芸術表象

Representation of arts

☆表象とは、何か他のものの代わりとなる記号を用いることである[1]。人々は表象を通じて、世界の要素に名前を付ける行為によって世界と現実を組織化する[1]。記号は意味構造を形成し、関係性を表現するために配置される。[1]

古代から現代に至る多くの哲学者にとって、人間は「表象する動物」、すなわち動物シンボリカムとみなされている。その特徴は、何か他のものの「代わり」となる、あるいは「その場」を占める記号を創造し、操作する生き物であるということだ。[1]

表象は、美学(芸術)や記号論(記号)と関連付けられてきた。英文学・美術史学者 W. J. T. ミッチェルは、「表象とは、人間を表す石から、ダブリンの住民数人の一日を表す小説まで、非常に弾力的な概念である」と述べている。[1]

表現という用語は、さまざまな意味や解釈を持つ。文学理論では、表現は一般的に 3 つの方法で定義される。

似ている、または似ているように見えること。

何かまたは誰かの代わりとなること。

2 度目に提示すること、再提示すること。[2]

表現に関する考察は、プラトンやアリストテレスの思想における初期の文学理論から始まり、言語、ソシュール、コミュニケーション研究における重要な要素へと発展してきた。[2]

Representation is

the use of signs that stand in for and take the place of something

else.[1] It is through representation that people organize the world

and reality through the act of naming its elements.[1] Signs are

arranged in order to form semantic constructions and express

relations.[1] Bust of Aristotle, Greek philosopher For many philosophers, both ancient and modern, man is regarded as the "representational animal" or animal symbolicum, the creature whose distinct character is the creation and the manipulation of signs – things that "stand for" or "take the place of" something else.[1] Representation has been associated with aesthetics (art) and semiotics (signs). Scholar of English and art history W. J. T. Mitchell says "representation is an extremely elastic notion, which extends all the way from a stone representing a man to a novel representing the day in the life of several Dubliners".[1] The term representation carries a range of meanings and interpretations. In literary theory, representation is commonly defined in three ways: to look like or resemble; to stand in for something or someone; to present a second time, to re-present.[2] The reflection on representation began with early literary theory in the ideas of Plato and Aristotle, and has evolved into a significant component of language, Saussurian and communication studies.[2] |

表象とは、何か他のものの代わりとなる記号を用いることである[1]。

人々は表象を通じて、世界の要素に名前を付ける行為によって世界と現実を組織化する[1]。記号は意味構造を形成し、関係性を表現するために配置される。

[1] ギリシャの哲学者、アリストテレスの胸像 古代から現代に至る多くの哲学者にとって、人間は「表象する動物」、すなわち動物シンボリカムとみなされている。その特徴は、何か他のものの「代わり」と なる、あるいは「その場」を占める記号を創造し、操作する生き物であるということだ。[1] 表象は、美学(芸術)や記号論(記号)と関連付けられてきた。英文学・美術史学者 W. J. T. ミッチェルは、「表象とは、人間を表す石から、ダブリンの住民数人の一日を表す小説まで、非常に弾力的な概念である」と述べている。[1] 表現という用語は、さまざまな意味や解釈を持つ。文学理論では、表現は一般的に 3 つの方法で定義される。 似ている、または似ているように見えること。 何かまたは誰かの代わりとなること。 2 度目に提示すること、再提示すること。[2] 表現に関する考察は、プラトンやアリストテレスの思想における初期の文学理論から始まり、言語、ソシュール、コミュニケーション研究における重要な要素へ と発展してきた。[2] |

