A Chronology of Making of Behavioral Economics

エピグラム:「政治経済の基礎、そして社会科学全般の基礎は、まぎれもなく心理学にある。社 会科学の法則を心理学の原理から演繹できるようになる日が、いつかきっと来るだろう」——ヴィルフレド・パレート[Vilfredo Federico Damaso Pareto, 1848-1923](1906)

| Behavioral

economics is the study of the psychological (e.g. cognitive,

behavioral, affective, social) factors involved in the decisions of

individuals or institutions, and how these decisions deviate from those

implied by traditional economic theory.[1][2] Behavioral economics is primarily concerned with the bounds of rationality of economic agents. Behavioral models typically integrate insights from psychology, neuroscience and microeconomic theory.[3][4] Behavioral economics began as a distinct field of study in the 1970s and 1980s, but can be traced back to 18th-century economists, such as Adam Smith, who deliberated how the economic behavior of individuals could be influenced by their desires.[5] The status of behavioral economics as a subfield of economics is a fairly recent development; the breakthroughs that laid the foundation for it were published through the last three decades of the 20th century.[6][7] Behavioral economics is still growing as a field, being used increasingly in research and in teaching.[8] |

行動経済学とは、個人や組織の意思決定に関わる心理的(認知的、行動

的、感情的、社会的など)要因を研究し、これらの意思決定が伝統的な経済理論が示唆するものからどのように逸脱しているかを研究するものである[1]

[2]。 行動経済学は、主に経済主体の合理性の範囲に関心を持っている。行動モデルは通常、心理学、神経科学、ミクロ経済理論からの洞察を統合している[3] [4]。 行動経済学は1970年代から1980年代にかけて独自の研究分野として始まったが、アダム・スミスなどの18世紀の経済学者にまで遡ることができる。 行動経済学が経済学のサブフィールドとして位置づけられるようになったのはかなり最近のことであり、その基礎を築いたブレークスルーは20世紀の最後の 30年間に発表されたものである[6][7]。行動経済学は現在も分野として成長を続けており、研究や教育においてますます利用されるようになっている [8]。 |

