事物の本性について

De rerum natura, c. 55

BC to 1473

☆『事物の本性について』(ラテン語: [deː ˈreːrʊn naːˈtuːraː])は、紀元前1世紀のローマの詩人かつ哲学者ルクレティウス(紀元前99年頃 - 紀元前55年頃)による教訓詩である。エピクロス哲学をローマの聴衆に説明することを目的としている。この詩は、約7,400行のダクティル六歩格で書か れ、6つの無題の書に分かれている。詩的な言語と比喩を通じて、エピクロス派の物理学を探求している。[1] 具体的には、原子論の原理、心と魂の本質、感覚と思考の解説、世界とその現象の発展、そして様々な天体現象や地上の現象について論じている。詩で描かれる 宇宙は、伝統的なローマ神々の神々の介入ではなく、フォルトゥーナ(「偶然」)[2]に導かれ、これらの物理的原理に従って機能している。

De rerum natura

(Latin: [deː ˈreːrʊn naːˈtuːraː]; On the Nature of Things) is a

first-century BC didactic poem by the Roman poet and philosopher

Lucretius (c. 99 BC – c. 55 BC) with the goal of explaining Epicurean

philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, written in some 7,400

dactylic hexameters, is divided into six untitled books, and explores

Epicurean physics through poetic language and metaphors.[1] Namely,

Lucretius explores the principles of atomism; the nature of the mind

and soul; explanations of sensation and thought; the development of the

world and its phenomena; and explains a variety of celestial and

terrestrial phenomena. The universe described in the poem operates

according to these physical principles, guided by fortuna

("chance"),[2] and not the divine intervention of the traditional Roman

deities. |

『事

物の本性について』(ラテン語: [deː ˈreːrʊn

naːˈtuːraː])は、紀元前1世紀のローマの詩人かつ哲学者ルクレティウス(紀元前99年頃 -

紀元前55年頃)による教訓詩である。エピクロス哲学をローマの聴衆に説明することを目的としている。この詩は、約7,400行のダクティル六歩格で書か

れ、6つの無題の書に分かれている。詩的な言語と比喩を通じて、エピクロス派の物理学を探求している。[1]

