む人間の脳の内容をコンピューターにアップロードする仮説への第一歩である [124][125]。 |

| Debate The very notion and prospect of human enhancement and related issues arouse public controversy.[126] Criticisms of transhumanism and its proposals take two main forms: those objecting to the likelihood of transhumanist goals being achieved (practical criticisms) and those objecting to the moral principles or worldview sustaining transhumanist proposals or underlying transhumanism itself (ethical criticisms). Critics and opponents often see transhumanists' goals as posing threats to human values. The human enhancement debate is, for some, framed by the opposition between strong bioconservatism and transhumanism. The former opposes any form of human enhancement, whereas the latter advocates for all possible human enhancements [127] However, many philosophers engaged in the continuing debate hold a more nuanced view in favour of some enhancements while rejecting the transhumanist carte blanche approach.[128] Some of the most widely known critiques of the transhumanist program are novels and fictional films. These works of art, despite presenting imagined worlds rather than philosophical analyses, are used as touchstones for some of the more formal arguments.[7] Various arguments have been made to the effect that a society that adopts human enhancement technologies may come to resemble the dystopia depicted in the 1932 novel Brave New World by Aldous Huxley.[129] On another front, some authors consider that humanity is already transhuman, because medical advances in recent centuries have significantly altered our species. However, it is not in a conscious and therefore transhumanistic way.[130] From such perspective, transhumanism is perpetually aspirational: as new technologies become mainstream, the adoption of new yet-unadopted technologies becomes a new shifting goal. Feasibility In a 1992 book, sociologist Max Dublin pointed to many past failed predictions of technological progress and argued that modern futurist predictions would prove similarly inaccurate. He also objected to what he saw as scientism, fanaticism and nihilism by a few in advancing transhumanist causes. Dublin also said that historical parallels existed between Millenarian religions and Communist doctrines.[131] Although generally sympathetic to transhumanism, public health professor Gregory Stock is skeptical of the technical feasibility and mass appeal of the cyborgization of humanity predicted by Raymond Kurzweil, Hans Moravec and Kevin Warwick. He said that, throughout the 21st century, many humans would find themselves deeply integrated into systems of machines, but would remain biological. Primary changes to their own form and character would arise not from cyberware, but from the direct manipulation of their genetics, metabolism and biochemistry.[132] In her 1992 book Science as Salvation, philosopher Mary Midgley traces the notion of achieving immortality by transcendence of the material human body (echoed in the transhumanist tenet of mind uploading) to a group of male scientific thinkers of the early 20th century, including J. B. S. Haldane and members of his circle. She characterizes these ideas as "quasi-scientific dreams and prophesies" involving visions of escape from the body coupled with "self-indulgent, uncontrolled power-fantasies". Her argument focuses on what she perceives as the pseudoscientific speculations and irrational, fear-of-death-driven fantasies of these thinkers, their disregard for laymen and the remoteness of their eschatological visions.[133] Another critique is aimed mainly at "algeny" (a portmanteau of alchemy and genetics), which Jeremy Rifkin defined as "the upgrading of existing organisms and the design of wholly new ones with the intent of 'perfecting' their performance".[134] It emphasizes the issue of biocomplexity and the unpredictability of attempts to guide the development of products of biological evolution. This argument, elaborated in particular by the biologist Stuart Newman, is based on the recognition that cloning and germline genetic engineering of animals are error-prone and inherently disruptive of embryonic development. Accordingly, so it is argued, it would create unacceptable risks to use such methods on human embryos. Performing experiments, particularly ones with permanent biological consequences, on developing humans would thus be in violation of accepted principles governing research on human subjects (see the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki). Moreover, because improvements in experimental outcomes in one species are not automatically transferable to a new species without further experimentation, it is claimed that there is no ethical route to genetic manipulation of humans at early developmental stages.[135] As a practical matter, however, international protocols on human subject research may not present a legal obstacle to attempts by transhumanists and others to improve their offspring by germinal choice technology. According to legal scholar Kirsten Rabe Smolensky, existing laws would protect parents who choose to enhance their child's genome from future liability arising from adverse outcomes of the procedure.