陶片追放/オストラシズム

Ostracism

Ostraca

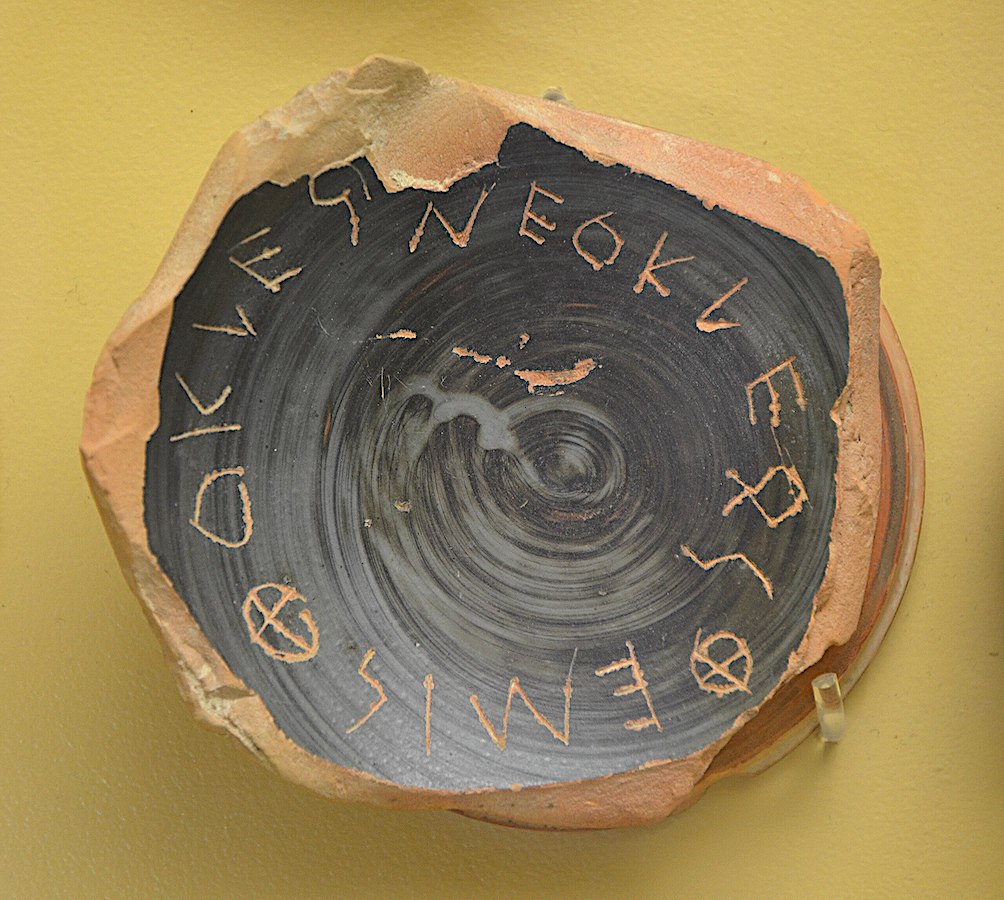

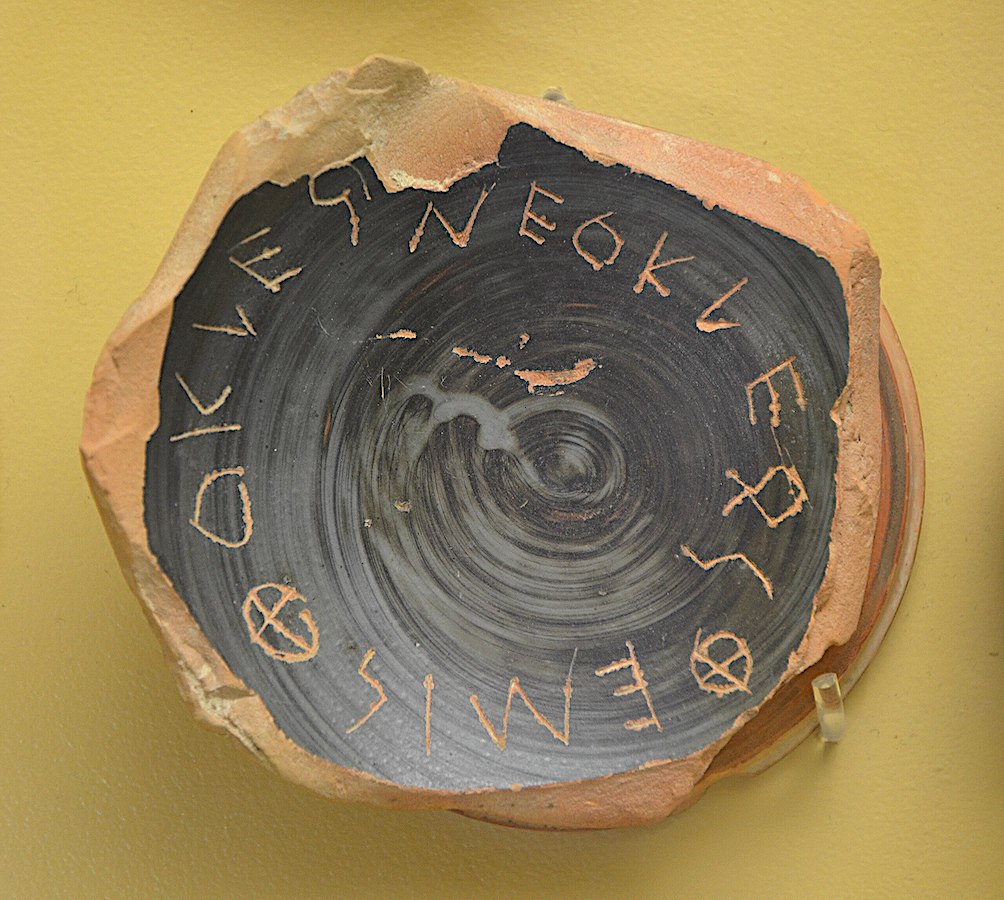

from 482 BC voting in favor of ostracizing Themistocles

☆[陶片]追放(ギリシャ語: ὀστρακισμός, ostrakismos)とは、アテネ市民が国家から10年間追放される民主的手続きであった。市民に対する民衆の怒りが明確に表れた事例もあるが、追放 はしばしば予防的に用いられ、国家への脅威や潜在的な専制君主と見なされた人物を無力化する手段となった。オストラシズムという言葉は、現在も様々な形の 排斥を指す言葉として使われている。

| Ostracism (Greek: ὀστρακισμός, ostrakismos) was an Athenian democratic procedure in which any citizen could be expelled from the city-state of Athens for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed popular anger at the citizen, ostracism was often used preemptively as a way of neutralizing someone thought to be a threat to the state or a potential tyrant. The word ostracism continues to be used for various forms of shunning. | [陶片]追放(ギリシャ語:

ὀστρακισμός,

ostrakismos)とは、アテネ市民が国家から10年間追放される民主的手続きであった。市民に対する民衆の怒りが明確に表れた事例もあるが、追放

はしばしば予防的に用いられ、国家への脅威や潜在的な専制君主と見なされた人物を無力化する手段となった。オストラシズムという言葉は、現在も様々な形の

排斥を指す言葉として使われている。 |

| Procedure The term ostracism is derived from the pottery shards that were used as voting tokens, called ostraka (singular: ostrakon; ὄστρακον) in Greek.[1] Broken pottery, abundant and virtually free, served as a kind of scrap paper (in contrast to papyrus, which was imported from Egypt as a high-quality writing surface, and too costly to be disposable).[2][3] Each year the Athenians were asked in the assembly whether they wished to hold an ostracism. The question was put in the sixth of the ten months used for state business under the democracy (January or February in the modern Gregorian calendar).[4] The process of ostracism could be divided into five elements according to Philochorus: 1) It was a two-stage process, 2) it was open to all Athens citizens,[4] 3) it was overseen by outside officials, 4) must meet a specific quorum, 5) regulated penalties.[5] The majority of citizen must come to a unified agreement to start the procedures of Ostracism.