Impression

management

Mascot character, Satoko-chan, born in 1982, by Sato Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Japan,

印象管理

Impression

management

Mascot character, Satoko-chan, born in 1982, by Sato Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Japan,

池田光穂

★印象管理(Impression

management)

とは、社会的相互作用の中で情報を調整・制御することによって、ある人物、物体、出来事に関する他者の認識に影響を与えようとする意識的または潜在意識的

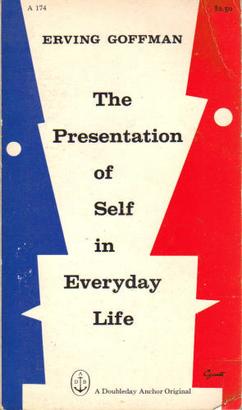

なプロセスである[1]。1959年にアーヴィング・ゴフマンが『日常生活における自己提示』で初めて概念化し、その後1967年に拡張された。

印象管理行動には、説明(「不評を買うのを避けるために否定的な出来事について説明すること」)、弁解(「否定的な結果に対する責任」を否定すること)、

意見適合(「ターゲットと一致する方法で話したり振る舞ったりすること」)などがあり、他にも多くの行動がある[2]。これらの行動を利用することによ

り、印象管理をしている人は自分または自分に関連する出来事に対する他者の認識をコントロールすることができる。印象管理は、スポーツ(派手な服を着た

り、自分の技術をファンに印象づけようとする)、ソーシャルメディア(ポジティブな投稿だけを共有する)など、ほぼすべての状況で可能です。印象管理は、

善意でも悪意でも使用することができる。

印象管理は通常、自己呈示と同義に使われ、人が自分のイメージの認知に影響を与えようとするものである。印象管理の概念は、最初は対面でのコミュニケー

ションに適用されましたが、その後、コンピュータを介したコミュニケーションにも適用されるようになった。インプレッション・マネジメントの概念は、心理

学や社会学などの学問分野だけでなく、企業コミュニケーションやメディアなどの実務分野にも適用可能である。

| Impression

management Impression management is a conscious or subconscious process in which people attempt to influence the perceptions of other people about a person, object or event by regulating and controlling information in social interaction.[1] It was first conceptualized by Erving Goffman in 1959 in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, and then was expanded upon in 1967. Impression management behaviors include accounts (providing "explanations for a negative event to escape disapproval"), excuses (denying "responsibility for negative outcomes"), and opinion conformity ("speak(ing) or behav(ing) in ways consistent with the target"), along with many others.[2] By utilizing such behaviors, those who partake in impression management are able to control others' perception of them or events pertaining to them. Impression management is possible in nearly any situation, such as in sports (wearing flashy clothes or trying to impress fans with their skills), or on social media (only sharing positive posts). Impression management can be used with either benevolent or malicious intent. Impression management is usually used synonymously with self-presentation, in which a person tries to influence the perception of their image. The notion of impression management was first applied to face-to-face communication, but then was expanded to apply to computer-mediated communication. The concept of impression management is applicable to academic fields of study such as psychology and sociology as well as practical fields such as corporate communication and media. |

印象管理 印象管理とは、社会的相互作用の中で情報を調整・制御することによっ て、ある人物、物体、出来事に関する他者の認識に影響を与えようとする意識的または潜在意識的なプロセスである[1]。1959年にアーヴィング・ゴフマ ンが『日常生活における自己提示』で初めて概念化し、その後1967年に拡張された。 印象管理行動には、説明(「不評を買うのを避けるために否定的な出来事について説明すること」)、弁解(「否定的な結果に対する責任」を否定すること)、 意見適合(「ターゲットと一致する方法で話したり振る舞ったりすること」)などがあり、他にも多くの行動がある[2]。これらの行動を利用することによ り、印象管理をしている人は自分または自分に関連する出来事に対する他者の認識をコントロールすることができる。印象管理は、スポーツ(派手な服を着た り、自分の技術をファンに印象づけようとする)、ソーシャルメディア(ポジティブな投稿だけを共有する)など、ほぼすべての状況で可能です。印象管理は、 善意でも悪意でも使用することができる。 印象管理は通常、自己呈示と同義に使われ、人が自分のイメージの認知に影響を与えようとするものである。印象管理の概念は、最初は対面でのコミュニケー ションに適用されましたが、その後、コンピュータを介したコミュニケーションにも適用されるようになった。インプレッション・マネジメントの概念は、心理 学や社会学などの学問分野だけでなく、企業コミュニケーションやメディアなどの実務分野にも適用可能である。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impression_management | |

| Background | 背景 |

| The foundation and the defining principles of impression management were created by Erving Goffman in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Impression management theory states that one tries to alter one's perception according to one's goals. In other words, the theory is about how individuals wish to present themselves, but in a way that satisfies their needs and goals. Goffman "proposed to focus on how people in daily work situations present themselves and, in so doing, what they are doing to others", and he was "particularly interested in how a person guides and controls how others form an impression of them and what a person may or may not do while performing before them".[3] | 印象管理の基礎と定義原理は、アービング・ゴフマンの『日常生活におけ る自己の提示』によって確立された。印象管理理論は、個人が自らの目標に応じて他者 の自己認識を変えようと試みることを説く。つまり、この理論は個人が自己をどのように提示したいか、しかしその方法が自身のニーズや目標を満たすものであ るかについて論じている。ゴフマンは「日常的な職場状況において人々が自己をどのように提示し、それによって他者に何をしているかに焦点を当てることを提 案した」とされ、「特に、個人が他者の自己に対する印象形成をいかに誘導・制御するか、また他者の前で行動する際に個人が行うこと・行わないことに関心を 持っていた」[3]。 |

| Theory | 理論 |

| Motives Impression management can be found in all social interactions, whether real or imaginary, and is governed by a range of factors. The characteristics of a given social situation are important; specifically, the surrounding cultural norms determine the appropriateness of particular nonverbal behaviors.[4] The actions and exchange have to be appropriate to the targets, and within that culture's norms. Thus, the nature of the audience and its relationship with the speaker influences the way impression management is realized. The awareness of being a potential subject of monitoring is also crucial. A person's goals inform the strategies of impression management, and can influence how they are received. This leads to distinct ways of presenting the self. Self-efficacy describes whether a person is convinced that it is possible to convey the intended impression.[5] Conmen, for instance, can rely on their ability to emanate self-assuredness in the process of gaining a mark's trust. There is evidence that, all other things being equal, people are more likely to pay attention to faces associated with negative gossip compared to those with neutral or positive associations.[6] This contributes to a body of work indicating that, far from being objective, human perceptions are shaped by unconscious brain processes that determine what they "choose" to see or ignore—even before a person is consciously aware of it. The findings also add to the idea that the brain evolved to be particularly sensitive to "bad guys" or cheaters—fellow humans who undermine social life by deception, theft or other non-cooperative behavior.[6] There are many methods behind self-presentation, including self-disclosure (identifying what makes you "you" to another person), managing appearances (trying to fit in), ingratiation, aligning actions (making one's actions seem appealing or understandable), and alter-casting (imposing identities onto other people). Maintaining a version of self-presentation that is generally considered to be attractive can help to increase one's social capital; this method is commonly used at networking events. These self-presentation methods can also be used by corporations for impression management with the public.[1][7] |

動機 印象管理は、現実であれ想像であれ、あらゆる社会的相互作用に見られ、様々な要因によって支配される。特定の社会的状況の特徴は重要であり、特に周囲の文 化的規範が特定の非言語的行動の適切性を決定する。[4] 行動や交流は対象者に適したものであり、その文化の規範の範囲内で行われなければならない。したがって、聴衆の性質や話者との関係性が、印象管理の実現方 法に影響を与えるのである。 監視の対象となり得るという自覚も重要だ。人格の目標は印象管理の戦略を決定し、その受け止め方に影響を与えうる。これは自己を提示する明確な方法へとつ ながる。自己効力感とは、意図した印象を伝えられると人格が確信しているかどうかを示す。[5] 例えば詐欺師は、標的の信頼を得る過程で、自信に満ちた態度を醸し出す能力に頼ることができる。 他の条件が同じ場合、人々は中立的または肯定的なイメージを持つ顔よりも、否定的な噂と結びついた顔に注意を向ける傾向が強いという証拠がある。[6] これは、人間の知覚が客観的とは程遠く、意識的に認識する以前に、脳が無意識的に「選択」して見るものや無視するものを決定するプロセスによって形作られ ることを示す一連の研究に貢献している。この知見はまた、脳が特に「悪者」や詐欺師——欺瞞、窃盗、その他の非協力的な行動によって社会生活を損なう仲間 ——に対して敏感になるように進化したという考えを補強するものである。[6] 自己表現には多くの手法がある。自己開示(相手に「自分らしさ」を伝える)、外見管理(周囲に溶け込もうとする)、媚びへつらい、行動調整(自身の行動を 魅力的・理解可能に見せる)、他者への役割付与(他人にアイデンティティを押し付ける)などだ。一般的に魅力的と見なされる自己提示を維持することは、個 人の社会的資本を高めるのに役立つ。この手法はネットワーキングイベントでよく用いられる。また企業も、公衆に対する印象管理のためにこれらの自己提示手 法を活用できる。[1][7] |

| Self-presentation | 自己表現 |

| Self-presentation is conveying

information about oneself – or an image

of oneself – to others. There are two types and motivations of

self-presentation: presentation meant to match one's own self-image, and presentation meant to match audience expectations and preferences.[8] Self-presentation is expressive. Individuals construct an image of themselves to claim personal identity, and present themselves in a manner that is consistent with that image. If they feel like it is restricted, they often exhibit reactance or become defiant – try to assert their freedom against those who would seek to curtail self-presentation expressiveness. An example of this dynamic is someone who grew up with extremely strict or controlling parental figures. The child in this situation may feel that their identity and emotions have been suppressed, which may cause them to behave negatively towards others. Boasting – Millon notes that in self-presentation individuals are challenged to balance boasting against discrediting themselves via excessive self-promotion or being caught and being proven wrong. Individuals often have limited ability to perceive how their efforts impact their acceptance and likeability by others.[9] Flattery – flattery or praise to increase social attractiveness[10] Intimidation – aggressively showing anger to get others to hear and obey one's demands.[11] Self-presentation can be either defensive or assertive strategies (also described as protective versus acquisitive).[12] Whereas defensive strategies include behaviours like avoidance of threatening situations or means of self-handicapping, assertive strategies refer to more active behaviour like the verbal idealisation of the self, the use of status symbols or similar practices.[13] These strategies play important roles in one's maintenance of self-esteem.[14] One's self-esteem is affected by their evaluation of their own performance and their perception of how others react to their performance. As a result, people actively portray impressions that will elicit self-esteem enhancing reactions from others.[15] In 2019, as filtered photos are perceived as deceptive by users, PlentyOfFish along with other dating sites have started to ban filtered images.[16] |