[136] Transhumanists and other supporters of human genetic engineering do not dismiss practical concerns out of hand, insofar as there is a high degree of uncertainty about the timelines and likely outcomes of genetic modification experiments in humans. However, bioethicist James Hughes suggests that one possible ethical route to the genetic manipulation of humans at early developmental stages is the building of computer models of the human genome, the proteins it specifies and the tissue engineering he argues that it also codes for. With the exponential progress in bioinformatics, Hughes believes that a virtual model of genetic expression in the human body will not be far behind and that it will soon be possible to accelerate approval of genetic modifications by simulating their effects on virtual humans.[7] Public health professor Gregory Stock points to artificial chromosomes as an alleged safer alternative to existing genetic engineering techniques.[132] Thinkers[who?] who defend the likelihood of accelerating change point to a past pattern of exponential increases in humanity's technological capacities. Kurzweil developed this position in his 2005 book The Singularity Is Near. Intrinsic immorality It has been argued that, in transhumanist thought, humans attempt to substitute themselves for God. The 2002 Vatican statement Communion and Stewardship: Human Persons Created in the Image of God,[137] stated that "changing the genetic identity of man as a human person through the production of an infrahuman being is radically immoral", implying, that "man has full right of disposal over his own biological nature". The statement also argues that creation of a superhuman or spiritually superior being is "unthinkable", since true improvement can come only through religious experience and "realizing more fully the image of God". Christian theologians and lay activists of several churches and denominations have expressed similar objections to transhumanism and claimed that Christians attain in the afterlife what radical transhumanism promises, such as indefinite life extension or the abolition of suffering. In this view, transhumanism is just another representative of the long line of utopian movements which seek to create "heaven on earth".[138][139] On the other hand, religious thinkers allied with transhumanist goals such as the theologians Ronald Cole-Turner and Ted Peters hold that the doctrine of "co-creation" provides an obligation to use genetic engineering to improve human biology.[140][141] Other critics target what they claim to be an instrumental conception of the human body in the writings of Marvin Minsky, Hans Moravec and some other transhumanists.[69] Reflecting a strain of feminist criticism of the transhumanist program, philosopher Susan Bordo points to "contemporary obsessions with slenderness, youth and physical perfection", which she sees as affecting both men and women, but in distinct ways, as "the logical (if extreme) manifestations of anxieties and fantasies fostered by our culture."[142] Some critics question other social implications of the movement's focus on body modification. Political scientist Klaus-Gerd Giesen, in particular, has asserted that transhumanism's concentration on altering the human body represents the logical yet tragic consequence of atomized individualism and body commodification within a consumer culture.[103] Nick Bostrom responds that the desire to regain youth, specifically, and transcend the natural limitations of the human body, in general, is pan-cultural and pan-historical, and is therefore not uniquely tied to the culture of the 20th century. He argues that the transhumanist program is an attempt to channel that desire into a scientific project on par with the Human Genome Project and achieve humanity's oldest hope, rather than a puerile fantasy or social trend.[2] Loss of human identity  In the U.S., the Amish are a religious group most known for their avoidance of certain modern technologies. Transhumanists draw a parallel by arguing that in the near-future there will probably be "humanish", people who choose to "stay human" by not adopting human enhancement technologies. They believe their choice must be respected and protected.[143] In his 2003 book Enough: Staying Human in an Engineered Age, environmental ethicist Bill McKibben argued at length against many of the technologies that are postulated or supported by transhumanists, including germinal choice technology, nanomedicine and life extension strategies. He claims that it would be morally wrong for humans to tamper with fundamental aspects of themselves (or their children) in an attempt to overcome universal human limitations, such as vulnerability to aging, maximum life span and biological constraints on physical and cognitive ability. Attempts to "improve" themselves through such manipulation would remove limitations that provide a necessary context for the experience of meaningful human choice. He claims that human lives would no longer seem meaningful in a world where such limitations could be overcome technologically. Even the goal of using germinal choice technology for clearly therapeutic purposes should be relinquished, since it would inevitably produce temptations to tamper with such things as cognitive capacities. He argues that it is possible for societies to benefit from renouncing particular technologies, using as examples Ming China, Tokugawa Japan and the contemporary Amish.