移民

Human migration

移民

Human migration

総説(→オリジナルサイト「移動と世界の「民」の現在」)

移民を人間の移動する現象であることのレ パートリーであると拡張して把握することを私は提案しよう。つまり、グローバル化のなか で、移動——移動(+)と表現——と対概念になった「移動しないこと」あるいは移動をオプションとして選択するが帰還し定着する場所に対する保守的な執着 を考えてみたいのである。この場合の後者を移動(−)と表現する。それに対して移民・移動の決断が自発性にもとづくが、強制力のように自発的でないかとい う観点は、19世紀末から20世紀に登場した亡命者や無国籍者の発生(H・アーレント)を考える上でも、先に指摘したように近代的なユダヤ人ディアスポラ という現象が、ユダヤ人のみならず、離合集散する民族集団の独調とその未来を考える上でも非常に重要になる。この移動ないしは移動に重きをおく意味の軸 と、移動の要因となる自発性の有無において、現在の世界の「民」の現在を考えてみたのが、下記の【図】である。

移動の有無と移動主体の自発的意思 の有無による世界の「民」の現在この図の4つの象限において、移動の強度 も自発性の強度も高いものが、労働移民である。他方、民族の離散(つまりシオニズムと論理的に対 偶の関 係にある)の典型がディアスポラである。シオニズムは国家(=主)なきユダヤの民が約束の地に終 結しユダヤ人国家を作ろうという政治運動であったが、大国 の中や亡命先で民族の自治をもとめる帰還定着と定住運動は、多かれ少なかれシオニズム的な性格をもつ。それとは、対照的に自発性がない定着化は収容所やア サイラム(難民キャンプ)への入所現象を意味している。これらの象限の間には、移動の強度も自発性/非自発性の強度も希薄な、移動にまつわる社会的カテゴ リーを発見することができる。それらは、それぞれ労働移民の周縁化としての「放浪者(バガブンド)」、ディアスポラの周縁化現象として「流浪難民」や「デ ラシネ」、シオニズムの周縁化つまり自発性をもち移動もおこなうが、最終的に自分の土地に戻るこ とで移動を楽しむ「観光客」が、アサイラム収容者の周辺化 現象とは、アサイラムやゲットーを出て、指定されたところに「定着する民」か紛争や虐殺などが沈静化された出身地への「帰還者」などがそれに相当する。

■ 旧:クレジット:移動の有無と移動主体の自 発的意思の有無による世界の「民」の現在

★ヒューマン・マイグレーション

☆人間の移動とは、人々が一箇所から別の 場所へ移動することである[1]。その目的は、新たな場所(地理的地域)に恒久的または一時的に定住することにある。この移動はしばしば長距離にわたり、 一国から別の国へ(国外移動)行われるが、国内移動(一国内での移動)が世界的に見て人間の移動の主要な形態である[2]: 21 移住は個人・世帯レベルでの人的資本の向上や、移住ネットワークへのアクセス改善と関連し、二次的な移動の可能性を促進する[3]。人間開発の向上に高い 潜在力を有し、貧困からの脱出において移住が最も直接的な手段であるとの研究結果もある。[4] 年齢も、労働目的・非労働目的を問わず移住において重要である。[5] 人々は個人、家族単位、あるいは大規模集団として移住する。[6] 移住には主に四つの形態がある:侵略、征服、植民地化、そして移出/移入である。[7] 自然災害や内乱などの強制的な避難により居住地を離れる人々は、避難民(国内避難民の場合は国内避難民)と呼ばれる。母国での政治的・宗教的迫害などから 他国へ逃れる人々は、受け入れ国に正式な保護を申請できる。こうした人々は一般的に亡命希望者と呼ばれる。申請が認められれば、法的地位は難民へと変更さ れる。[8]

2015年から2020年までの年間純移住率。出典:国連2019年

| Human migration is

the movement of people from one place to another,[1] with intentions of

settling, permanently or temporarily, at a new location (geographic

region). The movement often occurs over long distances and from one

country to another (external migration), but internal migration (within

a single country) is the dominant form of human migration

globally.[2]: 21 Migration is often associated with better human capital at both individual and household level, and with better access to migration networks, facilitating a possible second move.[3] It has a high potential to improve human development, and some studies confirm that migration is the most direct route out of poverty.[4] Age is also important for both work and non-work migration.[5] People may migrate as individuals, in family units or in large groups.[6] There are four major forms of migration: invasion, conquest, colonization and emigration/immigration.[7] People moving from their home due to forced displacement (such as a natural disaster or civil disturbance) may be described as displaced persons or, if remaining in the home country, internally-displaced persons. People who flee to a different country due to political, religious, or other types of persecution in their home country can formally request shelter in the host country. These people are commonly referred to as asylum seekers. If the application is approved, their legal classification changes to that of refugees.[8] |

人間の移動とは、人々が一箇所から別の場所へ移動することである

[1]。その目的は、新たな場所(地理的地域)に恒久的または一時的に定住することにある。この移動はしばしば長距離にわたり、一国から別の国へ(国外移

動)行われるが、国内移動(一国内での移動)が世界的に見て人間の移動の主要な形態である[2]: 21 移住は個人・世帯レベルでの人的資本の向上や、移住ネットワークへのアクセス改善と関連し、二次的な移動の可能性を促進する[3]。人間開発の向上に高い 潜在力を有し、貧困からの脱出において移住が最も直接的な手段であるとの研究結果もある。[4] 年齢も、労働目的・非労働目的を問わず移住において重要である。[5] 人々は個人、家族単位、あるいは大規模集団として移住する。[6] 移住には主に四つの形態がある:侵略、征服、植民地化、そして移出/移入である。[7] 自然災害や内乱などの強制的な避難により居住地を離れる人々は、避難民(国内避難民の場合は国内避難民)と呼ばれる。母国での政治的・宗教的迫害などから 他国へ逃れる人々は、受け入れ国に正式な保護を申請できる。こうした人々は一般的に亡命希望者と呼ばれる。申請が認められれば、法的地位は難民へと変更さ れる。[8] |

| Definition Depending on the goal and reason for relocation, migrants can be divided into three categories: migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. Each category is defined broadly as the combination of circumstances that motivate a person to change their location. As such, migrants are traditionally described as persons who change the country of residence for general reasons. These purposes may include better job opportunities or healthcare needs. This term is the most widely understood, as anyone changing their geographical location permanently is a migrant.[9] In contrast, refugees are defined by the UNHCR as "persons forced to flee their country because of violence or persecution".[10] The reasons for the refugees' migration usually involve war actions within the country or other forms of oppression, coming either from the government or non-governmental sources. Refugees are usually associated with people who must unwillingly relocate as fast as possible; hence, such migrants are likely to relocate undocumented.[9] Asylum seekers are associated with persons who also leave their country unwillingly, yet, who also do not do so under oppressing circumstances such as war or death threats. The motivation to leave the country for asylum seekers might involve an unstable economic or political situation or high rates of crime. Thus, asylum seekers relocate predominantly to escape the degradation of the quality of their lives.[9] Nomadic movements usually are not regarded as migrations, as the movement is generally seasonal, there is no intention to settle in the new place, and only a few people have retained this form of lifestyle in modern times. Temporary movement for travel, tourism, pilgrimages, or the commute is also not regarded as migration, in the absence of an intention to live and settle in the visited places.[9] |

定義 移住の目的や理由によって、移住者は三つのカテゴリーに分けられる。移住者、難民、そして亡命希望者だ。各カテゴリーは、人が居住地を変える動機となる状 況の組み合わせとして広く定義される。したがって、移住者は伝統的に、一般的な理由で居住国を変える人格として説明される。その目的には、より良い就職機 会や医療ニーズが含まれる。この用語は最も広く理解されている。なぜなら、地理的な位置を恒久的に変える者は誰でも移住者だからだ。[9] これに対し、難民はUNHCRによって「暴力や迫害により自国を離れることを余儀なくされた人格」と定義される。[10] 難民の移動理由は通常、国内での戦争行為や政府・非政府組織による抑圧が関与する。難民は通常、不本意ながら可能な限り迅速に移動せざるを得ない人々を指 すため、こうした移住者は無書類状態で移動する可能性が高い。[9] 亡命希望者は、自国を不本意に離れる人格だが、戦争や死の脅威といった抑圧的な状況下での移動ではない。亡命希望者が国外へ出る動機には、不安定な経済・政治状況や高い犯罪率が含まれる。したがって、亡命希望者の移動は主に生活の質の低下から逃れるためである。[9] 遊牧民の移動は通常、移住とは見なされない。移動が季節的なものであり、新たな土地に定住する意図がなく、現代においてこの生活様式を維持している者はご く少数だからだ。旅行、観光、巡礼、通勤のための一時的な移動も、訪問先に居住・定住する意図がない限り、移住とは見なされない。[9] |

