ハムレット

Hamlet

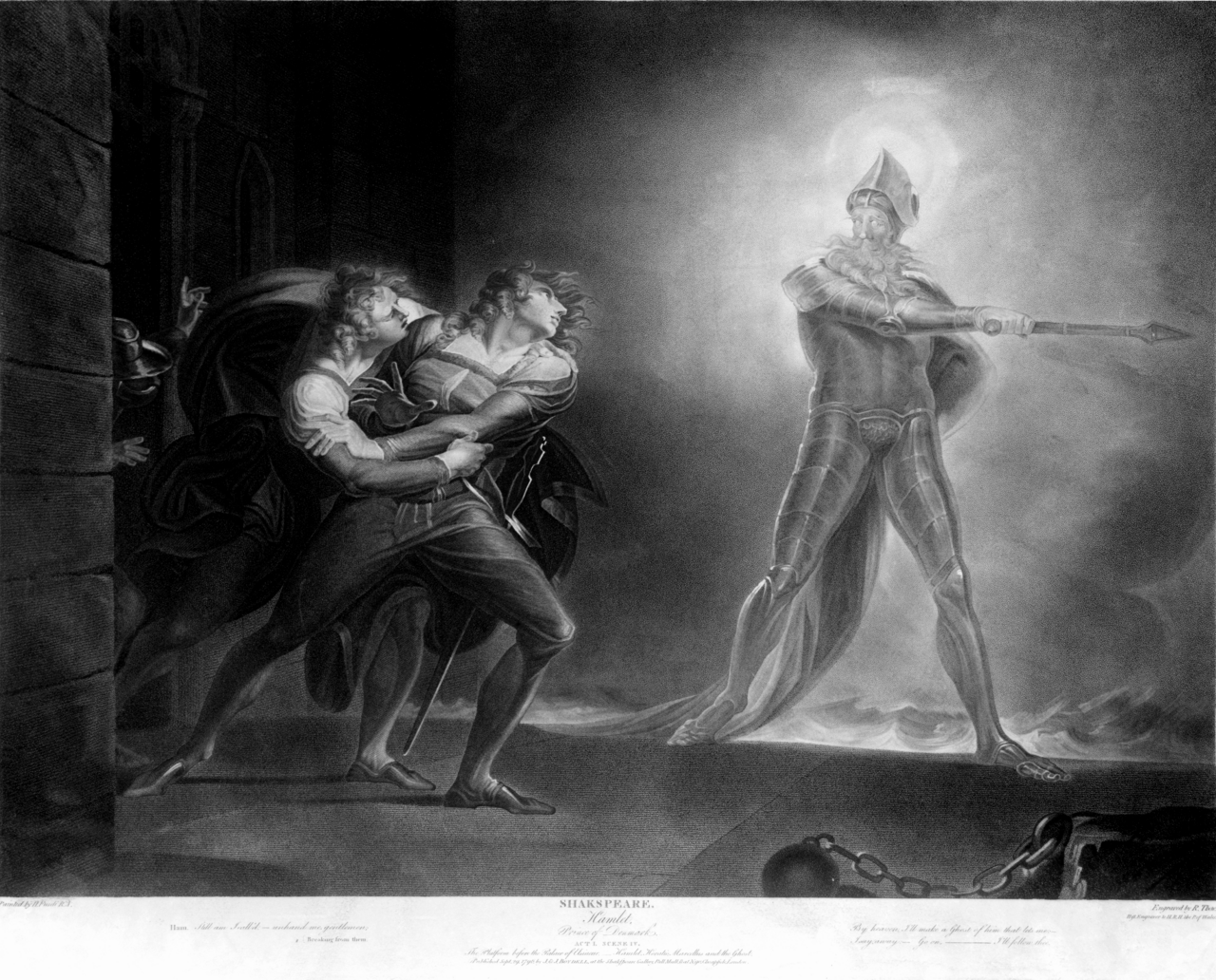

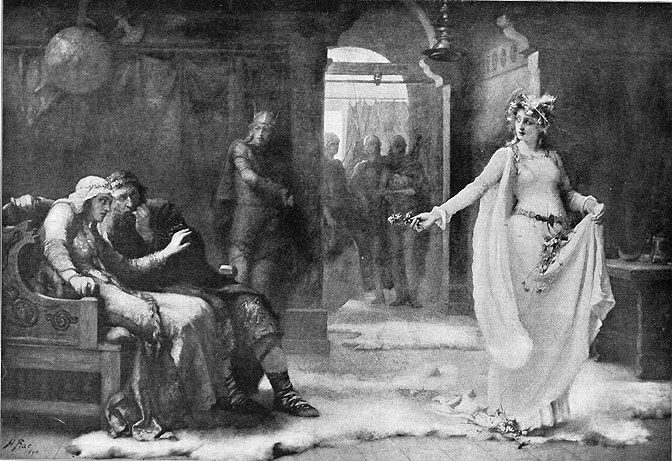

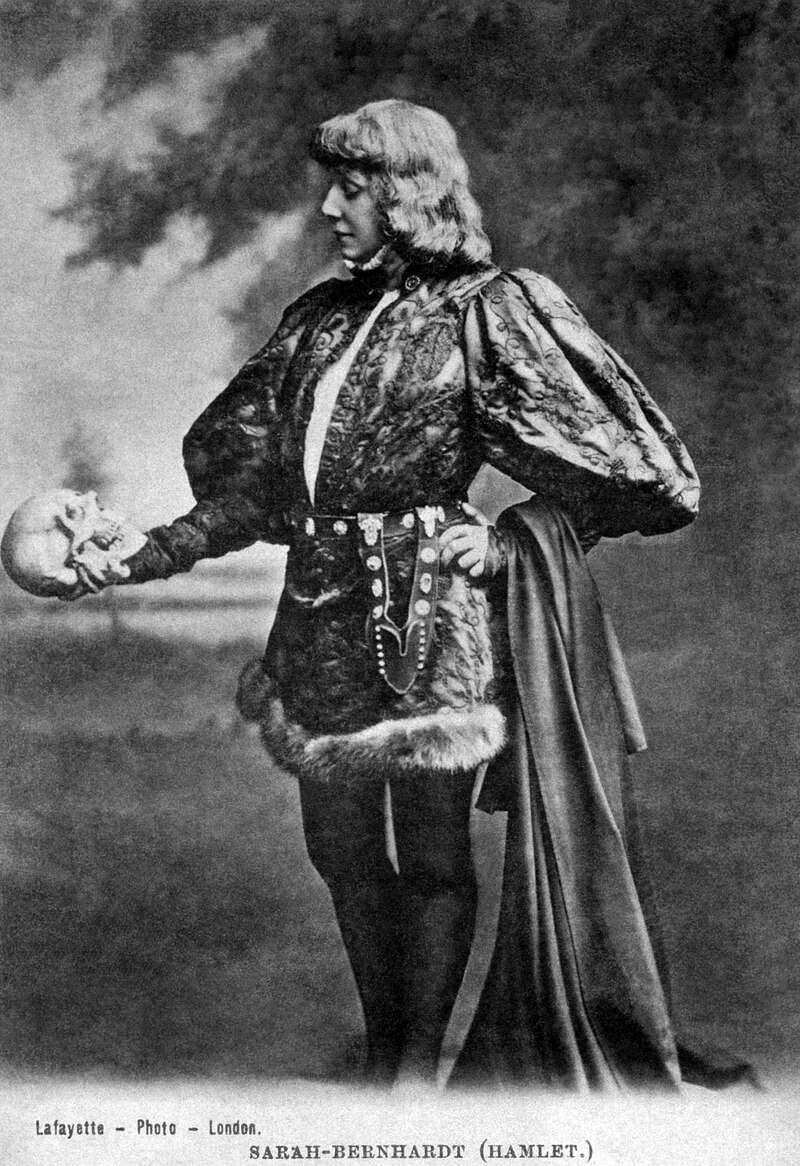

Hamlet tries to show his mother Gertrude his father's ghost (artist: Nicolai A. Abildgaard, c. 1778).

☆ハムレットHamlet(/ˈhæml↪Ll26At/)

は、ウィリアム・シェイクスピアによって1599年から1601年の間に書かれた悲劇である。シェイクスピア最長の戯曲である。デンマークを舞台に、ハム

レット王子と、ハムレットの父を殺して王位を奪いハムレットの母と結婚しようとした叔父クローディアスへの復讐の企てが描かれる。ハムレットは「英語にお

ける最も強力で影響力のある悲劇」のひとつとされ、そのストーリーは「無限に語り継がれ、翻案され続ける」[1]。各版には、他の版で欠落している台詞や

箇所が含まれている[3]。

シェイクスピアの戯曲は、古代ギリシャ悲劇からエリザベス朝演劇まで、多くの作品が出典として指摘されている。アーデン・シェイクスピアの編集者は、

「ソース・ハンティング」という考え方に疑問を呈しており、「ソース・ハンティング」とは、作者が常に他の作品からアイデアを得て自分の作品にすることを

前提とし、作者が独創的なアイデアを持つことも、オリジネーターであることもあり得ないと示唆していると指摘している。シェイクスピアが執筆した当時、父

親の仇を討つ息子の話や、敵を出し抜くために愚かなふりをする賢い仇討ちの息子の話はたくさんあった。シェイクスピアも知っていたと思われる古代ローマ人

のルキウス・ユニウス・ブルトゥスの話や、13世紀の年代記作家サクソ・グラマティコスが『ゲスタ・ダノルム』にラテン語で書き残し、1514年にパリで

印刷したアムレスの話もその中に含まれる。アムレスの物語はその後、16世紀の学者フランソワ・ド・ベルフォレストによって翻案され、1570年にフラン

ス語で出版された。この物語には、シェイクスピアの『ハムレット』と共通する多くのプロット要素や主要な登場人物があり、シェイクスピアに見られる他の要

素は欠けている。ベルフォレストの物語は『ハムレット』が書かれた後の1608年に初めて英語で出版されたが、シェイクスピアはフランス語版でこの物語に

出会っていた可能性がある[4]。

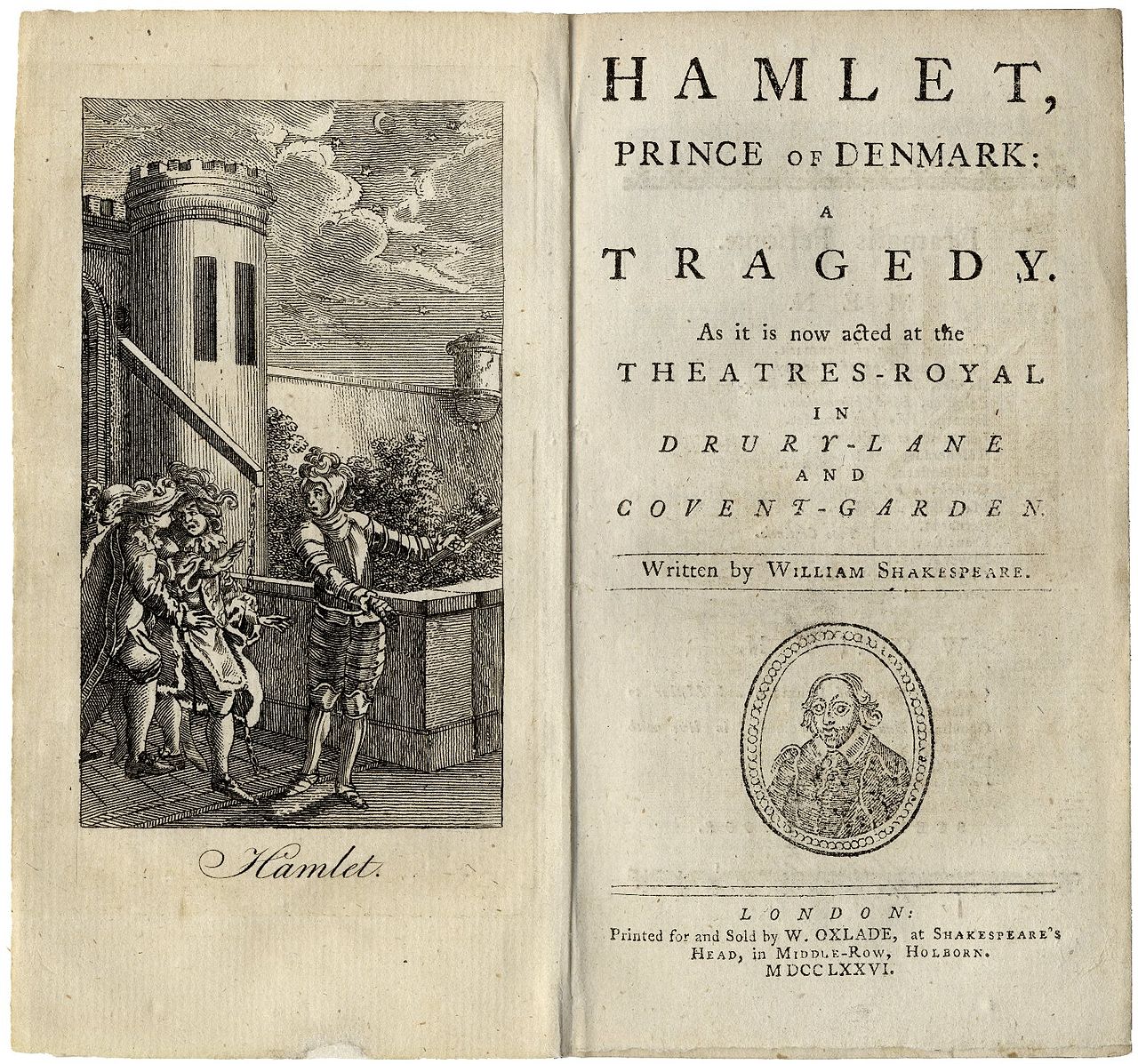

| The Tragedy of

Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, often shortened to Hamlet (/ˈhæmlɪt/), is a

tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601.

It is Shakespeare's longest play. Set in Denmark, the play depicts

Prince Hamlet and his attempts to exact revenge against his uncle,

Claudius, who has murdered Hamlet's father in order to seize his throne

and marry Hamlet's mother. Hamlet is considered among the "most

powerful and influential tragedies in the English language", with a

story capable of "seemingly endless retelling and adaptation by

others."[1] It is widely considered one of the greatest plays of all

time.[2] Three different early versions of the play are extant: the

First Quarto (Q1, 1603); the Second Quarto (Q2, 1604); and the First

Folio (F1, 1623). Each version includes lines and passages missing from

the others.[3] Many works have been pointed to as possible sources for Shakespeare's play, from ancient Greek tragedies to Elizabethan dramas. The editors of the Arden Shakespeare question the idea of "source hunting", pointing out that it presupposes that authors always require ideas from other works for their own, and suggests that no author can have an original idea or be an originator. When Shakespeare wrote, there were many stories about sons avenging the murder of their fathers, and many about clever avenging sons pretending to be foolish in order to outsmart their foes. This would include the story of the ancient Roman, Lucius Junius Brutus, which Shakespeare apparently knew, as well as the story of Amleth, which was preserved in Latin by 13th-century chronicler Saxo Grammaticus in his Gesta Danorum, and printed in Paris in 1514. The Amleth story was subsequently adapted and then published in French in 1570 by the 16th-century scholar François de Belleforest. It has a number of plot elements and major characters in common with Shakespeare's Hamlet, and lacks others that are found in Shakespeare. Belleforest's story was first published in English in 1608, after Hamlet had been written, though it is possible that Shakespeare had encountered it in the French-language version.[4] |

ハムレット(/ˈhæml↪Ll26At/)は、ウィリアム・シェイク

スピアによって1599年から1601年の間に書かれた悲劇である。シェイクスピア最長の戯曲である。デンマークを舞台に、ハムレット王子と、ハムレット

の父を殺して王位を奪いハムレットの母と結婚しようとした叔父クローディアスへの復讐の企てが描かれる。ハムレットは「英語における最も強力で影響力のあ

る悲劇」のひとつとされ、そのストーリーは「無限に語り継がれ、翻案され続ける」[1]。各版には、他の版で欠落している台詞や箇所が含まれている

[3]。 シェイクスピアの戯曲は、古代ギリシャ悲劇からエリザベス朝演劇まで、多くの作品が出典として指摘されている。アーデン・シェイクスピアの編集者は、 「ソース・ハンティング」という考え方に疑問を呈しており、「ソース・ハンティング」とは、作者が常に他の作品からアイデアを得て自分の作品にすることを 前提とし、作者が独創的なアイデアを持つことも、オリジネーターであることもあり得ないと示唆していると指摘している。シェイクスピアが執筆した当時、父 親の仇を討つ息子の話や、敵を出し抜くために愚かなふりをする賢い仇討ちの息子の話はたくさんあった。シェイクスピアも知っていたと思われる古代ローマ人 のルキウス・ユニウス・ブルトゥスの話や、13世紀の年代記作家サクソ・グラマティコスが『ゲスタ・ダノルム』にラテン語で書き残し、1514年にパリで 印刷したアムレスの話もその中に含まれる。アムレスの物語はその後、16世紀の学者フランソワ・ド・ベルフォレストによって翻案され、1570年にフラン ス語で出版された。この物語には、シェイクスピアの『ハムレット』と共通する多くのプロット要素や主要な登場人物があり、シェイクスピアに見られる他の要 素は欠けている。ベルフォレストの物語は『ハムレット』が書かれた後の1608年に初めて英語で出版されたが、シェイクスピアはフランス語版でこの物語に 出会っていた可能性がある[4]。 |

| Characters Main article: Characters in Hamlet Hamlet – son of the late king and nephew of the present king, Claudius Claudius – King of Denmark, Hamlet's uncle and brother to the former king Gertrude – Queen of Denmark and Hamlet's mother Polonius – chief counsellor to the king Ophelia – Polonius's daughter Horatio – friend of Hamlet Laertes – Polonius's son Voltemand and Cornelius – courtiers Rosencrantz and Guildenstern – courtiers, friends of Hamlet Osric – a courtier Marcellus – an officer Bernardo – an officer (spelled Barnardo or Barnard in quarto versions) Francisco – a soldier Reynaldo – Polonius's servant Ghost – the ghost of Hamlet's father, King Hamlet Fortinbras – prince of Norway Gravediggers – a pair of sextons Player King, Player Queen, Lucianus, etc. – players |

登場人物 主な記事 ハムレット』の登場人物 ハムレット - 故国王の息子であり、現国王クローディアスの甥である。 クローディアス - デンマーク王、ハムレットの叔父で前王の弟。 ガートルード - デンマーク王妃でハムレットの母 ポローニアス......王の参謀長 オフィーリア - ポローニアスの娘 ホレイショ - ハムレットの友人 ラールテス - ポローニアスの息子 ヴォルテマンドとコーネリアス - 廷臣 ローゼンクランツとギルデンスターン - 廷臣、ハムレットの友人 オスリック - 廷臣 マーセラス - 将校 Bernardo - 将校(四六版ではBarnardoまたはBarnardと表記される) フランシスコ - 兵士 レイナルド - ポローニアスの使用人 Ghost - ハムレットの父、ハムレット王の亡霊 Fortinbras - ノルウェーの王子 Gravediggers - 六人組の墓掘り人 王役、王妃役、ルシアヌス役など - プレイヤー |