[144] Biopolitical activist Jeremy Rifkin and biologist Stuart Newman accept that biotechnology has the power to make profound changes in organismal identity. They argue against the genetic engineering of human beings because they fear the blurring of the boundary between human and artifact.[135][145] Philosopher Keekok Lee sees such developments as part of an accelerating trend in modernization in which technology has been used to transform the "natural" into the "artefactual".[146] In the extreme, this could lead to the manufacturing and enslavement of "monsters" such as human clones, human-animal chimeras, or bioroids, but even lesser dislocations of humans and non-humans from social and ecological systems are seen as problematic. The film Blade Runner (1982) and the novels The Boys From Brazil (1976) and The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896) depict elements of such scenarios, but Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is most often alluded to by critics who suggest that biotechnologies could create objectified and socially unmoored people as well as subhumans. Such critics propose that strict measures be implemented to prevent what they portray as dehumanizing possibilities from ever happening, usually in the form of an international ban on human genetic engineering.[147] Science journalist Ronald Bailey claims that McKibben's historical examples are flawed and support different conclusions when studied more closely.[148] For example, few groups are more cautious than the Amish about embracing new technologies, but, though they shun television and use horses and buggies, some are welcoming the possibilities of gene therapy since inbreeding has afflicted them with a number of rare genetic diseases.[132] Bailey and other supporters of technological alteration of human biology also reject the claim that life would be experienced as meaningless if some human limitations are overcome with enhancement technologies as extremely subjective. Writing in Reason magazine, Bailey has accused opponents of research involving the modification of animals as indulging in alarmism when they speculate about the creation of subhuman creatures with human-like intelligence and brains resembling those of Homo sapiens. Bailey insists that the aim of conducting research on animals is simply to produce human health care benefits.[149] A different response comes from transhumanist personhood theorists who object to what they characterize as the anthropomorphobia fueling some criticisms of this research, which science fiction writer Isaac Asimov termed the "Frankenstein complex". For example, Woody Evans argues that, provided they are self-aware, human clones, human-animal chimeras and uplifted animals would all be unique persons deserving of respect, dignity, rights, responsibilities, and citizenship.[150] They conclude that the coming ethical issue is not the creation of so-called monsters, but what they characterize as the "yuck factor" and "human-racism", that would judge and treat these creations as monstrous.[47][151] In book 3 of his Corrupting the Image series, Dr. Douglas Hamp goes so far as to suggest that the Beast of John's Apocalypse is himself a hybrid who will induce humanity to take "the mark of the Beast," in the hopes of obtaining perfection and immortality.[152] At least one public interest organization, the U.S.-based Center for Genetics and Society, was formed, in 2001, with the specific goal of opposing transhumanist agendas that involve transgenerational modification of human biology, such as full-term human cloning and germinal choice technology. The Institute on Biotechnology and the Human Future of the Chicago-Kent College of Law critically scrutinizes proposed applications of genetic and nanotechnologies to human biology in an academic setting. Socioeconomic effects Some critics of libertarian transhumanism have focused on the likely socioeconomic consequences in societies in which divisions between rich and poor are on the rise. Bill McKibben, for example, suggests that emerging human enhancement technologies would be disproportionately available to those with greater financial resources, thereby exacerbating the gap between rich and poor and creating a "genetic divide".[144] Even Lee M. Silver, the biologist and science writer who coined the term "reprogenetics" and supports its applications, has expressed concern that these methods could create a two-tiered society of genetically engineered "haves" and "have nots" if social democratic reforms lag behind implementation of enhancement technologies.[153] The 1997 film Gattaca depicts a dystopian society in which one's social class depends entirely on genetic potential and is often cited by critics in support of these views.