明白なる運命

Manifest destiny, マニュフェスト・ディスティニー, 植民を正当化する言説

☆マニフェスト・デスティニー(Manifest destiny)

とは、19世紀アメリカにおける帝国主義的信念である。アメリカ入植者が北米大陸を西へ拡大することが運命づけられており、この信念は明白(「マニフェス

ト」)かつ確実(「デスティニー」)であるというものだ。この信念はアメリカの例外主義、ロマン主義的ナショナリズム、白人ナショナリズムに根ざしており

[2][3][4]、共和主義とアメリカ的価値観の必然的な拡散を暗示している。[5] これはアメリカ帝国主義の最も初期の表現の一つである。[6][7][8]

歴史家ウィリアム・アール・ウィークスによれば、この概念の背景には三つの基本原理があった。[5]

(1)アメリカ合衆国が独自の道徳的優位性を持つという前提。(2)

共和制政府、より広くは「アメリカン・ウェイ・オブ・ライフ」の普及によって世界を救済するという使命の主張。(3)

この使命を成功させるという、国家の神によって定められた運命への信仰。

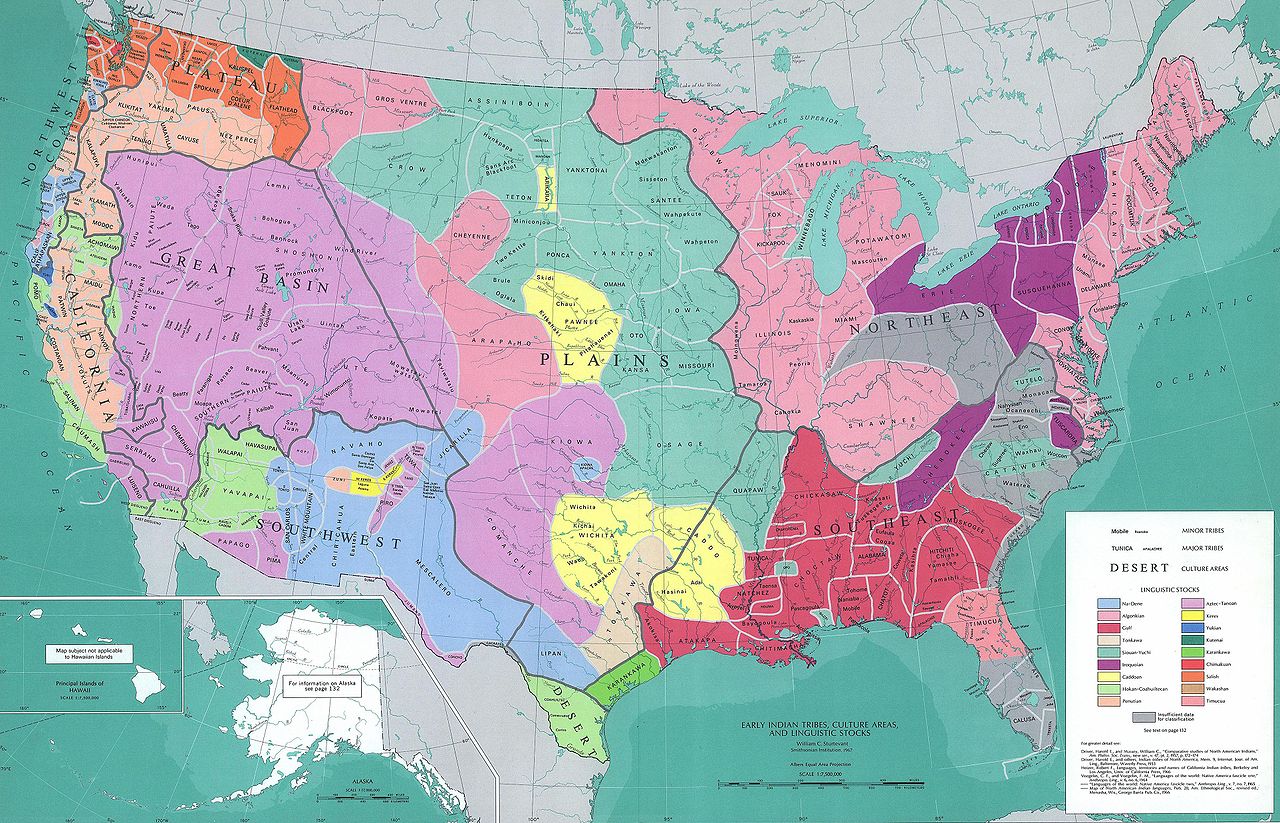

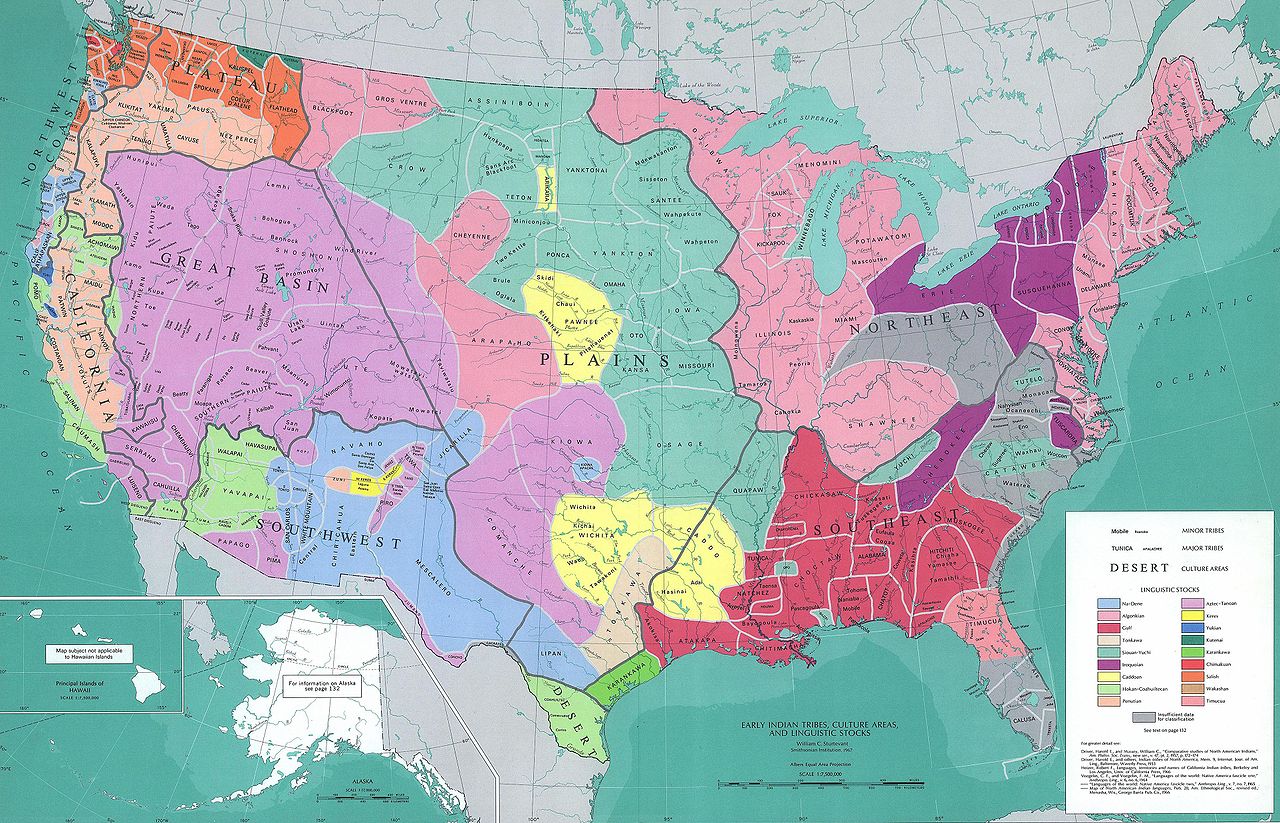

マニフェスト・デスティニーは政治において深刻な分裂を引き起こし、新たな州や領土における奴隷制を巡る絶え間ない対立を生んだ[9]。また、先住アメリ

カ人の入植者による植民地的な追放[10]や、当時のアメリカ大陸における国境の西側への領土併合とも関連している。この概念は1844年の大統領選挙に

おける主要な争点の一つとなり、民主党が勝利した。その1年以内に「マニフェスト・デスティニー」という語が造語された。[6][11]

マニフェスト・デスティニーの概念は、民主党によって1846年のオレゴン境界紛争や1845年のテキサス併合(奴隷州として)を正当化する根拠として用

いられ、1846年の米墨戦争へと発展した。これに対し、ホイッグ党員の大多数と著名な共和党員(エイブラハム・リンカーンやユリシーズ・S・グラントな

ど)はこの概念を拒否し、これらの行動に反対する運動を展開した[12][13][14]。1843年までに、元大統領ジョン・クインシー・アダムズ(当

初はマニフェスト・デスティニーの根底にある概念の主要な支持者だった)は考えを変え、テキサスにおける奴隷制の拡大を意味するとして拡張主義を否定し

た。[6] ユリシーズ・S・グラントは米墨戦争に従軍し、これを「強国が弱国に対して行った最も不当な戦争の一つ」と断じて非難した。[13]

南北戦争後、アメリカは1867年にアラスカを獲得した。1890年代には共和党のウィリアム・マッキンリー大統領がハワイ、フィリピン、プエルトリコ、

グアム、アメリカ領サモアを併合した。1898年の米西戦争は論争を呼び、帝国主義は1900年のアメリカ大統領選挙における主要な争点となった。歴史家

ダニエル・ウォーカー・ハウは「アメリカの帝国主義は国民的合意を反映したものではなく、国家政治内部で激しい反対を引き起こした」と総括している。

[6][15]

| Manifest destiny was

the imperialist belief in the 19th-century United States that American

settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and

that this belief was both obvious ("manifest") and certain ("destiny").

The belief is rooted in American exceptionalism, romantic nationalism,

and white nationalism,[2][3][4] implying the inevitable spread of

republicanism and the American way.[5] It is one of the earliest

expressions of American imperialism.[6][7][8] According to historian William Earl Weeks, there were three basic tenets behind the concept:[5] The assumption of the unique moral virtue of the United States. The assertion of its mission to redeem the world by the spread of republican government and more generally the "American way of life". The faith in the nation's divinely ordained destiny to succeed in this mission. Manifest destiny remained heavily divisive in politics, causing constant conflict with regards to slavery in these new states and territories.[9] It is also associated with the settler-colonial displacement of Indigenous Americans[10] and the annexation of lands to the west of the United States borders at the time on the continent. The concept became one of several major campaign issues during the 1844 presidential election, where the Democratic Party won and the phrase "Manifest Destiny" was coined within a year.[6][11] The concept of manifest destiny was used by Democrats to justify the 1846 Oregon boundary dispute and the 1845 annexation of Texas as a slave state, culminating in the 1846 Mexican–American War. In contrast, the large majority of Whigs and prominent Republicans (such as Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant) rejected the concept and campaigned against these actions.[12][13][14] By 1843, former U.S. president John Quincy Adams, originally a major supporter of the concept underlying manifest destiny, had changed his mind and repudiated expansionism because it meant the expansion of slavery in Texas.[6] Ulysses S. Grant served in and condemned the Mexican–American War, declaring it "one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation".[13] After the American Civil War, the U.S. acquired Alaska in 1867. In the 1890s, Republican president William McKinley annexed Hawaii, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Guam, and American Samoa. The 1898 Spanish–American War was controversial and imperialism became a major issue in the 1900 United States presidential election. Historian Daniel Walker Howe summarizes that "American imperialism did not represent an American consensus; it provoked bitter dissent within the national polity".[6][15] |

マニフェスト・デスティニー(Manifest destiny)とは、19世紀アメリカにおける帝国主義的

信念である。アメリカ入植者が北米大陸を西へ拡大することが運命づけられており、この信念は明白(「マニフェスト」)かつ確実(「デスティニー」)である

というものだ。この信念はアメリカの例外主義、ロマン主義的ナショナリズム、白人ナショナリズムに根ざしており[2][3][4]、共和主義とアメリカ的

価値観の必然的な拡散を暗示している。[5] これはアメリカ帝国主義の最も初期の表現の一つである。[6][7][8] 歴史家ウィリアム・アール・ウィークスによれば、この概念の背景には三つの基本原理があった。[5] アメリカ合衆国が独自の道徳的優位性を持つという前提。 共和制政府、より広くは「アメリカン・ウェイ・オブ・ライフ」の普及によって世界を救済するという使命の主張。 この使命を成功させるという、国家の神によって定められた運命への信仰。 マニフェスト・デスティニーは政治において深刻な分裂を引き起こし、新たな州や領土における奴隷制を巡る絶え間ない対立を生んだ[9]。また、先住アメリ カ人の入植者による植民地的な追放[10]や、当時のアメリカ大陸における国境の西側への領土併合とも関連している。この概念は1844年の大統領選挙に おける主要な争点の一つとなり、民主党が勝利した。その1年以内に「マニフェスト・デスティニー」という語が造語された。[6][11] マニフェスト・デスティニーの概念は、民主党によって1846年のオレゴン境界紛争や1845年のテキサス併合(奴隷州として)を正当化する根拠として用 いられ、1846年の米墨戦争へと発展した。これに対し、ホイッグ党員の大多数と著名な共和党員(エイブラハム・リンカーンやユリシーズ・S・グラントな ど)はこの概念を拒否し、これらの行動に反対する運動を展開した[12][13][14]。1843年までに、元大統領ジョン・クインシー・アダムズ(当 初はマニフェスト・デスティニーの根底にある概念の主要な支持者だった)は考えを変え、テキサスにおける奴隷制の拡大を意味するとして拡張主義を否定し た。[6] ユリシーズ・S・グラントは米墨戦争に従軍し、これを「強国が弱国に対して行った最も不当な戦争の一つ」と断じて非難した。[13] 南北戦争後、アメリカは1867年にアラスカを獲得した。1890年代には共和党のウィリアム・マッキンリー大統領がハワイ、フィリピン、プエルトリコ、 グアム、アメリカ領サモアを併合した。1898年の米西戦争は論争を呼び、帝国主義は1900年のアメリカ大統領選挙における主要な争点となった。歴史家 ダニエル・ウォーカー・ハウは「アメリカの帝国主義は国民的合意を反映したものではなく、国家政治内部で激しい反対を引き起こした」と総括している。 [6][15] |

American Progress (1872) by John Gast is an allegorical representation of the modernization of the new west. Columbia, a personification of the United States, is shown leading civilization westward with the American settlers. She is shown bringing light from east to west, stringing telegraph wire, holding a school book, and highlighting different stages of economic activity and evolving forms of transportation.[1] On the left, Indigenous Americans are displaced from their ancestral homeland. |

ジョン・ガスト作『アメリカの進歩』(1872年)は、新たな西部の近代化を寓意的に表現した作品である。アメリカ合衆国を擬人化したコロンビアは、入植 者たちと共に文明を西へと導く姿で描かれている。彼女は東から西へ光をもたらし、電信線を張り巡らせ、教科書を手にし、経済活動の様々な段階や進化する交 通手段を強調している[1]。左側では、先住民が祖先の故郷から追いやられている。 |

| Context There was never a set of principles defining manifest destiny; it was always a general idea rather than a specific policy made with a motto. Ill-defined but keenly felt, manifest destiny was an expression of conviction in the morality and value of expansionism that complemented other popular ideas of the era, including American exceptionalism and Romantic nationalism. Andrew Jackson, who spoke of "extending the area of freedom", typified the conflation of America's potential greatness, the nation's budding sense of Romantic self-identity, and its expansion.[16][17] Yet Jackson was not the only president to elaborate on the principles underlying manifest destiny. Owing in part to the lack of a definitive narrative outlining its rationale, proponents offered divergent or seemingly conflicting viewpoints. While many writers focused primarily upon American expansionism, be it into Mexico or across the Pacific, others saw the term as a call to example. Without an agreed-upon interpretation, much less an elaborated political philosophy, these conflicting views of America's destiny were never resolved. This variety of possible meanings was summed up by Ernest Lee Tuveson: "A vast complex of ideas, policies, and actions is comprehended under the phrase 'Manifest Destiny'. They are not, as we should expect, all compatible, nor do they come from any one source."[18] |