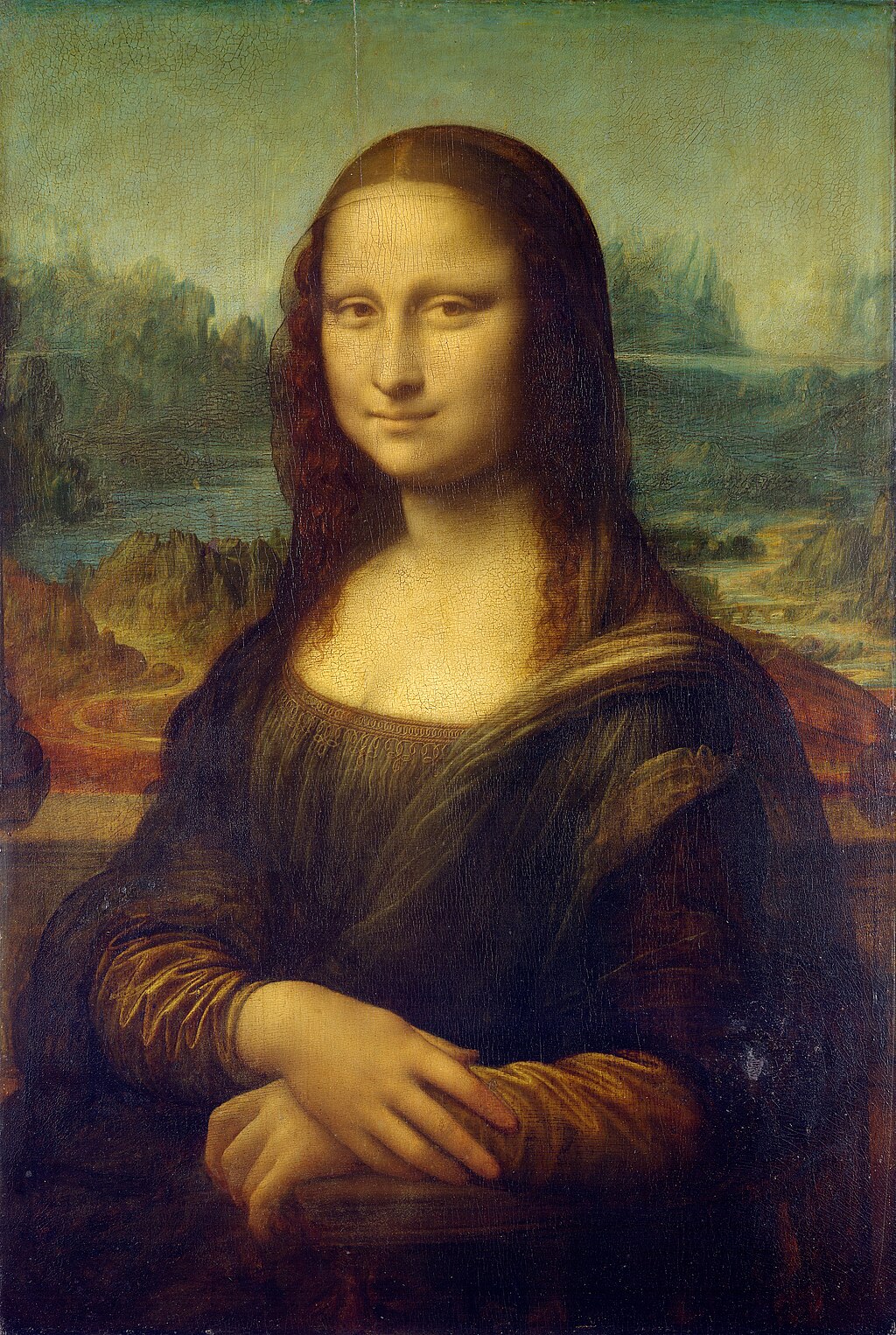

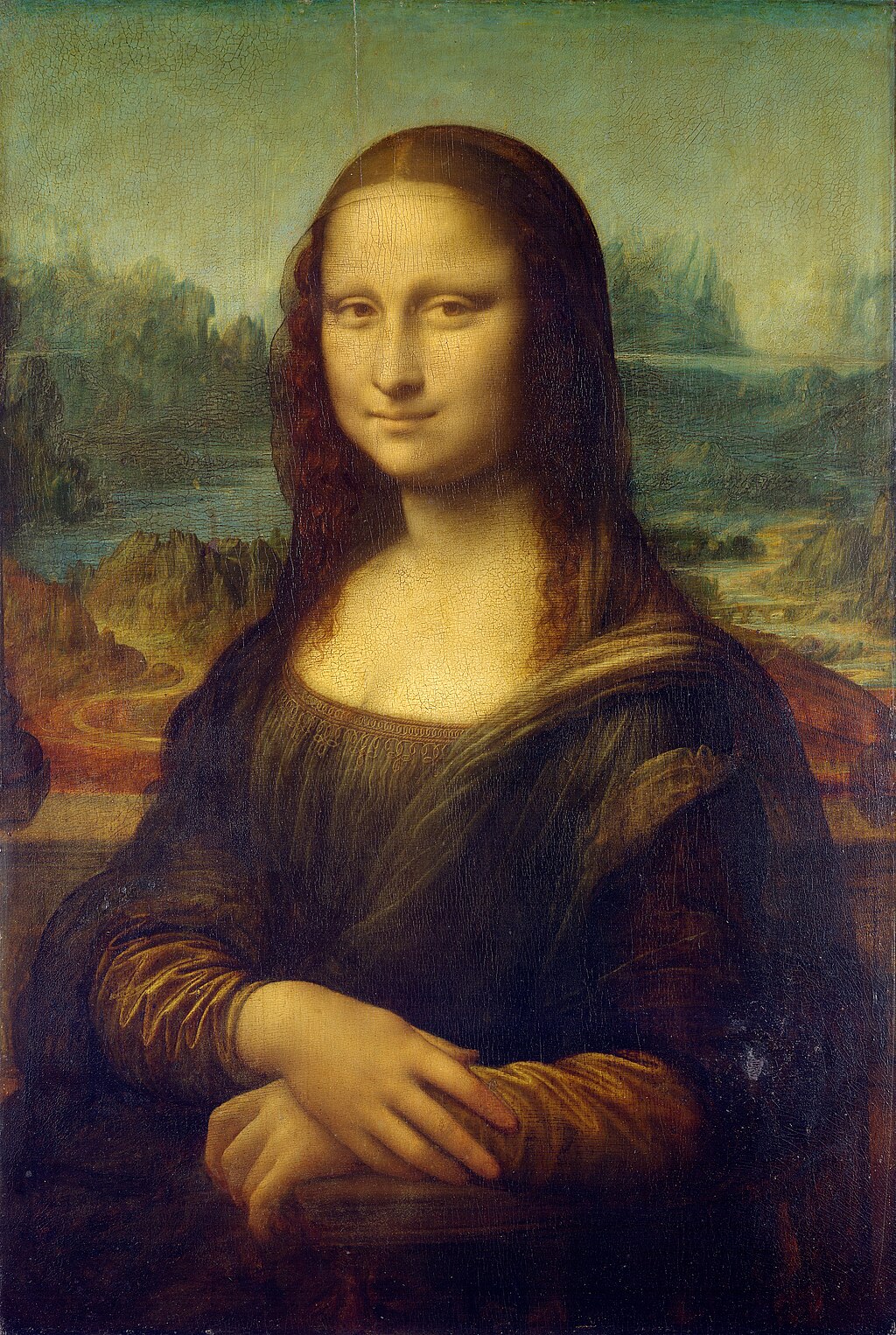

Defining representation Reproduction of the Mona Lisa To represent is "to bring to mind by description," also "to symbolize, to be the embodiment of;" from representer (12c.), from L. repraesentare, from re-, intensive prefix, + praesentare "to present," lit. "to place before".[original research?] A representation is a type of recording in which the sensory information about a physical object is described in a medium. The degree to which an artistic representation resembles the object it represents is a function of resolution and does not bear on the denotation of the word. For example, both the Mona Lisa and a child's crayon drawing of Lisa del Giocondo would be considered representational, and any preference for one over the other would need to be understood as a matter of aesthetics.[citation needed] |

表象の定義 モナ・リザの複製 表象するとは「描写によって思い起こさせること」、また「象徴すること、具現化すること」を意味する。語源はrepresenter(12世紀)に遡り、 ラテン語repraesentareに由来する。re-(強調接頭辞)とpraesentare(提示する)の合成語で、文字通り「前に置く」を意味す る。[独自研究?] 表現とは、物理的対象に関する感覚情報を媒体に記述する記録の一種である。芸術的表現が対象に似ている度合いは解像度の関数であり、この言葉の指示対象に は関係しない。例えばモナ・リザも、子供が描いたリサ・デル・ジョコンドのクレヨン画も表現的と見なされ、どちらを好むかは美学の問題として理解される必 要がある。[出典が必要] |

History Greek theatrical masks depicted in a mosaic in Hadrian's Villa Since ancient times representation has played a central role in understanding literature, aesthetics and semiotics. Plato and Aristotle are key figures in early literary theory who considered literature as simply one form of representation.[3] Aristotle for instance, considered each mode of representation, verbal, visual or musical, as being natural to human beings.[4] Therefore, what distinguishes humans from other animals is their ability to create and manipulate signs.[5] Aristotle deemed mimesis as natural to man, therefore considered representations as necessary for people's learning and being in the world.[4] Plato, in contrast, looked upon representation with more caution. He recognised that literature is a representation of life, yet also believed that representations intervene between the viewer and the real. This creates worlds of illusion leading one away from the "real things".[6] Plato thus believed that representation needs to be controlled and monitored due to the possible dangers of fostering antisocial emotions or the imitation of evil.[5] Aristotle went on to say it was a definitively human activity.[1] From childhood man has an instinct for representation, and in this respect man differs from the other animals that he is far more imitative and learns his first lessons though imitating things.[1] Aristotle discusses representation in three ways: 1. the object: the symbol being represented; 2. the manner: the way the symbol is represented; 3. the means: the material that is used to represent it. The means of literary representation is language. An important part of representation is the relationship between what the material and what it represents. The questions arising from this are, "A stone may represent a man but how? And by what and by what agreement, does this understanding of the representation occur?"[1] One apprehends reality only through representations of reality, through texts, discourses, images: there is no such thing as direct or unmediated access to reality. But because one can see reality only through representation it does not follow that one does not see reality at all. Reality is always more extensive and complicated than any system of representation can comprehend, and we always sense that this is so-representation never "gets" reality, which is why human history has produced so many and changing ways of trying to get it.[7] Consequently, throughout the history of human culture, people have become dissatisfied with language's ability to express reality and as a result have developed new modes of representation. It is necessary to construct new ways of seeing reality, as people only know reality through representation.[7] From this arise the contrasting and alternate theories and representational modes of abstraction, realism and modernism, to name a few. |

歴史 ハドリアヌスの別荘のモザイクに描かれたギリシャの演劇用仮面 古代より、表現は文学・美学・記号論を理解する上で中心的な役割を果たしてきた。プラトンとアリストテレスは初期文学理論の重要人物であり、文学を単なる 表現の一形態と見なした[3]。例えばアリストテレスは、言語的・視覚的・音楽的といったあらゆる表現様式を、人間にとって自然なものと考えた。[4] したがって、人間を他の動物と区別するものは、記号を創造し操作する能力である。[5] アリストテレスは模倣(ミメーシス)を人間にとって自然なものと見なし、表現が人民の学習と世界における存在にとって必要不可欠であると考えた。[4] これに対しプラトンは、表現をより慎重に見ていた。彼は文学が人生の表現であることを認めつつも、表現が鑑賞者と現実の間に介入すると信じていた。これは 幻想の世界を生み出し、人を「現実のもの」から遠ざける。[6] したがってプラトンは、反社会的感情を助長したり悪を模倣したりする危険性があるため、表現は制御され監視されるべきだと考えた。[5] アリストテレスはさらに、表現は決定的に人間的な活動だと述べた。[1] 人間は幼少期から表現への本能を持ち、この点で他の動物とは異なり、はるかに模倣的であり、物事を模倣することで最初の教訓を学ぶのだ。[1] アリストテレスは表現を三つの観点から論じる: 1.対象:表現される象徴 2. 様式:象徴が表現される方法 3. 手段:表現に用いられる素材 文学的表現の手段は言語である。表現における重要な要素は、素材とそれが表現する対象との関係性だ。ここから生じる疑問は「石が人を表現しうるが、どうやって?そしてこの表現の理解は、何によって、いかなる合意によって生じるのか?」である[1]。 人は現実を、現実の表現、すなわちテキストや言説、イメージを通じてのみ把握する。現実への直接的・媒介なきアクセスなど存在しない。しかし現実を表現を 通してしか見られないからといって、現実を全く見ていないわけではない。現実は常に、いかなる表現体系も把握しうる範囲を超えて広大で複雑であり、我々は 常にそのことを感じ取っている——表現は決して現実を「捉えきれない」のだ。だからこそ人類の歴史は、現実を捉えようとする無数かつ変化に富んだ方法を産 み出してきたのである[7]。 したがって、人類文化の歴史を通じて、人々は言語が現実を表現する能力に不満を抱き、その結果として新たな表象様式を発展させてきた。人々が現実を表象を 通じてしか知ることができない以上、現実を見る新たな方法を構築する必要があるのだ[7]。ここから、抽象主義、写実主義、モダニズムといった対照的で代 替的な理論や表象様式が生まれるのである。 |