[5] If they voted "yes", then an ostracism would be held two months later. In a section of the agora set off and suitably barriered[6] that was called perischoinisma (περισχοίνισμα),[7][8][9] citizens gave the name of those they wished to be ostracized to a scribe, as many of them were illiterate, and they then scratched the name on pottery shards. The shards were piled up facing down, so the votes would remain anonymous.[1] Ostracism served as a political tool to eliminate rivals. It also helped to reflect the Athenians' belief in the importance of civic engagement and the power of collective decision making.[10] Nine Archontes and the council of the five hundred supervised the process[1] while the Archontes counted the ostraka submitted and sorted the names into separate piles.[11] The person whose pile contained the most ostraka would be banished, provided that a quorum was met. According to Plutarch, the ostracism was considered valid if the total number of votes cast was at least 6,000;[12] according to a fragment of Philochorus, at least 6,000 votes had to be cast against the person who was to be banished.[13][14] Plutarch's evidence for a quorum of 6,000 agrees with the number required for grants of citizenship in the following century and is generally preferred.[15][16][17][18] The person newly ostracized had ten days to leave the city.[11] If he attempted to return, the penalty was death. The property of the man banished was not confiscated and there was no loss of status. After ten years, he was allowed to return without stigma.[5][4] It was possible for the assembly to recall an ostracized person ahead of time; before the Persian invasion of 479 BC, an amnesty was declared under which at least two ostracised leaders—Pericles' father, Xanthippus, and Aristides 'the Just'—are known to have returned. Similarly, Cimon, ostracised in 461 BC, was recalled during an emergency.[19] |

