カソリック教会におけるセックスとジェンダー役割

Sex and gender roles in the Catholic Church

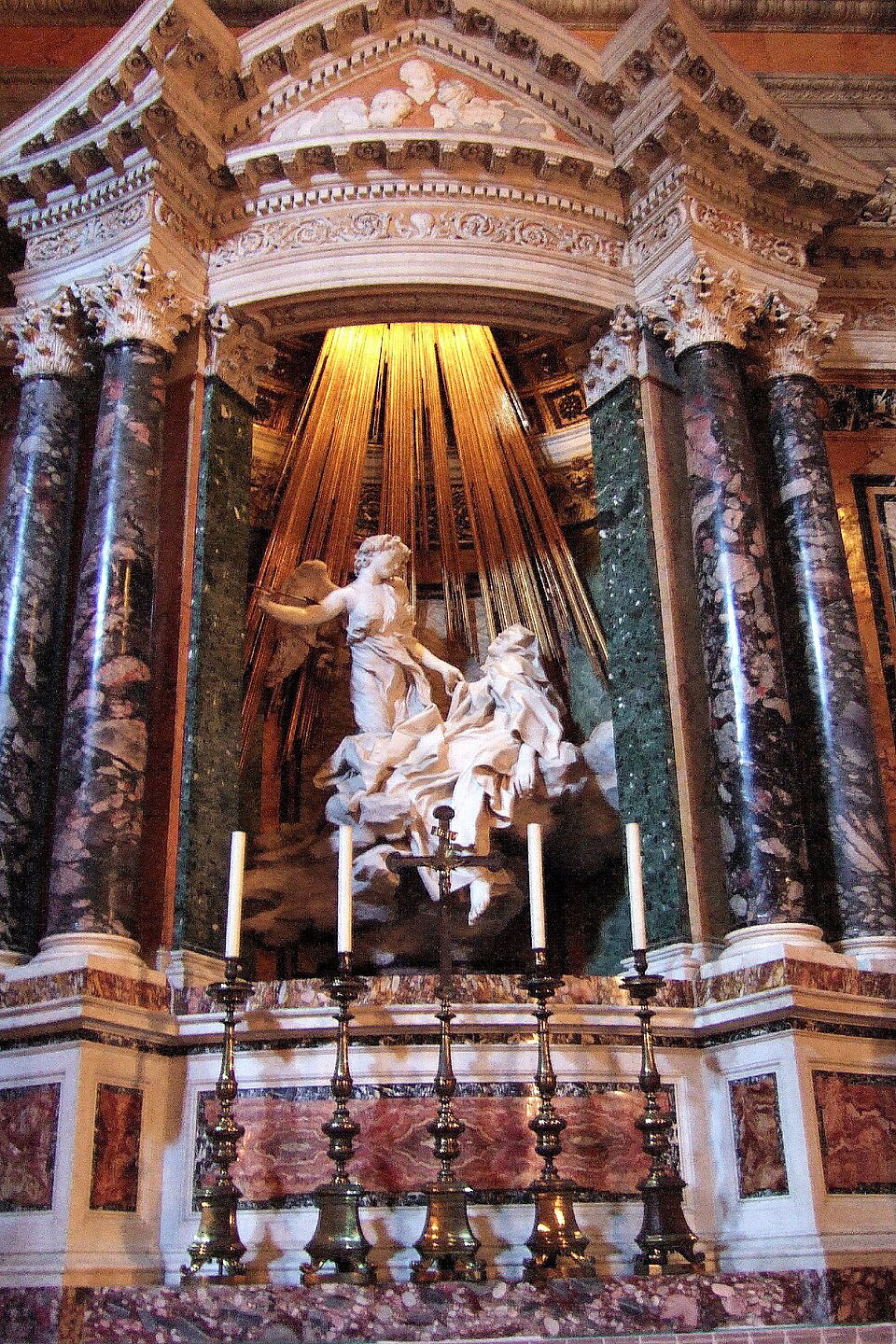

Matrimony,

The Seven Sacraments, Rogier van der Weyden, c. 1445.

☆

ローマ・カトリック教会における性とジェンダー役割は、教会の歴史を通じて陰謀と論争の両方の対象となってきた。カトリック教会の文化的影響力は広大であ

り、特に西洋社会に対して顕著であった[2]。教会によって世界中の伝道社会に導入されたキリスト教の概念は、確立された性の観念やジェンダー役割に対す

る文化的見解に重大な影響を与えた。ローマ帝国、ヨーロッパ、ラテンアメリカ、アフリカの一部地域[3][4][5][6][7]などの文化で実践されて

いた人身供犠、奴隷制、幼児殺害、一夫多妻制は、教会の布教活動によって終焉を迎えた。歴史家たちは、カトリックの宣教師、教皇、修道者たちが奴隷制反対

運動の指導者であったと指摘する。奴隷制はほぼ全ての文化に存在し[8][9][10]、しばしば女性の性的奴隷化を伴っていた。キリスト教はローマ帝国

のような布教された文化圏において、幼児殺害(女児殺害がより一般的であった)、離婚、近親相姦、一夫多妻制、男女双方の婚姻不貞を非難することで女性の

地位に影響を与えた。[3][4][11]

一部の批判者は、教会や聖パウロ、教父たち、スコラ神学者の教えが、女性の劣等性は神によって定められたという観念を永続させたと主張する[12]。一

方、現在の教会の教え[13]は、女性と男性は平等であり、異なる存在であり、互いに補完し合うと考える。

これらの文化における性的慣行は、キリスト教の男女平等という概念の影響を受けた。教会によれば、性行為は結婚関係という文脈において神聖であり、それは

男女の完全かつ生涯にわたる相互の献身を反映するものである。[14]

これはキリスト教到来以前の文化に普遍的であった一夫多妻制や妾制度を排除するものである。男女の平等性は、神聖な設計により両性が異なる存在として意図

され、それぞれが等しい尊厳を持ち神の像として造られたという教会の教えに反映されている。[15]

| Sex and gender roles

in the Roman Catholic Church have been the subject of both intrigue and

controversy throughout the Church's history. The cultural influence of

the Catholic Church has been vast, particularly upon Western

society.[2] Christian concepts, introduced into evangelized societies

worldwide by the Church, had a significant impact on established

cultural views of sex and gender roles. Human sacrifice, slavery,

infanticide and polygamy practiced by cultures such as those of the

Roman Empire, Europe, Latin America and parts of Africa[3][4][5][6][7]

came to an end through Church evangelization efforts. Historians note

that Catholic missionaries, popes and religious were among the leaders

in campaigns against slavery, an institution that has existed in almost

every culture[8][9][10] and often included sexual slavery of women.

Christianity affected the status of women in evangelized cultures like

the Roman Empire by condemning infanticide (female infanticide was more

common), divorce, incest, polygamy and marital infidelity of both men

and women.[3][4][11] Some critics say the Church and teachings by St.

Paul, the Church Fathers, and scholastic theologians perpetuated a

notion that female inferiority was divinely ordained,[12] while current

Church teaching[13] considers women and men to be equal, different, and

complementary. Sexual practices of these cultures were affected by the Christian concept of male, female equality. The sexual act, according to the Church, is sacred within the context of the marital relationship that reflects a complete and lifelong mutual gift of a man and a woman. [14] One that precludes the polygamy and concubinage common to cultures before the arrival of Christianity. The equality of men and women is reflected in the Church teaching that the sexes are meant by divine design to be different and complementary, each having equal dignity and made in the image of God.[15] |

ローマ・カトリック教会における性とジェンダー役割は、教会の歴史を通

じて陰謀と論争の両方の対象となってきた。カトリック教会の文化的影響力は広大であり、特に西洋社会に対して顕著であった[2]。教会によって世界中の伝

道社会に導入されたキリスト教の概念は、確立された性の観念やジェンダー役割に対する文化的見解に重大な影響を与えた。ローマ帝国、ヨーロッパ、ラテンア

メリカ、アフリカの一部地域[3][4][5][6][7]などの文化で実践されていた人身供犠、奴隷制、幼児殺害、一夫多妻制は、教会の布教活動によっ

て終焉を迎えた。歴史家たちは、カトリックの宣教師、教皇、修道者たちが奴隷制反対運動の指導者であったと指摘する。奴隷制はほぼ全ての文化に存在し

[8][9][10]、しばしば女性の性的奴隷化を伴っていた。キリスト教はローマ帝国のような布教された文化圏において、幼児殺害(女児殺害がより一般

的であった)、離婚、近親相姦、一夫多妻制、男女双方の婚姻不貞を非難することで女性の地位に影響を与えた。[3][4][11]

一部の批判者は、教会や聖パウロ、教父たち、スコラ神学者の教えが、女性の劣等性は神によって定められたという観念を永続させたと主張する[12]。一

方、現在の教会の教え[13]は、女性と男性は平等であり、異なる存在であり、互いに補完し合うと考える。 これらの文化における性的慣行は、キリスト教の男女平等という概念の影響を受けた。教会によれば、性行為は結婚関係という文脈において神聖であり、それは 男女の完全かつ生涯にわたる相互の献身を反映するものである。[14] これはキリスト教到来以前の文化に普遍的であった一夫多妻制や妾制度を排除するものである。男女の平等性は、神聖な設計により両性が異なる存在として意図 され、それぞれが等しい尊厳を持ち神の像として造られたという教会の教えに反映されている。[15] |

| Historical overview Roman Empire Social structures at the dawn of Christianity in the Roman Empire held that women were inferior to men intellectually and physically and were "naturally dependent".[4] Athenian women were legally classified as children regardless of age and were the "legal property of some man at all stages in her life."[11] Women in the Roman Empire had limited legal rights and could not enter professions. Female infanticide and abortion were practiced by all classes.[11] In family life, men, not women, could have "lovers, prostitutes and concubines" and it was not rare for pagan women to be married before the age of puberty and then forced to consummate the marriage with her often much older husband. Husbands, not wives, could divorce at any time simply by telling the wife to leave. The spread of Christianity changed women's lives in many ways by requiring a man to have only one wife and keep her for life, condemning the infidelity of men as well as women and doing away with marriage of prepubescent girls.[4] Because Christianity outlawed infanticide and because women were more likely than men to convert, there were soon more Christian women than men whereas the opposite was true among pagans.[11] |

