ルイ・ボナパルトのブリュメール18日

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

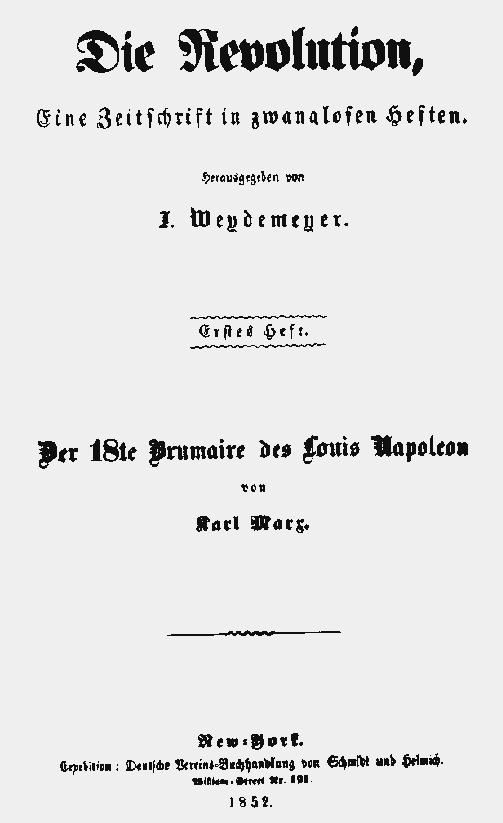

☆ 『ルイ・ナポレオンの18ブリュメール』(ドイツ語: Der 18te Brumaire des Louis Napoleon)は、カール・マルクスが1851年12月から1852年3月にかけて書いたエッセイであり、1852年にマルクス主義者のジョセフ・ ヴァイデマイヤーがニューヨークで発行していたドイツの月刊誌『革命』に掲載された。マルクスによる序文が付いた1869年のハンブルク版など、後の英語 版のタイトルは『ルイ・ボナパルトの18ブリュメール』(The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte)であった。 このクーデターによって、第二共和政の大統領でナポレオン・ボナパルトの甥であるルイ=ナポレオン・ボナパルトがナポレオン3世として第二帝政の皇帝と なった。資本主義と階級闘争が、「グロテスクな凡庸者が英雄の役割を果たす」ことを可能にする条件をどのように作り出したかを説明しようとするものであ る。マルクスは、ブルジョアジー、小ブルジョアジー、農民、革命家、社会民主主義者など、さまざまな集団の分裂と同盟について述べ、1848年の革命にも かかわらず、どの集団も優位に立てなかったことが、王政の再興につながったことを説明している。マルクスは、第二帝政を「ボナパルティズム」国家と表現し ている。ボナパルティズム国家は、単一の階級の利益を代表することなく、半独立的になるという点で、階級支配の道具としての国家というマルクス主義の基本 概念の例外である(→「ルイ・ボナパルトのブリュメール18日(テキスト本文)」)。

| The

Eighteenth

Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (German: Der 18te Brumaire des Louis

Napoleon) is an essay written by Karl Marx between December 1851 and

March 1852, and originally published in 1852 in Die Revolution, a

German monthly magazine published in New York City by Marxist Joseph

Weydemeyer. Later English editions, such as the 1869 Hamburg edition

with a preface by Marx, were entitled The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis

Bonaparte.[citation needed] The essay serves as a major historiographic

application of Marx's theory of historical materialism. The Eighteenth Brumaire focuses on the 1851 French coup d'état, by which Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, president of the Second Republic and Napoléon Bonaparte's nephew, became emperor of the Second French Empire as Napoleon III. It seeks to explain how capitalism and class struggle created conditions which enabled "a grotesque mediocrity to play a hero's part". Marx describes the divisions and alliances among the bourgeoisie, the petty bourgeoisie, the peasantry, revolutionaries, and social democrats, among other groups, and how a lack of dominance of any one group led to the re-emergence of monarchy, despite the Revolution of 1848. Marx describes the Second Empire as a "Bonapartist" state, an exception to the basic Marxist conception of the state as an instrument of class rule in that the Bonapartist state becomes semi-autonomous, representing the interests of no single class. |

『ルイ・ナポレオンの18ブリュメール』(ドイツ語: Der

18te Brumaire des Louis

Napoleon)は、カール・マルクスが1851年12月から1852年3月にかけて書いたエッセイであり、1852年にマルクス主義者のジョセフ・

ヴァイデマイヤーがニューヨークで発行していたドイツの月刊誌『革命』に掲載された。マルクスによる序文が付いた1869年のハンブルク版など、後の英語

版のタイトルは『ルイ・ボナパルトの18ブリュメール』(The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis

Bonaparte)であった。 このクーデターによって、第二共和政の大統領でナポレオン・ボナパルトの甥であるルイ=ナポレオン・ボナパルトがナポレオン3世として第二帝政の皇帝と なった。資本主義と階級闘争が、「グロテスクな凡庸者が英雄の役割を果たす」ことを可能にする条件をどのように作り出したかを説明しようとするものであ る。マルクスは、ブルジョアジー、小ブルジョアジー、農民、革命家、社会民主主義者など、さまざまな集団の分裂と同盟について述べ、1848年の革命にも かかわらず、どの集団も優位に立てなかったことが、王政の再興につながったことを説明している。マルクスは、第二帝政を「ボナパルティズム」国家と表現し ている。ボナパルティズム国家は、単一の階級の利益を代表することなく、半独立的になるという点で、階級支配の道具としての国家というマルクス主義の基本 概念の例外である。 |

| Significance The Eighteenth Brumaire is regarded by the social historian C. J. Coventry as the first social history, the base model or template for E. P. Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class (1963).[1] Social history gained popularity in the 1960s. According to Oliver Cussen, the rise of cultural history in the 1990s, in line with neoliberal capitalism, saw Marx's perception of the necessity of revolutionary change replaced with Alexis de Tocqueville's elitist pessimism that popular revolt would only result in despots.[2] The Eighteenth Brumaire, along with Marx's contemporary writings on English politics and The Civil War in France, is a principal source for understanding Marx's theory of the capitalist state.[3] Political scientist Robert C. Tucker describes Marx's analysis of Louis Bonaparte's rise to power and rule as a "prologue to later Marxist thought on the nature and meaning of fascism." Louis Bonaparte's regime has been interpreted as a precursor to 20th-century fascism.[4] Two of Marx's most recognizable quotes appear in the essay. The first is on history repeating itself: "Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce". The second concerns the role of the individual in history: "Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living." |

意義 社会史家のC・J・コヴェントリーは、『18ブルメール』を最初の社会史とみなしており、E・P・トンプソンの『The Making of the English Working Class』(1963年)の基本モデルあるいは雛形となっている[1]。オリヴァー・キュッセンによれば、1990年代の文化史の台頭は、ネオリベラル 資本主義に沿ったものであり、革命的変化の必要性に対するマルクスの認識が、民衆の反乱は専制君主を生むだけだというアレクシス・ド・トクヴィルのエリー ト主義的悲観主義に取って代わられた[2]。 18ブルメール』は、マルクスのイギリス政治に関する同時代の著作やフランスにおける『内戦』とともに、マルクスの資本主義国家論を理解するための主要な 資料である[3]。 政治学者のロバート・C・タッカーは、ルイ・ボナパルトの権力獲得と支配に関するマルクスの分析を、「ファシズムの性質と意味に関する後のマルクス主義思 想のプロローグ」と表現している。ルイ・ボナパルトの政権は、20世紀のファシズムの先駆けとして解釈されている[4]。 このエッセイには、マルクスの最もよく知られた引用が2つ登場する。ひとつは、歴史は繰り返すということである: 「ヘーゲルはどこかで、すべての偉大な世界史的事実と人物は、いわば二度現れると述べている。一度目は悲劇として、二度目は茶番としてである」。第二は、 歴史における個人の役割に関するものである: 「人は自分の歴史を作るが、自分の好きなように作るのではない。自分で選んだ状況のもとで作るのではなく、過去から与えられ、伝えられてきた、すでに存在 する状況のもとで作るのである。すべての死んだ世代の伝統は、生きている者の脳みそに悪夢のように重くのしかかる。」 |

| Contents The title refers to the coup of 18 Brumaire in which Napoleon seized power in revolutionary France (9 November 1799, or 18 Brumaire Year VIII in the French Republican Calendar), in order to contrast it with the 1851 French coup d'état. In the preface to the second edition of The Eighteenth Brumaire, Marx stated that the purpose of this essay was to "demonstrate how the class struggle in France created circumstances and relationships that made it possible for a grotesque mediocrity to play a hero's part."[5] The Eighteenth Brumaire presents a taxonomy of the mass of the bourgeoisie, which Marx says impounded the republic like its property, as consisting of: the large landowners, the aristocrats of finance and big industrialists, the high dignitaries of the army, the university, the church, the bar, the academy, and the press.[6][7] |

