民話の形態学

Morphology of the

Folktale, 1928, by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp

☆ウ

ラジーミル・ヤコヴレヴィチ・プロップ(ロシア語: Владимир Яковлевич Пропп;1895年4月29日[旧暦4月17日] -

1970年8月22日)は、ソビエトの民俗学者であり、ロシア民話の基礎的な構造要素を分析し、その最も単純で還元不可能な構造単位を特定した学者であ

る。

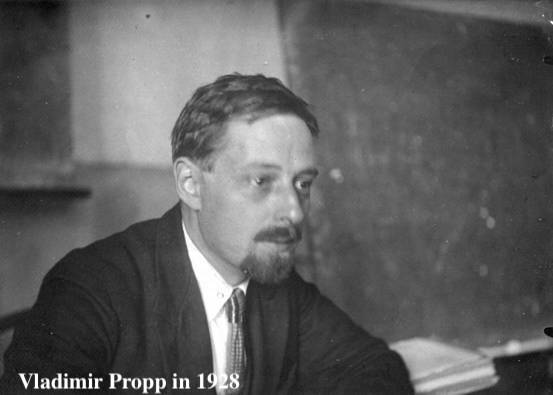

| Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp

(Russian: Владимир Яковлевич Пропп; 29 April [O.S. 17 April] 1895 – 22

August 1970) was a Soviet folklorist and scholar who analysed the basic

structural elements of Russian folk tales to identify their simplest,

irreducible structural units. |

ウ

ラジーミル・ヤコヴレヴィチ・プロップ(ロシア語: Владимир Яковлевич Пропп;1895年4月29日[旧暦4月17日] -

1970年8月22日)は、ソビエトの民俗学者であり、ロシア民話の基礎的な構造要素を分析し、その最も単純で還元不可能な構造単位を特定した学者であ

る。 |

Biography Vladimir Propp was born on 29 April 1895 in Saint Petersburg to an assimilated Russian family of German descent. His parents, Yakov Philippovich Propp and Anna-Elizaveta Fridrikhovna Propp (née Beisel), were Volga German wealthy peasants from Saratov Governorate. He attended Saint Petersburg University (1913–1918), majoring in Russian and German philology.[1] Upon graduation he taught Russian and German at a secondary school and then became a college teacher of German. His Morphology of the Folktale was published in Russian in 1928. Although it represented a breakthrough in both folkloristics and morphology and influenced Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roland Barthes, it was generally unnoticed in the West until it was translated in 1958. His morphology is used in media education and has been applied to narrative in literature, theatre, film, television series, and games; however, Propp applied it specifically to the wonder tale (or fairy tale). In 1932, Propp became a member of Leningrad University (formerly St. Petersburg University) faculty. After 1938, he chaired the Department of Folklore until it became part of the Department of Russian Literature. Propp remained a faculty member until his death in 1970.[1] |

伝記 ウラジーミル・プロップは1895年4月29日、サンクトペテルブルクでドイツ系ロシア人の同化家族に生まれた。両親のヤコフ・フィリポヴィチ・プロップ とアンナ=エリザヴェータ・フリドリホヴナ・プロップ(旧姓バイゼル)は、サラートフ県出身のヴォルガ・ドイツ人富裕農民であった。彼はサンクトペテルブ ルク大学(1913年~1918年)でロシア語学とドイツ語学を専攻した[1]。卒業後は中等学校でロシア語とドイツ語を教えた後、大学でドイツ語の講師 となった。 彼の『民話の形態論』は1928年にロシア語で出版された。この著作は民俗学と形態論の両分野で画期的であり、クロード・レヴィ=ストロースやロラン・バ ルトに影響を与えたが、1958年に翻訳されるまで西洋ではほとんど注目されなかった。彼の形態論はメディア教育で用いられ、文学・演劇・映画・テレビシ リーズ・ゲームなどの物語構造に応用されている。ただしプロップ自身が適用したのは特に「不思議物語」(または童話)であった。 1932年、プロップはレニングラード大学(旧サンクトペテルブルク大学)の教員となった。1938年以降は民俗学部門の責任者を務め、同部門がロシア文学部門に統合されるまでその職にあった。プロップは1970年に死去するまで教員として在籍した。 |

| Works In Russian His main books are: Morphology of the Folktale (Leningrad 1928) Historical Roots of the Wonder Tale (Leningrad 1946) Russian Epic Song (Leningrad 1955–1958) Popular Lyric Songs (Leningrad 1961) Russian Agrarian Feasts (Leningrad 1963) He also published some articles, the most important are: "The Magical Tree on the Tomb" "Wonderful Childbirth" "Ritual Laughter in Folklore" "Oedipus in the Light of Folklore" First printed in specialized reviews, they were republished in Folklore and Reality (Leningrad 1976). Two books were published posthumously: Problems of Comedy and Laughter (Leningrad 1983) The Russian Folktale (Leningrad 1984) The first book remained unfinished; the second one is the edition of the course he gave in Leningrad University. Translations into English and other languages Morphology of the Folktale was translated into English in 1958 and 1968. It was also translated into Italian and Polish in 1966, French and Romanian in 1970, Spanish in 1971, German in 1972, Hungarian in 1975, and Serbian in 1982. Historical Roots of the Wonder Tale was translated into Italian in 1949 and 1972, Spanish in 1974, and French, Romanian and Japanese in 1983. It was translated into English in 2025, nearly seven decades after the translation of Morphology of the Folktale.[2] Oedipus in the light of folklore was translated into Italian in 1975. Russian Agrarian Feasts was translated into French in 1987. |

著作 ロシア語で 主な著作は以下の通りである: 民話の形態論(レニングラード 1928年) 不思議物語の歴史的根源(レニングラード 1946年) ロシア叙事歌(レニングラード 1955–1958年) 民衆的抒情歌(レニングラード 1961年) ロシアの農耕祭 (レニングラード 1963年) またいくつかの論文を発表しており、最も重要なものは以下の通りである: 「墓の上の呪術的の木」 「不思議な出産」 「民俗学における儀礼的笑い」 「民俗学の視点から見たオイディプス」 これらは専門誌に初掲載され、後に『民俗学と現実』(レニングラード 1976年)に再収録された。 死後出版された著作は二冊ある: 『喜劇と笑いの問題』(レニングラード 1983年) 『ロシア民話』(レニングラード 1984年) 前者は未完のまま残され、後者はレニングラード大学で彼が担当した講義の編集版である。 英語及び他言語への翻訳 『民話の形態論』は1958年と1968年に英語へ翻訳された。また1966年にはイタリア語とポーランド語へ、1970年にはフランス語とルーマニア語 へ、1971年にはスペイン語へ、1972年にはドイツ語へ、1975年にはハンガリー語へ、1982年にはセルビア語へ翻訳されている。 『不思議物語の歴史的根源』は1949 年と1972年にイタリア語へ、1974年にスペイン語へ、1983年にはフランス語・ルーマニア語・日本語へ翻訳された。英語版は『民話形態論』の翻訳からほぼ70年後の2025年に翻訳された。[2] 『民俗学の視点から見たオイディプス』は1975年にイタリア語に翻訳された。 『ロシアの農耕祭』は1987年にフランス語に翻訳された。 |

| Narrative structure According to Propp, based on his analysis of 100 folktales from the corpus of Alexander Fyodorovich Afanasyev, there are 31 basic structural elements (or "functions") that typically occur within Russian fairy tales. He identifies these 31 functions as typical of all fairy tales, or wonder tales (skazka), in Russian folklore. These functions occur in a specific, ascending order (1-31, although not inclusive of all functions within any tale) within each story. This type of structural analysis of folklore is referred to as "syntagmatic". This focus on the events of a story and the order in which they occur is in contrast to another form of analysis, the "paradigmatic" which is more typical of Lévi-Strauss's structuralist theory of mythology. Lévi-Strauss sought to uncover a narrative's underlying pattern, regardless of the linear, superficial syntagm, and his structure is usually rendered as a binary oppositional structure. For paradigmatic analysis, the syntagm, or the linear structural arrangement of narratives, is irrelevant to their underlying meaning. |