歴史的概観 ローマ帝国 キリスト教がローマ帝国に広まり始めた頃の社会構造では、女性は知力・体力ともに男性より劣り、「生まれながらに依存的」とされていた。[4] アテネの女性は年齢に関わらず法的に子供と分類され、「生涯を通じて常に何らかの男性の法的所有物」であった。[11] ローマ帝国の女性は法的権利が制限され、職業に就くこともできなかった。女児殺しと中絶は全階級で実践されていた。[11] 家庭生活において、男性は女性とは異なり「愛人、娼婦、妾」を持つことが許され、異教徒の女性が思春期前に結婚させられ、しばしば年上の夫との婚姻を強制 されることも珍しくなかった。離婚は妻ではなく夫が、単に妻に出て行けと告げるだけでいつでも可能であった。キリスト教の普及は女性の生活に多大な変化を もたらした。男性は一人の妻のみを娶り生涯を共にすべきと定め、男女双方の不貞を非難し、思春期前の少女との結婚を禁止したのだ[4]。キリスト教が嬰児 殺しを禁じたこと、また女性が男性より改宗しやすい性質から、間もなくキリスト教徒の女性は男性を上回った。これに対し異教徒社会では逆の現象が見られた [11]。 |

| Europe Middle Ages The church defined sin as a violation of any law of God, the Bible, or the church.[16] Common sexual sins were premarital sex, adultery, masturbation, homosexuality, and bestiality. Many influential members of the church saw sex and other pleasurable experiences as evil and a source of sin when in the wrong context, unless meant for procreation.[17] Also, any non-vaginal sex (oral, manual, anal) is sinful. The church considered masturbation a sin against nature because the guilty party was extracting sexual pleasure outside of the context of proper use. Also, law required clerics to avoid any sort of sexually tinged entertainment.[18] However, canon law did allow sex in a marriage, as long as it intended to procreate and not just provide pleasure, even though some saw sex, even in marriage, as sinful and impure.[19] Jeffrey Richards describes a European "medieval masculinity which was essentially Christian and chivalric".[20] Sexual regulation by the church accounted for a great amount of literature and time. The church saw regulation as necessary to maintain the welfare of society.[21] Canon law banned premarital sex, lust, masturbation, adultery, bestiality, homosexuality, and any sort of sex outside of marriage. Adultery was broken up into various categories by the Statutes of Angers: prostitution and simple fornication, adultery, defloration of virgins, intercourse with nuns, incest, homosexuality, and incidental matters relating to sex such as looks, desires, touches, embraces, and kisses.[22] Adultery was typically grounds for divorce for a man if his wife fornicated with another, but adultery was not seen as a crime, just as a sin.[23] Prostitution, although within the category of fornication, was less concrete in the law. Because the medieval canon law originated as an "offshoot of moral theology" but also drew from Roman law, it contributed both legal and moral concepts to canonistic writing.[24] This split influence caused the treatment of prostitution to be more complex. Prostitution, although sinful, was tolerated. Without the availability of a prostitute, men could be led to defloration of a virgin. It was better to tolerate prostitution with all of its associated evils, than to risk the perils which would follow the successful elimination of the harlot from society.[25] The church recognized disordered sexual desire as a natural inclination related to original sin, so sexual desires could not be ignored as a reality. Although the law attempted to strictly regulate prostitution, whorehouses abounded disguised as bathhouses or operated in secret within hotels and private residences. "Outside the official public brothels, prostitution in the public bathhouses, the inns and the taverns was common knowledge and was tolerated.[26] Much of the church's efforts were put toward controlling what was going on sexually in a marriage, especially regarding when a married couple could have sex. Sex was not allowed during pregnancy or menstruation, right after a child birth, on Sunday, Wednesday, Friday, or Saturday during each of the three Lents, on feast days, quarterly ember days, or before communion.[27] The church also denounced "unnatural" sexual relations between those of the same sex and also married couples.[28] Also, upon marrying, a couple could not enter a church for thirty days.[29] Although the church developed very strict regulations on sexual activity that needed to be carried out to sustain the institutional and psychological structure of the Middle Ages, it had a hard time properly enforcing these regulations. Most violations occurred in the privacy of the bedroom, so the only witnesses to the sin were the guilty parties themselves, and they did not usually confess to such crimes. Also, the problem was widespread. Not only did the common people deviate from the rules, but the clerics themselves did not follow their own laws.[30] In order to convict, accusation was required, and people did not usually have enough proof to back up an accusation, as law basically required a confession, and there was always a chance that if there was not enough proof, the accuser would be charged with false accusations. Even though the system was not foolproof, the church did produce a large number of institutions to inform the public of the law of sexual practice, and also had an extensive system of courts to deal with sexual misbehavior.[31] Sexual offenses were punished in a variety of ways during the Middle Ages.[32] There were numerous prosecutions for adultery, fornication, and other sexual offenses,[33] but fornication was the most frequently prosecuted.[34] Fornication was seen as a serious sin and a canonical crime[35] and those convicted were required to "pay fines and court costs",[36] and they were often subject to public humiliation. Public humiliation ranged from public confessions and requesting the forgiveness of the community (often by kneeling at the entrance of a church and begging those who entered for mercy),[34] to public whippings in the churchyard or marketplace,[37] to being paraded around the church "bare-chested and bearing a lighted candle before Sunday Mass".[38] Some offenders were made to wear special clothes while others were flogged. Numerous offenders had to fast or abstain from meat, wine, and sex for a set period of time.[39] Other "punishments [ranged] from the cutting off of hair and pillory to prison and expulsion."[40] Those convicted of more serious sexual offenses were subject to removal from office, confinement in a monastery, or a forced pilgrimage. Not all punishments were equal; punishments for sexual crimes differed between genders and social classes. When convicted of adultery, it was more likely that males would be fined in church courts rather than publicly flogged like the convicted females.[41] However, when the males began to be more strictly punished, the punishment for females also became more severe. While males were now publicly whipped, females had their heads shaved[42] and were subject to expulsion from their homes, separation from their children, and the confiscation of their dowry. The wounds of the male would heal over time, but the woman was reduced to "penury".[43] She would often be forced to live in poverty for the remainder of her life. In one case, a woman was accused of sleeping around and was ordered to rid herself of guilt in front of seven witnesses. Her male counterpart, however, was subject to no punishment whatsoever. When a woman of a higher social status was convicted of the same crime, she was not required to purge herself of her guilt in front of any witnesses. The woman of a higher social class was allowed to repent in private. Common prostitutes of the time period were banned from churches, but there was little to no prosecution of their "male clientele".[44] However, the priests of the higher classes were punished most severely for sexual crimes. They were stripped of their rank, position, and income.[45] The wife and children of the priest were thrown out of their house,[46] and the priests could be thrown in a monastery for the remainder of their lives and their wife and children enslaved.[34] |