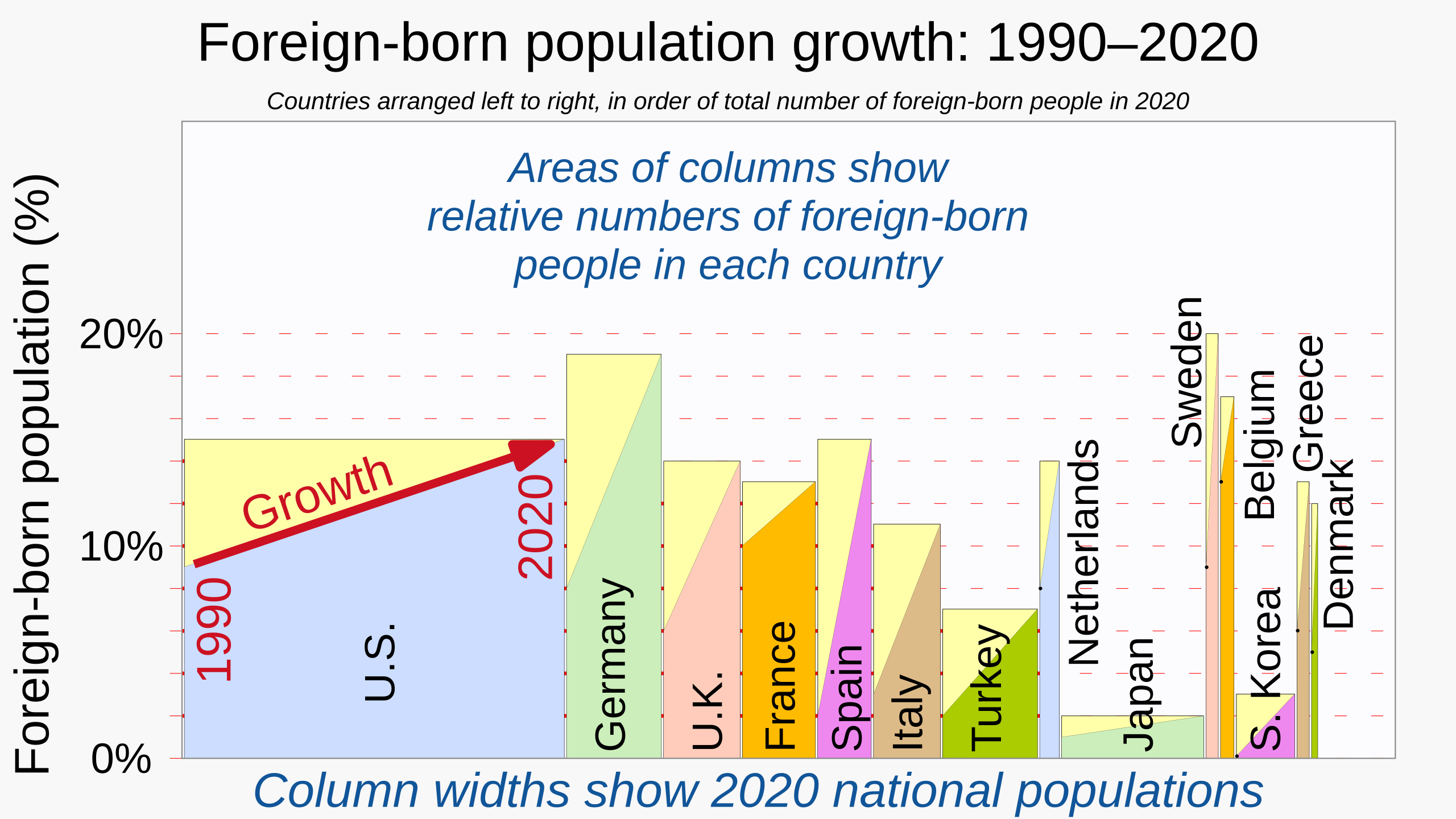

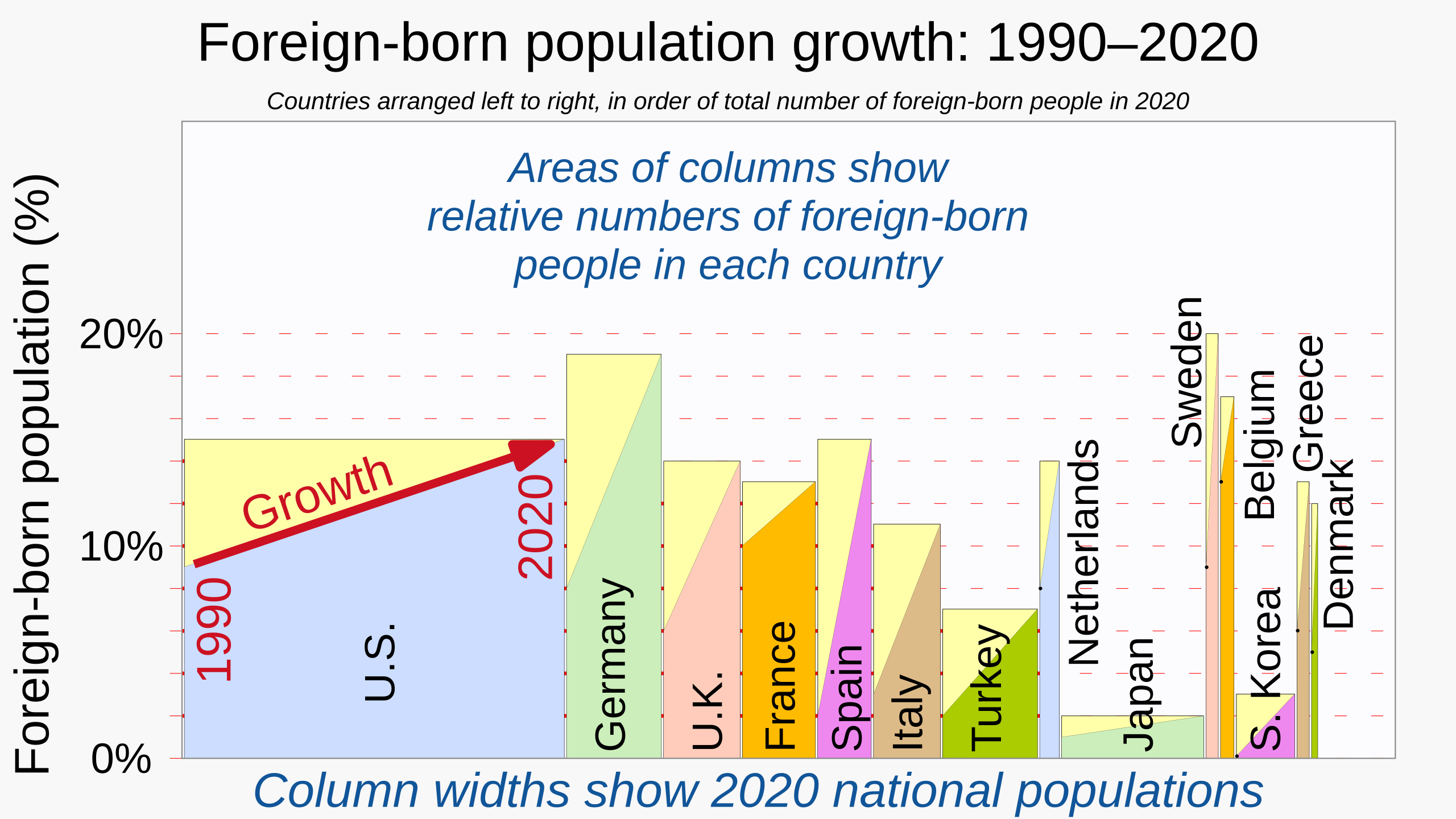

Migration patterns and related numbers In recent decades, migration to nearly every Western country has risen sharply.[11] The areas of the columns show the total foreign-born population, and the slopes show the rate of increase of foreigners living in the respective countries.  The number of migrants in the world, 1960–2015[12] There exist many statistical estimates of worldwide migration patterns. The World Bank has published three editions of its Migration and Remittances Factbook, beginning in 2008, with a second edition appearing in 2011 and a third in 2016.[13] The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) has published ten editions of the World Migration Report since 1999.[2][14] The United Nations Statistics Division also keeps a database on worldwide migration.[15] Recent advances in research on migration via the Internet promise better understanding of migration patterns and migration motives.[16][17] Structurally, there is substantial South–South and North–North migration; in 2013, 38% of all migrants had migrated from developing countries to other developing countries, while 23% had migrated from high-income OECD countries to other high-income countries.[18] The United Nations Population Fund says that "while the North has experienced a higher absolute increase in the migrant stock since 2000 (32 million) compared to the South (25 million), the South recorded a higher growth rate. Between 2000 and 2013, the average annual rate of change of the migrant population in developing regions (2.3%) slightly exceeded that of the developed regions (2.1%)."[19] Substantial internal migration can also take place within a country, either seasonal human migration (mainly related to agriculture and tourism to urban places), or shifts of the population into cities (urbanisation) or out of cities (suburbanisation). However, studies of worldwide migration patterns tend to limit their scope to international migration. |

移住パターンと関連数値 ここ数十年で、ほぼ全ての西側諸国への移住が急増している。[11] 棒グラフの面積は外国人出身者の総人口を示し、傾斜は各国における外国人居住者の増加率を示す。  世界の移住者数、1960年~2015年[12] 世界的な移住パターンに関する統計的推計は数多く存在する。世界銀行は2008年から『移住と送金ファクトブック』を3版発行しており、第2版は2011 年、第3版は2016年に発表された[13]。国際移住機関(IOM)は1999年以降『世界移住報告書』を10版発行している[2][14]。国連統計 局も世界的な移住に関するデータベースを管理している。[15] インターネットを介した移住研究の近年の進展は、移住パターンと移住動機への理解深化を約束している。[16][17] 構造的には、南から南への移住と北から北への移住が顕著である。2013年には、全移住者の38%が途上国から他の途上国へ移住し、23%が高所得 OECD諸国から他の高所得国へ移住していた。[18] 国連人口基金によれば、「2000年以降、北半球の移民ストックは南半球(2500万人)より高い絶対増加(3200万人)を示したが、南半球の成長率は より高かった。2000年から2013年の間、開発途上地域の移民人口の平均年間変化率(2.3%)は、先進地域の変化率(2.1%)をわずかに上回っ た。」[19] 国内でも大規模な移動が起きる。季節的な移動(主に農業や観光目的の都市部への移動)や、都市部への人口集中(都市化)、あるいは郊外への流出(郊外化)などだ。ただし、世界の移動パターンを研究する際に、国際移動に焦点を絞る傾向がある。 |

