希望

Hope

☆希望(Hope)とは、自身の人生や世界全体における出来事や状況について、好ましい結果を期待する楽観的な心の状態である[1]。動詞としての「希望する」は、メリアム・ウェブスター辞典において「確信を持って期待する」または「期待を込めて願いを抱く」と定義される[2]。

その対義語には、落胆、絶望感、そして絶望が含まれる。[3]

希望は、実践的推論、宗教的徳としての希望、法理論、文学といった人間の生活の様々な側面を通じて表現される。同時に文化的・神話的側面も持つ。

| Hope is an

optimistic state of mind that is based on an expectation of positive

outcomes with respect to events and circumstances in one's own life, or

the world at large.[1] As a verb, Merriam-Webster defines hope as "to

expect with confidence" or "to cherish a desire with anticipation".[2] Among its opposites are dejection, hopelessness, and despair.[3] Hope finds expression through many dimensions of human life, including practical reasoning, the religious virtue of hope, legal doctrine, and literature, alongside cultural and mythological aspects. |

希望とは、自身の人生や世界全体における出来事や状況について、好まし

い結果を期待する楽観的な心の状態である[1]。動詞としての「希望する」は、メリアム・ウェブスター辞典において「確信を持って期待する」または「期待

を込めて願いを抱く」と定義される[2]。 その対義語には、落胆、絶望感、そして絶望が含まれる。[3] 希望は、実践的推論、宗教的徳としての希望、法理論、文学といった人間の生活の様々な側面を通じて表現される。同時に文化的・神話的側面も持つ。 |

In psychology Hope, which lay at the bottom of the box, remained. Allegorical painting by George Frederic Watts, 1886 American professor of psychology Barbara Fredrickson argues that hope comes into its own when crisis looms, opening us to new creative possibilities.[4] Frederickson argues that with great need comes an unusually wide range of ideas, as well as such positive emotions as happiness and joy, courage, and empowerment, drawn from four different areas of one's self: from a cognitive, psychological, social, or physical perspective.[5] Such positive thinking bears fruit when based on a realistic sense of optimism, not on a naive "false hope".[6][7] The psychologist Charles R. Snyder linked hope to the existence of a goal, combined with a determined plan for reaching that goal.[8] Alfred Adler had similarly argued for the centrality of goal-seeking in human psychology,[9] as too had philosophical anthropologists like Ernst Bloch.[10] Snyder also stressed the link between hope and mental willpower (hardiness),[11] as well as the need for realistic perception of goals (problem orientation),[12] arguing that the difference between hope and optimism was that the former can look like wishful thinking but the latter provides the energy to find practical pathways for an improved future.[13] D. W. Winnicott saw a child's antisocial behavior as expressing as a cry for help, an unconscious hope, meaning an unspoken desire for a positive outcome for those who are in control in the wider society, when containment within the immediate family had failed.[14] Object relations theory similarly sees the analytic transference as motivated in part by an unconscious hope that past conflicts and traumas can be dealt with anew.[15] |

心理学において 箱の底に残っていた希望は消えなかった。ジョージ・フレデリック・ワッツによる寓意画、1886年 アメリカの心理学者バーバラ・フレデリクソンは、危機が迫った時にこそ希望が真価を発揮し、新たな創造的可能性を私たちに開くと主張する。[4] フレデリクソンによれば、大きな必要性には、認知的・心理的・社会的・身体的という異なる自己領域から引き出される、幸福や喜び、勇気、エンパワーメント といった肯定的感情とともに、異常に幅広い発想が伴うという。[5] このような前向きな思考は、現実的な楽観主義に基づく場合に実を結ぶのであって、素朴な「偽りの希望」に基づくものではない。[6] [7] 心理学者チャールズ・R・スナイダーは、希望を目標の存在と、その目標達成に向けた確固たる計画の結合に結びつけた。[8] アルフレッド・アドラーも同様に、人間心理における目標追求の核心性を主張していた。[9] エルンスト・ブロッホのような哲学的人類学者も同様の立場を取った。[10] スナイダーはまた、希望と精神的意志力(強靭性)の関連性[11]、ならびに目標に対する現実的な認識(問題志向性)[12]の必要性を強調し、希望と楽 観主義の違いは、前者が願望的思考のように見える可能性があるのに対し、後者は改善された未来への実践的な道筋を見つけるためのエネルギーを提供すると論 じた[13]。D・W・ウィニコットは、子供の反社会的行動を助けを求める叫び、無意識の希望、つまり身近な家族内での抑制が失敗した際に、より広い社会 で支配的な立場にある者たちに対する肯定的な結果への無言の願望の表出と見なした[14]。対象関係論も同様に、分析的転移は過去の葛藤やトラウマを新た に処理できるという無意識の希望によって部分的に動機づけられていると見なしている[15]。 |

