プロパガンダ

Propaganda

James

Montgomery Flagg’s famous “Uncle Sam” propaganda poster, made during

World War I

☆プロパガンダ(Propaganda)

とは、主に聴衆に影響を与え、説得して特定の目的を推進するために用いられるコミュニケーションである。その目的は客観的とは限らず、特定の統合や認識を

促すために事実を選択的に提示したり、感情的な反応を引き出すために偏った言葉遣いを使用したりする場合がある。[1]

プロパガンダは異なる文脈で見られる。[2]

20世紀以降、英語の「プロパガンダ」は操作的な手法と結びつけられるようになったが、歴史的には特定の意見やイデオロギーを推進するあらゆる資料を中立

的に指す用語であった。[1][3]

プロパガンダのメッセージを伝えるために用いられる資料や媒体は多岐にわたり、絵画、漫画、ポスター[4]、パンフレット、映画、ラジオ番組、テレビ番

組、ウェブサイトなど、新技術の発明に伴って変化してきた。近年ではデジタル時代の到来により、新たなプロパガンダ拡散手法が生まれている。例えば計算機

プロパガンダでは、ボットやアルゴリズムを用いて世論を操作する。具体的には、偽ニュースや偏向ニュースを作成してソーシャルメディアで拡散したり、

チャットボットを駆使してソーシャルネットワーク上の議論で実在の人民を模倣したりする手法が挙げられる。

| Propaganda is

communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an

audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be

selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or

perception, or using loaded language to produce an emotional rather

than a rational response to the information that is being presented.[1]

Propaganda can be found in a wide variety of different contexts.[2] Beginning in the twentieth century, the English term propaganda became associated with a manipulative approach, but historically, propaganda had been a neutral descriptive term of any material that promotes certain opinions or ideologies.[1][3] A wide range of materials and media are used for conveying propaganda messages, which changed as new technologies were invented, including paintings, cartoons, posters,[4] pamphlets, films, radio shows, TV shows, and websites. More recently, the digital age has given rise to new ways of disseminating propaganda, for example, in computational propaganda, bots and algorithms are used to manipulate public opinion, e.g., by creating fake or biased news to spread it on social media or using chatbots to mimic real people in discussions in social networks. |

プロパガンダとは、主に聴衆に影響を与え、説得して特定の目的を推進す

るために用いられるコミュニケーションである。その目的は客観的とは限らず、特定の統合や認識を促すために事実を選択的に提示したり、感情的な反応を引き

出すために偏った言葉遣いを使用したりする場合がある。[1] プロパガンダは異なる文脈で見られる。[2] 20世紀以降、英語の「プロパガンダ」は操作的な手法と結びつけられるようになったが、歴史的には特定の意見やイデオロギーを推進するあらゆる資料を中立 的に指す用語であった。[1][3] プロパガンダのメッセージを伝えるために用いられる資料や媒体は多岐にわたり、絵画、漫画、ポスター[4]、パンフレット、映画、ラジオ番組、テレビ番 組、ウェブサイトなど、新技術の発明に伴って変化してきた。近年ではデジタル時代の到来により、新たなプロパガンダ拡散手法が生まれている。例えば計算機 プロパガンダでは、ボットやアルゴリズムを用いて世論を操作する。具体的には、偽ニュースや偏向ニュースを作成してソーシャルメディアで拡散したり、 チャットボットを駆使してソーシャルネットワーク上の議論で実在の人民を模倣したりする手法が挙げられる。 |

| Etymology Main article: Propaganda Fide Propaganda is a modern Latin word, the neuter plural gerundive form of propagare, meaning 'to spread' or 'to propagate', thus propaganda means the things which are to be propagated.[5] Originally this word derived from a new administrative body (congregation) of the Catholic Church created in 1622 as part of the Counter-Reformation, called the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (Congregation for Propagating the Faith), or informally simply Propaganda.[3][6] Its activity was aimed at "propagating" the Catholic faith in non-Catholic countries.[3] From the 1790s, the term began being used also to refer to propaganda in secular activities.[3] In English, the cognate began taking a pejorative or negative connotation in the mid-19th century, when it was used in the political sphere.[3] Non-English cognates of propaganda as well as some similar non-English terms retain neutral or positive connotations. For example, in official party discourse, xuanchuan is treated as a more neutral or positive term, though it can be used pejoratively through protest or other informal settings within China.[7][8]: 4–6 |

語源 詳細な記事: Propaganda Fide プロパガンダは現代ラテン語の単語であり、propagare(広める、普及させる)の中性複数分詞形である。したがってプロパガンダとは、広めるべき事 物を意味する。[5] この語はもともと、1622年に反宗教改革の一環としてカトリック教会に創設された新たな行政機関(聖省)に由来する。その名称は「信仰普及聖省 (Congregatio de Propaganda Fide)」であり、通称は単に「プロパガンダ」であった。[3][6] その活動は、非カトリック諸国におけるカトリック信仰の「普及」を目的としていた。[3] 1790年代から、この用語は世俗的活動におけるプロパガンダを指すようにも用いられ始めた。[3] 英語では、同源語が19世紀半ばに政治分野で使用されるようになり、蔑称的または否定的な意味合いを帯びるようになった。[3] プロパガンダの非英語圏における同源語や類似語は、中立的あるいは肯定的な意味合いを保っている。例えば中国では、党の公式言説において「宣伝」はより中 立的または肯定的な用語として扱われるが、抗議活動やその他の非公式な場面では蔑称として用いられることもある。[7][8]: 4–6 |

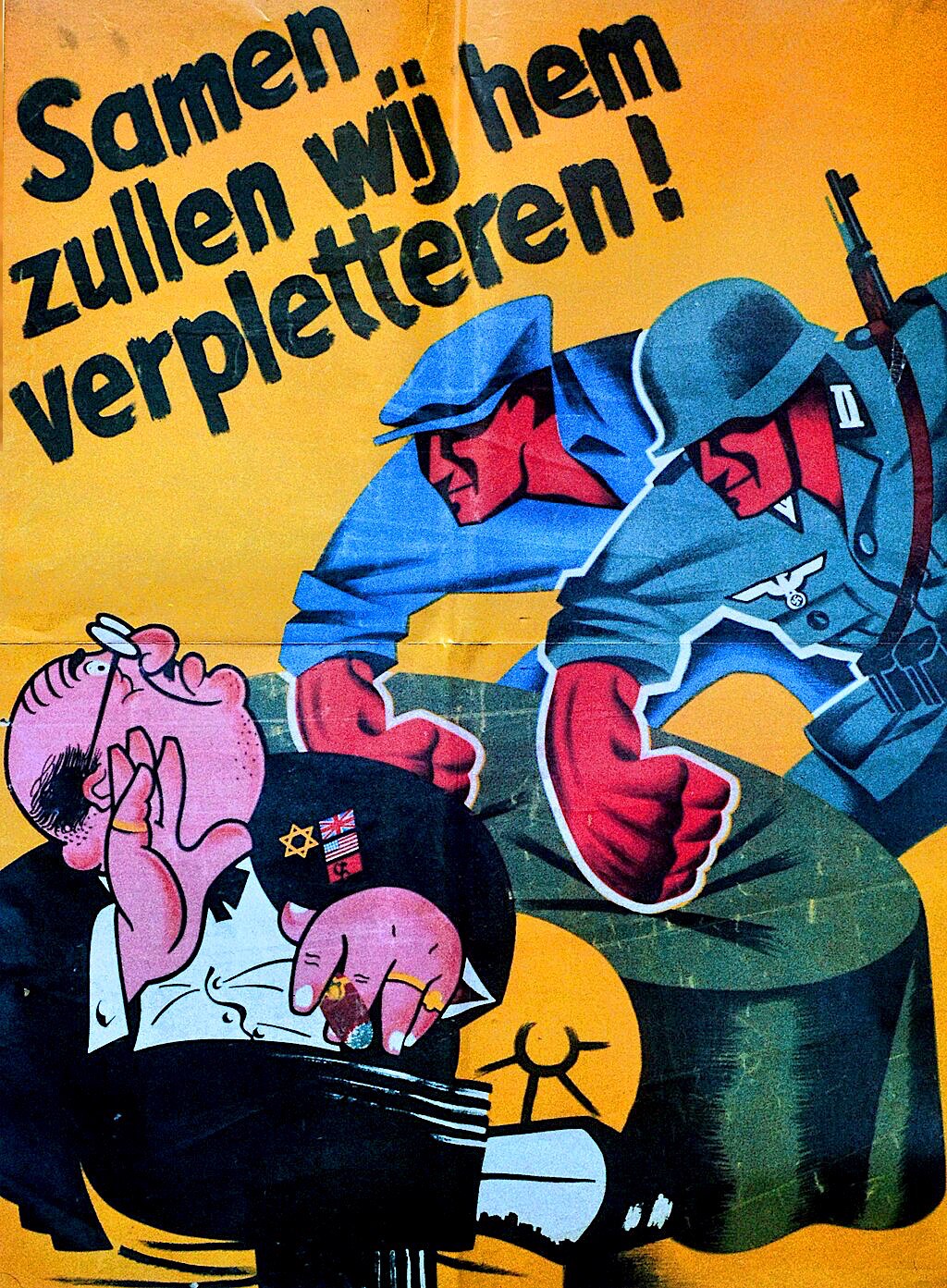

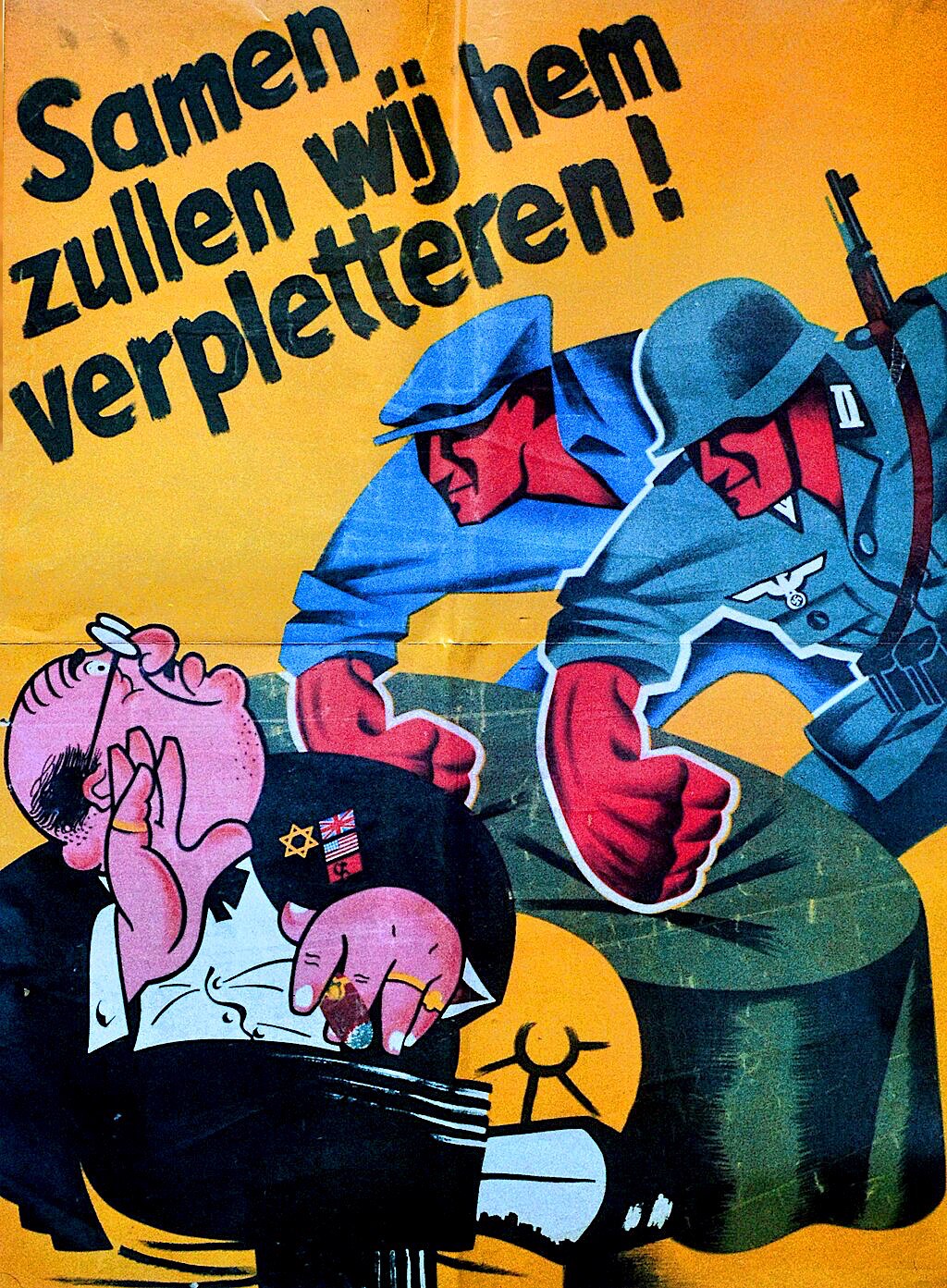

Definitions Nazi Propaganda poster of 27th SS Volunteer Division Langemarck with anti-semitic title: "Together we will crush him!". Historian Arthur Aspinall observed that newspapers were not expected to be independent organs of information when they began to play an important part in political life in the late 1700s, but were assumed to promote the views of their owners or government sponsors.[9] In the 20th century, the term propaganda emerged along with the rise of mass media, including newspapers and radio. As researchers began studying the effects of media, they used suggestion theory to explain how people could be influenced by emotionally-resonant persuasive messages. Harold Lasswell provided a broad definition of the term propaganda, writing it as: "the expression of opinions or actions carried out deliberately by individuals or groups with a view to influencing the opinions or actions of other individuals or groups for predetermined ends and through psychological manipulations."[10] Garth Jowett and Victoria O'Donnell theorize that propaganda and persuasion are linked as humans use communication as a form of soft power through the development and cultivation of propaganda materials.[11] In a 1929 literary debate with Edward Bernays, Everett Dean Martin argues that, "Propaganda is making puppets of us. We are moved by hidden strings which the propagandist manipulates."[12] In the 1920s and 1930s, propaganda was sometimes described as all-powerful. For example, Bernays acknowledged in his book Propaganda that "The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of."[13] NATO's 2011 guidance for military public affairs defines propaganda as "information, ideas, doctrines, or special appeals disseminated to influence the opinion, emotions, attitudes, or behaviour of any specified group in order to benefit the sponsor, either directly or indirectly".[14] More recently the RAND Corporation coined the term Firehose of Falsehood to describe how modern communication capabilities enable a large number of messages to be broadcast rapidly, repetitively, and continuously over multiple channels (like news and social media) without regard for truth or consistency. |