[7] These criticisms are also voiced by non-libertarian transhumanist advocates, especially self-described democratic transhumanists, who believe that the majority of current or future social and environmental issues (such as unemployment and resource depletion) need to be addressed by a combination of political and technological solutions (like a guaranteed minimum income and alternative technology). Therefore, on the specific issue of an emerging genetic divide due to unequal access to human enhancement technologies, bioethicist James Hughes, in his 2004 book Citizen Cyborg: Why Democratic Societies Must Respond to the Redesigned Human of the Future, argues that progressives or, more precisely, techno-progressives must articulate and implement public policies (i.e., a universal health care voucher system that covers human enhancement technologies) to attenuate this problem as much as possible, rather than trying to ban human enhancement technologies. The latter, he argues, might actually worsen the problem by making these technologies unsafe or available only to the wealthy on the local black market or in countries where such a ban is not enforced.[7] Sometimes, as in the writings of Leon Kass, the fear is that various institutions and practices judged as fundamental to civilized society would be damaged or destroyed.[154] In his 2002 book Our Posthuman Future and in a 2004 Foreign Policy magazine article, political economist and philosopher Francis Fukuyama designates transhumanism as the world's most dangerous idea because he believes that it may undermine the egalitarian ideals of democracy (in general) and liberal democracy (in particular) through a fundamental alteration of "human nature".[61] Social philosopher Jürgen Habermas makes a similar argument in his 2003 book The Future of Human Nature, in which he asserts that moral autonomy depends on not being subject to another's unilaterally imposed specifications. Habermas thus suggests that the human "species ethic" would be undermined by embryo-stage genetic alteration.[155] Critics such as Kass, Fukuyama and a variety of authors hold that attempts to significantly alter human biology are not only inherently immoral, but also threaten the social order. Alternatively, they argue that implementation of such technologies would likely lead to the "naturalizing" of social hierarchies or place new means of control in the hands of totalitarian regimes. AI pioneer Joseph Weizenbaum criticizes what he sees as misanthropic tendencies in the language and ideas of some of his colleagues, in particular Marvin Minsky and Hans Moravec, which, by devaluing the human organism per se, promotes a discourse that enables divisive and undemocratic social policies.[156] In a 2004 article in the libertarian monthly Reason, science journalist Ronald Bailey contested the assertions of Fukuyama by arguing that political equality has never rested on the facts of human biology. He asserts that liberalism was founded not on the proposition of effective equality of human beings, or de facto equality, but on the assertion of an equality in political rights and before the law, or de jure equality. Bailey asserts that the products of genetic engineering may well ameliorate rather than exacerbate human inequality, giving to the many what were once the privileges of the few. Moreover, he argues, "the crowning achievement of the Enlightenment is the principle of tolerance". In fact, he says, political liberalism is already the solution to the issue of human and posthuman rights since in liberal societies the law is meant to apply equally to all, no matter how rich or poor, powerful or powerless, educated or ignorant, enhanced or unenhanced.[157] Other thinkers who are sympathetic to transhumanist ideas, such as philosopher Russell Blackford, have also objected to the appeal to tradition and what they see as alarmism involved in Brave New World-type arguments.[158] Cultural aesthetics In addition to the socio-economic risks and implications of transhumanism, there are indeed implications and possible consequences in regard to cultural aesthetics. Currently, there are a number of ways in which people choose to represent themselves in society. The way in which a person dresses, hair styles, and body alteration all serve to identify the way a person presents themselves and is perceived by society. According to Foucault,[159] society already governs and controls bodies by making them feel watched. This "surveillance" of society dictates how the majority of individuals choose to express themselves aesthetically. One of the risks outlined in a 2004 article by Jerold Abrams is the elimination of differences in favor of universality. This, he argues, will eliminate the ability of individuals to subvert the possibly oppressive, dominant structure of society by way of uniquely expressing themselves externally. Such control over a population would have dangerous implications of tyranny. Yet another consequence of enhancing the human form not only cognitively, but physically, will be the reinforcement of "desirable" traits which are perpetuated by the dominant social structure.