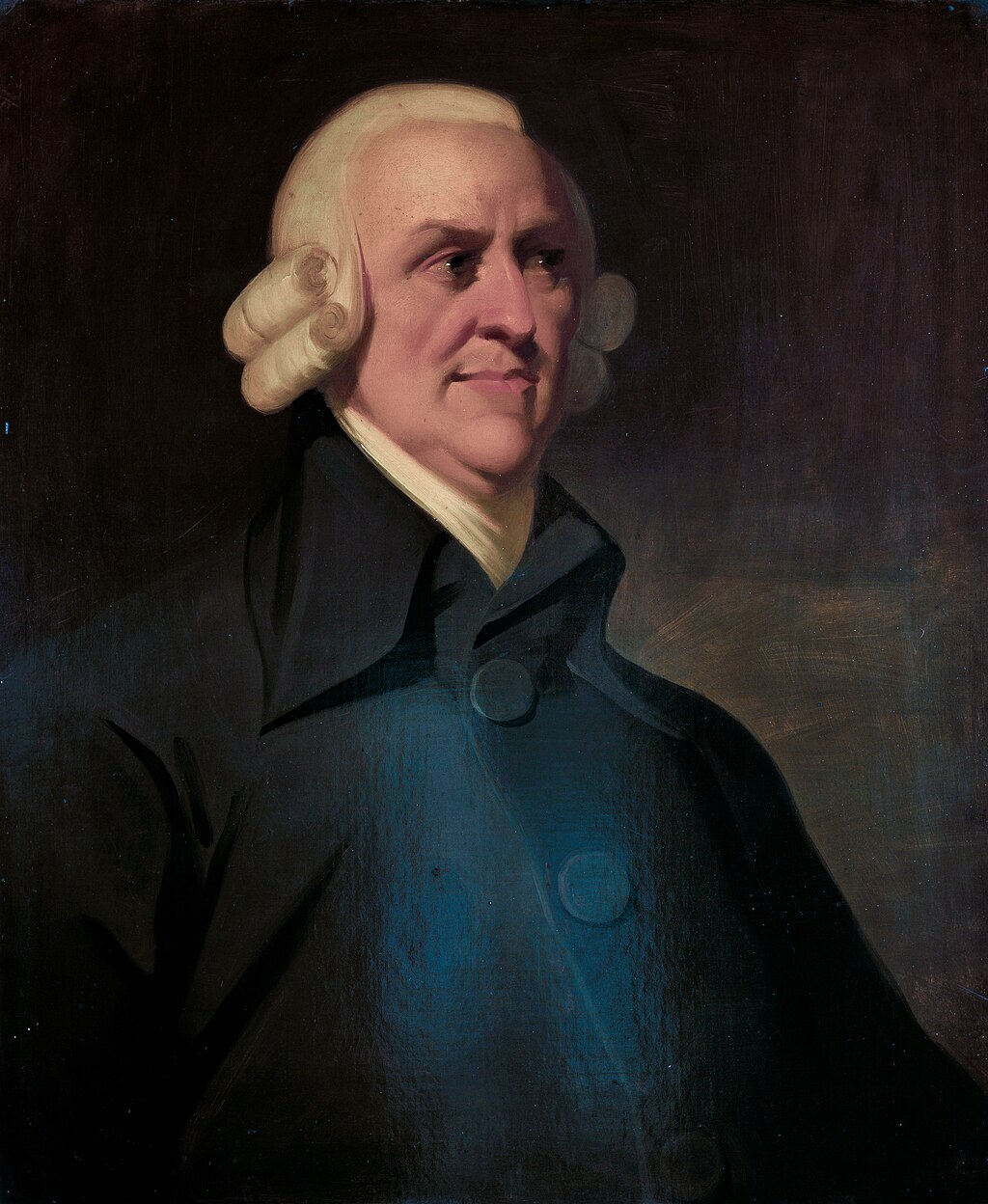

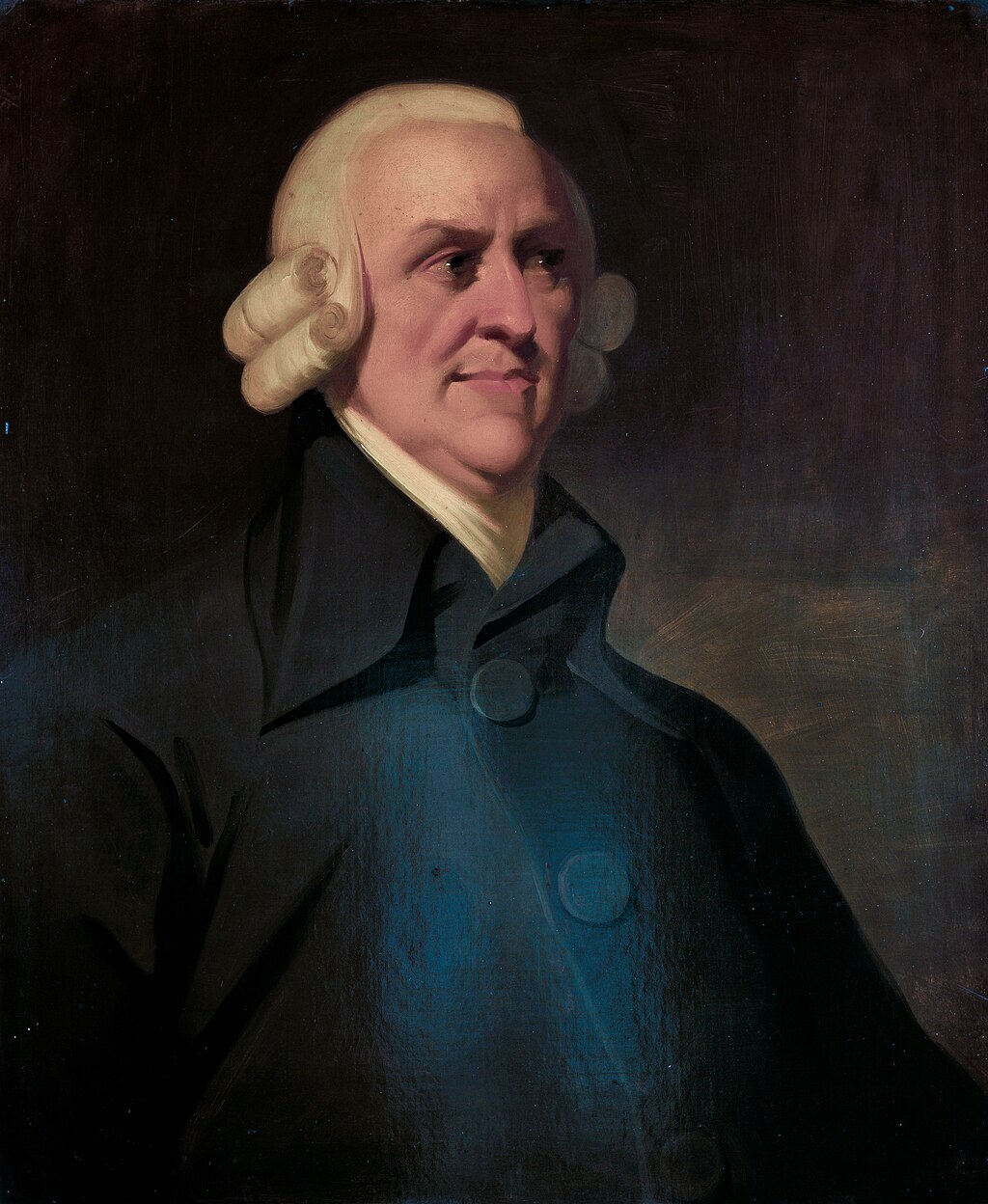

History Adam Smith, author of The Wealth of Nations (1776) and The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) Early classical economists included psychological reasoning in much of their writing, though psychology at the time was not a recognized field of study.[9] In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith wrote on concepts later popularized by modern Behavioral Economic theory, such as loss aversion.[9] Jeremy Bentham, a Utilitarian philosopher in the 1700s conceptualized utility as a product of psychology.[9] Other economists who incorporated psychological explanations in their works included Francis Edgeworth, Vilfredo Pareto and Irving Fisher. A rejection and elimination of psychology from economics in the early 1900s brought on a period defined by a reliance on empiricism.[9] There was a lack of confidence in hedonic theories, which saw pursuance of maximum benefit as an essential aspect in understanding human economic behavior.[6] Hedonic analysis had shown little success in predicting human behavior, leading many to question its viability as a reliable source for prediction.[6] There was also a fear among economists that the involvement of psychology in shaping economic models was inordinate and a departure from accepted principles.[10] They feared that an increased emphasis on psychology would undermine the mathematic components of the field.[11][12] To boost the ability of economics to predict accurately, economists started looking to tangible phenomena rather than theories based on human psychology.[6] Psychology was seen as unreliable to many of these economists as it was a new field, not regarded as sufficiently scientific.[9] Though a number of scholars expressed concern towards the positivism within economics, models of study dependent on psychological insights became rare.[9] Economists instead conceptualized humans as purely rational and self-interested decision makers, illustrated in the concept of homo economicus.[12] The resurgence of psychology within economics, which facilitated the expansion of behavioral economics, has been linked to the cognitive revolution.[13][14] In the 1960s, cognitive psychology began to shed more light on the brain as an information processing device (in contrast to behaviorist models). Psychologists in this field, such as Ward Edwards,[15] Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman began to compare their cognitive models of decision-making under risk and uncertainty to economic models of rational behavior. These developments spurred economists to reconsider how psychology could be applied to economic models and theories.[9] Concurrently, the Expected utility hypothesis and discounted utility models began to gain acceptance. In challenging the accuracy of generic utility, these concepts established a practice foundational in behavioral economics: Building on standard models by applying psychological knowledge.[6] Mathematical psychology reflects a long-standing interest in preference transitivity and the measurement of utility.[16] |