Almost half of these migrants are women, one of the most significant migrant-pattern changes in the last half-century.[19] Women migrate alone or with their family members and community. Even though female migration is largely viewed as an association rather than independent migration, emerging studies argue complex and manifold reasons for this.[22] As of 2019, the top ten immigration destinations were:[23] United States Germany Saudi Arabia Russian Federation United Kingdom United Arab Emirates France Canada Australia Italy In the same year, the top countries of origin were:[23] India Mexico China Russian Federation Syrian Arab Republic Bangladesh Pakistan Philippines Afghanistan Indonesia Besides these rankings, according to absolute numbers of migrants, the Migration and Remittances Factbook also gives statistics for top immigration destination countries and top emigration origin countries according to percentage of the population; the countries that appear at the top of those rankings are entirely different from the ones in the above rankings and tend to be much smaller countries.[24]: 2, 4  Typical grocery store on 8th Avenue in one of the Brooklyn Chinatowns on Long Island, New York. New York City's multiple Chinatowns in Queens, Manhattan, and Brooklyn are thriving as traditionally urban enclaves, as large-scale Chinese immigration continues into New York,[25][26][27][28] with the largest metropolitan Chinese population outside Asia,[29] The New York metropolitan area contains the largest ethnic Chinese population outside of Asia, comprising an estimated 893,697 uniracial individuals as of 2017.[30] As of 2013, the top 15 migration corridors (accounting for at least two million migrants each) were:[24]: 5 1. Mexico–United States 2. Russian Federation–Ukraine 3. Bangladesh–India 4. Ukraine–Russian Federation 5. Kazakhstan–Russian Federation 6. China–United States 7. Russian Federation–Kazakhstan 8. Afghanistan–Pakistan 9. Afghanistan–Iran 10. China–Hong Kong 11. India–United Arab Emirates 12. West Bank and Gaza–Jordan 13. India–United States 14. India–Saudi Arabia 15. Philippines–United States |

これらの移民のほぼ半数は女性であり、これは過去半世紀で最も顕著な移民パターンの変化の一つだ。[19] 女性は単独で、あるいは家族やコミュニティと共に移住する。女性の移住は主に独立した移住ではなく関連性として捉えられているが、新たな研究ではこの背景 に複雑で多様な理由があると主張している。[22] 2019年時点で、移民受け入れ上位10カ国は以下の通りだった: [23] アメリカ合衆国 ドイツ サウジアラビア ロシア連邦 イギリス アラブ首長国連邦 フランス カナダ オーストラリア イタリア 同年における主な移民送り出し国は以下の通りである:[23] インド メキシコ 中国 ロシア連邦 シリア・アラブ共和国 バングラデシュ パキスタン フィリピン アフガニスタン インドネシア これらの順位に加え、移民の絶対数に基づく統計として、『移民と送金ファクトブック』は人口比率に基づく主要移民受け入れ国・主要移民送り出し国の統計も 提供している。これらの順位で上位に現れる国々は、前述の順位とは全く異なり、規模がはるかに小さい国々である傾向がある。[24]: 2, 4  ニューヨーク州ロングアイランドにあるブルックリンのチャイナタウンの一つ、8番街の典型的な食料品店。 ニューヨーク市内のクイーンズ、マンハッタン、ブルックリンに点在する複数のチャイナタウンは、伝統的な都市部における中国人居住区として繁栄を続けてい る。大規模な中国人移民がニューヨークへ流入し続ける中[25][26][27][28]、アジア以外では最大規模の都市部中国人人口を抱えている。 [29] ニューヨーク都市圏はアジア以外で最大の華人人口を抱え、2017年時点で推定893,697人の単一民族個人が居住している。[30] 2013年時点で、上位15の移民回廊(各回廊で少なくとも200万人の移民を数える)は以下の通りであった。[24]: 5 1. メキシコ–アメリカ合衆国 2. ロシア連邦–ウクライナ 3. バングラデシュ–インド 4. ウクライナ–ロシア連邦 5. カザフスタン–ロシア連邦 6. 中国–アメリカ合衆国 7. ロシア連邦–カザフスタン 8. アフガニスタン–パキスタン 9. アフガニスタン–イラン 10. 中国–香港 11. インド–アラブ首長国連邦 12. 西岸地区・ガザ地区–ヨルダン 13. インド–アメリカ合衆国 14. インド–サウジアラビア 15. フィリピン–アメリカ合衆国 |

| Economic impacts World economy  Dorothea Lange, Drought refugees from Oklahoma camping by the roadside, Blythe, California, 1936 The impacts of human migration on the world economy have been largely positive. In 2015, migrants, who constituted 3.3% of the world population, contributed 9.4% of global GDP.[31][32] At a microeconomic level, the value of a human mobility is largely recognized by firms. A 2021 survey by the Boston Consulting Group found that 72% of 850+ executives across several countries and industries believed that migration benefited their countries, and 45% considered globally diverse employees a strategic advantage.[33] According to the Centre for Global Development, opening all borders could add $78 trillion to the world GDP.[34][35] |

経済的影響 世界経済  ドロシー・ラング撮影『オクラホマ州からの干ばつ難民、カリフォルニア州ブライスにて道路脇にキャンプする』1936年 人間の移動が世界経済に与える影響は、おおむね好ましいものである。2015年時点で、世界人口の3.3%を占める移民が、世界のGDPの9.4%を創出していた。[31][32] ミクロ経済レベルでは、人的移動の価値は企業によって広く認識されている。ボストン・コンサルティング・グループの2021年調査によると、複数国・業界 の850人以上の経営幹部の72%が移民は自国に利益をもたらすと考え、45%がグローバルに多様な従業員を戦略的優位性と見なしていた。[33] グローバル開発センターによれば、すべての国境を開放すれば世界のGDPは78兆ドル増加する可能性がある。[34][35] 。 |

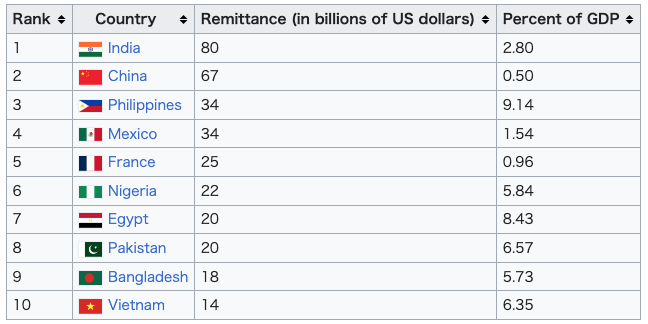

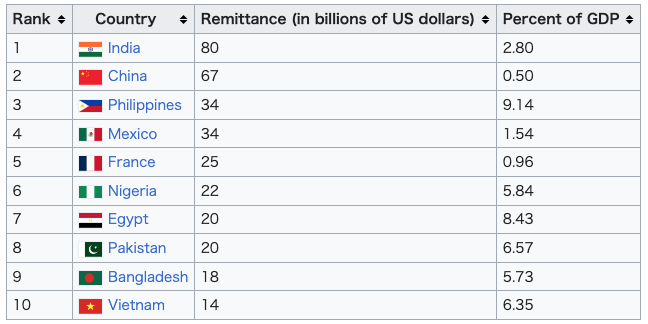

| Remittances Remittances (funds transferred by migrant workers to their home country) form a substantial part of the economy of some countries. The top ten remittance recipients in 2018.  In addition to economic impacts, migrants also make substantial contributions in sociocultural and civic-political life. Sociocultural contributions occur in the following areas of societies: food/cuisine, sport, music, art/culture, ideas and beliefs; civic-political contributions relate to participation in civic duties in the context of accepted authority of the State.[36] It is in recognition of the importance of these remittances that the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 10 targets to substantially reduce the transaction costs of migrants remittances to less than 3% by 2030.[37] |