物語の構造 プロップによれば、アレクサンダー・フョードロヴィチ・アファナシエフの民話集100編の分析に基づき、ロシアの童話には31の基本的な構造要素(または 「機能」)が典型的に見られるという。彼は、この31の機能を、ロシアの民間伝承におけるすべての童話、すなわち不思議物語(スカズカ)に典型的なものと 見なしている。これらの機能は、各物語の中で特定の昇順(1~31、ただし、どの物語にもすべての機能が含まれているわけではない)で現れる。この種の民 俗学の構造分析は、「統語的」と呼ばれる。物語の出来事とその発生順序に焦点を当てるこの手法は、別の分析手法である「パラダイム的」手法とは対照的であ る。パラダイム的分析は、レヴィ=ストロースの構造主義的神話理論でより典型的に見られる。レヴィ=ストロースは、線形的・表層的なシントグラム(叙述の 連鎖)に関わらず、物語の根底にあるパターンを解明しようとした。彼の構造は通常、二項対立構造として表現される。パラダイム分析においては、シントグラ ム、すなわち物語の線形的構造配置は、その根底にある意味とは無関係である。 |

| Functions After the initial situation is depicted, any wonder tale will be composed of a selection of the following 31 functions, in a fixed, consecutive order:[3] 1. Absentation – A member of the hero's community or family leaves the security of the home environment. This may be the hero himself, or some other relation that the hero must later rescue. This division of the cohesive family injects initial tension into the storyline. This may serve as the hero's introduction, typically portraying him as an ordinary person. 2. Interdiction – A forbidding edict or command is passed upon the hero ('don't go there', 'don't do this'). The hero is warned against some action. 3. Violation of interdiction – The prior rule is violated. Therefore, the hero did not listen to the command or forbidding edict. Whether committed by the Hero by accident or temper, a third party or a foe, this generally leads to negative consequences. The villain enters the story via this event, although not necessarily confronting the hero. They may be a lurking and manipulative presence, or might act against the hero's family in his absence. 4. Reconnaissance – The villain makes an effort to attain knowledge needed to fulfil his plot. Disguises are often invoked as the villain actively probes for information, perhaps for a valuable item or to abduct someone. He may speak with a family member who innocently divulges a crucial insight. The villain may also seek out the hero in his reconnaissance, perhaps to gauge his strengths in response to learning of his special nature. 5. Delivery – The villain succeeds at recon and gains a lead on his intended victim. A map is often involved in some level of the event. 6. Trickery – The villain attempts to deceive the victim to acquire something valuable. He presses further, aiming to con the protagonists and earn their trust. Sometimes the villain makes little or no deception and instead ransoms one valuable thing for another. 7. Complicity – The victim is fooled or forced to concede and unwittingly or unwillingly helps the villain, who is now free to access somewhere previously off-limits, like the privacy of the hero's home or a treasure vault, acting without restraint in his ploy. 8. Villainy or lacking – The villain harms a family member, including but not limited to abduction, theft, spoiling crops, plundering, banishment or expulsion of one or more protagonists, murder, threatening a forced marriage, inflicting nightly torments and so on. Simultaneously or alternatively, a protagonist finds they desire or require something lacking from the home environment (potion, artifact, etc.). The villain may still be indirectly involved, perhaps fooling the family member into believing they need such an item. 9. Mediation – One or more of the negative factors covered above comes to the attention of the Hero, who uncovers the deceit/perceives the lacking/learns of the villainous acts that have transpired. 10. Beginning counteraction – The hero considers ways to resolve the issues, by seeking a needed magical item, rescuing those who are captured or otherwise thwarting the villain. This is a defining moment for the hero; one that shapes his future actions and marks the point when he begins to fit his noble mantle. |

機能 初期状況が描かれた後、あらゆる不思議物語は次の31の機能から選択され、固定された連続した順序で構成される[3]: 1. 離脱 – 英雄の共同体や家族の一員が、安全な家庭環境を離れる。これは英雄自身である場合もあれば、後に英雄が救出しなければならない他の関係者の場合もある。結 束した家族の分裂は、物語に初期の緊張をもたらす。これは通常、主人公を平凡な人格として描く導入部として機能する。 2. 禁令違反 – 主人公に対して「そこへ行くな」「これをやるな」といった禁制の命令が下される。主人公は特定の行動を警告される。 3. 禁令違反 – 先の規則が破られる。つまり英雄は命令や禁令に従わなかった。英雄の過失か短気か、第三者か敵かに関わらず、これは概して悪い結果を招く。この出来事を契 機に悪役が登場するが、必ずしも英雄と対峙するわけではない。潜伏し操る存在として、あるいは英雄不在時に家族を攻撃する形で現れることもある。 4. 偵察活動 – 悪役は計画遂行に必要な情報を得るため行動する。変装を駆使し、貴重品や拉致対象を探る。家族が知らずに重要情報を漏らすこともある。悪役は偵察中に主人公を探し出し、その特殊性を知った上で実力を測ろうとする場合もある。 5. 情報入手 – 悪役は偵察に成功し、標的にする被害者の手がかりを得る。この過程では地図が関与することが多い。 6. 欺瞞 – 悪役は貴重な物を手に入れるため、被害者を騙そうとする。さらに踏み込み、主人公たちを騙して信頼を得ようとする。時には悪役はほとんど騙さず、代わりに一つの貴重な物を別の物と交換する。 7. 共犯 – 被害者は騙されたり強制されたりして、知らず知らずのうちに、あるいは不本意ながら悪党を助ける。悪党はこれで、英雄の自宅のプライバシーや宝物庫など、以前は立ち入り禁止だった場所に自由にアクセスできるようになり、策略を制限なく実行する。 8. 悪行または欠如 – 悪役は家族成員に危害を加える。誘拐、窃盗、作物の破壊、略奪、主人公の追放、殺害、強制結婚の脅迫、夜間の苦痛の与えなどが含まれるが、これらに限定さ れない。同時に、あるいは代わりに、主人公は家庭環境で不足している何か(薬、アーティファクトなど)を欲したり必要としたりする。悪役は間接的に関与し ている場合もあり、例えば家族を騙してその品が必要だと信じ込ませることもある。 9. 仲介 – 上記の負の要素の一つ以上が英雄の知るところとなり、英雄は欺瞞を見破る/不足を感知する/発生した悪役の行為を知る。 10. 反撃の始まり – 主人公は問題を解決する方法を考える。必要な呪術的な品を探す、捕らえられた者を救出する、あるいは悪役を阻止するといった手段だ。これは主人公にとって 決定的な瞬間である。彼の今後の行動を形作り、高貴な使命にふさわしい存在へと変貌する起点となる。 |