手順 オストラシズムという用語は、投票のトークンとして使われた陶器の破片に由来する。ギリシャ語ではオストラカ(単数形:オストラコン;ὄστρακον) と呼ばれるものだ。[1] 豊富で事実上無料の陶器の破片は、一種のメモ用紙として使われた(高品質な筆記用具としてエジプトから輸入され、使い捨てには高価すぎたパピルスとは対照 的である)。[2][3] 毎年、アテナイ市民は集会においてオストラシズムの実施の是非を問われた。この質問は、民主制下で国家業務に用いられた10ヶ月のうち第6月(現代のグレ ゴリオ暦では1月または2月に相当)に提示された。[4] フィロコロスによれば、オストラシズムの手続きは以下の5要素に分けられる:1) これは二段階のプロセスであった。2) 全アテネ市民が参加可能[4]、3) 外部官吏による監督、4) 特定の定足数達成必須、5) 罰則規定[5]。 市民の過半数がオストラシズム手続き開始に合意する必要があった[5]。「賛成」が可決された場合、二か月後にオストラシズムが実施された。アゴラの一角 に設けられた、適切に区切られた[6]「ペリショイニスマ(περισχοίνισμα)」[7][8][9]と呼ばれる場所で、市民は追放対象者の名前 を書記官に伝えた。多くの市民は読み書きができなかったためである。その後、彼らは陶器の破片にその名前を刻んだ。陶片は裏向きに積み上げられ、投票の匿 名性が保たれた[1]。追放は政敵を消去法による排除の手段として機能した。同時に、市民参加の重要性と集団意思決定の力をアテナイ人が信じた証でもあっ た[10]。九人のアルコンと五百人評議会が手続きを監督し[1]、アルコンが提出されたオストラカを数え、名前を別々の山に分類した。[11] 定足数が満たされた場合、最も多くのオストラカが集まった人格が追放される。プルタルコスによれば、有効な追放投票には少なくとも6,000票が必要だっ た[12]。フィロコロースの断片によれば、追放対象者に対して少なくとも6,000票の反対票が投じられなければならなかった。[13][14] プルータルコスが提示する6,000票の定足数要件は、後世の市民権付与に必要な票数と一致し、一般的に支持されている。[15][16][17] [18] 新たに追放された人格は、10日以内に都市を去らねばならなかった[11]。もし戻ろうとすれば、その罰は死であった。追放された人格の財産は没収され ず、身分も失われなかった。10年後、彼は汚名なしに帰還を許された[5]。[4] 追放された人格を早期に呼び戻すことも可能だった。紀元前479年のペルシア侵攻前には恩赦が宣言され、少なくとも二人の追放指導者——ペリクレスの父ク サンティッポスと「正義のアリストイデス」——が帰還したことが確認されている。同様に、紀元前461年に追放されたキモンも、緊急時に呼び戻された。 [19] |

| History Ostracism was not in use throughout the entire period of Athenian democracy (circa 506–322 BC), but only occurred in the fifth century BC. The standard account, found in Aristotle's Constitution of the Athenians 22.3,[20] attributes the establishment to Cleisthenes, a pivotal reformer in the creation of the democracy. In that case, ostracism would have been in place from around 506 BC. The first victim of the practice was not expelled until 487 BC—nearly 20 years later. Over the course of the next 60 years some 12 or more individuals followed him. The list may not be complete.[21] The list of known ostracisms is as follows:  Ostraca from 482 BC voting in favor of ostracizing Themistocles 487 Hipparchos son of Charmos, a relative of the tyrant Peisistratos 486 Megacles son of Hippocrates; nephew of Cleisthenes (possibly ostracised twice)[22] 485 Kallixenos nephew of Cleisthenes (not known for certain)[citation needed] 484 Xanthippus son of Ariphron, Pericles' father 482 Aristides son of Lysimachus 471 Themistocles son of Neocles (last possible year) 461 Cimon son of Miltiades 460 Alcibiades, father of Cleinias (possibly ostracised twice)[22] 457 Menon son of Meneclides (less certain) 442 Thucydides son of Melesias 440s Callias son of Didymos (less certain) 440s Damon son of Damonides (less certain) 416 Hyperbolus son of Antiphanes (±1 year) Around 12,000 political ostraka have been excavated in the Athenian agora and in the Kerameikos.[23] The second victim, Cleisthenes' nephew Megacles, is named by 4647 of these, but for a second undated ostracism not listed above. The known ostracisms seem to fall into three distinct phases: the 480s BC, mid-century 461–443 BC and finally the years 417–415: this roughly correlates with the clustering of known expulsions, although Themistocles before 471 may count as an exception. This may suggest that ostracism fell in and out of fashion.[24] The last known ostracism was that of Hyperbolus in circa 417 BC. There is no sign of its use after the Peloponnesian War, when democracy was restored after the oligarchic coup of the Thirty had collapsed in 403 BC. However, while ostracism was not an active feature of the fourth-century version of democracy, it remained; the question was put to the assembly each year, but they did not wish to hold one. |