内容 タイトルは、革命期のフランスでナポレオンが権力を掌握したブリュメール18世のクーデター(1799年11月9日、フランス共和暦8年ブリュメール18 世)を指し、1851年のフランスのクーデターと対比させるためである。 マルクスは『18ブリュメール』第2版の序文で、この小論の目的は「フランスにおける階級闘争が、グロテスクな凡庸者が英雄の役割を果たすことを可能にす る状況と関係をいかに作り出したかを示す」ことであると述べている[5]。 18ブリュメール』では、マルクスが共和国を財産のように囲い込んだとするブルジョワジーの大衆を、大土地所有者、金融貴族、大実業家、軍隊の高官、大 学、教会、法曹界、アカデミー、報道機関であると分類している[6][7]。 |

| "First as tragedy, then as farce" The opening lines of the book are the source of one of Marx's most quoted and misquoted[8] statements, that historical entities appear two times, "the first as tragedy, then as farce" (das eine Mal als Tragödie, das andere Mal als Farce), referring respectively to Napoleon I and to his nephew Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III): Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce. Caussidière for Danton, Louis Blanc for Robespierre, the Montagne of 1848 to 1851 for the Montagne of 1793 to 1795, the nephew for the uncle. The same caricature occurs in the circumstances of the second edition of The Eighteenth Brumaire.[9] Marx's sentiment echoed an observation made by Friedrich Engels at exactly the same time Marx began work on this book. In a letter to Marx of 3 December 1851, Engels wrote from Manchester: ... it really seems as though old Hegel, in the guise of the World Spirit, were directing history from the grave and, with the greatest conscientiousness, causing everything to be re-enacted twice over, once as grand tragedy and the second time as rotten farce, Caussidière for Danton, L. Blanc for Robespierre, Barthélemy for Saint-Just, Flocon for Carnot, and the moon-calf together with the first available dozen debt-encumbered lieutenants for the little corporal and his band of marshals. Thus the 18th Brumaire would already be upon us.[10] Yet this motif appeared even earlier, in Marx's 1837 unpublished novel Scorpion and Felix, this time with a comparison between the first Napoleon and King Louis Philippe: Every giant ... presupposes a dwarf, every genius a hidebound philistine. ... The first are too great for this world, and so they are thrown out. But the latter strike root in it and remain. ... Caesar the hero leaves behind him the play-acting Octavianus, Emperor Napoleon the bourgeois king Louis Philippe.[11] Marx's comment is most likely about Hegel's Lectures on the Philosophy of History (1837), Part III: "The Roman World", Section II: "Rome from the Second Punic War to the Emperors", regarding Caesar: But it became immediately manifest that only a single will could guide the Roman State, and now the Romans were compelled to adopt that opinion; since in all periods of the world a political revolution is sanctioned in men’s opinions, when it repeats itself. Thus Napoleon was twice defeated, and the Bourbons twice expelled. By repetition that which at first appeared merely a matter of chance and contingency becomes a real and ratified existence. |

「最初は悲劇として、次に茶番劇として この本の冒頭の一節は、マルクスの最も引用され、誤引用された[8]発言の一つである、歴史的実体は二度現れる、「最初は悲劇として、次に茶番として」 (das eine Mal als Tragödie, das andere Mals Farce)、それぞれナポレオン1世とその甥のルイ・ナポレオン(ナポレオン3世)を指している: ヘーゲルはどこかで、すべての偉大な世界史的事実や人物は、いわば二度現れると述べている。一度目は悲劇として、二度目は茶番劇としてである。コシディ エールはダントンに、ルイ・ブランはロベスピエールに、1848年から1851年のモンターニュは1793年から1795年のモンターニュに、甥は叔父 に。同じ風刺画が『18ブリュメール』第2版の状況にも見られる[9]。 マルクスのこの感情は、マルクスが本書の執筆を開始したのとまったく同じ時期にフリードリヒ・エンゲルスが行った観察と呼応していた。1851年12月3 日、エンゲルスはマンチェスターからマルクスに宛てた手紙の中でこう書いている: 老いたヘーゲルが、世界精神を装って、墓場から歴史を指揮しているかのようであり、最大の良心をもって、すべてを二度にわたって、一度目は壮大な悲劇とし て、二度目は腐った茶番劇として、再演させているかのようである。ダントンにはコシディエールを、ロベスピエールにはL.ブランを、サン=ジュストにはバ ルテルミーを、カルノにはフロコンを、小伍長と彼の元帥一行には、借金を背負わされた尉官十数名と月の子牛を配した。こうして、第18回ブリュメールはす でに目前に迫っていたのである[10]。 しかし、このモチーフはもっと以前、1837年にマルクスが未発表で発表した小説『サソリとフェリックス』(Scorpion and Felix)に、今度は初代ナポレオンとルイ・フィリップ国王の比較とともに登場している: あらゆる巨人は......小人を前提とし、あらゆる天才は、かくれた俗人を前提とする。... 前者はこの世には大きすぎる、だから捨てられる。しかし、後者はこの世に根を下ろし、残る。... 英雄カエサルは、芝居がかったオクタヴィアヌスを、皇帝ナポレオンは、ブルジョワの王ルイ・フィリップを、その背後に残すのである[11]。 マルクスのコメントは、カエサルに関するヘーゲルの『歴史哲学講義』(1837年)の第三部「ローマ世界」、第二節「第二次ポエニ戦争から皇帝までのロー マ」についてのものである可能性が高い: しかし、ローマ国家を導くことができるのはただ一つの意志だけであることが直ちに明らかになり、今やローマ人はその意見を採用せざるを得なくなった。ナポ レオンは二度敗北し、ブルボン家は二度追放された。最初は単なる偶然と偶発の問題に過ぎなかったものが、繰り返されることによって、現実の批准された存在 となるのである。 |

| Band of the 10th of December Marxist philosophy |

12月10日のバンド マルクス主義哲学 |

| Further reading Rose, Margaret A. (1978). Reading the Young Marx and Engels: Poetry, Parody, and the Censor. London: Croon Helm. Cowling, Mark and Martin, James, eds. (2002). Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire (Post)modern Interpretations. London: Pluto Books. |

さらに読む Rose, Margaret A. (1978). 若きマルクスとエンゲルスを読む: 詩、パロディ、検閲官。London: Croon Helm. Cowling, Mark and Martin, James, eds. (2002). Marx's Eighteenth Brumaire (Post)modern Interpretations. London: Pluto Books. |

| External links The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (Chapters 1 & 7 translated by Saul K. Padover from the German edition of 1869; Chapters 2 through 6 are based on the third edition, prepared by Friedrich Engels (1885), as translated and published by Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1937.) Preface to the Second Edition (1869) The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Charles H. Kerr, Chicago, 1907. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, International Publishers, New York City, 1963. |

外部リンク ルイ・ナポレオンの18ブリュメール』(第1章と第7章は1869年のドイツ語版からソール・K・パドヴァーが翻訳、第2章から第6章はフリードリヒ・エ ンゲルスが作成した第3版(1885年)に基づく。) 第2版への序文(1869年) ルイ・ボナパルトの18ブリュメール』チャールズ・H・カー著、シカゴ、1907年 The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, International Publishers, New York City, 1963. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Eighteenth_Brumaire_of_Louis_Bonaparte |

|

| The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Der 18te Brumaire des Louis Napoleon, 1852 |

ルイ・ボナパルトのブリュメール18日(英訳からの翻訳) |

★VII, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Karl Marx 1852

| The social republic

appeared as a phrase, as a prophecy, on the threshold of the February

Revolution. In the June days of 1848, it was drowned in the blood of

the Paris proletariat, but it haunts the subsequent acts of the drama

like a ghost. The democratic republic announces its appearance. It is

dissipated on June 13, 1849, together with its deserting petty

bourgeois, but in its flight it redoubles its boastfulness. The

parliamentary republic together with the bourgeoisie takes possession

of the entire state; it enjoys its existence to the full, but December

2, 1851, buries it to the accompaniment of the anguished cry of the

coalesced royalists: “Long live the Republic!” The French bourgeoisie balked at the domination of the working proletariat; it has brought the lumpen proletariat to domination, with the Chief of the Society of December 10 at the head. The bourgeoisie kept France in breathless fear of the future terrors of red anarchy – Bonaparte discounted this future for it when, on December 4, he had the eminent bourgeois of the Boulevard Montmartre and the Boulevard des Italiens shot down at their windows by the drunken army of law and order. The bourgeoisie apotheosized the sword; the sword rules it. It destroyed the revolutionary press; its own press is destroyed. It placed popular meetings under police surveillance; its salons are placed under police supervision. It disbanded the democratic National Guard, its own National Guard is disbanded. It imposed a state of siege; a state of siege is imposed upon it. It supplanted the juries by military commissions; its juries are supplanted by military commissions. It subjected public education to the sway of the priests; the priests subject it to their own education. It jailed people without trial, it is being jailed without trial. It suppressed every stirring in society by means of state power; every stirring in its society is suppressed by means of state power. Out of enthusiasm for its moneybags it rebelled against its own politicians and literary men; its politicians and literary men are swept aside, but its moneybag is being plundered now that its mouth has been gagged and its pen broken. The bourgeoisie never tired of crying out to the revolution what St. Arsenius cried out to the Christians: “Fuge, tace, quiesce!” [“Flee, be silent, keep still!”] Bonaparte cries to the bourgeoisie: “Fuge, tace, quiesce!" The French bourgeoisie had long ago found the solution to Napoleon’s dilemma: “In fifty years Europe will be republican or Cossack.” It solved it in the “Cossack republic.” No Circe using black magic has distorted that work of art, the bourgeois republic, into a monstrous shape. That republic has lost nothing but the semblance of respectability. Present-day France was already contained in the parliamentary republic. It required only a bayonet thrust for the bubble to burst and the monster to leap forth before our eyes. |