文脈 マニフェスト・デスティニーを定義する一連の原則は存在しなかった。それは、スローガンを掲げた具体的な政策というよりも、常に一般的な考えであった。定 義は曖昧だが、強く感じられたマニフェスト・デスティニーは、拡大主義の道徳性と価値に対する確信の表現であり、アメリカの例外主義やロマン主義的ナショ ナリズムなど、当時の他の大衆的な思想を補完するものであった。「自由の領域を拡大する」と語ったアンドルー・ジャクソンは、アメリカの潜在的な偉大さ、 国家の芽生えたロマン主義的自己認識、そしてその拡大を融合した典型的な人物であった[16]。[17] しかし、マニフェスト・デスティニーの根底にある原則について詳しく述べた大統領は、ジャクソンだけではありませんでした。その理論的根拠を概説する決定 的な物語が欠けていたこともあり、支持者たちは、異なる、あるいは一見矛盾しているように見える見解を示しました。多くの著者は、メキシコへの、あるいは 太平洋を越えたアメリカの拡張主義に主に焦点を当てましたが、他の著者は、この用語を模範となるよう呼びかけるものとして捉えました。合意された解釈はお ろか、体系化された政治哲学すら存在しなかったため、アメリカ運命論をめぐるこうした対立は決して解決されなかった。この多様な解釈の可能性をアーネス ト・リー・トゥベソンはこう総括している。「『マニフェスト・デスティニー』という語句の下には、膨大な思想・政策・行動の複合体が包含されている。それ らは当然ながら互いに整合するものではなく、単一の源泉から生まれたものでもない」[18] |

| Etymology Most historians credit the conservative newspaper editor and future propagandist for the Confederacy, John O'Sullivan, with coining the term manifest destiny in 1845.[11] However, other historians suggest the unsigned editorial titled "Annexation" in which it first appeared was written by journalist and annexation advocate Jane Cazneau.[19][20]  John L. O'Sullivan, sketched in 1874, was an influential columnist as a young man, but he is now generally remembered only for his use of the phrase "manifest destiny" to advocate the annexation of Texas and Oregon. O'Sullivan was an influential advocate for Jacksonian democracy, described by Julian Hawthorne as "always full of grand and world-embracing schemes".[21] O'Sullivan wrote an article in 1839 that, while not using the term "manifest destiny", did predict a "divine destiny" for the United States based upon values such as equality, rights of conscience, and personal enfranchisement "to establish on earth the moral dignity and salvation of man".[22] This destiny was not explicitly territorial, but O'Sullivan predicted that the United States would be one of a "Union of many Republics" sharing those values.[23] Six years later, in 1845, O'Sullivan wrote another essay titled "Annexation" in the Democratic Review,[24] in which he first used the phrase manifest destiny.[25] In this article he urged the U.S. to annex the Republic of Texas,[26] not only because Texas desired this, but because it was "our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions".[27] Overcoming Whig opposition, Democrats annexed Texas in 1845. O'Sullivan's first usage of the phrase "manifest destiny" attracted little attention.[28] O'Sullivan's second use of the phrase became extremely influential. On December 27, 1845, in his newspaper the New York Morning News, O'Sullivan addressed the ongoing boundary dispute with Britain. O'Sullivan argued that the United States had the right to claim "the whole of Oregon": And that claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.[29] That is, O'Sullivan believed that Providence had given the United States a mission to spread republican democracy ("the great experiment of liberty"). Because the British government would not spread democracy, thought O'Sullivan, British claims to the territory should be overruled. O'Sullivan believed that manifest destiny was a moral ideal (a "higher law") that superseded other considerations.[30] O'Sullivan's original conception of manifest destiny was not a call for territorial expansion by force. He believed that the expansion of the United States would happen without the direction of the U.S. government or the involvement of the military. After Americans immigrated to new regions, they would set up new democratic governments, and then seek admission to the United States, as Texas had done. In 1845, O'Sullivan predicted that California would follow this pattern next, and that even Canada would eventually request annexation as well. He was critical of the Mexican–American War in 1846, although he came to believe that the outcome would be beneficial to both countries.[31] Ironically, O'Sullivan's term became popular only after it was criticized by Whig opponents of the Polk administration. Whigs denounced manifest destiny, arguing, "that the designers and supporters of schemes of conquest, to be carried on by this government, are engaged in treason to our Constitution and Declaration of Rights, giving aid and comfort to the enemies of republicanism, in that they are advocating and preaching the doctrine of the right of conquest".[32] On January 3, 1846, in a speech Representative Robert Winthrop used the term for the first time in Congress stating: There is one element in our title [to Oregon], however, which I confess that I have not named, and to which I may not have done entire justice. I mean that new revelation of right which has been designated as the right of our manifest destiny to spread over this whole continent. It has been openly avowed in a leading Administration journal that this, after all, is our best and strongest title-one so clear, so pre-eminent, and so indisputable, that if Great Britain had all our other titles in addition to her own, they would weigh nothing against it. The right of our manifest destiny! There is a right for a new chapter in the law of nations; or rather, in the special laws of our own country; for I suppose the right of a manifest destiny to spread will not be admitted to exist in any nation except the universal Yankee nation![33] "[34] Winthrop was the first in a long line of critics who suggested that advocates of manifest destiny were citing "Divine Providence" for justification of actions that were motivated by chauvinism and self-interest. Despite this criticism, expansionists embraced the phrase, which caught on so quickly that its origin was soon forgotten.[35] |

語源 多くの歴史家は、保守派新聞編集者であり後に南軍の宣伝家となるジョン・オサリバンが1845年に「マニフェスト・デスティニー」という用語を造語したと 認めている[11]。しかし他の歴史家は、この言葉が初めて登場した無署名の社説「併合」の執筆者は、ジャーナリストで併合支持者のジェーン・カズノーで あったと示唆している[19]。[20]  1874年に描かれたジョン・L・オサリバンは、若き日に影響力あるコラムニストであったが、現在では主に「マニフェスト・デスティニー」という語を用いてテキサスとオレゴンの併合を主張したことのみ記憶されている。 オサリバンはジャクソン民主主義の有力な提唱者であり、ジュリアン・ホーソーンは彼を「常に壮大で世界を包み込むような構想に満ちていた」と評している。 [21] オサリバンは1839年に「明白な運命」という用語は使わなかったものの、平等、良心の権利、個人の参政権といった価値観に基づく「神聖な運命」を米国に 予言する記事を執筆した。その目的は「地上に人間の道徳的尊厳と救済を確立する」ことだった。[22] この運命は明示的に領土的ではなかったが、オサリバンは米国がそれらの価値観を共有する「多くの共和国の連合」の一員となると予測した。[23] 6年後の1845年、オサリバンは『民主主義評論』に「併合」と題する別の論文を寄稿した。[24] ここで彼は初めて「マニフェスト・デスティニー」という語句を用いた。[25] この論文で彼は、テキサス共和国を併合するよう米国に強く訴えた[26]。その理由はテキサス側が併合を望んでいたからだけでなく、「神が我々に与えた大 陸全体に広がり、年々増え続ける数百万の国民が自由に発展する」ことが「我々の明白な運命」だからだと述べた[27]。ホイッグ党の反対を押し切り、民主 党は1845年にテキサスを併合した。オサリバンによる「明白な運命」という語の初出は、ほとんど注目されなかった。[28] オサリバンがこの言葉を二度目に用いた時、それは極めて大きな影響力を持つこととなった。1845年12月27日、自身の新聞『ニューヨーク・モーニン グ・ニュース』において、オサリバンは英国との継続中の境界紛争について論じた。オサリバンは、アメリカ合衆国が「オレゴン全域」を主張する権利を有する と主張した: そしてその主張は、我々の明白な運命の権利によるものだ。すなわち、神が我々に授けた大陸全体を覆い尽くし、所有する権利である。それは自由という偉大な実験と、我々に託された連邦制による自治を発展させるためだ。[29] つまりオサリバンは、神がアメリカに共和制民主主義(「自由という偉大な実験」)を広める使命を与えたと信じていた。英国政府は民主主義を広めようとしな いから、英国の領有権主張は退けられるべきだと考えたのだ。オサリバンはマニフェスト・デスティニーを、他の考慮事項を上回る道徳的理想(「より高い 法」)と見なしていた。[30] オサリバンのマニフェスト・デスティニーの本来の構想は、武力による領土拡張の呼びかけではなかった。彼は、アメリカ合衆国の拡大は、アメリカ政府の指示 や軍隊の関与なしに起こるものと考えていた。アメリカ人が新たな地域に移住すると、彼らは新たな民主的政府を樹立し、テキサス州がそうしたように合衆国へ の加盟を求めるだろう。1845年、オサリバンはカリフォルニア州が次にこのパターンに従うと予測し、最終的にはカナダでさえ併合を要請すると述べた。彼 は1846年の米墨戦争を批判したが、結果的に両国にとって有益になると考えるようになった。[31] 皮肉なことに、オサリバンのこの用語が広く知られるようになったのは、ポーク政権に反対するホイッグ党員によって批判された後だった。ホイッグ党はマニ フェスト・デスティニーを非難し、「この政府によって遂行される征服計画の立案者や支持者は、征服の権利という教義を提唱し説くことで、共和主義の敵に援 助と慰めを与え、我々の憲法と権利宣言に対する反逆行為に手を染めている」と主張した。[32] 1846年1月3日、ロバート・ウィンスロップ下院議員が議会で初めてこの用語を使用し、次のように述べた: しかし我々の(オレゴンに対する)権利には、私がまだ言及しておらず、十分に正当性を認められていない要素が一つある。すなわち、この大陸全体に広がって いく我々の明白なる運命の権利と称される、新たな権利の啓示である。主要な政権系新聞は公然と、結局のところこれが我々の最も優れ強固な権利であると宣言 している。あまりに明白で、卓越し、議論の余地がないため、仮に英国が自国の権利に加え我々の他の全ての権利を掌握したとしても、これに比べれば無に等し いと。我々の明白なる運命の権利だ!これは国際法の新たな章を開く権利だ。いや、むしろ我が国固有の特別法の権利だ。なぜなら、拡大する明白な運命の権利 など、普遍的なヤンキー国家以外のいかなる国にも認められないだろうからな![33] 「[34] ウィンソープは、マニフェスト・デスティニーの擁護者たちが、自国中心主義と利己主義に動機づけられた行動を正当化するために『神の摂理』を引用している と示唆した、数多くの批判者たちの先駆けであった。この批判にもかかわらず、拡張主義者たちはこの言葉を歓迎し、その起源はすぐに忘れ去られるほど急速に 広まった。[35] |