自己表現とは、自分自身に関する情報、あるいは自己のイメージを他者に

伝える行為である。自己表現には二つの種類と動機がある: 自己イメージに合わせるための表現、そして 聴衆の期待や好みに合わせるための表現である。[8] 自己表現は表現的である。人格は自己のアイデンティティを主張するために自己像を構築し、そのイメージと整合する形で自己を提示する。自己表現の自由が制 限されると感じると、しばしば抵抗感や反抗心を示す――自己表現の表現性を制限しようとする者に対して自由を主張しようとするのだ。この力学の一例が、過 度に厳格または支配的な親のもとで育った人格である。この状況の子は、自分のアイデンティティや感情が抑圧されたと感じ、他者に対して否定的な行動を取る 可能性がある。 自慢 – ミロンは、自己表現において個人が直面する課題として、過剰な自己宣伝による信用失墜や、嘘が露見して誤りを証明されるリスクと自慢行為のバランスを取る ことだと指摘する。個人は、自身の努力が他者からの受容や好感度にどう影響するかを認識する能力が限られていることが多い。[9] お世辞 – 社会的魅力を高めるためのお世辞や称賛[10] 威圧 – 怒りを攻撃的に示し、相手に要求を聞き入れ従わせる行為。[11] 自己提示は防御的戦略か断定的戦略(保護的対獲得的とも呼ばれる)のいずれかである[12]。防御的戦略には脅威的な状況の回避や自己ハンディキャップ行 為が含まれる一方、断定的戦略は自己の言語的理想化、ステータスシンボルの使用などのより積極的な行動を指す[13]。 これらの戦略は自己評価の維持において重要な役割を果たす。[14] 自尊心は、自身のパフォーマンス評価と、他者の反応に対する認識によって影響を受ける。結果として、人民は自尊心を高める反応を引き出す印象を積極的に演 じるのである。[15] 2019年、フィルター加工された写真がユーザーに欺瞞的と認識される中、PlentyOfFishをはじめとする出会い系サイトはフィルター画像の掲載 禁止を開始した。[16] |

| Social interaction See also: Social death and Social stress |

社会的相互作用 関連項目: 社会的死と社会的ストレス |

| Goffman argued in his 1967 book,

Interaction ritual, that people

participate in social interactions by performing a "line", or "pattern

of verbal and nonverbal acts", which is created and maintained by both

the performer and the audience.[17] By enacting a line effectively, the

person gains positive social value, which is also called "face". The

success of a social interaction will depend on whether the performer

has the ability to maintain face.[3] As a result, a person is required

to display a kind of character by becoming "someone who can be relied

upon to maintain himself as an interactant, poised for communication,

and to act so that others do not endanger themselves by presenting

themselves as interactants to him".[17] Goffman analyses how a human

being in "ordinary work situations presents himself and his activity to

others, the ways in which he guides and controls the impression they

form of him, and the kinds of things he may and may not do while

sustaining his performance before them".[18] When Goffman turned to focus on people physically presented in a social interaction, the "social dimension of impression management certainly extends beyond the specific place and time of engagement in the organization". Impression management is "a social activity that has individual and community implications".[3] We call it "pride" when a person displays a good showing from duty to himself, while we call it "honor" when he "does so because of duty to wider social units, and receives support from these duties in doing so".[17] Another approach to moral standards that Goffman pursues is the notion of "rules of conduct", which "can be partially understood as obligations or moral constraints". These rules may be substantive (involving laws, morality, and ethics) or ceremonial (involving etiquette).[3] Rules of conduct play an important role when a relationship "is asymmetrical and the expectations of one person toward another are hierarchical."[3] |

ゴフマンは1967年の著書『相互作用の儀礼』において、人民は「ライ

ン」、すなわち「言語的・非言語的行為のパターン」を演じることで社会的相互作用に

参加すると論じた。このラインは演者と観客の双方によって創出され維持されるものである[17]。ラインを効果的に演じることで、人格は「顔」とも呼ばれ

る肯定的な社会的価値を得る。社会的相互作用の成否は、演者が顔を維持できる能力にかかっている[3]。結果として、人は「相互作用者として自らを保ち、

コミュニケーションに備え、他者が相互作用者として振る舞うことで危険に晒されないように行動する、信頼できる人格」となることで、ある種の性格を示すこ

とが求められる。[17]

ゴフマンは「日常的な職場状況において、人間が自己と活動を他者に提示する方法、他者が形成する自己像を誘導・制御する手法、そして他者の前でパフォーマ

ンスを維持する際に許容される行為と許容されない行為」を分析する。[18] ゴフマンが社会的相互作用に物理的に存在する人々に焦点を移した時、「印象管理の社会的次元は、組織内での関与の特定の場所や時間を超越している」と述べ た。印象管理とは「個人と共同体双方に影響を及ぼす社会的活動」である。[3] 人格が自己への義務から立派な振る舞いを見せる場合を「誇り」と呼び、より広い社会単位への義務ゆえにそうし、その義務から支援を受ける場合を「名誉」と 呼ぶ。[17] ゴフマンが追求する道徳基準への別のアプローチは「行動規範」の概念であり、これは「義務や道徳的制約として部分的に理解できる」。これらの規範は実質的 (法律・道徳・倫理に関わる)か儀式的(礼儀作法に関わる)かのいずれかである。[3] 行動規範は「関係が非対称的で、一方の他者に対する期待が階層的である場合」に重要な役割を果たす。[3] |

| Dramaturgical analogy |

ドラマトゥルギー的類推 |

| Goffman presented impression

management dramaturgically, explaining the

motivations behind complex human performances within a social setting

based on a play metaphor.[19] Goffman's work incorporates aspects of a

symbolic interactionist perspective,[20] emphasizing a qualitative

analysis of the interactive nature of the communication process.

Impression management requires the physical presence of others.

Performers who seek certain ends in their interest, must "work to adapt

their behavior in such a way as to give off the correct impression to a

particular audience" and "implicitly ask that the audience take their

performance seriously".[3] Goffman proposed that while among other

people individual would always strive to control the impression that

others form of him or her so that to achieve individual or social

goals.[21] The actor, shaped by the environment and target audience, sees interaction as a performance. The objective of the performance is to provide the audience with an impression consistent with the desired goals of the actor.[22] Thus, impression management is also highly dependent on the situation.[23] In addition to these goals, individuals differ in responses from the interactive environment, some may be non-responsive to an audience's reactions while others actively respond to audience reactions in order to elicit positive results. These differences in response towards the environment and target audience are called self-monitoring.[24] Another factor in impression management is self-verification, the act of conforming the audience to the person's self-concept. The audience can be real or imaginary. IM style norms, part of the mental programming received through socialization, are so fundamental that we usually do not notice our expectations of them. While an actor (speaker) tries to project a desired image, an audience (listener) might attribute a resonant or discordant image. An example is provided by situations in which embarrassment occurs and threatens the image of a participant.[25] Goffman proposes that performers "can use dramaturgical discipline as a defense to ensure that the 'show' goes on without interruption."[3] Goffman contends that dramaturgical discipline includes:[3] 1. coping with dramaturgical contingencies; 2. demonstrating intellectual and emotional involvement; 3. remembering one's part and not committing unmeant gestures or faux pas; 4. not giving away secrets involuntarily; 5. covering up inappropriate behavior on the part of teammates on the spur of the moment; 6. offering plausible reasons or deep apologies for disruptive events; 7. maintaining self-control (for example, speaking briefly and modestly); 8. suppressing emotions to private problems; and 9. suppressing spontaneous feelings. |

ゴフマンは印象管理をドラマトゥルギー的に提示し、演劇の隠喩に基づい

て社会的状況における複雑な人間の演技の背後にある動機を説明した。[19]

ゴフマンの研究は象徴的相互作用論的視点の側面を取り入れ[20]、コミュニケーション過程の相互的性質の質的分析を強調している。印象管理には他者の物

理的な存在が必要である。特定の目的を追求する行為者は、「特定の観客に対して正しい印象を与えるよう自らの行動を調整する努力」をしなければならず、

「観客に自らの演技を真剣に受け止めるよう暗黙に要求する」のである[3]。ゴフマンは、個人は常に他者から形成される自己像を制御しようと努め、それに

よって個人的あるいは社会的目標を達成しようとする、と提唱した。[21] 環境と対象聴衆によって形作られる行為者は、相互作用を演技と捉える。演技の目的は、行為者の望む目標と整合する印象を聴衆に提供することにある。 [22] したがって、印象管理は状況に強く依存する。[23] これらの目的に加え、個人が相互作用環境に対して示す反応は異なる。観客の反応に無反応な人格もいれば、好ましい結果を引き出すために積極的に反応する人 格もいる。環境や対象観客に対するこうした反応の差異を自己監視と呼ぶ。[24] 印象管理における別の要素は自己検証であり、観客を自己概念に適合させる行為である。 聴衆は実在でも想像上でもよい。印象管理の様式規範は社会化を通じて受け継がれる精神的プログラムの一部であり、その規範は極めて根源的なため、我々は通 常、それらに対する期待に気づかない。演者(話者)が望ましいイメージを投影しようとする一方で、聴衆(聞き手)は共鳴するイメージや不協和なイメージを 帰属させることがある。参加者のイメージを脅かすような恥ずかしさが生じる状況がその例である。[25] ゴフマンは、演者たちが「『ショー』を中断なく続けるための防御手段として、ドラマトゥルギー的規律を利用できる」と提唱している[3]。ゴフマンによれ ば、ドラマトゥルギー的規律には以下が含まれる[3]: 1. ドラマトゥルギー的偶発事象への対処 2. 知的・感情的関与の示現 3. 自身の役割を記憶し、意図しない身振りや失態を犯さないこと; 4. 意図せず秘密を漏らさないこと; 5. チームメイトの不適切な行動をその場で隠蔽すること; 6. 混乱を招く出来事に対して、もっともらしい理由や深い謝罪を提示すること; 7. 自制心を保つこと(例えば、簡潔かつ控えめに話すこと); 8. 個人的な問題に対する感情を抑圧すること; 9. 自発的な感情を抑圧すること。 |

| Application | 応用 |

| Face-to-face communication Self, social identity and social interaction The social psychologist, Edward E. Jones, brought the study of impression management to the field of psychology during the 1960s and extended it to include people's attempts to control others' impression of their personal characteristics.[26] His work sparked an increased attention towards impression management as a fundamental interpersonal process. The concept of self is important to the theory of impression management as the images people have of themselves shape and are shaped by social interactions.[27] Our self-concept develops from social experience early in life.[28] Schlenker (1980) further suggests that children anticipate the effect that their behaviours will have on others and how others will evaluate them. They control the impressions they might form on others, and in doing so they control the outcomes they obtain from social interactions. Social identity refers to how people are defined and regarded in social interactions.[29] Individuals use impression management strategies to influence the social identity they project to others.[28] The identity that people establish influences their behaviour in front of others, others' treatment of them and the outcomes they receive. Therefore, in their attempts to influence the impressions others form of themselves, a person plays an important role in affecting his social outcomes.[30] Social interaction is the process by which we act and react to those around us. In a nutshell, social interaction includes those acts people perform toward each other and the responses they give in return.[31] The most basic function of self-presentation is to define the nature of a social situation (Goffman, 1959). Most social interactions are very role governed. Each person has a role to play, and the interaction proceeds smoothly when these roles are enacted effectively. People also strive to create impressions of themselves in the minds of others in order to gain material and social rewards (or avoid material and social punishments).[32] |