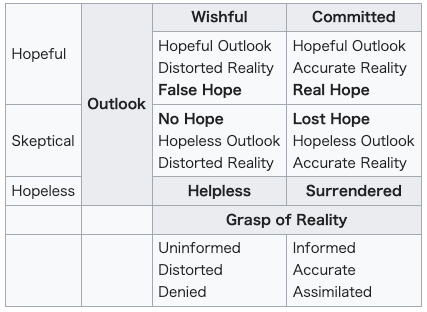

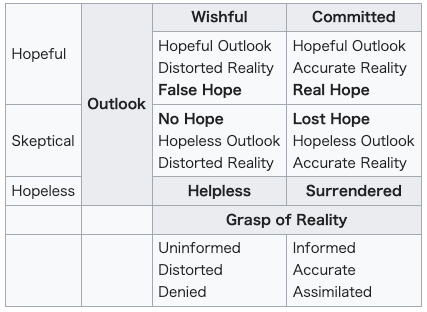

| Hope Theory As a specialist in positive psychology, Snyder studied how hope and forgiveness can impact several aspects of life such as health, work, education, and personal meaning. He postulated that three main things make up hopeful thinking:[16] Goals – Approaching life in a goal-oriented way. Pathways – Finding different ways to achieve your goals. Agency – Believing that you can instigate change and achieve these goals.  A rose expressing hope, at Auschwitz concentration camp In other words, hope was defined as the perceived capability to derive pathways to desired goals and motivate oneself via agency thinking to use those pathways. Snyder argues that individuals who are able to realize these three components and develop a belief in their ability are hopeful people who can establish clear goals, imagine multiple workable pathways toward those goals, and persevere, even when obstacles get in their way. Snyder proposed a "Hope Scale" which considered that a person's determination to achieve their goal is their measured hope. Snyder differentiates between adult-measured hope and child-measured hope. The Adult Hope Scale by Snyder contains 12 questions: 4 measuring 'pathways thinking', 4 measuring 'agency thinking', and 4 that are simply fillers. Each subject responds to each question using an 8-point scale.[17] Fibel and Hale measure hope by combining Snyder's Hope Scale with their own Generalized Expectancy for Success Scale (GESS) to empirically measure hope.[18] Snyder regarded that psychotherapy can help focus attention on one's goals, drawing on tacit knowledge of how to reach them.[19] Similarly, there is an outlook and a grasp of reality to hope, distinguishing No Hope, Lost Hope, False Hope and Real Hope, which differ in terms of viewpoint and realism.[20]  Contemporary philosopher Richard Rorty understands hope as more than goal setting, rather as a metanarrative, a story that serves as a promise or reason for expecting a better future. Rorty as postmodernist believes past meta-narratives, including the Christian story, utilitarianism, and Marxism have proved false hopes; that theory cannot offer social hope; and that liberal man must learn to live without a consensual theory of social hope.[21] Rorty says a new document of promise is needed for social hope to exist again.[22] |

希望理論 ポジティブ心理学の専門家として、スナイダーは希望と許しが健康、仕事、教育、個人的な意味といった人生の様々な側面にどう影響するかを研究した。彼は希望的な思考を構成する三つの主要要素を提唱した:[16] 目標 – 目標指向的な方法で人生に取り組むこと。 経路 – 目標達成のための異なる方法を見つけること。 主体性 – 変化を起こし目標を達成できると信じること。  アウシュヴィッツ強制収容所にある希望を表すバラ つまり、希望とは望ましい目標への道筋を見出し、主体性思考によって自らを動機づけ、その道筋を活用する能力と定義された。 スナイダーは、この三要素を自覚し能力への確信を育める人格が希望に満ちた人間だと主張する。彼らは明確な目標を設定し、その達成に向けた複数の実行可能な経路を想像し、障害に直面しても粘り強く取り組める。 スナイダーは「希望尺度」を提案した。これは目標達成への決意を測定した希望値と考える。彼は成人用希望尺度と児童用希望尺度の区別を設けている。スナイ ダーの成人向け希望尺度には12の質問が含まれる:4問が「経路思考」を測定し、4問が「主体性思考」を測定し、残り4問は単なる埋め合わせである。各被 験者は8段階尺度で各質問に回答する[17]。フィーベルとヘイルは、スナイダーの希望尺度と独自の「成功への一般化期待尺度(GESS)」を組み合わせ て希望を測定し、実証的に希望を計測している。[18] スナイダーは、心理療法が目標達成の暗黙知を活用し、目標への注意を集中させる助けとなると見なした。[19] 同様に、希望には見通しと現実把握があり、視点と現実性の点で異なる「絶望」「喪失した希望」「誤った希望」「真の希望」を区別する。[20]  現代の哲学者リチャード・ローティは、希望を単なる目標設定以上のものと捉えている。むしろそれはメタナラティブ、つまりより良い未来を期待する約束や理 由となる物語なのだ。ポストモダニストとしてのロティは、キリスト教の物語、功利主義、マルクス主義を含む過去のメタナラティブは虚偽の希望であることが 証明されたと考える。理論は社会的希望を提供できず、リベラルな人間は合意に基づく社会的希望の理論なしに生きることを学ばねばならないと主張する [21]。ロティは社会的希望が再び存在するためには、新たな約束の文書が必要だと述べる[22]。 |

