コンストラクティヴィズム

Constructivism in art

Klinom

Krasnym Bej Belych

☆構成主義(Constructivism)

は、1915年にウラジーミル・タトリンとアレクサンダー・ロドチェンコによって創設された20世紀初頭の芸術運動である。抽象的で厳格な構成主義の芸術

は、近代産業社会と都市空間を反映することを目指していた。[1] この運動は、装飾的な様式化を拒否し、工業的な素材の組み合わせを好んだ。[1]

構成主義者は、プロパガンダや社会的目的のための芸術を支持し、ソビエト社会主義、ボルシェビキ、ロシアの前衛芸術と関連していた。[2]

構成主義の建築と芸術は、20世紀の現代美術運動に大きな影響を与え、バウハウスやデ・ステイル運動などの主要な潮流に影響を与えた。その影響は広範囲に

及び、建築、彫刻、グラフィックデザイン、工業デザイン、演劇、映画、ダンス、ファッション、そしてある程度は音楽にも大きな影響を与えた。現代の労働移

民理論

| Constructivism is an

early twentieth-century art movement founded in 1915 by Vladimir Tatlin

and Alexander Rodchenko.[1] Abstract and austere, constructivist art

aimed to reflect modern industrial society and urban space.[1] The

movement rejected decorative stylization in favour of the industrial

assemblage of materials.[1] Constructivists were in favour of art for

propaganda and social purposes, and were associated with Soviet

socialism, the Bolsheviks and the Russian avant-garde.[2] Constructivist architecture and art had a great effect on modern art movements of the 20th century, influencing major trends such as the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements. Its influence was widespread, with major effects upon architecture, sculpture, graphic design, industrial design, theatre, film, dance, fashion and, to some extent, music. |

構成主義は、1915年にウラジーミル・タトリンとアレクサンダー・ロ

ドチェンコによって創設された20世紀初頭の芸術運動である。抽象的で厳格な構成主義の芸術は、近代産業社会と都市空間を反映することを目指していた。

[1] この運動は、装飾的な様式化を拒否し、工業的な素材の組み合わせを好んだ。[1]

構成主義者は、プロパガンダや社会的目的のための芸術を支持し、ソビエト社会主義、ボルシェビキ、ロシアの前衛芸術と関連していた。[2] 構成主義の建築と芸術は、20世紀の現代美術運動に大きな影響を与え、バウハウスやデ・ステイル運動などの主要な潮流に影響を与えた。その影響は広範囲に 及び、建築、彫刻、グラフィックデザイン、工業デザイン、演劇、映画、ダンス、ファッション、そしてある程度は音楽にも大きな影響を与えた。現代の労働移 民理論 |

Beginnings The cover of Konstruktivizm by Aleksei Gan, 1922 Constructivism was a post-World War I development of Russian Futurism, and particularly of the 'counter reliefs' of Vladimir Tatlin, which had been exhibited in 1915. The term itself was invented by the sculptors Antoine Pevsner and Naum Gabo, who developed an industrial, angular style of work, while its geometric abstraction owed something to the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich. Constructivism first appears as a term in Gabo's Realistic Manifesto of 1920. Aleksei Gan used the word as the title of his book Constructivism, printed in 1922.[3] Constructivism as theory and practice was derived largely from a series of debates at the Institute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK) in Moscow, from 1920 to 1922. After deposing its first chairman, Wassily Kandinsky, for his 'mysticism', The First Working Group of Constructivists (including Liubov Popova, Alexander Vesnin, Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, and the theorists Aleksei Gan, Boris Arvatov and Osip Brik) would develop a definition of Constructivism as the combination of faktura: the particular material properties of an object, and tektonika, its spatial presence. Initially the Constructivists worked on three-dimensional constructions as a means of participating in industry: the OBMOKhU (Society of Young Artists) exhibition showed these three dimensional compositions, by Rodchenko, Stepanova, Karl Ioganson and the Stenberg brothers. Later the definition would be extended to designs for two-dimensional works such as books or posters, with montage and factography becoming important concepts. |

