金融化

Financialization

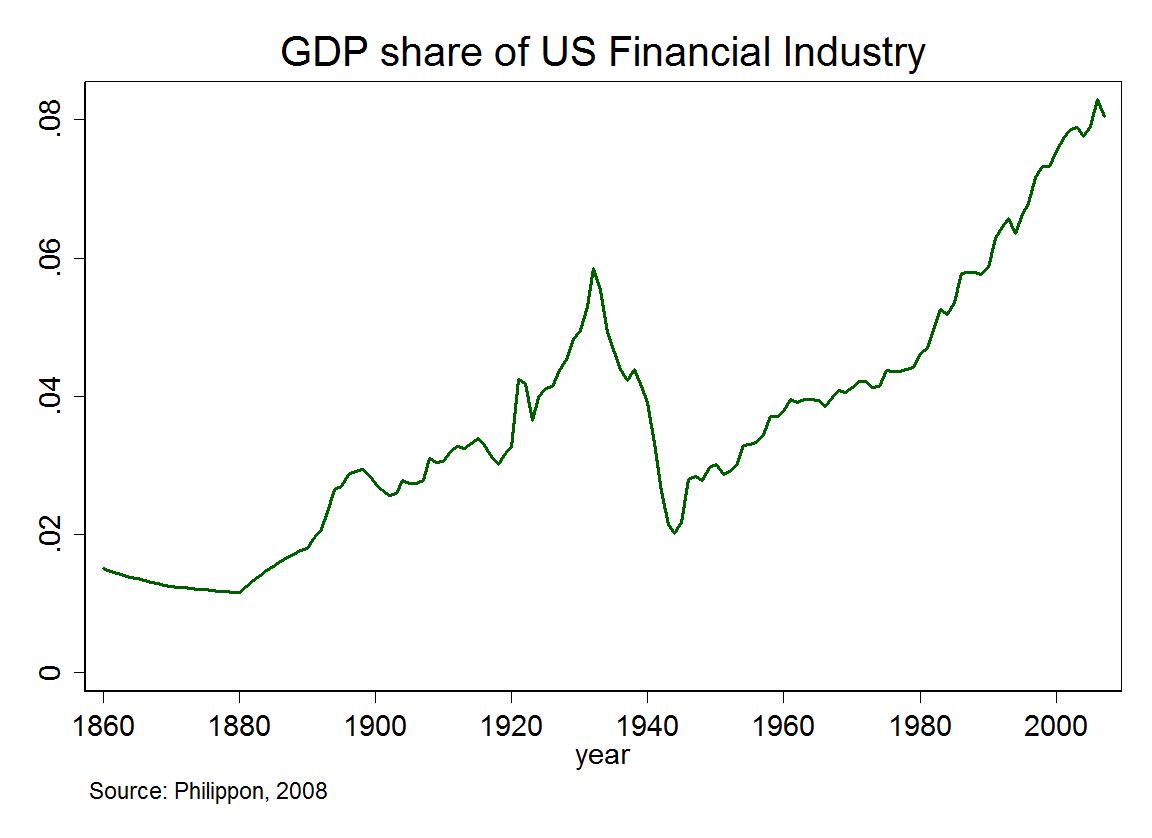

Share

in GDP of US financial sector from 1860 to 2008[1]

☆金融化(英国英語ではfinancialisation)とは、1980年代から現在に至るまでの金融資本主義の発展を説明するために用いられる用語である。この期間において、負債資本比率が上昇し、金融サービスが他のセクターと比較して国民所得に占める割合が増加した。

金融化とは、金融商品の仲介を通じて交換が促進される経済的プロセスを指す。金融化により、実物商品・サービス・リスクが通貨と容易に交換可能となり、人民が資産や収入の流れを合理化することが容易になる。

金融化は、金融サービスが経済の第三次産業に属するという点で、工業経済からサービス経済への移行と結びついている。

| Financialization (or

financialisation in British English) is a term sometimes used to

describe the development of financial capitalism during the period from

1980 to the present, in which debt-to-equity ratios increased and

financial services accounted for an increasing share of national income

relative to other sectors. Financialization describes an economic process by which exchange is facilitated through the intermediation of financial instruments. Financialization may permit real goods, services, and risks to be readily exchangeable for currency and thus make it easier for people to rationalize their assets and income flows. Financialization is tied to the transition from an industrial economy to a service economy in that financial services belong to the tertiary sector of the economy. |

金融化(英国英語ではfinancialisation)とは、

1980年代から現在に至るまでの金融資本主義の発展を説明するために用いられる用語である。この期間において、負債資本比率が上昇し、金融サービスが他

のセクターと比較して国民所得に占める割合が増加した。 金融化とは、金融商品の仲介を通じて交換が促進される経済的プロセスを指す。金融化により、実物商品・サービス・リスクが通貨と容易に交換可能となり、人 民が資産や収入の流れを合理化することが容易になる。 金融化は、金融サービスが経済の第三次産業に属するという点で、工業経済からサービス経済への移行と結びついている。 |

| Specific academic approaches Various definitions, focusing on specific aspects and interpretations, have been used: Greta Krippner of the University of Michigan writes that financialization refers to a "pattern of accumulation in which profit making occurs increasingly through financial channels rather than through trade and commodity production."[2] In the introduction to the 2005 book Financialization and the World Economy, editor Gerald A. Epstein wrote that some scholars have insisted on a much narrower use of the term: the ascendancy of shareholder value as a mode of corporate governance, or the growing dominance of capital market financial systems over bank-based financial systems. Pierre-Yves Gomez and Harry Korine, in their 2008 book Entrepreneurs and Democracy: A Political Theory of Corporate Governance, have identified a long-term trend in the evolution of corporate governance of large corporations and have shown that financialization is one step in this process. Thomas Marois, looking at the big emerging markets, defines "emerging finance capitalism" as the current phase of accumulation, characterized by "the fusion of the interests of domestic and foreign financial capital in the state apparatus as the institutionalized priorities and overarching social logic guiding the actions of state managers and government elites, often to the detriment of labor."[3] According to Gerald A. Epstein, "Financialization refers to the increasing importance of financial markets, financial motives, financial institutions, and financial elites in the operation of the economy and its governing institutions, both at the national and international levels."[4] Marxian Economist Elliot Goodell Ugalde defines financialization as the creation of fictitious capital through the growing divergence between the exchange value and the real market price of assets, particularly housing. This process inflates asset values beyond their basis in socially necessary labor, transforming them into speculative instruments rather than goods fulfilling essential needs. The result is a distortion where market prices are driven by profit-seeking behavior rather than the actual utility or accessibility of the asset, exacerbating inequality and undermining the stability of the broader economic system.[5] Financialization may be defined as "the increasing dominance of the finance industry in the sum total of economic activity, of financial controllers in the management of corporations, of financial assets among total assets, of marketized securities and particularly equities among financial assets, of the stock market as a market for corporate control in determining corporate strategies, and of fluctuations in the stock market as a determinant of business cycles" (Dore 2002). More popularly, however, financialization is understood to mean the vastly expanded role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors, and financial institutions in the operation of domestic and international economies. Sociological and political interpretations have also been made. In his 2006 book, American Theocracy: The Peril and Politics of Radical Religion, Oil, and Borrowed Money in the 21st Century, American writer and commentator Kevin Phillips presents financialization as "a process whereby financial services, broadly construed, take over the dominant economic, cultural, and political role in a national economy" (268). Phillips considers that the financialization of the US economy follows the same pattern that marked the beginning of the decline of Habsburg Spain in the 16th century, the Dutch trading empire in the 18th century, and the British Empire in the 19th century (it is also worth pointing out that the true final step in each of these historical economies was collapse): ... the leading economic powers have followed an evolutionary progression: first, agriculture, fishing, and the like, next commerce and industry, and finally, finance. Several historians have elaborated on this point. Brooks Adams contended that "as societies consolidate, they pass through a profound intellectual change. Energy ceases to vent through the imagination and takes the form of capital."[This quote needs a citation] Jean Cushen explores how the workplace outcomes associated with financialization render employees insecure and angry.[6] |