歴史 アダム・スミス、『国富論』(1776年)と『道徳感情論』(1759年)の著者。 アダム・スミスは『道徳感情論』の中で、損失回避など、後に現代の行動経済理論によって一般化された概念について書いている[9]。 1900年代初頭における経済学からの心理学の否定と消去法によって、経験主義への依存によって定義される時代が到来した[9]。 人間の経済行動を理解する上で、最大利益の追求を本質的な側面と見なすヘドニック理論に対する信頼が欠如していた[6]。ヘドニック分析は人間の行動を予 測する上でほとんど成功を示さなかったため、多くの人が予測のための信頼できる情報源としての実行可能性に疑問を抱くようになった[6]。 また経済学者の間では、経済モデルの形成に心理学が関与することは行き過ぎであり、受け入れられている原則から逸脱しているという懸念があった[10]。 彼らは心理学を重視する傾向が強まることで、この分野の数学的な要素が損なわれることを恐れていた[11][12]。 経済学の正確な予測能力を高めるために、経済学者たちは人間の心理に基づく理論ではなく、目に見える現象に注目し始めた[6]。心理学は新しい分野であ り、十分に科学的であるとはみなされていなかったため、これらの経済学者たちの多くにとっては信頼できないものとみなされていた[9]。多くの学者が経済 学内の実証主義に対する懸念を表明したものの、心理学的洞察に依存した研究モデルは稀なものとなった[9]。経済学者たちはその代わりに、ホモ・エコノミ クスの概念に示されるように、人間を純粋に合理的で利己的な意思決定者として概念化した[12]。 1960年代、認知心理学は(行動主義モデルとは対照的に)情報処理装置としての脳に光を当て始めた。この分野の心理学者であるウォード・エドワーズ、エ イモス・トヴェルスキー、ダニエル・カーネマンらは、リスクや不確実性の下での意思決定に関する認知モデルを合理的行動に関する経済モデルと比較し始め た。同時に、期待効用仮説と割引効用モデルが受け入れられ始めた。一般的効用の正確性に挑戦する中で、これらの概念は行動経済学の基礎となる実践を確立し た。 数理心理学は、選好の推移性と効用の測定に対する長年の関心を反映している[16]。 |

Bounded rationality Herbert A. Simon, winner of the 1975 Turing award, the 1978 Nobel Prize in economics, and the 1988 John von Neumann Theory Prize Bounded rationality is the idea that when individuals make decisions, their rationality is limited by the tractability of the decision problem, their cognitive limitations and the time available. Herbert A. Simon proposed bounded rationality as an alternative basis for the mathematical modeling of decision-making. It complements "rationality as optimization", which views decision-making as a fully rational process of finding an optimal choice given the information available.[17] Simon used the analogy of a pair of scissors, where one blade represents human cognitive limitations and the other the "structures of the environment", illustrating how minds compensate for limited resources by exploiting known structural regularity in the environment.[17] Bounded rationality implicates the idea that humans take shortcuts that may lead to suboptimal decision-making. Behavioral economists engage in mapping the decision shortcuts that agents use in order to help increase the effectiveness of human decision-making. Bounded rationality finds that actors do not assess all available options appropriately, in order to save on search and deliberation costs. As such decisions are not always made in the sense of greatest self-reward as limited information is available. Instead agents shall choose to settle for an acceptable solution. One approach, adopted by Richard M. Cyert and March in their 1963 book A Behavioral Theory of the Firm, was to view firms as coalitions of groups whose targets were based on satisficing rather than optimizing behaviour.[18][19] Another treatment of this idea comes from Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler's Nudge.[20][21] Sunstein and Thaler recommend that choice architectures are modified in light of human agents' bounded rationality. A widely cited proposal from Sunstein and Thaler urges that healthier food be placed at sight level in order to increase the likelihood that a person will opt for that choice instead of less healthy option. Some critics of Nudge have lodged attacks that modifying choice architectures will lead to people becoming worse decision-makers.[22][23] |

境界合理性 ハーバート・A・サイモン、1975年チューリング賞、1978年ノーベル経済学賞、1988年ジョン・フォン・ノイマン理論賞受賞者 境界合理性とは、個人が意思決定を行う際、その合理性は意思決定問題の扱いやすさ、認知の限界、利用可能な時間によって制限されるという考え方である。 ハーバート・サイモン(Herbert A. Simon)は、意思決定の数学的モデリングの代替的基礎として、境界合理性を提唱した。サイモンは「最適化としての合理性」を補完するものであり、意思 決定を、利用可能な情報が与えられた場合に最適な選択を見出すという完全に合理的なプロセスとして捉えるものである[17]。サイモンは、一対のハサミの アナロジーを用いて、一方の刃が人間の認知的限界を表し、他方の刃が「環境の構造」を表し、環境における既知の構造的規則性を利用することによって、心が どのように限られた資源を補うかを説明した[17]。行動経済学者は、人間の意思決定の有効性を高めるために、行動主体が用いる意思決定の近道をマッピン グしている。境界合理性は、行為者が探索や熟考のコストを節約するために、利用可能な選択肢をすべて適切に評価しないことを発見する。そのため、利用可能 な情報が限られているため、最大限の自己報酬を得るという意味で意思決定が行われるとは限らない。その代わりに、エージェントは受け入れ可能な解決策に落 ち着くことを選択する。リチャード・M・サイアートとマーチが1963年に出版した『A Behavioral Theory of the Firm(企業の行動理論)』で採用したアプローチの1つは、企業を、最適化行動というよりもむしろ飽和充足行動に基づいているグループの連合とみなすこ とであった[18][19]。サンステインとサーラーの提案で広く引用されているのは、健康的でない選択肢の代わりにその選択肢を選ぶ可能性を高めるため に、より健康的な食品を視界に入る位置に配置することである。ナッジの批評家の中には、選択アーキテクチャを修正することは、人々がより悪い意思決定者に なることにつながるという攻撃を行っている[22][23]。 |

