纏足

Foot binding

A

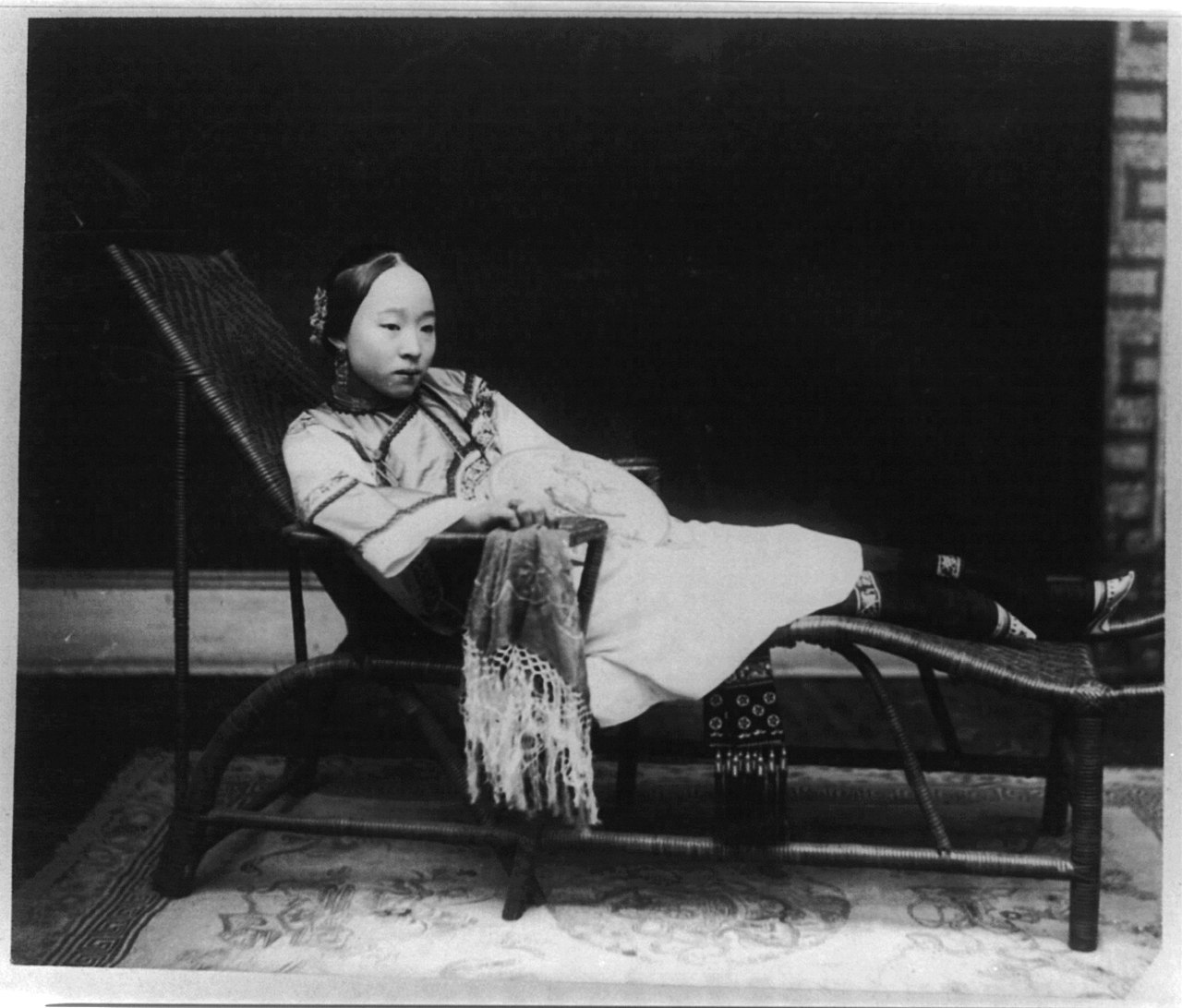

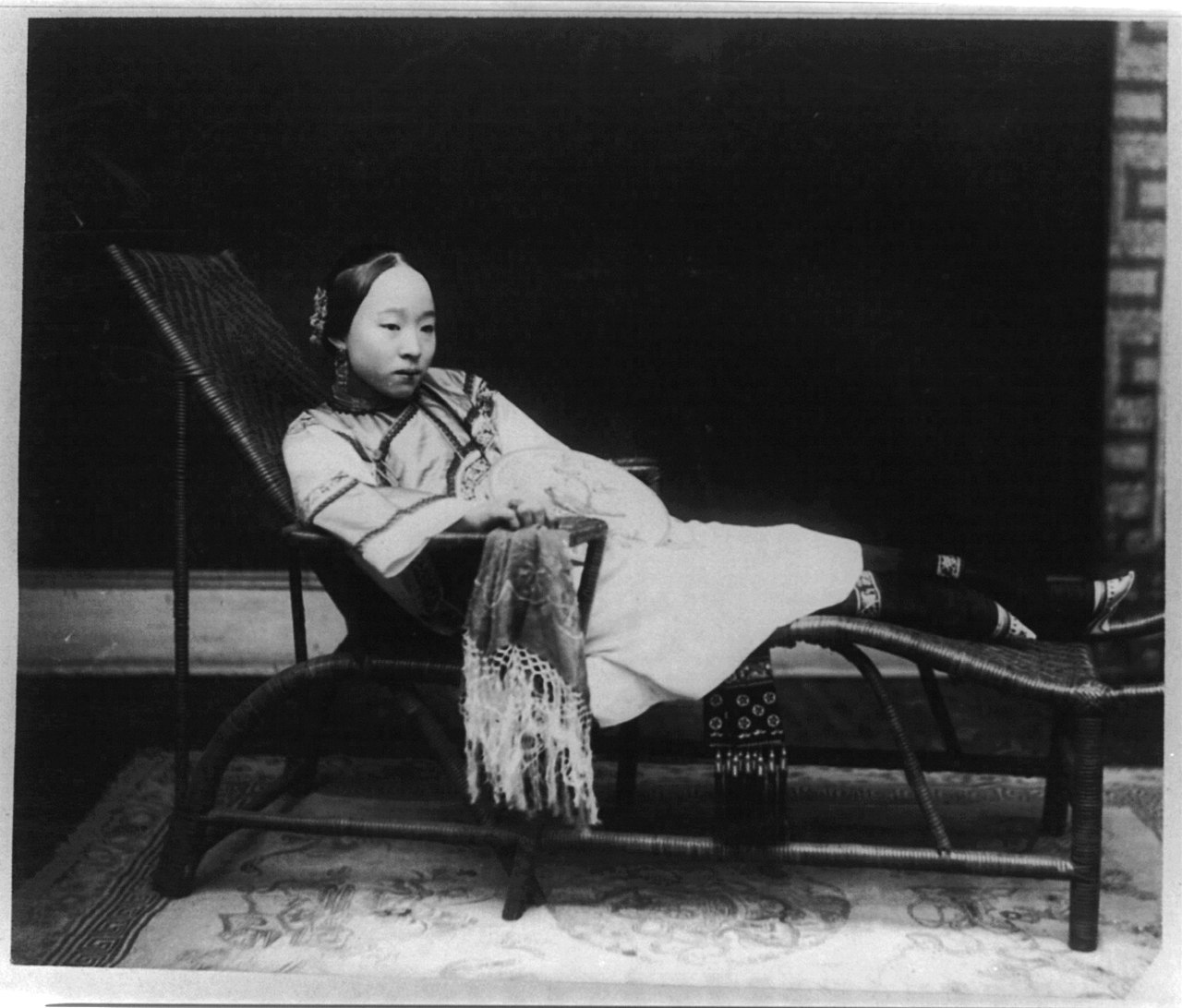

Chinese Golden Lily Foot, Lai Afong, c1870s

☆纏足=てんそく[=足縛り]

(簡体字:缠足;繁体字:纏足;拼音:chánzú)とは、中国の風習で、少女の足を折って強く縛り、その形や大きさを変える行為である。纏足で変形した

足は蓮の足と呼ばれ、それに合わせて作られた靴は蓮の靴と呼ばれた。中国後期の帝国時代において、縛られた足は身分を示す象徴であり、女性の美の印とされ

た。しかし纏足は痛みを伴う慣習であり、女性の移動を制限し、生涯にわたる障害をもたらした。

纏足の普及と実践は、時代、地域、社会階級によって異なった。[1]

この慣習は10世紀の五代十国時代に宮廷舞踊家たちの間で始まった可能性があり、宋代には次第に上流階級に広まり、清代(1644-1912)には下層階

級へも普及した。満州族の皇帝は17世紀にこの慣習を禁止しようとしたが失敗した。[2]

一部の地域では、纏足が結婚の機会を増やすとされた。19世紀までに中国女性の40~50%が足を縛られていたと推定され、漢民族の上流階級女性ではほぼ

100%に達したとされる。[3]

トルキスタン人、満州人、モンゴル人、チベット人などの辺境民族は一般的に纏足を実践しなかった。[4][5][6]

19世紀後半にはキリスト教宣教師や中国の改革派がこの慣習に異議を唱えたが、反纏足運動の努力を経て慣習が廃れ始めたのは20世紀初頭になってからであ

る。また、上流階級や都市部の女性は貧しい農村部の女性より早くこの慣習を止めた。[7]

2007年までに、足を縛られた経験のある高齢の中国人女性はごくわずかしか生存していなかった。[8]

| Foot binding

(simplified Chinese: 缠足; traditional Chinese: 纏足; pinyin: chánzú), or

footbinding, was the Chinese custom of breaking and tightly binding the

feet of young girls to change their shape and size. Feet altered by

foot binding were known as lotus feet and the shoes made for them were

known as lotus shoes. In late imperial China, bound feet were

considered a status symbol and a mark of feminine beauty. However, foot

binding was a painful practice that limited the mobility of women and

resulted in lifelong disabilities. The prevalence and practice of foot binding varied over time, by region, and by social class.[1] The practice may have originated among court dancers during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in 10th-century China and gradually became popular among the elite during the Song dynasty, later spreading to lower social classes by the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). Manchu emperors attempted to ban the practice in the 17th century but failed.[2] In some areas, foot binding raised marriage prospects. It has been estimated that by the 19th century 40–50% of all Chinese women may have had bound feet, rising to almost 100% among upper-class Han Chinese women.[3] Frontier ethnic groups such as Turkestanis, Manchus, Mongols, and Tibetans generally did not practice footbinding.[4][5][6] While Christian missionaries and Chinese reformers challenged the practice in the late 19th century, it was not until the early 20th century that the practice began to die out, following the efforts of anti-foot binding campaigns. Additionally, upper-class and urban women dropped the practice sooner than poorer rural women.[7] By 2007, only a handful of elderly Chinese women whose feet had been bound were still alive.[8] |

纏足=てんそく[=

足縛り](簡体字:缠足;繁体字:纏足;拼音:chánzú)とは、中国

の風習で、少女の足を折って強く縛り、その形や大きさを変える行為である。纏足で変形した足は蓮の足と呼ばれ、それに合わせて作られた靴は蓮の靴と呼ば

れた。中国後期の帝国時代において、縛られた足は身分を示す象徴であり、女性の美の印とされた。しかし纏足は痛みを伴う慣習であり、女性の移動を制限

し、生涯にわたる障害をもたらした。 纏足の普及と実践は、時代、地域、社会階級によって異なった。[1] この慣習は10世紀の五代十国時代に宮廷舞踊家たちの間で始まった可能性があり、宋代には次第に上流階級に広まり、清代(1644-1912)には下層階 級へも普及した。満州族の皇帝は17世紀にこの慣習を禁止しようとしたが失敗した。[2] 一部の地域では、纏足が結婚の機会を増やすとされた。19世紀までに中国女性の40~50%が足を縛られていたと推定され、漢民族の上流階級女性ではほ ぼ100%に達したとされる。[3] トルキスタン人、満州人、モンゴル人、チベット人などの辺境民族は一般的に纏足を実践しなかった。[4][5][6] 19世紀後半にはキリスト教宣教師や中国の改革派がこの慣習に異議を唱えたが、反纏足運動の努力を経て慣習が廃れ始めたのは20世紀初頭になってからで ある。また、上流階級や都市部の女性は貧しい農村部の女性より早くこの慣習を止めた。[7] 2007年までに、足を縛られた経験のある高齢の中国人女性はごくわずかしか生存していなかった。[8] |