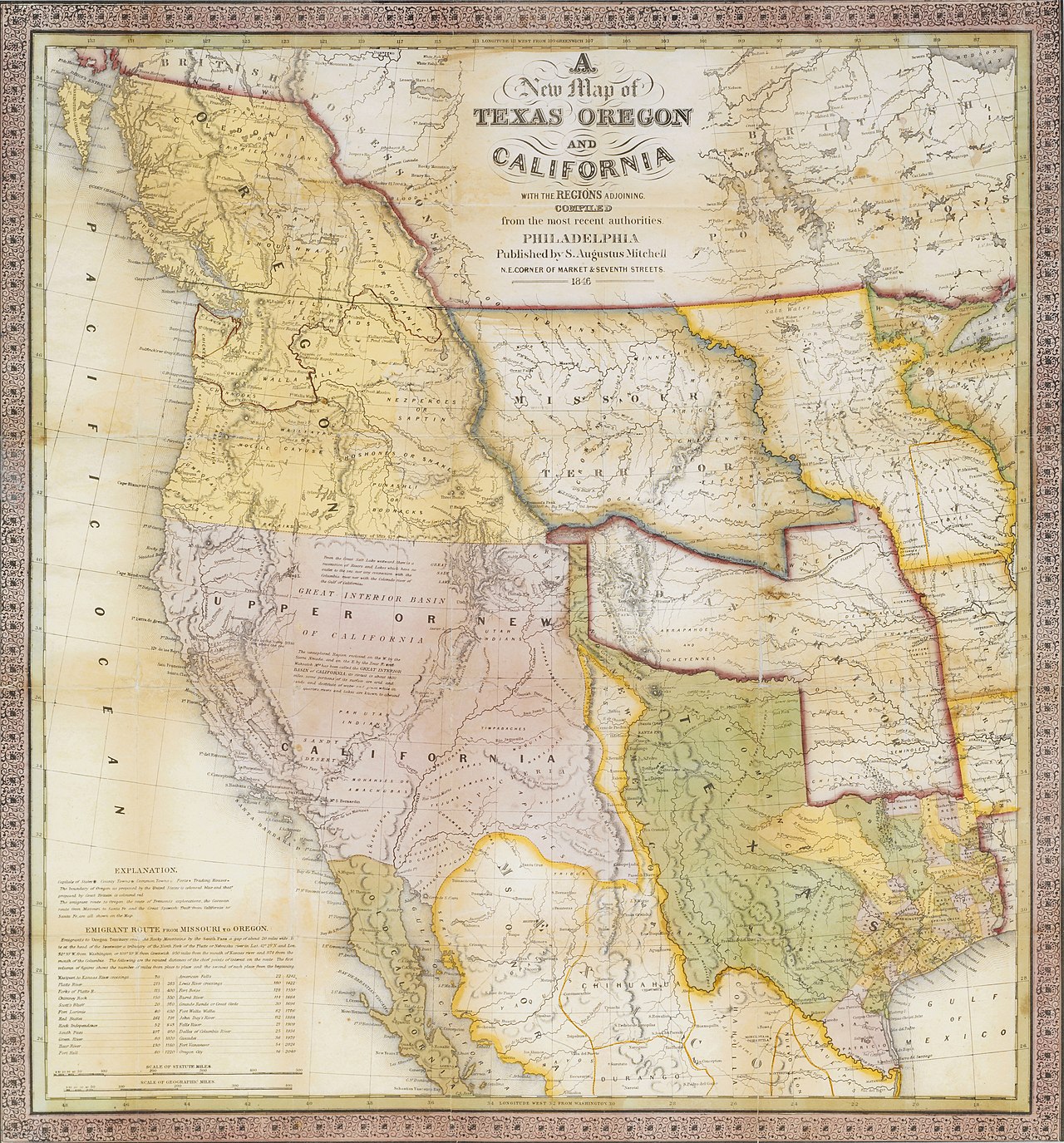

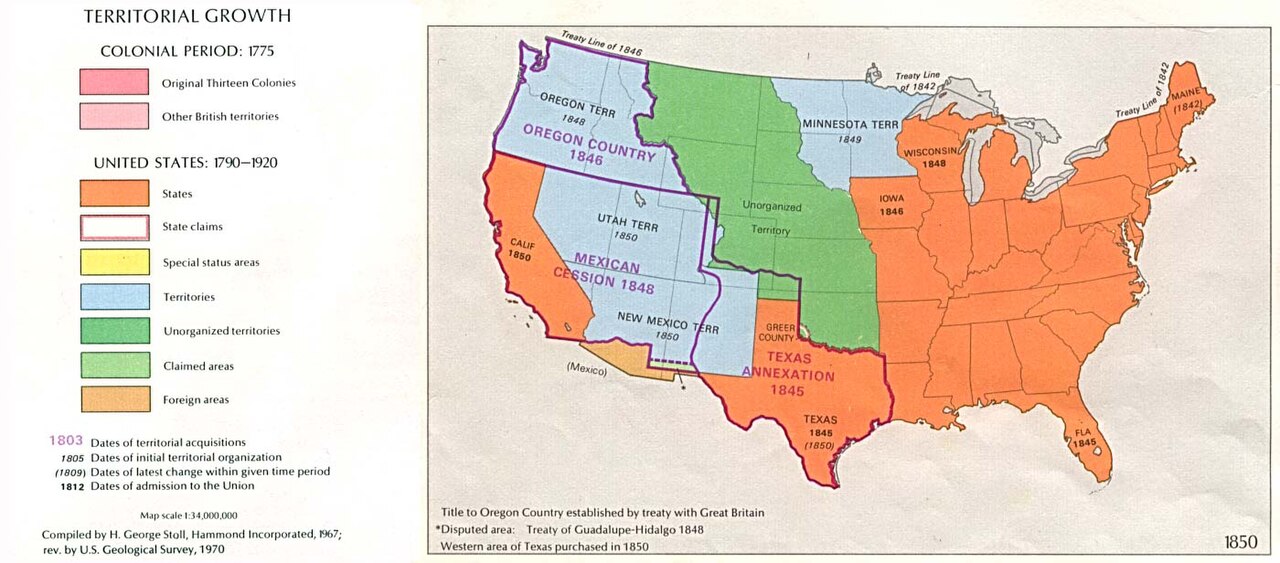

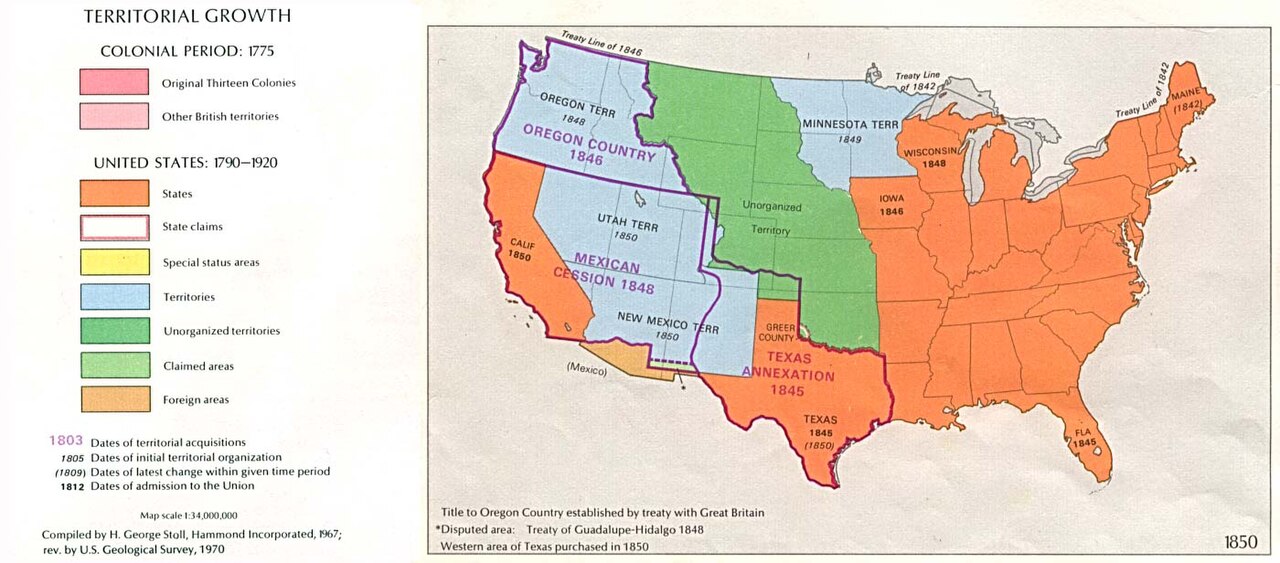

Themes and influences A New Map of Texas, Oregon, and California, Samuel Augustus Mitchell, 1846 Historian Frederick Merk wrote in 1963 that the concept of manifest destiny was born out of "a sense of mission to redeem the Old World by high example ... generated by the potentialities of a new earth for building a new heaven". Merk also states that manifest destiny was a heavily contested concept within the nation: From the outset Manifest Destiny—vast in program, in its sense of continentalism—was slight in support. It lacked national, sectional, or party following commensurate with its magnitude. The reason was it did not reflect the national spirit. The thesis that it embodied nationalism, found in much historical writing, is backed by little real supporting evidence.[6] A possible influence is racial predominance, namely the idea that the American Anglo-Saxon race was "separate, innately superior" and "destined to bring good government, commercial prosperity and Christianity to the American continents and the world". Author Reginald Horsman wrote in 1981, this view also held that "inferior races were doomed to subordinate status or extinction." and that this was used to justify "the enslavement of the blacks and the expulsion and possible extermination of the Indians".[36] The origin of the first theme, later known as American exceptionalism, was often traced to America's Puritan heritage, particularly John Winthrop's famous "City upon a Hill" sermon of 1630, in which he called for the establishment of a virtuous community that would be a shining example to the Old World.[37] In his influential 1776 pamphlet Common Sense, Thomas Paine echoed this notion, arguing that the American Revolution provided an opportunity to create a new, better society: We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand... Many Americans agreed with Paine, and came to believe that the United States' virtue was a result of its special experiment in freedom and democracy. Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to James Monroe, wrote, "it is impossible not to look forward to distant times when our rapid multiplication will expand itself beyond those limits, and cover the whole northern, if not the southern continent."[38] To Americans in the decades that followed their proclaimed freedom for mankind, embodied in the Declaration of Independence, could only be described as the inauguration of "a new time scale" because the world would look back and define history as events that took place before, and after, the Declaration of Independence. It followed that Americans owed to the world an obligation to expand and preserve these beliefs.[39] The second theme's origination is less precise. A popular expression of America's mission was elaborated by President Abraham Lincoln's description in his December 1, 1862, message to Congress. He described the United States as "the last, best hope of Earth". The "mission" of the United States was further elaborated during Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, in which he interpreted the American Civil War as a struggle to determine if any nation with democratic ideals could survive; this has been called by historian Robert Johannsen "the most enduring statement of America's Manifest Destiny and mission".[40] The third theme can be viewed as a natural outgrowth of the belief that God had a direct influence in the foundation and further actions of the United States. Political scientist and historian Clinton Rossiter described this view as summing "that God, at the proper stage in the march of history, called forth certain hardy souls from the old and privilege-ridden nations ... and that in bestowing his grace He also bestowed a peculiar responsibility". Americans presupposed that they were not only divinely elected to maintain the North American continent, but also to "spread abroad the fundamental principles stated in the Bill of Rights".[41] In many cases this meant neighboring colonial holdings and countries were seen as obstacles rather than the destiny God had provided the United States. Faragher's 1997 analysis of the political polarization between the Democratic Party and the Whig Party is that: Most Democrats were wholehearted supporters of expansion, whereas many Whigs (especially in the North) were opposed. Whigs welcomed most of the changes wrought by industrialization but advocated strong government policies that would guide growth and development within the country's existing boundaries; they feared (correctly) that expansion raised a contentious issue, the extension of slavery to the territories. On the other hand, many Democrats feared industrialization the Whigs welcomed... For many Democrats, the answer to the nation's social ills was to continue to follow Thomas Jefferson's vision of establishing agriculture in the new territories to counterbalance industrialization.[9] Two Native American writers have recently tried to link some of the themes of manifest destiny to the original ideology of the 15th-century decree of the Doctrine of Christian Discovery.[42] Nick Estes (a Lakota) links the 15th-century Catholic doctrine of distinguishing Christians from non-Christians in the expansion of European nations.[42] Estes and international jurist Tonya Gonnella Frichner (of the Onondaga Nation) further link the doctrine of discovery to Johnson v. McIntosh and frame their arguments on the correlation between manifest destiny and Doctrine of Christian Discovery by using the statement made by Chief Justice John Marshall during the case, as he "spelled out the rights of the United states to Indigenous lands" and drew upon the Doctrine of Christian Discovery for his statement.[42][43] Marshall ruled that "indigenous peoples possess 'occupancy' rights, meaning their lands could be taken by the powers of 'discovery'".[43] Frichner explains that "The newly formed United States needed to manufacture an American Indian political identity and concept of Indian land that would open the way for united states and westward colonial expansion."[43] In this way, manifest destiny was inspired by the original European colonization of the Americas, and it excuses U.S. violence against Indigenous Nations.[42] According to historian Dorceta Taylor: "Minorities are not usually chronicled as explorers or environmental activists, yet the historical records show that they were a part of expeditions, resided and worked on the frontier, founded towns, and were educators and entrepreneurs. In short, people of color were very important actors in westward expansion."[44] The desire for trade with China and other Asian countries was another ground for expansionism, with Americans seeing prospects of westward contact with Asia as fulfilling long-held Western hopes of finding new routes to Asia, and perceiving the Pacific as less unruly and dominated by Old World conflicts than the Atlantic and therefore a more inviting area for the new nation to expand its influence in.[45] |

テーマと影響 テキサス、オレゴン、カリフォルニアの新しい地図、サミュエル・オーガスタス・ミッチェル、1846年 歴史家のフレデリック・マークは1963年に、マニフェスト・デスティニーの概念は「新しい天国を築くための新しい地球の可能性によって生み出された、高 い模範によって旧世界を救うという使命感」から生まれたと書いている。マークはまた、マニフェスト・デスティニーは国内で激しく議論された概念であったと 述べている。 当初から、マニフェスト・デスティニーは、その大陸主義的な意味合いにおいて、その規模の割に支持はわずかであった。その規模に見合った、全国的、地域 的、あるいは政党的な支持を欠いていた。その理由は、それが国民精神を反映していなかったためである。多くの歴史書に見られる、それがナショナリズムを体 現していたという説は、実際の裏付けとなる証拠がほとんどない。[6] 影響の可能性として人種的優越性がある。すなわち、アメリカのアングロサクソン人種は「別個で生来的に優れている」という思想であり、「アメリカ大陸と世 界に良き統治、商業的繁栄、キリスト教をもたらす運命にある」という考えだ。著者レジナルド・ホースマンは1981年にこう記している。この見解は「劣等 民族は従属的地位か絶滅を運命づけられている」とも主張し、これが「黒人の奴隷化とインディアンの追放・絶滅の可能性」を正当化する根拠として用いられた と。[36] この最初のテーマ(後にアメリカ例外主義として知られる)の起源は、しばしばアメリカのピューリタン的遺産、特に1630年のジョン・ウィンスロップの有 名な「丘の上の都」説教に遡るとされる。彼はこの説教で、旧世界に輝く模範となる徳の高い共同体の設立を訴えた。[37] トーマス・ペインは1776年の影響力ある小冊子『コモン・センス』でこの考えを支持し、アメリカ独立革命が新たなより良い社会を創る機会を提供すると論 じた: 我々には世界を再構築する力が備わっている。ノアの時代以来、現在に匹敵する状況はかつてなかった。新世界の誕生が目前に迫っている... 多くのアメリカ人はペインに同意し、合衆国の美徳は自由と民主主義という特別な実験の結果だと信じるようになった。トマス・ジェファーソンはジェームズ・ モンローへの書簡でこう記している。「我々の急速な人口増加がやがてその限界を超え、南大陸でなくとも北大陸全体を覆う遠い未来を、見据えずにはいられな い」 [38] 独立宣言に具現化された人類のための自由を宣言した後の数十年間、アメリカ人にとってそれは「新たな時間軸」の始まりとしか言いようがなかった。世界は独 立宣言を境に、その前と後の出来事で歴史を定義するようになるからだ。したがってアメリカ人は、これらの信念を広め守る義務を世界に負っている。[39] 第二のテーマの起源はより曖昧である。アメリカの使命を表現した有名な言葉は、エイブラハム・リンカーン大統領が1862年12月1日に議会へ送ったメッ セージの中で詳述された。彼はアメリカ合衆国を「地球の最後の、最高の希望」と表現した。リンカーンのゲティスバーグ演説では、この「使命」がさらに展開 された。彼は南北戦争を「民主主義の理想を掲げる国家が存続できるか否かを決する闘い」と解釈した。歴史家ロバート・ヨハンセンはこれを「アメリカの明白 な運命と使命に関する最も永続的な声明」と呼んでいる。[40] 第三のテーマは、神が合衆国の建国とその後の一連の行動に直接影響を与えたという信念から自然に派生したものと見なせる。政治学者であり歴史家でもあるク リントン・ロシターは、この見解を「神は歴史の歩みの適切な段階で、古く特権に満ちた国々から特定の不屈の魂を呼び起こした…そして神の恩寵を授けること で、神はまた特別な責任も授けた」と要約した。アメリカ人は、自分たちが北米大陸を維持するために神に選ばれただけでなく、「権利章典に記された基本原則 を世界に広める」使命も帯びていると前提していた。[41] 多くの場合、これは近隣の植民地や諸国が、神がアメリカに与えた運命の妨げと見なされることを意味した。 ファラガーが1997年に民主党とホイッグ党の政治的分極化について分析した内容は次の通りだ: 民主党員の多くは拡張政策を全面的に支持したのに対し、ホイッグ党員(特に北部)の多くは反対した。ホイッグ党は工業化がもたらす変化の大半を歓迎しつつ も、既存の国土内での成長と発展を導く強力な政府政策を提唱した。彼らは拡張が奴隷制の領土への拡大という論争を呼ぶ問題を招くと(正しく)懸念した。一 方、民主党員の多くはホイッグ党が歓迎する工業化を恐れた... 多くの民主党員にとって、国家の社会問題への解決策は、トーマス・ジェファーソンの構想に従い、工業化に対抗する形で新領土に農業を確立し続けることだっ た。[9] 二人のネイティブアメリカンの著者が最近、マニフェスト・デスティニーのいくつかのテーマを、15世紀の「キリスト教発見の教義」という法令の本来の思想 と結びつけようとしている[42]。ニック・エステス(ラコタ族)は、15世紀のカトリック教義と、ヨーロッパ諸国の拡大におけるキリスト教徒と非キリス ト教徒の区別を結びつける。[42] エステスと国際法学者トニヤ・ゴネラ・フリクナー(オノンダガ族)はさらに、発見の教義をジョンソン対マッキントッシュ裁判と結びつけ、マニフェスト・デ スティニーとキリスト教発見の教義の相関関係を論じる。その根拠として、同裁判でジョン・マーシャル最高裁長官が「合衆国の先住民土地に対する権利を明 示」した際の声明を引用し、その根拠として発見の教義を援用した点を挙げている。[42][43] マーシャルは「先住民は『占有』権を有するが、これは『発見』の権力によってその土地が奪取され得ることを意味する」と裁定した。[43] フリクナーは「新たに成立した合衆国は、アメリカ先住民の政治的アイデンティティとインディアン土地概念を構築する必要があった。それは合衆国と西進植民 地拡大への道を開くためであった」と説明する。[43] このように、マニフェスト・デスティニーはヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の初期植民地化に触発されたものであり、アメリカ合衆国による先住民族国家への暴 力を正当化するものである。[42] 歴史家ドルセタ・テイラーによれば:「少数民族は通常、探検家や環境活動家として記録されない。しかし歴史的記録は、彼らが遠征隊の一員であり、フロン ティアに居住し労働し、町を創設し、教育者や起業家であったことを示している。要するに、有色人種は西部開拓において極めて重要な役割を担ったのだ」 [44] 中国やその他のアジア諸国との貿易への渇望も、拡張主義の根拠の一つであった。アメリカ人は、西進によるアジアとの接触の可能性を、アジアへの新たな航路 発見という西洋の長年の希望の実現と見なし、太平洋は大西洋よりも旧世界の紛争に支配されず、より秩序が保たれていると認識した。したがって、新興国家が 影響力を拡大する上で、より魅力的な地域と見なされたのである。[45] |

| Debate over Manifest destiny With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, which doubled the size of the United States, Thomas Jefferson set the stage for the continental expansion of the United States. Many began to see this as the beginning of a new providential mission: If the United States was successful as a "shining city upon a hill", people in other countries would seek to establish their own democratic republics.[46] Not all Americans or their political leaders believed that the United States was a divinely favored nation, or thought that it ought to expand. For example, many Whigs opposed territorial expansion based on the Democratic claim that the United States was destined to serve as a virtuous example to the rest of the world, and also had a divine obligation to spread its superordinate political system and a way of life throughout North American continent. Many in the Whig party "were fearful of spreading out too widely", and they "adhered to the concentration of national authority in a limited area".[47] In July 1848, Alexander Stephens denounced President Polk's expansionist interpretation of America's future as "mendacious".[48] In the mid‑19th century, expansionism, especially southward toward Cuba, also faced opposition from those Americans who were trying to abolish slavery. As more territory was added to the United States in the following decades, "extending the area of freedom" in the minds of southerners also meant extending the institution of slavery. That is why slavery became one of the central issues in the continental expansion of the United States before the Civil War.[49] Before and during the Civil War both sides claimed that America's destiny was rightfully their own. Abraham Lincoln opposed anti-immigrant nativism, and the imperialism of manifest destiny as both unjust and unreasonable.[50] He objected to the Mexican war and believed each of these disordered forms of patriotism threatened the inseparable moral and fraternal bonds of liberty and union that he sought to perpetuate through a patriotic love of country guided by wisdom and critical self-awareness. Lincoln's "Eulogy to Henry Clay", June 6, 1852, provides the most cogent expression of his reflective patriotism.[51] Ulysses S. Grant served in the war with Mexico and later wrote: I was bitterly opposed to the measure [to annex Texas], and to this day regard the war [with Mexico] which resulted as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory... The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war. Nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times.[52] |