ヨーロッパ 中世 教会は罪を、神の掟、聖書、あるいは教会の掟に対する違反と定義した。[16] 一般的な性的罪には、婚前交渉、姦淫、自慰行為、同性愛、獣姦が含まれた。教会の有力な多くのメンバーは、生殖を目的としない限り、性行為やその他の快楽 体験は、不適切な状況下では悪であり罪の根源であると見なした[17]。また、膣以外の性行為(オーラル、マスターベーション、アナル)は全て罪深いとさ れた。教会はマスターベーションを自然に対する罪とみなした。なぜなら、罪を犯した者は適切な使用の文脈外で性的快楽を得ていたからである。また、聖職者 はあらゆる性的要素を含む娯楽を避けるよう法で義務付けられていた[18]。ただし教会法は、単なる快楽ではなく子孫繁栄を目的とする限り、婚姻内での性 行為を認めていた。とはいえ婚姻内での性行為さえ罪深く不浄と見なす者もいた[19]。ジェフリー・リチャーズは、ヨーロッパの「中世の男らしさ」を「本 質的にキリスト教的かつ騎士道的なもの」と描写している。[20] 教会による性規制は膨大な文献と時間を費やした。教会は社会秩序維持に規制が不可欠と考えた。[21]教会法は婚前性行為、情欲、自慰、姦通、獣姦、同性 愛、婚姻外のあらゆる性行為を禁じた。アンジェ法令は姦通を細分化した:売春と単純な淫行、姦通、処女の処女喪失、修道女との性交、近親相姦、同性愛、そ して視線・欲望・接触・抱擁・接吻といった性に関連する偶発的事項である。[22] 妻が他人と姦淫した場合、夫にとって姦淫は通常離婚の理由となったが、姦淫自体は犯罪とは見なされず、単なる罪とされた。[23] 売春は姦淫の範疇に含まれつつも、法的にはより曖昧な扱いを受けた。中世教会法は「道徳神学の派生」として起源を持ちつつもローマ法からも影響を受けたた め、教会法文献には法的概念と道徳的概念の両方が混在していたのである。[24] この二つの影響が入り混じったため、売春の扱いはより複雑になった。売春は罪深い行為でありながら、容認されていた。売春婦が利用できない状況では、男性 が処女の処女を奪う可能性があった。売春婦を社会から完全に消去法による排除の際に生じる危険を冒すよりは、売春に伴うあらゆる悪を容認する方がましだと 考えられたのだ。[25] 教会は乱れた性的欲求を原罪に関連する自然な傾向と認め、性的欲求を現実として無視することはできなかった。法律は売春を厳しく規制しようとしたが、風呂 屋を装った売春宿や、ホテルや私邸内で密かに営業する売春宿が蔓延した。公認の売春宿以外では、公衆浴場や宿屋、酒場での売春は周知の事実であり、黙認さ れていた。[26] 教会の努力の多くは、婚姻関係における性行為、特に夫婦がいつ性交できるかを管理することに注がれた。妊娠中や月経中、出産直後、日曜日、水曜日、金曜 日、三つの四旬節期間中の土曜日、祝祭日、四半期ごとの灰の水曜日、聖体拝領前には性行為が禁じられていた[27]。教会は同性間の「不自然な」性関係や 夫婦間のそれをも非難した[28]。また結婚後30日間は教会に入ることが許されなかった。[29] 教会は中世の制度的・心理的構造を維持するために、性行為に関する非常に厳しい規制を発展させたが、これらの規制を適切に施行するのは困難だった。違反の 大半は寝室の私的な空間で発生したため、罪の証人は当事者自身のみであり、彼らは通常、そのような罪を告白しなかった。さらに問題は広範だった。庶民が規 則から逸脱しただけでなく、聖職者自身も自らの律法を守らなかったのだ。[30] 有罪判決には告発が必要だったが、人々は通常、告発を裏付ける十分な証拠を持っていなかった。法律は基本的に自白を要求し、証拠が不十分な場合、告発者が 虚偽の告発で訴追される可能性が常にあったからだ。この制度は完璧ではなかったが、教会は性行為に関する法律を民衆に周知するための多くの機関を設立し、 性的不品行に対処する広範な裁判制度も備えていた。[31] 中世において性的犯罪は様々な方法で処罰された。[32] 姦通、淫行その他の性犯罪に対する訴追は数多くあったが[33]、最も頻繁に訴追されたのは淫行であった[34]。淫行は重大な罪であり教会法上の犯罪と 見なされ[35]、有罪判決を受けた者は「罰金と裁判費用を支払う」ことを義務付けられ[36]、しばしば公の恥辱に晒された。公の恥辱には、公の告白や 共同体への赦しを請う行為(多くの場合、教会の入口でひざまずき、入ってくる者に慈悲を乞うこと)[34]から、教会の庭や市場での公開鞭打ち[37]、 日曜日のミサ前に「裸の胸で火のついたろうそくを掲げて教会内を練り歩く」こと[38]まで様々であった。一部の犯罪者は特別な服を着せられ、他の者は鞭 打ちの刑に処された。多くの罪人は一定期間、断食や肉・酒・性行為の禁欲を強いられた[39]。その他の「刑罰は髪を切る刑や檻刑から投獄や追放まで様々 だった」[40]。より深刻な性犯罪で有罪となった者は、職位剥奪、修道院への幽閉、あるいは強制巡礼の対象となった。 全ての刑罰が平等だったわけではない。性犯罪に対する処罰はジェンダーや社会階級によって異なる。姦通罪で有罪となった場合、男性は教会法廷で罰金を科さ れることが多く、有罪となった女性のように公の場で鞭打ち刑に処されることは稀であった[41]。しかし、男性への処罰が厳しくなるにつれ、女性への処罰 もより重くなった。男性が公の場で鞭打ち刑に処されるようになった一方で、女性は頭を剃られ[42]、家からの追放、子供との引き離し、持参金の没収と いった処罰を受けた。男性の傷は時と共に癒えるが、女性は「貧困状態」に追い込まれた[43]。残りの人生を貧困の中で過ごすことを強いられることが多 かった。ある事例では、女性が不貞行為を告発され、七人の証人の前で罪を清めるよう命じられた。しかし、男性の相手方は一切の罰を受けなかった。一方、高 位の女性が同じ罪で有罪となっても、証人の前で罪を清める必要はなかった。高位の女性は私的に悔い改めることが許されていた。当時の娼婦は教会への立ち入 りを禁じられていたが、彼女たちの「男性客」に対する訴追はほとんど行われなかった。[44] しかし、高位の聖職者が性犯罪を犯した場合、最も厳しい処罰が下された。彼らは位階、地位、収入を剥奪された。[45] 聖職者の妻と子供は家から追い出され、[46] 聖職者自身は残りの生涯を修道院に閉じ込められ、妻と子供は奴隷にされた。[34] |

| Latin America It was women, primarily Amerindian Christian converts, who became the primary supporters of the Church.[6] Slavery and human sacrifice were both part of Latin American culture before the Europeans arrived.[47] Spanish conquerors enslaved and sexually abused Indian women on a regular basis.[48] Indian slavery was first abolished by Pope Paul III in the 1537 bull Sublimis Deus which confirmed that "their souls were as immortal as those of Europeans" and they should neither be robbed nor turned into slaves.[47][49][50] While the Spanish military was known for its ill-treatment of Amerindian men and women, Catholic missionaries are credited with championing all efforts to initiate protective laws for the Indians and fought against their enslavement.[51][52] The missionaries in Latin America felt that the Indians tolerated too much nudity and required them to wear clothes if they lived at the missions. Common Indian sexual practices such as premarital sex, adultery, polygamy, and incest were quickly deemed immoral by the missionaries and prohibited with mixed results. Indians who did not agree to these new rules either left the missions or actively rebelled. Women's roles were sometimes reduced to exclude tasks previously performed by women in religious ceremonies or society.[48] |

ラテンアメリカ 主にキリスト教に改宗したアメリカ先住民の女性たちが、教会の主要な支持者となった。[6] 奴隷制と人身供犠は、ヨーロッパ人が到着する前からラテンアメリカ文化の一部であった。[47] スペインの征服者たちは、定期的に先住民の女性を奴隷化し性的虐待を加えた。[48] 先住民奴隷制は、1537年の教皇パウロ3世の教書『Sublimis Deus』によって初めて廃止された。この教書は「彼らの魂はヨーロッパ人と同様に不滅である」と確認し、先住民を略奪したり奴隷にしたりしてはならない と定めた。[47][49][50] スペイン軍がアメリカ先住民の男女を虐待することで知られていた一方で、カトリック宣教師たちは先住民保護法の制定を主導し、奴隷化に反対した功績があ る。[51][52] ラテンアメリカの宣教師たちは、先住民が裸体を許容しすぎていると感じ、宣教地に住むなら衣服を着用するよう要求した。婚前交渉、姦通、重婚、近親相姦と いったインディアンの一般的な性慣行は、宣教師たちによって即座に不道徳と見なされ、禁止されたが、その効果は混血のであった。これらの新たな規則に同意 しないインディアンは、宣教地を去るか、積極的に反乱を起こした。女性の役割は時に縮小され、宗教儀式や社会において女性が従来担っていた任務から排除さ れることもあった。[48] |

| Africa By and large the largest obstacle to evangelization of Africans was the widespread nature of polygamy among the various populations. Africa was initially evangelized by Catholic monks of medieval Europe, and then by both Protestants and Catholics from the seventeenth century onward. Each of these evangelizing groups complained "incessantly" about African marriage customs.[53] Priestly celibacy is often reported as a problem in Africa today, where "large numbers of priests feel celibacy is simply incompatible with African culture."[54] "It is widely reported that priests routinely live double lives, keeping "secret" families in homes far from their parishes."[55][56] |

アフリカ 概して、アフリカ人への布教における最大の障害は、様々な民族間で広く行われていた一夫多妻制であった。アフリカは当初、中世ヨーロッパのカトリック修道 僧によって布教され、その後17世紀以降はプロテスタントとカトリックの両方によって布教が進められた。これらの伝道グループはいずれも、アフリカの結婚 習慣について「絶え間なく」不満を訴えた[53]。司祭の独身制は、今日のアフリカでも問題として頻繁に報告されており、「多くの司祭が独身制はアフリカ の文化と単純に相容れないと感じている」[54]。「司祭が日常的に二重生活を送っており、教区から遠く離れた家に『秘密の』家族を隠している」と広く報 じられている[55][56]。 |

