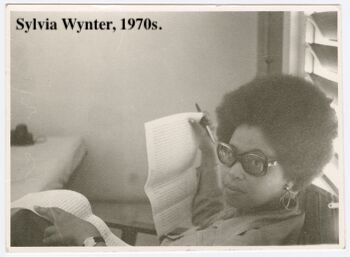

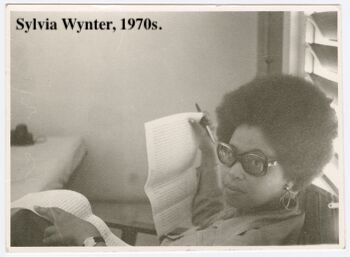

シルビア・ウィンター

Sylvia Wynter, b.1928

☆シ

ルビア・ウィンター(本名:O.J.、1928年5月11日、キューバ・オルギン生まれ)は、ジャマイカの小説家、劇作家、批評家、哲学者、随筆家であ

る。彼女の作品は、自然科学、人文科学、芸術、反植民地主義闘争からの洞察を組み合わせ、彼女が「人間の過剰表現」と呼ぶものを揺るがすことを目的として

いる。黒人研究、経済学、歴史学、神経科学、精神分析学、文学分析、映画分析、哲学などが、彼女の学術研究で参照される分野の一部である。

| Sylvia Wynter,

O.J. (Holguín, Cuba,[1] 11 May 1928)[2] is a Jamaican novelist,[1]

dramatist,[2] critic, philosopher, and essayist.[3] Her work combines

insights from the natural sciences, the humanities, art, and

anti-colonial struggles in order to unsettle what she refers to as the "overrepresentation of Man". Black

studies, economics, history, neuroscience, psychoanalysis, literary

analysis, film analysis, and philosophy are some of the fields she

draws on in her scholarly work. |

シルビア・ウィンター(本名:O.J.、1928年5月11日、キュー

バ・オルギン生まれ)は、ジャマイカの小説家、劇作家、批評家、哲学者、随筆家である。彼女の作品は、自然科学、人文科学、芸術、反植民地主義闘争からの

洞察を組み合わせ、彼女が「人間の過剰表現」と呼ぶものを揺るがすことを目的としている。黒人研究、経済学、歴史学、神経科学、精神分析学、文学分析、映

画分析、哲学などが、彼女の学術研究で参照される分野の一部である。 |

| Biography Sylvia Wynter was born in Cuba to Jamaican parents,[1] actress Lola Maude (Reid) Wynter and tailor Percival Wynter. At the age of two, she and her brother Hector and their parents returned to their home country of Jamaica. She attended the Ebenezer primary school in Kingston and, at the age of 9, won a scholarship to attend the St Andrew High School for Girls, also in Kingston.[3][4] In 1946, she was competed for and won the Jamaica Centenary Scholarship for Girls, which took her to King's College London to read for her B.A. in modern languages (Spanish) from 1947 to 1951. She was awarded the M.A. in December 1953 for her thesis, a critical edition of a Spanish comedia, A lo que obliga el honor. In 1956, Wynter met the Guyanese actor and novelist Jan Carew, who became her second husband. In 1958, she completed Under the Sun, a full-length stage play, which was bought by the Royal Court Theatre in London.[5] In 1962, Wynter published her only novel, The Hills of Hebron, based on Under the Sun. After separating from Carew in the early 1960s, Wynter returned to academia, and in 1963, was appointed assistant lecturer in Hispanic literature at the Mona campus of the University of the West Indies. She remained there until 1974. During this time the Jamaican government commissioned her to write the play 1865–A Ballad for a Rebellion, about the Morant Bay rebellion, and a biography of Sir Alexander Bustamante, the first prime minister of independent Jamaica. In 1974, Wynter was invited by the Department of Literature at the University of California at San Diego to be a professor of Comparative and Spanish Literature and to lead a new program in Third World literature. She left UCSD in 1977 to become chairperson of African and Afro-American Studies, and professor of Spanish in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at Stanford University, where she worked until 1997. She is now Professor Emerita at Stanford University.[4] In the mid to late 1960s, Wynter began writing critical essays addressing her interests in Caribbean, Latin American, and Spanish history and literatures. In 1968 and 1969 she published a two-part essay proposing to transform scholars' very approach to literary criticism, "We Must Learn to Sit Down Together and Talk About a Little Culture: Reflections on West Indian Writing and Criticism". Wynter has since written numerous essays in which she seeks to rethink the fullness of human ontologies, which, she argues, have been curtailed by what she describes as an over-representation of (western bourgeois) Man as if it/he were the only available mode of complete humanness. She suggests how multiple knowledge sources and texts might frame our worldview differently. In 2010, Sylvia Wynter was awarded the Order of Jamaica (OJ) for services in the fields of education, history, and culture.[6][7] |

略歴 シルビア・ウィンターは、ジャマイカ人の両親、女優のローラ・モード(リード)・ウィンターと仕立て屋のパーシバル・ウィンターのもと、キューバで生まれ た。2歳のとき、兄のヘクターと両親とともに母国ジャマイカに戻った。キングストンのエベニーザー小学校に通い、9歳のときに、同じくキングストンにある セント・アンドルー女子高校への奨学金を獲得した。1946年には、ジャマイカ女子百周年記念奨学金を獲得し、1947年から1951年までキングス・カ レッジ・ロンドンで現代言語(スペイン語)の学士号を取得した。1953年12月には、スペインの喜劇『A lo que obliga el honor』の批評版を論文として提出し、修士号を取得した。 1956年、ウィンターはガイアナ出身の俳優兼小説家ジャン・キャルーと出会い、彼を第二の夫とした。1958年には長編舞台劇『太陽の下で』を完成さ せ、ロンドンのロイヤル・コート劇場に買い取られた。[5] 1962年、ウィンターは『太陽の下で』を基にした唯一の小説『ヘブロンの丘』を出版した。 1960年代初頭にケアウと別れた後、ウィンターは学界に戻り、1963年に西インド諸島大学モナキャンパスでヒスパニック文学の助教授に任命された。彼 女は1974年までその職に留まった。この間、ジャマイカ政府から、モラント湾の反乱を描いた戯曲『1865年 - 反乱のバラード』と、独立ジャマイカ初代首相アレクサンダー・ブスタマンテ卿の伝記の執筆を依頼された。 1974年、ウィンターはカリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校の文学部から、比較文学およびスペイン文学の教授として、また第三世界文学の新しいプログラム 責任者として招かれた。1977年にUCSDを離れ、スタンフォード大学のアフリカおよびアフリカ系アメリカ人研究学科の学科長、ならびにスペイン語・ポ ルトガル語学科のスペイン語教授に就任し、1997年まで勤務した。現在はスタンフォード大学の名誉教授である。[4] 1960年代中盤から後半にかけて、ウィンターはカリブ海地域、ラテンアメリカ、スペインの歴史と文学に関する自身の関心を取り上げた批評的エッセイの執 筆を始めた。1968年と1969年には、文学批評への学者のアプローチそのものを変革することを提案する二部構成のエッセイ『共に座り、少しの文化につ いて語り合うことを学ばねばならない:西インド諸島の文学と批評に関する考察』を発表した。ウィンターはその後も数多くの論文を執筆し、人間存在論の豊か さを再考しようとしている。彼女は、西洋ブルジョワ的な「人間」が過剰に代表され、あたかもそれが完全な人間性の唯一の形態であるかのように扱われること で、人間存在論が制限されてきたと主張する。そして、多様な知識源やテキストが、いかに私たちの世界観を異なる形で構築しうるかを示唆している。 2010年、シルビア・ウィンターは教育・歴史・文化分野への貢献が認められ、ジャマイカ勲章(OJ)を授与された。[6][7] |

| Critical work Sylvia Wynter's scholarly work is highly poetic, expository, and complex. Her long career has seen her work on a range of marxist and decolonial issues with a analytic framework drawn from her wide-ranging, multi-disciplinary reading. She draws from anthropology, sociology, philosophy, cognitive science, and history. Starting with a basis in literary criticism, Wynter moved through a marxist analysis of the Iberian colonial pieza system in her monumental Black Metamorphosis, toward a cultural analysis grounded in the politics of being from the perspective of Fanon's autophobic subject. She analyzes how marginalized cultural formations like Myal, Rastafari, Vodou, and Jonkonnu, provide a zero ground and catalytic zone of resistance against European hegemony. Her work attempts to elucidate the development and maintenance of colonial modernity and modern man, and the possibility of resistance to its overrepresentation as the human, rather than one among many 'genres of the human.' She deftly interweaves science, philosophy, literary theory, and critical race theory to explain how European man came to be considered the epitome of humanity, "Man 2" or "the figure of man". Wynter's theoretical framework has changed and deepened over the years. In her essay "Towards the Sociogenic Principle: Fanon, Identity, the Puzzle of Conscious Experience, and What It Is Like to be 'Black'", Wynter developed a theoretical framework she refers to as the "sociogenic principle", which would become central to her work. Wynter derives this theory from an analysis of Frantz Fanon's notion of "sociogeny". Wynter argues that Fanon's theorization of sociogeny envisions human being (or experience) as not merely biological, but also based in stories and symbolic meanings generated within culturally specific contexts. Sociogeny as a theory therefore overrides, and cannot be understood within, Cartesian dualism for Wynter. The social and the cultural influence the biological. In her essay "Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument",[8] Wynter’s genealogy of “Man” offers a radical critique of Western humanism by tracing how the category of the human has been historically constructed. Her framework outlines a progression from Christian Man to Man1 and then Man2, each iteration reinforcing systems of exclusion and domination under the guise of universality. The first configuration, Christian Man, emerged during medieval Europe. In this formulation, “Man” was defined primarily in theological terms. The ideal human was a Christian subject, whose purpose was salvation through alignment with divine law. This concept was fundamentally spiritual and moral, centering Europe as the site of truth and divine favor. Non-Christians—pagans, Muslims, Jews, and Indigenous peoples—were dehumanized as infidels and excluded from this spiritual-humanist ideal. This model was replaced during the Renaissance and Enlightenment by Man1, associated with secular humanism and the rise of liberal rationality, also known as homo politicus. Man1 redefined the human in terms of reason, science, and empiricism, marking a shift from religious to political and rational criteria. Rooted in the works of figures like Descartes and Locke, this “rational Man” was implicitly white, male, bourgeois, and European. Wynter critiques this version of the human for universalizing a narrow, Eurocentric identity while excluding vast populations deemed irrational, primitive, or underdeveloped. Man1 enabled and justified transatlantic slavery, colonialism, and racial hierarchy by grounding difference in nature and reason. The most recent formation, Man2, develops through the rise of biocentric and evolutionary thinking in the 19th and 20th centuries. Here, the human is framed through the lens of Darwinian biology, economic behavior, and technocratic knowledge. Man2 becomes the homo oeconomicus of neoliberalism—an entrepreneurial, self-maximizing subject. This version of the human, while more secular and “objective,” still preserves racial and class exclusions by linking human worth to economic productivity and scientific rationality. It represents a continuation of the colonial logic, now masked by ostensibly post-racial, meritocratic ideals. Wynter’s genealogy reveals how each version of “Man” institutionalizes a “code of symbolic life and death,” a hijacking of what Danielli calls the "internal reward system" of human cognition, determining perceptions of who is fully human and who is not. She argues for a new conception of the human, building on the Fanonian "third event" of sociogeny, by which we can propose a Human that is both bios and logos, nature and culture. As such, she proposes a notion of species that moves beyond the overrepresentation of the Western, bourgeois, white male subject, and more generally, the dehumanizing biocentric notion of Man put into place by Europe since the 19th century. Her project calls for the reinvention of the human outside colonial and biocentric logics toward a plural, hybrid humanity grounded in poetics and culture, what she calls homo narrans (story-telling human) as we are shaped and continuously re-shape ourselves through the narratives we create. |