| 11. Departure – The hero leaves the home environment, this time with a sense of purpose. Here his adventure begins. 12. First function of the donor – The hero encounters a magical agent or helper (donor) on his path, and is tested in some manner through interrogation, combat, puzzles or more. 13. Hero's reaction – The hero responds to the actions of his future donor; perhaps withstanding the rigours of a test and/or failing in some manner, freeing a captive, reconciles disputing parties or otherwise performing good services. This may also be the first time the hero comes to understand the villain's skills and powers, and uses them for good. 14. Receipt of a magical agent – The hero acquires use of a magical agent as a consequence of his good actions. This may be a directly acquired item, something located after navigating a tough environment, a good purchased or bartered with a hard-earned resource or fashioned from parts and ingredients prepared by the hero, spontaneously summoned from another world, a magical food that is consumed, or even the earned loyalty and aid of another. 15. Guidance – The hero is transferred, delivered or somehow led to a vital location, perhaps related to one of the above functions such as the home of the donor or the location of the magical agent or its parts, or to the villain. 16. Struggle – The hero and villain meet and engage in conflict directly, either in battle or some nature of contest. 17. Branding – The hero is marked in some manner, perhaps receiving a distinctive scar or granted a cosmetic item like a ring or scarf. 18. Victory – The villain is defeated by the hero – killed in combat, outperformed in a contest, struck when vulnerable, banished, and so on. 19. Liquidation – The earlier misfortunes or issues of the story are resolved; objects of search are distributed, spells broken, captives freed. 20. Return – The hero travels back to his home. |

11. 出発 – 主人公は目的意識を持って故郷を離れる。ここで彼の冒険が始まる。 12. 支援者の最初の役割 – 主人公は道中で呪術的使者や助っ人(支援者)と出会い、尋問や戦闘、謎解きなどで試される。 13. 英雄の反応 – 英雄は将来のドナーの行動に応じる。試練に耐える、あるいは何らかの形で失敗する、捕らわれた者を解放する、争う者たちを和解させる、その他の善行を行うなどだ。これは同時に、英雄が悪役の技量や力を初めて理解し、それを善用する瞬間でもある。 14. 呪術的な道具の入手 – 英雄は善行の結果として呪術的な道具を手に入れる。直接入手した品、困難な環境を乗り越えて発見したもの、苦労して得た資源と交換した品、英雄が準備した 部品や材料から製作したもの、異世界から突然召喚されたもの、摂取する魔法の食物、あるいは他者の忠誠や支援といった形でも得られる。 15. 導き – 英雄は重要な場所へ移送され、運ばれ、あるいは何らかの形で導かれる。それは上記の機能(提供者の住処、呪術的道具やその部品の所在、あるいは悪役自身など)に関連する場所である可能性がある。 16. 闘争 – 英雄と悪役が直接対峙し、戦闘あるいは何らかの勝負で衝突する。 17. 刻印 – 英雄は何らかの形で印を刻まれる。特徴的な傷を負うか、指輪やスカーフのような装飾品を授かる。 18. 勝利 – 悪役は英雄によって打ち負かされる。戦闘で倒される、勝負で敗れる、弱点を突かれる、追放されるなど。 19. 決着 – 物語の初期の不幸や問題は解決される。探していた物は分配され、呪いは解け、捕虜は解放される。 20. 帰還 – 主人公は故郷へと戻る。 |

| 21. Pursuit – The hero is pursued by some threatening adversary, who perhaps seek to capture or eat him. 22. Rescue – The hero is saved from a chase. Something may act as an obstacle to delay the pursuer, or the hero may find or be shown a way to hide, up to and including transformation unrecognisably. The hero's life may be saved by another. 23. Unrecognized arrival – The hero arrives, whether in a location along his journey or in his destination, and is unrecognised or unacknowledged. 24. Unfounded claims – A false hero presents unfounded claims or performs some other form of deceit. This may be the villain, one of the villain's underlings or an unrelated party. It may even be some form of future donor for the hero, once they've faced his actions. 25. Difficult task – A trial is proposed to the hero – riddles, test of strength or endurance, acrobatics and other ordeals. 26. Solution – The hero accomplishes a difficult task. 27. Recognition – The hero is given due recognition – usually by means of his prior branding. 28. Exposure – The false hero and/or villain is exposed to all and sundry. 29. Transfiguration – The hero gains a new appearance. This may reflect aging and/or the benefits of labour and health, or it may constitute a magical remembering after a limb or digit was lost (as a part of the branding or from failing a trial). Regardless, it serves to improve his looks. 30. Punishment – The villain suffers the consequences of his actions, perhaps at the hands of the hero, the avenged victims, or as a direct result of his own ploy. 31. Wedding – The hero marries and is rewarded or promoted by the family or community, typically ascending to a throne. |

21. 追跡 – 英雄は脅威的な敵に追われる。敵は英雄を捕らえたり食らおうとするかもしれない。 22. 救出 – 英雄は追跡から救われる。何かが障害となって追跡者を遅らせたり、英雄が隠れ場所を見つけたり示されたりする。変身して見分けがつかなくなる場合もある。英雄の命は他者によって救われることもある。 23. 気づかれない到着 – 英雄は旅の途中の場所か目的地に着くが、気づかれず、認められない。 24. 根拠のない主張 – 偽りの英雄が根拠のない主張をしたり、他の形の欺瞞を行ったりする。これは悪役、悪役の部下、あるいは無関係な者かもしれない。あるいは、英雄の行動に直面した後の、何らかの形で英雄を支援する者である可能性もある。 25. 困難な試練 – 英雄に試練が課される。謎解き、体力や忍耐力の試練、曲芸、その他の過酷な試練である。 26. 解決 – 英雄は困難な試練を成し遂げる。 27. 認識 – 英雄は正当な評価を得る。通常は、以前の烙印によって認識される。 28. 暴露 – 偽りの英雄や悪役が、あらゆる者たちの前で暴露される。 29. 変容 – 英雄は新たな外見を得る。これは加齢や労働・健康の恩恵を反映している場合もあれば、手足や指を失った後の呪術的な再生(烙印の一部として、あるいは試練に失敗した結果)である場合もある。いずれにせよ、その容姿を向上させる役割を果たす。 30. 罰 – 悪役は自らの行いの報いとして苦悩する。それは英雄や復讐を果たした被害者によるものか、あるいは自身の策略が直接招いた結果である。 31. 婚礼 – 英雄は結婚し、家族や共同体から報いを受け、あるいは昇進する。典型的には王座に就く。 |

| Some

of these functions may be inverted, such as the hero receives an

artifact of power whilst still at home, thus fulfilling the donor

function early. Typically such functions are negated twice, so that it

must be repeated three times in Western cultures.[4] |

これらの機能の一部は逆転する場合がある。例えば、主人公がまだ故郷にいる間に力のアーティファクトを受け取ることで、与える機能を早期に果たす場合だ。通常、こうした機能は二度否定されるため、西洋文化では三度繰り返さねばならない。[4] |

| Characters Main article: Actant Propp also concludes that all the characters in tales can be resolved into seven abstract character functions: 1. The villain – an evil character that creates struggles for the hero. 2. The dispatcher – any character who illustrates the need for the hero's quest and sends the hero off. This often overlaps with the princess's father. 3. The helper – a typically magical entity that comes to help the hero in their quest. 4. The princess or prize, and often her father – the hero deserves her throughout the story but is unable to marry her as a consequence of some evil or injustice, perhaps the work of the villain. The hero's journey is often ended when he marries the princess, which constitutes the villain's defeat. 5. The donor – a character that prepares the hero or gives the hero some magical object, sometimes after testing them. 6. The hero – the character who reacts to the dispatcher and donor characters, thwarts the villain, resolves any lacking or wronghoods and weds the princess. 7. The false hero – a Miles Gloriosus figure who takes credit for the hero's actions or tries to marry the princess.[5] These roles can sometimes be distributed among various characters, as the hero kills the villain dragon, and the dragon's sisters take on the villainous role of chasing him. Conversely, one character can engage in acts as more than one role, as a father can send his son on the quest and give him a sword, acting as both dispatcher and donor.[6] |