| Contemporary ideas about representation It is from Plato's caution that in the modern era many are aware of political and ideological issues and the influences of representations. It is impossible to divorce representations from culture and the society that produces them. In the contemporary world there exist restrictions on subject matter, limiting the kinds of representational signs allowed to be employed, as well as boundaries that limit the audience or viewers of particular representations. In motion picture rating systems, M and R rated films are an example of such restrictions, highlighting also society's attempt to restrict and modify representations to promote a certain set of ideologies and values. Despite these restrictions, representations still have the ability to take on a life of their own once in the public sphere, and can not be given a definitive or concrete meaning; as there will always be a gap between intention and realization, original and copy.[5] Consequently, for each of the above definitions there exists a process of communication and message sending and receiving. In such a system of communication and representations it is inevitable that potential problems may arise; misunderstandings, errors, and falsehoods. The accuracy of the representations can by no means be guaranteed, as they operate in a system of signs that can never work in isolation from other signs or cultural factors. For instance, the interpretation and reading of representations function in the context of a body of rules for interpreting, and within a society many of these codes or conventions are informally agreed upon and have been established over a number of years. Such understandings however, are not set in stone and may alter between times, places, peoples and contexts. How though, does this 'agreement' or understanding of representation occur? It has generally been agreed by semioticians that representational relationships can be categorised into three distinct headings: icon, symbol and index.[5] For instance objects and people do not have a constant meaning, but their meanings are fashioned by humans in the context of their culture, as they have the ability to make things mean or signify something.[6] Viewing representation in such a way focuses on understanding how language and systems of knowledge production work to create and circulate meanings. Representation is simply the process in which such meanings are constructed.[6] In much the same way as the post-structuralists, this approach to representation considers it as something larger than any one single representation. A similar perspective is viewing representation as part of a larger field, as W. J. T. Mitchell, saying, "…representation (in memory, in verbal descriptions, in images) not only 'mediates' our knowledge (of slavery and of many other things), but obstructs, fragments, and negates that knowledge"[8] and proposes a move away from the perspective that representations are merely "objects representing", towards a focus on the relationships and processes through which representations are produced, valued, viewed and exchanged. |

現代における表象に関する考え方 プラトンの警告から、現代では多くの人が政治的・思想的問題や表象の影響を認識している。表象を、それを生み出す文化や社会から切り離すことは不可能だ。 現代世界では、題材に対する制限が存在し、使用が許される表象記号の種類を制限している。また、特定の表象の観客や視聴者を制限する境界線も存在する。映 画レーティング制度におけるM指定やR指定の映画は、こうした制限の一例であり、特定のイデオロギーや価値観を推進するために表現を制限・修正しようとす る社会の試みも浮き彫りにしている。こうした制限にもかかわらず、表現は公の場に出ると独自の生命を帯びる可能性を依然として持ち、決定的あるいは具体的 な意味を与えることはできない。意図と実現、原本と複製の間には常に隔たりがあるからだ。[5] したがって、上記の定義のそれぞれには、コミュニケーションとメッセージの送受信プロセスが存在する。こうしたコミュニケーションと表象のシステムにおい ては、誤解、誤り、虚偽といった潜在的な問題が生じるのは避けられない。表象の正確性は決して保証され得ない。なぜならそれらは、他の記号や文化的要因か ら切り離して機能することのない記号体系の中で作用するからだ。例えば、表象の解釈や読解は、解釈のための規則体系という文脈の中で機能する。社会におい ては、こうした規範や慣習の多くが非公式に合意され、長年にわたって確立されてきた。しかし、こうした理解は不変ではなく、時代、場所、人々、文脈によっ て変化しうる。では、この表象に関する「合意」や理解はどのように生まれるのか。記号論者たちは概ね、表象関係を三つの明確なカテゴリーに分類できると認 めている:アイコン、シンボル、インデックスである。[5] 例えば物体や人民は不変の意味を持たず、その意味は文化の文脈において人間によって形成される。なぜなら人間には物事に意味や象徴性を与える能力があるか らだ。[6] このような観点から表現を見ることは、言語や知識生産のシステムが、どのように意味を創出し、流通させるかを理解することに焦点を当てる。表現とは、単に そのような意味が構築される過程である。[6] ポスト構造主義者たちと同様、この表現へのアプローチは、表現を単一の表現よりも大きなものと見なしている。W. J. T. ミッチェルが「… 表象(記憶、言語的記述、イメージにおける)は、私たちの知識(奴隷制やその他多くの事柄に関する)を「媒介」するだけでなく、その知識を妨害し、断片化 し、否定する」[8] と述べ、表象は単に「表現する対象」であるという視点から、表象が生産され、評価され、見られ、交換される関係やプロセスに焦点を当てる方向へと移行する ことを提案している。 |

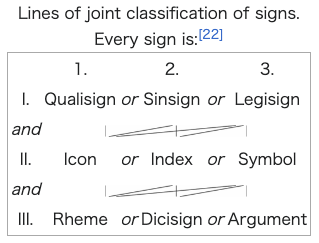

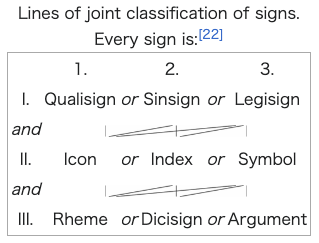

Peirce and representation Charles Sanders Peirce Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) was an innovative and accomplished logician, mathematician, and scientist, and founded philosophical pragmatism. Peirce's central ideas were focused on logic and representation. Semiotics and logic Peirce distinguished philosophical logic as logic per se from mathematics of logic. He regarded logic (per se) as part of philosophy, as a normative field following esthetics and ethics, as more basic than metaphysics,[9] and as the art of devising methods of research.[10] He argued that, more generally, as inference, "logic is rooted in the social principle", since inference depends on a standpoint that, in a sense, is unlimited.[11] Peirce held that logic is formal semiotic,[12] the formal study of signs in the broadest sense, not only signs that are artificial, linguistic, or symbolic, but also signs that are semblances or are indexical such as reactions. He held that "all this universe is perfused with signs, if it is not composed exclusively of signs",[13] along with their representational and inferential relations, interpretable by mind or quasi-mind (whatever works like a mind despite perhaps not actually being one);[14] the focus here is on sign action in general, not psychology, linguistics, or social studies). He argued that, since all thought takes time, "all thought is in signs"[15] and sign processes ("semiosis") and that the three irreducible elements of semiosis are (1) the sign (or representamen), (2) the (semiotic) object, the sign's subject matter, which the sign represents and which can be anything thinkable—quality, brute fact, or law—and even fictional (Prince Hamlet), and (3) the interpretant (or interpretant sign), which is the sign's meaning or ramification as formed into a kind of idea or effect that is a further sign, for example, a translation.[16] Even when a sign represents by a resemblance or factual connection independent of interpretation, the sign is a sign because it is at least potentially interpretable. A sign depends on its object in a way that enables (and, in a sense, determines) interpretation, forming an interpretant which, in turn, depends on the sign and on the object as the sign depends on the object and is thus a further sign, enabling and determining still further interpretation, further interpretants. That essentially triadic process is logically structured to perpetuate itself and is what defines sign, object, and interpretant. An object either (1) is immediate to a sign, and that is the object as represented in the sign, or (2) is a dynamic object, which is the object as it really is, on which the immediate object is founded. Usually, an object in question, such as Hamlet or the planet Neptune, is a special or partial object. A sign's total object is the object's universe of discourse, the totality of things in that world to which one attributes the object. An interpretant is either (1) immediate to a sign, for example a word's usual meaning, a kind of interpretive quality or possibility present in the sign, or (2) dynamic, an actual interpretant, for example a state of agitation, or (3) final or normal, a question's true settlement, which would be reached if thought or inquiry were pushed far enough, a kind of norm or ideal end with which any actual interpretant may, at most, coincide. Peirce said that, in order to know to what a sign refers, the mind needs some sort of experience of the sign's object, experience outside, and collateral to, the given sign or sign system. In that context he spoke of collateral experience, collateral observation, collateral acquaintance, all in much the same terms.[17] For example, art work can exploit both the richness and the limits of the audience's experience; a novelist, in disguising a roman à clef, counts on the typical reader's lack of personal experience with the actual individual people portrayed. Then the reader refers the signs and interpretants in a general way to an object or objects of the kind that is represented (intentionally or otherwise) by the novel. In all cases, the object (be it a quality or fact or law or even fictional) determines the sign to an interpretant through one's collateral experience with the object, collateral experience in which the object is newly found or from which it is recalled, even if it is experience with an object of imagination as called into being by the sign, as can happen not only in fiction but in theories and mathematics, all of which can involve mental experimentation with the object under specifiable rules and constraints. Through collateral experience even a sign that consists in a chance semblance of an absent object is determined by that object. Peirce held that logic has three main parts: Speculative grammar,[18] on meaningfulness, conditions for meaning. Study of significatory elements and combinations. Logical critic,[19] on validity, conditions for true representation. Critique of arguments in their various distinct modes. Speculative rhetoric, or methodeutic,[20] on conditions for determining interpretations. Methodology of inquiry in its mutually interacting modes. 1. Speculative Grammar. By this, Peirce means discovering relations among questions of how signs can be meaningful and of what kinds of signs there are, how they combine, and how some embody or incorporate others. Within this broad area, Peirce developed three interlocked universal trichotomies of signs, depending respectively on (1) the sign itself, (2) how the sign stands for its object, and (3) how the sign stands for its object to its interpretant. Each trichotomy is divided according to the phenomenological category involved: Firstness (quality of feeling, essentially monadic), secondness (reaction or resistance, essentially dyadic), or thirdness (representation or mediation, essentially triadic).[21] Qualisigns, sinsigns, and legisigns. Every sign is either (qualisign) a quality or possibility, or (sinsign) an actual individual thing, fact, event, state, etc., or (legisign) a norm, habit, rule, law. Icons, indices, and symbols. Every sign refers either (icon) through similarity to its object, or (index) through factual connection to its object, or (symbol) through interpretive habit or norm of reference to its object. Rhemes, dicisigns, and arguments. Every sign is interpreted either as (rheme) term-like, standing for its object in respect of quality, or as (dicisign) proposition-like, standing for its object in respect of fact, or as (argument) argumentative, standing for its object in respect of habit or law. This is the trichotomy of all signs as building blocks of inference. |