マニフェスト・デスティニーをめぐる論争 1803年のルイジアナ購入により、アメリカ合衆国の領土は二倍に拡大した。トーマス・ジェファーソンはこれにより、アメリカの大陸横断的拡大の基盤を整 えたのである。多くの人々はこれを新たな天命の始まりと見なすようになった。もしアメリカが「丘の上の輝く都」として成功すれば、他国の人々も自らの民主 共和国を築こうとするだろうと。[46] すべてのアメリカ人や政治指導者が、アメリカが神に愛された国であるとか、拡大すべきだと考えていたわけではない。例えば、多くのホイッグ党員は、アメリ カは世界に対して良き手本となる運命にあり、また、その優れた政治体制と生活様式を北米大陸全体に広めるという神聖な義務を負っているという民主党の主張 に基づく領土拡大に反対した。ホイッグ党の多くの党員は「拡大しすぎることを恐れて」おり、「限られた地域に国家の権力を集中させる」ことを支持していた [47]。1848年7月、アレクサンダー・スティーブンスは、ポーク大統領のアメリカの将来に関する拡張主義的な解釈を「虚偽的」であると非難した。 [48] 19世紀半ば、特にキューバへの南進という拡張主義は、奴隷制度廃止を求めるアメリカ人からの反対にも直面した。その後数十年にわたって米国の領土が拡大 するにつれ、南部の人々の心の中で「自由の領域の拡大」は、奴隷制度の拡大も意味するようになった。そのため、南北戦争前の米国大陸拡大において、奴隷制 度は中心的な争点の一つとなった。[49] 南北戦争前と戦争中、双方はアメリカの運命は当然自分たちのものであると主張した。エイブラハム・リンカーンは、反移民的なナショナリズムと、マニフェス ト・デスティニーの帝国主義的拡大を、どちらも不当かつ不合理だと反対した。[50] 彼は米墨戦争に反対し、こうした無秩序な愛国主義の形態が、知恵と批判的自己認識に導かれた祖国愛を通じて永続させようとした、自由と連合という不可分の 道徳的・兄弟的絆を脅かすと信じていた。リンカーンの「ヘンリー・クレイ追悼演説」(1852年6月6日)は、彼の思索的な愛国主義を最も説得力ある形で 表現している。[51] ユリシーズ・S・グラントはメキシコ戦争に従軍し、後にこう記している: 私は(テキサス併合の)措置に激しく反対した。そして今日に至るまで、その結果生じた(メキシコとの)戦争を、強国が弱国に対して行った最も不当な戦争の 一つと見なしている。これは共和国が、追加領土獲得の欲望において正義を考慮しないという点で、ヨーロッパの君主国の悪い例に倣った事例であった... 南部の反乱は、主にメキシコ戦争の帰結であった。国家も個人と同様、その過ちに対して罰せられる。我々は現代史上最も血なまぐさく、最も高価な戦争という 形で罰を受けたのだ。[52] |

| Era of expansion See also: United States territorial acquisitions table  John Quincy Adams, painted above in 1816 by Charles Robert Leslie, was an early proponent of continentalism. Late in life he came to regret his role in helping U.S. slavery to expand, and became a leading opponent of the annexation of Texas. The phrase "manifest destiny" is most associated with the territorial expansion of the United States from 1803 to 1900. However, the Vermont Republic joined the United States in 1791, the territory of American Samoa grew larger in 1904 and 1925, and the U.S. acquired what is now the United States Virgin Islands in 1917 and what was the United Nations Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands in 1947. Of that Trust Territory, the Northern Mariana Islands joined the United States in 1986, while the Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of the Marshall Islands, and Palau became independent states in a Compact of Free Association with the U.S.[53][54] Some scholars limit the "manifest destiny" period to solely North American continental expansion from the Louisiana Purchase to the acquisition of Alaska in 1867, sometimes called the "age of manifest destiny".[55] During this time, the United States expanded to the Pacific Ocean—"from sea to shining sea"—largely defining the borders of the continental United States as they are today.[56] In the 1890s, the United States expanded into Polynesia and Asia with the annexation of the Republic of Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam, and American Samoa. War of 1812 Further information: War of 1812 One of the goals of the War of 1812 was to threaten to annex the British colony of Lower Canada as a bargaining chip to force the British to abandon their fortifications in the Northwestern United States and support for the various Native American tribes residing there.[57][58] The result of this overoptimism was a series of defeats in 1812 in part due to the wide use of poorly trained state militias rather than regular troops. The American victories at the Battle of Lake Erie and the Battle of the Thames in 1813 ended the Indian raids and removed the main reason for threatening annexation. To end the War of 1812 John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and Albert Gallatin (former treasury secretary and a leading expert on Indians) and the other American diplomats negotiated the Treaty of Ghent in 1814 with Britain. They rejected the British plan to set up an Indian state in U.S. territory south of the Great Lakes. They explained the American policy toward acquisition of Indian lands: The United States, while intending never to acquire lands from the Indians otherwise than peaceably, and with their free consent, are fully determined, in that manner, progressively, and in proportion as their growing population may require, to reclaim from the state of nature, and to bring into cultivation every portion of the territory contained within their acknowledged boundaries. In thus providing for the support of millions of civilized beings, they will not violate any dictate of justice or of humanity; for they will not only give to the few thousand savages scattered over that territory an ample equivalent for any right they may surrender, but will always leave them the possession of lands more than they can cultivate, and more than adequate to their subsistence, comfort, and enjoyment, by cultivation. If this be a spirit of aggrandizement, the undersigned are prepared to admit, in that sense, its existence; but they must deny that it affords the slightest proof of an intention not to respect the boundaries between them and European nations, or of a desire to encroach upon the territories of Great Britain... They will not suppose that that Government will avow, as the basis of their policy towards the United States a system of arresting their natural growth within their own territories, for the sake of preserving a perpetual desert for savages.[59] A shocked Henry Goulburn, one of the British negotiators at Ghent, remarked, after coming to understand the American position on taking the Indians' land: Till I came here, I had no idea of the fixed determination which there is in the heart of every American to extirpate the Indians and appropriate their territory.[60] |

拡張の時代 関連項目: アメリカ合衆国の領土獲得一覧  ジョン・クインシー・アダムズは、1816年にチャールズ・ロバート・レスリーによって描かれたこの肖像画の人物である。彼は大陸主義の初期の提唱者だっ た。晩年になると、アメリカの奴隷制拡大を助けた自身の役割を後悔するようになり、テキサス併合の主要な反対者となった。 「明白な運命」という言葉は、1803年から1900年にかけてのアメリカ合衆国の領土拡大と最も強く結びついている。しかし、バーモント共和国は 1791年に合衆国に加盟し、アメリカ領サモアの領土は1904年と1925年に拡大した。また合衆国は1917年に現在の米領バージン諸島を、1947 年には国連太平洋諸島信託統治領を領有した。この信託統治領のうち、北マリアナ諸島は1986年にアメリカ合衆国に編入された。一方、ミクロネシア連邦、 マーシャル諸島共和国、パラオは、アメリカ合衆国との自由連合協定により独立国家となった[53]。[54] 一部の学者は「マニフェスト・デスティニー」の期間を、ルイジアナ購入から1867年のアラスカ獲得までの北米大陸拡張のみに限定し、これを「マニフェス ト・デスティニーの時代」と呼ぶことがある。[55] この期間、アメリカ合衆国は太平洋へと拡大し——「海から輝く海へ」——今日のアメリカ本土の境界線をほぼ決定づけた。[56] 1890年代には、ハワイ共和国、フィリピン、グアム、アメリカ領サモアの併合により、ポリネシアとアジアへも拡大した。 1812年戦争 詳細情報: 1812年戦争 1812年戦争の目的の一つは、英国領カナダ下部を併合すると脅すことで、英国に北西部アメリカ合衆国の要塞放棄と、そこに居住する様々な先住民部族への 支援を放棄させる交渉材料とすることだった。[57][58] この過度の楽観主義の結果、1812年には一連の敗北を喫した。その一因は、正規軍ではなく訓練不足の州民兵を多用したことにある。1813年のエリー湖 の戦いとテムズ川の戦いでアメリカが勝利したことで、先住民による襲撃は終結し、併合を脅かす主な理由がなくなった。1812年戦争を終結させるため、 ジョン・クインシー・アダムズ、ヘンリー・クレイ、アルバート・ガラティン(元財務長官で先住民問題の第一人者)らアメリカ外交官は1814年、イギリス とヘント条約を締結した。彼らは五大湖南部のアメリカ領土に先住民国家を設置する英国の計画を拒否。先住民領土獲得に関するアメリカの方針を次のように説 明した: 合衆国は、平和的かつ自由な同意を得て以外の方法でインディアンから土地を取得する意図は決して持たない。しかし同時に、増加する人口の必要に応じて、認 められた境界内に含まれる領土のあらゆる部分を自然状態から回復し、耕作地へと変えることを、その方法により段階的に完全に決意している。こうして数百万 の文明人の生活を支えるにあたり、正義や人道に反する行為は一切行わない。なぜなら、その地域に散在する数千の野蛮人に対し、彼らが放棄する権利に見合う 十分な代償を与えるだけでなく、常に彼らが耕作できる以上の土地、すなわち耕作によって彼らの生存・快適・享受に十分すぎる土地を所有させ続けるからであ る。これが拡大主義の精神であるならば、署名者はその意味においてその存在を認める用意がある。しかし、それが米国と欧州諸国との境界を尊重しない意図、 あるいは英国の領土に侵食しようとする願望のわずかな証拠すら提供しないことは否定せねばならない。彼らは、英国政府がアメリカ合衆国に対する政策の基盤 として、自国領土内における自然成長を阻害し、野蛮人のための永久の荒野を保存しようとする制度を公言するとは考えない。[59] ゲントでの英国側交渉担当者の一人、ヘンリー・ゴールバーンは、インディアンの土地を奪うという米国の立場を理解した後、衝撃を受けてこう述べた: ここに来るまで、私は、あらゆるアメリカ人の心に、インディアンを根絶やしにしてその領土を接収するという揺るぎない決意が宿っているとは思いもよらなかった。[60] |

| Continentalism The 19th-century belief that the United States would eventually encompass all of North America is known as "continentalism".[61][62] An early proponent of this idea, John Quincy Adams became a leading figure in U.S. expansion between the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and the Polk administration in the 1840s. In 1811, Adams wrote to his father: The whole continent of North America appears to be destined by Divine Providence to be peopled by one nation, speaking one language, professing one general system of religious and political principles, and accustomed to one general tenor of social usages and customs. For the common happiness of them all, for their peace and prosperity, I believe it is indispensable that they should be associated in one federal Union.[63]  The first Fort Laramie as it looked prior to 1840. Painting from memory by Alfred Jacob Miller Adams did much to further this idea. He orchestrated the Treaty of 1818, which established the border between British North America and the United States as far west as the Rocky Mountains, and provided for the joint occupation of the region known in American history as the Oregon Country and in British and Canadian history as the New Caledonia and Columbia Districts. He negotiated the Transcontinental Treaty in 1819, transferring Florida from Spain to the United States and extending the U.S. border with Spanish Mexico all the way to the Pacific Ocean. And he formulated the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, which warned Europe that the Western Hemisphere was no longer open for European colonization. The Monroe Doctrine and "manifest destiny" formed a closely related nexus of principles: historian Walter McDougall calls manifest destiny a corollary of the Monroe Doctrine, because while the Monroe Doctrine did not specify expansion, expansion was necessary in order to enforce the doctrine. Concerns in the United States that European powers were seeking to acquire colonies or greater influence in North America led to calls for expansion in order to prevent this. In his influential 1935 study of manifest destiny, done in conjunction with the Walter Hines Page School of International Relations,[64] Albert Weinberg wrote: "the expansionism of the [1830s] arose as a defensive effort to forestall the encroachment of Europe in North America".[65] Transcontinental railroad Manifest destiny played an important role in the development of the transcontinental railroad.[when?] The transcontinental railroad system is often used in manifest destiny imagery like John Gast's painting, American Progress where multiple locomotives are seen traveling west.[1] According to academic Dina Gilio-Whitaker, "the transcontinental railroads not only enabled [U.S. control over the continent] but also accelerated it exponentially."[66] Historian Boyd Cothran says that "modern transportation development and abundant resource exploitation gave rise to an appropriation of indigenous land, [and] resources."[67] |