定義 反ユダヤ主義的なタイトル「共に彼を打ち砕く!」を掲げた、第27SS志願師団ランゲマルクのナチス宣伝ポスター。 歴史家アーサー・アスピナルは、1700年代後半に新聞が政治生活で重要な役割を果たし始めた頃、新聞が独立した情報機関であることは期待されておらず、 所有者や政府の後援者の見解を推進することが当然とされていたと指摘している[9]。20世紀には、新聞やラジオを含むマスメディアの台頭とともに「プロ パガンダ」という用語が登場した。研究者がメディアの影響力を研究し始めた際、人民が感情に訴える説得メッセージにどう影響されるかを説明するために暗示 理論が用いられた。ハロルド・ラスウェルはプロパガンダという用語の広範な定義を提示し、次のように記した。「個人や集団が、あらかじめ定めた目的のため に、心理的操作を通じて他の個人や集団の意見や行動に影響を与えることを意図して、意図的に行う意見や行動の表明である」。[10] ガース・ジョウェットとビクトリア・オドネルは、人間がプロパガンダ資料の開発と育成を通じてコミュニケーションをソフトパワーの一形態として利用するた め、プロパガンダと説得は関連していると理論づけている。[11] 1929年にエドワード・バーネイズと行った文学論争の中で、エヴェレット・ディーン・マーティンは「プロパガンダは私たちを操り人形にしている。私たち はプロパガンダ担当者が操作する隠された糸に動かされている」と主張している。[12] 1920年代から1930年代にかけて、プロパガンダは時に全能であると評された。例えば、バーネイズは著書『プロパガンダ』の中で、「大衆の組織化され た習慣や意見を意識的かつ知的に操作することは、民主主義社会において重要な要素である。この目に見えない社会の仕組みを操作する者たちは、我が国の真の 支配力である目に見えない政府を構成している。我々は統治され、精神は形成され、嗜好は作られ、考えは示唆される。その多くは、我々が聞いたこともない者 たちによって行われている」と述べている。[13] NATOの2011年軍事広報指針では、プロパガンダを「スポンサーに直接的または間接的な利益をもたらすため、特定集団の意見・感情・態度・行動に影響 を与える目的で拡散される情報、思想、教義、または特別な訴求」と定義している。[14] さらに近年では、ランド研究所が「虚偽の洪水(Firehose of Falsehood)」という用語を提唱した。これは現代の通信技術が、真実性や一貫性を顧みず、大量のメッセージを複数のチャネル(ニュースやソーシャ ルメディアなど)を通じて迅速に、反復的に、継続的に放送することを可能にする現象を形容するものである。 |

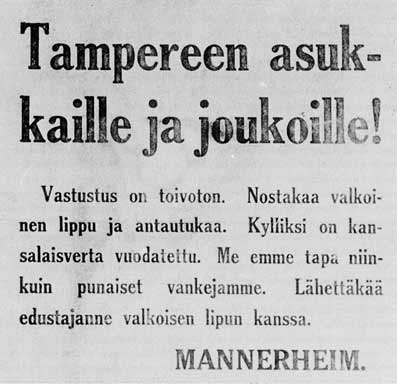

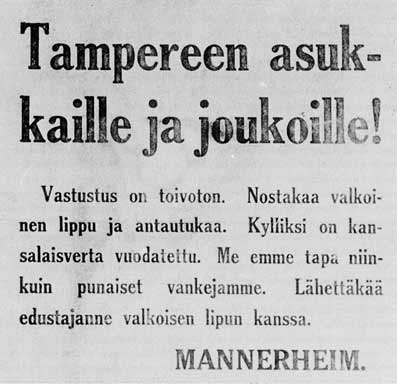

| History Main article: History of propaganda Primitive forms of propaganda have been a human activity as far back as reliable recorded evidence exists. The Behistun Inscription (c. 515 BCE) detailing the rise of Darius I to the Persian throne is viewed by most historians as an early example of propaganda.[15] Another striking example of propaganda during ancient history is the last Roman civil wars (44–30 BCE) during which Octavian and Mark Antony blamed each other for obscure and degrading origins, cruelty, cowardice, oratorical and literary incompetence, debaucheries, luxury, drunkenness and other slanders.[16] This defamation took the form of uituperatio (Roman rhetorical genre of the invective) which was decisive for shaping the Roman public opinion at this time. Another early example of propaganda was from Genghis Khan. The emperor would send some of his men ahead of his army to spread rumors to the enemy. In many cases, his army was actually smaller than his opponents'.[17] Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I was the first ruler to utilize the power of the printing press for propaganda – in order to build his image, stir up patriotic feelings in the population of his empire (he was the first ruler who utilized one-sided battle reports – the early predecessors of modern newspapers or neue zeitungen – targeting the mass.[18][19]) and influence the population of his enemies.[20][21][22] Propaganda during the Reformation, helped by the spread of the printing press throughout Europe, and in particular within Germany, caused new ideas, thoughts, and doctrine to be made available to the public in ways that had never been seen before the 16th century. During the era of the American Revolution, the American colonies had a flourishing network of newspapers and printers who specialized in the topic on behalf of the Patriots (and to a lesser extent on behalf of the Loyalists).[23] Academic Barbara Diggs-Brown conceives that the negative connotations of the term "propaganda" are associated with the earlier social and political transformations that occurred during the French Revolutionary period movement of 1789 to 1799 between the start and the middle portion of the 19th century, in a time when the word started to be used in a nonclerical and political context.[24]  A 1918 Finnish propaganda leaflet signed by General Mannerheim circulated by the Whites urging the Reds to surrender during the Finnish Civil War. [To the residents and troops of Tampere! Resistance is hopeless. Raise the white flag and surrender. The blood of the citizen has been shed enough. We will not kill like the Reds kill our prisoners. Send your representative with a white flag.] The first large-scale and organised propagation of government propaganda was occasioned by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. After the defeat of Germany, military officials such as General Erich Ludendorff suggested that British propaganda had been instrumental in their defeat. Adolf Hitler came to echo this view, believing that it had been a primary cause of the collapse of morale and revolts in the German home front and Navy in 1918 (see also: Dolchstoßlegende). In Mein Kampf (1925) Hitler expounded his theory of propaganda, which provided a powerful base for his rise to power in 1933. Historian Robert Ensor explains that "Hitler...puts no limit on what can be done by propaganda; people will believe anything, provided they are told it often enough and emphatically enough, and that contradicters are either silenced or smothered in calumny."[25] This was to be true in Germany and backed up with their army making it difficult to allow other propaganda to flow in.[26] Most propaganda in Nazi Germany was produced by the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda under Joseph Goebbels. Goebbels mentions propaganda as a way to see through the masses. Symbols are used towards propaganda such as justice, liberty and one's devotion to one's country.[27] World War II saw continued use of propaganda as a weapon of war, building on the experience of WWI, by Goebbels and the British Political Warfare Executive, as well as the United States Office of War Information.[28] In the early 20th century, the invention of motion pictures (as in movies, diafilms) gave propaganda-creators a powerful tool for advancing political and military interests when it came to reaching a broad segment of the population and creating consent or encouraging rejection of the real or imagined enemy. In the years following the October Revolution of 1917, the Soviet government sponsored the Russian film industry with the purpose of making propaganda films (e.g., the 1925 film The Battleship Potemkin glorifies Communist ideals). In WWII, Nazi filmmakers produced highly emotional films to create popular support for occupying the Sudetenland and attacking Poland. The 1930s and 1940s, which saw the rise of totalitarian states and the Second World War, are arguably the "Golden Age of Propaganda". Leni Riefenstahl, a filmmaker working in Nazi Germany, created one of the best-known propaganda movies, Triumph of the Will. In 1942, the propaganda song Niet Molotoff was made in Finland during the Continuation War, making fun of the Red Army's failure in the Winter War, referring the song's name to the Soviet's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov.[29] In the US, animation became popular, especially for winning over youthful audiences and aiding the U.S. war effort, e.g., Der Fuehrer's Face (1942), which ridicules Hitler and advocates the value of freedom. Some American war films in the early 1940s were designed to create a patriotic mindset and convince viewers that sacrifices needed to be made to defeat the Axis Powers.[30] Others were intended to help Americans understand their Allies in general, as in films like Know Your Ally: Britain and Our Greek Allies. Apart from its war films, Hollywood did its part to boost American morale in a film intended to show how stars of stage and screen who remained on the home front were doing their part not just in their labors, but also in their understanding that a variety of peoples worked together against the Axis menace: Stage Door Canteen (1943) features one segment meant to dispel Americans' mistrust of the Soviets, and another to dispel their bigotry against the Chinese. Polish filmmakers in Great Britain created the anti-Nazi color film Calling Mr. Smith[31][32] (1943) about Nazi crimes in German-occupied Europe and about lies of Nazi propaganda.[33] The John Steinbeck novel The Moon Is Down (1942), about the Socrates-inspired spirit of resistance in an occupied village in Northern Europe, was presumed to be about Norway's response to the German occupiers. In 1945, Steinbeck received the King Haakon VII Freedom Cross for his literary contributions to the Norwegian resistance movement.[34] The West and the Soviet Union both used propaganda extensively during the Cold War. Both sides used film, television, and radio programming to influence their own citizens, each other, and Third World nations. Through a front organization called the Bedford Publishing Company, the CIA through a covert department called the Office of Policy Coordination disseminated over one million books to Soviet readers over the span of 15 years, including novels by George Orwell, Albert Camus, Vladimir Nabokov, James Joyce, and Pasternak in an attempt to promote anti-communist sentiment and sympathy of Western values.[35] George Orwell's contemporaneous novels Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four portray the use of propaganda in fictional dystopian societies. During the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro stressed the importance of propaganda.[36][better source needed] Propaganda was used extensively by Communist forces in the Vietnam War as means of controlling people's opinions.[37] During the Yugoslav wars, propaganda was used as a military strategy by governments of Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Croatia. Propaganda was used to create fear and hatred, and particularly to incite the Serb population against the other ethnicities (Bosniaks, Croats, Albanians and other non-Serbs). Serb media made a great effort in justifying, revising or denying mass war crimes committed by Serb forces during these wars.[38] |

歴史 主な記事: 宣伝の歴史 信頼できる記録が残る限り、原始的な形の宣伝は人類の活動として存在してきた。ダレイオス1世のペルシア王位継承を記したベヒストゥン碑文(紀元前515 年頃)は、多くの歴史家によって宣伝の初期の例と見なされている。[15] 古代史におけるプロパガンダのもう一つの顕著な例は、紀元前44年から30年にかけての最後のローマ内戦である。この戦いでオクタヴィアヌスとマルクス・ アントニウスは、互いに卑しい出自、残虐性、臆病さ、弁論や文学の無能さ、放蕩、贅沢、酩酊その他の誹謗中傷を非難し合った。[16] この誹謗中傷は「ウイトゥペラティオ」(ローマの修辞学における罵倒のジャンル)という形式を取り、当時のローマ世論形成に決定的な役割を果たした。プロ パガンダのもう一つの初期例はチンギス・カンによるものだ。皇帝は軍隊より先に部下を送り込み、敵に噂を流布させた。多くの場合、彼の軍勢は実際には敵軍 より少なかった。[17] 神聖ローマ皇帝マクシミリアン1世は、印刷技術の力をプロパガンダに利用した最初の統治者である。自らのイメージ構築、帝国住民への愛国心喚起(彼は大衆 を標的とした一方的な戦況報告―現代新聞やノイエ・ツァイトゥングの初期形態―を利用した最初の統治者である[18][19])、そして敵対勢力住民への 影響力行使を目的とした。[20][21][22] 宗教改革期のプロパガンダは、印刷技術がヨーロッパ全域、特にドイツ国内に普及したことで後押しされ、16世紀以前には見られなかった方法で新たな思想や 教義を大衆に広めることとなった。アメリカ独立戦争の時代には、アメリカ植民地において、愛国者側(そしてより小規模ながら王党派側)のために専門的に活 動する新聞と印刷業者のネットワークが繁栄していた。[23] 学者のバーバラ・ディグス=ブラウンは、「プロパガンダ」という言葉の否定的な意味合いは、1789年から1799年にかけてのフランス革命期から19世 紀前半にかけての社会・政治的変革と結びついていると考える。この時期に、この言葉は非宗教的・政治的文脈で使われ始めたのだ。[24]  1918年フィンランド内戦時、白軍が赤軍への降伏を促すために配布したマンネルヘイム将軍署名入りプロパガンダビラ。[タンペレの住民と兵士たちへ!抵 抗は無駄だ。白旗を掲げて降伏せよ。市民の血は十分流された。我々は赤軍のように捕虜を殺さない。白旗を持って代表者を送れ。] 政府による大規模かつ組織的なプロパガンダ普及の始まりは、1914年の第一次世界大戦勃発に端を発する。ドイツ敗戦後、エーリヒ・ルーデンドルフ将軍ら 軍関係者は、英国のプロパガンダが敗因の一つであったと主張した。アドルフ・ヒトラーはこの見解に同調し、1918年のドイツ国内戦線と海軍における士気 の崩壊と反乱の主因はプロパガンダにあったと信じた(参照:ドルフストース伝説)。『我が闘争』(1925年)においてヒトラーは自らのプロパガンダ理論 を展開し、これが1933年の権力掌握の強力な基盤となった。歴史家ロバート・エンソールは「ヒトラーは…プロパガンダで成し得ることに制限を設けない。 人民は、十分に頻繁に、十分に力強く伝えられ、かつ反対意見が沈黙させられるか中傷で押し潰される限り、何でも信じる」と説明している。[25] これはドイツにおいて真実となり、軍隊の支援によって他国のプロパガンダ流入が困難にされた。[26] ナチス・ドイツにおけるプロパガンダのほとんどは、ヨーゼフ・ゲッベルス率いる国民啓蒙・宣伝省によって制作された。ゲッベルスはプロパガンダを大衆を見 通す手段として言及している。正義、自由、祖国への献身といった象徴がプロパガンダに利用される。[27] 第二次世界大戦では、第一次大戦の経験を踏まえ、ゲッベルスや英国の政治戦執行部、米国戦争情報局によって、プロパガンダが戦争の武器として継続的に使用 された。[28] 20世紀初頭、活動写真(映画やスライドフィルムなど)の発明は、プロパガンダ制作者に強力な手段を与えた。広範な層に到達し、政治的・軍事的利益を推進 し、合意を形成したり、実在する敵や想像上の敵への拒絶を促す上で有用だったのだ。1917年の十月革命後、ソビエト政府はプロパガンダ映画制作を目的と してロシア映画産業を支援した(例:1925年製作『戦艦ポチョムキン』は共産主義の理想を称賛する)。第二次世界大戦中、ナチスの映画製作者たちは、ズ デーテン地方の占領やポーランド侵攻への国民的支持を得るため、感情に訴える映画を制作した。全体主義国家の台頭と第二次世界大戦を経験した1930年代 から1940年代は、おそらく「プロパガンダの黄金時代」と言える。ナチス・ドイツで活躍した映画監督レーニ・リーフェンシュタールは、最も有名なプロパ ガンダ映画の一つ『意志の勝利』を制作した。1942年には、継続戦争下のフィンランドでプロパガンダ歌謡『ニート・モロトフ』が制作された。これは冬戦 争における赤軍の敗北を嘲笑するもので、曲名はソ連外相ヴィャチェスラフ・モロトフに由来する。[29] 米国ではアニメーションが人気を博し、特に若年層の観客を獲得し、米国の戦争遂行を支援するために活用された。例えば『総統の顔』(1942年)はヒト ラーを嘲笑し、自由の価値を主張する作品である。1940年代初頭の米国製戦争映画の一部は、愛国的な意識を醸成し、枢軸国を打ち負かすためには犠牲が必 要だと観客を説得することを目的としていた。[30] 他には、アメリカ人が同盟国全般を理解する助けとなることを意図した作品もあった。例えば『知れ、我らの同盟国:英国とギリシャ』のような映画である。戦 争映画とは別に、ハリウッドは国民の士気を高める役割も果たした。舞台やスクリーンのスターたちが、労働面だけでなく、様々な人々が協力して枢軸国の脅威 に立ち向かっていることを理解している姿を示す映画である: 『ステージドア・カンティーン』(1943年)には、アメリカ人のソ連に対する不信感を払拭するための部分と、中国人に対する偏見を払拭するための部分が ある。イギリス在住のポーランド人映画製作者たちは、ナチス占領下のヨーロッパにおけるナチスの犯罪とナチス宣伝の嘘について描いた反ナチスカラー映画 『スミス氏を呼べ』(1943年)を制作した。[33] ジョン・スタインベックの小説『月が沈む』(1942年)は、ソクラテスにインスピレーションを得た、北ヨーロッパの占領下の村での抵抗精神について書か れたもので、ドイツ占領軍に対するノルウェーの反応について書かれたものと推定された。1945年、スタインベックは、ノルウェーの抵抗運動への文学的貢 献により、ホーコン7世国王自由十字章を授与された。[34] 冷戦時代、西側諸国とソ連はともにプロパガンダを多用した。双方は、自国民、相手国、そして第三世界各国の国民に影響を与えるために、映画、テレビ、ラジ オ番組を利用した。CIA は、ベッドフォード出版会社という表向きの組織を通じて、政策調整局という秘密部門により、15 年間にわたり 100 万冊以上の書籍をソ連の読者に配布した。その中には、ジョージ・オーウェル、アルベール・カミュ、ウラジーミル・ナボコフ、ジェームズ・ジョイス、パステ ルナークの小説も含まれており、反共産主義の感情と西洋的価値観への共感を促進しようとしたものである。[35] ジョージ・オーウェルの同時代小説『動物農場』と『1984』は、架空のディストピア社会におけるプロパガンダの活用を描いている。キューバ革命の際、 フィデル・カストロはプロパガンダの重要性を強調した。[36][より良い出典が必要] ベトナム戦争では、共産主義勢力が人々の意見を統制する手段としてプロパガンダを多用した。[37] ユーゴスラビア紛争では、ユーゴスラビア連邦共和国とクロアチア政府がプロパガンダを軍事戦略として用いた。恐怖と憎悪を煽り、特にセルビア人住民を他の 民族(ボスニア人、クロアチア人、アルバニア人、その他の非セルビア人)に対して扇動するためにプロパガンダが利用された。セルビアのメディアは、これら の戦争中にセルビア軍が犯した大量戦争犯罪を正当化、改変、あるいは否定するために多大な努力を払った。[38] |