| Mexico During the time Spain owned Mexico (pre-independence) Mexico adopted the style of Spain's Catholicism where women were normatively established as weak. "During the beginning of church history ecclesiastical authorities found in the creative fashioning of gendered language an important means by which to reaffirm the patriarchal norms that underlay the institution's power and authority".[57] In the case of the patriarchal system that developed over many centuries in the Church, normative definitions of masculinity and femininity took on added significance as guarantors of institutional stability which ensured the ongoing functioning of the institution, but, when contested or undermined, threatened the entire sacred enterprise.[57] Women were "excluded from the public sphere [of the church] and held in the private realm of home and family life"; "the Church, the school, and the family all converged in assigning women this role."[58] In Mexico during 1807, people "cited women's behavior as a root cause of social problems" and thought that it would lead to the break-down of New Spain.[57] In this time period women were inferior to men and the inequality of gender was used as a source of power in their sermons.[57] In colonial and early-independent Mexico, male archbishops would use language "that either explicitly invoked patriarchal social norms or creatively reinforced them through adaptations of tropes of masculinity and femininity".[57] Studies show how "the Church likewise played a role in shaping women's marriage choices, both through canonical rules of consanguinity among marriage partners and by means of the ostensible limits imposed by its expectation that marriage be contracted freely by both parties".[57] During the Cold War, the influence of communism "became a central political battle and a common cause for the Church and the Mexican Women".[58] Prior to the Cold War, women were confined to the private sphere in the homes of the family. "In the face of an alleged Communist ideological offensive, [this notion of women being confined to the private sphere] became an issue of public concern",[58] As a result, women "created new forms of political participation, and they acquired an unprecedented sense of political competence" as well as involvement in the church.[58] Women were "made aware of their own potential in the public sphere".[58] A common woman-figure in the Mexican Catholic Church was "derived from the position of the Virgin Mary, or from her more vernacular representation, the Virgin of Guadalupe."[58] The Virgin Mary was held as a "role model" for women and young girls and was distinguished for her "passivity, self-denial, abnegation and chastity."[58] The Church disseminated a religious, maternal, and spiritual role component of the Virgin Mary "that governed attitudes and symbols sustaining women's status."[58] Women of Nahua The indigenous Nahua women in colonial times were significantly noted for their lack of power and authority in their roles compared to men in the realm of the Catholic Church in Mexican society. It is seen that "Nahua women's religious responsibilities in Mexico City lay between the officially recognized positions of men in the public arena and women's private responsibilities in the home."[59] They were denied the officially sanctioned power that should have actually been offered to the Nahua women.[59] Their lack of authority resulted in occasional outbreaks in violence due to frustration. "In at least one-fourth of the cases, women led the attacks and were visibly more aggressive in their behavior toward outside authorities." And they were unable to become nuns in the Catholic Church society.[59] The women were only to "be recipients of God’s divine favor and protection if they followed the tenets of the Catholic Church"; the rules and regulations for women were evidently more strict and rigid than those for men.[59] Women of Vela Perpetua There is specific evidence for a woman-dominated, church-oriented organization called The Ladies of the Vela Perpetua. This "predominantly female lay organization whose central purpose is to keep vigil over the Blessed Sacrament overnight" was a unique because of "its implicit challenge to the Church's rigidly hierarchical gender ideology: the constitution of the Vela Perpetua mandated that women, and only women, were to serve as the officers of this mixed-sex, lay, devotional organization."[60] Scholars suspect that the woman-led organization "was predominately found in the small towns and cities of the central-western states of Guanajuato, Michoacán ́and Jalisco (a part of Mexico known as the Baj ́io)."[60] During this time, "female leadership meant something virtually unheard of in Catholic lay societies: women were in a position to 'govern men'."[60] Even though Vela Perpetua was founded in 1840, their reverse gender role legacy was neither celebrated nor recognized until much later in time. According to research form scholars, "We do not and cannot know for certain who first conceived the idea of the female-led Vela Perpetua."[60] However, it is known that this institution was composed of devout mothers, grandmothers and great-grandmothers alike.[60] These ladies brought a sense of "feminization" that they had been historically denied in the realm of the Catholic Church which surrounded their lives. Because the sense of social and religious freedom that was provided, others in surrounding communities "looked to the Vela as a way to support the Church and to claim a kind of religious citizenship – greater equality and greater power within the Church."[60] Some men were angered over these non-traditional church ways and "four years [after the Vela Perpetua was founded] the first separate Vela for men was founded."[60] Despite the creation of a separate Vela for men, "several of the women's Velas were singled out for praise by the bishop for their efficient organization."[60] |

メキシコ スペインがメキシコを支配していた時代(独立前)、メキシコはスペインのカトリック様式を採用した。そこでは女性が規範的に弱い存在として位置づけられて いた。「教会史の初期において、教会当局はジェンダーを区別する言語の創造的形成に、制度の権力と権威の基盤となる家父長制規範を再確認する重要な手段を 見出した」 [57] 教会で数世紀にわたり発展した家父長制において、男性性と女性性の規範的定義は、制度の安定を保証する要素として追加的な重要性を帯びた。これは制度の継 続的な機能を確保する一方で、異議を唱えられたり弱体化したりすると、神聖な事業全体を脅かすものとなった。[57] 女性は「(教会の)公共領域から排除され、家庭と家族生活の私的領域に閉じ込められた」。「教会、学校、家族が一体となって女性にこの役割を割り当てた」 のである。[58] 1807年のメキシコでは、人々は「社会問題の根本原因として女性の行動を挙げ」、それがヌエバ・エスパーニャの崩壊を招くと考えた。この時代、女性は男 性より劣っており、ジェンダーの不平等は説教における権力の源泉として利用された。植民地時代および独立初期のメキシコでは、男性大司教たちが「父権的社 会規範を明示的に呼び起こすか、あるいは男性性と女性性の比喩を巧みに応用してそれらを創造的に強化する」言語を用いた。[57] 研究によれば、「教会は婚姻における血縁関係の規範的規則を通じて、また婚姻が双方による自由意思に基づくべきという期待によって課された表向きの制限を 通じて、同様に女性の結婚選択を形作る役割を果たした」ことが示されている。[57] 冷戦期には、共産主義の影響力が「教会とメキシコ女性にとって中心的な政治的争点であり、共通の目的となった」[58]。冷戦以前、女性は家庭という私的 領域に閉じ込められていた。「共産主義イデオロギーの攻勢が主張される中、[女性を私的領域に閉じ込めるという概念]は公的な関心事となった」[58]。 その結果、女性は「新たな政治参加の形態を創出し、前例のない政治的能力の自覚」を得るとともに、教会活動への関与を深めた。[58] 女性は「公的領域における自らの可能性に目覚めた」のである。[58] メキシコカトリック教会における典型的な女性像は「聖母マリアの立場、あるいはより大衆的な表現であるグアダルーペの聖母に由来する」ものであった。聖母 マリアは女性や少女たちの「模範」とされ、「受動性、自己犠牲、無私の精神、貞操」によって際立っていた[58]。教会は聖母マリアの宗教的・母性的・精 神的役割を普及させ、「女性の地位を支える態度や象徴を支配した」[58]。 ナワ族の女性 植民地時代の先住民ナワ族の女性は、メキシコ社会におけるカトリック教会の領域において、男性と比較して自らの役割において権力と権威を著しく欠いていた ことで注目された。「メキシコシティにおけるナワ族女性の宗教的責任は、公の場における男性の公式に認められた地位と、家庭における女性の私的な責任との 間に位置していた」と見なされている。[59] 彼女たちは本来なら与えられるべきだった公認の権力を否定されていた[59]。権威の欠如は、不満から時折暴力が噴出する結果を招いた。「少なくとも4分 の1の事例では、女性が攻撃を主導し、外部権威に対する行動が明らかに攻撃的だった」。またカトリック教会社会において修道女になることも許されなかっ た。[59] 女性は「カトリック教会の教義に従う場合にのみ、神の恩寵と保護を受ける受容者」となるべきとされた。女性に対する規則や規制は、明らかに男性向けのもの より厳格で硬直していた。[59] ヴェラ・ペルペトゥアの女性たち 「ヴェラ・ペルペトゥアの女性たち」と呼ばれる、女性が主導する教会指向の組織に関する具体的な証拠が存在する。この「聖体を徹夜で守護することを主目的 とする女性中心の信徒組織」は、「教会の厳格な階層的ジェンダーイデオロギーへの暗黙の挑戦」という点で特異であった。ヴェラ・ペルペトゥアの規約は、混 血の信徒敬虔組織において、女性のみが役員を務めることを義務付けていたのである。[60] 学者らは、この女性主導組織が「グアナファト州、ミチョアカン州、ハリスコ州(メキシコ中部西部のバヒオ地方)の小都市に主に存在した」と推測している [60]。当時「女性の指導者とはカトリック信徒社会において前代未聞の事象だった。女性が『男性を統治する』立場にあったのだ」[60]。ベラ・ペルペ トゥアは1840年に創設されたが、その逆転したジェンダー役割の遺産は、はるか後世になるまで称賛も認知もされなかった。 学者の研究によれば、「女性主導のベラ・ペルペトゥアという構想を最初に考案した人物を、我々は確証を持って知ることも、知ることもできない」[60]。 しかし、この組織が敬虔な母親、祖母、曾祖母らで構成されていたことは明らかである。[60] 彼女たちは、自らの生活を包むカトリック教会の領域において歴史的に否定されてきた「女性らしさ」の感覚をもたらした。社会的な宗教的自由が提供されたた め、周辺コミュニティの他の者たちは「教会を支え、一種の宗教的市民権——教会内でのより大きな平等とより大きな力——を主張する手段としてヴェラに目を 向けた」[60]。こうした非伝統的な教会活動に怒った男性たちもいた。「ヴェラ・ペルペトゥア創設から4年後、初の男性専用ヴェラが設立された」 [60]。男性専用ヴェラが創設されたにもかかわらず、「複数の女性ヴェラは、その効率的な組織運営を称賛され、司教から特に評価された」[60]。 |

| Official Church teaching on marital love and sexual matters According to the Church, humans are sexual beings whose sexual identity extends beyond the body to the mind and spirit. The sexes are meant by divine design to be different and complementary, each having equal dignity and made in the image of God.[15] The sexual act is sacred within the context of the marital relationship and reflects a complete and lifelong mutual gift of a man and a woman.[14] Sexual sins thus violate not just the body but the person's whole being.[14] In his 1995 book Crossing the Threshold of Hope, John Paul II reflected on this concept by stating, Young people are always searching for the beauty in love. They want their love to be beautiful. If they give in to weakness, following the models of behavior that can rightly be considered a "scandal in the contemporary world" (and these are, unfortunately, widely diffused models), in the depths of their hearts they still desire a beautiful and pure love. This is as true of boys as it is of girls. Ultimately, they know that only God can give them this love. As a result, they are willing to follow Christ, without caring about the sacrifices this may entail.[61] |