大陸主義 19世紀に広まった「アメリカ合衆国は最終的に北米大陸全体を包含する」という思想は「大陸主義」として知られる。[61][62] この思想の初期提唱者であるジョン・クインシー・アダムズは、1803年のルイジアナ購入から1840年代のポーク政権にかけてのアメリカ拡張政策の主導 的人物となった。1811年、アダムズは父にこう記している: 北米大陸全体は、神の摂理によって一つの国家が支配し、一つの言語を話し、一つの宗教的・政治的原則体系を掲げ、一つの社会慣習と風習に慣れるよう定めら れているように見える。彼らの共通の幸福、平和と繁栄のためには、一つの連邦連合に結ばれることが不可欠だと信じる。[63]  1840年以前のフォート・ララミーの最初の姿。アルフレッド・ジェイコブ・ミラーによる記憶画 アダムズはこの構想を推進するために多大な努力を払った。彼は1818年の条約を主導し、イギリス領北アメリカとアメリカ合衆国の国境をロッキー山脈まで 西に設定し、アメリカ史ではオレゴン地方、イギリス・カナダ史ではニューカレドニアおよびコロンビア地区として知られる地域の共同占領を定めた。彼は 1819年に大陸横断条約を交渉し、フロリダをスペインからアメリカ合衆国へ移譲させ、スペイン領メキシコとの国境を太平洋まで延伸させた。さらに 1823年にはモンロー主義を策定し、西半球はもはやヨーロッパの植民地化に開放されていないと警告した。 モンロー主義と「マニフェスト・デスティニー」は密接に関連する原則の連鎖を形成した。歴史家ウォルター・マクドゥーガルはマニフェスト・デスティニーを モンロー主義の帰結と呼ぶ。なぜならモンロー主義は拡張を明示しなかったが、その原則を実行するには拡張が不可欠だったからだ。欧州列強が北米で植民地や 影響力を拡大しようとしているとの米国の懸念が、これを阻止するための拡張要求につながったのである。1935年にウォルター・ハインズ・ページ国際関係 学校と共同で発表した影響力ある研究[64]の中で、アルバート・ワインバーグは次のように記している。「[1830年代の]拡張主義は、北米における ヨーロッパの進出を阻止するための防衛的努力として生じた」。[65] 大陸横断鉄道 マニフェスト・デスティニーは、大陸横断鉄道の発展において重要な役割を果たした。[いつ?] 大陸横断鉄道システムは、ジョン・ガストの絵画「アメリカの進歩」のように、複数の機関車が西に向かって走っている様子を描いた、マニフェスト・デスティ ニーのイメージでしばしば使用される。[1] 学者のディナ・ギリオ・ウィテカーによれば、「大陸横断鉄道は(米国による大陸の支配を)可能にしただけでなく、それを飛躍的に加速させた」[66]。歴 史家のボイド・コスランは、「近代的な交通機関の発達と豊富な資源の搾取が、先住民の土地や資源の収奪をもたらした」[67]と述べている。 |

| All Oregon Manifest destiny played its most important role in the Oregon boundary dispute between the United States and Britain, when the phrase "manifest destiny" originated. The Anglo-American Convention of 1818 had provided for the joint occupation of the Oregon Country, and thousands of Americans migrated there in the 1840s over the Oregon Trail. The British rejected a proposal by U.S. President John Tyler (in office 1841–1845) to divide the region along the 49th parallel, and instead proposed a boundary line farther south, along the Columbia River, which would have made most of what later became the state of Washington part of their colonies in North America. Advocates of manifest destiny protested and called for the annexation of the entire Oregon Country up to the Alaska line (54°40ʹ N). Presidential candidate Polk used this popular outcry to his advantage, and the Democrats called for the annexation of "All Oregon" in the 1844 U.S. presidential election.  American westward expansion is idealized in Emanuel Leutze's famous painting Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way (1861). As president, Polk sought compromise and renewed the earlier offer to divide the territory in half along the 49th parallel, to the dismay of the most ardent advocates of manifest destiny. When the British refused the offer, American expansionists responded with slogans such as "The whole of Oregon or none" and "Fifty-four forty or fight", referring to the northern border of the region. (The latter slogan is often mistakenly described as having been a part of the 1844 presidential campaign.)[68] When Polk moved to terminate the joint occupation agreement, the British finally agreed in early 1846 to divide the region along the 49th parallel, leaving the lower Columbia basin as part of the United States. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 formally settled the dispute; Polk's administration succeeded in selling the treaty to Congress because the United States was about to begin the Mexican–American War, and the president and others argued it would be foolish to also fight the British Empire.[citation needed] Despite the earlier clamor for "All Oregon", the Oregon Treaty was popular in the United States and was easily ratified by the Senate. The most fervent advocates of manifest destiny had not prevailed along the northern border because, according to Reginald Stuart, "the compass of manifest destiny pointed west and southwest, not north, despite the use of the term 'continentalism'".[69] In 1869, American historian Frances Fuller Victor published Manifest Destiny in the West in the Overland Monthly, arguing that the efforts of early American fur traders and missionaries presaged American control of Oregon. She concluded the article as follows: It was an oversight on the part of the United States, the giving up the island of Quadra and Vancouver, on the settlement of the boundary question. Yet, "what is to be, will be", as some realist has it; and we look for the restoration of that picturesque and rocky atom of our former territory as inevitable.[70] |

オレゴン全域 「明白な運命」という言葉が生まれたのは、アメリカとイギリスのオレゴン境界紛争において、明白な運命論が最も重要な役割を果たした時だ。1818年の英 米協定はオレゴン地方の共同占領を定めており、1840年代には何千人ものアメリカ人がオレゴン街道を通って移住した。英国は、ジョン・タイラー米大統領 (在任1841-1845年)が提案した北緯49度線を境界とする分割案を拒否し、代わりにコロンビア川沿いのより南側の境界線を提案した。この案が採用 されれば、後にワシントン州となる地域の大部分が英国の北米植民地の一部となっていただろう。マニフェスト・デスティニーの支持者たちはこれに抗議し、ア ラスカ境界線(北緯54度40分)までを含むオレゴン地方全体の併合を要求した。大統領候補ポークはこの民衆の怒りを利用し、民主党は1844年の大統領 選挙で「オレゴン全域」の併合を訴えた。  アメリカの西進政策は、エマニュエル・ロイツェの有名な絵画『帝国の進路は西へ』(1861年)で理想化されている。 大統領となったポークは妥協を図り、49度線に沿って領土を二分する以前の提案を再提示した。これはマニフェスト・デスティニーの熱烈な支持者たちを落胆 させた。英国がこの提案を拒否すると、アメリカの拡張主義者たちは「オレゴン全域か、さもなくば無か」「54度40分か、さもなくば戦い」といったスロー ガンで応じた。これらは同地域の北限を指すものである。(後者のスローガンは、1844年の大統領選挙運動の一部であったと誤って説明されることが多 い。)[68] ポークが共同占領協定の終了に動くと、イギリスは1846年初頭にようやく49度線に沿って地域を分割することに合意し、コロンビア川下流域はアメリカ合 衆国の一部として残された。1846年のオレゴン条約は正式にこの紛争を解決した。ポーク政権が議会に条約を承認させたのは、米国が米墨戦争を開始しよう としていた時期であり、大統領らは「英国帝国とも戦うのは愚かだ」と主張したためである。[出典必要] かつて「オレゴン全土」を主張する声が高かったにもかかわらず、オレゴン条約は米国で支持され、上院で容易に批准された。マニフェスト・デスティニーの最 も熱烈な支持者たちは、北の国境沿いでは優勢ではなかった。レジーナルド・スチュワートによれば、「マニフェスト・デスティニーの羅針盤は、大陸主義とい う用語が使われたにもかかわらず、北ではなく西と南西を指していた」からである。[69] 1869年、アメリカの歴史家フランシス・フラー・ビクターは、オーバーランド・マンスリー誌に「西部におけるマニフェスト・デスティニー」を発表し、初 期のアメリカの毛皮商人や宣教師たちの努力が、オレゴン州のアメリカによる支配を予見していたと主張した。彼女は、その記事を次のように締めくくってい る。 国境問題の解決において、クアドラ島とバンクーバー島を放棄したのは、アメリカ側の見落としであった。しかし「なるようになる」とある現実主義者が言うよ うに、我々はかつての領土であったあの絵のように美しい岩だらけの島が、必然的に返還されることを期待している。[70] |

Mexico and Texas The Battle of Río San Gabriel was a decisive battle action of the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) as part of the U.S. conquest of California.  The Battle of San Jacinto was the final battle during the Texas Revolution (1835-1836) which resulted in a decisive victory for the Texian army. Manifest destiny played an important role in the expansion of Texas and American relationship with Mexico.[71] In 1836, the Republic of Texas declared independence from Mexico and, after the Texas Revolution, sought to join the United States as a new state. This was an idealized process of expansion that had been advocated from Jefferson to O'Sullivan: newly democratic and independent states would request entry into the United States, rather than the United States extending its government over people who did not want it. The annexation of Texas was attacked by anti-slavery spokesmen because it would add another slave state to the Union. Presidents Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren declined Texas's offer to join the United States in part because the slavery issue threatened to divide the Democratic Party.[72] Before the election of 1844, Whig candidate Henry Clay and the presumed Democratic candidate, former president, Van Buren, both declared themselves opposed to the annexation of Texas, each hoping to keep the troublesome topic from becoming a campaign issue. This unexpectedly led to Van Buren being dropped by the Democrats in favor of Polk, who favored annexation. Polk tied the Texas annexation question with the Oregon dispute, thus providing a sort of regional compromise on expansion. (Expansionists in the North were more inclined to promote the occupation of Oregon, while Southern expansionists focused primarily on the annexation of Texas.) Although elected by a very slim margin, Polk proceeded as if his victory had been a mandate for expansion.[73] |

メキシコとテキサス リオ・サンガブリエルの戦いは、米墨戦争(1846-1848年)における決定的な戦闘であり、アメリカによるカリフォルニア征服の一環であった。  サン・ハシントの戦いは、テキサス革命(1835-1836年)の最終決戦であり、テキサス軍が決定的な勝利を収めた。 マニフェスト・デスティニーは、テキサスの拡大とアメリカとメキシコの関係において重要な役割を果たした[71]。1836年、テキサス共和国はメキシコ からの独立を宣言し、テキサス革命の後、新たな州としてアメリカ合衆国への加盟を求めた。これは、ジェファーソンからオサリバンまで提唱されてきた、理想 化された拡大の過程であった。つまり、新たに民主化され独立した州が、米国への加盟を申請するものであり、米国が、それを望まない人々にその政府を拡大す るものではない。テキサスの併合は、奴隷制反対派のスポークスマンから、連合に新たな奴隷州が加わることになるとして攻撃された。アンドルー・ジャクソン 大統領とマーティン・ヴァン・ビューレン大統領は、奴隷制問題が民主党を分裂させる恐れがあったこともあり、テキサスの合衆国加盟の申し出を拒否した。 [72] 1844年の選挙の前に、ホイッグ党の候補者ヘンリー・クレイと、民主党の候補者と見られていた元大統領ヴァン・ビューレンは、どちらもテキサス併合に反 対を表明した。それぞれ、厄介な問題が選挙の争点になるのを避けたいと考えていたのだ。これは予想外に、併合を支持するポークを支持して、民主党がヴァ ン・ビューレンを見捨てる結果となった。ポークはテキサス併合問題とオレゴン紛争を結びつけ、拡張政策に関する一種の地域的妥協案を提供した(北部の拡張 主義者はオレゴン占領を推進する傾向が強かったのに対し、南部の拡張主義者は主にテキサス併合に焦点を当てていた)。僅差での当選にもかかわらず、ポーク は自らの勝利が拡張政策への信任投票であったかのように行動した。[73] |

| All of Mexico Main article: All of Mexico Movement After the election of Polk, but before he took office, Congress approved the annexation of Texas. Polk moved to occupy a portion of Texas that had declared independence from Mexico in 1836, but was still claimed by Mexico. This paved the way for the outbreak of the Mexican–American War on April 24, 1846. With American successes on the battlefield, by the summer of 1847 there were calls for the annexation of "All Mexico", particularly among Eastern Democrats, who argued that bringing Mexico into the Union was the best way to ensure future peace in the region.[74] This was a controversial proposition for two reasons. First, idealistic advocates of manifest destiny like O'Sullivan had always maintained that the laws of the United States should not be imposed on people against their will. The annexation of "All Mexico" would be a violation of this principle. And secondly, the annexation of Mexico was controversial because it would mean extending U.S. citizenship to millions of Mexicans, who were of dark skin and majority Catholic. Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who had approved of the annexation of Texas, was opposed to the annexation of Mexico, as well as the "mission" aspect of manifest destiny, for racial reasons.[75] He made these views clear in a speech to Congress on January 4, 1848: We have never dreamt of incorporating into our Union any but the Caucasian race—the free white race. To incorporate Mexico, would be the very first instance of the kind, of incorporating an Indian race; for more than half of the Mexicans are Indians, and the other is composed chiefly of mixed tribes. I protest against such a union as that! Ours, sir, is the Government of a white race.... We are anxious to force free government on all; and I see that it has been urged ... that it is the mission of this country to spread civil and religious liberty over all the world, and especially over this continent. It is a great mistake.[76][77] This debate brought to the forefront one of the contradictions of manifest destiny: on the one hand, while identitarian ideas inherent in manifest destiny suggested that Mexicans, as non-whites, would present a threat to white racial integrity and thus were not qualified to become Americans, the "mission" component of manifest destiny suggested that Mexicans would be improved (or "regenerated", as it was then described) by bringing them into American democracy. Identitarianism was used to promote manifest destiny, but, as in the case of Calhoun and the resistance to the "All Mexico" movement, identitarianism was also used to oppose manifest destiny.[78] Conversely, proponents of annexation of "All Mexico" regarded it as an anti-slavery measure.[79]  Growth from 1840 to 1850 The controversy was eventually ended by the Mexican Cession, which added the territories of Alta California and Nuevo México to the United States, both more sparsely populated than the rest of Mexico. Like the "All Oregon" movement, the "All Mexico" movement quickly abated. Historian Frederick Merk, in Manifest Destiny and Mission in American History: A Reinterpretation (1963), argued that the failure of the "All Oregon" and "All Mexico" movements indicates that manifest destiny had not been as popular as historians have traditionally portrayed it to have been. Merk wrote that, while belief in the beneficent mission of democracy was central to American history, aggressive "continentalism" were aberrations supported by only a minority of Americans, all of them Democrats. Some Democrats were also opposed; the Democrats of Louisiana opposed annexation of Mexico,[80] while those in Mississippi supported it.[81] These events related to the Mexican–American War and had an effect on the American people living in the Southern Plains at the time. A case study by David Beyreis depicts these effects through the operations of a fur trading and Indian trading business named Bent, St. Vrain and Company during the period. The telling of this company shows that the idea of Manifest Destiny was not unanimously loved by all Americans and did not always benefit Americans. The case study goes on to show that this company could have ceased to exist in the name of territorial expansion.[82] |