歴史 追放刑はアテナイ民主政の全期間(紀元前506年~322年頃)を通じて行われたわけではなく、紀元前5世紀にのみ実施された。アリストテレスの『アテナ イの憲法』22.3[20]に見られる標準的な説によれば、この制度の創設者は民主政確立の要となった改革者クレイトスである。この説によれば、追放制度 は紀元前506年頃から存在していたことになる。しかし実際に最初の犠牲者が追放されたのは紀元前487年、つまり約20年後であった。その後60年間 で、彼に続いて12人以上の個人が追放された。このリストは完全ではない可能性がある[21]。既知の追放事例は以下の通りである:  紀元前482年 テミストクレス追放賛成票のオストラコン 紀元前487年 カルモスの子ヒッパルコス(専制君主ペイシストラトスの親族) 紀元前486年 ヒッポクラテスの子メガクレス(クレイステネスの甥。おそらく二度追放された)[22] 紀元前485年 カリクセノス(クレイステネスの甥。確実ではない)[出典必要] 紀元前484年 アリフロンの子クサンティッポス(ペリクレスの父) 紀元前482年 リシマコスの子アリストイデス 紀元前471年 ネオクレスの子テミストクレス(最後の可能性のある年) 紀元前461年 ミルティアデスの子キモン 紀元前460年 クレニアスの父アルキビアデス(おそらく二度追放された)[22] 紀元前457年 メネクレイデスの子メノン (確証が薄い) 442年 テュキディデス(メレシアスの子) 440年代 カリアス(ディディモスの子)(確証が薄い) 440年代 ダモン(ダモニデスの子)(確証が薄い) 416年 ヒュペルボロス(アンティファネスの子)(±1年) アテナイのアゴラとケラメイコスでは、約12,000点の政治的オストラコンが発掘されている。[23] 2人目の犠牲者であるクレイトスネスの甥メガクレスは、これら4647件のうちで名指しされているが、上記に列挙されていない日付不明の2度目の追放投票 によるものである。既知の追放投票は、紀元前480年代、紀元前461~443年の半ば、そして最後に紀元前417~415年の3つの明確な段階に分類さ れるようだ。これは既知の追放事例の集中と概ね一致するが、紀元前471年以前のテミストクレスは例外と見なせる。これは追放令が流行と廃れを繰り返した ことを示唆しているかもしれない。[24] 最後に確認される追放令は紀元前417年頃のヒュペルボロスに対するものである。ペロポネソス戦争後、紀元前403年に三十人政権が崩壊して民主政が復活 すると、オストロカイシモスの使用は確認されない。しかし、紀元前4世紀の民主政においてオストロカイシモスが活動的な要素ではなかったとはいえ、制度自 体は存続していた。毎年、国民議会に実施の是非が問われたが、実施を望む声は上がらなかったのである。 |

| Distinction from other Athenian democratic processes Ostracism was crucially different from Athenian law at the time; there was no charge and no defense could be mounted by the person expelled. The two stages of the procedure ran in the reverse order from that used under almost any trial system—it is as if a jury were first asked "Do you want to find someone guilty?", and subsequently asked "Whom do you wish to accuse?". The judicial framework is perhaps the institution's most peculiar feature: it can take place at most once a year, and only for one person. It resembles the Greek pharmakos or scapegoat—though in contrast, pharmakos generally ejected a lowly member of the community.[25] A further distinction between these two modes (and not obvious from a modern perspective) is that ostracism was an automatic procedure that required no initiative from any individual, with the vote simply occurring on the wish of the electorate—a diffuse exercise of power.[26] By contrast, an Athenian trial needed the initiative of a particular citizen-prosecutor. While prosecution often led to a counterattack (or was a counterattack itself), no such response was possible in the case of ostracism as responsibility lay with the polity as a whole. In contrast to a trial, ostracism generally reduced political tension rather than increased it.[27] Although ten years of exile may have been challenging for Athenians, it was a lenient punishment compared to the sentences that courts could impose. When dealing with politicians held to be acting against the interests of the people, Athenian juries could inflict severe penalties such as death,[28] unpayably large fines, confiscation of property, permanent exile, or loss of citizens' rights through atimia.[4] Further, the elite Athenians who suffered ostracism were rich or noble men who had connections or xenoi in the wider Greek world and who, unlike genuine exiles, were able to access their income in Attica from abroad. In Plutarch, following the anti-democratic thought common in elite sources, people might be recalled early, thus being an example of the inconsistency of majoritarianism characteristic of Athenian democracy. However, ten years of exile usually resolved whatever had prompted the expulsion. Ostracism was a pragmatic measure; the concept of serving out the full sentence did not apply as it was a preventive measure, not a punitive one.[4]  Bust of Themistocles, who was exiled via ostracism and fled to Argos around 471 or 472 BC, despite an impactful military career. An example of the practicalities of ostracism comes from the cache of 190 ostraka discovered dumped in a well next to the acropolis.[29] From the handwriting, they appear to have been written by fourteen individuals and bear the name of Themistocles, ostracised before 471 BC, and were evidently meant for distribution to voters.[4] This was not necessarily evidence of electoral fraud (being no worse than modern voting instruction cards), but their being dumped in the well may suggest that their creators wished to hide them. If so, these ostraka provide an example of organized groups attempting to influence the outcome of ostracisms. The two-month gap between the first and second phases would have allowed for such a campaign.[citation needed] There is another interpretation, however, according to which these ostraka were prepared beforehand by enterprising businessmen who offered them for sale to citizens who could not easily inscribe the desired names for themselves or who simply wished to save time.[30] The two-month gap is a key feature in the institution, much as in elections under modern liberal democracies. It prevented the candidate for expulsion being chosen out of immediate anger, although an Athenian general such as Cimon would have not wanted to lose a battle the week before such a second vote.[19] It opened a period for discussion (or perhaps agitation), whether informally in daily talk or public speeches before the Athenian assembly or Athenian courts.[note 1] In this process a consensus, or rival consensuses, might emerge. |