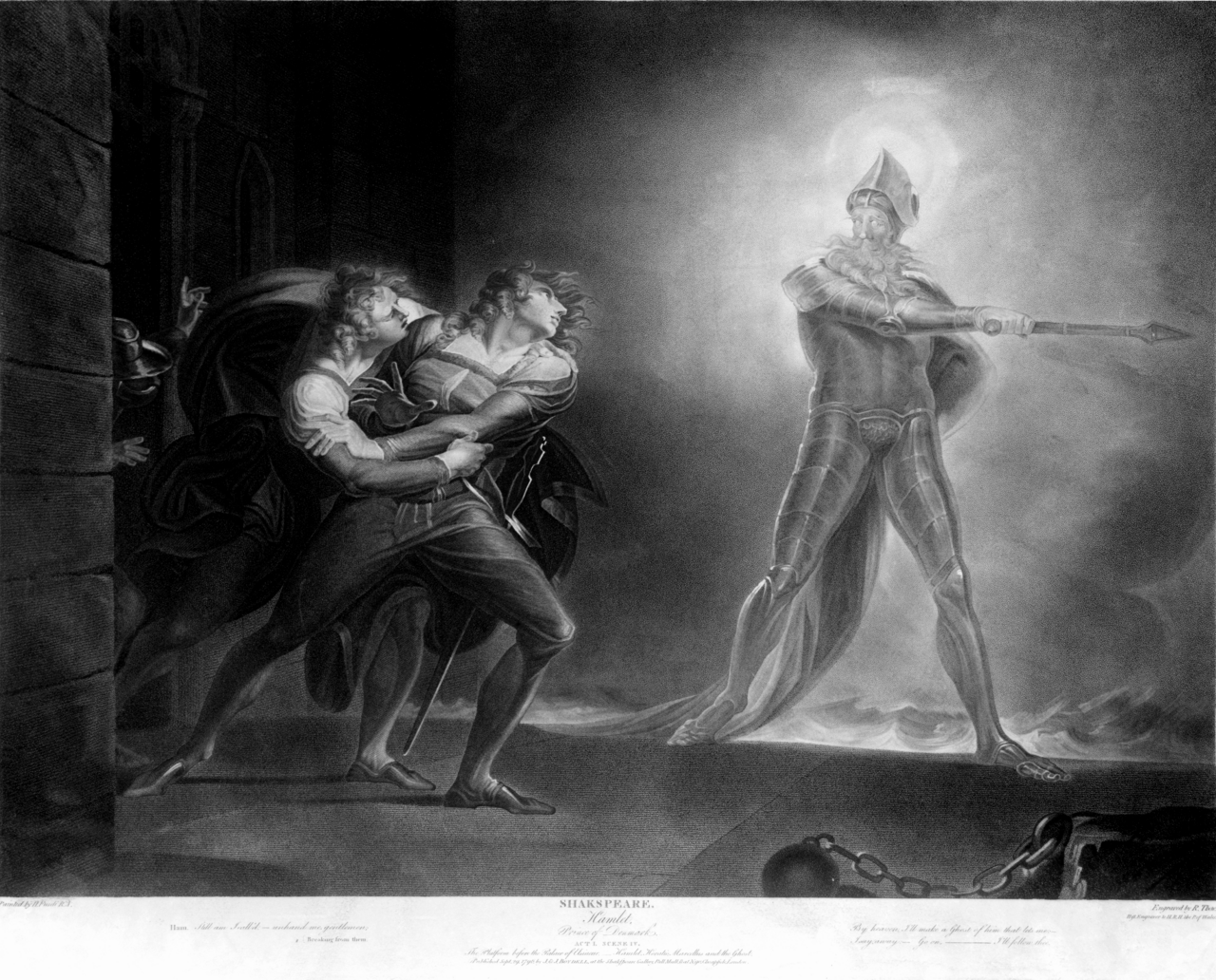

Plot Kronborg Castle is immortalized as Elsinore in the play Hamlet Act I Prince Hamlet of Denmark is the son of the recently deceased King Hamlet, and nephew of King Claudius, his father's brother and successor. Claudius hastily married King Hamlet's widow, Gertrude, Hamlet's mother, and took the throne for himself. Denmark has a long-standing feud with neighbouring Norway, in which King Hamlet slew King Fortinbras of Norway in a battle some years ago. Although Denmark defeated Norway and the Norwegian throne fell to King Fortinbras's infirm brother, Denmark fears that an invasion led by the dead Norwegian king's son, Prince Fortinbras, is imminent. On a cold night on the ramparts of Elsinore, the Danish royal castle, the sentries Bernardo and Marcellus discuss a ghost resembling the late King Hamlet which they have recently seen, and bring Prince Hamlet's friend Horatio as a witness. After the ghost appears again, the three vow to tell Prince Hamlet what they have witnessed. The court gathers the next day, and King Claudius and Queen Gertrude discuss affairs of state with their elderly adviser Polonius. Claudius grants permission for Polonius's son Laertes to return to school in France, and he sends envoys to inform the King of Norway about Fortinbras. Claudius also questions Hamlet regarding his continuing to grieve for his father, and forbids him to return to his university in Wittenberg. After the court exits, Hamlet despairs of his father's death and his mother's hasty remarriage. Learning of the ghost from Horatio, Hamlet resolves to see it himself.  Horatio, Hamlet, and the ghost (Artist: Henry Fuseli, 1789)[5] As Polonius's son Laertes prepares to depart for France, Polonius offers him advice that culminates in the maxim "to thine own self be true."[6] Polonius's daughter, Ophelia, admits her interest in Hamlet, but Laertes warns her against seeking the prince's attention, and Polonius orders her to reject his advances. That night on the rampart, the ghost appears to Hamlet, tells the prince that he was murdered by Claudius (by pouring poison into his ear as he slept), and demands that Hamlet avenge the murder. Hamlet agrees, and the ghost vanishes. The prince confides to Horatio and the sentries that from now on he plans to "put an antic disposition on", or act as though he has gone mad. Hamlet forces them to swear to keep his plans for revenge secret; however, he remains uncertain of the ghost's reliability. |

プロット クロンボー城は、戯曲『ハムレット』の中でエルシノアとして不朽の名声を博している。 第1幕 デンマークの王子ハムレットは、亡くなったばかりのハムレット王の息子であり、父の弟で後継者のクローディアス王の甥である。クローディアスはハムレット 王の未亡人、ハムレットの母ガートルードと急遽結婚し、王位を奪った。デンマークは隣国ノルウェーと長年の確執があり、ハムレット王は数年前の戦いでノル ウェーのフォーティンブラス王を殺害している。デンマークはノルウェーに勝利し、ノルウェーの王位はフォーティンブラス王の病弱な弟に譲ったが、デンマー クは死んだノルウェー王の息子フォーティンブラス王子が率いる侵略が間近に迫っていることを恐れている。 寒い夜、デンマーク王城エルシノアの城壁で、見張りのベルナルドとマーセラスは、最近見た亡きハムレット王に似た幽霊について語り合い、ハムレット王子の 友人ホレイショを目撃者として連れてくる。幽霊が再び現れた後、3人は自分たちが目撃したことをハムレット王子に話すことを誓う。 翌日、宮廷が集まり、クローディアス王とガートルード王妃は、年老いた顧問ポローニアスと国政について話し合う。クローディアスは、ポローニアスの息子 ラールテスがフランスの学校に戻ることを許可し、フォーティンブラスについてノルウェー王に知らせる使者を送る。クローディアスはまた、ハムレットが父の 死を悲しみ続けていることを問い詰め、彼がヴィッテンベルクの大学に戻ることを禁じる。宮廷が去った後、ハムレットは父の死と母の早すぎる再婚に絶望す る。ホレイショから亡霊のことを聞いたハムレットは、自分も亡霊に会うことを決意する。  ホレイショ、ハムレット、幽霊(画家:ヘンリー・フューセリ、1789年)[5]。 ポローニアスの娘オフィーリアはハムレットに興味があることを認めるが、ラエルテスは王子の気を引こうとしないよう忠告し、ポローニアスは彼の誘いを断る よう命じる。その夜、城壁の上で亡霊がハムレットの前に現れ、自分がクローディアスに殺されたこと(寝ている彼の耳に毒を流し込まれたこと)を告げ、ハム レットに仇討ちを要求する。ハムレットは承諾し、幽霊は消える。王子はホレイショと衛兵たちに、これからは「気違いじみた性格になる」、つまり気が狂った かのように振る舞うつもりだと打ち明ける。ハムレットは彼らに、復讐の計画を秘密にしておくことを誓わせるが、幽霊の信頼性には不安が残る。 |

| Act II Ophelia rushes to her father, telling him that Hamlet arrived at her door the prior night half-undressed and behaving erratically. Polonius blames love for Hamlet's madness and resolves to inform Claudius and Gertrude. As he enters to do so, the king and queen are welcoming Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, two student acquaintances of Hamlet, to Elsinore. The royal couple has requested that the two students investigate the cause of Hamlet's mood and behaviour. Additional news requires that Polonius wait to be heard: messengers from Norway inform Claudius that the king of Norway has rebuked Prince Fortinbras for attempting to re-fight his father's battles. The forces that Fortinbras had conscripted to march against Denmark will instead be sent against Poland, though they will pass through Danish territory to get there. Polonius tells Claudius and Gertrude his theory regarding Hamlet's behaviour, and then speaks to Hamlet in a hall of the castle to try to learn more. Hamlet feigns madness and subtly insults Polonius all the while. When Rosencrantz and Guildenstern arrive, Hamlet greets his "friends" warmly but quickly discerns that they are there to spy on him for Claudius. Hamlet admits that he is upset at his situation but refuses to give the true reason, instead remarking "What a piece of work is a man". Rosencrantz and Guildenstern tell Hamlet that they have brought along a troupe of actors that they met while travelling to Elsinore. Hamlet, after welcoming the actors and dismissing his friends-turned-spies, asks them to deliver a soliloquy about the death of King Priam, as witnessed by Queen Hecuba, at the climax of the Trojan War. Hamlet then asks the actors to stage The Murder of Gonzago, a play featuring a death in the style of his father's murder. Hamlet intends to study Claudius's reaction to the play, and thereby determine the truth of the ghost's story of Claudius's guilt. |

第2幕 オフィーリアは父のもとを訪れ、ハムレットが前夜、半裸で玄関に現れ、挙動不審になったと告げる。ポローニアスはハムレットの狂気を愛のせいにし、クロー ディアスとガートルードに知らせる決意をする。王と王妃は、ハムレットの学生時代の知り合いであるローゼンクランツとギルデンスターンをエルシノアに迎え る。王夫妻は、二人の学生にハムレットの気分と行動の原因を調査するよう要請している。ノルウェーからの使者がクローディアスに、ノルウェー王が父の戦い に再挑戦しようとしたフォーティンブラス王子を叱責したと知らせる。フォーティンブラスがデンマークへの進軍のために徴兵した軍勢は、デンマーク領を通過 するものの、代わりにポーランドに送られることになる。 ポローニアスはクローディアスとガートルードにハムレットの行動に関する推理を話し、さらに詳しく知ろうと城の広間でハムレットに話しかける。ハムレット は狂気を装い、ポローニアスをさりげなく侮辱する。ローゼンクランツとギルデンスターンが到着すると、ハムレットは 「友人たち 」を温かく迎えるが、すぐに彼らがクローディアスのために自分を監視しに来たのだと見破る。ハムレットは自分の置かれた状況に動揺していることを認める が、本当の理由を言おうとせず、代わりに「人間とはなんという出来損ないだろう」と言う。ローゼンクランツとギルデンスターンはハムレットに、エルシノア への旅で知り合った役者一座を連れてきたことを告げる。ハムレットは俳優たちを歓迎し、友人からスパイになった者たちを追い出した後、彼らにトロイ戦争の クライマックスで王妃ヘクバが目撃したプリアモス王の死についての独り言を頼む。そしてハムレットは、俳優たちに『ゴンザーゴの死』を上演するよう依頼す る。ハムレットは、この芝居に対するクローディアスの反応を調べ、それによってクローディアスが罪を犯したという幽霊の話の真偽を見極めるつもりなのだ。 |

| Act III Polonius forces Ophelia to return Hamlet's love letters to the prince while he and Claudius secretly watch in order to evaluate Hamlet's reaction. Hamlet is walking alone in the hall as the King and Polonius await Ophelia's entrance. Hamlet muses on thoughts of life versus death. When Ophelia enters and tries to return Hamlet's things, Hamlet accuses her of immodesty and cries "get thee to a nunnery", though it is unclear whether this, too, is a show of madness or genuine distress. His reaction convinces Claudius that Hamlet is not mad for love. Shortly thereafter, the court assembles to watch the play Hamlet has commissioned. After seeing the Player King murdered by his rival pouring poison in his ear, Claudius abruptly rises and runs from the room; for Hamlet, this is proof of his uncle's guilt.  Hamlet mistakenly stabs Polonius (Artist: Coke Smyth, 19th century). Gertrude summons Hamlet to her chamber to demand an explanation. Meanwhile, Claudius talks to himself about the impossibility of repenting, since he still has possession of his ill-gotten goods: his brother's crown and wife. He sinks to his knees. Hamlet, on his way to visit his mother, sneaks up behind him but does not kill him, reasoning that killing Claudius while he is praying will send him straight to heaven while his father's ghost is stuck in purgatory. In the queen's bedchamber, Hamlet and Gertrude fight bitterly. Polonius, spying on the conversation from behind a tapestry, calls for help as Gertrude, believing Hamlet wants to kill her, calls out for help herself. Hamlet, believing it is Claudius, stabs wildly, killing Polonius, but he pulls aside the curtain and sees his mistake. In a rage, Hamlet brutally insults his mother for her apparent ignorance of Claudius's villainy, but the ghost enters and reprimands Hamlet for his inaction and harsh words. Unable to see or hear the ghost herself, Gertrude takes Hamlet's conversation with it as further evidence of madness. After begging the queen to stop sleeping with Claudius, Hamlet leaves, dragging Polonius's corpse away. |

第3幕 ポローニアスはオフィーリアにハムレットの恋文を王子に返させるが、その様子を自分とクローディアスが密かに見守り、ハムレットの反応をうかがっていた。 王とポローニアスがオフィーリアの入場を待つ中、ハムレットは広間を一人で歩いている。ハムレットは生と死について考える。オフィーリアが入ってきてハム レットのものを返そうとすると、ハムレットは彼女の不品行を非難し、「汝を尼僧院に」と叫ぶが、これも狂気の表れなのか、本物の苦悩なのかは不明である。 彼の反応を見て、クローディアスはハムレットが恋のために狂っているのではないと確信する。その直後、ハムレットが依頼した芝居を見るために宮廷が集ま る。ライバルが耳に毒を流し込んで王が殺されるのを見たクローディアスは、突然立ち上がり部屋から逃げ出す。  ハムレットは誤ってポローニアスを刺してしまう(画家:コーク・スミス、19世紀)。 ガートルードはハムレットを寝室に呼び、説明を求める。一方クローディアスは、兄の王位と妻という不正に得た財産をまだ手にしているため、悔い改めること は不可能だと独り言を言う。彼は膝をつく。ハムレットは母を訪ねる途中、彼の背後に忍び寄るが、彼が祈っている間にクローディアスを殺せば、父の亡霊が煉 獄に囚われている間に自分は天国に直行できると考え、彼を殺さなかった。王妃の寝室では、ハムレットとガートルードが激しく争う。ハムレットが自分を殺そ うとしていると思ったガートルードが自ら助けを求めると、タペストリーの陰から会話を覗いていたポローニアスが助けを求める。 ハムレットはクローディアスだと思い、乱暴に刺しポローニアスを殺すが、カーテンを引いて自分の間違いに気づく。怒りに駆られたハムレットは、クローディ アスの悪事を知らなかったと思われる母を残酷に侮辱するが、そこに亡霊が現れ、ハムレットの不作為と辛辣な言葉を叱責する。自分では幽霊を見ることも聞く こともできないガートルードは、ハムレットと幽霊との会話を、狂気のさらなる証拠と受け止める。王妃にクローディアスと寝るのをやめるよう懇願したハム レットは、ポローニアスの亡骸を引きずって立ち去る。 |

| Act IV Hamlet jokes with Claudius about where he has hidden Polonius's body, and the king, fearing for his life, sends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to accompany Hamlet to England with a sealed letter to the English king requesting that Hamlet be executed immediately. Unhinged by grief at Polonius's death, Ophelia wanders Elsinore. Laertes arrives back from France, enraged by his father's death and his sister's madness. Claudius convinces Laertes that Hamlet is solely responsible, but a letter soon arrives indicating that Hamlet has returned to Denmark, foiling Claudius's plan. Claudius switches tactics, proposing a fencing match between Laertes and Hamlet to settle their differences. Laertes will be given a poison-tipped foil, and, if that fails, Claudius will offer Hamlet poisoned wine as a congratulation. Gertrude interrupts to report that Ophelia has drowned, though it is unclear whether it was suicide or an accident caused by her madness. |

第4幕 ハムレットはクローディアスとポローニアスの死体の隠し場所について冗談を言い合うが、王は身の危険を感じ、ローゼンクランツとギルデンスターンをハムレットに同行させ、ハムレットを即刻処刑するよう求める英国王宛ての封書を持たせて英国に向かわせる。 オフィーリアはポローニアスの死を悲しみ、エルシノアをさまよう。父親の死と妹の狂気に怒り狂ったラールテスがフランスから戻ってくる。クローディアス は、ハムレットだけの責任だとラールテスを説得するが、すぐにハムレットがデンマークに戻ったことを示す手紙が届き、クローディアスの計画は失敗に終わ る。クローディアスは戦術を変え、ラールテスとハムレットにフェンシングの試合を申し込む。ラールテスには先端に毒を塗った矛を持たせ、失敗した場合はク ローディアスがハムレットに毒入りのワインを贈って祝福する。ガートルードが割って入り、オフィーリアが溺死したことを報告するが、自殺か狂気による事故 かは不明だ。 |

Act V The gravedigger scene.[7] (Artist: Eugène Delacroix, 1839) Horatio has received a letter from Hamlet, explaining that the prince escaped by negotiating with pirates who attempted to attack his England-bound ship, and the friends reunite offstage. Two gravediggers discuss Ophelia's apparent suicide while digging her grave. Hamlet arrives with Horatio and banters with one of the gravediggers, who unearths the skull of a jester from Hamlet's childhood, Yorick. Hamlet picks up the skull, saying "Alas, poor Yorick" as he contemplates mortality. Ophelia's funeral procession approaches, led by Laertes. Hamlet and Horatio initially hide, but when Hamlet realizes that Ophelia is the one being buried, he reveals himself, proclaiming his love for her. Laertes and Hamlet fight by Ophelia's graveside, but the brawl is broken up. Back at Elsinore, Hamlet explains to Horatio that he had discovered Claudius's letter among Rosencrantz and Guildenstern's belongings and replaced it with a forged copy indicating that his former friends should be killed instead. A foppish courtier, Osric, interrupts the conversation to deliver the fencing challenge to Hamlet from Laertes. Hamlet, despite Horatio's pleas, accepts it. Hamlet does well at first, leading the match by two hits to none, and Gertrude raises a toast to him using the poisoned glass of wine Claudius had set aside for Hamlet. Claudius tries to stop her but is too late: she drinks, and Laertes realizes the plot will be revealed. Laertes slashes Hamlet with his poisoned blade. In the ensuing scuffle, they switch weapons, and Hamlet wounds Laertes with his own poisoned sword. Gertrude collapses and, claiming she has been poisoned, dies. In his dying moments, Laertes reconciles with Hamlet and reveals Claudius's plan. Hamlet rushes at Claudius and kills him. As the poison takes effect, Hamlet, hearing that Fortinbras is marching through the area, names the Norwegian prince as his successor. Horatio, distraught at the thought of being the last survivor and living whilst Hamlet does not, says he will commit suicide by drinking the dregs of Gertrude's poisoned wine, but Hamlet begs him to live on and tell his story. Hamlet dies in Horatio's arms, proclaiming "the rest is silence". Fortinbras, who was ostensibly marching towards Poland with his army, arrives at the palace, along with an English ambassador bringing news of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern's deaths. Horatio promises to recount the full story of what happened, and Fortinbras, seeing the entire Danish royal family dead, takes the crown for himself and orders a military funeral to honour Hamlet. |