批評的著作 シルビア・ウィンターの学術的著作は極めて詩的であり、説明的であり、複雑である。彼女の長いキャリアにおいて、彼女はマルクス主義と脱植民地化に関する 様々な問題に取り組んできた。その分析的枠組みは、彼女の広範で学際的な読書から導かれたものである。彼女は人類学、社会学、哲学、認知科学、歴史学から 引用する。 ウィンターは文学批評を基盤として出発し、画期的な著作『ブラック・メタモルフォーゼ』ではイベリア植民地時代のピエサ制度をマルクス主義的に分析。さら にファノンの自己嫌悪的主体という視点から、存在の政治学に基づく文化分析へと展開した。マイアル、ラスタファリ、ヴードゥー、ジョンコンヌといった周縁 化された文化形成が、ヨーロッパのヘゲモニーに対する抵抗のゼロ地点かつ触媒的領域をいかに提供するかを分析している。 彼女の研究は、植民地的近代性と近代的人間の形成・維持、そして「人間のジャンル」の一つに過ぎない存在を「人間」として過剰に代表化することへの抵抗の 可能性を解明しようとする。科学、哲学、文学理論、批判的人種理論を巧みに織り交ぜ、いかにしてヨーロッパ人が「人間2」あるいは「人間の図式」として人 類の頂点と見なされるに至ったかを説明する。ウィンターの理論的枠組みは、年月を経て変化し深化してきた。 彼女の論文「社会発生原理へ向けて:ファノン、アイデンティティ、意識的経験の難題、そして『黒人であること』とは」において、ウィンターは「社会発生原 理」と呼ぶ理論的枠組みを構築した。これは彼女の研究の中核となるものとなる。ウィンターはこの理論を、フランツ・ファノンの「社会発生論」概念の分析か ら導出している。ウィンターは、ファノンの社会発生論の理論化が、人間(あるいは経験)を単なる生物学的存在ではなく、文化的に特異な文脈の中で生成され る物語や象徴的意味に基づく存在として構想していると論じる。したがってウィンターにとって、理論としての社会発生論はデカルト主義を凌駕し、その枠組み 内では理解できないものである。社会と文化は生物学に影響を与える。 ウィンターの論文「存在/権力/真実/自由の植民性への揺さぶり:人間へ、人間の後へ、その過剰表現——一論考」[8]において、「人間」の系譜学は、人 間のカテゴリーが歴史的に如何に構築されてきたかを辿ることで、西洋的人間主義への急進的批判を提供する。彼女の枠組みは、キリスト教的人間から人間1、 そして人間2へと進展する過程を概説し、各段階が普遍性の名のもとに排除と支配のシステムを強化してきたことを示す。 最初の形態であるキリスト教的人間は、中世ヨーロッパにおいて出現した。この概念において「人間」は主に神学的観点から定義された。理想的な人間とはキリ スト教徒の主体であり、その目的は神の法に順応することによる救済にあった。この概念は根本的に精神的・道徳的であり、ヨーロッパを真理と神の恩寵の中心 地として位置づけた。非キリスト教徒——異教徒、イスラム教徒、ユダヤ教徒、先住民——は異端者として非人間化され、この精神的ヒューマニズムの理想から 排除された。 このモデルはルネサンスと啓蒙主義の時代に、世俗的人間主義と自由主義的合理性の台頭と結びついた「人間1」——ホモ・ポリティクスとも呼ばれる——に 取って代わられた。Man1は人間を理性・科学・経験主義の観点から再定義し、宗教的基準から政治的・合理的基準への転換を示した。デカルトやロックらの 思想に根ざしたこの「理性的人間」は、暗黙のうちに白人・男性・ブルジョワ・ヨーロッパ人であった。ウィンターはこの人間像を批判する。なぜなら、非合理 的・原始的・未発達と見なされた膨大な人口を排除しつつ、狭隘なヨーロッパ中心主義的アイデンティティを普遍化したからだ。Man1は差異を自然と理性に 基づくものとして位置づけることで、大西洋奴隷貿易、植民地主義、人種的階層化を可能にし正当化した。 最新の形態であるMan2は、19~20世紀の生物中心主義的・進化的思考の台頭を通じて発展した。ここでは人間はダーウィニズム的生物学、経済行動、テ クノクラティックな知識のレンズを通して枠組みづけられる。マン2は新自由主義のホモ・エコノミクス——起業家精神に富み自己利益を最大化する主体——と なる。この人間像はより世俗的で「客観的」ながら、人間の価値を経済的生産性と科学的合理性に結びつけることで、依然として人種的・階級的排除を維持す る。これは植民地主義的論理の継続であり、今や表向きは人種を超えた能力主義的理想によって覆い隠されている。 ウィンターの系譜学は、各「人間」像がいかに「象徴的な生と死の規範」を制度化し、ダニエリが「人間の認知における内的報酬システム」と呼ぶものを乗っ取 り、誰が完全な人間であり誰がそうでないかの認識を決定づけるかを明らかにする。彼女はファノンの「第三の出来事」である社会生成論に基づき、新たな人間 観を提唱する。それは「生物(bios)」と「理性(logos)」、自然と文化を統合した「人間」の構想である。これにより西洋的・ブルジョワ的・白人 男性主体の過剰表現を超え、19世紀以降ヨーロッパが構築した非人間的な生物中心主義的人間観を脱却する種概念を提案する。彼女のプロジェクトは、植民地 主義的・生物中心論的論理の外側で人間を再発明することを求める。それは詩学と文化に根ざした多元的でハイブリッドな人間性、すなわち「ホモ・ナランス (物語る人間)」へと向かう。我々は自ら生み出す物語を通じて形作られ、絶えず自らを再形成する存在だからだ。 |