Prospect theory Daniel Kahneman, winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize in economics In 1979, Kahneman and Tversky published Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk, that used cognitive psychology to explain various divergences of economic decision making from neo-classical theory.[24] Kahneman and Tversky utilising prospect theory determined three generalisations; gains are treated differently than losses, outcomes received with certainty are overweighed relative to uncertain outcomes and the structure of the problem may affect choices. These arguments were supported in part by altering a survey question so that it was no longer a case of achieving gains but averting losses and the majority of respondents altered their answers accordingly. In essence proving that emotions such as fear of loss, or greed can alter decisions, indicating the presence of an irrational decision-making process. Prospect theory has two stages: an editing stage and an evaluation stage. In the editing stage, risky situations are simplified using various heuristics. In the evaluation phase, risky alternatives are evaluated using various psychological principles that include: Reference dependence: When evaluating outcomes, the decision maker considers a "reference level". Outcomes are then compared to the reference point and classified as "gains" if greater than the reference point and "losses" if less than the reference point. Loss aversion: Losses are avoided more than equivalent gains are sought. In their 1992 paper, Kahneman and Tversky found the median coefficient of loss aversion to be about 2.25, i.e., losses hurt about 2.25 times more than equivalent gains reward.[25] Non-linear probability weighting: Decision makers overweigh small probabilities and underweigh large probabilities—this gives rise to the inverse-S shaped "probability weighting function". Diminishing sensitivity to gains and losses: As the size of the gains and losses relative to the reference point increase in absolute value, the marginal effect on the decision maker's utility or satisfaction falls. In 1992, in the Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, Kahneman and Tversky gave a revised account of prospect theory that they called cumulative prospect theory.[25] The new theory eliminated the editing phase in prospect theory and focused just on the evaluation phase. Its main feature was that it allowed for non-linear probability weighting in a cumulative manner, which was originally suggested in John Quiggin's rank-dependent utility theory. Psychological traits such as overconfidence, projection bias and the effects of limited attention are now part of the theory. Other developments include a conference at the University of Chicago,[26] a special behavioral economics edition of the Quarterly Journal of Economics ("In Memory of Amos Tversky"), and Kahneman's 2002 Nobel Prize for having "integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty."[27] A further argument of Behavioural Economics relates to the impact of the individual's cognitive limitations as a factor in limiting the rationality of people's decisions. Sloan first argued this in his paper 'Bounded Rationality' where he stated that our cognitive limitations are somewhat the consequence of our limited ability to foresee the future, hampering the rationality of decision.[28] Daniel Kahneman further expanded upon the effect cognitive ability and processes have on decision making in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. He delved into two forms of thought: fast thinking, which he considered "operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control",[29] and slow thinking, the allocation of cognitive ability, choice, and concentration. Fast thinking utilises heuristics, or shortcuts, which provide an immediate but often irrational and imperfect solution. He proposed that hindsight bias, confirmation bias, and outcome bias (among others) originate from such shortcuts. A key example of fast thinking and the resultant irrational decisions is the 2008 financial crisis. |

プロスペクト理論 ダニエル・カーネマン(2002年ノーベル経済学賞受賞者 1979年、カーネマンとトヴェルスキーはプロスペクト理論を発表した: カーネマンとトヴェルスキーは、プロスペクト理論を用いて、利得は損失とは異なるものとして扱われること、確実性のある結果は不確実性のある結果と比較し て過大評価されること、問題の構造が選択に影響を与える可能性があること、という3つの一般論を決定した[24]。これらの議論は、もはや利益を得ること ではなく、損失を回避することであるようにアンケートの質問を変更することで部分的に支持され、回答者の大半はそれに従って回答を変更した。要するに、損 失への恐れや貪欲さといった感情が意思決定を変える可能性があり、非合理的な意思決定プロセスが存在することを証明しているのである。プロスペクト理論に は、編集段階と評価段階の2段階がある。編集段階では、さまざまなヒューリスティックを用いてリスクのある状況を単純化する。評価段階では、以下のような さまざまな心理学的原理を用いてリスクのある選択肢を評価する: 参照依存: 結果を評価する際、意思決定者は「基準レベル」を考慮する。そして結果は基準点と比較され、基準点より大きければ「利益」、小さければ「損失」に分類され る。 損失回避: 同等の利益を求めるよりも損失を避ける。1992年の論文で、カーネマンとトヴェルスキーは損失回避の係数の中央値が約2.25であることを発見した。 非線形確率加重: 意思決定者は小さな確率を過大評価し、大きな確率を過小評価する-これが逆S字型の「確率加重関数」を生む。 損益に対する感度が逓減する: 基準点に対する利益と損失の大きさの絶対値が大きくなるにつれて、意思決定者の効用または満足度に対する境界効果は低下する。 1992年、カーネマンとトヴェルスキーは『Journal of Risk and Uncertainty』誌において、プロスペクト理論の改訂版を発表し、累積プロスペクト理論と呼んだ[25]。その主な特徴は、ジョン・クイギンの順 位依存効用理論で元々示唆されていた累積的な方法で非線形確率の重み付けを可能にしたことである。自信過剰、投影バイアス、限定的注意の影響といった心理 学的特性は、現在では理論の一部となっている。その他の発展としては、シカゴ大学での会議[26]、Quarterly Journal of Economicsの行動経済学特集号(「In Memory of Amos Tversky」)、カーネマンの2002年のノーベル賞受賞(「In integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially regarding human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty」)が挙げられる[27]。 行動経済学のさらなる論点は、人々の意思決定の合理性を制限する要因としての個人の認知的限界の影響に関するものである。スローンは、論文「境界合理性」 の中で最初にこのことを主張し、私たちの認知的限界は、将来を予見する能力が限られているために、意思決定の合理性を阻害している結果であると述べた [28]。ダニエル・カーネマンは、著書「Thinking, Fast and Slow」の中で、認知的能力やプロセスが意思決定に与える影響をさらに拡大した。彼は思考の2つの形態を掘り下げている。「ほとんど努力せず、自発的な コントロールの感覚もなく、自動的かつ迅速に作動する」と考える高速思考[29]と、認知能力、選択、集中の配分を考える低速思考である。速い思考は ヒューリスティックス、つまり近道を利用し、即座に解決策を提供するが、しばしば非合理的で不完全な解決策を提供する。彼は、後知恵バイアス、確証バイア ス、結果バイアス(とりわけ)は、このようなショートカットに由来すると提唱した。ファスト・シンキングとその結果としての非合理的な意思決定の重要な例 は、2008年の金融危機である。 |