他のアテナイ民主主義手続きとの相違点 オストラシズムは当時のアテナイ法と根本的に異なり、追放される人格が弁護する機会もなかった。手続きの二段階は、ほぼ全ての裁判制度とは逆の順序で進行 した。あたかも陪審員にまず「誰かを有罪と認めるか?」と問われ、その後「誰を告発したいか?」と問われるようなものだ。司法的枠組みは、おそらくこの制 度の最も特異な特徴である。実施は年に一度が上限で、対象は一人だけだ。ギリシャのファルマコス(身代わり)やスケープゴートに似ているが、対照的にファ ルマコスは通常、共同体の低位の成員を追放した。[25] これら二つの制度のさらなる相違点(現代の視点からは明らかではない)は、追放が個人の主導を必要としない自動的な手続きであり、投票は単に有権者の意思 に基づいて行われる——つまり拡散的な権力行使であったことだ。[26] これに対し、アテナイの裁判には特定の市民である告発者の主導が必要だった。告発はしばしば反撃を招く(あるいはそれ自体が反撃である)が、追放では責任 が共同体全体にあるため、そのような反撃は不可能だった。裁判とは対照的に、追放は一般的に政治的緊張を高めるのではなく緩和した。[27] 10年間の追放はアテナイ人にとって困難であったかもしれないが、裁判所が科し得る刑罰に比べれば寛大な処罰であった。民衆の利益に反する行動をとったと 見なされた政治家に対して、アテナイの陪審員は死刑[28]、支払不能な巨額の罰金、財産没収、永久追放、あるいはアティミアによる市民権剥奪といった厳 しい刑罰を科すことができた。[4] さらに、苦悩の追放処分を受けたアテネのエリート層は富裕層や貴族であり、広範なギリシャ世界にコネクションや外国人(クセノイ)を有していた。本物の亡 命者とは異なり、彼らは国外からアッティカ地方の収入にアクセスできたのである。プルタルコスによれば、エリート層の資料に共通する反民主主義的思考に従 えば、追放者は早期に復権する可能性があり、これはアテネ民主主義の特徴である多数決主義の矛盾を示す例となった。しかし、通常10年の亡命期間で追放の 理由は解消された。オストロシズムは実用的な措置であり、刑期を全うする概念は適用されなかった。これは懲罰ではなく予防策だったからだ。[4]  オストラシズムにより追放され、紀元前471年か472年頃にアルゴスへ逃れたテミストクレスの胸像。彼は軍事的功績は大きかったが、それでも追放された。 オスティカイズムの実践例として、アクロポリス近くの井戸に捨てられていた190枚のオストラカが発見された事例がある[29]。筆跡から14名の個人に よるものと見られ、紀元前471年以前に追放されたテミストクレスの名が記されており、明らかに有権者への配布を目的としていた。[4] これは必ずしも選挙不正の証拠ではない(現代の投票指示カードと同程度である)。しかし井戸に捨てられていた事実は、作成者が隠蔽を図った可能性を示唆す る。もしそうなら、これらのオストラコンは組織的な集団が追放投票の結果に影響を与えようとした事例となる。第一段階と第二段階の間の二ヶ月の間隔は、そ のような運動を可能にしたであろう。[出典必要] しかし別の解釈もある。それによれば、これらのオストラコンは事前に準備されたもので、自ら希望する名前を書き込むのが困難な市民や、単に時間を節約したい市民に向けて、事業家たちが販売していたというのだ。[30] この二ヶ月の間隔は、現代の自由民主主義国家における選挙と同様に、この制度の重要な特徴である。これにより、追放候補者が衝動的な怒りに駆られて選ばれ ることを防いだ。もっとも、キモンといったアテナイの将軍は、再投票の1週間前に戦いに敗れることを望まなかっただろう[19]。この期間が議論(あるい は扇動)の場となった。日常会話での非公式な議論であれ、アテナイ議会や法廷での公の演説であれ[注1]。この過程で、合意、あるいは対立する合意が生ま れる可能性があった。 |

| Purpose Because ostracism was carried out by thousands of people over many decades of an evolving political situation and culture, it did not serve one monolithic purpose. Observations can be made about the outcomes, as well as the initial purpose for which it was created. The first instance of people ostracized in the decade after the defeat of the first Persian invasion at Marathon in 490 BC were related or connected to the tyrant Peisistratos, who had controlled Athens for 36 years up to 527 BC. After his son Hippias was deposed with Spartan help in 510 BC, the family sought refuge with the Persians. Nearly twenty years later Hippias landed with an invasion force at Marathon. Tyranny and Persian aggression were paired threats facing the new democratic regime at Athens, and ostracism was used against both.  Example of a Greek Ostracon, suggesting the Ostracization of Themistocles, from the Stoà of Attalus Museum (482 BC). Tyranny and democracy had arisen at Athens out of clashes between regional and factional groups organized around politicians, including Cleisthenes. As a reaction, in many of its features the democracy strove to reduce the role of factions as the focus of citizen loyalties. Ostracism may have been intended to work in the same to similar ends: by temporarily decapitating a faction, it could help defuse confrontations that threatened the order of the State.[31] In later decades when the threat of tyranny was remote, ostracism seems to have been used to decide between radically opposed policies. For instance, in 443 BC Thucydides, son of Melesias (not to be confused with the historian of the same name) was ostracized. He led an aristocratic opposition to Athenian imperialism and in particular to Pericles' building program on the acropolis, which was funded by taxes created for the wars against the Achaemenid Empire. By expelling Thucydides the Athenian people sent a clear message about the direction of Athenian policy.[32] Similar but controversial claims have been made about the ostracism of Cimon in 461 BC.[4] The motives of individual voting citizens cannot be known. Many of the surviving ostraka name people otherwise unattested. They may well be just someone the submitter disliked, and voted for in a moment of private spite. Some ostraka bear the word "Limos" (hunger) instead of a human name.[33] As such, it may be seen as a secular, civic variant of Athenian curse tablets, studied in scholarly literature under the Latin name defixiones, where small dolls were wrapped in lead sheets written with curses and then buried, sometimes stuck through with nails for good measure.[citation needed] In one anecdote about Aristides, known as "the Just", who was ostracised in 482, an illiterate citizen, not recognising him, asked him to write the name Aristides on his ostrakon. When Aristides asked why, the man replied it was because he was sick of hearing him being called "the Just".[34] Perhaps merely the sense that someone had become too arrogant or prominent was enough to get someone's name onto an ostrakon. Ostracism rituals could have also been an attempt to dissuade people from covertly committing murder or assassination of intolerable or emerging individuals of power so as to create an open arena or outlet for those harbouring primal frustrations and urges or political motivations. The solution for murder, in Gregory H. Padowitz's theory, would then be "ostracism" which would ultimately be beneficial for all parties—the ostracised individual would live and get a second chance and society would be spared feuds, civil war, political tensions and/or murder. |

