PBフォーチュン作戦

Operation PBFortune

Lieutenant General Walter Bedell Smith

☆ PBフォーチュン作戦、別名フォーチュン作戦は、1952年に民主的に選出されたグアテマラ大統領ハコボ・アルベンスを転覆させるための米国の秘密作戦で あった。この作戦はハリー・トルーマン米大統領によって承認され、中央情報局(CIA)によって計画された。ユナイテッド・フルーツ社は、アルベンスが始 めた土地改革が同社の経済的利益を脅かすとして、転覆を強く働きかけていた。米国はまた、アルベンス政権が共産主義者の影響下にあることを懸念していた。 クーデター計画は、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の支援と、アナスタシオ・ソモサ・ガルシア、ラファエル・トルヒーヨ、マルコス・ペレス・ヒメネスら、米国が 支援するニカラグア、ドミニカ共和国、ベネズエラの右派独裁者たちの協力のもとで進められた。彼らは民主的なグアテマラ革命を脅威と捉え、その弱体化を 図っていた。計画は、亡命中のグアテマラ軍将校カルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスに武器を供給し、ニカラグアから侵攻を指揮させることを含んでいた。 米国務省は計画の詳細が広く知れ渡っていることを発見した[1]。ディーン・アチソン国務長官は、非干渉政策を掲げていた米国のイメージを損なうと懸念 し、作戦を中止した。[2] オペレーションPBFortuneから2年後、別の秘密作戦であるオペレーションPBSuccessが実施された。この作戦でもカスティージョ・アルマスが重要な役割を果たした。PBSuccessはアルベンス政権を打倒し、グアテマラ革命に終止符を打った。[3]

☆(下記別項にOperation PBSuccess(オペレーションPBサクセス=CIAによる1954年のグアテマラのクーデター計画)を掲載中)

| Operation PBFortune,

also known as Operation Fortune, was a covert United States operation

to overthrow the democratically elected Guatemalan President Jacobo

Árbenz in 1952. The operation was authorized by U.S. President Harry

Truman and planned by the Central Intelligence Agency. The United Fruit

Company had lobbied intensively for the overthrow because land reform

initiated by Árbenz threatened its economic interests. The US also

feared that the government of Árbenz was being influenced by communists. The coup attempt was planned with the support of the United Fruit Company and of Anastasio Somoza García, Rafael Trujillo and Marcos Pérez Jiménez, the US-backed right-wing dictators of Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, and Venezuela respectively, who felt threatened by the democratic Guatemalan Revolution, and had sought to undermine it. The plan involved providing weapons to the exiled Guatemalan military officer Carlos Castillo Armas, who was to lead an invasion from Nicaragua. The US State Department discovered that details of the plan had become widely known.[1] US Secretary of State Dean Acheson became concerned that the coup attempt would damage the image of the US, which had committed to a policy of non-intervention, and so terminated the operation.[2] Operation PBFortune was followed two years later by Operation PBSuccess, another covert operation in which Castillo Armas played a prominent role. PBSuccess toppled the Árbenz government and ended the Guatemalan Revolution.[3] |

PBフォーチュン作戦、別名フォーチュン作戦は、1952年に民主的に

選出されたグアテマラ大統領ハコボ・アルベンスを転覆させるための米国の秘密作戦であった。この作戦はハリー・トルーマン米大統領によって承認され、中央

情報局(CIA)によって計画された。ユナイテッド・フルーツ社は、アルベンスが始めた土地改革が同社の経済的利益を脅かすとして、転覆を強く働きかけて

いた。米国はまた、アルベンス政権が共産主義者の影響下にあることを懸念していた。 クーデター計画は、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の支援と、アナスタシオ・ソモサ・ガルシア、ラファエル・トルヒーヨ、マルコス・ペレス・ヒメネスら、米国が 支援するニカラグア、ドミニカ共和国、ベネズエラの右派独裁者たちの協力のもとで進められた。彼らは民主的なグアテマラ革命を脅威と捉え、その弱体化を 図っていた。計画は、亡命中のグアテマラ軍将校カルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスに武器を供給し、ニカラグアから侵攻を指揮させることを含んでいた。 米国務省は計画の詳細が広く知れ渡っていることを発見した[1]。ディーン・アチソン国務長官は、非干渉政策を掲げていた米国のイメージを損なうと懸念 し、作戦を中止した。[2] オペレーションPBFortuneから2年後、別の秘密作戦であるオペレーションPBSuccessが実施された。この作戦でもカスティージョ・アルマス が重要な役割を果たした。PBSuccessはアルベンス政権を打倒し、グアテマラ革命に終止符を打った。[3] |

| Background Main article: Guatemalan Revolution From the late 19th century until 1944, a series of authoritarian rulers governed Guatemala. Between 1898 and 1920, Manuel Estrada Cabrera granted significant concessions to the United Fruit Company and dispossessed many indigenous peoples of their communal land.[4][5] Under Jorge Ubico, who ruled as a dictator between 1931 and 1944, this process was intensified with the institution of brutal labor regulations and the establishment of a police state.[6][7] In June 1944, a popular pro-democracy movement led by university students and labor organizations forced Ubico to resign.[8] Ubico handed over power to a military junta[9] that was toppled in a military coup led by Jacobo Árbenz in October 1944, an event known as the October Revolution.[10] The coup leaders called for open elections, which were won by Juan José Arévalo, a progressive professor of philosophy who had become the face of the popular movement. He implemented a moderate program of social reform, including a successful literacy campaign and largely free elections, although illiterate women were not given the vote, and communist parties were banned.[11] Following the end of Arévalo's highly popular presidency in 1951, Árbenz was elected president.[12][13] He continued the reforms of Arévalo and also began an ambitious land reform program known as Decree 900. Under it, the uncultivated portions of large land-holdings were expropriated in return for compensation[14] and redistributed to poverty-stricken agricultural laborers.[15] Some governments in Central America and the Caribbean were hostile to Árbenz and the Guatemalan Revolution. Anastasio Somoza García, Rafael Leonidas Trujillo and Marcos Pérez Jiménez, the US-backed right-wing dictators of Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic and Venezuela, respectively, felt threatened by Arévalo's reforms. Under Arévalo, Guatemala had become a haven for pro-democracy activists from those three countries. Somoza, Trujillo, and Jiménez had supported Guatemalan exiles working to undermine the Guatemalan government, in addition to suppressing democratic popular movements in their own countries.[16] The political climate of the Cold War led the US government to see the policies of Arévalo and Árbenz as communist. This conception had been strengthened by Arévalo's support for the Caribbean Legion, and by the 1950s the US government was considering overthrowing Árbenz.[17][18] The attitude of the United States was also influenced by the Monroe Doctrine, a philosophy of foreign policy articulated by James Monroe in 1823,[19][20] which justified the maintenance of US hegemony in the region.[21] The stated aim of the doctrine was to maintain order and stability and to make certain that access to resources and markets was not limited.[22] Historian Mark Gilderhus opines that the doctrine also contained racially condescending language, which likened Latin American countries to fighting children.[23] Before 1944, the US government had not needed to engage in military interventions in Guatemala to enforce this hegemony, given the presence of military rulers friendly to the US.[21] |