| Public perceptions In the early 20th century the term propaganda was used by the founders of the nascent public relations industry to refer to their people. Literally translated from the Latin gerundive as "things that must be disseminated", in some cultures the term is neutral or even positive, while in others the term has acquired a strong negative connotation. The connotations of the term "propaganda" can also vary over time. For example, in Portuguese and some Spanish language speaking countries, particularly in the Southern Cone, the word "propaganda" usually refers to the most common manipulative media in business terms – "advertising".[39]  Poster of the 19th-century Scandinavist movement In English, propaganda was originally a neutral term for the dissemination of information in favor of any given cause. During the 20th century, however, the term acquired a thoroughly negative meaning in western countries, representing the intentional dissemination of often false, but certainly "compelling" claims to support or justify political actions or ideologies. According to Harold Lasswell, the term began to fall out of favor due to growing public suspicion of propaganda in the wake of its use during World War I by the Creel Committee in the United States and the Ministry of Information in Britain: Writing in 1928, Lasswell observed, "In democratic countries the official propaganda bureau was looked upon with genuine alarm, for fear that it might be suborned to party and personal ends. The outcry in the United States against Mr. Creel's famous Bureau of Public Information (or 'Inflammation') helped to din into the public mind the fact that propaganda existed. ... The public's discovery of propaganda has led to a great of lamentation over it. Propaganda has become an epithet of contempt and hate, and the propagandists have sought protective coloration in such names as 'public relations council,' 'specialist in public education,' 'public relations adviser.' "[40] In 1949, political science professor Dayton David McKean wrote, "After World War I the word came to be applied to 'what you don't like of the other fellow's publicity,' as Edward L. Bernays said...."[41] Contestation The term is essentially contested and some have argued for a neutral definition,[42][43]: 9 arguing that ethics depend on intent and context,[43] while others define it as necessarily unethical and negative.[44] Emma Briant defines it as "the deliberate manipulation of representations (including text, pictures, video, speech etc.) with the intention of producing any effect in the audience (e.g. action or inaction; reinforcement or transformation of feelings, ideas, attitudes or behaviours) that is desired by the propagandist."[43]: 9 The same author explains the importance of consistent terminology across history, particularly as contemporary euphemistic synonyms are used in governments' continual efforts to rebrand their operations such as 'information support' and strategic communication.[43]: 9 Other scholars also see benefits to acknowledging that propaganda can be interpreted as beneficial or harmful, depending on the message sender, target audience, message, and context.[2] David Goodman argues that the 1936 League of Nations "Convention on the Use of Broadcasting in the Cause of Peace" tried to create the standards for a liberal international public sphere. The Convention encouraged empathetic and neighborly radio broadcasts to other nations. It called for League prohibitions on international broadcast containing hostile speech and false claims. It tried to define the line between liberal and illiberal policies in communications, and emphasized the dangers of nationalist chauvinism. With Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia active on the radio, its liberal goals were ignored, while free speech advocates warned that the code represented restraints on free speech.[45] |

世論 20世紀初頭、新興の広報産業の創始者たちは、自らの人民を指す言葉として「プロパガンダ」という用語を用いた。ラテン語の動名詞形を直訳すると「広めな ければならないもの」という意味になるが、この用語は文化によって中立的あるいは肯定的に捉えられる場合もあれば、強い否定的な意味合いを持つ場合もあ る。また「プロパガンダ」という言葉の含意は時代によって変化することもある。例えば、ポルトガル語圏やスペイン語圏の一部、特に南米南部では、「プロパ ガンダ」という言葉は通常、ビジネス用語で最も一般的な操作的なメディアである「広告」を指す。[39]  19世紀スカンジナビア主義運動のポスター 英語において、プロパガンダは元々、特定の目的を支持する情報拡散を指す中立的な用語であった。しかし20世紀に入り、この用語は西洋諸国で完全に否定的 な意味を獲得した。それは政治的行動やイデオロギーを支持・正当化するため、しばしば虚偽でありながらも確実に「説得力のある」主張を意図的に拡散するこ とを表すようになった。ハロルド・ラスウェルによれば、この用語が廃れ始めたのは、第一次世界大戦中にアメリカ合衆国のクリール委員会と英国の情報省がプ ロパガンダを利用したことで、公衆の疑念が高まったためである。1928年にラスウェルはこう記している。「民主主義国家では、公式のプロパガンダ局は党 派や人格の目的のために買収される恐れがあるとして、真に警戒の眼差しを向けられていた。」 米国におけるクリール氏の有名な広報局(あるいは『扇動局』)への抗議は、プロパガンダの存在を大衆の意識に深く刻み込む一助となった。…大衆によるプロ パガンダの発見は、それに対する大きな嘆きへとつながった。プロパガンダは軽蔑と憎悪の代名詞となり、プロパガンダ担当者は『広報評議会』『公共教育専門 家』『広報顧問』といった名称で保護色を求め始めた。[40] 1949 年、政治学教授デイトン・デイヴィッド・マッキーンはこう記した。「第一次世界大戦後、この言葉はエドワード・L・バーネイズが言うところの『相手の宣伝 で気に入らないもの』を指すようになった」...[41] 論争 この用語は本質的に論争の的となっており、中立的な定義を主張する者もいる[42][43]: 9 。倫理は意図と文脈に依存すると主張する[43]一方 で、必然的に非倫理的で否定的なものと定義する者もいる。[44] エマ・ブライアントはこれを「プロパガンダ実践者が望む効果(行動または不作為、感情・思想・態度・行動の強化または変容など)を聴衆に生じさせる意図 で、表現(テキスト・画像・動画・音声等を含む)を意図的に操作すること」と定義する。[43]: 9 同じ著者は、歴史を通じて用語の一貫性を保つことの重要性を説明している。特に、政府が「情報支援」や戦略的コミュニケーションなど、その活動を再ブラン ド化するために、現代的な婉曲的な同義語を絶えず使用していることから、その重要性は高い。[43]: 9 他の学者たちも、プロパガンダは、メッセージの送信者、対象読者、メッセージ、文脈に応じて、有益とも有害とも解釈できることを認識することの利点を認識 している。[2] デビッド・グッドマンは、1936年の国際連盟「平和のための放送利用に関する条約」が、リベラルな国際公共圏の基準を作ろうとしたと論じている。この条 約は、他国民に対する共感と友好的なラジオ放送を奨励した。また、敵対的な発言や虚偽の主張を含む国際放送を国際連盟が禁止するよう求めた。通信における リベラルな政策と非リベラルな政策の境界線を定義しようとし、ナショナリストの危険性を強調した。ナチスドイツとソビエトロシアがラジオで活発に活動して いたため、そのリベラルな目標は無視され、一方、言論の自由の擁護者たちは、この規範が言論の自由の制限となることを警告した。 |