パースと表象 チャールズ・サンダース・パース チャールズ・サンダース・パース(1839–1914)は革新的な論理学者、数学者、科学者であり、哲学的実用主義の創始者である。パースの中心思想は論理学と表象に焦点を当てていた。 記号論と論理学 ピアースは哲学的論理学を、論理学そのものとして数学的論理学と区別した。彼は論理学(それ自体)を哲学の一部、美学や倫理学に続く規範的領域、形而上学 よりも基礎的なもの[9]、そして研究方法の考案術[10]と見なした。より一般的には、推論として「論理学は社会的原理に根ざしている」と主張した。な ぜなら推論はある意味で無制限な立場に依存するからだ。[11] パースは、論理学は形式記号論[12]であると主張した。これは最も広い意味での記号の形式的研究であり、人工的・言語的・象徴的な記号だけでなく、反応 のような表象や指標的記号も含まれる。彼は「この宇宙全体が記号に浸透している、あるいは記号のみで構成されている」[13]と主張し、それらは心あるい は準心(実際の心ではないかもしれないが心のように機能するあらゆるもの)によって解釈可能な表象関係と推論関係を持つ[14]。ここで焦点となるのは心 理学、言語学、社会科学ではなく、一般的な記号作用である。 彼は、あらゆる思考には時間がかかるため、「あらゆる思考は記号の中にある」[15]と記号過程(「記号作用」)を主張した。そして記号作用の三つの還元 不可能な要素は、(1)記号(または表象)、 (2) 記号が表象する対象(記号論的対象)であり、これは思考可能なあらゆるもの―性質、事実、法則―であり、架空のものでさえあり得る(ハムレット王子)、 (3) 解釈項(解釈項記号)であり、これは記号の意味や帰結が、例えば翻訳のようなさらなる記号となる一種の観念や効果として形成されたものである。[16] たとえ記号が解釈とは独立した類似性や事実的関連によって表象する場合でも、記号は少なくとも潜在的に解釈可能であるゆえに記号である。記号はその対象に 依存するが、その依存は解釈を可能にし(ある意味で決定し)、解釈項を形成する。解釈項はさらに記号と対象に依存し、記号が対象に依存するのと同じ構造を 持つため、さらなる記号となり、さらなる解釈と解釈項を可能にし決定する。この本質的に三項的な過程は、自己永続化を論理的に構造化しており、記号・対 象・解釈項を定義するものである。 対象は、(1) 記号に対して直接的なものであり、それは記号に表象される対象であるか、(2) 動的な対象であり、それは直接対象が基盤とする、実在する対象そのものである。通常、問題となる対象物(ハムレットや海王星など)は特殊対象あるいは部分 対象である。記号の総体対象とは、対象が帰属される世界における事物の総体、すなわち対象の言説領域である。解釈項は次のいずれかである:(1) 記号に直接結びつくもの、例えば言葉の通常の意味、記号に内在する解釈的性質や可能性、(2) 動的なもの、実際の解釈項、例えば興奮状態、(3) 最終的または正常な解釈項、思考や探究を十分に推し進めた場合に到達する質問の真の解決、 実際の解釈対象がせいぜい一致し得る規範や理想的な終着点のようなものだ。 パースは、記号が何を指すかを知るためには、心は記号の対象に関する何らかの経験、すなわち与えられた記号や記号体系の外側で、それに付随する経験が必要 だと述べた。その文脈で彼は、付随的経験、付随的観察、付随的知覚といった用語をほぼ同義的に用いた。[17] 例えば芸術作品は、観客の経験の豊かさと限界の両方を利用できる。小説家が実在の「人々」をモデルにした小説を偽装する際、典型的な読者が描かれた「人 々」と個人的な経験を持たないことを頼りにする。すると読者は、小説が(意図的か否か)表現する種類の対象物に対して、記号と解釈対象を一般的な形で参照 する。いずれの場合も、 対象(それが性質であれ事実であれ法則であれ、あるいは架空のものであれ)は、対象との付随的経験を通じて記号を解釈対象に決定する。この付随的経験にお いて対象は新たに発見されるか、あるいは想起される。たとえそれが記号によって呼び起こされる想像上の対象との経験であっても同様である。これは虚構だけ でなく理論や数学においても起こりうる。これら全ては、特定可能な規則と制約のもとで対象を用いた精神的な実験を伴う可能性がある。付随的経験を通じて、 不在の対象との偶然の一致から成る記号でさえ、その対象によって決定されるのである。 パースは論理学が三つの主要部分から成ると主張した: 1. 観念論的文法[18]:意味性、意味の条件に関するもの。意味形成要素と組み合わせの研究。 2. 論理的批判[19]:妥当性、真の表象の条件について。様々な異なる様式における議論の批判。 3. 推論修辞学、あるいは方法論[20]:解釈を決定する条件について。相互に作用し合う様式における探究の方法論。 1. 推論文法。ここでパースが意味するのは、記号が如何にして意味を持つか、如何なる種類の記号が存在するか、如何に結合するか、如何に他を体現・包含するか という諸問題間の関係を発見することである。この広範な領域において、パースは三つの相互に連関する普遍的記号三元分類を発展させた。それぞれ(1)記号 自体、(2)記号が対象を如何に表すか、(3)記号が解釈対象に対して如何にその対象を表すか、に依存する。各三区分は、関わる現象学的カテゴリーに従っ て分けられる:第一性(感覚の質、本質的に単項的)、第二性(反応または抵抗、本質的に二項的)、第三性(表象または媒介、本質的に三項的)。[21] 1. 質的記号、実的記号、規範的記号。あらゆる記号は、(質的記号) 性質または可能性、(実的記号) 実際の個別的事物・事実・事象・状態など、あるいは(規範的記号) 規範・習慣・規則・法である。 2. アイコン、インデックス、シンボル。あらゆる記号は、対象への類似性による(アイコン)、対象への事実上の関連性による(インデックス)、あるいは対象への解釈的習慣や参照規範による(シンボル)のいずれかで対象を指し示す。 3. レーム、ディケサイン、および論証。あらゆる記号は、(レーム) 性質に関して対象を表す用語的解釈、(ディケサイン) 事実に関して対象を表す命題的解釈、あるいは(論証) 習慣や法則に関して対象を表す論証的解釈のいずれかとして解釈される。これが推論の構成要素としての全記号の三分類である。 |

| Lines of joint classification of signs. Every sign is:  Some (not all) sign classes from different trichotomies intersect each other. For example, a qualisign is always an icon, and is never an index or a symbol. He held that there were only ten classes of signs logically definable through those three universal trichotomies.[23] He thought that there were further such universal trichotomies as well. Also, some signs need other signs in order to be embodied. For example, a legisign (also called a type), such as the word "the," needs to be embodied in a sinsign (also called a token), for example an individual instance of the word "the", in order to be expressed. Another form of combination is attachment or incorporation: an index may be attached to, or incorporated by, an icon or a symbol. Peirce called an icon apart from a label, legend, or other index attached to it, a "hypoicon", and divided the hypoicon into three classes: (a) the image, which depends on a simple quality; (b) the diagram, whose internal relations, mainly dyadic or so taken, represent by analogy the relations in something; and (c) the metaphor, which represents the representative character of a sign by representing a parallelism in something else.[24] A diagram can be geometric, or can consist in an array of algebraic expressions, or even in the common form "All __ is ___" which is subjectable, like any diagram, to logical or mathematical transformations. |