対面コミュニケーション 自己、社会的アイデンティティ、社会的相互作用 社会心理学者エドワード・E・ジョーンズは1960年代に印象管理の研究を心理学の分野に導入し、人格の特性に対する他者の印象を制御しようとする人民の 試みまで研究範囲を拡大した[26]。彼の研究は、印象管理が基本的な対人プロセスであるという認識を高めるきっかけとなった。 自己の概念は印象管理理論において重要である。なぜなら、人々が自らに抱くイメージは社会的相互作用によって形成され、また形成するからである[27]。 我々の自己概念は幼少期の社会的経験から発達する[28]。シュレンカー(1980)はさらに、子供たちは自らの行動が他者に与える影響や、他者が自分を どう評価するかを予測すると示唆している。彼らは他者に与える印象を制御し、それによって社会的相互作用から得られる結果を制御するのだ。 社会的アイデンティティとは、人民が社会的相互作用においてどのように定義され認識されるかを指す。[29] 個人は印象管理戦略を用いて、他者に投影する社会的アイデンティティに影響を与える。[28] 人民が確立するアイデンティティは、他者の前での行動、他者からの扱い、そして得られる結果に影響を及ぼす。したがって、他者が自分に対して抱く印象に影 響を与えようとする試みにおいて、人格は自らの社会的結果に影響を与える上で重要な役割を果たすのだ。[30] 社会的相互作用とは、周囲の人々に対して行動し反応する過程である。端的に言えば、社会的相互作用には人々が互いに対して行う行為と、それに対する返答が 含まれる。[31] 自己提示の最も基本的な機能は、社会的状況の本質を定義することである(Goffman, 1959)。ほとんどの社会的相互作用は役割によって大きく支配されている。各人格は果たすべき役割を持ち、これらの役割が効果的に演じられるとき、相互 作用は円滑に進む。人民はまた、物質的・社会的報酬を得るため(あるいは物質的・社会的罰を避けるため)、他者の心に自分自身の印象を創り出そうと努め る。[32] |

| Cross-cultural communication Understanding how one's impression management behavior might be interpreted by others can also serve as the basis for smoother interactions and as a means for solving some of the most insidious communication problems among individuals of different racial/ethnic and gender backgrounds (Sanaria, 2016).[1][33] "People are sensitive to how they are seen by others and use many forms of impression management to compel others to react to them in the ways they wish" (Giddens, 2005, p. 142). An example of this concept is easily illustrated through cultural differences. Different cultures have diverse thoughts and opinions on what is considered beautiful or attractive. For example, Americans tend to find tan skin attractive, but in Indonesian culture, pale skin is more desirable.[34] It is also argued that Women in India use different impression management strategies as compared to women in western cultures (Sanaria, 2016).[1] Another illustration of how people attempt to control how others perceive them is portrayed through the clothing they wear. A person who is in a leadership position strives to be respected and in order to control and maintain the impression. This illustration can also be adapted for a cultural scenario. The clothing people choose to wear says a great deal about the person and the culture they represent. For example, most Americans are not overly concerned with conservative clothing. Most Americans are content with tee shirts, shorts, and showing skin. The exact opposite is true on the other side of the world. "Indonesians are both modest and conservative in their attire" (Cole, 1997, p. 77).[34] One way people shape their identity is through sharing photos on social media platforms. The ability to modify photos by certain technologies, such as Photoshop, helps achieve their idealized images.[35] Companies use cross-cultural training (CCT) to facilitate effective cross-cultural interaction. CCT can be defined as any procedure used to increase an individual's ability to cope with and work in a foreign environment. Training employees in culturally consistent and specific impression management (IM) techniques provide the avenue for the employee to consciously switch from an automatic, home culture IM mode to an IM mode that is culturally appropriate and acceptable. Second, training in IM reduces the uncertainty of interaction with FNs and increases employee's ability to cope by reducing unexpected events.[33] |

異文化間コミュニケーション 自身の印象管理行動が他者にどう解釈されるかを理解することは、より円滑な交流の基盤となり得る。また、異なる人種・民族や性別の背景を持つ個人間の、最 も厄介なコミュニケーション問題の解決手段ともなり得る(Sanaria, 2016)。[1] [33] 「人民は他者からどう見られているかに敏感であり、様々な印象管理手法を用いて、他者に望む反応を引き出そうとする」(Giddens, 2005, p. 142)。この概念は文化の違いを通じて容易に説明できる。異なる文化は、何が美しく魅力的かについて多様な考えや意見を持つ。例えば、アメリカ人は日焼 けした肌を魅力的と感じる傾向があるが、インドネシア文化では色白の肌がより好まれる。[34] また、インドの女性は西洋文化の女性とは異なる印象管理戦略を用いるとも指摘されている(Sanaria, 2016)。[1] 人々が他者からの見られ方を制御しようとする別の例は、着る衣服を通じて描かれる。指導的立場にある者は、尊敬を得ようと努め、その印象を制御・維持しよ うとする。この例は文化的状況にも適用できる。人々が選ぶ服装は、その人格と彼らが代表する文化について多くを物語る。例えば、多くのアメリカ人は保守的 な服装を過度に気にかけない。Tシャツやショートパンツ、肌の露出に満足している。地球の反対側では全く逆の傾向が見られる。「インドネシア人は服装にお いて慎み深く保守的である」(Cole, 1997, p. 77)。[34] 人民が自己アイデンティティを形成する方法の一つは、ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームでの写真共有である。Photoshopなどの技術による写真加 工能力は、理想化されたイメージの実現を助ける。[35] 企業は効果的な異文化間交流を促進するため、異文化間トレーニング(CCT)を活用する。CCTとは、個人が異文化環境で対応し働く能力を高めるためのあ らゆる手順と定義できる。文化的に一貫した特定の印象管理(IM)技術を従業員に訓練することで、従業員は自発的に、母国文化の自動的なIMモードから、 文化的に適切で受け入れられるIMモードへ意識的に切り替える道が開かれる。第二に、IMの訓練は異文化の人々との交流における不確実性を減らし、予期せ ぬ出来事を減らすことで従業員の対応能力を高める。[33] |

| Team-working in hospital wards Impression management theory can also be used in health communication. It can be used to explore how professionals 'present' themselves when interacting on hospital wards and also how they employ front stage and backstage settings in their collaborative work.[36] In the hospital wards, Goffman's front stage and backstage performances are divided into 'planned' and 'ad hoc' rather than 'official' and 'unofficial' interactions.[36] Planned front stage is the structured collaborative activities such as ward rounds and care conferences which took place in the presence of patients and/or carers. Ad hoc front stage is the unstructured or unplanned interprofessional interactions that took place in front of patients/carers or directly involved patients/carers. Planned backstage is the structured multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT) in which professionals gathered in a private area of the ward, in the absence of patients, to discuss management plans for patients under their care. Ad hoc backstage is the use of corridors and other ward spaces for quick conversations between professionals in the absence of patients/carers. Offstage is the social activities between and among professional groups/individuals outside of the hospital context.[36] Results show that interprofessional interactions in this setting are often based less on planned front stage activities than on ad hoc backstage activities. While the former may, at times, help create and maintain an appearance of collaborative interprofessional 'teamwork', conveying a sense of professional togetherness in front of patients and their families, they often serve little functional practice. These findings have implications for designing ways to improve interprofessional practice on acute hospital wards where there is no clearly defined interprofessional team, but rather a loose configuration of professionals working together in a collaborative manner around a particular patient. In such settings, interventions that aim to improve both ad hoc as well as planned forms of communication may be more successful than those intended to only improve planned communication.[36] |

病院病棟におけるチームワーク 印象管理理論は健康コミュニケーションにも応用できる。専門家が病棟で交流する際の自己呈示方法や、共同作業における表舞台と裏舞台の設定活用法を考察す るのに有用だ。[36] 病院病棟では、ゴフマンの表舞台・裏舞台の演技は「公式/非公式」ではなく「計画的/臨機応変」な交流に分類される。[36] 計画的前舞台とは、患者や介護者の面前で行われる回診やケア会議といった構造化された共同活動である。 臨機応変な前舞台とは、患者・介護者の面前で発生する、あるいは患者・介護者を直接巻き込む、構造化されていない計画外の専門職間相互作用である。 計画的バックステージとは、患者不在の病棟内プライベートエリアに専門家が集まり、担当患者の管理計画を議論する構造化された多職種チーム会議(MDT) を指す。 臨機応変なバックステージとは、患者・介護者不在時に専門家同士が廊下や病棟スペースで交わす短時間の会話を指す。 オフステージとは、病院の文脈外における専門職グループ間・個人間の社交的活動を指す。[36] 結果から、この環境における専門職間交流は、計画的な表舞台活動よりも臨時の裏舞台活動に基づく場合が多いことが示された。前者は時に、患者やその家族の 前で専門職の結束感を伝える協働的な専門職間「チームワーク」の外観を創出・維持するのに役立つかもしれないが、機能的な実践としてはほとんど役立たない ことが多い。これらの知見は、明確に定義された専門職間チームが存在せず、特定の患者を中心に専門職が協働する緩やかな構成が取られている急性期病院病棟 における専門職間実践の改善策設計に示唆を与える。このような環境では、計画的なコミュニケーションのみを改善しようとする介入よりも、臨機応変なコミュ ニケーションと計画的なコミュニケーションの両方を改善することを目的とした介入の方が成功する可能性が高い。[36] |