| In healthcare Major theories Of the countless models that examine the importance of hope in an individual's life, two major theories have gained a significant amount of recognition in the field of psychology. One of these theories, developed by Charles R. Snyder, argues that hope should be viewed as a cognitive skill that demonstrates an individual's ability to maintain drive in the pursuit of a particular goal.[23] This model reasons that an individual's ability to be hopeful depends on two types of thinking: agency thinking and pathway thinking. Agency thinking refers to an individual's determination to achieve their goals despite possible obstacles, while pathway thinking refers to the ways in which an individual believes they can achieve these personal goals. Snyder's theory uses hope as a mechanism that is most often seen in psychotherapy. In these instances, the therapist helps their client overcome barriers that have prevented them from achieving goals. The therapist would then help the client set realistic and relevant personal goals (i.e. "I am going to find something I am passionate about and that makes me feel good about myself"), and would help them remain hopeful of their ability to achieve these goals, and suggest the correct pathways to do so. Whereas Snyder's theory focuses on hope as a mechanism to overcome an individual's lack of motivation to achieve goals, the other major theory developed by Kaye A. Herth deals more specifically with an individual's future goals as they relate to coping with illnesses.[24] Herth views hope as "a motivational and cognitive attribute that is theoretically necessary to initiate and sustain action toward goal attainment".[25] Establishing realistic and attainable goals in this situation is more difficult, as the individual most likely does not have direct control over the future of their health. Instead, Herth suggests that the goals should be concerned with how the individual is going to personally deal with the illness—"Instead of drinking to ease the pain of my illness, I am going to surround myself with friends and family".[25] While the nature of the goals in Snyder's model differ with those in Herth's model, they both view hope as a way to maintain personal motivation, which ultimately will result in a greater sense of optimism. |

医療分野において 主要な理論 個人の人生における希望の重要性を検証する無数のモデルの中でも、心理学の分野で特に認知されている主要な理論が二つ存在する。その一つはチャールズ・ R・スナイダーが提唱した理論であり、希望は特定の目標追求における意欲を維持する個人の能力を示す認知的スキルとして捉えるべきだと主張する。[23] このモデルによれば、個人の希望を持つ能力は二種類の思考に依存する。すなわち主体性思考と経路思考である。主体性思考とは、障害の可能性にもかかわらず 目標を達成しようとする個人の決意を指す。一方、経路思考とは、個人がこれらの個人的目標を達成できると信じる方法論を指す。 スナイダーの理論は、希望を心理療法において最も頻繁に観察されるメカニズムとして用いる。こうした場合、セラピストはクライアントが目標達成を阻む障壁 を克服する手助けをする。その後、セラピストはクライアントが現実的で関連性のある個人的目標(「自分が情熱を注げ、自己肯定感を得られるものを見つけ る」)を設定するのを支援し、それらの目標達成能力に対する希望を持ち続けられるよう助ける。さらに、達成のための適切な道筋を提案する。 一方、ケイ・A・ハースが提唱した主要理論は、病気への対処に関連する個人の将来目標に特化している[24]。ハースは希望を「目標達成に向けた行動を開 始・持続するために理論的に必要とされる動機付け的・認知的属性」と定義する。[25] この状況下で現実的かつ達成可能な目標を設定することはより困難である。なぜなら、個人は自身の健康の将来を直接的に制御できない可能性が高いからだ。代 わりに、ハースは目標が「病気と個人的に向き合う方法」に焦点を当てるべきだと提案する。「病気の痛みを和らげるために酒を飲む代わりに、友人や家族に囲 まれるようにする」といった具合だ。[25] スナイダーのモデルにおける目標の性質はハースのモデルとは異なるが、両者とも希望を個人的な動機付けを維持する手段と見なしており、最終的にはより大きな楽観主義をもたらす。 |