登場人物 詳細記事: アクタント プロップはまた、物語の登場人物はすべて七つの抽象的な役割に分類できると結論づけている: 1. 悪役 – 主人公に困難をもたらす邪悪な存在。 2. 派遣者 – 主人公の冒険の必要性を示し、送り出す人物。王女(姫)の父親と重なることが多い。 3. 助言者 – 英雄の冒険を助けるために現れる、通常は呪術的な存在。 4. 王女または報酬、そしてしばしばその父 – 英雄は物語を通じて彼女にふさわしいが、悪や不正(おそらく悪役の仕業)の結果として彼女と結婚できない。英雄の旅は王女との結婚で終わる場合が多く、これが悪役の敗北を意味する。 5. 供与者 – 英雄を準備させたり、呪術的な品を与える人物。時に英雄を試した後に行動する。 6. 英雄 – 派遣者と供与者の行動に応じ、悪役を打ち倒し、欠如や不正を解決し、姫と結婚する人物。 7. 偽りの英雄 – 英雄の功績を横取りしたり、姫との結婚を企てる、虚栄心の強い人物。[5] これらの役割は複数のキャラクターに分散されることもある。例えば英雄が竜という悪役を倒し、その竜の姉妹たちが英雄を追う悪役を担う場合だ。逆に、一つ のキャラクターが複数の役割を兼ねることがある。父親が息子を冒険に送り出し、剣を与える場合、派遣者と提供者の両方の役割を果たすことになる。[6] |

| Criticism Propp's approach has been criticized for its excessive formalism (a major critique of the Soviets). One of the most prominent critics of Propp was structuralist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who, in dialogue with Propp, argued for the superiority of the paradigmatic over syntagmatic approach.[7] Propp responded to this criticism in a sharply-worded rebuttal: he wrote that Lévi-Strauss showed no interest in empirical investigation.[8] |

批判 プロップのアプローチは、その過度な形式主義(ソビエトに対する主要な批判点)を理由に批判されてきた。プロップに対する最も著名な批判者の一人は構造主 義者のクロード・レヴィ=ストロースであった。彼はプロップとの対話の中で、連鎖的アプローチよりも範疇的アプローチの優位性を主張した[7]。プロップ はこの批判に対して鋭い反論で応じた。彼はレヴィ=ストロースが実証的研究に全く関心を示していないと書いた[8]。 |

| Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index Joseph Campbell(The Hero with a Thousand Faces)  |

アーネ・トンプソン・ウザー・インデックス(下で説明) ジョセフ・キャンベル『千の顔を持つ英雄』(The Hero with a Thousand Faces)  |

| References 1. Propp, Vladimir. "Introduction." Theory and History of Folklore. Ed. Anatoly Liberman. University of Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1984. pg ix 2. Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp, Historical Roots of the Wondertale, translated by Miriam Shrager, Sibelan Forrester and Russell Scott Valentino, ISBN 978-0253074027 3. Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p. 25, ISBN 0-292-78376-0 4. Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p. 74, ISBN 0-292-78376-0 5. Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p 79-80, ISBN 0-292-78376-0 6. Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p 81, ISBN 0-292-78376-0 7. Dundes, Alan. "Binary Opposition in Myth: The Propp/Levi-Strauss Debate in Retrospect", Western Folklore, 56.1 (Winter 1997) 8. Vladimir Propp, Theory and History of Folklore (Theory and History of Literature #5) by Vladimir Propp, Ariadna Y. Martin (Translator), Richard P. Martin (Translator), Anatoly Liberman |

参考文献 1. プロップ, ウラジーミル. 「序論」. 『民俗学の理論と歴史』. アナトリー・リベルマン編. ミネソタ大学: ミネソタ大学出版局, 1984. ix頁 2. ウラジーミル・ヤコヴレヴィチ・プロップ, 『不思議物語の歴史的根源』, ミリアム・シュレイガー, シベラン・フォレスター, ラッセル・スコット・ヴァレンティーノ訳, ISBN 978-0253074027 3. ウラジーミル・プロップ『民話形態論』p. 25, ISBN 0-292-78376-0 4. ウラジーミル・プロップ『民話形態論』p. 74, ISBN 0-292-78376-0 5. ウラジーミル・プロップ『民話形態論』p 79-80, ISBN 0-292-78376-0 6. ウラジーミル・プロップ『民話形態論』81ページ、ISBN 0-292-78376-0 7. アラン・ダンデス「神話における二項対立:プロップとレヴィ=ストロースの論争を振り返って」『西部民俗学』56.1 (1997年冬号) 8. ウラジーミル・プロップ著、アリアドナ・Y・マーティン(翻訳)、リチャード・P・マーティン(翻訳)、アナトリー・リバマンによる『民俗学の理論と歴史(文学の理論と歴史 #5)』 |

| External links "The Functions of the Dramatis Personae" by Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, 1927, translated by Laurence Scott, 1968 "Vladimir Propp" - Jerry Everard, February 12, 2007, Mindsigh "The Birth of Structuralism from the Analysis of Fairy-Tales" – Dmitry Olshansky / Toronto Slavic Quarterly, No. 25, University of Toronto "proppian fairy tale generator", "fairy tales and electronic culture", Brown courses "vladimir propp's theories", "fairy tales and electronic culture", Brown courses "Vladimir Propp", The Literary Encyclopedia (2008) Assessment of Propp (in German) A Folktale Outline Generator: based on Propp's Morphology The Historical Roots of the Wonder Tale Propp's examination of the origin of specific folktale motifs in customs and beliefs, initiation rites. (in Russian) Linguistic Formalists by C. John Holcombe An interesting essay through the story of Russian Formalism. Biography of Vladimir Propp Archived 2017-08-09 at the Wayback Machine at the Gallery of Russian Thinkers An XML Markup language based on Propp at the University of Pittsburgh |