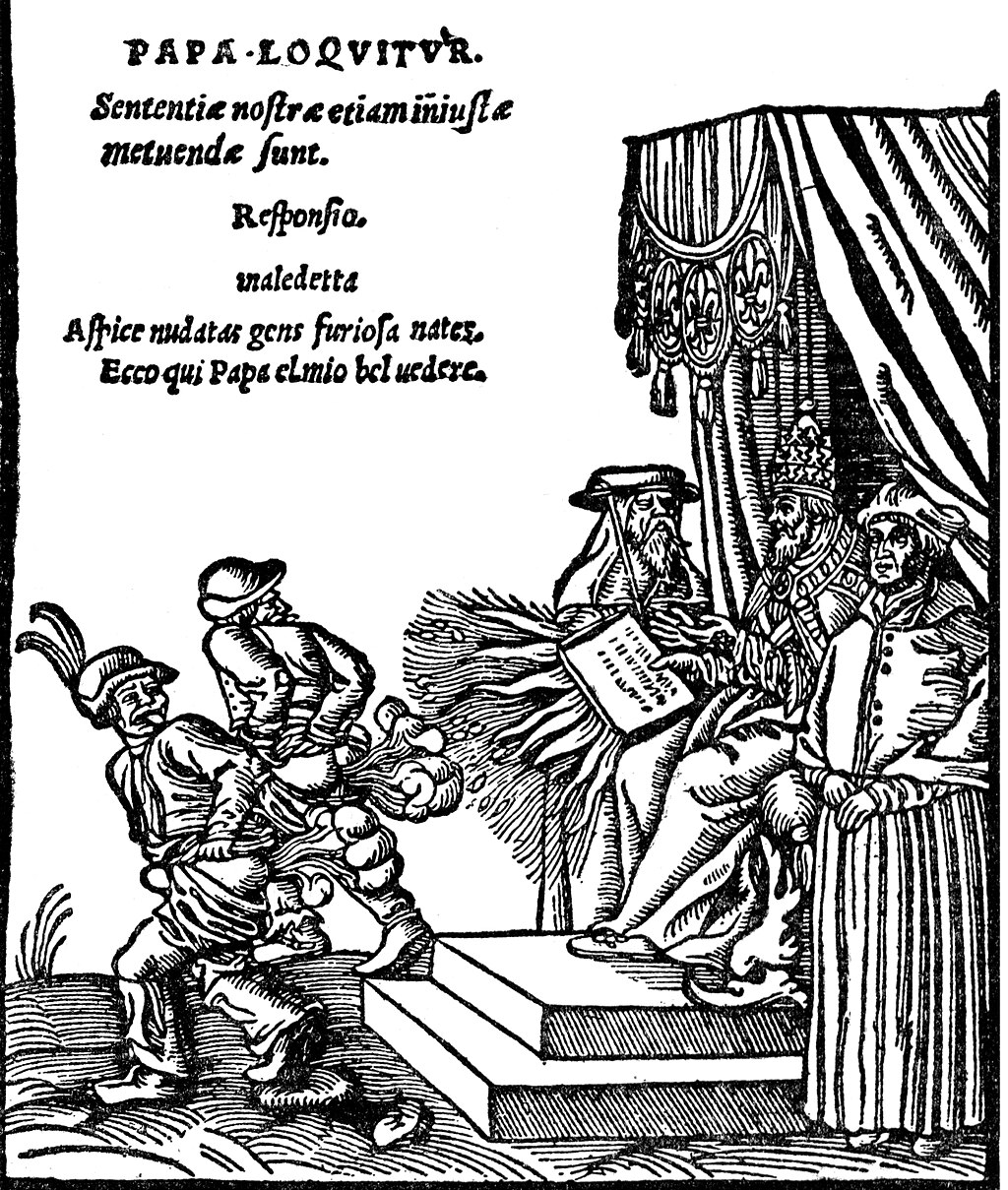

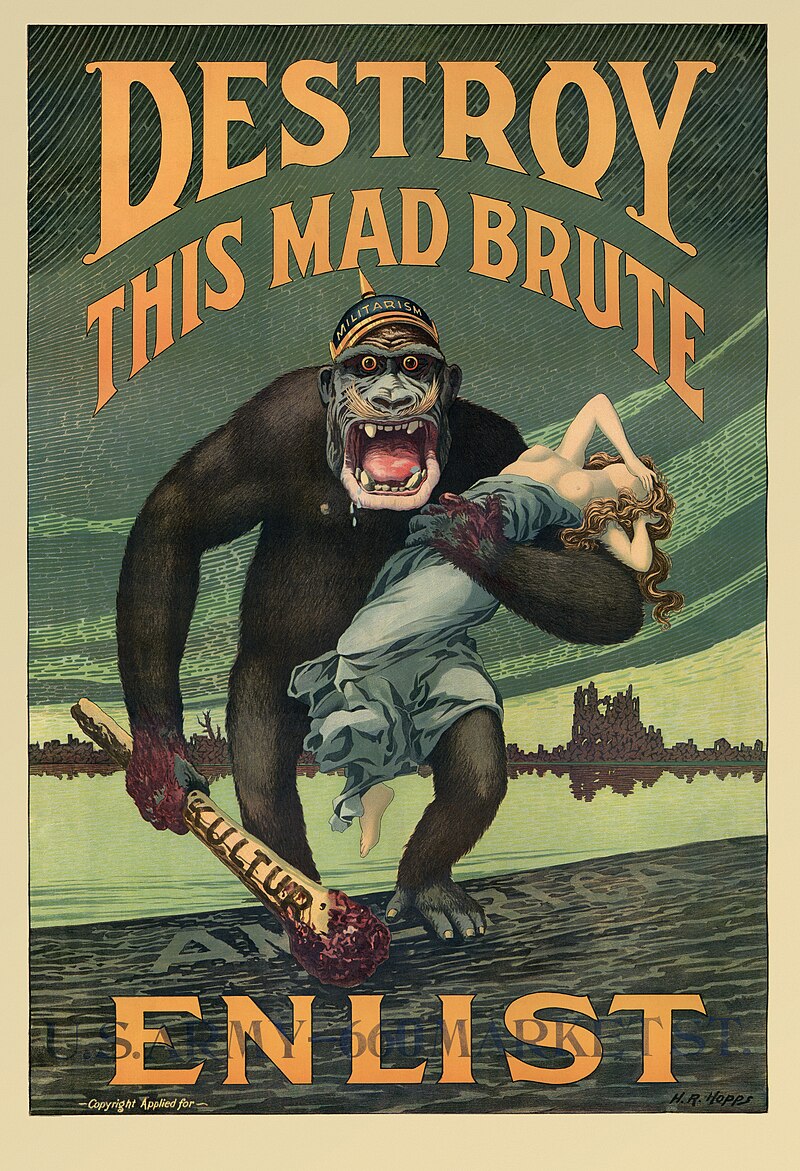

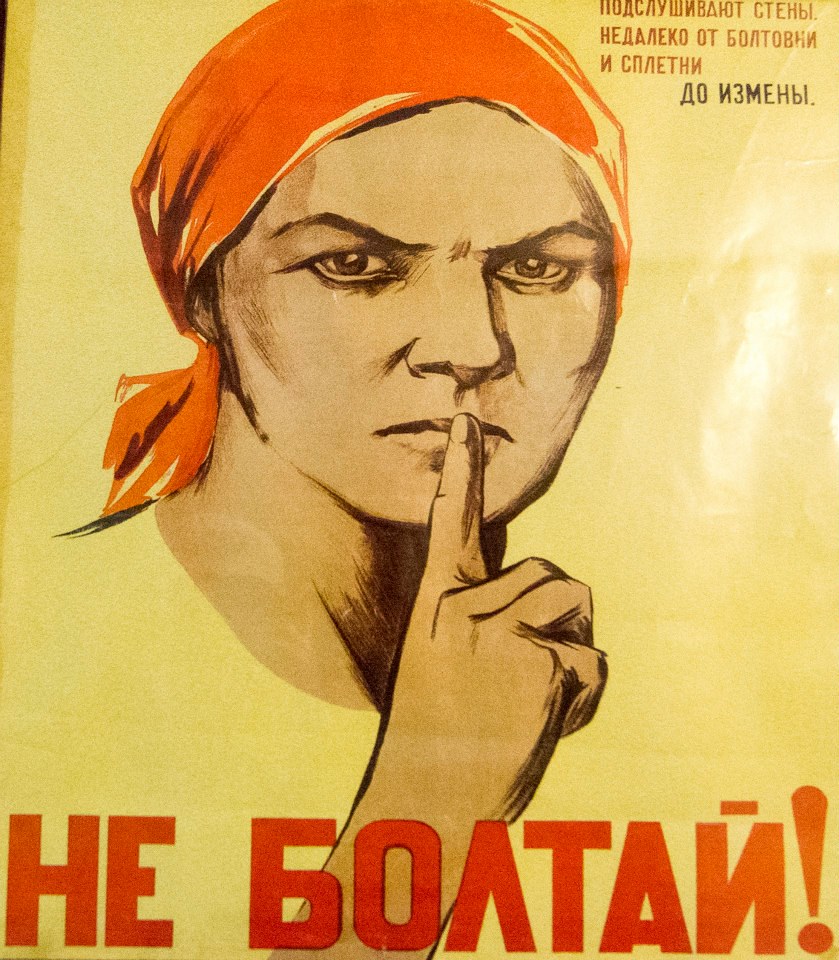

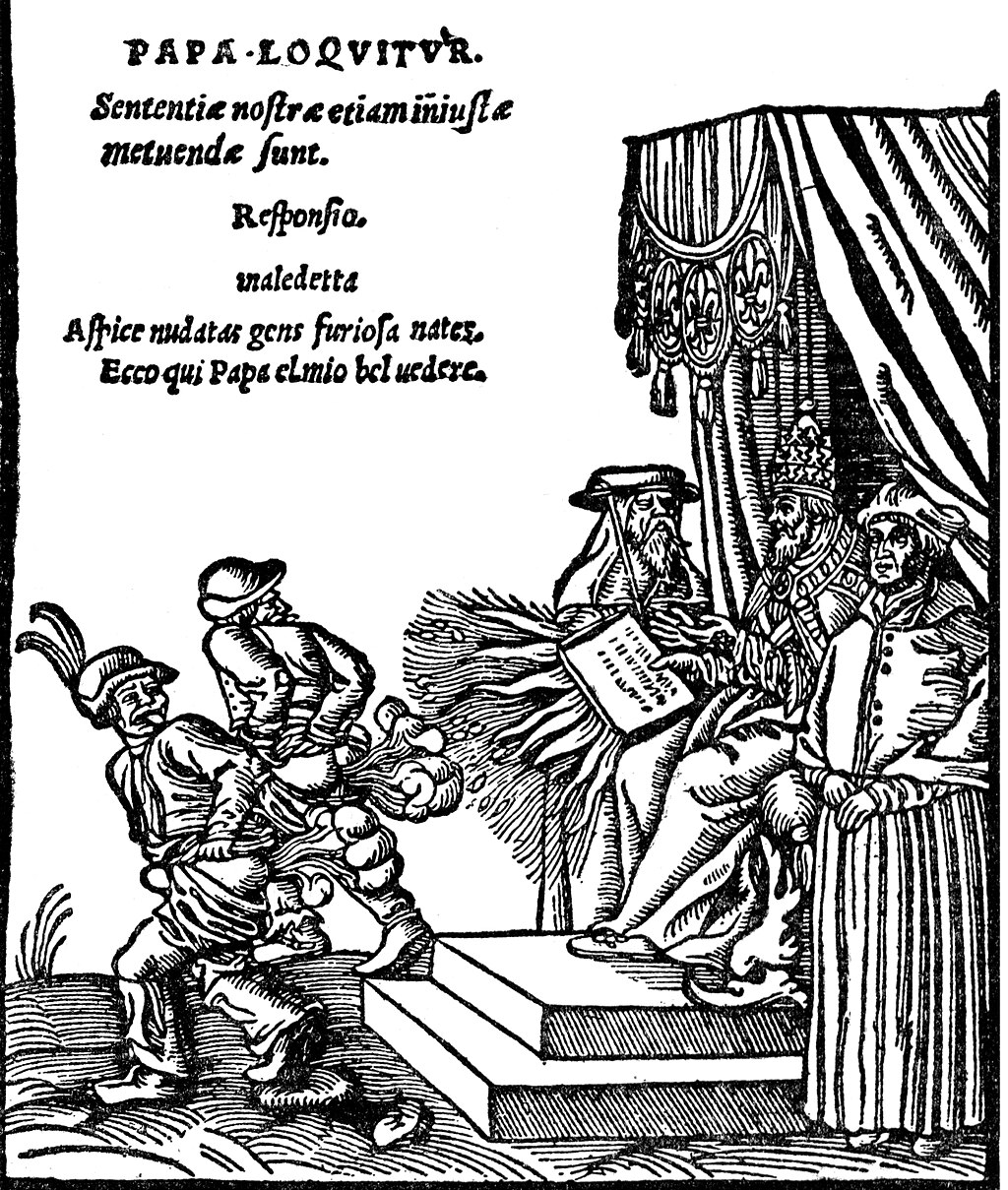

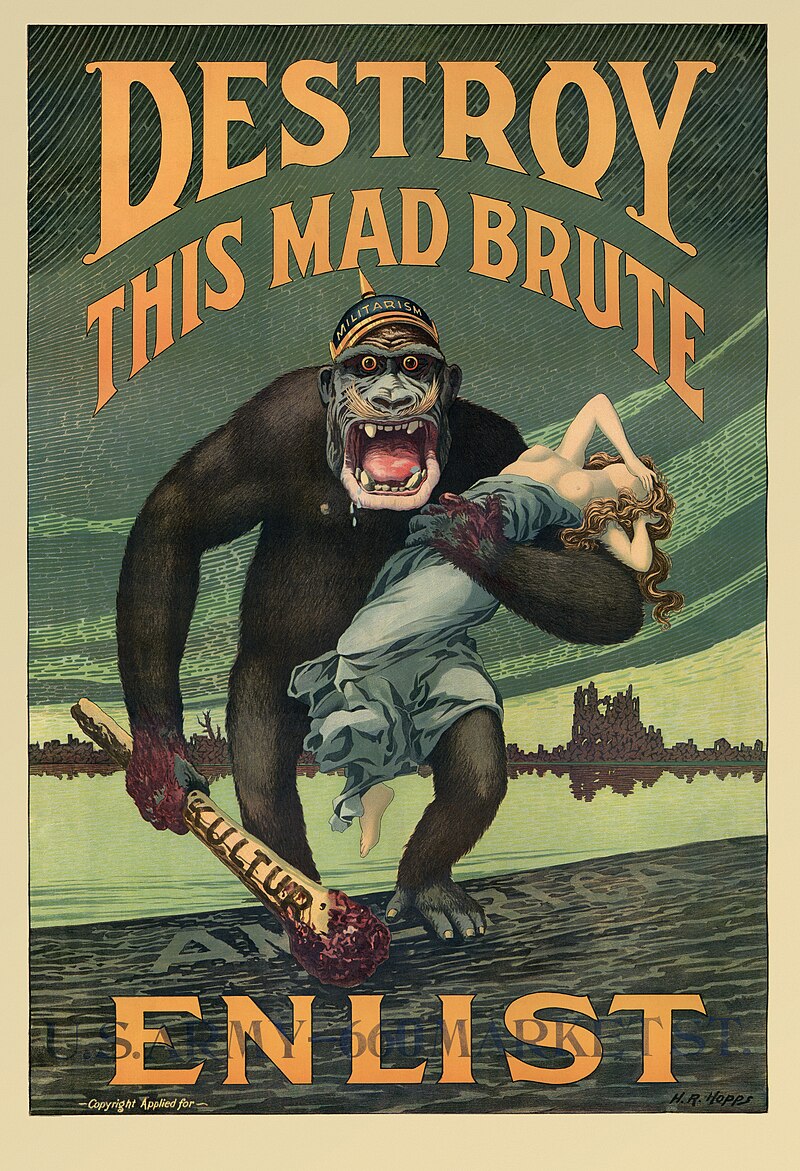

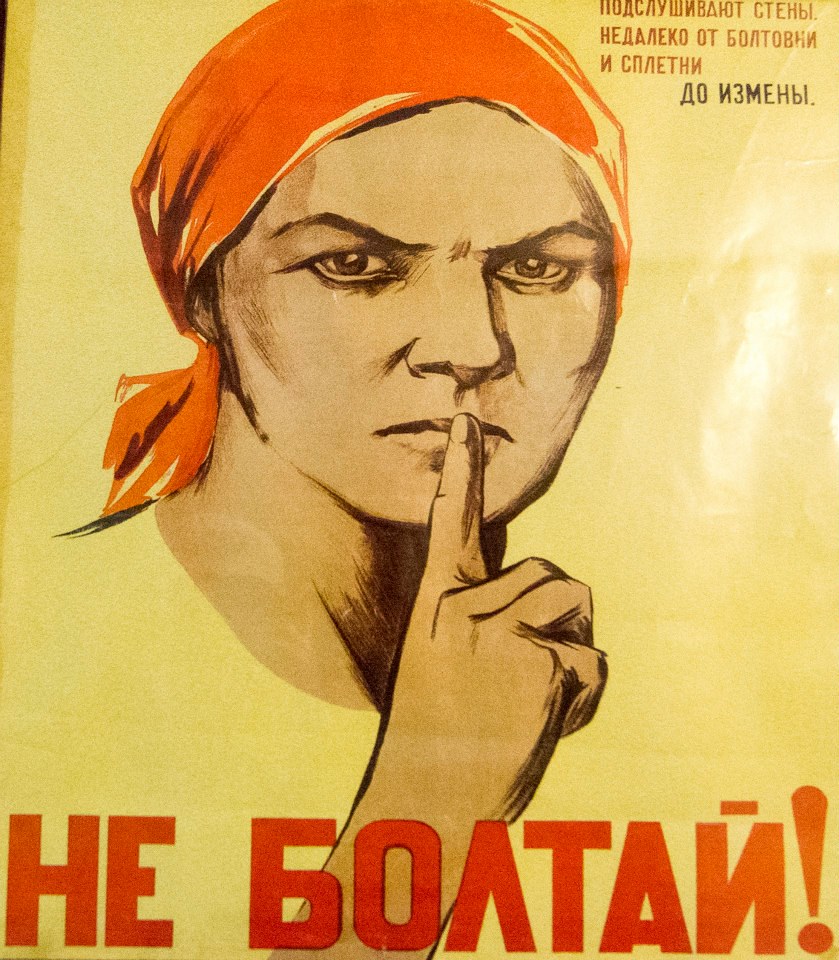

Types Poster in a North Korean primary school targeting the United States military. The Korean text reads: "Are you playing the game of catching these guys?" Identifying propaganda has always been a problem.[46] The main difficulties have involved differentiating propaganda from other types of persuasion, and avoiding a biased approach. Richard Alan Nelson provides a definition of the term: "Propaganda is neutrally defined as a systematic form of purposeful persuasion that attempts to influence the emotions, attitudes, opinions, and actions of specified target audiences for ideological, political or commercial purposes[47] through the controlled transmission of one-sided messages (which may or may not be factual) via mass and direct media channels."[48] The definition focuses on the communicative process involved – or more precisely, on the purpose of the process, and allow "propaganda" to be interpreted as positive or negative behavior depending on the perspective of the viewer or listener. Propaganda can often be recognized by the rhetorical strategies used in its design. In the 1930s, the Institute for Propaganda Analysis identified a variety of propaganda techniques that were commonly used in newspapers and on the radio, which were the mass media of the time period. Propaganda techniques include "name calling" (using derogatory labels), "bandwagon" (expressing the social appeal of a message), or "glittering generalities" (using positive but imprecise language).[49] With the rise of the internet and social media, Renee Hobbs identified four characteristic design features of many forms of contemporary propaganda: (1) it activates strong emotions; (2) it simplifies information; (3) it appeals to the hopes, fears, and dreams of a targeted audience; and (4) it attacks opponents.[50] Propaganda is sometimes evaluated based on the intention and goals of the individual or institution who created it. According to historian Zbyněk Zeman, propaganda is defined as either white, grey or black. White propaganda openly discloses its source and intent. Grey propaganda has an ambiguous or non-disclosed source or intent. Black propaganda purports to be published by the enemy or some organization besides its actual origins[51] (compare with black operation, a type of clandestine operation in which the identity of the sponsoring government is hidden). In scale, these different types of propaganda can also be defined by the potential of true and correct information to compete with the propaganda. For example, opposition to white propaganda is often readily found and may slightly discredit the propaganda source. Opposition to grey propaganda, when revealed (often by an inside source), may create some level of public outcry. Opposition to black propaganda is often unavailable and may be dangerous to reveal, because public cognizance of black propaganda tactics and sources would undermine or backfire the very campaign the black propagandist supported. The propagandist seeks to change the way people understand an issue or situation for the purpose of changing their actions and expectations in ways that are desirable to the interest group. Propaganda, in this sense, serves as a corollary to censorship in which the same purpose is achieved, not by filling people's minds with approved information, but by preventing people from being confronted with opposing points of view. What sets propaganda apart from other forms of advocacy is the willingness of the propagandist to change people's understanding through deception and confusion rather than persuasion and understanding. The leaders of an organization know the information to be one sided or untrue, but this may not be true for the rank and file members who help to disseminate the propaganda.  Woodcuts (1545) known as the Papstspotbilder or Depictions of the Papacy in English,[52] by Lucas Cranach, commissioned by Martin Luther.[53] Title: Kissing the Pope's Feet.[54] German peasants respond to a papal bull of Pope Paul III. Caption reads: "Don't frighten us Pope, with your ban, and don't be such a furious man. Otherwise we shall turn around and show you our rears."[55][56] Religious Propaganda was often used to influence opinions and beliefs on religious issues, particularly during the split between the Roman Catholic Church and the Protestant churches or during the Crusades.[57] The sociologist Jeffrey K. Hadden has argued that members of the anti-cult movement and Christian counter-cult movement accuse the leaders of what they consider cults of using propaganda extensively to recruit followers and keep them. Hadden argued that ex-members of cults and the anti-cult movement are committed to making these movements look bad.[58] Propaganda against other religions in the same community or propaganda intended to keep political power in the hands of a religious elite can incite religious hate on a global or national scale. It could make use of many propaganda mediums. War, terrorism, riots, and other violent acts can result from it. It can also conceal injustices, inequities, exploitation, and atrocities, leading to ignorance-based indifference and alienation.[59] Wartime This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  A famous example of propaganda, this poster made by Paul Revere portrays the Boston Massacre in a way that he hoped would make Americans angry and support the Revolutionary War. In the Peloponnesian War, the Athenians exploited the figures from stories about Troy as well as other mythical images to incite feelings against Sparta. For example, Helen of Troy was even portrayed as an Athenian, whose mother Nemesis would avenge Troy.[60][61] During the Punic Wars, extensive campaigns of propaganda were carried out by both sides. To dissolve the Roman system of socii and the Greek poleis, Hannibal released without conditions Latin prisoners that he had treated generously to their native cities, where they helped to disseminate his propaganda.[62] The Romans on the other hand tried to portray Hannibal as a person devoid of humanity and would soon lose the favour of gods. At the same time, led by Q.Fabius Maximus, they organized elaborate religious rituals to protect Roman morale.[63][62] In the early sixteenth century, Maximilian I invented one kind of psychological warfare targeting the enemies. During his war against Venice, he attached pamphlets to balloons that his archers would shoot down. The content spoke of freedom and equality and provoked the populace to rebel against the tyrants (their Signoria).[22]  Propaganda poster shows a terrifying gorilla with a helmet labeled "militarism" holding a bloody club labeled "kultur" and a half-naked woman as he stomps onto the shore of America. Destroy this Mad Brute: Enlist— propaganda poster encouraging men in the United States to enlist and fight Germany as part of WWI, by Harry R. Hopps, c. 1917  Soviet "Ne Boltai" poster. Translates to "Don't Chatter". Similar to American "Loose Lips Sink Ships" posters, this iconic piece of propaganda tries to warn citizens against giving out secrets. Propaganda is a powerful weapon in war; in certain cases, it is used to dehumanize and create hatred toward a supposed enemy, either internal or external, by creating a false image in the mind of soldiers and citizens. This can be done by using derogatory or racist terms (e.g., the racist terms "Jap" and "gook" used during World War II and the Vietnam War, respectively), avoiding some words or language or by making allegations of enemy atrocities. The goal of this was to demoralize the opponent into thinking what was being projected was actually true.[64] Most propaganda efforts in wartime require the home population to feel the enemy has inflicted an injustice, which may be fictitious or may be based on facts (e.g., the sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania by the German Navy in World War I). The home population must also believe that the cause of their nation in the war is just. In these efforts it was difficult to determine the accuracy of how propaganda truly impacted the war.[65] In NATO doctrine, propaganda is defined as "Information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote a political cause or point of view."[66] Within this perspective, the information provided does not need to be necessarily false but must be instead relevant to specific goals of the "actor" or "system" that performs it. Propaganda is also one of the methods used in psychological warfare, which may also involve false flag operations in which the identity of the operatives is depicted as those of an enemy nation (e.g., The Bay of Pigs Invasion used CIA planes painted in Cuban Air Force markings). The term propaganda may also refer to false information meant to reinforce the mindsets of people who already believe as the propagandist wishes (e.g., During the First World War, the main purpose of British propaganda was to encourage men to join the army, and women to work in the country's industry. Propaganda posters were used because regular general radio broadcasting was yet to commence and TV technology was still under development).[67] The assumption is that, if people believe something false, they will constantly be assailed by doubts. Since these doubts are unpleasant (see cognitive dissonance), people will be eager to have them extinguished, and are therefore receptive to the reassurances of those in power. For this reason, propaganda is often addressed to people who are already sympathetic to the agenda or views being presented. This process of reinforcement uses an individual's predisposition to self-select "agreeable" information sources as a mechanism for maintaining control over populations.[improper synthesis?]   Serbian propaganda from the Bosnian War (1992–95) presented as an actual photograph from the scene of, as stated in report below the image, a "Serbian boy whose whole family was killed by Bosnian Muslims". The image is derived from an 1879 "Orphan on mother's grave" painting by Uroš Predić (alongside).