婚姻の愛と性に関する教会の公式教義 教会によれば、人間は性的存在であり、その性的アイデンティティは身体を超え、精神と魂にまで及ぶ。男女は神の設計により異なるものであり、互いに補完し 合う存在として意図されている。それぞれが等しい尊厳を持ち、神の姿に造られている。[15] 性行為は婚姻関係という文脈において神聖であり、男性と女性の完全かつ生涯にわたる相互の献身を反映するものである。[14] したがって性的罪は身体だけでなく、人格の全体を傷つける。[14] ヨハネ・パウロ二世は1995年の著書『希望の門をくぐって』でこの概念について次のように述べている。 若者たちは常に愛の美しさを求めている。彼らは自らの愛が美しいものであることを望む。たとえ弱さに屈し、「現代世界におけるスキャンダル」と正しく呼べ る行動様式(残念ながら広く蔓延している)に従ったとしても、心の奥底では依然として美しく純粋な愛を渇望している。これは少年にも少女にも等しく当ては まる。結局のところ、彼らには神だけがこの愛を与えられると分かっている。その結果、彼らは犠牲を厭わずキリストに従おうとするのである。[61] |

| Sexual morality Main article: Catholic teachings on sexual morality The Catholic Church teaches that human life and human sexuality are inseparable.[62] Because Catholics believe that God created human beings in his own image and likeness and that he found everything he created to be "very good",[63] the Church teaches that the human body and sex must likewise be good. The Church considers the expression of love between husband and wife to be an elevated form of human activity, joining as it does husband and wife in complete mutual self-giving, and opening their relationship to new life. "The sexual activity in which husband and wife are intimately and chastely united with one another, through which human life is transmitted, is, as the recent Council recalled, 'noble and worthy'.”[64] The Church teaches that sexual intercourse has a purpose, fulfilled only in marriage.[14] According to the catechism, "conjugal love ... aims at a deeply personal unity, a unity that, beyond union in one flesh, leads to forming one heart and soul"[65] since the marriage bond is to be a sign of the love between God and humanity.[66] Vocation to chastity Church teaching on the sixth commandment includes discussion about chastity. The Catechism calls it a "moral virtue ... a gift from God, a grace, a fruit of spiritual effort."[67] Because the Church sees sex as more than just a physical act. an act that affects both body and spirit, it teaches that chastity is a virtue all people are called to acquire.[67] It is defined as the inner unity of a person's "bodily and spiritual being" that successfully integrates a person's sexuality with his or her "entire human nature".[67] To acquire this virtue one is encouraged to enter into the "long and exacting work" of self-mastery that is helped by friendships, God's grace, maturity, and education "that respects the moral and spiritual dimensions of human life."[67] The Catechism categorizes violations of the sixth commandment into two categories: "offenses against chastity" and "offenses against the dignity of marriage".[68] Offenses against chastity The Catechism lists the following "offenses against chastity"[68] in increasing order of gravity, according to Kreeft:[69] 1. Lust: the Church teaches that sexual pleasure is good and created by God who meant for spouses to "experience pleasure and enjoyment of body and spirit." Lust does not mean sexual pleasure as such, nor the delight in it, nor the desire for it in its right context.[70] Lust is the desire for pleasure of sex apart from its intended purpose of procreation and the uniting of man and woman, body and spirit, in mutual self-donation.[69] 2. Masturbation is considered sinful for the same reasons as lust but is a step above lust in that it involves also a physical act.[69] 3. Fornication is the sexual union of an unmarried man and an unmarried woman. This is considered contrary to the dignity of persons and of human sexuality because it is not ordered to the good of spouses or the procreation of children.[69] 4. Pornography ranks yet higher on the scale in gravity of sinfulness because it is considered a perversion of the sexual act which is intended for distribution to third parties for viewing.[69] Also it is often produced without free, adult consent.[citation needed] 5. Prostitution is sinful for both the prostitute and the customer; it reduces a person to an instrument of sexual pleasure, violating human dignity and harming society as well. The gravity of the sinfulness is less for prostitutes who are forced into the act by destitution, blackmail, or social pressure.[69] 6. Rape is an intrinsically evil act that can cause grave damage to the victim for life. 7. Incest, or "rape of children by parents or other adult relatives" or "those responsible for the education of the children entrusted to them" is considered the most heinous of sexual sins.[68][69] |

性的道徳 主な記事:カトリックの性的道徳に関する教え カトリック教会は、人間の生命と人間の性(セクシュアリティ)は切り離せないものであると教える。[62] カトリック教徒は、神が自らの姿と似姿に人間を創造し、創造したすべてのものを「非常に良い」と認めたと信じているため、[63] 教会は人間の身体と性も同様に良いものであると教える。教会は、夫婦間の愛の表現を、高貴な人間活動の一形態と見なしている。それは夫婦を完全な相互の自 己献身によって結びつけ、新たな生命へとその関係を開放するものである。「夫婦が親密かつ貞潔に結ばれ、それによって人間の生命が伝達される性的活動は、 最近の公会議が想起したように、『高貴で価値ある』ものである。」[64] 教会は、性交には目的があり、それは結婚においてのみ成就されると教える[14]。カテキズムによれば、「夫婦の愛は…深く個人的な一致、すなわち一つの 肉となる結合を超え、一つの心と魂を形成する一致を目指す」[65]。なぜなら、結婚の絆は神と人間との愛のしるしとなるべきものだからである[66]。 貞潔への召命 第六戒に関する教会の教えには貞潔についての議論が含まれる。カテキズムはこれを「道徳的徳性…神からの賜物、恩寵、霊的努力の果実」と呼ぶ[67]。教 会は性行為を単なる肉体的行為ではなく、肉体と精神の両方に影響を及ぼす行為と見なすため、貞潔は全ての人々が獲得を求められる徳であると教える [67]。貞潔は人格の「肉体と精神の存在」の内的な統一として定義され、人格の性欲を人格の「人間性の全体」と調和させるものである[67]。この徳を 獲得するには、友情、神の恵み、成熟、そして「人間の生活の道徳的・精神的側面を尊重する」教育によって支えられる「長く厳しい自己制御の作業」に取り組 むことが推奨される。[67] カテキズムは第六戒の違反を二つのカテゴリーに分類する:「貞潔に対する罪」と「結婚の尊厳に対する罪」である。[68] 貞潔に対する罪 カテキズムはクリーフトによれば[69]、以下の「貞潔に対する罪」[68]を重大性の順に列挙している: 1. 淫欲:教会は性的快楽は善であり、配偶者が「肉体と精神の喜びと楽しみを経験する」ことを意図した神によって創造されたと教える。淫欲とは、性的快楽その ものや、その喜び、あるいは正当な文脈におけるその欲求を意味しない。[70] 淫欲とは、生殖という本来の目的や、男女の肉体と精神が相互の自己献身によって結ばれるという目的から切り離された、性行為の快楽への欲求である。 [69] 2. 自慰行為は、情欲と同じ理由で罪とみなされるが、身体的行為を伴う点で情欲より一段階重い。[69] 3. 姦淫とは、未婚の男女の性的結合である。これは配偶者の善や子孫繁栄に向けられていないため、人間の個人的な人格と人間の性に対する人格に反するとされる。[69] 4. ポルノグラフィーは、第三者への配布・閲覧を目的とした性的行為の歪曲と見なされるため、罪の重大性においてさらに上位に位置づけられる。[69] また、多くの場合、自由な成人の同意なしに制作される。[出典が必要] 5. 売春は売春婦と客の双方にとって罪深い行為である。人格を性的快楽の道具に貶め、人間の尊厳を侵害し、社会にも害を及ぼす。貧困、脅迫、社会的圧力によって売春を強いられた者については、罪の重さは軽減される。[69] 6. 強姦は本質的に悪なる行為であり、被害者に生涯にわたる深刻な損害をもたらしうる。 7. 近親相姦、すなわち「親やその他の成人親族による児童への強姦」あるいは「教育を委託された児童の責任者による行為」は、性的罪悪の中で最も凶悪なものと見なされる。[68][69] |

Love of husband and wife Matrimony, The Seven Sacraments, Rogier van der Weyden, c. 1445. Spousal love, according to Church teaching, is meant to achieve an unbroken, twofold end: union of husband and wife as well as transmission of life.[71] The unitive aspect includes a person's whole being that calls spouses to grow in love and fidelity "so that they are no longer two but one flesh."[71] The sacrament of matrimony is viewed as God's sealing of spousal consent to the gift of themselves to each other. Church teaching on the marital state requires spousal acceptance of each other's failures and faults and the recognition that the "call to holiness in marriage" is one that requires a process of spiritual growth and conversion that lasts throughout life.[71] |

夫婦の愛 『結婚』、七つの秘跡、ロヒール・ファン・デル・ウェイデン作、1445年頃。 教会の教えによれば、配偶者間の愛は、絶えることのない二重の目的を達成することを意図している。すなわち、夫と妻の結合と、生命の伝達である[71]。 結合の側面には、人の全人格が含まれ、配偶者たちは愛と忠実さの中で成長するよう招かれている。「もはや二人ではなく、一つの肉となる」ためである。 [71] 婚姻の秘跡は、配偶者が互いに自分自身を捧げるという合意を神が確証するものとして捉えられる。婚姻状態に関する教会の教えは、配偶者が互いの失敗や欠点 を受け入れ、「結婚における聖性への招き」が、生涯にわたる霊的成長と回心の過程を必要とするものであることを認識することを求めている。[71] |

| Fecundity of marriage, sexual pleasure, birth control Throughout Church history, various Catholic thinkers have offered differing opinions on sexual pleasure. Some saw it as sinful, while others disagreed.[72] There was no formal Church position in the matter until the 1546 Council of Trent decided that "concupiscence" invited sin but was "not formally sinful in itself".[72] In 1679, Pope Innocent XI also weighed in by condemning "marital sex exercised for pleasure alone".[72] The Church position on sexual activity can be summarized as: "sexual activity belongs only in marriage as an expression of total self-giving and union, and always open to the possibility of new life". Sexual acts in marriage are considered "noble and honorable" and are meant to be enjoyed with "joy and gratitude".[71] The existence of artificial methods of birth control predates Christianity; the Catholic Church as well as all Christian denominations condemned artificial methods of birth control throughout their respective histories. This began to change in the 20th century when the Church of England became the first to accept the practice in 1930.[73] The Catholic Church responded to this new development by issuing the papal encyclical Casti connubii on 31 December 1930. The 1968 papal encyclical Humanae vitae is a reaffirmation of the Catholic Church's traditional view of marriage and marital relations and a continued condemnation of artificial birth control.[73] The Church encourages large families and sees this as a blessing. It also recognizes that responsible parenthood sometimes calls for reasonable spacing or limiting of births and thus considers natural family planning as morally acceptable but rejects all methods of artificial contraception.[74] The Church rejects all forms of artificial insemination and fertilization because such techniques divorce the sexual act from the creation of a child. The Catechism states, "A child is not something owed to one, but is a gift, … 'the supreme gift of marriage'."[74] Rejecting Church support for natural family planning as a viable form of birth control, some Church members and non-members criticize Church teachings that oppose artificial birth control as outdated and as contributing to overpopulation, and poverty.[75] The Church's rejection of the use of condoms is especially criticized with respect to countries where the incidence of AIDS and HIV has reached epidemic proportions. In countries like Kenya and Uganda, where behavioral changes are encouraged alongside condom use, greater progress in controlling the disease has been made than in those countries solely promoting condoms.[76][77] Cardinal Christoph Schönborn is among the higher clergy who have allowed for the use of condoms by someone suffering from AIDS, as a "lesser evil".[78] |