| History Origin  A black and white stylised illustration of a seated woman, one foot resting on top of her left thigh, wrapping and binding her right foot. 18th-century illustration showing Yao Niang binding her own feet There are a number of stories about the origin of foot binding before its establishment during the Song dynasty. One of these accounts is of Pan Yunu, a favourite consort of the Southern Qi Emperor Xiao Baojuan. In the story, Pan Yunu, renowned for having delicate feet, performed a dance barefoot on a floor decorated with the design of a golden lotus. The Emperor, expressing admiration, said that "lotus springs from her every step!" (bù bù shēng lián 歩歩生蓮), a reference to the Buddhist legend of Padmavati, under whose feet lotus springs forth. This story may have given rise to the terms 'golden lotus' or 'lotus feet' used to describe bound feet; there is no evidence, however, that Consort Pan ever bound her feet.[9] The general view is that the practice is likely to have originated during the reign of the 10th-century Emperor Li Yu of the Southern Tang, just before the Song dynasty.[2] Li Yu created a 1.8-meter-tall (6 ft) golden lotus decorated with precious stones and pearls and asked his concubine Yao Niang (窅娘) to bind her feet in white silk into the shape of the crescent moon. She then performed a dance on the points of her bound feet on the lotus.[2] Yao Niang's dance was said to be so graceful that others sought to imitate her.[10] The binding of feet was then replicated by other upper-class women and the practice spread.[11] Some of the earliest possible references to foot binding appear around 1100, when a couple of poems seemed to allude to the practice.[12][13][14][15] Soon after 1148,[15] in the earliest extant discourse on the practice of foot binding, scholar Zhang Bangji [zh] wrote that a bound foot should be arch shaped and small.[16][17] He observed that "women's foot binding began in recent times; it was not mentioned in any books from previous eras."[15] In the 13th century, scholar Che Ruoshui [zh] wrote the first known criticism of the practice: "Little girls not yet four or five years old, who have done nothing wrong, nevertheless are made to suffer unlimited pain to bind [their feet] small. I do not know what use this is."[15][18][19]  Southern Song zaju actresses with a form of footbinding of the period[20] The earliest archeological evidence for foot binding dates to the tombs of Huang Sheng, who died in 1243 at the age of 17, and Madame Zhou, who died in 1274. Each woman's remains showed feet bound with gauze strips measuring 1.8 m (6 ft) in length. Zhou's skeleton, particularly well preserved, showed that her feet fit into the narrow, pointed slippers that were buried with her.[15] The style of bound feet found in Song dynasty tombs, where the big toe was bent upwards, appears to be different from 'the 'three-inch golden lotus' of later eras. The more severe form of footbinding may have developed in the 16th century.[21][22] |

歴史 起源  座った女性の白黒の様式化されたイラスト。片足を左太ももに載せ、右足を包み縛っている。 18世紀のイラスト。姚娘が自ら足を縛る様子を描いたもの 宋代に確立される前の纏足の起源については、いくつかの説がある。その一つが、南斉の皇帝・蕭保勲の寵愛を受けた側室・潘玉嬪の物語だ。この話では、繊細 な足で知られた潘玉女が、金色の蓮の花模様が施された床の上で裸足で舞いを披露した。皇帝は感嘆し「彼女の歩むところごとに蓮が咲く!」(歩歩生蓮)と称 賛した。これは仏教の伝説「パドマヴァティ」に由来する表現で、彼女の足元には蓮が咲くという話である。この故事が「金蓮足」や「蓮足」という縛足表現の 起源となった可能性がある。ただし潘妃自身が足を縛った証拠は存在しない[9]。 一般的な見解では、この慣習は宋朝直前の10世紀、南唐の李裕帝の治世に起源を持つと考えられている。[2] 李勰は宝石と真珠で飾られた高さ1.8メートル(6フィート)の黄金の蓮を作り、側室の窅娘(ヤオニアン)に白い絹で足を三日月形に縛らせた。彼女は縛ら れた足の先で蓮の上を踊った。[2] 窅娘の舞は極めて優雅であったため、人々は彼女を真似ようとしたと言われる。[10] こうして纏足は他の上流階級の女性たちにも模倣され、広く普及した。[11] 纏足に関する最も古い言及は1100年頃に見られ、数編の詩がこの慣習をほのめかしているようだ。[12][13][14] [15] 1148年直後[15]、現存最古の纏足言説において、学者張邦基[zh]は縛られた足はアーチ状で小さくあるべきと記した[16][17]。彼は「女性 の纏足は近世に始まったもので、過去の書物には一切言及されていない」と観察している[15]。13世紀には、学者・車若水[zh]がこの慣習に対する最 初の批判を記した。「まだ四、五歳にも満たない幼い娘たちが、何の過ちも犯していないのに、足を小さく縛るために計り知れない苦悩を強いられる。これが何 の役に立つのか、私にはわからない」[15][18][19]  南宋時代の雑劇女優たち。当時の纏足様式を再現[20] 纏足の最古の考古学的証拠は、1243年に17歳で亡くなった黄聖と、1274年に亡くなった周夫人の墓から発見された。両者の遺骸からは、長さ1.8 メートル(6フィート)のガーゼ布で縛られた足が確認された。周夫人の骨格は特に良好な状態で保存されており、彼女の足が埋葬時に同葬された細長い先のと がった靴にぴったり収まっていたことが確認された[15]。宋代墓から発見された縛り足の様式は、親指が上方に反り返るもので、後世の「三寸金蓮」とは異 なるようだ。より過酷な形の纏足は16世紀に発展した可能性がある[21][22]。 |

Later eras Small bound feet were once considered beautiful while large unbound feet were judged as crude. At the end of the Song dynasty, men would drink from a special shoe, the heel of which contained a small cup. During the Yuan dynasty some would also drink directly from the shoe itself. This practice was called 'toast to the golden lotus' and lasted until the late Qing dynasty.[23] The first European to mention foot binding was the Italian missionary Odoric of Pordenone in the 14th century, during the Yuan dynasty.[24] However no other foreign visitors to Yuan China mentioned the practice, including Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo (who nevertheless noted the dainty walk of Chinese women, who took very small steps), perhaps an indication that it was not a widespread or extreme practice at that time.[25] The Mongols themselves did not practice footbinding but it was permitted for their Chinese subjects.[26][11] The practice became increasingly common among the gentry families, later spreading to the general populace, as commoners and theatre actors alike adopted foot binding. By the Ming period the practice was no longer the preserve of the gentry but it was considered a status symbol.[27][28][29] As foot binding restricted the movement of a woman, one side effect of its rising popularity was the corresponding decline of the art of women's dance in China, and it became increasingly rare to hear about beauties and courtesans who were also great dancers after the Song era.[30][31]  A lotus shoe for bound feet, Louise Weiss collection, Saverne The Manchus issued a number of edicts to ban the practice, first in 1636 when the Manchu leader Hong Taiji declared the founding of the new Qing dynasty, then in 1638, and another in 1664 by the Kangxi Emperor.[27] Few Han Chinese complied with the edicts, and Kangxi eventually abandoned the effort in 1668. By the 19th century, it was estimated that 40–50% of Chinese women had bound feet. Among upper class Han Chinese women, the figure was almost 100%.[8] Bound feet became a mark of beauty and were also a prerequisite for finding a husband. They also became an avenue for poorer women to marry up in some areas, such as Sichuan.[32] In late 19th century Guangdong it was customary to bind the feet of the eldest daughter of a lower-class family who was intended to be brought up as a lady. Her younger sisters would grow up to be bond-servants or domestic slaves and be able to work in the fields, but the eldest daughter would be assumed never to have the need to work. Women, their families and their husbands took great pride in tiny feet, with the ideal length, called the 'Golden Lotus', being about three Chinese inches (寸) long—around 11 cm (4.3 in).[33][34] This pride was reflected in the elegantly embroidered silk slippers and wrappings girls and women wore to cover their feet. Handmade shoes served to exhibit the embroidery skill of the wearer as well.[35] These shoes also served as support, as some women with bound feet might not have been able to walk without the support of their shoes and would have been severely limited in their mobility.[36] Contrary to missionary writings, many women with bound feet were able to walk and work in the fields, albeit with greater limitations than their non-bound counterparts.[37] In the 19th and early 20th centuries, there were dancers with bound feet as well as circus performers who stood on prancing or running horses. Women with bound feet in one village in Yunnan Province formed a regional dance troupe to perform for tourists in the late 20th century, though age has since forced the group to retire.[38] In other areas, women in their 70s and 80s assisted in the rice fields (albeit in a limited capacity) even into the early 21st century.[8] |

後の時代 小さな縛り足はかつて美しいとされ、大きな縛らない足は粗末だと判断された。 宋の末期には、男性は特別な靴から酒を飲んだ。その靴のかかとには小さな杯が仕込まれていた。元代には靴そのものから直接飲む者もいた。この習慣は「金蓮酒」と呼ばれ、清の末期まで続いた。[23] 纏足を初めて言及したヨーロッパ人は、14世紀のイタリア人宣教師オドリック・オブ・ポルデノーネである。これは元王朝時代の記録だ[24]。しかしイブ ン・バットゥータやマルコ・ポーロを含む他の元朝訪問の外国人旅行者はこの習慣に触れていない。ポーロは中国の女性が非常に小さな歩幅で優雅に歩く様子を 記しているが、これは当時この習慣が広く普及した極端なものではなかったことを示唆しているかもしれない。[25] モンゴル人自身は纏足を実践しなかったが、中国の臣民にはこれを許容した。[26][11] この慣習は士紳階級の家庭で次第に普及し、後に庶民や演劇俳優にも広まった。明代にはもはや士紳階級だけの習慣ではなくなったが、依然として身分を示す象 徴と見なされていた。[27][28] [29] 纏足は女性の動きを制限したため、その普及に伴い中国における女性の舞踊芸術は衰退した。宋代以降、舞踊の達人でもあった美女や遊女の話は次第に聞かれな くなった。[30][31]  纏足用の蓮の靴、ルイーズ・ワイス所蔵、サヴェルヌ 満州人はこの慣習を禁止する勅令を幾度か発した。最初に発令したのは1636年、満州の指導者ホンタイジが新たな清王朝の建国を宣言した時である。次に 1638年、そして1664年には康熙帝が勅令を出した。[27] 漢民族のほとんどはこの勅令に従わず、康熙帝は結局1668年にこの試みを断念した。19世紀までに、中国女性の40~50%が足を縛っていたと推定され る。上流階級の漢民族女性ではほぼ100%に上った[8]。縛られた足は美の象徴となり、夫を見つけるための必須条件でもあった。また四川など一部の地域 では、貧しい女性が身分を上げて結婚する手段ともなった。[32] 19世紀末の広東省では、下層階級の家庭において、令嬢として育てる長女の足を縛る習慣があった。妹たちは使用人や家内奴隷として育ち、畑仕事もできた が、長女は働く必要がないとみなされた。女性自身、その家族、そして夫は小さな足を大いに誇りに思い、「黄金の蓮」と呼ばれる理想的な足の長さは約3寸 (11センチ)とされた。[33][34] この誇りは、少女や女性が足を覆うために着用した、優雅に刺繍された絹のスリッパや包み布にも反映されていた。手作りの靴は、履く者の刺繍技術を示す役割 も果たした[35]。また、靴は支えの役割も担っていた。縛られた足の女性の中には、靴の支えなしでは歩けず、移動が著しく制限される者もいたからだ [36]。宣教師の記述とは異なり、縛られた足の女性の多くは、縛られていない女性に比べ制限は大きかったものの、歩くことも畑仕事もできた。[37] 19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて、纏足の踊り子や、跳ね回る馬や走る馬の上で演技するサーカスの芸人たちが存在した。雲南省のある村では、20世紀後半 に纏足の女性たちが観光客向けの地域舞踊団を結成したが、その後、年齢のため解散を余儀なくされた。[38] 他の地域では、21世紀初頭になっても70代や80代の女性が(能力は限られていたが)田んぼの手伝いをしていた。[8] |

| Decline Opposition to foot binding had been raised by some Chinese writers in the 18th century. In the mid-19th century, many of the leaders of the Taiping Rebellion were men of Hakka background whose women did not bind their feet, and they outlawed foot binding in areas under their control.[39][40] However the rebellion failed and Christian missionaries, who had provided education for girls and actively discouraged what they considered a barbaric practice that had deleterious social effect on women,[41] then played a part in changing elite opinion on foot binding through education, pamphleteering and lobbying of the Qing court,[42][43] as no other culture in the world practised the custom of foot binding.[44] The earliest-known Western anti-foot binding society was formed in Amoy (Xiamen) in 1874. 60–70 Christian women in Xiamen attended a meeting presided over by a missionary, John MacGowan, and formed the Natural Foot Society (Tianzu Hui (天足会), literally Heavenly Foot Society).[45][46] MacGowan held the view that foot binding was a serious problem that called into doubt the whole of Chinese civilization; he felt that "the nefarious civilization interferes with Divine Nature."[47] Members of the Heavenly Foot Society vowed not to bind their daughters' feet.[44][41] In 1895, Christian women in Shanghai led by Alicia Little, also formed a Natural Foot Society.[46][48] It was also championed by the Woman's Christian Temperance Movement founded in 1883 and advocated by missionaries including Timothy Richard, who thought that Christianity could promote equality between the sexes.[49] This missionary-led opposition had stronger impacts than earlier Han or Manchu opposition.[50] Western missionaries established the first schools for girls, and encouraged women to end the practice of foot binding.[51] Christian missionaries did not conceal their shock and disgust either when explaining the process of foot binding to Western peers and their descriptions shocked their audience back home.[50] |