背景 詳細な記事: グアテマラ革命 19世紀後半から1944年まで、グアテマラは一連の独裁者によって統治された。1898年から1920年にかけて、マヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラは ユナイテッド・フルーツ社に多大な特権を与え、多くの先住民から共同所有地を奪った。[4][5] 1931年から1944年まで独裁者として統治したホルヘ・ウビコの下では、残酷な労働規制の導入と警察国家の確立により、この過程はさらに強化された。 [6][7] 1944年6月、大学生と労働団体が主導した民主化を求める民衆運動により、ウビコは辞任を余儀なくされた。[8] ウビコは軍事政権[9]に権力を移譲したが、1944年10月にハコボ・アルベンス率いる軍事クーデターで政権は打倒された。この事件は「十月革命」とし て知られる。[10] クーデター指導者たちは公選を実施し、民衆運動の象徴となった進歩的な哲学教授フアン・ホセ・アレバロが勝利した。彼は穏健な社会改革プログラムを実施し た。成功した識字運動や、ほぼ自由な選挙を含むが、文盲の女性には投票権が与えられず、共産党は禁止された。[11] 1951年にアレバロの大人気政権が終結すると、アルベンスが大統領に選出された。[12][13] 彼はアレバロの改革を継続し、さらに「法令900号」として知られる野心的な土地改革プログラムを開始した。これに基づき、大規模土地所有者の未耕作部分 は補償と引き換えに収用され[14]、貧困に苦しむ農業労働者に再分配された。[15] 中米とカリブ海地域のいくつかの政府は、アルベンスとグアテマラ革命に敵対的だった。ニカラグア、ドミニカ共和国、ベネズエラの米国支持の右派独裁者であ るアナスタシオ・ソモサ・ガルシア、ラファエル・レオニダス・トルヒーヨ、マルコス・ペレス・ヒメネスは、アレバロの改革に脅威を感じていた。アレバロ政 権下のグアテマラは、これら三カ国からの民主化活動家にとっての避難所となっていた。ソモサ、トルヒーヨ、ヒメネスは、自国における民主的な大衆運動を弾 圧する一方で、グアテマラ政府を弱体化させようとするグアテマラ亡命者を支援していた。[16] 冷戦下の政治情勢は、アメリカ政府にアレバロとアルベンスの政策を共産主義的と見なさせる要因となった。この認識は、アレバロがカリブ海連隊を支援したこ とでさらに強まり、1950年代にはアメリカ政府はアルベンス政権の転覆を検討するに至った。[17] [18] 米国の態度はモンロー主義の影響も受けていた。これは1823年にジェームズ・モンローが提唱した外交政策理念[19][20]であり、同地域における米 国のヘゲモニー維持を正当化するものであった[21]。この主義の公的な目的は秩序と安定を維持し、資源と市場へのアクセスが制限されないことを保証する ことにあった。[22] 歴史家マーク・ギルダーハスは、この教義には人種的に見下した表現も含まれており、ラテンアメリカ諸国を喧嘩する子供たちに例えたと指摘している。 [23] 1944年以前、米国政府はこのヘゲモニーを執行するためにグアテマラへの軍事介入を行う必要はなかった。米国に友好的な軍事政権が存在していたためであ る。[21] |

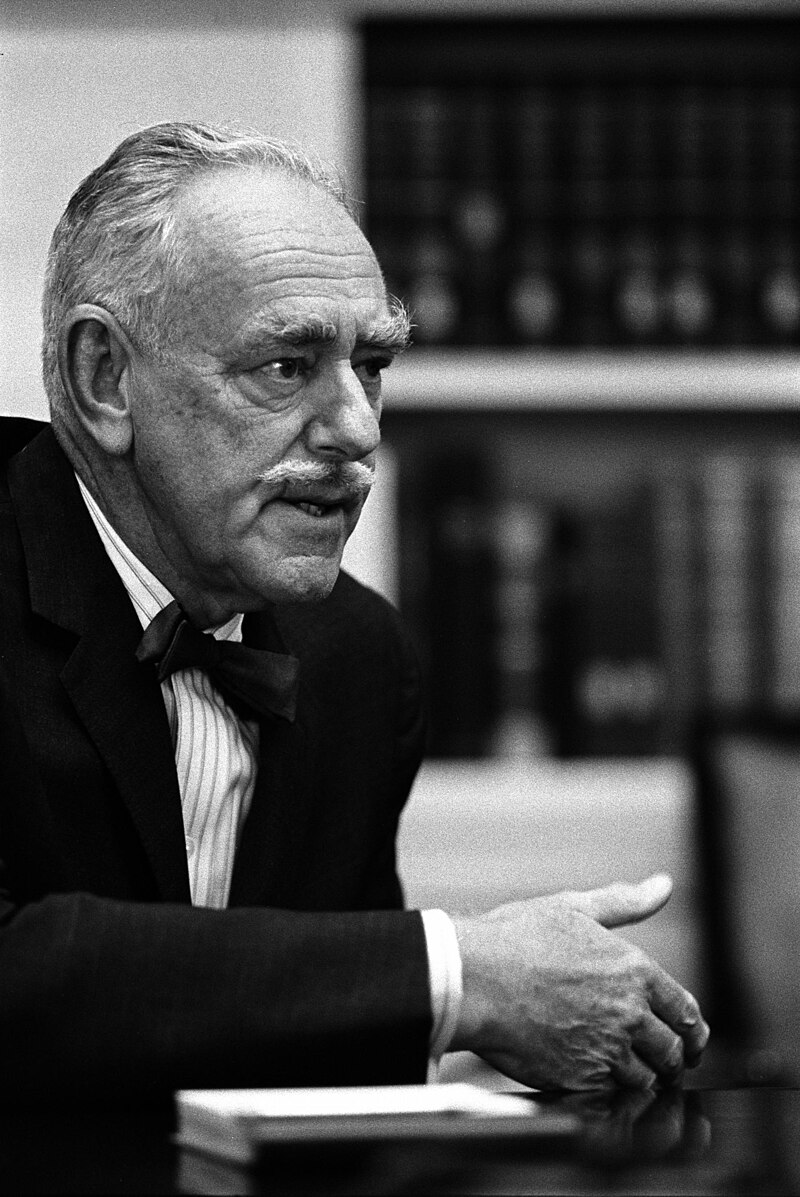

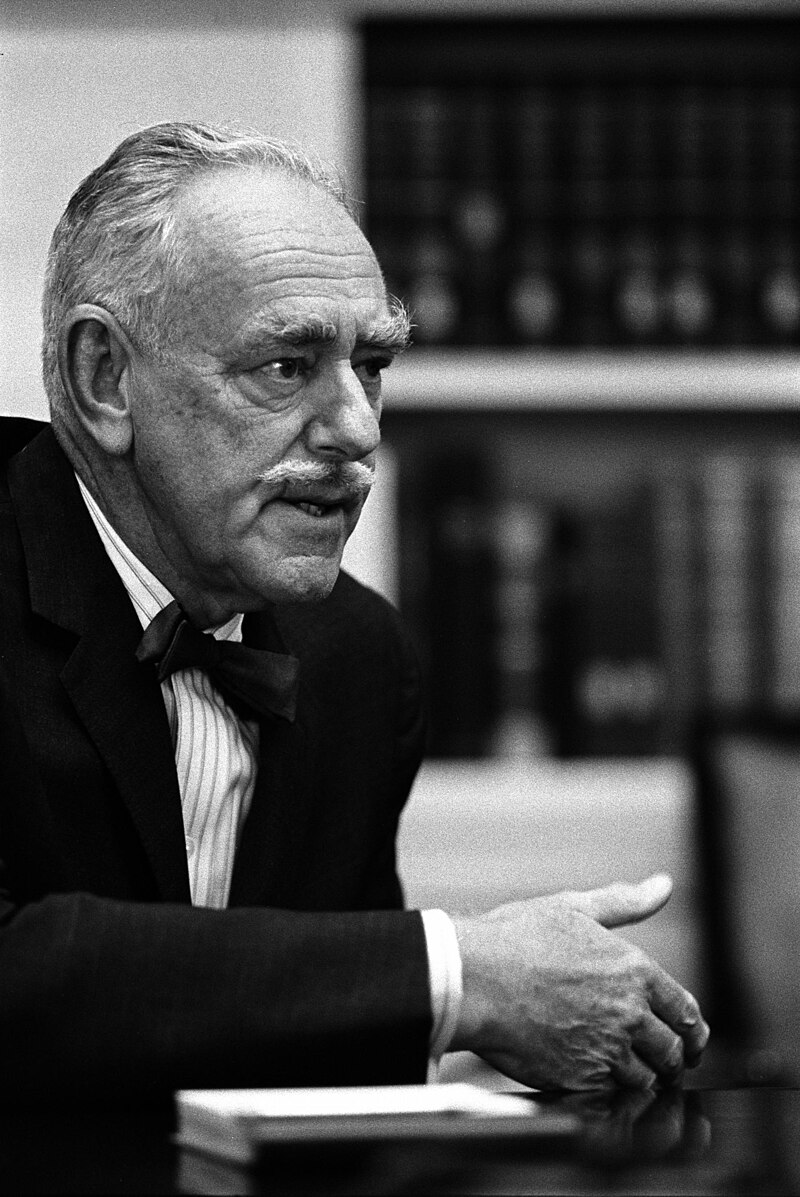

Planning A portrait photograph of Walter Bedell Smith, pictured in uniform Walter Bedell Smith, the Director of Central Intelligence during the operation  A photograph of Allen Dulles, the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles, the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence during the operation Somoza's visit In May 1952, Árbenz enacted Decree 900, the official title of the Guatemalan agrarian reform law.[24] Approximately 500,000 people benefited from the decree.[25] The United Fruit Company lost several hundred thousand acres of its uncultivated land to this law, and the compensation it received was based on the undervalued price it had presented to the Guatemalan government for tax purposes.[17] The company therefore intensified its lobbying in Washington D.C. against the Guatemalan government.[17] The law convinced the US government that the Guatemalan government was being influenced by communists.[24] The US government's Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) started to explore the notion of lending support to detractors and opponents of Árbenz. Walter Bedell Smith, the Director of Central Intelligence, ordered J. C. King, the chief of the Western Hemisphere Division, to examine whether dissident Guatemalans could topple the Árbenz government if they had support from the dictatorships in Central America.[26] At this point the US government was approached by Nicaraguan leader Somoza, who had been in the United States on a private visit, during which he made public speeches praising the US, and was awarded a medal by New York City.[27][28] During a meeting with Truman and his senior staff, Somoza said that if he were given the weapons, he would "clean up Guatemala".[27] Truman's personal military advisor, Major General Harry H. Vaughan, persuaded Truman to explore the opportunity further, and Truman asked Smith to follow up.[28] |