具体的には、原子論の原理、心と魂の本質、感覚と思考の解説、世界とその現象の発展、そして様々な天体現象や地上の現象について論じている。詩で描かれる

宇宙は、伝統的なローマ神々の神々の介入ではなく、フォルトゥーナ(「偶然」)[2]に導かれ、これらの物理的原理に従って機能している。 |

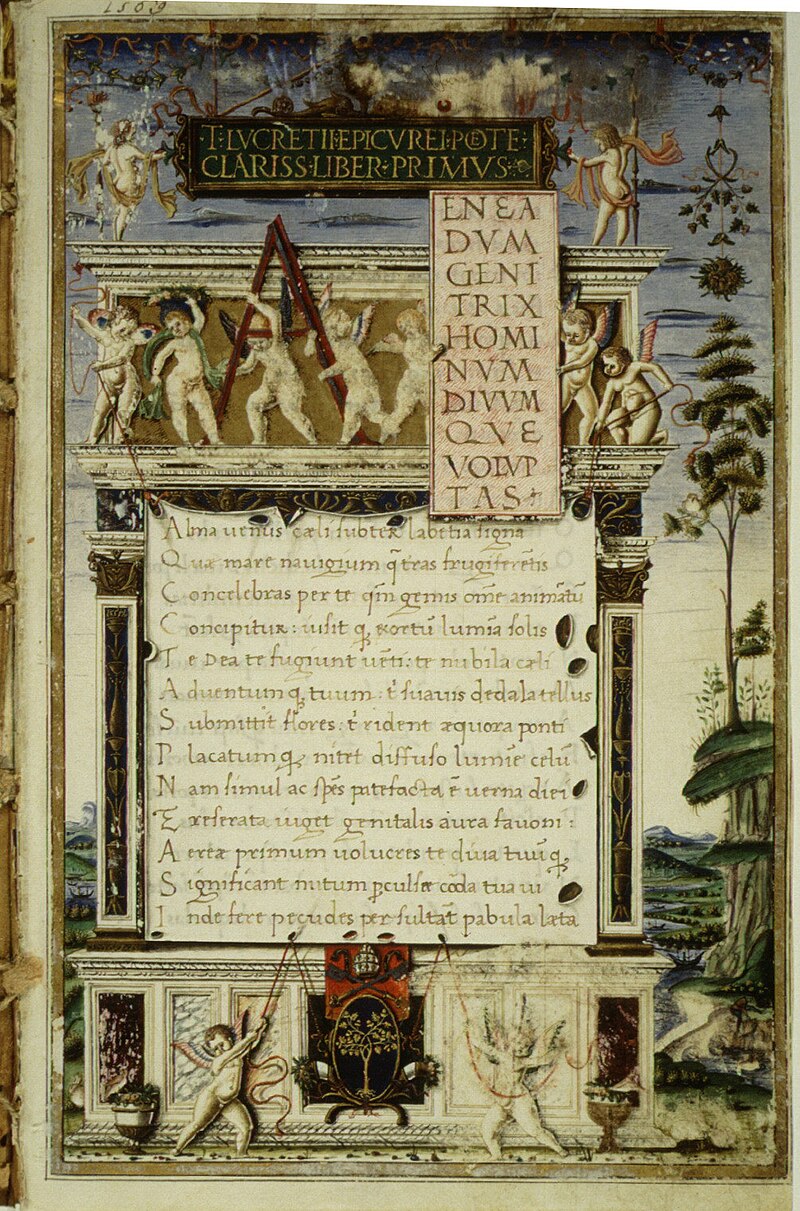

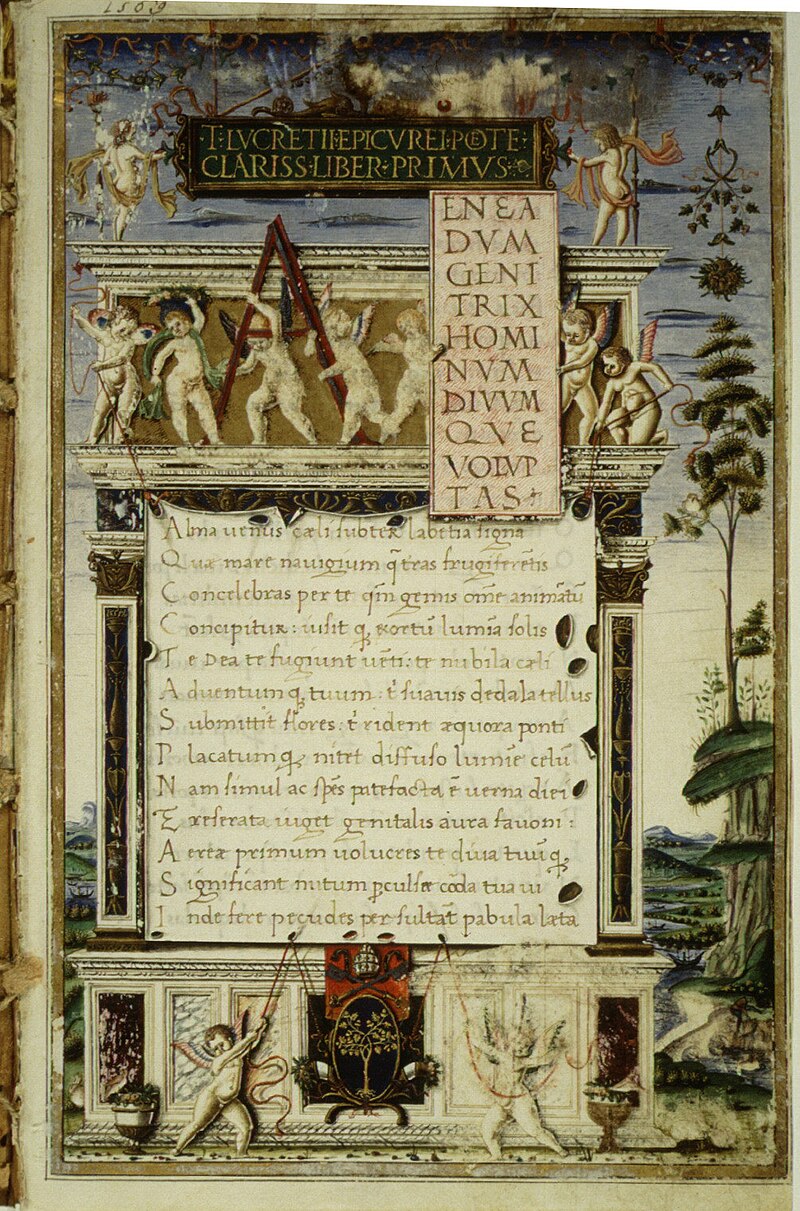

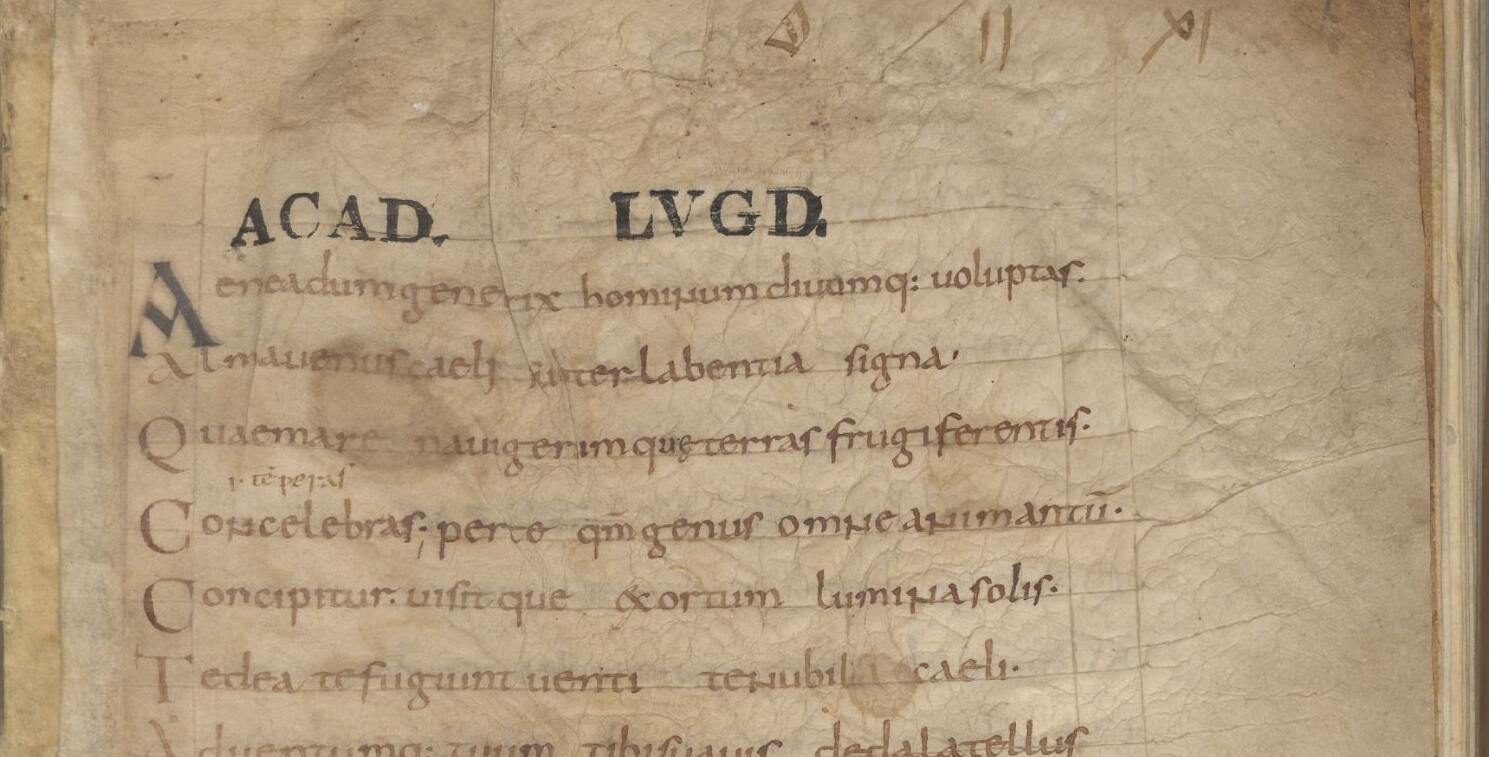

Background First lines: Aeneadum genetrix, hominum divomque voluptas. / alma Venus, caeli subter labentia signa / Quae mare navigerum, quae terras frugiferentis... (Translation: Mother of Aeneas’ tribe, delight of men and gods, nurturing Venus, who under the gliding signs of heaven [brings] fruitfulness to the ship-carrying sea and the lands..). 9th century copy, Leiden University Library. To the Greek philosopher Epicurus, the unhappiness and degradation of humans arose largely from the dread which they had of the power of the deities and terror of their wrath. This wrath was supposed to be displayed by the misfortunes inflicted in this life and by the everlasting tortures that were the lot of the guilty in a future state or, where these feelings were not strongly developed, from a vague dread of gloom and misery after death. Epicurus thus made it his mission to remove these fears and thus establish tranquility in the minds of his readers. To do this, Epicurus invoked the atomism of Democritus to demonstrate that the material universe was formed not by a Supreme Being but by the mixing of elemental particles which had existed from all eternity, governed by certain simple laws. He argued that the deities (whose existence he did not deny) lived forever in the enjoyment of absolute peace—strangers to all the passions, desires and fears, which affect humans—and are totally indifferent to the world and its inhabitants, unmoved alike by their virtues and their crimes. This meant that humans had nothing to fear from them. Lucretius's task was clearly to state and fully develop these views in an attractive form. His work was an attempt to show through poetry that everything in nature can be explained by natural laws, without the need for the intervention of divine beings.[3] Lucretius identifies the supernatural with the notion that the deities created our world or interfere with its operations in some way. He argues against fear of such deities by demonstrating, through observations and arguments, that the operations of the world can be accounted for in terms of natural phenomena, which are the result of regular but purposeless motions and interactions of tiny atoms in empty space. |

背景 冒頭行:アエネアスの母なる女神よ、人間と神々の喜び。/愛しきヴィーナスよ、天の滑る星々の下で/船乗りの海に、実り豊かな大地に… (訳:アエネアスの族の母よ、人と神々の喜びよ、育む金星よ、天の滑る星々の下で/船を運ぶ海と実り豊かな大地に豊穣をもたらす者よ…)。9世紀写本、ラ イデン大学図書館所蔵。 ギリシャの哲学者エピクロスにとって、人間の不幸と堕落は主に、神々の力への畏怖と彼らの怒りへの恐怖から生じていた。この怒りは、現世における災厄や、 来世における罪人への永遠の苦痛によって示されると考えられていた。あるいは、こうした感情が強く発達していない場合には、死後の暗黒と悲惨への漠然とし た恐怖から生じていた。エピクロスはこうした恐怖を取り除き、読者の心に平穏をもたらすことを自らの使命とした。そのために彼はデモクリトスの原子論を援 用し、物質宇宙は最高神によってではなく、永遠に存在してきた素粒子の混合によって形成され、一定の単純な法則に支配されていることを示した。彼は、神々 (その存在を否定はしなかった)は絶対的な平穏を享受しながら永遠に生きていると論じた。人間を苦しめるあらゆる情熱、欲望、恐怖とは無縁であり、世界と その住人に対して完全に無関心で、彼らの美徳にも罪にも動じない。これは人間が神々から何も恐れる必要がないことを意味した。 ルクレティウスの目的は、これらの見解を明確に述べ、魅力的な形で完全に展開することにあった。彼の著作は、詩を通して、自然界のあらゆる事象が神々の介 入を必要とせず、自然法則によって説明可能であることを示す試みであった。[3] ルクレティウスは、超自然的なものを、神々がこの世界を創造したとか、何らかの形でその営みに干渉するという考えと同一視している。彼は、観察と論証を通 じて、世界の営みは自然現象によって説明できることを示し、そうした神々への恐怖に反論する。自然現象とは、空虚な空間における微小な原子の規則的だが目 的を持たない運動と相互作用の結果に過ぎないのだ。 |

| Contents Synopsis The poem consists of six untitled books, in dactylic hexameter. The first three books provide a fundamental account of being and nothingness, matter and space, the atoms and their movement, the infinity of the universe both as regards time and space, the regularity of reproduction (no prodigies, everything in its proper habitat), the nature of mind (animus, directing thought) and spirit (anima, sentience) as material bodily entities, and their mortality, since, according to Lucretius, they and their functions (consciousness, pain) end with the bodies that contain them and with which they are interwoven. The last three books give an atomic and materialist explanation of phenomena preoccupying human reflection, such as vision and the senses, sex and reproduction, natural forces and agriculture, the heavens, and disease.  Lucretius opens his poem by addressing Venus (center), urging her to pacify her lover, Mars (right). Given Lucretius's relatively secular philosophy and his eschewing of superstition, his invocation of Venus has caused much debate among scholars. Lucretius opens his poem by addressing Venus as the mother of Rome (Aeneadum genetrix) and the mother of nature (Alma Venus), urging her to pacify her lover Mars and spare Rome from strife.[4][5] By recalling the opening to poems by Homer, Ennius, and Hesiod (all of which begin with an invocation to the Muses), the proem to De rerum natura conforms to epic convention. The entire poem is also written in the format of a hymn, recalling other early literary works, texts, and hymns and in particular the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite.[6] The choice to address Venus may have been due to Empedocles's belief that Aphrodite represents "the great creative force in the cosmos".[5] Given that Lucretius goes on to argue that the gods are removed from human life, many have thus seen this opening to be contradictory: how can Lucretius pray to Venus and then deny that the gods listen to or care about human affairs?[5] In response, many scholars argue that the poet uses Venus poetically as a metonym. For instance, Diskin Clay sees Venus as a poetic substitute for sex, and Bonnie Catto sees the invocation of the name as a metonym for the "creative process of natura".[7] After the opening, the poem commences with an enunciation of the proposition on the nature and being of the deities, which leads to an invective against the evils of superstition. Lucretius then dedicates time to exploring the axiom that nothing can be produced from nothing, and that nothing can be reduced to nothing (Nil fieri ex nihilo, in nihilum nil posse reverti). Following this, the poet argues that the universe comprises an infinite number of Atoms, which are scattered about in an infinite and vast void (Inane). The shape of these atoms, their properties, their movements, the laws under which they enter into combination and assume forms and qualities appreciable by the senses, with other preliminary matters on their nature and affections, together with a refutation of objections and opposing hypotheses, occupy the first two books.[3] In the third book, the general concepts proposed thus far are applied to demonstrate that the vital and intellectual principles, the Anima and Animus, are as much a part of us as are our limbs and members, but like those limbs and members have no distinct and independent existence, and that hence soul and body live and perish together; the book concludes by arguing that the fear of death is a folly, as death merely extinguishes all feeling—both the good and the bad.[3] The fourth book is devoted to the theory of the senses, sight, hearing, taste, smell, of sleep and of dreams, ending with a disquisition upon love and sex.[3] The fifth book is described by Ramsay as the most finished and impressive,[3] while Stahl argues that its "puerile conceptions" are proof that Lucretius should be judged as a poet, not as a scientist.[8] This book addresses the origin of the world and of all things therein, the movements of the heavenly bodies, the changing of the seasons, day and night, the rise and progress of humankind, society, political institutions, and the invention of the various arts and sciences which embellish and ennoble life.[3] The sixth book contains an explanation of some of the most striking natural appearances, especially thunder, lightning, hail, rain, snow, ice, cold, heat, wind, earthquakes, volcanoes, springs and localities noxious to animal life, which leads to a discourse upon diseases. This introduces a detailed description of the great pestilence that devastated Athens during the Peloponnesian War. With this episode, the book closes; this abrupt ending suggests that Lucretius might have died before he was able to finalize and fully edit his poem.[3] |

目次 概要 この詩は六つの無題の巻から成り、ダクティル六歩格で書かれている。最初の三巻は、存在と無、物質と空間、原子とその運動、時間と空間における宇宙の無限 性、生殖の規則性(異常は生じず、全てが適切な生息地にある)、 心(アニムス、思考を司る)と精神(アニマ、知覚)の性質を物質的・身体的実体として扱い、それらの死滅性を論じる。ルクレティウスによれば、心と精神、 そしてそれらの機能(意識、痛み)は、それらを宿し、それらと密接に絡み合う身体と共に終焉を迎えるからである。最後の三巻では、視覚や感覚、性や生殖、 自然の力や農業、天体、疾病など、人間の思索を駆り立てる現象について、原子論的かつ唯物論的な説明がなされている。  ルクレティウスは詩の冒頭で、ヴィーナス(中央)に語りかけ、彼女の恋人であるマルス(右)を鎮めるよう促している。ルクレティウスの比較的世俗的な哲学と迷信を避ける姿勢を考慮すると、彼のヴィーナスへの呼びかけは学者の間で多くの議論を引き起こしてきた。 ルクレティウスは詩の冒頭で、ヴィーナスをローマの母(Aeneadum genetrix)であり自然の母(Alma Venus)として呼びかけ、彼女の恋人であるマルスを鎮め、ローマを争いから救うよう促す。[4][5] ホメロス、エニウス、ヘシオドスの詩の冒頭(いずれもムーサへの呼びかけで始まる)を想起させることで、『物事の性質について』の序文は叙事詩の慣例に 則っている。詩全体も賛歌の形式で書かれており、他の初期文学作品、文献、賛歌、特にホメロスの『アフロディテ賛歌』を想起させる。[6] ヴィーナスに呼びかける選択は、エンペドクレスがアフロディーテを「宇宙の偉大な創造力」と見なしていた信念に起因する可能性がある。[5] ルクレティウスがその後、神々は人間の生活から隔絶されていると論じることを踏まえると、多くの研究者はこの冒頭を矛盾と見なしてきた。すなわち、ルクレ ティウスがヴィーナスに祈りながら、神々が人間の事柄に耳を傾けたり関心を持ったりしないと否定するのはどうなのか?[5] これに対し多くの学者は、詩人が金星を詩的に換喩として用いていると反論する。例えばディスキン・クレイは金星を性の詩的代用と見なし、ボニー・カトは名 前の呼びかけを「自然の創造過程」の換喩と解釈する。 [7] 冒頭の後、詩は神々の本質と存在に関する命題の表明から始まる。これが迷信の害悪に対する非難へとつながる。ルクレティウスは次に、無から有は生じず、有 は無に還り得ないという公理(Nil fieri ex nihilo, in nihilum nil posse reverti)の探求に時間を割く。 続いて詩人は、宇宙が無限の虚空(イナーン)に散らばる無数の原子で構成されていると論じる。これらの原子の形状、性質、運動、結合して感覚で捉えられる 形態や特性を獲得する法則、その他の性質や作用に関する予備的事項、そして異論や対立仮説への反駁が、最初の二巻を占める。[3] 第三巻では、これまでに提示された一般概念を応用し、生命原理と知性原理であるアニマ(Anima)とアニムス(Animus)が、四肢や器官と同様に我 々の一部でありながら、それらと同様に独立した存在を持たないことを示す。ゆえに魂と身体は共に生じ、共に滅びる。本書は、死が単に全ての感覚——善悪を 問わず——を消滅させるに過ぎないため、死への恐怖は愚かであると論じて結ぶ。[3] 第四巻は感覚論、視覚・聴覚・味覚・嗅覚、睡眠と夢の理論に捧げられ、愛と性に関する考察をもって終わる。[3] 第五巻はラムゼイによって最も完成度が高く印象的と評される一方[3]、シュタールは「幼稚な概念」がルクレティウスを科学者ではなく詩人として評価すべ き証拠だと主張する。[8] この巻では世界の起源と万物の成り立ち、天体の運動、季節の移り変わり、昼と夜、人類の発生と発展、社会、政治制度、そして生活を彩り高める様々な芸術や 科学の発明について論じている。[3] 第六巻では、雷鳴、稲妻、雹、雨、雪、氷、寒冷、高温、風、地震、火山、泉、そして動物の生命に有害な地域など、最も印象的な自然現象のいくつかについて 説明している。これは病気に関する論考へと繋がり、ペロポネソス戦争中にアテネを荒廃させた大疫病の詳細な記述へと導く。このエピソードをもって本書は終 わる。この唐突な結末は、ルクレティウスが詩を完成させ完全に編集する前に亡くなった可能性を示唆している。[3] |