全メキシコ メイン記事: 全メキシコ運動 ポークの当選後、彼が就任する前に、議会はテキサスの併合を承認した。ポークは1836年にメキシコからの独立を宣言したが、依然としてメキシコが領有権 を主張していたテキサスの一部を占領する動きに出た。これが1846年4月24日の米墨戦争勃発への道を開いた。戦場でのアメリカの勝利に伴い、1847 年の夏までに「全メキシコ」併合を求める声が上がった。特に東部民主党員の間で、メキシコを合衆国に組み入れることが地域の将来の平和を保証する最善策だ と主張された。[74] この主張は二つの理由で論争を呼んだ。第一に、オサリバンのようなマニフェスト・デスティニーの理想主義的提唱者は、常に「米国の法律を人民の意思に反し て押し付けるべきではない」と主張してきた。「全メキシコ」併合はこの原則に反する。第二に、メキシコ併合は数百万のメキシコ人(肌の色が濃く、大多数が カトリック教徒)に米国市民権を付与することを意味するため、論争を呼んだのである。サウスカロライナ州選出のジョン・C・カルフーン上院議員は、テキサ ス併合を支持した一方で、人種的理由からメキシコ併合とマニフェスト・デスティニーの「使命」的側面には反対した[75]。彼は1848年1月4日の議会 演説でこの見解を明確に表明している: 我々は、白人種、すなわち自由な白人種以外のいかなる人種も連邦に組み入れることを夢にも考えたことはない。メキシコを組み入れることは、まさに先例のな い、インドのの人種の組み入れとなる。メキシコ人の半数以上はインドのであり、残りは主に混血の部族で構成されているからだ。私はそのような連合に抗議す る!我々の政府は白人種のための政府であるのだ… 我々は自由な政府を万人に押し付けようと躍起だ。そしてこの国には、特にこの大陸において、全世界に市民的・宗教的自由を広める使命があると主張されてい るのを見かける。これは大きな誤りだ。[76][77] この議論は、マニフェスト・デスティニーの矛盾の一つを浮き彫りにした。一方で、マニフェスト・デスティニーに内在するアイデンティティ主義的観念は、メ キシコ人が非白人である以上、白人種としての純粋性に脅威をもたらすため、アメリカ人となる資格がないと示唆していた。他方で、マニフェスト・デスティ ニーの「使命」的要素は、メキシコ人をアメリカの民主主義に取り込むことで、彼らが改善される(当時「再生」と表現された)と示唆していたのである。アイ デンティタリアニズムはマニフェスト・デスティニーを推進するために用いられたが、カルフーンや「全メキシコ併合」運動への抵抗事例に見られるように、マ ニフェスト・デスティニーに反対するためにも用いられた[78]。逆に「全メキシコ併合」の支持者たちは、これを奴隷制廃止の手段と見なしていた。 [79]  1840年から1850年にかけての成長 この論争は最終的にメキシコ割譲によって終結した。これによりアルタ・カリフォルニアとヌエボ・メキシコの領土がアメリカ合衆国に加わったが、いずれもメキシコ本土より人口がまばらだった。「オール・オレゴン」運動と同様に、「オール・メキシコ」運動も急速に沈静化した。 歴史家フレデリック・マークは『マニフェスト・デスティニーとアメリカ史における使命:再解釈』(1963年)において、「オール・オレゴン」と「オー ル・メキシコ」運動の失敗は、マニフェスト・デスティニーが従来歴史家が描いてきたほど国民的ではなかったことを示していると論じた。マークは、民主主義 の有益な使命への信念がアメリカ史の中心であった一方で、攻撃的な「大陸主義」は少数派のアメリカ人、それも全員民主党員によって支持された異常な現象で あったと記している。民主党員の中にも反対派は存在した。ルイジアナ州の民主党員はメキシコ併合に反対した[80]が、ミシシッピ州の民主党員はこれを支 持した。[81] これらの出来事は米墨戦争に関連し、当時南部平原に住んでいたアメリカ人民に影響を与えた。デイヴィッド・ベイレイスの事例研究は、この時代の毛皮取引・ インドの交易会社「ベント・セントヴレイン社」の活動を通じて、こうした影響を描いている。同社の事例は、マニフェスト・デスティニーの思想が全てのアメ リカ人に愛されたわけではなく、常にアメリカ人の利益になったわけでもないことを示している。さらにこの研究は、領土拡大の名の下に同社が消滅する可能性 すらあったことを明らかにしている[82]。 |

| Filibusterism After the Mexican–American War ended in 1848, disagreements over the expansion of slavery made further annexation by conquest too divisive to be official government policy. Some, such as John Quitman, Governor of Mississippi, offered what public support they could. In one memorable case, Quitman simply explained that the state of Mississippi had "lost" its state arsenal, which began showing up in the hands of filibusters. Yet these isolated cases only solidified opposition in the North as many Northerners were increasingly opposed to what they believed to be efforts by Southern slave owners—and their friends in the North—to expand slavery through filibustering. Sarah P. Remond on January 24, 1859, delivered an impassioned speech at Warrington, England, that the connection between filibustering and slave power was clear proof of "the mass of corruption that underlay the whole system of American government".[83] The Wilmot Proviso and the continued "Slave Power" narratives thereafter, indicated the degree to which manifest destiny had become part of the sectional controversy.[84] Without official government support the most radical advocates of manifest destiny increasingly turned to military filibustering. Originally filibuster had come from the Dutch vrijbuiter and referred to buccaneers in the West Indies that preyed on Spanish commerce. While there had been some filibustering expeditions into Canada in the late 1830s, it was only by mid-century did filibuster become a definitive term. By then, declared the New-York Daily Times "the fever of Fillibusterism is on our country. Her pulse beats like a hammer at the wrist, and there's a very high color on her face."[85] Millard Fillmore's second annual message to Congress, submitted in December 1851, gave double the amount of space to filibustering activities than the brewing sectional conflict. The eagerness of the filibusters, and the public to support them, had an international hue. Clay's son, a diplomat in Portugal, reported that the invasion created a sensation in Lisbon.[86]  Filibuster William Walker, who launched several expeditions to Mexico and Central America, ruled Nicaragua, and was captured by the Royal Navy before being executed in Honduras by the Honduran government. Although they were illegal, filibustering operations in the late 1840s and early 1850s were romanticized in the United States. The Democratic Party's national platform included a plank that specifically endorsed William Walker's filibustering in Nicaragua. Wealthy American expansionists financed dozens of expeditions, usually based out of New Orleans, New York, and San Francisco. The primary target of manifest destiny's filibusters was Latin America but there were isolated incidents elsewhere. Mexico was a favorite target of organizations devoted to filibustering, like the Knights of the Golden Circle.[87] William Walker got his start as a filibuster in an ill-advised attempt to separate the Mexican states Sonora and Baja California.[88] Narciso López, a near second in fame and success, spent his efforts trying to secure Cuba from the Spanish Empire. The United States had long been interested in acquiring Cuba from the declining Spanish Empire. As with Texas, Oregon, and California, American policy makers were concerned that Cuba would fall into British hands, which, according to the thinking of the Monroe Doctrine, would constitute a threat to the interests of the United States. Prompted by O'Sullivan, in 1848 President Polk offered to buy Cuba from Spain for $100 million. Polk feared that filibustering would hurt his effort to buy the island, and so he informed the Spanish of an attempt by the Cuban filibuster López to seize Cuba by force and annex it to the United States, foiling the plot. Spain declined to sell the island, which ended Polk's efforts to acquire Cuba. O'Sullivan eventually landed in legal trouble.[89] Filibustering continued to be a major concern for presidents after Polk. Whigs presidents Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore tried to suppress the expeditions. When the Democrats recaptured the White House in 1852 with the election of Franklin Pierce, a filibustering effort by John A. Quitman to acquire Cuba received the tentative support of the president. Pierce backed off and instead renewed the offer to buy the island, this time for $130 million. When the public learned of the Ostend Manifesto in 1854, which argued that the United States could seize Cuba by force if Spain refused to sell, this effectively killed the effort to acquire the island. The public now linked expansion with slavery; if manifest destiny had once enjoyed widespread popular approval, this was no longer true.[90] Filibusters like William Walker continued to garner headlines in the late 1850s, but to little effect. Expansionism was among the various issues that played a role in the coming of the war. With the divisive question of the expansion of slavery, Northerners and Southerners, in effect, were coming to define manifest destiny in different ways, undermining nationalism as a unifying force. According to Frederick Merk, "The doctrine of Manifest Destiny, which in the 1840s had seemed Heaven-sent, proved to have been a bomb wrapped up in idealism."[91] The filibusterism of the era even opened itself up to some mockery among the headlines. In 1854, a San Francisco Newspaper published a satirical poem called "Filibustering Ethics". This poem features two characters, Captain Robb and Farmer Cobb. Captain Robb makes claim to Farmer Cobb's land arguing that Robb deserves the land because he is Anglo-Saxon, has weapons to "blow out" Cobb's brains, and nobody has heard of Cobb so what right does Cobb have to claim the land. Cobb argues that Robb doesn't need his land because Robb already has more land than he knows what to do with. Due to threats of violence, Cobb surrenders his land and leaves grumbling that "might should be the rule of right among enlightened nations."[92] |

フィリバスター主義 1848年に米墨戦争が終結した後、奴隷制拡大をめぐる意見の相違により、武力によるさらなる併合は政府の公式政策として分裂を招きすぎた。ミシシッピ州 知事ジョン・クィットマンら一部の人物は、可能な限りの公的支援を示した。特に有名な事例として、クィットマンはミシシッピ州の州兵器庫が「紛失」したと 説明した。その兵器は後にフィリバスターたちの手に渡り始めたのである。しかしこうした孤立した事例は、むしろ北部の反対勢力を固める結果となった。多く の北部住民は、南部奴隷所有者とその北部における協力者たちが、私賊行為を通じて奴隷制を拡大しようとしていると確信し、これに強く反発したのである。サ ラ・P・レモンドは1859年1月24日、イングランドのウォリントンで熱弁をふるい、私賊行為と奴隷制勢力の結びつきこそが「アメリカ政府全体に潜む腐 敗の塊」を証明していると主張した[83]。ウィルモット付帯条項とその後も続く「奴隷制勢力」論は、マニフェスト・デスティニーが地域対立の争点に深く 入り込んでいたことを示していた。[84] 政府の公式支援を得られない中、マニフェスト・デスティニーの過激な支持者たちは次第に軍事的な私賊行為に傾倒していった。フィリバスターという言葉はも ともとオランダ語のvrijbuiterに由来し、西インド諸島でスペイン商船を襲撃する海賊を指していた。1830年代後半にはカナダへのフィリバス ター遠征もいくつかあったが、フィリバスターが明確な用語として定着したのは世紀半ばになってからである。当時『ニューヨーク・デイリー・タイムズ』紙は こう宣言した。「我が国はフィリブスター主義の熱病に冒されている。その脈拍は手首でハンマーのように打ち鳴らされ、顔には非常に強い紅潮が浮かんでい る」[85]。1851年12月に提出されたミラード・フィルモアの第二期議会年次教書は、激化する地域対立よりも私賊行為に倍の紙幅を割いた。フィリバ スターたちの熱意と、彼らを支持する大衆の気運は国際的な色合いを帯びていた。ポルトガル駐在の外交官であったクレイの息子は、この侵攻がリスボンでセン セーションを巻き起こしたと報告している[86]。  フィリバスターのウィリアム・ウォーカーは、メキシコと中央アメリカへ数度の遠征を敢行し、ニカラグアを支配した。その後、ホンジュラス政府によって処刑される前にイギリス海軍に捕らえられた。 1840年代末から1850年代初頭の私賊行為作戦は違法であったが、アメリカ国内ではロマンチックに美化された。民主党の全国綱領には、ウィリアム・ ウォーカーのニカラグアでの私賊行為を具体的に支持する条項が含まれていた。富裕なアメリカ拡張主義者たちは、ニューオーリンズ、ニューヨーク、サンフラ ンシスコを拠点に、数十の遠征隊に資金を提供した。マニフェスト・デスティニーのフィリブスターの主たる標的はラテンアメリカだったが、他の地域でも散発 的な事件は発生した。メキシコは「黄金の円環騎士団」のような私賊行為組織の好標的だった[87]。ウィリアム・ウォーカーは、メキシコのソノラ州とバ ハ・カリフォルニア州を分離しようとする無謀な試みで私賊行為としてのキャリアを始めた。[88] 名声と成功で彼に次ぐナルシソ・ロペスは、スペイン帝国からキューバを奪取しようと尽力した。 アメリカ合衆国は、衰退しつつあるスペイン帝国からキューバを獲得することに長年関心を寄せていた。テキサス、オレゴン、カリフォルニアと同様に、アメリ カの政策立案者たちはキューバが英国の手に落ちることを懸念していた。モンロー主義の考え方によれば、それはアメリカの利益に対する脅威となるからだ。オ サリバンの働きかけにより、1848年にポーク大統領はスペインに対し1億ドルでキューバ購入を申し出た。ポークは私賊行為が島買収の妨げとなることを恐 れ、キューバの私賊行為であるロペスが武力によるキューバ占領とアメリカ併合を図っているとの情報をスペインに提供し、この計画を阻止した。スペインは島 の売却を拒否し、ポークのキューバ獲得の試みは終焉を迎えた。オサリバンは結局、法的な問題に巻き込まれた。 ポーク大統領以降も、私賊行為は大統領にとって大きな懸念事項であり続けた。ホイッグ党のザカリー・テイラー大統領とミラード・フィルモア大統領は、私賊 行為の遠征を抑制しようとした。1852年に民主党がフランクリン・ピアースの当選でホワイトハウスを奪還すると、ジョン・A・クイトマンによるキューバ 獲得のための私賊行為の試みは、大統領の暫定的な支持を得た。ピアースはこれを撤回し、代わりに1億3000万ドルで島を購入するという提案を再提出し た。1854年、スペインが売却を拒否した場合、米国は武力によってキューバを占領できると主張する「オステンド宣言」が公になったことで、島を獲得する 動きは事実上頓挫した。国民は、拡大主義と奴隷制度を結びつけて考えるようになった。かつては、マニフェスト・デスティニーが国民の大半の支持を得ていた が、もはやそうではなかった。[90] ウィリアム・ウォーカーのような私賊行為は1850年代後半も話題をさらったが、ほとんど効果はなかった。拡張主義は戦争勃発の要因となった諸問題の一つ であった。奴隷制拡大という分断的な問題をめぐり、北部と南部は事実上、マニフェスト・デスティニーを異なる形で定義し始め、ナショナリズムを国家統一の 力として弱体化させていた。フレデリック・マークによれば、「1840年代には天から授かったものと思われたマニフェスト・デスティニーの教義は、理想主 義に包まれた爆弾であったことが証明された」[91]。 当時の私賊行為は、見出しの中で嘲笑の対象となることもあった。1854年、サンフランシスコの新聞は「私賊倫理」と題した風刺詩を掲載した。この詩には ロブ船長とコブ農夫という二人が登場する。ロブ船長はコブ農夫の土地を要求し、自分はアングロサクソン人であり、コブの脳みそを吹き飛ばす武器を持ってい るから土地を得る権利があると主張する。さらにコブなど誰も知らない存在なのだから、土地を要求する資格などないと述べる。コブは反論する。ロブは既に使 い道も分からないほど多くの土地を持っているのだから、自分の土地など必要ないと。暴力の脅威に屈したコブは土地を明け渡し、「 enlightened な国民では力こそが正義のルールであるべきだ」と愚痴をこぼしながら去っていった[92]。 |

| Homestead Act Main article: Homestead Acts  Norwegian settlers in North Dakota in front of their homestead, a sod hut The Homestead Act of 1862 encouraged 600,000 families to settle the West by giving them land (usually 160 acres) almost free. Over the course of 123 years, 200 million claims were made and over 270 million acres were settled, accounting for 10% of the land in the U.S.[93] They had to live on and improve the land for five years.[94] Before the American Civil War, Southern leaders opposed the Homestead Acts because they feared it would lead to more free states and free territories.[95] After the mass resignation of Southern senators and representatives at the beginning of the war, Congress was subsequently able to pass the Homestead Act. In some areas, the Homestead Act resulted in the direct removal of Indigenous communities.[96] According to American historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, all five nations of the "Five Civilized Tribes" signed treaties with the Confederacy and initially supported them in hopes of dividing and weakening the U.S. so that they could remain on their land.[97] The United States Army, led by prominent Civil War generals such as William Tecumseh Sherman, Philip Sheridan, and George Armstrong Custer, waged wars on "non-treaty Indians" who continued to live on land that had already been ceded to the U.S. through treaty.[96][97] Homesteaders and other settlers soon followed and took possession of the land for farms and mining. Occasionally, white settlers would move ahead of the U.S. Army, into land that had not yet been settled by the United States, causing conflict with the Native people who still resided there. According to Anglo-American historian Julius Wilm, while the U.S. government did not approve of settlers moving ahead of the army, Indian Affairs officials did believe "the move of frontier whites into the proximity of contested territory—be they homesteaders or parties interested in other pursuits—necessitated the removal of Indigenous nations."[96] According to historian Hannah Anderson, the Homestead Act also led to environmental degradation. While it succeeded in settling and farming the land, the Act failed to preserve the land. Continuous plowing of the top soil made the soil vulnerable to erosion and wind, as well as stripping the nutrients from the ground. This deforestation and erosion would play a key role in the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. Intense logging caused a decrease in much of the forests and hunting harmed many of the native animal populations, including the bison, whose population was reduced to a few hundreds.[93] |

