エルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズ

Elsie Clews Parsons(November 27, 1875 –

December 19, 1941)

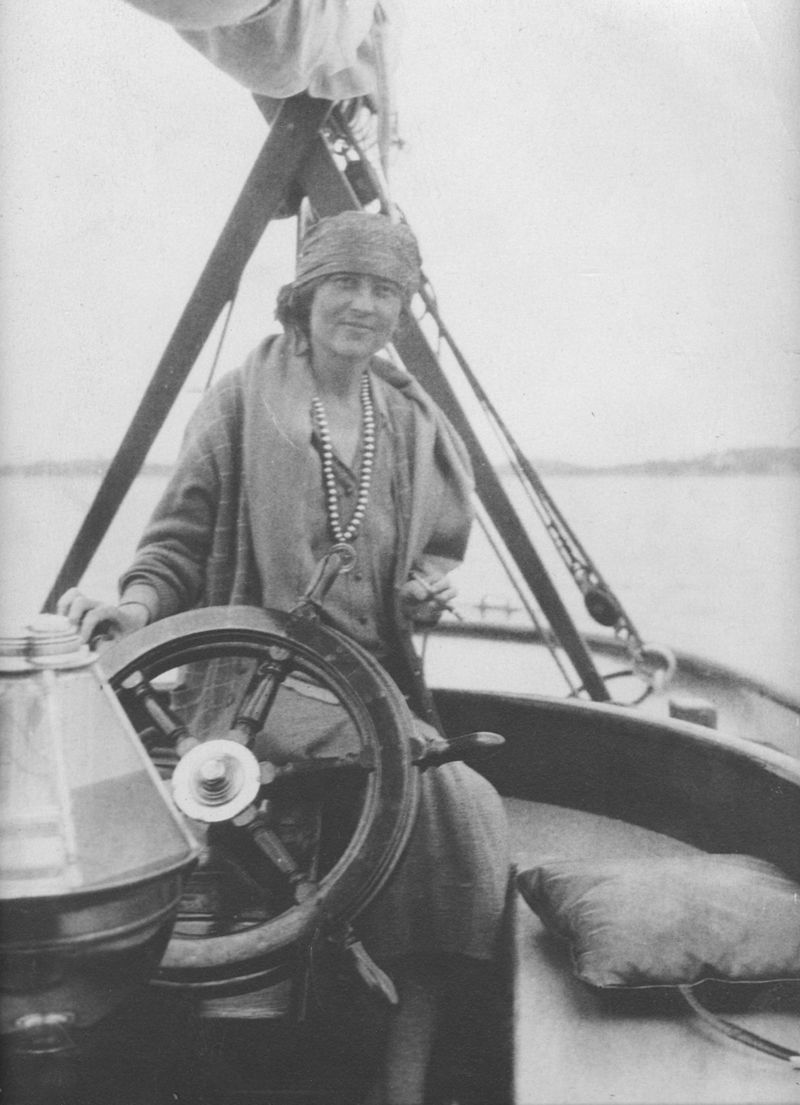

☆ エルシー・ワーシントン・クリューズ・パーソンズ(Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons、1875年11月27日~1941年12月19日)はアメリカの人類学者、社会学者、民俗学者、フェミニストであり、アリゾナ、ニューメ キシコ、メキシコのテワ族やホピ族などのアメリカ先住民族を研究した。彼女はニュースクールの設立に貢献し、『アメリカ民俗学雑誌』(The Journal of American Folklore)の副編集長(1918年~1941年)、アメリカ民俗学会会長(1919年~1920年)、アメリカ民族学会会長(1923年 ~1925年)を務め、死の直前にはアメリカ人類学会初の女性会長(1941年)に選出された。

| Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons

(November 27, 1875 – December 19, 1941) was an American anthropologist,

sociologist, folklorist, and feminist who studied Native American

tribes—such as the Tewa and Hopi—in Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico.