衰退 纏足への反対は18世紀に一部の中国作家によって提起されていた。19世紀半ば、太平天国の乱の指導者の多くは客家系の出身で、その女性たちは足を縛らな かった。彼らは支配地域で纏足を禁止した。[39][40] しかし反乱は失敗に終わり、その後キリスト教宣教師たちが女子教育を提供し、女性への社会的悪影響を及ぼす野蛮な慣習と見なした纏足を積極的に阻止した [41]。彼らは教育活動、パンフレット配布、清朝政府への働きかけを通じて、纏足に対する上流階級の意見転換に一役買った[42][43]。当時、世界 の他の文化圏では纏足の慣習は存在しなかったからだ。[44] 西洋における最古の反纏足団体は1874年、アモイ(厦門)で結成された。60~70名のキリスト教徒女性が宣教師ジョン・マクゴーワンの主宰する集会に 参加し、「天足会」(文字通り「天の足の会」)を結成した。[45][46] マクゴーワンは纏足が深刻な問題であり、中国文明全体を疑わせるものだと考えていた。彼は「この邪悪な文明は神聖な本性に干渉する」と感じていた。 [47] 天足会の会員は娘の足を縛らないことを誓った。[44][41] 1895年には、アリシア・リトル率いる上海のキリスト教徒女性たちも自然足会を結成した。[46][48] 1883年に設立された女性キリスト教禁酒運動もこれを支持し、ティモシー・リチャードら宣教師が提唱した。彼らはキリスト教が男女平等を促進できると考 えていた。[49] この宣教師主導の反対運動は、以前の漢民族や満州族の反対運動よりも強い影響力を持った。[50] 西洋の宣教師たちは最初の女子学校を設立し、女性に纏足の慣習を止めるよう促した。[51] キリスト教宣教師たちは、西洋の同僚たちに纏足の過程を説明する際に、その衝撃と嫌悪感を隠さなかった。彼らの描写は故郷の聴衆に衝撃を与えたのである。 [50] |

| Reform-minded

Chinese intellectuals began to consider foot binding to be an aspect of

their culture that needed to be eliminated.[52] In 1883, Kang Youwei

founded the Anti-footbinding Society near Canton to combat the

practice, and anti-foot binding societies appeared across the country,

with membership for the movement claimed to reach 300,000.[53][54] The

anti-foot binding movement stressed pragmatic and patriotic reasons

rather than feminist ones, arguing that abolition of foot binding would

lead to better health and more efficient labour. Kang Youwei submitted

a petition to the throne commenting on the fact that China had become a

joke to foreigners and that "footbinding was the primary object of such

ridicule."[55] Reformers such as Liang Qichao, influenced by Social Darwinism, also argued that it weakened the nation, since enfeebled women supposedly produced weak sons.[56] In his "On Women's Education", Liang Qichao asserts that the root cause of national weakness inevitably lies the lack of education for women. Qichao connected education for women and foot binding: "As long as foot binding remains in practice, women's education can never flourish."[57] Qichao was also disappointed that foreigners had opened the first schools as he thought that the Chinese should be teaching Chinese women.[55] At the turn of the 20th century, early feminists, such as Qiu Jin, called for the end of foot binding.[58][59] In 1906, Zhao Zhiqian wrote in Beijing Women's News to blame women with bound feet for being a national weakness in the eyes of other nations.[60] Many members of anti-foot binding groups pledged to not bind their daughters' feet nor to allow their sons to marry women with bound feet.[46][61] In 1902, Empress Dowager Cixi issued an anti-foot binding edict, but it was soon rescinded.[citation needed] In 1912 the new Republic of China government banned foot binding, though the ban was not actively implemented,[62] and leading intellectuals of the May Fourth Movement saw foot binding as a major symbol of China's backwardness.[63] Provincial leaders, such as Yan Xishan in Shanxi, engaged in their own sustained campaign against foot binding with foot inspectors and fines for those who continued the practice,[62] while regional governments of the later Nanjing regime also enforced the ban.[42] The campaign against foot binding was successful in some regions. In one province, a 1929 survey showed that, while only 2.3% of girls born before 1910 had unbound feet, 95% of those born after were not bound.[64] In a region south of Beijing, Dingxian, where over 99% of women once had bound feet, no new cases were found among those born after 1919.[65][66] In Taiwan, the practice was also discouraged by the ruling Japanese from the beginning of Japanese rule, and from 1911 to 1915 it was gradually made illegal.[67] The practice lingered on in some regions in China. In 1928, a census in rural Shanxi found that 18% of women had bound feet,[38] while in some remote rural areas, such as Yunnan Province, it continued to be practiced until the 1950s.[68][69] In most parts of China the practice had virtually disappeared by 1949.[64] The practice was also stigmatized in Communist China, and the last vestiges of foot binding were stamped out, with the last new case of foot binding reported in 1957.[70][71] By the 21st century, only a few elderly women in China still had bound feet.[72][73] In 1999, the last shoe factory making lotus shoes, the Zhiqian Shoe Factory in Harbin, closed.[74][75] |

改

革志向の中国知識人は、纏足を排除すべき文化の一面と見なすようになった[52]。1883年、康有為は広州近郊に反纏足協会を設立し、この慣習と闘っ

た。反纏足協会は全国に広がり、運動の参加者は30万人に達したと主張された[53]。[54]

反纏足運動は女性解放論よりも実用性と愛国心を強調し、纏足廃止が健康増進と労働効率向上につながると主張した。康有為は上奏文で「中国が外国人の笑いも

のとなり、纏足が嘲笑の主因である」と指摘した。[55] 社会ダーウィニズムの影響を受けた梁啓超ら改革派は、弱った女性が弱い息子を生むため、纏足は国民を弱体化させるとも主張した[56]。梁啓超は『女教育 論』において、国家の弱さの根本原因は女性の教育不足にあると断言している。粱啓超は女性の教育と纏足を結びつけた。「纏足が存続する限り、女性の教育は 決して栄えることはない」と述べた[57]。また粱啓超は、最初の学校を外国人が開いたことに失望していた。中国人が中国人の女性を教えるべきだと考えて いたからだ[55]。20世紀の変わり目には、秋瑾のような初期のフェミニストたちが纏足の廃止を訴えた。[58][59] 1906年、趙之謙は『北京婦女新聞』に、纏足の女性こそが他国から見た国民の弱点だと非難する文章を寄稿した。[60] 反纏足団体の多くのメンバーは、娘の足を縛らないこと、また息子が纏足の女性と結婚することを許さないことを誓約した。[46][61] 1902年、西太后は纏足禁止の勅令を発したが、すぐに撤回された。 1912年、新たに成立した中華民国政府は纏足を禁止したが、この禁止令は積極的に施行されなかった[62]。また、五四運動の主導的知識人たちは、纏足 を中国の後進性を象徴する主要な要素と見なした。[63] 山西の閻錫山のような地方指導者は、足検査官を配置し、慣行を続ける者には罰金を科すなど、独自の持続的な纏足反対運動を展開した[62]。一方、後の南 京政権の地方政府も禁止令を施行した[42]。纏足反対運動は一部の地域で成功を収めた。ある省では、1929年の調査で、1910年以前に生まれた女児 の纏足率はわずか2.3%であったのに対し、その後生まれの女児の95%は纏足ではなかったことが示された[64]。北京南部の定県では、かつて女性の 99%以上が纏足をしていたが、1919年以降に生まれた者では新たな事例は確認されなかった[65][66]。台湾では、日本統治開始当初から日本当局 が纏足を抑制し、1911年から1915年にかけて段階的に違法化された[67]。中国本土の一部地域では慣習が継続した。1928年、山西省農村部の調 査では、女性の18%が纏足[38]をしていた。一方、雲南省などの辺境農村部では1950年代まで慣行が続いた[68]。[69] 中国の大部分では1949 年までにこの慣習は事実上消滅した。[64] 共産主義中国でもこの慣習は非難され、最後の痕跡は根絶された。新たな纏足の事例が報告されたのは1957年が最後である。[70] [71] 21世紀に入ると、中国で纏足を経験した高齢女性はごく少数となった。[72][73] 1999年には、蓮の靴を製造していた最後の靴工場であるハルビンの知前靴廠が閉鎖された。[74][75] |

| Practice Variations and prevalence  A comparison between a woman with unbound feet (left) and a woman with bound feet (right) in 1902. Foot binding was practised in various forms and its prevalence varied in different regions.[76] A less severe form in Sichuan, called "cucumber foot" (huángguā jiǎo 黃瓜腳) due to its slender shape, folded the four toes under but did not distort the heel or taper the ankle.[38][77] Some working women in Jiangsu made a pretence of binding while keeping their feet natural.[42] Not all women were always bound—some women once bound remained bound throughout their lives, some were only briefly bound and some were bound until marriage.[78] Foot binding was most common among women whose work involved domestic crafts and those in urban areas;[42] it was also more common in northern China, where it was widely practised by women of all social classes, but less so in parts of southern China such as Guangdong and Guangxi, where it was largely a practice of women in the provincial capitals or among the gentry.[79][16] Feet were bound to their smallest in the northern provinces of Hebei, Shandong, Shanxi and Shaanxi, but the binding was less extreme and less common in the southern provinces of Guangdong, Guangxi, Yunnan and Guizhou, where not all daughters of the wealthy had bound feet.[80] Foot binding limited the mobility of girls, so they became engaged in handwork from childhood.[35] It is thought that the necessity for female labour in the fields owing to a longer growing season in the South and the impracticability of bound feet working in wet rice fields limited the spread of the practice in the countryside of the South.[81] However some farming women bound their daughter's feet, but "the process began later than in elite families, and feet were bound more loosely among the poor."[82] Scholarly estimates of the number of women with bound feet at the height of the practice range widely, but most modern historians place the figure between 10 and 20 million. Historian John R. Shepherd, drawing on Qing dynasty and early Republican census records, argues that footbinding reached its demographic peak in the mid- to late-19th century, particularly among Han women in the central and eastern provinces.[83] Based on Taiwan's 1905 census, Shepherd found that over two-thirds of Hoklo women had bound feet, while Hakka and indigenous groups had binding rates below 1 percent.[84] Laurel Bossen and Hill Gates, drawing on interviews with thousands of elderly rural Chinese women, conclude that footbinding was nearly universal among inland Han women born before 1910, although its prevalence declined rapidly after 1915.[85] The practice transcended social class, though its function varied. While gentry families bound their daughters' feet to conform to elite aesthetics and reinforce chastity, some rural households bound only one daughter's feet to improve marriage prospects while leaving others unbound for agricultural labor.[86] In textile-producing areas, footbinding was often linked to a household labor strategy: bound girls were confined indoors and tasked with spinning and weaving, while unbound girls performed fieldwork.[87] Scholar C. Fred Blake argued that footbinding in these contexts "appropriated" female labor by enforcing immobility within the domestic sphere.[88] Urban–rural differences in prevalence became especially stark in the early 20th century. In port cities such as Xiamen and Shanghai, anti-footbinding societies successfully curbed the practice by the 1910s. A 1937 survey in Xiamen found that only 4.5 percent of women still had bound feet, almost all of them born before 1905.[citation needed] In contrast, rural surveys from the 1920s show lingering adherence: in villages of Hebei Province, 99.2 percent of women born before 1890 had bound feet, and as late as 1915, 60 percent of young girls were still being bound.[89] These disparities suggest that urban elites abandoned footbinding first, while the practice persisted in the countryside into the 1930s. Ethnic variation played a significant role in footbinding's distribution. Manchu women were officially prohibited from binding their feet and instead wore high-soled "flower bowl" shoes to mimic the swaying gait of bound feet.[90] Other non-Han groups, including Mongols and Tibetans, generally rejected the custom.[91] Nonetheless, assimilation occurred in some regions: Hui Muslim women in Gansu and Dungan communities in Central Asia retained footbinding into the 20th century, influenced by neighboring Han populations.[92] In multiethnic areas, bound feet became a visible marker of Han female identity and distinction from non-Han groups.[93] Recent scholarship has also challenged the notion that footbinding was solely patriarchal or aesthetic. Bossen and Gates argue that the practice was often embedded in rural household economies, where it kept girls indoors to perform textile labor critical to family income.[94] Their research shows that footbinding was strongly associated with regions engaged in hand-spinning, and declined rapidly once machine-made yarn displaced home production.[95] They conclude that the practice's demise stemmed not only from reformist ideology, but from material shifts in rural labor and technology.[96] |