| Major empirical findings Hope, and more specifically, particularized hope, has been shown to be an important part of the recovery process from illness; it has strong psychological benefits for patients, helping them to cope more effectively with their disease.[26] For example, hope motivates people to pursue healthy behaviors for recovery, such as eating fruits and vegetables, quitting smoking, and engaging in regular physical activity. This not only helps to enhance people's recovery from illnesses but also helps prevent illness from developing in the first place.[27] Patients who maintain high levels of hope have an improved prognosis for life-threatening illness and an enhanced quality of life.[28] Belief and expectation, which are key elements of hope, block pain in patients suffering from chronic illness by releasing endorphins and mimicking the effects of morphine. Consequently, through this process, belief and expectation can set off a chain reaction in the body that can make recovery from chronic illness more likely. This chain reaction is especially evident with studies demonstrating the placebo effect, a situation when hope is the only variable aiding in these patients' recovery.[27] Overall, studies have demonstrated that maintaining a sense of hope during a period of recovery from illness is beneficial. A sense of hopelessness during the recovery period has, in many instances, resulted in adverse health conditions for the patient (i.e. depression and anxiety following the recovery process).[29] Additionally, having a greater amount of hope before and during cognitive therapy has led to decreased PTSD-related depression symptoms in war veterans.[30] Hope has also been found to be associated with more positive perceptions of subjective health. However, reviews of research literature have noted that the connections between hope and symptom severity in other mental health disorders are less clear, such as in cases of individuals with schizophrenia.[31] Hope is a powerful protector against chronic or life-threatening illnesses. A person's hope (even when facing an illness that will likely end their life) can be helpful by finding joy or comfort. It can be created and focused on achieving life goals, such as meeting grandchildren or attending a child's wedding. Hope can be an opportunity for us to process and go through events, that can be traumatic. A setback in life, an accident, or our own final months of living can be times when hope is comfort and serves as a pathway from one stage to the next.[32] Hope is a powerful emotion that drives us to keep working and moving forward. It gives us the power to survive. In a study conducted by Harvard, Curt Richter experimented with 12 wild rats and 12 domesticated rats. The wild rats, known for their great swimming abilities, survived for only about two minutes when placed in a glass container of water with no way of escape. In contrast, the domesticated rats survived for days.[33] Curt attributed this difference to hope. The domesticated rats hoped to be saved from drowning, but the wild rats had no such hope, as they had never experienced rescue. Curt decided to run another experiment with 12 wild rats. He placed them in water, and when they were about to drown, he took them out and held them briefly, creating an experience of hope. He then returned the rats to the water to observe how long they would tread water. Remarkably, they survived just as long as the domesticated rats—about 60 hours. With hope, the rats went from surviving for 2 minutes to treading water for 60 hours. Hope is a powerful emotion. It drives us to move faster, further, and longer than we thought possible. But for hope to thrive, it must be anchored in something more powerful than ourselves. The rats had hope that a saving hand would come and lift them out of the water.[1] |

主要な実証的知見 希望、特に個別化された希望は、病気からの回復過程において重要な要素であることが示されている。患者にとって強い心理的利益をもたらし、疾患への対処を より効果的にする助けとなる。[26] 例えば、希望は人々に回復のための健康的な行動、例えば果物や野菜を食べること、禁煙、定期的な運動などを追求させる動機となる。これは人々の病気からの 回復を促進するだけでなく、そもそも病気が発症するのを防ぐ助けにもなる。[27] 高いレベルの希望を維持する患者は、生命を脅かす病気の予後が改善され、生活の質も向上する。[28] 希望の核心要素である信念と期待は、エンドルフィンの放出やモルヒネ効果の模倣を通じて、慢性疾患苦悩患者の痛みを遮断する。このプロセスにより、信念と 期待は体内で連鎖反応を引き起こし、慢性疾患からの回復を促進し得る。この連鎖反応は、希望が患者の回復を助ける唯一の変数となるプラセボ効果の実証研究 で特に顕著である。[27] 総じて、病気からの回復期に希望感を維持することが有益であることが研究で示されている。回復期における絶望感は、多くの場合、患者の健康悪化(回復過程 後の抑うつや不安など)につながっている。[29] さらに、認知療法の前後においてより強い希望を持つことは、戦争退役軍人のPTSD関連抑うつ症状の軽減につながった。[30] 希望は主観的な健康に対するより前向きな認識とも関連している。しかし、研究文献のレビューでは、統合失調症患者の場合など、他の精神疾患における希望と 症状重症度の関連性は明確ではないと指摘されている。[31] 希望は慢性疾患や生命を脅かす病気に対する強力な防護壁となる。たとえ死に至る可能性の高い病に直面しても、人格は希望によって喜びや慰めを見出すことが できる。孫に会うことや子供の結婚式に出席するなど、人生の目標達成に向けて希望を育み集中することも可能だ。希望は、トラウマとなる出来事を処理し乗り 越える機会となり得る。人生の挫折、事故、あるいは自らの最期の数ヶ月は、希望が慰めとなり、一つの段階から次の段階へと至る道筋となる時である。 [32] 希望は、我々が働き続け前進し続ける原動力となる強力な感情だ。それは我々に生き抜く力を与える。ハーバード大学による研究で、カート・リヒターは12匹 の野生ネズミと12匹の家ネズミを用いて実験を行った。優れた泳ぎで知られる野生ネズミは、脱出手段のない水の入ったガラス容器に入れられると、わずか2 分ほどで死んだ。一方、飼いならされたネズミは数日間生き延びた[33]。カートはこの差を希望に起因すると考えた。飼いならされたネズミは溺死から救わ れることを望んだが、野生ネズミにはそのような希望がなかった。彼らは救助を経験したことがなかったからだ。 カートはさらに12匹の野生ネズミで別の実験を行った。水中に放り込み、溺れかけたところで引き上げて短時間抱きしめることで「救われる」という希望体験 をさせた。その後再び水中に戻し、水面を漂い続ける時間を観察した。驚くべきことに、飼いならされたネズミと同等の約60時間、生存したのである。希望に よって、ネズミの生存時間は2分から60時間へと飛躍したのだ。 希望は強力な感情である。それは我々を、想像以上に速く、遠くへ、長く行動させる原動力となる。しかし希望が育つためには、自分自身よりも強大な何かに根 ざしていなければならない。ネズミたちは、救いの手が差し伸べられ、水から引き上げられるという希望を持っていたのだ。[1] |