ホームステッド法 主な記事: ホームステッド法  ノースダコタ州のノルウェー人入植者たち。彼らのホームステッドである土壁の小屋の前で 1862年のホームステッド法は、土地(通常160エーカー)をほぼ無償で与えることで、60万世帯の西部開拓を促した。123年間で2億件の申請があ り、2億7000万エーカー以上が開拓された。これは米国全土の10%に相当する。[93] 彼らは5年間その土地に住み、改良しなければならなかった。[94] 南北戦争前、南部指導者たちはホームステッド法に反対した。自由州や自由領土が増えることを恐れたからだ。[95] 戦争開始時に南部上院議員・下院議員が大量辞任した後、議会はホームステッド法を成立させることができた。 一部の地域では、ホームステッド法によって先住民コミュニティが直接追放された。アメリカの歴史家ロクサーヌ・ダンバー・オルティスによれば、「五つの文 明部族」の5部族すべてが南軍と条約を結び、当初は米国を分裂・弱体化させて自分たちの土地に留まることを望んで南軍を支持していた。[97] ウィリアム・テカムセ・シャーマン、フィリップ・シェリダン、ジョージ・アームストロング・カスターなどの南北戦争の著名な将軍たちが率いるアメリカ陸軍 は、条約によってすでに米国に割譲されていた土地に引き続き居住していた「非条約インドの」に対して戦争を繰り広げた。[96][97] ホームステッド法による入植者やその他の入植者もすぐに後を追って、農場や鉱山のためにその土地を占領した。時折、白人入植者たちは米軍に先んじて、米国 がまだ開拓していない土地に進出し、そこにまだ居住していた先住民との紛争を引き起こした。英米の歴史家ジュリアス・ウィルムによれば、米国政府は入植者 が軍隊に先んじて移動することを承認していなかったが、インドの担当官は「開拓者であれ、他の目的を持つ者であれ、白人が紛争地域近くに移動することは、 先住国民の移住を必要とする」と信じていたという[96]。 歴史家ハンナ・アンダーソンによれば、ホームステッド法は環境悪化も招いた。土地の開拓と耕作には成功したが、土地の保全には失敗したのである。表土を絶 え間なく耕すことで、土壌は侵食や風の影響を受けやすくなり、土壌の養分も失われた。この森林伐採と侵食は、1930年代のダストボウル(砂塵嵐)の発生 に大きな影響を与えた。激しい伐採により森林の多くが減少、狩猟によりバイソンを含む多くの在来動物が被害を受け、バイソンの生息数は数百頭にまで減少し た。 |

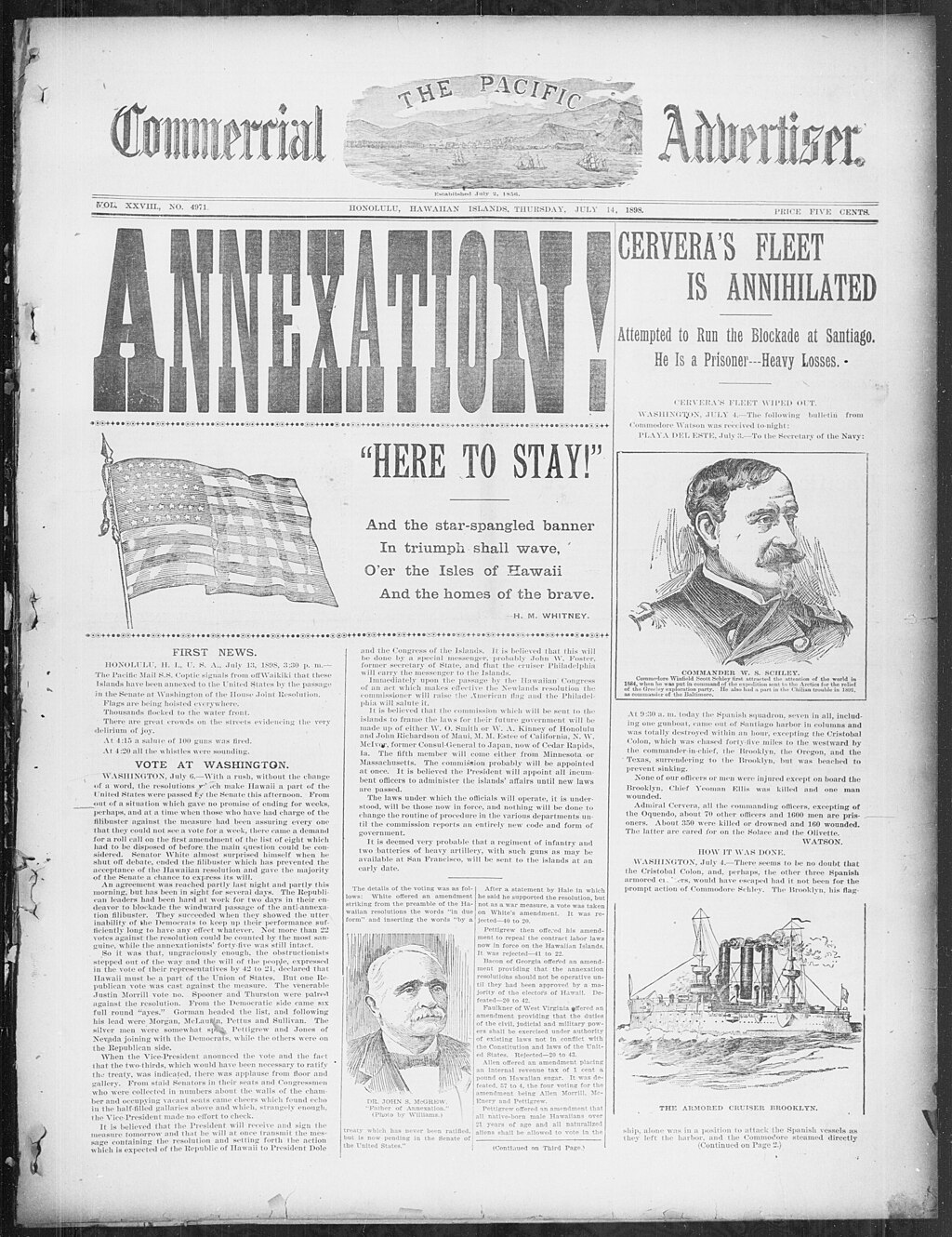

Beyond North America: Annexation of Hawaii Newspaper reporting the annexation of the Republic of Hawaii in 1898 In 1859, Reuben Davis, a member of the House of Representatives from Mississippi, articulated one of the most expansive visions of manifest destiny on record: We may expand so as to include the whole world. Mexico, Central America, South America, Cuba, the West India Islands, and even England and France [we] might annex without inconvenience... allowing them with their local Legislatures to regulate their local affairs in their own way. And this, Sir, is the mission of this Republic and its ultimate destiny.[98] As the Civil War faded into history, the term manifest destiny experienced a brief revival. Protestant missionary Josiah Strong, in his best-seller of 1885, Our Country, argued that the future was devolved upon America since it had perfected the ideals of civil liberty, "a pure spiritual Christianity", and concluded, "My plea is not, Save America for America's sake, but, Save America for the world's sake."[99] In the 1892 U.S. presidential election, the Republican Party platform proclaimed: "We reaffirm our approval of the Monroe doctrine and believe in the achievement of the manifest destiny of the Republic in its broadest sense."[100] What was meant by "manifest destiny" in this context was not clearly defined, particularly since the Republicans lost the election. In the 1896 election, the Republicans recaptured the White House and held on to it for the next 16 years. During that time, manifest destiny was cited to promote overseas expansion. Whether or not this version of manifest destiny was consistent with the continental expansionism of the 1840s was debated at the time, and long afterwards.[101] For example, when President William McKinley advocated annexation of the Republic of Hawaii in 1898, he said that "We need Hawaii just as much and a good deal more than we did California. It is manifest destiny." On the other hand, former President Grover Cleveland, a Democrat who had blocked the annexation of Hawaii during his administration, wrote that McKinley's annexation of the territory was a "perversion of our national destiny". Historians continued that debate; some have interpreted American acquisition of other Pacific island groups in the 1890s as an extension of manifest destiny across the Pacific Ocean. Others have regarded it as the antithesis of manifest destiny and merely imperialism.[102] |

北米を超えて:ハワイの併合 1898年のハワイ共和国併合を報じた新聞 1859年、ミシシッピ州選出の連邦下院議員ルーベン・デイヴィスは、マニフェスト・デスティニー(明白な運命)に関する最も広範なビジョンの一つを次のように述べた。 我々は全世界を包含するように拡大するかもしれない。メキシコ、中央アメリカ、南アメリカ、キューバ、西インド諸島、さらにはイギリスやフランスでさえ も、不便なく併合できるかもしれない... それらの地域には、それぞれの地方議会が独自の方法で地域の問題を規制することを認める。そして、これが、この共和国の使命であり、その究極の運命であ る。[98] 南北戦争が歴史に埋もれていくにつれて、「マニフェスト・デスティニー」という用語は一時的に復活した。プロテスタント宣教師ジョサイア・ストロングは 1885年のベストセラー『我が国』で、市民的自由と「純粋な精神的キリスト教」の理想を完成させたアメリカに未来が委ねられていると主張し、「私の訴え は、アメリカのためにアメリカを救えではない。世界のためにアメリカを救えである」と結論づけた[99]。 1892年の米大統領選挙で共和党は綱領にこう宣言した。「我々はモンロー主義を再承認し、共和国が広義において明白な天命を達成すると信じる」[100]。この文脈における「明白な天命」の定義は明確でなかった。特に共和党が選挙に敗れたためである。 1896年の選挙で共和党はホワイトハウスを奪還し、その後16年間政権を維持した。この期間中、海外拡張を推進するためにマニフェスト・デスティニーが 引用された。このバージョンのマニフェスト・デスティニーが1840年代の大陸拡張主義と整合するかどうかは、当時もその後も長く議論された。[101] 例えば、ウィリアム・マッキンリー大統領が1898年にハワイ共和国の併合を提唱した際、「我々はハワイをカリフォルニア以上に必要としている。これは明 白な天命だ」と述べた。一方、民主党のグロバー・クリーブランド前大統領(在任中にハワイ併合を阻止した人物)は、マッキンリーによる領土併合を「国民の 天命の歪曲」と記した。歴史家たちはこの議論を継続した。1890年代の太平洋諸島獲得を太平洋を越えたマニフェスト・デスティニーの延長と解釈する者も いれば、マニフェスト・デスティニーの対極であり単なる帝国主義に過ぎないと見る者もいる。[102] |

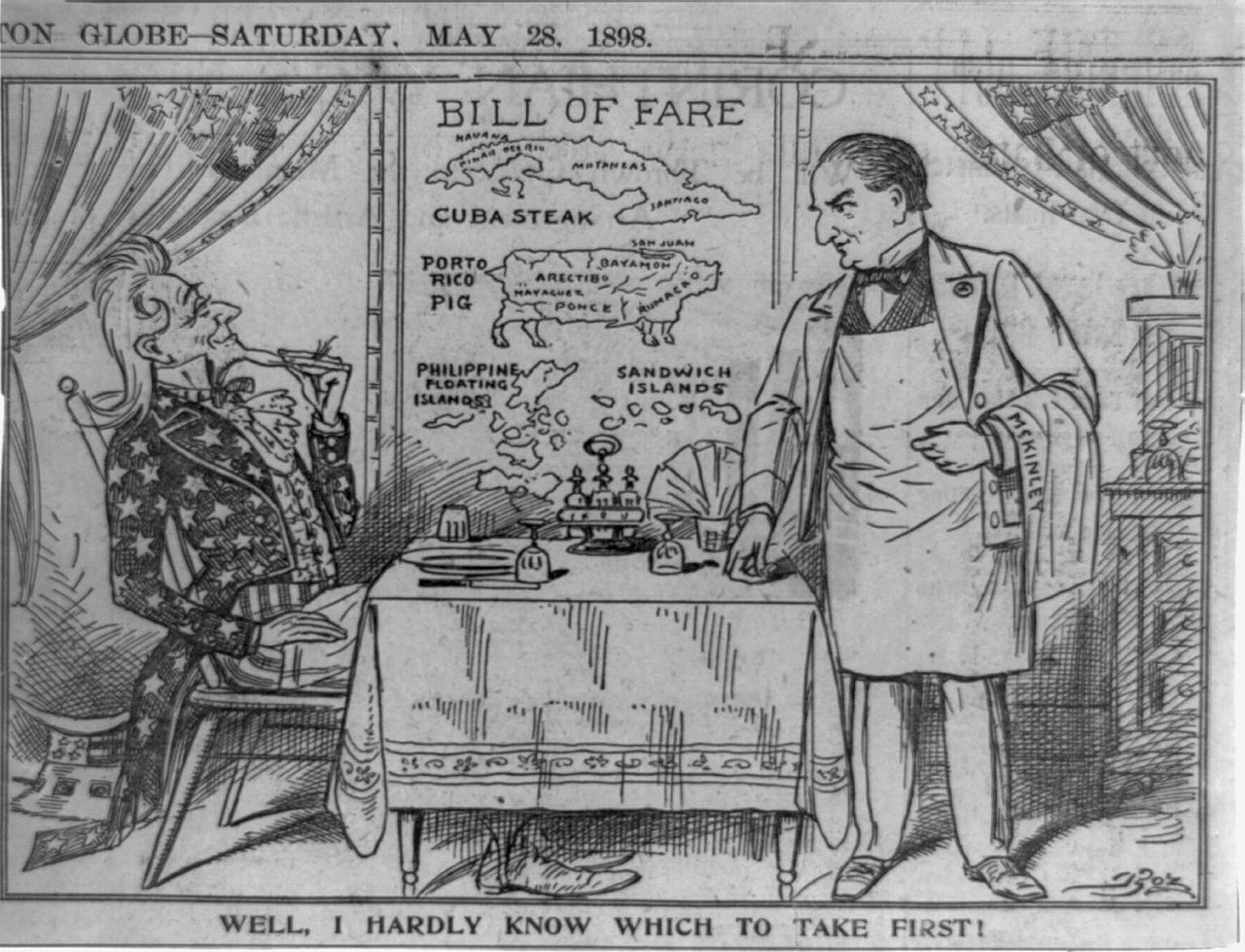

| Spanish–American War Main article: Spanish-American War  A cartoon of Uncle Sam seated in restaurant looking at the bill of fare containing "Cuba steak", "Porto Rico pig", the "Philippine Islands" and the "Sandwich Islands" (Hawaii) In 1898, the United States intervened in the Cuban insurrection and launched the Spanish–American War to force Spain out. According to the terms of the Treaty of Paris, Spain relinquished sovereignty over Cuba and ceded the Philippine Islands, Puerto Rico, and Guam to the United States. The terms of cession for the Philippines involved a payment of the sum of $20 million by the United States to Spain. The treaty was highly contentious and denounced by William Jennings Bryan, who tried to make it a central issue in the 1900 election, which he lost to McKinley.[103] The Teller Amendment, passed unanimously by the U.S. Senate before the war, which proclaimed Cuba "free and independent", forestalled annexation of the island. The Platt Amendment (1902) then established Cuba as a virtual protectorate of the United States.[104] |