慣行 形態と普及状況  1902年、纏足を持つ女性(左)と纏足を持つ女性(右)の比較。 纏足は様々な形態で実践され、その普及率は地域によって異なった。[76] 四川省では「黄瓜脚(huángguā jiǎo)」と呼ばれる軽度の形態がみられた。これは細長い形状からそう呼ばれ、四本の指を折り曲げるが、かかとを変形させたり足首を細くしたりはしな かった。[38] [77] 江蘇省の労働女性の中には、足を自然のままに保ちつつ、纏足しているふりをした者もいた。[42] すべての女性が常に足を纏っていたわけではない。一度纏ったまま生涯を過ごす者もいれば、短期間だけ纏る者、結婚まで纏る者もいた。[78] 纏足は、家庭内手工業に従事する女性や都市部の女性の間で最も一般的であった[42]。また中国北部では、あらゆる階級の女性によって広く行われていた が、広東や広西などの中国南部地域では、省都の女性や士紳階級の間でのみ行われることが多かった[79]。[16] 纏足は河北省、山東省、山西省、陝西省といった北部諸省で最も小さく縛られたが、広東省、広西省、雲南省、貴州省といった南部諸省では縛りが過酷でなく、 普及率も低かった。富裕層の娘たちですら全員が纏足されたわけではなかった。[80] 纏足は少女の移動を制限したため、幼い頃から手仕事に従事するようになった。[35] 南部では生育期間が長く女性の農作業が必要だったこと、また水田作業に纏足が不向きだったことが、南部農村部での風習普及を制限したと考えられている。 [81] ただし一部の農家の女性も娘の足を纏足したが、「その過程は上流階級より遅く始まり、貧しい家庭ではより緩く纏足された」。[82] 纏足の最盛期における女性の数は学者の推定で大きく異なるが、現代の歴史家の大半は1000万から2000万人と見積もっている。歴史家ジョン・R・シェ パードは清朝と民国初期の国勢調査記録に基づき、纏足が19世紀中頃から後半にかけて人口統計上のピークに達したと論じている。特に中部・東部省の漢民族 女性の間で顕著であった。[83] 台湾の1905年国勢調査に基づけば、シェパードは閩南系女性の3分の2以上が纏足だったのに対し、客家系や先住民族グループでは1%未満だったと指摘し ている。[84] ローレル・ボッセンとヒル・ゲイツは、数千人の中国農村部高齢女性へのインタビューから、1910年以前に生まれた内陸部の漢民族女性の間では纏足がほぼ 普遍的だったが、1915年以降は急速に減少したと結論づけている。[85] この慣習は社会階級を超越していたが、その機能は様々であった。士紳階級の家庭では、娘の足を纏足させて上流階級の美意識に合わせ、貞操を強化した。一 方、一部の農村世帯では、結婚の見込みを高めるために一人の娘の足だけを縛り、他の娘は農作業のために縛らなかった。[86] 織物生産地域では、纏足は家庭内労働戦略と結びつくことが多かった。縛られた娘は屋内に閉じ込められ紡績・織物を担当し、縛られていない娘は畑仕事に従事 した。[87] 学者C・フレッド・ブレイクは、こうした文脈における纏足が「女性の労働を収奪した」と論じている。すなわち、家庭内領域での移動制限を強制することで実 現されたのだ。[88] 20世紀初頭には、都市と農村の普及率の差が特に顕著になった。厦門や上海のような港湾都市では、1910年代までに反纏足団体が慣行を抑制することに成 功した。1937年の厦門調査では、足の縛りを残す女性はわずか4.5%で、そのほぼ全員が1905年以前に生まれた者だった。[出典が必要] これに対し、1920年代の農村調査では慣習が根強く残っていた。河北省の村落では、1890年以前に生まれた女性の99.2%が纏足であり、1915年 になっても少女の60%が纏足を施されていた。[89] この格差は、都市のエリート層が最初に纏足を放棄した一方、農村部では1930年代まで慣習が継続したことを示唆している。 民族の差異は纏足の分布に重要な役割を果たした。満州族の女性は公式に纏足を禁じられ、代わりに高い靴底の「花鉢」靴を履いて纏足の揺れる歩き方を模倣し た[90]。モンゴル族やチベット族を含む他の非漢民族グループは、一般的にこの慣習を拒否した。[91] しかしながら、一部の地域では同化現象も生じた。甘粛省の回族女性や中央アジアの東干族コミュニティでは、近隣の漢民族の影響を受け、20世紀に入っても 纏足が継続された。[92] 多民族地域では、纏足は漢民族女性としてのアイデンティティを示す目に見える印となり、非漢民族集団との区別を強調する役割を果たした。[93] 近年の研究では、纏足が単なる家父長制や美意識の産物であるという通説にも異論が呈されている。ボッセンとゲイツは、この慣習が農村家計に組み込まれてい たと主張する。少女を屋内に留め、家計収入に不可欠な織物労働に従事させるためであった[94]。彼らの研究によれば、手紡ぎが盛んな地域で縛足が強く関 連し、機械製糸が家庭生産に取って代わると急速に衰退した[95]。彼らは、この慣習の消滅は改革イデオロギーだけでなく、農村労働と技術における物質的 変化に起因すると結論づけている[96]。 |

| Manchu

women, as well as Mongol and Chinese women in the Eight Banners, did

not bind their feet. The most a Manchu woman might do was to wrap the

feet tightly to give them a slender appearance.[5] The Manchus, wanting

to emulate the particular gait that bound feet necessitated, adapted

their own form of platform shoes to cause them to walk in a similar

swaying manner. These Manchu platform shoes were known as "flower bowl"

shoes (Chinese: 花盆鞋; pinyin: Huāpénxié) or "horse-hoof" shoes (Chinese:

馬蹄鞋; pinyin: Mǎtíxié); they have a platform generally made of wood 5–20

cm (2–6 in) in height and fitted to the middle of the sole, or they

have a small central tapered pedestal. Many Han Chinese in the Inner

City of Beijing did not bind their feet either, and it was reported in

the mid-1800s that around 50–60% of non-banner women had unbound feet.

Han immigrant women to the Northeast came under Manchu influence and

abandoned foot binding.[97] Bound feet nevertheless became a

significant differentiating marker between Han women and Manchu or

other banner women.[5] The Hakka people were unusual among Han Chinese in not practising foot binding.[98][99] Most non-Han Chinese people, such as the Manchus, Mongols and Tibetans, did not bind their feet. Some non-Han ethnic groups did. Foot binding was practised by the Hui Muslims in Gansu Province.[100] The Dungan Muslims, descendants of Hui from northwestern China who fled to central Asia, were also practising foot binding up to 1948.[101] In southern China, in Canton (Guangzhou), 19th-century Scottish scholar James Legge noted a mosque that had a placard denouncing foot binding, saying Islam did not allow it since it constituted violating the creation of God.[102] |

満

州の女性も、八旗のモンゴル人や漢人の女性も、纏足をしなかった。満州の女性が最も行っていたのは、足を細く見せるために強く包帯を巻くことだった

[5]。満州人は、纏足に伴う特有の歩き方を模倣しようと、揺れるような歩き方を再現する独自の厚底靴を開発した。この満州式厚底靴は「花盆鞋」(中国

語: 花盆鞋; ピンイン: Huāpénxié)または「馬蹄鞋」(中国語: 馬蹄鞋; ピンイン:

Mǎtíxié)と呼ばれ、通常5~20センチ(2~6インチ)の木製台座を備えている。Huāpénxié)あるいは「馬蹄靴」(中国語: 馬蹄鞋;

ピンイン:

Mǎtíxié)と呼ばれた。これらは通常、高さ5~20センチ(2~6インチ)の木製台座を靴底の中央に取り付けるか、中央に小さな先細りの台座を備え

ていた。北京城内の多くの漢民族も足を縛らなかった。1800年代半ばの記録によれば、八旗以外の女性の約50~60%が足を縛っていなかった。東北地方

に移住した漢民族の女性は満州の影響を受け、纏足を放棄した[97]。それでもなお、縛られた足は漢民族の女性と満州族や他の八旗の女性を区別する重要な

指標となった。[5] 客家人は漢民族の中で珍しく纏足を実践しなかった。[98][99]満州族、モンゴル族、チベット族など非漢民族の大半は足を縛らなかった。一部の非漢民 族は実践した。甘粛省の回族ムスリムは纏足を実践していた。[100] 中国北西部の回族の末裔で中央アジアに逃れた東干(ドンガン)のイスラム教徒も、1948年まで纏足を続けていた。[101]中国南部、広州(広東)で は、19世紀のスコットランド人学者ジェームズ・レッグが、纏足を非難する掲示を掲げたモスクを目撃している。その掲示には「イスラム教は神の創造を冒涜 する行為として纏足を禁じている」と記されていた。[102] |

The Manchu "flower bowl" shoes designed to imitate bound feet, mid-1880s |

1880年代半ば、纏足を模した満州の「花鉢」靴 |

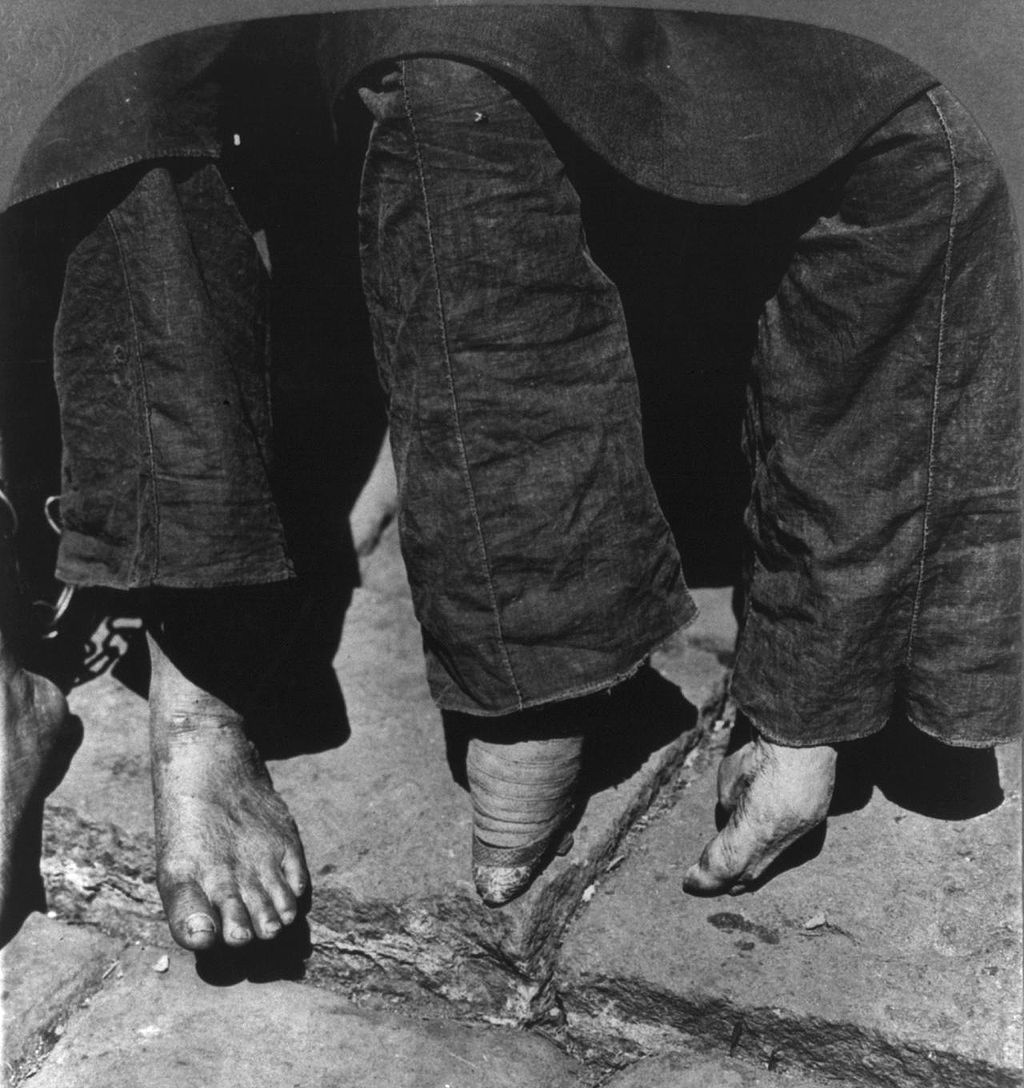

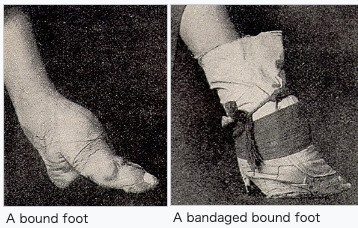

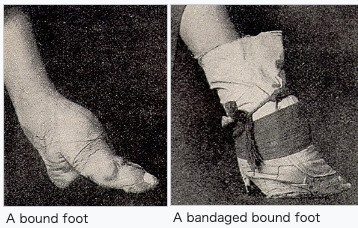

| Process A bound foot  A bandaged bound foot A bandaged bound foot The process was started before the arch of the foot had a chance to develop fully, usually between the ages of four and nine. Binding usually started during the winter months since the feet were more likely to be numb and the pain would not be as extreme.[103] First, each foot would be soaked in a warm mixture of herbs and animal blood. This was intended to soften the foot and aid the binding. Then the toenails were cut back as far as possible to prevent in-growth and subsequent infections, since the toes were to be pressed tightly into the sole of the foot. Cotton bandages, 3 m (10 ft) long and 5 cm (2 in) wide, were prepared by soaking them in the blood and herb mixture. To enable the size of the feet to be reduced, the toes on each foot were curled under, then pressed with great force downwards and squeezed into the sole of the foot until the toes broke.[44] The bandages were repeatedly wound in a figure-eight movement, starting at the inside of the foot at the instep, then carried over the toes, under the foot and around the heel, the broken toes being pressed tightly into the sole of the foot. The foot was drawn down straight with the leg and the arch of the foot forcibly broken. At each pass around the foot, the binding cloth was tightened, pulling the ball of the foot and the heel together, causing the broken foot to fold at the arch, pressing the toes beneath the sole. The binding was pulled so tightly that the girl could not move her toes at all and the ends of the binding cloth were then sewn so that the girl could not loosen it.  An X-ray of two bound feet  Schema of an X-ray comparison between an unbound and bound foot The girl's broken feet required a great deal of care and attention and they would be unbound regularly. Each time the feet were unbound they were washed, the toes checked for injury, and the nails trimmed. When unbound, the broken feet were also kneaded to soften them and the soles of the girl's feet were often beaten to make the joints and broken bones more flexible. The feet were also soaked in a concoction that caused necrotic flesh to fall off.[52] Immediately after this procedure, the girl's broken toes were folded back under and the feet were rebound. The bindings were pulled even tighter each time the girl's feet were rebound. This unbinding and rebinding ritual was repeated as often as possible (for the rich at least once daily, for poor peasants two or three times a week), with fresh bindings. It was generally an elder female member of the girl's family or a professional footbinder who carried out the initial breaking and ongoing binding of the feet. It was considered preferable to have someone other than the mother do it, as she might have been sympathetic to her daughter's pain and less willing to keep the bindings tight.[103] Once a girl's foot had been crushed and bound, attempting to reverse the process by unbinding was painful,[104] and the shape could not be reversed without a woman undergoing the same pain again. The timing and degree of foot binding varied among communities.[105] |