| Works Novel The Hills of Hebron. London: Jonathan Cape, 1962.[9][10] Extracted in Daughters of Africa (1992), ed. Margaret Busby.[11] Critical text Do Not Call Us Negros: How Multicultural Textbooks Perpetuate Racism (1992)[12] We Must Learn to Sit Down Together and Talk About a Little Culture: Decolonizing Essays 1967–1984 (2022)[13] Drama Miracle in Lime Lane (1959) Shh... It's a Wedding (1961) 1865 – A Ballad for a Rebellion (1965) The House and Land of Mrs. Alba (1968) Rockstone Anancy (1970) Maskarade (1973) Film The Big Pride (1961), with Jan Carew[14] Essays/criticism "The Instant-Novel Now". New World Quarterly 3.3 (1967): 78–81. "Lady Nugent's Journal". Jamaica Journal 1:1 (1967): 23–34. "We Must Learn to Sit Down Together and Talk about a Little Culture: Reflections on West Indian Writing and Criticism: Part One". Jamaica Journal 2:4 (1968): 23–32. "We Must Learn to Sit Down Together and Talk about a Little Culture: Reflections on West Indian Writing and Criticism: Part Two". Jamaica Journal 3:1 (1969): 27–42. "Book Reviews: Michael Anthony Green Days by the River and The Games Were Coming". Caribbean Studies 9.4 (1970): 111–118. "Jonkonnu in Jamaica: Towards the Interpretation of the Folk Dance as a Cultural Process". Jamaica Journal 4:2 (1970): 34–48. "Novel and History, Plot and Plantation". Savacou 5 (1971): 95–102. "Creole Criticism: A Critique". New World Quarterly 5:4 (1972): 12–36. "One-Love—Rhetoric or Reality?—Aspects of Afro-Jamaicanism". Caribbean Studies 12:3 (1972): 64–97. "After Word". High Life for Caliban. By Lemuel Johnson. Ardis, 1973. "Ethno or Socio Poetics". Alcheringa/Ethnopoetics 2:2 (1976): 78–94. "The Eye of the Other". Blacks in Hispanic Literature: Critical Essays. Ed. Miriam DeCosta-Willis. Kennikat Press, 1977. 8–19. "A Utopia from the Semi-Periphery: Spain, Modernization, and the Enlightenment". Science Fiction Studies 6:1 (1979): 100–107. "History, Ideology, and the Reinvention of the Past in Achebe's Things Fall Apart and Laye's The Dark Child". Minority Voices 2:1 (1978): 43–61. "Sambos and Minstrels". Social Text 1 (Winter 1979): 149–156. "In Quest of Matthew Bondsman: Some Cultural Notes on the Jamesian Journey". Urgent Tasks 12 (Summer 1981). Beyond Liberal and Marxist Leninist Feminisms: Towards an Autonomous Frame of Reference, Institute for Research on Women and Gender, 1982. "New Seville and the Conversion Experience of Bartolomé de Las Casas: Part One". Jamaica Journal 17:2 (1984): 25–32. "New Seville and the Conversion Experience of Bartolomé de Las Casas: Part Two". Jamaica Journal 17:3 (1984): 46–55. "The Ceremony Must Be Found: After Humanism". Boundary II 12:3 & 13:1 (1984): 17–70. "On Disenchanting Discourse: 'Minority' Literary Criticism and Beyond". Cultural Critique 7 (Fall 1987): 207–44. "Beyond the Word of Man: Glissant and the New Discourse of the Antilles". World Literature Today 63 (Autumn 1989): 637–647. "Beyond Miranda's Meanings: Un/Silencing the 'Demonic Ground' of Caliban's Women". Out of the Kumbla: Caribbean Women and Literature. Ed. Carole Boyce Davies and Elaine Savory Fido. Africa World Press, 1990. 355–372. "Columbus and the Poetics of the Propter Nos". Annals of Scholarship 8:2 (1991): 251–286. "Tras el 'Hombre,' su última palabra: Sobre el posmodernismo, les damnés y el principio sociogénico". La teoría política en la encrucijada descolonial. Nuevo Texto Crítico, Año IV, No. 7, (Primer Semester de 1991): 43–83. "'Columbus, The Ocean Blue and 'Fables that Stir the Mind': To Reinvent the Study of Letters". Poetics of the Americas: Race, Founding and Textuality 8:2 (1991): 251–286. "Rethinking 'Aesthetics': Notes Towards a Deciphering Practice". Ex-iles: Essays on Caribbean Cinema. Ed. Mbye Cham. Africa World Press, 1992. 238–279. "'No Humans Involved': An open letter to my colleagues". Voices of the African Diaspora 8:2 (1992). "Beyond the Categories of the Master Conception: The Counterdoctrine of the Jamesian Poiesis". C.L.R. James's Caribbean. Ed. Paget Henry and Paul Buhle. Duke University Press, 1992. 63–91. "But What Does Wonder Do? Meanings, Canons, Too?: On Literary Texts, Cultural Contexts, and What It's Like to Be One/Not One of Us". Stanford Humanities Review 4:1 (1994). "The Pope Must Have Been Drunk, the King of Castile a Madman: Culture as Actuality and the Caribbean Rethinking of Modernity". Reordering of Culture: Latin America, the Caribbean and Canada in the 'Hood. (1995): 17–42. "1492: A New World View" (1995), Race, Discourse, and the Origin of the Americas: A New World View. Ed. Sylvia Wynter, Vera Lawrence Hyatt, and Rex Nettleford. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995. 5–57. "Is 'Development' a Purely Empirical Concept, or also Teleological?: A Perspective from 'We the Underdeveloped'". Prospects for Recovery and Sustainable Development in Africa. Ed. Aguibou Y. Yansané. Greenwood, 1996. 299–316. "Columbus, the Ocean Blue, and 'Fables That Stir the Mind': To Reinvent the Study of Letters". Poetics of the Americas: Race, Founding and Textuality. Ed. Bainard Cowan and Jefferson Humphries. Louisiana State UP, 1997. 141–163. "'Genital Mutilation' or 'Symbolic Birth?' Female Circumcision, Lost Origins, and the Aculturalism of Feminist/Western Thought". Case Western Reserve Law Review 47.2 (1997): 501–552. "Black Aesthetic". The Encyclopedia of Aesthetics. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press, 1998. 273–281. "Africa, The West and the Analogy of Culture: The Cinematic Text After Man". Symbolic Narratives/African Cinema: Audiences, Theory and the Moving Image. Ed. June Givanni. London British Film Institute, 2000. 25–76. "The Re-Enchantment of Humanism: An Interview with Sylvia Wynter", Small Axe 8 (2000): 119–207. "'A Different Kind of Creature': Caribbean Literature, the Cyclops Factor and the Second Poetics of the Propter Nos". Annals of Scholarship 12:1/2 (2001). "Towards the Sociogenic Principle: Fanon, Identity, the Puzzle of Conscious Experience, and What It Is Like to be 'Black'". National Identities and Socio-Political Changes in Latin America. Ed. Mercedes F. Durán-Cogan and Antonio Gómez-Moriana. New York: Routledge, 2001. 30–66. "Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation – An Argument". CR: The New Centennial Review 3.3 (2003): 257–337. "On How We Mistook the Map for the Territory and Re-Imprisoned Ourselves in Our Unbearable Wrongness of Being, of Désêtre: Black Studies Toward the Human Project". Not Only the Master's Tools: African-American Studies in Theory and Practice. Eds. Lewis R. Gordon and Jane Anna Gordon. Paradigm, 2006. 107–169. "Proud Flesh Inter/Views Sylvia Wynter". Greg Thomas. ProudFlesh: A New Afrikan Journal of Culture, Politics & Consciousness 4 (2006). "Human Being as Noun, or Being Human as Praxis?: On the Laws/Modes of Auto-Institution and our Ultimate Crisis of Global Warming and Climate Change". Paper presented in the Distinguished Lecture and Residency at the Center for African American Studies, Wesleyan University, April 23, 2008. "Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species? Or, to Give Humanness a Different Future: Conversations". Interview. Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis. Duke, 2014. 9–89. "The Ceremony Found: Towards the Autopoetic Turn/Overturn, its Autonomy of Human Agency, and the Extraterritoriality of (Self-)Cognition". Black Knowledges/Black Struggles: Essays in Critical Epistemology. Eds Jason R. Ambroise and Sabine Broeck. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press, 2015. 184–252. Black Metamorphosis: New Natives in a New World (unpublished manuscript)[15] |