特定の学術的アプローチ 様々な定義が用いられており、特定の側面や解釈に焦点を当てている: ミシガン大学のグレタ・クリップナーは、金融化とは「利益創出が貿易や商品生産ではなく、金融経路を通じてますます行われる蓄積のパターン」を指すと記し ている。[2] 2005年刊行の『金融化と世界経済』の序文で、編集者ジェラルド・A・エプスタインは、一部の学者がこの用語をはるかに狭義に用いることを主張している と記している。すなわち、企業統治の様式としての株主価値の台頭、あるいは銀行ベースの金融システムに対する資本市場金融システムの支配力の増大を指すと いう。ピエール=イヴ・ゴメズとハリー・コリンは2008年の著書『起業家と民主主義:企業統治の政治理論』において、大企業の企業統治の進化における長 期的な傾向を特定し、金融化がこの過程の一段階であることを示した。 トマ・マロワは新興市場を分析し、「新興金融資本主義」を現在の蓄積段階と定義する。その特徴は「国内外の金融資本の利害が国家機構内で融合し、国家管理 者や政府エリートの行動を導く制度化された優先事項かつ包括的な社会的論理となること。これは往々にして労働者の不利益を伴う」[3]。 ジェラルド・A・エプスタインによれば、「金融化とは、金融市場、金融的動機、金融機関、金融エリートが、国家レベルおよび国際レベルの両方で、経済とその統治機関の運営において重要性を増す現象を指す」[4]。 マルクス主義経済学者エリオット・グッデル・ウガルデは、金融化を、資産(特に住宅)の交換価値と実質市場価格の乖離拡大を通じて虚構資本が創出される過 程と定義する。この過程は資産価値を社会的に必要な労働量を超えた水準まで膨張させ、必需品を充足する商品ではなく投機的手段へと変質させる。結果として 市場価格は資産の実用性や入手可能性ではなく利潤追求行動によって駆動される歪みが生じ、不平等を深刻化させ広範な経済システムの安定性を損なう。[5] 金融化は「経済活動全体における金融産業の支配力増大、企業経営における財務管理者の支配力増大、総資産に占める金融資産の割合増大、金融資産の中でも市 場化された証券(特に株式)の割合増大、企業戦略決定における企業支配の市場としての株式市場の支配力増大、そして景気循環の決定要因としての株式市場の 変動性の増大」と定義できる(Dore 2002)。 しかしより一般的には、金融化とは、国内および国際経済の運営において、金融的動機、金融市場、金融関係者、金融機関の役割が大幅に拡大したことを意味すると理解されている。 社会学的・政治学的解釈もなされている。アメリカ人作家・評論家ケヴィン・フィリップスは2006年の著書『アメリカ神政政治:21世紀における急進的宗 教、石油、借金による危険と政治』で、金融化を「広義に解釈した金融サービスが、国民経済において支配的な経済的・文化的・政治的役割を引き継ぐ過程」と 提示している(268頁)。フィリップスは、米国経済の金融化が16世紀ハプスブルク家のスペイン、18世紀オランダ貿易帝国、19世紀大英帝国の衰退期 と同一のパターンを辿ると見なしている(なお、これらの歴史的経済体制の真の最終段階は崩壊であった点も指摘しておく価値がある): ...主要経済大国は進化的な進展をたどってきた。まず農業や漁業など、次に商業と工業、そして最後に金融である。複数の歴史家がこの点を詳述している。 ブルックス・アダムズは「社会が統合されるにつれ、深い知的変革を経験する。エネルギーは想像力を通じて発散することをやめ、資本の形態をとる」と主張し た[この引用には出典が必要] ジャン・クシェンは、金融化に伴う職場環境の変化が従業員に不安と怒りを生み出す仕組みを考察している。[6] |

| Roots In the American experience, increased financialization occurred concomitant with the rise of neoliberalism and the free-market doctrines of Milton Friedman and the Chicago School of Economics in the late twentieth century. Various academic economists of that period worked out ideological and theoretical rationalizations and analytical approaches to facilitate the increased deregulation of financial systems and banking. In a 1998 article, Michael Hudson discussed previous economists who saw the problems that resulted from financialization.[7] Problems were identified by John A. Hobson (financialization enabled Britain's imperialism), Thorstein Veblen (it acts in opposition to rational engineers), Herbert Somerton Foxwell (Britain was not using finance for industry as well as Europe), and Rudolf Hilferding (Germany was surpassing Britain and the United States in banking that supports industry). At the same 1998 conference in Oslo, Erik S. Reinert and Arno Mong Daastøl in "Production Capitalism vs. Financial Capitalism" provided an extensive bibliography on past writings, and prophetically asked[8] In the United States, probably more money has been made through the appreciation of real estate than in any other way. What are the long-term consequences if an increasing percentage of savings and wealth, as it now seems, is used to inflate the prices of already existing assets - real estate and stocks - instead of creating new production and innovation? |

ルーツ アメリカの経験において、金融化の進展は、20世紀後半に新自由主義とミルトン・フリードマンやシカゴ学派の自由市場原理が台頭したことに伴って起こっ た。当時の様々な経済学者たちは、金融システムと銀行業の規制緩和を促進するための、イデオロギー的・理論的な正当化と分析手法を構築した。 1998年の記事で、マイケル・ハドソンは金融化がもたらす問題を予見した過去の経済学者たちについて論じている。[7] ジョン・A・ホブソン(金融化が英国の帝国主義を可能にした)、ソーステイン・ヴェブレン(金融化は合理的な技術者に対立する)、ハーバート・ソマート ン・フォックスウェル(英国は欧州ほど産業に金融を活用していなかった)、ルドルフ・ヒルファーディング(ドイツは産業を支える銀行業で英国と米国を凌駕 していた)らが問題を指摘した。 同じ1998年のオスロ会議で、エリック・S・ライナートとアルノ・モン・ダーストルは「生産資本主義対金融資本主義」において過去の文献に関する広範な書誌を提供し、予言的に問いかけた[8] 米国では、おそらく不動産価格の上昇によって、他のいかなる方法よりも多くの富が生み出されてきた。貯蓄と富の割合が増加するにつれ、それが新たな生産や 革新を生み出すのではなく、既存資産(不動産や株式)の価格を膨らませるために使われるようになった場合、長期的な結果はどうなるのか? |

| Financial turnover compared to gross domestic product This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages) This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) Other financial markets exhibited similarly explosive growth. Trading in US equity (stock) markets grew from $136.0 billion (or 13.1% of US GDP) in 1970 to $1.671 trillion (or 28.8% of U.S. GDP) in 1990. In 2000, trading in US equity markets was $14.222 trillion (144.9% of GDP). Most of the growth in stock trading has been directly attributed to the introduction and spread of program trading. According to the March 2007 Quarterly Report from the Bank for International Settlements, page 24: Trading on the international derivatives exchanges slowed in the fourth quarter of 2006. The combined turnover of interest rate, currency, and stock index derivatives fell by 7% to $431 trillion between October and December 2006. Thus, derivatives trading—mostly futures contracts on interest rates, foreign currencies, Treasury bonds, and the like—had reached a level of $1,200 trillion, or $1.2 quadrillion, a year. By comparison, the US GDP in 2006 was $12.456 trillion. |

金融取引高と国内総生産の比較 この節には複数の問題点がある。改善に協力するか、トークページで議論してほしい。(これらのメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングについて学ぶ) この節は検証可能な情報源をさらに必要としている。(2024年11月) 他の金融市場も同様に爆発的な成長を示した。米国株式市場の取引高は、1970年の1,360億ドル(米国GDPの13.1%)から、1990年には1兆 6,710億ドル(米国GDPの28.8%)に増加した。2000年には米国株式市場の取引高は14.222兆ドル(GDPの144.9%)に達した。株 式取引の成長の大部分は、プログラム取引の導入と普及に直接起因するとされている。 国際決済銀行(BIS)2007年3月四半期報告書24ページによれば: 国際デリバティブ取引所の取引高は2006年第4四半期に減速した。金利・通貨・株価指数デリバティブの合計取引高は2006年10月から12月にかけて7%減少し、431兆ドルとなった。 したがって、デリバティブ取引(主に金利、外国通貨、国債などの先物契約)は年間1200兆ドル、すなわち1.2京ドルの水準に達した。比較すると、2006年の米国GDPは12.456兆ドルであった。 |