外部リンク 「登場人物の機能」プロップ著、『民話形態論』1927年、ローレンス・スコット訳、1968年 「ウラジーミル・プロップ」 - ジェリー・エヴァラード、2007年2月12日、マインドサイグ 「童話分析から生まれた構造主義」-ドミトリー・オルシャンスキー/トロント大学スラブ季刊誌第25号 「プロップ式童話生成器」「童話と電子文化」、ブラウン大学講座 「ウラジーミル・プロップの理論」「童話と電子文化」、ブラウン大学講座 「ウラジーミル・プロップ」、文学百科事典 (2008) プロップの評価(ドイツ語) 民話概要生成器:プロップの形態論に基づく 不思議物語の歴史的根源 プロップによる特定の民話モチーフの起源の考察(習慣・信仰・通過儀礼における)。(ロシア語) C.ジョン・ホルコムによる言語形式主義者 ロシア形式主義の歴史を通した興味深い論考。 ウラジーミル・プロップの伝記(ロシア思想家ギャラリーにて2017年8月9日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ) ピッツバーグ大学におけるプロップに基づくXMLマークアップ言語 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_Propp |

☆Stith Thompson, 1885-1976

| Stith Thompson

(March 7, 1885 – January 10, 1976)[1] was an American folklorist: he

has been described as "America's most important folklorist".[2] He is the "Thompson" of the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index, which indexes folktales by type, and the author of the Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, a resource for folklorists that indexes motifs, granular elements of folklore. |

スティス・トンプソン(1885年3月7日 - 1976年1月10日)[1]はアメリカの民俗学者である。彼は「アメリカで最も重要な民俗学者」と評されている。[2] 彼は、民話を類型別に索引化したアーネ=トンプソン=ウザー分類法の「トンプソン」であり、民俗学者向けの資料である『民俗文学モチーフ索引』の著者でもある。この索引は、民俗学の微細な要素であるモチーフを索引化したものである。 |

| Biography Early life Stith Thompson was born in Bloomfield, Nelson County, Kentucky, on March 7, 1885, the son of John Warden and Eliza (McClaskey). Thompson moved with his family to Indianapolis at the age of twelve and attended Butler University from 1903 to 1905 before he obtained his BA degree from University of Wisconsin in 1909 (his undergraduate thesis was titled, 'The Return from the Dead in Popular Tales and Ballads').[3] For the next two years he taught at Lincoln High School in Portland, Oregon, during which time he learned Norwegian from lumberjacks. He earned his master's degree in English literature from the University of California, Berkeley in 1912, where his dissertation was titled "The Idea of the Soul in Teutonic Popular Tales and Ballads".[3] |

伝記 幼少期 スティス・トンプソンは1885年3月7日、ケンタッキー州ネルソン郡ブルームフィールドで、ジョン・ウォーデンとエリザ(旧姓マクラスキー)の息子とし て生まれた。12歳の時に家族と共にインディアナポリスへ移住し、1903年から1905年までバトラー大学に通った後、1909年にウィスコンシン大学 で学士号を取得した(卒業論文の題名は『民話とバラッドにおける死からの帰還』であった)。その後2年間、オレゴン州ポートランドのリンカーン高校で教鞭 を執り、その間に林業労働者からノルウェー語を学んだ。1912年にはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校で英文学の修士号を取得し、修士論文の題名は「ゲル マン民話とバラッドにおける魂の概念」であった。 |

| Graduate education He studied at Harvard University from 1912 to 1914 under George Lyman Kittredge, writing the dissertation "European Borrowings and Parallels in North American Indian Tales," and earning his Ph.D. (The revised thesis was later published in 1919).[4][5] This grew out of Kittredge's assignment, whose theme was investigating a certain tale called "The Blue Band",[a] collected from the Chipewyan tribe in Saskatchewan may derive from contact with an analogous Scandinavian tale.[6][7] Post-graduate Thompson was an English instructor at the University of Texas, Austin from 1914 to 1918, teaching composition.[8] |

大学院教育 彼は1912年から1914年までハーバード大学でジョージ・ライマン・キットリッジに師事し、「北米インディアン物語におけるヨーロッパからの借用と類 似点」という論文を執筆して博士号を取得した(改訂版は後に1919年に出版された)。[4][5] これはキットリッジの課題から発展したもので、そのテーマは「青い帯」と呼ばれる特定の物語[a]を調査することだった。この物語はサスカチュワン州のチ ペワヤン族から収集されたもので、類似したスカンジナビアの物語との接触に由来する可能性がある。[6][7] 大学院卒業後 トンプソンは1914年から1918年までテキサス大学オースティン校で英文学講師を務め、作文を教えた。[8] |

| Indiana University In 1921, Thompson was appointed associate professor at the English Department of the Indiana University Bloomington, which also had the responsibility of overseeing its composition program.[4] Within a year he began offering courses in folklore: these were among the first courses in the field taught in the United States.[2] His commitment to the promotion of academic research in folklore resulted in the creation of the PhD program in folklore at Indiana in 1949 - the first of its kind in the United States. The first doctorate was awarded (to Warren E. Roberts) in 1953.[2][9] For this - along with the establishment of folklore courses elsewhere in US academia by his former students - Thompson has been claimed to have been "largely responsible for establishing folklore on a firm academic footing in the United States".[2] He organized an informal quadrennial summertime "Institute of Folklore" beginning in 1942 which lasted beyond his retirement from tenure in 1955. This brought together scholars with an interest in the field of folklore and helped to bring structure to the growing discipline.[10] In 1962, a permanent Institute of Folklore was established at Bloomington, with Richard Dorson serving as its administrator and chief editor of its journal publication. |

インディアナ大学 1921年、トンプソンはインディアナ大学ブルーミントン校の英文学科の准教授に任命された。この職には同大学の作文プログラムの監督責任も含まれてい た。[4] 1年以内に、彼は民俗学の講座を開講し始めた。これは、米国で教えられたこの分野における最初の講座の一つであった。[2] 民俗学における学術研究の推進に対する彼の取り組みは、1949 年にインディアナ大学で民俗学の博士課程が創設される結果となった。これは、米国で初めての試みであった。最初の博士号は、1953年に(ウォーレン・ E・ロバーツに)授与された。[2] [9] この功績と、彼の教え子たちが米国の他の大学でも民俗学の講座を開設したことにより、トンプソンは「米国で民俗学を確固たる学術的基盤の上に確立した大き な責任者」であると評されている。[2] 彼は1942年から4年ごとに非公式の夏季「民俗学研究所」を組織し、1955年に終身在職権を退いた後もこれを継続した。これにより、民俗学の分野に関 心を持つ学者たちが集まり、成長しつつあるこの学問分野に構造をもたらす一助となった。[10] 1962年、ブルーミントンに恒久的な民俗学研究所が設立され、リチャード・ドーソンがその管理者および学術誌の編集長を務めた。 |

| Research and influence While Thompson wrote, co-wrote, or translated numerous books and articles on folklore, he became arguably best known for his work on the classification of motifs in folk tales. His six-volume Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (1955–1958) is considered the international key to traditional material. In the 1920s, Thompson began collecting and archiving traditional ballads, tales, proverbs, aphorisms, riddles, etc. At around this time, the study of the parallels and worldwide distributions of folktales were being studied in new ways by European scholars (particularly Antti Aarne in Finland). Thompson had developed an understanding of these new techniques through travel and research and published an expanded translation of Aarne's The Types of the Folktale in 1928, creating a catalogue of folktale types, that included tales from Europe and Asia.[3] Thompson used this classification in his Tales of the North American Indians published in 1929.[3] Building upon this, Thompson published his "landmark work" The Motif-Index of Folk-Literature in six volumes between 1932 and 1936.[3] The Motif-Index organised thousands of motifs drawn from the folktale types he had catalogued in The Types of the Folktale. By introducing these techniques to American folklorists, Thompson has been described as having a "marked influence on the direction of American folklore scholarship in the 20th century".[2] For nearly twenty years after his retirement, Thompson continued to work on his Motif-Index and The Types of the Folktale - he published revised editions of the volumes of the Motif-Index between 1955 and 1958.[6] During this Thompson also collaborated on projects with other folklorists such as Jonah Balys' The Oral Tales of India and Warren Roberts' Types of Indic Folktales. He even produced an anthology at the age of 83, One Hundred Favorite Folktales.[10] |