第5幕 墓掘り人の場面[7](画家:ウジェーヌ・ドラクロワ、1839年) ホレイショはハムレットから手紙を受け取り、王子がイギリス行きの船を襲おうとした海賊と交渉して脱出したことを説明し、友人たちは舞台袖で再会する。二 人の墓掘り人がオフィーリアの墓を掘りながら、オフィーリアの自殺について話し合っている。ハムレットはホレイショと共に到着し、墓掘り人の一人と談笑す る。彼はハムレットの幼少時代の道化師ヨリックの頭蓋骨を発掘する。ハムレットはその頭蓋骨を拾い上げ、「哀れなヨリック」と言いながら死について考え る。レアテスを先頭にオフィーリアの葬列が近づいてくる。ハムレットとホレイショは最初隠れていたが、ハムレットはオフィーリアが葬られる側だとわかる と、正体を現し、彼女への愛を宣言する。ラールテスとハムレットはオフィーリアの墓前で争うが、乱闘は収まる。 エルシノアに戻ったハムレットは、ローゼンクランツとギルデンスターンの遺品の中からクローディアスの手紙を発見し、代わりにかつての友人を殺すよう示す 偽造の手紙に差し替えたことをホレイショに説明する。洒落た廷臣オスリックが会話に割って入り、レールテスからハムレットにフェンシングの挑戦状を渡す。 ハムレットはホレイショの懇願にもかかわらず、それを受け入れる。ハムレットはまずまずの成績を収め、試合は2勝1敗でリードする。ガートルードは、ク ローディアスがハムレットのために用意しておいた毒入りワインで乾杯する。クローディアスはハムレットを止めようとするが遅すぎた。ラールテスは毒刃でハ ムレットを切りつける。ハムレットは毒入りの剣でラールテスを傷つける。ガートルードは倒れ、毒を盛られたと言って息絶える。死の間際、ラールテスはハム レットと和解し、クローディアスの計画を明かす。ハムレットはクローディアスに突進し、彼を殺す。毒が効き始めると、ハムレットはフォーティンブラスがこ の地域を行進していると聞き、ノルウェーの王子を後継者に指名する。ホレイショは、自分が最後の生き残りであること、ハムレットが生きていない間に自分が 生きていることに心を痛め、ガートルードの毒入りのワインの残りを飲んで自殺すると言うが、ハムレットは生き延びて自分の話をするよう懇願する。ハムレッ トはホレイショの腕の中で「あとは沈黙だ」と宣言して死ぬ。表向きは軍を率いてポーランドに向かっていたフォーティンブラスが、ローゼンクランツとギルデ ンスターンの死の知らせを携えて英国大使とともに宮殿に到着する。ホレイショは事件の全貌を語ることを約束するが、フォーティンブラスはデンマーク王家の 一族が全員死んだのを見て、王冠を自分のものにし、ハムレットを讃えるための軍葬を命じる。 |

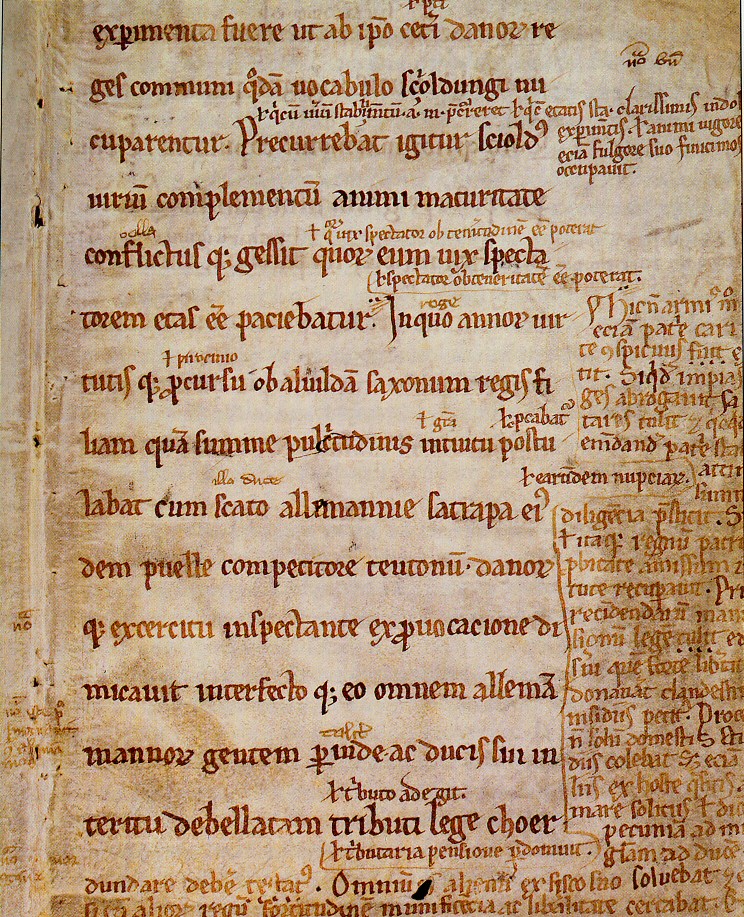

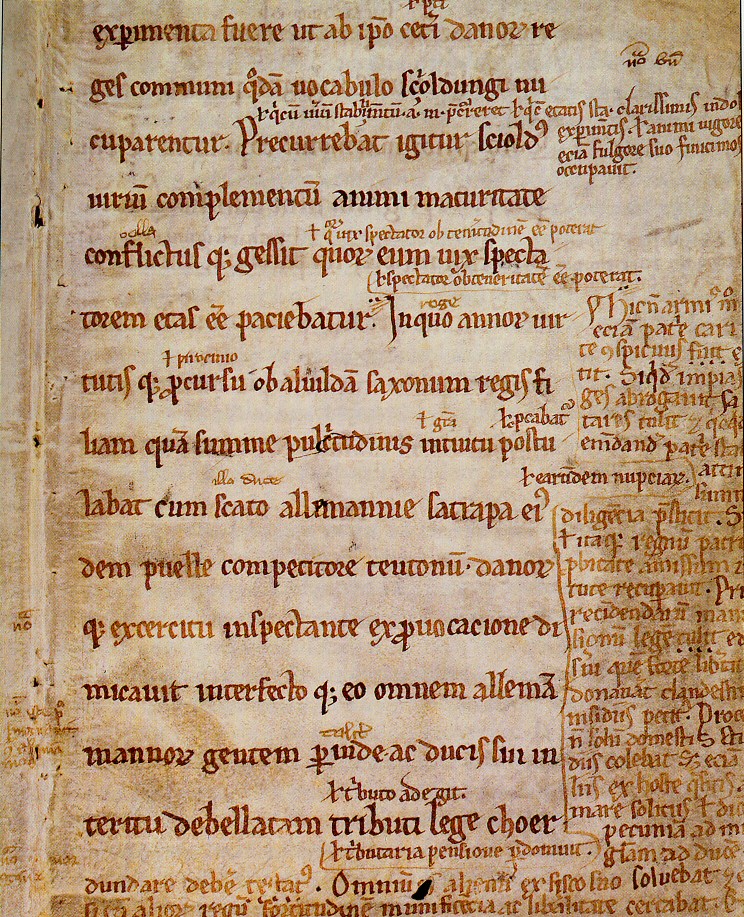

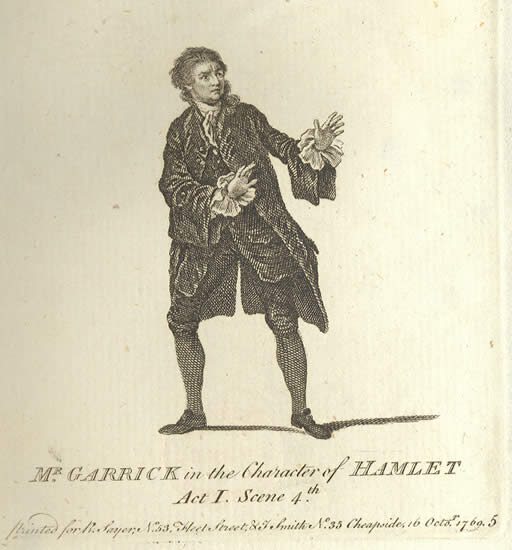

| Sources Main article: Sources of Hamlet  A facsimile of Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus, which contains the legend of Amleth Hamlet-like legends are so widely found (for example in Italy, Spain, Scandinavia, Byzantium, and Arabia) that the core "hero-as-fool" theme is possibly Indo-European in origin.[8] Several ancient written precursors to Hamlet can be identified. The first is the anonymous Scandinavian Saga of Hrolf Kraki. In this, the murdered king has two sons—Hroar and Helgi—who spend most of the story in disguise, under false names, rather than feigning madness, in a sequence of events that differs from Shakespeare's.[9] The second is the Roman legend of Brutus, recorded in two separate Latin works. Its hero, Lucius ("shining, light"), changes his name and persona to Brutus ("dull, stupid"), playing the role of a fool to avoid the fate of his father and brothers, and eventually slaying his family's killer, King Tarquinius. A 17th-century Nordic scholar, Torfaeus, compared the Icelandic hero Amlóði (Amlodi) and the hero Prince Ambales (from the Ambales Saga) to Shakespeare's Hamlet. Similarities include the prince's feigned madness, his accidental killing of the king's counsellor in his mother's bedroom, and the eventual slaying of his uncle.[10] Many of the earlier legendary elements are interwoven in the 13th-century "Life of Amleth" (Latin: Vita Amlethi) by Saxo Grammaticus, part of Gesta Danorum.[11] Written in Latin, it reflects classical Roman concepts of virtue and heroism, and was widely available in Shakespeare's day.[12] Significant parallels include the prince feigning madness, his mother's hasty marriage to the usurper, the prince killing a hidden spy, and the prince substituting the execution of two retainers for his own. A reasonably faithful version of Saxo's story was translated into French in 1570 by François de Belleforest, in his Histoires tragiques.[13] Belleforest embellished Saxo's text substantially, almost doubling its length, and introduced the hero's melancholy.[14] |

情報源 主な記事 ハムレットの出典  アムレト伝説を含むサクソ・グラマティコスによる『ゲスタ・ダノルム』の複製。 ハムレットに似た伝説は(イタリア、スペイン、スカンジナビア、ビザンチウム、アラビアなど)非常に広く見られるため、「愚か者としての英雄」というテー マの核心はインド・ヨーロッパ語起源である可能性がある[8]。ひとつは、スカンジナビアの無名の『Hrolf Krakiの武勇伝』(Saga of Hrolf Kraki)である。この物語では、殺された王には2人の息子-HroarとHelgi-がおり、彼らは物語の大半を、狂気を装うのではなく、偽名で変装 して過ごすという、シェイクスピアのものとは異なる一連の出来事が描かれている[9]。その主人公ルシウス(「輝く、光」)は、自分の名前と人格をブルー タス(「鈍い、愚かな」)に変え、父や兄弟の運命を避けるために愚か者の役を演じ、最終的には家族を殺したタルキニウス王を殺す。17世紀の北欧学者トル ファエウスは、アイスランドの英雄アムロジ(Amlóði)と英雄アンバレス王子(『アンバレス・サーガ』より)をシェイクスピアのハムレットになぞらえ た。類似点としては、王子が狂気を装っていること、母親の寝室で王の顧問官を誤って殺してしまうこと、最終的に叔父を殺害することなどが挙げられる [10]。 13世紀に書かれたサクソ・グラマティコスによる『アムレスの生涯』(ラテン語:Vita Amlethi)は、『ゲスタ・ダノーラム』(Gesta Danorum)の一部である[11]。ラテン語で書かれたこの作品は、美徳とヒロイズムに関する古典ローマの概念を反映しており、シェイクスピアの時代 には広く読まれていた。 [12] 重要な類似点としては、王子が狂気を装うこと、母親が簒奪者と急いで結婚すること、王子が隠れたスパイを殺すこと、王子が2人の家来の処刑を自分の処刑に 代えることなどが挙げられる。ベルフォレストはサクソのテキストを大幅に装飾し、長さをほぼ倍増させ、主人公の憂鬱を導入した[14]。 |

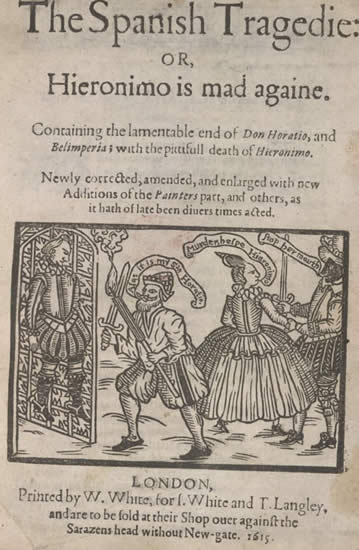

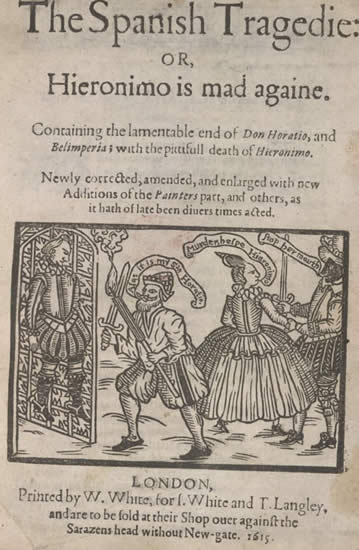

Title page of The Spanish Tragedy by Thomas Kyd According to one theory, Shakespeare's main source may be an earlier play—now lost—known today as the Ur-Hamlet. Possibly written by Thomas Kyd or by Shakespeare, the Ur-Hamlet would have existed by 1589, and would have incorporated a ghost.[15] Shakespeare's company, the Chamberlain's Men, may have purchased that play and performed a version for some time, which Shakespeare reworked.[16] However, no copy of the Ur-Hamlet has survived, and it is impossible to compare its language and style with the known works of any of its putative authors. In 1936 Andrew Cairncross suggested that, until more becomes known, it may be assumed that Shakespeare wrote the Ur-Hamlet.[17] Eric Sams lists reasons for supporting Shakespeare's authorship.[18] Harold Jenkins considers that there are no grounds for thinking that the Ur-Hamlet is an early work by Shakespeare, which he then rewrote.[19] Professor Terri Bourus in 2016, one of three general editors of the New Oxford Shakespeare,[20] in her paper "Enter Shakespeare's Young Hamlet, 1589" suggests that Shakespeare was "interested in sixteenth-century French literature, from the very beginning of his career" and therefore "did not need Thomas Kyd to pre-digest Belleforest's histoire of Amleth and spoon-feed it to him". She considers that the hypothesized Ur-Hamlet is Shakespeare's Q1 text, and that this derived directly from Belleforest's French version.[21] The precise combination of Shakespeare's use of the Ur-Hamlet, Belleforest, Saxo, or Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy as sources for Hamlet is not known. However, elements of Belleforest's version which are not in Saxo's story do appear in Shakespeare's play.[22] Most scholars reject the idea that Hamlet is in any way connected with Shakespeare's only son, Hamnet Shakespeare, who died in 1596 at age eleven. Conventional wisdom holds that Hamlet is strongly connected to legend, and the name Hamnet was quite popular at the time.[23] However, Stephen Greenblatt has argued that the coincidence of the names and Shakespeare's grief for the loss of his son may lie at the heart of the tragedy. He notes that the name of Hamnet Sadler, the Stratford neighbour after whom Hamnet was named, was often written as Hamlet Sadler and that, in the loose orthography of the time, the names were virtually interchangeable.[24][25] Scholars have often speculated that Hamlet's Polonius might have been inspired by William Cecil (Lord Burghley)—Lord High Treasurer and chief counsellor to Queen Elizabeth I. E. K. Chambers suggested Polonius's advice to Laertes may have echoed Burghley's to his son Robert Cecil.[26] John Dover Wilson thought it almost certain that the figure of Polonius caricatured Burghley.[27] A. L. Rowse speculated that Polonius's tedious verbosity might have resembled Burghley's.[28] Lilian Winstanley thought the name Corambis (in the First Quarto) did suggest Cecil and Burghley.[29] Harold Jenkins considers the idea of Polonius as a caricature of Burghley to be conjecture, perhaps based on the similar role they each played at court, and perhaps also based on the similarity between Burghley addressing his Ten Precepts to his son, and Polonius offering "precepts" to his son, Laertes.[30] Jenkins suggests that any personal satire may be found in the name "Polonius", which might point to a Polish or Polonian connection.[31] G. R. Hibbard hypothesised that differences in names (Corambis/Polonius:Montano/Raynoldo) between the First Quarto and other editions might reflect a desire not to offend scholars at Oxford University. (Robert Pullen, was the founder of Oxford University, and John Rainolds, was the President of Corpus Christi College.)[32] |

トマス・カイド作『スペインの悲劇』のタイトルページ 一説によると、シェイクスピアの主な出典は、現在では失われてしまったが、『ウル=ハムレット』として知られる以前の戯曲かもしれない。シェイクスピアの 劇団「チェンバレンズ・メン」がこの戯曲を購入し、しばらくの間上演し、シェイクスピアはそれを手直ししたのかもしれない[16]。しかし、「ウル=ハム レット」のコピーは現存しておらず、その言語や文体を作者とされる人物の既知の作品と比較することは不可能である。1936年、アンドリュー・ケインクロ スは、より多くのことが判明するまでは、シェイクスピアが『ウル=ハムレット』を書いたと仮定してもよいと示唆した[17]。 エリック・サムズは、シェイクスピアの作者であることを支持する理由を挙げている[18]。ハロルド・ジェンキンスは、『ウル=ハムレット』がシェイクス ピアの初期の作品で、その後シェイクスピアが書き直したと考える根拠はないと考えている。 [19] New Oxford Shakespeareの3人の総編集者の一人である2016年のテリー・ブルース教授[20]は、論文「Enter Shakespeare's Young Hamlet, 1589」の中で、シェイクスピアは「キャリアのごく初期から、16世紀のフランス文学に興味を持っていた」ため、「トマス・カイドがベルフォーレの『ア ムレトの歴史』を事前に消化し、彼に匙を投げる必要はなかった」と示唆している。彼女は、仮説上の『ウル=ハムレット』はシェイクスピアのQ1テキストで あり、これはベルフォレストのフランス語版から直接派生したものだと考えている[21]。 シェイクスピアが『ハムレット』の典拠として『ウル=ハムレット』、ベルフォレスト、サクソ、カイドの『スペインの悲劇』を用いた正確な組み合わせはわかっていない。しかし、サクソの物語にはないベルフォレスト版の要素がシェイクスピアの戯曲には登場している[22]。 ほとんどの学者は、ハムレットがシェイクスピアの一人息子であり、1596年に11歳で亡くなったハムネット・シェイクスピアと何らかの関係があるという 考えを否定している。従来の常識では、ハムレットは伝説と強く結びついており、ハムネットという名前は当時かなり人気があった[23]。しかし、スティー ヴン・グリーンブラットは、名前の一致と息子を失ったシェイクスピアの悲しみが悲劇の核心にあるのではないかと主張している。彼は、ハムネットの名前の由 来となったストラットフォードの隣人ハムネット・サドラーの名前はしばしばハムレット・サドラーと書かれ、当時のゆるい正書法では、この2つの名前は事実 上交換可能であったと指摘している[24][25]。 学者たちはしばしば、ハムレットのポローニアスはウィリアム・セシル(バーグリー卿)、つまりエリザベス1世の大蔵卿兼最高顧問にインスパイアされたので はないかと推測してきた。 [26] ジョン・ドーヴァー・ウィルソンは、ポローニアスの姿がバーグリーを戯画化したものであることはほぼ間違いないと考えた[27] A. L. ロウスは、ポローニアスの退屈な冗舌さがバーグリーに似ているのではないかと推測した[28] 。 [29]ハロルド・ジェンキンズは、ポローニアスがバーグリーを戯画化したものであるという考えは憶測に過ぎないと考えているが、それはおそらく二人が宮 廷で演じた役割が似ていることに基づくものであり、またバーグリーが「十戒」を息子に宛てていることと、ポローニアスが息子のラーテスに「訓戒」を授けて いることが似ていることにも基づいている。 [30] ジェンキンズは、「ポローニアス」という名前に人格風刺が含まれている可能性を示唆しており、これはポーランド人またはポロニア人とのつながりを示してい るのかもしれない[31]。G.R.ヒバードは、第1版と他の版で名前(コランビス/ポローニアス:モンターノ/レイノルド)が異なるのは、オックス フォード大学の学者を怒らせたくないという願望を反映しているのかもしれないという仮説を立てた。(ロバート・プーレンはオックスフォード大学の創設者で あり、ジョン・レイノルドはコーパス・クリスティ・カレッジの学長であった)[32]。 |