結婚の豊饒性、性的快楽、避妊 カトリック教会の歴史を通じて、様々な思想家が性的快楽について異なる見解を示してきた。罪深いものと見なす者もいれば、そうではないと主張する者もい た。[72] この問題について教会が公式な立場を示すことはなかったが、1546年のトリエント公会議で「情欲は罪を招くが、それ自体が正式な罪ではない」と決定され た。[72] 1679年には教皇イノセント11世も「快楽のみを目的とした婚姻内性行為」を非難する見解を示した。[72] 教会の性行為に関する立場は次のように要約できる:「性行為は完全な自己献身と結合の表現として、かつ常に新たな生命の可能性に開かれた形で、婚姻内のみ に属するものである」。婚姻内の性行為は「高貴で名誉ある」ものとされ、「喜びと感謝をもって」享受されるべきとされる。[71] 人工避妊法はキリスト教以前から存在していたが、カトリック教会を含む全てのキリスト教派は、それぞれの歴史を通じて人工避妊法を非難してきた。この状況 は20世紀に入り変化し始め、1930年に英国国教会が初めてこの慣行を容認した。[73] カトリック教会はこの新たな動きに対し、1930年12月31日に教皇回勅『カスティ・コンヌビイ』を発布して対応した。1968年の教皇回勅『ヒューマ ネ・ヴィターエ』は、カトリック教会の伝統的な結婚観と夫婦関係の見解を再確認し、人工避妊を継続的に非難するものである。[73] 教会は大家族を奨励し、これを祝福と見なしている。また、責任ある親としての役割が時に合理的な出産間隔や出産制限を必要とすることもあり、自然家族計画 は道徳的に許容されると見なす一方、あらゆる人工避妊法は拒否する。[74] 教会はあらゆる形態の人工授精や体外受精を拒否する。なぜなら、こうした技術は性行為と子供の創造を分離させるからである。カテキズムは「子供は誰かに与 えられるべきものではなく、贈り物である…『結婚の最高の賜物』である」と述べている。[74] 教会が自然家族計画を有効な避妊法として支持することを拒否する一部の教会関係者や非信者は、人工避妊に反対する教会の教えを時代遅れであり、人口過多や 貧困を助長するものだと批判している。[75] 特にエイズやHIVの発生率が流行レベルに達している国々においては、教会がコンドームの使用を拒否していることが強く批判されている。ケニアやウガンダ のような国々では、コンドーム使用と並行して行動変容が促されているため、コンドームのみを推進する国々よりも、この病気の抑制においてより大きな進展が 見られている。[76][77] クリストフ・シェーンボルン枢機卿は、苦悩する者が「より小さな悪」としてコンドームを使用することを認めた高位聖職者の一人である。[78] |

| Gender identity In "Male and female he created them: toward a path of dialogue on the question of gender identity in education", the Congregation for Catholic Education states that sex and gender can be seen as distinct concepts, but should not be considered independent of one another,[79] and that the church does not approve of the concept of gender identity or the ideology that follows from it.[80] The congregation explains that men are men and male and that women are women and female due to their sex chromosomes,[81] and that hermaphrodites and people confused about their sex ought to receive medical assistance rather than be treated as a third gender or genderless.[82][failed verification] The Church also explains that Catholics must not unjustly discriminate against transgender people; an example of just discrimination is exclusion from ordination since the church sees transgender men as women and transgender women as men unfit for the priesthood.[83][84] |

ジェンダー カトリック教育省は「男と女として創造された:教育におけるジェンダーの問題に関する対話の道へ」において、性別とジェンダーは異なる概念と見なせるが、 互いに独立したものとして考えるべきではないと述べている[79]。また教会は、ジェンダーの概念やそれに基づくイデオロギーを承認しないとしている。同 省は、男性は男性であり男性的であり、女性は女性であり女性的であるのは、その性染色体によるものであると説明する[81]。また、両性具有者や自身の性 別に混乱している人々は、第三のジェンダーや無性として扱われるのではなく、医療的支援を受けるべきであると述べている。[82][検証失敗] 教会はまた、カトリック教徒がトランスジェンダーの人々を不当に差別してはならないと説明している。正当な差別の例として、規律への任命からの排除が挙げ られる。教会はトランスジェンダーの男性を女性として、トランスジェンダーの女性を男性として認識しており、いずれも司祭職にふさわしくないと見なしてい るからだ。[83][84] |

| Priesthood, religious life, celibacy See also: Hierarchy of the Catholic Church § In general In the Catholic Church, only men may become ordained clergy through the sacrament of Holy Orders, as bishops, priests or deacons. All clergy who are bishops form the College of Bishops and are considered the successors of the apostles.[85][86][note 1] The Church practice of celibacy is based on Jesus' example and his teaching as given in Matthew 19:11–12, as well as the writings of St. Paul who spoke of the advantages celibacy allowed a man in serving the Lord.[96] Celibacy was "held in high esteem" from the Church's beginnings. It is considered a kind of spiritual marriage with Christ, a concept further popularized by the early Christian theologian Origen. Clerical celibacy began to be demanded in the 4th century, including papal decretals beginning with Pope Siricius.[97] In the 11th century, mandatory celibacy was enforced as part of efforts to reform the medieval church.[98] The Catholic view is that since the twelve apostles chosen by Jesus were all male, only men may be ordained in the Catholic Church.[99] While some consider this to be evidence of a discriminatory attitude toward women,[100] the Church believes that Jesus called women to different yet equally important vocations in Church ministry.[101] Pope John Paul II, in his apostolic letter Christifideles Laici, states that women have specific vocations reserved only for the female sex, and are equally called to be disciples of Jesus.[102] This belief in different and complementary roles between men and women is exemplified in Pope Paul VI's statement "If the witness of the Apostles founds the Church, the witness of women contributes greatly towards nourishing the faith of Christian communities."[102] Further information: Catholic Church doctrine on the ordination of women |

聖職、修道生活、独身制 関連項目: カトリック教会の階層 § 概説 カトリック教会では、聖職叙階の秘跡を通じて司教、司祭、助祭として聖職に叙階されるのは男性のみである。司教である全ての聖職者は司教団を構成し、使徒たちの後継者と見なされる。[85][86][注1] 教会の独身制は、マタイによる福音書19章11-12節に記されたイエスの模範と教え、および独身が主に仕える上で男性にもたらす利点について述べた聖パ ウロの書簡に基づいている。[96] 独身制は教会の創始期から「高く評価」されてきた。これはキリストとの一種の霊的結婚と見なされ、この概念は初期キリスト教神学者オリゲネスによってさら に広められた。聖職者の独身制は4世紀に要求され始め、教皇シリキウス以降の教皇勅書にも見られる。[97] 11世紀には、中世教会の改革の一環として強制的な独身制が施行された。[98] カトリックの見解では、イエスが選んだ十二使徒は全員男性であったため、カトリック教会で叙階されるのは男性のみである。[99] これを女性に対する差別的態度と見る向きもあるが[100]、教会はイエスが女性に対し、教会奉仕において異なるが同等に重要な召命を与えたと信じる [101]。教皇ヨハネ・パウロ2世は使徒的書簡『キリストの信徒』において、女性には女性だけに与えられた固有の召命があり、同等にイエスの弟子となる よう招かれていると述べている。[102] この男女の役割が異なる補完的であるという信念は、教皇パウロ6世の「使徒たちの証言が教会を築くならば、女性の証言はキリスト教共同体の信仰を育むこと に大きく寄与する」という発言に示されている。[102] 詳細情報:女性の叙階に関するカトリック教会の教義 |

| Role of women Main article: Women in the Catholic Church Official Church teaching considers women and men to be equal and "complementary".[13] A special role and devotion is accorded to Jesus' mother Mary as "nurturing mother" of Christ and the Church. Marian devotion has been a central theme of Catholic art, and motherhood and family are given a sacred status in church teachings. Conversely, the role of Eve in the Biblical story of the Garden of Eden affected the development of a Western notion of woman as "temptress". Unusually for his epoch, Jesus preached to men and women alike. St. Paul had much to say about women and about ecclesiastical directives for women. Based on a reading of the Gospels that Christ selected only male Apostles, the Church does not ordain women to the priesthood (see above). Nevertheless, throughout history, women have achieved significant influence in the running of Catholic institutions – particularly in hospitals and schooling, through religious orders of nuns or sisters like the Benedictines, Dominicans, Loreto Sisters, Sisters of Mercy, Little Sisters of the Poor, Josephites, and Missionaries of Charity. Pope Francis has been noted for his efforts to recognize feminine gifts and to increase the presence of women in high offices in the Church.[103][104][105][106][107] |