送金 送金(移民労働者が母国に送金する資金)は、一部の国々の経済において重要な部分を占める。2018年の送金受入国トップ10は以下の通りである。  経済的影響に加え、移民は社会文化的・市民政治的生活においても多大な貢献をしている。社会文化的な貢献は、食文化・料理、スポーツ、音楽、芸術・文化、 思想・信念といった社会の分野で生じる。市民政治的な貢献は、国家の権威が認められる文脈における市民的義務への参加に関わる。[36] こうした送金の重要性を認識し、国連の持続可能な開発目標(SDGs)目標10は、2030年までに移民の送金取引コストを3%未満に大幅に削減すること を目指している。[37] |

| Voluntary and forced migration Migration is usually divided into voluntary migration and forced migration. The distinction between involuntary (fleeing political conflict or natural disaster) and voluntary migration (economic or labour migration) is difficult to make and partially subjective, as the motivators for migration are often correlated. The World Bank estimated that, as of 2010, 16.3 million or 7.6% of migrants qualified as refugees.[38] This number grew to 19.5 million by 2014 (comprising approximately 7.9% of the total number of migrants, based on the figure recorded in 2013).[39] At levels of roughly 3 percent the share of migrants among the world population has remained remarkably constant over the last 5 decades.[40] Voluntary migration See also: Free State Project Voluntary migration is based on the initiative and the free will of the person and is influenced by a combination of factors: economic, political and social: either in the migrants' country of origin (determinant factors or "push factors") or in the country of destination (attraction factors or "pull factors"). "Push-pull factors" are the reasons that push or attract people to a particular place. "Push" factors are the negative aspects(for example wars) of the country of origin, often decisive in people's choice to emigrate. The "pull" factors are the positive aspects of a different country that encourages people to emigrate to seek a better life. For example, the government of Armenia periodically gives incentives to people who will migrate to live in villages close to the border with Azerbaijan. This is an implementation of a push strategy, and the reason people do not want to live near the border is security concerns given tensions and hostility because of Azerbaijan.[41] Although the push-pull factors are opposed, both are sides of the same coin, being equally important. Although specific to forced migration, any other harmful factor can be considered a "push factor" or determinant/trigger factor, such examples being: poor quality of life, lack of jobs, excessive pollution, hunger, drought or natural disasters. Such conditions represent decisive reasons for voluntary migration, the population preferring to migrate in order to prevent financially unfavorable situations or even emotional and physical suffering.[42] Forced migration There are contested definitions of forced migration. However, the editors of a leading scientific journal on the subject, the Forced Migration Review, offer the following definition: Forced migration refers to the movements of refugees and internally displaced people (displaced by conflict) as well as people displaced by natural or environmental disasters, chemical or nuclear disasters, famine, or development projects.[43] These different causes of migration leave people with one choice, to move to a new environment. Immigrants leave their beloved homes to seek a life in camps, spontaneous settlement, and countries of asylum.[44] By the end of 2018, there were an estimated 67.2 million forced migrants globally – 25.9 million refugees displaced from their countries, and 41.3 million internally displaced persons that had been displaced within their countries for different reasons.[14] In 2022, 6 million Ukrainian people fled their country; meanwhile, 3 million Syrian people fled in 3 years. Rejected migrants Main article: Repatriation Where migrants' entry or continued residence within their intended host country is refused, they are liable to be returned or repatriated, usually against their will. |

自発的移住と強制移住 移住は通常、自発的移住と強制移住に分けられる。非自発的移住(政治的紛争や自然災害からの逃避)と自発的移住(経済的・労働目的の移住)の区別は困難 で、部分的に主観的である。移住の動機はしばしば相互に関連しているためだ。世界銀行の推計によれば、2010年時点で1630万人(移住者の7.6%) が難民に該当した。[38] この数は2014年までに1950万人(2013年記録に基づく移住者総数の約7.9%)に増加した。[39] 世界人口に占める移住者の割合は約3%で、過去50年間にわたり驚くほど一定を維持している。[40] 自発的移住 関連項目: フリーステート・プロジェクト 自発的移住は人格の意思と自由意志に基づくものであり、経済的・政治的・社会的要因の複合的な影響を受ける。これらの要因は移住者の出身国(決定的要因ま たは「プッシュ要因」)または移住先国(誘引要因または「プル要因」)のいずれかに存在する。「プッシュ・プル要因」とは、人々を特定の場所へ押し出す (または引き寄せる)理由を指す。「プッシュ」要因とは出身国の負の側面(例えば戦争)であり、移住の決定的要因となることが多い。「プル」要因とは異な る国の正の側面であり、より良い生活を求めて移住を促すものである。例えば、アルメニア政府は定期的に、アゼルバイジャン国境近くの村落に移住する人々に 対して奨励策を実施している。これはプッシュ戦略の実例であり、人々が国境付近に住みたがらない理由は、アゼルバイジャンとの緊張や敵意による安全保障上 の懸念である。[41] プッシュ・プル要因は対立するものの、両者は表裏一体であり、同等に重要である。強制移住に特有ではあるが、その他の有害な要因も「押し出し要因」または 決定要因/引き金要因と見なせる。例えば:生活の質の低下、雇用の不足、過剰な汚染、飢餓、干ばつ、自然災害などである。こうした状況は自発的移住の決定 的理由となり、人々は経済的不利な状況や精神的・肉体的苦悩を避けるために移住を選ぶ。[42] 強制移住 強制移住の定義には異論がある。しかし、この分野の主要学術誌『Forced Migration Review』の編集者らは次のように定義している:強制移住とは、難民や国内避難民(紛争による避難者)の移動、ならびに自然災害・環境災害、化学災 害・核災害、飢饉、開発事業による避難者の移動を指す。[43] こうした異なる移住要因は、人々に新たな環境へ移るという一つの選択肢しか残さない。移民たちは愛着のある故郷を離れ、キャンプや自発的定住地、庇護国で の生活を求め移動する。[44] 2018年末時点で、世界の強制移住者は推定6720万人であった。内訳は国外から避難した難民2590万人、国内で異なる理由により避難を余儀なくされ た国内避難民4130万人である。[14] 2022年には600万人のウクライナ人が国外へ逃れた。一方、シリアでは3年間で300万人が国外へ避難した。 拒否された移民 詳細記事: 送還 移民が希望する受け入れ国への入国または継続的な居住を拒否された場合、通常は本人の意思に反して、送還または本国送還の対象となる。 |

| Transit migration Transit migration is a highly debated term with no official definition. The common understanding is that it describes immigrants who are in the process of moving to an end goal country. The term was first coined by the UN in 1990 to describe immigrants who were traveling through countries surrounding Europe to end up in a European Union state.[45] Another example of transit migrants is Central Americans who travel through Mexico in order to live in the United States.[46] The term "transit migration" has generated a lot of debate among migration scholars and immigration institutions. Some criticize it as a Eurocentric term that was coined to place responsibility of migrants on states outside the European Union; and also to pressure those states to prevent migration onward to the European Union.[45] Scholars note that EU countries also have identical migrant flows and therefore it is not clear (illogical or biased) why it is only migrants in non-EU countries that are labeled as transit migrants.[47] It is also argued that the term "transit" glosses over the complexity and difficulty of migrant journeys: migrants face many types of violence while in transit; migrants often have no set end destination and must adjust their plan as they move (migrant journeys can take years and go through several stages). In November 2025, more than a dozen NGO rescue ships operating in the Mediterranean suspended all communication with the Libyan coast guard, citing an escalation in violent interceptions of asylum seekers at sea and their transfer to camps where torture, rape, and forced labor are rampant. The 13 search and rescue organizations described their decision as a rejection of the increasing pressure exerted by the EU.[48] |

通過移民 通過移民は公式な定義がなく、議論の多い用語である。一般的な理解では、最終目的国へ移動中の移民を指す。この用語は1990年に国連が、欧州周辺国を経 由して欧州連合加盟国を目指す移民を説明するために初めて用いた[45]。通過移民の別の例としては、米国で生活するためにメキシコを経由する中米出身者 が挙げられる[46]。 「通過移民」という用語は、移民学者や移民機関の間で多くの議論を引き起こしている。批判派は、この用語が欧州中心主義的であり、移民の責任をEU域外の 国々に転嫁し、さらにそれらの国々にEUへの移民流入を阻止するよう圧力をかけるために作られたと指摘する[45]。学者らは、EU諸国も同様の移民流動 を抱えているため、なぜ非EU諸国の移民だけが通過移民とレッテルを貼られるのか(非論理的あるいは偏った扱いである)不明確だと論じる。また「通過」と いう用語は、移民の旅路の複雑さと困難さを軽視していると指摘される。移民は移動中に様々な暴力に直面し、明確な最終目的地を持たず、移動中に計画を変更 せざるを得ない(移民の旅は数年を要し、複数の段階を経ることもある)。 2025年11月、地中海で活動する十数隻のNGO救助船が、海上での難民申請者に対する暴力的な阻止行為の激化と、拷問・強姦・強制労働が横行する収容 所への移送を理由に、リビア沿岸警備隊との全通信を停止した。13の捜索救助団体は、この決定をEUによる圧力増大への拒否と説明している。[48] |