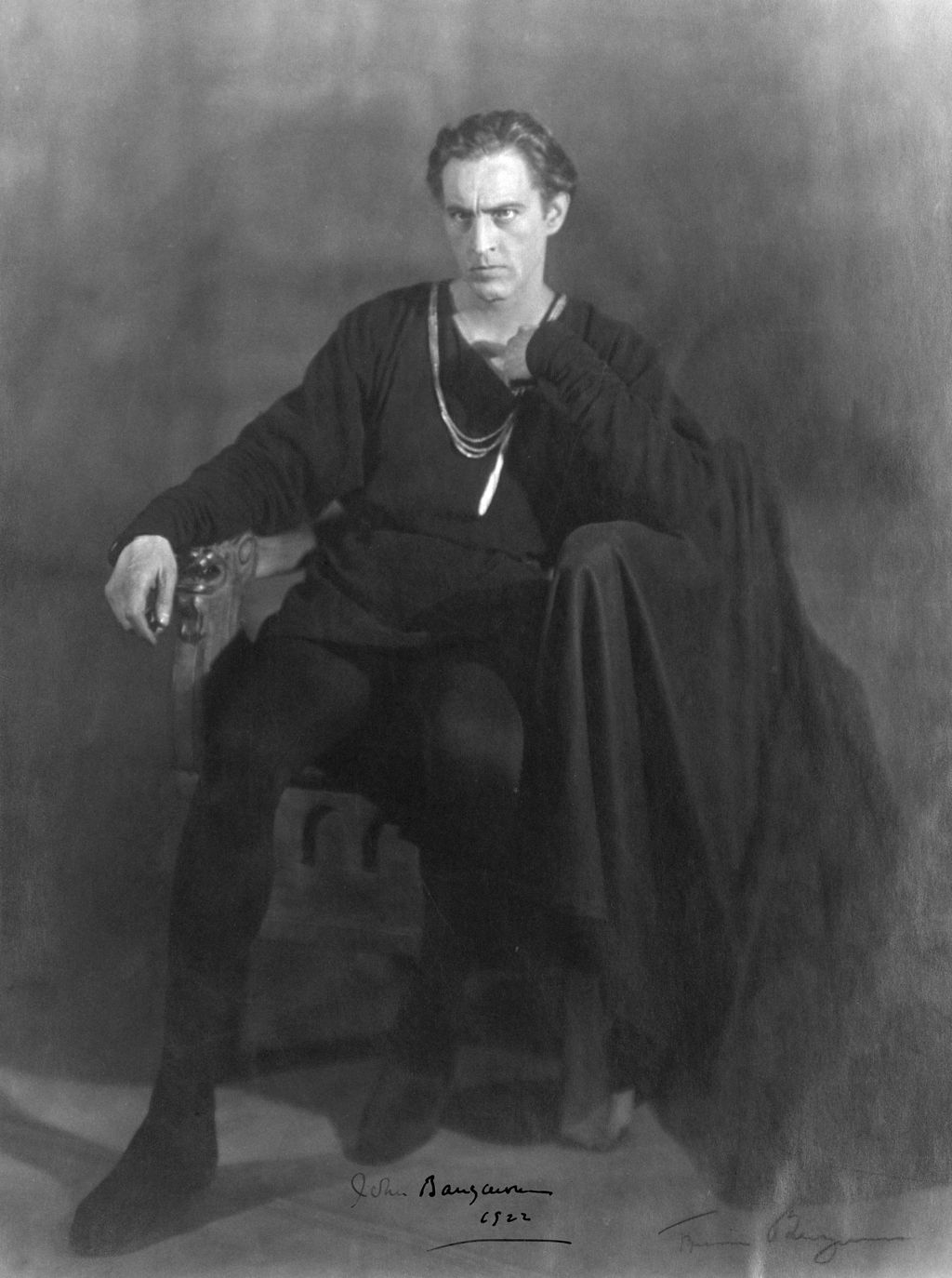

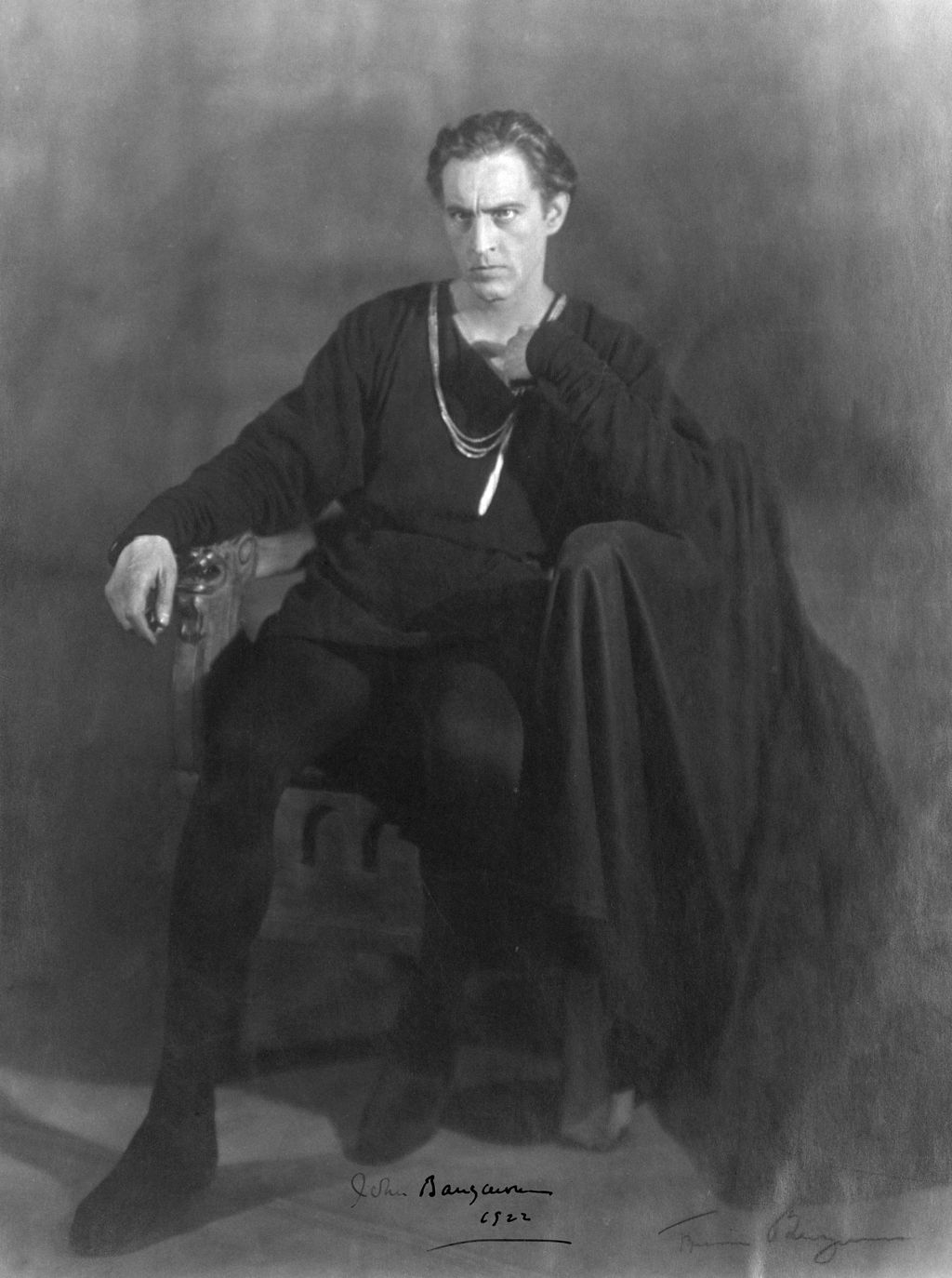

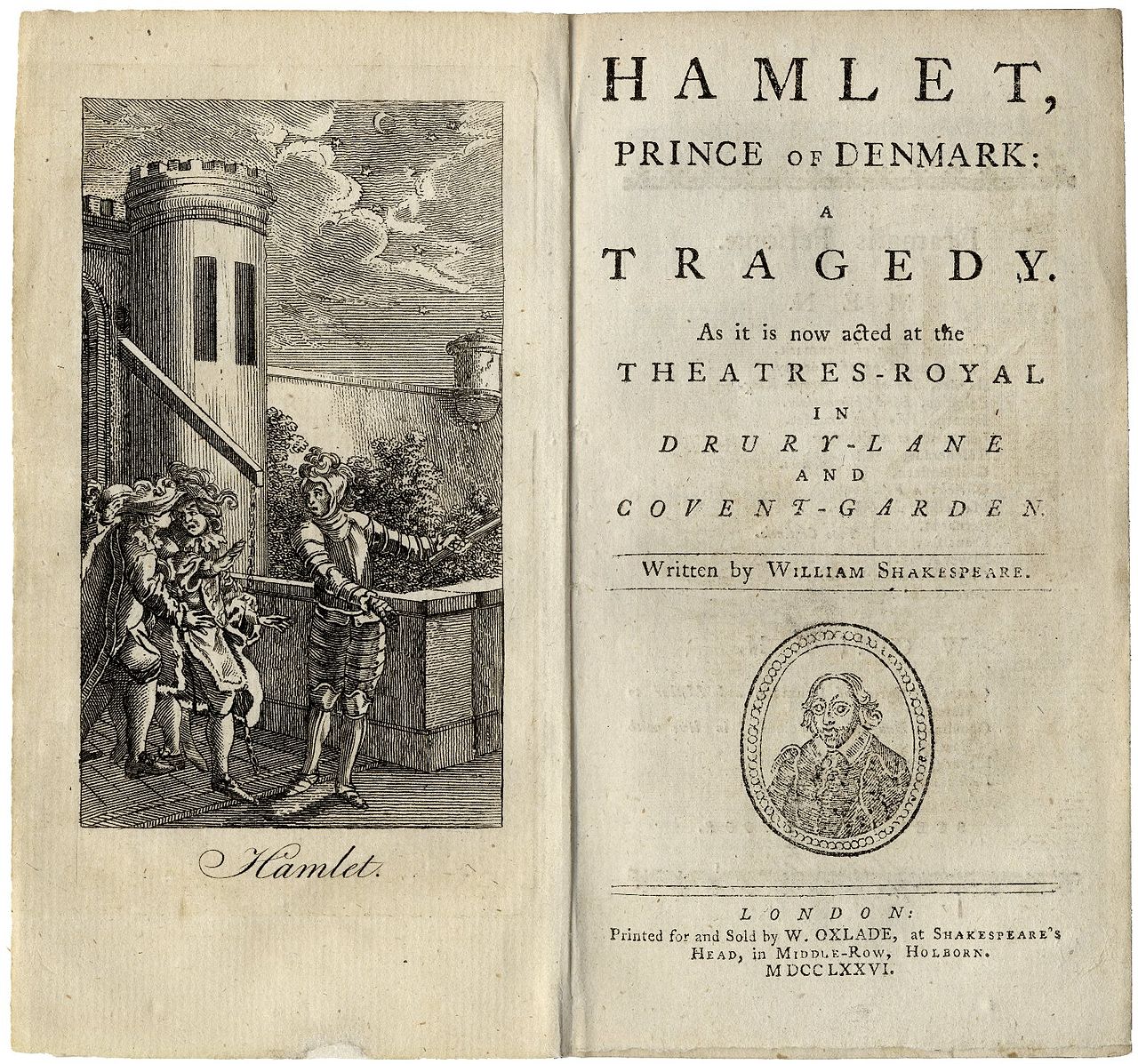

Date John Barrymore as Hamlet (1922) "Any dating of Hamlet must be tentative", states the New Cambridge editor, Phillip Edwards. MacCary suggests 1599 or 1600;[33] James Shapiro offers late 1600 or early 1601;[34] Wells and Taylor suggest that the play was written in 1600 and revised later;[35] the New Cambridge editor settles on mid-1601;[36] the New Swan Shakespeare Advanced Series editor agrees with 1601;[37] Thompson and Taylor, tentatively ("according to whether one is the more persuaded by Jenkins or by Honigmann") suggest a terminus ad quem of either Spring 1601 or sometime in 1600.[38] The earliest date estimate relies on Hamlet's frequent allusions to Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, itself dated to mid-1599.[39][40] The latest date estimate is based on an entry, of 26 July 1602, in the Register of the Stationers' Company, indicating that Hamlet was "latelie Acted by the Lo: Chamberleyne his servantes". In 1598, Francis Meres published his Palladis Tamia, a survey of English literature from Chaucer to its present day, within which twelve of Shakespeare's plays are named. Hamlet is not among them, suggesting that it had not yet been written. As Hamlet was very popular, Bernard Lott, the series editor of New Swan, believes it "unlikely that he [Meres] would have overlooked ... so significant a piece".[37] The phrase "little eyases"[41] in the First Folio (F1) may allude to the Children of the Chapel, whose popularity in London forced the Globe company into provincial touring.[42] This became known as the War of the Theatres, and supports a 1601 dating.[37] Katherine Duncan-Jones accepts a 1600–01 attribution for the date Hamlet was written, but notes that the Lord Chamberlain's Men, playing Hamlet in the 3000-capacity Globe, were unlikely to be put to any disadvantage by an audience of "barely one hundred" for the Children of the chapel's equivalent play, Antonio's Revenge; she believes that Shakespeare, confident in the superiority of his own work, was making a playful and charitable allusion to his friend John Marston's very similar piece.[43] A contemporary of Shakespeare's, Gabriel Harvey, wrote a marginal note in his copy of the 1598 edition of Chaucer's works, which some scholars use as dating evidence. Harvey's note says that "the wiser sort" enjoy Hamlet, and implies that the Earl of Essex—executed in February 1601 for rebellion—was still alive. Other scholars consider this inconclusive. Edwards, for example, concludes that the "sense of time is so confused in Harvey's note that it is really of little use in trying to date Hamlet". This is because the same note also refers to Spenser and Watson as if they were still alive ("our flourishing metricians"), but also mentions "Owen's new epigrams", published in 1607.[44] |

日付 ハムレット役ジョン・バリモア(1922年) ハムレット』の年代は暫定的なものでなければならない」とニュー・ケンブリッジの編集者フィリップ・エドワーズは述べている。MacCaryは1599年 か1600年、[33] James Shapiroは1600年後半か1601年前半、[34] WellsとTaylorは1600年に書かれ、その後改訂されたことを示唆、[35] New Cambridge editorは1601年半ば、[36] New Swan Shakespeare Advanced Series editorは1601年に同意、[37] ThompsonとTaylorは暫定的に(「JenkinsとHonigmannのどちらに説得されるかによって」)、1601年春か1600年のいつ か、という終着点を提案している。 [38] 最も早い時期の推定は、ハムレットがシェイクスピアの『ジュリアス・シーザー』を頻繁に引用していることに依拠している: Chamberleyne his servantes "とある。 1598年、フランシス・メレスは、チョーサーから現代までのイギリス文学を調査した『Palladis Tamia』を出版し、その中でシェイクスピアの戯曲12本の名前が挙げられている。ハムレットはその中に含まれておらず、まだ書かれていなかったことを 示唆している。ハムレット』は非常に人気があったため、『ニュー・スワン』のシリーズ・エディターであるバーナード・ロットは、「彼(メレス) が......これほど重要な作品を見落としたとは考えにくい」と考えている[37]。 ファースト・フォリオ(F1)の 「little eyases」[41]というフレーズは、ロンドンで人気を博したグローブ座を地方巡業に追いやった『チャペルの子供たち』[42]を暗示しているのかも しれない。 [37] キャサリン・ダンカン=ジョーンズは、『ハムレット』が書かれた時期について1600年から01年という推定を受け入れているが、3000人収容のグロー ブ座で『ハムレット』を演じる侍従長たちが、『礼拝堂の子供たち』に相当する『アントニオの復讐』の「かろうじて100人」の観客によって不利な立場に置 かれるとは考えにくいと指摘し、シェイクスピアは自身の作品の優位性に自信を持っており、友人ジョン・マーストンの非常によく似た作品に対して遊び心と慈 愛に満ちた暗示をかけたと考えている[43]。 シェイクスピアの同時代人であるガブリエル・ハーヴェイは、1598年版のチョーサー作品のコピーに余白を書き込んでおり、これを年代決定の証拠としてい る学者もいる。ハーヴェイの注によれば、「賢明な人々」はハムレットを楽しんでおり、1601年2月に謀反の罪で処刑されたエセックス伯爵がまだ生きてい たことを示唆している。他の学者たちは、これは決定的ではないと考えている。例えば、エドワーズは、「ハーヴェイのメモの時間感覚は非常に混乱しており、 ハムレットの年代を特定するにはほとんど役に立たない」と結論づけている。というのも、同じメモではスペンサーとワトソンがまだ生きているかのように言及 されており(「我々の繁栄する計量学者たち」)、1607年に出版された「オーウェンの新しいエピグラム」にも言及しているからである[44]。 |