記号の共同分類の線。 あらゆる記号は:  異なる三区分に属する記号のクラスの中には(全てではないが)互いに交差するものがある。例えば、質的記号は常に図像であり、指示記号でも記号でも決して ない。彼は、これら三つの普遍的な三区分を通じて論理的に定義可能な記号のクラスは十種類のみだと主張した[23]。さらに、そのような普遍的な三区分が 他にも存在すると考えていた。また、一部の記号は具現化するために他の記号を必要とする。例えば「the」という単語のような記号類(類型とも呼ばれる) は、表現されるために「the」という単語の個々の使用例のような記号現(トークンとも呼ばれる)に具現化される必要がある。別の結合形態として付着また は組み込みがある:指示記号は表象記号や記号に付着したり組み込まれたりする。 パースは、ラベルや説明文、その他の付随する指標から切り離されたアイコンを「仮指標(hypoicon)」と呼び、これを三つのクラスに分類した: (a) 単純な性質に依存する「イメージ(image)」、 (b) 図式。主に二項関係(あるいはそう見なされる関係)の内部関係が、類推によって何かの関係を表す。(c) 隠喩。他の何かにおける並行性を表すことで、記号の代表性を表す。[24] 図式は幾何学的でもよいし、代数式の配列から成ってもよい。あるいは「すべての__は___である」という一般的な形式であってもよく、あらゆる図式と同 様に論理的・数学的変換が可能である。 |

| 2.

Logical critic or Logic Proper. That is how Peirce refers to logic in

the everyday sense. Its main objective, for Peirce, is to classify

arguments and determine the validity and force of each kind.[19] He

sees three main modes: abductive inference (guessing, inference to a

hypothetical explanation); deduction; and induction. A work of art may

embody an inference process and be an argument without being an

explicit argumentation. That is the difference, for example, between

most of War and Peace and its final section. 3. Speculative rhetoric or methodeutic. For Peirce this is the theory of effective use of signs in investigations, expositions, and applications of truth. Here Peirce coincides with Morris's notion of pragmatics, in his interpretation of this term. He also called it "methodeutic", in that it is the analysis of the methods used in inquiry.[20] |

2.

論理的批判、あるいは純粋論理。これがパースが日常的な意味で論理を指す呼称である。パースにとってその主目的は、議論を分類し、各種類の妥当性と説得力

を決定することにある[19]。彼は三つの主要な推論様式を認めている:アブダクティブ推論(推測、仮説的説明への推論)、演繹、帰納である。芸術作品

は、明示的な論証ではなくとも、推論過程を体現し、一つの議論となり得る。例えば、『戦争と平和』の大部分と最終章とは異なる。 3. 推論修辞学または方法論。パースにとってこれは、真実の探究・説明・応用における記号の効果的利用の理論である。ここでパースは、モリスが提唱した「実用 論」の概念と解釈において一致する。彼はこれを「方法論」とも呼んだ。探究に用いられる方法の分析であるからである。[20] |

| Using signs and objects Peirce concluded that there are three ways in which signs represent objects. They underlie his most widely known trichotomy of signs: Icon Index Symbol[25] Icon This term refers to signs that represent by resemblance, such as portraits and some paintings though they can also be natural or mathematical. Iconicity is independent of actual connection, even if it occurs because of actual connection. An icon is or embodies a possibility, insofar as its object need not actually exist. A photograph is regarded as an icon because of its resemblance to its object, but is regarded as an index (with icon attached) because of its actual connection to its object. Likewise, with a portrait painted from life. An icon's resemblance is objective and independent of interpretation, but is relative to some mode of apprehension such as sight. An icon need not be sensory; anything can serve as an icon, for example a streamlined argument (itself a complex symbol) is often used as an icon for an argument (another symbol) bristling with particulars. Index Peirce explains that an index is a sign that compels attention through a connection of fact, often through cause and effect. For example, if we see smoke we conclude that it is the effect of a cause – fire. It is an index if the connection is factual regardless of resemblance or interpretation. Peirce usually considered personal names and demonstratives such as the word "this" to be indices, for although as words they depend on interpretation, they are indices in depending on the requisite factual relation to their individual objects. A personal name has an actual historical connection, often recorded on a birth certificate, to its named object; the word "this" is like the pointing of a finger. Symbol Peirce treats symbols as habits or norms of reference and meaning. Symbols can be natural, cultural, or abstract and logical. They depend as signs on how they will be interpreted, and lack or have lost dependence on resemblance and actual, indexical connection to their represented objects, though the symbol's individual embodiment is an index to your experience of its represented object. Symbols are instantiated by specialized indexical sinsigns. A proposition, considered apart from its expression in a particular language, is already a symbol, but many symbols draw from what is socially accepted and culturally agreed upon. Conventional symbols such as "horse" and caballo, which prescribe qualities of sound or appearance for their instances (for example, individual instances of the word "horse" on the page) are based on what amounts to arbitrary stipulation.[5] Such a symbol uses what is already known and accepted within our society to give meaning. This can be both in spoken and written language. For example, we can call a large metal object with four wheels, four doors, an engine and seats a "car" because such a term is agreed upon within our culture and it allows us to communicate. In much the same way, as a society with a common set of understandings regarding language and signs, we can also write the word "car" and in the context of Australia and other English speaking nations, know what it symbolises and is trying to represent.[26] |

記号と対象物の使用 パースは、記号が対象物を表す方法が三つあると結論づけた。これらは彼の最も広く知られる記号の三分類の基礎となる: 図像 指示 象徴[25] 図像 この用語は、肖像画や一部の絵画のように類似性によって表す記号を指すが、自然や数学的なものも含まれる。図像性は実際の関連性とは独立しており、たとえ 実際の関連性によって生じた場合でも同様である。イコンは可能性そのものである。対象が実際に存在しなくてもよいからだ。写真は対象に似ているためイコン と見なされるが、対象との実際の関連性があるため指標(付随するイコンとして)と見なされる。実物から描かれた肖像画も同様である。イコンの類似性は客観 的であり解釈に依存しないが、視覚などの認識様式には依存する。アイコンは感覚的である必要はない。あらゆるものがアイコンとなり得る。例えば、流線型の 議論(それ自体が複雑な記号)は、細部がひしめく議論(別の記号)のアイコンとしてしばしば用いられる。 指標 パースは、指標とは事実の関連性(しばしば因果関係)を通じて注意を喚起する記号だと説明する。例えば煙を見れば、それが原因(火)の結果だと結論づけ る。類似性や解釈に関係なく、事実上の関連性があればそれは指標である。パースは通常、個人名や「これ」といった指示語を指標と見なした。言葉として解釈 に依存するものの、個々の対象との必要な事実上の関係に依存する点で指標だからだ。個人名は出生証明書に記録される実際の歴史的関連性を対象と持つ。「こ れ」という言葉は指さしに似ている。 記号 パースは記号を、参照と意味の習慣または規範として扱う。記号は自然的、文化的、あるいは抽象的・論理的である。記号は、それがどのように解釈されるかに 依存する記号であり、表象対象との類似性や実際の指標的関連性に依存しない、あるいは依存を失っている。ただし、記号の個々の具体化は、表象対象に対する あなたの経験への指標である。記号は、特殊な指標的記号によって具体化される。命題は、特定の言語での表現から切り離して考えれば、すでに記号である。し かし多くの記号は、社会的に受け入れられ文化的に合意されたものに依拠する。「馬」や「caballo」のような慣習的記号は、その実例(例えば紙面上の 「馬」という単語の個々の実例)に音や外観の特性を規定するが、これは実質的に恣意的な規定に基づいている。[5] この種の記号は、社会内で既に知られ受け入れられているものを用いて意味を与える。これは口頭言語と文字言語の両方で成り立つ。 例えば、四輪と四つのドア、エンジンと座席を備えた大型金属物体を「車」と呼べるのは、この用語が文化内で合意され、意思疎通を可能にするからだ。同様 に、言語と記号に関する共通の理解を持つ社会として、我々は「車」という文字を書き、オーストラリアやその他の英語speaking国民の文脈において、 それが何を象徴し、何を表そうとしているのかを理解できるのである。[26] |