[68] Propaganda may be administered in insidious ways. For instance, disparaging disinformation about the history of certain groups or foreign countries may be encouraged or tolerated in the educational system. Since few people actually double-check what they learn at school, such disinformation will be repeated by journalists as well as parents, thus reinforcing the idea that the disinformation item is really a "well-known fact", even though no one repeating the myth is able to point to an authoritative source. The disinformation is then recycled in the media and in the educational system, without the need for direct governmental intervention on the media. Such permeating propaganda may be used for political goals: by giving citizens a false impression of the quality or policies of their country, they may be incited to reject certain proposals or certain remarks or ignore the experience of others.  Britannia arm-in-arm with Uncle Sam symbolizes the British-American alliance in World War I.  Poster depicting Winston Churchill as a "British Bulldog" In the Soviet Union during the Second World War, the propaganda designed to encourage civilians was controlled by Stalin, who insisted on a heavy-handed style that educated audiences easily saw was inauthentic. On the other hand, the unofficial rumors about German atrocities were well founded and convincing.[69] Stalin was a Georgian who spoke Russian with a heavy accent. That would not do for a national hero so starting in the 1930s all new visual portraits of Stalin were retouched to erase his Georgian facial characteristics[clarify][70] and make him a more generalized Soviet hero. Only his eyes and famous moustache remained unaltered. Zhores Medvedev and Roy Medvedev say his "majestic new image was devised appropriately to depict the leader of all times and of all peoples."[71] Article 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights prohibits any propaganda for war as well as any advocacy of national or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence by law.[72] Naturally, the common people don't want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship. The people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country. — Hermann Göring[73] Simply enough the covenant specifically is not defining the content of propaganda. In simplest terms, an act of propaganda if used in a reply to a wartime act is not prohibited.[74] Advertising Propaganda shares techniques with advertising and public relations, each of which can be thought of as propaganda that promotes a commercial product or shapes the perception of an organization, person, or brand. For example, after claiming victory in the 2006 Lebanon War, Hezbollah campaigned for broader popularity among Arabs by organizing mass rallies where Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah combined elements of the local dialect with classical Arabic to reach audiences outside Lebanon. Banners and billboards were commissioned in commemoration of the war, along with various merchandise items with Hezbollah's logo, flag color (yellow), and images of Nasrallah. T-shirts, baseball caps and other war memorabilia were marketed for all ages. The uniformity of messaging helped define Hezbollah's brand.[75] In the journalistic context, advertisements evolved from the traditional commercial advertisements to include also a new type in the form of paid articles or broadcasts disguised as news. These generally present an issue in a very subjective and often misleading light, primarily meant to persuade rather than inform. Normally they use only subtle propaganda techniques and not the more obvious ones used in traditional commercial advertisements. If the reader believes that a paid advertisement is in fact a news item, the message the advertiser is trying to communicate will be more easily "believed" or "internalized". Such advertisements are considered obvious examples of "covert" propaganda because they take on the appearance of objective information rather than the appearance of propaganda, which is misleading. Federal law[where?] specifically mandates that any advertisement appearing in the format of a news item must state that the item is in fact a paid advertisement. Edmund McGarry illustrates that advertising is more than selling to an audience but a type of propaganda that is trying to persuade the public and not to be balanced in judgement.[76] |

種類 北朝鮮の小学校に掲示された、アメリカ軍を標的としたポスター。朝鮮語のテキストには「こいつらを捕まえるゲームをしているのか?」と書かれている。 プロパガンダの特定は常に問題となってきた。[46] 主な困難は、プロパガンダを他の説得手法と区別すること、そして偏ったアプローチを避けることにあった。リチャード・アラン・ネルソンはこの用語を次のよ うに定義している:「プロパガンダとは、中立的に定義すれば、大衆メディアや直接メディアを通じて一方的なメッセージ(事実に基づく場合もそうでない場合 もある)を制御的に伝達し、特定の標的集団の感情、態度、意見、行動をイデオロギー、政治的、商業的目的[47]で影響を与えようとする、体系的な意図的 説得の形態である」 この定義は、関与するコミュニケーション過程、より正確にはその過程の目的を焦点としており、視聴者の視点によって「プロパガンダ」を肯定的または否定的 な行為として解釈することを可能にする。 プロパガンダは、その設計に用いられる修辞的戦略によってしばしば認識できる。1930年代、プロパガンダ分析研究所は当時のマスメディアである新聞やラ ジオで多用された様々なプロパガンダ技法を特定した。これには「名指し攻撃」(蔑称の使用)、「バンドワゴン効果」(メッセージの社会的訴求力の強調)、 「華麗な一般論」(肯定的だが曖昧な表現の使用)などが含まれる。[49] インターネットとソーシャルメディアの台頭に伴い、レニー・ホブズは現代のプロパガンダの多くの形態に共通する四つの特徴的な設計要素を特定した:(1) 強い感情を喚起する、(2) 情報を単純化する、(3) 対象となる聴衆の希望、恐怖、夢に訴えかける、(4) 反対者を攻撃する。[50] プロパガンダは、作成した個人や組織の意図と目標に基づいて評価されることがある。歴史家ズビネク・ゼマンによれば、プロパガンダは白、灰、黒の三種類に 分類される。白プロパガンダは情報源と意図を公然と明かす。灰プロパガンダは情報源や意図が曖昧、あるいは非公開である。ブラックプロパガンダは、実際の 発信元とは異なる敵対勢力や組織によるものだと偽装する[51](支援政府の正体を隠す秘密作戦であるブラックオペレーションと比較せよ)。規模の面で は、これらのプロパガンダ類型は、真実かつ正確な情報がプロパガンダと競合する可能性によっても定義される。例えば、ホワイトプロパガンダへの反論は容易 に見つかり、プロパガンダ発信元の信用を多少損なうことがある。グレープロパガンダへの反論は、内部情報源によって暴露された場合、一定の社会的非難を生 む可能性がある。ブラックプロパガンダへの反論は往々にして存在せず、暴露自体が危険を伴う。なぜなら、ブラックプロパガンダの戦術や情報源が公に認知さ れれば、そのプロパガンダ活動自体が弱体化したり、逆効果を招いたりするからである。 プロパガンダ担当者は、特定利益集団にとって望ましい形で人民の行動や期待を変えるため、問題や状況に対する人民の理解の仕方を変えようとする。この意味 でのプロパガンダは、検閲の補完的役割を果たす。検閲は承認された情報で人民の心を満たすのではなく、反対意見に直面する機会を遮断することで同じ目的を 達成するのだ。プロパガンダが他の形の擁護活動と一線を画すのは、プロパガンダを行う者が、説得や理解ではなく、欺瞞や混乱によって人民の理解を変えよう とする意志を持っている点である。組織の指導者は、その情報が一方的あるいは虚偽であることを知っているが、プロパガンダの普及を支援する一般メンバーは そうではないかもしれない。  ルーカス・クラナッハによる、マーティン・ルターが依頼した、パプストスポットビルダー(Papstspotbilder)または英語では「教皇の描写 (Depictions of the Papacy)」として知られる木版画(1545年)。タイトルは「教皇の足に口づけする(Kissing the Pope's Feet)」。ドイツの農民たちが、教皇パウロ3世の教皇勅書に応えている。キャプションには「教皇よ、お前の追放令で我々を怖がらせたり、そんなに怒っ たりするな。さもないと、我々は振り返ってお前にお尻を見せるぞ」と書かれている[55][56]。 宗教 プロパガンダは、特にローマカトリック教会とプロテスタント教会が分裂した時期や十字軍遠征の時期など、宗教問題に関する意見や信念に影響を与えるためによく利用された。[57] 社会学者ジェフリー・K・ハデンは、反カルト運動やキリスト教反カルト運動の参加者が、カルトと見なす集団の指導者たちに対し、信者を勧誘し維持するため にプロパガンダを多用していると非難していると論じている。ハデンは、カルトの元信者や反カルト運動の参加者は、こうした運動を悪く見せようと固執してい ると主張した。[58] 同一コミュニティ内での他宗教に対するプロパガンダ、あるいは宗教的エリート層による政治権力掌握を目的としたプロパガンダは、世界規模あるいは国民規模 で宗教的憎悪を煽り立てる可能性がある。その際、多様なプロパガンダ媒体が活用されうる。戦争、テロリズム、暴動、その他の暴力行為が結果として生じう る。また、不正、不平等、搾取、残虐行為を隠蔽し、無知に基づく無関心や疎外感をもたらすこともある。[59] 戦時 この節は検証可能な情報源を要する。信頼できる出典を追加して、この記事を改善してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。(2021年4月)(このメッセージの削除方法と時期について)  プロパガンダの有名な例として、ポール・リビアが制作したこのポスターは、ボストン虐殺事件をアメリカ人の怒りを煽り独立戦争を支持させるよう意図した形で描いている。 ペロポネソス戦争では、アテナイ人はトロイア伝説の人物やその他の神話的イメージを利用してスパルタに対する感情を煽った。例えばトロイアのヘレネーはア テナイ人として描かれ、その母ネメシスはトロイアの復讐を果たすとされた[60][61]。ポエニ戦争では、双方によって大規模なプロパガンダ作戦が展開 された。ローマの同盟国制度とギリシャのポリスを解体するため、ハンニバルは寛大に扱ったラティウムの捕虜を無条件で故郷に帰還させた。彼らは現地でハン ニバルの宣伝活動を拡散した[62]。一方ローマ側は、ハンニバルを非人道的な人格として描き、やがて神々の寵愛を失うと主張した。同時にクィントゥス・ ファビウス・マクシムスの主導で、ローマの士気を守るための精巧な宗教儀礼を組織した[63]。[62] 16世紀初頭、マクシミリアン1世は敵を対象とした一種の心理戦を考案した。ヴェネツィアとの戦争中、彼は凧にパンフレットを結び付け、自軍の弓兵に撃墜させた。その内容は自由と平等を説き、民衆に専制者(彼らのシニョーリア)への反乱を煽るものだった。[22]  プロパガンダポスターには、ヘルメットに「軍国主義」と書かれた恐ろしいゴリラが描かれている。血まみれの棍棒に「文化」と記され、半裸の女性を抱えながら、アメリカの海岸へ踏み込もうとしている。 この狂った野獣を滅ぼせ:志願せよ——第一次世界大戦中、アメリカ人男性にドイツとの戦いに志願するよう促すプロパガンダポスター。ハリー・R・ホップス作、1917年頃  ソビエトの「ネ・ボルタイ」ポスター。直訳は「おしゃべりするな」。アメリカの「口は災いの元」ポスターと同様、この象徴的なプロパガンダは市民に秘密漏洩を警告しようとしている。 プロパガンダは戦争における強力な武器だ。特定の状況では、兵士や市民の心に虚偽のイメージを植え付けることで、内外の敵とされる存在を非人間化し、憎悪 を煽るために用いられる。これは蔑称や人種差別用語(例:第二次世界大戦時の「ジャップ」、ベトナム戦争時の「グック」といった差別用語)の使用、特定の 言葉や言語の回避、敵の残虐行為の主張によって達成される。目的は、投影された内容が真実だと相手に思わせ、士気を低下させることだ。[64] 戦時におけるプロパガンダの多くは、自国民に「敵が不当な行為を行った」という認識を持たせる必要がある。これは虚構でも事実に基づくものでもよい(例: 第一次世界大戦中のドイツ海軍による客船ルシタニア号沈没事件)。同時に自国民の「自国の戦争参加は正当である」という信念も必要だ。こうしたプロパガン ダが実際に戦争に与えた影響の正確性を判断するのは困難であった。[65] NATOの教義では、プロパガンダは「政治的主張や見解を推進するために用いられる情報、特に偏った、あるいは誤解を招く性質のもの」と定義されている。 [66] この観点では、提供される情報は必ずしも虚偽である必要はなく、むしろそれを実行する「主体」や「システム」の特定の目標に関連していなければならない。 プロパガンダは心理戦の手段の一つでもあり、偽旗作戦(工作員の正体を敵国民と偽装する作戦)を伴う場合もある(例:ピッグス湾侵攻ではキューバ空軍の マーキングを施したCIA機が使用された)。プロパガンダという用語は、既にプロパガンダ発信者の望む考え方を信じている人々を強化するための虚偽情報も 指すことがある(例:第一次世界大戦中、英国プロパガンダの主目的は男性に軍隊への参加を、女性に国内産業での労働を促すことだった。当時は一般向けラジ オ放送が始まっておらず、テレビ技術も開発途上だったため、プロパガンダポスターが用いられた)。[67] 虚偽を信じる者は常に疑念に苛まれるという前提がある。こうした疑念は不快であるため(認知的不協和参照)、人民はそれを消し去ろうと躍起になり、権力者 の安心材料を受け入れやすくなる。このためプロパガンダは、提示される政策や見解に既に共感している層を主な対象とする場合が多い。この強化プロセスは、 個人が「好ましい」情報源を自ら選択する傾向を利用し、集団支配を維持するメカニズムとして機能する。[不適切な合成?]   ボスニア戦争(1992-95年)におけるセルビアのプロパガンダ。画像下部の説明文が示す通り、「ボスニア・ムスリムに家族全員を殺害されたセルビア人 少年」の現場写真として提示された。この画像は、ウロシュ・プレディッチによる1879年の絵画『母の墓前の孤児』(右図)を流用したものである。 [68] プロパガンダは陰険な方法で施されることもある。例えば、特定の集団や外国の歴史に関する誹謗中傷的な偽情報が、教育制度の中で奨励されたり容認されたり する可能性がある。学校で学んだことを実際に再確認する人民はほとんどいないため、こうした偽情報はジャーナリストや親によって繰り返し伝えられ、その結 果、その偽情報が「周知の事実」であるという認識が強化される。たとえその神話を繰り返す者が誰も信頼できる情報源を提示できなくてもだ。こうして虚偽情 報はメディアや教育システムで再生産され、政府が直接メディアに介入する必要すらなくなる。こうした浸透型プロパガンダは政治的目標に利用される:国民に 自国の質や政策について誤った印象を与えることで、特定の提案や発言を拒否させたり、他者の経験を無視させたりできるのだ。  ブリタニアとアンクル・サムが腕を組む姿は、第一次世界大戦における英米同盟を象徴している。  ウィンストン・チャーチルを「英国ブルドッグ」として描いたポスター 第二次世界大戦中のソ連では、民間人を鼓舞するためのプロパガンダはスターリンによって統制されていた。スターリンは強引な手法を主張したが、教育を受け た聴衆はそれが不自然だと容易に見抜いた。一方、ドイツ軍の残虐行為に関する非公式な噂は根拠があり説得力があった[69]。スターリンはグルジア人で、 ロシア語に強い訛りがあった。国民的英雄としてこれは不適切だったため、1930年代以降、スターリンの新たな肖像画は全て修正され、グルジア人の顔の特 徴[明確化]が消去され[70]、より一般的なソ連の英雄像に作り変えられた。彼の目と有名な口ひげだけが変更されなかった。ジョレス・メドヴェージェフ とロイ・メドヴェージェフは、彼の「威厳ある新たなイメージは、あらゆる時代とあらゆる人民の指導者を描くのにふさわしく考案された」と述べている [71]。 市民的及び政治的権利に関する国際規約第20条は、戦争を扇動するあらゆるプロパガンダ、ならびに差別、敵意または暴力への扇動を構成する民族的または宗教的憎悪の助長を法律で禁止している。[72] 当然ながら、一般の人民は戦争を望まない。ロシアでも、イギリスでも、アメリカでも、ましてやドイツでもそうだ。それは理解できる。しかし結局のところ、 政策を決定するのは国家の指導者たちであり、民主主義であれファシスト独裁であれ、議会制であれ共産主義独裁であれ、民衆を従わせることは常に容易なこと だ。人民は常に指導者の意のままに操れる。それは容易い。ただ「自国が攻撃されている」と告げ、平和主義者を「愛国心に欠け国を危険に晒している」と非難 すればよい。どの国でも同じように機能する。 —ヘルマン・ゲーリング[73] 簡単に言えば、この条約はプロパガンダの内容を具体的に定義していない。最も簡単に言えば、戦時中の行為への対応としてプロパガンダ行為が行われた場合、それは禁止されないということだ[74]。 広告 プロパガンダは、広告や広報と手法を共有している。それぞれは、商業製品を宣伝したり、組織、人格、ブランドの認識を形成したりするプロパガンダと考える ことができる。例えば、2006年のレバノン戦争で勝利を宣言した後、ヒズボラは、レバノン国外の聴衆にも届くよう、ヒズボラの指導者ハッサン・ナスララ が現地の方言と古典アラビア語を組み合わせて大衆集会を開催し、アラブ諸国での人気拡大を図った。戦争を記念して、ヒズボラのロゴ、旗の色(黄色)、ナス ララの画像をあしらったさまざまな商品とともに、バナーや看板が制作された。Tシャツ、野球帽、その他の戦争記念品は、あらゆる年齢層向けに販売された。 メッセージの一貫性は、ヒズボラのブランドを定義するのに役立った。[75]ジャーナリズムの文脈では、広告は従来の商業広告から進化し、ニュースを装っ た有料記事や放送という新しい形態も取り入れるようになった。これらは一般的に、非常に主体的で、しばしば誤解を招くような観点から問題を取り上げ、主に 情報を提供するというよりも説得を目的としている。 通常、こうした広告は伝統的な商業広告で用いられる露骨な手法ではなく、より巧妙なプロパガンダ技法を用いる。読者が有料広告をニュース記事と誤認した場 合、広告主が伝えようとするメッセージはより容易に「信じられる」あるいは「内面化される」ことになる。こうした広告は、プロパガンダという誤解を招く外 観ではなく客観的情報の外観を装うため、「隠蔽された」プロパガンダの典型例と見なされる。連邦法[どこで?]は、ニュース記事形式で掲載される広告は、 それが実際には有料広告であることを明記するよう特に義務付けている。 エドマンド・マッギャリーは、広告は単に観客に売る行為ではなく、公衆を説得しようとし、判断において公平であるべきではない一種のプロパガンダであると示している。[76] |