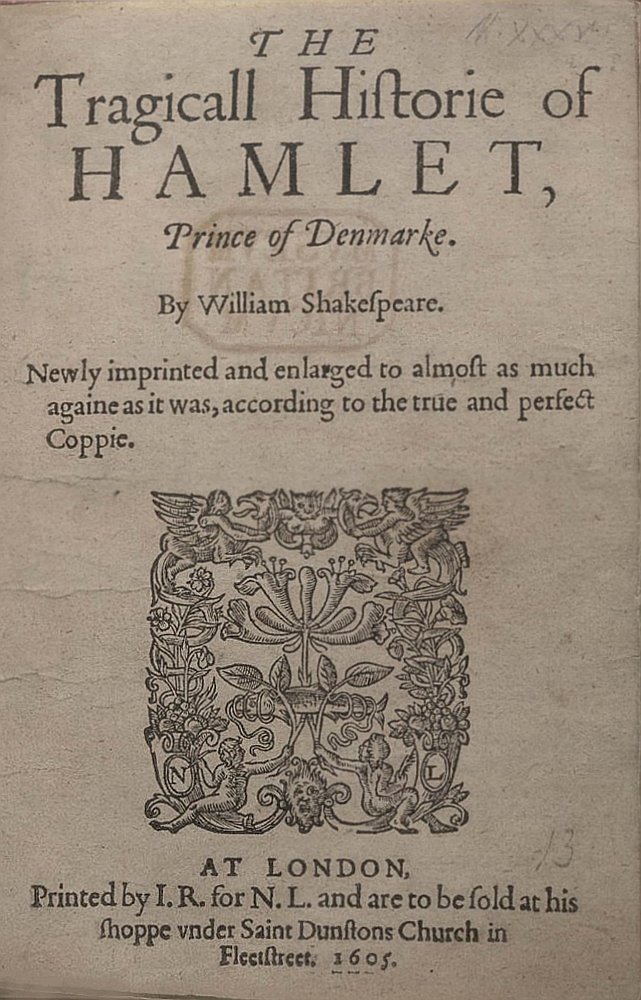

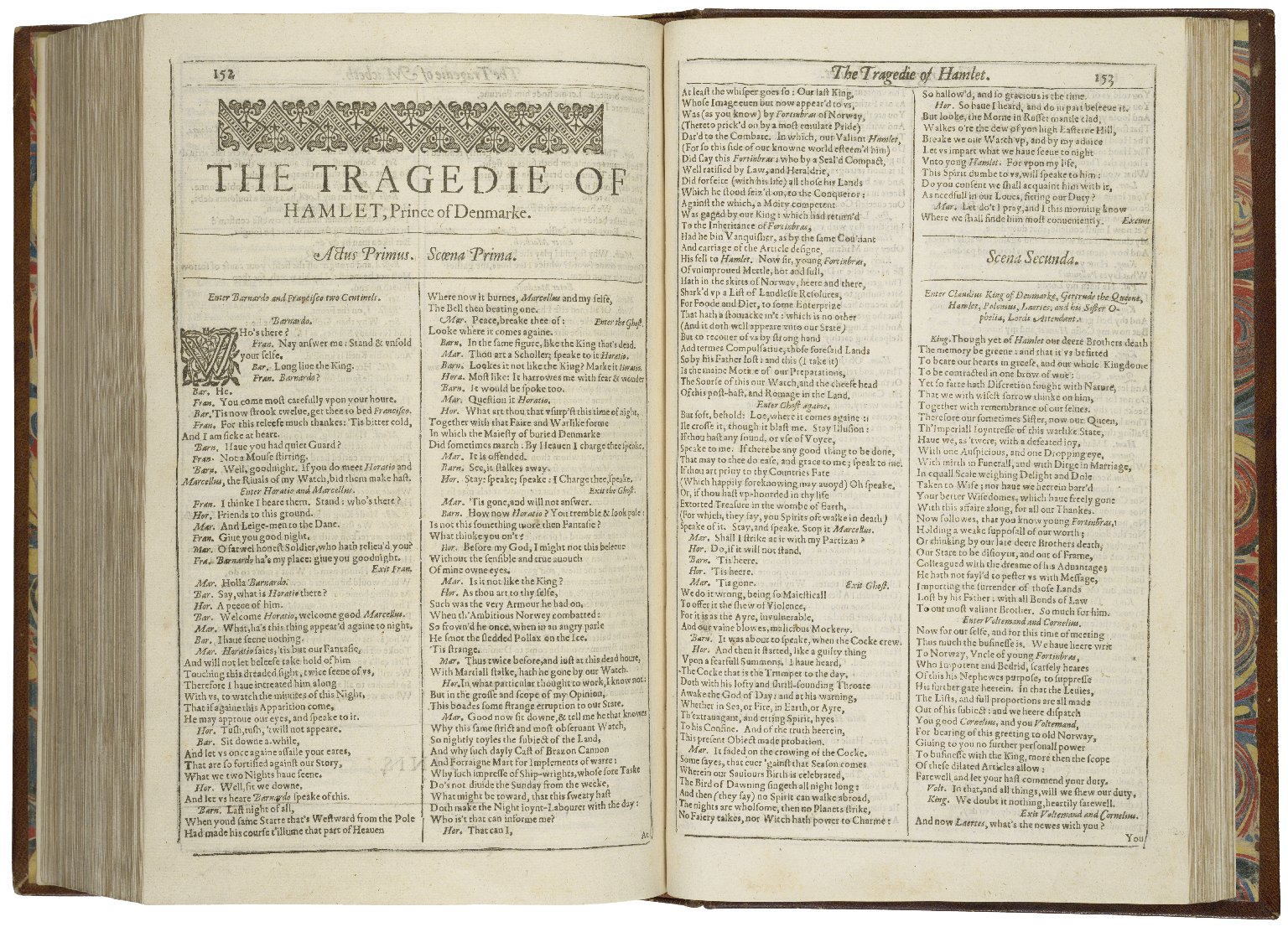

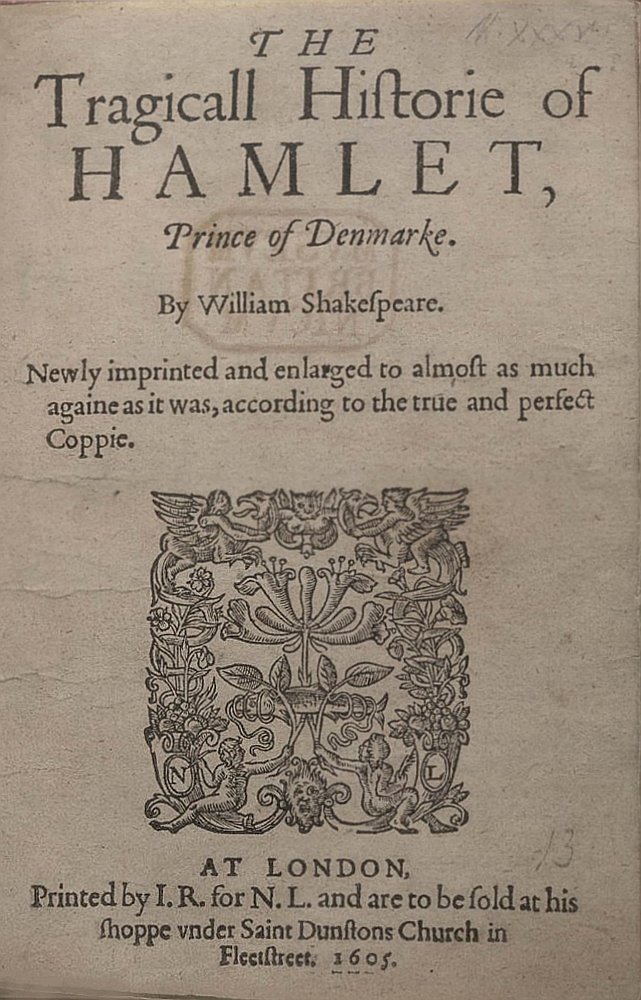

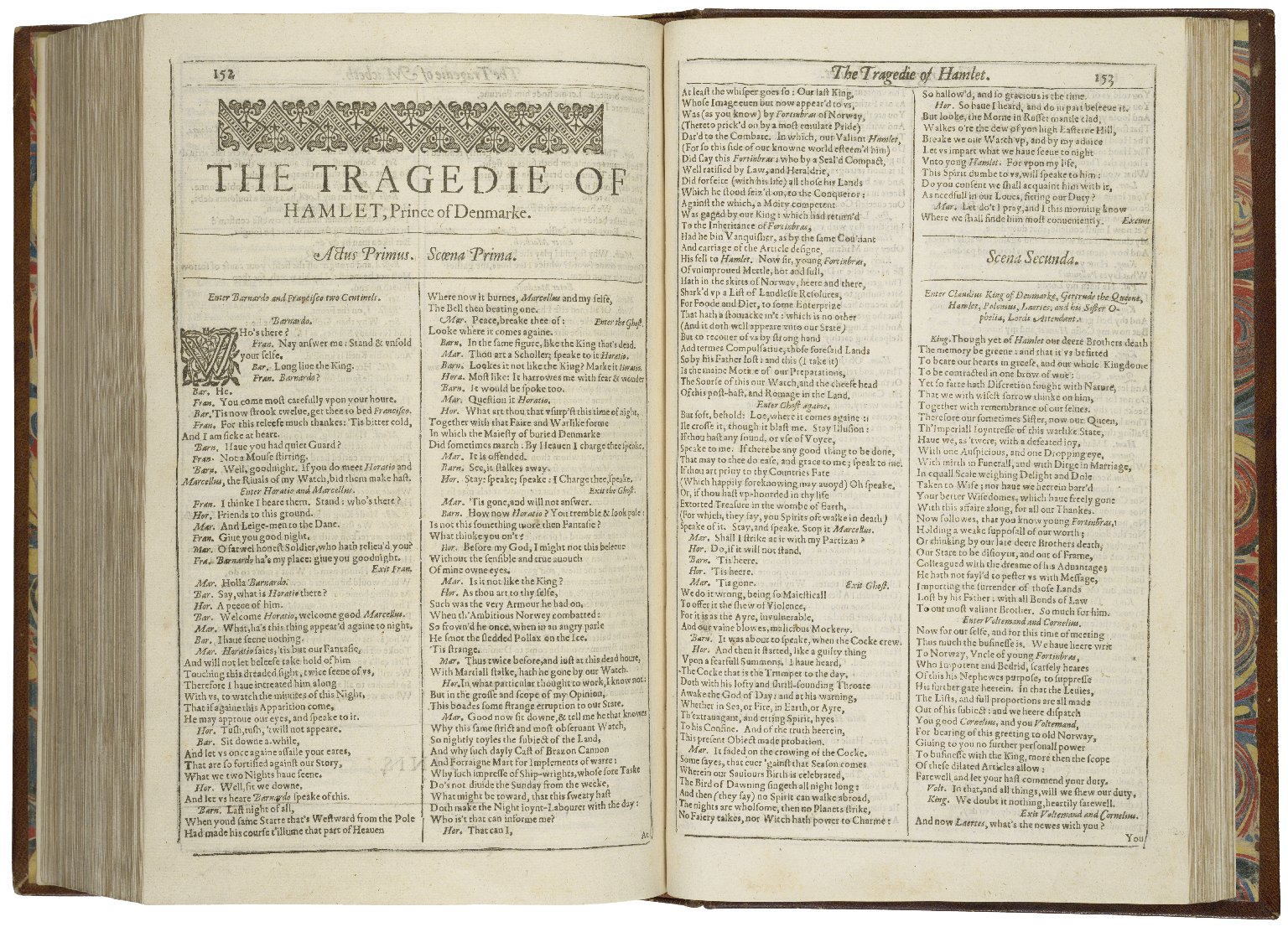

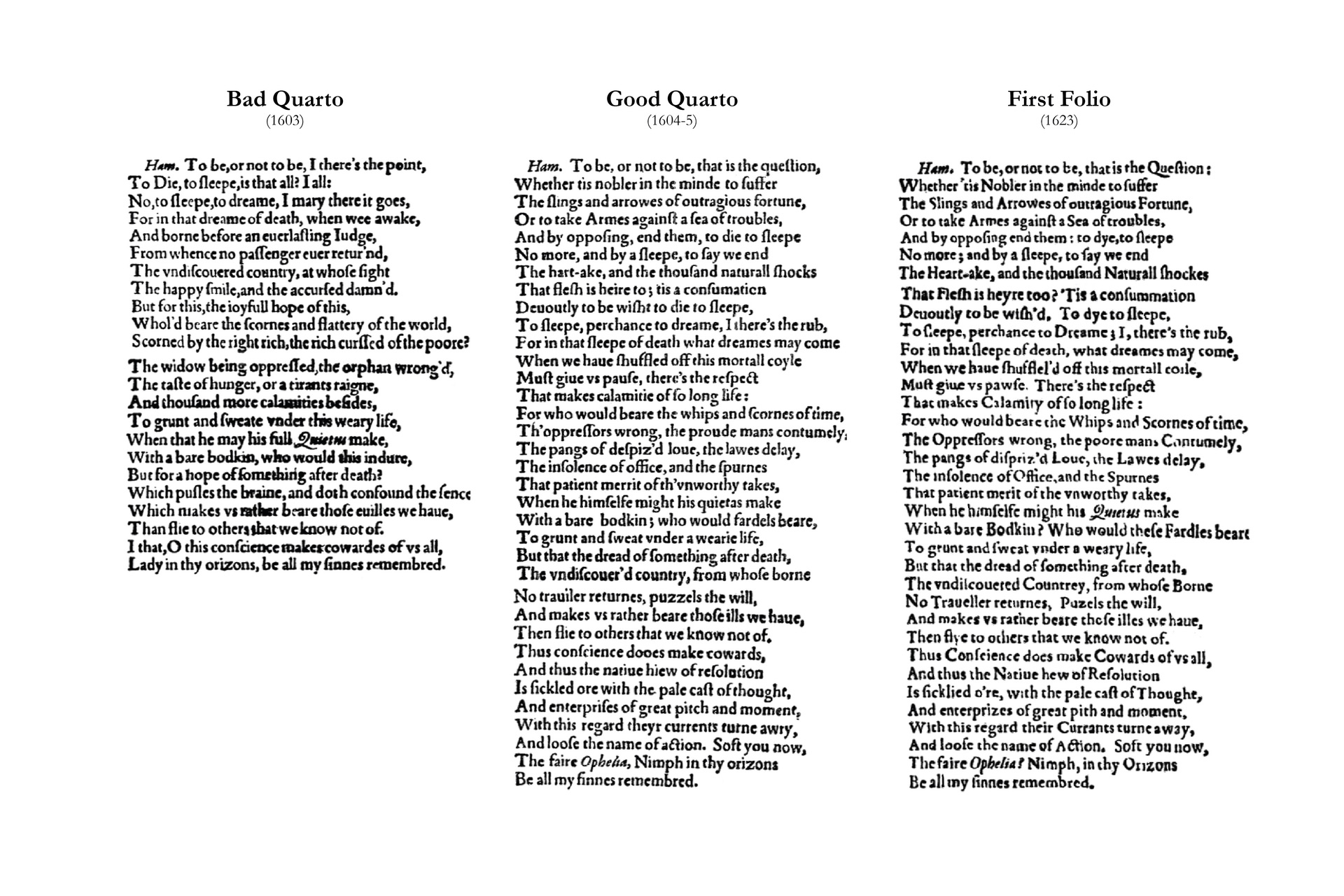

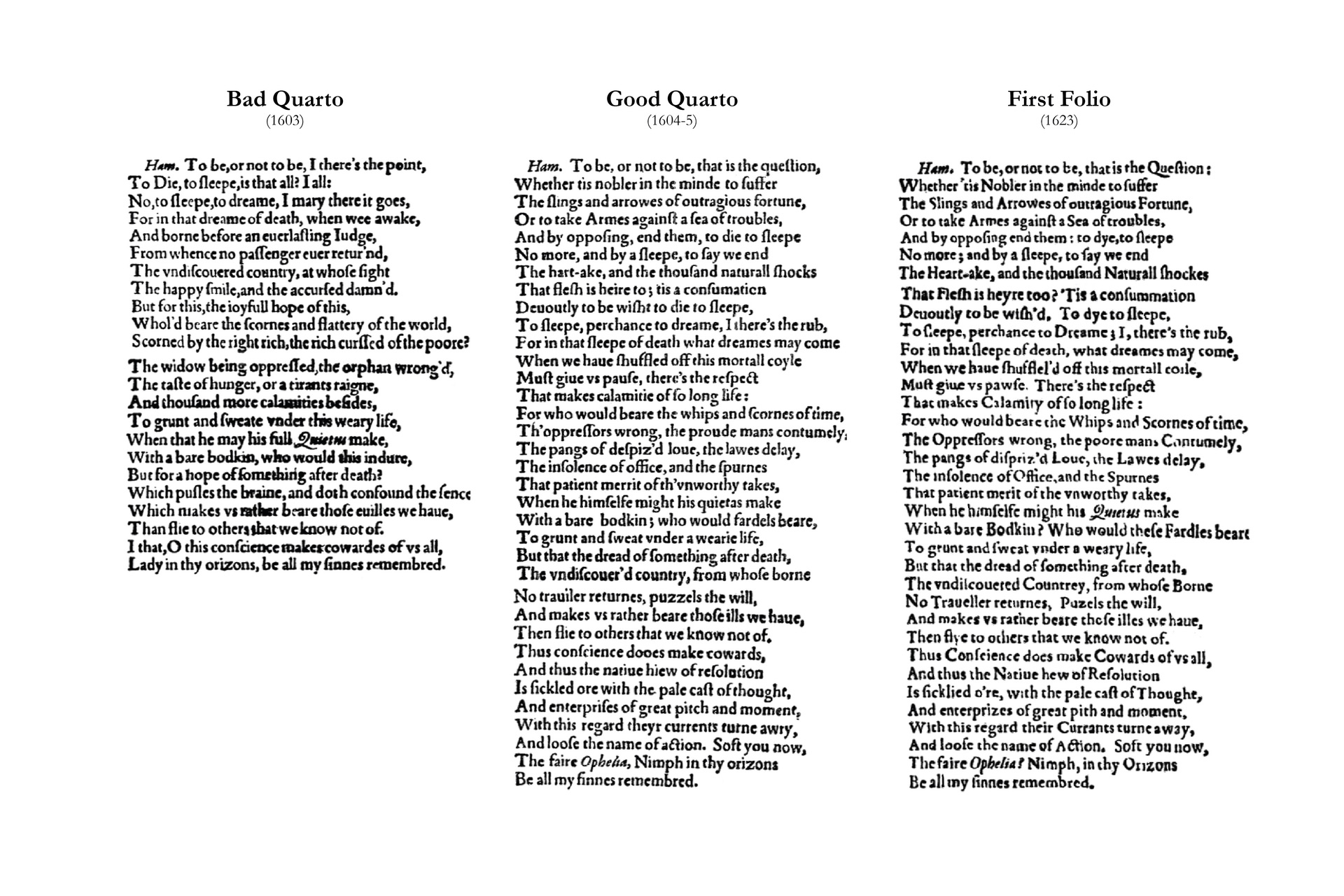

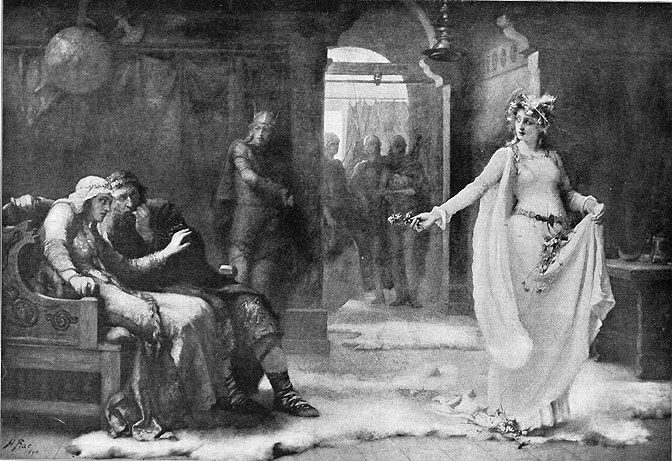

| Texts Three early editions of the text, each different, have survived, making attempts to establish a single "authentic" text problematic.[45][46][47] First Quarto (Q1): In 1603 the booksellers Nicholas Ling and John Trundell published, and Valentine Simmes printed, the so-called "bad" first quarto, under the name The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet Prince of Denmarke. Q1 contains just over half of the text of the later second quarto. Second Quarto (Q2): In 1604 Nicholas Ling published, and James Roberts printed, the second quarto, under the same name as the first. Some copies are dated 1605, which may indicate a second impression; consequently, Q2 is often dated "1604/5". Q2 is the longest early edition, although it omits about 77 lines found in F1[48] (most likely to avoid offending James I's queen, Anne of Denmark).[49] First Folio (F1): In 1623 Edward Blount and William and Isaac Jaggard published The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke in the First Folio, the first edition of Shakespeare's Complete Works.[50] This list does not include three additional early texts, John Smethwick's Q3, Q4, and Q5 (1611–37), which are regarded as reprints of Q2 with some alterations.[50]  Title page of the 1605 printing (Q2) of Hamlet  The first page of the First Folio printing of Hamlet, 1623 Early editors of Shakespeare's works, beginning with Nicholas Rowe (1709) and Lewis Theobald (1733), combined material from the two earliest sources of Hamlet available at the time, Q2 and F1. Each text contains material that the other lacks, with many minor differences in wording: scarcely 200 lines are identical in the two. Editors have combined them in an effort to create one "inclusive" text that reflects an imagined "ideal" of Shakespeare's original. Theobald's version became standard for a long time,[51] and his "full text" approach continues to influence editorial practice to the present day. Some contemporary scholarship, however, discounts this approach, instead considering "an authentic Hamlet an unrealisable ideal. ... there are texts of this play but no text".[52] The 2006 publication by Arden Shakespeare of different Hamlet texts in different volumes is perhaps evidence of this shifting focus and emphasis.[a] Other editors have continued to argue the need for well-edited editions taking material from all versions of the play. Colin Burrow has argued that most of us should read a text that is made up by conflating all three versions ... it's about as likely that Shakespeare wrote: "To be or not to be, ay, there's the point" [in Q1], as that he wrote the works of Francis Bacon. I suspect most people just won't want to read a three-text play ... [multi-text editions are] a version of the play that is out of touch with the needs of a wider public.[57] Traditionally, editors of Shakespeare's plays have divided them into five acts. None of the early texts of Hamlet, however, were arranged this way, and the play's division into acts and scenes derives from a 1676 quarto. Modern editors generally follow this traditional division but consider it unsatisfactory; for example, after Hamlet drags Polonius's body out of Gertrude's bedchamber, there is an act-break[58] after which the action appears to continue uninterrupted.[59] |