作品 小説 ヘブロンの丘。ロンドン:ジョナサン・ケープ、1962年。[9][10] 『アフリカの娘たち』(1992年)に収録、編者マーガレット・バスビー。[11] 批評的テキスト 我々をニグロと呼ぶな:多文化教科書が人種主義を永続させる方法(1992年)[12] 『共に座り、少しの文化について語り合うことを学ばねばならない:脱植民地化論集 1967–1984』(2022年)[13] 戯曲 『ライム・レーンの奇跡』(1959年) 『シーッ…結婚式だ』(1961年) 『1865年 – 反乱のバラッド』(1965年) アルバ夫人の家と土地(1968年) ロックストーン・アナンシー(1970年) 仮面舞踏会(1973年) 映画 ビッグ・プライド(1961年)、ジャン・キャルーと共同[14] エッセイ/批評 「インスタント小説の今」。『ニュー・ワールド・クォータリー』3巻3号(1967年):78–81頁。 「レディ・ニュージェントの日記」。『ジャマイカ・ジャーナル』1巻1号(1967年):23–34頁。 「我々は共に座り、少しの文化について語り合うことを学ばねばならない:西インド諸島の文学と批評に関する考察:第一部」。『ジャマイカ・ジャーナル』2 巻4号(1968年):23–32頁。 「共に座り、少しの文化について語ることを学ばねばならない:西インド諸島の文学と批評に関する考察:第二部」。『ジャマイカ・ジャーナル』3巻1号 (1969年):27–42頁。 「書評:マイケル・アンソニー『川辺の緑の日々』と『試合が近づいていた』」。『カリブ研究』9巻4号(1970年):111–118頁。 「ジャマイカのジョンコンヌ:民俗舞踊を文化的プロセスとして解釈する試み」。『ジャマイカ・ジャーナル』4巻2号(1970年):34–48頁。 「小説と歴史、プロットとプランテーション」。『サヴァクー』5号(1971年):95–102頁。 「クレオール批評:批判的考察」。ニュー・ワールド・クォータリー 5巻4号 (1972年): 12–36頁。 「ワン・ラブ―修辞か現実か?―アフロ・ジャマイカニズムの諸相」。カリブ研究 12巻3号 (1972年): 64–97頁。 「あとがき」。『ハイ・ライフ・フォー・カリバン』。レミュエル・ジョンソン著。アーディス社、1973年。 「エスノ詩学か社会詩学か」。『アルケリンガ/エスノポエティクス』2巻2号(1976年):78–94頁。 「他者の眼」。『ヒスパニック文学における黒人:批評論集』。ミリアム・デコスタ=ウィリス編。ケニカット・プレス、1977年。8–19頁。 「半周縁からのユートピア:スペイン、近代化、啓蒙主義」。『サイエンス・フィクション研究』6巻1号(1979年):100–107頁。 「歴史、イデオロギー、そして過去の再創造——アチェベ『崩れゆくもの』とレイ『闇の子』において」。『マイノリティ・ヴォイシズ』2巻1号(1978 年):43–61頁。 「サンボとミンストレル」。『ソーシャル・テキスト』1号(1979年冬):149–156頁。 「マシュー・ボンズマンを求めて:ジェイムズ的旅路に関する文化的所見」。『アーガント・タスク』12号(1981年夏)。 リベラル・マルクス主義・レーニン主義フェミニズムを超えて:自律的参照枠へ向けて、女性・ジェンダー研究所、1982年。 「新セビリアとバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスの改宗体験:第一部」。『ジャマイカ・ジャーナル』17:2 (1984): 25–32頁。 「新セビリアとバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスの改宗体験:第二部」。『ジャマイカ・ジャーナル』17巻3号(1984年):46–55頁。 「儀式は発見されねばならない:ヒューマニズムの後に」。『バウンダリーII』12巻3号 & 13巻1号(1984年):17–70頁。 「脱魔術化言説について:『マイノリティ』文学批評とその先」『文化批評』7 (1987年秋): 207–44。 「人間の言葉を超えて:グリッサントとアンティル諸島の新しい言説」『ワールド・リテラチャー・トゥデイ』63 (1989年秋): 637–647。 「ミランダの意味を超えて:カリバンの女性たちの『悪魔的な基盤』を沈黙させる/沈黙を解く」。『クンブラから:カリブ海の女性たちと文学』。キャロル・ ボイス・デービス、エレイン・サヴォリー・フィド編。アフリカ・ワールド・プレス、1990年。355–372。 「コロンブスとプロプター・ノスの詩学」。『学問年報』8:2 (1991): 251–286. 「『人間』の背後にある、その最後の言葉:ポストモダニズム、呪われた者たち、そして社会発生の原理について」。『脱植民地化の岐路に立つ政治理論』。 Nuevo Texto Crítico、第 4 年、第 7 号、(1991 年前期): 43–83頁。 「コロンブス、青い海、そして『心を揺さぶる寓話』:文学研究の再構築に向けて」。『アメリカ大陸の詩学:人種、建国、テクスト性』8巻2号(1991 年):251–286頁。 「『美学』の再考:解読実践に向けた覚書」。『亡命者たち:カリブ映画論集』。Mbye Cham編。アフリカ・ワールド・プレス、1992年。238–279頁。 「『人間は関与していない』:同僚たちへの公開書簡」。『アフリカン・ディアスポラの声』8巻2号(1992年)。 「支配概念の枠を超え:ジェームズ的ポイエーシスの反論」。『C.L.R.ジェームズのカリブ』パジェット・ヘンリー、ポール・ビューレ編。デューク大学 出版局、1992年。63–91頁。 「しかし驚異は何をもたらすのか? 意味、規範、そして我々自身について: 文学テキスト、文化的文脈、そして我々の一員であること/そうでないことの在り方について」。『スタンフォード人文レビュー』4巻1号(1994年)。 「教皇は酔っていたに違いない、カスティーリャ王は狂人だった:現実としての文化とカリブにおける近代性の再考」。『文化の再編成:ラテンアメリカ、カリ ブ、そしてカナダの「フッド」における』 (1995): 17–42. 「1492: 新しい世界観」 (1995), 『人種、言説、そしてアメリカ大陸の起源: 新しい世界観』. 編者: シルビア・ウィンター、ベラ・ローレンス・ハイアット、レックス・ネットルフォード. スミソニアン協会出版局, 1995. 5–57. 「『開発』は純粋に経験的な概念か、それとも目的論的な概念か?『我ら、発展途上国』からの視点」。『アフリカの回復と持続可能な開発の見通し』。編者: アギブー・Y・ヤンサネ。グリーンウッド、1996年。299-316。 「コロンブス、青い海、そして『心を揺さぶる寓話』:文学研究の再構築」。アメリカ大陸の詩学:人種、建国、そしてテキスト性。ベイナード・カウアン、 ジェファーソン・ハンフリーズ編。ルイジアナ州立大学出版、1997年。141-163。 「『性器切除』か『象徴的な誕生』か?女性割礼、失われた起源、そしてフェミニスト/西洋思想の非文化主義」 『ケース・ウェスタン・リザーブ・ロー・レビュー』47巻2号(1997年):501–552頁。 「黒人美学」。『美学事典』第1巻。オックスフォード大学出版局、1998年。273–281頁。 「アフリカ、西洋、そして文化の類比:人間を超えた映画的テクスト」。象徴的ナラティブ/アフリカ映画:観客、理論、そして動く映像。編者:ジューン・ジ バンニ。ロンドン英国映画協会、2000年。25–76頁。 「ヒューマニズムの再魔術化:シルビア・ウィンターとの対談」。『スモール・アックス』8号(2000年):119–207頁。 「『異なる存在』:カリブ文学、サイクロプス要因、そしてプロプテル・ノスの第二詩学」。『学術年報』12巻1/2号(2001年)。 「社会発生原理へ向けて:ファノン、アイデンティティ、意識的経験の難題、そして『黒人であること』とは何か」。『ラテンアメリカにおける国民的アイデン ティティと社会政治的変容』メルセデス・F・デュラン=コーガン、アントニオ・ゴメス=モリアーナ編、ニューヨーク:ラウトリッジ、2001年、 30–66頁。 「存在/権力/真実/自由の植民性への揺さぶり:人間へ、人間の後へ、その過剰表現へ――一考察」 CR: The New Centennial Review 3.3 (2003): 257–337. 「我々が地図を領土と誤認し、耐え難き存在の誤謬、デゼストレの中に自らを再投獄した経緯について:人間プロジェクトへ向けたブラック・スタディーズ」 『主人の道具だけではない:理論と実践におけるアフリカ系アメリカ人研究』ルイス・R・ゴードン、ジェーン・アンナ・ゴードン編、パラダイム社、2006 年、107–169頁。 「誇り高き肉体がシルヴィア・ウィンターを問う」グレッグ・トーマス。ProudFlesh: A New Afrikan Journal of Culture, Politics & Consciousness 4 (2006)。 「人間を名詞として、あるいは人間性を実践として?:自己制度化の法則/様式と地球温暖化・気候変動という究極の危機について」。2008年4月23日、 ウェズリアン大学アフリカ系アメリカ人研究センターにおける特別講演・レジデンシーにて発表。 「我々の種にとって比類なき大災害か? あるいは、人間性に異なる未来を与えるために:対話」。インタビュー。シルヴィア・ウィンター『実践としての人間であることについて』。デューク大学出版 局、2014年。9–89頁。 「発見された儀式:オートポエティックな転換/転覆へ、その人間の行為主体の自律性、および(自己)認識の域外性について」。『ブラック・ナレッジ/ブ ラック・ストラグルズ:批判的認識論のエッセイ』ジェイソン・R・アンブローズ、サビーヌ・ブローケ編。英国リヴァプール:リヴァプール大学出版局、 2015年。184–252頁。 『ブラック・メタモルフォーゼ:新世界における新たなネイティブ』(未発表原稿)[15] |

| 1. Balderston, Daniel; Gonzalez,

Mike (2004). Encyclopedia of Latin American and Caribbean literature,

1900-2003. Routledge. p. 614. ISBN 9781849723336. OCLC 941857387. 2. Chang, Victor L. (1986). "Sylvia Winter (1928 - )". In Dance, Daryl C. (ed.). Fifty Caribbean Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 498–507. ISBN 978-0-313-23939-7. 3. "St. Andrew High Sch". The Daily Gleaner [Jamaica]. 26 November 1937. 4. Scott, David (September 2000). "The Re-Enchantment of Humanism: An Interview with Sylvia Wynter". Small Axe (8): 119–207. 5. "Putting the Drama in Touch with Contemporary Life". The Times [London]. Times Newspapers Limited. 19 March 1958. p. 3. 6. "Five get OJ", Jamaica Observer, 6 August 2010. 7. "Sylvia Wynter awarded the Order of Jamaica - Hon Professor Wynter's response to the letter of congratulations on her award sent by Professor Brian Meeks on behalf of the CCT", Centre for Caribbean Thought, University of the West Indies at Mona, Jamaica. 8. Wynter, Sylvia (September 2003). "Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation--An Argument". CR: The New Centennial Review. 3 (3): 257–337. doi:10.1353/ncr.2004.0015. ISSN 1539-6630. 9. Baird, Keith E. (Winter 1963). "Review of The Hills of Hebron". Freedomways. 3: 111–112. 10. Charles, Pat (1963). "Review of The Hills of Hebron". Bim. 9 (36): 292. 11. "Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Words and Writings by..." Library Thing. Ballantine Books. 1994. ISBN 978-0-345-38268-9. Retrieved 23 October 2021. 12. Wynter, Sylvia (1992). Do Not Call Us Negros: How "Multicultural" Textbooks Perpetuate Racism. Aspire. ISBN 9780935419061. 13. Wynter, Sylvia (2022). We Must Learn to Sit Down Together and Talk About a Little Culture: Decolonizing Essays 1967–1984. Peepal Tree Press, Limited. ISBN 9781845231088. 24. "BFI Screenonline: Big Pride, The (1961)". www.screenonline.org.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2019. 15. Kamugisha, Aaron (1 March 2016). ""That Area of Experience That We Term the New World": Introducing Sylvia Wynter's "Black Metamorphosis"". Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism. 20 (1 (49)): 37–46. doi:10.1215/07990537-3481522. ISSN 0799-0537. S2CID 147385772. |

1.

バルダーストン、ダニエル;ゴンザレス、マイク(2004)。『ラテンアメリカ・カリブ文学事典

1900-2003』。ラウトレッジ。614頁。ISBN 9781849723336。OCLC 941857387。 2. チャン、ビクター L. (1986). 「シルビア・ウィンター (1928 - )」. ダンス、ダリル C. (編). 『50人のカリブ海作家:伝記・書誌・批評資料集』. グリーンウッド出版グループ. pp. 498–507. ISBN 978-0-313-23939-7. 3. 「セント・アンドルー高校」 『デイリー・グリーナー』 [ジャマイカ]。1937年11月26日。 4. スコット、デイヴィッド (2000年9月)。「ヒューマニズムの再魅惑:シルヴィア・ウィンターへのインタビュー」 『スモール・アックス』 (8): 119–207。 5. 「現代生活と演劇の接点」『タイムズ』[ロンドン]。タイムズ・ニューズペーパーズ・リミテッド。1958年3月19日。3ページ。 6. 「5人に無罪判決」『ジャマイカ・オブザーバー』2010年8月6日。 7. 「シルビア・ウィンター、ジャマイカ勲章を受章―CCT代表ブライアン・ミークス教授の祝賀状に対するウィンター名誉教授の返答」カリブ思想センター、西 インド諸島大学モナ校(ジャマイカ)。 8. ウィンター、シルビア(2003年9月)。「存在/権力/真実/自由の植民地性を揺るがす:人間へ、人間の後へ、その過剰表現――一論考」。CR:ザ・ ニュー・センテニアル・レビュー。3巻3号:257–337頁。doi:10.1353/ncr.2004.0015. ISSN 1539-6630. 9. ベアード、キース・E.(1963年冬)。「『ヘブロンの丘』書評」。『フリーダムウェイズ』。3: 111–112. 10. チャールズ、パット(1963年)。「『ヘブロンの丘』書評」。『ビム』9巻36号:292頁。 11. 「アフリカの娘たち:国際アンソロジー——言葉と著作集」. ライブラリー・シング. バランタイン・ブックス. 1994年. ISBN 978-0-345-38268-9。2021年10月23日取得。 12. ウィンター、シルビア(1992)。『我々をニグロと呼ぶな:「多文化」教科書が人種主義を永続させる方法』。アスパイア。ISBN 9780935419061。 13. ウィンター、シルビア(2022)。『共に座り、少しの文化について語ることを学ばねばならない:脱植民地化エッセイ集 1967–1984』。ピーパル・ツリー・プレス社。ISBN 9781845231088。 24. 「BFI Screenonline: ビッグ・プライド (1961)」. www.screenonline.org.uk. 2019年1月25日閲覧. 15. カムギシャ, アーロン (2016年3月1日). 「我々が新世界と呼ぶ経験の領域」: シルヴィア・ウィンター『ブラック・メタモルフォーゼ』の紹介. スモール・アックス:カリブ批評ジャーナル。20巻1号(49号):37–46頁。doi:10.1215/07990537-3481522。ISSN 0799-0537。S2CID 147385772。 |