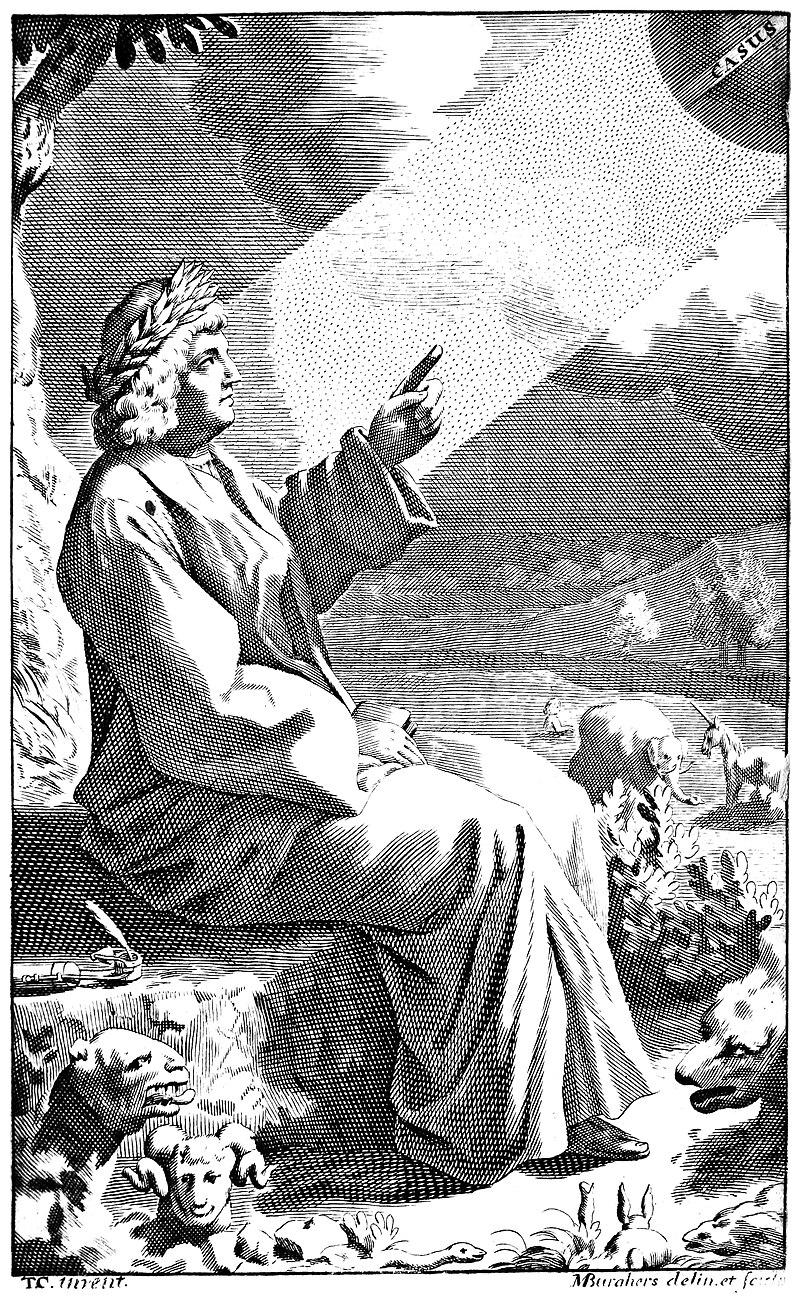

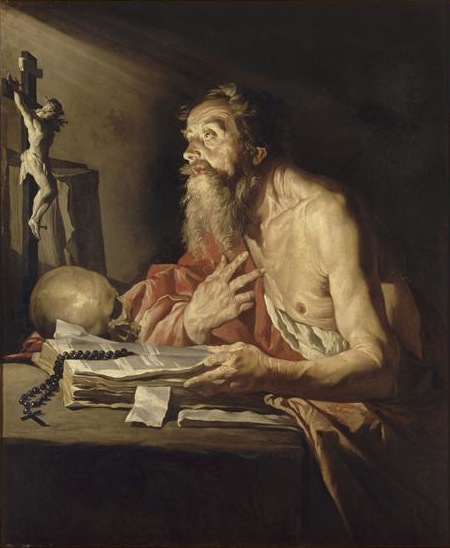

Purpose Fictional portrait of the Roman scholar and poet Lucretius, author of De rerum natura Lucretius wrote this epic poem to "Memmius", who may be Gaius Memmius, who in 58 BC was a praetor, a judicial official deciding controversies between citizens and the government.[9] There are over a dozen references to "Memmius" scattered throughout the long poem in a variety of contexts in translation, such as "Memmius mine", "my Memmius", and "illustrious Memmius". According to Lucretius's frequent statements in his poem, the main purpose of the work was to free Gaius Memmius's mind of the supernatural and the fear of death—and to induct him into a state of ataraxia by expounding the philosophical system of Epicurus, whom Lucretius glorifies as the hero of his epic poem. However, the purpose of the poem is subject to ongoing scholarly debate. Lucretius refers to Memmius by name four times in the first book, three times in the second, five in the fifth, and not at all in the third, fourth, or sixth books. In relation to this discrepancy in the frequency of Lucretius's reference to the apparent subject of his poem, Kannengiesser advances the theory that Lucretius wrote the first version of De rerum natura for the reader at large, and subsequently revised in order to write it for Memmius. However, Memmius' name is central to several critical verses in the poem, and this theory has therefore been largely discredited.[10] The German classicists Ivo Bruns and Samuel Brandt set forth an alternative theory that Lucretius did at first write the poem with Memmius in mind, but that his enthusiasm for his patron cooled over time.[11][12] Stearns suggests that this is because Memmius reneged on a promise to pay for a new school to be built on the site of the old Epicurean school.[13] Memmius was also a tribune in 66, praetor in 58, governor of Bithynia in 57, and was a candidate for the consulship in 54 but was disqualified for bribery, and Stearns suggests that the warm relationship between patron and client may have cooled (sed tua me virtus tamen et sperata voluptas / suavis amicitiae quemvis efferre laborem, "But still your merit, and as I hope, the joy / Of our sweet friendship, urge me to any toil").[13][14] There is a certain irony to the poem, namely that while Lucretius extols the virtue of the Epicurean school of thought, Epicurus himself had advised his acolytes from penning poetry because he believed it to make that which was simple overly complicated.[15] Near the end of his first book, Lucretius defends his fusion of Epicureanism and poetry with a simile, arguing that the philosophy he espouses is like a medicine: life-saving but often unpleasant. Poetry, on the other hand, is like honey, in that it is "a sweetener that sugarcoats the bitter medicine of Epicurean philosophy and entices the audience to swallow it."[16][17] (Of note, Lucretius repeats these 25 lines, almost verbatim, in the introduction to the fourth book.)[18] Completeness The state of the poem as it currently exists suggests that it was released in an unfinished state.[19] For instance, the poem concludes rather abruptly while detailing the Plague of Athens, there are redundant passages throughout (e.g., 1.820–821 and 2.1015–1016) alongside other aesthetic "loose ends", and at 5.155 Lucretius mentions that he will spend a great deal of time discussing the nature of the gods, which never comes to pass.[3][20][21] Some have suggested that Lucretius died before being able to edit, finalize, and publish his work.[22] |

目的 ローマの学者であり詩人であるルクレティウスの架空の肖像。彼は『物事の性質について』の著者である。 ルクレティウスはこの叙事詩を「メンミウス」に捧げた。この人物はおそらくガイウス・メンミウスであり、紀元前58年に執政官を務め、市民と政府間の紛争 を裁く司法官であった。[9] この長詩には「わがメミウス」「私のメミウス」「高名なるメミウス」など、様々な文脈で「メミウス」への言及が十数箇所散見される。ルクレティウスが詩中 で繰り返し述べているように、この作品の主目的はガイウス・メンミウスの精神を超自然的なものや死への恐怖から解放し、エピクロス哲学の体系を解説するこ とで彼をアタラクシア(平静)の状態へと導くことにある。ルクレティウスはエピクロスを叙事詩の英雄として称賛している。 しかし、この詩の目的については学者の間で議論が続いている。ルクレティウスは第一巻で四回、第二巻で三回、第五巻で五回、メミウスの名を直接言及してい るが、第三、第四、第六巻では一度も言及していない。この、詩の主題と思われる人物への言及頻度の不一致に関連して、カンネンギッサーは、ルクレティウス が『物事の性質について』の初稿を一般読者を対象に執筆し、その後メミウス向けに改訂したとする説を提唱した。しかし、メミウスの名は詩中のいくつかの重 要な詩句の中心にあるため、この説はほぼ否定されている。[10] ドイツの古典学者イヴォ・ブルンスとサミュエル・ブラントは、ルクレティウスが当初はメミウスを念頭に詩を執筆したが、時間の経過とともに後援者への熱意 が冷めたとする代替説を提唱している。[11][12] スティアーンズは、この冷淡さの原因として、メミウスが旧エピクロス学派の校舎跡地に新校舎を建設する資金提供の約束を反故にしたことを挙げている。 [13] メミウスは紀元前66年に護民官、58年に法務官、57年にビテュニア総督を務め、54年には執政官候補となったが収賄で失格となった。スターンズによれ ば、後援者と被後援者の温かい関係は冷え込んだ可能性がある(sed tua me virtus tamen et sperata voluptas / suavis amicitiae quemvis efferre laborem, 「だがそれでもお前の功績と、望みどおりの喜び/我らの甘い友情が、どんな労苦も厭わぬように駆り立てる」)。[13][14] この詩にはある種の皮肉がある。すなわちルクレティウスがエピクロス学派の思想の美徳を称賛する一方で、エピクロス自身は詩作が単純なものを過度に複雑に すると考えて、弟子たちに詩を書くことを禁じていたのだ。[15] 第一巻の終わり近くで、ルクレティウスは比喩を用いてエピクロス思想と詩の融合を擁護する。彼が提唱する哲学は薬のようなものだと主張するのだ。命を救う が、しばしば不快である。一方、詩は蜂蜜のようなものだ。それは「エピクロス哲学という苦い薬を甘く包み込み、聴衆に飲み込ませる誘い」だからである。 [16][17] (特筆すべきは、ルクレティウスが第四巻の序文で、この25行をほぼそのまま繰り返している点である。)[18] 完全性 現在の詩の状態は、未完成の状態で発表されたことを示唆している。[19] 例えば、アテネの疫病を詳述する途中で詩は突然終わる。また、冗長な箇所(例:1.820–821、2.1015–1016)やその他の美学的「未解決部 分」が随所に見られる。さらに5.155では、ルクレティウスが神々の本質について長々と論じると述べているが、それは実現しなかった。[3][20] [21] ルクレティウスは作品を編集・完成・出版する前に死去したのではないかという見解もある。[22] |