| Applications The inclusion of hope in treatment programs has potential in both physical and mental health settings. Hope as a mechanism for improved treatment has been studied in the contexts of PTSD, chronic physical illness, and terminal illness, among other disorders and ailments.[30][31] Within mental health practice, clinicians have suggested using hope interventions as a supplement to more traditional cognitive behavioral therapies.[31] In terms of support for physical illness, research suggests that hope can encourage the release of endorphins and enkephalins, which help to block pain.[27] Impediments There are two main arguments based on judgment against those who are advocates of using hope to help treat severe illnesses. The first of which is that if physicians have too much hope, they may aggressively treat the patient. The physician will hold on to a small shred of hope that the patient may get better. Thus, this causes them to try methods that are costly and may have many side effects. One physician noted[34] that she regretted having hope for her patient; it resulted in her patient suffering through three more years of pain that the patient would not have endured if the physician had realized recovery was unfeasible. The second argument is the division between hope and wishing. Those that are hopeful are actively trying to investigate the best path of action while taking into consideration the obstacles. Research[27] has shown though that many of those who have "hope" are wishfully thinking and passively going through the motions, as if they are in denial about their actual circumstances. Being in denial and having too much hope may negatively impact both the patient and the physician. Benefits The impact that hope can have on a patient's recovery process is strongly supported through both empirical research and theoretical approaches. However, reviews of literature also maintain that more longitudinal and methodologically sound research is needed to establish which hope interventions are actually the most effective, and in what setting (i.e. chronic illness vs. terminal illness).[31] |

応用 治療プログラムに希望を取り入れることは、身体的健康と精神的健康の両方の場面で可能性を秘めている。PTSD、慢性身体疾患、末期疾患をはじめとする様 々な障害や病状において、治療効果向上のメカニズムとしての希望が研究されてきた。[30][31] 精神医療の現場では、臨床医が従来の認知行動療法を補完する手段として希望介入の活用を提案している。[31] 身体疾患の支援に関しては、研究により希望がエンドルフィンやエンケファリンの放出を促し、痛みの遮断に寄与することが示唆されている。[27] 障害 重篤な疾患の治療に希望を活用することを提唱する者に対する批判には、主に二つの論点がある。第一に、医師が過度の希望を抱くと、患者に対して過剰な治療 を行う可能性があるという点だ。医師は患者が回復するかもしれないというわずかな希望にしがみつく。その結果、費用がかかり副作用の多い治療法を試すこと になる。ある医師は[34]、患者に希望を抱いたことを後悔していると述べている。医師が回復が不可能だと気づいていれば、患者はその後3年間も苦悩を引 き延ばす苦しみを受けることはなかっただろう。 第二の論点は、希望と願望の区別だ。希望を持つ者は障害を考慮しつつ最善の行動経路を積極的に模索する。しかし研究[27]によれば、「希望」を持つ者の 多くは現実逃避的な願望を抱き、受動的に形式的な行動を繰り返している。現実を否定し過剰な希望を持つことは、患者と医師双方に悪影響を及ぼしうる。 利点 希望が患者の回復過程に与える影響は、実証的研究と理論的アプローチの両方によって強く支持されている。しかし、文献レビューでは、どの希望介入が実際に 最も効果的か、またどのような状況(慢性疾患対末期疾患など)で効果を発揮するかを確立するためには、より縦断的で方法論的に確かな研究が必要であると主 張している[31]。 |

| In culture In the matter of globalization, hope is focused on economic and social empowerment. Focusing on parts of Asia, hope has taken on a secular or materialistic form in relation to the pursuit of economic growth. Primary examples are the rise of the economies of China and India, correlating with the notion of Chindia. A secondary relevant example is the increased use of contemporary architecture in rising economies, such as the building of the Shanghai World Financial Center, Burj Khalifa and Taipei 101, which has given rise to a prevailing hope within the countries of origin.[35] In chaotic environments hope is transcended without cultural boundaries, Syrian refugee children are supported by UNESCO's education project through creative education and psycho-social assistance.[36] Other inter-cultural support for instilling hope involve food culture, disengaging refugees from trauma through immersing them in their rich cultural past.[37] |