研究と影響 トンプソンは民俗学に関する数多くの書籍や論文を執筆、共著、翻訳したが、おそらく最も知られているのは民話におけるモチーフの分類に関する研究である。彼の六巻からなる『民話文学モチーフ索引』(1955-1958年)は、伝統的素材の国際的な鍵と見なされている。 1920年代、トンプソンは伝統的なバラッド、物語、諺、格言、なぞなぞなどの収集とアーカイブを開始した。この頃、ヨーロッパの学者(特にフィンランド のアンティ・アーネ)によって、民話の類似性と世界的な分布の研究が新たな手法で進められていた。トンプソンは旅行と研究を通じてこれらの新手法を理解 し、1928年にアーネの『民話の類型』の増補訳を出版。欧州とアジアの物語を含む民話類型目録を作成した[3]。トンプソンはこの分類法を1929年刊 行の『北米インディアンの物語』で用いた。[3] これを基盤として、トンプソンは1932年から1936年にかけて全6巻からなる「画期的な著作」『民俗文学モチーフ索引』を刊行した[3]。『モチーフ索引』は、彼が『民話類型論』で体系化した民話類型から抽出した数千のモチーフを整理したものである。 トンプソンは、こうした手法をアメリカの民俗学者たちに紹介したことで、「20 世紀のアメリカの民俗学研究の方向性に顕著な影響を与えた」と評されている。[2] トンプソンは、引退後も 20 年近く、「モチーフ・インデックス」と「民話の類型」の研究を続け、1955 年から 1958 年にかけて、「モチーフ・インデックス」の改訂版を出版した。[6] この間、トンプソンは、ジョナ・バリス著『The Oral Tales of India』やウォーレン・ロバーツ著『Types of Indic Folktales』など、他の民俗学者たちとの共同プロジェクトにも協力した。83歳の時には、アンソロジー『One Hundred Favorite Folktales』を出版している。[10] |

| Later years In 1976, Thompson died of heart failure at his home in Columbus, Indiana.[11] |

晩年 1976年、トンプソンはインディアナ州コロンバスの自宅で心不全により死亡した。[11] |

| Recognition Thompson served as President of the American Folklore Society between 1937 and 1939 and was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1947.[12][3] He received a number of Honorary Degrees from universities including University of North Carolina (1946), Indiana Central College (1953) and University of Kentucky (1958).[3] |

表彰 トンプソンは1937年から1939年までアメリカ民俗学会の会長を務め、1947年にはアメリカ哲学会会員に選出された。[12] [3] 彼はノースカロライナ大学(1946年)、インディアナ・セントラル大学(1953年)、ケンタッキー大学(1958年)などから数多くの名誉学位を授与された。[3] |

| Selected publications Thompson, Stith (1919). European tales among the North American Indians : a study in the migration of folk-tales. Colorado Springs, Colorado: Board of Trustees of Colorado College. OCLC 30703248. Aarne, Antti; Thompson, Stith (1928). The types of the folk-tale : a classification and bibliography. Helsinki: Suomalainen tiedeakatemia. OCLC 604047970. Thompson, Stith (1929). Tales of the North American Indians,. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. OCLC 1295733602. Thompson, Stith (1955). Motif index of folk-literature : a classification of narrative elements in folktales, ballads, myths ... rev. and enlarged ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. OCLC 301495255. Thompson, Stith (1946). The folktale. OCLC 1156806364. Thompson, Stith (1953). Four symposia on folklore. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. OCLC 706445956. Thompson, Stith (1968). One hundred favorite folktales. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. OCLC 836339166. Thompson, Stith; McDowell, John Holmes; Carpenter, Inta Gale; Braid, Donald; Peterson-Veatch, Erika (1996). A folklorist's progress : reflections of a scholar's life. Bloomington: Indiana University. ISBN 1-879407-09-4. OCLC 37282199. |

選集 トンプソン、スティス(1919年)。『北米インディアンにおけるヨーロッパの物語:民話の移動に関する研究』。コロラド州コロラドスプリングス:コロラド大学評議会。OCLC 30703248。 アーネ、アンティ;トンプソン、スティス(1928年)。『民話の類型:分類と書誌』ヘルシンキ:フィンランド科学アカデミー。OCLC 604047970。 トンプソン、スティス(1929)。『北米インディアンの物語』マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。OCLC 1295733602。 トンプソン、スティス(1955)。『民俗文学のモチーフ索引:民話、バラッド、神話における物語要素の分類』改訂増補版。ブルーミントン:インディアナ大学出版局。OCLC 301495255。 トンプソン、スティス(1946)。『民話』。OCLC 1156806364。 トンプソン、スティス (1953)。民俗学に関する 4 つのシンポジウム。インディアナ州ブルーミントン:インディアナ大学出版局。OCLC 706445956。 トンプソン、スティス (1968)。100 のお気に入りの民話。ブルーミントン:インディアナ大学出版局。OCLC 836339166。 トンプソン、スティス、マクダウェル、ジョン・ホームズ、カーペンター、インタ・ゲイル、ブレイド、ドナルド、ピーターソン・ヴィッチ、エリカ (1996)。民俗学者の進歩:学者の人生の反省。ブルーミントン:インディアナ大学。ISBN 1-879407-09-4。OCLC 37282199。 |

| Miscellanea Thompson's 1954 article for The Filson Club History Quarterly entitled "The Beauchamp Family" continues in use by genealogists as of 2011.[13][failed verification] In this article Thompson states that he is descended from a Costin Beauchamp (born 1738) from Somerset County, Maryland which extends back to John Beauchamp one of the members of the Plymouth Company.[14] |

雑録 トンプソンが1954年に『フィルソン・クラブ歴史季刊』に寄稿した論文「ビーチャム家」は、2011年現在も系図研究者によって利用され続けている。 [13][検証失敗] この論文でトンプソンは、自身がメリーランド州サマセット郡出身のコスティン・ビーチャム(1738年生まれ)の子孫であり、その系譜はプリマス会社のメ ンバーの一人であるジョン・ビーチャムにまで遡ると述べている。[14] |

| Footnotes Explanatory notes a. The tale that Pliny Earle Goddard collected and published in Chipewyan Texts (1912) is "The Boy who became Strong". The tale Kittredge refers to is the parallel, Müllenhoff (1845)'s tale "XI. Der blaue Band" from Marne in Dithmarschen, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, translated by Benjamin Thorpe (1853) as "The Blue Riband". |