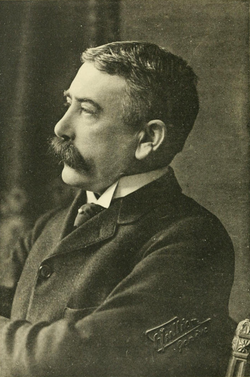

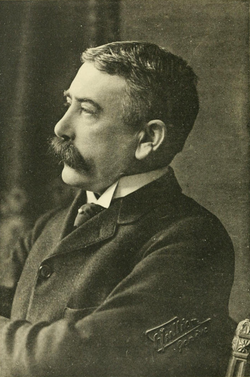

Saussure and representation Ferdinand de Saussure Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913) played a major role in the development of semiotics with his argument that language is a system of signs that needs to be understood in order to fully understand the process of linguistics.[27] The study of semiotics examines the signs and types of representation that humans use to express feelings, ideas, thoughts and ideologies.[28] Although semiotics is often used in the form of textual analysis it also involves the study of representation and the processes involved with representation. The process of representation is characterised by using signs that we recall mentally or phonetically to comprehend the world.[29] Saussure says before a human can use the word "tree" she or he has to envision the mental concept of a tree. Two things are fundamental to the study of signs:[30] 1. The signified: a mental concept, and 2. The signifier: the verbal manifestation, the sequence of letters or sounds, the linguistic realisation. The signifier is the word or sound; the signified is the representation. Saussure points out that signs: Are arbitrary: There is no link between the signifier and the signified Are relational: We understand we take on meaning in relation to other words. Such as we understand "up" in relation to "down" or a dog in relation to other animals, such as a cat. constitute our world – "You cannot get outside of language. We exist inside a system of signs".[30] Saussure suggests that the meaning of a sign is arbitrary, in effect; there is no link between the signifier and the signified.[31] The signifier is the word or the sound of the word and the signified is the representation of the word or sound. For example, when referring to the term "sister" (signifier) a person from an English speaking country such as Australia, may associate that term as representing someone in their family who is female and born to the same parents (signified). An Aboriginal Australian may associate the term "sister" to represent a close friend that they have a bond with. This means that the representation of a signifier depends completely upon a person's cultural, linguistic and social background. Saussure argues that if words or sounds were simply labels for existing things in the world, translation from one language or culture to another would be easy, it is the fact that this can be extremely difficult that suggests that words trigger a representation of an object or thought depending on the person that is representing the signifier.[32] The signified triggered from the representation of a signifier in one particular language do not necessarily represent the same signified in another language. Even within one particular language many words refer to the same thing but represent different people's interpretations of it. A person may refer to a particular place as their "work" whereas someone else represents the same signifier as their "favorite restaurant". This can also be subject to historical changes in both the signifier and the way objects are signified. Saussure claims that an imperative function of all written languages and alphabetic systems is to "represent" spoken language.[33] Most languages do not have writing systems that represent the phonemic sounds they make. For example, in English the written letter "a" represents different phonetic sounds depending on which word it is written in. The letter "a" has a different sound in the word in each of the following words, "apple", "gate", "margarine" and "beat", therefore, how is a person unaware of the phonemic sounds, able to pronounce the word properly by simply looking at alphabetic spelling. The way the word is represented on paper is not always the way the word would be represented phonetically. This leads to common misrepresentations of the phonemic sounds of speech and suggests that the writing system does not properly represent the true nature of the pronunciation of words. |

ソシュールと表象 フェルディナン・ド・ソシュール スイスの言語学者フェルディナン・ド・ソシュール(1857–1913)は、言語学のプロセスを完全に理解するためには、言語が記号の体系であることを理 解する必要があるという主張により、記号論の発展に重要な役割を果たした。[27] 記号論の研究は、人間が感情、思想、思考、イデオロギーを表現するために用いる記号と表象の類型を考察するものである。[28] 記号論はしばしばテクスト分析の形で用いられるが、表象と表象に関わる過程の研究も含まれる。 表象の過程は、私たちが精神的に、あるいは音声的に想起する記号を用いて世界を理解するという特徴を持つ。[29] ソシュールによれば、人間が「木」という言葉を使う前に、まず「木」という概念を心に描かなければならない。 記号の研究において二つの要素が基本となる:[30] 1. 表象(シニフィエ):心の概念 2. 表象(シニフィアン):言語的表現、文字や音の配列、言語的実現 表象は言葉や音であり、表象されるものは表象そのものである。 ソシュールは記号について次のように指摘する: 恣意的である:表象と表象されるものとの間には必然的な結びつきがない 関係的である:我々は他の言葉との関係性において意味を理解する。例えば「上」は「下」との関係で、「犬」は猫などの他の動物との関係で理解される。 私たちの世界を構成する——「言語の外側には出られない。我々は記号体系の中に存在する」[30] ソシュールは、記号の意味は実質的に恣意的であり、表象と被表象の間に結びつきは存在しないと示唆する[31]。表象とは言葉やその音であり、被表象とは 言葉や音の表象である。例えば「姉」という語(シニフィアン)について、オーストラリアのような英語圏の国の人格は、同じ親から生まれた女性家族成員(シ ニフィエ)を連想するかもしれない。一方、オーストラリア先住民は「姉」という語を、絆のある親しい友人を表すものと連想するかもしれない。これは、表象 が完全に個人の文化的・言語的・社会的背景に依存することを意味する。 ソシュールは、言葉や音が単に世界の既存物へのラベルならば、言語や文化間の翻訳は容易だと論じる。しかし実際には翻訳が極めて困難な事実こそが、言葉が 表象を喚起する対象や思考は、その表象を行う人格によって異なることを示唆している。[32] ある言語における記号の表象から喚起される意味内容は、別の言語では必ずしも同じ意味内容を表さない。同一言語内でも、多くの言葉が同じものを指しなが ら、人々の異なる解釈を表すことがある。ある者は特定の場所を「職場」と呼ぶ一方、別の者は同じ表象を「お気に入りのレストラン」と解釈する。これは、表 象と対象の表象方法の両方における歴史的変化の影響も受ける。 ソシュールは、全ての文字言語とアルファベット体系の必須機能は「話し言葉を表象すること」だと主張している。[33] ほとんどの言語は、発音される音素を正確に表す文字体系を持っていない。例えば英語では、文字「a」は書かれる単語によって異なる音を表す。「a」という 文字は、「apple」「gate」「margarine」「beat」という各単語の中で異なる音を持つ。では、音素的な音を知らない人格が、単にアル ファベット表記を見ただけで、どうやってその単語を正しく発音できるのか。言葉が紙に表される方法は、必ずしもその言葉が音声学的に表される方法とは一致 しない。これは話し言葉の音素的な発音の一般的な誤った表現につながり、文字体系が言葉の発音の真の性質を適切に表していないことを示唆している。 |

| Aspectism Conceptual art Cultural artifact Culture theory Figurative art Media influence Mimesis Painting Program music Realism (arts) Representative realism Social representation Symbol Western painting Work of art |

アスペクト主義 コンセプチュアル・アート 文化的産物 文化理論 具象芸術 メディアの影響 ミメーシス 絵画 プログラム音楽 リアリズム(芸術) 代表的リアリズム 社会的表象 象徴 西洋絵画 芸術作品 |