She helped found The New School.[2] She was associate editor for The

Journal of American Folklore (1918–1941), president of the American

Folklore Society (1919–1920), president of the American Ethnological

Society (1923–1925), and was elected the first female president of the

American Anthropological Association (1941) right before her

death.[3][4][5] She earned her bachelor's degree from Barnard College in 1896.[6] She received her master’s degree (1897) and Ph.D. (1899) from Columbia University.[3] Every other year, the American Ethnological Society awards the Elsie Clews Parsons Prize for the best graduate student essay, in her honor.[7][8] |

エル

シー・ワーシントン・クリューズ・パーソンズ(Elsie Worthington Clews

Parsons、1875年11月27日~1941年12月19日)はアメリカの人類学者、社会学者、民俗学者、フェミニストであり、アリゾナ、ニューメ

キシコ、メキシコのテワ族やホピ族などのアメリカ先住民族を研究した。彼女はニュースクールの設立に貢献し、『アメリカ民俗学雑誌』(The

Journal of American

Folklore)の副編集長(1918年~1941年)、アメリカ民俗学会会長(1919年~1920年)、アメリカ民族学会会長(1923年

~1925年)を務め、死の直前にはアメリカ人類学会初の女性会長(1941年)に選出された[3][4][5]。 1896年にバーナード大学で学士号を取得し[6]、コロンビア大学で修士号(1897年)と博士号(1899年)を取得した[3]。 アメリカ民族学会は隔年で、彼女の功績を称え、大学院生の最優秀論文にエルシー・クリューズ・パーソンズ賞を授与している[7][8]。 |

| Biography Parsons was the daughter of Henry Clews, a wealthy New York banker, and Lucy Madison Worthington. Her brother, Henry Clews Jr., was an artist. On September 1, 1900, in Newport, Rhode Island,[9] she married future three-term progressive Republican congressman Herbert Parsons, an associate and political ally of President Teddy Roosevelt.[10] When her husband was a member of Congress, she published two then-controversial books under the pseudonym John Main.[11] Parsons became interested in anthropology in 1910.[4] She believed that folklore was a key to understanding a culture and that anthropology could be a vehicle for social change.[12] Her work Pueblo Indian Religion is considered a classic; here she gathered all her previous extensive work and that of other authors.[13] It is, however, marred by intrusive and deceptive research techniques[which?].[14] She is, however, pointed to by current critical scholars[who?] as an archetypical example of an "Antimodern Feminist" thinker, known for their infatuation with Native American Indians that often manifested as a desire to preserve a "traditional" and "pure" Indian identity, irrespective of how Native Peoples themselves approached issues of modernization or cultural change[citation needed]. Scholars Sandy Grande and Margaret D. Jacobs argue that her racist and objectivizing tendencies towards indigenous peoples of the Americas are evidenced, for example, by her willingness to change her name[clarification needed] and appropriate a Hopi identity[dubious – discuss] primarily to increase her access to research sites and participants.[15][16] |

略歴 パーソンズはニューヨークの裕福な銀行家ヘンリー・クリューズとルーシー・マディソン・ワーシントンの娘。兄のヘンリー・クリューズ・ジュニアは芸術家 だった。1900年9月1日、ロードアイランド州ニューポートで、テディ・ルーズベルト大統領の同僚であり政治的盟友であった、後に共和党の進歩派下院議 員として3期務めたハーバート・パーソンズと結婚[10]。 パーソンズは1910年に人類学に興味を持つようになり[4]、民間伝承が文化を理解する鍵であり、人類学が社会変革の手段になりうると信じていた[12]。 彼女の著作である『プエブロ・インディアンの宗教』は古典とみなされており、ここには彼女のこれまでの広範な研究や他の著者の研究がすべて集められている[13]。 しかし、彼女は現在の批評的な学者たち[誰?]から「反近代フェミニスト」思想家の典型的な例として指摘されており、ネイティブ・アメリカン・インディア ンへの熱中によって知られ、それはネイティブ・インディアン自身が近代化や文化的変化の問題にどのように取り組んでいるかにかかわらず、しばしば「伝統 的」で「純粋」なインディアンのアイデンティティを維持したいという願望として現れている[要出典]。学者であるサンディ・グランデとマーガレット・D・ ジェイコブスは、アメリカ大陸の先住民に対する彼女の人種差別的で客観化する傾向は、例えば、彼女が主に研究場所や参加者へのアクセスを増やすために、自 分の名前を変え[要出典]、ホピ族のアイデンティティ[要出典]を採用しようとしたこと[要出典]によって証明されていると論じている[15][16]。(→宇野 2009) |