Politics Propaganda and manipulation can be found in television, and in news programs that influence mass audiences. An example was the Dziennik (Journal) news cast, which criticised capitalism in the then-communist Polish People's Republic using emotive and loaded language. Propaganda has become more common in political contexts, in particular, to refer to certain efforts sponsored by governments, political groups, but also often covert interests. In the early 20th century, propaganda was exemplified in the form of party slogans. Propaganda also has much in common with public information campaigns by governments, which are intended to encourage or discourage certain forms of behavior (such as wearing seat belts, not smoking, not littering, and so forth). Again, the emphasis is more political in propaganda. Propaganda can take the form of leaflets, posters, TV, and radio broadcasts and can also extend to any other medium. In the case of the United States, there is also an important legal (imposed by law) distinction between advertising (a type of overt propaganda) and what the Government Accountability Office (GAO), an arm of the United States Congress, refers to as "covert propaganda." Propaganda is divided into two in political situations, they are preparation, meaning to create a new frame of mind or view of things, and operational, meaning they instigate actions.[77] Roderick Hindery argues[78][79] that propaganda exists on the political left, and right, and in mainstream centrist parties. Hindery further argues that debates about most social issues can be productively revisited in the context of asking "what is or is not propaganda?" Not to be overlooked is the link between propaganda, indoctrination, and terrorism/counterterrorism. He argues that threats to destroy are often as socially disruptive as physical devastation itself. Since 9/11 and the appearance of greater media fluidity, propaganda institutions, practices and legal frameworks have been evolving in the US and Britain. Briant shows how this included expansion and integration of the apparatus cross-government and details attempts to coordinate the forms of propaganda for foreign and domestic audiences, with new efforts in strategic communication.[80] These were subject to contestation within the US Government, resisted by Pentagon Public Affairs and critiqued by some scholars.[43] The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 (section 1078 (a)) amended the US Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 (popularly referred to as the Smith-Mundt Act) and the Foreign Relations Authorization Act of 1987, allowing for materials produced by the State Department and the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) to be released within U.S. borders for the Archivist of the United States. The Smith-Mundt Act, as amended, provided that "the Secretary and the Broadcasting Board of Governors shall make available to the Archivist of the United States, for domestic distribution, motion pictures, films, videotapes, and other material 12 years after the initial dissemination of the material abroad (...) Nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit the Department of State or the Broadcasting Board of Governors from engaging in any medium or form of communication, either directly or indirectly, because a United States domestic audience is or may be thereby exposed to program material, or based on a presumption of such exposure." Public concerns were raised upon passage due to the relaxation of prohibitions of domestic propaganda in the United States.[81] In the wake of this, the internet has become a prolific method of distributing political propaganda, benefiting from an evolution in coding called bots. Software agents or bots can be used for many things, including populating social media with automated messages and posts with a range of sophistication. During the 2016 U.S. election a cyber-strategy was implemented using bots to direct US voters to Russian political news and information sources, and to spread politically motivated rumors and false news stories. At this point it is considered commonplace contemporary political strategy around the world to implement bots in achieving political goals.[82] |

政治 テレビや大衆に影響を与えるニュース番組には、プロパガンダや操作が見られる。一例が『ディエニク(ジャーナル)』ニュース番組だ。当時の共産主義国家ポーランド人民共和国で、感情的な言葉や偏った表現を用いて資本主義を批判していた。 プロパガンダは政治的文脈でより一般的になり、特に政府や政治団体が支援する特定の取り組みを指すことが多いが、しばしば隠れた利害関係も含まれる。20 世紀初頭、プロパガンダは政党のスローガンという形で具体化された。プロパガンダは政府による公共情報キャンペーンとも多くの共通点があり、特定の行動 (シートベルト着用、禁煙、ポイ捨て禁止など)を奨励または抑制することを目的としている。繰り返しになるが、プロパガンダでは政治的側面がより強調され る。プロパガンダはビラ、ポスター、テレビ・ラジオ放送などの形態をとり、あらゆる媒体に拡大しうる。米国の場合、広告(一種の表向きのプロパガンダ) と、米国議会傘下の政府監査院(GAO)が「隠れたプロパガンダ」と呼ぶものとの間には、重要な法的(法律で定められた)区別が存在する。プロパガンダは 政治状況下で二分される。準備段階(新たな思考様式や物事の見方を形成する)と実行段階(行動を促す)である[77]。 ロデリック・ヒンダリーは[78][79]、プロパガンダは政治的左派、右派、そして主流の中道政党にも存在すると主張する。ヒンダリーはさらに、ほとん どの社会問題に関する議論は「何がプロパガンダであり、何がそうでないか」という問いかけの文脈で再検討すれば生産的だと主張する。プロパガンダと教化、 そしてテロリズム/対テロリズムとの関連性も見逃せない。彼は、破壊の脅威は物理的破壊そのものと同等に社会を混乱させると論じる。 9.11以降、メディアの流動性が高まる中、米国と英国ではプロパガンダの制度・実践・法的枠組みが進化してきた。ブライアントは、これが政府横断的な機 構の拡大・統合を含むことを示し、戦略的コミュニケーションにおける新たな取り組みと共に、国内外の聴衆に向けたプロパガンダの形態を調整しようとする試 みを詳述している[80]。これらは米政府内で争点となり、国防総省広報局に抵抗され、一部の学者から批判された。[43] 2013会計年度国防授権法(第1078条(a)項)は、1948年米国情報教育交流法 (通称スミス・マンド法)及び1987年外交関係授権法を改正し、国務省及び放送理事会(BBG)が制作した資料を米国国内で公開することを米国公文書記 録管理庁長官に認めた。改正後のスミス・マンド法は、「国務長官及び放送理事会は、海外での初回配布から12年を経過した映画、フィルム、ビデオテープそ の他の資料を、国内配布のために米国公文書館長に提供しなければならない」と規定している。本条のいかなる規定も、米国国内の視聴者が番組素材に接触する 可能性がある、あるいは接触した可能性があるという推定に基づき、国務省または放送理事会が直接的または間接的にあらゆる媒体や通信形態を利用することを 禁止するものと解釈してはならない。」この改正により国内向けプロパガンダの規制が緩和されたため、成立時には公衆の懸念が表明された。[81] この流れを受け、インターネットは政治的プロパガンダを拡散する有力な手段となった。これは「ボット」と呼ばれるコーディング技術の進化を背景としてい る。ソフトウェアエージェントやボットは多様な用途に利用可能であり、ソーシャルメディアへの自動投稿や、様々な高度な自動メッセージの拡散などが含まれ る。2016年の米国大統領選挙では、ボットを用いたサイバー戦略が実施された。これは米国有権者をロシアの政治ニュース・情報源へ誘導し、政治的動機に 基づく噂や虚偽のニュース記事を拡散する目的であった。現在では、政治的目標達成のためにボットを活用することは、世界的に一般的な現代政治戦略と見なさ れている。[82] |