社会共和国は、二月革命の入り口で、一つの言葉として、一つの予言とし

て現れた。1848年6月の日々、それはパリのプロレタリアートの血に溺れたが、その後も劇の幕間を幽霊のように彷徨い続ける。民主共和国がその登場を告

げる。1849年6月13日、それは離反した小市民階級と共に消え去るが、その逃走の中で虚栄心を倍増させる。議会制共和国はブルジョアジーと共に国家全

体を掌握し、その存在を存分に享受する。しかし1851年12月2日、結束した王党派の苦悶の叫び「共和国万歳!」と共に葬り去られる。 フランスブルジョアジーは労働者プロレタリアートの支配を拒んだ。そして12月10日協会の首領を先頭に、ルンペン・プロレタリアートを支配の座に押し上 げたのだ。ブルジョアジーはフランスを、赤い無政府主義の未来の恐怖に息もつかせぬほど震え上がらせた――ボナパルトは12月4日、モンマルトル大通りと イタリア人通りの著名なブルジョワたちを、窓辺で法と秩序の酔った軍隊に射殺させることで、この未来を葬り去ったのだ。ブルジョアジーは剣を神格化した。 剣がブルジョアジーを支配する。革命的な新聞を破壊した。自らの新聞が破壊される。民衆集会を警察監視下に置いたが、自らのサロンは警察の監督下に置かれ る。民主的な国民衛兵隊を解散させたが、自らの国民衛兵隊は解散させられる。戒厳令を敷いたが、戒厳令が敷かれる。陪審員を軍事委員会で置き換えたが、自 らの陪審員は軍事委員会に置き換えられる。公教育を聖職者の支配下に置いたが、聖職者が自らの教育で支配する。裁判なしに人民を投獄した。今や裁判なしに 投獄されている。国家権力で社会のあらゆる動揺を弾圧した。今や国家権力で自らの社会のあらゆる動揺が弾圧されている。金持ちへの熱狂から自らの政治家や 知識人に反旗を翻した。今や政治家や知識人は一掃され、口を封じられペンを折られた金持ちは略奪されている。ブルジョアジーは革命に対して、聖アルセニウ スがキリスト教徒に叫んだのと同じ言葉を飽きずに叫び続けた。「逃げよ、黙せ、静まれ!」と。ボナパルトはブルジョアジーに向かって叫ぶ。「逃げよ、黙 せ、静まれ!」と。 フランス・ブルジョアジーはとっくにナポレオンのジレンマの解決策を見出していた: 「五十年後、ヨーロッパは共和制かコサックの支配下にあるだろう」と。その答えは「コサック共和制」にあった。黒呪術を使うキルケのような者が、この芸術 品であるブルジョア共和制を怪物のような姿に変えたわけではない。この共和制が失ったのは、体裁だけの尊厳に過ぎない。現代のフランスは、すでに議会制共 和制の中に存在していた。泡がはじけ、怪物が我々の目の前に飛び出すには、銃剣の一突きさえあれば十分だったのだ。 |

| Why did the Paris proletariat not rise in revolt after December 2? The overthrow of the bourgeoisie had as yet been only decreed; the decree was not carried out. Any serious insurrection of the proletariat would at once have put new life into the bourgeoisie, reconciled it with the army, and insured a second June defeat for the workers. On December 4 the proletariat was incited by bourgeois and shopkeeper to fight. On the evening of that day several legions of the National Guard promised to appear, armed and uniformed, on the scene of battle. For the bourgeois and the shopkeeper had learned that in one of his decrees of December 2 Bonaparte had abolished the secret ballot and had ordered them to put a “yes” or “no” after their names on the official registers. The resistance of December 4 intimidated Bonaparte. During the night he had placards posted on all the street corners of Paris announcing the restoration of the secret ballot. The bourgeois and the shopkeeper believed they had gained their objective. Those who failed to appear next morning were the bourgeois and the shopkeeper. By a coup de main the night of December 1-2 Bonaparte had robbed the Paris proletariat of its leaders, the barricade commanders. An army without officers, averse to fighting under the banner of the Montagnards because of the memories of June, 1848 and 1849, and May, 1850, it left to its vanguard, the secret societies, the task of saving the insurrectionary honor of Paris, which the bourgeoisie had surrendered to the military so unresistingly that, subsequently, Bonaparte could disarm the National Guard with the sneering motive of his fear that its weapons would be turned against it by the anarchists! "This is the complete and final triumph of socialism!” Thus Guizot characterized December 2. But if the overthrow of the parliamentary republic contains within itself the germ of the triumph of the proletarian revolution, its immediate and obvious result was Bonaparte’s victory over parliament, of the executive power over the legislative power, of force without phrases over the force of phrases. In parliament the nation made its general will the law; that is, it made the law of the ruling class its general will. It renounces all will of its own before the executive power and submits itself to the superior command of an alien, of authority. The executive power, in contrast to the legislative one, expresses the heteronomy of a nation in contrast to its autonomy. France therefore seems to have escaped the despotism of a class only to fall back under the despotism of an individual, and what is more, under the authority of an individual without authority. The struggle seems to be settled in such a way that all classes, equally powerless and equally mute, fall on their knees before the rifle butt. |

なぜパリのプロレタリアートは12月2日以降、反乱を起こさなかったのか? ブルジョアジーの打倒は、まだ布告されただけで実行されていなかった。プロレタリアートによる本格的な蜂起は、即座にブルジョアジーに新たな活力を与え、軍隊との和解をもたらし、労働者階級にとって二度目の6月敗北を確実なものにしたであろう。 12月4日、プロレタリアートはブルジョワと商店主によって戦いに駆り立てられた。その日の夕方、国民衛兵の数個連隊が武装し制服を着て戦場に現れると約 束していた。ブルジョワと商店主は、12月2日の布告の一つでボナパルトが秘密投票を廃止し、公式名簿に自分の名前の後に「賛成」か「反対」を記入するよ う命じたことを知っていたからだ。12月4日の抵抗はボナパルトを怯ませた。夜のうちに彼はパリの街角すべてに、秘密投票の復活を告げる張り紙を掲示させ た。ブルジョワと商店主は自らの目的を達成したと信じた。翌朝現れなかったのは、ブルジョワと商店主の方だった。 12月1日から2日にかけての夜、ボナパルトは奇襲によってパリのプロレタリアートから指導者たち、すなわちバリケード指揮官たちを奪い取った。将校なき 軍隊は、1848年6月、1849年、そして1850年5月の記憶ゆえに、モンタニャール派の旗の下で戦うことを嫌った。パリの反乱の名誉を守る任務は、 その先鋒である秘密結社に委ねられた。ブルジョワジーは抵抗もせずに軍にその名誉を明け渡したため、その後、 ボナパルトは国民衛兵を武装解除できたのだ。その口実は、武器が無政府主義者によって国民自身に向けられるのではないかという、嘲笑を帯びた恐れであっ た! 「これが社会主義の完全かつ最終的な勝利だ!」ギゾーは12月2日をこう評した。しかし議会制共和国の打倒がプロレタリア革命勝利の萌芽を内包していたと しても、その直接的かつ明白な結果は、ボナパルトの議会に対する勝利、行政権力の立法権力に対する勝利、空虚な言葉の力に対する実力の勝利であった。議会 において国民は、その総意を法律とした。すなわち支配階級の法律を総意としたのである。国民は行政権の前では自らの意志をすべて放棄し、異質な権威、すな わち権力への服従を余儀なくされる。立法権とは対照的に、行政権は国民の自律性に対する他律性を表現する。したがってフランスは、ある階級の専制から逃れ たかに見えたが、結局は個人の専制、しかも権威を持たない個人の権威の下に逆戻りした。闘争は、あらゆる階級が等しく無力で等しく沈黙し、銃床の前にひざ まずく形で決着したように見える。 |

| But the revolution is

thoroughgoing. It is still traveling through purgatory. It does its

work methodically. By December 2, 1851, it had completed half of its

preparatory work; now it is completing the other half. It first

completed the parliamentary power in order to be able to overthrow it.