目的 追放は数千人の民衆によって、数十年にわたる政治状況と文化の変遷の中で実施されたため、単一の目的を果たしたわけではない。その結果について考察できるのと同様に、当初の目的についても言及できる。 紀元前490年、マラトンで最初のペルシア侵攻が撃退された後の10年間に追放された最初の事例は、紀元前527年まで36年間アテネを支配した専制君主 ペイシストラトスに関連する者たちであった。彼の息子ヒッピアスが紀元前510年にスパルタの支援で追放された後、一族はペルシアに亡命を求めた。それか ら約20年後、ヒッピアスが軍勢を率いてマラトンに上陸した。専制政治とペルシアの侵略は、アテネの新民主政が直面した二重の脅威であり、追放令は両者に 対抗するために用いられた。  アッタルス博物館所蔵のギリシャのオストラコン(紀元前482年)。テミストクレスの追放を示唆する例。 アテネにおける専制政治と民主主義は、クレシテネスら政治家を中心に組織された地域・派閥集団間の衝突から生まれた。これに対し民主主義は、多くの特徴に おいて、市民の忠誠心の焦点となる派閥の役割を縮小しようと努めた。オストラシズムも同様の目的で機能するよう意図されていた可能性がある。すなわち、一 時的に派閥の指導部を排除することで、国家秩序を脅かす対立を緩和するのに役立つというのだ。[31] その後数十年、専制政治の脅威が遠のくと、追放制度は根本的に対立する政策の選択手段として用いられたようだ。例えば紀元前443年、メレシアスの子トゥ キディデス(同名の歴史家とは別人物)が追放された。彼は貴族層の代表として、アテナイの帝国主義、特にアケメネス朝ペルシアとの戦争のために創設された 税で賄われたアクロポリスにおけるペリクレスの建設計画に反対した。トゥキディデスの追放により、アテナイ市民は国家政策の方向性について明確な意思表示 を行ったのである。[32] 紀元前461年のキモンの追放についても、同様の主張がなされているが、これは議論の余地がある。[4] 投票した個々の市民の動機は知る由もない。現存するオストラコンの多くは、他に記録のない人物の名を記している。提出者が単に嫌っていた人物であり、私怨 の瞬間に投票しただけかもしれない。人間の名の代わりに「リモス」(飢饉)という文字が記されたオストラコンもある。[33] このため、オストラコンはアテネの呪い板(ラテン語名デフィキシオーネス)の世俗的・市民的変種と見なせる。学術文献で研究される呪い板では、呪いの文が 書かれた鉛板に小さな人形を包み、時には釘で打ち付けて埋葬した。[出典必要] 「正義の人」として知られるアリスティデスに関する逸話がある。彼は紀元前482年に追放されたが、ある文盲の市民が彼を認識できず、オストラコンに「ア リスティデス」と書くよう頼んだ。アリスティデスが理由を尋ねると、男は「正義の人」と呼ばれるのにうんざりしているからだと答えたという。[34] おそらく、単に誰かが傲慢になりすぎたり目立ちすぎたりしたという感覚だけで、その名前がオストラコンに書かれるのに十分だったのだろう。追放の儀礼は、 耐え難い人物や台頭する権力者に対する暗殺や殺害を人々が密かに行うのを思いとどまらせ、原始的な欲求不満や衝動、あるいは政治的動機を抱える者たちのた めの公の舞台や発散の場を作る試みでもあったのかもしれない。グレゴリー・H・パドウィッツの理論によれば、殺害に対する解決策は「追放」であり、これは 最終的に全ての関係者に利益をもたらす。追放された個人は生き延びて再起の機会を得られ、社会は抗争や内戦、政治的緊張、あるいは殺害から免れるのだ。 |

| Fall into disuse The last ostracism, that of Hyperbolos in or near 417 BC, is narrated by Plutarch in three separate lives: Hyperbolos is pictured urging the people to expel one of his rivals, but they, Nicias and Alcibiades, laying aside their hostility for a moment, use their influence to have him ostracised instead. According to Plutarch, the people then become disgusted with ostracism and abandoned the procedure forever. In part ostracism lapsed as a procedure at the end of the fifth century because it was replaced by the graphe paranomon, a regular court action under which a much larger number of politicians might be targeted, instead of just one a year as with ostracism, and with greater severity. It may already seemed like an anachronism as factional alliances organised around important men became less significant and power was more specifically located in the interaction of the individual speaker with the power of the assembly and the courts. The threat to the democratic system in the late fifth century came not from tyranny but from oligarchic coups, threats of which became prominent after two brief seizures of power, in 411 BC by "the Four Hundred" and in 404 BC by "the Thirty", which were not dependent on single powerful individuals. Ostracism was not an effective defence against the oligarchic threat and it was not so used. |