| Main ideas Metaphysics Lack of divine intervention  Lucretius pointing to the casus, the downward movement of the atoms. From the frontispiece to Of the Nature of Things, 1682. After the poem was rediscovered and made its rounds across Europe and beyond, numerous thinkers began to see Lucretius's Epicureanism as a "threat synonymous with atheism."[23] Some Christian apologists viewed De rerum natura as an atheist manifesto and a dangerous foil to be thwarted.[23] However, at that time the label was extremely broad and did not necessarily mean a denial of divine entities (for example, some large Christian sects labelled dissenting groups as atheists).[24] What is more, Lucretius does not deny the existence of deities;[25][26] he simply argues that they did not create the universe, that they do not care about human affairs, and that they do not intervene in the world.[23] Regardless, due to the ideas espoused in the poem, much of Lucretius's work was seen by many as a direct challenge to theistic, Christian belief.[27] The historian Ada Palmer has labelled six ideas in Lucretius's thought (viz. his assertion that the world was created from chaos, and his denials of Providence, divine participation, miracles, the efficacy of prayer, and an afterlife) as "proto-atheistic".[28][29] She qualifies her use of this term, cautioning that it is not to be used to say that Lucretius was himself an atheist in the modern sense of the word, nor that atheism is a teleological necessity, but rather that many of his ideas were taken up by 19th-, 20th-, and 21st-century atheists.[29] Repudiation of immortality De rerum natura does not argue that the soul does not exist; rather, the poem claims that the soul, like all things in existence, is made up of atoms, and because these atoms will one day drift apart, the human soul is not immortal. Lucretius thus argues that death is simply annihilation, and that there is no afterlife. He likens the physical body to a vessel that holds both the mind (mens) and spirit (anima). To prove that neither the mind nor spirit can survive independent of the body, Lucretius uses a simple analogy: when a vessel shatters, its contents spill everywhere; likewise, when the body dies, the mind and spirit dissipate. And as a simple ceasing-to-be, death can be neither good nor bad for this being, since a dead person—being completely devoid of sensation and thought—cannot miss being alive.[5] To further alleviate the fear of non-existence, Lucretius makes use of the symmetry argument: he argues that the eternal oblivion awaiting all humans after death is exactly the same as the infinite nothingness that preceded our birth. Since that nothingness (which he likens to a deep, peaceful sleep) caused us no pain or discomfort, we should not fear the same nothingness that will follow our own demise:[5] Look back again—how the endless ages of time comes to pass Before our birth are nothing to us. This is a looking glass Nature holds up for us in which we see the time to come After we finally die. What is there that looks so fearsome? What's so tragic? Isn't it more peaceful than any sleep?[30] According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Lucretius sees those who fear death as embracing the fallacious assumption that they will be present in some sense "to regret and bewail [their] own non-existence."[5] Physics Lucretius maintained that he could free humankind from fear of the deities by demonstrating that all things occur by natural causes without any intervention by the deities. Historians of science, however, have been critical of the limitations of his Epicurean approach to science, especially as it pertained to astronomical topics, which he relegated to the class of "unclear" objects.[31][32] Thus, he began his discussion by claiming that he would explain by what forces nature steers the courses of the Sun and the journeyings of the Moon, so that we shall not suppose that they run their yearly races between heaven and earth of their own free will [i.e., are gods themselves] or that they are rolled round in furtherance of some divine plan....[33] However, when he set out to put this plan into practice, he limited himself to showing how one, or several different, naturalistic accounts could explain certain natural phenomena. He was unable to tell his readers how to determine which of these alternatives might be the true one.[34] For instance, when considering the reason for stellar movements, Lucretius provides two possible explanations: that the sky itself rotates, or that the sky as a whole is stationary while constellations move. If the latter is true, Lucretius, notes, this is because: "either swift currents of ether whirl round and round and roll their fires at large across the nocturnal regions of the sky"; "an external current of air from some other quarter may whirl them along in their course"; or "they may swim of their own accord, each responsive to the call of its own food, and feed their fiery bodies in the broad pastures of the sky". Lucretius concludes that "one of these causes must certainly operate in our world... But to lay down which of them it is lies beyond the range of our stumbling progress."[35] Despite his advocacy of empiricism and his many correct conjectures about atomism and the nature of the physical world, Lucretius concludes his first book stressing the absurdity of the (by then well-established) spherical Earth theory, favoring instead a flat Earth cosmology.[36] Drawing on these, and other passages, William Stahl considered that "The anomalous and derivative character of the scientific portions of Lucretius' poem makes it reasonable to conclude that his significance should be judged as a poet, not as a scientist."[37] His naturalistic explanations were meant to bolster the ethical and philosophical ideas of Epicureanism, not to reveal true explanations of the physical world.[36] The swerve Main article: Clinamen Determinism appears to conflict with the concept of free will. Lucretius attempts to allow for free will in his physicalistic universe by postulating an indeterministic tendency for atoms to veer randomly (Latin: clinamen, literally "the turning aside of a thing", but often translated as "the swerve").[1][38] According to Lucretius, this unpredictable swerve occurs at no fixed place or time: When atoms move straight down through the void by their own weight, they deflect a bit in space at a quite uncertain time and in uncertain places, just enough that you could say that their motion has changed. But if they were not in the habit of swerving, they would all fall straight down through the depths of the void, like drops of rain, and no collision would occur, nor would any blow be produced among the atoms. In that case, nature would never have produced anything.[39][40] This swerving provides the indeterminacy that Lucretius argues allows for the "free will which living things throughout the world have" (libera per terras ... haec animantibus exstat ... voluntas).[41] |

主な思想 形而上学 神の介入の欠如  ルクレティウスが原子の下方運動(カサス)を指し示す場面。『物事の性質について』の扉絵より、1682年。 この詩が再発見されヨーロッパ内外に広まると、多くの思想家がルクレティウスのエピクロス主義を「無神論と同義の脅威」と見なすようになった[23]。一 部のキリスト教擁護論者は『物性論』を無神論宣言書と見なし、阻止すべき危険な対抗勢力とみなした[23]。ただし当時の「無神論」というレッテルは極め て広範で、必ずしも神的存在の否定を意味しなかった(例えば、キリスト教の主要宗派が異端集団を無神論者とレッテル貼りする事例があった)。[24] さらに言えば、ルクレティウスは神々の存在を否定していない[25][26]。単に、神々が宇宙を創造したわけではなく、人間界に関心を寄せず、世界へ介 入しないことを論じているに過ぎない[23]。とはいえ、この詩に込められた思想ゆえに、ルクレティウスの著作の多くは、有神論的キリスト教信仰への直接 的な挑戦と見なされた。[27] 歴史家エイダ・パーマーは、ルクレティウスの思想における六つの主張(すなわち、世界が混沌から創造されたという主張、摂理・神の介入・奇跡・祈りの効 力・来世の存在の否定)を「原始的無神論」と呼んだ。[28][29] 彼女はこの用語の使用に条件を付け、ルクレティウス自身が現代的な意味での無神論者だったとか、無神論が目的論的な必然性を持つとか言うためのものではな いと注意を促している。むしろ、彼の思想の多くが19世紀、20世紀、21世紀の無神論者たちに受け継がれたという意味だ。[29] 不死性の否定 『物事の性質について』は魂が存在しないとは主張しない。むしろ、魂も存在する全てのものと同様に原子で構成されており、これらの原子はいつか離散するた め、人間の魂は不死ではないと論じる。ルクレティウスはこうして、死は単なる消滅であり、来世は存在しないと主張する。彼は肉体という器に心(mens) と精神(anima)が宿ると例える。心も精神も身体から独立して存続できないことを証明するため、ルクレティウスは単純な比喩を用いる。器が砕け散れば 中身はあちこちに散らばるように、身体が死ねば心と精神は消え去るのだ。そして単なる存在の消滅である死は、この存在にとって良くも悪くもない。なぜなら 死者は感覚も思考も完全に失っているため、生きていることを惜しむこともできないからだ。[5] 非存在への恐怖をさらに和らげるため、ルクレティウスは対称性の論証を用いる。死後に全人類を待つ永遠の忘却は、我々の誕生以前に存在した無限の無と全く 同じだと主張するのだ。その無(深い安らかな眠りに例えられる)が我々に苦痛や不快感をもたらさなかった以上、自らの死後に訪れる同じ無を恐れるべきでは ない: [5] 振り返ってみよ——果てしなき時の歳月が過ぎ去る様を 我らが生まれる前の時など、我らにとって何の意味もない。これは自然が我らに差し出す鏡だ 我らが遂に死んだ後の時を見るために そこには何がそんなに恐ろしいのか? 何がそんなに悲劇なのか?どんな眠りよりも安らかではないか?[30] スタンフォード哲学百科事典によれば、ルクレティウスは死を恐れる者たちが「自らの非存在を嘆き悲しむ」ために何らかの形で存在し続けるという誤った前提を抱いていると見なしている。[5] 物理学 ルクレティウスは、万物が神々の介入なしに自然原因によって生じることを示すことで、人類を神々への恐怖から解放できると主張した。しかし科学史家たち は、特に天文学的課題に関して彼が「不明確」な対象の範疇に追いやった点など、彼のエピクロス派的科学アプローチの限界を批判してきた。[31] [32] そこで彼は議論の冒頭で、次のように宣言した。 自然がどのような力で太陽の軌道と月の運行を導いているかを説明しよう。そうすれば我々は、それらが天と地の間を自らの意思で(すなわち神々自身として) 年ごとの軌道を走るのだとか、何らかの神聖な計画に従って転がされているのだとか、そんなことを思い込むことはなくなるだろう……[33] しかしこの計画を実行に移す際、彼は特定の自然現象を説明しうる自然主義的解釈が一つか複数存在することを示すに留まった。どの解釈が真実かを判断する方 法を読者に示すことはできなかった[34]。例えば星の動きの理由を考察する際、ルクレティウスは二つの可能性を提示する:天空自体が回転している説、あ るいは天空全体が静止し星座が移動する説である。後者が真実だとすれば、ルクレティウスはこう記す:「エーテルの速い流れが渦巻き、夜空の広大な領域を火 を転がしながら巡っているから」あるいは「他の場所からの外部の気流が、それらをその軌道に沿って巻き上げているから」あるいは「それらは自らの意思で泳 ぎ、それぞれの食物の呼び声に応え、空の広大な牧草地で火の体を養っているから」である。ルクレティウスは「これらの原因のいずれかが確かに我々の世界で 作用しているに違いない…しかし、それがどれであるかを断定することは、我々のつまずきながらの進歩の範囲を超えている」と結論づける[35]。 経験主義を提唱し、原子論や物理世界の性質について多くの正しい推測を示したにもかかわらず、ルクレティウスは第一巻の結びで(当時すでに確立されていた)球体地球説の非合理性を強調し、代わりに平坦な地球宇宙論を支持している。[36] これらの箇所や他の記述に基づき、ウィリアム・スタールは「ルクレティウスの詩における科学的記述の特異性と派生的な性質から、彼の意義は科学者ではなく 詩人として評価されるべきだと結論づけるのが妥当である」と考えた[37]。彼の自然主義的説明は、物理世界の真の説明を明らかにするためではなく、エピ クロス主義の倫理的・哲学的観念を補強することを意図していた。[36] 偏向(クリナメン) 詳細記事: クリナメン 決定論は自由意志の概念と矛盾するように見える。ルクレティウスは、原子に不確定な傾向、すなわちランダムに方向を変える傾向(ラテン語: clinamen、文字通り「物事がそれること」を意味するが、しばしば「偏向」と訳される)を仮定することで、物理主義的な宇宙において自由意志を許容 しようと試みた。[1][38] ルクレティウスによれば、この予測不可能な逸脱は特定の場所や時間では起こらない: 原子が自らの重みで虚空を真っ直ぐに落下する時、空間の中で不確かな時間と不確かな場所でわずかに方向を変える。その変化は、原子の運動が変化したと言え る程度のものだ。しかしもし彼らが逸脱する習性を持たなければ、雨粒のように虚空の深淵へ真っ直ぐ落下し、衝突も生じず、原子間の衝撃も発生しない。そう なれば自然は何一つ生み出せなかっただろう。[39] [40] この逸脱こそが、ルクレティウスが「世界中の生き物が持つ自由意志」(libera per terras ... haec animantibus exstat ... voluntas)を可能にする不確定性を生み出すと論じる根拠である。[41] |