文化において グローバル化の問題では、希望は経済的・社会的エンパワーメントに焦点が当てられている。 アジアの一部に焦点を当てると、希望は経済成長の追求に関連して世俗的あるいは物質主義的な形をとっている。主な例は中国とインドの経済台頭であり、これ は「チンディア」という概念と相関している。二次的な関連例としては、上海ワールドフィナンシャルセンター、ブルジュ・ハリファ、台北101などの建設に 見られるように、新興経済国における現代建築の利用増加が挙げられ、これは母国に広範な希望をもたらしている。[35] 混沌とした環境では、希望は文化的境界を超えて超越される。シリア難民の子どもたちは、ユネスコの教育プロジェクトにより創造的教育と心理社会的支援を通 じて支えられている。[36] 希望を育むための他の異文化間支援には食文化があり、豊かな文化的過去への没入を通じて難民をトラウマから解放する。[37] |

In literature Engraving of Pandora trying to close the box that she had opened out of curiosity. At left, the evils of the world taunt her as they escape. The engraving is based on a painting by F. S. Church. Hope is the thing with feathers that perches in the soul and sings the tune without the words and never stops at all. — Emily Dickinson[38] A classic reference to hope which has entered modern language is the concept that "Hope springs eternal" taken from Alexander Pope's Essay on Man, the phrase reading "Hope springs eternal in the human breast, Man never is, but always to be blest:"[39] Another popular reference, "Hope is the thing with feathers," is from a poem by Emily Dickinson.[40] Hope can be used as an artistic plot device and is often a motivating force for change in dynamic characters. A commonly understood reference from western popular culture is the subtitle "A New Hope" from the original first installment (now considered Episode IV) in the Star Wars science fiction space opera.[41] The subtitle refers to one of the lead characters, Luke Skywalker, who is expected in the future to allow good to triumph over evil within the plot of the films. The swallow has been a symbol of hope, in Aesop's fables and numerous other historic literature.[42] It symbolizes hope, in part because it is among the first birds to appear at the end of winter and the start of spring.[43] Other symbols of hope include the anchor[44] and the dove.[45] Nietzsche took a contrarian but coherent view of hope:- ... Zeus did not wish man, however much he might be tormented by the other evils, to fling away his life, but to go on letting himself be tormented again and again. Therefore he gives Man hope,—in reality it is the worst of all evils, because it prolongs the torments of Man. — Friedrich Nietzsche[46] |

文学における 好奇心から開けてしまった箱を閉じようとするパンドラの彫刻。左側では、逃げ出す世界の悪が彼女を嘲笑している。この彫刻は、F・S・チャーチの絵画を基にしている。 希望とは、魂に止まり、言葉のない歌を歌い、決して止まることのない羽のあるものなのだ。 — エミリー・ディキンソン[38] 現代語にも取り入れられた、希望に関する古典的な引用として、アレクサンダー・ポープの『人間論』から引用された「希望は永遠に湧き出る」という概念があ る。この詩は「希望は人間の胸中に永遠に湧き出る。人間は決して祝福されることはなく、常に祝福されるべき存在である」と綴っている[39]。もう一つの 有名な引用「希望は羽のあるもの」は、エミリー・ディキンソンの詩から引用されている[40]。 希望は芸術的なプロットの装置として使用でき、ダイナミックなキャラクターの変化の動機となる力であることが多い。西洋のポピュラー・カルチャーで広く理 解されている例としては、SFスペースオペラ『スター・ウォーズ』の最初の作品(現在はエピソードIVとみなされている)のサブタイトル「新たなる希望」 がある。このサブタイトルは、映画のストーリーの中で、将来、善が悪に打ち勝つことを期待されている主人公の一人、ルーク・スカイウォーカーを指してい る。 ツバメはイソップ寓話や数多くの歴史的文献において希望の象徴とされてきた[42]。冬の終わりと春の始まりに最初に現れる鳥の一つであることも、その象徴性の一因だ[43]。その他の希望の象徴には錨[44]や鳩[45]がある。 ニーチェは希望について、反論的だが一貫した見解を示した: …ゼウスは、人間が他のあらゆる悪に苦しめられていようとも、その命を投げ出すことを望まなかった。むしろ、人間が繰り返し苦しめられ続けることを許すこ とを望んだのだ。それゆえ彼は人間に希望を与えた。しかし実際には、それはあらゆる悪の中で最悪のものだ。なぜならそれは人間の苦しみを長引かせるからで ある。 — フリードリヒ・ニーチェ[46] |