廃止 最後の追放令は紀元前417年頃のヒュペルボロスに対するもので、プルタルコスが三つの伝記で記している。ヒュペルボロスが民衆に敵対者を追放するよう促 す場面が描かれているが、ニキアスとアルキビアデスはその敵意を一時的に捨て、自らの影響力を使って逆に彼を追放したのである。プルタルコスによれば、民 衆はこの後、追放刑に嫌気がさし、この手続きを永久に放棄したという。 第五世紀末に追放刑が手続きとして廃れた一因は、グラフェ・パラノモン(法廷告発)に取って代わられたことにある。これは通常の法廷手続きであり、追放刑のように年に一人だけではなく、より多くの政治家を標的にでき、より厳しい処罰が可能だった。 重要な人物を中心に組織された派閥同盟の重要性が低下し、権力がより具体的に、個々の発言者と議会・裁判所の力との相互作用の中に位置づけられるように なったため、オスロコスはすでに時代錯誤のように思われたのかもしれない。紀元前5世紀末の民主制に対する脅威は専制ではなく、寡頭制クーデターから生じ た。その脅威は紀元前411年の「四百人」による短期間の権力掌握と、紀元前404年の「三十人」による同様のクーデターを経て顕在化した。これらは単独 の強大な個人に依存しない形態であった。追放令は寡頭制の脅威に対する有効な防御手段ではなく、そのように用いられることもなかった。 |

| Analogues Other cities are known to have set up forms of ostracism on the Athenian model, namely Megara, Miletos, Argos and Syracuse, Sicily. In the last of these it was referred to as petalismos, because the names were written on olive leaves. Little is known about these institutions. Furthermore, pottery shards identified as ostraka have been found in Chersonesos Taurica, leading historians to the conclusion that a similar institution existed there as well, in spite of the silence of the ancient records on that count.[35] A similar modern practice is the recall election, in which the electoral body removes its representation from an elected officer. Unlike under modern voting procedures, the Athenians did not have to adhere to a strict format for the inscribing of ostraka. Many extant ostraka show that it was possible to write expletives, short epigrams or cryptic injunctions beside the name of the candidate without invalidating the vote.[36] For example: Kallixenes, son of Aristonimos, "the traitor" Archen, "lover of foreigners" Agasias, "the donkey" Megacles, "the adulterer" |

類似例 他の都市もアテネのモデルに基づいて追放制度を設けたことが知られている。具体的にはメガラ、ミレトス、アルゴス、そしてシチリアのシラクーサである。最 後の例では、名前がオリーブの葉に書かれたことから「ペタリズモス」と呼ばれた。これらの制度についてはほとんど知られていない。さらに、タウリカ岬(ケ ルソネス)ではオストラカと特定された陶片が発見されており、古代の記録にはその点について言及がないにもかかわらず、歴史家たちは同様の制度がそこにも 存在していたと結論づけている。[35] 現代における類似の慣行として、リコール選挙がある。これは選挙民が選出された公職者からその代表権を剥奪する制度である。 現代の投票手続きとは異なり、アテナイ市民はオストラカへの記名形式を厳格に遵守する必要はなかった。現存する多くのオストラカが示すように、候補者の名前の横に罵倒語、短いエピグラム、あるいは暗号めいた指示を記しても、投票は無効とならなかったのだ[36]。例えば: カリクセネス、アリストニモスの子、「裏切り者」 アルケン、「外国人の愛好者」 アガシアス、「ろば」 メガクレス、「姦通者」 |

| Modern usage Ostracism is evident in several animal species,[37]: 10 as well as in modern human interactions. The social psychologist Kipling Williams defines ostracism as "any act or acts of ignoring and excluding of an individual or groups by an individual or a group" without necessarily involving "acts of verbal or physical abuse".[37] Williams suggests that the most common form of ostracism is silent treatment,[37]: 2 wherein refusing to communicate with a person effectively ignores and excludes them.[38] Computer networks Ostracism in the context of computer networks (such as the Internet) is termed "cyberostracism". In email communication, in particular, it is relatively easy to engage in silent treatment, in the form of "unanswered emails"[39] or "ignored emails".[40] Being ostracised on social media is seen to be threatening to the fundamental human needs of belonging, self-esteem, control and meaningful existence.[41] Cyber-rejection (receiving "dislikes") caused more threat to the need of belonging and self-esteem, and lead to social withdrawal.[42] Cyber-ostracism (being ignored or receiving fewer "likes")[43] conversely lead to more prosocial behavior.[42] Ostracism is thought to be associated with social media disorder.[44] Reactions Williams and his colleagues have charted responses to ostracism in some five thousand cases, and found two distinctive patterns of response. The first is increased group-conformity, in a quest for re-admittance; the second is to become more provocative and hostile to the group, seeking attention rather than acceptance.[45][better source needed] Age Older adults report experiencing ostracism less frequently, with a particular dip being around the age of retirement. Regardless of age, ostracism is strongly associated with negative emotions, reduced life satisfaction and dysfunctional social behaviour.[46][47] Whistleblowing Research suggests that ostracism is a common retaliatory strategy used by organizations in response to whistleblowing. Kipling Williams, in a survey on US whistleblowers, found that all respondents reported post-whistleblowing ostracism.[37]: 194–195 Alexander Brown similarly found that post-whistleblowing ostracism is a common response, and indeed describes ostracism as a form of "covert" reprisal, as it is normally so difficult to identify and investigate.[48] Ghahr and Âshti Ghahr and Âshti is a culture-specific Iranian form of personal shunning, most frequently of another family member in Iran.[49] While modern Western concepts of ostracism are based upon enforcing conformity within a societally-recognized group, Ghahr is a private, family-orientated affair of conflict or display of anger[50] that is never disclosed to the public at large, as to do so would be a breach of Iranian social etiquette.[51] Ghahr is avoidance of a lower-ranking family member who has committed a perceived insult. It is one of several ritualised social customs of Iranian culture.[49] Gozasht means 'tolerance, understanding and a desire or willingness to forgive'[52] and is an essential component of Ghahr and Âshti[52] for the psychological needs of closure and cognition. |