始まり アレクセイ・ガン著『コンストラクティヴィズム』表紙、1922年 コンストラクティヴィズムは第一次世界大戦後のロシア未来派の発展形であり、特に1915年に展示されたウラジーミル・タトリンの「カウンターレリーフ」 に端を発する。この用語自体は彫刻家アントワーヌ・ペヴスナーとナウム・ガボによって考案された。彼らは工業的で角張った作風を発展させたが、その幾何学 的抽象性はカジミール・マレーヴィチのシュプレマティズムの影響も受けていた。コンストラクティヴィズムという用語が初めて登場するのは、ガボの1920 年の『現実主義宣言』である。アレクセイ・ガンは1922年に刊行した自身の著書『コンストラクティヴィズム』の題名としてこの言葉を用いた。[3] 理論と実践としての構成主義は、1920年から1922年にかけてモスクワの芸術文化研究所(INKhUK)で行われた一連の討論から大きく派生した。初 代所長であるワシリー・カンディンスキーを「神秘主義」を理由に解任した後、 最初のコンストラクティヴィスト作業部会(リュボフ・ポポワ、アレクサンダー・ヴェスニン、ロドチェンコ、バルバラ・ステパノワ、そして理論家のアレクセ イ・ガン、ボリス・アルヴァトフ、オシップ・ブリックらで構成)は、コンストラクティヴィズムを「ファクトゥーラ(ファクトゥーラ:物体の特定の物質的特 性)とテクトニカ(空間的存在)の組み合わせ」と定義した。当初、構成主義者たちは、産業に参加する手段として、3次元構造物の制作に取り組んだ。 OBMOKhU(若手芸術家協会)の展示会では、ロドチェンコ、ステパノワ、カール・ヨガンソン、ステンバーグ兄弟によるこれらの3次元作品が展示され た。その後、その定義は、モンタージュやファクトグラフィーが重要な概念となる、書籍やポスターなどの2次元作品のデザインにも拡大された。 |

Art in the service of the Revolution Agitprop poster by Mayakovsky As much as involving itself in designs for industry, the Constructivists worked on public festivals and street designs for the post-October revolution Bolshevik government. Perhaps the most famous of these was in Vitebsk, where Malevich's UNOVIS Group painted propaganda plaques and buildings (the best known being El Lissitzky's poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919)). Inspired by Vladimir Mayakovsky's declaration 'the streets our brushes, the squares our palettes', artists and designers participated in public life during the Civil War. A striking instance was the proposed festival for the Comintern congress in 1921 by Alexander Vesnin and Liubov Popova, which resembled the constructions of the OBMOKhU exhibition as well as their work for the theatre. There was a great deal of overlap during this period between Constructivism and Proletkult, the ideas of which concerning the need to create an entirely new culture struck a chord with the Constructivists. In addition some Constructivists were heavily involved in the 'ROSTA Windows', a Bolshevik public information campaign of around 1920. Some of the most famous of these were by the poet-painter Vladimir Mayakovsky and Vladimir Lebedev. The constructivists tried to create works that would make the viewer an active viewer of the artwork. In this it had similarities with the Russian Formalists' theory of 'making strange', and accordingly their main theorist Viktor Shklovsky worked closely with the Constructivists, as did other formalists like the Arch Bishop. These theories were tested in theatre, particularly with the work of Vsevolod Meyerhold, who had established what he called 'October in the theatre'. Meyerhold developed a 'biomechanical' acting style, which was influenced both by the circus and by the 'scientific management' theories of Frederick Winslow Taylor. Meanwhile, the stage sets by the likes of Vesnin, Popova and Stepanova tested Constructivist spatial ideas in a public form. A more populist version of this was developed by Alexander Tairov, with stage sets by Aleksandra Ekster and the Stenberg brothers. These ideas would influence Germa |