| In mythology Elpis (Hope) appears in ancient Greek mythology with the story of Zeus and Prometheus. Prometheus stole fire from the god Zeus, which infuriated the supreme god. In turn, Zeus created a box that contained all manners of evil, unbeknownst to the receiver of the box. Pandora opened the box after being warned not to, and unleashed a multitude of harmful spirits that inflicted plagues, diseases, and illnesses on mankind. Spirits of greed, envy, hatred, mistrust, sorrow, anger, revenge, lust, and despair scattered far and wide looking for humans to torment. Inside the box, however, there was also an unreleased healing spirit named Hope. From ancient times, people have recognized that a spirit of hope had the power to heal afflictions and helps them bear times of great suffering, illnesses, disasters, loss, and pain caused by the malevolent spirits and events.[47] In Hesiod's Works and Days, the personification of hope is named Elpis. Norse mythology however considered Hope (Vön) to be the slobber dripping from the mouth of Fenris Wolf:[48] their concept of courage rated most highly a cheerful bravery in the absence of hope.[49] |

神話において エルピス(希望)は、ゼウスとプロメテウスの物語と共に古代ギリシャ神話に登場する。プロメテウスは神ゼウスから火を盗み、この行為は最高神を激怒させ た。これに対しゼウスは、受け取る者が知らないうちにあらゆる悪を封じ込めた箱を作り出した。パンドラは開けるなと警告されながらも箱を開け、疫病や病 気、災いを人類にもたらすマルチチュードの有害な精霊を解き放った。貪欲、嫉妬、憎悪、不信、悲嘆、怒り、復讐、情欲、絶望といった悪霊たちは、人間を苦 しめるべく四方八方に散らばった。しかし箱の中には、まだ解き放たれていない癒しの霊「希望」も閉じ込められていた。古来より人々は、希望の霊が悪霊や災 いによってもたらされる苦悩、病、災害、喪失、痛みを癒し、耐え忍ぶ力を与えると認識してきた。[47] ヘシオドスの『仕事と日々』では、希望の擬人化はエルピスと呼ばれる。 一方、北欧神話では希望(ヴォーン)はフェンリル狼の口から垂れるよだれと見なされていた[48]。彼らの勇気の概念は、希望のない状況での明るい勇敢さを最も高く評価していた[49]。 |

| In religion Hope is a key concept in most major world religions, often signifying the "hoper" believes an individual or a collective group will reach a concept of heaven. Depending on the religion, hope can be seen as a prerequisite for and/or byproduct of spiritual attainment. Judaism The Jewish Encyclopedia notes "tiḳwah" (תקווה) and "seber" as terms for hope, adding that "miḳweh" and "kislah" denote the related concept of "trust" and that "toḥelet" signifies "expectation".[50] Christianity Main article: Hope (virtue)  People collecting the miraculous water in Lourdes, France Hope is one of the three theological virtues of the Christian religion,[51] alongside faith and love.[52] "Hope" in the Holy Bible means "a strong and confident expectation" of future reward (see Titus 1:2). In modern terms, hope is akin to trust and a confident expectation".[53] Paul the Apostle argued that Christ was a source of hope for Christians: "For in this hope we have been saved"[53] (see Romans 8:24). According to the Holman Bible Dictionary, hope is a "trustful expectation...the anticipation of a favorable outcome under God's guidance."[54] In The Pilgrim's Progress, it is Hopeful who comforts Christian in Doubting Castle; while conversely at the entrance to Dante's Hell were the words, "Lay down all hope, you that go in by me".[55] Hinduism In historic literature of Hinduism, hope is referred to with Pratidhi (Sanskrit: प्रतिधी),[56] or Apêksh (Sanskrit: अपेक्ष).[57][58] It is discussed with the concepts of desire and wish. In Vedic philosophy, karma was linked to ritual sacrifices (yajna), hope and success linked to correct performance of these rituals.[59][60] In Vishnu Smriti, the image of hope, morals and work is represented as the virtuous man who rides in a chariot directed by his hopeful mind to his desired wishes, drawn by his five senses, who keeps the chariot on the path of the virtuous, and thus is not distracted by the wrongs such as wrath, greed, and other vices.[61] In the centuries that followed, the concept of karma changed from sacramental rituals to actual human action that builds and serves society and human existence[59][60]–a philosophy epitomized in the Bhagavad Gita. Hope, in the structure of beliefs and motivations, is a long-term karmic concept. In Hindu belief, actions have consequences, and while one's effort and work may or may not bear near term fruits, it will serve the good, that the journey of one's diligent efforts (karma) and how one pursues the journey,[62] sooner or later leads to bliss and moksha.[59][63][64] Buddhism Buddhism's teachings are centered around the concept of hope. It puts those who are suffering on a path to a more harmonious world and better well-being. Hope acts as a light to those who are lost or suffering. Factors of Saddha (faith), wisdom, and aspiration work together to form practical hope. Practical hope is the foundation of putting those suffering on a path toward inner freedom and holistic well-being. It instills the belief in positive outcomes even in the midst of suffering and adversity.[65] |