| Computer-mediated communication The hyperpersonal model of computer-mediated communication (CMC) posits that users exploit the technological aspects of CMC in order to enhance the messages they construct to manage impressions and facilitate desired relationships. The most interesting aspect of the advent of CMC is how it reveals basic elements of interpersonal communication, bringing into focus fundamental processes that occur as people meet and develop relationships relying on typed messages as the primary mechanism of expression. "Physical features such as one's appearance and voice provide much of the information on which people base first impressions face-to-face, but such features are often unavailable in CMC. Various perspectives on CMC have suggested that the lack of nonverbal cues diminishes CMC's ability to foster impression formation and management, or argued impressions develop nevertheless, relying on language and content cues. One approach that describes the way that CMC's technical capacities work in concert with users' impression development intentions is the hyperpersonal model of CMC (Walther, 1996). As receivers, CMC users idealize partners based on the circumstances or message elements that suggest minimal similarity or desirability. As senders, CMC users selectively self-present, revealing attitudes and aspects of the self in a controlled and socially desirable fashion. The CMC channel facilitates editing, discretion, and convenience, and the ability to tune out environmental distractions and re-allocate cognitive resources in order to further enhance one's message composition. Finally, CMC may create dynamic feedback loops wherein the exaggerated expectancies are confirmed and reciprocated through mutual interaction via the bias-prone communication processes identified above."[37] According to O'Sullivan's (2000) impression management model of communication channels, individuals will prefer to use mediated channels rather than face-to-face conversation in face-threatening situations. Within his model, this trend is due to the channel features that allow for control over exchanged social information. The present paper extends O'Sullivan's model by explicating information control as a media affordance, arising from channel features and social skills, that enables an individual to regulate and restrict the flow of social information in an interaction, and present a scale to measure it. One dimension of the information control scale, expressive information control, positively predicted channel preference for recalled face-threatening situations. This effect remained after controlling for social anxiousness and power relations in relationships. O'Sullivan's model argues that some communication channels may help individuals manage this struggle and therefore be more preferred as those situations arise. It was based on an assumption that channels with features that allow fewer social cues, such as reduced nonverbal information or slower exchange of messages, invariably afford an individual with an ability to better manage the flow of a complex, ambiguous, or potentially difficult conversations.[38] Individuals manage what information about them is known, or isn't known, to control other's impression of them. Anyone who has given the bathroom a quick cleaning when they anticipate the arrival of their mother-in-law (or date) has managed their impression. For an example from information and communication technology use, inviting someone to view a person's Webpage before a face-to-face meeting may predispose them to view the person a certain way when they actually meet.[3] |

コンピュータ媒介コミュニケーション コンピュータ媒介コミュニケーション(CMC)のハイパーパーソナルモデルは、利用者がCMCの技術的側面を活用し、構築するメッセージを強化することで 印象を管理し、望ましい関係を促進すると主張する。CMCの出現で最も興味深い点は、それが対人コミュニケーションの基本要素を明らかにし、人民が主たる 表現手段として文字メッセージに依存して出会い、関係を築く際に生じる根本的なプロセスに焦点を当てることだ。「外見や声といった身体的特徴は、対面での 人民の第一印象形成の基盤となる情報の大半を提供する。しかしCMCではこうした特徴がしばしば欠如している。CMCに関する様々な見解は、非言語的手が かりの欠如が印象形成・管理を促進するCMCの能力を低下させると示唆したり、あるいは言語や内容の手がかりに依存して印象はそれでも形成されると主張し たりしてきた。」 CMCの技術的特性と利用者の印象形成意図が連動する仕組みを説明するアプローチとして、ハイパーパーソナル・モデル(Walther, 1996)がある。受信者として、CMC利用者は最小限の類似性や魅力が示唆される状況やメッセージ要素に基づき相手を理想化する。送信者として、CMC 利用者は選択的に自己を提示し、態度や自己の側面を制御された社会的に望ましい形で開示する。CMCチャネルは編集・選択・利便性を促進し、環境的干渉を 遮断し認知資源を再配分することでメッセージ構成をさらに強化する。最終的にCMCは動的フィードバックループを生成し、上述のバイアスを伴うコミュニ ケーション過程を通じた相互作用により、誇張された期待が確認・相互強化される。[37] オサリバン(2000)のコミュニケーションチャネルにおける印象管理モデルによれば、個人は面目を失う状況において、対面会話よりも媒介されたチャネル の使用を好む。同モデルでは、この傾向は交換される社会的情報を制御可能とするチャネル特性に起因するとされる。本論文はオサリバンのモデルを拡張し、情 報制御をチャネル特性と社会的スキルから生じるメディアアフォーダンスとして明示する。これは個人が相互作用における社会的情報の流れを調節・制限するこ とを可能にする。またこれを測定する尺度を提示する。情報制御尺度の1次元である「表現的情報制御」は、想起された面子を脅かす状況におけるチャネル選好 を正に予測した。この効果は、社会的不安や関係性における力関係を調整した後も持続した。オサリバンのモデルは、特定のコミュニケーションチャネルが個人 の葛藤管理を助けるため、そうした状況下でより好まれると論じている。このモデルは、非言語情報の減少やメッセージ交換の遅延など、社会的合図を少なくす る特徴を持つチャネルは、複雑で曖昧、あるいは困難になり得る会話の流れをより良く管理する能力を個人に与えると仮定している。[38]個人は、他者の自 分に対する印象を制御するため、自分に関する情報が知られるか、知られないかを管理する。義母(あるいはデート相手)の来訪を予期してトイレをさっと掃除 したことがある者なら誰でも、この印象管理を行ったことになる。情報通信技術の利用例を挙げれば、対面会議の前に自分のウェブページを閲覧するよう相手を 招待することは、実際に会った際に特定の印象を抱かせる素地を作り出す可能性がある。[3] |

| Corporate brand The impression management perspective offers potential insight into how corporate stories could build the corporate brand, by influencing the impressions that stakeholders form of the organization. The link between themes and elements of corporate stories and IM strategies/behaviours indicates that these elements will influence audiences' perceptions of the corporate brand.[39] Corporate storytelling Corporate storytelling is suggested to help demonstrate the importance of the corporate brand to internal and external stakeholders, and create a position for the company against competitors, as well as help a firm to bond with its employees (Roper and Fill, 2012). The corporate reputation is defined as a stakeholder's perception of the organization (Brown et al., 2006), and Dowling (2006) suggests that if the story causes stakeholders to perceive the organization as more authentic, distinctive, expert, sincere, powerful, and likeable, then it is likely that this will enhance the overall corporate reputation. Impression management theory is a relevant perspective to explore the use of corporate stories in building the corporate brand. The corporate branding literature notes that interactions with brand communications enable stakeholders to form an impression of the organization (Abratt and Keyn, 2012), and this indicates that IM theory could also therefore bring insight into the use of corporate stories as a form of communication to build the corporate brand. Exploring the IM strategies/behaviors evident in corporate stories can indicate the potential for corporate stories to influence the impressions that audiences form of the corporate brand.[39] Corporate document Firms use more subtle forms of influencing outsiders' impressions of firm performance and prospects, namely by manipulating the content and presentation of information in corporate documents with the purpose of "distort[ing] readers" perceptions of corporate achievements" [Godfrey et al., 2003, p. 96]. In the accounting literature this is referred to as impression management. The opportunity for impression management in corporate reports is increasing. Narrative disclosures have become longer and more sophisticated over the last few years. This growing importance of descriptive sections in corporate documents provides firms with the opportunity to overcome information asymmetries by presenting more detailed information and explanation, thereby increasing their decision-usefulness. However, they also offer an opportunity for presenting financial performance and prospects in the best possible light, thus having the opposite effect. In addition to the increased opportunity for opportunistic discretionary disclosure choices, impression management is also facilitated in that corporate narratives are largely unregulated.[citation needed] |

企業ブランド 印象管理の視点は、企業ストーリーがステークホルダーの組織に対する印象に影響を与えることで、企業ブランドを構築する可能性について示唆を与える。企業 ストーリーのテーマや要素と、印象管理戦略/行動との関連性は、これらの要素が対象者の企業ブランドに対する認識に影響を与えることを示している。 [39] 企業ストーリーテリング 企業ストーリーテリングは、社内外のステークホルダーに対して企業ブランドの重要性を示すこと、競合他社に対する企業のポジショニングを確立すること、そ して企業と従業員の絆を深めることに役立つとされている(Roper and Fill, 2012)。企業評判とは、ステークホルダーが組織に対して抱く認識と定義される(Brown et al., 2006)。Dowling(2006)は、ストーリーによってステークホルダーが組織をより「本物」「独自性」「専門性」「誠実」「力強さ」「好感」と 認識するようになれば、企業評判全体の向上につながり得ると示唆している。 企業ストーリーを用いた企業ブランド構築を考察する上で、印象管理理論は関連性のある視点である。企業ブランディング研究では、ブランドコミュニケーショ ンとの相互作用がステークホルダーの組織に対する印象形成に寄与すると指摘されている(Abratt and Keyn, 2012)。このことから、印象管理理論は企業ブランド構築のコミュニケーション手段としての企業ストーリー活用についても示唆を与える可能性がある。企 業ストーリーに顕在化する印象管理戦略/行動を探求することは、企業ストーリーが対象者の企業ブランドに対する印象形成に影響を与える可能性を示唆する。 [39] 企業文書 企業は、外部関係者の業績や将来性に対する印象に影響を与えるため、より巧妙な手法を用いる。具体的には、企業文書の情報内容や提示方法を操作し、「読者 の企業業績に対する認識を歪める」ことを目的とする[Godfrey et al., 2003, p. 96]。会計文献ではこれを印象管理と呼ぶ。企業報告書における印象管理の機会は増加している。ここ数年、説明的開示はより長く、より洗練されてきた。企 業文書における記述的セクションの重要性が高まることで、企業はより詳細な情報と説明を提示し、意思決定有用性を高めることで情報の非対称性を克服する機 会を得る。しかし同時に、財務実績や将来性を可能な限り好意的に提示する機会も提供し、逆の効果をもたらす。機会主義的な裁量的開示選択の機会が増加した ことに加え、企業ナラティブがほぼ規制されていない点も、印象管理を容易にしている。[出典が必要] |