工程 纏足  包帯で巻かれた纏足 包帯で巻かれた纏足 この工程は、足のアーチが完全に発達する前に開始された。通常は4歳から9歳の間のことであった。纏りは冬の間に行われることが多かった。足が感覚を失いやすく、痛みがそれほど激しくないためである。[103] まず、それぞれの足を温かいハーブと動物の血の混合液に浸す。これは足を柔らかくし、縛り付けを容易にするためであった。次に、爪は可能な限り深く切り落 とされた。これは、指が足の裏に強く押し込まれるため、爪の埋没やそれに伴う感染を防ぐためであった。綿の包帯(長さ3m、幅5cm)は、血液と薬草の混 合液に浸して準備された。足のサイズを縮小するため、各足の指を内側に丸め、強い力で下方に押し付け、足の裏に押し込み、指を折るまで続けた。[44] 包帯は八の字運動で繰り返し巻き付けられた。足の内側、甲の部分から始め、指の上を通り、足の裏をくぐり、かかとを回り込むように巻かれた。折れた指は足 の裏に強く押し付けられた。足は脚と一直線に伸ばされ、足のアーチは強制的に折られた。足を巻き付ける度に包帯は締め付けられ、足の付け根とかかとを引き 寄せ、折れた足をアーチ部分で折り曲げ、つま先を足の裏に押し込んだ。包帯は少女が全く指を動かせないほど強く締められ、包帯の端は少女が緩められないよ う縫い付けられた。  縛られた二足の足のX線写真  縛られていない足と縛られた足のX線比較図 少女の折れた足は多大な手入れと注意を必要とし、定期的に縛りを解かれた。足を解くたびに洗浄され、足の指の損傷が確認され、爪が切られた。縛りを解いた 状態では、壊れた足を揉みほぐして柔らかくし、少女の足の裏を叩くことも多かった。これは関節や骨折した骨をより柔軟にするためである。また足を薬液に浸 すこともあった。この薬液は壊死した肉を剥がれ落ちるように作用する。[52] この処置直後、少女の折れた足指は再び裏側に折り曲げられ、足は再縛りされた。再縛りの度に縛りはさらに強く締め付けられた。この解き直しと再縛りの儀礼 は可能な限り頻繁に繰り返された(富裕層では少なくとも1日1回、貧しい農民では週に2、3回)。その度に新しい包帯が用いられた。足の最初の折断と継続 的な縛りは、通常、少女の家族の長老女性か、専門の纏足師が行った。母親以外の者が行う方が好ましいと考えられていた。母親は娘の痛みに同情し、縛りを強 く保つことに消極的になる恐れがあったからだ。[103] 一度足を押し潰して縛り上げると、縛りを解いて元に戻そうとすると痛みを伴った[104]。また、女性が再び同じ痛みに耐えなければ、足の形を元に戻すことは不可能だった。足の纏足の時期や程度は地域によって異なっていた[105]。 |

Health problems feet of a Chinese woman in an isolation hospital in Mauritius Feet of a Chinese woman, showing the effect of foot-binding The most common problem with bound feet was infection. Despite the amount of care taken in regularly trimming the toenails, they would often in-grow, becoming infected and causing injuries to the toes. Sometimes, for this reason, the girl's toenails would be peeled back and removed altogether. The tightness of the binding meant that the circulation in the feet was faulty, and the circulation to the toes was almost cut off, so injuries to the toes were unlikely to heal and were likely to gradually worsen and lead to infected toes and rotting flesh. The necrosis of the flesh would initially give off a foul odour. Later the smell may have come from various microorganisms that colonized the folds.[106] Most of the women receiving treatment did not go out often and were disabled.[44] If the infection in the feet and toes entered the bones, it could cause them to soften, which could result in toes dropping off. This was seen as a benefit because the feet could then be bound even more tightly. Girls whose toes were more fleshy would sometimes have shards of glass or pieces of broken tiles inserted within the binding next to her feet and between her toes to cause injury and introduce infection deliberately.[107] Disease inevitably followed infection, meaning that death from septic shock could result from foot binding, and a surviving girl was more at risk of medical problems as she grew older. It is thought that as many as 10% of girls may have died from gangrene and other infections owing to foot binding.[108] At the beginning of the binding, many of the foot bones would remain broken, often for years. However as the girl grew older the bones would begin to heal. Even after the foot bones had healed, they were prone to rebreaking repeatedly, especially when the girl was in her teenage years and her feet were still soft. Bones in the girls' feet would often be deliberately broken again to further change the size or shape of the feet. This was especially the case with the girl's toes, which were broken several times since small toes were especially desirable.[109] Older women were more likely to break hips and other bones in falls, since they could not balance properly on their feet, and were less able to rise to their feet from a sitting position.[110] Other issues that may have arisen from foot binding included paralysis and muscular atrophy.[104] By the turn of the century foot binding had been exposed in photographs, X-rays and detailed textual descriptions. These scientific investigations detailed how foot binding deformed the leg, covered the skin with cracks and sores and altered the posture.[111] There is also some evidence that points to some older women in select rural areas experiencing higher levels of osteoporosis morbidities.[112] |

健康問題 モーリシャスの隔離病院にいる中国人女性の足 中国人の女性の足。纏足の影響が表れている 纏足で最もよくある問題は感染症だった。爪を定期的に切るのに細心の注意を払っていたにもかかわらず、爪はしばしば肉に食い込み、感染して足の指に傷を負 わせた。このため、少女の爪は剥がされて完全に除去されることもあった。締め付けの強い纏足は足の血行を阻害し、つま先への血流はほぼ遮断された。そのた め、つま先の傷は治りにくく、次第に悪化してつま先の感染や肉が腐る状態を招きやすかった。壊死した肉は当初、悪臭を放った。後にその臭いは、ひだに繁殖 した様々な微生物に起因していた可能性がある[106]。治療を受ける女性のほとんどは外出せず、身体障害者であった。[44] 足や足の指の感染が骨に侵入すると、骨が軟化して指が脱落することがあった。これは利点と見なされた。なぜなら、そうすれば足をさらに強く縛ることが可能 になるからだ。足の指が肉付きの良い少女には、足の横や指の間にガラス片や割れた瓦の破片を意図的に挟み込み、傷を負わせて感染を引き起こすことがあっ た。[107] 感染は必然的に病気を引き起こし、纏足による敗血症性ショック死の可能性もあった。生き残った少女も成長するにつれ健康問題のリスクが高まった。纏足が原 因で壊疽やその他の感染により、最大10%の少女が死亡したと考えられている。[108] 縛り始めの段階では、足の骨の多くが折れたまま、しばしば何年も放置された。しかし少女が成長するにつれ、骨は癒合し始める。足の骨が癒合した後でさえ、 特に十代で足がまだ柔らかい時期には、繰り返し折れやすかった。足の骨は、足のサイズや形をさらに変えるために、意図的に再び折られることが多かった。特 に小指は理想的な形状とされるため、何度も骨折させられることが多かった。[109] 年配の女性は足でバランスを保てず、座った状態から立ち上がるのも困難だったため、転倒時に股関節や他の骨を骨折するリスクが高かった。[110] 纏足から生じるその他の問題には、麻痺や筋萎縮も含まれた。世紀の変わり目までに、写真やX線、詳細な記述を通じて纏足が暴露された。これらの科学的調査 は、纏足が脚をどのように変形させ、皮膚にひび割れやただれを生じさせ、姿勢を変化させるかを明らかにした。また、特定の農村地域の高齢女性において、骨 粗鬆症の罹患率が高いことを示す証拠もある。 |

| Views and interpretations There are many interpretations to the practice of foot binding. The interpretive models used include fashion (with the Chinese customs somewhat comparable to the more extreme examples of Western women's fashion such as the Wasp waist), seclusion (sometimes evaluated as morally superior to the gender mingling in the West), perversion (the practice imposed by men with sexual perversions), inexplicable deformation, child abuse and extreme cultural traditionalism. In the late 20th century some feminists introduced positive overtones, reporting that it gave some women a sense of mastery over their bodies and pride in their beauty.[113] Beauty and erotic appeal  Bound feet were considered beautiful and even erotic. Before foot binding was practised in China, admiration for small feet already existed as demonstrated by the Tang dynasty tale of Ye Xian written around 850 by Duan Chengshi. This tale of a girl who lost her shoe and then married a king who sought the owner of the shoe as only her foot was small enough to fit the shoe contains elements of the European story of Cinderella and is thought to be one of its antecedents.[114][115] For many, the bound feet were an enhancement to a woman's beauty and made her movement more dainty,[116] and a woman with perfect lotus feet was likely to make a more prestigious marriage.[117][118] Even while not much was written on the subject of foot binding prior to the latter half of the 19th century, the writings that were done on this topic, particularly by educated men, frequently alluded to the erotic nature and appeal of bound feet in their poetry.[118] The desirability varies with the size of the feet—the perfect bound feet and the most desirable (called 'golden lotuses') would be around 3 Chinese inches (around 10 cm or 4 in) or smaller, while those larger were called 'silver lotuses' (4 Chinese inches—around 13 cm or 5.1 in) or 'iron lotuses' (5 Chinese inches—around 17 cm or 6.7 in—or larger, and thus the least desirable for marriage).[119] Therefore people had greater expectations for foot binding brides.[120] The belief that foot binding made women more desirable to men is widely used as an explanation for the spread and persistence of foot binding.[121] Some also considered bound feet to be intensely erotic. Some men preferred never to see a woman's bound feet, so they were always concealed within tiny 'lotus shoes' and wrappings. According to Robert van Gulik, the bound feet were also considered the most intimate part of a woman's body. In erotic art of the Qing period where the genitalia may be shown, the bound feet were never depicted uncovered.[122] Howard Levy, however, suggests that the barely revealed bound foot may also only function as an initial tease.[121] An effect of the bound feet was the lotus gait, the tiny steps and swaying walk of a woman whose feet had been bound. Women with such deformed feet avoided placing weight on the front of the foot and tended to walk predominantly on their heels.[103] Walking on bound feet necessitated bending the knees slightly and swaying to maintain proper movement and balance, a dainty walk that was also considered to be erotically attractive to some men.[123] Some men found the smell of the bound feet attractive and some also apparently believed that bound feet would cause layers of folds to develop in the vagina, and that the thighs would become sensuously heavier and the vagina tighter.[124] The psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud considered foot binding to be a "perversion that corresponds to foot fetishism",[125] and that it appeased male castration anxiety.[44] |