脚注 解説 a. プリニー・アール・ゴダードが収集し『チペワ語テキスト』(1912年)で発表した物語は「強くなった少年」である。キットリッジが言及する物語は、これ と並行するミュレンホフ(1845)の物語「XI. Der blaue Band」である。これはドイツ・シュレスヴィヒ=ホルシュタイン州ディトマルシェンのマルネ地方に伝わるもので、ベンジャミン・ソープ(1853)に よって「青いリボン」と訳された。 |

| Citations 1. Contradictory information is given about Thompson's deathdate: January 10 or 13, 1976, according to different sources. January 10 is the date given by Peggy Martin, Stith Thompson: His Life and His Role in Folklore Schlolarship, Bloomington, Indiana, Folklore Publications Group, Indiana University, [c. 1976 to 1979], p. 17; it is confirmed by the Obituary in The New York Times, titled "STITH THOMPSON, FOLKLORIST, DIES; Former Indiana Professor and Author Was 90 Organized Institutes", dated January 12, 1976: "Dr. Stith Thompson, a past president of the American Folklore Society, who retired in 1955 as Distinguished Service Professor of Folklore at Indiana University, died Saturday in Columbus, Ind. He was 90 years old." One may think that January 13 was the date of Thompson's funeral service: indicated in a tribute article, it could have been erroneously repeated. 2. Roberts, Warren E. (1996). "Thompson, Stith (1885–1976)". In Brunvand, Jan H. (ed.). American folklore an encyclopedia. New York; London: Garland. pp. 1467–8. ISBN 978-0-8153-0751-8. 3. Dorson 1977. 4. Richmond 1957 5. Dundes, Alan (1966). "The American concept of folklore" (snippet). Journal of the Folklore Institute. 3 (3): 240. doi:10.2307/3813799. JSTOR 3813799.(pp. 226-249) 6. Thompson 1996, pp. 57–58=Thompson 1994, "Distinguished Service 1953–1955", pp.19-20 7. Thompson 1946, p. 114 (Repr. 1977, 2006) 8. Rudy, Jill Terry (2006). "Building a Career by Directing Composition: Harvard, Professionalism, and Stith Thompson at Indiana University". In McLeod, Susan H.; Soven, Margot (eds.). Composing a community: a history of writing across the curriculum. Lauer series in rhetoric and composition. West Lafayette, Ind: Parlor Press. ISBN 978-1-932559-17-0. 9. "About Warren E. Roberts". wer.sitehost.iu.edu. Retrieved 2022-07-02. 10. Dorson 1977, p. 4 11. Roberts 1976, p. 145 12. Smith, T. J. "Past AFS Presidents". The American Folklore Society. Retrieved 2022-07-01. 13. Genealogies of Kentucky Families, Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc, pages 9-47, 1981. 14. Genealogies of Kentucky Families, Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc, page 10, 1981. |

引用 1. トンプソンの死亡日については、異なる情報源によって1976年1月10日と13日の両方が矛盾して記載されている。1月10日はペギー・マーティン著 『スティス・トンプソン: 『スティス・トンプソン:その生涯と民俗学における役割』ブルームントン、インディアナ、インディアナ大学民俗学出版グループ、[1976年から1979 年頃]、17ページで述べられている日付である。これは、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙に掲載された「民俗学者、スティス・トンプソン氏死去 元インディアナ大学教授、著作家、90歳」で確認されている。1955年にインディアナ大学民俗学特別功労教授を退任した、アメリカ民俗学会の元会長であ るスティス・トンプソン博士が、土曜日、インディアナ州コロンバスで死去した。90歳だった。1月13日はトンプソンの葬儀の日だったと思われる。追悼記 事にそう記載されていたため、誤って繰り返された可能性がある。 2. ロバーツ、ウォーレン E. (1996). 「トンプソン、スティス (1885–1976)」 ブルンヴァンド、ジャン・H(編)。『アメリカン・フォークロア百科事典』。ニューヨーク、ロンドン:ガーランド。1467-8 ページ。ISBN 978-0-8153-0751-8。 3. ドーソン 1977。 4. リッチモンド 1957 5. ダンデス、アラン (1966). 「アメリカの民俗学概念」 (抜粋). 民俗学研究所誌. 3 (3): 240. doi:10.2307/3813799. JSTOR 3813799.(pp. 226-249) 6. トンプソン 1996, pp. 57–58=トンプソン 1994, 「顕著な功績 1953–1955」, pp.19-20 7. トンプソン 1946, p. 114 (再版 1977, 2006) 8. ルディ, ジル・テリー (2006). 「作文指導によるキャリア構築:ハーバード大学、プロフェッショナリズム、そしてインディアナ大学のスティス・トンプソン」。スーザン・H・マクラウド、 マーゴット・ソーヴェン(編)。『コミュニティの構築:カリキュラム全体にわたるライティングの歴史』。ラウアー・シリーズ、レトリックと作文。インディ アナ州ウェストラファイエット:パーラープレス。ISBN 978-1-932559-17-0。 9. 「ウォーレン・E・ロバーツについて」 wer.sitehost.iu.edu. 2022-07-02 取得。 10. ドーソン 1977, p. 4 11. ロバーツ 1976, p. 145 12. スミス, T. J. 「AFS 歴代会長」 アメリカ民俗学会. 2022-07-01 取得。 13. 『ケンタッキー州の家族の系譜』、Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc、9-47 ページ、1981 年。 14. 『ケンタッキー州の家族の系譜』、Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc、10 ページ、1981 年。 |

| References Works Thompson, Stith (1946). The Folktale (PDF). Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc. (Reprint) University of Berkeley Press 1977 ISBN 0520035372 (Reprint) Kessinger Publishing 2006 ISBN 978-1425486563 Biographies Richmond, Winthrop Edson, ed. (1957), "Short Biographical Sketch", Studies in Folklore. In honor of distinguished Service Professor Stith Thompson (snippet), Folklore series, vol. 9, Indiana University Press, pp. xi- Dorson, Richard M. (January–March 1977). "Stith Thompson (1885-1976)" (snippet). The Journal of American Folklore. 90 (355). American Folklore Society: 2–7. JSTOR 539017. Roberts, Warren E. (1976). "Stith Thompson (1885-1976)". Indiana Folklore. 9: 138–146. (Reprinted) "IV. Nachrichten", Fabula Volume 21, Issue 1 (1980) de Gruyter Thompson, Stith (1996). A Folklorist's Progress: Reflections of a Scholar's Life. Indiana University Press. ISBN 1879407086. - mss. A Folklorist's Progress of 1956; and Second Wind 1966 Thompson, Stith (1994). "Harvard, 1912-1914; Entrenching at Indiana: 1921-1926; Distinguished Service: 1953-1955". The Folklore Historian. 11: 15–24, 25–31, 32–41. - Excerpted from1956 ms. to which is added "Aged Eighty and Beyond," dated 1966, pp. 42–47 |