テキスト それぞれ異なる3つの初期版が現存しているため、単一の「真正」テキストを確立しようとする試みは問題になっている[45][46][47]。 第一版(Q1): 1603年、書店のニコラス・リングとジョン・トランデルが『The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet Prince of Denmarke(デンマークのハムレット王子の悲劇的な歴史)』という名で、いわゆる「悪い」第1四分冊を出版し、ヴァレンタイン・シムズが印刷した。 Q1には、後に出版される第2クォートのテキストの半分強が含まれている。 第二クオート(Q2): 1604年にニコラス・リングが出版し、ジェームズ・ロバーツが印刷した。一部の版には1605年という日付が入っているが、これは第2版であることを示 すもので、そのためQ2はしばしば 「1604/5 」と記されている。Q2は最も長い初期版であるが、F1に見られる約77行が省略されている[48](ジェームズ1世の王妃アン・オブ・デンマークの機嫌 を損ねないためと思われる)[49]。 ファースト・フォリオ(F1): 1623年、エドワード・ブラウントとウィリアム&アイザック・ジャガードはシェイクスピア全集の初版であるファースト・フォリオで『デンマークの王子ハムレットの悲劇』を出版した[50]。 このリストには、ジョン・スメスウィックのQ3、Q4、Q5(1611-37)という3つの初期のテキストは含まれていない。  ハムレット』1605年版(Q2)のタイトルページ  ハムレット』ファースト・フォリオの最初のページ(1623年 ニコラス・ロウ(Nicholas Rowe, 1709)とルイス・セオバルト(Lewis Theobald, 1733)に始まるシェイクスピア作品の初期の編集者たちは、当時入手可能であった『ハムレット』の2つの最も古い資料、Q2とF1の資料を組み合わせ た。それぞれのテキストには、もう一方のテキストに欠けている素材が含まれており、表現には多くの細かな差異がある。編集者たちは、シェイクスピアの原作 の「理想」を反映した「包括的」なテキストを作ろうとして、両者を組み合わせた。テオバードのバージョンは長い間標準となり[51]、彼の「全文」アプ ローチは現在に至るまで編集実務に影響を与え続けている。しかし、現代の学者の中にはこのアプローチを否定し、「本物のハムレットは実現不可能な理想であ る」と考える者もいる。2006年にアーデン・シェイクスピア社から出版された『ハムレット』の異なるテクストを異なる巻数で出版したことは、おそらくこ の焦点と重点の移行の証拠であろう[a]。他の編集者は、戯曲のすべての版から素材を取り入れた、よく編集された版の必要性を主張し続けている。コリン・ バローは次のように主張している。 シェイクスピアは、フランシス・ベーコンの著作を書いたのと同じように、「To be or not to be, ay, there's the point」 [Q1]を書いた可能性が高い。ほとんどの人は、3つのテキストからなる戯曲を読みたくはないだろう......。[複数テクスト版は)より広い大衆の ニーズとはかけ離れた戯曲の版である」[57]。 伝統的に、シェイクスピア戯曲の編集者は戯曲を5幕に分けている。しかし、『ハムレット』の初期のテキストはどれもこのような配置にはなっておらず、この 戯曲の幕と場面の分割は1676年の四分冊に由来する。例えば、ハムレットがガートルードの寝室からポローニアスの死体を引きずり出した後、幕切れ [58]があり、その後、行動は途切れることなく続いているように見える[59]。 |

Comparison of the 'To be, or not to be' soliloquy in the first three editions of Hamlet, showing the varying quality of the text in the Bad Quarto, the Good Quarto and the First Folio Q1 was discovered in 1823. Only two copies are extant. According to Jenkins, "The unauthorized nature of this quarto is matched by the corruption of its text."[60] Yet Q1 has value: it contains stage directions (such as Ophelia entering with a lute and her hair down) that reveal actual stage practices in a way that Q2 and F1 do not; it contains an entire scene (usually labelled 4.6)[61] that does not appear in either Q2 or F1; and it is useful for comparison with the later editions. The major deficiency of Q1 is in the language: particularly noticeable in the opening lines of the famous "To be, or not to be" soliloquy: "To be, or not to be, aye there's the point. / To die, to sleep, is that all? Aye all: / No, to sleep, to dream, aye marry there it goes." However, the scene order is more coherent, without the problems of Q2 and F1 of Hamlet seeming to resolve something in one scene and enter the next drowning in indecision. New Cambridge editor Kathleen Irace has noted that "Q1's more linear plot design is certainly easier [...] to follow [...] but the simplicity of the Q1 plot arrangement eliminates the alternating plot elements that correspond to Hamlet's shifts in mood."[62] Q1 is considerably shorter than Q2 or F1 and may be a memorial reconstruction of the play as Shakespeare's company performed it, by an actor who played a minor role (most likely Marcellus).[63] Scholars disagree whether the reconstruction was pirated or authorised. It is suggested by Irace that Q1 is an abridged version intended especially for travelling productions, thus the question of length may be considered as separate from issues of poor textual quality.[56][64] Editing Q1 thus poses problems in whether or not to "correct" differences from Q2 and F. Irace, in her introduction to Q1, wrote that "I have avoided as many other alterations as possible, because the differences...are especially intriguing...I have recorded a selection of Q2/F readings in the collation." The idea that Q1 is not riddled with error but is instead eminently fit for the stage has led to at least 28 different Q1 productions since 1881.[65] Other productions have used the Q2 and Folio texts, but used Q1's running order, in particular moving the to be or not to be soliloquy earlier.[66] Developing this, some editors such as Jonathan Bate have argued that Q2 may represent "a 'reading' text as opposed to a 'performance' one" of Hamlet: an edition containing all of Shakespeare's material for the play for the pleasure of readers, so not representing the play as it would have been staged.[67][68] |

ハムレット』の最初の3つの版における「To be, or not to be」の独り言(モノローグ)の比較。Bad Quarto、Good Quarto、First Folioにおけるテキストの質の違いを示している。 Q1は1823年に発見された。現存するのは2部のみである。ジェンキンスによれば、「このクオートの非公認性は、そのテキストの腐敗と一致している」 [60]。しかし、Q1には価値がある。Q2やF1にはない、実際の舞台のやり方を明らかにする舞台演出(オフィーリアがリュートを持って髪を下ろして登 場するなど)が含まれていること、Q2にもF1にも登場しない場面全体(通常は4.6とラベル付けされている)[61]が含まれていること、後期の版との 比較に有用であることなどが挙げられる。Q1の主な欠点は言葉遣いにあり、特に有名な独り言 「To be, or not to be 」の冒頭で顕著である: 「あるべきか、ないべきか、そこがポイントだ。/ 死ぬこと、眠ること、それだけか?そうだ、すべてだ: / いや、眠ること、夢見ること、そうだ、結婚しよう。」 しかし、シーンの順序はより首尾一貫しており、ハムレットがあるシーンで何かを解決し、優柔不断に溺れて次のシーンに入るように見えるQ2やF1の問題は ない。新ケンブリッジ編集者のキャスリーン・アイレイスは、「Q1のプロット設計がより直線的であることは確かに[...]追いやすい[...]が、Q1 のプロット配置が単純であるため、ハムレットの気分の変化に対応するプロット要素の交替が消去法によって排除されている」と指摘している[62]。 Q1はQ2やF1よりもかなり短く、シェイクスピアの劇団が上演した際に、脇役(おそらくマーセラス)を演じた俳優によって再現された記念碑的な作品であ る可能性がある[63]。したがって、Q1の編集は、Q2やFとの相違を「修正」するかどうかという問題を提起している[56][64]。イレイスはQ1 の序文で、「相違が...特に興味をそそるので...他の改変はできるだけ避けた...照合にはQ2/Fの読みを選んで記録した 」と書いている。Q1は誤りに満ちているわけではなく、むしろ舞台に非常に適しているという考えから、1881年以降、少なくとも28の異なるQ1が上演 された[65]。他の上演ではQ2とフォリオのテキストが使用されたが、Q1の上演順序が使用され、個別主義では特にto be or not to beの独り言が前に移動された。 [66]これを発展させ、ジョナサン・ベイトのような一部の編集者は、Q2は『ハムレット』の「『上演』とは対照的な『読書』テキスト」、つまり読者の楽 しみのためにシェイクスピアの戯曲のための素材をすべて収録した版であり、上演されたであろう戯曲を表しているのではないと主張している[67] [68]。 |

| Analysis and criticism Main article: Critical approaches to Hamlet Critical history From the early 17th century, the play was famous for its ghost and vivid dramatisation of melancholy and insanity, leading to a procession of mad courtiers and ladies in Jacobean and Caroline drama.[69][70] Though it remained popular with mass audiences, late 17th-century Restoration critics saw Hamlet as primitive and disapproved of its lack of unity and decorum.[71][72] This view changed drastically in the 18th century, when critics regarded Hamlet as a hero—a pure, brilliant young man thrust into unfortunate circumstances.[73] By the mid-18th century, however, the advent of Gothic literature brought psychological and mystical readings, returning madness and the ghost to the forefront.[74] Not until the late 18th century did critics and performers begin to view Hamlet as confusing and inconsistent. Before then, he was either mad, or not; either a hero, or not; with no in-betweens.[75] These developments represented a fundamental change in literary criticism, which came to focus more on character and less on plot.[76] In the 18th century, one negative French review of Hamlet would be widely discussed for centuries, in particular in publications throughout the 19th and 20th century.[77][78][79][80][81][82][83] In 1768, Voltaire wrote a negative review of Hamlet, stating that "it is vulgar and barbarous drama, which would not be tolerated by the vilest populace of France or Italy... one would imagine this piece to be a work of a drunken savage",[84] while acknowledging that it contains "some sublime strokes worthy of the greatest genius".[85] By the 19th century, Romantic critics valued Hamlet for its internal, individual conflict reflecting the strong contemporary emphasis on internal struggles and inner character in general.[86] Then too, critics started to focus on Hamlet's delay as a character trait, rather than a plot device.[76] This focus on character and internal struggle continued into the 20th century, when criticism branched in several directions, discussed in context and interpretation below. |

分析と批判 主な記事 ハムレットへの批評的アプローチ 批評の歴史 17世紀初頭から、この戯曲は憂鬱と狂気を亡霊のように鮮やかに劇化したことで有名であり、ジャコビアン劇やカロライン劇では狂気の廷臣や貴婦人の行列が 描かれた。 [69][70]大衆の間では人気を保っていたものの、17世紀末の王政復古期の批評家たちはハムレットを原始的なものとみなし、その統一性と礼儀の欠如 を不承認とした[71][72]。この見方は18世紀になると大きく変わり、批評家たちはハムレットを不運な境遇に突き落とされた純粋で優秀な若者である 英雄とみなした[73]。 しかし、18世紀半ばになると、ゴシック文学の登場によって心理学的、神秘学的な解釈がもたらされ、狂気と幽霊が再び前面に押し出されるようになった [74]。それ以前は、ハムレットは狂気であるか、そうでないか、英雄であるか、そうでないか、その中間はなかった[75]。このような動きは文芸批評の 根本的な変化を意味し、文芸批評は人物像を重視し、筋書きを重視しなくなった[76]。 [1768年、ヴォルテールは『ハムレット』の否定的な批評を書き、「下品で野蛮な劇であり、フランスやイタリアの最も下劣な民衆には容認されないだろ う...この作品は酔っぱらった野蛮人の作品だと想像するだろう」と述べる一方で[84]、「最も偉大な天才にふさわしい崇高なストローク」が含まれてい ることは認めている[85]。 19世紀になると、ロマン派の批評家たちは『ハムレット』の内面的な葛藤を評価するようになり、内面的な葛藤や内面的な性格が一般的に重視されるようになった現代を反映している[86]。 |

| Dramatic structure Modern editors have divided the play into five acts, and each act into scenes. The First Folio marks the first two acts only. The quartos do not have such divisions. The division into five acts follows Seneca, who in his plays, regularized the way ancient Greek tragedies contain five episodes, which are separated by four choral odes. In Hamlet the development of the plot or the action are determined by the unfolding of Hamlet's character. The soliloquies do not interrupt the plot, instead they are highlights of each block of action. The plot is the developing revelation of Hamlet's view of what is "rotten in the state of Denmark." The action of the play is driven forward in dialogue; but in the soliloquies time and action stop, the meaning of action is questioned, fog of illusion is broached, and truths are exposed. The contrast between appearance and reality is a significant theme. Hamlet is presented with an image, and then interprets its deeper or darker meaning. Examples begin with Hamlet questioning the reality of the ghost. It continues with Hamlet's taking on an "antic disposition" in order to appear mad, though he is not. The contrast (appearance and reality) is also expressed in several "spying scenes": Act two begins with Polonius sending Reynaldo to spy on his son, Laertes. Claudius and Polonius spy on Ophelia as she meets with Hamlet. In act two, Claudius asks Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to spy on Hamlet. Similarly, the play-within-a-play is used by Hamlet to reveal his step-father's hidden nature. There is no subplot, but the play presents the affairs of the courtier Polonius, his daughter, Ophelia, and his son, Laertes—who variously deal with madness, love and the death of a father in ways that contrast with Hamlet's. The graveyard scene eases tension prior to the catastrophe, and, as Hamlet holds the skull, it is shown that Hamlet no longer fears damnation in the afterlife, and accepts that there is a "divinity that shapes our ends".[87] Hamlet's enquiring mind has been open to all kinds of ideas, but in act five he has decided on a plan, and in a dialogue with Horatio he seems to answer his two earlier soliloquies on suicide: "We defy augury. There is special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, 'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows aught, what is't to leave betimes."[88][89] |

ドラマの構造 現代の編集者は、この戯曲を5つの幕に分け、それぞれの幕を場面に分けている。ファースト・フォリオでは、最初の2幕のみが記されている。クワルトにはそ のような区分はない。5幕に分けるのはセネカに倣ったもので、セネカは戯曲の中で、古代ギリシア悲劇が5つのエピソードを持ち、それが4つのコラール・ オードで区切られるのを規則化した。ハムレット』では、プロットやアクションの展開はハムレットの性格の展開によって決定される。独り言は筋書きを中断す るものではなく、それぞれのアクションのハイライトである。筋書きとは、ハムレットが考える 「デンマークの腐った部分 」が明らかになることである。劇の行動は対話の中で進められるが、独り言の中では時間と行動が止まり、行動の意味が問われ、幻想の霧が打ち破られ、真実が 暴かれる。 外見と現実の対比は重要なテーマである。ハムレットはイメージを提示され、その深い意味や暗い意味を解釈する。その例は、ハムレットが幽霊の実在を疑うと ころから始まる。ハムレットが狂っていないにもかかわらず、狂っているように見せかけるために 「破天荒な気質 」を取ることに続く。この対比(外見と現実)は、いくつかの「スパイシーン」でも表現されている: 第2幕は、ポローニアスが息子のレールテスをスパイするためにレイナルドを送り込むところから始まる。クローディアスとポローニアスは、ハムレットと会う オフィーリアをスパイする。第2幕では、クローディアスがローゼンクランツとギルデンスターンにハムレットのスパイを依頼する。同様に、劇中劇はハムレッ トが義父の隠された本性を暴くために使われる。 サブプロットはないが、劇中では廷臣ポローニアス、その娘オフィーリア、息子レアテスが、ハムレットとは対照的な方法で狂気、愛、父の死とさまざまに向き 合う。墓場の場面は大惨事の前の緊張を和らげ、ハムレットが頭蓋骨を手にすることで、ハムレットがもはや死後の世界での天罰を恐れず、「私たちの終わりを 形作る神性」の存在を受け入れていることが示される[87]。 ハムレットの探究心はあらゆるアイデアに開かれていたが、第5幕で彼は計画を決定し、ホレイショとの対話の中で、自殺に関する先の2つの独り言に答えてい るように見える: 「予言には逆らえない。雀の落下には特別な摂理がある。今でなければ来ない。今でなければ来る。覚悟がすべてだ。人は何一つ残すものがないのだから、何時 何を残すべきか、何も知らないのである」[88][89]。 |

| Length The First Quarto (1603) text of Hamlet contains 15,983 words, the Second Quarto (1604) contains 28,628 words, and the First Folio (1623) contains 27,602 words. Counting the number of lines varies between editions, partly because prose sections in the play may be formatted with varied lengths.[90] Editions of Hamlet that are created by conflating the texts of the Second Quarto and the Folio are said to have approximately 3,900 lines;[91] the number of lines varies between those editions based on formatting the prose sections, counting methods, and how the editors have joined the texts together.[92] Hamlet is by far the longest play that Shakespeare wrote, and one of the longest plays in the Western canon. It might require more than four hours to stage;[93] a typical Elizabethan play would need two to three hours.[94] It is speculated that because of the considerable length of Q2 and F1, there was an expectation that those texts would be abridged for performance, or that Q2 and F1 may have been aimed at a reading audience.[95] That Q1 is so much shorter than Q2 has spurred speculation that Q1 is an early draft, or perhaps an adaptation, a bootleg copy, or a stage adaptation. On the title page of Q2, its text is described as "newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much again as it was." That is probably a comparison to Q1.[90] |

長さ ハムレット』の第1版(1603年)は15,983語、第2版(1604年)は28,628語、第1フォリオ(1623年)は27,602語である。行数 の数え方は版によって異なるが、これは劇中の散文部分の長さがまちまちなためである。 [ハムレット』はシェイクスピアが書いた戯曲の中で圧倒的に長く、西洋の正典の中でも最も長い戯曲の一つである。典型的なエリザベス朝時代の戯曲は2~3 時間を必要とする[93]。Q2とF1がかなり長いため、これらのテキストは上演のために要約されることが期待されていた、あるいはQ2とF1は朗読の聴 衆を対象としていたのではないかと推測されている[95]。 Q1がQ2よりも非常に短いことは、Q1が初期の草稿である、あるいはおそらく翻案、海賊版、舞台化であるとの憶測を呼んでいる。Q2のタイトル・ページ には、そのテキストが 「新たに打刻され、ほぼ元通りに拡大された 」と記述されている。これはおそらくQ1との比較であろう[90]。 |