| Sources Buck, Claire (ed.), Bloomsbury Guide to Women's Literature. London: Bloomsbury, 1992. ISBN 0-7475-0895-X Wynter, Sylvia, and David Scott. "The Re-Enchantment of Humanism: An Interview with Sylvia Wynter". Small Axe, 8 (September 2000): 119–207. Wynter, Sylvia. "Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument". CR: The New Centennial Review, Volume 3, Number 3, Fall 2003, pp. 257–337. Further reading Jason R. Ambroise, "On Sylvia Wynter's Darwinian Heresy of the 'Third Event'". American Quarterly 70, no 4 (December 2018): 847–856. Anthony Bogues (ed.), After Man, Towards the Human: Critical Essays on Sylvia Wynter, 2006. Kamau Brathwaite, "The Love Axe/1; Developing a Caribbean Aesthetic", BIM, 16 July 1977. Daryl Cumber Dance (ed.), Fifty Caribbean Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook, 1986. Demetrius L. Eudell, "'Come on Kid, Let’s Go Get the Thing': The Sociogenic Principle and the Being of Being Black/Human". Black Knowledges/Black Struggles: Essays in Critical Epistemology. Ed. Jason Ambroise and Sabine Broeck. Liverpool University Press, 2015. 21–43. Demetrius L. Eudell, "From Mode of Production to Mode of Auto-Institution: Sylvia Wynter's Black Metamorphosis of the Labor Question". Small Axe 49 (March 2016): 47–61. Karen M. Gagne, "On the Obsolescence of the Disciplines: Frantz Fanon and Sylvia Wynter Propose a New Mode of Being Human". Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 5 (2007): 251–264. Kelly Baker Josephs, "The Necessity for Madness: Negotiating Nation in Sylvia Wynter’s The Hills of Hebron". Disturbers of the Peace: Representations of Madness in Anglophone Caribbean Literature. University of Virginia Press, 2013. 45–68. David Scott. "Preface: Sylvia Wynter's Agonistic Intimations". Small Axe 49 (March 2016): vii–x. Greg Thomas, "The Body Politics of 'Man' and 'Woman' in an 'Anti-Black' World: Sylvia Wynter on Humanism's Empire (A Critical Resource Guide)". On Maroonage: Ethical Confrontations with Anti-Blackness. Ed. P. Khalil Saucier and Tryon P. Woods. Africa World, 2015. 67–107. Greg Thomas, "Marronnons / Let's Maroon: Sylvia Wynter's Black Metamorphosis as a Species of Maroonage". Small Axe 49 (March 2016): 62–78. Shirley Toland-Dix, "The Hills of Hebron: Sylvia Wynter’s Disruption of the Narrative of the Nation". Small Axe: 25 (February 2008): 57–76. Derrick White. "Black Metamorphosis: A Prelude to Sylvia Wynter’s Theory of the Human". The C.L.R. James Journal 16.1 (2010): 127–48. Sylvia Wynter, Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis. Katherine McKittrick, (ed). Duke University Press, 2014. Giorgis, Hannah (3 June 2019). "'When They See Us' and the Persistent Logic of 'No Humans Involved'". The Atlantic. External links |

出典 バック、クレア(編)『ブルームズベリー女性文学ガイド』ロンドン:ブルームズベリー、1992年。ISBN 0-7475-0895-X ウィンター、シルビア、デイヴィッド・スコット「ヒューマニズムの再魔術化:シルビア・ウィンターへのインタビュー」『スモール・アックス』8号 (2000年9月): 119–207頁。 ウィンター、シルヴィア。「存在/権力/真実/自由の植民地性を揺るがす:人間へ、人間の後へ、その過剰表現へ―一論考」。『CR:ザ・ニュー・センテニ アル・レビュー』第3巻第3号、2003年秋、257–337頁。 追加文献(さらに読む) ジェイソン・R・アンブロワーズ「シルヴィア・ウィンターの『第三の出来事』というダーウィニズム的異端について」。『アメリカン・クォーターリー』70 巻4号(2018年12月):847–856頁。 アンソニー・ボーグス編『人間を超えて、人間へ:シルヴィア・ウィンター批評論集』、2006年。 カマウ・ブラスウェイト「愛の斧/1;カリブ美学の展開」『BIM』1977年7月16日号。 ダリル・カンバーダンス編『カリブ作家50人:伝記・書誌・批評資料集』1986年。 デメトリウス・L・ユーデル「『さあ行こう、あのものを手に入れよう』:社会生成原理と黒人/人間であることの本質」『ブラック・ナレッジ/ブラック・ス トラグルズ:批判的認識論論集』ジェイソン・アンブローズ、サビーヌ・ブローケ編、リヴァプール大学出版局、2015年、21–43頁。 デメトリウス・L・ユーデル「生産様式から自己制度化様式へ:シルヴィア・ウィンターの労働問題における黒人的変容」『スモール・アックス』49号 (2016年3月):47–61頁。 カレン・M・ギャグネ「学問分野の陳腐化について:フランツ・ファノンとシルヴィア・ウィンターが提案する新たな人間存在様式」 ヒューマン・アーキテクチャー:自己認識社会学ジャーナル 5 (2007): 251–264. ケリー・ベイカー・ジョセフス、「狂気の必要性:シルビア・ウィンター『ヘブロンの丘』における国民の交渉」。『平穏の妨害者たち:英語圏カリブ文学にお ける狂気の表象』。バージニア大学出版局、2013年。45–68頁。 デイヴィッド・スコット。「序文:シルヴィア・ウィンターの闘争的示唆」。『スモール・アックス』49号(2016年3月):vii–x頁。 グレッグ・トーマス「『反黒人』世界における『男』と『女』の身体政治学:ヒューマニズムの帝国に関するシルビア・ウィンターの考察(批判的リソースガイ ド)」『マローンについて:反黒人主義との倫理的対峙』P.カリル・ソーシエ、トライオン・P・ウッズ編、アフリカ・ワールド、2015年、67–107 頁。 グレッグ・トーマス「マロンノン/レッツ・マローン:シルヴィア・ウィンターの『黒人変容』をマローンの一形態として」『スモール・アックス』49号 (2016年3月):62–78頁。 シャーリー・トーランド=ディックス「ヘブロンの丘:シルヴィア・ウィンターによる国民物語の破壊」 スモール・アックス 25号(2008年2月):57–76頁。 デリック・ホワイト「黒人変容:シルビア・ウィンターの人間論への序曲」。C.L.R.ジェームズ・ジャーナル 16.1号(2010年):127–48頁。 シルヴィア・ウィンター『シルヴィア・ウィンター:実践としての人間存在について』。キャサリン・マッキトリック編。デューク大学出版局、2014年。 ジョージス、ハンナ(2019年6月3日)。「『彼らが見たもの』と『人間は関与していない』という持続的な論理」。アトランティック誌。 外部リンク |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sylvia_Wynter |