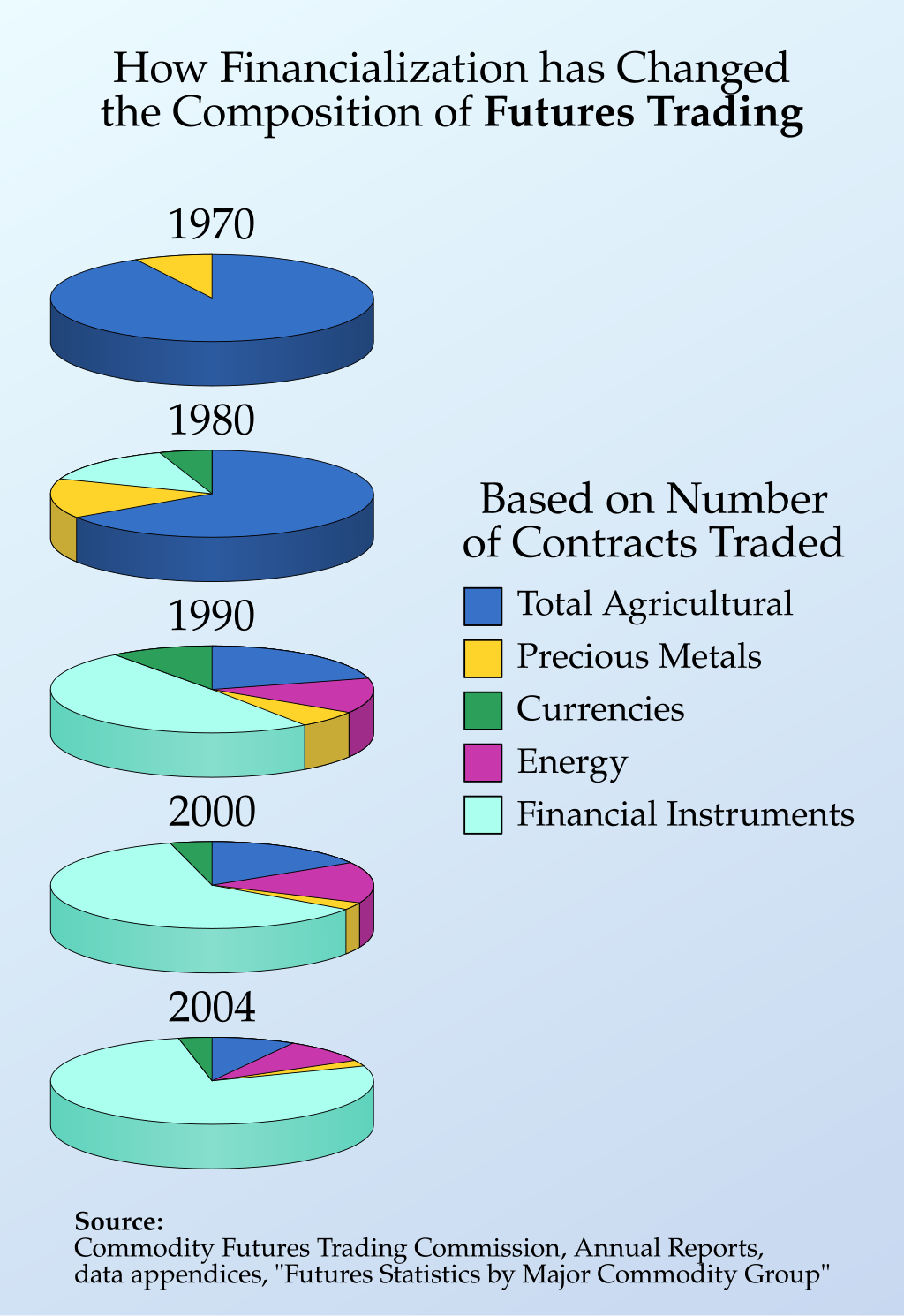

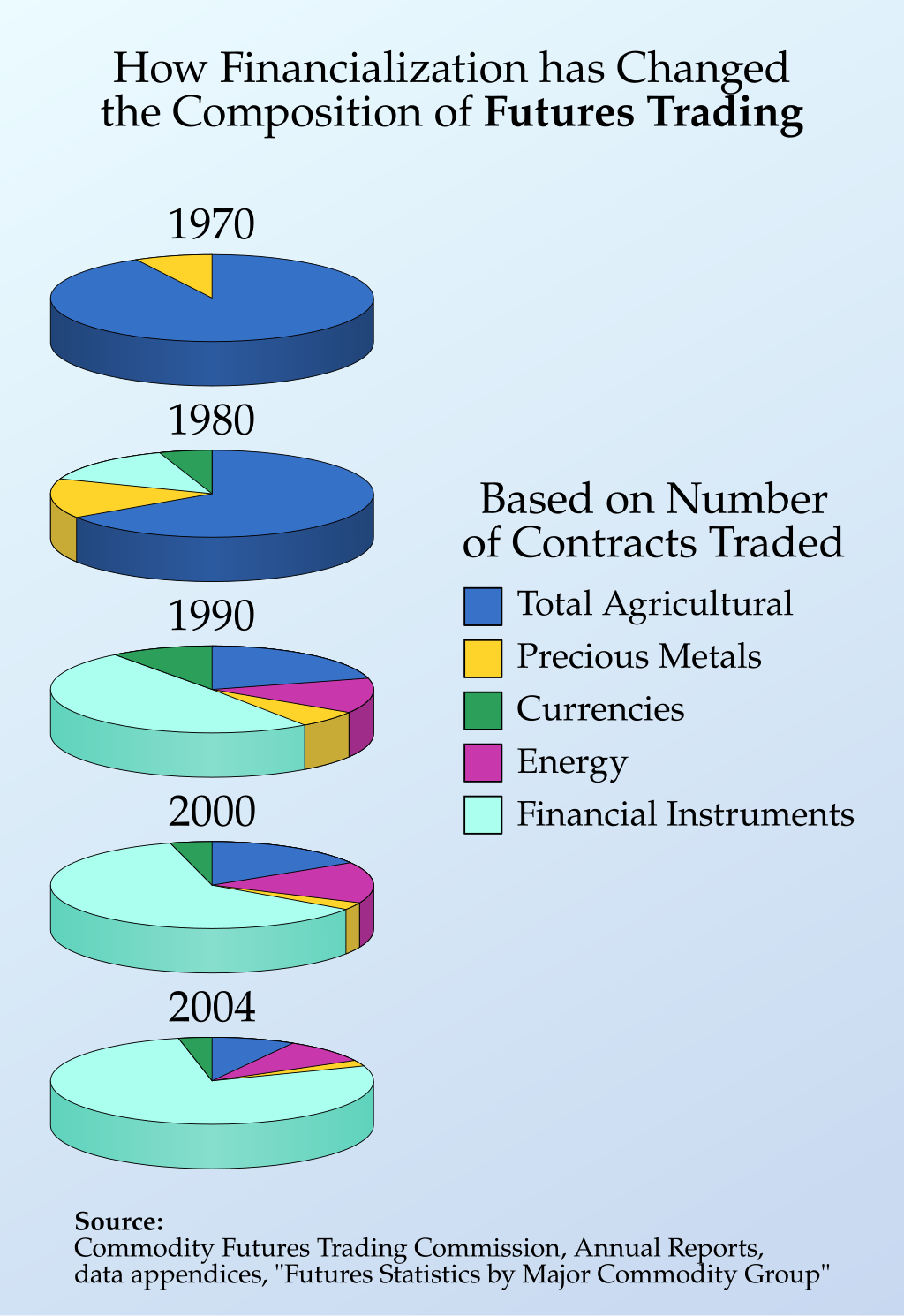

Futures markets The data for turnover in the futures markets in 1970, 1980, and 1990 is based on the number of contracts traded, which is reported by the organized exchanges, such as the Chicago Board of Trade, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and the New York Commodity Exchange, and compiled in data appendices of the Annual Reports of the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. The pie charts below show the dramatic shift in the types of futures contracts traded from 1970 to 2004. For a century after organized futures exchanges were founded in the mid-19th century, all futures trading was solely based on agricultural commodities. However, after the end of the gold-backed fixed-exchange-rate system in 1971, contracts based on foreign currencies began to be traded. After the deregulation of interest rates by the Bank of England and then the US Federal Reserve in the late 1970s, futures contracts based on various bonds and interest rates began to be traded. The result was that financial futures contracts—based on such things as interest rates, currencies, or equity indices—came to dominate the futures markets. The dollar value of turnover in the futures markets is found by multiplying the number of contracts traded by the average value per contract for 1978 to 1980, which was calculated in research by the American Council of Life Insurers (ACLI) in 1981. The figures for earlier years were estimated on the computer-generated exponential fit of data from 1960 to 1970, with 1960 set at $165 billion, half the 1970 figure, based on a graph accompanying the ACLI data, which showed that the number of futures contracts traded in 1961 and earlier years was about half the number traded in 1970. According to the ALCI data, the average value of interest-rate contracts is around ten times that of agricultural and other commodities, while the average value of currency contracts is twice that of agricultural and other commodities. (Beginning in mid-1993, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange itself began to release figures of the nominal value of contracts traded at the CME each month. In November 1993, the CME boasted that it had set a new monthly record of 13.466 million contracts traded, representing a dollar value of $8.8 trillion. By late 1994, this monthly value had doubled. On January 3, 1995, the CME boasted that its total volume for 1994 had jumped by 54% to 226.3 million contracts traded, worth nearly $200 trillion. Soon thereafter, the CME ceased to provide a figure for the dollar value of contracts traded.) Futures contracts are "contracts to buy or sell a very common homogeneous item at a future date for a specific price." The nominal value of a futures contract is wildly different from the risk involved in engaging in that contract. Consider two parties who engage in a contract to exchange 5,000 bushels of wheat at $8.89 per bushel on December 17, 2012. The nominal value of the contract would be $44,450 (5,000 bushels x $8.89). But what is the risk? For the buyer, the risk is that the seller will not be able to deliver the wheat on the stated date. This means the buyer must purchase the wheat from someone else; this is known as the "spot market." Assume that the spot price for wheat on December 17, 2012, is $10 per bushel. This means the cost of purchasing the wheat is $50,000 (5,000 bushels x $10). So, the buyer would have lost $5,550 ($50,000 less $44,450), or the difference in the cost between the contract price and the spot price. Furthermore, futures are traded via exchanges, which guarantee that if one party reneges on its end of the bargain, (1) that party is blacklisted from entering into such contracts in the future, and (2) the injured party is insured against the loss by the exchange. If the loss is so large that the exchange cannot cover it, then the members of the exchange make up the loss. Another mitigating factor to consider is that a commonly traded liquid asset, such as gold, wheat, or the S&P 500 stock index, is extremely unlikely to have a future value of $0; thus, the counter-party risk is limited to something substantially less than the nominal value. |