Now that it has achieved this, it completes the executive power,

reduces it to its purest expression, isolates it, sets it up against

itself as the sole target, in order to concentrate all its forces of

destruction against it. And when it has accomplished this second half

of its preliminary work, Europe will leap from its seat and exult: Well

burrowed, old mole! [paraphrase from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Act 1, Scene

5: “Well said, old mole!”, also cited by Hegel in his Philosophy of

History] The executive power with its enormous bureaucratic and military organization, with its wide-ranging and ingenious state machinery, with a host of officials numbering half a million, besides an army of another half million – this terrifying parasitic body which enmeshes the body of French society and chokes all its pores sprang up in the time of the absolute monarchy, with the decay of the feudal system which it had helped to hasten. The seignorial privileges of the landowners and towns became transformed into so many attributes of the state power, the feudal dignitaries into paid officials, and the motley patterns of conflicting medieval plenary powers into the regulated plan of a state authority whose work is divided and centralized as in a factory. The first French Revolution, with its task of breaking all separate local, territorial, urban, and provincial powers in order to create the civil unity of the nation, was bound to develop what the monarchy had begun, centralization, but at the same time the limits, the attributes, and the agents of the governmental power. Napoleon completed this state machinery. The Legitimate Monarchy and the July Monarchy added nothing to it but a greater division of labor, increasing at the same rate as the division of labor inside the bourgeois society created new groups of interests, and therefore new material for the state administration. Every common interest was immediately severed from the society, countered by a higher, general interest, snatched from the activities of society’s members themselves and made an object of government activity – from a bridge, a schoolhouse, and the communal property of a village community, to the railroads, the national wealth, and the national University of France. Finally the parliamentary republic, in its struggle against the revolution, found itself compelled to strengthen the means and the centralization of governmental power with repressive measures. All revolutions perfected this machine instead of breaking it. The parties, which alternately contended for domination, regarded the possession of this huge state structure as the chief spoils of the victor. |

しかし革命は徹底的だ。今も煉獄を旅している。それは計画的に仕事を遂

行する。1851年12月2日までに準備作業の半分を終え、今や残りの半分を完成させようとしている。まず議会制の権力を完成させたのは、それを打倒する

ためだ。これを達成した今、革命は行政権を完成させ、それを最も純粋な形態に還元し、孤立させ、唯一の標的として自らに対峙させる。そうして破壊の全力を

その一点に集中させるのだ。この第二段階の準備作業を終えた時、ヨーロッパは席から飛び上がって歓喜するだろう。「よく掘ったな、老いたモグラよ!」

[シェイクスピア『ハムレット』第一幕第五場「よく言った、老いたモグラよ!」の意訳。ヘーゲルも『歴史哲学論』で引用] 膨大な官僚機構と軍事組織を擁し、広範かつ巧妙な国家機械を備え、50万の官吏に加えさらに50万の軍隊を従える行政権力――この恐るべき寄生体は、絶対 王政の時代に、自らが加速した封建制度の衰退と共に、フランス社会の体を絡め取り、その全ての毛穴を塞ぐようにして出現した。地主や都市の領主的特権は国 家権力の属性へと変容し、封建貴族は俸給官吏となり、中世の多様な対立する全権力構造は、工場のように分業化・中央集権化された国家権力の計画的な枠組み へと組み込まれた。 最初のフランス革命は、国民の市民的統一を創出するために、あらゆる分離された地方・領土・都市・地方の権力を打破するという任務を帯びていた。それは必 然的に、君主制が始めた中央集権化を発展させることになったが、同時に政府権力の限界、属性、そして執行者も発展させた。ナポレオンはこの国家機構を完成 させた。正統王政と七月王政がこれに追加したのは、分業のさらなる深化だけだった。ブルジョワ社会内部の分業が新たな利益集団を生み出し、それゆえ国家行 政の新たな材料を増やすのと同等の速度で、分業は拡大したのだ。あらゆる共同の利益は、直ちに社会から切り離され、より高次の普遍的利益によって対抗され た。それは社会成員自身の活動から奪い取られ、政府活動の目的とされた――村の共同体の橋や校舎、共有財産から、鉄道、国民財産、フランス国立大学に至る まで。結局、議会制共和国は革命との闘いの中で、抑圧的手段による政府権力の強化と中央集権化を余儀なくされた。あらゆる革命は、この機構を破壊するどこ ろか、むしろ完成させたのである。支配権を争って交互に台頭した諸政党は、この巨大な国家機構の掌握こそが勝利者の主要な戦利品と見なした。 |

| But under the absolute monarchy,

during the first Revolution, and under Napoleon the bureaucracy was

only the means of preparing the class rule of the bourgeoisie. Under

the Restoration, under Louis Philippe, under the parliamentary

republic, it was the instrument of the ruling class, however much it

strove for power of its own. Only under the second Bonaparte does the state seem to have made itself completely independent. The state machinery has so strengthened itself vis-à-vis civil society that the Chief of the Society of December 10 suffices for its head – an adventurer dropped in from abroad, raised on the shoulders of a drunken soldiery which he bought with whisky and sausages and to which he has to keep throwing more sausages. Hence the low-spirited despair, the feeling of monstrous humiliation and degradation that oppresses the breast of France and makes her gasp. She feels dishonored. And yet the state power is not suspended in the air. Bonaparte represented a class, and the most numerous class of French society at that, the small-holding peasants. Just as the Bourbons were the dynasty of the big landed property and the Orleans the dynasty of money, so the Bonapartes are the dynasty of the peasants, that is, the French masses. The chosen of the peasantry is not the Bonaparte who submitted to the bourgeois parliament but the Bonaparte who dismissed the bourgeois parliament. For three years the towns had succeeded in falsifying the meaning of the December 10 election and in cheating the peasants out of the restoration of the Empire. The election of December 10, 1848, has been consummated only by the coup d’état of December 2, 1851. The small-holding peasants form an enormous mass whose members live in similar conditions but without entering into manifold relations with each other. Their mode of production isolates them from one another instead of bringing them into mutual intercourse. The isolation is furthered by France’s poor means of communication and the poverty of the peasants. Their field of production, the small holding, permits no division of labor in its cultivation, no application of science, and therefore no multifariousness of development, no diversity of talent, no wealth of social relationships. Each individual peasant family is almost self-sufficient, directly produces most of its consumer needs, and thus acquires its means of life more through an exchange with nature than in intercourse with society. A small holding, the peasant and his family; beside it another small holding, another peasant and another family. A few score of these constitute a village, and a few score villages constitute a department. Thus the great mass of the French nation is formed by the simple addition of homologous magnitudes, much as potatoes in a sack form a sack of potatoes. Insofar as millions of families live under conditions of existence that separate their mode of life, their interests, and their culture from those of the other classes, and put them in hostile opposition to the latter, they form a class. Insofar as there is merely a local interconnection among these small-holding peasants, and the identity of their interests forms no community, no national bond, and no political organization among them, they do not constitute a class. They are therefore incapable of asserting their class interest in their own name, whether through a parliament or a convention. They cannot represent themselves, they must be represented. Their representative must at the same time appear as their master, as an authority over them, an unlimited governmental power which protects them from the other classes and sends them rain and sunshine from above. The political influence of the small-holding peasants, therefore, finds its final expression in the executive power which subordinates society to itself. |

しかし絶対君主制下、第一次革命期、そしてナポレオン統治下において、官僚機構はブルジョアジーの階級支配を準備する手段に過ぎなかった。復古王政期、ルイ・フィリップ統治期、議会制共和制下では、たとえ自らの権力獲得をいかに図ろうとも、それは支配階級の道具であった。 第二のボナパルト統治下においてのみ、国家は完全に独立した存在となったように見える。国家機構は市民社会に対してこれほどまでに強大化したため、その頂 点には12月10日協会の首領が就くだけで十分である――国外から飛び込んできた冒険者で、ウイスキーとソーセージで買収した酔っ払いの兵士たちの肩に乗 せられ、今もなおソーセージを投げ続けなければならない存在だ。故にフランス国民の胸を圧迫し、息を詰まらせる、気力を失った絶望感、途方もない屈辱と堕 落の感覚が生まれるのだ。フランスは辱めを受けたと感じている。 しかし国家権力は宙に浮いているわけではない。ボナパルトはある階級、それもフランス社会で最も数が多い小作農の階級を代表していた。 ブルボン家が大地主の王朝であり、オルレアン家が金権の王朝であったように、ボナパルト家は農民、すなわちフランス大衆の王朝なのである。農民の選んだの は、ブルジョア議会に従ったボナパルトではなく、ブルジョア議会を解散させたボナパルトである。三年間、都市は12月10日の選挙の意味を歪め、農民から 帝政復古を騙し取ることに成功していた。1848年12月10日の選挙は、1851年12月2日のクーデターによって初めて完結したのである。 小作農は巨大な集団を形成しているが、その成員は似たような条件で生活しているものの、互いに多様な関係を築くことはない。彼らの生産様式は相互交流をも たらすどころか、互いを孤立させる。この孤立は、フランスの貧弱な交通手段と農民の貧困によってさらに助長されている。彼らの生産の場である小作地は、耕 作における分業も科学の応用も許さず、したがって多様な発展も、才能の多様性も、豊かな社会関係も生まない。個々の農民家族はほぼ自給自足であり、消費需 要の大部分を直接生産するため、生活の手段を社会との交流よりも自然との交換を通じて得る。小作地、農民とその家族。その隣にはまた別の小作地、別の農 民、別の家族。数十のこうした単位が村を構成し、数十の村が県を構成する。こうしてフランス国民の大多数は、袋の中のジャガイモがジャガイモの袋を形作る のと同様に、同種の単位の単純な集合によって形成されている。何百万もの家族が、自らの生活様式・利益・文化を他の階級から隔て、それらと敵対的な対立関 係に置くような生存条件のもとで生きる限り、彼らは階級を形成する。しかし、これらの小作農の間に単なる地域的な相互関係しか存在せず、彼らの利益の同一 性が共同体も国民的結束も政治的組織も形成しない限り、彼らは階級を構成しない。したがって彼らは、議会や大会を通じてであれ、自らの名において階級的利 益を主張することができない。自らを代表することはできず、代表される必要がある。その代表者は同時に彼らの主人として、彼らに対する権威として、他の階 級から彼らを守り、上から雨や日光を与える無制限の統治権力として現れねばならない。小作農の政治的影響力は、結局のところ、社会を自らに従属させる執行 権力において最終的な表現を見出すのである。 |