女性の役割 主な記事: カトリック教会における女性 公式の教会教義は、女性と男性は平等であり「補完的」であると考えている。[13] イエスの母マリアには、キリストと教会の「養育する母」として特別な役割と崇敬が与えられている。マリア崇敬はカトリック美術の中心的なテーマであり、母 性と家族は教会教義において神聖な地位を与えられている。一方、聖書のエデンの園の物語におけるエバの役割は、西洋における女性を「誘惑者」とする概念の 発展に影響を与えた。当時の常識から外れて、イエスは男女を問わず説教した。聖パウロは女性について、また女性に対する教会の指示について多くを語った。 福音書に基づく解釈として、キリストが選んだ使徒は男性のみであったため、教会は女性を司祭に叙階しない(前述参照)。しかしながら、歴史を通じて女性は カトリック機関の運営において重要な影響力を獲得してきた。特に病院や教育分野では、ベネディクト会、ドミニコ会、ロレート修道女会、慈悲の姉妹会、貧し い人々の小さな姉妹会、ヨセフ会、慈善の宣教者会といった修道女会を通じて顕著である。教皇フランシスコは、女性の賜物を認め、教会内の高位職における女 性の存在感を高める努力で注目されている。[103][104][105][106][107] |

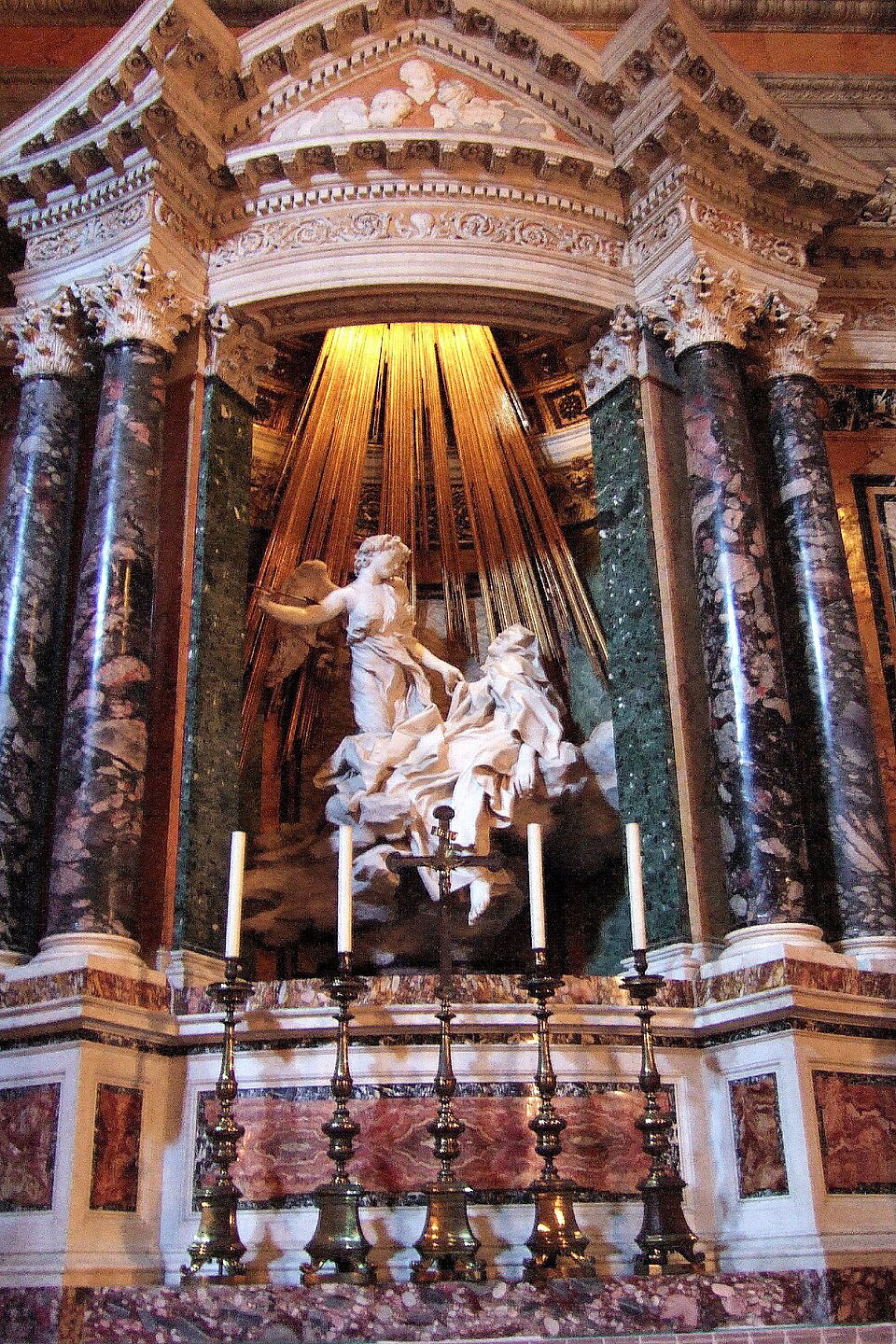

Spiritual affection The Ecstasy of St Theresa in the basilica of Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome, by Italian baroque artist Gianlorenzo Bernini Spiritual affection has long been documented in various lives of the saints. Biographies of Thomas Aquinas, Teresa of Avila, Martin de Porres, Joseph of Cupertino, and many others include episodes of spiritual affection witnessed both by those who knew the saint or confessed by the saints themselves in their own writings. In Saint Teresa's Life for instance, she describes what has become known as the Ecstasy of Saint Theresa: The loving exchange that takes place between the soul and God is so sweet that I beg Him in His goodness to give a taste of his love to anyone who thinks I am lying. On certain days I went about as though stupefied. I desired neither to see nor to speak, but to clasp my suffering close to me, for to me it was greater glory than all creation. Sometimes it happened – when the Lord desired – that these raptures were so great that even though I was among people I couldn't resist them; to my deep affliction they began to made public."[108] |

霊的な愛情 ローマ、サンタ・マリア・デッラ・ヴィットーリア大聖堂にある、聖テレサの恍惚状態。イタリアのバロック芸術家、ジャンロレンツォ・ベルニーニによる作品。 霊的な愛情は、聖人たちのさまざまな生涯の中で長い間記録されてきた。トマス・アクィナス、アビラのテレサ、マーティン・デ・ポレス、クペルティーノのヨ セフ、その他多くの聖人たちの伝記には、聖人を知っていた人々によって目撃された、あるいは聖人自身が自らの著作の中で告白した、霊的な愛情のエピソード が含まれている。例えば、聖テレサの『自伝』の中で、彼女は、聖テレサのエクスタシーとして知られるようになったものを次のように記述している。 魂と神の間で交わされる愛情の交換は、とても甘美なものである。だから、私が嘘をついていると思う人には、神の愛を少し味わってほしいと、その良さに頼み たい。ある日は、私は呆然としたように過ごした。見ることも話すことも望まず、ただ苦悩を胸に抱きしめたかった。それは私にとって、あらゆる被造物よりも 大きな栄光だった。時に――主が望まれる時――この恍惚があまりに強くなり、人混みの中にいても抗えなかった。深い苦悩と共に、それが公然と現れ始めたの である。」[108] |

| Theology of the Body Women in the Catholic Church |

身体の神学 カトリック教会における女性 |

| Only bishops can

administer the sacrament of Holy Orders; and, in the Latin Rite,

Confirmation is ordinarily reserved to them.[87] Bishops are

responsible for teaching and governing the faithful of their diocese,

sharing these duties with the priests and deacons who serve under them.

Only priests and bishops may celebrate the Eucharist and administer the

sacraments of Penance and Anointing of the Sick. They and deacons may

preach, teach, baptize, witness marriages and conduct funeral

services.[88] Baptism is normally performed by clergy but is the only

sacrament that may be administered in emergencies by any Catholic or

even a non-Christian "who has the intention of baptizing according to

the belief of the Catholic Church".[89] Married men may become deacons,

but only celibate men can ordinarily be ordained as priests in the

Latin Rite.[90][91] Married clergymen who have converted to the Church

from other denominations are sometimes exempted from this rule.[92] The

Eastern Catholic Churches ordain both celibate and married men.[93][94]

All rites of the Catholic Church maintain the ancient tradition that

marriage is not allowed after ordination. Men with transitory

homosexual leanings may be ordained deacons following three years of

prayer and chastity, but homosexual men who are sexually active, or

those who have deeply rooted homosexual tendencies cannot be

ordained.[95] |

聖職叙階の秘跡を授けることができるのは司教のみである。またラテン典

礼においては、堅信の秘跡も通常は司教にのみ許されている。[87]

司教は管区内の信徒を教え導く責任を負い、その職務を司祭や助祭らと分担する。司祭と司教のみが聖体祭儀を執行し、告解と病者の塗油の秘跡を授けることが

できる。彼らと助祭は説教、教導、洗礼、婚姻の立会、葬儀の執行を行うことができる。[88]

洗礼は通常聖職者によって行われるが、緊急時にはカトリック信徒、あるいは「カトリック教会の信仰に従って洗礼を施す意図を持つ」非キリスト教徒であって

も授けることができる唯一の秘跡である。[89]

既婚男性は助祭になることができるが、ラテン典礼では通常、独身男性のみが司祭に叙階される。[90][91]

他宗派からカトリック教会に改宗した既婚聖職者は、この規則が免除される場合がある。[92]