先物市場 1970年、1980年、1990年の先物市場における取引高のデータは、シカゴ商品取引所、シカゴ・マーカンタイル取引所、ニューヨーク商品取引所など の組織化された取引所が報告し、米国商品先物取引委員会の年次報告書のデータ付録にまとめられた取引契約数に基づいている。下記の円グラフは、1970年 から2004年にかけて取引される先物契約の種類が劇的に変化したことを示している。 19世紀半ばに組織化された先物取引所が設立されてから1世紀の間、全ての先物取引は農産物のみを基盤としていた。しかし、1971年に金本位制に基づく 固定為替相場制度が終焉を迎えると、外国通貨を基盤とする契約の取引が始まった。1970年代後半にイングランド銀行、次いで米連邦準備制度理事会 (FRB)が金利規制を撤廃すると、各種債券や金利を原資産とする先物契約の取引が始まった。その結果、金利・通貨・株価指数などを原資産とする金融先物 契約が先物市場を支配するようになった。 先物市場の取引高のドル換算額は、取引された契約数に1978年から1980年までの契約平均価値を乗じて算出される。この平均価値は1981年に米国生 命保険協会(ACLI)の研究で算出されたものである。それ以前の年の数値は、1960年から1970年のデータを基にコンピューターで生成した指数関数 的な近似値で推定された。1960年の数値は1650億ドルと設定され、これは1970年の数値の半分である。これはACLIデータに添付されたグラフに 基づいている。同グラフは、1961年およびそれ以前の年に取引された先物契約数が、1970年の取引数の約半分であったことを示していた。 ALCIデータによれば、金利契約の平均価値は農産物その他の商品契約の約10倍、通貨契約の平均価値は農産物その他の商品契約の2倍である。(1993 年半ば以降、シカゴ・マーカンタイル取引所(CME)自体が毎月取引される契約の名目価値を発表し始めた。1993年11月、CMEは取引高が1,346 万6千枚、ドル換算で8兆8千億ドルという月間新記録を達成したと発表した。1994年末までに、この月間取引高は倍増した。1995年1月3日、CME は1994年の総取引高が54%増の2億2630万枚に達し、取引総額は約200兆ドルに迫ったと発表した。その後まもなく、CMEは取引契約のドル建て 総額の数値提供を停止した。 先物契約とは「特定の価格で、将来の期日に極めて一般的な均質商品を売買する契約」である。先物契約の名目価値は、その契約に関わるリスクとは大きく異な る。例えば、2012年12月17日に5,000ブッシェル(約155トン)の小麦を1ブッシェルあたり8.89ドルで交換する契約を結んだ2者を考えて みよう。この契約の名目価値は44,450ドル(5,000ブッシェル×8.89ドル)となる。しかしリスクは何か。買い手にとってのリスクは、売り手が 指定日に小麦を納入できないことだ。これは買い手が他者から小麦を購入せねばならないことを意味し、これを「現物市場」と呼ぶ。2012年12月17日の 小麦現物価格が1ブッシェルあたり10ドルだと仮定しよう。すると小麦購入コストは50,000ドル(5,000ブッシェル×10ドル)となる。したがっ て買い手は5,550ドル(50,000ドル-44,450ドル)の損失、すなわち契約価格とスポット価格のコストの差額を被ることになる。さらに、先物 は取引所を通じて取引される。取引所は、契約の一方が約束を破った場合、(1)その当事者を将来の契約締結から排除する(ブラックリスト入りさせる)、 (2)被害を受けた当事者を損失から保護する(取引所が補償する)ことを保証している。損失が取引所の補償能力を超えるほど大きい場合、取引所の会員がそ の損失を補填する。考慮すべき別の緩和要因として、金や小麦、S&P 500株価指数など流動性の高い資産は、先物価値が0ドルになる可能性が極めて低い。したがって、カウンターパーティリスクは名目価値より大幅に低い水準 に限定される。 |

| Accelerated growth of the finance sector The financial sector is a key industry in developed economies, in which it represents a sizable share of the GDP and an important source of employment. Financial services (banking, insurance, investment, etc.) have been for a long time a powerful sector of the economy in many economically developed countries. Those activities have also played a key role in facilitating economic globalization. |

金融セクターの急速な成長 金融セクターは先進国経済における基幹産業であり、GDPに占める割合が大きく、重要な雇用源となっている。金融サービス(銀行、保険、投資など)は長年 にわたり、多くの経済先進国において強力な経済セクターであった。これらの活動は経済のグローバル化を促進する上で重要な役割も果たしてきた。 |

| Early 20th century history in the United States As early as the beginning of the 20th Century, a small number of financial sector firms have controlled the lion's share of wealth and power of the financial sector. The notion of an American "financial oligarchy" was discussed as early as 1913. In an article entitled "Our Financial Oligarchy," Louis Brandeis, who in 1913 was appointed to the United States Supreme Court, wrote that, "We believe that no methods of regulation ever have been or can be devised to remove the menace inherent in private monopoly and overwhelming commercial power" that is vested in U.S. finance sector firms.[9] There were early investigations of the concentration of the economic power of the U.S. finance sector, such as the Pujo Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives, which in 1912 found that control of credit in America was concentrated in the hands of a small group of Wall Street firms that were using their positions to accumulate vast economic power.[10] When in 1911 Standard Oil was broken up as an illegal monopoly by the U.S. government, the concentration of power in the U.S. financial sector was unaltered.[11] Key players of financial sector firms also had a seat at the table in devising the Central Bank of the United States. In November 1910, the five heads of the country's most powerful finance sector firms gathered for a secret meeting on Jekyll Island with U.S. Senator Nelson W. Aldrich and Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury Department A. Piatt Andrew and laid the plans for the U.S. Federal Reserve System.[12] |

20世紀初頭のアメリカ合衆国の歴史 20世紀の初めには、ごく少数の金融企業が金融業界の富と権力の大部分を掌握していた。アメリカの「金融寡頭制」という概念は、早くも1913年に議論さ れていた。1913年に米国最高裁判事に任命されたルイス・ブランダイスは「我々の金融寡頭制」と題する論文で、米国金融セクター企業に帰属する「私的独 占と圧倒的な商業力に内在する脅威を除去する規制手法は、過去にも未来にも存在し得ない」と記した。[9] 米国金融セクターの経済力集中については早期から調査が行われていた。例えば1912年の米国下院プジョー委員会は、米国の信用支配がウォール街の一握り の企業に集中しており、それらが自らの地位を利用して膨大な経済力を蓄積していると結論づけた。[10] 1911年にスタンダード・オイル社が違法独占として米国政府により解体された際、米国金融セクターにおける権力の集中は変わらなかった。 金融セクターの主要企業も、米国中央銀行の設立計画に参画していた。1910年11月、国内で最も影響力のある金融セクターの5社のトップが、ネルソン・ W・オルドリッチ上院議員、A・ピアット・アンドルー財務次官補とジキル島で秘密会合を開き、連邦準備制度の設立計画を立てたのである。[12] |