| Feminist ideas Parsons feminist beliefs were viewed as extremely radical for her time. She was a proponent of trial marriages, divorce by mutual consent and access to reliable contraception, which she wrote about in her book The Family (1906).[17] She also wrote about the effects society had on the growth of individuals, and more precisely the effect of gender role expectations and how they stifle individual growth for both women and men. The Family (1906) was met with such back-lash she published her second book Religious Chastity (1913) under the pseudonym "John Main" as to not affect her husband, Herbert Parsons political career. Her ideas were so far ahead that only after her death did they begin to be discussed. This has led to her becoming recognized[by whom?] as one of the early pioneers of the feminist movement. Her writings and her lifestyle challenged conventional gender roles at the time and helped spark the conversation for gender equality. |

フェミニスト思想 パーソンズのフェミニストとしての信念は、当時としては極めて急進的なものであった。彼女はまた、社会が個人の成長に与える影響について、より正確には、 性別による役割分担の期待や、それが女性にとっても男性にとっても個人の成長をいかに阻害するかについて書いた。家族』(1906年)は反感を買い、彼女 は夫であるハーバート・パーソンズの政治的キャリアに影響を与えないよう、2冊目の『宗教的貞操』(1913年)を「ジョン・メイン」というペンネームで 出版した。彼女の考えはあまりに先を行っていたため、彼女の死後になって初めて議論され始めた。そのため、彼女はフェミニズム運動の初期の先駆者のひとり として認識されるようになった。彼女の著作とそのライフスタイルは、当時の従来の性別役割分担に異議を唱え、男女平等の話題の火付け役となった。 |

| Works Early works of sociology The Family (1906) Religious Chastity (1913) The Old-Fashioned Woman (1913) Fear and Conventionality (1914) Parsons, Elsie Clews (1997). Fear and Conventionality. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-64746-3. Social Freedom (1915) Social Rule (1916) Anthropology The Social Organization of the Tewa of New Mexico (1929) Hopi and Zuni Ceremonialism (1933) Pueblo Indian Religion (1939) Ethnographies Mitla: Town of the Souls (1936) Peguche (1945)[pdf] Research in folklore Folk-Lore from the Cape Verde Islands (1923) Folk-Lore of the Sea Islands, S.C. (1924) Micmac Folklore (1925) Folk-Lore of the Antilles, French and English (3v., 1933–1943) Reprints Parsons, Elsie Clews (1992). North American Indian Life: Customs and Traditions of 23 Tribes. Dover Publications (First edition, 1922). ISBN 978-0-486-27377-8. Parsons, Elsie Clews (1996). Taos Tales. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-28974-8. Parsons, Elsie Clews (1994). Tewa Tales. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1452-6. Parsons, Elsie Clews (1996). Pueblo Indian Religion. 2 vols. Introductions by Ramon Gutierrez and Pauline Turner Strong. Bison Books reprint. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. |