1. Mitchell, W. 1995, "Representation", in F Lentricchia & T McLaughlin (eds), Critical Terms for Literary Study, 2nd edn, University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2. O'Shaughnessy, M & Stadler J, Media and society: an introduction, 3rd edn, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2005 3. Childers J (ed.), Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism, Columbia University Press, New York, 1995 4. <Vukcevich, M 2002, "Representation", The University of Chicago, viewed 7 April 2006 5. Mitchell, W, "Representation", in F Lentricchia & T McLaughlin (eds), Critical Terms for Literary Study, University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1990 6. Hall, S (ed.), Cultural Representations and Signifying Practice, Open University Press, London, 1997. ISBN 978-0761954323 7. Dryer 1993, cited in O’Shaughnessy & Stadler 2005 8. Mitchell, W, Picture Theory, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1994 9. On his classifications, see Peirce, C.S. (1903), CP 1.180–202 Eprint Archived 2011-11-05 at the Wayback Machine and (1906) "The Basis of Pragmaticism" in The Essential Peirce 2:372–3. For the relevant quotes, see "Philosophy" and "Logic" at Commens Dictionary of Peirce's Terms, Bergman and Paavola, editors, U. of Helsinki. 10. Peirce, C.S., 1882, "Introductory Lecture on the Study of Logic" delivered September 1882, Johns Hopkins University Circulars, vol. 2, no. 19, pp. 11–12, November 1892, Google Book Search Eprint. Reprinted in Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce v. 7, paragraphs 59–76, The Essential Peirce 1:214–214; Writings of Charles S. Peirce 4:378–382. 11. Peirce, C.S. (1878) "The Doctrine of Chances", Popular Science Monthly, v. 12, pp. 604–615, 1878, reprinted in Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, v. 2, paragraphs 645–668, Writings of Charles S. Peirce 3:276–290, and The Essential Peirce 1:142–154. "...death makes the number of our risks, the number of our inferences, finite, and so makes their mean result uncertain. The very idea of probability and of reasoning rests on the assumption that this number is indefinitely great. .... ...logicality inexorably requires that our interests shall not be limited. .... Logic is rooted in the social principle." 12. Peirce, C. S. (written 1902), "MS L75: Logic, Regarded As Semeiotic (The Carnegie application of 1902): Version 1: An Integrated Reconstruction", Joseph Ransdell, ed., Arisbe, see Memoir 12. 13. Peirce, C.S., The Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, v. 5, paragraph 448 footnote, from "The Basis of Pragmaticism" in 1906. 14. See "Quasi-Mind" at the Commens Dictionary of Peirce's Terms, Mats Bergman and Sami Paavola, eds., University of Helsinki. 15. Peirce, C.S. (1868), "Questions Concerning Certain Faculties Claimed for Man" (Arisbe Eprint), Journal of Speculative Philosophy vol. 2, pp. 103–114. Reprinted (Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, v. 5, paragraphs 213–263, the quote is from paragraph 253). 16. For Peirce's definitions of semiosis, sign, representamen, object, interpretant, see the Commens Dictionary of Peirce's Terms. 17. Ten quotes on collateral observation from Peirce provided by Professor Joseph Ransdell can be viewed here. Also see pp. 404–409 in "Pragmatism" by Peirce in The Essential Peirce v. 2. 18. See "Grammar: Speculative" in Commens Dictionary of Peirce's Terms. 19. See "Critic" in Commens Dictionary of Peirce's Terms. 20. See "Methodeutic" in Commens Dictionary of Peirce's Terms. 21. "Categories, Cenopythagorean Categories", Commens Dictionary of Peirce's Terms, Mats Bergman and Sami Paavola, editors, University of Helsinki. 22. Peirce (1903 MS), "Nomenclature and Divisions of Triadic Relations, as Far as They Are Determined", under other titles in Collected Papers (CP) v. 2, paragraphs 233–272, and reprinted under the original title in Essential Peirce (EP) v. 2, pp. 289–299. Also see image of MS 339 (August 7, 1904) supplied to peirce-l by Bernard Morand of the Institut Universitaire de Technologie (France), Département Informatique. 23. See Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, v. 2, paragraphs 254–263, reprinted in Philosophical Writings of Peirce pp. 115–118, and in The Essential Peirce v. 2, pp. 294–296. 24. On image, diagram, and metaphor, see "Hypoicon" in the Commens Dictionary of Peirce's Terms. 25. For Peirce's definitions of icon, index, symbol, and related terms, see the Commens Dictionary of Peirce's Terms 26. Dupriez, B, A Dictionary of Literary Devices, University of Toronto Press, Canada, 1991. 27. Culler, J 1976, Saussure, Fontana Modern Masters, Britain, 1976. 28. Ryder, M, Semiotics: Language and Culture, 2004 viewed 6 April 2006 see link below 29. Klarer, M, An Introduction to Literary Studies, Routledge, London, 1998. 30. Barry, P, Beginning Theory: an Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory, Manchester University Press, Great Britain, 2002. 31. Holdcroft 1991 no details 32. Chandler, D, Semiotics for Beginners: Modality and representation, viewed 8 April 2006 33. Arnason, D, Reference material, 2006, viewed 12 April 2006 |

1. ミッチェル、W. 1995、「表現」、『文学研究のための批判用語集』F Lentricchia & T McLaughlin (編)、第 2 版、シカゴ大学出版局、シカゴ 2. O'Shaughnessy、M & Stadler J、『メディアと社会:入門』第 3 版、オックスフォード大学出版局、サウスメルボルン、2005 3. チャイルダーズ J (編)、『コロンビア現代文学・文化批評辞典』、コロンビア大学出版、ニューヨーク、1995年 4. <Vukcevich, M 2002, 「表現」、シカゴ大学、2006年4月7日閲覧 5. ミッチェル、W、「表現」、F Lentricchia & T McLaughlin (編)、『文学研究のための批判用語』、シカゴ大学出版局、シカゴ、1990年 6. ホール、S (編)、『文化的表現と意味化の実践』、オープン大学出版局、ロンドン、1997年。ISBN 978-0761954323 7. ドライヤー 1993、オショーネシー&スタドラー 2005 で引用 8. ミッチェル、W、『ピクチャー理論』、シカゴ大学出版局、シカゴ、1994 9. 彼の分類については、パース, C.S. (1903), CP 1.180–202 Eprint Archived 2011-11-05 at the Wayback Machine および (1906) 「The Basis of Pragmaticism」 in The Essential Peirce 2:372–3 を参照のこと。関連する引用については、Commens Dictionary of パース's Terms(ベルクマンとパーヴォラ編、ヘルシンキ大学)の「Philosophy」および「Logic」を参照のこと. 10. パース、C.S.、1882年、「論理学の研究に関する入門講義」、1882年9月発表、ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学回覧、第2巻、第19号、11-12 ページ、1892年11月、Googleブック検索Eprint。『チャールズ・サンダース・パース論文集』第 7 巻、59-76 段落、『The Essential Peirce』1:214-214、および『Writings of Charles S. Peirce』4:378-382 に再掲載. 11. パース、C.S. (1878) 「確率の教義」、Popular Science Monthly、v. 12、 pp. 604–615, 1878, チャールズ・サンダース・パース論文集 第2巻, 段落645–668, チャールズ・S・パース著作集 第3巻:276–290, 及び パースの要諦 第1巻:142–154 に再録. 「…死は我々のリスクの数、推論の数を有限とし、それゆえそれらの平均結果を不確実にする。確率と推論という概念そのものが、この数が無限に大きいという 仮定に立脚している。……論理性は容赦なく、我々の関心が制限されてはならないと要求する。…論理は社会的原理に根ざしている。」 12. パース, C. S. (1902年執筆), 「MS L75: 記号論的観点からの論理学 (1902年カーネギー申請書): バージョン1: 統合的再構築」, ジョセフ・ランスデル編, 『アリスベ』, メモワール12参照。 13. チャールズ・S・パース『チャールズ・サンダース・パース論文集』第5巻、448段落脚注、1906年「実用主義の基礎」より。 14. ヘルシンキ大学編『パース用語共通語辞典』の「準精神」の項を参照。 15. パース、C.S. (1868)、「人間に帰せられる特定の能力に関する疑問」(Arisbe Eprint)、『思索哲学ジャーナル』第2巻、103–114頁。再版(『チャールズ・サンダース・パース論文集』第5巻、パラグラフ213–263、 引用箇所はパラグラフ253)。 16. パースによるセミオシス、記号、表象、対象、解釈項の定義については、ピアース用語のコメンズ辞典を参照せよ。 17. ジョセフ・ランスデル教授提供のパースによる付随的観察に関する10の引用はここで閲覧可能。また『パース要集』第2巻所収「実用主義」404–409頁も参照。 18. 『パース用語コメンズ辞典』の「文法:思弁的」を参照。 19. 『コメンズ・パース用語辞典』の「批評家」の項を参照せよ。 20. 『コメンズ・パース用語辞典』の「方法論」の項を参照せよ。 21. 「範疇、セノピタゴラス的範疇」、『コメンズ・パース用語辞典』、マツ・ベルグマン及びサミ・パーヴォラ編、ヘルシンキ大学。 22. パース(1903年原稿)「三項関係の名付けと区分、確定されている範囲において」。『論文集』(CP)第2巻、段落233–272に他の題名で収録。原 題で『ピアース要約』(EP)第2巻、289–299頁に再録。また、フランス国立技術大学(Institut Universitaire de Technologie)情報科学部ベルナール・モランがパース-lに提供したMS 339(1904年8月7日)の画像も参照のこと。 23. 『チャールズ・サンダース・パース論文集』第2巻、パラグラフ254–263を参照。再版は『パース哲学著作集』115–118頁、『パース論文集要約版』第2巻294–296頁。 24. イメージ、図式、隠喩については、『パース用語コメンズ辞典』の「Hypoicon」の項を参照せよ。 25. パースによるアイコン、インデックス、シンボル及び関連用語の定義については、『パース用語コメンズ辞典』を参照せよ。 26. Dupriez, B, A Dictionary of Literary Devices, University of Toronto Press, Canada, 1991. 27. カラー, J 1976, 『ソシュール』, フォンタナ・モダン・マスターズ, 英国, 1976. 28. ライダー, M, 『記号論:言語と文化』, 2004年, 2006年4月6日閲覧, 下記リンク参照 29. クララー, M, 『文学研究入門』, ラウトレッジ, ロンドン, 1998. 30. バリー, P, 『理論入門:文学・文化理論概説』、マンチェスター大学出版局、英国、2002年。 31. ホールドクロフト 1991年 詳細不明 32. チャンドラー、D、『初心者のための記号論:様態と表象』、2006年4月8日閲覧 33. アルナソン、D、『参考資料』、2006年、2006年4月12日閲覧 |