計画 軍服姿のウォルター・ベデル・スミスの肖像写真 作戦期間中の中央情報局長官、ウォルター・ベデル・スミス  中央情報局副長官アレン・ダレスの写真 作戦期間中の中央情報局副長官アレン・ダレス ソモサの訪問 1952年5月、アルベンスはグアテマラ農地改革法の正式名称である法令900号を公布した[24]。約50万人がこの法令の恩恵を受けた。[25] ユナイテッド・フルーツ社はこの法律により、未耕作地数十万エーカーを失った。同社が受け取った補償金は、税務目的でグアテマラ政府に提示した過小評価価 格に基づいて算定された。[17] そのため同社はワシントンD.C.でグアテマラ政府に対するロビー活動を強化した。[17] この法律は、グアテマラ政府が共産主義者の影響下にあると米国政府に確信させた。[24] 米国政府の中央情報局(CIA)は、アルベンス政権の批判者や反対派を支援する構想の検討を開始した。中央情報局長官ウォルター・ベデル・スミスは、西半 球部長J・C・キングに対し、反体制派のグアテマラ人が中米の独裁政権から支援を得ればアルベンス政権を打倒できるか調査するよう命じた。[26] この時点で、ニカラグアの指導者ソモサが米国政府に接触してきた。ソモサは私的な訪問で米国に滞在中、米国を称賛する公の演説を行い、ニューヨーク市から 勲章を授与されていた。[27][28] トルーマン大統領と上級スタッフとの会談で、ソモサは武器が提供されれば「グアテマラを一掃する」と述べた。[27] トルーマンの人格軍事顧問であるハリー・H・ヴォーン少将は、この機会をさらに探るよう大統領を説得し、トルーマンはスミスに追跡調査を指示した。 [28] |

| Carlos Castillo Armas Although the proposal was not taken seriously at the time, US Colonel Cornelius Mara flew back to Nicaragua with Somoza to further explore the idea.[27] Somoza persuaded Mara that the plan was feasible, and Mara returned to the US and gave Truman a favorable report.[29] Smith also sent a Spanish-speaking engineer[a] under the codename "Seekford"[31] to contact exiled Guatemalan Army officer Carlos Castillo Armas and his fellow dissidents, who were in Honduras and Guatemala.[28] Francisco Javier Arana had launched an ill-fated coup attempt against Arévalo in 1949.[32] Castillo Armas had been a protégé of Arana, and had risen in the military to become the head of the military academy of Guatemala by 1949.[33] Historians differ on what happened to Castillo Armas following the coup attempt. Piero Gleijeses writes that Castillo Armas was expelled from the country;[32] Nick Cullather and Andrew Fraser, however, say Castillo Armas was arrested in August 1949,[33] that Árbenz had him imprisoned under doubtful charges until December 1949, and that he was found in Honduras a month later.[33][34] In early 1950, a CIA officer found Castillo Armas attempting to get weapons from Somoza and Trujillo.[33] He met with the CIA a few more times before November 1950, when he launched an attack against Matamoros, the largest fortress in the capital, and was jailed for it before bribing his way out of prison.[35] Castillo Armas told the CIA he had the support of the Guardia Civil (Civil Guard), the garrison at Quetzaltenango, Guatemala's second-largest city, and of the commander of Matamoros.[33] The engineer dispatched by the CIA also told them Castillo Armas had the financial backing of Somoza and Trujillo.[28] Based on these reports, Truman authorized Operation PBFortune. According to Gleijeses, he did not inform the US State Department, or secretary of state Dean Acheson, of the plan.[29] Based upon an examination of declassified documents, however, Cullather has said the CIA did, in fact, seek State Department approval before authorizing the plan, and that undersecretary of state David K. E. Bruce provided explicit approval for it.[36] CIA Deputy Director Allen Dulles had previously contacted State Department official Thomas Mann and the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Edward G. Miller Jr. Both these individuals had said they wanted a new government in Guatemala even if it involved the use of force, but when asked, did not explicitly approve of action to topple Árbenz. Dulles assumed their vague responses implied support, but obtained explicit assent from Bruce before proceeding.[36] |

カルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマス 当時この提案は真剣に受け止められなかったが、米軍のコーネリアス・マラ大佐はソモサと共にニカラグアへ戻り、この構想をさらに探った。[27] ソモサはマラに計画の実現可能性を説得し、マラは米国に戻ってトルーマンに好意的な報告を行った。[29] スミスはまた、スペイン語を話す技術者[a]を「シークフォード」[31]というコードネームで派遣し、亡命中のグアテマラ軍将校カルロス・カスティー ヨ・アルマスとその同志たち(ホンジュラスとグアテマラにいた)と接触させた。[28] フランシスコ・ハビエル・アラナは、1949 年にアレバロに対して不運なクーデターを試みた。[32] カスティージョ・アルマスはアラナの弟子であり、軍隊で頭角を現し、1949 年までにグアテマラ陸軍士官学校の校長にまで昇進していた。[33] クーデター未遂後のカスティージョ・アルマスの運命については、歴史家の見解が異なる。ピエロ・グレイヘセスは、カスティージョ・アルマスが国外追放され たと記している[32]。しかし、ニック・カラザーとアンドルー・フレイザーは、カスティージョ・アルマスが1949年8月に逮捕され[33]、アルベン スが疑わしい容疑で1949年12月まで投獄し、1か月後にホンジュラスで発見されたと述べている[33]。[34] 1950年初頭、CIAの職員は、カスティージョ・アルマスがソモサとトルヒーヨから武器を入手しようとしていることを発見した[33]。彼は1950年 11月までにさらに数回CIAと会合を持ち、その後、首都最大の要塞であるマタモロスを攻撃したが、その罪で投獄された。[35] カスティージョ・アルマスはCIAに対し、グアテマラ第2の都市ケツァルテナンゴの駐屯部隊であるグアルディア・シビル(治安警察)と、マタモロス要塞司 令官の支持を得ていると伝えた。[33] CIAが派遣した技術者も、カスティージョ・アルマスがソモサとトルヒーヨから資金援助を受けていると報告した。[28] これらの報告に基づき、トルーマンは「PBFortune作戦」を承認した。グレイヘセスによれば、彼はこの計画を米国務省やディーン・アチソン国務長官 に報告しなかったという[29]。しかし機密解除文書を検証したカラザーは、実際にはCIAが計画承認前に国務省の承認を求めており、デイヴィッド・K・ E・ブルース国務次官が明示的な承認を与えたと述べている。[36] CIA副長官アレン・ダレスは事前に国務省職員トーマス・マンと米州担当国務次官補エドワード・G・ミラー・ジュニアに接触していた。両者とも武力行使を 伴う場合でもグアテマラに新政府を樹立したいと述べていたが、アルベンス政権打倒行動については明示的な承認を求められても明言を避けた。ダレスは彼らの 曖昧な回答を支持の意思と解釈したが、実行前にブルースから明示的な同意を得ていた。[36] |

| The plot The details of the plot were finalized over the next few weeks by the CIA, the United Fruit Company, and Somoza.[29] The coup's plotters contacted Trujillo and Jiménez, who, along with Somoza and Juan Manuel Gálvez, the right-wing President of Honduras, had already been exchanging intelligence about the Árbenz government, and had considered the possibility of supporting an invasion by Guatemalan exiles.[29][37] The two dictators were supportive of the plan, and agreed to contribute some funding.[29] Although PBFortune was officially approved on September 9, 1952, planning had begun earlier in the year. In January 1952, officers in the CIA's Directorate of Plans compiled a list of "top flight Communists whom the new government would desire to eliminate immediately in the event of a successful anti-Communist coup".[38] The assassination plans represented the first time the US had considered assassination in Guatemala.[39] The list of targets had been drawn up by the CIA even before the operation had been formally authorized. They were created using a list of communists that the Guatemalan Army had compiled in 1949, as well as its own intelligence.[31] Nine months later the CIA also received through "Seekford" a list of 58 Guatemalans whom Castillo Armas wanted killed, in addition to 74 others he wanted arrested or exiled.[31] "Seekford" also said Trujillo's support was conditional on the assassination of four individuals from Santo Domingo who were at that point living in Guatemala.[31] The plan was to be carried out by Castillo Armas, and involve no direct intervention from the US.[29] When contacted by the CIA agent dispatched by Smith, Castillo Armas had proposed a battle-plan to gain CIA support. This plan involved three forces invading Guatemala from Mexico, Honduras, and El Salvador.[28] These invasions were supposed to be supported by internal rebellions.[28][b] King formulated a plan to provide Castillo Armas with $225,000 as well as weaponry and transportation. His plan also suggested that Somoza and Gálvez be persuaded to provide air support, in addition to other help.[36] The proposal went to Dulles. It emphasized the relatively small role the CIA was supposed to play, and stated that without the CIA's support, the plot would probably go ahead, but would likely fail and lead to a crackdown on anti-Communist forces.[36] |