著作 社会学の初期著作 家族論(1906年) 宗教的貞操(1913年) 古風な女性(1913年) 恐怖と慣習性(1914年) パーソンズ、エルシー・クルース(1997年)。『恐怖と慣習性』。シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-226-64746-3。 『社会的自由』(1915年) 『社会的規範』(1916年) 人類学 『ニューメキシコ州テワ族の社会組織』(1929年) 『ホピ族とズニ族の儀式』(1933年) 『プエブロ・インディアンの宗教』(1939年) 民族誌 ミトラ:魂の町(1936年) ペグチェ(1945年)[pdf] 民俗学研究 カーボベルデ諸島の民俗(1923年) サウスカロライナ州海島地域の民俗(1924年) ミクマク族の民俗(1925年) アンティル諸島の民俗学、フランス語と英語(全3巻、1933–1943) 復刻版 パーソンズ、エルシー・クルース(1992)。『北米インディアンの生活:23部族の習俗と伝統』。ドーバー出版(初版1922年)。ISBN 978-0-486-27377-8。 パーソンズ、エルシー・クルース(1996)。『タオスの物語』。ドーバー出版。ISBN 978-0-486-28974-8。 パーソンズ、エルシー・クルーズ (1994)。『テワ族の物語』。アリゾナ大学出版。ISBN 978-0-8165-1452-6。 パーソンズ、エルシー・クルーズ (1996)。『プエブロ・インディアン宗教』。全 2 巻。ラモン・グティエレスとポーリーン・ターナー・ストロングによる序文。バイソン・ブックス再版。リンカーンおよびロンドン:ネブラスカ大学出版。 |

| Ruth Benedict Franz Boas Cape Verdean Creole Château de la Napoule History of feminism List of Barnard College people Zora Neale Hurston Mabel Dodge Luhan Margaret Mead Pueblo clown Taos Pueblo |

ルース・ベネディクト フランツ・ボアズ カーボベルデ・クレオール語 シャトー・ド・ラ・ナプール フェミニズムの歴史 バーナード・カレッジの人物一覧 ゾラ・ニール・ハーストン メイベル・ドッジ・ルーハン マーガレット・ミード プエブロの道化師 タオス・プエブロ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elsie_Clews_Parsons |

|

| References 1. "Behavioral Psychologist Henry McIlvaine Parsons, 92, Dies". The Washington Post. 2004-08-01. 2. Spier, Leslie, and A. L. Kroeber. "Elsie Clews Parsons"], American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 45, No. 2, Centenary of the American Ethnological Society (April–June 1943), pp. 244–255. JSTOR 663274. 3. Del Monte, Kathleen; Karen Bachman; Catherine Klein; Bridget McCourt (1999-03-19). "Elsie Clews Parsons". Celebration of Women Anthropologists. University of South Florida. Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2007-05-16. 4. "Elsie Clews Parsons Papers". American Philosophical Society. Archived from the original on 2007-03-10. Retrieved 2007-05-16. 5. Gladys E. Reichard. "Elsie Clews Parsons". The Journal of American Folklore. Vol. 56, No. 219, Elsie Clews Parsons Memorial Number (January–March 1943), pp. 45–48. 6. Babcock, Barbara A.; Parezo, Nancy J. (1988). Daughters of the Desert: Women Anthropologists and the Native American Southwest, 1880–1980. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 15. ISBN 978-0-8263-1087-3. 7. "Elsie Clews Parsons Prize". AESonline.org. American Ethnological Society. 2012-02-01. Archived from the original on 2012-05-31. Retrieved 2012-04-24. 8. "2007 Elsie Clews Parsons Prize for Best Graduate Student Paper". AESonline.org. American Ethnological Society. 2007-04-02. Archived from the original on 2007-06-25. Retrieved 2007-05-16. 9. "Miss Clews is Married". The New York Times. Newport, Massachusetts. 1900-09-02. p. 5. Retrieved 2010-01-01. 10. Kennedy, Robert C. "Cartoon of the Day". HarpWeek. HarpWeek, LLC. Retrieved 2007-05-16. 11. "Parsons, Elsie Clews". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-16. 12. "Revolt, They Said". andreageyer.info. Retrieved 2017-06-19. 13. Gladys A. Reichard (June 20, 1950). The Elsie Clews Parsons collection Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society vol. 94, No. 3, Studies of Historical Documents in the Library of the American Philosophical Society. pp. 308–309. 14. Strong, Pauline (2013). "Parsons, Elsie Clews". Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology, ed. R. Jon McGee and Richard L. Warms. 2: 609–612. 15. Grande, Sandy (2015). Red Pedagogy: Native American Social and Political Thought (10th anniversary [2nd] ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 190. ISBN 9781610489881. 16. Jacobs, Margaret D. (1999). Engendered encounters: feminism and Pueblo cultures, 1879–1934. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 102. ISBN 978-0-8032-7609-3. 17. Eby, Clare Virginia (2014). Until Choice Do Us Part. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. preface. ISBN 978-0-226-08597-5. |