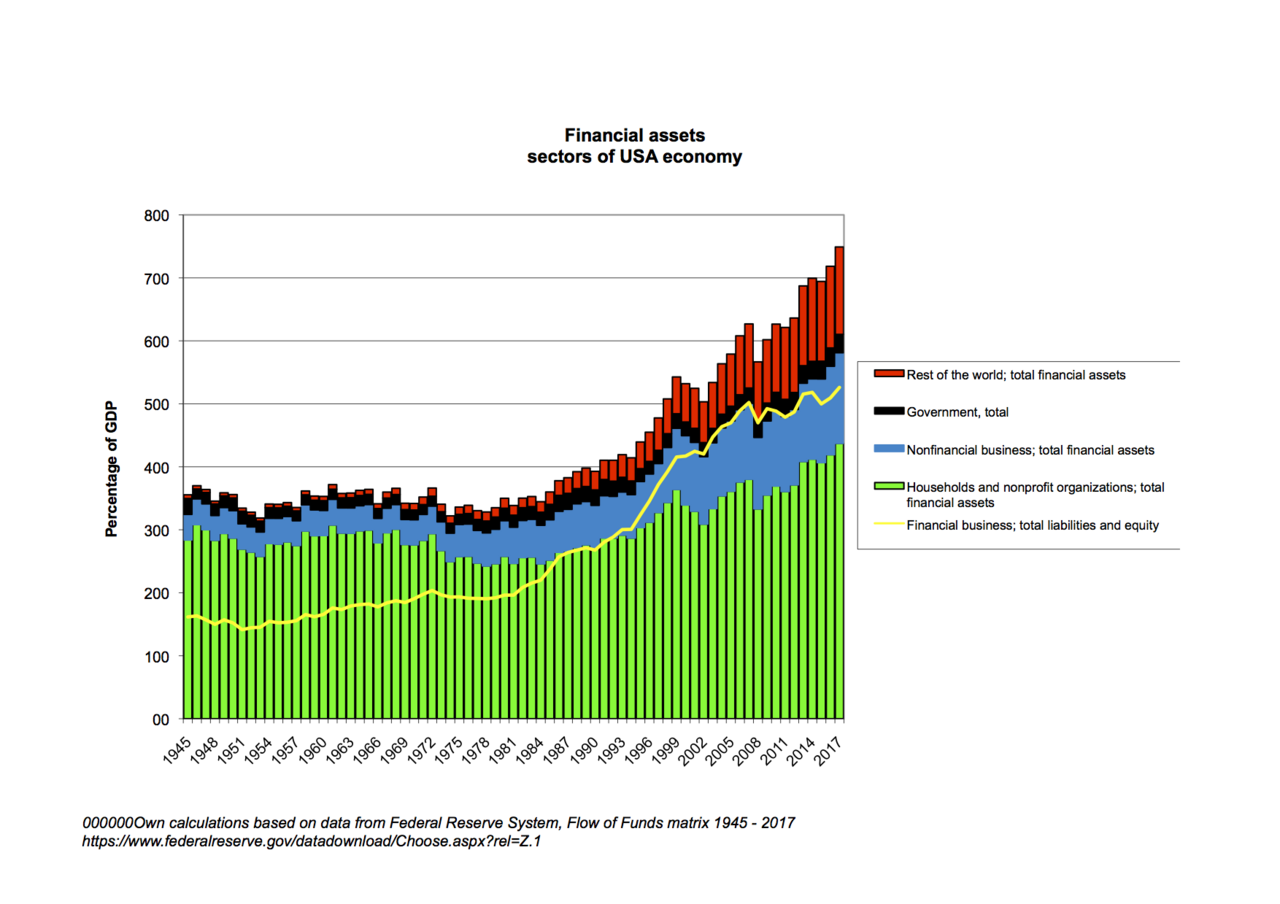

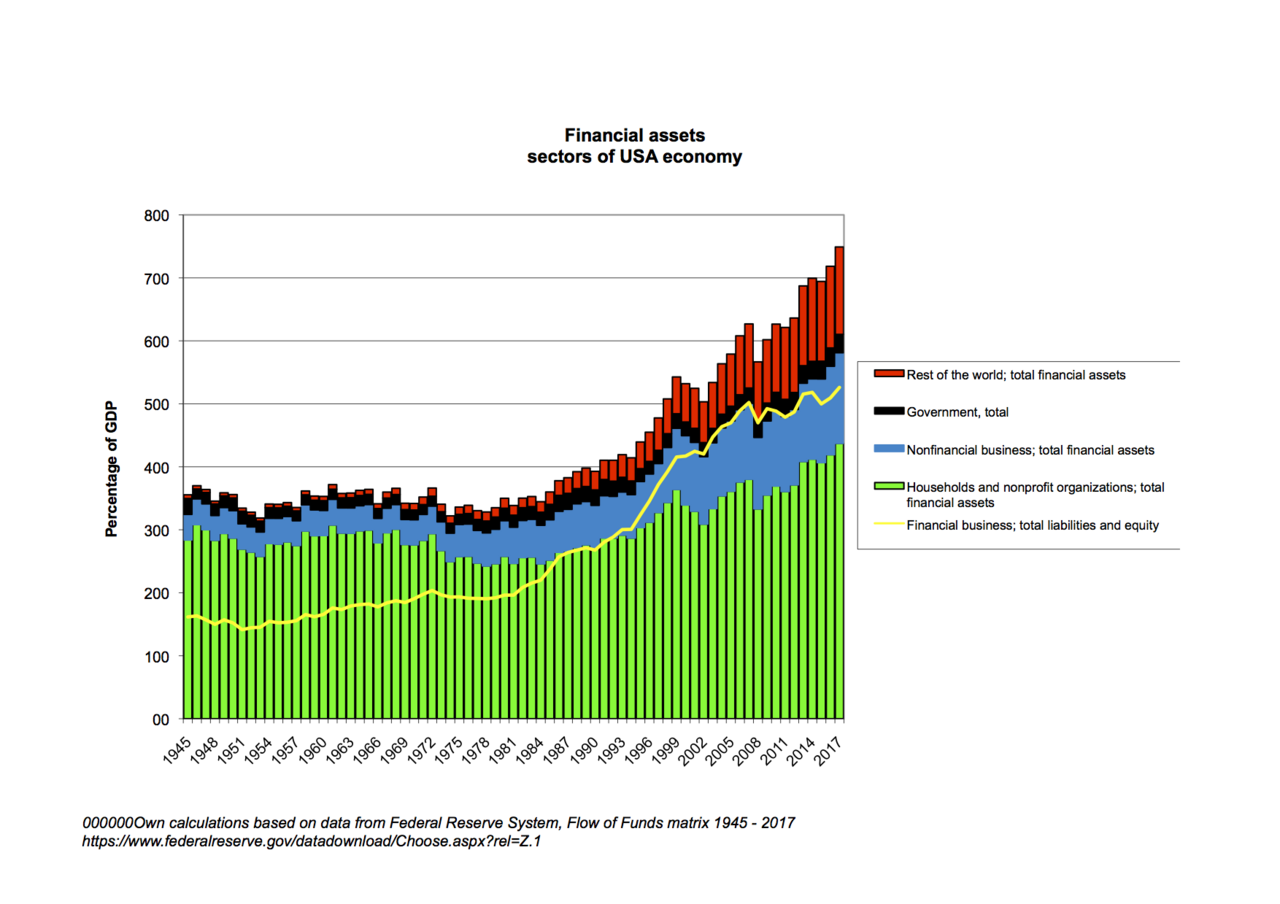

| Deregulation and accelerated growth In the 1970s, the financial sector comprised slightly more than 3% of total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the U.S. economy,[13] while total financial assets of all investment banks (that is, securities broker-dealers) made up less than 2% of U.S. GDP.[14] The period from the New Deal through the 1970s has been referred to as the era of "boring banking" because banks that took deposits and made loans to individuals were prohibited from engaging in investments involving creative financial engineering and investment banking.[15] U.S. federal deregulation in the 1980s of many types of banking practices paved the way for the rapid growth in the size, profitability, and political power of the financial sector. Such financial sector practices included creating private mortgage-backed securities,[16] and more speculative approaches to creating and trading derivatives based on new quantitative models of risk and value.[17] Wall Street ramped up pressure on the United States Congress for more deregulation, including for the repeal of Glass-Steagall, a New Deal law that, among other things, prohibits a bank that accepts deposits from functioning as an investment bank since the latter entails greater risks.[18] As a result of this rapid financialization, the financial sector scaled up vastly in the span of a few decades. In 1978, the financial sector comprised 3.5% of the American economy (that is, it made up 3.5% of U.S. GDP), but by 2007 it had reached 5.9%. Profits in the American financial sector in 2009 were six times higher on average than in 1980, compared with non-financial sector profits, which on average were just over twice what they were in 1980. Financial sector profits grew by 800%, adjusted for inflation, from 1980 to 2005. In comparison with the rest of the economy, U.S. nonfinancial sector profits grew by 250% during the same period. For context, financial sector profits from the 1930s until 1980 grew at the same rate as the rest of the American economy.[19]  Assets of sectors of the United States By way of illustration of the increased power of the financial sector over the economy, in 1978, commercial banks held $1.2 trillion (million million) in assets, which is equivalent to 53% of the GDP of the United States. By year's end 2007, commercial banks held $11.8 trillion in assets, which is equivalent to 84% of U.S. GDP. Investment banks (securities broker-dealers) held $33 billion (thousand million) in assets in 1978 (equivalent to 1.3% of U.S. GDP), but held $3.1 trillion in assets (equivalent to 22% U.S. GDP) in 2007. The securities that were so instrumental in triggering the 2008 financial crisis, asset-backed securities, including collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) were practically non-existent in 1978. By 2007, they comprised $4.5 trillion in assets, equivalent to 32% of the U.S. GDP.[20] |

規制緩和と成長加速 1970年代、金融セクターは米国経済の総国内総生産(GDP)の3%強を占めていた[13]。一方、全投資銀行(すなわち証券ブローカー・ディーラー) の金融資産総額は米国GDPの2%未満であった。[14] ニューディールから1970年代までの期間は「退屈な銀行業」の時代と呼ばれた。預金を受け入れ個人への融資を行う銀行は、創造的な金融工学や投資銀行業 務に関わる投資活動を行うことが禁止されていたからだ。[15] 1980年代の米国連邦政府による多様な銀行業務規制の緩和は、金融セクターの規模・収益性・政治的影響力の急拡大を可能にした。こうした金融セクターの 活動には、民間住宅ローン担保証券の創出[16]や、新たな定量的リスク・価値モデルに基づくデリバティブ商品の創出・取引といった投機的アプローチが含 まれた。[17] ウォール街は米国議会に対し、さらなる規制緩和を求める圧力を強めた。その中には、預金を受け入れる銀行が投資銀行業務を行うことを禁止するニューディー ル法であるグラス・スティーガル法の廃止も含まれていた。後者はより大きなリスクを伴うためである。[18] こうした急速な金融化の結果、金融セクターはわずか数十年で膨張した。1978年には金融セクターは米国経済の3.5%(つまり米国GDPの3.5%)を 占めていたが、2007年には5.9%に達した。2009年の米国金融セクターの利益は、1980年と比較して平均で6倍に増加した。一方、非金融セク ターの利益は平均で1980年の2倍強に留まった。金融セクターの利益は、1980年から2005年にかけて、インフレ調整後で800%増加した。これに 対し、米国非金融部門の利益は同期間に250%増加した。参考までに、1930年代から1980年までの金融部門の利益増加率は米国経済全体の伸び率と同 水準であった[19]。  米国各セクターの資産規模 金融セクターの経済に対する影響力増大を示す例として、1978年時点で商業銀行が保有する資産は1.2兆ドル(1000億ドル)であり、これは米国 GDPの53%に相当した。2007年末までに商業銀行の資産は11.8兆ドルに達し、米国GDPの84%に相当する規模となった。投資銀行(証券ブロー カー・ディーラー)の資産は1978年には330億ドル(10億ドル)で、米国GDPの1.3%に相当したが、2007年には3.1兆ドル(米国GDPの 22%)に達した。2008年の金融危機を引き起こす上で極めて重要な役割を果たした証券、すなわち資産担保証券(CDOを含む)は、1978年には事実 上存在しなかった。2007年までに、これらは4.5兆ドルの資産を占め、米国GDPの32%に相当した。[20] |