陰謀 CIA、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社、ソモサによって、その陰謀の詳細はその後数週間で最終決定された。[29] クーデター計画の首謀者たちはトルヒーヨとヒメネスに接触した。両者はソモサやホンジュラスの右派大統領フアン・マヌエル・ガルベスと共に、既にアルベン ス政権に関する情報を交換しており、グアテマラ亡命者による侵攻を支援する可能性を検討していた。[29][37] 両独裁者は計画を支持し、資金の一部提供に合意した。[29] PBFortune作戦は1952年9月9日に正式承認されたが、計画は同年早々に始まっていた。1952年1月、CIA計画局の将校たちは「反共クーデ ター成功時に新政府が即時排除を望む共産主義者上位リスト」を作成した。[38] この暗殺計画は、米国がグアテマラで暗殺を検討した初めての事例であった。[39] 標的リストは作戦が正式に承認される前からCIAによって作成されていた。グアテマラ軍が1949 年にまとめた共産主義者リストと、CIA自身の情報に基づいて作成されたものである。[31] 9か月後、CIAは「シークフォード」経由で、カスティージョ・アルマスが殺害を望んだ58名のグアテマラ人リストと、逮捕または追放を望んだ74名のリ ストも受け取った。[31] 「シークフォード」はまた、トルヒーヨの支援は、当時グアテマラに居住していたサントドミンゴ出身の4名の暗殺を条件としていると伝えた。[31] この計画はカスティージョ・アルマスが実行し、米国による直接介入は伴わないものだった。[29] スミスが派遣したCIA工作員から接触を受けたカスティージョ・アルマスは、CIAの支援を得るための作戦計画を提案していた。この計画では、メキシコ、 ホンジュラス、エルサルバドルの三方向からグアテマラへ侵攻する部隊を配置する予定だった。[28] これらの侵攻は、国内での反乱運動によって支援されるはずだった。[28][b] キングは、カスティージョ・アルマスに22万5千ドルと武器、輸送手段を提供する計画を立案した。彼の計画では、ソモサとガルベスに対し、その他の支援に 加え航空支援を提供するよう説得することも提案されていた。[36] この提案はダレスに提出された。そこではCIAが担う役割は比較的小さいと強調され、CIAの支援がなければ計画はおそらく実行されるが、失敗して反共産 勢力への弾圧を招く可能性が高いと述べられていた。[36] |

Execution and termination A photograph of Dean Acheson, the US Secretary of State US Secretary of State Dean Acheson, whose intervention ended the operation The plan was put into motion in autumn 1952 by the CIA.[40] King had obtained weapons from the stock of those that had been confiscated by port authorities in the city of New York. These included 250 rifles, 380 pistols, 64 machine guns, and 4,500 grenades.[1][c] The United Fruit Company lent one of its freighters to the CIA. The freighter was specially refitted in New Orleans, and loaded with weapons under the guise of agricultural machinery.[40] It was scheduled to sail to Nicaragua in early October 1952.[2] The CIA had encouraged Somoza and Gálvez to provide support to Castillo Armas' forces. Somoza, however, informed several government officials across Central America of the CIA's role in the coup attempt. Somoza's son Tacho, for instance, casually asked Miller whether "the machinery" was on its way at a meeting in Panama.[2] Accounts of the operation's termination vary between historians. Gleijeses said that while the freighter was on its way to Nicaragua, a CIA employee went to Miller, and asked him to sign a document on behalf of the munitions department.[29] Miller refused, and instead showed the document to his superiors, who in turn informed Acheson.[29] Gleijeses writes that Acheson immediately spoke to Truman as a result of this document, and the operation was cut short.[29] Nick Cullather writes that, due to Somoza spreading the word about the coup, the State Department decided the cover of the operation had been lost.[2] Other diplomats began to learn of the operation, and on October 8, Acheson summoned Smith and called it off.[2] Acheson was particularly worried that allowing the details of the coup to go public would damage the image of the US. Under the Rio Pact of 1947, the Organization of American States (OAS) had obtained jurisdiction over regional disputes from the United Nations.[2] To achieve this, the US had also committed to a policy of non-intervention in the internal affairs of other countries. If PBFortune had become public knowledge, the fact that the US was supporting an invasion of a fellow member of the OAS would have represented a huge setback to US policy,[2] thus motivating the State Department to end the operation when they became aware its cover had been blown.[2] |

執行と終結 米国務長官ディーン・アチソンの写真 作戦を終了させた介入を行った米国務長官ディーン・アチソン この計画は1952年秋にCIAによって実行に移された。[40] キングはニューヨーク市の港湾当局が押収した武器の在庫から武器を入手していた。これには小銃250丁、拳銃380丁、機関銃64丁、手榴弾4,500発 が含まれていた。[1][c] ユナイテッド・フルーツ社は自社貨物船1隻をCIAに貸与した。同船はニューオーリンズで特別改造され、農業機械を装って武器を積載した。[40] 1952年10月初旬にニカラグアへ向けて出航する予定だった。[2] CIAはソモサとガルベスに対し、カスティーヨ・アルマス軍への支援を促していた。しかしソモサは、中米各地の政府高官数名にCIAのクーデター関与を伝えた。例えば息子のタチョは、パナマでの会合でミラーに「あの機械類」が到着したかと何気なく尋ねた。[2] 作戦中止の経緯については歴史家によって見解が異なる。グレイヘセスによれば、貨物船がニカラグアへ向かう途中、CIA職員がミラーを訪れ、兵器部門名義 の文書への署名を要求したという。[29] ミラーはこれを拒否し、代わりに文書を上司に提示。上司はアチソンに報告した。[29] グレイヘセスによれば、この文書を受け取ったアチソンは直ちにトルーマン大統領に報告し、作戦は打ち切られたという。[29] ニック・カラザーは、ソモサがクーデター計画を漏らしたため、国務省が作戦の秘密保持が不可能と判断したと記している。[2] 他の外交官たちも作戦の存在を知り始め、10月8日にアチソンはスミスを呼び出して作戦を中止させた。[2] アチソンは特に、クーデターの詳細が公になれば米国のイメージを損なうことを懸念していた。1947年のリオ条約により、米州機構(OAS)は国連から地 域紛争の管轄権を移管されていた。[2] このため米国は他国の内政不干渉政策も約束していた。もしPBFortune作戦が公になれば、米国がOAS加盟国への侵攻を支援している事実が明らかに なり、米国政策にとって重大な後退となっていた[2]。このため国務省は作戦の秘密が漏れたと知ると、直ちに中止を決断したのである[2]。 |

| Aftermath Further information: 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état and Guatemalan Civil War The termination of the operation caught the CIA by surprise, and King quickly attempted to salvage what he could.[2] The freighter was redirected to Panama, where the arms were unloaded;[29] King kept the weapons there in the hope that the project could be rejuvenated.[2] Castillo Armas was paid a retainer of $3,000 a week, which allowed him to maintain a small force. The CIA remained in contact with him, and continued to provide support to the rebels.[41] The CIA found it difficult to end the operation without drawing attention to it.[42] Peréz Jimenez opened a line of credit that would allow Castillo Armas to purchase airplanes, and Trujillo and Somoza continued to support the operation, although they acknowledged it would have to be postponed.[42] The money paid to Castillo Armas has been described as a way of making sure he did not attempt any premature action.[42] Even after the operation had been terminated, the CIA received reports from "Seekford" that the Guatemalan rebels were planning assassinations. Castillo Armas made plans to use groups of soldiers in civilian clothing from Nicaragua, Honduras, and El Salvador to kill communist leaders in Guatemala.[43] King continued to explore the CIA's ability to move arms around Central America without the approval of the State Department.[41] In November 1952, Dwight Eisenhower was elected president of the US after a campaign promising a more hawkish stance against communism. Many senior figures in his cabinet, including John Foster Dulles and his brother Allen, had close connections to the United Fruit Company, which made Eisenhower more strongly predisposed than Truman to support Árbenz's overthrow.[41][44] In June 1954, the US trained and funded an invasion force led by Castillo Armas, backed by an intense campaign of psychological warfare by the CIA.[45] Gálvez, Somoza, Jiménez, and Trujillo again offered the CIA their support in preparing for this operation.[46] Árbenz resigned on June 27, 1954, ending the Guatemalan Revolution.[47][48] Following his resignation, the CIA launched Operation PBHistory, an attempt to use documents from Árbenz's government and elsewhere to justify the coup in response to the negative international reactions to it.[49] From 1954 onward Guatemala was ruled by a series of US-backed military dictators, leading to the Guatemalan Civil War which lasted until 1996.[50] Approximately 200,000 civilians were killed in the war, and numerous human rights violations committed, including massacres of civilian populations, rape, aerial bombardment, and forced disappearances.[51] Of these violations, 93 percent were committed by the United States-backed military, which included a genocidal scorched-earth campaign against the indigenous Maya population in the 1980s.[51] |