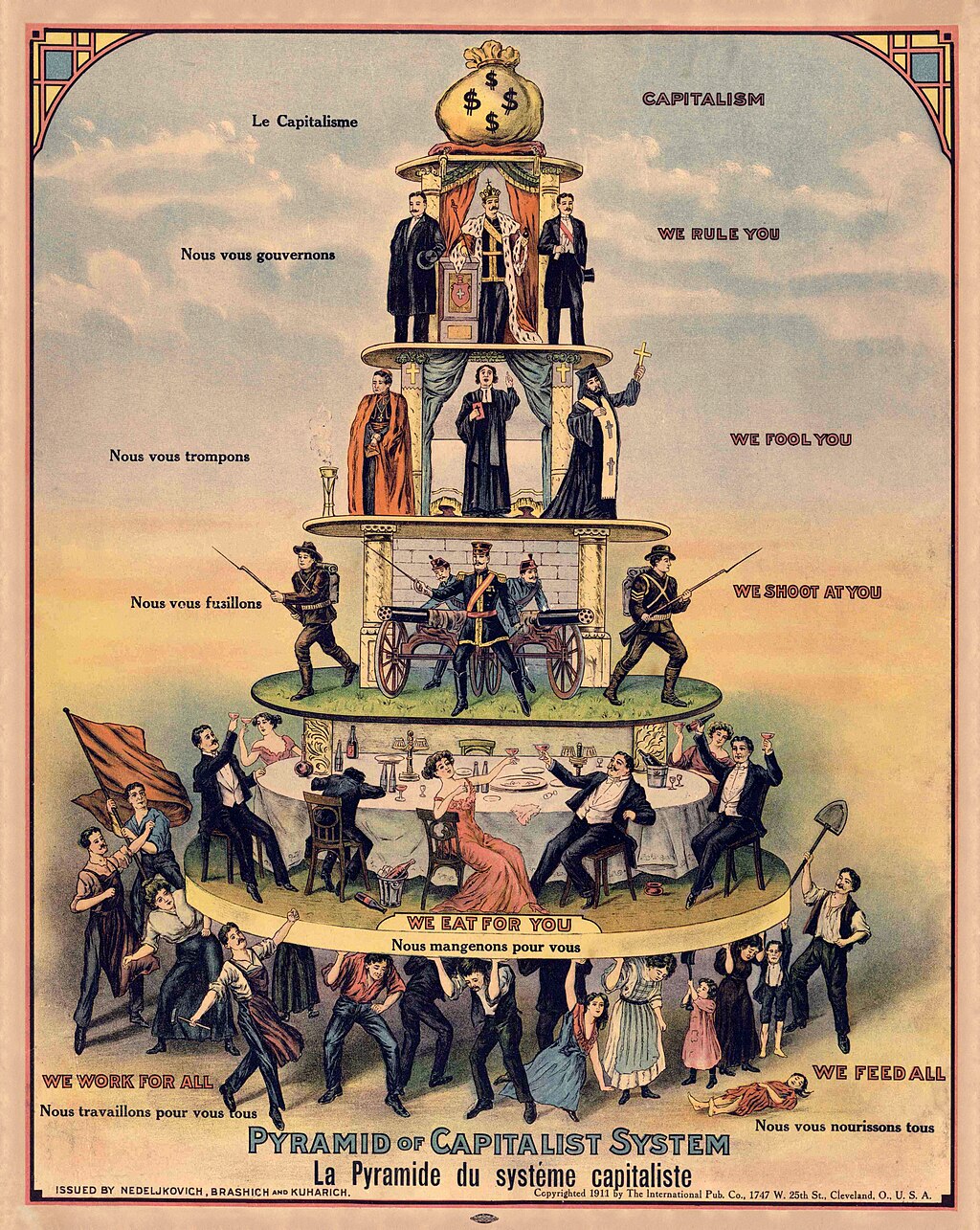

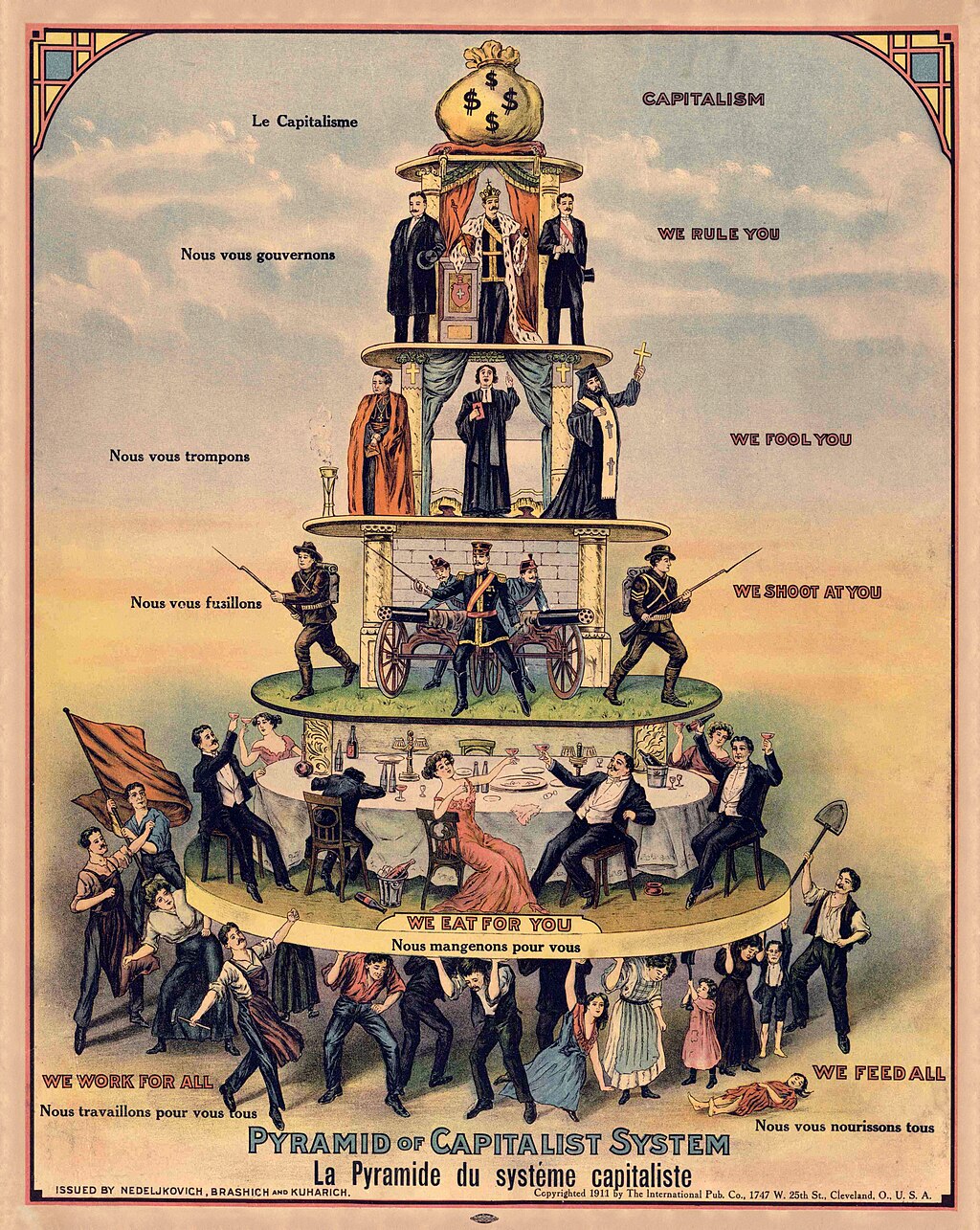

| Techniques Further information: Propaganda techniques  Anti-capitalist propaganda (1911 Industrial Workers of the World poster) Common media for transmitting propaganda messages include news reports, government reports, historical revision, junk science, books, leaflets, movies, radio, television, posters and social media. Some propaganda campaigns follow a strategic transmission pattern to indoctrinate the target group. This may begin with a simple transmission, such as a leaflet or advertisement dropped from a plane or an advertisement. Generally, these messages will contain directions on how to obtain more information, via a website, hotline, radio program, etc. (as it is seen also for selling purposes among other goals). The strategy intends to initiate the individual from information recipient to information seeker through reinforcement, and then from information seeker to opinion leader through indoctrination.[83] A number of techniques based in social psychological research are used to generate propaganda. Many of these same techniques can be found under logical fallacies, since propagandists use arguments that, while sometimes convincing, are not necessarily valid. Some time has been spent analyzing the means by which the propaganda messages are transmitted. That work is important but it is clear that information dissemination strategies become propaganda strategies only when coupled with propagandistic messages. Identifying these messages is a necessary prerequisite to study the methods by which those messages are spread. Theodor W. Adorno wrote that fascist propaganda encourages identification with an authoritarian personality characterized by traits such as obedience and extreme aggression.[84]: 17 In The Myth of the State, Ernst Cassirer wrote that while fascist propaganda mythmaking flagrantly contradicted empirical reality, it provided a simple and direct answer to the anxieties of the secular present.[84]: 63 Propaganda can also be turned on its makers. For example, postage stamps have frequently been tools for government advertising, such as North Korea's extensive issues.[85] The presence of Stalin on numerous Soviet stamps is another example.[86] In Nazi Germany, Hitler frequently appeared on postage stamps in Germany and some of the occupied nations. A British program to parody these, and other Nazi-inspired stamps, involved airdropping them into Germany on letters containing anti-Nazi literature.[87][88] In 2018 a scandal broke in which the journalist Carole Cadwalladr, several whistleblowers and the academic Emma Briant revealed advances in digital propaganda techniques showing that online human intelligence techniques used in psychological warfare had been coupled with psychological profiling using illegally obtained social media data for political campaigns in the United States in 2016 to aid Donald Trump by the firm Cambridge Analytica.[89][90][91] The company initially denied breaking laws[92] but later admitted breaking UK law, the scandal provoking a worldwide debate on acceptable use of data for propaganda and influence.[93] |

手法 詳細情報:プロパガンダの手法  反資本主義プロパガンダ(1911年 産業労働者組合ポスター) プロパガンダメッセージを伝達する一般的な媒体には、ニュース報道、政府報告書、歴史改竄、疑似科学、書籍、ビラ、映画、ラジオ、テレビ、ポスター、ソー シャルメディアなどがある。一部のプロパガンダキャンペーンは、対象集団を洗脳するための戦略的な伝達パターンに従う。これは、飛行機から投下されるビラ や広告といった単純な伝達から始まる場合がある。一般的に、これらのメッセージには、ウェブサイト、ホットライン、ラジオ番組などを通じて、より多くの情 報を得る方法が記載されている(販売目的など他の目標でも見られるように)。この戦略は、強化を通じて個人を情報受容者から情報探索者へと移行させ、その 後、教化を通じて情報探索者からオピニオンリーダーへと移行させることを意図している。[83] プロパガンダ生成には社会心理学研究に基づく手法が数多く用いられる。これらの手法の多くは論理的誤謬にも該当する。プロパガンダ担当者は、時に説得力を持つものの必ずしも妥当ではない論理を用いるからだ。 プロパガンダメッセージの伝達手段を分析する研究は進められてきた。この研究は重要だが、情報拡散戦略がプロパガンダ戦略となるのは、プロパガンダ的メッ セージと結びついた場合のみであることは明らかだ。これらのメッセージを特定することは、その拡散方法を研究する上で必要な前提条件である。 テオドール・W・アドルノは、ファシストのプロパガンダが、服従や極端な攻撃性といった特徴を持つ権威主義的人格への同一化を促すと記した。[84]: 17 『国家の神話』においてエルンスト・カッシラーは、ファシストのプロパガンダが作り出す神話が経験的現実と露骨に矛盾する一方で、世俗的な現代の不安に対 して単純かつ直接的な答えを提供したと記している。[84]: 63 プロパガンダは作り手自身に向けられることもある。例えば切手は政府広告の道具として頻繁に利用され、北朝鮮の大量発行が典型例だ。[85] ソ連切手に頻繁に描かれたスターリンも同様である。[86] ナチス・ドイツでは、ヒトラーがドイツ及び占領下の諸国民で発行された切手に頻繁に登場した。英国はこれらや他のナチス風切手を揶揄する計画の一環とし て、反ナチス文書を同封した手紙に貼り付け、ドイツへ空投した。[87] [88] 2018年、ジャーナリストのキャロル・キャドワラドル、複数の内部告発者、学者エマ・ブライアントが、デジタルプロパガンダ技術の進歩を明らかにするス キャンダルが勃発した。それによると、2016年の米国大統領選挙において、ケンブリッジ・アナリティカ社が、心理戦に使用されるオンラインの人間知能技 術を、違法に入手したソーシャルメディアデータを用いた心理プロファイリングと組み合わせ、ドナルド・トランプ氏を支援していたことが明らかになった。 [89][90] [91] 同社は当初、法律違反を否定していた[92]が、後に英国法の違反を認めた。このスキャンダルは、プロパガンダや影響力行使のためのデータ利用の許容範囲 について、世界的な議論を引き起こした。[93] |

| Models Persuasion in social psychology  Public reading of the anti-Semitic newspaper Der Stürmer, Worms, Germany, 1935 The field of social psychology includes the study of persuasion. Social psychologists can be sociologists or psychologists. The field includes many theories and approaches to understanding persuasion. For example, communication theory points out that people can be persuaded by the communicator's credibility, expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. The elaboration likelihood model, as well as heuristic models of persuasion, suggest that a number of factors (e.g., the degree of interest of the recipient of the communication), influence the degree to which people allow superficial factors to persuade them. Nobel Prize–winning psychologist Herbert A. Simon won the Nobel prize for his theory that people are cognitive misers. That is, in a society of mass information, people are forced to make decisions quickly and often superficially, as opposed to logically. According to William W. Biddle's 1931 article "A psychological definition of propaganda", "[t]he four principles followed in propaganda are: (1) rely on emotions, never argue; (2) cast propaganda into the pattern of "we" versus an "enemy"; (3) reach groups as well as individuals; (4) hide the propagandist as much as possible."[94] More recently, studies from behavioral science have become significant in understanding and planning propaganda campaigns, these include for example nudge theory which was used by the Obama Campaign in 2008 then adopted by the UK Government Behavioural Insights Team.[95] Behavioural methodologies then became subject to great controversy in 2016 after the company Cambridge Analytica was revealed to have applied them with millions of people's breached Facebook data to encourage them to vote for Donald Trump.[96] Haifeng Huang argues that propaganda is not always necessarily about convincing a populace of its message (and may actually fail to do this) but instead can also function as a means of intimidating the citizenry and signalling the regime's strength and ability to maintain its control and power over society; by investing significant resources into propaganda, the regime can forewarn its citizens of its strength and deterring them from attempting to challenge it.[97] Propaganda theory and education During the 1930s, educators in the United States and around the world became concerned about the rise of anti-Semitism and other forms of violent extremism. The Institute for Propaganda Analysis was formed to introduce methods of instruction for high school and college students, helping learners to recognize and desist propaganda by identifying persuasive techniques. This work built upon classical rhetoric and it was informed by suggestion theory and social scientific studies of propaganda and persuasion.[98] In the 1950s, propaganda theory and education examined the rise of American consumer culture, and this work was popularized by Vance Packard in his 1957 book, The Hidden Persuaders. European theologian Jacques Ellul's landmark work, Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes framed propaganda in relation to larger themes about the relationship between humans and technology. Media messages did not serve to enlighten or inspire, he argued. They merely overwhelm by arousing emotions and oversimplifying ideas, limiting human reasoning and judgement. In the 1980s, academics recognized that news and journalism could function as propaganda when business and government interests were amplified by mass media. The propaganda model is a theory advanced by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky which argues systemic biases exist in mass media that are shaped by structural economic causes. It argues that the way in which commercial media institutions are structured and operate (e.g. through advertising revenue, concentration of media ownership, or access to sources) creates an inherent conflict of interest that make them act as propaganda for powerful political and commercial interests: The 20th century has been characterized by three developments of great political importance: the growth of democracy, the growth of corporate power, and the growth of corporate propaganda as a means of protecting corporate power against democracy.[99][100] First presented in their book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988), the propaganda model analyses commercial mass media as businesses that sell a product – access to readers and audiences – to other businesses (advertisers) and that benefit from access to information from government and corporate sources to produce their content. The theory postulates five general classes of "filters" that shape the content that is presented in news media: ownership of the medium, reliance on advertising revenue, access to news sources, threat of litigation and commercial backlash (flak), and anti-communism and "fear ideology". The first three (ownership, funding, and sourcing) are generally regarded by the authors as being the most important. Although the model was based mainly on the characterization of United States media, Chomsky and Herman believe the theory is equally applicable to any country that shares the basic political economic structure, and the model has subsequently been applied by other scholars to study media bias in other countries.[101] By the 1990s, the topic of propaganda was no longer a part of public education, having been relegated to a specialist subject. Secondary English educators grew fearful of the study of propaganda genres, choosing to focus on argumentation and reasoning instead of the highly emotional forms of propaganda found in advertising and political campaigns.[102] In 2015, the European Commission funded Mind Over Media, a digital learning platform for teaching and learning about contemporary propaganda. The study of contemporary propaganda is growing in secondary education, where it is seen as a part of language arts and social studies education.[103] Self-propaganda Self-propaganda is a form of propaganda that refers to the act of an individual convincing themself of something, no matter how irrational that idea may be.[104] Self propaganda makes it easier for individuals to justify their own actions as well as the actions of others. Self-propaganda often works to lessen the cognitive dissonance felt by individuals when their personal actions or the actions of their government do not line up with their moral beliefs.[105] Self-propaganda is a type of self deception.[106] Self-propaganda can have a negative impact on those who perpetuate the beliefs created by using self-propaganda.[106] |