| Contemporary labor migration theories Overview Numerous causes impel migrants to move to another country. For instance, globalization has increased the demand for workers in order to sustain national economies. Thus one category of economic migrants – generally from impoverished developing countries – migrates to obtain sufficient income for survival.[49][need quotation to verify][50] Such migrants often send some of their income homes to family members in the form of economic remittances, which have become an economic staple in a number of developing countries.[51] People may also move or are forced to move as a result of conflict, of human-rights violations, of violence, or to escape persecution. In 2014, the UN Refugee agency estimated that around 59.5 million people fell into this category.[49] Other reasons people may move include to gain access to opportunities and services or to escape extreme weather. This type of movement, usually from rural to urban areas, may be classed as internal migration.[49][need quotation to verify] Sociology-cultural and ego-historical factors also play a major role. In North Africa, for example, emigrating to Europe counts as a sign of social prestige. Moreover, many countries were former colonies. This means that many have relatives who live legally in the (former) colonial metro pole and who often provide important help for immigrants arriving in that metropole.[52] Relatives may help with job research and with accommodation.[53] The geographical proximity of Africa to Europe and the long historical ties between Northern and Southern Mediterranean countries also prompt many to migrate.[54] Whether a person decides to move to another country depends on the relative skill premier of the source and host countries. One is speaking of positive selection when the host country shows a higher skill premium than the source country. On the other hand, negative selection occurs when the source country displays a lower skill premium. The relative skill premia define migrants selectivity. Age heaping techniques display one method to measure the relative skill premium of a country.[55] A number of theories attempt to explain the international flow of capital and people from one country to another.[56] Research contributions Recent academic output on migration comprises mainly journal articles. The long-term trend shows a gradual increase in academic publishing on migration, which is likely to be related to the general expansion of academic literature production, and the increased prominence of migration research.[57] Migration and its research have further changed with the revolution in information and communication technologies.[58][59][60] Neoclassical economic theory Main article: Neoclassical economics This migration theory states that the main reason for labour migration is wage difference between two geographic locations. These wage differences are usually linked to geographic labour demand and supply. It can be said that areas with a shortage of labour but an excess of capital have a high relative wage while areas with a high labour supply and a dearth of capital have a low relative wage. Labour tends to flow from low-wage areas to high-wage areas. Often, with this flow of labour comes changes in the sending and the receiving country. Neoclassical economic theory best describes transnational migration because it is not confined by international immigration laws and similar governmental regulations.[56] Dual labor market theory Dual labour market theory states that pull factors in more developed countries mainly cause migration. This theory assumes that the labour markets in these developed countries consist of two segments: the primary market, which requires high-skilled labour, and the secondary market, which is very labour-intensive, requiring low-skilled workers. This theory assumes that migration from less developed countries into more developed countries results from a pull created by a need for labour in the developed countries in their secondary market. Migrant workers are needed to fill the lowest rung of the labour market because the native labourers do not want to do these jobs as they present a lack of mobility. This creates a need for migrant workers. Furthermore, the initial dearth in available labour pushes wages up, making migration even more enticing.[56] New economics of labor migration This theory states that migration flows and patterns cannot be explained solely at the level of individual workers and their economic incentives but that wider social entities must also be considered. One such social entity is the household. Migration can be viewed as a result of risk aversion from a household that has insufficient income. In this case, the household needs extra capital that can be achieved through remittances sent back by family members who participate in migrant labour abroad. These remittances can also have a broader effect on the economy of the sending country as a whole as they bring in capital.[56] Recent research has examined a decline in US interstate migration from 1991 to 2011, theorising that the reduced interstate migration is due to a decline in the geographic specificity of occupations and an increase in workers' ability to learn about other locations before moving there, through both information technology and inexpensive travel.[61] Other researchers find that the location-specific nature of housing is more important than moving costs in determining labour reallocation.[62] Relative deprivation theory Main article: Relative deprivation Relative deprivation theory states that awareness of the income difference between neighbours or other households in the migrant-sending community is essential in migration. The incentive to migrate is a lot higher in areas with a high level of economic inequality. In the short run, remittances may increase inequality, but in the long run, they may decrease it. There are two stages of migration for workers: first, they invest in human capital formation, and then they try to capitalise on their investments. In this way, successful migrants may use their new capital to provide better schooling for their children and better homes for their families. Successful high-skilled emigrants may serve as an example for neighbours and potential migrants who hope to achieve that level of success.[56] World systems theory World-systems theory looks at migration from a global perspective. It explains that interaction between different societies can be an important factor in social change. Trade with one country, which causes an economic decline in another, may create incentive to migrate to a country with a more vibrant economy. It can be argued that even after decolonisation, the economic dependence of former colonies remains on mother countries. However, this view of international trade is controversial, and some argue that free trade can reduce migration between developing and developed countries. It can be argued that the developed countries import labour-intensive goods, which causes an increase in the employment of unskilled workers in the less developed countries, decreasing the outflow of migrant workers. Exporting capital-intensive goods from rich countries to developing countries also equalises income and employment conditions, thus slowing migration. In either direction, this theory can be used to explain migration between countries that are geographically far apart.[56] Osmosis theory Based on the history of human migration[63] osmosis theory studies the evolution of its natural determinants. In this theory migration is divided into two main types: simple and complicated. The simple migration is divided, in its turn, into diffusion, stabilisation and concentration periods. During these periods, water availability, adequate climate, security and population density represent the natural determinants of human migration. The complicated migration is characterised by the speedy evolution and the emergence of new sub-determinants, notably earning, unemployment, networks, and migration policies. Osmosis theory[64] explains analogically human migration by the biophysical phenomenon of osmosis. In this respect, the countries are represented by animal cells, the borders by the semipermeable membranes and the humans by ions of water. According to the theory, according to the osmosis phenomenon, humans migrate from countries with less migration pressure to countries with high migration pressure. To measure the latter, the natural determinants of human migration replace the variables of the second principle of thermodynamics used to measure the osmotic pressure. |

現代の労働移民理論 概要 移民が他国へ移住する要因は多岐にわたる。例えば、グローバル化は国民経済を維持するために労働者需要を増加させた。したがって、経済移民の一種――主に 貧困な発展途上国出身者――は生存に必要な十分な収入を得るために移住する。[49][出典が必要][50] このような移民はしばしば、経済的送金という形で収入の一部を故郷の家族に送る。この送金は多くの発展途上国において経済の基盤となっている。[51] また、紛争や人権侵害、暴力の結果として、あるいは迫害から逃れるために、人々は移動したり強制的に移動させられたりする。2014年、国連難民高等弁務 官事務所(UNHCR)は約5950万人がこのカテゴリーに該当すると推定した。[49] その他の移動理由には、機会やサービスへのアクセス獲得、極端な気象条件からの逃避が含まれる。この種の移動(通常は農村部から都市部への移動)は国内移 住に分類される。[49][出典が必要] 社会文化的要因や自己歴史的要因も主要な役割を果たす。例えば北アフリカでは、ヨーロッパへの移住は社会的威信の象徴と見なされる。さらに多くの国が旧植 民地であったため、多くの移民が(旧)植民地宗主国に合法的に居住する親族を持ち、彼らが新移民に対して重要な支援を提供することが多い。[52] 親族は就職活動や住居確保の支援を行う。[53] アフリカとヨーロッパの地理的近接性、地中海北岸と南岸諸国間の長い歴史的結びつきも、多くの移民を促している。[54] 人格が他国への移住を決断するかは、出身国と受け入れ国の相対的な技能プレミアムに依存する。受け入れ国が出身国より高い技能プレミアムを示す場合、それ は正の選択である。一方、出身国が低い技能プレミアムを示す場合は負の選択となる。相対的な技能プレミアムが移民の選択性を決定する。年齢集積分析は、国 の相対的な技能プレミアムを測定する手法の一つである。[55] 資本や人材が国境を越えて移動する国際的な流れを説明しようとする理論は数多く存在する。[56] 研究の貢献 移民に関する最近の学術成果は、主に学術誌論文で構成されている。長期的な傾向として、移民に関する学術出版物は漸増しており、これは学術文献全体の生産 拡大と移民研究の重要性増大に関連していると考えられる。[57] 情報通信技術の革命により、移民とその研究はさらに変化した。[58][59][60] 新古典派経済理論 詳細記事: 新古典派経済学 この移民理論は、労働移民の主因は地理的場所間の賃金格差にあると述べる。こうした賃金格差は通常、地理的な労働需要と供給に関連している。労働力が不足 し資本が過剰な地域では相対賃金が高く、労働供給が豊富で資本が乏しい地域では相対賃金が低いと言える。労働力は低賃金地域から高賃金地域へ移動する傾向 がある。この労働移動に伴い、送り出し国と受け入れ国双方に変化が生じることが多い。新古典派経済理論は、国際移民法や政府規制に縛られないため、越境移 動を最も適切に説明する。[56] 二重労働市場理論 二重労働市場理論は、より発展した国における引き寄せ要因が主に移民を引き起こすと主張する。この理論は、これらの先進国の労働市場が二つのセグメントか ら成ると仮定する。一次市場は高度な技能を必要とし、二次市場は労働集約的で低技能労働者を必要とする。この理論は、発展途上国から先進国への移民が、先 進国の二次労働市場における労働力需要という引き寄せ要因から生じるとする。移民労働者は労働市場の最下層を埋めるために必要とされる。なぜなら、現地労 働者は移動性の欠如を伴うこれらの仕事を望まないからだ。これが移民労働者の需要を生み出す。さらに、当初の労働力不足が賃金を押し上げ、移民をさらに魅 力的にする。[56] 労働移民の新しい経済学 この理論は、移民の流れやパターンは個々の労働者とその経済的動機だけで説明できず、より広範な社会的実体も考慮すべきだと述べる。その一つが世帯であ る。移民は、収入が不十分な世帯のリスク回避の結果と見なせる。この場合、世帯は追加資本を必要とし、それは海外で移民労働に従事する家族が送金すること で得られる。こうした送金は資本を流入させるため、送り出し国全体の経済にも広範な影響を及ぼしうる。[56] 最近の研究では、1991年から2011年にかけての米国における州間移動の減少を検証し、移動減少の原因は職業の地理的固有性の低下と、情報技術と安価 な旅行手段の両方を通じて、移動前に他の地域について学ぶ労働者の能力向上にあると理論化している。[61] 他の研究者は、労働力の再配分を決める上で、移動コストよりも住宅の場所固有性が重要だと指摘している。[62] 相対的剥奪理論 詳細記事: 相対的剥奪 相対的剥奪理論は、移住者出身コミュニティにおける近隣世帯や他の世帯との所得格差の認識が、移住に不可欠だと述べる。経済的不平等が深刻な地域では移住 意欲が著しく高まる。短期的に送金は不平等を拡大させるが、長期的には縮小させる可能性がある。労働者の移住には二段階がある:まず人的資本形成に投資 し、次にその投資を回収しようとする。こうして成功した移住者は新たな資本を活用し、子女の教育環境や家族の居住環境を向上させ得る。成功した高技能移民 は、近隣住民や潜在的な移民にとって、その成功レベルを達成したいと願う手本となり得る。[56] 世界システム論 世界システム論は、移民をグローバルな視点から考察する。異なる社会間の相互作用が社会変革の重要な要因となり得ると説明する。ある国との貿易が別の国の 経済衰退を引き起こす場合、より活気ある経済を持つ国への移住動機が生まれる可能性がある。脱植民地化後も、旧植民地の母国への経済的依存は続くと主張で きる。しかし、この国際貿易観は議論の余地があり、自由貿易が発展途上国と先進国間の移民を減らすと主張する者もいる。先進国が労働集約型製品を輸入する ことで、発展途上国における非熟練労働者の雇用が増加し、移民労働者の流出が減ると主張できる。また、先進国から発展途上国への資本集約型製品の輸出は、 所得と雇用条件の均等化をもたらし、移住を鈍化させる。いずれの方向においても、この理論は地理的に遠く離れた国々間の移住を説明するのに用いられる。 [56] 浸透理論 人類の移住の歴史に基づき[63]、浸透理論はその自然決定要因の進化を研究する。この理論では移住は主に単純移住と複雑移住の二種類に分類される。単純 な移住はさらに拡散期、安定化期、集中期に区分される。これらの期間において、水資源の確保、適切な気候、安全保障、人口密度が人間の移住を決定する自然 要因となる。複雑な移住は急速な進化と新たな副次要因の出現を特徴とし、特に所得、失業、ネットワーク、移住政策が挙げられる。浸透理論[64]は、人間 の移住を生物物理学的現象である浸透に喩えて説明する。この理論では、国は動物細胞、国境は半透膜、人間は水イオンに例えられる。浸透現象に従い、人間は 移住圧力の低い国から高い国へ移動する。この移住圧力を測定するため、人間の移住における自然決定要因が、浸透圧を測る熱力学第二法則の変数に置き換えら れる。 |