| The development of leverage and financial derivatives One of the most notable features of financialization has been the development of overleverage (more borrowed capital and less own capital) and, as a related tool, financial derivatives: financial instruments, the price or value of which is derived from the price or value of another, underlying financial instrument. Those instruments, whose initial purpose was hedging and risk management, have become widely traded financial assets in their own right. The most common types of derivatives are futures contracts, swaps, and options. In the early 1990s, a number of central banks around the world began to survey the amount of derivative market activity and report the results to the Bank for International Settlements.[21] The number and types of financial derivatives have grown enormously. In November 2007, commenting on the 2008 financial crisis and the subprime mortgage crisis, Doug Noland's Credit Bubble Bulletin, on Asia Times Online, noted, The scale of the Credit "insurance" problem is astounding. According to the Bank of International Settlements, the OTC market for Credit default swaps (CDS) jumped from $4.7 TN at the end of 2004 to $22.6 TN to end 2006. From the International Swaps and Derivatives Association we know that the total notional volume of credit derivatives jumped about 30% during the first half to $45.5 TN. And from the Comptroller of the Currency, total U.S. commercial bank Credit derivative positions ballooned from $492bn to begin 2003 to $11.8 TN as of this past June....[1] A major unknown regarding derivatives is the actual amount of cash behind a transaction. A derivatives contract with a notional value of millions of dollars may actually only cost a few thousand dollars. For example, an interest rate swap might be based on exchanging the interest payments on $100 million in US Treasury bonds at a fixed interest of 4.5%, for the floating interest rate of $100 million in credit card receivables. This contract would involve at least $4.5 million in interest payments, though the notional value may be reported as $100 million. However, the actual "cost" of the swap contract would be some small fraction of the minimal $4.5 million in interest payments. The difficulty of determining exactly how much this swap contract is worth, when accounted for on a financial institution's books, is typical of the worries of many experts and regulators over the explosive growth of these types of instruments.[citation needed] Contrary to common belief in the United States, the largest financial center for derivatives (and for foreign exchange) is London. According to MarketWatch on December 7, 2006,[dead link] The global foreign exchange market, easily the largest financial market, is dominated by London. More than half of the trades in the derivatives market are handled in London, which straddles the time zones between Asia and the U.S. And the trading rooms in the Square Mile, as the City of London financial district is known, are responsible for almost three-quarters of the trades in the secondary fixed-income markets.[This quote needs a citation] |

レバレッジと金融派生商品の発展 金融化の最も顕著な特徴の一つは、過剰なレバレッジ(自己資本の減少と借入資本の増加)の発展と、関連する手段としての金融派生商品の出現である。金融派 生商品とは、その価格や価値が別の基礎となる金融商品の価格や価値から派生する金融商品である。当初はヘッジやリスク管理を目的としていたこれらの商品 は、それ自体が広く取引される金融資産となった。最も一般的なデリバティブの種類は、先物契約、スワップ、オプションである。1990年代初頭、世界中の 中央銀行が相次いでデリバティブ市場の取引高を調査し、その結果を国際決済銀行に報告し始めた[21]。 金融派生商品の種類と数は膨大な規模に拡大した。2007年11月、アジア・タイムズ・オンラインのダグ・ノーランドによる「信用バブル速報」は、2008年の金融危機とサブプライム住宅ローン危機について次のように指摘している。 信用「保険」問題の規模は驚くべきものだ。国際決済銀行によれば、クレジット・デフォルト・スワップ(CDS)の店頭市場規模は2004年末の4.7兆ド ルから2006年末には22.6兆ドルに急増した。国際スワップ・デリバティブ協会によれば、クレジットデリバティブの想定元本総額が上半期に約30%増 加し45.5兆ドルに達した。通貨監督庁のデータでは、米商業銀行のクレジットデリバティブポジション総額が2003年初頭の4,920億ドルから、今年 6月時点で11.8兆ドルに膨れ上がった。[1] デリバティブ取引における大きな未知数は、実際の取引裏付けとなる現金額だ。名目価値が数百万ドルのデリバティブ契約でも、実際のコストは数千ドルに過ぎ ない場合がある。例えば金利スワップでは、固定金利4.5%の米国債1億ドル分の利払いを、変動金利のクレジットカード債権1億ドル分と交換する契約が結 ばれることがある。この契約では少なくとも450万ドルの利息支払いが発生するが、名目価値は1億ドルと報告される場合がある。しかし、スワップ契約の実 際の「コスト」は、最低限の450万ドルの利息支払いのごく一部に過ぎない。金融機関の帳簿上でこのスワップ契約の価値を正確に算定する難しさは、こうし た金融商品の爆発的成長に対する多くの専門家や規制当局の懸念を典型的に示している。[出典が必要] 米国で広く信じられている見解とは異なり、デリバティブ(および外国為替)の最大の金融センターはロンドンである。2006年12月7日付マーケットウォッチによれば、[リンク切れ] 世界最大の金融市場である外国為替市場は、ロンドンが支配している。デリバティブ市場の取引の半分以上は、アジアと米国の時差をまたぐロンドンで処理され る。そしてロンドン金融街「スクエア・マイル」の取引室は、二次固定利回り市場の取引のほぼ4分の3を担っている。[この引用には出典が必要] |

| Effects on the economy During the 2008 financial crisis, several economists and others began to argue that financial services had become too large a sector of the US economy, with no real benefit to society accruing from the activities of increased financialization.[22] In February 2009, white-collar criminologist and former senior financial regulator William K. Black listed the ways in which the financial sector harms the real economy. Black wrote, "The financial sector functions as the sharp canines that the predator state uses to rend the nation. In addition to siphoning off capital for its own benefit, the finance sector misallocates the remaining capital in ways that harm the real economy in order to reward already-rich financial elites harming the nation."[23] Emerging countries have also tried to develop their financial sector, as an engine of economic development. A typical aspect is the growth of microfinance or microcredit, as part of financial inclusion.[24] Bruce Bartlett summarized several studies in a 2013 article indicating that financialization has adversely affected economic growth and contributes to income inequality and wage stagnation for the middle class.[25] Cause of financial crises On 15 February 2010, Adair Turner, the head of Britain's Financial Services Authority, said financialization was correlated with the 2008 financial crisis. In a speech before the Reserve Bank of India, Turner said that the 1997 Asian financial crisis was similar to the 2008 financial crisis in that "both were rooted in, or at least followed after, sustained increases in the relative importance of financial activity relative to real non-financial economic activity, an increasing 'financialisation' of the economy."[26] |

経済への影響 2008年の金融危機の際、複数の経済学者らが、金融サービスが米国経済において過度に肥大化した分野となり、金融化の進展による活動から社会に実質的な利益がもたらされていないと主張し始めた[22]。 2009年2月、ホワイトカラー犯罪学者で元金融規制当局上級職員のウィリアム・K・ブラックは、金融セクターが実体経済に害を及ぼす方法を列挙した。ブ ラックはこう記した。「金融部門は、国民を食い荒らす捕食国家が用いる鋭い牙として機能する。自らの利益のために資本を吸い上げるだけでなく、金融部門は 残存資本を実体経済を損なう形で誤配分し、国民を害する富裕な金融エリート層に報いるのだ。」[23] 新興国も、経済発展の原動力として金融セクターの発展を試みてきた。その典型的な例が、金融包摂の一環としてのマイクロファイナンスやマイクロクレジットの成長である。[24] ブルース・バートレットは、2013年の記事で、金融化が経済成長に悪影響を及ぼし、中産階級の所得格差と賃金停滞の一因となっていることを示すいくつかの研究をまとめた。[25] 金融危機の原因 2010年2月15日、英国金融サービス機構のトップであるアデア・ターナーは、金融化が2008年の金融危機と相関関係にあると述べた。インド準備銀行 での講演で、ターナーは、1997年のアジア金融危機は、2008年の金融危機と「どちらも、実体経済における非金融活動に対する金融活動の相対的重要性 の持続的な高まり、つまり経済の「金融化」の進展に根ざしていた、あるいは少なくともそれに続いて発生した」という点で類似していると述べた。[26] |

| Effects on political system Some, such as former International Monetary Fund chief economist Simon Johnson, have argued that the increased power and influence of the financial services sector had fundamentally transformed American politics, endangering representative democracy itself through undue influence on the political system and regulatory capture by the financial oligarchy.[27] In the 1990s vast monetary resources flowing to a few "megabanks," enabled the financial oligarchy to achieve greater political power in the United States. Wall Street firms largely succeeded in getting the American political system and regulators to accept the ideology of financial deregulation and the legalization of more novel financial instruments.[28] Political power was achieved through contributions to political campaigns, financial industry lobbying, and a revolving door that positioned financial industry leaders in key politically appointed policy making and regulatory roles and that rewarded sympathetic senior government officials with high-paying Wall Street jobs after their government service.[29] The financial sector was the leading contributor to political campaigns since at least the 1990s, contributing more than $150 million in 2006. (This far exceeded the second largest political contributing industry, the healthcare industry, which contributed $100 million in 2006.) From 1990 to 2006, the securities and investment industry increased its political contributions six-fold, from an annual $12 to $72 million. The financial sector contributed $1.7 billion to political campaigns from 1998 to 2006, and spent an additional $3.4 billion on political lobbying, according to one estimate.[30][vague] Policy makers such as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan called for self-regulation.[citation needed] |