米西戦争 メイン記事: 米西戦争  レストランに座るアンクル・サムの風刺画。メニューには「キューバステーキ」「プエルトリコ豚」「フィリピン諸島」「サンドウィッチ諸島」と書かれている (ハワイ) 1898年、アメリカ合衆国はキューバの反乱に介入し、スペインを追い出すために米西戦争を開始した。パリ条約の条件に基づき、スペインはキューバの主権 を放棄し、フィリピン諸島、プエルトリコ、グアムをアメリカ合衆国に割譲した。フィリピンの割譲条件には、アメリカ合衆国がスペインに2000万ドルを支 払うことが含まれていた。この条約は激しい論争を呼び、ウィリアム・ジェニングス・ブライアンによって非難された。彼は1900年の大統領選挙でこの問題 を主要争点にしようとしたが、マッキンリーに敗れた[103]。 戦争前に米国上院で満場一致で可決されたテラー修正案は、キューバを「自由かつ独立した」国と宣言し、同島の併合を阻止した。その後、プラット修正案(1902年)により、キューバは事実上の米国の保護領となった。[104] |

| American Samoa The United States, German Empire, and United Kingdom participted in the Tripartite Convention of 1899 at the end of the Second Samoan Civil War, resulting in the formal partition of the Samoan archipelago into a German colony and the U.S. territory of what is now called American Samoa. The United States annexed Tutuila in 1900, Manu'a in 1904, and Swains Island in 1925.[105][106] The eastern Samoan islands became a territory of the United States.[107] The western islands, by far the greater landmass, became known as German Samoa, after Britain gave up all claims to Samoa and in return accepted the termination of German rights in Tonga and certain areas in the Solomon Islands and West Africa.[108] Forerunners to the Tripartite Convention of 1899 were the Washington Conference of 1887, the Treaty of Berlin of 1889, and the Anglo-German Agreement on Samoa of 1899. The following year, the U.S. formally annexed its portion, a smaller group of eastern islands, one of which contains the noted harbor of Pago Pago.[109] After the United States Navy took possession of eastern Samoa for the United States government, the existing coaling station at Pago Pago Bay was expanded into a full naval station, known as United States Naval Station Tutuila and commanded by a commandant. The Navy secured a Deed of Cession of Tutuila in 1900 and a Deed of Cession of Manuʻa in 1904 on behalf of the U.S. government. The last sovereign of Manuʻa, the Tui Manuʻa Elisala, signed a Deed of Cession of Manuʻa following a series of U.S. naval trials, known as the "Trial of the Ipu", in Pago Pago, Taʻu, and aboard a Pacific Squadron gunboat.[110] The territory became known as the U.S. Naval Station Tutuila. On July 17, 1911, the U.S. Naval Station Tutuila, which was composed of Tutuila, Aunuʻu and Manuʻa, was officially renamed American Samoa.[111][112] People of Manuʻa had been unhappy since they were left out of the name "Naval Station Tutuila". In May 1911, Governor William Michael Crose authored a letter to the Secretary of the Navy conveying the sentiments of Manuʻa. The department responded that the people should choose a name for their new territory. The traditional leaders chose "American Samoa", and, on July 7, 1911, the solicitor general of the Navy authorized the governor to proclaim it as the name for the new territory.[113]: 209 |

アメリカ領サモア アメリカ合衆国、ドイツ帝国、イギリスは、第二次サモア内戦の終結時に1899年の三国間条約に参加した。その結果、サモア諸島は正式に分割され、ドイツ 植民地と現在のアメリカ領サモアと呼ばれるアメリカ合衆国領となった。アメリカ合衆国は1900年にツツイラ島、1904年にマヌア諸島、1925年にス ウェインズ島を併合した[105]。[106] 東サモア諸島はアメリカ合衆国の領土となった。[107] 陸地面積がはるかに広い西側の諸島は、イギリスがサモアに対する全ての権利を放棄する代わりに、トンガ及びソロモン諸島と西アフリカの特定地域におけるド イツの権利の終了を受け入れた後、ドイツ領サモアとして知られるようになった。[108] 1899年の三国協定の前身は、1887年のワシントン会議、1889年のベルリン条約、そして1899年のサモアに関する英独協定であった。 翌年、アメリカは自国領となる東部諸島(規模は小さいが、有名なパゴパゴ港を有する島を含む)を正式に併合した。[109] アメリカ海軍が東部サモアをアメリカ政府のために占領した後、パゴパゴ湾に存在した石炭補給基地は拡張され、アメリカ海軍基地ツツイラとして司令官の指揮 下に入った。海軍は1900年にツツイラ割譲証書、1904年にマヌア割譲証書をアメリカ政府に代わって確保した。マヌアの最後の首長であるトゥイ・マヌ ア・エリサラは、パゴパゴ、タウ、太平洋艦隊砲艦上で行われた一連の米国海軍による裁判(「イプの裁判」として知られる)を経て、マヌア割譲証書に署名し た。この地域は米国海軍基地ツツイラとして知られるようになった。 1911年7月17日、ツツィラ島、アヌウ島、マヌア島で構成されていた「米国海軍基地ツツィラ」は正式に「アメリカ領サモア」と改称された[111] [112]。マヌアの人々は「海軍基地ツツィラ」という名称から除外されたことに不満を抱いていた。1911年5月、ウィリアム・マイケル・クロス総督は マヌアの意向を伝える書簡を海軍長官に送った。海軍省は、人民が新領土の名称を選ぶべきだと回答した。伝統的指導者たちは「アメリカ領サモア」を選択し、 1911年7月7日、海軍法務総監は総督に対し、新領土の名称としてこれを公布することを承認した。[113]: 209 |

| Insular cases Main article: Insular cases The acquisition of Hawaii, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Guam, and American Samoa marked a new chapter in U.S. history. Traditionally, territories were acquired by the United States for the purpose of becoming new states on equal footing with already existing states. These islands were acquired as colonies rather than prospective states. The process was validated by the Insular Cases. The Supreme Court ruled that full constitutional rights did not automatically extend to all areas under American control.[114] The Philippines became independent in 1946 and Hawaii became a state in 1959, but Puerto Rico, Guam, and American Samoa remain territories.[54] According to Frederick Merk, these colonial acquisitions marked a break from the original intention of manifest destiny. Previously, "Manifest Destiny had contained a principle so fundamental that a Calhoun and an O'Sullivan could agree on it—that a people not capable of rising to statehood should never be annexed. That was the principle thrown overboard by the imperialism of 1899."[115] Albert J. Beveridge maintained the contrary at his September 25, 1900, speech in the Auditorium, at Chicago. He declared that the current desire for Cuba and the other acquired territories was identical to the views expressed by Washington, Jefferson and Marshall. Moreover, "the sovereignty of the Stars and Stripes can be nothing but a blessing to any people and to any land."[116] The nascent revolutionary government, desirous of independence, resisted the United States in the Philippine–American War in 1899; it won no support from any government anywhere and collapsed when its leader was captured. William Jennings Bryan denounced the war and any form of future overseas expansion, writing, "'Destiny' is not as manifest as it was a few weeks ago."[117] |

島嶼領土問題 詳細な記事: 島嶼領土問題 ハワイ、フィリピン、プエルトリコ、グアム、アメリカ領サモアの獲得は、米国史における新たな章を刻んだ。従来、米国が領土を獲得する際は、既存の州と同 等の立場で新たな州となることを目的としていた。しかしこれらの島々は、将来の州候補としてではなく、植民地として獲得されたのである。この過程は島嶼事 件によって正当化された。最高裁判所は、完全な憲法上の権利が米国の支配下にある全ての地域に自動的に及ぶわけではないと判決した[114]。フィリピン は1946年に独立し、ハワイは1959年に州となったが、プエルトリコ、グアム、アメリカ領サモアは依然として準州のままである。[54] フレデリック・マークによれば、これらの植民地獲得はマニフェスト・デスティニーの本来の意図からの断絶を意味した。以前「マニフェスト・デスティニーに は、カルフーンとオサリバンが合意できるほど根本的な原則が含まれていた——州としての地位に到達できない人民は決して併合されるべきではない、という原 則だ。それが1899年の帝国主義によって見捨てられた原則である」 [115] アルバート・J・ベヴァリッジは1900年9月25日、シカゴのオーディトリアムでの演説で反対意見を主張した。彼は、キューバやその他の獲得領土に対す る現在の願望は、ワシントン、ジェファーソン、マーシャルが表明した見解と同一であると宣言した。さらに、「星条旗の主権は、いかなる人民や土地にとって も祝福以外の何物でもない」と述べた。[116] 独立を望む新生革命政府は、1899年の米西戦争でアメリカに抵抗したが、いかなる政府からも支援を得られず、指導者が捕らえられたことで崩壊した。ウィ リアム・ジェニングス・ブライアンはこの戦争と将来のあらゆる形態の海外拡張を非難し、「『運命』は数週間前ほど明白ではない」と記した。[117] |

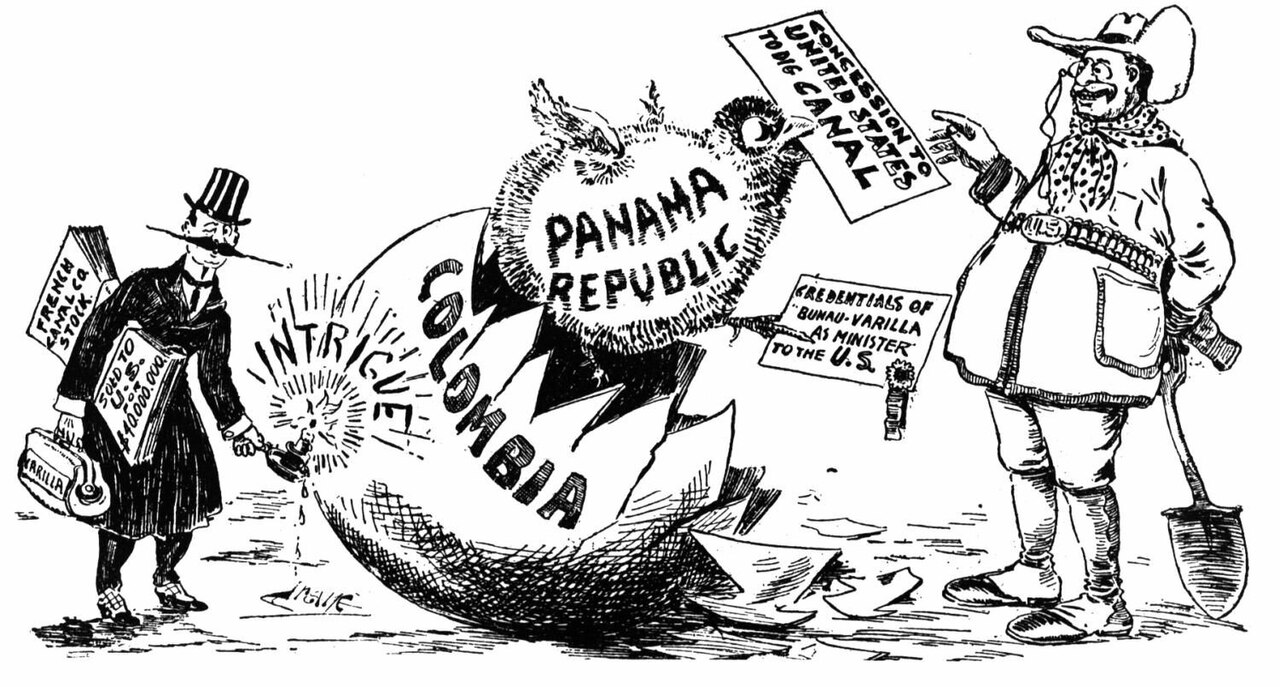

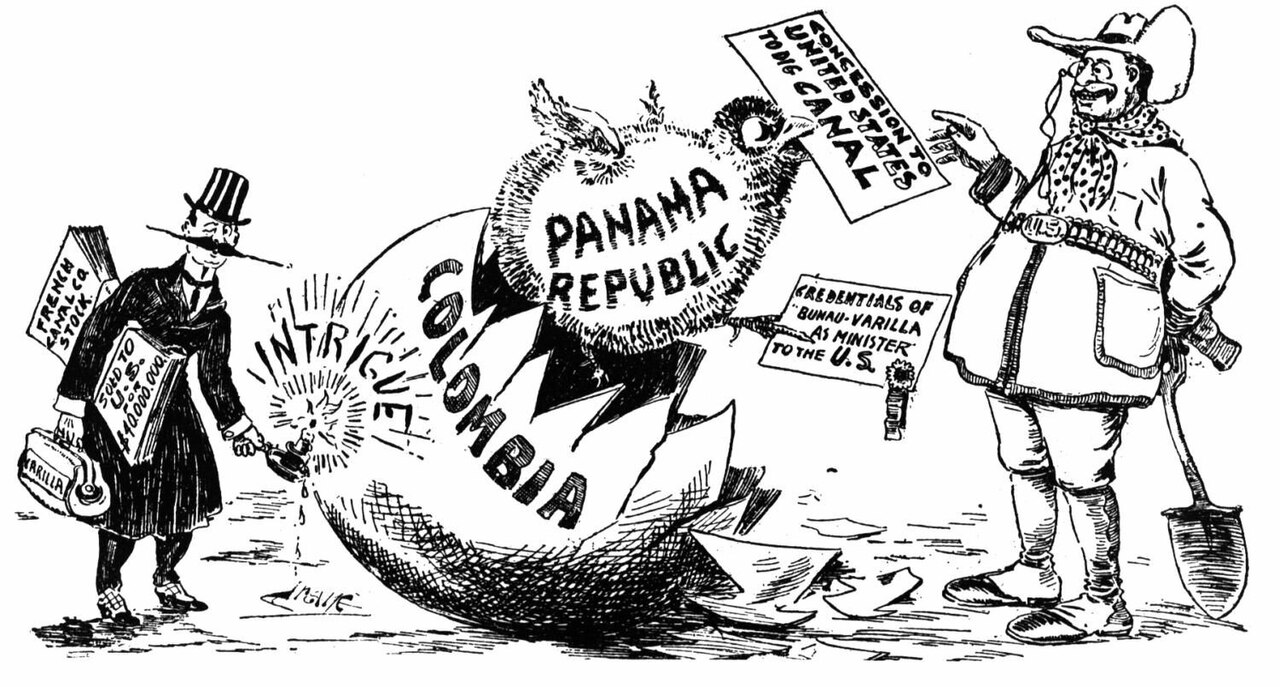

| 20th-century reforms In 1917, all Puerto Ricans were made full American citizens via the Jones Act, which also provided for a popularly elected legislature and a bill of rights, and authorized the election of a Resident Commissioner who has a voice (but no vote) in Congress.[118] In 1934, the Tydings–McDuffie Act put the Philippines on a path to independence, which was realized in 1946 with the Treaty of Manila. The Guam Organic Act of 1950 established Guam alongside Puerto Rico as an unincorporated unorganized territory of the United States, provided for the structure of the island's civilian government, and granted the people U.S. citizenship. 21st century Main article: American expansionism under Donald Trump In 2025, Donald Trump became the first president to use the phrase "manifest destiny" during an inaugural address,[119] declaring an extension of American influence "into the stars" with ambitions to plant the U.S. flag on Mars.[120] Since being elected, Trump has suggested at various points to annex Canada, Greenland, and the Panama Canal, to invade Venezuela and Mexico,[121] and to take over the Gaza Strip. |

20世紀の改革 1917年、ジョーンズ法により全てのプエルトリコ人は完全なアメリカ市民権を得た。同法は民選議会と権利章典を定めるとともに、議会で発言権(ただし投 票権はない)を持つ居住委員の選出を認めた。[118] 1934年、タイディングス・マクダフィー法がフィリピンを独立への道に導き、1946年のマニラ条約で独立が実現した。1950年のグアム有機法は、グ アムをプエルトリコと並んで米国の非法人非組織領土と定め、島の民政の構造を規定し、人民に米国市民権を与えた。 21 世紀 主な記事:ドナルド・トランプ政権下のアメリカの拡張主義 2025 年、ドナルド・トランプは就任演説で「マニフェスト・デスティニー」という表現を使用した最初の大統領となり[119]、火星にアメリカの国旗を立てると いう野望とともに、アメリカの影響力を「星々まで」拡大することを宣言した。[120] 選出以来、トランプは、カナダ、グリーンランド、パナマ運河を併合し、ベネズエラとメキシコに侵攻し[121]、ガザ地区を乗っ取ることをさまざまな場面 で示唆してきた。 |