| Media The medium of communication influences the actions taken in impression management. Self-efficacy can differ according to the fact whether the trial to convince somebody is made through face-to-face-interaction or by means of an e-mail.[24] Communication via devices like telephone, e-mail or chat is governed by technical restrictions, so that the way people express personal features etc. can be changed. This often shows how far people will go. The affordances of a certain medium also influence the way a user self-presents.[40] Communication via a professional medium such as e-mail would result in professional self-presentation.[41] The individual would use greetings, correct spelling, grammar and capitalization as well as scholastic language. Personal communication mediums such as text-messaging would result in a casual self-presentation where the user shortens words, includes emojis and selfies and uses less academic language. Another example of impression management theory in play is present in today's world of social media. Users are able to create a profile and share whatever they like with their friends, family, or the world. Users can choose to omit negative life events and highlight positive events if they so please.[42] Profiles on social networking sites Social media usage among American adults grew from 5% in 2005 to 69% in 2018.[43] Facebook is the most popular social media platform, followed by Instagram, LinkedIn, and Twitter.[43] Social networking users will employ protective self-presentations for image management. Users will use subtractive and repudiate strategies to maintain a desired image.[44] Subtractive strategy is used to untag an undesirable photo on Social Networking Sites. In addition to un-tagging their name, some users will request the photo to be removed entirely. Repudiate strategy is used when a friend posts an undesirable comment about the user. In response to an undesired post, users may add another wall post as an innocence defense. Michael Stefanone states that "self-esteem maintenance is an important motivation for strategic self-presentation online."[44] Outside evaluations of their physical appearance, competence, and approval from others determines how social media users respond to pictures and wall posts. Unsuccessful self-presentation online can lead to rejection and criticism from social groups. Social media users are motivated to actively participate in SNS from a desire to manage their online image.[45] Online social media presence often varies with respect to users' age, gender, and body weight. While men and women tend to use social media in comparable degrees, both uses and capabilities vary depending on individual preferences as well perceptions of power or dominance.[46] In terms of performance, men tend to display characteristics associated with masculinity as well as more commanding language styles.[46] In much the same way, women tend to present feminine self-depictions and engage in more supportive language.[46] With respect to usage across age variances, many children develop digital and social media literacy skills around 7 or 8 and begin to form online social relationships via virtual environments designed for their age group.[46] The years between thirteen and fifteen demonstrate high social media usage that begins to become more balanced with offline interactions as teens learn to navigate both their online and in-person identities which may often diverge from one another.[46] Social media platforms often provide a great degree of social capital during the college years and later.[46] College students are motivated to use Facebook for impression management, self-expression, entertainment, communication and relationship maintenance.[47] College students sometimes rely on Facebook to build a favorable online identity, which contributes to greater satisfaction with campus life.[47] In building an online persona, college students sometimes engage in identity manipulation, including altering personality and appearance, to increase their self-esteem and appear more attractive to peers.[48] Since risky behavior is frequently deemed attractive by peers, college students often use their social media profiles to gain approval by highlighting instances of risky behavior, like alcohol use and unhealthy eating.[49] Users present risky behavior as signs of achievement, fun, and sociability, participating in a form of impression management aimed at building recognition and acceptance among peers.[49] During middle adulthood, users tend to display greater levels of confidence and mastery in their social media connections while older adults tend to use social media for educational and supportive purposes.[46] These myriad factors influence how users will form and communicate their online personas. In addition to that, TikTok has made an influence on college students and adults to create their own self-image on a social media platform. The positivity of this is that college students and adults are using this to create their own brand for business purposes and for entertainment purposes. This gives them a chance to seek the desires of stardom and build an audience for revenue.[50] Media fatigue is a negative effect that is caused by the conveyance of social media presence. Social anxiety stems from low-self esteem which causes a strain of stress in one's self-identity that is perceived in the media limelight for targeted audiences.[51] According to Marwick, social profiles create implications such as "context collapse" for presenting oneself to the audience. The concept of 'context collapse' suggests that social technologies make it difficult to vary self-presentation based on environment or audience. "Large sites such as Facebook and Twitter group friends, family members, coworkers, and acquaintances together under the umbrella term 'friends'."[52] In a way, this context collapse is aided by a notion of performativity as characterized by Judith Butler. |

メディア コミュニケーションの媒体は、印象管理における行動に影響を与える。誰かを説得しようとする試みが、対面でのやり取りによって行われるか、電子メールに よって行われるかによって、自己効力感は異なる。[24] 電話、電子メール、チャットといったデバイスを介したコミュニケーションは技術的な制約に支配されるため、人々が人格の特徴などを表現する方法が変わる可 能性がある。これはしばしば、人々がどこまで踏み込むかを示す。 特定の媒体が持つアフォーダンスも、ユーザーの自己表現方法に影響を与える。[40] 電子メールのような専門的な媒体を介したコミュニケーションは、専門的な自己表現をもたらす。[41] 個人は挨拶、正しい綴り、文法、大文字の使用、そして学術的な言語を用いるだろう。テキストメッセージのような個人的なコミュニケーション媒体では、カ ジュアルな自己表現となる。ユーザーは単語を省略し、絵文字や自撮り写真を挿入し、学術的な言葉遣いを控える。 印象管理理論が作用する別の例は、現代のソーシャルメディアの世界に見られる。ユーザーはプロフィールを作成し、友人や家族、あるいは世界に向けて好きな ものを共有できる。ユーザーは望むなら、ネガティブな人生の出来事を省略し、ポジティブな出来事を強調することを選択できる。[42] ソーシャルネットワーキングサイトのプロフィール アメリカ成人のソーシャルメディア利用率は、2005年の5%から2018年には69%に増加した。[43] Facebookが最も人気のあるプラットフォームであり、次いでInstagram、LinkedIn、Twitterが続く。[43] ソーシャルネットワーキング利用者はイメージ管理のため、自己防衛的な自己表現を行う。望ましいイメージを維持するため、減算戦略と否認戦略を用いる。 [44]減算戦略はSNS上の好ましくない写真からタグを外すために用いられる。名前タグの解除に加え、写真を完全に削除するよう要求するユーザーもい る。否認戦略は、友人がユーザーについて望ましくないコメントを投稿した際に用いられる。望ましくない投稿への対応として、ユーザーは無実を主張する別の ウォール投稿を追加することがある。マイケル・ステファノーネは「自尊心の維持は、オンラインにおける戦略的自己表現の重要な動機である」と述べている。 [44] 自身の外見や能力に対する外部評価、他者からの承認が、ソーシャルメディアユーザーが写真やウォール投稿にどう反応するかを決定する。オンライン上での自 己表現が失敗すると、社会集団からの拒絶や批判を招く可能性がある。ソーシャルメディア利用者は、自身のオンライン上のイメージを管理したいという欲求か ら、SNSに積極的に参加する動機付けを受ける。[45] オンライン上のソーシャルメディアでの存在感は、利用者の年齢、性別、体重によって異なることが多い。男性と女性は同程度の頻度でソーシャルメディアを利 用する傾向があるが、利用方法や能力は個人の嗜好や、力や支配力に対する認識によって異なる。[46] パフォーマンスの面では、男性は男性性に関連する特徴やより威圧的な言語スタイルを示す傾向がある[46]。同様に、女性は女性的な自己描写を行い、より 支援的な言語を使う傾向がある[46]。 年齢層による利用状況を見ると、多くの子どもは7~8歳頃にデジタルリテラシーやソーシャルメディアリテラシーを身につけ、年齢層向けに設計された仮想環 境を通じてオンライン上の社会的関係を築き始める[46]。13歳から15歳の間はソーシャルメディア利用が最も高まる時期であり、オンラインとオフライ ンの人格(しばしば乖離する)を両立させる術を学ぶにつれ、両者のバランスが取れ始める。[46] ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームは、大学時代以降において多大な社会的資本を提供する。[46]大学生は、印象管理・自己表現・娯楽・コミュニケー ション・関係維持のためにFacebookを利用する動機を持つ。[47] 大学生は時にFacebookに依存し、好ましいオンライン上のアイデンティティを構築することで、キャンパスライフへの満足度を高める。[47] オンライン上の人格を構築する過程で、大学生は自己評価を高め、仲間からより魅力的に見られるよう、性格や外見を改変するなどのアイデンティティ操作を行 うことがある。[48] 危険な行動は仲間から魅力的に見られることが多いため、大学生はソーシャルメディアのプロフィールで、飲酒や不健康な食事といった危険行動を強調し、承認 を得ようとすることが多い。[49] ユーザーは危険な行動を、達成感や楽しさ、社交性の証として提示し、仲間からの認知と受容を得るための印象管理の一形態として参加している。[49] 中年期には、ユーザーはソーシャルメディア上のつながりにおいてより高い自信と熟達度を示す傾向がある一方、高齢者は教育や支援目的でソーシャルメディア を利用する傾向がある。[46] こうした多様な要因が、ユーザーがオンライン上のペルソナを形成し伝達する方法に影響を与える。加えて、TikTokは大学生や成人に対し、ソーシャルメ ディアプラットフォーム上で自己像を構築するよう影響を与えている。このポジティブな側面は、大学生や成人がビジネス目的や娯楽目的で自身のブランドを創 出するためにこれを利用している点だ。これにより、スターへの憧れを追求し、収益を得るための視聴者層を構築する機会が得られる。[50] メディア疲労は、ソーシャルメディア上の存在感の伝達によって引き起こされるネガティブな影響である。社会的不安は自尊心の低さに起因し、特定の視聴者を 対象としたメディアの脚光の中で認識される自己同一性にストレスの緊張をもたらす。[51] マーウィックによれば、ソーシャルプロフィールは視聴者への自己提示において「文脈崩壊」といった含意を生む。この「文脈崩壊」の概念は、ソーシャル技術 が環境や視聴者に応じて自己表現を変えにくくすることを示唆している。「FacebookやTwitterのような大規模サイトは、友人、家族、同僚、知 人を『友達』という包括的な用語の下にまとめてしまう」[52]。ある意味で、この文脈崩壊はジュディス・バトラーが特徴づけた「パフォーマティビティ」 という概念によって助長されている。 |

| Political impression management Impression management is also influential in the political spectrum. "Political impression management" was coined in 1972 by sociologist Peter M. Hall, who defined the term as the art of marking a candidate look electable and capable (Hall, 1972). This is due in part to the importance of "presidential" candidates—appearance, image, and narrative are a key part of a campaign and thus impression management has always been a huge part of winning an election (Katz 2016). Social media has evolved to be part of the political process, thus political impression management is becoming more challenging as the online image of the candidate often now lies in the hands of the voters themselves. The evolution of social media has increased the way in which political campaigns are targeting voters and how influential impression management is when discussing political issues and campaigns.[53] Political campaigns continue to use social media as a way to promote their campaigns and share information about who they are to make sure to lead the conversation about their political platform.[54] Research has shown that political campaigns must create clear profiles for each candidate in order to convey the right message to potential voters.[55] |