| Social-scientific theories Sociology Main article: Sociology of immigration A number of social scientists have examined immigration from a sociological perspective, paying particular attention to how immigration affects and is affected by, matters of race and ethnicity, as well as social structure. They have produced three main sociological perspectives: symbolic interactionism, which aims to understand migration via face-to-face interactions on a micro-level social conflict theory, which examines migration through the prism of competition for power and resources structural functionalism (based on the ideas of Émile Durkheim), which examines the role of migration in fulfilling certain functions within each society, such as the decrease of despair and aimlessness and the consolidation of social networks In the 21st century, as attention has shifted away from countries of destination, sociologists have attempted to understand how transnationalism allows us to understand the interplay between migrants, their countries of destination, and their countries of origins.[65] In this framework, work on social remittances by Peggy Levitt and others has led to a stronger conceptualisation of how migrants affect socio-political processes in their countries of origin.[66] Much work also takes place in the field of integration of migrants into destination-societies.[67] Political science Political scientists have put forth a number of theoretical frameworks relating to migration, offering different perspectives on processes of security,[68][69] citizenship,[70] and international relations.[71] The political importance of diasporas has also become in the 21st century a growing field of interest, as scholars examine questions of diaspora activism,[72] state-diaspora relations,[73] out-of-country voting processes,[74] and states' soft power strategies.[75] In this field, the majority of work has focused on immigration politics, viewing migration from the perspective of the country of destination.[76] With regard to emigration processes, political scientists have expanded on Albert Hirschman's framework on '"voice" vs. "exit" to discuss how emigration affects the politics within countries of origin.[77][78] |

社会科学理論 社会学 主な記事: 移民社会学 多くの社会科学者が社会学的観点から移民を研究し、特に移民が人種や民族性、社会構造に与える影響、またそれらから受ける影響に注目してきた。彼らは主に三つの社会学的視点を生み出した: 象徴的相互作用論:ミクロレベルでの対面的相互作用を通じて移民を理解しようとする 社会葛藤論:権力と資源をめぐる競争というレンズを通して移民を考察する 構造機能主義(エミール・デュルケームの思想に基づく):絶望や目的喪失の減少、社会ネットワークの強化など、各社会内で特定の機能を充足する移民の役割を考察する 21世紀に入り、注目が移住先国から離れるにつれ、社会学者たちはトランスナショナル主義が移住者・移住先国・出身国の相互作用をどう理解させるかを解明 しようとしている[65]。この枠組みにおいて、ペギー・レヴィットらによる社会的送金研究は、移住者が出身国の社会政治的プロセスに与える影響の概念化 を深化させた。[66] 移民の目的地社会への統合に関する研究も数多く行われている。[67] 政治学 政治学者たちは移民に関連する数多くの理論的枠組みを提唱し、安全保障[68][69]、市民権[70]、国際関係といったプロセスに対する異なる視点を 提供している。[71] 21世紀に入り、ディアスポラの政治的重要性も関心の高まる分野となった。研究者らはディアスポラ活動[72]、国家とディアスポラの関係[73]、国外 投票プロセス[74]、国家のソフトパワー戦略といった問題を検証している。この分野では、研究の大半が移民政策に焦点を当て、移住を目的地国の視点から 捉えている[76]。一方、出国プロセスに関しては、政治学者たちがアルバート・ハーシュマンの「発言(voice)」対「退出(exit)」の枠組みを 発展させ、出国が母国内の政治にどう影響するかを論じている[77][78]。 |

| Historical theories Ravenstein icon This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Certain laws of social science have been proposed to describe human migration. The following was a standard list after Ernst Georg Ravenstein's proposal in the 1880s: 1. every migration flow generates a return or counter migration. 2. the majority of migrants move a short distance. 3. migrants who move longer distances tend to choose big-city destinations. 4. urban residents are often less migratory than inhabitants of rural areas. 5. families are less likely to make international moves than young adults. 6. most migrants are adults. 7. large towns grow by migration rather than natural increase. 8. migration stage by stage (step migration). 9. urban, rural difference. 10. migration and technology. 11. economic condition. Push and pull Demographer Everett S. Lee's model divides factors causing migrations into two groups of factors: push and pull. Push factors are things that are unfavourable about the home area that one lives in, and pull factors are things that attract one to another host area.[79][80] Push factors: Not enough jobs Few opportunities Conscription (draft young men into army) Famine or drought Political fear of persecution Poor medical care Loss of wealth Natural disasters Death threats Desire for more political or religious freedom Pollution Poor housing Discrimination Poor chances of marrying War or threat of invasion Disease Pull factors: Job opportunities Better living conditions The feeling of having more political or religious freedom Enjoyment Education Better medical care Attractive climates Security Family links Industry Better chances of marrying Climate cycles The modern field of climate history suggests that the successive waves of Eurasian nomadic movement throughout history have had their origins in climatic cycles, which have expanded or contracted pastureland in Central Asia, especially Mongolia and to its west the Altai Mountains. People were displaced from their home ground by other tribes trying to find land that essential flocks could graze, each group pushing the next further to the south and west, into the highlands of Anatolia, the Pannonian Plain, into Mesopotamia, or southwards, into the rich pastures of China. Bogumil Terminski uses the term "migratory domino effect" to describe this process in the context of Sea People invasion.[81] Food, sex, and security The theory is that migration occurs because individuals search for food, sex and security outside their usual habitation; Idyorough (2008) believes that towns and cities are a creation of the human struggle to obtain food, sex and security. To produce food, security and reproduction, human beings must, out of necessity, move out of their usual habitation and enter into indispensable social relationships that are cooperative or antagonistic. Human beings also develop the tools and equipment to interact with nature to produce the desired food and security. The improved relationship (cooperative relationships) among human beings and improved technology further conditioned by the push and pull factors all interact together to cause or bring about migration and higher concentration of individuals into towns and cities. The higher the technology of production of food and security and the higher the cooperative relationship among human beings in the production of food and security and the reproduction of the human species, the higher would be the push and pull factors in the migration and concentration of human beings in towns and cities. Countryside, towns and cities do not just exist, but they do so to meet the basic human needs of food, security and the reproduction of the human species. Therefore, migration occurs because individuals search for food, sex and security outside their usual habitation. Social services in the towns and cities are provided to meet these basic needs for human survival and pleasure.[82] Other models Zipf's inverse distance law (1956) Gravity model of migration and the friction of distance Radiation law for human mobility Buffer theory Stouffer's theory of intervening opportunities (1940) Zelinsky's Mobility Transition Model (1971) Bauder's regulation of labour markets (2006): "suggests that the international migration of workers is necessary for the survival of industrialised economies...[It] turns the conventional view of international migration on its head: it investigates how migration regulates labour markets, rather than labour markets shaping migration flows."[83] |