見解と解釈 纏足の慣習には多くの解釈がある。用いられる解釈モデルには、ファッション(中国の慣習は西洋女性のファッションにおける極端な例、例えばワスプウエスト とやや比較可能)、隔離(西洋の男女混交よりも道徳的に優れていると評価されることもある)、倒錯(性的倒錯を持つ男性によって強要された慣習)、説明の つかない変形、児童虐待、極端な文化的伝統主義などがある。20世紀後半には一部のフェミニストが肯定的な側面を指摘し、この慣習が一部の女性に身体への 支配感や美への誇りを与えたと報告している[113]。 美と性的魅力  纏足は美しく、さらには性的魅力があると見なされた。 中国で纏足が実践される以前から、小さな足への憧れは存在していた。段成式が850年頃に記した唐代の物語『茧仙』がその証左である。靴を失った少女が、 その靴に合う小さな足を持つ者を探して王となった王と結婚するというこの物語は、ヨーロッパのシンデレラ物語の要素を含み、その前身の一つと考えられてい る。[114][115] 多くの人にとって、纏足は女性の美しさを増し、その動きをより優雅なものにした[116]。完璧な蓮の足を持つ女性は、より高位の結婚を勝ち取る可能性が 高かった。[117][118] 19世紀後半まで纏足に関する文献は少なかったが、特に教養ある男性によるこの主題の著作では、詩の中でしばしば縛られた足の官能性と魅力に言及してい た. [118] その魅力は足の大きさによって異なる。完璧な纏足で最も望ましいとされる「黄金の蓮」は3中国寸(約10cm)以下であり、それより大きいものは「銀の 蓮」 (中国寸で4寸=約13cm/5.1インチ)あるいは「鉄蓮華」(中国寸で5寸=約17cm/6.7インチ以上。結婚相手としては最も望ましくないサイ ズ)と呼ばれた。[119] したがって人民は、纏足の花嫁に対してより大きな期待を抱いた。[120] 纏足が女性を男性にとってより魅力的にするという信念は、纏足の普及と持続を説明する根拠として広く用いられている。[121] また、纏足を非常に官能的と考える者もいた。一部の男性は女性の纏足を決して見たくないと望み、それらは常に小さな「蓮の靴」と包帯の中に隠されていた。 ロバート・ファン・グリクによれば、纏足は女性の身体で最も親密な部分と見なされていた。清代の官能芸術では性器が描かれることもあったが、纏足が露わに 描かれることは決してなかった。[122] しかしハワード・レヴィは、わずかに見える纏足は単なる最初の挑発として機能するだけかもしれないと示唆している。[121] 纏足の効果として蓮の歩みがある。これは足を纏われた女性が取る、小さな歩幅で揺れるような歩き方だ。変形した足を持つ女性は足の前部に体重をかけず、主 に踵で歩く傾向があった[103]。纏足で歩くには膝を軽く曲げ、揺れながら適切な動きとバランスを保つ必要があった。この可憐な歩き方は、一部の男性に とって性的魅力とみなされていた。[123] 纏足の匂いを魅力的に感じる男性もいれば、纏足が膣に幾重ものひだを生じさせ、太ももが官能的に重くなり、膣が締まるという説を信じる者もいた。 [124] 精神分析学者ジークムント・フロイトは、纏足を「足フェティシズムに対応する倒錯」と見なし、[125] それが男性の去勢不安を和らげると考えた。[44] |

Role of Confucianism A woman with her feet unwrapped During the Song dynasty, the status of women declined.[44] A common argument is that it was the result of the revival of Confucianism as neo-Confucianism and that, in addition to promoting the seclusion of women and the cult of widow chastity, it also contributed to the development of foot binding.[126] According to Robert van Gulik, the prominent Song Confucian scholar Zhu Xi stressed the inferiority of women as well as the need to keep men and women strictly separate.[127] It was claimed by Lin Yutang among others, probably based on an oral tradition, that Zhu Xi also promoted foot binding in Fujian as a way of encouraging chastity among women; that by restricting their movement, it would help keep men and women separate.[126] However, historian Patricia Ebrey suggests that this story might be fictitious,[128] and argued that the practice arose so as to emphasize the gender distinction during a period of societal change in the Song dynasty.[44][129] Some Confucian moralists in fact disapproved of the erotic associations of foot binding, and unbound women were also praised.[130] The Neo-Confucian Cheng Yi was said to be against foot binding and his family and descendants did not bind their feet.[131][132] Modern Confucian scholars such as Tu Weiming also dispute any causal link between neo-Confucianism and foot binding,[133] as Confucian doctrine prohibits mutilation of the body as people should not "injure even the hair and skin of the body received from mother and father". It is argued that such injunction applies less to women, rather it is meant to emphasize the sacred link between sons and their parents. Furthermore, it is argued that Confucianism institutionalized the family system in which women are called upon to sacrifice themselves for the good of the family, a system that fostered such practice.[134] Historian Dorothy Ko proposed that foot binding may be an expression of the Confucian ideals of civility and culture in the form of correct attire or bodily adornment, and that foot binding was seen as a necessary part of being feminine as well as being civilized. Foot binding was often classified in Chinese encyclopedia as clothing or a form of bodily embellishment rather than mutilation. One from 1591, for example, placed foot binding in a section on "Female Adornments" that included hairdos, powders, and ear piercings. According to Ko, the perception of foot binding as a civilized practice may be evinced from a Ming dynasty account that mentioned a proposal to "entice [the barbarians] to civilize their customs" by encouraging foot binding among their womenfolk.[135] The practice was carried out only by women on girls, and it served to emphasize the distinction between male and female, an emphasis that began from an early age.[136][137] Anthropologist Fred Blake argued that the practice of foot binding was a form of discipline undertaken by women themselves, and perpetuated by women on their daughters, so as to inform their daughters of their role and position in society, and to support and participate in the neo-Confucian way of being civilized.[134] |

儒教の役割 足を包帯で巻いていない女性 宋代において、女性の地位は低下した。[44] 一般的な見解では、これは新儒教としての儒教復興の結果であり、女性の閉門や寡婦貞操の崇拝を促進しただけでなく、纏足の発展にも寄与したとされる。 [126] 著名な宋代儒学者である朱熹は、女性の劣等性を強調するとともに、男女の厳格な分離の必要性を説いたと、ロバート・ファン・グリックは述べている。 [127] 林語堂らによって、おそらく口承伝承に基づいて、朱熹が福建省で女性の貞操を促す手段として纏足を推進したとも主張されている。つまり、女性の移動を制限 することで、男女の分離を維持するのに役立つという考えだ。[126] しかし歴史家パトリシア・エブリーは、この説は虚構の可能性があると示唆している[128]。また纏足の慣行は、宋代という社会変革期に性別区別を強調す るために生まれたと論じている[44][129]。 実際、一部の儒教道徳家は纏足の性的連想を非難し、足を縛らない女性も称賛された[130]。新儒家の程頤は纏足に反対したと言われ、その家族や子孫は足 を縛らなかった[131]。[132] 杜維明ら現代の儒学者も、新儒教と纏足の因果関係を否定している[133]。儒教の教義は身体の損傷を禁じており、「父母から授かった身体の毛髪や皮膚す ら傷つけてはならない」と説くからだ。この戒めは女性には適用されにくく、むしろ息子と親の聖なる絆を強調する意図があると論じられている。さらに、儒教 が家族制度を制度化したことで、女性が家族のために自己を犠牲にすることを求められるようになり、この制度が纏足の慣行を助長したとも主張されている。 [134] 歴史家ドロシー・コーは、纏足は正しい服装や身体装飾という形で、儒教の礼儀正しさや教養という理想を表現したものであり、纏足は女性らしさと教養ある人 間であるための必要不可欠な要素と見なされていたと提案している。中国の百科事典では、纏足は身体の損傷ではなく、衣服や身体装飾の一形態として分類され ることが多かった。例えば1591年の事典では、纏足は髪型、化粧、耳の穴あけを含む「女性の装飾品」の項目に分類されていた。コによれば、纏足を文明的 慣行と捉える認識は、明代の記録に「(蛮族を)誘い出してその風俗を文明化させる」ため、女性たちに纏足を奨励する提案があったことからも窺えるという [135]。この慣行は女性だけが少女に対して行い、幼い頃から男女の区別を強調する役割を果たした。[136][137] 人類学者フレッド・ブレイクは、纏足は女性自身が行う一種の規律であり、娘たちに社会の役割と立場を教え、新儒教的な文明化への道を支え参加させるため に、女性によって娘たちへ受け継がれたと論じた。[134] |

| Feminist perspective Foot binding is considered an oppressive practice against women who were victims of a sexist culture.[138][139] It is also widely seen as a form of violence against women.[140][141][142] Bound feet rendered women dependent on their families, particularly the men, as they became largely restricted to their homes.[143] Thus, the practice ensured that women were much more reliant on their husbands.[144] The early Chinese feminist Qiu Jin, who underwent the painful process of unbinding her own bound feet, attacked foot binding and other traditional practices. She argued that women, by retaining their small bound feet, made themselves subservient by imprisoning themselves indoors. She believed that women should emancipate themselves from oppression, that girls could ensure their independence through education, and that they should develop new mental and physical qualities fitting for the new era.[145][59] The end of the practice of foot binding is seen as a significant event in the process of female emancipation in China,[146] and a major event in the history of Chinese feminism.[citation needed] In the late 20th century, some feminists have pushed back against the prevailing Western critiques of foot binding, arguing that the presumption that foot binding was done solely for the sexual pleasure of men denies the agency and cultural influence of women.[147][37] Other interpretations Some scholars such as Laurel Bossen and Hill Gates reject the notion that bound feet in China were considered more beautiful, or that it was a means of male control over women, a sign of class status, or a chance for women to marry well (in general, bound women did not improve their class position by marriage). Foot binding is believed to have spread from elite women to civilian women and there were large differences in each region. The body and labor of unmarried daughters belonged to their parents, thereby the boundaries between work and kinship for women were blurred.[76] They argued that foot binding was an instrumental means to reserve women to handwork, and can be seen as a way by mothers to tie their daughters down, train them in handwork, and keep them close at hand.[148][149] This argument has been challenged by John Shepherd in his book Footbinding as Fashion, and shows there was no connection between handicraft industries and the proportion of women bound in Hebei.[150] Foot binding was common when women could do light industry, but where women were required to do heavy farm work they often did not bind their feet because it hindered physical work. These scholars argued that the coming of the mechanized industry at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, such as the introduction of industrial textile processes, resulted in a loss of light handwork for women, removing a reason to maintain the practice. Mechanization resulted in women who worked at home facing a crisis.[35] Coupled with changes in politics and people's consciousness, the practice of foot binding disappeared in China forever after two generations.[76][148] More specifically, the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing (after the First Opium War) opened five cities as treaty ports where foreigners could live and trade. This led to foreign citizens residing in the area, where many proselytized as Christian missionaries. These foreigners condemned many long-standing Chinese cultural practices like foot binding as "uncivilized" — marking the beginning of the end for the centuries-long practice.[111] It has been argued that while the practice started out as a fashion, it persisted because it became an expression of Han identity after the Mongols invaded China in 1279, and later the Manchus' conquest in 1644, as it was then practised only by Han women.[clarification needed][136] During the Qing dynasty, attempts were made by the Manchus to ban the practice but failed, and it has been argued the attempts at banning may have in fact led to a spread of the practice among Han Chinese in the 17th and 18th centuries.[151] John Shepherd provides a critical review of the evidence cited for the notion that foot binding was an expression of "Han identity" and rejects this interpretation.[152] |

フェミニストの視点 纏足は、性差別的な文化の犠牲となった女性に対する抑圧的な慣習と見なされている。[138][139] また、女性に対する暴力の一形態として広く認識されている。[140][141][142] 縛られた足は、女性を家庭、特に男性に依存させる結果となった。なぜなら、彼女たちは主に家の中に閉じ込められるようになったからだ。[143] したがって、この慣習は女性が夫に大きく依存することを保証したのである。[144] 中国の初期フェミニストである秋瑾は、自ら縛られた足を解く苦痛の過程を経験した後、纏足やその他の伝統的慣習を批判した。彼女は、女性が小さな縛られた 足を維持することで、自らを屋内に閉じ込め従属的な立場に追いやっていると主張した。女性は抑圧から自らを解放すべきであり、少女たちは教育を通じて自立 を確保でき、新時代にふさわしい新たな精神的・身体的資質を育むべきだと信じていた。[145][59] 纏足の慣習の終焉は、中国における女性解放の過程における重要な出来事と見なされている[146]。また中国フェミニズム史における主要な出来事でもある [出典必要]。 20世紀後半、一部のフェミニストは、纏足が男性の性的快楽のためだけに行われたとする前提が女性の主体性と文化的影響力を否定していると主張し、西洋における纏足批判の主流に反論した[147]。[37] その他の解釈 ローレル・ボッセンやヒル・ゲイツら一部の学者は、中国の纏足がより美しいとされたという見解、あるいは男性による女性支配の手段、階級地位の象徴、良縁 を得る機会(一般的に纏足を施した女性が結婚によって階級的地位を向上させることはなかった)といった解釈を否定している。纏足は上流階級の女性から庶民 の女性へ広がったと考えられており、地域ごとに大きな差異があった。未婚の娘の身体と労働力は親に属するため、女性にとって労働と親族関係の境界は曖昧で あった。[76] 彼らは纏足が女性を手仕事に縛り付ける手段であり、母親が娘を束縛し手仕事を訓練させ、身近に置く方法と見なせると主張した。[148][149] この主張はジョン・シェパードの著書『ファッションとしての纏足』で反論され、河北省における手工業と女性の纏足比率に相関関係はなかったと示されてい る。[150] 女性が軽工業に従事できる地域では纏足が一般的だったが、重労働を強いられる農業地域では、身体労働の妨げとなるため纏足をしない場合が多かった。これら の研究者は、19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけての機械化産業の到来(工業的紡績工程の導入など)が、女性の手軽な手仕事機会を奪い、纏足慣行を維持する 理由を消滅させたと論じた。機械化は家庭で働く女性たちに危機をもたらした[35]。政治や人々の意識の変化と相まって、纏足の慣習は中国で二世代を経て 永久に消滅した[76][148]。具体的には、1842年の南京条約(第一次アヘン戦争後)により、外国人が居住・貿易できる条約港として五都市が開か れた。これにより外国人が居住し、多くの者がキリスト教宣教師として布教活動を行った。これらの外国人は纏足を含む中国の伝統的慣習を「未開」と非難し、 この数世紀にわたる慣習の終焉の始まりを告げたのである。[111] この慣習は当初はファッションとして始まったが、1279年のモンゴルによる中国侵攻、そして1644年の満州族による征服後、漢民族のアイデンティティ の表現として定着し、その後漢民族の女性のみが実践するようになったため継続したと主張されている。[説明が必要][136] 清王朝時代、満州族はこの慣習を禁止しようとしたが失敗した。むしろ禁止の試みが17~18世紀に漢民族の間でこの慣習を広める結果になった可能性がある と指摘されている。[151] ジョン・シェパードは、纏足が「漢民族のアイデンティティ」の表現だったとする主張の根拠となる証拠を批判的に検証し、この解釈を退けている。[152] |