政治システムへの影響 国際通貨基金(IMF)の元チーフエコノミスト、サイモン・ジョンソンらの一部は、金融サービス部門の権力と影響力の増大がアメリカ政治を根本的に変容さ せ、政治システムへの不当な影響力と金融寡頭による規制の乗っ取りを通じて、代表民主制そのものを危険に晒していると主張している。[27] 1990年代、少数の「メガバンク」に流れ込んだ膨大な資金により、金融寡頭勢力は米国でより大きな政治力を獲得した。ウォール街の企業は、米国の政治シ ステムと規制当局に金融規制緩和のイデオロギーと、より斬新な金融商品の合法化を受け入れさせることにほぼ成功した。[28] 政治的権力は、選挙運動への献金、金融業界のロビー活動、そして金融業界のリーダーを政治任命の政策決定・規制の要職に配置する「回転ドア」制度、さらに 政府勤務後に同調的な政府高官をウォール街の高給職で報いる仕組みを通じて獲得された。[29] 金融セクターは少なくとも1990年代以降、選挙運動への最大の献金源であり、2006年には1億5000万ドル以上を拠出した。(これは2006年に1 億ドルを寄付した第2位の医療業界を大きく上回る額である。)1990年から2006年にかけて、証券・投資業界の政治献金は年間1200万ドルから 7200万ドルへと6倍に増加した。ある推計によれば、金融セクターは1998年から2006年にかけて政治運動に17億ドルを寄付し、さらに34億ドル を政治ロビー活動に費やした。[30][不明確] 連邦準備制度理事会(FRB)議長アラン・グリーンスパンら政策立案者は自主規制を求めた。[出典必要] |

| 2008 financial crisis Capital control Derivative (finance) Economic rent Economic sociology Enshittification Financial capital Financial economics FIRE economy Foreign exchange trading Late capitalism Neoliberalism Shadow banking system Tech bubble |

2008年の金融危機 資本規制 デリバティブ(金融) 経済的余剰 経済社会学 エンシッティフィケーション 金融資本 金融経済学 FIRE経済 外国為替取引 後期資本主義 新自由主義 シャドーバンキングシステム テックバブル |

| 1. Thomas Philippon (Finance

Department of the New York University Stern of Business at New York

University). The future of the financial industry.[dead link] Stern on

Finance, November 6, 2008.[self-published source?] 2. Krippner, G. R. (May 2005). "The financialization of the American economy". Socio-Economic Review. 3 (2): 173–208. doi:10.1093/SER/mwi008. 3. Marois, Thomas (2012). States, Banks and Crisis: Emerging Finance Capitalism in Mexico and Turkey. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85793-858-9.[page needed] 4. Epstein, Gerald (2019). "Financialization, rentier interests and central bank policy". The Political Economy of Central Banking. doi:10.4337/9781788978415.00024. ISBN 978-1-78897-841-5. 5. Goodell Ugalde, Elliot. “In Defence Of Marx’s Labour Theory Of Value: Vancouver’s Housing ‘Crisis.” Cultural Logic: A Journal of Marxist Theory and Practice, 26 (2024): 69-101. University of British Columbia Press. 6. Cushen, Jean (May 2013). "Financialization in the workplace: Hegemonic narratives, performative interventions and the angry knowledge worker" (PDF). Accounting, Organizations and Society. 38 (4): 314–331. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2013.06.001. 7. Hudson, Michael (September 1998). "Financial Capitalism v. Industrial Capitalism (Contribution to The Other Canon Conference on Production Capitalism vs. Financial Capitalism Oslo, September 3-4, 1998 )". Retrieved March 12, 2009.[self-published source?] 8. Reinert, Erik S.; Daastøl, Arno Mong (2011). Production Capitalism vs. Financial Capitalism – Symbiosis and Parasitism. An Evolutionary Perspective and Bibliography (PDF) (Report). Working Papers in Technology Governance and Economic Dynamics no. 36. The Other Canon Foundation, Norway. Tallinn University of Technology, Tallinn. 9. Johnson & Kwak 2010, pp. 28–29. 10. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 28. 11. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 26. 12. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 27. 13. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 61. 14. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 63. 15. Johnson & Kwak 2010, pp. 60–63. 16. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 76. 17. Johnson & Kwak 2010, pp. 78–81. 18. Johnson & Kwak 2010, pp. 82–83, 95. 19. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 60. 20. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 59. 21. "OTC derivatives statistics - data | BIS Data Portal". data.bis.org. Retrieved February 15, 2025. 22. Megan McCardle. The Quiet Coup. The Atlantic Monthly, May 2009 23. Black, William K. (March 18, 2010). "How the Servant Became a Predator: Finance's Five Fatal Flaws". HuffPost. 24. Mader, Philip (2017). "Microfinance and Financial Inclusion". The Oxford Handbook of the Social Science of Poverty. pp. 843–865. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199914050.013.38. ISBN 978-0-19-991405-0. 25. Bartlett, Bruce (June 11, 2013). "'Financialization' as a Cause of Economic Malaise". Economix Blog. 26. Reserve Bank of India. "After the Crises: Assessing the Costs and Benefits of Financial Liberalisation". Speech delivered by Lord Adair Turner, Chairman, Financial Services Authority, United Kingdom, at the Fourteenth C. D. Deshmukh Memorial Lecture on February 15, 2010 at Mumbai. 27. Megan McCardle. The Quiet Coup. The Atlantic Monthly, May 2009 28. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 89. 29. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 90. 30. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 91. |

1. トーマス・フィリポン(ニューヨーク大学スターン経営大学院金融学科)。金融業界の未来。[リンク切れ] Stern on Finance, 2008年11月6日。[自己出版資料?] 2. クリップナー, G. R. (2005年5月). 「アメリカ経済の金融化」. 社会経済レビュー。3(2): 173–208。doi:10.1093/SER/mwi008。 3. マロワ、トーマス(2012)。国家、銀行、危機:メキシコとトルコにおける新興金融資本主義。エドワード・エルガー出版。ISBN 978-0-85793-858-9。[ページ番号が必要] 4. エプスタイン、ジェラルド(2019)。「金融化、レントシーカーの利益と中央銀行政策」。『中央銀行の政治経済学』。doi:10.4337/9781788978415.00024。ISBN 978-1-78897-841-5。 5. グッデル・ウガルデ、エリオット。「マルクスの労働価値説を擁護して:バンクーバーの住宅『危機』」『文化論理:マルクス主義理論と実践のジャーナル』26号(2024年):69-101頁。ブリティッシュコロンビア大学出版局。 6. ジャン・クーシェン(2013年5月)。「職場における金融化:ヘゲモニックな物語、パフォーマティビティな介入、そして怒れる知識労働者」 (PDF)。『会計・組織・社会』38巻4号:314–331頁。doi:10.1016/j.aos.2013.06.001。 7. ハドソン、マイケル(1998年9月)。「金融資本主義対産業資本主義(生産資本主義対金融資本主義に関する『もうひとつの規範』会議への寄稿、オスロ、1998年9月3-4日)」[自己出版資料?]。2009年3月12日取得。 8. ライナート、エリック・S.; ダーステル、アルノ・モン(2011年)。『生産資本主義対金融資本主義-共生と寄生。進化的視点と文献目録』(PDF)(報告書)。技術ガバナンスと経 済ダイナミクスに関するワーキングペーパー第36号。ノルウェー、ザ・アザー・キャノン財団。タリン工科大学、タリン。 9. Johnson & Kwak 2010, pp. 28–29. 10. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 28. 11. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 26. 12. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 27. 13. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 61. 14. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 63. 15. Johnson & Kwak 2010, pp. 60–63. 16. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 76. 17. Johnson & Kwak 2010, pp. 78–81. 18. Johnson & Kwak 2010, pp. 82–83, 95. 19. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 60. 20. Johnson & Kwak 2010, p. 59. 21. 「OTCデリバティブ統計 - データ | BISデータポータル」. data.bis.org. 2025年2月15日取得. 22. Megan McCardle. 『静かなるクーデター』. The Atlantic Monthly, 2009年5月号 23. ブラック、ウィリアム・K. (2010年3月18日). 「従者が捕食者となった経緯:金融の五つの致命的な欠陥」. ハフポスト. 24. メイダー、フィリップ (2017). 「マイクロファイナンスと金融包摂」. 『貧困の社会科学オックスフォード・ハンドブック』. pp. 843–865. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199914050.013.38. ISBN 978-0-19-991405-0. 25. バートレット、ブルース(2013年6月11日)。「経済不振の原因としての『金融化』」。エコノミックス・ブログ。 26. インド準備銀行。「危機の後:金融自由化のコストと便益の評価」。2010年2月15日にムンバイで開催された第14回C. D. デシュムク記念講演会における、英国金融サービス機構(FSA)会長、アデア・ターナー卿によるスピーチ。 27. メーガン・マッカードル。『静かなクーデター』。アトランティック・マンスリー、2009年5月 28. ジョンソン&クワク 2010、89 ページ。 29. ジョンソン&クワク 2010、90 ページ。 30. ジョンソン&クワク 2010、91 ページ。 |

| Sources Johnson, Simon; Kwak, James (2010). 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-37922-1. Further reading Baker, A (2005). IPE, Corporate Governance and the New Politics of Financialisation: Issues Raised by Sarbanes-Oxley. British International Studies Association Annual Conference. Hein, Eckhard; Dodig, Nina; Budyldina, Natalia (2014). Financial, economic and social systems: French Regulation School, Social Structures of Accumulation and Post-Keynesian approaches compared (Report). hdl:10419/92910. Lavoie, Marc (2012). "Financialization, neo-liberalism, and securitization". Journal of Post Keynesian Economics. 35 (2): 215–233. doi:10.2753/pke0160-3477350203. JSTOR 23469991. S2CID 153927517. Martin, Randy (2002). Financialization Of Daily Life. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-4399-0597-5. Orhangazi, È (2008). Financialization and the US Economy. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84844-016-6. Orhangazi, O. (April 9, 2008). "Financialisation and capital accumulation in the non-financial corporate sector:: A theoretical and empirical investigation on the US economy: 1973-2003". Cambridge Journal of Economics. 32 (6): 863–886. doi:10.1093/cje/ben009. Gomez, Pierre-Yves; Korine, Harry (2008). Entrepreneurs and Democracy: A Political Theory of Corporate Governance. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85638-6. Marois, Thomas (2012). "Finance, finance capital and financialization". The Elgar Companion to Marxist Economics. doi:10.4337/9781781001226.00028. ISBN 978-1-78100-122-6. |