| Nudge theory Main article: Nudge theory Nudge is a concept in behavioral science, political theory and economics which proposes designs or changes in decision environments as ways to influence the behavior and decision making of groups or individuals—in other words, it's "a way to manipulate people's choices to lead them to make specific decisions".[30] The first formulation of the term and associated principles was developed in cybernetics by James Wilk before 1995 and described by Brunel University academic D. J. Stewart as "the art of the nudge" (sometimes referred to as micronudges[31]). It also drew on methodological influences from clinical psychotherapy tracing back to Gregory Bateson, including contributions from Milton Erickson, Watzlawick, Weakland and Fisch, and Bill O'Hanlon.[32] In this variant, the nudge is a microtargeted design geared towards a specific group of people, irrespective of the scale of intended intervention. In 2008, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein's book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness brought nudge theory to prominence.[30] It also gained a following among US and UK politicians, in the private sector and in public health.[33] The authors refer to influencing behavior without coercion as libertarian paternalism and the influencers as choice architects.[34] Thaler and Sunstein defined their concept as:[35] A nudge, as we will use the term, is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people's behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not. Nudging techniques aim to capitalise on the judgemental heuristics of people. In other words, a nudge alters the environment so that when heuristic, or System 1, decision-making is used, the resulting choice will be the most positive or desired outcome.[36] An example of such a nudge is switching the placement of junk food in a store, so that fruit and other healthy options are located next to the cash register, while junk food is relocated to another part of the store.[37] In 2008, the United States appointed Sunstein, who helped develop the theory, as administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.[34][38][39] Notable applications of nudge theory include the formation of the British Behavioural Insights Team in 2010. It is often called the "Nudge Unit", at the British Cabinet Office, headed by David Halpern.[40] In addition, the Penn Medicine Nudge Unit is the world's first behavioral design team embedded within a health system. Nudge theory has also been applied to business management and corporate culture, such as in relation to health, safety and environment (HSE) and human resources. Regarding its application to HSE, one of the primary goals of nudge is to achieve a "zero accident culture".[41] In contrast to nudges, which aim to guide people toward better decisions, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein also introduced the concept of sludge, which refers to unnecessary frictions or barriers that make it harder for individuals to take beneficial actions—such as confusing forms or hidden fees. [42] |

ナッジ理論 主な記事 ナッジ理論 ナッジとは、行動科学、政治理論、経済学における概念であり、集団や個人の行動や意思決定に影響を与える方法として、意思決定環境の設計や変更を提案する もので、言い換えれば「人々の選択を操作して特定の意思決定をさせる方法」である[30]。 この用語と関連する原則の最初の定式化は、1995年以前にジェームス・ウィルクによってサイバネティクスで開発され、ブルネル大学の学者D・J・スチュ ワートによって「ナッジの技術」(マイクロナッジと呼ばれることもある[31])として説明された。また、ミルトン・エリクソン、ワツラウィック、ウィー クラ ンド&フィッシュ、ビル・オハンロンからの貢献を含め、グレゴリー・ベ イトソンにさかのぼる臨床心理療法からの方法論的影響も利用してい る。 2008年、リチャード・ターラー とキャス・サンスティーンによる著書『Nudge: 著者らは、強制することなく行動に影響を与えること をリバタリアン的パターナリズムと呼び、影響を与える側を選 択の設計者と呼んでいる[34]。 ナッジとは、選択肢を禁じたり、経済的インセンティブを大きく変えたりすることなく、予測可能な方法で人々の行動を変化させる選択アーキテクチャのあらゆ る側面である。単なるナッジとみなすには、介入を避けるのが簡単で安価でなければならない。ナッジは強制ではない。フルーツを目の高さに置くことはナッジ にカウントされる。ジャンクフードの禁止はそうではない。 ナッジングのテクニックは、人民の判断的ヒューリスティックを利用することを目的としている。言い換えれば、ナッジは、ヒューリスティックな意思決 定、つまりシステム1が使用されたときに、結果として得られる選 択が最も肯定的な、または望ましい結果になるように環境を変 える。 2008年、アメリカはこの理論の開発に貢献したサンスティーンを情報規制庁長官に任命した[34][38][39]。 ナッジ理論の注目すべき応用例としては、2010年の英国行動洞察チームの結成が挙げられる。これはしばしば「ナッジ・ユニット」と呼ばれ、デビッド・ハ ルパーンが率いる英国内閣府のものである[40]。さらに、ペンシルベニア大学医学部のナッジ・ユニットは、保健システムに組み込まれた世界初の行動デザ インチームである。 ナッジ理論は、保健、安全、環境(HSE)や人事など、企業経営や企業文化にも応用されている。HSEへの適用に関しては、ナッジの主要な目標のひとつ は、「事故ゼロの文化」を達成することである[41]。 人々をより良い意思決定へと導くことを目的とするナッジとは対照的に、リチャード・ターラーとキャス・サンステインは、スラッジ(sludge)という概 念も導入している。スラッジとは、個人が有益な行動をとることを難しくする不必要な摩擦や障壁のことであり、分かりにくいフォームや隠れた手数料などを指 す。[42] |

| Criticisms Cass Sunstein has responded to critiques at length in his The Ethics of Influence[43] making the case in favor of nudging against charges that nudges diminish autonomy,[44] threaten dignity, violate liberties, or reduce welfare. Ethicists have debated this rigorously.[45] These charges have been made by various participants in the debate from Bovens[46] to Goodwin.[47] Wilkinson for example charges nudges for being manipulative, while others such as Yeung question their scientific credibility.[48] Some, such as Hausman & Welch[49] have inquired whether nudging should be permissible on grounds of (distributive[clarification needed]) justice; Lepenies & Malecka[50] have questioned whether nudges are compatible with the rule of law. Similarly, legal scholars have discussed the role of nudges and the law.[51][52] Behavioral economists such as Bob Sugden have pointed out that the underlying normative benchmark of nudging is still homo economicus, despite the proponents' claim to the contrary.[53] Recent scholarship has raised concerns about the use of vibrational nudges in digital consumer environments, suggesting that haptic feedback—such as subtle mobile phone vibrations—can increase purchasing behavior without conscious awareness. The study questions whether such subliminal tactics cross ethical boundaries by manipulating impulse control in ways that blur the line between persuasion and coercion.[54] It has been remarked that nudging is also a euphemism for psychological manipulation as practiced in social engineering.[55][56] There exists an anticipation and, simultaneously, implicit criticism of the nudge theory in works of Hungarian social psychologists who emphasize the active participation in the nudge of its target (Ferenc Merei[57] and Laszlo Garai[58]). |