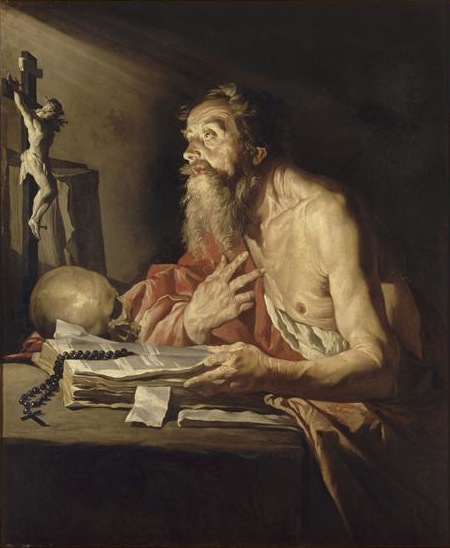

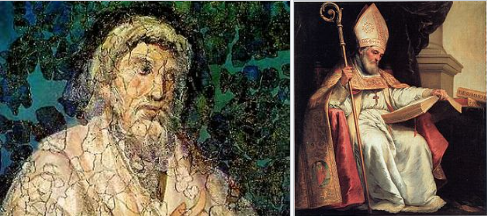

| Textual history Classical antiquity to the Middle Ages  St. Jerome contended in his Chronicon that Cicero amended and edited De rerum natura. This assertion has been hotly debated, with most scholars thinking it was a mistake on Jerome's part. Martin Ferguson Smith notes that Cicero's close friend, Titus Pomponius Atticus, was an Epicurean publisher, and it is possible his slaves made the very first copies of De rerum natura.[42] If this were the case, then it might explain how Cicero came to be familiar with Lucretius's work.[43] In c. AD 380, St. Jerome would contend in his Chronicon that Cicero amended and edited De rerum natura,[44] although most scholars argue that this is an erroneous claim;[45] the classicist David Butterfield argues that this mistake was likely made by Jerome (or his sources) because the earliest reference to Lucretius is in the aforementioned letter from Cicero.[45] Nevertheless, a small minority of scholars argue that Jerome's assertion may be credible.[5] The oldest purported fragments of De rerum natura were published by K. Kleve in 1989 and consist of sixteen fragments. These remnants were discovered among the Epicurean library in the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum. Because, as W. H. D. Rouse notes, "the fragments are so minute and bear so few certainly identifiable letters", at this point in time "some scepticism about their proposed authorship seems pardonable and prudent."[46] However, Kleve contends that four of the six books are represented in the fragments, which he argues is reason to assume that the entire poem was at one time kept in the library. If Lucretius's poem were to be definitely placed at the Villa of the Papyri, it would suggest that it was studied by the Neapolitan Epicurean school.[46] Copies of the poem were preserved in a number of medieval libraries, with the earliest extant manuscripts dating to the ninth century.[47] The oldest—and, according to David Butterfield, most famous—of these is the Codex Oblongus, often called O. This copy has been dated to the early ninth century and was produced by a Carolingian scriptorium (likely a monastery connected to the court of Charlemagne).[48] O is currently housed at Leiden University Libraries as MS VLF 30.[49] The second of these ninth-century manuscripts is the Codex Quadratus, often called Q. This manuscript was likely copied after O, sometime in the mid-ninth century.[50] Today, Q is also housed at Leiden University Libraries as VLQ 94.[51] The third and final ninth-century manuscript—which comprises the Schedae Gottorpienses fragment (commonly called G and located in the Kongelige Bibliotek of Copenhagen) and the Schedae Vindobonenses fragments (commonly called V and U and located in the Austrian National Library in Vienna)—was christened by Butterfield as S and has been dated to the latter part of the ninth century.[52][53] Scholars consider manuscripts O, Q, and S to all be descendants of the original archetype, which they dub Ω.[54] However, while O is a direct descendant of the archetype,[54] Q and S are believed to have both been derived from a manuscript (Ψ) that in turn had been derived from a damaged and modified version of the archetype (ΩI).[55][56] |

テキストの歴史 古代から中世まで  聖ヒエロニムスは、彼の『年代記』の中で、キケロが『物事の性質について』を修正し編集したと主張した。この主張は熱く議論されており、ほとんどの学者は、これはヒエロニムスの誤りであると考えられている。 マーティン・ファーガソン・スミスは、キケロの親友であるティトゥス・ポンポニウス・アッティクスがエピクロス派の出版者であり、彼の奴隷たちが『物事の 性質について』の最初の写本を作成した可能性があると指摘している[42]。もしそうであれば、キケロがルクレティウスの著作に精通していた理由を説明で きるかもしれない。[43] 紀元 380 年頃、聖ジェロームは『年代記』の中で、キケロが『物事の性質について』を修正・編集したと主張している[44]が、ほとんどの学者はこれは誤った主張だ と論じている[45]。古典学者デビッド・バターフィールドは、ルクレティウスに関する最古の言及は前述のキケロの手紙にあるため、この誤りはジェローム (またはその情報源)によるものだろうと論じている。[45] とはいえ、ごく少数の学者はヒエロニムスの主張に信憑性がある可能性を主張している[5]。 『物事の性質について』の最古とされる断片は1989年にK.クレーヴェによって発表され、16の断片から成る。これらの残骸は、ヘルクラネウムのパピル スの別荘にあるエピクロス派図書館で発見された。W・H・D・ラウズが指摘するように「断片は極めて微細で、確実に識別可能な文字が極めて少ない」ため、 現時点では「その帰属に関する懐疑的見解は許容され、慎重と言える」のである。[46] しかしクレーヴェは、6巻のうち4巻が断片に現れていると主張し、これが全詩がかつて図書館に所蔵されていたと推測する根拠だと論じている。ルクレティウ スの詩がパピルスの別荘に確実に存在したとすれば、それはナポリのエピクロス学派によって研究されていたことを示唆する。[46] この詩の写本は中世の複数の図書館に保存され、現存する最古の写本は9世紀にさかのぼる。[47] これらの中で最古(そしてデイヴィッド・バターフィールドによれば最も著名)なものは、しばしばOと呼ばれる長方形写本(Codex Oblongus)である。この写本は9世紀初頭に作成され、カロリング朝の写字室(おそらくカール大帝の宮廷と関係のある修道院)で制作された。 [48] O写本は現在ライデン大学図書館にMS VLF 30として所蔵されている。[49] 9世紀写本のうち二つ目は四角形写本(Codex Quadratus)で、しばしばQと呼ばれる。この写本は9世紀中頃にO写本を模写したものと見られる。[50] 現在Q写本もライデン大学図書館にVLQ 94として所蔵されている。[51] 第三かつ最後の9世紀写本群——シェダー・ゴットルピエンセス断片(通称G、コペンハーゲンの王立図書館所蔵)とシェダー・ヴィンドボネンセス断片(通称 V及びU、ウィーンのオーストリア国立図書館所蔵)——はバターフィールドによりSと命名され、9世紀後半の作と推定されている。[52] [53] 学者らは写本O、Q、Sを全て原典Ωの派生写本と見なしている。[54] ただしOは原典の直接の子孫である一方、[54] QとSは共に写本Ψに由来すると考えられており、このΨは損傷・改変された原典ΩIから派生したものである。[55][56] |

Rediscovery to the present Engraving of Poggio Bracciolini in middle age De rerum natura was rediscovered by Poggio Bracciolini c. 1416–1417. While there exist a handful of references to Lucretius in European sources dating between the ninth and fifteenth centuries (references that, according to Ada Palmer, "indicate a tenacious, if spotty knowledge of the poet and some knowledge of [his] poem"), no manuscripts of De rerum natura are known to survive from this span of time.[57] Rather, all the remaining Lucretian manuscripts, apart from the early three discussed above, that are known date from or after the fifteenth century.[58] This is because De rerum natura was rediscovered in January 1417 by Poggio Bracciolini, who probably found the poem in the Benedictine library at Fulda. The manuscript that Poggio discovered did not survive, but a copy (the "Codex Laurentianus 35.30") of it by Poggio's friend, Niccolò de' Niccoli, did, and today it is kept at the Laurentian Library in Florence.[1] Machiavelli made a copy early in his life. Molière produced a verse translation which does not survive; John Evelyn translated the first book.[1] The Italian scholar Guido Billanovich demonstrated that Lucretius' poem was well known in its entirety by Lovato Lovati (1241–1309) and some other Paduan pre-humanists during the thirteenth century.[59][60] This proves that the work was known in select circles long before the official rediscovery by Bracciolini. It has been suggested that Dante (1265–1321) might have read Lucretius's poem, as a few verses of his Divine Comedy exhibit a great affinity with De rerum natura, but there is no conclusive evidence for this hypothesis.[59] The first printed edition of De rerum natura was produced in Brescia, Lombardy, in 1473.[61] Other printed editions followed soon after. Additionally, although only published in 1996, Lucy Hutchinson's translation of De rerum natura was in all likelihood the first in English and was most likely completed some time in the late 1640s or 1650s, though it remained unpublished in manuscript.[62] |

現代に至る再発見 中世のポッジョ・ブラッチョリーニの版画 『物事の性質について』は、ポッジョ・ブラッチョリーニによって1416年から1417年頃に再発見された。 9世紀から15世紀にかけてのヨーロッパ文献にはルクレティウスへの言及がいくつか存在する(エイダ・パーマーによれば、これらは「断片的ではあるが詩人 への確固たる知識と、その詩作への一定の理解を示している」)。しかしこの期間に『物事の性質について』の写本が現存している例は知られていない。 [57] むしろ、前述の初期の三点を除き、現存するルクレティウスの写本はすべて15世紀以降のものだ。[58] これは『物事の性質について』が1417年1月にポッジョ・ブラッチョリーニによって再発見されたためである。彼はおそらくフルダのベネディクト会図書館 でこの詩を発見した。ポッジョが発見した写本は現存しないが、彼の友人ニッコロ・デ・ニッコーリによる写本(「ラウレンツィアーナ図書館35.30」)は 現存し、現在フィレンツェのラウレンツィアーナ図書館に所蔵されている。[1] マキャヴェッリは若き日に写本を作成した。モリエールは韻文訳を作成したが現存せず、ジョン・エヴリンは第一巻を翻訳した。[1] イタリアの学者グイド・ビラノヴィッチは、ルクレティウスの詩が13世紀にロヴァート・ロヴァティ(1241–1309)や他のパドヴァの先駆的人文主義 者たちによって完全に知られていたことを証明した。[59][60]これは、ブラッチョリーニによる公式な再発見よりずっと前から、この作品が特定の知識 人層で知られていたことを示している。ダンテ(1265–1321)がルクレティウスの詩を読んだ可能性が示唆されている。彼の『神曲』の数節が『物事の 性質について』と強い親和性を示すためである。しかしこの仮説を裏付ける決定的な証拠は存在しない。[59] 『物事の性質について』の初版印刷物は1473年、ロンバルディアのブレシアで制作された。[61] その後、他の印刷版が相次いで出版された。また、ルーシー・ハッチンソンの『物性論』英訳は1996年にようやく出版されたものの、おそらく英語初の翻訳 であり、1640年代後半か1650年代に完成した可能性が高い。ただし、原稿のまま未発表のままだった。[62] |