出典 ジョンソン、サイモン;クァク、ジェームズ(2010)。『13人の銀行家:ウォール街の乗っ取りと次の金融危機』。クノップ・ダブルデイ出版グループ。ISBN 978-0-307-37922-1。 関連文献 ベイカー、A(2005)。IPE、コーポレート・ガバナンスと金融化の新たな政治学:サーベンス・オクスリー法が提起する課題。英国国際研究協会年次大会。 ハイン、エックハルト;ドディグ、ニーナ;ブディリナ、ナタリア(2014)。金融・経済・社会システム:フランス規制学派、蓄積の社会構造、ポスト・ケインズ主義的アプローチの比較(報告書)。hdl:10419/92910. Lavoie, Marc (2012). 「金融化、新自由主義、証券化」. ポスト・ケインズ経済学ジャーナル. 35 (2): 215–233. doi:10.2753/pke0160-3477350203. JSTOR 23469991。S2CID 153927517。 マーティン、ランディ(2002)。『日常生活の金融化』。テンプル大学出版。ISBN 978-1-4399-0597-5。 オルハンガジ、E(2008)。『金融化と米国経済』。エドワード・エルガー出版。ISBN 978-1-84844-016-6。 Orhangazi, O. (2008年4月9日). 「非金融企業セクターにおける金融化と資本蓄積:米国経済に関する理論的・実証的研究:1973-2003」. ケンブリッジ経済学ジャーナル。32 (6): 863–886. doi:10.1093/cje/ben009. ゴメス、ピエール=イヴ; コリン、ハリー (2008). 『起業家と民主主義:コーポレート・ガバナンスの政治理論』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-521-85638-6. マロワ、トマ(2012)。「金融、金融資本、そして金融化」。『マルクス主義経済学のエルガー・コンパニオン』。doi:10.4337/9781781001226.00028。ISBN 978-1-78100-122-6。 |

| External links Blackburn, Robin (March–April 2008). "Subprime crisis". New Left Review. 50. New Left Review. Bresser-Pereira, Luiz Carlos (May 2010). The global financial crisis and a new capitalism? (paper 592) (PDF). Levy Economics Institute. Cushen, Jean (May 2013). "Financialization in the workplace: Hegemonic narratives, performative interventions and the angry knowledge worker" (PDF). Accounting, Organizations and Society. 38 (4): 314–331. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2013.06.001. Epstein, Gerald A. (2005). "Introduction: Financialization and the World Economy" (PDF). In Epstein, Gerald A. (ed.). Financialization and the world economy. Cheltenham, U.K. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Pub. pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-1-84542-965-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017. Foster, John Bellamy (December 2006). "Monopoly-Finance Capital". Monthly Review. 58 (7): 1. doi:10.14452/MR-058-07-2006-11_1. Foster, John Bellamy (April 2007). "The Financialization of Capitalism". Monthly Review. 58 (11): 1. doi:10.14452/MR-058-11-2007-04_1. Foster, John Bellamy (April 2008). "The Financialization of Capital and the Crisis". Monthly Review. 59 (11): 1. doi:10.14452/MR-059-11-2008-04_1. Krippner, Greta R. (May 2005). "The financialization of the American economy". Socio-Economic Review. 3 (2). Oxford Journals: 173–208. doi:10.1093/SER/mwi008. S2CID 53957580. Moyers, Bill (host); Bogle, John (guest) (September 28, 2007). "Bill Moyers talks with John Bogle". Bill Moyers Journal. PBS. John Bogle, founder and retired CEO of The Vanguard Group of mutual funds, discusses how the financial system has overwhelmed the productive system, on Bill Moyers Journal Orhangazi, Özgür (October 2007). Financialization and capital accumulation in the non-financial corporate sector: a theoretical and empirical investigation of the U.S. economy: 1973-2003 (PDF). Political Economy Research Institute (PERI). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017. Working paper no. 149. Orhangazi, Özgür (2008). Financialization and the US economy. Cheltenham, UK Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar. ISBN 9781848440166. Preview. Palley, Thomas I. (November 2007). Financialization: what it is and why it matters (paper 525) (PDF). Levy Economics Institute. Scholte, Jan Aart (June 5, 2013). "World Financial Crisis and Civil Society: Implications for Global Democracy (lecture)". DRadio Wissen Hörsaal (introduction in German, lecture in English) Thomson, Frances; Dutta, Sahil (January 2016). Financialisation: A Primer. Transnational Institute. Tori, Daniele; Onaran, Özlem (August 18, 2018). "The effects of financialization on investment: evidence from firm-level data for the UK". Cambridge Journal of Economics. 42 (5): 1393–1416. doi:10.1093/cje/bex085. Tori, Daniele; Onaran, Özlem (December 2020). "Financialization, financial development and investment. Evidence from European non-financial corporations" (PDF). Socio-Economic Review. 18 (3): 681–718. doi:10.1093/ser/mwy044. Vasudevan, Ramaa (November–December 2008). "Financialization: A Primer". Dollars & Sense magazine. |

外部リンク ブラックバーン、ロビン(2008年3月–4月)。「サブプライム危機」。『ニュー・レフト・レビュー』。50号。ニュー・レフト・レビュー。 ブレッサー=ペレイラ、ルイス・カルロス(2010年5月)。『世界金融危機と新たな資本主義か?』(ペーパー592)(PDF)。レヴィ経済研究所。 クシェン、ジーン(2013年5月) . 「職場における金融化:ヘゲモニックな物語、パフォーマティビティな介入、そして怒れる知識労働者」 (PDF). 『会計、組織、社会』. 38 (4): 314–331. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2013.06.001. エプスタイン、ジェラルド・A. (2005). 「序論:金融化と世界経済」 (PDF). エプスタイン, ジェラルド・A. (編). 『金融化と世界経済』. チェルトナム, イギリス・ノーサンプトン, マサチューセッツ州: エドワード・エルガー出版. pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-1-84542-965-2. 2017年2月24日時点のオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ. 2017年2月24日に閲覧。 フォスター、ジョン・ベラミー(2006年12月)。「独占金融資本」。『月刊レビュー』58巻7号:1頁。doi:10.14452/MR-058-07-2006-11_1。 フォスター、ジョン・ベラミー(2007年4月)。「資本主義の金融化」。『月刊レビュー』58巻11号:1頁。doi:10.14452/MR-058-11-2007-04_1。 フォスター、ジョン・ベラミー(2008年4月)。「資本の金融化と危機」 。月刊レビュー。59 (11): 1. doi:10.14452/MR-059-11-2008-04_1. クリップナー、グレタ・R.(2005年5月)。「アメリカ経済の金融化」。社会経済レビュー。3 (2)。オックスフォードジャーナルズ: 173–208. doi:10.1093/SER/mwi008. S2CID 53957580. モイヤーズ、ビル(司会者);ボグル、ジョン(ゲスト)(2007年9月28日)。「ビル・モイヤーズがジョン・ボグルと語る」。ビル・モイヤーズ・ジャーナル。PBS。 投資信託会社バンガード・グループの創業者で元CEOであるジョン・ボーグルが、金融システムが生産システムを圧倒した経緯についてビル・モイヤーズ・ジャーナルで語る オルハンガジ、オズギュル(2007年10月)。非金融企業セクターにおける金融化と資本蓄積:米国経済に関する理論的・実証的調査:1973-2003 年(PDF)。政治経済研究所(PERI)。2017年2月24日時点のオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブ。2017年2月24日閲覧。ワーキングペー パー第149号。 オルハンガジ、オズギュル(2008年)。『金融化と米国経済』。英国チェルトナム/米国マサチューセッツ州ノーサンプトン:エドワード・エルガー。ISBN 9781848440166。プレビュー。 パリー、トーマス・I.(2007年11月)。金融化:その実態と重要性(ペーパー525)(PDF)。レヴィ経済研究所。 ショルテ、ヤン・アールト(2013年6月5日)。「世界金融危機と市民社会:グローバル民主主義への示唆(講演)」 DRadio Wissen Hörsaal(ドイツ語による紹介、英語による講演) トムソン、フランセス;ドゥッタ、サヒル(2016年1月)。『金融化:入門書』。トランスナショナル研究所。 トーリ、ダニエレ;オナラン、オズレム(2018年8月18日)。「金融化が投資に与える影響:英国企業レベルのデータによる実証」『ケンブリッジ経済学ジャーナル』42巻5号、1393–1416頁。doi:10.1093/cje/bex085。 トーリ、ダニエレ;オナラン、オズレム(2020年12月)。「金融化、金融発展、投資:欧州非金融企業からの実証」『社会経済レビュー』18巻3号、 681–718頁。doi:10.1093/ser/mwy044。欧州の非金融企業からの証拠」 (PDF). 社会経済レビュー. 18 (3): 681–718. doi:10.1093/ser/mwy044. ヴァスデヴァン、ラーマ (2008年11月–12月). 「金融化:入門」. ドルズ&センス誌. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Financialization |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099