| Historical tradition gave rise

to the French peasants’ belief in the miracle that a man named Napoleon

would bring all glory back to them. And there turned up an individual

who claims to be that man because he bears the name Napoleon, in

consequence of the Code Napoleon, which decrees: “Inquiry into

paternity is forbidden.” After a twenty-year vagabondage and a series

of grotesque adventures the legend is consummated, and the man becomes

Emperor of the French. The fixed idea of the nephew was realized

because it coincided with the fixed idea of the most numerous class of

the French people. But, it may be objected, what about the peasant uprisings in half of France,[117] the raids of the army on the peasants, the mass incarceration and transportation of the peasants? Since Louis XIV, France has experienced no similar persecution of the peasants “on account of demagogic agitation.” [118] But let us not misunderstand. The Bonaparte dynasty represents not the revolutionary, but the conservative peasant; not the peasant who strikes out beyond the condition of his social existence, the small holding, but rather one who wants to consolidate his holding; not the countryfolk who in alliance with the towns want to overthrow the old order through their own energies, but on the contrary those who, in solid seclusion within this old order, want to see themselves and their small holdings saved and favored by the ghost of the Empire. It represents not the enlightenment but the superstition of the peasant; not his judgment but his prejudice; not his future but his past; not his modern Cevennes [A peasant uprising in the Cevennes mountains in 1702-1705] but his modern Vendée.[119] [A peasant-backed uprising against the French Revolution in the French province of Vendée, in 1793] The three years’ stern rule of the parliamentary republic freed a part of the French peasants from the Napoleonic illusion and revolutionized them, even though superficially; but the bourgeoisie violently repulsed them as often as they set themselves in motion. Under the parliamentary republic the modern and the traditional consciousness of the French peasant contended for mastery. The process took the form of an incessant struggle between the schoolmasters and the priests. The bourgeoisie struck down the schoolmasters. The peasants for the first time made efforts to behave independently vis-à-vis the government. This was shown in the continual conflict between the mayors and the prefects. The bourgeoisie deposed the mayors. Finally, during the period of the parliamentary republic, the peasants of different localities rose against their own offspring, the army. The bourgeoisie punished these peasants with sieges and executions. And this same bourgeoisie now cries out against the stupidity of the masses, the vile multitude that betrayed it to Bonaparte. The bourgeoisie itself has violently strengthened the imperialism of the peasant class; it has preserved the conditions that form the birthplaces of this species of peasant religion. The bourgeoisie, in truth, is bound to fear the stupidity of the masses so long as they remain conservative, and the insight of the masses as soon as they become revolutionary. |

歴史的伝統が、ナポレオンという名の男が彼らに栄光を取り戻すという奇

跡を、フランスの農民たちに信じさせた。そして現れたのは、ナポレオン法典が「父性の調査は禁じられる」と定める結果、ナポレオンという名を冠するゆえ

に、その男だと主張する人物であった。二十年にわたる放浪と一連の滑稽な冒険を経て、伝説は完結し、その男はフランス皇帝となる。甥の固執した考えが実現

したのは、それがフランス人民の大多数を占める階級の固執した考えと一致したからである。 しかし、反論があるかもしれない。フランス半分の地域で起きた農民蜂起[117]、軍による農民への襲撃、農民の大量投獄と流刑はどう説明するのか? ルイ14世以来、フランスは「扇動的な騒動を理由に」これほどの農民迫害を経験したことはない。[118] しかし誤解してはならない。ボナパルト王朝が代表するのは革命的な農民ではなく、保守的な農民である。自らの社会的存在条件である小作地を超えて打倒しよ うとする農民ではなく、むしろ自らの小作地を固守しようとする農民である。都市と結託して自らの力で旧体制を打倒しようとする農民ではなく、逆にこの旧体 制の中に堅固に閉じこもり、帝国の亡霊によって自らと小作地が守られ優遇されることを望む農民である。それは啓蒙ではなく農夫の迷信を、判断ではなく偏見 を、未来ではなく過去を、現代のセヴェンヌ[1702-1705年のセヴェンヌ山地における農民蜂起]ではなく現代のヴァンデ[1793年のフランス革命 に対する農民支持のヴァンデ地方蜂起]を体現する。 議会共和制の三年間の厳しい統治は、フランス農民の一部をナポレオン幻想から解放し、たとえ表面的であっても彼らを革命化した。しかしブルジョワジーは、 農民が動き出すたびに暴力的に彼らを押し返した。議会共和制下で、フランス農民の近代的意識と伝統的意識は支配権を争った。この過程は、教師と司祭の絶え 間ない闘争という形をとった。ブルジョワジーは教師を打ち倒した。農民たちは初めて政府に対して独立した行動を取ろうとした。これは市長と県知事の絶え間 ない対立に現れていた。ブルジョワジーは市長たちを罷免した。ついに議会共和制の時代に、異なる地域の農民たちは自らの生み出した軍隊に対して蜂起した。 ブルジョワジーは包囲と処刑でこれらの農民を懲らしめた。そして今、この同じブルジョアジーが、大衆の愚かさを嘆き、ボナパルトに裏切った卑しいマルチ チュードを非難している。ブルジョアジー自身が、農民階級の帝国主義を暴力的に強化してきたのだ。彼らは、この種の農民宗教が生まれる土壌となる条件を温 存してきた。ブルジョアジーは、大衆が保守的である限りは確かにその愚かさを恐れ、大衆が革命的になるやいなやその洞察力を恐れることになるのだ。 |

| In the uprisings after the coup

d’état, a part of the French peasants protested, arms in hand, against

their own vote of December 10, 1848. The school they had gone to since

1848 had sharpened their wits. But they had inscribed themselves in the

historical underworld; history held them to their word, and the

majority was still so implicated that precisely in the reddest

departments the peasant population voted openly for Bonaparte. In their

view, the National Assembly had hindered his progress. He has now

merely broken the fetters that the towns had imposed on the will of the

countryside. In some parts the peasants even entertained the grotesque

notion of a convention with Napoleon. After the first Revolution had transformed the semi-feudal peasants into freeholders, Napoleon confirmed and regulated the conditions in which they could exploit undisturbed the soil of France which they had only just acquired, and could slake their youthful passion for property. But what is now ruining the French peasant is his small holding itself, the division of the land and the soil, the property form which Napoleon consolidated in France. It is exactly these material conditions which made the feudal peasant a small-holding peasant and Napoleon an emperor. Two generations sufficed to produce the unavoidable result: progressive deterioration of agriculture and progressive indebtedness of the agriculturist. The “Napoleonic” property form, which at the beginning of the nineteenth century was the condition of the emancipation and enrichment of the French countryfolk, has developed in the course of this century into the law of their enslavement and their pauperism. And just this law is the first of the “Napoleonic ideas” which the second Bonaparte has to uphold. If he still shares with the peasants the illusion that the cause of their ruin is to be sought not in the small holdings themselves but outside them – in the influence of secondary circumstances – his experiments will shatter like soap bubbles when they come in contact with the relations of production. The economic development of small-holding property has radically changed the peasants’ relations with the other social classes. Under Napoleon the fragmentation of the land in the countryside supplemented free competition and the beginning of big industry in the towns. The peasant class was the ubiquitous protest against the recently overthrown landed aristocracy. The roots that small-holding property struck in French soil deprived feudalism of all nourishment. The landmarks of this property formed the natural fortification of the bourgeoisie against any surprise attack by its old overlords. But in the course of the nineteenth century the urban usurer replaced the feudal one, the mortgage replaced the feudal obligation, bourgeois capital replaced aristocratic landed property. The peasant’s small holding is now only the pretext that allows the capitalist to draw profits, interest, and rent from the soil, while leaving it to the agriculturist himself to see to it how he can extract his wages. The mortgage debt burdening the soil of France imposes on the French peasantry an amount of interest equal to the annual interest on the entire British national debt. Small-holding property, in this enslavement by capital toward which its development pushes it unavoidably, has transformed the mass of the French nation into troglodytes. Sixteen million peasants (including women and children) dwell in caves, a large number of which have but one opening, others only two and the most favored only three. Windows are to a house what the five senses are to the head. The bourgeois order, which at the beginning of the century set the state to stand guard over the newly emerged small holdings and fertilized them with laurels, has become a vampire that sucks the blood from their hearts and brains and casts them into the alchemist’s caldron of capital. The Code Napoléon is now nothing but the codex of distraints, of forced sales and compulsory auctions. To the four million (including children, etc.) officially recognized paupers, vagabonds, criminals, and prostitutes in France must be added another five million who hover on the margin of existence and either have their haunts in the countryside itself or, with their rags and their children, continually desert the countryside for the towns and the towns for the countryside. Therefore the interests of the peasants are no longer, as under Napoleon, in accord with, but are now in opposition to bourgeois interests, to capital. Hence they find their natural ally and leader in the urban proletariat, whose task it is to overthrow the bourgeois order. But “strong and unlimited government” - and this is the second “Napoleonic idea” that the second Napoleon has to carry out – is called upon to defend this “material order” by force. This “material order” also serves, in all Bonaparte’s proclamations, as the slogan against the rebellious peasants. |