|

| Quotes Public officials of the judicial system of Los Angeles routinely use the acronym ‘N.H.I.’ to refer to any case that involved a breach of the rights of young Black males who belonged to the jobless category of the inner city ghettos. N.H.I. means ‘no humans involved.’ “‘No Humans Involved’: An Open Letter to My Colleagues.” Knowledge on Trial 1 (1994) Hills of Hebron (1962 novel) It was early morning. There were mists over the hills and valleys of Hebron. Down in the square, Aunt Kate sat on the cold earth beside the spring. She rocked to and fro and cradled her arms as she hummed a lullaby. The clear water murmured an accompaniment. She had dressed hurriedly, and her cotton frock was unfastened at the back, her headkerchief askew, like a crumpled hibiscus. A light wind lifted the loose strands of her grey hair. Her face was oval. Pouches of reddish-brown skin framed a beaked nose and black eyes as swift as bees. The sound of feet squelching on wet grass, of people greeting each other, carried towards her. She remained still and listened. Then she smiled and nodded. Her lips formed words that were propitiatory echoes. The part of her mind which was secret and cunning accepted that she would have to pretend to practise rites which the others used to assure a reality from which she had escaped. For the others were not without power. If they demanded her involvement in their conspiracy, she needed them in hers. (beginning of 1: The Vow) In the silence that followed, the bubble of the morning's celebrations was shattered and the fragments went spinning away like the mist in the morning light. (from 1: The Vow) The sun reared up over Hebron like a wild horse. It streamed across the sky, tangled with the naked branches of trees, brightened the hills, illuminated winding paths, glittered like incandescent dust on the heads and shoulders, the marching feet of the congregation; rimmed their flags and banners with light, and settled in the gleaming river of morning that flooded the land. (7: The Money-Box) Ann sat in the back of the cart, and, as they drove off, she waved to Aunt Kate. The old woman did not wave back. The past had taken over in her mind once more. (7: The Money-Box) In the square not even the ghost of a wind stirred the naked trees. Aware of the creeping death around them, the children no longer played by the spring. They remained at home, lingering by their mothers or sitting on the doorstep beside their fathers. And they wondered at the silences which had sprung up between their parents, between neighbour and neighbour. (6: The Star-Apple Tree ) [He] heard her singing and knew that she had forgotten him already, that in the morning, if she remembered him, it would be with the vagueness of an indistinct dream. And knew that, walking away from her, he was walking away from the land and the people whose reflected image of him had shaped his dreams, fashioned the self that he would now go in search of, to be swept away into the wide indifference of the sea. (19: The Rape) ...as he sat waiting, he took up a fragment of wood and carved idly, thinking of making a toy for the child. Then as he shaped the rough outlines of a doll, he began to concentrate. For the first time in his life he created consciously, trying to embody in his carving his new awareness of himself and of Hebron. When he had finished he put the doll in his pocket, and left Hebron as twilight settled into the hollow spaces between the hills. He took the short cut down the hill-side that by-passed the church. From time to time he touched the doll as if it were a fetish. For, in carving the doll, [he] had stumbled upon God. (20: The Return) As he returned to the congregation he sought for words to share with them the long journey that he had taken. He sought for words to tell them of the world that he had entered where there were no far places and no strangers: only men, like themselves, who would one day inhabit together the same new continents of the spirit, the same planets of the imagination. (21: The Journey) from interviews/conversations with offshoot journal (2021) The cheap and easy radicalism does not address the underlying requirement for a total transformation—who are we as Black people, as Africans? The Marxists, and actually no party could give us that. Only we could do it! That is the easy way. The hard way is to reclaim our past, present and future selves, totally! in this country we must begin to think about education as an initiation into a world full of symbols and descriptions about who we are. Thinking of it as initiation helps us to understand the importance of introducing something else into the lives and worlds of children. Initiation also gives an understanding of the symbolic significance of education, and how language and art structure the whole of our existence. We need to re-initiate ourselves, a symbolic life through death, and create ourselves anew! The affliction of today is one concerned with who we are—and the need for a we. The question is, “What will be the cure?” That is where the Third Event becomes important you see, because it is a recognition that we are a species, but not in the manner we have been accustomed to, that we can narrate this problem in a different way. Where Africa as our ‘origin’ becomes important is in recognizing that if we are going to tell a different story of ourselves, we must grapple with the beginnings, in which Africa is not only important for Blacks but the key. They want us to think about Africa as a way to think about affliction but it is Africa that gives us so much of our language world, and gave us much of what has been transformed over time, and continues of course into the present. And so you see, we cannot have the Third Event without Africa right at the middle—because how do you tell the story differently if the beginning hasn’t been grappled with? this is where the potential of Black studies was! Language is the way that we will carry ourselves out of these problems we have—that is what is important now to remember about Black studies during those early years, that it was one part of a bigger project of developing a transformation of knowledge and therefore the transformation of the whole of society, by using a different language to address these intellectual concerns. Quotes about When you talk about women writers in the Caribbean, I would say she would be up on top, and second to nobody...An exceptional woman. C. L. R. James, in New World Adams : conversations with contemporary West Indian writers (1992) |

引用 ■ロサンゼルス司法制度の公職者は、都市部のゲットーに属する失業層の若い黒人男性の権利侵害事件を指す際、日常的に「N.H.I.」という略語を用いる。 N.H.I.とは「人間は関与していない」を意味する。 ■ 「『人間は関与していない』:同僚たちへの公開書簡」『裁判にかけられた知識』1 (1994) ヘブロンの丘 (1962年小説) 早朝だった。ヘブロンの丘と谷には霧がかかっていた。広場の下では、ケイトおばさんが泉のそばの冷たい地面に座っていた。彼女は前後に揺れながら腕を抱 え、子守唄を口ずさんでいた。澄んだ水が伴奏のようにささやく。彼女は急いで着替えたため、綿のワンピースは背中で留められておらず、頭巾はくしゃくしゃ のハイビスカスのように斜めにかかっていた。そよ風が彼女の白髪混じりの髪をなびかせた。顔は卵形だった。赤茶けた皮膚のたるみが、鷲鼻と蜂のように素早 い黒い瞳を縁取っていた。濡れた草を踏みしめる足音、人民が挨拶を交わす声が彼女の方へ届いた。彼女はじっと立ち止まり、耳を澄ました。そして微笑み、う なずいた。唇が形作った言葉は、なだめるような反響だった。彼女の心の奥底にある、秘密めいた狡猾な部分が認めたのは、自分が逃れた現実を他者が確かなも のとするために用いる儀式を、見せかけだけでも行わねばならないという事実だった。なぜなら他者にも力はある。彼らが彼女を共謀に巻き込もうとするなら、 彼女もまた彼らを自分の計画に必要とするのだ。(『誓い』1章冒頭より) ■ 続く静寂の中で、朝の祝祭の泡は砕け散り、その破片は朝日に溶ける霧のように渦巻きながら消えていった。(第1部:誓いより) 太陽はヘブロンの上空に野馬のように跳ね上がった。空を駆け抜け、裸木の枝と絡み合い、丘を明るく照らし、曲がりくねった小道を照らし、集会の者たちの頭 や肩、行進する足元に白熱した塵のようにきらめいた。旗や幟の縁を光で縁取り、大地を浸す朝の輝く川に沈んでいった。(7:貯金箱より) アンは荷車の後部座席に座り、出発するとケイトおばさんに手を振った。老女は手を振り返さなかった。彼女の心は再び過去に支配されていた。(7: 貯金箱) 広場の裸木を揺らす風の一片すらなかった。子供たちは周囲に忍び寄る死を悟り、泉辺で遊ぶことをやめた。家に留まり、母のそばに寄り添ったり、父の横の戸 口に座ったりしていた。そして親同士、隣人同士に生じた沈黙に、彼らは不思議に思ったのだ。(6: 星のリンゴの木) [彼は]彼女の歌声を聞き、彼女がもう自分を忘れたのだと悟った。朝になっても、仮に思い出しても、それはぼんやりとした夢のような曖昧さだろうと。そし て彼女から離れていくことは、この土地と人民から離れていくことだと知った。彼らの映し出した自分の姿が夢を形作り、今まさに探し求める自己を創り上げて きたのだ。やがて彼は海の広大な無関心の中に飲み込まれていく。(19: 強姦) ...待ちながら、彼は木の欠片を手に取り、子供へのおもちゃを作ろうと思いながら、ぼんやりと彫り始めた。そして人形の粗い輪郭を形作ると、集中し始め た。人生で初めて、彼は意識的に創作した。自らの新たな自覚とヘブロンへの認識を、彫刻に込めようとしたのだ。完成すると、彼は人形をポケットにしまい、 丘の間の窪みに夕闇が降りる頃、ヘブロンを後にした。教会を迂回する丘の斜面の近道を選んだ。時折、まるで魔除けのように人形に触れた。なぜなら、その人 形を彫る過程で、彼は神に遭遇したのだ。(20: 帰還) 会衆のもとへ戻る途中、彼は自らの長い旅路を共有する言葉を探した。彼が入った世界について語る言葉を探した。そこには遠い場所もよそ者も存在せず、ただ 彼ら自身と同じ人間たちが、いつの日か共に新たな精神の大陸、想像力の惑星に住むのだと伝える言葉を探した。(21: 旅路) インタビュー/対話より オフシュート・ジャーナルとの対話 (2021) ■ 安易な急進主義は根本的な変革の必要性に答えない——我々黒人民衆として、アフリカ人として、我々とは何者なのか?マルクス主義者も、実際どの政党もそれ を与えられはしない。我々自身だけが成し得るのだ!それが安易な道だ。困難な道とは、過去・現在・未来の自己を完全に奪還することだ! ■ この国では、教育を「我々とは何か」についての象徴と記述に満ちた世界への入門として考え始める必要がある。入門と捉えることで、子供たちの生活と世界に 何か別のものを導入する重要性が理解できる。入門はまた、教育の象徴的意義、言語と芸術が我々の存在全体をいかに構造化しているかを理解させる。我々は自 らを再入門させねばならない——死を通じた象徴的な生を、そして自らを新たに創造するのだ! ■ 今日の病は、我々が何者であるか――そして「我々」という集合体の必要性に関わるものだ。問題は「その治療法は何か?」である。ここで第三の出来事が重要 になる。それは我々が一つの種族であることを認識する点で、しかし慣れ親しんだ方法ではなく、この問題を異なる方法で語れることを示すからだ。 ■ アフリカが我々の「起源」として重要になるのは、もし我々が自分たちの異なる物語を語るなら、始まりと向き合わねばならないという認識においてだ。そこで はアフリカは黒人にとって重要であるだけでなく、鍵となる。彼らは苦しみを考える手段としてアフリカを考えさせようとするが、実はアフリカこそが我々の言 語世界の多くを与え、時を経て変容した多くのものを与え、そしてもちろん現在へと続いているのだ。だから分かるだろう、アフリカを中核に据えなければ第三 の出来事などありえないのだ——始まりと向き合わずに、どうやって物語を異なる形で語れるというのか? ■ ここにこそブラック・スタディーズの可能性があったのだ!言語こそが、我々が抱える問題から自らを解き放つ手段だ——初期のブラック・スタディーズにおい て今こそ思い出すべきは、それが知識の変革、ひいては社会全体の変革を目指す大プロジェクトの一端であったことだ。異なる言語を用いてこれらの知的課題に 取り組むことで。 引用について カリブ海の女性作家について語るなら、彼女は頂点に立つ存在であり、誰にも劣らない…並外れた女性だ。 C. L. R. ジェームズ、『ニュー・ワールド・アダムス:現代西インド諸島作家との対話』(1992年)より |

| https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Sylvia_Wynter |

|

| The politics of decolonial

investigations / Walter D. Mignolo, Duke University Press , 2021

. - (On decoloniality / a series edited by Walter D. Mignolo and

Catherine E. Walsh) Racism as we sense it today Islamophobia/Hispanophobia Dispensable and bare lives Decolonizing the nation-state The many faces of cosmo-polis Cosmopolitan and the decolonial option From "human" to "living" rights Decolonial reflections on hemispheric partitions Delinking, decoloniality, and de-Westernization The South of the North and the West of the East. Mariátegui and Gramsci in "Latin" America Sylvia Wynter : what does it mean to be human? Decoloniality and phenomenology The third nomos of the earth Epilogue: Yes, we can : border thinking, colonial epistemic/aesthesic differences and pluriversality |