東方カトリック教会は独身者と既婚者の両方を叙階する。[93] [94]

カトリック教会のあらゆる典礼は、叙階後の結婚を認めないという古代の伝統を維持している。一時的な同性愛傾向を持つ男性は、3年間の祈りと貞潔の期間を

経て助祭に叙階される可能性があるが、性的活動を行う同性愛者、あるいは根深い同性愛傾向を持つ者は叙階できない。[95] |

| References | |

| Bibliography Brundage, James (1987). Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-07784-0. ——; Nelson, Janet; Linehan, Peter (2001). Sin, Crime and the Pleasures of the Flesh: the Medieval Church Judges Sexual Offences. London: Routledge. pp. 294–305. ISBN 978-0-415-18151-8. {{cite book}}: |journal= ignored (help) ——; Ziolkowski, Jan (1998). Obscene and Lascivious. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10928-5. {{cite book}}: |journal= ignored (help) ——; Murray, Jacqueline; Eisenbichler, Konrad (1996a). "Playing by the Rules: Sexual Behavior and Legal Norms in Medieval Europe". Desire and Discipline: Sex and Sexuality in the Premodern West. Toronto: University of Toronto. doi:10.3138/9781442673854-004. ISBN 978-0-8020-7144-6. —— (1996b). Bullough, Vern L.; Brundage, James (eds.). "Sex and Canon Law". Handbook of Medieval Sexuality: 33–50. —— (nd). "Canonical Courts and Procedure". Medieval Canon. —— (1976). "Prostitution in the Medieval Canon Law". Chicago Journals: 825–845. Bokenkotter, Thomas (2004). A Concise History of the Catholic Church. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-50584-0. Chadwick, Owen (1995). A History of Christianity. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-0-7607-7332-1. Duffy, Eamon (1997). Saints and Sinners, a History of the Popes. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07332-4. Dussel, Enrique (1981). A History of the Church in Latin America. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2131-7. Ferro, Mark (1997). Colonization: A Global History. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14007-2. Froehle, Bryan; Mary Gautier (2003). Global Catholicism, Portrait of a World Church. Orbis books; Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, Georgetown University. ISBN 978-1-57075-375-6. Hastings, Adrian (2004). The Church in Africa 1450–1950. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826399-9. Hunter, David (2007). "Sexuality, marriage and the family". Sexuality, Marriage, and the Family. Vol. 2. Cambridge History of Christianity. pp. 585–600. doi:10.1017/chol9780521812443.026. ISBN 9781139054133. Johansen, Bruce (2006). The Native Peoples of North America. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3899-0. Kelly, Henry Ansgar (April 2000). "Bishop, Prioress, and Bawd in the Stews of Southwark". Speculum. 75 (2): 342–388. doi:10.2307/2887582. JSTOR 2887582. S2CID 162696212. Koschorke, Klaus; Ludwig, Frieder; Delgado, Mariano (2007). A History of Christianity in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, 1450–1990. Wm B Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-8028-2889-7. Le Goff, Jacques (2000). Medieval Civilization. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-0-7607-1652-6. Lehner, Ulrich L. (2017). Women, Enlightenment and Catholicism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138687639. Noble, Thomas; Strauss, Barry (2005). Western Civilization. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-618-43277-6. Noll, Mark (2006). The Civil War as a Theological Crisis. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3012-3. Orlandis, Jose (1993). A Short History of the Catholic Church. Scepter Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85182-125-9. John Paul II, Pope (1995). Crossing the Threshold of Hope. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 978-0-679-76561-5. Payer, Pierre; Joyce Salisbury (1991). Sex and Confession in the 13th Century. New York: Garland Pub. pp. 127+. ISBN 978-0-8240-5766-4. {{cite book}}: |journal= ignored (help) Posner, Richard (1994). Sex and Reason. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-80280-3. Rossiaud, Jacques (1988). Medieval Prostitution. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19992-2. Schreck, Alan (1999). The Essential Catholic Catechism. Servant Publications. ISBN 978-1-56955-128-8. Stark, Rodney (1996). The Rise of Christianity. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02749-4. Stearns, Peter (2000). Gender in World History. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22310-2. Thomas, Hugh (1999). The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1440-1870. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-83565-5. Woods Jr, Thomas (2005). How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization. Regnery Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89526-038-3. USCCB (United States Conference of Catholic Bishops) (2008). United States Catechism for Adults. USCCB Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57455-450-2. |

参考文献 ブランデージ、ジェームズ(1987)。『中世ヨーロッパにおける法、性、キリスト教社会』。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-226-07784-0。 ——; ネルソン、ジャネット; ラインハン、ピーター(2001)。『罪、犯罪、そして肉体の快楽:中世教会が性犯罪を裁く』。ロンドン:ラウトレッジ。pp. 294–305。ISBN 978-0-415-18151-8。{{cite book}}: |journal=が無視された(ヘルプ) ——; ジオルコウスキー、ヤン(1998)。『わいせつと好色』。ブリル。ISBN 978-90-04-10928-5。{{cite book}}: |journal=が無視された(ヘルプ) ——; Murray, Jacqueline; Eisenbichler, Konrad (1996a). 「規則に従って遊ぶ:中世ヨーロッパにおける性的行動と法的規範」. 『欲望と規律:前近代西洋における性とセクシュアリティ』. Toronto: University of Toronto. doi:10.3138/9781442673854-004。ISBN 978-0-8020-7144-6。 —— (1996b)。Bullough, Vern L.; Brundage, James (編)。「性と教会法」。『中世のセクシュアリティハンドブック』: 33–50。 —— (nd). 「教会法廷と手続き」. 『中世教会法』. —— (1976). 「中世教会法における売春」. 『シカゴ・ジャーナル』: 825–845. ボケンコッター, トーマス (2004). 『カトリック教会の簡明史』. ダブルデイ. ISBN 978-0-385-50584-0。 チャドウィック、オーウェン(1995)。『キリスト教の歴史』。バーンズ&ノーブル。ISBN 978-0-7607-7332-1。 ダフィー、エイモン(1997)。『聖人と罪人、教皇の歴史』。イェール大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-300-07332-4。 デュッセル、エンリケ(1981)。『ラテンアメリカの教会史』。Wm. B. Eerdmans。ISBN 978-0-8028-2131-7。 フェロ、マーク(1997)。『植民地化:世界史』。Routledge。ISBN 978-0-415-14007-2。 フロール、ブライアン;メアリー・ゴーティエ(2003)。『グローバル・カトリック、世界教会の肖像』。オービスブックス;ジョージタウン大学使徒職応用研究センター。ISBN 978-1-57075-375-6。 ヘイスティングス、エイドリアン(2004) . 『アフリカの教会 1450–1950』. オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-826399-9. ハンター, デイヴィッド (2007). 「セクシュアリティ、結婚、家族」. 『セクシュアリティ、結婚、家族』. 第2巻. ケンブリッジ・キリスト教史. pp. 585–600. doi:10.1017/chol9780521812443.026。ISBN 9781139054133。 ヨハンセン、ブルース(2006)。『北米の先住民』ラトガース大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8135-3899-0。 ケリー、ヘンリー・アンスガー(2000年4月)。「サザークの売春街における司教、修道院長、娼婦」。『スペキュラム』。75巻2号:342–388頁。doi:10.2307/2887582。JSTOR 2887582。S2CID 162696212. コッシャーケ、クラウス; ルートヴィヒ、フリーダー; デルガド、マリアーノ (2007). 『アジア、アフリカ、ラテンアメリカにおけるキリスト教の歴史 1450–1990』. Wm B Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-8028-2889-7. ル・ゴフ、ジャック(2000)。『中世文明』。バーンズ・アンド・ノーブル。ISBN 978-0-7607-1652-6。 レーナー、ウルリッヒ・L.(2017)。『女性、啓蒙主義、カトリック』。ラウトレッジ。ISBN 978-1138687639。 ノーブル、トーマス;ストラウス、バリー(2005)。『西洋文明』。ホートン・ミフリン社。ISBN 978-0-618-43277-6。 ノール、マーク(2006)。『神学的危機としての南北戦争』。ノースカロライナ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8078-3012-3。 オルランディス、ホセ(1993)。『カトリック教会の簡史』。セプター出版社。ISBN 978-1-85182-125-9。 教皇ヨハネ・パウロ二世(1995)。『希望の門をくぐって』。アルフレッド・A・クノップ社。ISBN 978-0-679-76561-5。 ペイヤー、ピエール; ジョイス・ソールズベリー (1991). 『13世紀の性と告白』. ニューヨーク: ガーランド出版. pp. 127+. ISBN 978-0-8240-5766-4. {{cite book}}: |journal=が無視された (ヘルプ) ポズナー、リチャード (1994). 『性と理性』. ハーバード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-674-80280-3。 ロシオ、ジャック(1988)。『中世の売春』。ブラックウェル。ISBN 978-0-631-19992-2。 シュレック、アラン(1999)。『カトリック教理要綱』。サーヴァント出版。ISBN 978-1-56955-128-8。 スターク、ロドニー(1996)。『キリスト教の興隆』。プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-691-02749-4。 スターンズ、ピーター(2000)。『世界史におけるジェンダー』。ラウトレッジ。ISBN 978-0-415-22310-2。 トーマス、ヒュー(1999)。『奴隷貿易:大西洋奴隷貿易の物語、1440-1870』。サイモン・アンド・シュスター。ISBN 978-0-684-83565-5。 ウッズ・ジュニア、トーマス(2005)。カトリック教会が西洋文明を築いた方法。レグナリー出版。ISBN 978-0-89526-038-3。 米国カトリック司教協議会(USCCB)(2008)。成人向け米国カトリック教理問答。USCCB出版。ISBN 978-1-57455-450-2。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sex_and_gender_roles_in_the_Catholic_Church |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099