政治的印象管理 印象管理は政治分野でも影響力を持つ。「政治的印象管理」という概念は1972年に社会学者ピーター・M・ホールによって提唱され、候補者を当選可能で有 能に見せる技術と定義された(Hall, 1972)。これは「大統領」候補の重要性に起因する部分がある。外見、イメージ、物語性は選挙運動の重要な要素であり、したがって印象管理は常に選挙勝 利の大きな要素であった(Katz 2016)。ソーシャルメディアは政治プロセスの一部として進化したため、候補者のオンライン上のイメージが今や有権者自身の手に委ねられることが多くな り、政治的印象管理はより困難になっている。 ソーシャルメディアの進化は、政治キャンペーンが有権者をターゲットにする手法と、政治問題や選挙運動を議論する際の印象管理の影響力を増大させた [53]。政治キャンペーンは、自らの運動を促進し、自らの存在に関する情報を共有し、自らの政治的立場に関する議論を主導するために、ソーシャルメディ アを継続的に利用している[54]。研究によれば、政治キャンペーンは潜在的な有権者に適切なメッセージを伝えるために、各候補者について明確なプロ フィールを作成しなければならない[55]。 |

| In the workplace In professional settings, impression management is usually primarily focused on appearing competent,[56] but also involves constructing and displaying an image of oneself that others find socially desirable and believably authentic.[57][58] People manage impressions by their choice of dress, dressing either more or less formally, and this impacts perceptions their coworkers and supervisors form.[59] The process includes a give and take; the person managing their impression receives feedback as the people around them interact with the self they are presenting and respond, either favorably or negatively.[58] Research has shown impression management to be impactful in the workplace because the perceptions co-workers form of one another shape their relationships and indirectly influence their ability to function well as teams and achieve goals together.[60] In their research on impression management among leaders, Peck and Hogue define "impression management as conscious or unconscious, authentic or inauthentic, goal-directed behavior individuals engage in to influence the impression others form of them in social interactions."[60] Using those three dimensions, labelled "automatic" vs. "controlled", "authentic" vs. "inauthentic", and "pro-self" vs. "pro-social", Peck and Hogue formed a typology of eight impression management archetypes.[60] They suggest that while no one archetype stands out as the sole correct or ideal way to practice impression management as a leader, types rooted in authenticity and pro-social goals, rather than self-focused goals, create the most positive perceptions among followers.[60] Impression management strategies employed in the workplace also involve deception, and the ability to recognize deceptive acts impacts the supervisor-subordinate relationship as well as coworker relationships.[61] When it comes to workplace behaviors, ingratiation is the major focus of impression management research.[62] Ingratiation behaviors are those that employees engage in to elicit a favorable impression from a supervisor.[63][64] These behaviors can have a negative or positive impact on coworkers and supervisors, and this impact is dependent on how ingratiating is perceived by the target and those who observe the ingratiating behaviors.[63][64] The perception that follows an ingratiation act is dependent on whether the target attributes the behavior to the authentic-self of the person performing the act, or to impression management strategies.[65] Once the target is aware that ingratiation is resulting from impression management strategies, the target will perceive ethical concerns regarding the performance.[65] However, if the target attributes the ingratiation performance to the actor's authentic-self, the target will perceive the behavior as positive and not have ethical concerns.[65] Workplace leaders that are publicly visible, such as CEOs, also perform impression management with regard to stakeholders outside their organizations. In a study comparing online profiles of North American and European CEOs, research showed that while education was referenced similarly in both groups, profiles of European CEOs tended to be more professionally focused, while North American CEO profiles often referenced the CEO's public life outside business dealings, including social and political stances and involvement.[56] Employees also engage in impression management behaviors to conceal or reveal personal stigmas. How these individuals approach their disclosure of the stigma(s) impacts coworker's perceptions of the individual, as well as the individual's perception of themselves, and thus affects likeability amongst coworkers and supervisors.[66] On a smaller scale, many individuals choose to participate in professional impression management beyond the sphere of their own workplace. This may take place through informal networking (either face-to-face or using computer-mediated communication) or channels built to connect professionals, such as professional associations, or job-related social media sites, like LinkedIn. |

職場において 専門的な環境では、印象管理は主に有能に見えることに焦点を当てるが、同時に他者が社会的にも望ましく、信憑性のある本物だと感じる自己像を構築し示すこ とも含まれる。人々は服装の選択によって印象を管理し、よりフォーマルに、あるいはカジュアルに着ることで、同僚や上司が形成する認識に影響を与える。 [59] このプロセスには相互作用が含まれる。印象を管理する人格は、周囲の人民が提示された自己像と関わり、好意的または否定的に反応する中でフィードバックを 受ける。[58] 研究によれば、印象管理は職場で影響力を持つ。同僚同士が互いに形成する認識が人間関係を形作り、間接的にチームとしての機能や共同目標達成能力に影響を 与えるからだ。[60] リーダー層における印象管理の研究において、ペックとホーグは「印象管理とは、社会的相互作用において他者が形成する自己像に影響を与えるため、個人が意 識的または無意識的に、本心からまたは偽って、目標指向的に行う行動である」と定義している。[60] ペックとホグは「自動的 vs 制御的」「本物の vs 不自然な」「自己中心 vs 社会的」という3つの次元を用い、8つの印象管理アーキタイプを類型化した。[60] 彼らは、リーダーとして印象管理を実践する唯一の正しい方法や理想的な方法として突出した原型は存在しないが、自己中心的な目標ではなく、本物の自己と社 会志向の目標に根ざしたタイプが、部下の中で最も好意的な認識を生み出すと示唆している。[60] 職場で用いられる印象管理戦略には欺瞞も含まれ、欺瞞行為を認識する能力は上司と部下の関係や同僚関係に影響を与える。[61] 職場行動において、印象管理研究の主な焦点は媚びへつらいにある。[62] 媚びへつらい行動とは、従業員が上司から好印象を引き出すために行う行為である。[63] [64] こうした行動は同僚や上司に好悪両方の影響を与え、その影響は対象者や傍観者がご機嫌取りをどう認識するかによって決まる。[63][64] ご機嫌取り行為後の認識は、対象者がその行動を実行する人格の本心によるものと見なすか、それとも印象管理戦略によるものと見なすかによって左右される。 [65] 対象者がご機嫌取りが印象管理戦略によるものと認識した場合、その行動に対して倫理的な懸念を抱くようになる。[65] しかし、対象者がご機嫌取りを実行者の本心によるものと解釈した場合、その行動を肯定的に捉え、倫理的な懸念は生じない。[65] CEOなど公的に目立つ職場のリーダーは、組織外のステークホルダーに対しても印象管理を行う。北米と欧州のCEOのオンラインプロフィールを比較した研 究では、学歴の記載頻度は両グループで同程度であったが、欧州CEOのプロフィールはより専門職的傾向が強く、北米CEOのプロフィールではビジネス以外 の公的生活(社会的・政治的立場や関与など)が頻繁に言及されていた。[56] 従業員はまた、人格のスティグマを隠すか明らかにするために印象管理行動を行う。これらの個人がスティグマの開示にどう取り組むかは、同僚がその個人をど う認識するか、またその個人が自分自身をどう認識するかに影響し、結果として同僚や上司からの好感度に影響する。[66] より小規模なレベルでは、多くの個人が自身の職場の枠を超えて専門的な印象管理に参加することを選択する。これは非公式なネットワーキング(対面またはコ ンピュータ媒介コミュニケーション)や、専門家協会、LinkedInのような仕事関連のソーシャルメディアサイトなど、専門家をつなぐために構築された チャネルを通じて行われることがある。 |

| Implications Impression management can distort the results of empirical research that relies on interviews and surveys, a phenomenon commonly referred to as "social desirability bias". Impression management theory nevertheless constitutes a field of research on its own.[67] When it comes to practical questions concerning public relations and the way organizations should handle their public image, the assumptions provided by impression management theory can also provide a framework.[68] An examination of different impression management strategies acted out by individuals who were facing criminal trials where the trial outcomes could range from a death sentence, life in prison or acquittal has been reported in the forensic literature.[69] The Perri and Lichtenwald article examined female psychopathic killers, whom as a group were highly motivated to manage the impression that attorneys, judges, mental health professions and ultimately, a jury had of the murderers and the murder they committed. It provides legal case illustrations of the murderers combining and/or switching from one impression management strategy such as ingratiation or supplication to another as they worked towards their goal of diminishing or eliminating any accountability for the murders they committed. Since the 1990s, researchers in the area of sport and exercise psychology have studied self-presentation. Concern about how one is perceived has been found to be relevant to the study of athletic performance. For example, anxiety may be produced when an athlete is in the presence of spectators. Self-presentational concerns have also been found to be relevant to exercise. For example, the concerns may elicit motivation to exercise.[70] More recent research investigating the effects of impression management on social behaviour showed that social behaviours (e.g. eating) can serve to convey a desired impression to others and enhance one's self-image. Research on eating has shown that people tend to eat less when they believe that they are being observed by others.[71] |

示唆 印象管理は、インタビューや調査に依存する実証研究の結果を歪める可能性がある。この現象は一般に「社会的望ましさバイアス」と呼ばれる。とはいえ、印象 管理理論はそれ自体が研究分野を構成している。[67] 広報活動や組織が公的イメージをどう扱うべきかという実践的な問題に関しては、印象管理理論が提供する仮定も枠組みとなり得る。[68] 刑事裁判において死刑、終身刑、無罪判決といった異なる結果が想定される状況下で、個人が実践する印象管理戦略を検証した研究が法医学文献で報告されてい る。[69] ペリとリヒテンヴァルトの論文は、女性サイコパスの殺人者を対象とした。この集団は、弁護士、裁判官、精神保健専門家、そして最終的には陪審員が殺人者と 犯した殺人事件に対して抱く印象を管理することに強い動機を持っていた。論文は、殺人者が犯した殺人の責任を軽減または消去法による免除するという目標に 向けて、媚びへつらいや哀願といった印象管理戦略を組み合わせて、あるいは切り替えていく法的事例を提示している。 1990年代以降、スポーツ・運動心理学分野の研究者は自己呈示を研究してきた。他者からの見られ方への懸念は、運動能力の研究に関連することが判明して いる。例えば、観客の前で競技を行う際に不安が生じることがある。自己呈示への懸念は運動にも関連することが確認されている。例えば、こうした懸念が運動 意欲を引き起こすことがある。[70] 印象管理が社会的行動に及ぼす影響を調べた最近の研究では、社会的行動(例えば食事)が他者への望ましい印象の伝達や自己イメージの向上に役立つことが示 された。食事に関する研究では、人は他者に見られていると信じると食べる量が減る傾向があることが明らかになっている。[71] |

| Calculating Visions: Kennedy,

Johnson, and Civil Rights (book) Character mask Dignity Dramaturgy (sociology) First impression (psychology) Ingratiation Instagram's impact on people Online identity management On the Internet, nobody knows you're a dog Personal branding Register (sociolinguistics) Reputation capital Reputation management Self-monitoring theory Self-verification theory Signalling (economics) Spin (public relations) Superficial charm Stigma management |