| Reception Classical antiquity Bust of Cicero Many scholars believe that Lucretius and his poem were referenced or alluded to by Cicero. The earliest recorded critique of Lucretius's work is in a letter written by the Roman statesman Cicero to his brother Quintus, in which the former claims that Lucretius's poetry is "full of inspired brilliance, but also of great artistry" (Lucreti poemata, ut scribis, ita sunt, multis luminibus ingeni, multae tamen artis).[63][64] It is also believed that G. Julius Caesar alludes to Lucretius' work variously in his Gallic Wars,[65] just as the Roman poet Virgil referenced Lucretius and his work in the second book of his Georgics when he wrote: "Happy is he who has discovered the causes of things and has cast beneath his feet all fears, unavoidable fate, and the din of the devouring Underworld" (felix qui potuit rerum cognoscere causas/atque metus omnis et inexorabile fatum/subiecit pedibus strepitumque Acherontis avari).[5][66][67] According to David Sedley of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "With these admiring words, Virgil neatly encapsulates four dominant themes of the poem—universal causal explanation, leading to elimination of the threats the world seems to pose, a vindication of free will, and disproof of the soul's survival after death."[5] Lucretius was almost certainly read by the imperial poet Marcus Manilius (fl. 1st century AD), whose didactic poem Astronomica (written c. AD 10–20) alludes to De rerum natura in a number of places.[68] However, Manilius's poem espouses a Stoic, deterministic understanding of the universe,[69] and by its very nature attacks the very philosophical underpinnings of Lucretius's worldview.[68] This has led scholars like Katharina Volk to argue that "Manilius is a veritable anti-Lucretius".[68] What is more, Manilius also seems to suggest throughout this poem that his work is superior to that of Lucretius's.[70] (Coincidentally, De rerum natura and the Astronomica were both rediscovered by Poggio Bracciolini in the early 15th century.)[71] Additionally, Lucretius's work is discussed by the Augustan poet Ovid, who in his Amores writes "the verses of the sublime Lucretius will perish only when a day will bring the end of the world" (Carmina sublimis tunc sunt peritura Lucreti / exitio terras cum dabit una dies),[72] and the Silver Age poet Statius, who in his Silvae praises Lucretius as being highly "learned".[73][74] David Butterfield also writes that "clear echoes and/or responses" to De rerum natura can be detected in the works of the Roman elegiac poets Catullus, Propertius, and Tibullus, as well as the lyric poet Horace.[75] In regards to prose writers, a number either quote from Lucretius's poem or express great admiration for De rerum natura, including Vitruvius (in De Architectura),[76][77] Marcus Velleius Paterculus (in the Historiae Romanae),[77][78] Quintilian (in the Institutio Oratoria),[73][79] Tacitus (in the Dialogus de oratoribus),[73][80] Marcus Cornelius Fronto (in De eloquentia),[81][82] Cornelius Nepos (in the Life of Atticus),[77][83] Apuleius (in De Deo Socratis),[84][85] and Gaius Julius Hyginus (in the Fabulae).[86][87] Additionally, Pliny the Elder lists Lucretius (presumably referring to his De rerum natura) as a source at the beginning of his Naturalis Historia, and Seneca the Younger quoted six passages from De rerum natura across several of his works.[88][89] |

レセプション 古典古代 キケロの胸像 多くの学者は、ルクレティウスとその詩がキケロによって言及または暗示されたと考えている。 ルクレティウスの作品に対する最古の記録された批評は、ローマの政治家キケロが弟クィントゥスに宛てた書簡にある。その中でキケロは、ルクレティウスの詩 は「霊感に満ちた輝きに満ちているが、同時に高度な芸術性をも備えている」と述べている(Lucreti poemata, ut scribis, ita sunt, multis luminibus ingeni, multae tamen artis)。[63][64] また、ガイウス・ユリウス・カエサルが『ガリア戦記』[65]の中でルクレティウスの著作に様々な形で言及していると考えられている。同様に、ローマの詩 人ウェルギリウスも『農耕詩』第二巻でルクレティウスとその著作を参照している。彼はこう記した: 「万物の原因を見抜き、あらゆる恐怖と避けがたい運命、貪欲なる冥界の轟音を足元に踏みしめた者は幸いである」(felix qui potuit rerum cognoscere causas/atque metus omnis et inexorabile fatum/subiecit pedibus strepitumque Acherontis avari)。[5][66][67] スタンフォード哲学百科事典のデイヴィッド・セドリーによれば、「この称賛の言葉で、ウェルギリウスは詩の四つの主要テーマを端的に要約している。すなわ ち、普遍的な因果説明、それによる世界の脅威の排除、自由意志の正当化、そして死後の魂の存続の否定である」[5] ルクレティウスは、帝政期の詩人マルクス・マニリウス(活動時期:紀元1世紀)によってほぼ確実に読まれていた。マニリウスの教訓詩『天文論』(紀元 10~20年頃執筆)は、複数の箇所で『物事の性質について』に言及している。[68] しかしマニリウスの詩はストア派的な決定論的宇宙観を支持しており[69]、その本質上、ルクレティウスの世界観の哲学的基盤そのものを攻撃している [68]。このためカタリーナ・フォルクら学者は「マニリウスは真の反ルクレティウスである」と論じている。[68] さらにマニリウスはこの詩全体を通じて、自らの作品がルクレティウスのそれを凌駕していると示唆しているようだ。[70] (偶然にも『物事の性質について』と『天文誌』は、15世紀初頭にポッジョ・ブラッチョリーニによって再発見された。)[71] 加えて、ルクレティウスの著作はアウグストゥス時代の詩人オウィディウスによって論じられており、彼は『アモーレス』の中で「崇高なるルクレティウスの詩 句は、世界の終焉をもたらす日が来る時のみ滅びるだろう」 (Carmina sublimis tunc sunt peritura Lucreti / exitio terras cum dabit una dies)。[72] また、銀時代詩人スタティウスは『シルヴァエ』において、ルクレティウスを「博識」と高く称賛している。[73][74] デイヴィッド・バターフィールドもまた、『物事の性質について』に対する「明らかな反響や応答」が、ローマのエレジー詩人カトゥッルス、プロペルティウ ス、ティブルス、そして抒情詩人ホラティウスの作品にも見出せると記している。[75] 散文作家に関しては、多くの者がルクレティウスの詩を引用するか、『物事の性質について』への深い賞賛を表明している。これにはウィトルウィウス(『建築 論』において)、[76][77]マルクス・ウェレイウス・パテルクルス(『ローマ史』において)、[77][78]クインティリアヌス(『弁論術教本』 において)、 [73][79] タキトゥス(『弁論家論』において)、[73][80] マルクス・コルネリウス・フロンティウス(『雄弁論』において)、[81][82] コルネリウス・ネポス(『アッティクスの生涯』において)、[77][83] アプュレイウス(『ソクラテスの神について』において)、 [84][85] ガイウス・ユリウス・ヒュギヌス(『神話集』)[86][87]。さらに、プリニウス長老は『自然誌』の冒頭でルクレティウス(おそらく『物事の性質につ いて』を指す)を出典として挙げ、セネカ若者は自身の複数の著作で『物事の性質について』から六箇所を引用している。[88][89] |

Late antiquity and the Middle Ages A fresco of Lactantius A painting of Isidore sitting consulting a book Lucretius was quoted by several early Christian writers, including Lactantius (left) and Isidore of Seville (right). Because Lucretius was critical of religion and the claim of an immortal soul, his poem was disparaged by most early Church Fathers.[90] The Early Christian apologist Lactantius, in particular, heavily cites and critiques Lucretius in his The Divine Institutes and its Epitome, as well as his De ira Dei.[90] While he argued that Lucretius's criticism of Roman religion were "sound attacks on paganism and superstition", Lactantius claimed that they were futile against the "True Faith" of Christianity.[91] Lactantius also disparages the science of De rerum natura (as well as of Epicureanism in general), calls Lucretius "the most worthless of the poets" (poeta inanissimus), notes that he is unable to read more than a few lines of De rerum natura without laughing, and sarcastically asks, "Who would think that [Lucretius] had a brain when he said these things?"[91] After Lactantius's time, Lucretius was almost exclusively referenced or alluded to in a negative manner by the Church Fathers. The one major exception to this was Isidore of Seville, who at the start of the 7th century produced a work on astronomy and natural history dedicated to the Visigothic king Sisebut that was entitled De natura rerum. In both this work and his more well-known Etymologiae (c. AD 600–625), Isidore liberally quotes from Lucretius a total of twelve times, drawing verses from all of Lucretius's books except his third.[92][93] (About a century later, the English historian and Doctor of the Church Bede produced a work also called De natura rerum, partly based on Isidore's work but apparently ignorant of Lucretius's poem.[94]) |

古代末期と中世 ラクタンティウスのフレスコ画 書物に目を通すイシドールの絵画 ルクレティウスは、ラクタンティウス(左)やセビリアのイシドール(右)を含む、いくつかの初期キリスト教作家によって引用された。 ルクレティウスは宗教や不滅の魂の主張を批判していたため、彼の詩はほとんどの初期教父たちによって軽蔑された。[90] 特に初期キリスト教の弁証家ラクタンスは、『神学概論』とその要約版、さらに『神の怒りについて』において、ルクレティウスを多用し批判している。 [90] ラクタンスは、ルクレティウスのローマ宗教批判が「異教と迷信に対する正当な攻撃」であると認めつつも、それらがキリスト教の「真の信仰」に対しては無力 だと主張した。[91] またラクタンスは『物事の性質について』の科学(およびエピクロス主義全般)を軽蔑し、ルクレティウスを「最も無価値な詩人」(poeta inanissimus)と呼び、『物事の性質について』の数行を読むだけで笑いを禁じ得ないと述べ、皮肉を込めて「彼がこうしたことを言うのに、誰が彼 に頭脳があると思うだろうか?」と問いかけている。[91] ラクタンティウスの時代以降、教会父たちはルクレティウスをほぼ例外なく否定的に言及または暗示した。唯一の主要な例外はセビリアのイシドールであり、7 世紀初頭に西ゴート王シセブトに献呈した天文学・自然史に関する著作『デ・ナトゥラ・レルム』(De natura rerum)を著した。この著作と、より有名な『語源論』(西暦600~625年頃)の両方で、イシドールスはルクレティウスから計12回にわたり自由に 引用している。引用箇所はルクレティウスの全著作から選ばれており、第三巻を除く全巻に及んでいる。[92][93] (約1世紀後、英国の歴史家であり教会の博士であるベダも『De natura rerum』と題する著作を著したが、これはイシドールの著作を部分的に基にしながらも、ルクレティウスの詩については明らかに知らなかったようだ。 [94]) |

| Renaissance to the present Montaigne owned a Latin edition published in Paris, in 1563, by Denis Lambin which he heavily annotated.[95] His Essays contain almost a hundred quotes from De rerum natura.[1] Additionally, in his essay "Of Books", he lists Lucretius along with Virgil, Horace, and Catullus as his four top poets.[96] Notable figures who owned copies include Ben Jonson, whose copy is held at the Houghton Library, Harvard; and Thomas Jefferson, who owned at least five Latin editions and English, Italian and French translations.[1] Lucretius has also had a marked influence upon modern philosophy, as perhaps the most complete expositor of Epicurean thought.[97] His influence is especially notable in the work of the Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana, who praised Lucretius—along with Dante and Goethe—in his book Three Philosophical Poets,[98] although he openly admired the poet's system of physics more so than his spiritual musings (referring to the latter as "fumbling, timid and sad").[99] In 2011, the historian and literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt wrote a popular history book about the poem, entitled The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. In the work, Greenblatt argues that Poggio Bracciolini's discovery of De rerum natura reintroduced important ideas that sparked the modern age.[100][101][102] The book was well-received, and later earned the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction and the 2011 National Book Award for Nonfiction.[103][104] |