余波 詳細情報: 1954年グアテマラクーデターおよびグアテマラ内戦 作戦の中止はCIAを驚かせ、キングは急いで可能な限りの救済を試みた。[2] 貨物船はパナマへ進路を変更し、そこで武器は荷揚げされた。[29] キングは計画が再始動する可能性を期待し、武器を現地に保管した。[2] カスティージョ・アルマスには週3000ドルの報酬が支払われ、これにより彼は小規模な部隊を維持できた。CIAは彼との連絡を保ち、反乱軍への支援を継 続した。[41] CIAは作戦を終了させる際、注目を集めずに済ませることが困難だと感じた。[42] ペレス・ヒメネスはカスティージョ・アルマスが航空機を購入できる信用枠を開設した。トルヒーヨとソモサも作戦支援を継続したが、延期が必要だと認めてい た。[42] カスティージョ・アルマスへの支払いは、彼が時期尚早な行動に出ないよう抑止する手段と説明されている。作戦終了後もCIAは「シークフォード」から、グ アテマラ反乱勢力が暗殺を計画しているとの報告を受けた。カスティージョ・アルマスはニカラグア、ホンジュラス、エルサルバドルから民間人装いの兵士グ ループを動員し、グアテマラの共産主義指導者を殺害する計画を立てた。キングは国務省の承認なしに中米で武器を移動させるCIAの能力を引き続き模索し た。[41] 1952年11月、ドワイト・アイゼンハワーは共産主義に対するより強硬な姿勢を公約に掲げた選挙戦を経て米国大統領に選出された。ジョン・フォスター・ ダレスとその弟アレンを含む彼の内閣の多くの上級要人はユナイテッド・フルーツ社と密接な関係を持っており、これがアイゼンハワーをトルーマンよりもアル ベンス政権打倒を支持する方向に強く傾かせた。[41][44] 1954年6月、米国はCIAによる激しい心理戦キャンペーンを背景に、カスティージョ・アルマス率いる侵攻部隊を訓練・資金援助した。[45] ガルベス、ソモサ、ヒメネス、トルヒーヨは再びこの作戦準備においてCIAに支援を申し出た。[46] アルベンスは1954年6月27日に辞任し、グアテマラ革命は終結した。[47][48] 辞任後、CIAは「PBHistory作戦」を開始した。これは国際的な非難への対応として、アルベンス政権や他機関の文書を利用しクーデターを正当化し ようとする試みであった。[49] 1954年以降、グアテマラは米国が支援する一連の軍事独裁政権によって支配され、1996年まで続くグアテマラ内戦へと発展した。[50] この戦争で約20万人の民間人が殺害され、民間人虐殺、強姦、空爆、強制失踪など数多くの人権侵害が行われた。[51] これらの侵害行為の93%は米国が支援する軍隊によって行われ、1980年代には先住民マヤ族に対するジェノサイド的な焦土作戦も含まれていた。[51] |

| a.

Secret History, by Nick Cullather, is based on declassified documents

from the US Central Intelligence Agency. Several of these documents are

redacted, leaving out certain details. These redactions have been

reproduced in Cullather's text.[30] The name of the engineer dispatched

to Guatemala has been redacted.[28] b. The name of the individual who was supposed to lead the internal uprisings has been redacted in the CIA documents.[28] c. Details of other types of weapons have been redacted in the CIA documents.[36] |

a.

ニック・カラザー著『シークレット・ヒストリー』は、米国中央情報局(CIA)の機密解除文書に基づいている。これらの文書の一部は編集されており、特定

の詳細が省かれている。これらの編集箇所はカラザーのテキストに再現されている[30]。グアテマラに派遣された技術者の名前は編集されている。[28] b. 内部反乱を主導する予定だった人物の名前は、CIA文書で黒塗りされている。[28] c. その他の種類の武器に関する詳細は、CIA文書で黒塗りされている。[36] |

| Sources Callanan, James (2009). Covert Action in the Cold War: US Policy, Intelligence and CIA Operations. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85771-166-3. Cullather, Nicholas (1999). Secret History: The CIA's Classified Account of its Operations in Guatemala, 1952–1954. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3311-3. De La Pedraja, René (2013). Wars of Latin America, 1948–1982: The Rise of the Guerrillas. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7015-0. Forster, Cindy (2001). The Time of Freedom: Campesino Workers in Guatemala's October Revolution. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-4162-0. Fraser, Andrew (August 2006). "Architecture of a Broken Dream: The CIA and Guatemala, 1952–54". Intelligence and National Security. 20 (3): 486–508. doi:10.1080/02684520500269010. S2CID 154550395. Gilderhus, Mark T. (March 2006). "The Monroe Doctrine: Meanings and Implications". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 36 (1): 5–16. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2006.00282.x. JSTOR 27552742. Gleijeses, Piero (1991). Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944–1954. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02556-8. Grandin, Greg (2000). The Blood of Guatemala: A History of Race and Nation. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2495-9. Haines, Gerald (June 1995). "CIA and Guatemala Assassination Proposals, 1952–1954" (PDF). CIA Historical Review Program. Hanhimäki, Jussi; Westad, Odd Arne (2004). The Cold War: A History in Documents and Eyewitness Accounts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927280-8. Holland, Max (2004). "Operation PBHistory: The Aftermath of SUCCESS". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 17 (2): 300–332. doi:10.1080/08850600490274935. S2CID 153570470. Immerman, Richard H. (1982). The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2. McAllister, Carlota (2010). "A Headlong Rush into the Future". In Grandin, Greg; Joseph, Gilbert (eds.). A Century of Revolution. Duke University Press. pp. 276–309. ISBN 978-0-8223-9285-9. Moulton, Aaron Coy (July 2013). ""Amplies Ayuda Externa" Contra "La Gangrena Comunista": Las Fuerzas Regionales Anticomunistas y la Finalizacion de la Operacion PBFortune, Octobre de 1952" ["Extend External Assistance" Against "The Communist Gangrene": The Regional Anti-Communist Forces and the Finalization of Operation PBFortune, October 1952]. Revista de Historia de América (in Spanish) (149): 45–58. JSTOR 44732841. Schlesinger, Stephen; Kinzer, Stephen (1999). Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. David Rockefeller Center series on Latin American studies, Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-674-01930-0. Streeter, Stephen M. (2000). Managing the Counterrevolution: The United States and Guatemala, 1954–1961. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-89680-215-5. |