宗教において 希望は主要な世界宗教のほとんどにおいて核心的な概念であり、往々にして「希望を持つ者」が個人または集団が天国という概念に到達すると信じていることを意味する。宗教によって、希望は精神的達成の前提条件であり、あるいはその副産物と見なされることがある。 ユダヤ教 『ユダヤ百科事典』は「ティクワー」(תקווה)と「セベル」を希望を表す用語として挙げ、さらに「ミクワー」と「キスラー」が関連概念である「信頼」を意味し、「トヘレット」が「期待」を示すと付記している。[50] キリスト教 主な記事:希望(美徳)  フランスのルルドで奇跡の水を集める人々 希望はキリスト教における三つの神学的徳の一つであり[51]、信仰と愛と共に位置づけられる[52]。聖書における「希望」とは、将来の報いに対する 「強く確かな期待」を意味する(テトスへの手紙1:2参照)。現代的な表現では、希望は信頼や確信に満ちた期待に近いものだ[53]。使徒パウロは、キリ ストがキリスト教徒にとっての希望の源であると主張した。「この希望によって、私たちは救われたのである」[53](ローマ人への手紙8:24参照)。 ホルマン聖書辞典によれば、希望とは「信頼に満ちた期待…神の導きのもとでの好ましい結果への予感」である[54]。『天路歴程』では、疑いの城でクリス チャンを慰めるのはホープフルである。一方、ダンテの地獄の入口には「我らを通る者よ、あらゆる希望を捨てよ」という言葉が刻まれていた。[55] ヒンドゥー教 ヒンドゥー教の歴史的文献では、希望はプラティディ(サンスクリット語: प्रतिधी)[56]、あるいはアペクシャ(サンスクリット語: अपेक्ष)で言及される。[57][58] これは欲望や願いの概念と共に論じられる。ヴェーダ哲学では、カルマは儀礼的な犠牲(ヤジュニャ)と結びつき、希望と成功はこれらの儀礼の正しい遂行と結 びついていた。[59] [60] ヴィシュヌ・スムリティでは、希望・道徳・行為のイメージは、徳ある人物として描かれる。彼は希望に満ちた心によって導かれ、五感に引かれるままに望む願 いへと向かう戦車に乗り、その戦車を徳の道に保つ。ゆえに怒りや貪欲といった悪徳に惑わされることはない。[61] その後数世紀にわたり、カルマの概念は儀礼的儀式から、社会と人間の存在を築き支える実際の人間の行動へと変化した[59][60]。この哲学は『バガ ヴァッド・ギーター』に集約されている。信念と動機付けの構造において、希望は長期的なカルマ的概念である。ヒンドゥー教の信仰では、行動には結果が伴 う。努力や働きが短期的に実を結ぶか否かは別として、それは善に資する。勤勉な努力(カルマ)の旅路と、その旅路をどう歩むかが[62]、遅かれ早かれ至 福と解脱(モクシャ)へと導くのである[59][63][64]。 仏教 仏教の教えは希望の概念を中心に据えている。苦悩する者をより調和した世界とより良い幸福への道へと導く。希望は迷いや苦悩する者にとっての灯となる。 サッドハ(信仰)、智慧、志向の要素が相まって実践的な希望を形成する。実践的な希望は、苦悩する者を内なる自由と総合的な幸福へと導く基盤である。苦悩 や逆境の只中であっても、肯定的な結果への信念を植え付けるのだ。 |

| Defeatism Disappointment El Dorado Micawberism Optimism "Self-Reliance" The Principle of Hope Utopianism Spe salvi |

敗北主義 失望 エルドラド ミカウバー主義 楽観主義 「自立」 希望の原理 ユートピア主義 救いは信仰にある |

| References |

|

| Further reading Averill, James R. Rules of hope. Springer-Verlag, 1990. Miceli, Maria and Cristiano Castelfranchi. "Hope: The Power of Wish and Possibility" in Theory Psychology. April 2010 vol. 20 no. 2 251–276. Kierkegaard, Søren A. The Sickness Unto Death. Princeton University Press, 1995. Snyder, C. R. Handbook of hope: theory, measures, & applications. Academic [Press], 2000. Stout, Larry. Ideal Leadership: Time for a Change. Destiny Image, 2006 |

追加文献(さらに読む) アベリル、ジェームズ・R. 『希望の法則』 スプリンガー・ヴェルラッグ、1990年。 ミチェリ、マリアとクリスティアーノ・カステルフランキ。「希望:願いと可能性の力」『理論心理学』2010年4月 第20巻第2号 251–276頁。 キルケゴール、ソレン・A. 『死に至る病』プリンストン大学出版局、1995年。 スナイダー、C. R. 『希望ハンドブック:理論、測定、応用』アカデミック出版、2000年。 スタウト、ラリー『理想的リーダーシップ:変革の時』デスティニー・イメージ、2006年 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hope |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099