| References Arnason, D, Semiotics: the system of signs (via the Wayback Machine) Baldick, C, "New historicism", in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms, 1996, viewed 8 April 2006 [1] Barry, P, Beginning Theory: an Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory, Manchester University Press, Great Britain, 2002. Burch, R 2005, "Charles Sanders Peirce", in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, viewed 24 April 2006 [2]. Chandler, D, Semiotics for Beginners: Modality and Representation, 2001, viewed 8 April 2006 [3]. Childers J. (ed.), Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism, Columbia University Press, New York, 1995. Concise Routledge, Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, Routledge, London, 1999. Culler, J., Saussure, Fontana Modern Masters, Britain, 1976. Dupriez, B, A Dictionary of Literary Devices, University of Toronto Press, Canada 1991. Fuery, P & Mansfield N, Cultural Studies and Critical Theory, Oxford University Press, Australia, 2005. (ISBN 978-0-19-551294-6) Hall, S (ed.), Cultural Representations and Signifying Practice, Open University Press, London, 1997. Holder, D, Saussure – Signs, System, and Arbitrariness, Cambridge, Australia, 1991. Lentricchia, F. & McLaughlin, T (eds.), Critical Terms for Literary Study, University of Chicago Press, London, 1990. Klarer, M, An Introduction to Literary Studies, Routledge, London, 1998. Mitchell, W, "Representation", in F Lentricchia & T McLaughlin (eds), Critical Terms for Literary Study, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1990. Mitchell, W, "Representation", in F Lentricchia & T McLaughlin (eds), Critical Terms for Literary Study, 2nd edn, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1995. Mitchell, W, Picture Theory, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1994. Moon, B, Literary terms: a Practical Glossary, 2nd edn, Chalkface Press, Cottesloe, 2001. Murfin, R & Ray, S.M, The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms, Bedford Books, Boston, 1997. O'Shaughnessy, M & Stadler J, Media and Society: an Introduction, 3rd edn, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2005. (ISBN 978-0-19-551402-5) Prendergast, C, "Circulating Representations: New Historicism and the Poetics of Culture", Substance: The Review of Theory and Literary Criticism, no. 28, issue 1, pp. 90–105, 1999, (online Humanities International Complete) Ryder, M, Semiotics: Language and Culture, 2004, viewed 6 April 2006 [4]. Shook, J, The Pragmatism Cybrary: Charles Morris, in The Pragmatism Cybrary, 2005, viewed 24 April 2006 [5]. Vukcevich, M, Representation, The University of Chicago, 2002, viewed 7 April 2006. |

参考文献 アーナソン, D, 『記号学:記号の体系』(ウェイバックマシン経由) バルディック, C, 「ニュー・ヒストリシズム」, 『オックスフォード文学用語辞典』, 1996年, 2006年4月8日閲覧 [1] バリー, P, 『理論入門:文学・文化理論概論』, マンチェスター大学出版局, イギリス, 2002年. バーチ、R 2005、「チャールズ・サンダース・パース」、『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』所収、2006年4月24日閲覧 [2]。 チャンドラー、D、『初心者のための記号論:様態と表象』、2001年、2006年4月8日閲覧 [3]。 チャイルダーズ J. (編), 『コロンビア現代文学・文化批評辞典』, コロンビア大学出版局, ニューヨーク, 1995年. コンサイス・ラウトレッジ哲学百科事典、ラウトレッジ、ロンドン、1999年。 カラー、J.、『ソシュール』、フォンタナ・モダン・マスターズ、英国、1976年。 デュプリーズ、B、『文学的技法辞典』、トロント大学出版局、カナダ、1991年。 フューリー、P & マンスフィールド、N、『文化研究と批判理論』、オックスフォード大学出版局、オーストラリア、2005年。(ISBN 978-0-19-551294-6) ホール、S (編)、『文化的表象と意味化実践』、オープン大学出版局、ロンドン、1997年。 ホルダー、D、『ソシュール―記号、体系、恣意性』、ケンブリッジ、オーストラリア、1991年。 レントリッキア、F. & マクラフリン、T (編)、『文学研究のための批評用語』、シカゴ大学出版局、ロンドン、1990年。 クララー、M、『文学研究入門』、ラウトリッジ、ロンドン、1998年。 ミッチェル、W、「表現」、F Lentricchia & T McLaughlin (編)、『文学研究のための批判用語』、シカゴ大学出版局、シカゴ、1990年。 ミッチェル、W、「表現」、F Lentricchia & T McLaughlin (編)、『文学研究のための批判用語』第2版、シカゴ大学出版局、シカゴ、1995年。 ミッチェル、W、『画像理論』、シカゴ大学出版局、シカゴ、1994年。 ムーン、B、『文学用語:実用用語集』、第2版、チョークフェイス出版、コッテスロー、2001年。 マーフィン、R、レイ、S.M、『ベッドフォード批評・文学用語集』、ベッドフォードブックス、ボストン、1997年。 オショーネシー、M、スタドラー J、『メディアと社会:入門』第 3 版、オックスフォード大学出版局、サウスメルボルン、2005 年。(ISBN 978-0-19-551402-5) プレンダーガスト、C.「流通する表象:ニュー・ヒストリシズムと文化の詩学」『サブスタンス:理論と文学批評のレビュー』第28巻第1号、90–105頁、1999年(オンライン版 Humanities International Complete) ライダー、M、『記号論:言語と文化』、2004年、2006年4月6日閲覧[4]。 Shook, J, 『プラグマティズム・サイブラリー:チャールズ・モリス』, 『プラグマティズム・サイブラリー』所収, 2005年, 2006年4月24日閲覧 [5]. Vukcevich, M, 『表象』, シカゴ大学, 2002年, 2006年4月7日閲覧. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Representation_(arts) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

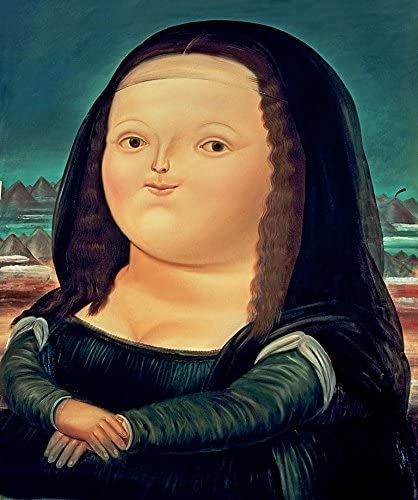

オスカル・ペレンが描くモナリザ(グアテマラの——)

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099