歴史的理論 ラヴェンシュタイン アイコン この節は出典を一切示していない。信頼できる出典を引用してこの節を改善してほしい。出典のない記述は異議を唱えられ、削除される可能性がある。(2020年5月)(このメッセージを削除する方法と時期について学ぶ) 人間の移住を説明する社会科学の法則がいくつか提唱されている。以下は1880年代にエルンスト・ゲオルク・ラヴェンシュタインが提案した標準的なリストである: 1. あらゆる移住の流れは帰還または逆移住を生む。 2. 移住者の大半は短距離を移動する。 3. 長距離を移動する移住者は大都市を目的地とする傾向がある。 4. 都市住民は農村住民より移動率が低いことが多い。 5. 家族単位の国際移動は若年成人より発生率が低い。 6. 移住者の大半は成人である。 7. 大都市は自然増加より移住によって成長する。 8. 段階的移住(ステップ移住)。 9. 都市と農村の差異。 10. 移住と技術。 11. 経済状況。 押しと引き 人口統計学者エヴェレット・S・リーのモデルは、移住を引き起こす要因を二つのグループに分類する:押し要因と引き要因である。押し要因とは、居住する出身地域における不利な要素であり、引き要因とは、別の受け入れ地域へ人を惹きつける要素である。[79][80] プッシュ要因: 仕事不足 機会の少なさ 徴兵(若年男性の軍隊への徴用) 飢饉や干ばつ 迫害への政治的恐怖 医療の貧弱さ 財産の喪失 自然災害 死の脅威 より多くの政治的・宗教的自由への渇望 汚染 劣悪な住居 差別 結婚機会の乏しさ 戦争や侵略の脅威 疾病 プル要因: 雇用機会 より良い生活環境 政治的・宗教的自由の拡大感 娯楽 教育 医療水準の向上 魅力的な気候 安全保障 家族関係 産業 結婚機会の増加 気候変動 現代の気候史研究によれば、ユーラシアにおける遊牧民の移動は、気候変動によって中央アジア(特にモンゴル及び西方のアルタイ山脈)の牧草地が拡大・縮小 したことに起因する。人々は、家畜の放牧地を求めて移動する他の部族によって故郷から追いやられ、各集団が次々に南や西へと押し出され、アナトリア高原、 パノニア平原、メソポタミア、あるいは南方の中国の豊かな牧草地へと向かった。ボグミル・テルミンスキは、この過程を「移動のドミノ効果」と呼び、海の民 の侵入の文脈で説明している[81]。 食糧、性、安全 移住は、個人が通常の居住地外で食糧、性、安全を求めるために発生するという理論がある。アイディルー(2008)は、町や都市は食糧、性、安全を得るた めの人間の闘争が生み出したものだと考えている。食糧生産、安全確保、繁殖のためには、人間は必要に迫られて通常の居住地を離れ、協力的あるいは敵対的な 不可欠な社会的関係に入らねばならない。人間はまた、望ましい食糧と安全を生み出すために自然と関わる道具や設備を発達させる。人間同士の改善された関係 (協力関係)と技術進歩は、さらに押し引き要因によって条件付けられ、相互に作用して移住を引き起こし、個体を町や都市へより集中させる。食糧と安全の生 産技術が高度化し、食糧・安全の生産および人類の繁殖における協力関係が強化されるほど、都市部への移住と人口集中を促す押し引き要因は強まる。農村・ 町・都市は単なる存在ではなく、食糧・安全・人類繁殖という人間の基本的欲求を満たすために存在する。したがって、移住は個人が通常の居住地外で食糧、 性、安全を求めるために発生する。都市部の社会サービスは、人間の生存と快楽のためのこれらの基本的欲求を満たすために提供される。[82] その他のモデル ジップの逆距離法則(1956年) 移住の重力モデルと距離摩擦 人間の移動に関する放射状法則 緩衝地帯理論 ストウファーの中間機会理論 (1940) ゼリンスキーの移動性遷移モデル (1971) バウダーの労働市場調整理論 (2006): 「労働者の国際移住は工業化経済の存続に不可欠だと示唆している...[これは] 従来の国際移住観を覆す:移住が労働市場を形作るのではなく、移住が労働市場を調整する仕組みを検証するのだ。」[83] |

| Migration governance By their very nature, international migration and displacement are transnational issues concerning the origin and destination States and States through which migrants may travel (often referred to as "transit" States) or in which they are hosted following displacement across national borders. And yet, somewhat paradoxically, the majority of migration governance has historically remained with individual states. Their policies and regulations on migration are typically made at the national level.[84] For the most part, migration governance has been closely associated with State sovereignty. States retain the power of deciding on the entry and stay of non-nationals because migration directly affects some of the defining elements of a State.[85] Comparative surveys reveal varying degrees of openness to migrants across countries, considering policies such as visa availability, employment prerequisites, and paths to residency.[86] Bilateral and multilateral arrangements are features of migration governance at an international level. There are several global arrangements in the form of international treaties in which States have reached an agreement on the application of human rights and the related responsibilities of States in specific areas. The 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Refugee Convention) are two significant examples notable for being widely ratified. Other migration conventions have not been so broadly accepted, such as the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, which still has no traditional countries of destination among its States parties. Beyond this, there have been numerous multilateral and global initiatives, dialogues and processes on migration over several decades. The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (Global Compact for Migration) is another milestone, as the first internationally negotiated statement of objectives for migration governance striking a balance between migrants' rights and the principle of States' sovereignty over their territory. Although it is not legally binding, the Global Compact for Migration was adopted by consensus in December 2018 at a United Nations conference in which more than 150 United Nations Member States participated and, later that same month, in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), by a vote among the Member States of 152 to 5 (with 12 abstentions).[87] Migration programs Colonialism and colonization opens up distant territories and their people to migration, having dominated what is identified as modern migration. Colonialism globalized systems of migration and established ties effective until today.[88] While classic modern colonialism relied on the subjugation and rule of local indigenous peoples by small groups of conquering metropolitan people, soon forced migration, through slavery or indentured servitude supplanted the subjugated local indigenous peoples. Settler colonialism later continued or established the rule of the colonizers through migration, particularly settlement. Settler colonies relied on the attraction of metropolitan migrants with the promise of settlement and increasingly outnumbering, displacing or killing indigenous peoples. Only in the late stage of colonialism migration flows oriented towards the metropole instead of out or outside of it. After decolonization migration ties between former colonies to former metropoles have been continuing. Today's independent countries have developed selective or targeted foreign worker policies or programs, with the aim of boosting economies with skilled or relatively cheap new local labour, while discrimination and exploitation are often fed by ethnic nationalist opposition to such policies.[89] |

移民統治 国際的な移民と避難民問題は、その性質上、出発国と目的地国、そして移民が通過する国(しばしば「通過国」と呼ばれる)や国境を越えた避難後に受け入れら れる国に関わる越境的な課題である。しかし、やや逆説的に、移民統治の大部分は歴史的に個々の国家に委ねられてきた。移民に関する政策や規制は通常、国民 レベルで策定される。[84] 概して、移住ガバナンスは国家主権と密接に関連してきた。移住は国家を定義する要素のいくつかに直接影響するため、国家は非国民の入国と滞在を決定する権 限を保持している。[85] 比較調査によれば、ビザの取得可能性、就労の前提条件、居住権取得の経路といった政策を考慮すると、国によって移住者に対する開放度の程度は様々である。 [86] 二国間及び多国間の取り決めは、国際レベルにおける移民ガバナンスの特徴である。国際条約という形で、特定分野における人権の適用と国家の関連責任につい て合意に達した複数の世界的取り決めが存在する。1966年の「市民的及び政治的権利に関する国際規約」と1951年の「難民の地位に関する条約」(難民 条約)は、広く批准されている点で注目すべき二つの重要な例である。その他の移民条約はこれほど広く受け入れられていない。例えば「すべての移民労働者及 びその家族の権利の保護に関する国際条約」は、締約国の中に伝統的な移民受け入れ国が未だ存在しない。これに加え、数十年にわたり移民問題に関する数多く の多国間・国際的な取り組み、対話、プロセスが展開されてきた。安全で秩序ある正規の移住に関するグローバル・コンパクト(移住に関するグローバル・コン パクト)は、移住者の権利と国家の領土主権の原則とのバランスを取る移住ガバナンスの目標を国際的に交渉して定めた初の文書として、もう一つの画期的な成 果である。法的拘束力はないものの、このグローバル・コンパクトは2018年12月、150以上の国連加盟国が参加した国連会議で合意により採択され、同 月下旬には国連総会(UNGA)において加盟国による投票(賛成152、反対5、棄権12)を経て承認された。[87] 移住プログラム 植民地主義と植民地化は、遠隔地の領土とその住民を移住に開放し、現代移住と認識されるものを支配してきた。植民地主義は移住システムをグローバル化し、今日まで有効な結びつきを確立した。[88] 古典的近代植民地主義は、少数の征服母国人による現地先住民の服従と支配に依存していたが、やがて奴隷制や契約労働制による強制移住が、服従させられた現 地先住民に取って代わった。その後、入植者植民地主義は移住、特に入植を通じて植民者の支配を継続または確立した。入植者植民地は、入植の約束で母国から の移住者を惹きつけ、次第に先住民を数で上回り、追いやったり殺害したりした。 植民地主義の後期段階になって初めて、移住の流れは植民地母国からではなく、母国へ向かうものとなった。脱植民地化後も、旧植民地と旧母国との間の移住関 係は継続している。今日の独立国は、熟練した、あるいは比較的安価な新たな現地労働力で経済を活性化させる目的で、選択的あるいは対象を絞った外国人労働 者政策やプログラムを開発してきた。一方で、こうした政策に対する民族主義的なナショナリストの反対運動によって、差別や搾取が助長されることも多い。 [89] |

| Demographics of the world Early human migrations El Inmigrante – 2005 film Environmental migrant Existential migration Expatriate Feminisation of migration Genographic Project Humanitarian crisis International migration Illegal immigration Linguistic Diversity in Space and Time Immigration to Europe List of diasporas Jewish diaspora Migrant literature Migration in China Most recent common ancestor Offshoring Political demography Queer migration Refugee roulette Religion and human migration Replacement migration Return migration Separation barrier Snowbird (person) Space colonization Timeline of maritime migration and exploration Cultural bereavement |