ルネサンスから現代まで モンテーニュは、1563年にパリでデニス・ランバンが刊行したラテン語版を所有しており、これに大量の注釈を加えている。[95] 彼の『随筆集』には『物事の性質について』からの引用がほぼ百箇所含まれている。[1] さらに「書物について」という随筆では、ルクレティウスをウェルギリウス、ホラティウス、カトゥッルスと並んで四大詩人として挙げている。[96] 所有者として著名な人物には、ハーバード大学ホートン図書館に所蔵されるベン・ジョンソンの写本や、少なくとも5点のラテン語版と英語・イタリア語・フランス語訳を所有したトーマス・ジェファーソンがいる。[1] ルクレティウスはエピクロス思想の最も完全な解説者として、現代哲学にも顕著な影響を与えている。[97] その影響はスペイン系アメリカ人哲学者ジョージ・サンタヤナの著作で特に顕著だ。彼は『三人の哲学詩人』においてルクレティウスをダンテやゲーテと並んで 称賛しているが、[98] 詩人の物理学体系を精神的な思索(「不器用で臆病で悲観的」と評した)よりも高く評価していた。[99] 2011年、歴史家かつ文学研究者のスティーヴン・グリーンブラットは、この詩に関する一般向け歴史書『世界はどのようにして近代になったか』を著した。 同書でグリーンブラットは、ポッジョ・ブラッチョリーニによる『物事の性質について』の発見が、近代を触発した重要な思想を再導入したと論じている。 [100][101][102] この本は好評を博し、後に2012年ピューリッツァー賞ノンフィクション部門と2011年全米図書賞ノンフィクション部門を受賞した。[103] [104] |

| Editions 1683 English translation of De rerum natura Title page of a 1683 English translation De rerum natura Translations For a more comprehensive list, see List of English translations of De rerum natura. Lucretius (1968). The Way Things Are: The De Rerum Natura. Translated by Rolfe Humphries. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 025320125X. ———— (1994). On the Nature of the Universe. Translated by R. E. Latham. London, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140446109. ———— (1992) [1924]. On the Nature of Things. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by W. H. Rouse. Revised by Martin Ferguson Smith. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674992008. ———— (1995). On the Nature of Things: De rerum natura. Translated by Anthony M. Esolen. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 080185055X. ———— (1998). On the Nature of the Universe. Translated by Ronald Melville. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198150978. ———— (2001). On the Nature of Things. Hackett Classics Series. Translated by Martin Ferguson Smith. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company. ISBN 0872205878. ———— (2007). The Nature of Things. Penguin Classics. Translated by A.E. Stallings. London, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140447965. ———— (2008). De Rerum Natura (The Nature of Things): A Poetic Translation. Translated by David R. Slavitt. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520942769. ———— (2009). Philip De May (ed.). Lucretius: Poet and Epicurean. Cambridge Learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521721561. |

版 1683年英語訳『物事の性質について』 1683年英語訳『物事の性質について』のタイトルページ 翻訳 より包括的なリストについては、『物事の性質について』の英語訳一覧を参照のこと。 ルクレティウス (1968). 『物事のあり方:デ・レルム・ナチュラ』. 訳者:ロルフ・ハンフリーズ. インディアナ州ブルーミントン:インディアナ大学出版局. ISBN 025320125X。 ———— (1994). On the Nature of the Universe. R. E. Latham 訳。ロンドン、イングランド:ペンギンブックス。ISBN 0140446109。 ———— (1992) [1924]. On the Nature of Things. Loeb Classical Library. W. H. ラウス訳。マーティン・ファーガソン・スミス校訂。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 0674992008。 ———— (1995). 『物事の性質について:De rerum natura』。アンソニー・M・エソレン訳。ボルチモア:ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学出版局。ISBN 080185055X。 ———— (1998). 『宇宙の性質について』. ロナルド・メルヴィル訳. 英国オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0198150978. ———— (2001). 『物事の性質について』. ハケット・クラシック・シリーズ. マーティン・ファーガソン・スミス訳. インディアナ州インディアナポリス: ハケット出版. ISBN 0872205878。 ———— (2007). 『物事の本質』. ペンギン・クラシック. A.E. スタリングス訳. 英国ロンドン: ペンギンブックス. ISBN 9780140447965。 ———— (2008). 『物事の本質』: 詩的翻訳. デイヴィッド・R・スラヴィット訳。カリフォルニア州オークランド:カリフォルニア大学出版。ISBN 9780520942769。 ———— (2009). フィリップ・デ・メイ (編). ルクレティウス:詩人であり快楽主義者。ケンブリッジ・ラーニング。英国ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版。ISBN 9780521721561。 |

| Work cited Commentaries Beretta, Marco. Francesco Citti (edd), Lucrezio, la natura e la scienza (Firenze: Leo S. Olschki, 2008) (Biblioteca di Nuncius / Istituto e Museo distoria della scienza, Firenze; 66). Campbell, Gordon. Lucretius on Creation and Evolution: A Commentary on De rerum natura Book Five, Lines 772–1104 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003). Esolen, Anthony M. Lucretius On the Nature of Things (Baltimore, 1995). Fowler, Don. Lucretius on Atomic Motion: A Commentary on De rerum natura 2. 1–332 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). Godwin, John. Lucretius (London: Bristol Classical Press, 2004) ("Ancient in Action" Series). Melville, Ronald. Lucretius: On the Nature of the Universe (Oxford, 1997). Nail, Thomas. Lucretius I: An Ontology of Motion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018). Nail, Thomas. Lucretius II: An Ethics of Motion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020). Studies Alioto, Anthony M. (1987). A History of Western Science. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0133923908. Billanovich, Guido (1958). "'Veterum vestigia vatum' nei carmi dei preumanisti padovani". Italia Medievale e Umanistica (in Italian). I. Padua: Antenore: 155–243. ISBN 978-88-8455-089-7. Brandt, Samuel (1885). "Zur Chronologic des Gedichtes des Lucretius und zur Frage nach der Stellung des Memmius in demselben". Jahrbücher für classische Philologie (in German) (31): 601–13. Brown, P. Michael, ed. (1997). De rerum natura III. Aris & Phillips. ISBN 0856686948. Bruns, Ivo (1884). Lukrez-Studien (in German). Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany: J. C. B. Mohr – via the Internet Archive. Bullivant, Stephen; Ruse, Michael, eds. (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Atheism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0191667404 – via Google Books. Butterfield, David (2013). The Early Textual History of Lucretius' De rerum natura. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107037458. Campbell, Gordon (2003). Lucretius on Creation and Evolution: A Commentary on De rerum natura Book Five, Lines 772–1104. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199263965. Catto, Bonnie A. (1988). "Venus and Natura in Lucretius: "De Rerum Natura" 1.1–23 and 2.167–74". The Classical Journal. 84 (2): 97–104. JSTOR 3297566. DeMay, Philip. Lucretius: Poet and Epicurean (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009) (Series: Greece & Rome: texts and contexts). Deufert, Marcus. Pseudo-Lukrezisches im Lukrez (Berlin-New York, 1996). Dronke, Peter (1984). The Medieval Poet and His World. Rome, Italy: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura. Englert, Walter (2003). Lucretius: On the Nature of Things. Newburyport, MA: Focus Publishing. ISBN 978-0941051217. Erler M. "Lukrez," in H. Flashar (ed.), Die Philosophie der Antike. Bd. 4. Die hellenistische Philosophie (Basel, 1994), 381–490. Fowler, Don (2002). Lucretius on Atomic Motion: A Commentary on De rerum batura, Book Two, Lines 1–332. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199243581. Gale, Monica R. (1996) [1994]. Myth and Poetry in Lucretius. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Gale, Monica R. (2001), Lucretius and the Didactic Epic, London, England: Bristol Classical Press, ISBN 1853995576 Gale Monica R. (ed.), Oxford Readings in Classical Studies: Lucretius (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007). Garani, Myrto. Empedocles Redivivus: poetry and analogy in Lucretius. Studies in classics (London; New York: Routledge, 2007). Garner, Dwight (September 27, 2011), "An Unearthed Treasure That Changed Things", The New York Times, retrieved May 31, 2012 "Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. November 7, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2017. Gillespie, Stuart; MacKenzie, Donald (2007). "Lucretius and the Moderns". In Gillespie, Stuart; MacKenzie, Donald (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Lucretius. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521612661. Goldberg, Jonathan (2006). "Lucy Hutchinson Writing Matter". ELH. 73 (1): 275–301. doi:10.1353/elh.2006.0003. S2CID 162125154. Gray, John (2018). Seven Types of Atheism. London, England: Allen Lane. ISBN 9780241199411. Greenblatt, Stephen (August 8, 2011). "The Answer Man: An Ancient Poem Was Rediscovered—and the World Swerved". The New Yorker. Vol. LXXXVII, no. 23. Condé Nast. pp. 28–33. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. Greenblatt, Stephen (2011). The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393064476. Johnson, W.R (2000). Lucretius and the Modern World. London, England: Duckworth. ISBN 0715628828. Keith, Alison (2013). A Latin Epic Reader: Selections from Ten Epics. Mundelein, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci. ISBN 978-1610411103. Kendall, Calvin B.; Wallis, Faith, eds. (2010). "Bede and Lucretius". Bede: On the Nature of Things and on Times. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press. pp. 191–2. ISBN 978-1846314957. Kennedy, Duncan F. (2002). Rethinking Reality: Lucretius and the Textualization of Nature. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472112880. Leonard, William Ellery (1916). "Proem – Lucr. 1.1". Perseus Project. Tufts University. Retrieved February 20, 2017. Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles, eds. (1879). "Clinamen". A Latin Dictionary. Retrieved June 30, 2017 – via the Perseus Project. Lloyd, G. E. R. (1973). Greek Science after Aristotle. New York City: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0393043711. Lucretius (1893). J. H. Warburton Lee (ed.). T. Lucreti Cari De rerum natura Libri I-III. London, England: Macmillan Publishers. Lucretius (1937). Trevelyan, R. C. (ed.). De rerum natura. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Lucretius (1992) [1924]. "Introduction". On the Nature of Things. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Rouse, W. H. D. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674992008. Marković, Daniel. The Rhetoric of Explanation in Lucretius' De rerum natura (Leiden, Brill, 2008) (Mnemosyne, Supplements, 294). Lucretius (1994). "The Testimony of Lucretius". In Inwood, Brad; Gerson, Lloyd P. (eds.). The Epicurus Reader. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing. ISBN 9781603845830. Lucretius (2009). Philip de May (ed.). Lucretius: Poet and Epicurean. Cambridge Learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521721561. Owchar, Nick (November 20, 2011), "Book review: 'The Swerve: How the World Became Modern'", Los Angeles Times, retrieved May 31, 2012 Palmer, Ada (2014). Reading Lucretius in the Renaissance. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674725577. Pope, Michael (25 May 2023). Lucretius and the End of Masculinity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-24235-6. Ramsay, William (1867). "Lucretius". In William Smith (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 2. Rumpf L. Naturerkenntnis und Naturerfahrung. Zur Reflexion epikureischer Theorie bei Lukrez (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2003) (Zetemata, 116). Santayana, George (1922) [1910]. "Lucretius". Three Philosophical Poets: Lucretius, Dante, and Goethe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 19–72. Sedley, David (1998). Lucretius and the Transformation of Greek Wisdom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521570328. Sedley, David N. Lucretius and the Transformation of Greek Wisdom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008 [1998]). Sedley, David (August 10, 2013) [2003]. "Lucretius". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved June 29, 2017. Sheppard, Kenneth (2015). Anti-Atheism in Early Modern England 1580–1720: The Atheist Answered and His Error Confuted. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9004288164. Smith, M. F. (1992) [1924]. "Introduction". On the Nature of Things. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674992008. Strauss, Leo. "Notes on Lucretius," in Liberalism: Ancient and Modern (Chicago, 1968), 76–139. Stahl, William (1962). Roman Science: Origins, Development, and Influence to the Later Middle Ages. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. ASIN B003HJJE0I. Stearns, John Barker (1931). "Lucretius and Memmius". Classical World. 25. Volk, Katharina (2009). Manilius and His Intellectual Background. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199265220. West, Stephanie (2007). "Terminal Problems". Hesperos: Studies in Ancient Greek Poetry Presented to M. L. West on His Seventieth Birthday. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–21. ISBN 978-0199285686. |