クーデター後の蜂起において、フランス農民の一部は武器を手に、自らの

1848年12月10日の投票に抗議した。彼らが1848年から通った学校は彼らの知恵を研ぎ澄ませたのだ。だが彼らは歴史の暗部に自らを刻み込んだ。歴

史は彼らの言葉に縛りつけ、大多数は依然として深く関与していたため、最も革命的な県でさえ農民層は公然とボナパルトに投票した。彼らの見解では、国民議

会が彼の進路を阻んでいたのだ。今や彼は単に、都市が農村の意思に課した枷を打ち砕いただけである。一部地域では農民たちがナポレオンとの協調という滑稽

な考えさえ抱いていた。 第一次革命が半封建的農民を自由保有者に変えた後、ナポレオンは彼らがようやく獲得したフランスの土地を妨げられずに耕作し、財産への若々しい情熱を満足 させられる条件を確固たるものにし、規制した。しかし今やフランス農民を破滅させているのは、その小作地そのもの、土地と土壌の分割、ナポレオンがフラン スで固めた財産形態である。まさにこれらの物質的条件が、封建農民を小作農民とし、ナポレオンを皇帝にしたのだ。二世代で避けられない結果が生じた。農業 の漸進的衰退と農民の漸進的債務増加である。十九世紀初頭にはフランス農民の解放と富の源泉であった「ナポレオン的」財産形態は、この世紀の経過とともに 彼らの隷属と貧困化の法則へと変貌した。そしてまさにこの法則こそが、第二のボナパルトが擁護すべき「ナポレオン思想」の第一の柱である。もし彼が今なお 農民たちと幻想を共有し、彼らの破滅の原因は小作地そのものではなく、外部の二次的状況の影響に求められようとしているならば、その実験は生産関係に触れ た瞬間に石鹸の泡のように散り散りになるだろう。 小作地所有制の経済的発展は、農民と他の社会階級との関係を根本的に変えた。ナポレオン時代、農村における土地の細分化は、都市における自由競争と大工業 の萌芽を補完した。農民階級は、新たに打倒された土地貴族階級に対する遍在的な抗議であった。小作地所有制がフランスの土壌に打ち込んだ根は、封建制から 全ての栄養を奪った。この所有権の境界標は、旧支配者による奇襲攻撃に対するブルジョアジーの天然の要塞となった。しかし十九世紀の経過とともに、都市の 金貸しは封建的な金貸しに取って代わり、抵当権は封建的債務に取って代わり、ブルジョア資本は貴族的な土地所有に取って代わった。農民の小作地は今や、資 本家が土地から利潤、利子、地代を搾り取る口実に過ぎず、農民自身がどうやって賃金を捻出するかは彼ら自身に任されている。フランスの土地を圧迫する抵当 債務は、フランス農民に英国の国民債務全体の年間利子に相当する額の利子を課している。小作地所有制は、その発展が必然的に向かわせる資本による隷属化の 中で、フランス国民の大衆を穴居人に変えた。1600万人の農民(女性と子供を含む)が洞窟に住み、その多くは開口部が一つ、他は二つ、最も恵まれたもの でも三つしかない。窓は家にとって、五感が頭にとっての役割を果たす。世紀の初めに国家を動員して新たに生まれた小作地を守らせ、栄光の冠で飾ったブル ジョワ秩序は、今や吸血鬼と化した。小作人の心臓と脳髄から血を吸い取り、資本という錬金術師の大釜に投げ込むのだ。ナポレオン法典は今や、差し押さえと 強制売却、強制競売の法典に過ぎない。フランスで公式に認定された四百万の貧民(子供等を含む)、浮浪者、犯罪者、売春婦に加え、さらに五百万が生存の境 界をさまよい、田舎に居を構えるか、ぼろ服と子供を連れて田舎から町へ、町から田舎へと絶えず移動している。したがって農民の利益は、ナポレオン時代のよ うにブルジョワの利益と調和するものではなく、今や資本と対立する。ゆえに農民は、ブルジョワ秩序を打倒する使命を負う都市プロレタリアートに、自然な同 盟者かつ指導者を見出す。しかし「強固で無制限な政府」―これが第二のナポレオンが遂行すべき第二の「ナポレオン的理念」である―はこの「物質的秩序」を 武力で守るよう命じられている。この「物質的秩序」は、ボナパルトのあらゆる布告において、反乱を起こす農民に対するスローガンとしても機能している。 |

| In addition to the mortgage

which capital imposes on it, the small holding is burdened by taxes.

Taxes are the life source of the bureaucracy, the army, the priests,

and the court – in short, of the entire apparatus of the executive

power. Strong government and heavy taxes are identical. By its very

nature, small-holding property forms a basis for an all-powerful and

numberless bureaucracy. It creates a uniform level of personal and

economic relationships over the whole extent of the country. Hence it

also permits uniform action from a supreme center on all points of this

uniform mass. It destroys the aristocratic intermediate steps between

the mass of the people and the power of the state. On all sides,

therefore, it calls forth the direct intrusion of this state power and

the interposition of its immediate organs. Finally, it produces an

unemployed surplus population which can find no place either on the

land or in the towns and which perforce reaches out for state offices

as a sort of respectable alms, and provokes the creation of additional

state positions. By the new markets which he opened with bayonets, and

by the plundering of the Continent, Napoleon repaid the compulsory

taxes with interest. These taxes were a spur to the industry of the

peasant, whereas now they rob his industry of its last resources and

complete his defenselessness against pauperism. An enormous

bureaucracy, well gallooned and well fed, is the “Napoleonic idea”

which is most congenial to the second Bonaparte. How could it be

otherwise, considering that alongside the actual classes of society, he

is forced to create an artificial caste for which the maintenance of

his regime becomes a bread-and-butter question? Hence one of his first

financial operations was the raising of officials’ salaries to their

old level and the creation of new sinecures. Another “idée napoléonienne" [Napoleonic idea] is the domination of the priests as an instrument of government. But while at the time of their emergence the small-holding owners, in their accord with society, in their dependence on natural forces and submission to the authority which protected them from above, were naturally religious, now that they are ruined by debts, at odds with society and authority, and driven beyond their own limitations, they have become naturally irreligious. Heaven was quite a pleasing addition to the narrow strip of land just won, especially as it makes the weather; it becomes an insult as soon as it is thrust forward as a substitute for the small holding. The priest then appears as only the anointed bloodhound of the earthly police – another “idée napoléonienne.” The expedition against Rome will take place in France itself next time, but in a sense opposite from that of M. de Montalembert.[120] Finally, the culminating “idée napoléonienne” is the ascendancy of the army. The army was the “point d’ honneur” of the small-holding peasants, it was they themselves transformed into heroes, defending their new possessions against the outer world, glorifying their recently won nationhood, plundering and revolutionizing the world. The uniform was their own state costume; war was their poetry; the small holding, enlarged and rounded off in imagination, was their fatherland, and patriotism the ideal form of the sense of property. But the enemies whom the French peasant now has to defend his property against are not the Cossacks; they are the huissiers [bailiffs] and the tax collectors. The small holding no longer lies in the so-called fatherland but in the registry of mortgages. The army itself is no longer the flower of the peasant youth; it is the swamp flower of the peasant lumpen proletariat. It consists largely of replacements, of substitutes, just as the second Bonaparte is himself only a replacement, the substitute for Napoleon. It now performs its deeds of valor by hounding the peasants in masses like chamois, by doing gendarme duty; and if the natural contradictions of his system chase the Chief of the Society of December 10 across the French border, his army, after some acts of brigandage, will reap, not laurels, but thrashings. It is clear: All “idée napoléonienne” are ideas of the undeveloped small holding in the freshness of its youth; they are a contradiction to the outlived holdings. They are only the hallucinations of its death struggle, words transformed into phrases, spirits transformed into ghosts. But the parody of imperialism was necessary to free the mass of the French nation from the weight of tradition and to work out in pure form the opposition between state power and society. With the progressive deterioration of small-holding property, the state structure erected upon it collapses. The centralization of the state that modern society requires arises only on the ruins of the military-bureaucratic government machinery which was forged in opposition to feudalism. |