批判 キャス・サンステインは『The Ethics of Influence(影響力の倫理)』[43]の中で、ナッジが自律性を低下させ[44]、尊厳を脅かし、自由を侵害し、福祉を低下させるという非難に対 してナッジを支持するケースを提示し、批判に長々と反論している。倫理学者たちはこのことについて厳しく議論してきた[45]。これらの告発は、ボーヴェ ンス[46]からグッドウィン[47]に至るまで、議論における様々な参加者によってなされてきた。例えばウィルキンソンは、ナッジが操作的であると告発 し、ヨンのような他の者はその科学的信頼性に疑問を呈している[48]。 Hausman&Welch[49]のように、(分配的[要解釈])正義を理由にナッジングが許容されるべきかどうかを問う者もいれば、 Lepenies&Malecka[50]はナッジングが法の支配と両立するかどうかを問うている。同様に、法学者もナッジと法の役割について議論してい る[51][52]。 ボブ・サグデンのような行動経済学者は、ナッジの根底にある規範的ベンチマークは、推進者がそう主張しているにもかかわらず、依然としてホモ・エコノミク スであると指摘している[53]。 最近の研究では、デジタル消費者環境における振動ナッジの使用について懸念が提起されており、微妙な携帯電話の振動のような触覚フィードバックが、意識せ ずに購買行動を増加させる可能性があることが示唆されている。この研究では、このようなサブリミナル的な戦術が、説得と強制の境界線を曖昧にするような方 法で衝動制御を操作することによって、倫理的な境界線を越えるかどうかが疑問視されている[54]。 ナッジングは、社会工学で実践されているような心理的操作の婉曲表現でもあると指摘されている[55][56]。 ハンガリーの社会心理学者の著作には、ナッジ理論に対する予期と同時に暗黙の批判が存在し、彼らはナッジへのターゲットの積極的な参加を強調している (Ferenc Merei[57]とLaszlo Garai[58])。 |

| Concepts Behavioral economics aims to improve or overhaul traditional economic theory by studying failures in its assumptions that people are rational and selfish. Specifically, it studies the biases, tendencies and heuristics of people's economic decisions. It aids in determining whether people make good choices and whether they could be helped to make better choices. It can be applied both before and after a decision is made. Search heuristics Behavioral economics proposes search heuristics as an aid for evaluating options. It is motivated by the fact that it is costly to gain information about options and it aims to maximise the utility of searching for information. While each heuristic is not wholistic in its explanation of the search process alone, a combination of these heuristics may be used in the decision-making process. There are three primary search heuristics. Satisficing Satisficing is the idea that there is some minimum requirement from the search and once that has been met, stop searching. After satisficing, a person may not have the most optimal option (i.e. the one with the highest utility), but would have a "good enough" one. This heuristic may be problematic if the aspiration level is set at such a level that no products exist that could meet the requirements. Directed cognition Directed cognition is a search heuristic in which a person treats each opportunity to research information as their last. Rather than a contingent plan that indicates what will be done based on the results of each search, directed cognition considers only if one more search should be conducted and what alternative should be researched. Elimination by aspects Whereas satisficing and directed cognition compare choices, elimination by aspects compares certain qualities. A person using the elimination by aspects heuristic first chooses the quality that they value most in what they are searching for and sets an aspiration level. This may be repeated to refine the search. i.e. identify the second most valued quality and set an aspiration level. Using this heuristic, options will be eliminated as they fail to meet the minimum requirements of the chosen qualities.[59] Heuristics and cognitive effects Besides searching, behavioral economists and psychologists have identified other heuristics and other cognitive effects that affect people's decision making. These include: Mental accounting Mental accounting refers to the propensity to allocate resources for specific purposes. Mental accounting is a behavioral bias that causes one to separate money into different categories known as mental accounts either based on the source or the intention of the money.[60] Anchoring Anchoring describes when people have a mental reference point with which they compare results to. For example, a person who anticipates that the weather on a particular day would be raining, but finds that on the day it is actually clear blue skies, would gain more utility from the pleasant weather because they anticipated that it would be bad.[61] Herd behavior This is a relatively simple bias that reflects the tendency of people to mimic what everyone else is doing and follow the general consensus. Framing effects People tend to choose differently depending on how the options are presented to them. People tend to have little control over their susceptibility to the framing effect, as often their choice-making process is based on intuition.[62] Biases and fallacies While heuristics are tactics or mental shortcuts to aid in the decision-making process, people are also affected by a number of biases and fallacies. Behavioral economics identifies a number of these biases that negatively affect decision making such as: Present bias Present bias reflects the human tendency to want rewards sooner. It describes people who are more likely to forego a greater payoff in the future in favour of receiving a smaller benefit sooner. An example of this is a smoker who is trying to quit. Although they know that in the future they will suffer health consequences, the immediate gain from the nicotine hit is more favourable to a person affected by present bias. Present bias is commonly split into people who are aware of their present bias (sophisticated) and those who are not (naive).[63] Gambler's fallacy The gambler's fallacy stems from law of small numbers.[64] It is the belief that an event that has occurred often in the past is less likely to occur in the future, despite the probability remaining constant. For example, if a coin had been flipped three times and turned up heads every single time, a person influenced by the gambler's fallacy would predict that the next one ought to be tails because of the abnormal number of heads flipped in the past, even though the probability of a heads occurring is still 50%.[65] Hot hand fallacy The hot hand fallacy is the opposite of the gambler's fallacy. It is the belief that an event that has occurred often in the past is more likely to occur again in the future such that the streak will continue. This fallacy is particularly common within sports. For example, if a football team has consistently won the last few games they have participated in, then it is often said that they are 'on form' and thus, it is expected that the football team will maintain their winning streak.[66] Narrative fallacy Narrative fallacy refers to when people use narratives to connect the dots between random events to make sense of arbitrary information. The term stems from Nassim Taleb's book The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. The narrative fallacy can be problematic as it can lead to individuals making false cause-effect relationships between events.[67] For example, a startup may get funding because investors are swayed by a narrative that sounds plausible, rather than by a more reasoned analysis of available evidence.[68] Loss aversion Loss aversion refers to the tendency to place greater weight on losses compared to equivalent gains. In other words, this means that when an individual receives a loss, this will cause their utility to decline more so than the same-sized gain.[69] This means that they are far more likely to try to assign a higher priority on avoiding losses than making investment gains. As a result, some investors might want a higher payout to compensate for losses. If the high payout is not likely, they might try to avoid losses altogether even if the investment's risk is acceptable from a rational standpoint.[70] Recency bias Recency bias is the belief that a particular outcome is more probable simply because it had just occurred. For example, if the previous one or two flips were heads, a person affected by recency bias would continue to predict that heads would be flipped.[71] Confirmation bias Confirmation bias is the tendency to prefer information consistent with one's beliefs and discount evidence inconsistent with them.[72] Familiarity bias Familiarity bias simply describes the tendency of people to return to what they know and are comfortable with. Familiarity bias discourages affected people from exploring new options and may limit their ability to find an optimal solution.[73] Status quo bias Status quo bias describes the tendency of people to keep things as they are. It is a particular aversion to change in favor of remaining comfortable with what is known.[74] Connected to this concept is the endowment effect, a theory that people value things more if they own them - they require more to give up an object than they would be willing to pay to acquire it.[75] |