Language Hamlet's statement that his dark clothes are the outer sign of his inner grief demonstrates strong rhetorical skill (artist: Eugène Delacroix 1834). Much of Hamlet's language is courtly: elaborate, witty discourse, as recommended by Baldassare Castiglione's 1528 etiquette guide, The Courtier. This work specifically advises royal retainers to amuse their masters with inventive language. Osric and Polonius, especially, seem to respect this injunction. Claudius's speech is rich with rhetorical figures—as is Hamlet's and, at times, Ophelia's—while the language of Horatio, the guards, and the gravediggers is simpler. Claudius's high status is reinforced by using the royal first person plural ("we" or "us"), and anaphora mixed with metaphor to resonate with Greek political speeches.[96] Of all the characters, Hamlet has the greatest rhetorical skill. He uses highly developed metaphors, stichomythia, and in nine memorable words deploys both anaphora and asyndeton: "to die: to sleep— / To sleep, perchance to dream".[97] In contrast, when occasion demands, he is precise and straightforward, as when he explains his inward emotion to his mother: "But I have that within which passes show, / These but the trappings and the suits of woe".[98] At times, he relies heavily on puns to express his true thoughts while simultaneously concealing them.[99] Pauline Kiernan argues that Shakespeare changed English drama forever in Hamlet because he "showed how a character's language can often be saying several things at once, and contradictory meanings at that, to reflect fragmented thoughts and disturbed feelings". She gives the example of Hamlet's advice to Ophelia, "get thee to a nunnery",[100] which, she claims, is simultaneously a reference to a place of chastity and a slang term for a brothel, reflecting Hamlet's confused feelings about female sexuality.[101] However Harold Jenkins does not agree, having studied the few examples that are used to support that idea, and finds that there is no support for the assumption that "nunnery" was used that way in slang, or that Hamlet intended such a meaning. The context of the scene suggests that a nunnery would not be a brothel, but instead a place of renunciation and a "sanctuary from marriage and from the world's contamination".[102] Thompson and Taylor consider the brothel idea incorrect considering that "Hamlet is trying to deter Ophelia from breeding".[103] Hamlet's first words in the play are a pun; when Claudius addresses him as "my cousin Hamlet, and my son", Hamlet says as an aside: "A little more than kin, and less than kind."[104] An unusual rhetorical device, hendiadys, appears in several places in the play. Examples are found in Ophelia's speech at the end of the nunnery scene: "Th'expectancy and rose of the fair state"[105] and "And I, of ladies most deject and wretched".[106] Many scholars have found it odd that Shakespeare would, seemingly arbitrarily, use this rhetorical form throughout the play. One explanation may be that Hamlet was written later in Shakespeare's life, when he was adept at matching rhetorical devices to characters and the plot. Linguist George T. Wright suggests that hendiadys had been used deliberately to heighten the play's sense of duality and dislocation.[107] Hamlet's soliloquies have captured the attention of scholars. Hamlet interrupts himself, vocalising either disgust or agreement with himself and embellishing his own words. He has difficulty expressing himself directly and instead blunts the thrust of his thought with wordplay. It is not until late in the play, after his experience with the pirates, that Hamlet is able to articulate his feelings freely.[108] |

言語 ハムレットが、黒い服は内なる悲しみの外面的な表れであると述べているのは、強い修辞的技巧を示している(画家:ウジェーヌ・ドラクロワ 1834年)。 ハムレットの言葉の多くは、バルダッサーレ・カスティリオーネが1528年に出版した礼儀作法書『廷臣』(The Courtier)が推奨するような、手の込んだ機知に富んだ言説である。この作品では特に、王室の家来たちに独創的な言葉で主人を楽しませるよう勧めて いる。特にオスリックとポローニアスは、この命令を尊重しているようだ。クローディアスの演説は、ハムレットや時にはオフィーリアの演説のように修辞的な 表現が豊富である。クローディアスの地位の高さは、王族の一人称複数形(「我々 」または 「我々」)を使うことで強化され、ギリシャの政治演説と共鳴するように隠喩とアナフォラが混ざっている[96]。 すべての登場人物の中で、ハムレットは最も優れた修辞的技巧を持っている。彼は高度に発達した隠喩、スティコミティアを使い、記憶に残る9つの言葉ではア ナフォラとアシンデトンの両方を展開している: 「死ぬこと:眠ること-/眠ること、ひょっとしたら夢を見ること」[97]。これとは対照的に、母親に対して自分の内なる感情を説明するときのように、い ざというときには正確で率直である: ポーリン・キアナンは、シェイクスピアは『ハムレット』において、「登場人物の言葉が、断片的な思考や乱れた感情を反映するために、しばしば一度に複数の こと、それも矛盾した意味を口にすることがあることを示した」ため、イギリス演劇を永遠に変えたと論じている[99]。彼女は、ハムレットがオフィーリア に「尼僧院に行け」と忠告する例[100]を挙げ、これは同時に貞節の場所への言及であると同時に売春宿の俗語であり、女性の性についてのハムレットの混 乱した感情を反映していると主張する[101]。 しかし、ハロルド・ジェンキンズは、その考えを支持するために使用される数少ない例を研究した結果、同意しておらず、「尼僧院」が俗語でそのように使用さ れていた、あるいはハムレットがそのような意味を意図していたという仮定には何の裏付けもないと見なしている。トンプソンとテイラーは、「ハムレットはオ フィーリアの繁殖を抑止しようとしている」[103]ことを考慮すると、売春宿という考えは正しくないと考えている。 ハムレットの劇中最初の言葉はダジャレであり、クローディアスが彼を「いとこのハムレット、そして息子」と呼ぶと、ハムレットは余談としてこう言う。 珍しい修辞法であるヘンジアディスは、劇中に何箇所か登場する。その例は、尼僧院の場面の最後のオフィーリアの台詞に見られる: 「多くの研究者は、シェイクスピアが戯曲全体を通して、一見恣意的にこの修辞形式を使うことを奇妙に思ってきた。一つの説明は、『ハムレット』がシェイク スピアの人生の後半に書かれ、登場人物や筋書きに修辞的な仕掛けを合わせることに長けていた時期だったからかもしれない。言語学者のジョージ・T・ライト は、ヘンジアディスは戯曲の二重性と転位の感覚を高めるために意図的に使われたと示唆している[107]。 ハムレットの独り言は学者たちの注目を集めてきた。ハムレットは自分の言葉を遮り、自分自身への嫌悪や同意を口にし、自分の言葉を装飾する。ハムレットは 自分自身を直接表現することが難しく、その代わりに言葉遊びで自分の考えの核心を鈍らせる。ハムレットが自分の感情を自由に表現できるようになるのは、劇 の後半、海賊との体験の後である[108]。 |

| Context and interpretation Religious  John Everett Millais' Ophelia (1852) depicts Lady Ophelia's mysterious death by drowning. In the play, the gravediggers discuss whether Ophelia's death was a suicide and whether she merits a Christian burial. Written at a time of religious upheaval and in the wake of the English Reformation, the play is alternately Catholic (or piously medieval) and Protestant (or consciously modern). The ghost describes himself as being in purgatory and as dying without last rites. This and Ophelia's burial ceremony, which is characteristically Catholic, make up most of the play's Catholic connections. Some scholars have observed that revenge tragedies come from Catholic countries such as Italy and Spain, where the revenge tragedies present contradictions of motives, since according to Catholic doctrine the duty to God and family precedes civil justice.[109] Much of the play's Protestant tones derive from its setting in Denmark—both then and now a predominantly Protestant country,[b] though it is unclear whether the fictional Denmark of the play is intended to portray this implicit fact. Dialogue refers explicitly to the German city of Wittenberg where Hamlet, Horatio, and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern attend university, implying where the Protestant reformer Martin Luther nailed the Ninety-five Theses to the church door in 1517.[110] |

文脈と解釈 宗教  ジョン・エヴァレット・ミレイの『オフィーリア』(1852年)は、オフィーリア夫人の謎めいた溺死を描いている。劇中、墓掘り人たちはオフィーリアの死が自殺であったかどうか、キリスト教式埋葬に値するかどうかを議論する。 宗教が激動し、イギリス宗教改革の後に書かれたこの戯曲は、カトリック(あるいは敬虔な中世)とプロテスタント(あるいは意識的な近代)が交互に描かれて いる。幽霊は自分自身を煉獄にいると表現し、最後の儀式を受けずに死ぬと表現する。これとオフィーリアの埋葬儀式が特徴的なカトリックであり、この劇のカ トリック的なつながりのほとんどを占めている。ある学者は、復讐悲劇はイタリアやスペインなどのカトリックの国から来たものであり、カトリックの教義によ れば、神や家族に対する義務が民事上の正義に優先するため、復讐悲劇は動機の矛盾を提示するものであると観察している[109]。 この劇のプロテスタント的色調の多くは、当時も現在もプロテスタントが多数を占めるデンマークを舞台にしていることに由来するが[b]、劇中の架空のデン マークがこの暗黙の事実を描くことを意図しているかどうかは不明である。対話では、ハムレット、ホレイショ、ローゼンクランツとギルデンスターンが大学に 通うドイツの都市ヴィッテンベルクについて明確に言及しており、プロテスタントの改革者マルティン・ルターが1517年に教会の扉に「九十五ヶ条の論題」 を釘で打ち付けた場所を暗示している[110]。 |

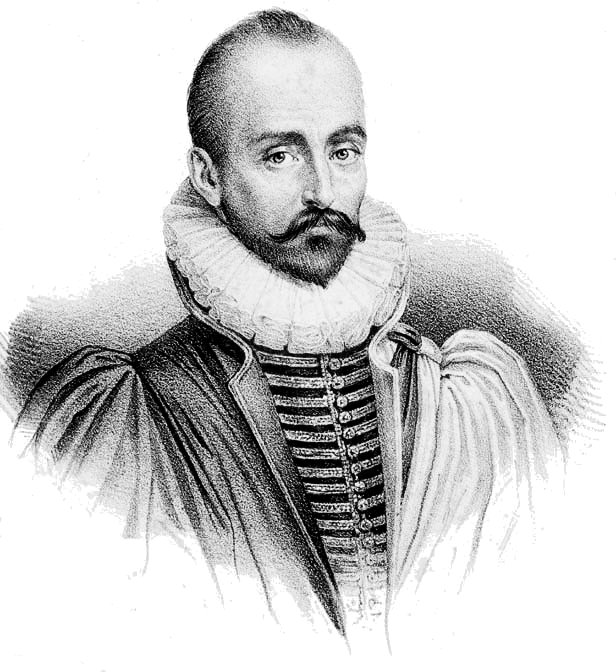

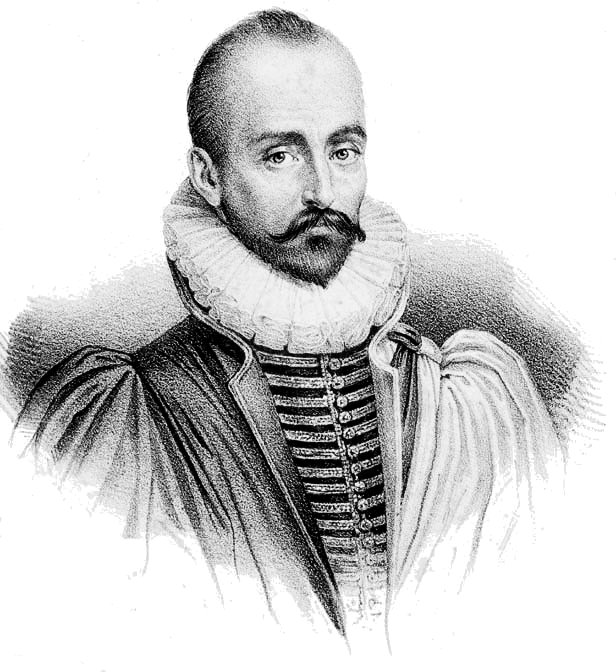

Philosophical Philosophical ideas in Hamlet are similar to those of the French writer Michel de Montaigne, a contemporary of Shakespeare's (artist: Thomas de Leu, fl. 1560–1612). Hamlet is often perceived as a philosophical character, expounding ideas that are now described as relativist, existentialist, and sceptical. For example, he expresses a subjectivistic idea when he says to Rosencrantz: "there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so".[111] The idea that nothing is real except in the mind of the individual finds its roots in the Greek Sophists, who argued that since nothing can be perceived except through the senses—and since all individuals sense, and therefore perceive things differently—there is no absolute truth, but rather only relative truth.[112] The clearest alleged instance of existentialism is in the "to be, or not to be"[113] speech, where Hamlet is thought by some to use "being" to allude to life and action, and "not being" to death and inaction. Hamlet reflects the contemporary scepticism promoted by the French Renaissance humanist Michel de Montaigne.[114] Prior to Montaigne's time, humanists such as Pico della Mirandola had argued that man was God's greatest creation, made in God's image and able to choose his own nature, but this view was subsequently challenged in Montaigne's Essais of 1580. Hamlet's "What a piece of work is a man" seems to echo many of Montaigne's ideas, and many scholars have discussed whether Shakespeare drew directly from Montaigne or whether both men were simply reacting similarly to the spirit of the times.[115][116][114] |

哲学的 ハムレット』に登場する哲学的思想は、シェイクスピアと同時代のフランスの作家ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュ(画家:トマ・ド・レウ、1560-1612年頃)の思想に似ている。 ハムレットはしばしば哲学的な人物として認識され、現在では相対主義的、実存主義的、懐疑的と評される思想を述べている。例えば、彼はローゼンクランツに 「良いことも悪いこともない。 [ハムレットは「あること」を生と行動を、「ないこと」を死と無為を暗示していると考える人もいる。 ハムレットは、フランス・ルネサンス期の人文主義者ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュが推進した現代の懐疑主義を反映している[114]。モンテーニュの時代以 前には、ピコ・デッラ・ミランドラのような人文主義者が、人間は神の最も偉大な被造物であり、神に似せて造られ、自らの本性を選択することができると主張 していたが、この見解はその後、1580年のモンテーニュのエッセで否定された。ハムレットの「人間とはなんという作品であろうか」という言葉は、モン テーニュの考え方の多くを反映しているように思われ、多くの学者がシェイクスピアがモンテーニュから直接引用したのか、それとも両者が単に時代の精神に同 じように反応しただけなのかを論じている[115][116][114]。 |

Psychoanalytic Freud suggested that an unconscious Oedipal conflict caused Hamlet's hesitations (artist: Eugène Delacroix 1844). Sigmund Freud Sigmund Freud’s thoughts regarding Hamlet were first published in his book The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), as a footnote to a discussion of Sophocles’ tragedy, Oedipus Rex, all of which is part of his consideration of the causes of neurosis. Freud does not offer over-all interpretations of the plays, but uses the two tragedies to illustrate and corroborate his psychological theories, which are based on his treatments of his patients and on his studies. Productions of Hamlet have used Freud's ideas to support their own interpretations.[117][118] In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud says that according to his experience "parents play a leading part in the infantile psychology of all persons who subsequently become psychoneurotics," and that "falling in love with one parent and hating the other" is a common impulse in early childhood, and is important source material of "subsequent neurosis". He says that "in their amorous or hostile attitude toward their parents" neurotics reveal something that occurs with less intensity "in the minds of the majority of children". Freud considered that Sophocles’ tragedy, Oedipus Rex, with its story that involves crimes of parricide and incest, "has furnished us with legendary matter which corroborates" these ideas, and that the "profound and universal validity of the old legends" is understandable only by recognizing the validity of these theories of "infantile psychology".[119] Freud explores the reason "Oedipus Rex is capable of moving a modern reader or playgoer no less powerfully than it moved the contemporary Greeks". He suggests that "It may be that we were all destined to direct our first sexual impulses toward our mothers, and our first impulses of hatred and violence toward our fathers." Freud suggests that we "recoil from the person for whom this primitive wish of our childhood has been fulfilled with all the force of the repression which these wishes have undergone in our minds since childhood."[119] These ideas, which became a cornerstone of Freud's psychological theories, he named the "Oedipus complex", and, at one point, he considered calling it the "Hamlet complex".[120] Freud considered that Hamlet "is rooted in the same soil as Oedipus Rex." But the difference in the "psychic life" of the two civilizations that produced each play, and the progress made over time of "repression in the emotional life of humanity" can be seen in the way the same material is handled by the two playwrights: In Oedipus Rex incest and murder are brought into the light as might occur in a dream, but in Hamlet these impulses "remain repressed" and we learn of their existence through Hamlet's inhibitions to act out the revenge, while he is shown to be capable of acting decisively and boldly in other contexts. Freud asserts, "The play is based on Hamlet’s hesitation in accomplishing the task of revenge assigned to him; the text does not give the cause or the motive of this." The conflict is "deeply hidden".[121] Hamlet is able to perform any kind of action except taking revenge on the man who murdered his father and has taken his father's place with his mother—Claudius has led Hamlet to realize the repressed desires of his own childhood. The loathing which was supposed to drive him to revenge is replaced by "self-reproach, by conscientious scruples" which tell him "he himself is no better than the murderer whom he is required to punish".[122] Freud suggests that Hamlet's sexual aversion expressed in his "nunnery" conversation with Ophelia supports the idea that Hamlet is "an hysterical subject".[122][123] Freud suggests that the character Hamlet goes through an experience that has three characteristics, which he numbered: 1) "the hero is not psychopathic, but becomes so" during the course of the play. 2) "the repressed desire is one of those that are similarly repressed in all of us." It is a repression that "belongs to an early stage of our individual development". The audience identifies with the character of Hamlet, because "we are victims of the same conflict." 3) It is the nature of theatre that "the struggle of the repressed impulse to become conscious" occurs in both the hero onstage and the spectator, when they are in the grip of their emotions, "in the manner seen in psychoanalytic treatment".[124] Freud points out that Hamlet is an exception in that psychopathic characters are usually ineffective in stage plays; they "become as useless for the stage as they are for life itself", because they do not inspire insight or empathy, unless the audience is familiar with the character's inner conflict. Freud says, "It is thus the task of the dramatist to transport us into the same illness."[125] John Barrymore's long-running 1922 performance in New York, directed by Thomas Hopkins, "broke new ground in its Freudian approach to character", in keeping with the post-World War I rebellion against everything Victorian.[126] He had a "blunter intention" than presenting the genteel, sweet prince of 19th-century tradition, imbuing his character with virility and lust.[127] Beginning in 1910, with the publication of "The Œdipus-Complex as an Explanation of Hamlet's Mystery: A Study in Motive"[128] Ernest Jones—a psychoanalyst and Freud's biographer—developed Freud's ideas into a series of essays that culminated in his book Hamlet and Oedipus (1949). Influenced by Jones's psychoanalytic approach, several productions have portrayed the "closet scene", where Hamlet confronts his mother in her private quarters, in a sexual light.[129] In this reading, Hamlet is disgusted by his mother's "incestuous" relationship with Claudius while simultaneously fearful of killing him, as this would clear Hamlet's path to his mother's bed. Ophelia's madness after her father's death may also be read through the Freudian lens: as a reaction to the death of her hoped-for lover, her father. Ophelia is overwhelmed by having her unfulfilled love for him so abruptly terminated and drifts into the oblivion of insanity.[130][131] In 1937, Tyrone Guthrie directed Laurence Olivier in a Jones-inspired Hamlet at The Old Vic.[132] Olivier later used some of these same ideas in his 1948 film version of the play. In the Bloom's Shakespeare Through the Ages volume on Hamlet, editors Bloom and Foster express a conviction that the intentions of Shakespeare in portraying the character of Hamlet in the play exceeded the capacity of the Freudian Oedipus complex to completely encompass the extent of characteristics depicted in Hamlet throughout the tragedy: "For once, Freud regressed in attempting to fasten the Oedipus Complex upon Hamlet: it will not stick, and merely showed that Freud did better than T.S. Eliot, who preferred Coriolanus to Hamlet, or so he said. Who can believe Eliot, when he exposes his own Hamlet Complex by declaring the play to be an aesthetic failure?"[133] The book also notes James Joyce's interpretation, stating that he "did far better in the Library Scene of Ulysses, where Stephen marvellously credits Shakespeare, in this play, with universal fatherhood while accurately implying that Hamlet is fatherless, thus opening a pragmatic gap between Shakespeare and Hamlet."[133] Joshua Rothman has written in The New Yorker that "we tell the story wrong when we say that Freud used the idea of the Oedipus complex to understand Hamlet". Rothman suggests that "it was the other way around: Hamlet helped Freud understand, and perhaps even invent, psychoanalysis". He concludes, "The Oedipus complex is a misnomer. It should be called the 'Hamlet complex'."[134] |