計算されたビジョン:ケネディ、ジョンソン、そして公民権運動(書籍) キャラクターマスク 尊厳 ドラマトゥルギー(社会学) 第一印象(心理学) ご機嫌取り Instagramが人民に与える影響 オンライン上のアイデンティティ管理 インターネット上では、誰も君が犬だとは知らない パーソナルブランディング レジスター(社会言語学) 評判資本 評判管理 自己監視理論 自己検証理論 シグナリング(経済学) スピン(広報) 表面的な魅力 スティグマ管理 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impression_management |

|

| References Aronson, Elliot; Wilson, Timothy D; Akert, Robin M (2009). Social Psychology (Seventh ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Barnhart, Adam (1994), Erving Goffman: The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life Goffman, Erving (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday. Goffman, Erving (1956). "Embarrassment and Social Organization". The American Journal of Sociology. 62 (3): 264–71. doi:10.1086/222003. S2CID 144781932. Goffman, Erving (2006), Wir alle spielen Theater: Die Selbstdarstellung im Alltag, Piper, Munich. Dillard, Courtney et al. (2000), Impression Management and the use of procedures at the Ritz-Carlton: Moral standards and dramaturgical discipline, Communication Studies, 51. Döring, Nicola (1999), Sozialpsychologie des Internet: Die Bedeutung des Internet für Kommunikationsprozesse, Identitäten, soziale Beziehungen und Gruppen Hogrefe, Goettingen. Felson, Richard B (1984): An Interactionist Approach to Aggression, in: Tedeschi, James T. (Ed.), Impression Management Theory and Social Psychological Research Academic Press, New York. Sanaria, A. D. (2016). A conceptual framework for understanding the impression management strategies used by women in Indian organizations. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management, 3(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/2322093716631118[1] Hall, Peter (1972). "A Symbolic Interactionist Analysis of Politics." Sociological Inquiry 42.3-4: 35-75 Hass, Glen R. (1981), Presentational Strategies, and the Social Expression of Attitudes: Impression management within Limits, in: Tedeschi, James T. (Ed.): Impression Management Theory and Social Psychological Research, Academic Press, New York. Herman, Peter C; Roth, Deborah A; Polivy, Janet (2003). "Effects of the Presence of Others on Food Intake: A Normative Interpretation". Psychological Bulletin. 129 (6): 873–86. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.873. PMID 14599286. Humphreys, A. (2016). Social media: Enduring principles. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Katz, Nathan (2016). "Impression Management, Super PACs and the 2012 Republican Primary." Symbolic Interaction 39.2: 175–95. Leary, Mark R; Kowalski, Robin M (1990). "Impression Management: A Literature Review and Two-Component Model". Psychological Bulletin. 107 (1): 34–47. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.463.776. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.34. S2CID 15886705. Piwinger, Manfred; Ebert, Helmut (2001). "Impression Management: Wie aus Niemand Jemand wird". in: Bentele, Guenther et al. (Ed.), Kommunikationsmanagement: Strategien, Wissen, Lösungen. Luchterhand, Neuwied. Schlenker, Barry R. (1980). Impression Management: The Self-Concept, Social Identity, and Interpersonal Relations. Monterey, California: Brooks/Cole. Tedeschi, James T.; Riess, Marc (1984), Identities, the Phenomenal Self, and Laboratory Research, in: Tedeschi, James T. (Ed.): Impression Management Theory and Social Psychological Research, Academic Press, New York. Smith, Greg (2006), Erving Goffman, Routledge, New York. Rui, J. and M. A. Stefanone (2013). Strategic Management of Other-Provided Information Online: Personality and Network Variables. System Sciences (HICSS), 2013 46th Hawaii International Conference on. |

参考文献 アロンソン、エリオット、ウィルソン、ティモシー D、アカート、ロビン M (2009)。社会心理学 (第 7 版)。ニュージャージー州:プレンティス・ホール。 バーンハート、アダム (1994)、アービング・ゴフマン:日常生活における自己の表現 ゴフマン、アービング (1959)。日常生活における自己の表現。ニューヨーク:ダブルデイ。 ゴフマン、アービング (1956)。「恥ずかしさと社会組織」。アメリカ社会学雑誌。62 (3): 264–71. doi:10.1086/222003. S2CID 144781932. ゴフマン、アービング(2006)、『我々は皆、演劇を演じている:日常生活における自己表現』、パイパー、ミュンヘン。 ディラード、コートニー他(2000)、『印象管理とリッツ・カールトンの手順使用:道徳基準とドラマトゥルギカル規律』、コミュニケーション研究、 51。 ドリング、ニコラ(1999)『インターネット社会心理学:コミュニケーション過程、アイデンティティ、社会的関係、集団におけるインターネットの意義』 ホーグレフェ社、ゲッティンゲン。 フェルソン、リチャード・B(1984)『攻撃性への相互作用論的アプローチ』テデスキ、ジェームズ・T(編)『印象管理理論と社会心理学研究』アカデ ミック・プレス、ニューヨーク。 サナリア、A. D.(2016)。インドの組織における女性の印象管理戦略を理解するための概念的枠組み。南アジア人的資源管理ジャーナル、3(1)、25–39。 https://doi.org/10.1177/2322093716631118[1] ホール、ピーター(1972)。「政治の象徴的相互作用論的分析」『社会学研究』42巻3-4号: 35-75頁 ハス、グレン・R. (1981). 表出戦略と態度の社会的表現:限界内での印象管理. テデスキ、ジェームズ・T. (編): 『印象管理理論と社会心理学研究』アカデミック・プレス, ニューヨーク. ハーマン、ピーター・C; ロス、デボラ・A; ポリヴィー、ジャネット (2003). 「他者の存在が食物摂取に及ぼす影響:規範的解釈」. 心理学的レビュー. 129 (6): 873–86. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.873. PMID 14599286. ハンフリーズ, A. (2016). 『ソーシャルメディア:不変の原則』. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. カッツ, ネイサン (2016). 「印象管理、スーパーPAC、そして2012年共和党予備選挙」. 『象徴的相互作用』 39.2: 175–95. リアリー, マーク・R; コワルスキー、ロビン・M(1990)。「印象管理:文献レビューと二要素モデル」。『心理学的レビュー』107(1): 34–47。CiteSeerX 10.1.1.463.776。doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.34。S2CID 15886705. ピウィンガー, マンフレッド; エーベルト, ヘルムート (2001). 「印象管理:無名の人物が有名人になる過程」. ベントレ, ギュンター 他 (編), 『コミュニケーション管理:戦略、知識、解決策』所収. ルヒターハンド, ノイヴィート. シュレンカー, バリー・R. (1980). 印象管理:自己概念、社会的アイデンティティ、対人関係。カリフォルニア州モントレー:ブルックス/コール。 テデスキ、ジェームズ・T.;リース、マーク(1984)、「アイデンティティ、現象的自己、および実験室研究」、テデスキ、ジェームズ・T.(編)『印 象管理理論と社会心理学研究』、アカデミック・プレス、ニューヨーク。 スミス、グレッグ(2006)、アービング・ゴフマン、ラウトレッジ、ニューヨーク。 ルイ、J. および M. A. ステファノーネ(2013)。オンラインにおける他者提供情報の戦略的管理:人格とネットワーク変数。システム科学(HICSS)、2013年 第46回ハワイ国際会議。 |

★

以下の部分では、Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh, 1956) (Social Sciences Research Centre, Monograph no. 2)(行為と演技 : 日常生活における自己呈示 / E.ゴッフマン著 ; 石黒毅訳:東京 : 誠信書房 , 1974.11. - (ゴッフマンの社会学 / E・ゴッフマン著 ; 1))を検討する。(→ゴフマン (ゴッフマン)文献リスト)

この本は、彼の学位論文Communication Conduct in an Island Community. (PhD. dissertation, University of Chicago, 1953)が基礎になっており、学位取得後の3年後の1956年に出版された。ゴッフマン(ゴフマン)の出世作であり、彼の著作の中ではもっともよく読ま れる書物の1冊である。この本の章立ては次のようになっている。

============================

============================

| The

Presentation of Self in Everyday Life

is a 1956 sociological book by Erving Goffman, in which the author uses

the imagery of theatre to portray the importance of human social

interaction. This approach became known as Goffman's dramaturgical

analysis. Originally published in Scotland in 1956 and in the United States in 1959,[1] it is Goffman's first and most famous book,[2] for which he received the American Sociological Association's MacIver award in 1961.[3] In 1998, the International Sociological Association listed the work as the tenth most important sociological book of the 20th century.[4] |

『日常生活における自己の提示』は、アービング・ゴフマンによる

1956年の社会学書である。著者は演劇の比喩を用いて、人間の社会的相互作用の重要性を描いている。この手法はゴフマンのドラマトゥルギー分析として知

られるようになった。 1956年にスコットランドで、1959年にアメリカで出版された[1]。これはゴフマンの最初の著作であり、最も有名な本である[2]。この本により、 彼は1961年にアメリカ社会学会のマックアイバー賞を受賞した[3]。1998年、国際社会学会はこの著作を20世紀の最も重要な社会学書トップ10の 一つに選んだ[4]。 |

| Background and summary The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life was the first book to treat face-to-face interaction as a subject of sociological study. Goffman treats it as a kind of report in which he frames out the theatrical performance that applies to these interactions.[5] He believes that when an individual comes in contact with other people, that individual will attempt to control or guide the impression that others might make of him by changing or fixing his or her setting, appearance, and manner. At the same time, the person the individual is interacting with is trying to form and obtain information about the individual.[6] Believing that all participants in social interactions are engaged in practices to avoid being embarrassed or embarrassing others, Goffman developed his dramaturgical analysis, wherein he observes a connection between the kinds of acts that people put on in their daily life and theatrical performances. In social interaction, as in theatrical performance, there is a front region where the performers (individuals) are on stage in front of the audiences. This is where the positive aspect of the idea of self and desired impressions are highlighted. There is also a back region, where individuals can prepare for or set aside their role.[7] The "front" or performance that an actor plays out includes "manner," or how the role is carried out, and "appearance" including the dress and look of the performer. Additionally, “front” also includes the “setting”, which means the environment of performance. It can be a furniture, physical lay-out or the stage props.[8] Often, performers work together in "teams" and form bonds of collegiality based on their common commitment to the performance they are mutually engaged in. The core of Goffman's analysis lies in this relationship between performance and life. Unlike other writers who have used this metaphor, Goffman seems to take all elements of acting into consideration: an actor performs on a setting which is constructed of a stage and a backstage; the props in both settings direct his action; he is being watched by an audience, but at the same time he may be an audience for his viewers' play. According to Goffman, the social actor in many areas of life will take on an already established role, with pre-existing front and props as well as the costume he would wear in front of a specific audience. The actor's main goal is to keep coherent and adjust to the different settings offered him. This is done mainly through interaction with other actors. To a certain extent this imagery bridges structure and agency enabling each while saying that structure and agency can limit each other. |