現代的な用法 排斥はいくつかの動物種[37]: 10 において明らかで、現代の人間関係にも見られる。社会心理学者キプリング・ウィリアムズは排斥を「個人または集 団による、個人または集団を無視し排除する行為」と定義し、必ずしも「言葉や身体による虐待行為」を伴うものではないとしている。[37] ウィリアムズによれば、最も一般的な排斥の形態は「沈黙の処置」である[37]: 2 。これは人格との意思疎通を拒否することで、事実上無視・排除する行為を指す[38]。 コンピュータネットワーク コンピュータネットワーク(インターネットなど)における排斥は「サイバー排斥」と呼ばれる。特に電子メール通信では、「返信されないメール」[39]や 「無視されるメール」[40]という形で、沈黙の処置を比較的容易に行うことができる。ソーシャルメディア上で排斥されることは、帰属意識、自尊心、支配 感、有意義な存在感といった人間の基本的欲求に対する脅威と見なされる。[41] サイバー拒絶(「嫌い」の受け取り)は帰属欲求と自尊心にさらなる脅威を与え、社会的引きこもりにつながる。[42] 逆に、サイバー排斥(無視される、あるいは「いいね」が少なくなること)[43] はより多くの社会貢献行動を引き起こす。[42] 排斥(オストラシズム)はソーシャルメディア依存症と関連していると考えられている。[44] 反応 ウィリアムズらは約5000件の排除事例を分析し、二つの反応パターンを確認した。一つは集団への再帰属を求めて集団順応性を高める反応、もう一つは集団への注目を求め、受け入れではなく挑発的・敵対的になる反応である。[45] [より良い情報源が必要] 年齢 高齢者は、特に定年頃を境に、排斥を経験する頻度が減少すると報告している。年齢に関係なく、排斥は、ネガティブな感情、生活満足度の低下、機能不全の社会的行動と強く関連している。[46][47] 内部告発 研究によれば、排斥は、内部告発に対する組織による一般的な報復戦略である。キプリング・ウィリアムズは、米国の内部告発者を対象とした調査で、回答者全 員が内部告発後の排斥を報告していることを発見した。[37]: 194–195 アレクサンダー・ブラウンも同様に、内部告発後の排斥は一般的な反応であり、通常、その特定と調査が非常に難しいため、排斥は「隠れた」報復の一形態であ ると述べている。[48] ガーとアシュティ ガーとアシュティは、イラン特有の文化的な個人的な排斥の形態であり、イランでは最も頻繁に他の家族に対して行われる。[49] 現代の西洋における排斥の概念は、社会的に認められた集団内での順応の強制に基づくものであるが、ガーは、イランの社会的礼儀に反することとなるため、決 して一般に公開されることのない、私的な、家族を中心とした紛争や怒りの表現である[50]。[51] ガーは、侮辱行為を犯したとみなされた下位の家族成員を避ける行為である。これはイラン文化における数ある儀式化された社会慣習の一つだ。[49] ゴザシュトは「寛容、理解、そして許す意思や意欲」を意味する[52]。これは心理的な終結と認知の必要性において、ガーとアシュティの不可欠な構成要素だ[52]。 |

| Cancel culture Contempt Isolation to facilitate abuse McCarthyism Petalism Relegatio Social control Witch-hunt |

キャンセル・カルチャー 軽蔑 虐待を助長する孤立 マッカーシズム ペタリズム 追放 社会的統制 ウイッチハント |

| Notes 1. Oration IV of Andocides purports itself to be speech urging the ostracism of Alcibiades in 415 BC, but it is probably not authentic. |

注記 1. アンドキデスの第四演説は、紀元前415年にアルキビアデスを追放するよう促す演説を装っているが、おそらく本物ではない。 |

| References | |

| Mitchell, John Malcolm (1911). "Ostracism" . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 360. |

ミッチェル、ジョン・マルコム (1911). 「オストラシズム」. チャールズ・ヒュー (編). ブリタニカ国際大百科事典. 第 20 巻 (第 11 版). ケンブリッジ大学出版局. p. 360. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ostracism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099