| In popular culture This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The bound foot has played a prominent part in many media works, both Chinese and non-Chinese, modern and traditional.[153] These depictions are sometimes based on observation or research and sometimes on rumors or supposition. Sometimes, as in the case of Pearl Buck's The Good Earth (1931), the accounts are relatively neutral or empirical, implying respect for Chinese culture.[a] Sometimes, the accounts seem intended to rouse like-minded Chinese and foreign opinion to abolish the custom, and sometimes the accounts imply condescension or contempt for China.[154] Quoted in the Jin Ping Mei (c. 1610): "displaying her exquisite feet, three inches long and no wider than a thumb, very pointed and with high insteps."[155] Anna Bunina mentions the custom in her 1810 fable "Пекинское ристалище" (The Peking Stadium), which describes a Chinese woman attempting to run a race and barely finishing the boys' course, yet still getting applause for the effort. Bunina used the custom as an allegory to her own difficulties in getting recognition as a poet.[156] Flowers in the Mirror (1837) by Ju-Chen Li includes chapters set in the "Country of Women", where men bear children and have bound feet.[157] The Three-Inch Golden Lotus (1994) by Feng Jicai[158] presents a satirical picture of the movement to abolish the practice, which is seen as part of Chinese culture. In the film The Inn of the Sixth Happiness (1958), Ingrid Bergman portrays Gladys Aylward, a British missionary to China who is assigned as a foreigner the task by a local Mandarin to unbind the feet of young women, an unpopular order that the civil government had failed to fulfill. Later, the children are able to escape troops by walking miles to safety. Ruthanne Lum McCunn wrote a biographical novel, Thousand Pieces of Gold (1981, adapted into a 1991 film), about Polly Bemis, a Chinese American pioneer woman. It describes her feet being bound and later unbound when she needed to help her family with farm labor. Emily Prager's short story "A Visit from the Footbinder", from her collection of short stories of the same name (1982), describes the last few hours of a young Chinese girl's childhood before the professional footbinder arrives to initiate her into the adult woman's life of beauty and pain.[159] Jung Chang's family autobiography Wild Swans presents the story of Yu-Fang, the grandmother, who had bound feet from the age of two. Lisa Loomer's play The Waiting Room (1994) deals with themes of body modification. One of the three main characters is an 18th-century Chinese woman who arrives in a modern hospital waiting room, seeking medical help for complications resulting from her bound feet. She describes the foot-binding process, as well as the physical and psychological harm her bound feet have caused.[160] Lensey Namioka's novel Ties that Bind, Ties that Break (1999) follows a girl named Ailin in China who refuses to have her feet bound, which comes to affect her future.[161] Lisa See's novel Snow Flower and the Secret Fan (2005) is about two Chinese girls who are destined to be friends. The novel is based upon the sacrifices women make to be married and includes the two girls being forced into getting their feet bound. The book was adapted into a 2011 film directed by Wayne Wang. The Filipino horror film Feng Shui and its sequel Feng Shui 2 feature a ghost of a foot-bound woman inhabits a bagua and cursed those who holds the item. Sieglinde Sullivan from Black Butler had her feet bound when she was young as part of the "Emerald Witch" hoax invented by the German military. Lisa See's novel China Dolls (2014) describes Chinese family traditions including foot binding. Xiran Jay Zhao's novel Iron Widow (2021) is set in a futuristic world inspired by medieval China that still practices foot binding. The main character, Wu Zetian, had her feet bound in childhood and suffers from chronic pain due to it. Edward Rutherfurd's novel China: An Epic Novel, is set in late Qing Dynasty China, when foot binding was still common practice among Han Chinese in the north. Bright Moon, the daughter of a main character Mei-Ling, has her feet bound to increase her chances of a good marriage, and the practice is described in detail. The character soon resents that she has her feet bound, as it causes her severe pain, and stops her from participating in many activities. In episode 9 of the anime series The Apothecary Diaries, a servant girl was found dead in a moat. After an autopsy, it was found that she had her feet bound. |

ポピュラー・カルチャーにおいて この節は検証可能な情報源を要する。信頼できる情報源をこの節に追加し、記事の改善に協力してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。(2022年4月)(このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) 纏足は、中国内外を問わず、現代・伝統を問わず、多くのメディア作品で重要な役割を果たしてきた。[153] こうした描写は観察や研究に基づく場合もあれば、噂や推測に基づく場合もある。パール・バックの『大地』(1931年)のように、比較的中立的あるいは実 証的な記述もあり、中国文化への敬意が示されている。[a] 時には、同調する中国内外の世論を喚起してこの慣習を廃止させようとする意図が感じられる記述もあり、また時には中国に対する見下した態度や軽蔑がにじむ 記述もある。[154] 『金瓶梅』(約1610年)に引用:「その絶妙な足を披露した。長さは三寸、幅は親指ほどで、先は鋭く、甲は高く張っていた。」[155] アンナ・ブニーナは1810年の寓話『ペキンスコエ・リスタリシエ(北京競技場)』でこの習俗に触れている。中国人の女性が人種に挑戦し、男子のコースを かろうじて完走するも、その努力が称賛される様子が描かれている。ブニーナはこの習俗を、詩人としての評価を得る困難を象徴する寓話として用いた。 [156] 李如姝の『鏡中花』(1837年)には「女国」を舞台とした章があり、男性が子を産み、纏足を施す描写がある。[157] 馮季才の『三寸金蓮』(1994年)[158]は、中国文化の一部と見なされるこの慣習を廃止する運動を風刺的に描いている。 映画『第六の幸福の宿』(1958年)では、イングリッド・バーグマンがグラディス・アイルワードを演じている。中国で宣教師として活動した彼女は、現地 の官吏から外国人として若い女性の足を解く任務を命じられる。これは民政当局が達成できなかった不人気な命令だった。後に子供たちは軍隊から逃れるため、 何マイルも歩いて安全な場所へたどり着く。 ルースアン・ラム・マッカンは伝記小説『千金の足』(1981年、1991年に映画化)を執筆した。中国系アメリカ人開拓者ポリー・ベミスを題材とし、彼女の足が纏足された後、農作業で家族を助ける必要が生じた際に解かれた経緯を描いている。 エミリー・プラガーの短編小説「纏足師の訪問」(1982年、同名短編集収録)は、プロの纏足師が訪れ、美と苦痛に満ちた大人の女性の人生へ導かれる直前、若い中国人少女の子供時代の最後の数時間を描いている。 張戎の家族自伝『野生の白鳥』は、2歳の時から纏足されていた祖母・玉芳の物語を提示する。 リサ・ルーマーの戯曲『待合室』(1994年)は身体改造をテーマとする。三人の主人公の一人は18世紀の中国人女性で、纏足に起因する合併症の治療を求めて現代の病院待合室に現れる。彼女は纏足の過程と、纏足がもたらした身体的・精神的被害を語る。[160] レンズィー・ナミオカ著『縛る絆、断つ絆』(1999年)は、中国の少女アイリンが纏足を拒み、それが彼女の将来に影響を与える物語である。[161] リサ・シーの小説『雪の花と秘密の扇』(2005年)は、運命的に友情を結ぶ二人の中国人の少女が主人公だ。この小説は女性が結婚するために払う犠牲を題 材としており、二人の少女が強制的に纏足される場面も含まれている。この本は2011年にウェイン・ワン監督によって映画化された。 フィリピン製ホラー映画『風水』とその続編『風水2』では、八角形の宝物箱に宿る纏足の女性の亡霊が登場し、その品を持つ者を呪う。 『黒執事』のジーグリンデ・ザリンドは、ドイツ軍が仕組んだ「エメラルドの妖術師」の偽装工作の一環として幼少期に足を縛られた。 リサ・シーの小説『チャイナ・ドールズ』(2014年)は、纏足を含む中国家族の伝統を描いている。 シラン・ジェイ・チャオの小説『アイアン・ウィドウ』(2021年)は、中世中国に着想を得た未来世界を舞台に、纏足が依然として行われている。主人公の武則天は幼少期に足を縛られ、そのせいで慢性的な苦悩に苦しんでいる。 エドワード・ラザフォードの小説『チャイナ:叙事詩的長編小説』は、清朝末期の中国を舞台としている。当時、北方の漢民族の間では纏足がまだ一般的だっ た。主人公メイリンの娘ブライト・ムーンは、良縁を得る可能性を高めるために足を縛られ、その過程が詳細に描写されている。その娘はすぐに纏足を恨むよう になる。激しい痛みを伴い、多くの活動に参加できなくなるからだ。 アニメ『薬師日記』の第9話では、堀で死んだ女中が見つかる。検死の結果、彼女の足が縛られていたことが判明する。 |

| Artificial cranial deformation Body modification Corset controversy Foot Emancipation Society Hobble skirt Women in ancient and imperial China |

人工的な頭蓋変形 身体改造 コルセット論争 足解放協会 ホブルスカート 古代中国と帝国時代の女性 |

| References and further reading Berg, Eugene E., MD, "Chinese Footbinding". Radiology Review – Orthopaedic Nursing 24, no. 5 (September/October) 66–67 Berger, Elizabeth, Liping Yang, and Wa Ye. "Foot binding in a Ming dynasty cemetery near Xi'an, China". International journal of paleopathology 24 (2019): 79–88. Bossen, Laurel; Gates, Hill (2017). Bound Feet, Young Hands: Tracking the Demise of Footbinding in Village China. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804799553. Brown, Melissa J., and Damian Satterthwaite-Phillips. "Economic correlates of footbinding: Implications for the importance of Chinese daughters' labor". PLOS ONE 13.9 (2018): e0201337. online Brown, Melissa J.; Bossen, Laurel; Gates, Hill; Satterthwaite-Phillips, Damian (2012). "Marriage Mobility and Footbinding in Pre-1949 Rural China: A Reconsideration of Gender, Economics, and Meaning in Social Causation". The Journal of Asian Studies. 71 (4): 1035–1067. doi:10.1017/S0021911812001271. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 23357433. Brown, Melissa J. (2020). "Footbinding in Economic Context: Rethinking the Problems of Affect and the Prurient Gaze". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 80 (1): 179–214. doi:10.1353/jas.2020.0007. S2CID 235848627. Review article. Cassel, Susie Lan (2007). "'...the Binding Altered Not only My Feet but My Whole Character': Footbinding and First-World Feminism in Chinese American Literature". Journal of Asian American Studies. Vol. 10 (1): 31–58. Project Muse and Ethnic Newswatch. Fan Hong (1997) Footbinding, Feminism and Freedom. London: Frank Cass Gates, Hill (2014). Footbinding and Women's Labor in Sichuan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-52592-3. Hershatter, Gail (2018). Women and China's Revolutions. Ebookcentral: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781442215702. Hughes, Roxane. Ambivalent Orientalism: Footbinding in Chinese American History, Culture and Literature. Diss. Université de Lausanne, Faculté des lettres, 2017. Ko, Dorothy (2002). Every Step a Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23284-6. Ko, Dorothy (12 December 2005). Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-94140-3. Ko, Dorothy (2008). "Perspectives on Foot-binding" (PDF). ASIANetwork Exchange. XV (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2011. Ping, Wang. Aching for Beauty: Footbinding in China. New York: Anchor Books, 2002. Shepherd, John R. "The Qing, the Manchus, and Footbinding: Sources and Assumptions Under Scrutiny." Frontiers of History in China 11.2 (2016): 279–322. Shepherd, John R. (2018). Footbinding as Fashion. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295744407. van Gulik, Robert Hans (1961). Sexual life in ancient China: A Preliminary Survey of Chinese Sex and Society from Ca. 1500 B.C. Till 1644 A.D. Brill. ISBN 9004039171. The Virtual Museum of The City of San Francisco, "Chinese Foot Binding – Lotus Shoes" Attributution This article incorporates text from Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8, by James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray, a publication from 1916, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from The religions of China: Confucianism and Tâoism described and compared with Christianity, by James Legge, a publication from 1880, now in the public domain in the United States. |