モデル 社会心理学における説得  反ユダヤ主義新聞『Der Stürmer』の公的朗読、ドイツ・ヴォルムス、1935年 社会心理学の分野には説得の研究が含まれる。社会心理学者とは社会学者または心理学者を指す。この分野には説得を理解するための多くの理論とアプローチが 存在する。例えば、コミュニケーション理論は、伝達者の信頼性、専門性、誠実さ、魅力によって人民が説得され得ると指摘する。精緻化可能性モデルや説得の ヒューリスティックモデルは、複数の要因(例えば、コミュニケーションの受け手の関心度)が、人民が表面的な要因にどれほど説得されるかに影響すると示唆 している。ノーベル賞受賞心理学者ハーバート・A・サイモンは、人間は認知的倹約家であるという理論でノーベル賞を受賞した。つまり、大量の情報が存在す る社会では、人々は論理的にではなく、迅速に、そしてしばしば表面的判断を下さざるを得ないというのだ。 ウィリアム・W・ビドルの1931年の論文「プロパガンダの心理学的定義」によれば、「プロパガンダが従う四つの原則は次の通りである:(1) 感情に頼り、決して論理で争わない;(2) プロパガンダを『我々』対『敵』の構図に当てはめる;(3) 個人だけでなく集団にも訴えかける;(4) プロパガンダ発信者を可能な限り隠す」[94]。 最近では、行動科学の研究がプロパガンダキャンペーンの理解と計画において重要になってきており、その一例として、2008年のオバマ陣営が採用し、その 後英国政府の行動洞察チームも採用したナッジ理論が挙げられる。[95] その後、2016年にケンブリッジ・アナリティカ社が、何百万人もの人々のFacebookの不正アクセスされたデータを用いて、ドナルド・トランプ氏へ の投票を促していたことが明らかになり、行動科学の手法は大きな論争の対象となった。[96] 黄海峰は、プロパガンダは必ずしも大衆をそのメッセージで説得すること(そして実際にはこれを達成できない場合もある)を目的とするものではなく、市民を 威嚇し、社会に対する支配と権力を維持する体制の力と能力を示す手段としても機能しうる、と主張している。プロパガンダに多大な資源を投資することで、体 制は自国の力を国民に警告し、体制に挑戦しようとする試みを抑止することができるのだ。[97] プロパガンダ理論と教育 1930年代、米国および世界中の教育者は、反ユダヤ主義やその他の形態の暴力的な過激主義の台頭を懸念するようになった。プロパガンダ分析研究所は、高 校生や大学生向けの指導方法を導入し、説得的な手法を特定することで、学習者がプロパガンダを認識し、それを阻止するのを支援するために設立された。この 研究は、古典的な修辞学に基づいており、暗示理論や、プロパガンダと説得に関する社会科学的研究によって裏付けられていた。[98] 1950年代、プロパガンダ理論と教育は、アメリカの消費文化の台頭を検証し、この研究は、ヴァンス・パッカードが1957年に著した『隠された説得者た ち』によって普及した。ヨーロッパの神学者ジャック・エルルの画期的な著作『プロパガンダ:人間の態度の形成』は、人間と技術の関係に関するより大きな テーマに関連してプロパガンダを位置づけた。メディアのメッセージは、啓蒙や刺激には役立たない、と彼は主張した。それらは、感情を刺激し、考えを過度に 単純化することで、人間の理屈や判断を制限し、圧倒するだけである。 1980年代、学者たちは、マスメディアによってビジネスや政府の利益が増幅された場合、ニュースやジャーナリズムはプロパガンダとして機能しうることを 認識した。プロパガンダ・モデルとは、エドワード・S・ハーマンとノーム・チョムスキーが提唱した理論である。これは、構造的な経済的要因によって形成さ れた、マスメディアに存在する体系的な偏りが存在すると主張する。商業メディア機関の構造と運営方法(例:広告収入、メディア所有権の集中、情報源へのア クセス)が、本質的な利益相反を生み出し、それらが強力な政治的・商業的利益のためのプロパガンダとして機能するようになるというのである: 20世紀は三つの政治的に重大な発展によって特徴づけられた。民主主義の拡大、企業権力の拡大、そして民主主義から企業権力を守る手段としての企業プロパガンダの拡大である。[99] [100] このプロパガンダモデルは、彼らの著書『マニピュレーション・オブ・コンセンサス:大衆メディアの政治経済学』(1988年)で初めて提示された。商業的 大衆メディアを、読者や視聴者という商品(アクセス)を他の企業(広告主)に販売するビジネスとして分析し、政府や企業からの情報源へのアクセスを利用し てコンテンツを生産することで利益を得ていると論じる。この理論は、ニュースメディアで提示される内容を形成する5つの一般的な「フィルター」を仮定して いる:メディアの所有形態、広告収入への依存、ニュースソースへのアクセス、訴訟や商業的反発(フラック)の脅威、そして反共主義と「恐怖イデオロギー」 である。著者らは最初の三つ(所有権、資金源、情報源)を最も重要視している。このモデルは主に米国メディアの特徴に基づいて構築されたが、チョムスキー とハーマンは、基本的な政治経済構造を共有するあらゆる国に同理論が適用可能だと主張している。その後、他の研究者もこのモデルを用いて他国のメディアバ イアスを研究している[101]。 1990年代までに、プロパガンダという主題は公教育から外れ、専門分野に追いやられた。中等教育の英語教師はプロパガンダ形式の研究を恐れ、広告や政治 運動に見られる感情的なプロパガンダ形式ではなく、論証や推論に焦点を当てることを選んだ[102]。2015年、欧州委員会は現代のプロパガンダを教え るためのデジタル学習プラットフォーム「Mind Over Media」に資金を提供した。現代プロパガンダの研究は中等教育で拡大しており、言語芸術や社会科学教育の一部と見なされている。[103] 自己プロパガンダ 自己プロパガンダとは、個人がいかに非合理な考えであっても自らを説得する行為を指すプロパガンダの形態である。[104] 自己プロパガンダは、個人が自身の行動や他者の行動を正当化することを容易にする。自己プロパガンダは、人格の行動や政府の行動が自身の道徳的信念と一致 しない場合に生じる認知的不協和を軽減する働きをしばしば持つ。[105]自己プロパガンダは一種の自己欺瞞である。[106]自己プロパガンダは、それ によって生み出された信念を永続させる者たちに悪影響を及ぼしうる。[106] |

| Children This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  A 1938 propaganda of the Estado Novo (New State) regime depicting Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas flanked by children. The text reads: "Children! Learning, at home and in school, the worship of the Fatherland, you will bring all chances of success to life. Only love builds and, strongly loving Brazil, you will lead it to the greatest of destinies among Nations, fulfilling the desires of exaltation nestled in every Brazilian heart." Of all the potential targets for propaganda, children are the most vulnerable because they are the least prepared with the critical reasoning and contextual comprehension they need to determine whether message is a propaganda or not. The attention children give their environment during development, due to the process of developing their understanding of the world, causes them to absorb propaganda indiscriminately. Also, children are highly imitative: studies by Albert Bandura, Dorothea Ross and Sheila A. Ross in the 1960s indicated that, to a degree, socialization, formal education and standardized television programming can be seen as using propaganda for the purpose of indoctrination. The use of propaganda in schools was highly prevalent during the 1930s and 1940s in Germany in the form of the Hitler Youth. Anti-Semitic propaganda for children In Nazi Germany, the education system was thoroughly co-opted to indoctrinate the German youth with anti-Semitic ideology. From the 1920s on, the Nazi Party targeted German youth as one of their special audience for its propaganda messages.[107] Schools and texts mirrored what the Nazis aimed of instilling in German youth through the use and promotion of racial theory. Julius Streicher, the editor of Der Stürmer, headed a publishing house that disseminated anti-Semitic propaganda picture books in schools during the Nazi dictatorship. This was accomplished through the National Socialist Teachers League, of which 97% of all German teachers were members in 1937.[108] The League encouraged the teaching of racial theory. Picture books for children such as Trust No Fox on his Green Heath and No Jew on his Oath, Der Giftpilz (translated into English as The Poisonous Mushroom) and The Poodle-Pug-Dachshund-Pinscher were widely circulated (over 100,000 copies of Trust No Fox... were circulated during the late 1930s) and contained depictions of Jews as devils, child molesters and other morally charged figures. Slogans such as "Judas the Jew betrayed Jesus the German to the Jews" were recited in class. During the Nuremberg Trial, Trust No Fox on his Green Heath and No Jew on his Oath, and Der Giftpilz were received as documents in evidence because they document the practices of the Nazis[109] The following is an example of a propagandistic math problem recommended by the National Socialist Essence of Education: "The Jews are aliens in Germany—in 1933 there were 66,606,000 inhabitants in the German Reich, of whom 499,682 (0.75%) were Jews."[110] |

子供たち この節は検証可能な情報源を必要としている。信頼できる情報源をこの節に追加して、記事の改善に協力してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。(2009年1月)  1938年、エスタド・ノヴォ(新国家)政権の宣伝画。ゲトゥリオ・ヴァルガス大統領を子供たちが囲んでいる。文面はこうだ:「子供たちよ!家庭と学校で 祖国崇拝を学び、人生に成功のあらゆる可能性をもたらせ。愛のみが築く。ブラジルを強く愛し、国民の中で最も偉大な運命へと導け。すべてのブラジル人の心 に宿る高揚の願いを成就させよ」 プロパガンダの潜在的な対象の中で、子供たちは最も脆弱だ。なぜなら、メッセージがプロパガンダかどうかを判断するために必要な批判的思考や文脈理解が最 も未熟だからである。世界理解を発達させる過程で、子供たちが周囲に注ぐ注意力は、プロパガンダを無差別に吸収させる。また子供は模倣性が極めて高い。 1960年代のアルバート・バンデューラ、ドロシア・ロス、シーラ・A・ロスの研究は、社会化や正式な教育、標準化されたテレビ番組が、ある程度の洗脳目 的でプロパガンダを利用していると指摘している。1930~40年代のドイツでは、ヒトラーユーゲントという形で学校におけるプロパガンダ利用が広く行わ れていた。 子供向け反ユダヤ主義プロパガンダ ナチス・ドイツでは、教育制度が徹底的に利用され、ドイツの若者に反ユダヤ主義イデオロギーを洗脳した。1920年代以降、ナチ党はプロパガンダメッセー ジの特別な対象としてドイツの若者を狙った[107]。学校と教科書は、人種理論の活用と推進を通じてナチスがドイツの若者に植え付けようとしたものを反 映していた。『シュトゥルマー』紙の編集長ユリウス・シュトライヒャーは、ナチス独裁政権下で学校向けに反ユダヤ主義プロパガンダ絵本を普及させた出版社 のトップであった。これは国家社会主義教師連盟を通じて達成され、1937年には全ドイツ教師の97%が同連盟に所属していた[108]。 同連盟は人種理論の教育を奨励した。子供向け絵本『緑の荒野の狐を信じるな』『誓いを立てるユダヤ人を信じるな』『毒キノコ』(英語訳『The Poisonous Mushroom』)、『プードル・パグ・ダックスフント・ピンシャー』などが広く流通した(『緑の荒野の狐を信じるな…』は1930年代後半に10万部 以上流通)。これらの絵本にはユダヤ人を悪魔、児童虐待者、その他の道徳的に問題のある人物として描いた図版が含まれていた。「ユダヤ人ユダはドイツ人イ エスをユダヤ人に売った」といったスローガンも掲載されていた。1930年代後半に10万部以上流通した)には、ユダヤ人を悪魔や小児性愛者など道徳的に 非難される存在として描いた挿絵が含まれていた。「ユダヤ人ユダはドイツ人イエスをユダヤ人に売った」といったスローガンが教室で唱和された。ニュルンベ ルク裁判では、『緑の丘の狐を信じるな』『誓いを立てるユダヤ人を信じるな』『毒キノコ』が証拠書類として採用された。これらはナチスの実践を記録した資 料だからだ [109] 以下は国家社会主義教育本旨が推奨したプロパガンダ的算数問題の一例である:「ユダヤ人はドイツにおける異邦人である―1933年当時、ドイツ帝国の人口 は66,606,000人で、そのうち499,682人(0.75%)がユダヤ人であった」[110] |

| Comparisons with disinformation This section is an excerpt from Disinformation § Comparisons with propaganda.[edit] Whether and to what degree disinformation and propaganda overlap is subject to debate. Some (like U.S. Department of State) define propaganda as the use of non-rational arguments to either advance or undermine a political ideal, and use disinformation as an alternative name for undermining propaganda,[111][page needed] while others consider them to be separate concepts altogether.[112] One popular distinction holds that disinformation also describes politically motivated messaging designed explicitly to engender public cynicism, uncertainty, apathy, distrust, and paranoia, all of which disincentivize citizen engagement and mobilization for social or political change.[113] |

偽情報との比較 この節は『偽情報』の「プロパガンダとの比較」節からの抜粋である。[編集] 偽情報とプロパガンダがどの程度重なるかは議論の余地がある。米国務省など一部は、プロパガンダを「非合理的な議論を用いて政治的理想を推進または弱体化 させる行為」と定義し、偽情報を「弱体化させるプロパガンダの別名」と位置付ける[111][出典ページ不明]。一方、両者を全く別の概念と考える立場も ある。[112] 一般的な区別として、偽情報はさらに、公衆の懐疑心、不確実性、無関心、不信感、偏執を意図的に醸成する政治的動機に基づくメッセージングを指す。これら は全て、市民の社会・政治的変革への関与や動員を阻害するものである。[113] |

| Agitprop Artificial intelligence and elections Big lie Brainwashing Cartographic propaganda Firehose of falsehood Hate media Incitement Internet troll Mind control Misinformation Music and political warfare Overview of 21st century propaganda Political warfare Psychological warfare (aka Psyops) Propaganda model Public diplomacy Sharp power Smear campaign Spin (propaganda) The Basic Principles of War Propaganda |

アジプロ 人工知能と選挙 大嘘 洗脳 地図によるプロパガンダ 虚偽の洪水 憎悪メディア 扇動 インターネット・トロール マインドコントロール 誤情報 音楽と政治戦争 21世紀のプロパガンダ概観 政治戦争 心理作戦(通称:サイオプス) プロパガンダモデル 公共外交 シャープパワー 中傷キャンペーン スピン(プロパガンダ) 戦争プロパガンダの基本原則 |

| Sources "Appendix I: PSYOP Techniques". Psychological Operations Field Manual No. 33-1. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. 31 August 1979. Archived from the original on 24 May 2001. Bytwerk, Randall L. (2004). Bending Spines: The Propagandas of Nazi Germany and the German Democratic Republic. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87013-710-5. Edwards, John Carver (1991). Berlin Calling: American Broadcasters in Service to the Third Reich. New York: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-93905-2. Füssel, Stephan (2020). Gutenberg and the Impact of Printing. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-93187-8. Hindery, Roderick. "The Anatomy of Propaganda within Religious Terrorism". Humanist (March–April 2003): 16–19. Howe, Ellic (1982). The Black Game: British Subversive Operations Against the German During the Second World War. London: Futura. Huxley, Aldous (1989) [1958]. Brave New World Revisited. New York: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-080984-3. Jowett, Garth S.; O'Donnell, Victoria (2006). Propaganda and Persuasion (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4129-0897-9. Le Bon, Gustave (1977) [1895]. The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-004531-4. Linebarger, Paul M. A. (1972) [1948]. Psychological Warfare. Washington, D.C.: Infantry Journal Press. ISBN 978-0-405-04755-8. Nelson, Richard Alan (1996). A Chronology and Glossary of Propaganda in the United States. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-29261-3. Shirer, William L. (2002) [1941]. Berlin Diary: The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent, 1934–1941. New York: Albert A. Knopf. ISBN 978-5-9524-0081-8. Young, Emma (10 October 2001). "Psychological warfare waged in Afghanistan". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 13 February 2002. Retrieved 5 August 2010. |

出典 「付録I:心理作戦技術」。心理作戦野戦マニュアル第33-1号。ワシントンD.C.:陸軍省。1979年8月31日。2001年5月24日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。 バイトワーク、ランドール・L.(2004)。『背骨を曲げる:ナチス・ドイツとドイツ民主共和国のプロパガンダ』。イーストランシング:ミシガン州立大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-87013-710-5。 エドワーズ、ジョン・カーヴァー(1991)。『ベルリン・コーリング:第三帝国に奉仕したアメリカの放送局』。ニューヨーク:プレガー。ISBN 978-0-275-93905-2。 フッセル、ステファン(2020)。『グーテンベルクと印刷の影響』。ラウトレッジ。ISBN 978-1-351-93187-8。 ヒンダリー、ロデリック。「宗教テロリズムにおけるプロパガンダの解剖」。『ヒューマニスト』(2003年3月-4月号):16-19頁。 ハウ、エリック(1982)。『ブラック・ゲーム:第二次世界大戦中のドイツに対する英国の破壊工作作戦』。ロンドン:フューチュラ。 ハクスリー、オルダス(1989)[1958]。『すばらしい新世界再訪』。ニューヨーク:ハーパー。ISBN 978-0-06-080984-3。 ジョウェット、ガース・S.; オドネル、ビクトリア(2006)。『プロパガンダと説得』(第4版)。カリフォルニア州サウザンドオークス:セージ出版。ISBN 978-1-4129-0897-9。 ル・ボン、ギュスターヴ(1977)[1895]。『群衆:大衆心理の研究』。ペンギンブックス。ISBN 978-0-14-004531-4。 ラインバーガー、ポール M. A. (1972) [1948]。『心理戦』。ワシントン D.C.:歩兵ジャーナルプレス。ISBN 978-0-405-04755-8。 ネルソン、リチャード・アラン (1996)。米国におけるプロパガンダの年表と用語集。コネチカット州ウェストポート:グリーンウッド・プレス。ISBN 978-0-313-29261-3。 シャイラー、ウィリアム・L. (2002) [1941]。ベルリン日記:外国特派員の日誌、1934年~1941年。ニューヨーク:アルバート・A・クノップ。ISBN 978-5-9524-0081-8。 ヤング、エマ(2001年10月10日)。「アフガニスタンで繰り広げられた心理戦」。ニューサイエンティスト。2002年2月13日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2010年8月5日取得。 |