概念 行動経済学は、人々が合理的で利己的であるという前提の誤りを研究することによって、伝統的な経済理論を改善または見直すことを目的としている。具体的に は、人々の経済的意思決定のバイアス、傾向、ヒューリスティクスを研究する。人民が良い選択をしているかどうか、より良い選択ができるように手助けができ るかどうかを判断するのに役立つ。意思決定の前にも後にも適用できる。 探索ヒューリスティクス 行動経済学では、選択肢を評価するための補助として探索ヒューリスティクスを提案している。これは、選択肢に関する情報を得るにはコストがかかるという事 実に動機づけられ、情報を探索することの効用を最大化することを目的としている。それぞれのヒューリスティックは単独で検索プロセスを説明する全体論的な ものではないが、意思決定プロセスではこれらのヒューリスティックを組み合わせて使用することができる。主な検索ヒューリスティックは3つある。 サティスフィキシング サティスフィカシングとは、検索には最低限必要なものがあり、それが満たされたら検索をやめるという考え方である。Satisficingの後、人格は最 も最適な選択肢(すなわち、効用が最も高い選択肢)を持たないかもしれないが、「十分に良い」選択肢を持つことになる。このヒューリスティックは、願望レ ベルが、要求を満たすような製品が存在しないようなレベルに設定されている場合、問題となる可能性がある。 指示認知 指示的認知は、人格が情報を調査する各機会を最後の機会として扱う検索ヒューリスティックである。各検索の結果に基づいて何をするかを示す偶発的な計画で はなく、指向的認知は、あと1回検索を行うべきかどうか、どのような代替案を調査すべきかだけを考える。 側面による消去法 満足と指示認知が選択肢を比較するのに対して、局面による消去法は、ある資質を比較する。消去法によるヒューリスティックを使う人格は、まず自分が探して いるものの中で最も重視する質を選び、願望レベルを設定する。これを繰り返すことで、検索を絞り込むことができる。つまり、2番目に重視する品質を特定 し、願望レベルを設定するのである。このヒューリスティックを使用すると、選択した資質の最低要件を満たさないため、選択肢は消去される[59]。 ヒューリスティックと認知的効果 検索以外にも、行動経済学者や心理学者は、人々の意思決定に影響を与えるヒューリスティックやその他の認知的効果を特定している。これらには以下が含まれ る: メンタル・アカウンティング メンタル・アカウンティングとは、特定の目的のために資源を配分する傾向のことである。メンタル・アカウンティングは、お金の出所や意図主義に基づいて、 お金をメンタル・アカウントとして知られる異なるカテゴリーに分ける行動バイアスである[60]。 アンカリング アンカリングとは、人々が結果を比較する精神的な基準点を持つことを指す。例えば、ある日の天候が雨であると予期していた人格が、実際には晴天の青空で あった場合、天候が悪いと予期していたため、快適な天候からより多くの効用を得ることになる[61]。 群畜行動 これは比較的単純なバイアスであり、人民が他の皆がやっていることを模倣し、一般的なコンセンサスに従う傾向を反映する。 フレーミング効果 人々は選択肢の提示の仕方によって異なる選択をする傾向がある。多くの場合、人々の選択プロセスは直感に基づいているため、フレーミング効果の影響を受け やすいことを人民はほとんどコントロールできない傾向がある[62]。 偏見と誤謬 ヒューリスティクスは意思決定プロセスを支援するための戦術や精神的近道であるが、人々もまた多くのバイアスや誤謬の影響を受けている。行動経済学は、意 思決定に悪影響を及ぼすこれらのバイアスを以下のようにいくつも特定している: 現在バイアス 現在バイアスは、報酬を早く欲しがる人間の傾向を反映している。このバイアスは、より小さな利益をより早く受け取るために、将来より大きな報酬を見送る可 能性が高い人々について述べている。この例は、禁煙しようとしている喫煙者である。将来、保健上の苦悩に見舞われることは分かっていても、ニコチンを摂取 することで得られる目先の利益の方が、現在バイアスの影響を受けている人格にとっては有利なのである。現在バイアスは一般的に、現在バイアスに気づいてい る人々(洗練された)と気づいていない人々(素朴な)に分けられる[63]。 ギャンブラーの誤謬 ギャンブラーの誤謬は、小数の法則に由来する[64]。これは、確率が一定であるにもかかわらず、過去に頻繁に起こった事象が将来起こる可能性は低いと考 えることである。例えば、コインを3回ひっくり返して、毎回表が出たとすると、ギャンブラーの誤謬に影響された人格は、表が出る確率がまだ50%であるに もかかわらず、過去に裏が出た回数が異常であるため、次は裏が出るはずだと予測する[65]。 ホットハンドの誤謬 ホットハンドの誤謬は、ギャンブラーの誤謬の反対である。ホットハンドの誤謬とは、ギャンブラーの誤謬の対極にあるもので、過去に頻繁に起こった出来事が 将来も起こる可能性が高く、その連鎖が続くと考えることである。この誤謬は、特にスポーツの世界でよく見られる。例えば、あるサッカーチームがここ数試合 常に勝利している場合、そのチームは「調子が良い」と言われることが多く、したがって、そのサッカーチームは連勝を維持すると予想される[66]。 物語の誤謬 物語の誤謬とは、人民が恣意的な情報の意味を理解するために、ランダムな出来事の点と点を結ぶために物語を使うことを指す。この用語は、ナシーム・タレブ の著書『ブラック・スワン:起こりえないことの衝撃』に由来する。例えば、新興企業が資金を得ることができるのは、投資家が利用可能な証拠をより理性的に 分析するのではなく、もっともらしく聞こえる物語に動かされるからかもしれない[68]。 損失回避 損失回避性とは、同等の利益と比較して損失をより重視する傾向を指す。言い換えれば、これは個人が損失を受けると、同規模の利益よりも効用の低下を引き起 こすことを意味する[69]。その結果、損失を補填するために高いペイアウトを望む投資家もいるかもしれない。高いペイアウトが期待できない場合、合理的 な見地から投資のリスクが許容できるとしても、損失を完全に回避しようとするかもしれない[70]。 再帰性バイアス 再帰性バイアスとは、個別主義とは、ある特定の結 果が発生したばかりであるという理由だけで、その結果 がより起こりやすいと考えることである。例えば、前の1回か2回がヘッドだった場合、再帰性バイアスの影響を受けた人格は、ヘッドが反転すると予測し続け る[71]。 確証バイアス 確証バイアスとは、自分の信念と一致する情報を好み、信念と矛盾する証拠を割り引く傾向のことである[72]。 馴れ合いバイアス 親近感バイアスとは、人民が自分の知っていること、慣れ親しんでいることに戻ろうとする傾向のことである。馴れ合いバイアスは、影響を受けた人々が新しい 選択肢を探索することを妨げ、最適解を見出す能力を制限する可能性がある[73]。 現状維持バイアス 現状維持バイアスとは、人民が物事を現状のまま維持しようとする傾向のことである。これは、既知のものに安住することを優先して変化を嫌う個別主義である [74]。 この概念と関連しているのが、人民は所有しているものにより価値を見出すという理論である保有効果である。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Behavioral_economics |