精神分析 フロイトは、無意識のエディプスの葛藤がハムレットの逡巡を引き起こしたと示唆した(画家:ウジェーヌ・ドラクロワ 1844年)。 ジークムント・フロイト ハムレットに関するジークムント・フロイトの考えは、彼の著書『夢の解釈』(1899年)の中で、ソフォクレスの悲劇『オイディプス王』の考察の脚注とし て初めて発表された。フロイトは戯曲の全体的な解釈を提示するのではなく、2つの悲劇を用いて、患者の治療と研究に基づく彼の心理学理論を説明し、裏付け をとっている。夢の解釈』の中でフロイトは、彼の経験によれば、「両親は、その後精神神経症になるすべての人格の幼児心理において主導的な役割を果たして いる」と述べ、「一方の親を愛し、他方の親を憎む」ことは幼児期によく見られる衝動であり、「その後の神経症」の重要な材料であると述べている。彼は、神 経症患者は「両親に対する愛情や敵対的な態度において」、「大多数の子供たちの心の中で」それほど強くはないが起こっていることを明らかにしていると言 う。フロイトは、ソフォクレスの悲劇である『オイディプス王』は、パリサイドと近親相姦の犯罪を含む物語であり、これらの考えを「裏付ける伝説的な事柄を 我々に与えてくれた」と考え、「古い伝説の深遠で普遍的な妥当性」は、これらの「幼児心理学」の理論の妥当性を認識することによってのみ理解できると考え た[119]。 フロイトは「『オイディプス王』は、現代の読者や観劇者を、現代のギリシア人を感動させたに劣らないほど強力に感動させることができる」理由を探ってい る。彼は「私たちは皆、最初の性的衝動を母親に向け、最初の憎悪と暴力の衝動を父親に向けるように運命づけられていたのかもしれない」と示唆する。フロイ トは、われわれは「幼少期のこの原始的な願望が満たされた人格に対して、幼少期以来、これらの願望が心の中で受けてきた抑圧の力を総動員して反発する」 [119]と示唆している。 フロイトはハムレットが 「エディプス・レックスと同じ土壌に根ざしている 」と考えた。しかし、それぞれの戯曲を生み出した2つの文明の「精神生活」の異なる点、そして「人類の感情生活における抑圧」の時代的な進歩は、2人の劇 作家による同じ素材の扱い方に見ることができる: オイディプス王』では近親相姦と殺人が夢の中で起こるように明るみに出されるが、『ハムレット』ではこれらの衝動は「抑圧されたまま」であり、私たちはハ ムレットが復讐を実行することを抑制することによってその存在を知る。フロイトは、「この戯曲は、ハムレットが自分に課せられた復讐の任務を遂行すること に躊躇していることに基づいている。」と断言している。その葛藤は「深く隠されている」[121]。 ハムレットは、父を殺し、父の身代わりとなって母を殺した男に復讐すること以外には、どんな行動もとることができる-クラウディウスはハムレットに、自身 の幼少期に抑圧された欲望を実現させた。フロイトは、ハムレットがオフィーリアとの「尼僧院」での会話で表現した性的嫌悪が、ハムレットが「ヒステリック な主体」であるという考えを裏付けていると示唆している[122][123]。 1)「主人公は精神病質者ではないが、そうなる」。2)「抑圧された欲望は、私たち全員に同様に抑圧されているものの一つである」。それは「個人の発達の 初期段階に属する」抑圧である。観客がハムレットのキャラクターに共感するのは、「私たちが同じ葛藤の犠牲者だから 」である。3) 「抑圧された衝動が意識化しようとする葛藤」が、舞台上の主人公にも観客にも、感情に支配されているときに、「精神分析的治療に見られるような仕方で」起 こるのが演劇の本質である[124]。 フロイトは、サイコパスの登場人物は通常、舞台劇では効果がないという点で、『ハムレット』は例外であると指摘している。彼らは「人生そのものであるのと 同様に、舞台にとっても役に立たない存在となる」。フロイトは、「このように、私たちを同じ病気の中に連れて行くことが劇作家の仕事である」と言う [125]。 1922年にニューヨークで上演されたジョン・バリモアのロングラン公演(トーマス・ホプキンス演出)は、第一次世界大戦後のヴィクトリア朝的なものすべ てに対する反抗と歩調を合わせ、「キャラクターに対するフロイト的なアプローチにおいて新境地を開いた」[126]。彼は、19世紀の伝統にある上品で甘 美な王子様を表現するよりも「露骨な意図」を持っており、彼のキャラクターに男らしさと欲望を吹き込んでいた[127]。 1910年に出版された『ハムレットの謎の説明としてのウディプス=コンプレックス』(The Œdipus-Complex as an Explanation of Hamlet's Mystery)から始まる[128]: 精神分析医でありフロイトの伝記作家でもあるアーネスト・ジョーンズは、フロイトの考えを一連のエッセイに発展させ、彼の著書『ハムレットとエディプス』 (1949年)に結実させた。ジョーンズの精神分析的アプローチに影響され、いくつかの作品では、ハムレットが母の私室で母と対峙する「クローゼットの場 面」が性的な観点から描かれている[129]。この読み方では、ハムレットはクローディアスと母の「近親相姦」関係に嫌悪感を抱くと同時に、クローディア スを殺すことを恐れている。父の死後のオフィーリアの狂気も、フロイトのレンズを通して読むことができる。オフィーリアは、父への叶わぬ愛を突然打ち切ら れたことに打ちひしがれ、狂気の忘却の彼方へと流れていく。 1937年、タイロン・ガスリーはローレンス・オリヴィエを演出し、オールド・ヴィックでジョーンズにインスパイアされた『ハムレット』を上演した [132]。 ハムレット』に関するブルームの『シェイクスピア・スルー・ザ・エイジズ』の中で、編者のブルームとフォスターは、劇中でハムレットのキャラクターを描く シェイクスピアの意図主義は、フロイトのエディプス・コンプレックスが、悲劇全体を通してハムレットに描かれた特徴の範囲を完全に包含する能力を超えてい るという確信を表明している。 S.エリオットはハムレットよりもコリオレイナスを好んだ。この戯曲を美学的に失敗作であると断言することで、彼自身のハムレット・コンプレックスを露呈 しているのだから、誰がエリオットを信じることができるだろうか」[133]。この本はまた、ジェイムズ・ジョイスの解釈にも言及しており、彼は「『ユリ シーズ』の図書館の場面では、スティーヴンがこの戯曲におけるシェイクスピアの普遍的な父性を見事に信用する一方で、ハムレットには父親がいないことを正 確に暗示し、その結果、シェイクスピアとハムレットの間に現実的な隔たりができた」と述べている[133]。 ジョシュア・ロスマンは『ニューヨーカー』誌に、「フロイトがハムレットを理解するためにエディプス・コンプレックスの考えを用いたと言うとき、私たちは その話を間違って伝えている」と書いている。ロスマンは、「ハムレットはフロイトを理解するのに役立った: ハムレットはフロイトが精神分析を理解し、おそらくは発明するのに役立ったのだ」。エディプス・コンプレックスは誤用である。ハムレット・コンプレック ス』と呼ぶべきだ」と結論づけている[134]。 |

| Jacques Lacan In the 1950s, the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan analyzed Hamlet to illustrate some of his concepts. His structuralist theories about Hamlet were first presented in a series of seminars given in Paris and later published in "Desire and the Interpretation of Desire in Hamlet". Lacan postulated that the human psyche is determined by structures of language and that the linguistic structures of Hamlet shed light on human desire.[135] His point of departure is Freud's Oedipal theories, and the central theme of mourning that runs through Hamlet.[136] In Lacan's analysis, Hamlet unconsciously assumes the role of phallus—the cause of his inaction—and is increasingly distanced from reality "by mourning, fantasy, narcissism and psychosis", which create holes (or lack) in the real, imaginary, and symbolic aspects of his psyche.[135] Lacan's theories influenced some subsequent literary criticism of Hamlet because of his alternative vision of the play and his use of semantics to explore the play's psychological landscape.[135] |

ジャック・ラカン 1950年代、フランスの精神分析学者ジャック・ラカンは、自身の概念のいくつかを説明するためにハムレットを分析した。ハムレットに関する彼の構造主義 理論は、パリで行われた一連のセミナーで初めて発表され、後に『ハムレットにおける欲望と欲望の解釈』として出版された。ラカンは、人間の精神は言語の構 造によって決定され、『ハムレット』の言語構造が人間の欲望に光を当てていると仮定した[135]。 [136]ラカンの分析では、ハムレットは無意識のうちにファルスの役割-彼の無為の原因-を引き受け、「喪、空想、ナルシシズム、精神病によって」現実 からますます遠ざかっていく。 |

Feminist Ophelia is distracted by grief.[137] Feminist critics have explored her descent into madness (artist: Henrietta Rae 1890). In the 20th century, feminist critics opened up new approaches to Gertrude and Ophelia. New historicist and cultural materialist critics examined the play in its historical context, attempting to piece together its original cultural environment.[138] They focused on the gender system of early modern England, pointing to the common trinity of maid, wife, or widow, with whores outside of that stereotype. In this analysis, the essence of Hamlet is the central character's changed perception of his mother as a whore because of her failure to remain faithful to Old Hamlet. In consequence, Hamlet loses his faith in all women, treating Ophelia as if she too were a whore and dishonest with Hamlet.[139]  Hamlet tries to show his mother Gertrude his father's ghost (artist: Nicolai A. Abildgaard, c. 1778). Carolyn Heilbrun's 1957 essay "The Character of Hamlet's Mother" defends Gertrude, arguing that the text never hints that Gertrude knew of Claudius poisoning King Hamlet. This analysis has been praised by many feminist critics, combating what is, by Heilbrun's argument, centuries' worth of misinterpretation. By this account, Gertrude's worst crime is of pragmatically marrying her brother-in-law in order to avoid a power vacuum. This is borne out by the fact that King Hamlet's ghost tells Hamlet to leave Gertrude out of Hamlet's revenge, to leave her to heaven, an arbitrary mercy to grant to a conspirator to murder.[140][141][142] Ophelia has also been defended by feminist critics, most notably Elaine Showalter.[143] Ophelia is surrounded by powerful men: her father, brother, and Hamlet. All three disappear: Laertes leaves, Hamlet abandons her, and Polonius dies. Conventional theories had argued that without these three powerful men making decisions for her, Ophelia is driven into madness.[144] Feminist theorists argue that she goes mad with guilt because, when Hamlet kills her father, he has fulfilled her sexual desire to have Hamlet kill her father so they can be together. Showalter points out that Ophelia has become the symbol of the distraught and hysterical woman in modern culture.[145] |

フェミニスト オフィーリアは悲しみに取り乱す[137]。フェミニスト批評家たちは、彼女の狂気への転落を探求してきた(画家:ヘンリエッタ・レー1890年)。 20世紀には、フェミニスト批評家たちがガートルードとオフィーリアへの新たなアプローチを切り開いた。新歴史主義的、文化的唯物論的な批評家たちは、こ の戯曲を歴史的文脈の中で検討し、その本来の文化的環境をつなぎ合わせようとした[138]。彼らは近世イングランドのジェンダー・システムに注目し、メ イド、妻、未亡人という一般的な三位一体、そしてそのステレオタイプから外れた娼婦を指摘した。この分析では、『ハムレット』の本質は、主人公が老ハム レットに誠実であり続けられなかったために、母親を娼婦として認識するようになったことにある。その結果、ハムレットはすべての女性に対する信頼を失い、 オフィーリアも娼婦でありハムレットに不誠実であるかのように扱う[139]。  ハムレットは母ガートルードに父の亡霊を見せようとする(画家:ニコライ・A・アビルドガード、1778年頃)。 キャロライン・ハイルブランの1957年のエッセイ『ハムレットの母の性格』はガートルードを擁護し、テキストはガートルードがクローディアスがハムレッ ト王に毒を盛ったことを知っていたことをほのめかしていないと論じている。この分析は多くのフェミニスト批評家たちから賞賛され、ハイルブランの議論によ れば、何世紀にもわたる誤った解釈に対抗するものである。この説明によれば、ガートルードの最悪の罪は、権力の空白を避けるために現実的に義弟と結婚した ことである。このことは、ハムレット王の亡霊がハムレットに、ガートルードをハムレットの復讐から外すように、天に任せるように、殺人の共謀者に与えるに は恣意的な慈悲であると告げていることからも裏付けられる[140][141][142]。 オフィーリアはまた、フェミニスト批評家、特にエレイン・ショウォルターによって擁護されている[143]。3人とも姿を消す: ラールテスは去り、ハムレットは彼女を見捨て、ポローニアスは死ぬ。従来の理論では、オフィーリアはこの3人の強力な男性に意思決定をしてもらわなけれ ば、狂気に追い込まれると論じられていた[144]。フェミニストの理論家は、ハムレットが父親を殺したとき、ハムレットに父親を殺してもらい、2人で一 緒になりたいという性的欲求が満たされたため、オフィーリアは罪悪感で狂ってしまったと主張する。ショウォルターは、オフィーリアが現代文化において取り 乱したヒステリックな女性の象徴になっていると指摘する[145]。 |

| Influence See also: Literary influence of Hamlet Hamlet is one of the most quoted works in the English language, and is often included on lists of the world's greatest literature.[c] As such, it reverberates through the writing of later centuries. Academic Laurie Osborne identifies the direct influence of Hamlet in numerous modern narratives, and divides them into four main categories: fictional accounts of the play's composition, simplifications of the story for young readers, stories expanding the role of one or more characters, and narratives featuring performances of the play.[147]  Actors before Hamlet by Władysław Czachórski (1875), National Museum in Warsaw English poet John Milton was an early admirer of Shakespeare and took evident inspiration from his work. As John Kerrigan discusses, Milton originally considered writing his epic poem Paradise Lost (1667) as a tragedy.[148] While Milton did not ultimately go that route, the poem still shows distinct echoes of Shakespearean revenge tragedy, and of Hamlet in particular. As scholar Christopher N. Warren argues, Paradise Lost's Satan "undergoes a transformation in the poem from a Hamlet-like avenger into a Claudius-like usurper," a plot device that supports Milton's larger Republican internationalist project.[149] The poem also reworks theatrical language from Hamlet, especially around the idea of "putting on" certain dispositions, as when Hamlet puts on "an antic disposition," similarly to the Son in Paradise Lost who "can put on / [God's] terrors."[150] Henry Fielding's Tom Jones, published about 1749, describes a visit to Hamlet by Tom Jones and Mr Partridge, with similarities to the "play within a play".[151] In contrast, Goethe's Bildungsroman Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship, written between 1776 and 1796, not only has a production of Hamlet at its core but also creates parallels between the ghost and Wilhelm Meister's dead father.[151] In the early 1850s, in Pierre, Herman Melville focuses on a Hamlet-like character's long development as a writer.[151] Ten years later, Dickens's Great Expectations contains many Hamlet-like plot elements: it is driven by revenge-motivated actions, contains ghost-like characters (Abel Magwitch and Miss Havisham), and focuses on the hero's guilt.[151] Academic Alexander Welsh notes that Great Expectations is an "autobiographical novel" and "anticipates psychoanalytic readings of Hamlet itself".[152] About the same time, George Eliot's The Mill on the Floss was published, introducing Maggie Tulliver "who is explicitly compared with Hamlet"[153] though "with a reputation for sanity".[154] In the 1920s, James Joyce managed "a more upbeat version" of Hamlet—stripped of obsession and revenge—in Ulysses, though its main parallels are with Homer's Odyssey.[151] In the 1990s, two novelists were explicitly influenced by Hamlet. In Angela Carter's Wise Children, To be or not to be is reworked as a song and dance routine, and Iris Murdoch's The Black Prince has Oedipal themes and murder intertwined with a love affair between a Hamlet-obsessed writer, Bradley Pearson, and the daughter of his rival.[153] In the late 20th century, David Foster Wallace's novel Infinite Jest draws heavily from Hamlet and takes its title from the play's text. There is the story of the woman who read Hamlet for the first time and said, "I don't see why people admire that play so. It is nothing but a bunch of quotations strung together." — Isaac Asimov, Asimov's Guide to Shakespeare, p. vii, Avenal Books, 1970 |

影響力 こちらも参照のこと: ハムレット』の文学的影響 ハムレット』は英語で最も引用される作品のひとつであり、世界の名作文学のリストにもしばしば名を連ねる[c]。学者であるローリー・オズボーンは、数多 くの現代の物語におけるハムレットの直接的な影響を特定し、それらを4つの主要なカテゴリーに分類している:戯曲の構成に関するフィクションの説明、若い 読者のための物語の単純化、1人または複数の登場人物の役割を拡大した物語、戯曲の上演を特徴とする物語である[147]。  ヴワディスワフ・チャチョルスキ作『ハムレットの前の俳優たち』(1875年)、ワルシャワ国民博物館蔵 イギリスの詩人ジョン・ミルトンは、早くからシェイクスピアを敬愛し、彼の作品から明らかなインスピレーションを得ていた。ジョン・ケリガンが論じている ように、ミルトンは当初、叙事詩『失楽園』(1667年)を悲劇として書くことを考えていた[148]。ミルトンは最終的にそのような路線には進まなかっ たものの、この詩にはシェイクスピアの復讐悲劇、特に『ハムレット』の明確な響きが残っている。学者クリストファー・N・ウォーレンが論じているように、 『失楽園』のサタンは「詩の中でハムレットのような復讐者からクローディアスのような簒奪者へと変貌を遂げる」のであり、これはミルトンのより大きな共和 主義的国際主義プロジェクトを支える筋立てである。 [149] この詩はまた『ハムレット』から演劇的な言葉、特にハムレットが「反抗的な気質」を身につけるときのように、ある気質を「身につける」というアイデアにま つわる言葉を再構築しており、『失楽園』における「(神の)恐怖を身につけることができる」息子に似ている[150]。 1749年頃に出版されたヘンリー・フィールディングの『トム・ジョーンズ』では、トム・ジョーンズとミスター・パートリッジによるハムレットの訪問が描 かれており、「劇中劇」との類似性が指摘されている[151]。 対照的に、1776年から1796年にかけて書かれたゲーテのビルドゥングスロマン『ヴィルヘルム・マイスターの徒弟時代』では、ハムレットの演出が核と なっているだけでなく、幽霊とヴィルヘルム・マイスターの死んだ父親との間に類似性が生じている[151]。 [151]その10年後、ディケンズの『Great Expectations』にはハムレットに似たプロットの要素が多く含まれている。復讐を動機とする行動によって駆動され、幽霊のような登場人物(アベ ル・マグウィッチとミス・ハビシャム)が登場し、主人公の罪の意識に焦点が当てられている。 [151]学者のアレクサンダー・ウェルシュは、『Great Expectations』は「自伝的小説」であり、「『ハムレット』そのものの精神分析的読解を先取りしている」と指摘する[152]。ほぼ同時期に、 ジョージ・エリオットの『The Mill on the Floss』が出版され、「正気であるという評判はあるが」[153]「ハムレットと明確に比較される」マギー・タリバーが登場する[154]。 1920年代には、ジェイムズ・ジョイスが『ユリシーズ』の中で執着と復讐を取り除いたハムレットの「より明るいバージョン」を作り上げているが、その主 な類似点はホメロスの『オデュッセイア』である[151]。 1990年代には、2人の小説家がハムレットから明確な影響を受けている。アンジェラ・カーターの『ワイズ・チルドレン』では、『To be or not to be』が歌とダンスのルーティンとして再構築され、アイリス・マードックの『The Black Prince』では、エディプスのテーマと殺人が、ハムレットに取り憑かれた作家ブラッドリー・ピアソンとライバルの娘との恋愛と絡み合っている。 初めて『ハムレット』を読んだ女性が、「あの戯曲を賞賛する理由がわからない。あの戯曲は引用の羅列にすぎない」。 - アイザック・アシモフ『アシモフのシェイクスピア・ガイド』p.vii、アヴェナル・ブックス、1970年 |