引用文献 解説 ベレッタ、マルコ。フランチェスコ・チッティ(編)、『ルクレティウス、自然、そして科学』(フィレンツェ:レオ・S・オルスキ、2008年)(ヌンキウス図書館/科学史研究所・博物館、フィレンツェ;66)。 キャンベル、ゴードン。『創造と進化に関するルクレティウス:De rerum natura 第 5 巻、772~1104 行に関する解説』(オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局、2003 年)。 エソレン、アンソニー M。『物事の性質に関するルクレティウス』(ボルチモア、1995 年)。 ファウラー、ドン。『原子運動に関するルクレティウス:De rerum natura 2. 1–332 の解説』(オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局、2002年)。 ゴッドウィン、ジョン。『ルクレティウス』(ロンドン:ブリストル古典出版、2004年)(「Ancient in Action」シリーズ)。 メルヴィル、ロナルド。『ルクレティウス:宇宙の性質について』(オックスフォード、1997年)。 ネイル、トーマス。『ルクレティウス I:運動の存在論』(エディンバラ:エディンバラ大学出版、2018年)。 ネイル、トーマス。『ルクレティウス II:運動の倫理』(エディンバラ:エディンバラ大学出版、2020年)。 研究 アリオート、アンソニー・M(1987)。『西洋科学の歴史』。ニュージャージー州イングルウッドクリフス:プレンティス・ホール。ISBN 0133923908。 ビラノヴィッチ、グイド(1958)。「パドヴァのプレウマニストたちの詩における『Veterum vestigia vatum』」。『中世イタリアと人文主義』(イタリア語) 。I. パドヴァ:アンテノーレ:155–243。ISBN 978-88-8455-089-7。 ブラント、サミュエル(1885)。「ルクレティウスの詩の年代学と、その中でのメミウスの位置に関する問題について」。古典文献学年報(ドイツ語) (31): 601–13。 ブラウン、P. マイケル、編(1997)。『物事の性質について III』。アリス&フィリップス。ISBN 0856686948。 ブルンス、イヴォ(1884)。『ルクレティウス研究』(ドイツ語)。フライブルク・イム・ブライスガウ、ドイツ:J. C. B. モア – インターネットアーカイブ経由。 Bullivant, Stephen; Ruse, Michael, eds. (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Atheism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0191667404 – Google Books経由。 Butterfield, David (2013). The Early Textual History of Lucretius' De rerum natura. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107037458。 Campbell, Gordon (2003). Lucretius on Creation and Evolution: A Commentary on De rerum natura Book Five, Lines 772–1104. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199263965. キャット、ボニー A. (1988). 「ルクレティウスの『物事の性質について』における金星と自然:1.1–23 および 2.167–74」. The Classical Journal. 84 (2): 97–104. JSTOR 3297566. DeMay, Philip. 『ルクレティウス:詩人であり快楽主義者』(ケンブリッジ、ニューヨーク:ケンブリッジ大学出版、2009年)(シリーズ:ギリシャとローマ:テキストと文脈)。 Deufert, Marcus. 『ルクレティウスにおける偽ルクレティウス』(ベルリン・ニューヨーク、1996年)。 Dronke, Peter (1984). 中世の詩人とその世界。イタリア、ローマ:Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura。 エンゲルト、ウォルター(2003)。ルクレティウス:物事の性質について。マサチューセッツ州ニューベリーポート:フォーカス出版。ISBN 978-0941051217。 エルラー M. 「ルクレティウス」、『古代の哲学』 H. フラッシャー(編)、第 4 巻。ヘレニズム哲学。バーゼル、1994 年、381–490。ファウラー、ドン(2002)。原子運動に関するルクレティウス:注釈。Bd. 4. Die hellenistische Philosophie (Basel, 1994), 381–490. ファウラー、ドン (2002)。原子運動に関するルクレティウス:De rerum batura、第 2 巻、1–332 行に関する解説。英国オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 0199243581。 ゲイル、モニカ R. (1996) [1994]。『ルクレティウスの神話と詩』。英国ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ゲイル、モニカ R. (2001)、『ルクレティウスと教訓的叙事詩』、英国ロンドン:ブリストル古典出版、ISBN 1853995576 ゲイル・モニカ R. (編)、オックスフォード古典学読本:ルクレティウス (オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局、2007)。 ガラニ、ミルト。エンペドクレス・レディヴィヴス:ルクレティウスの詩と類推。古典学研究 (ロンドン、ニューヨーク:ラウトレッジ、2007)。 ガーナー、ドワイト(2011年9月27日)、「物事を変えた発掘された宝物」、ニューヨーク・タイムズ、2012年5月31日取得 「ジャン・フランチェスコ・ポッジョ・ブラッチョリーニ」。ブリタニカ国際大百科事典。ブリタニカ国際大百科事典社。2013年11月7日。2017年6月29日取得。 Gillespie, Stuart; MacKenzie, Donald (2007). 「ルクレティウスと現代人」 Gillespie, Stuart; MacKenzie, Donald (eds.) 『ケンブリッジ・ルクレティウス・コンパニオン』 ケンブリッジ、英国:ケンブリッジ大学出版局 ISBN 978-0521612661 Goldberg, Jonathan (2006). 「ルーシー・ハッチンソン、物質について書く」. ELH. 73 (1): 275–301. doi:10.1353/elh.2006.0003. S2CID 162125154. Gray, John (2018). 『七つの無神論』. ロンドン、イングランド:アレン・レーン。ISBN 9780241199411。 グリーンブラット、スティーブン(2011年8月8日)。「答え人:古代の詩が再発見され、世界は方向転換した」。ニューヨーカー。第 LXXXVII 巻、第 23 号。コンデナスト。28–33 ページ。ISSN 0028-792X。2011年11月15日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。 グリーンブラット、スティーブン(2011)。『The Swerve: How the World Became Modern』。ニューヨーク:W. W. Norton & Company。ISBN 978-0393064476。 Johnson, W.R (2000). 『ルクレティウスと現代世界』. ロンドン、イングランド: Duckworth. ISBN 0715628828. Keith, Alison (2013). 『ラテン語叙事詩読本:10の叙事詩からの抜粋』. イリノイ州マンデレイン: Bolchazy-Carducci. ISBN 978-1610411103. ケンドール、カルビン B.、ウォリス、フェイス、編 (2010). 「ベダとルクレティウス」. 『ベダ:物事の本質と時間について』. イギリス、リバプール:リバプール大学出版局. pp. 191–2. ISBN 978-1846314957. ケネディ、ダンカン F. (2002). 現実の再考:ルクレティウスと自然のテキスト化。ミシガン州アナーバー:ミシガン大学出版局。ISBN 0472112880。 レナード、ウィリアム・エラリー(1916)。「序文 – Lucr. 1.1」。ペルセウス・プロジェクト。タフツ大学。2017年2月20日取得。 ルイス、チャールトン T.、ショート、チャールズ編(1879)。「クリナメン」。『ラテン語辞典』。2017年6月30日取得 – ペルセウス・プロジェクト経由。 ロイド、G. E. R. (1973)。『アリストテレス後のギリシャ科学』。ニューヨーク:W. W. ノートン。ISBN 0393043711。 ルクレティウス (1893). J. H. ウォーバートン・リー (編). T. Lucreti Cari De rerum natura Libri I-III. ロンドン、イングランド: マクミラン出版社. ルクレティウス (1937). トレヴェリアン、R. C. (編). De rerum natura. ケンブリッジ、英国: ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ルクレティウス (1992) [1924]。「序文」。『物事の性質について』。ローブ古典文庫。Rouse, W. H. D. 訳。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 0674992008。 マルコヴィッチ、ダニエル。『ルクレティウスの『物事の性質について』における説明のレトリック』(ライデン、ブリル、2008年)(ムネモシュネ、サプリメント、294)。 ルクレティウス(1994)。「ルクレティウスの証言」。インウッド、ブラッド;ガーソン、ロイド P.(編)。The Epicurus Reader. インディアナポリス、IN: Hackett Publishing. ISBN 9781603845830. ルクレティウス (2009). フィリップ・デ・メイ (編). Lucretius: Poet and Epicurean. Cambridge Learning. ケンブリッジ、英国: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521721561. オウチャー、ニック(2011年11月20日)、「書評:『The Swerve: How the World Became Modern』」、『ロサンゼルス・タイムズ』、2012年5月31日取得。 パーマー、エイダ(2014)。『ルクレティウスをルネサンスで読む』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0674725577。 Pope, Michael (2023年5月25日). 『ルクレティウスと男らしさの終焉』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 978-1-009-24235-6. Ramsay, William (1867). 「ルクレティウス」. William Smith (編). 『ギリシャ・ローマ伝記・神話辞典』. 第2巻. Rumpf L. Naturerkenntnis und Naturerfahrung. Zur Reflexion epikureischer Theorie bei Lukrez (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2003) (Zetemata, 116). Santayana, George (1922) [1910]. 「ルクレティウス」. Three Philosophical Poets: Lucretius, Dante, and Goethe. ケンブリッジ、マサチューセッツ州:ハーバード大学出版局。19-72 ページ。 セドリー、デイヴィッド(1998)。『ルクレティウスとギリシャの叡智の変容』。ケンブリッジ、英国:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0521570328。 セドリー、デイヴィッド N. 『ルクレティウスとギリシャの叡智の変容』(ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2008 [1998]) 。 セドリー、デイヴィッド(2013年8月10日) [2003]。「ルクレティウス」。スタンフォード哲学百科事典。2017年6月29日取得。 シェパード、ケネス(2015)。『近世イングランドにおける反無神論 1580–1720:無神論者への反論と彼の誤謬の反駁』。ライデン、オランダ:ブリル出版社。ISBN 978-9004288164。 スミス、M. F. (1992) [1924]。「序文」。『物事の本質について』。ローブ古典文庫。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 0674992008。 シュトラウス、レオ。「ルクレティウスに関する注記」、『自由主義:古代と現代』(シカゴ、1968年)、76–139。 スタール、ウィリアム(1962)。『ローマの科学:起源、発展、そして中世後期への影響』。ウィスコンシン州マディソン:ウィスコンシン大学出版局。ASIN B003HJJE0I。 スターンズ、ジョン・バーカー(1931)。「ルクレティウスとメンミウス」。『古典世界』25。 フォルク、カタリーナ(2009)。『マニリウスとその知的背景』。英国オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0199265220。 ウェスト、ステファニー(2007)。「終末の問題」。ヘスペロス:M. L. ウェストの 70 歳の誕生日に捧げる古代ギリシャ詩の研究。英国オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。3-21 ページ。ISBN 978-0199285686。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_rerum_natura |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099