出典 キャラナン、ジェームズ(2009)。『冷戦下の秘密作戦:米国の政策、諜報活動、CIA作戦』。アイ・ビー・トーリス。ISBN 978-0-85771-166-3。 カラザー、ニコラス(1999)。『秘密の歴史:CIAのグアテマラ作戦機密記録、1952–1954』。スタンフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8047-3311-3。 デ・ラ・ペドラハ、ルネ(2013)。『ラテンアメリカの戦争、1948–1982:ゲリラの台頭』。マクファーランド。ISBN 978-0-7864-7015-0。 フォスター、シンディ(2001)。自由の時代:グアテマラの十月革命における農民労働者。ピッツバーグ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8229-4162-0。 フレイザー、アンドルー(2006年8月)。「破れた夢の構造:CIAとグアテマラ、1952年から1954年」。インテリジェンスと国民安全保障。20 (3): 486–508. doi:10.1080/02684520500269010. S2CID 154550395. ギルダーハス、マーク T. (2006年3月)。「モンロー主義:その意味と影響」。大統領研究季刊誌。36 (1): 5–16. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2006.00282.x. JSTOR 27552742. グレイジェセス、ピエロ(1991年)。『打ち砕かれた希望:グアテマラ革命とアメリカ合衆国、1944–1954年』。プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-691-02556-8。 グランディン、グレッグ(2000年)。『グアテマラの血:人種と国民の歴史』。デューク大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8223-2495-9。 ヘインズ、ジェラルド(1995年6月)。「CIAとグアテマラ暗殺計画、1952–1954年」(PDF)。CIA歴史レビュープログラム。 ハンヒマキ、ユッシ;ウェスタッド、オッド・アルネ(2004)。『冷戦:文書と目撃証言による歴史』オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-927280-8。 ホランド、マックス(2004)。「作戦PBHistory:SUCCESS作戦の余波」『国際諜報・防諜ジャーナル』17巻2号:300–332頁。doi:10.1080/08850600490274935. S2CID 153570470. イマーマン, リチャード・H. (1982). 『グアテマラにおけるCIA:介入の外交政策』. テキサス大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2. マカリスター、カルロタ(2010)。「未来への突進」。グレッグ・グランディン、ギルバート・ジョセフ(編)。『革命の世紀』。デューク大学出版局。276–309頁。ISBN 978-0-8223-9285-9。 モルトン、アーロン・コイ(2013年7月)。「外部援助の拡大」対「共産主義の壊疽」:地域反共勢力とPBFortune作戦の終結、1952年10月。『アメリカ歴史雑誌』(スペイン語)(149): 45–58. JSTOR 44732841. シュレジンジャー、スティーブン; キンザー、スティーブン (1999). 『苦い果実:グアテマラにおけるアメリカのクーデター物語』. ハーバード大学デイヴィッド・ロックフェラー・センター・ラテンアメリカ研究シリーズ. ISBN 978-0-674-01930-0。 ストリーター、スティーブン・M.(2000)。『反革命の管理:アメリカとグアテマラ、1954–1961年』。オハイオ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-89680-215-5。 |

| Declassified CIA documents relevant to the Guatemalan Revolution CIA and Guatemala Assassination Proposals: CIA History Staff Analysis |

グアテマラ革命に関連する機密解除されたCIA文書 s:CIAとグアテマラ暗殺計画:CIA歴史部分析 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_PBFortune |

|

☆Operation PBSuccess(オペレーションPBサクセス=CIAによる1954年のグアテマラのクーデター計画)

| Operation PBSuccess Planning  File photo of Allen Dulles Allen Dulles, director of the CIA during the 1954 coup, and brother of U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles Eisenhower authorized the CIA operation to overthrow Jacobo Árbenz, code-named Operation PBSuccess, in August 1953. The operation was granted a budget of 2.7 million U.S. dollars[f] for "psychological warfare and political action".[88] The total budget has been estimated at between 5 and 7 million dollars, and the planning employed over 100 CIA agents.[89] In addition, the operation recruited scores of individuals from among Guatemalan exiles and the populations of the surrounding countries.[89] The plans included drawing up lists of people within Árbenz's government to be assassinated if the coup were to be carried out. Manuals of assassination techniques were compiled, and lists were also made of people whom the junta would dispose of.[88] These were the CIA's first known assassination manuals, and were reused in subsequent CIA actions.[90] The State Department created a team of diplomats who would support PBSuccess. It was led by John Peurifoy, who took over as Ambassador to Guatemala in October 1953.[91][92] Another member of the team was William D. Pawley, a wealthy businessman and diplomat with extensive knowledge of the aviation industry.[93] Peurifoy was a militant anti-communist, and had proven his willingness to work with the CIA during his time as United States Ambassador to Greece.[94] Under Peurifoy's tenure, relations with the Guatemalan government soured further, although those with the Guatemalan military improved. In a report to John Dulles, Peurifoy stated that he was "definitely convinced that if [Árbenz] is not a communist, then he will certainly do until one comes along".[95] Within the CIA, the operation was headed by Deputy Director of Plans Frank Wisner. The field commander selected by Wisner was former U.S. Army Colonel Albert Haney, then chief of the CIA station in South Korea. Haney reported directly to Wisner, thereby separating PBSuccess from the CIA's Latin American division, a decision which created some tension within the agency.[96] Haney decided to establish headquarters in a concealed office complex in Opa-locka, Florida.[97] Codenamed "Lincoln", it became the nerve center of Operation PBSuccess.[98] The CIA operation was complicated by a premature coup on 29 March 1953, with a futile raid against the army garrison at Salamá, in the central Guatemalan department of Baja Verapaz. The rebellion was swiftly crushed, and a number of participants were arrested. Several CIA agents and allies were imprisoned, weakening the coup effort. Thus the CIA came to rely more heavily on the Guatemalan exile groups and their anti-democratic allies in Guatemala.[99] The CIA considered several candidates to lead the coup. Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, the conservative candidate who had lost the 1950 election to Árbenz, held favor with the Guatemalan opposition but was rejected for his role in the Ubico regime, as well as his European appearance, which was unlikely to appeal to the majority mixed-race mestizo population.[100] Another popular candidate was the coffee planter Juan Córdova Cerna, who had briefly served in Arévalo's cabinet before becoming the legal adviser to the UFC. The death of his son in an anti-government uprising in 1950 turned him against the government, and he had planned the unsuccessful Salamá coup in 1953 before fleeing to join Castillo Armas in exile. Although his status as a civilian gave him an advantage over Castillo Armas, he was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1954, taking him out of the reckoning.[101] Thus it was Castillo Armas, in exile since the failed 1949 coup and on the CIA's payroll since the aborted PBFortune in 1951, who was to lead the coming coup.[67] |

オペレーション・ピービーサクセス 計画  アレン・ダレスのファイル写真 1954年のクーデター当時CIA長官であり、米国務長官ジョン・フォスター・ダレスの弟であるアレン・ダレス アイゼンハワーは1953年8月、コードネーム「オペレーション・ピービーサクセス」によるハコボ・アルベンス打倒作戦をCIAに許可した。作戦には「心 理戦と政治工作」のために270万米ドル[f]の予算が割り当てられた[88]。総予算は500万~700万ドルと推定され、計画には100人以上の CIA工作員が動員された[89]。さらに、グアテマラ亡命者や周辺国の人々から多数の協力者を募った。[89] 計画には、クーデター実行時に暗殺対象とするアルベンス政権関係者のリスト作成が含まれていた。暗殺技術マニュアルが編纂され、軍事政権が排除すべき人物 リストも作成された[88]。これらはCIA初の暗殺マニュアルとして知られ、後のCIA作戦で再利用された。[90] 国務省はPBSuccessを支援する外交官チームを編成した。チームはジョン・ピュリフォイが率い、彼は1953年10月にグアテマラ大使に就任した。 [91] [92] チームのもう一人のメンバーは、航空産業に精通した富裕な実業家兼外交官ウィリアム・D・ポーリーであった。[93] ピュリフォイは過激な反共主義者であり、在ギリシャ米国大使時代にはCIAとの協力姿勢を既に示していた。[94] ピュリフォイの在任中、グアテマラ政府との関係はさらに悪化したものの、グアテマラ軍との関係は改善した。ピュリフォイはジョン・ダレスへの報告書で「ア ルベンスが共産主義者でなくとも、共産主義者が現れるまでは確実にその役割を果たすだろう」と断言した。[95] CIA内部では、作戦は計画部副部長フランク・ウィズナーが指揮した。ウィズナーが選んだ現地指揮官は、当時韓国駐在CIA支局長だった元米陸軍大佐アル バート・ヘイニーであった。ヘイニーはウィズナーに直接報告したため、PBSuccess作戦はCIAのラテンアメリカ部門から分離された。この決定は機 関内に若干の緊張を生んだ[96]。ヘイニーはフロリダ州オパロッカの隠蔽されたオフィス複合施設に司令部を設置することを決定した[97]。コードネー ム「リンカーン」と名付けられたこの施設は、PBSuccess作戦の中枢となった[98]。 CIAの作戦は、1953年3月29日に起きた時期尚早なクーデターによって複雑化した。グアテマラ中部バハ・ベラパス県のサラマにある陸軍駐屯地への襲 撃は失敗に終わり、反乱は迅速に鎮圧された。多数の参加者が逮捕され、複数のCIA工作員や協力者が投獄されたことでクーデター勢力は弱体化した。こうし てCIAは、グアテマラ亡命グループと国内の反民主主義勢力への依存度を高めていった。[99] CIAはクーデター指導者として複数の候補を検討した。1950年の選挙でアルベンスに敗れた保守派候補ミゲル・イディゴラス・フエンテスはグアテマラ野 党の支持を得ていたが、ウビコ政権での役割と、混血メスティソが多数を占める国民に受け入れられにくいヨーロッパ風の風貌が理由で却下された。[100] もう一人の有力候補はコーヒー農園主フアン・コルドバ・セルナであった。彼はアレバロ内閣に短期間在籍した後、UFCの法律顧問となった。1950年の反 政府蜂起で息子を失ったことで政府に反旗を翻し、1953年にはサラマクーデターを計画したが失敗に終わり、亡命中のカスティーヨ・アルマスに合流するた め国外へ逃亡した。民間人という立場はカスティージョ・アルマスより有利だったが、1954年に喉頭癌と診断され、候補から外れた。[101] こうして、1949年のクーデター失敗以来亡命し、1951年のPBFortune作戦中止以降CIAの給与を受けていたカスティージョ・アルマスが、次 のクーデターを主導することになった。[67] |

| Castillo Armas was given enough

money to recruit a small force of mercenaries from among Guatemalan

exiles and the populations of nearby countries. This band was called

the Army of Liberation. The CIA established training camps in Nicaragua

and Honduras and supplied them with weapons as well as several bombers.