[159] Specter of coercive eugenicism Some critics of transhumanism[who?] see the old eugenics, social Darwinist, and master race ideologies and programs of the past as warnings of what the promotion of eugenic enhancement technologies might unintentionally encourage. Some fear future "eugenics wars" as the worst-case scenario: the return of coercive state-sponsored genetic discrimination and human rights violations such as compulsory sterilization of persons with genetic defects, the killing of the institutionalized and, specifically, segregation and genocide of races perceived as inferior.[160][need quotation to verify] Health law professor George Annas and technology law professor Lori Andrews are prominent advocates of the position that the use of these technologies could lead to such human-posthuman caste warfare.[147][161] The major transhumanist organizations strongly condemn the coercion involved in such policies and reject the racist and classist assumptions on which they were based, along with the pseudoscientific notions that eugenic improvements could be accomplished in a practically meaningful time frame through selective human breeding.[162] Instead, most transhumanist thinkers advocate a "new eugenics", a form of egalitarian liberal eugenics.[163] In their 2000 book From Chance to Choice: Genetics and Justice, non-transhumanist bioethicists Allen Buchanan, Dan Brock, Norman Daniels and Daniel Wikler have argued that liberal societies have an obligation to encourage as wide an adoption of eugenic enhancement technologies as possible (so long as such policies do not infringe on individuals' reproductive rights or exert undue pressures on prospective parents to use these technologies) to maximize public health and minimize the inequalities that may result from both natural genetic endowments and unequal access to genetic enhancements.[164] Most transhumanists holding similar views nonetheless distance themselves from the term "eugenics" (preferring "germinal choice" or "reprogenetics")[153] to avoid having their position confused with the discredited theories and practices of early-20th-century eugenic movements.[citation needed] Existential risks See also: Existential risk from advanced artificial intelligence In his 2003 book Our Final Hour, British Astronomer Royal Martin Rees argues that advanced science and technology bring as much risk of disaster as opportunity for progress. However, Rees does not advocate a halt to scientific activity. Instead, he calls for tighter security and perhaps an end to traditional scientific openness.[165] Advocates of the precautionary principle, such as many in the environmental movement, also favor slow, careful progress or a halt in potentially dangerous areas. Some precautionists believe that artificial intelligence and robotics present possibilities of alternative forms of cognition that may threaten human life.[166] Transhumanists do not necessarily rule out specific restrictions on emerging technologies so as to lessen the prospect of existential risk. Generally, however, they counter that proposals based on the precautionary principle are often unrealistic and sometimes even counter-productive as opposed to the technogaian current of transhumanism, which they claim is both realistic and productive. In his television series Connections, science historian James Burke dissects several views on technological change, including precautionism and the restriction of open inquiry. Burke questions the practicality of some of these views, but concludes that maintaining the status quo of inquiry and development poses hazards of its own, such as a disorienting rate of change and the depletion of our planet's resources. The common transhumanist position is a pragmatic one where society takes deliberate action to ensure the early arrival of the benefits of safe, clean, alternative technology, rather than fostering what it considers to be anti-scientific views and technophobia. Nick Bostrom argues that even barring the occurrence of a singular global catastrophic event, basic Malthusian and evolutionary forces facilitated by technological progress threaten to eliminate the positive aspects of human society.[167] One transhumanist solution proposed by Bostrom to counter existential risks is control of differential technological development, a series of attempts to influence the sequence in which technologies are developed. In this approach, planners would strive to retard the development of possibly harmful technologies and their applications, while accelerating the development of likely beneficial technologies, especially those that offer protection against the harmful effects of others.[75] Antinatalism Although most people zoom in on the technological and scientific barriers on the road to transhumanist enhancement, Robbert Zandbergen argues that contemporary transhumanists' failure to critically engage the movement of antinatalism is a far larger obstacle to a better future. Antinatalism is the movement to restrict or terminate human reproduction as the final means to solve our existential problems. If transhumanists fail to take this threat to human perseverance seriously, they run the risk of collapsing the entire edifice of radical enhancement.[168] |