参考文献 1. 「行動心理学者ヘンリー・マキルベイン・パーソンズ氏、92歳で死去」。ワシントン・ポスト。2004年8月1日。 2. スピア、レスリー、A. L. クロエバー共著。「エルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズ」、『アメリカ人類学者』新シリーズ第45巻第2号、アメリカ民族学会創立100周年記念号(1943年4月~6月)、244~255頁。JSTOR 663274。 3. デル・モンテ、キャスリーン;カレン・バックマン;キャサリン・クライン;ブリジット・マコート(1999年3月19日)。「エルシー・クルーズ・パーソ ンズ」。『女性人類学者たちの祝典』。サウスフロリダ大学。2007年6月7日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2007年5月16日に取得。 4. 「エルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズ文書」。アメリカ哲学会。2007年3月10日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2007年5月16日に取得。 5. グラディス・E・ライチャード。「エルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズ」。『アメリカ民俗学ジャーナル』。第56巻、第219号、エルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズ追悼号(1943年1月~3月)、45~48ページ。 6. バブコック, バーバラ・A.; パレゾ, ナンシー・J. (1988). 『砂漠の娘たち:女性人類学者とネイティブアメリカン南西部、1880–1980』. ニューメキシコ大学出版局. pp. 15. ISBN 978-0-8263-1087-3. 7. 「エルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズ賞」. AESonline.org. アメリカ民族学会. 2012年2月1日. 2012年5月31日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2012年4月24日に閲覧. 8. 「2007年度最優秀大学院生論文エルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズ賞」. AESonline.org. アメリカ民族学会. 2007年4月2日. 2007年6月25日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた. 2007年5月16日に取得. 9. 「ミス・クルーズが結婚」. ニューヨーク・タイムズ. マサチューセッツ州ニューポート. 1900年9月2日. p. 5. 2010年1月1日に取得. 10. ケネディ、ロバート・C. 「今日の漫画」. ハープウィーク. ハープウィーク社. 2007年5月16日閲覧. 11. 「パーソンズ、エルシー・クルース」. ブリタニカ百科事典. ブリタニカ百科事典オンライン. 2007年. 2007年5月16日閲覧. 12. 「反乱だ、彼らは言った」. andreageyer.info. 2017年6月19日閲覧. 13. グラディス・A・ライチャード (1950年6月20日). 『エルシー・クルーズ・パーソンズ・コレクション』 アメリカ哲学会紀要 第94巻第3号, アメリカ哲学会図書館所蔵歴史文書研究. pp. 308–309. 14. Strong, Pauline (2013). 「Parsons, Elsie Clews」. Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology, ed. R. Jon McGee and Richard L. Warms. 2: 609–612. 15. Grande, Sandy (2015). 『赤い教育学:ネイティブアメリカンの社会・政治思想』(10周年記念[第2版])。メリーランド州ラナム:ローマン&リトルフィールド。190頁。ISBN 9781610489881。 16. ジェイコブズ、マーガレット・D.(1999)。『ジェンダー化された出会い:フェミニズムとプエブロ文化、1879–1934年』。リンカーン、ネブラスカ州:ネブラスカ大学出版局。102頁。ISBN 978-0-8032-7609-3。 17. エビー、クレア・バージニア(2014)。『選択が我らを分かつまで』。シカゴおよびロンドン:シカゴ大学出版局。序文。ISBN 978-0-226-08597-5。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