The U.S. signed military agreements with both those countries prior to

the invasion of Guatemala, allowing it to move heavier arms

freely.[102] The CIA trained at least 1,725 foreign guerillas plus

thousands of additional militants as reserves.[103] These preparations

were only superficially covert: the CIA intended Árbenz to find out

about them, as a part of its plan to convince the Guatemalan people

that the overthrow of Árbenz was a fait accompli. Additionally, the CIA

made covert contact with a number of church leaders throughout the

Guatemalan countryside, and persuaded them to incorporate

anti-government messages into their sermons.[102] |

カスティーヨ・アルマス(ニックネーム「ナイフ」)は、グアテマラ亡命

者や近隣諸国の住民から小さな傭兵部隊を募集するのに十分な資金を与えられた。この集団は解放軍と呼ばれた。CIAはニカラグアとホンジュラスに訓練キャ

ンプを設置し、武器と数機の爆撃機を供給した。米国はグアテマラ侵攻前に両国と軍事協定を結び、重火器の自由な移動を許可していた[102]。CIAは少

なくとも1,725人の外国人ゲリラに加え、予備兵として数千人の戦闘員を訓練した。[103]

これらの準備は表向きは秘密裏に行われたが、CIAはアルベンスがそれを知ることを意図していた。これはアルベンス政権打倒が既成事実であるとグアテマラ

の人民に納得させる計画の一環だった。さらにCIAはグアテマラ全土の教会指導者らと密かに接触し、説教に反政府メッセージを盛り込むよう説得した。

[102] |

| Caracas conference and U.S. propaganda While preparations for Operation PBSuccess were underway, Washington issued a series of statements denouncing the Guatemalan government, alleging that it had been infiltrated by communists.[104] The State Department also asked the Organization of American States to modify the agenda of the Inter-American Conference, which was scheduled to be held in Caracas in March 1954, requesting the addition of an item titled "Intervention of International Communism in the American Republics", which was widely seen as a move targeting Guatemala.[104] On 29 and 30 January 1954, the Guatemalan government published documents containing information leaked to it by a member of Castillo Armas' team who had turned against him. Lacking in original documents, the government had engaged in poor forgery to enhance the information it possessed, undermining the credibility of its charges.[105] A spate of arrests followed of allies of Castillo Armas within Guatemala, and the government issued statements implicating a "Government of the North" in a plot to overthrow Árbenz. Washington denied these allegations, and the U.S. media uniformly took the side of their government; even publications which had until then provided relatively balanced coverage of Guatemala, such as The Christian Science Monitor, suggested that Árbenz had succumbed to communist propaganda.[106] Several Congressmen also pointed to the allegations from the Guatemalan government as proof that it had become communist.[107] At the conference in Caracas, the various Latin American governments sought economic aid from the U.S., as well as its continuing non-intervention in their internal affairs.[108] The U.S. government's aim was to pass a resolution condemning the supposed spread of communism in the Western Hemisphere. The Guatemalan foreign minister Guillermo Toriello argued strongly against the resolution, stating that it represented the "internationalization of McCarthyism". Despite support among the delegates for Toriello's views, the anti-communist resolution passed with only Guatemala voting against, because of the votes of dictatorships dependent on the U.S. and the threat of economic pressure applied by John Dulles.[109] Although support among the delegates for Dulles' strident anti-communism was less strong than he and Eisenhower had hoped for,[108] the conference marked a victory for the U.S., which was able to make concrete Latin American views on communism.[109] The U.S. had stopped selling arms to Guatemala in 1951 while signing bilateral defense agreements and increasing arms shipments to neighboring Honduras and Nicaragua. The U.S. promised the Guatemalan military that it too could obtain arms—if Árbenz were deposed. In 1953, the State Department aggravated the U.S. arms embargo by thwarting the Árbenz government's arms purchases from Canada, Germany, and Rhodesia.[110][111] By 1954 Árbenz had become desperate for weapons, and decided to acquire them secretly from Czechoslovakia, which would have been the first time that a Soviet bloc country shipped weapons to the Americas, an action seen as establishing a communist beachhead in the Americas.[112][113][114] The weapons were delivered to Guatemala at the Atlantic port of Puerto Barrios by the Swedish freight ship MS Alfhem, which sailed from Szczecin in Poland.[113] The U.S. failed to intercept the shipment despite imposing an illegal naval quarantine on Guatemala.[115] However "Guatemalan army officers" quoted in The New York Times said that "some of the arms ... were duds, worn out, or entirely wrong for use there".[116] The CIA portrayed the shipment of these weapons as Soviet interference in the United States' backyard; it was the final spur for the CIA to launch its coup.[113] U.S. rhetoric abroad also had an effect on the Guatemalan military. The military had always been anti-communist, and Ambassador Peurifoy had applied pressure on senior officers since his arrival in Guatemala in October 1953.[117] Árbenz had intended the secret shipment of weapons from the Alfhem to be used to bolster peasant militias, in the event of army disloyalty, but the U.S. informed army chiefs of the shipment, forcing Árbenz to hand them over to the military, and deepening the rift between him and his top generals.[117] |

カラカス会議と米国のプロパガンダ オペレーションPBSuccessの準備が進む中、ワシントンはグアテマラ政府を非難する一連の声明を発表した。共産主義者に浸透されていると主張したの である。[104] 国務省はまた、1954年3月にカラカスで開催予定だった米州会議の議題変更を米州機構に要請し、「米州諸国における国際共産主義の介入」と題する項目の 追加を求めた。これは広くグアテマラを標的とした動きと見なされた。[104] 1954年1月29日と30日、グアテマラ政府は、カスティージョ・アルマス陣営から離反した人物から漏洩された情報を含む文書を公表した。原本を欠いて いた政府は、所持情報を補強するため拙劣な偽造を行い、告発内容の信憑性を損なった。[105] その後、グアテマラ国内でカスティージョ・アルマス派の支持者に対する一連の逮捕が行われ、政府は「北の政府」がアルベンス政権転覆の陰謀に関与している と示唆する声明を発表した。ワシントンはこれらの主張を否定し、米メディアは一様に政府の立場を支持した。それまでグアテマラ情勢を比較的公平に報じてき た『クリスチャン・サイエンス・モニター』紙でさえ、アルベンスが共産主義プロパガンダに屈したとの見解を示した[106]。複数の米国議会議員も、グア テマラ政府の主張を同国が共産化した証拠として指摘した[107]。 カラカスでの会議で、ラテンアメリカ諸国政府は米国に対し、経済援助と内政不干渉の継続を求めた[108]。米国政府の目的は、西半球における共産主義の 拡散を非難する決議を可決させることだった。グアテマラの外相ギジェルモ・トリエロは、この決議が「マッカーシズムの国際化」を意味すると強く反論した。 トリエロの見解に賛同する代表者もいたにもかかわらず、反共決議は米国に依存する独裁政権の票とジョン・ダレスによる経済的圧力の脅威により、グアテマラ だけが反対票を投じる中で可決された。[109] 代表団の間でダレスの過激な反共主義への支持は、彼とアイゼンハワーが期待したほど強くなかったが[108]、この会議は米国にとって勝利を意味した。米 国はラテンアメリカ諸国の共産主義に対する見解を具体化することに成功したのである[109]。 米国は1951年、グアテマラへの武器販売を停止すると同時に、近隣のホンジュラスとニカラグアとの二国間防衛協定を締結し、これらへの武器供与を拡大し た。米国はグアテマラ軍に対し、アルベンス政権が打倒されれば武器を入手できると約束した。1953年には国務省が、アルベンス政権のカナダ、ドイツ、 ローデシアからの武器購入を妨害し、米国の武器禁輸措置を強化した。[110][111] 1954年までにアルベンスは武器を必死に求めており、チェコスロバキアから密かに調達することを決めた。これはソ連圏の国が初めてアメリカ大陸に武器を 輸送する事例となり、アメリカ大陸における共産主義の前哨基地を確立する行動と見なされた。[112][113] [114] これらの武器は、ポーランドのシュチェチンから出航したスウェーデンの貨物船MSアルフェム号によって、大西洋岸の港湾都市プエルトバリオスに運ばれた。 [113] 米国はグアテマラに対して違法な海上封鎖を課していたにもかかわらず、この輸送を阻止できなかった。[115] しかしニューヨーク・タイムズ紙が引用した「グアテマラ軍将校」によれば、「武器の一部は…不発弾、消耗品、あるいは現地での使用に全く不適切なものだっ た」という。[116] CIAはこの武器輸送を、米国の裏庭におけるソ連の干渉と位置付け、これがCIAによるクーデター実行の最終的な引き金となった。[113] 米国の対外的な言説はグアテマラ軍にも影響を与えた。軍は常に反共主義であり、ピュリフォイ大使は1953年10月にグアテマラ着任以来、上級将校らに圧 力をかけていた。アルフェム号からの武器の秘密輸送は、軍が反旗を翻した場合に備え、農民民兵を強化するためにアルベンスが意図したものだった。しかし米 国は軍首脳部にこの輸送を通知し、アルベンスに武器を軍に引き渡すよう強要した。これにより彼と最高将軍たちの間の亀裂は深まった。 |