参考文献 著作 トンプソン、スティス (1946). 『民話』 (PDF). ホルト・ラインハート・アンド・ウィンストン社. (復刻版) バークレー大学出版局 1977 ISBN 0520035372 (復刻版) ケシンジャー出版 2006 ISBN 978-1425486563 伝記 リッチモンド、ウィンスロップ・エドソン編(1957年)、「略歴」、民俗学研究。功績ある教授スティス・トンプソンを称えて(抜粋)、民俗学シリーズ第9巻、インディアナ大学出版局、xi- ドーソン、リチャード・M.(1977年1月-3月)。「スティス・トンプソン(1885-1976)」(抜粋)。『アメリカン・フォークロア・ジャーナル』90 (355)。アメリカン・フォークロア協会:2-7。JSTOR 539017。 ロバーツ、ウォーレン E. (1976)。「スティス・トンプソン(1885-1976)」。インディアナ・フォークロア。9: 138–146。 (再版) 「IV. Nachrichten」、ファブラ第 21 巻、第 1 号 (1980) de Gruyter トンプソン、スティス (1996)。民俗学者の進歩:学者の人生の回想。インディアナ大学出版。ISBN 1879407086。 - 原稿『民俗学者の歩み』(1956年)、『第二の風』(1966年) トンプソン、スティス(1994)。「ハーバード大学時代:1912-1914年;インディアナ大学での基盤固め:1921-1926年; 顕著な功績:1953-1955年」。『民俗史家』11号:15-24頁、25-31頁、32-41頁。- 1956年原稿からの抜粋。これに1966年付「八十歳を超えて」を追加、42-47頁 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stith_Thompson |

★アールネ・トンプソンのタイプ・インデックス(Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index)

| アールネ・トンプソンのタイプ・インデックス(英: Aarne-Thompson type index、AT分類)とは、世界各地に伝わる昔話をその類型ごとに収集・分類したもの。 アンティ・アールネにより編纂され、スティス・トンプソンにより増補・改訂されたことから二人の名を取ってこう呼ばれている。昔話の研究においては分類体 系の標準として世界的に用いられている。類型ごとにAT番号と呼ばれる番号が振り当てられ、索引(インデックス)または目録(カタログ)として参照され る。もちろん、一つの話に対し複数のモチーフ類型が当てはまることもある。 アールネ=トムソンの「昔話の型」(小澤俊夫[1])、アールネ/トンプソンの「民話の型」(香川大学、最上英明[2])、「昔話のモチーフ・インデックス」(高木昌史[3])などの和訳表記もみられる。 アールネ=トンプソン=ウター分類(Aarne–Thompson–Uther type index、ATU分類)は、ハンス=イェルク・ウター(ドイツ語版)がその編纂に加わった改訂版である。 |

|

| 履歴 フィンランドの民俗学者アンティ・アールネは、師カールレ・クローン (Kaarle Krohn) の勧めによって、ヨーロッパ各地の昔話800あまりをまとめた上で大きく「動物昔話」「本格昔話」「笑話・逸話」の三つに分類し、 "Verzeichnis der Märchentypen" (Folklore Fellows Communications (FFC) 誌、第3巻、1910年) として発表した。 米国のスティス・トンプソンによってより多くの昔話を元に、The types of the folktale. a classification and bibliography (FFC誌、第74巻、1928年[4]) ) として増補され、さらにその第2改訂版 ("2nd revision," FFC誌、第184巻、1961年[5]) が発表された。 この改訂の際、アールネの三つの分類にさらに形式譚が追加された。 トンプソン以後も改訂は続けられ、2005年に、ハンス=イェルク・ウター(ドイツ語版)によってThe types of international folktales. a classification and bibliography (FFC誌、第 284-286巻) が三分冊で発表された。これは2016年に『国際昔話話型カタログ 分類と文献目録』のタイトルで日本語に翻訳・出版されている[6]。 |

|

| 用例 たとえば、『ノルウェー民話集』収録「海の底の臼」の話と、これと酷似した日本の民話、「海の水はなぜ鹹い」(柳田國男編『日本の昔話』[7])は、いず れも《魔法の臼》のモチーフ(AT 565型)に分類される[1]。同様に、グリム童話「白い花嫁と黒い花嫁」と、「米嚢粟嚢〔こめぶくろ・あわぶくろ〕」[8]には、AT 403が当てられる。[1] |

|

| 分類 1. 動物昔話 (1-299) 野生動物 (1-99) 野生動物と家畜 (100-149) 野生動物と人間 (150-199) 家畜 (200-219) その他の動物 (220-299) 2. 本格昔話 (300-1199) 魔法の話 (300-749) 超自然的な敵 (300-399) 超自然的なまたは魔法をかけられた配偶者またはその他の近親者 (400-459) 超自然的な課題 (460-499) 超自然的な援助者 (500-559) 超自然的な品物 (560-649) 超自然的な能力または知識 (650-699) その他の超自然的な話 (700-749) 宗教的な話 (750-849) 神の祝福と罰 (750-779) 明るみになる真実 (780-791) 天国 (800-809) 悪魔 (810-826) その他の宗教的な話 (827-849) 短編小説的な話 (850-999) 愚かな悪魔の話 (1000-1199) 3. 笑話・逸話 (1200-1999) 4. 形式譚 (2000-2399) 数字、物、動物、または名前に基づく話 (2000-2020) 死に関する話 (2021-2024) 食に関する話 (2025-2028) その他の出来事に関する話 (2029-2075) 5. その他(どれにも分類できない昔話) (2400-2499) 牛の皮一枚の土地(2400)[9] |

|

| 日本の昔話 日本の昔話にAT番号を付する試みはいくつもなされている[10]。 関敬吾・著『日本昔話集成』全6巻 角川書店、1950年 - 1958年 収録話数約8000。分類はAT番号によるが、さらに細分化した下位分類を行い、約650の話型を規定している。 関敬吾・野村純一・大島広志・編『日本昔話大成』全12巻 角川書店、1979年 - 1980年 収録話数約35,000。『日本昔話集成』の分類法を基本に、新たに90の類型を追加。 稲田浩二・小澤俊夫・編『日本昔話通観』全31巻 同朋舎出版、 1977年 - 1990年 収録話数約60,000。1211話型に分類。 |

|

| 出典 1. ^ a b c 柳田, 國男『日本の昔話』小澤俊夫(解説)、新潮文庫、1983年、187-頁。ISBN 4-10-104703-0。「欧米の昔話研究者たちのあいだで共通のカタログとして使用されているアールネ=トムソン共著『昔話の型』..」 2. ^ 最上, 英明 (2 1998). “トゥーランドット物語の起源”. 香川大学経済論叢 71 (2). 3. ^ 高木, 昌史『柳田國男とヨーロッパ: 口承文芸の東西』(snippet)三交社、2006年、74-頁。ISBN 4-10-104703-0。 4. ^ Aarne, Antti (1928). “The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography” (snippet). FF communications 74. 5. ^ Aarne, Antti (1961). “The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography” (snippet). FF communications 184. 6.^ ハンス=イェルク・ウター 著、加藤耕義 訳『国際昔話話型カタログ 分類と文献目録』小澤俊夫 日本語版監修、小澤昔ばなし研究所、2016年。ISBN 9784902875768。(タイトルについては『国際昔話話型カタログ アンティ・アールネとスティス・トムソンのシステムに基づく分類と文献目録』で登録されている目録もある(CiNii Booksなど)。) 7. ^ 柳田『日本の昔話』p.120-123。岩手県上閉伊郡で収集 8. ^ 柳田『日本の昔話』、98-99頁。津軽七つ石で収集。 9. ^ 斧原孝守「東アジアにおける「牛の皮一枚の土地」(AT2400)伝説の展開」『東洋史訪』第3号、80–91頁、1997年3月31日。 10.^ 鳥取県立図書館 (2007年3月27日). “日本には、どのくらいの種類の昔話が伝承されているか。また、外国にも日本と同じタイプのストーリーの昔話があるか。”. 国立国会図書館. 2017年11月8日閲覧。 |

|

| https://x.gd/Nr0Nj |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099