脱植民地化研究の政治学 / ウォルター・D・ミニョーロ、デューク大学出版局、2021年。 - (脱植民地性について / ウォルター・D・ミニョーロとキャサリン・E・ウォルシュ編シリーズ) 現代における人種主義の実態 イスラム恐怖症/ヒスパノフォビア 使い捨ての裸の生 国民の脱植民地化 コスモポリスの多様な姿 コスモポリタンと脱植民地化の選択肢 「人間」の権利から「生きる」権利へ 半球的分断に関する脱植民地的考察 脱連結、脱植民地性、脱西洋化 北の南と東の西 「ラテン」アメリカにおけるマリアテギとグラムシ シルビア・ウィンター:人間であるとはどういうことか? 脱植民地性と現象学 地球の第三のノモス エピローグ:イエス、ウィー・キャン:境界思考、植民地的認識論的/美的差異、そして多元性 |

☆Black Metamorphosis

| Black Metamorphosis:

New Natives in a New World is an unpublished manuscript written by

Sylvia Wynter. The work is a seminal piece in Black Studies and uses

diverse fields to explain Black experiences and presence in the

Americas. The manuscript is nine-hundred and thirty-five pages with chapters of varying lengths.[1][2] Throughout the seventies and early eighties, Wynter worked with the Center for Afro-American Studies (CAAS) at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) to complete the project which was to be published by the Institute of the Black World (IBW). The manuscript presents early iterations of Wynter's Theory of the Human[1] and explores how Black experiences are essential to understanding the history of the New World[3] |

『ブラック・メタモルフォーシス:新世界における新たな先住民』は、シ

ルビア・ウィンターが執筆した未発表の原稿である。この著作はブラック・スタディーズにおける先駆的な作品であり、多様な分野を用いてアメリカ大陸におけ

る黒人の経験と存在を説明している。 原稿は935ページに及び、章の長さは様々である。[1] [2] 1970年代から1980年代初頭にかけて、ウィンターはカリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校(UCLA)のアフロ・アメリカン研究センター(CAAS)と 連携し、ブラック・ワールド研究所(IBW)による出版を目的として本プロジェクトを完成させた。この原稿はウィンターの『人間論』[1]の初期段階を提 示し、新世界[3]の歴史を理解する上で黒人の経験がいかに本質的であるかを探求している。 |

| Background In 1971, Wynter attended the Association for Commonwealth Literature and Language Studies (ACLALS) conference held in the Caribbean. There, she met African American historian Vincent Harding and wrote him a letter detailing her goal to publish an essay on Black experiences in the Americas with the Atlanta-based think tank Institute of the Black World (IBW).[2] The following year, Wynter submitted a draft of the essay which was then titled New Natives in a New World: The African Transformation in the Americas to be reviewed by the IBW.[3] Wynter wrote that her intention was to explore the Minstrel show as the first Native North American theater—and why Amerika distorted it; why a process of genuine creativity became a process of imitation and degenerated into a power stereotype, a cultural weapon against its creators. I shall relate the Minstrel show to the nineteenth century folk theatre patterns of the Caribbean and Latin America trying to link it to certain archetypal patterns of theater that we find for example among the Yoruba, the Aztecs and the folk English; and the way in which the blacks created a matrix to fuse disparate and yet archetypically related patterns.[1][2] Correspondence between Wynter and IBW over the course of the years does not reveal when the essay was to be expanded to a monograph. In 1976, there was significant mail correspondence between Wynter and the IBW in which she believed she could complete the manuscript during that year.[1] Between 1977 and 1982, Wynter began working closely with the Center for Afro-American Studies (CAAS) at UCLA to complete and publish the manuscript.[3] CAAS at the time focused on supporting both financially and editorially faculty and graduate students in their scholarly work within Black Studies. CAAS had a publishing contract with IBW and worked closely with Wynter to revise the manuscript.[3] Pierre-Michel Fontaine, a lecturer in the Afro-American studies department at Harvard at the time, sent a letter regarding the state of the manuscript to Robert A. Hill in 1978 when supervision over the manuscript was transferred to Hill. At that time, the manuscript was 250 pages long with missing footnotes and an unclear ending.[3] By the end of 1978, the publishing committee at CAAS relayed to Wynter that significant revisions were needed including correcting citations and clarifying footnotes. From 1980 to 1981, significant correspondence between Wynter and CAAS indicates the manuscript grew in length and underwent a title change. At that time, Wynter used the working title After the Passage: Culture and the Politics of Black Identity in the Americas. With her role as chair of the department of African and Afro-American studies at the time, Wynter relayed in letters both her busy schedule and continued intention to publish the manuscript.[3] By March 1982, Wynter was no longer engaged in administrative duties and the hope was that she would return to working on the manuscript. A memo from that date is the last document from CAAS covering work on the manuscript.[3] |

背景 1971年、ウィンターはカリブ海で開催された英連邦文学言語研究協会(ACLALS)の会議に出席した。そこで彼女はアフリカ系アメリカ人歴史家ヴィン セント・ハーディングと出会い、アトランタに拠点を置くシンクタンク「黒人世界研究所(IBW)」で、アメリカ大陸における黒人の経験に関する論文を発表 したいという目標を記した手紙を彼に送った[2]。翌年、ウィンターは当時『新世界の新住民:アメリカ大陸におけるアフリカの変容』と題された論文の草稿 をIBWに審査のために提出した。[3] ウィンターは自身の意図をこう記した。 ミンストレル・ショーを最初の北米先住民劇場として探求すること――そしてなぜアメリカがそれを歪めたのか。なぜ真の創造のプロセスが模倣のプロセスへと 変質し、権力による固定観念へと堕し、その創造者たちに対する文化的武器となったのか。私はミンストレル・ショーを、カリブ海やラテンアメリカの19世紀 民俗劇場の様式と関連づけ、例えばヨルバ族、アステカ族、英国の民俗劇に見られる特定の原型的劇場様式との接点を模索する。そして黒人たちが、異質であり ながら原型的に関連する様式の融合基盤をいかに創出したかを論じるつもりだ。[1][2] ウィンターとIBWの間の長年にわたる書簡のやり取りからは、このエッセイがいつ単行本に拡張される予定だったかは明らかではない。1976年にはウィンターとIBWの間で重要な書簡のやり取りがあり、彼女はその年中に原稿を完成させられると考えていた。[1] 1977年から1982年にかけ、ウィンターはUCLAのアフロ・アメリカン研究センター(CAAS)と緊密に連携し、原稿の完成と出版に着手した。 [3] 当時のCAASは、ブラック・スタディーズ分野における教員や大学院生の学術研究を、財政的・編集的に支援することに重点を置いていた。CAASはIBW と出版契約を結んでおり、ウィンターと緊密に連携して原稿の改訂を進めた。[3] 1978年、原稿の監修責任がロバート・A・ヒルに移管された際、当時ハーバード大学アフリカ系アメリカ人研究学科の講師であったピエール=ミシェル・ フォンテーヌが、原稿の状況についてヒル宛てに書簡を送付した。当時、原稿は250ページに及び、脚注が欠落し、結末も不明確な状態であった。[3] 1978年末までに、CAASの出版委員会はウィンターに対し、引用修正や脚注の明確化を含む大幅な改訂が必要だと伝えた。 1980年から1981年にかけて、ウィンターとCAASの間で交わされた重要な書簡から、原稿が長くなりタイトル変更が行われたことがわかる。当時ウィ ンターは仮タイトルとして『通過の後に:アメリカ大陸における黒人アイデンティティの文化と政治』を使用していた。当時アフリカ・アフリカ系アメリカ人研 究学科の学科長を務めていたウィンターは、書簡の中で多忙なスケジュールと原稿出版への継続的な意思を伝えている[3]。1982年3月までにウィンター は管理業務から離れ、原稿執筆に戻ることを期待されていた。この日付のメモが、CAASによる原稿作業に関する最後の文書である[3]。 |

| Overview Black Metamorphosis explores the historical significance of Black cultural resistance in the world through an interdisciplinary approach. From highlighting Jonkonnu in Jamaica and exploring her intellectual shift from Marxism, the work covers a variety of topics. Wynter asserts that Black cultural resistance pushed back against the notion of Black cultural inferiority. Wynter further argues that European intellectuals "proved" both Black and Indigenous cultural inferiority in order to justify economic exploitation and displacement.[4] The entire text and related correspondence is housed in the Institute of the Black World papers at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York.[2] |

概要 『ブラック・メタモルフォーゼス』は学際的アプローチを通じて、世界の黒人文化抵抗運動の歴史的意義を探求する。ジャマイカのジョンコンヌを強調し、マル クス主義からの知的転換を考察するなど、多様な主題を扱う。ウィンターは、黒人文化抵抗運動が黒人文化の劣等性という概念に反撃したと主張する。さらに彼 女は、ヨーロッパの知識人たちが経済的搾取と追放を正当化するため、黒人と先住民の文化の劣等性を「証明」したと論じる。[4] 本文及び関連書簡の全ては、ニューヨークのショーンバーグ黒人文化研究センター所蔵「黒人世界研究所文書」に収められている。[2] |

| 1.