| Psychological warfare Castillo Armas' army of 480 men was not large enough to defeat the Guatemalan military, even with U.S.-supplied aircraft. Therefore, the plans for Operation PBSuccess called for a campaign of psychological warfare, which would present Castillo Armas' victory as a fait accompli to the Guatemalan people, and would force Árbenz to resign.[88][118][119] The propaganda campaign had begun well before the invasion, with the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) writing hundreds of articles on Guatemala based on CIA reports, and distributing tens of thousands of leaflets throughout Latin America. The CIA persuaded friendly governments to screen video footage of Guatemala that supported the U.S. version of events.[120] As part of the psychological warfare, the U.S. Psychological Strategy Board authorized a "Nerve War Against Individuals" to instill fear and paranoia in potential loyalists and other potential opponents of the coup. This campaign included death threats against political leaders deemed loyal or deemed to be communist, and the sending of small wooden coffins, non-functioning bombs, and hangman's nooses to such people.[121] The US bombing was also intended to have psychological consequences with E. Howard Hunt of the CIA saying "What we wanted to do was to have a terror campaign, to terrify Arbenz particularly, to terrify his troops, much as the German Stuka bombers terrified the population of Holland, Belgium and Poland".[122][123] Alfhem's success in evading the quarantine led to Washington escalating its intimidation of Guatemala through its navy. On 24 May, the U.S. launched Operation Hardrock Baker, a naval blockade of Guatemala. Ships and submarines patrolled the Guatemalan coasts, and all approaching ships were stopped and searched; these included ships from Britain and France, violating international law.[124] However Britain and France did not protest very strongly, hoping that in return the U.S. would not interfere with their efforts to subdue rebellious colonies in the Middle East. The intimidation was not solely naval; on 26 May one of Castillo Armas' planes flew over the capital, dropping leaflets that exhorted people to struggle against communism and support Castillo Armas.[124] The most wide-reaching psychological weapon was the radio station Voice of Liberation, La Voz de la Liberación. E. Howard Hunt's deputy, David Atlee Phillips, directed the radio station.[125] It began broadcasting on 1 May 1954, carrying anti-communist propaganda, telling its listeners to resist the Árbenz government and support the liberating forces of Castillo Armas. The station claimed to be broadcasting from deep within the jungles of the Guatemalan hinterland, a message which many listeners believed. This belief extended outside of Guatemala itself, with foreign correspondents from publications such as The New York Times believing it to be the most authentic source of information.[126] In actuality, the broadcasts were concocted in Miami by Guatemalan exiles, flown to Central America, and broadcast through a mobile transmitter. The Voice of Liberation made an initial broadcast that was repeated four times, after which it took to transmitting two-hour bulletins twice a day. The transmissions were initially only heard intermittently in Guatemala City; a week later, the CIA significantly increased their transmitting power, allowing clear reception in the Guatemalan capital. The radio broadcasts have been given a lot of credit by historians for the success of the coup, owing to the unrest they created throughout the country. They were unexpectedly assisted by the outage of the government-run radio station, which stopped transmitting for three weeks while a new antenna was being fitted.[127] The Voice of Liberation transmissions continued throughout the conflict, broadcasting exaggerated news of rebel troops converging on the capital, and contributing to massive demoralization among both the army and the civilian population.[128] |

心理戦 カスティージョ・アルマス率いる480名の軍隊は、米国から提供された航空機があってもグアテマラ軍を打ち破るには十分ではなかった。そのため、作戦 「PBSuccess」の計画では、心理戦を展開し、カスティージョ・アルマスの勝利をグアテマラの人民に既成事実として提示し、アルベンスを辞任に追い 込むことが求められた。[88][118] [119] このプロパガンダ作戦は侵攻よりずっと前から始まっていた。米国情報局(USIA)はCIAの報告書に基づきグアテマラに関する数百本の記事を執筆し、ラ テンアメリカ全域に数万枚のビラを配布した。CIAは友好国政府に対し、米国の主張を支持するグアテマラの映像を放映するよう働きかけた。[120] 心理戦の一環として、米国心理戦略委員会は「個人に対する神経戦」を承認した。これはクーデターに反対する可能性のある忠誠派やその他の潜在的な敵対者に 恐怖と妄想を植え付けるためだった。この作戦には、忠誠派と見なされた政治指導者や共産主義者と見なされた者に対する殺害予告、そしてそのような人民への 小さな木製の棺、不発弾、絞首刑用の縄の送付が含まれていた。[121] 米軍の爆撃は心理的効果も意図しており、CIAのE・ハワード・ハントは「我々が望んだのは恐怖作戦であり、特にアルベンツを恐怖に陥れ、その部隊を恐怖 に陥れることだった。ドイツのストゥーカ爆撃機がオランダ、ベルギー、ポーランドの住民を恐怖に陥れたのと同様だ」と述べている。[122] [123] アルフェムが検疫を回避した成功は、ワシントンが海軍を通じてグアテマラへの威嚇をエスカレートさせる結果となった。5月24日、米国はグアテマラに対す る海上封鎖作戦「ハードロック・ベイカー作戦」を発動した。艦船と潜水艦がグアテマラ沿岸を哨戒し、接近する全ての船舶は停止・検査を受けた。これには英 国やフランスの船舶も含まれ、国際法違反であった。[124] しかし英国とフランスは強く抗議しなかった。中東の反乱植民地鎮圧への米国の干渉を避けるためである。威嚇は海軍だけにとどまらなかった。5月26日、カ スティーヨ・アルマス派の航空機が首都上空を飛行し、共産主義との闘争とアルマス支持を呼びかけるビラを投下した。[124] 最も広範な心理的兵器は、ラジオ局「解放の声(La Voz de la Liberación)」であった。E・ハワード・ハントの副官デイヴィッド・アトリー・フィリップスが同局を指揮した[125]。1954年5月1日に 放送を開始し、反共産主義プロパガンダを流して、リスナーにアルベンス政権への抵抗とカスティージョ・アルマス率いる解放勢力の支持を訴えた。同局はグア テマラ奥地の密林深くから放送していると主張し、多くの聴取者がこれを信じた。この認識はグアテマラ国外にも広がり、『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』などの外 国特派員も最も信頼できる情報源とみなした。[126] 実際には放送内容はマイアミのグアテマラ亡命者によって捏造され、中米に空輸された移動式送信機を通じて放送されていた。解放の声は初回放送を4回繰り返 し、その後は1日2回・2時間のニュースを放送した。当初グアテマラシティでは断続的にしか受信できなかったが、1週間後にCIAが送信出力を大幅に増強 したため、首都でも明瞭に受信可能となった。このラジオ放送は国内に動乱を引き起こしたことで、クーデター成功の要因として歴史家から高く評価されてい る。政府系ラジオ局が新アンテナ設置のため3週間放送を停止したことも、予想外の追い風となった[127]。「解放の声」は紛争中も放送を継続し、反乱軍 が首都に集結しているという誇張された情報を流した。これにより軍と民間人の双方に深刻な士気低下をもたらした[128]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1954_Guatemalan_coup_d%27%C3%A9tat |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