小作地は資本が課す抵当に加えて、税金の重荷を負わされている。税金は

官僚機構、軍隊、聖職者、宮廷――要するに執行権力全体の装置の生命線だ。強力な政府と重い税金は同一である。小作地という性質そのものが、全能で無数の

官僚機構の基盤を形成する。それは国土全域にわたり、人格間および経済的関係の均一な水準を生み出す。ゆえに、この均一な大衆のあらゆる点に対して、最高

権力中枢からの画一的な行動を可能とする。それは大衆と国家権力の間に存在する貴族的な中間段階を破壊する。したがってあらゆる面で、この国家権力の直接

的な介入と、その直轄機関の介入を招くのである。結局、土地にも都市にも居場所を見出せない失業した余剰人口を生み出し、彼らはやむなく一種の体面ある施

しとして国家職を求めるようになり、さらに新たな国家職の創設を促す。ナポレオンは銃剣で開拓した新市場と大陸の略奪によって、強制徴収した税金を利息付

きで返済したのである。これらの税は農民の勤労意欲を刺激するものだったが、今やその勤労から最後の資源を奪い、貧困に対する無防備状態を完成させる。立

派な装飾を施され、十分に養われた巨大な官僚機構こそが、第二のボナパルトにとって最も好ましい「ナポレオン的理念」である。社会の実際の階級とは別に、

彼は自らの体制維持が生活の糧となる人工的な階級を創出しざるを得ないのだから、当然のことだ。だから彼の最初の財政措置の一つは、役人の給与を以前の水

準に引き上げ、新たな役職を創設することだった。 もう一つの「ナポレオン的理念」は、政府の道具としての聖職者支配である。しかし小作農が台頭した当時、彼らは社会と調和し、自然の力に依存し、上から守 る権威に従属していたため、自然に宗教的であった。ところが今や借金で破綻し、社会や権威と対立し、自らの限界を超えて追い詰められた彼らは、自然に無宗 教となった。 天は、勝ち取ったばかりの狭い土地に、天候を司るという点で、なかなか心地よい付加物であった。しかし、小作地を代用するものとして押し付けられるやいな や、それは侮辱となる。司祭は、この世の警察の聖別された猟犬としてのみ現れる――これもまた「ナポレオン的観念」である。ローマに対する遠征は次回フラ ンス国内で行われるが、モンタランベール氏の主張とは逆の意味合いを持つ。[120] 最後に、頂点に達する「ナポレオン的発想」は軍隊の優位性である。軍隊は小作農たちの「名誉の象徴」であり、彼ら自身が英雄へと変貌した姿だった。新たな 所有地を外の世界から守り、勝ち取ったばかりの国民性を称え、世界を略奪し革命を起こす存在として。軍服は彼らの国家衣装であり、戦争は彼らの詩であっ た。想像の中で拡大・完成された小作地こそが彼らの祖国であり、愛国心は所有意識の理想的な形態であった。しかし今やフランス農民が財産を守るべき敵はコ サックではなく、執行役や徴税人である。小作地はもはやいわゆる祖国にはなく、抵当登記簿の中に存在する。軍隊そのものも、もはや農民青年の花ではない。 農民ルンペンプロレタリアートの沼の花だ。それは主に補充兵、代役兵で構成されている。第二のボナパルト自身が、ナポレオンの代役、補充兵に過ぎないのと 同じように。今やその武勇は、山羊のように群れをなす農民を追い立てる憲兵任務によって示される。そしてもし制度の矛盾が12月10日会衆の首領を国境を 越え追いやるなら、その軍隊は略奪行為の末、栄光ではなく鞭打ちを刈り取るだろう。 明らかなことだ:あらゆる「ナポレオン思想」は、未発達な小作農制が若さゆえの新鮮さの中で抱く思想である。それらは時代遅れの所有形態に対する矛盾だ。 死闘の幻覚に過ぎず、言葉は空虚なフレーズへ、精霊は亡霊へと変質した。しかし帝国主義のパロディは、フランス国民大衆を伝統の重圧から解放し、国家権力 と社会との対立を純粋な形で展開するために必要だった。 |

| The condition of the French

peasants provides us with the answer to the riddle of the general

elections of December 20 and 21, which bore the second Bonaparte up

Mount Sinai, not to receive laws but to give them. Obviously the bourgeoisie now had no choice but to elect Bonaparte. When the Puritans of the Council of Constance [1414-18][121] complained of the dissolute lives of the popes and wailed about the necessity for moral reform, Cardinal Pierre d’Ailly thundered at them: “Only the devil in person can still save the Catholic Church, and you ask for angels.” Similarly, after the coup d’état the French bourgeoisie cried out: Only the Chief of the Society of December 10 can still save bourgeois society! Only theft can still save property; only perjury, religion; bastardy, the family; disorder, order! As the executive authority which has made itself independent, Bonaparte feels it to be his task to safeguard “bourgeois order.” But the strength of this bourgeois order lies in the middle class. He poses, therefore, as the representative of the middle class and issues decrees in this sense. Nevertheless, he is somebody solely because he has broken the power of that middle class, and keeps on breaking it daily. He poses, therefore, as the opponent of the political and literary power of the middle class. But by protecting its material power he revives its political power. Thus the cause must be kept alive, but the effect, where it manifests itself, must be done away with. But this cannot happen without small confusions of cause and effect, since in their interaction both lose their distinguishing marks. New decrees obliterate the border line. Bonaparte knows how to pose at the same time as the representative of the peasants and of the people in general, as a man who wants to make the lower classes happy within the framework of bourgeois society. New decrees cheat the “true socialists” [122] of their governmental skill in advance. But above all, Bonaparte knows how to pose as the Chief of the Society of December 10, as the representative of the lumpen proletariat to which he himself, his entourage, his government, and his army belong, and whose main object is to benefit itself and draw California lottery prizes from the state treasury. And he confirms himself as Chief of the Society of December 10 with decrees, without decrees, and despite decrees. This contradictory task of the man explains the contradictions of his government, the confused groping which tries now to win, now to humiliate, first one class and then another, and uniformly arrays all of them against him; whose uncertainty in practice forms a highly comical contrast to the imperious, categorical style of the government decrees, a style slavishly copied from the uncle. Industry and commerce, hence the business affairs of the middle class, are to prosper in hothouse fashion under the strong government: the grant of innumerable railroad concessions. But the Bonapartist lumpen proletariat is to enrich itself: those in the know play tripotage [underhand dealings] on the Exchange with the railroad concessions. But no capital is forthcoming for the railroads: obligation of the Bank to make advances on railroad shares. But at the same time the Bank is to be exploited for personal gain and therefore must be cajoled: release the Bank from the obligation to publish its report weekly; leonine [from Aesop’s fable about the lion who made a contract in which one partner got all the profits and the other all the disadvantages] agreement of the Bank with the government. The people are to be given employment: initiation of public works. But the public works increase the people’s tax obligations: hence reduction of taxes by an attack on the rentiers, by conversion of the 5-percent bonds into 4½-percent. But the middle class must again receive a sweetening: hence a doubling of the wine tax for the people, who buy wine retail, and a halving of the wine tax for the middle class, which drinks it wholesale; dissolution of the actual workers’ associations, but promises of miraculous future associations. The peasants are to be helped: mortgage banks which hasten their indebtedness and accelerate the concentration of property. But these banks are to be used to make money out of the confiscated estates of the House of Orleans; no capitalist wants to agree to this condition, which is not in the decree, and the mortgage bank remains a mere decree, etc., etc. |

フランス農民の境遇こそが、12月20日と21日の総選挙という謎の答えを我々に与える。この選挙は第二のボナパルトをシナイ山へと押し上げたのだ。しかし彼は法律を受け取るためではなく、与えるために登ったのである。 明らかにブルジョワジーには、今やボナパルトを選出する以外に選択肢はなかった。コンスタンツ公会議[1414-18][121]の清教徒たちが教皇たち の放蕩な生活を非難し、道徳改革の必要性を嘆いた時、ピエール・ダリイ枢機卿は彼らに向かってこう怒鳴った。「カトリック教会を救えるのはもはや悪魔の人 格だけだ。それなのに君たちは天使を求めているのか」 同様に、クーデター後のフランスブルジョアジーは叫んだ:10月10日協会の首領だけが、今なおブルジョア社会を救える!窃盗だけが財産を救い、偽証だけ が宗教を救い、私生児だけが家族を救い、混乱だけが秩序を救うのだ! 独立した執行権力として、ボナパルトは「ブルジョワ秩序」を守ることを自らの任務と感じている。しかしこのブルジョワ秩序の力は中産階級にある。ゆえに彼 は中産階級の代表を装い、その趣旨の法令を発する。とはいえ、彼が存在意義を持つのは、まさにその中産階級の力を打ち砕き、日々打ち砕き続けているからに 他ならない。したがって彼は、中産階級の政治的・文化的権力に対する敵対者として振る舞う。しかしその物質的権力を保護することで、彼は中産階級の政治的 権力を蘇らせる。ゆえに原因は存続させねばならないが、結果が現れる場ではそれを排除せねばならない。しかし原因と結果の相互作用において両者は区別を失 うため、この排除は原因と結果の些細な混同なしには起こりえない。新たな法令が境界線を消し去る。ボナパルトは、農民と民衆全体の代表者として、またブル ジョア社会の枠組み内で下層階級を幸福にしようとする人物として、同時に振る舞う術を知っている。新たな法令は「真の社会主義者」[122]から、彼らの 統治能力を事前に奪い取る。しかし何よりも、ボナパルトは12月10日協会の首領として、また自身とその側近、政府、軍隊が属するルンペン・プロレタリ アートの代表者として振る舞う術を知っている。その協会の主目的は自己利益の追求と、国庫からカリフォルニア宝くじの当選金のような利益を引き出すこと だ。そして彼は法令によって、法令なしに、法令に反してさえ、自らを12月10日協会の首領として確認する。 この矛盾した男の役割こそが、彼の政府の矛盾、ある階級を優遇し別の階級を屈辱させるという混乱した手探り、そして結局は全ての階級を敵に回すという矛盾 を説明している。その実践における不確実性は、叔父から盲目的に模倣した政府布告の威圧的で断定的な文体と、極めて滑稽な対照をなしている。 産業と商業、すなわち中産階級の事業は、強権的な政府のもとで温室育ちのように繁栄するはずだ。無数の鉄道特許の付与がその証左である。しかしボナパル ティストのルンペンプロレタリアートもまた富を蓄える。内情を知る者たちは、鉄道特許を駆使して証券取引所で裏取引(トリポタージュ)を繰り広げる。だが 鉄道建設資金は不足している。銀行に鉄道株への融資義務を課す。同時に銀行は人格の私利私欲のために搾取されるため、懐柔が必要だ。銀行の週次報告書公表 義務を免除する。銀行と政府の「獅子契約」(イソップ寓話に登場する、一方に全利益、他方に全不利益をもたらす契約を結んだ獅子の話に由来)が結ばれる。 人民に雇用を与える:公共事業の開始。だが公共事業は人民の税負担を増大させる:よって地代収奪者への攻撃、5%債券を4.5%に転換することで減税を図 る。しかし中産階級には再び甘味が必要だ。だから小売でワインを買う庶民の酒税は倍増し、卸で飲む中産階級の酒税は半減する。実際の労働者組合は解散する が、奇跡的な未来の組合を約束する。農民を助けるという:彼らの負債を加速し、財産の集中を促進する抵当銀行だ。だがこれらの銀行は、オルレアン家の没収 された領地から金を搾り取るために利用される。この条件は法令には記載されておらず、資本家はこの条件に同意したがらない。したがって抵当銀行は単なる法 令に過ぎない、などなど。 |