参考文献および追加文献(さらに読む) Berg, Eugene E., MD, 「中国の纏足」. Radiology Review – Orthopaedic Nursing 24, no. 5 (9月/10月号) 66–67 Berger, Elizabeth, Liping Yang, and Wa Ye. 「中国西安近郊の明代墓地における纏足」. 国際古病理学雑誌 24 (2019): 79–88. ボッセン、ローレル; ゲイツ、ヒル (2017). 『縛られた足、若い手:中国農村における纏足の終焉を追って』. スタンフォード大学出版局. ISBN 9780804799553. ブラウン、メリッサ・J.、ダミアン・サタースウェイト=フィリップス。「纏足の経済的相関関係:中国における娘の労働力の重要性への示唆」。PLOS ONE 13.9 (2018): e0201337. オンライン ブラウン、メリッサ・J.;ボッセン、ローレル;ゲイツ、ヒル;サタースウェイト=フィリップス、ダミアン (2012). 「1949年以前の中国農村における婚姻移動と纏足:社会的因果関係における性別、経済、意味の再考」. The Journal of Asian Studies. 71 (4): 1035–1067. doi:10.1017/S0021911812001271. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 23357433. ブラウン、メリッサ・J. (2020). 「経済的文脈における纏足:情動の問題と好色的な視線の再考」. 『ハーバード・ジャーナル・オブ・アジアン・スタディーズ』. 80 (1): 179–214. doi:10.1353/jas.2020.0007. S2CID 235848627. 総説記事。 キャッセル、スージー・ラン(2007)。「『…纏足は私の足だけでなく性格全体を変えた』:中国系アメリカ文学における纏足と第一世界フェミニズム」。 『アジア系アメリカ研究ジャーナル』。第10巻第1号:31–58頁。Project Muse and Ethnic Newswatch. ファン・ホン(1997)『纏足、フェミニズム、そして自由』ロンドン:フランク・キャス ゲイツ、ヒル(2014)。『四川における纏足と女性の労働』ラウトレッジ。ISBN 978-0-415-52592-3。 ハーシャター、ゲイル(2018)。『女性と中国の革命』。Ebookcentral: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers。ISBN 9781442215702。 ヒューズ、ロクサン。『両義的なオリエンタリズム:中国系アメリカ人の歴史・文化・文学における纏足』。博士論文。ローザンヌ大学文学部、2017年。 コー、ドロシー(2002)。『一歩ごとに蓮の花:縛られた足のための靴』。カリフォルニア大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-520-23284-6。 コー、ドロシー(2005年12月12日)。『シンデレラの姉妹たち:纏足の修正主義的歴史』。カリフォルニア大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-520-94140-3。 コー、ドロシー(2008)。「纏足に関する視点」(PDF)。『ASIANetwork Exchange』XV巻3号。2011年12月3日にオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。 王平. 『美への渇望:中国の纏足』. ニューヨーク:アンカーブックス, 2002. シェパード, ジョン・R. 「清朝、満州族、そして纏足:検証される史料と仮定」. 『中国歴史研究の最前線』11.2 (2016): 279–322. シェパード、ジョン・R. (2018). 『ファッションとしての纏足』. シアトル: ワシントン大学出版局. ISBN 9780295744407. ファン・グリク、ロバート・ハンス (1961). 『古代中国の性生活:紀元前1500年頃から1644年までの中国性と社会の予備的調査』. ブリル. ISBN 9004039171。 サンフランシスコ市のバーチャル博物館、「中国の纏足 – 蓮の靴」 出典 この記事は、1916年に出版され、現在米国でパブリックドメインとなっている、ジェームズ・ヘイスティングス、ジョン・アレクサンダー・セルビー、ルイス・ハーバート・グレイによる『宗教と倫理の百科事典』第8巻のテキストを組み込んでいる。 この記事は、1880年に出版され、現在米国でパブリックドメインとなっている、ジェームズ・レッグ著『中国の宗教:キリスト教と比較した儒教と道教の説明』のテキストを組み込んでいる。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foot_binding |

★日本植民地統治の台湾における纏足廃絶運動

国家撮影文化センター、日本統治時代の台湾における女性の「纏足」廃止運動に関するオンライン写真展(2025.10.31)

国 家撮影文化中心(以下、国家撮影文化センターとする)は、国立台湾師範大学名誉教授の呉文星氏に委託し、同センターが所蔵する25点の写真作品をもとに、 オンライン写真展「#女性の纏足と日本統治時代の纏足廃止運動」を企画した。この写真展は「伝統的な纏足をした女性」と「日本統治時代の纏足廃止運動」の 2つをサブテーマとし、かつて女性たちを束縛した「纏足」の歴史を振り返り、台湾が近代社会へと進む中で生まれた「纏足」廃止運動」と、それに伴う考え方 や価値観の変化などについて理解を深められるようになっている。

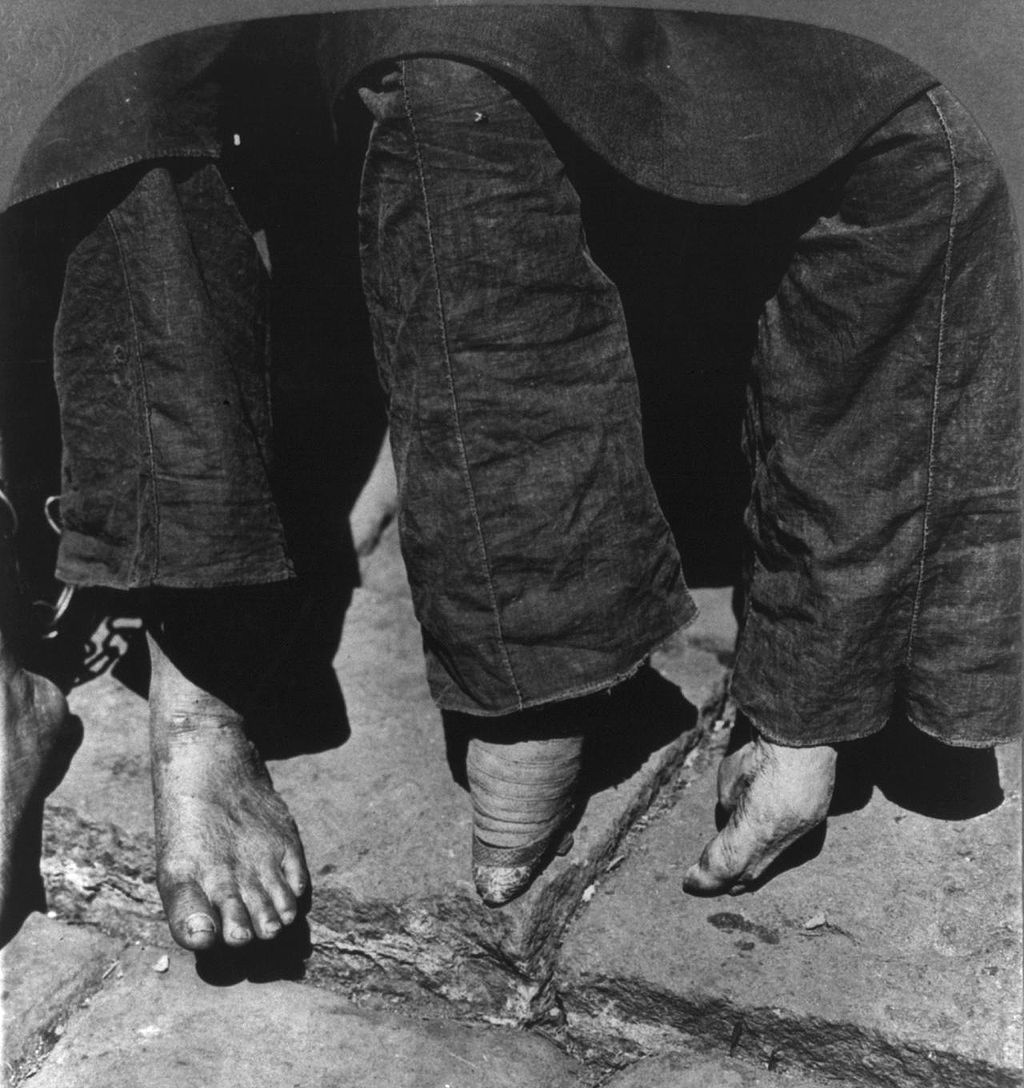

★ 国家撮影文化センターが、日本統治時代の台湾における女性の「纏足」廃止運動に関するオンライン写真展を公開した。台湾では1910年代、「纏足」や「辮 髪」の廃止を促す運動が各地に広がった。1915年8月時点で、台湾全土で「纏足」を解いた人は48万人余り、「纏足」を続けている人は18万人だったと いう。写真は「纏足」の継続が許された老婦人。(国家撮影文化センター)

「纏 足(てんそく)」は、華人社会で数百年にわたり続いた身体文化の現象であり、男性が支配的で特権的な地位を占める社会システムにおいて、女性の身体に対す る支配と美に対する規範を象徴するものであった。日本統治時代、日本人はこれを「悪習」と見なして強制的に取り締まり、「纏足」廃止運動を推進した。これ により、女性たちは次第に身体的束縛から解放され、近代化とジェンダー意識の変化の時代を迎えることとなった。/ 国家撮影文化中心(以下、国家撮影文化センターとする)は、国立台湾師範大学名誉教授の呉文星氏に委託し、同センターが所蔵する25点の写真作品をもと に、オンライン写真展「女性の纏足と日本統治時代の纏足廃止運動」を企画した。この写真展は「伝統的な纏足をした女性」と「日本統治時代の纏足廃止運動」 の2つをサブテーマとし、かつて女性たちを束縛した「纏足」の歴史を振り返り、台湾が近代社会へと進む中で生まれた「纏足」廃止運動」と、それに伴う考え 方や価値観の変化などについて理解を深められるようになっている。

伝統的な纏足をした女性

台 湾では17世紀、明の遺臣・鄭成功がオランダの勢力を駆逐し、台湾南部を拠点に鄭氏政権を確立して以来、中国大陸の福建や広東から多くの華人が海を渡って やってきた。こうした移民の中で最も多かったのは福建省の漳州や泉州(いわゆる漳泉地方)の出身者だった。女性の足を縛って小さく見せる「纏足」の風習は 五代十国の「南唐」の時代には、すでに漳泉地方に広まっていた。この地方では、奴婢や乞食、貧困層を除くほとんどの女性が「纏足」を行っていた。19世紀 末、清朝統治時代の台湾では、およそ80万人以上の女性が「纏足」を行っていたという。一方、広東出身の客家(ハッカ)の女性たちは、女性が家事や農作業 を担う伝統があったため、あまり「纏足」を行わなかった。

日本統治時代の纏足廃止運動

1895

年、台湾総督府は台湾での統治を始めて間もなく『台湾開化良箴』を発刊し、台湾の人々の間に広まっていた「纏足」、「辮髪」、「アヘン吸飲」などを、衛生

や健康を害する「悪習」とみなし、段階的に禁止する措置を講じた。具体的には学校教育や新聞・雑誌などを通じて、「纏足」や「辮髪」をやめることが奨励さ

れた。1900年頃から台北では「纏足廃止」を提唱する団体が現れ、その風潮はやがて台湾全域に広がった。1910年代中期以降、総督府は保甲制度を活用

して「纏足」や「辮髪」の廃止運動を本格的に推進。その結果、約48万人以上の女性が「纏足」をやめた。こうした変化は、台湾の人々の思想や価値観、生活

習慣にも影響を与え、新しい服飾文化や近代的風潮が生まれ、ひいては女性の社会参加と経済発展の促進にもつながった。/

「纏足」の風習を排除したことと新式の学校教育の普及は、台湾社会において女性たちを身体的あるいは道徳的束縛から解き放つきっかけとなった。こうして

1921年10月17日、林献堂、蒋渭水、蔡培火、頼和など当時の若者らが台北・大稲埕の静修女学校で「台湾文化協会」を設立し、台湾文化の啓蒙運動を推

進した。現在台湾では10月17日を「台湾文化の日」として記念している。

https://ncpi.ntmofa.gov.tw/News_Content_OnlineExhibitionLit.aspx?n=8008&s=244356

★ひとつの解釈(池田光穂)

「纏足廃止」運動の集合写真には、「祝、我、自然」とあります——纒足は自然(未開)と文化(文明)の二項対立からみると前者に属するとな?これは中國と日本という日本側(植民地支配者)がもつ二項対立と二重写しになる。これは端的に極東アジアにおける世紀初頭のFGM問題だったということがわかる.

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099