背景と概要 『日常生活における自己の提示』は、対面的な相互作用を社会学的研究の対象として扱った最初の書籍である。ゴフマンはこれを一種の報告書として扱い、こう した相互作用に適用される演劇的パフォーマンスを枠組み化した[5]。彼は、個人が他者と接触する際、その個人は自身の環境、外見、態度を変えたり整えた りすることで、他者が自分に対して抱く印象を制御または誘導しようと試みると考えている。同時に、相互作用している相手もまた、その個人に関する情報を形 成し、得ようとしている。[6] 社会的相互作用の参加者全員が、恥ずかしい思いをさせたりさせられたりすることを避ける実践に従事していると考えるゴフマンは、演劇分析を展開した。そこ では、人々が日常生活で演じる行為の種類と演劇的パフォーマンスとの関連性が観察される。 社会的相互作用においては、演劇的パフォーマンスと同様に、出演者(個人)が観客の前に舞台に立つ「表側領域」が存在する。ここでは自己の肯定的側面や望 ましい印象が強調される。また「バック」領域も存在し、個人が役割の準備や解除を行う場所である。[7] 俳優が演じる「フロント」すなわち演技には、「マナー」(役割の遂行方法)と「外観」(衣装や外見を含む)が含まれる。さらに「表」には「設定」、つまり 演技の環境も含まれる。これは家具、物理的な配置、舞台装置を指す。[8] 多くの場合、演者は「チーム」として協力し、共に取り組む演技への共通のコミットメントに基づいて仲間意識の絆を形成する。 ゴフマンの分析の核心は、演技と生活の関係にある。この隠喩を用いた他の研究者とは異なり、ゴフマンは演技の全要素を考慮しているようだ:俳優は舞台と舞 台裏で構成される設定の上で演技する。両設定の小道具が彼の行動を導く。彼は観客に見られているが、同時に観客の演技に対する観客でもある。 ゴフマンによれば、生活の多くの領域において社会的行為者は、特定の観客の前で着用する衣装と同様に、あらかじめ存在する表舞台と小道具を備えた既成の役 割を引き受ける。行為者の主な目標は、一貫性を保ちながら与えられた異なる設定に適応することである。これは主に他の行為者との相互作用を通じて達成され る。この比喩はある程度、構造と主体性を橋渡しし、双方を可能にすると同時に、構造と主体性が互いに制限しうることを示している。 |

| Translated titles Since the metaphor of a theatre is the leading theme of the book, the German and consequently also the Czech translation used a fitting summary as the name of the book We All Play-Act (German: Wir Alle Spielen Theater; Czech: Všichni hrajeme divadlo), apart from the names in other languages that usually translate the title literally. Another translation, which also builds on the leading theatrical theme, rather than the original title, is the Swedish title of the book Jaget och Maskerna (The Self and the Masks). The French title is La Mise en scène de la vie quotidienne (The Staging of Everyday Life). Similarly, in the Polish language the book is known as Człowiek w teatrze życia codziennego (The Human in the Theatre of Everyday Life). |

翻訳されたタイトル 演劇の隠喩がこの本の主要なテーマであるため、ドイツ語訳およびそれに続くチェコ語訳では、他の言語のタイトルが通常直訳されるのとは異なり、適切な要約 を本の名称として採用した。すなわち『我々は皆、芝居を演じる』(ドイツ語: Wir Alle Spielen Theater、チェコ語: Všichni hrajeme divadlo)。別の翻訳例として、原題ではなく演劇的テーマを基にしたスウェーデン語版『自我と仮面』(原題:Jaget och Maskerna)がある。フランス語版は『日常生活の演出』(原題:La Mise en scène de la vie quotidienne)。同様にポーランド語版は『日常生活という劇場における人間』(原題:Człowiek w teatrze życia codziennego)として知られる。 |

| Concepts Definition of the situation A major theme that Goffman treats throughout the work is the fundamental importance of having an agreed upon definition of the situation in a given interaction, which serves to give the interaction coherency. In interactions or performances the involved parties may be audience members and performers simultaneously; the actors usually foster impressions that reflect well upon themselves and encourage the others, by various means, to accept their preferred definition. Goffman acknowledges that when the accepted definition of the situation has been discredited, some or all of the actors may pretend that nothing has changed, provided that they find this strategy profitable to themselves or wish to keep the peace. For example, when a person attending a formal dinner—and who is certainly striving to present himself or herself positively—trips, nearby party-goers may pretend not to have seen the fumble; they assist the person in maintaining face. Goffman avers that this type of artificial, willed credulity happens on every level of social organization, from top to bottom. Self-presentation theory The book proposes a theory of self that has become known as self-presentation theory, which suggests that people have the desire to control the impressions that other people form about them. The concept is still used by researchers in social media today, including Kaplan and Haenlein's Users of the World Unite (2010), Russell W. Belk's "Extended Self in a Digital World" (2013), and Nell Haynes' Social Media in Northern Chile: Posting the Extraordinarily Ordinary (2016). |

概念 状況の定義 ゴフマンが本書全体を通じて扱う主要なテーマは、特定の相互作用において状況の定義を合意することが、相互作用に一貫性をもたらす上で極めて重要だという 点だ。相互作用やパフォーマンスにおいて、関係者は観客と演者という二つの立場を同時に持つことがある。通常、行為者は自らを良く見せる印象を醸成し、様 々な手段で他者に自らの望む定義を受け入れさせるよう促す。ゴフマンは、状況の合意された定義が信用を失った場合でも、一部のまたは全ての行為者が何事も なかったかのように振る舞うことがあると認めている。ただし、この戦略が自身にとって有益であると判断した場合、あるいは平穏を保ちたい場合に限りであ る。例えば、正式な夕食会に出席している人格(当然ながら好印象を与えようと努めている)がつまずいた時、近くの出席者はその失敗を見ていないふりをする かもしれない。彼らはその人格が面目を保つのを助けるのである。ゴフマンは、この種の人為的で意図的な信憑性が、社会組織のあらゆる階層、上から下まで発 生すると断言する。 自己提示理論 本書は自己提示理論として知られるようになった自己の理論を提唱している。これは、人々が他者が自分について形成する印象を制御したいと望むことを示唆す る。 この概念は現在もソーシャルメディア研究で用いられており、カプランとヘーンラインの『世界のユーザーよ団結せよ』(2010年)、ラッセル・W・ベルク の「デジタル世界における拡張された自己」(2013年)、ネル・ヘインズの『チリ北部のソーシャルメディア:非凡なる日常の投稿』(2016年)などで 言及されている。 |

| Reception In 1961, Goffman received the American Sociological Association's MacIver award for The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.[3] Philosopher Helmut R. Wagner called the book "by far" Goffman's best book and "a still unsurpassed study of the management of impressions in face-to-face encounters, a form of not uncommon manipulation."[2] In 1998, the International Sociological Association listed The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life as the tenth most important sociological book of the twentieth century, behind Talcott Parsons' The Structure of Social Action (1937).[4] |

受容 1961年、ゴフマンは『日常生活における自己の提示』によりアメリカ社会学会のマックアイバー賞を受賞した。[3] 哲学者ヘルムート・R・ワグナーは本書を「断然」ゴフマンの最高傑作であり、「対面的な出会いで印象を管理する手法に関する未だに超えられていない研究で あり、決して珍しい操作ではない」と評した。[2] 1998年、国際社会学協会は『日常生活における自己の提示』を20世紀の最も重要な社会学書トップ10に選出した。順位はタルコット・パーソンズの『社 会行動の構造』(1937年)に次ぐ10位であった。[4] |

| 1. Macionis, John J., and Linda

M. Gerber. 2010. Sociology (7th Canadian ed.). Pearson Canada Inc. p.

11. 2. Wagner, Helmut R. (1983). Phenomenology of Consciousness and Sociology of the Life-world: An Introductory Study. Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press. p. 217. ISBN 0-88864-032-3. 3. Trevi-O, A. Javier (2003). Goffman's Legacy. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742519787. 4. "Books of the Century". International Sociological Association. 1998. Archived from the original on 2014-03-15. Retrieved 2012-07-25. 5. Smith, Greg (2006). Erving Goffman ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Hoboken: Routledge. pp. 33, 34. ISBN 978-0-203-00234-6. 6. Trevino, James. 2003. Goffman's Legacy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 35. 7. Ritzer, George. 2008. Sociological Theory. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. p. 372. 8. Goffman, Erving (1956). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Doubleday. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-14-013571-8. |

1.

マシオニス、ジョン・J.、リンダ・M・ガーバー共著(2010)。『社会学』(第7版カナダ版)。ピアソン・カナダ社。11頁。 2. ワグナー、ヘルムート・R.(1983)。『意識の現象学と生活世界の社会学:入門的研究』。エドモントン:アルバータ大学出版局。217頁。ISBN 0-88864-032-3. 3. トレヴィ=オー、A. ハビエル(2003)。『ゴフマンの遺産』。ローマン&リトルフィールド。ISBN 9780742519787。 4. 「世紀の書籍」. 国際社会学会. 1998. 2014年3月15日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2012年7月25日に閲覧. 5. スミス, グレッグ (2006). アービング・ゴフマン ([オンライン版] 版). ホボーケン: ラウトレッジ. pp. 33, 34. ISBN 978-0-203-00234-6. 6. トレヴィーノ, ジェームズ. 2003. 『ゴフマンの遺産』. ローマン・アンド・リトルフィールド出版社. p. 35. 7. リッツァー、ジョージ。2008年。『社会学理論』。マグロウヒル高等教育。p. 372。 8. ゴフマン、アービング(1956年)。『日常生活における自己の提示』。ダブルデイ。p. 13。ISBN 978-0-14-013571-8。 |

| The

Presentation of Self in Everyday Life at Open Library Works by Erving Goffman at Open Library |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Presentation_of_Self_in_Everyday_Life |

★

リンク

文献

その他の情報

■リンク

Do not paste, but [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!

Mascot character, Satoko-chan, born in 1982, by Sato Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Japan, Photo taken in the ishibashi Shopping Market street, Ikeda City, Osaka, Japan

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099