| Bonaparte would like to appear

as the patriarchal benefactor of all classes. But he cannot give to one

without taking from another. Just as it was said of the Duke de Guise

in the time of the Fronde that he was the most obliging man in France

because he gave all his estates to his followers, with feudal

obligations to him, so Bonaparte would like to be the most obliging man

in France and turn all the property and all the labor of France into a

personal obligation to himself. He would like to steal all of France in

order to make a present of it to France, or rather in order to buy

France anew with French money, for as the Chief of the Society of

December 10 he must buy what ought to belong to him. And to the

Institution of Purchase belong all the state institutions, the Senate,

the Council of State, the Assembly, the Legion of Honor, the military

medals, the public laundries, the public works, the railroads, the

general staff, the officers of the National Guard, the confiscated

estates of the House of Orleans. The means of purchase is obtained by

selling every place in the army and the government machinery. But the

most important feature of this process, by which France is taken in

order to give to her, are the percentages that find their way into the

pockets of the head and the members of the Society of December 10

during the turnover. The witticism with which Countess L., the mistress

of M. de Morny, characterized the confiscation of the Orleans estates –

“It is the first vol [the word means both “flight” and “theft"] of the

eagle” – is applicable to every flight of this eagle, who is more like

a raven.[123] He and his follower; call out to one another like that

Italian Carthusian admonishing the miser who ostentatiously counted the

goods on which he could still live for years: “Tu fai conto sopra i

beni, bisogna prima far il conto sopra gli anni” [Thou countest thy

goods, thou shouldst first count thy years]. In order not to make a

mistake in the years, they count the minutes. At the court, in the

ministries, at the head of the administration and the army, a gang of

blokes of whom the best that can be said is that one does not know

whence they come – these noisy, disreputable, rapacious bohemians who

crawl into gallooned coats with the same grotesque dignity as the high

dignitaries of Soulouque – elbow their way forward. One can visualize

clearly this upper stratum of the Society of December 10 if one

reflects that Veron-Crevel [A dissolute philistine character in

Balzac’s novel Cousin Bette] is its preacher of morals and Granier de

Cassagnac its thinker. When Guizot, at the time of his ministry, turned

this Granier of an obscure newspaper into a dynastic opponent, he used

to boast of him with the quip: “C’est le roi des droles” [He is the

king of buffoons]. It would be wrong to recall either the Regency[124]

or Louis XV in connection with Louis Bonaparte’s court and clique. For

“often before France has experienced a government of mistresses, but

never before a government of kept men.” [Quoted from Mme. de Girardin.] Driven by the contradictory demands of his situation, and being at the same time, like a juggler, under the necessity of keeping the public gaze on himself, as Napoleon’s successor, by springing constant surprises – that is to say, under the necessity of arranging a coup d’état in miniature every day – Bonaparte throws the whole bourgeois economy into confusion, violates everything that seemed inviolable to the Revolution of 1848, makes some tolerant of revolution and makes others lust for it, and produces anarchy in the name of order, while at the same time stripping the entire state machinery of its halo, profaning it and making it at once loathsome and ridiculous. The cult of the Holy Tunic of Trier[125] [A Catholic relic, allegedly taken from Christ when he was dying, preserved in the cathedral of Marx’s native city] he duplicates in Paris in the cult of the Napoleonic imperial mantle. But when the imperial mantle finally falls on the shoulders of Louis Bonaparte, the bronze statue of Napoleon will come crashing down from the top of the Vendôme Column.[126] |

ボナパルトはあらゆる階級の父権的な恩人として見せかけたいのだ。だが

彼は一方に与えれば他方から奪わねばならない。フロンドの時代にギーズ公が「フランスで最も親切な男」と呼ばれたのは、彼が全領地を家臣に与え、彼らに封

建的義務を負わせたからである。同様にボナパルトもフランスで最も親切な男となり、フランスの全財産と全労働力を自身への人格的義務に変えたいと考えてい

る。彼はフランス全体を盗み、それをフランスへの贈り物としたい。いやむしろ、フランスのお金でフランスを新たに買い戻したいのだ。12月10日協会の首

長として、本来自分のものであるべきものを買い戻さねばならないからである。そして購入制度には、全ての国民機関、上院、国務院、議会、栄誉勲章、軍功

章、公営洗濯場、公共事業、鉄道、参謀本部、国民衛兵の将校、オルレアン家の没収領地が属している。購入の資金は、軍隊と政府機構のあらゆる地位を売り払

うことで調達される。しかし、フランスを奪い取ってフランスに与えるというこの過程で最も重要な特徴は、取引の過程で12月10日協会の首脳と構成員の懐

に入るリベートである。モルニ卿の愛人であるL伯爵夫人がオルレアン家財産没収を評した「鷲の最初の盗み(この言葉は『逃亡』と『窃盗』の両方を意味す

る)」という機知は、この鷲――むしろカラスのような存在――のあらゆる盗み行いに当てはまる。彼とその追随者たちは、まるでイタリアのカルトゥジオ会修

道士が、まだ何年も生きられる財産を誇示して数える吝嗇家を戒めるように呼び合う。「汝は財産を数えるが、まず年数を数えるべきだ」。年数を間違えないよ

う、彼らは分単位で数えるのだ。宮廷でも、省庁でも、行政や軍隊のトップでも、どこから来たのかさえ分からない連中――騒がしく、評判悪く、貪欲なボヘミ

アンどもが、ソウルークの高官たちと同じグロテスクな威厳で金縁の外套に身を包み、肘で押しのけながら出世していく。ヴェロン=クレヴェル[バルザックの

小説『ベッテのいとこ』に登場する放蕩な俗物]がその道徳の説教師であり、グラニエ・ド・カサニャックがその思想家であると考えるならば、この12月10

日派の上層階級を鮮明に想像できる。ギゾーが首相在任中、無名の新聞記者グラニエを王政反対派に育て上げた時、彼はこう自慢した。「こいつは道化師の王様

だ」と。ルイ・ボナパルトの宮廷と側近集団を評するに、摂政時代やルイ15世を連想するのは誤りだ。「フランスが愛人による統治を経験したことは幾度とな

くあったが、愛人男による統治など前代未聞だ」[ジラルダン夫人より引用]。 矛盾した状況の要求に駆られ、同時に手品師のように、ナポレオンの後継者として常に驚きを仕掛けることで公衆の視線を自分に向け続けねばならない必要性に 迫られ――つまり毎日ミニチュアのクーデターを仕掛ける必要性に迫られ ――こうしてボナパルトはブルジョワ経済全体を混乱に陥れ、1848年革命が不可侵と信じたあらゆるものを冒涜し、ある者には革命への寛容を、ある者には 革命への渇望を植え付け、秩序の名のもとに無秩序を生み出す。同時に国家機構全体から神聖な光輪を剥ぎ取り、それを冒涜し、嫌悪と嘲笑の対象へと変えるの である。トリーアの聖衣崇拝[125][マルクスの故郷の大聖堂に保存されている、キリストの臨終時に奪われたとされるカトリックの聖遺物]を、彼はパリ でナポレオン帝国のマント崇拝として再現する。しかし帝国のマントが遂にルイ・ボナパルトの肩に掛かるとき、ナポレオンの青銅像はヴァンドーム柱の頂上か ら轟音と共に崩れ落ちるだろう[126]。 |

| https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/ch07.htm |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