White, Derrick (2010). "Black Metamorphosis: A Prelude to Sylvia

Wynter's Theory of the Human". The CLR James Journal. 16 (1): 127–148.

doi:10.5840/clrjames20101619. ISSN 2167-4256. JSTOR 26758878. 2. Kamugisha, Aaron (2016-03-01). ""That Area of Experience That We Term the New World": Introducing Sylvia Wynter's "Black Metamorphosis"". Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism. 20 (1 (49)): 37–46. doi:10.1215/07990537-3481522. ISSN 0799-0537. 3. "Finding Aid for the Center for African American Studies. Administrative files. 1941; 1969-1990". oac.cdlib.org. Retrieved 2020-02-05. 4. Kamugisha, Aaron (2016-03-01). "The Black Experience of New World Coloniality". Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism. 20 (1 (49)): 129–145. doi:10.1215/07990537-3481414. ISSN 0799-0537. |

1.

ホワイト、デリック(2010)。「黒の変容:シルヴィア・ウィンターの『人間』理論への序曲」。『CLRジェームズ・ジャーナル』。16(1):

127–148。doi:10.5840/clrjames20101619。ISSN 2167-4256。JSTOR 26758878. 2. カムギシャ、アーロン(2016-03-01)。「我々が新世界と呼ぶ経験の領域:シルビア・ウィンターの『ブラック・メタモルフォーゼ』を紹介する」。 『スモール・アックス:カリブ批評ジャーナル』。20巻1号(49号):37–46頁。doi:10.1215/07990537-3481522. ISSN 0799-0537. 3. 「アフリカ系アメリカ人研究センター所蔵資料目録。行政文書。1941年; 1969-1990年」. oac.cdlib.org. 2020年2月5日取得. 4. カムギシャ、アーロン (2016-03-01). 「新世界における植民地性の黒人体験」. 『スモール・アックス:カリブ批評ジャーナル』. 20 (1 (49)): 129–145. doi:10.1215/07990537-3481414. ISSN 0799-0537. |

| Sources Aaron Kamugisha, "That Area of Experience That We Term the New World": Introducing Sylvia Wynter's "Black Metamorphosis". Small Axe 49 (2016): 37-46 Aaron Kamugisha, "The Black Experience of New World Coloniality". Small Axe 49 (2016): 129-145 Derrick White. “Black Metamorphosis: A Prelude to Sylvia Wynter’s Theory of the Human.” The C.L.R. James Journal 16.1 (2010): 127–48. Finding Aid for the Center for African American Studies. Administrative files. 1941; 1969–1990; Box 4, Folder: Sylvia Wynter 1977-1982 |

出典 アーロン・カムギシャ「我々が新世界と呼ぶ経験の領域」:シルビア・ウィンターの『ブラック・メタモルフォーシス』を紹介する。『スモール・アックス』49号(2016年):37-46頁 アーロン・カムギシャ「新世界植民地性における黒人の経験」。『スモール・アックス』49号(2016年):129-145頁 デリック・ホワイト「ブラック・メタモルフォーゼ:シルヴィア・ウィンターの『人間の理論』への序曲」『C.L.R. ジェームズ・ジャーナル』16.1号(2010年):127–48頁 アフリカ系アメリカ人研究センター資料目録。管理ファイル。1941年; 1969–1990年; 箱4、フォルダ:シルビア・ウィンター 1977-1982 |

| Further reading Demetrius L. Eudell, "From Mode of Production to Mode of Auto-Institution: Sylvia Wynter's Black Metamorphosis of the Labor Question". Small Axe. 49 (Mar 2016): 47–61. Greg Thomas, "Marronnons / Let's Maroon: Sylvia Wynter's Black Metamorphosis as a Species of Maroonage". Small Axe 49 (Mar 2016): 62–78. Katherine McKittrick, "Rebellion/Invention/Groove". Small Axe 49 (2016): 79-91 Nijah Cunningham, "The Resistance of the Lost Body". Small Axe 49 (2016): 113-128 |

追加文献(さらに読む) デメトリウス・L・ユーデル「生産様式から自律的制度化様式へ:シルヴィア・ウィンターの労働問題における黒人変容論」『スモール・アックス』49号(2016年3月):47–61頁。 グレッグ・トーマス「マローン/マローンになろう:シルヴィア・ウィンターの『労働問題の黒人変容』をマローン運動の一形態として」『スモール・アックス』49号(2016年3月):62–78頁。 キャサリン・マッキトリック「反逆/発明/グルーヴ」『スモール・アックス』49号(2016年):79-91 ニジャ・カニンガム「失われた身体の抵抗」『スモール・アックス』49号(2016年):113-128 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Metamorphosis |

★Sylvia Wynter の overrepresentation of Man とは?

| Okay, the user is

asking about Sylvia Wynter's concept of the "overrepresentation of

Man." I need to explain this clearly. Let me start by recalling what I

know about Wynter's work. She's a Jamaican scholar who critiques

Western humanism. The term "overrepresentation of Man" refers to how

Western colonial and capitalist ideologies have centered a specific,

narrow version of humanity (white, male, European) as the universal

standard. This marginalizes other groups and ways of being. I should break down the key points. First, explain what "Man" means in this context—not just males but the Western bourgeois ideal. Then, how this overrepresentation leads to exclusion of other identities. Maybe mention how Wynter ties this to colonialism and racism. Also, her critique of the Enlightenment's humanism, which she argues is exclusionary. It's important to connect this to her broader project of redefining the human beyond Western norms. Perhaps include examples like the dehumanization of enslaved Africans or indigenous peoples. Also, her call for new narratives that include diverse epistemologies. I need to make sure the explanation is accessible, avoiding too much jargon. Check if there are any related concepts, like Fanon's influence on her work. Make sure to structure the answer logically, starting with a definition, then historical context, implications, and her proposed solutions. Avoid making it too dense; use clear examples. Double-check that I'm not conflating her ideas with similar theorists. Maybe mention how this overrepresentation is maintained through institutions and knowledge production. Conclude with the significance of her work in contemporary discussions on decolonization and social. よし、ユーザーはシルビア・ウィンターの「人間の過剰表現」という概念について尋ねている。これを明確に説明する必要がある。まず、ウィンターの研究につ いて私が知っていることを振り返ろう。彼女はジャマイカ出身の学者で、西洋ヒューマニズムを批判している。「人間の過剰表現」という用語は、西洋の植民地 主義と資本主義のイデオロギーが、特定かつ狭義の人間像(白人、男性、ヨーロッパ人)を普遍的な基準として中心に据えてきたことを指す。これは他の集団や 存在の仕方を周縁化する。 要点を分解する必要がある。まず、この文脈における「人間」の意味を説明すること——単なる男性ではなく、西洋ブルジョワの理想像を指す。次に、この過剰 表現が他のアイデンティティの排除をどう招くか。ウィンターがこれを植民地主義や人種主義とどう結びつけるかにも触れるべきだろう。また、啓蒙主義的人間 観に対する彼女の批判——排他的だと主張する点も重要だ。これを、西洋規範を超えた人間の再定義という彼女の広範なプロジェクトと結びつけることが肝要で ある。奴隷化されたアフリカ人や先住民の人間性否定といった具体例を挙げるのもよい。多様な認識論を含む新たな物語の構築を彼女が提唱している点も触れる べきだ。専門用語を避け、説明を分かりやすくする必要がある。ファノンが彼女の思想に影響を与えたかなど、関連概念の有無を確認せよ。定義→歴史的背景→ 影響→解決策という論理的な構成を心がけること。内容が凝縮しすぎないように、明確な例を用いて説明すること。類似理論家との混同がないか再確認するこ と。制度や知識生産を通じてこの過剰表現が維持される仕組みにも言及するとよい。現代の脱植民地化や社会運動における彼女の研究の意義で結論づけること。 |

|

| 1. 「Man」の脱神話化 Man=西洋ブルジョワ的人間像 16世紀以降の植民地主義と資本主義が生んだ「白人性・男性性・合理主義」を規範とする人間観 キリスト教的「アダム=人類の原型」という神話を世俗化し、生物学的決定論と進化論を組み合わせた新たな人種階層秩序を構築 |

|

| 2. 過剰表象のメカニズム 認識論的暴力: 「知の制度」→人種/ジェンダー/階級のヒエラルキー 大学・博物館・法制度が「Man」を唯一の普遍的人間像として再生産 美的排除: アフリカ系の身体を「原始的」と表象する視覚文化(19世紀の人類学展示など)が、人間性の境界線を再定義 経済的基盤: 奴隷制プランテーション経済が「労働する動物(Negro)」という新たな人間カテゴリーを必要とした |

|

| 3. 具体的歴史事例 1492年の断層:コロンブスの「新大陸」到達が、キリスト教徒/異教徒の二分法を「文明人/野蛮人」に転換 黒人奴隷の法的地位:1705年バージニア法が「キリスト教徒である白人のみ完全な人間」と規定 精神病の診断:19世紀の逃亡奴隷を「drapetomania(逃亡病)」と病理化した医学言説 |

|

| 4. 脱植民地化の戦略 Wynterが提唱する「新しい人間の物語」の要件: 認識論的多様性:アフリカ系ディアスポラの知(ジャマイカのナイヤビンギ儀礼など)を正当化 制度の再発明:大学を「人間性の工房」から「多種的人間性の実験場」へ転換 美的革命:カリブ海文学(Wilson Harrisなど)にみる「未完の物語性」を政治実践に接合 |

|

| 5. 現代への含意 AI倫理:アルゴリズムに埋め込まれた「Man」の認識枠組みが再生産する排除 気候変動:人間/自然の二分法を超える「地球的共生(planetary symbiosis)」の可能性 Black Lives Matter:警察暴力を「人間性の境界を巡る闘争」として再解釈する視座 |

|

| Wynterの理論は、単なる文化相対主義を超え、500年にわたる西洋近代の認識論的基盤そのものへの挑戦を意味する。その射程は哲学・人類学・文学研究を横断し、現代の脱植民地化運動に新たな理論的武器を提供している。 |

|

| Google generative AI - Monica. |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099