☆カーネマン、トベルスキー、セイラー

| ダ

ニエル・カーネマン(Daniel

Kahneman, 1934-2024) |

エ

イモス・トベルスキー(Amos

Tversky, 1937-1996) |

リ

チャード・H・セイラー

(Richard H. Thaler, 1945- ) |

| 1934 現イスラエルのテル・アヴィヴ

で生まれ、幼年時代をパリで過ごす |

1937 ハイファで生まれる |

|

| 1948 イスラエル独立直前のイギリス

委任統治領パレスチナに移住する |

1945 ニュージャージー州イーストオ

レンジで生まれる |

|

| 1954 エルサレムのヘブライ大学で心

理学を主、数学を従として学び卒業する(B.A.)。その後、イスラエル国防軍の心理学部門 1958 カリフォルニア大学バークレー校で博士号を得る勉強のために、アメリカに移る |

||

| 1961 カリフォルニア大学バークレー

校で博士号(心理学)を取得 1961- ヘブライ大学の講師 |

1961 ヘブライ大学(エルサレム)に

おいてB.A.を取得 1965 ミシガン大学においてPh.D. 1966- ヘブライ大学講師(-1969) 1969 ヘブライ大学教授 |

1967 ケース・ウェスタン・リザーブ

大学卒業 |

| 1972-1973 スタンフォード大学

行動科学先端研究センター(Center

for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences)で研究 -1977 ヘブライ大学の講師を務める。 1978- ブリティッシュコロンビア大学の心理学教授 |

1971 スタンフォード大学教授 |

1970-1978《イー

コン[正統派]の経済学に疑問を抱く》 1970 ロチェスター大学で修士号 1974 ロチェスター大学で博士号 1974 ロチェスター大学助教授 1975-1988《セルフコントロール問題に取り組む》 |

| 1986- カリフォルニア大学バーク

レー校の教授 |

1985 ヨーテボリ大学(スウェーデ

ン)においてPh.D 1987 ニューヨーク州立大学においてPh.Dを取得 |

1979-1985《メン

タル・アカウンティングで行動を読み解く》 1980 コーネル大学准教授 1983-2003《効率的市場仮説に抗う》 1984-1985《カーネマンの研究室に入り浸る》 1986 コーネル大学ジョンソン経営大学院教授 1986-1994《経済学者と闘う》 |

| 1993- プリンストン大学の教授

(Eugene Higgins Professor of

Psychology)、およびウッドロー・ウィルソン・スクールの心理学・公的行動の教授(Professor of Psychology and

Public Affairs) |

1996 スタンフォードで死去する

(59歳) |

1986-1994《経済

学者と闘う》 1995 シカゴ大学教授 1995-現在《シカゴ大学に赴任する》 |

| 2002 ノーベル経済学賞受賞 2007 プリンストン大学名誉教授、およびウッドロー・ウィルソン・スクール名誉教授 |

2004-現在《意思決定

をナッジする》 |

|

| 2016 行動経済学の逆襲 / リチャード・セイラー著 ; 遠藤真美訳, 東京 :

早川書房 , 2016 2017 ノーベル経済学賞 |

||

| 2024 3月27日スイスで死去 |

リチャード・セイラー『不品行にふるま

う:行動経済学をつくる!』の目次

第1部 イーコン(econ, Homo

economics)の経済学に疑問を抱く 1970〜78年

第2部 メ

ンタル・アカウンティングで行動を読み解く 1979〜85年

第3部 セ

ルフコントロール問題に取り組む 1975〜88年

(幕間)

第7部 シカゴ大学に赴任する 1995年〜現在

第8部 意思決定をナッジする 2004年〜現在

XX.今後の経済学に期待すること

【設問】

1.ダニエル・カーネマン、エイモス・ト ベルスキー、リチャード・H・セイラーの3人の人たちについて調べてみよう。

2.この本の全編を読んで、なぜイーコン (econ, Homo economics)が、経済学という学問の世界を席巻するようになったのかについて自分なりに説明してみよう。

++++

イーコン(econ, Homo economics)の世界(項目は、井堀利宏『大学4年間の経済学が10時間でざっと学べる』角川文庫、2018年、より)

リンク

文献

Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Do not paste, but

[Re]Think our message for all undergraduate

students!!!

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099