世界の人口統計 初期の人類移動 エル・インミグランテ – 2005年映画 環境難民 実存的移動 在外邦人 移民の女性化 ジェノグラフィック・プロジェクト 人道危機 国際移住 不法移民 時空間における言語多様性 欧州への移民 ディアスポラ一覧 ユダヤ人ディアスポラ 移民文学 中国における移住 最終共通祖先 オフショアリング 政治人口学 クィア移民 難民ルーレット 宗教と人類移動 代替移民 帰還移民 分離壁 スノーバード(人格) 宇宙植民 海上移動と探検の年表 文化的喪失 |

| References | |

| Sources and further reading Anderson, Vivienne. and Johnson, Henry. (eds) Migration, Education and Translation: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Human Mobility and Cultural Encounters in Education Settings. New York: Routledge, 2020. Behdad, Ali. A Forgetful Nation: On Immigration and Cultural Density in the United States, Duke UP, 2005. Brettell, Caroline B.; Hollifield, James F. Migration Theory(Routledge, 2000) [Migration Theory online] Chaichian, Mohammad. Empires and Walls: Globalisation, Migration, and Colonial Control, Leiden: Brill, 2014. Jared Diamond, Guns, germs and steel. A short history of everybody for the last 13'000 years, 1997. De La Torre, Miguel A., Trails of Terror: Testimonies on the Current Immigration Debate, Orbis Books, 2009. Fell, Peter and Hayes, Debra. What are they doing here? A critical guide to asylum and immigration, Birmingham (UK): Venture Press, 2007. [ISBN missing] Hanlon, Bernadette and Vicino, Thomas J. Global Migration: The Basics, New York and London: Routledge, 2014. de Haas, Hein. How Migration Really Works, Penguin, 2023. Harzig, Christiane, and Dirk Hoerder. What is migration history? (John Wiley & Sons, 2013) online. Hoerder, Dirk. Cultures in Contact. World Migrations in the Second Millennium, Duke University Press, 2002. [ISBN missing] Idyorough, Alamveabee E. "Sociological Analysis of Social Change in Contemporary Africa", Makurdi: Aboki Publishers, 2015.[ISBN missing] IOM World Migration Report, see World Migration Report International Organization for Migration Kleiner-Liebau, Désirée. Migration and the Construction of National Identity in Spain, Madrid / Frankfurt, Iberoamericana / Vervuert, Ediciones de Iberoamericana, 2009. ISBN 978-8484894766. Knörr, Jacqueline. Women and Migration. Anthropological Perspectives, Frankfurt & New York: Campus Verlag & St. Martin's Press, 2000. [ISBN missing] Knörr, Jacqueline. Childhood and Migration. From Experience to Agency, Bielefeld: Transcript, 2005.[ISBN missing] Manning, Patrick. Migration in World History, New York and London: Routledge, 2005. [ISBN missing] Miller, Mark & Castles, Stephen (1993). The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. Guilford Press. [ISBN missing] Migration for Employment, Paris: OECD Publications, 2004. [ISBN missing] OECD International Migration Outlook 2007, Paris: OECD Publications, 2007.[ISBN missing] Pécoud, Antoine and Paul de Guchteneire (Eds): Migration without Borders, Essays on the Free Movements of People (Berghahn Books, 2007). [ISBN missing] Purohit, A. K. (ed.) The Philosophy of Evolution, Yash Publishing House, Bikaner, 2010. ISBN 8186882359. Rubel, Alexander (2024a). Migration in der Antike. Von der Odyssee bis Mohammed [Migration in Antiquity. From the Odyssey to Muhammad]. Freiburg: wbg Academic, ISBN 978-3-534-61013-6. Rubel, Alexander (2024b). Migration. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit [Migration. A cultural history of mankind]. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, ISBN 978-3-17-044528-4. Abdelmalek Sayad. The Suffering of the Immigrant, Preface by Pierre Bourdieu, Polity Press, 2004. [ISBN missing] Reich, David (2018). Who We Are And How We Got Here – Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-1-101-87032-7. Diamond, Jared (20 April 2018). "A Brand-New Version of Our Origin Story". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2018. Stalker, Peter. No-Nonsense Guide to International Migration, New Internationalist, 2nd ed., 2008. [ISBN missing] White, Micheal (Ed.) (2016). International Handbook of Migration and Population Distribution. Springer. [ISBN missing] Journals International Migration Review Migration Letters International Migration ISSN 1468-2435 Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies Review of Economics of the Household |

出典および追加文献(さらに読む) アンダーソン、ヴィヴィアン、ジョンソン、ヘンリー(編)『移住、教育、翻訳:教育現場における人間の移動と文化の出会いに関する学際的視点』ニューヨーク:ラウトリッジ、2020年。 ベフダッド、アリ『忘却の国家:米国における移民と文化的密度について』デューク大学出版、2005年。 ブレッテル、キャロライン B.、ホリフィールド、ジェームズ F. 『移民理論』(ラウトレッジ、2000年) [移民理論オンライン版] チャイチャン、モハンマド。『帝国と壁:グローバル化、移民、植民地支配』 ライデン:ブリル、2014年。 ジャレド・ダイアモンド、『銃、病原菌、鉄』 『人類の1万3000年史』1997年。 デ・ラ・トーレ、ミゲル・A.『恐怖の軌跡:現代移民論争に関する証言』オービスブックス、2009年。 フェル、ピーターとヘイズ、デブラ『彼らはなぜここにいるのか? 亡命と移民の批判的ガイド』バーミンガム(英国):ベンチャープレス、2007年。[ISBN欠落] ハンロン、バーナデットとヴィチーノ、トーマス・J. 『グローバル移住:基礎知識』ニューヨークとロンドン:ラウトレッジ、2014年。 デ・ハース、ハイン。『移住の真実の仕組み』ペンギン、2023年。 ハルツィヒ、クリスティアーネとディルク・ホーデル。『移住史とは何か?』(ジョン・ワイリー・アンド・サンズ、2013年)オンライン版。 ホーダー、ディルク。『接触する文化。第二千年紀の世界移住』デューク大学出版、2002年。[ISBN未記載] イディオロー、アラムベアビー・E。「現代アフリカにおける社会変容の社会学的分析」、マクルディ:アボキ出版、2015年。[ISBN未記載] IOM 世界移民報告書、世界移民報告書 国際移住機関を参照 クライナー=リーバウ、デジレ。スペインにおける移民と国民的アイデンティティの構築、マドリード/フランクフルト、イベロアメリカーナ/ヴェルフェルト、エディシオネス・デ・イベロアメリカーナ、2009年。ISBN 978-8484894766。 クノール、ジャクリーン。女性と移民。人類学的視点、フランクフルト&ニューヨーク:キャンパス出版社&セント・マーティンズ・プレス、2000年。[ISBN なし] クノール、ジャクリーン。子供時代と移住。経験から主体性へ、ビーレフェルト:トランスクリプト、2005年。[ISBN なし] マニング、パトリック。世界史における移住、ニューヨーク&ロンドン:ラウトレッジ、2005年。[ISBN なし] ミラー、マーク、キャッスルズ、スティーブン(1993)。『移住の時代:現代世界における国際的な人口移動』。ギルフォード・プレス。[ISBN なし] 雇用のための移住、パリ:OECD 出版、2004 年。[ISBN なし] OECD 国際移住展望 2007、パリ:OECD 出版、2007 年。[ISBN なし] ペクー、アントワーヌ、ポール・ド・ギュシュテネール(編):『国境なき移住、人の自由な移動に関するエッセイ』(ベルハーン・ブックス、2007年)。[ISBN なし] プロヒット、A. K. (編) 『進化の哲学』、ヤッシュ出版社、ビカネール、2010年。ISBN 8186882359。 ルーベル、アレクサンダー(2024a)。『古代における移住。オデュッセイアからモハメッドまで』フライブルク:wbg Academic、ISBN 978-3-534-61013-6。 ルーベル、アレクサンダー(2024b)。『移住。人類の文化史』シュトゥットガルト:コールハンマー、ISBN 978-3-17-044528-4。 アブデルマレク・サヤド。移民の苦悩、ピエール・ブルデューによる序文、Polity Press、2004年。[ISBN 欠落] ライク、デイヴィッド (2018)。我々は誰であり、どのようにしてここにたどり着いたのか - 古代 DNA と人類の過去に関する新しい科学。パンテオン・ブックス。ISBN 978-1-101-87032-7。 ダイヤモンド、ジャレッド(2018年4月20日)。「人類起源説の全く新しいバージョン」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ。2018年4月23日閲覧。 ストーカー、ピーター。『国際移住の実情ガイド』、ニュー・インターナショナル、第2版、2008年。[ISBN未記載] ホワイト、マイケル(編)(2016年)。『国際移住と人口分布ハンドブック』。スプリンガー。[ISBN欠落] 学術誌 国際移住レビュー 移住レターズ 国際移住 ISSN 1468-2435 民族・移住研究ジャーナル 家計経済学レビュー |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_migration |

関連リンク

出典

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

コンフリクトと移民:新しい研究の射程

Social Conflicts of Human Migration Processes: A New Perspective

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099