革命に奉仕する芸術 マヤコフスキーによるアジプロップポスター 産業デザインに携わるのと同様に、構成主義者たちは十月革命後のボルシェビキ政府のために、公共の祭典や街頭デザインにも取り組んだ。おそらく最も有名な のはヴィテブスクでの活動で、マレーヴィチのUNOVISグループがプロパガンダの看板や建物を描いた(最も知られているのはエル・リシツキーのポスター 『赤い楔で白軍を打ち破れ』(1919年)である)。ウラジーミル・マヤコフスキーの「街は我々の絵筆、広場は我々のパレットだ」という宣言に触発され、 芸術家やデザイナーたちは内戦中に公共の生活に参加した。その顕著な例が、1921年にアレクサンダー・ヴェスニンとリュボフ・ポポワが提案したコミンテ ルン大会のためのフェスティバルである。これは、OBMOKhU 展の展示や、彼らの演劇のための作品に似たものだった。この時代、構成主義とプロレタリア文化(プロレカルト)の間には多くの共通点があった。まったく新 しい文化を創造する必要性に関するプロレカルトの考えは、構成主義者たちの共感を呼んだ。さらに、一部の構成主義者は、1920年頃のボルシェビキによる 広報キャンペーン「ロスタの窓」に深く関わっていた。このキャンペーンで最も有名な作品は、詩人であり画家でもあったウラジーミル・マヤコフスキーとウラ ジーミル・レベデフによるものである。 構成主義者たちは、鑑賞者を作品の前で能動的な存在とする作品を創ろうとした。この点でロシア形式主義の「異化」理論と共通点があり、主要理論家ヴィクト ル・シュクフスキーは構成主義者と緊密に協力した。アルチビショップら他の形式主義者も同様である。これらの理論は演劇で試され、特にフセヴォロド・メイ エルホールドの活動で実践された。彼は「劇場における十月革命」を提唱した。メイエルホールドは、サーカスとフレデリック・ウィンズロー・テイラーの「科 学的管理」理論の両方の影響を受けた「生体力学的」演技スタイルを開発した。一方、ヴェスニン、ポポワ、ステパノワらによる舞台美術は、構成主義の空間的 アイデアを公の場で試した。このより大衆的なバージョンは、アレクサンダー・タイロフによって開発され、アレクサンドラ・エクスターとステンバーグ兄弟が 舞台美術を担当した。これらのアイデアは、ゲルマに影響を与えることになる。 |

| Tatlin, 'Construction Art' and Productivism See also: Productivism (art) The key work of Constructivism was Vladimir Tatlin's proposal for the Monument to the Third International (Tatlin's Tower) (1919–20)[4] which combined a machine aesthetic with dynamic components celebrating technology such as searchlights and projection screens. Gabo publicly criticised Tatlin's design saying, "Either create functional houses and bridges or create pure art, not both." This had already caused a major controversy in the Moscow group in 1920 when Gabo and Pevsner's Realistic Manifesto asserted a spiritual core for the movement. This was opposed to the utilitarian and adaptable version of Constructivism held by Tatlin and Rodchenko. Tatlin's work was immediately hailed by artists in Germany as a revolution in art: a 1920 photograph shows George Grosz and John Heartfield holding a placard saying 'Art is Dead – Long Live Tatlin's Machine Art', while the designs for the tower were published in Bruno Taut's magazine Frühlicht. The tower was never built, however, due to a lack of money following the revolution.[5] Tatlin's tower started a period of exchange of ideas between Moscow and Berlin, something reinforced by El Lissitzky and Ilya Ehrenburg's Soviet-German magazine Veshch-Gegenstand-Objet which spread the idea of 'Construction art', as did the Constructivist exhibits at the 1922 Russische Ausstellung in Berlin, organised by Lissitzky. A Constructivist International was formed, which met with Dadaists and De Stijl artists in Germany in 1922. Participants in this short-lived international included Lissitzky, Hans Richter, and László Moholy-Nagy. However the idea of 'art' was becoming anathema to the Russian Constructivists: the INKhUK debates of 1920–22 had culminated in the theory of Productivism propounded by Osip Brik and others, which demanded direct participation in industry and the end of easel painting. Tatlin was one of the first to attempt to transfer his talents to industrial production, with his designs for an economical stove, for workers' overalls and for furniture. The Utopian element in Constructivism was maintained by his 'letatlin', a flying machine which he worked on until the 1930s. |

タトリン、『構築芸術』と生産主義 関連項目: 生産主義(芸術) 構成主義の代表作は、ウラジーミル・タトリンが提案した「第三インターナショナル記念碑」(タトリンの塔)(1919–20年)である[4]。これは機械 美学と、サーチライトや投影スクリーンといった技術を称える動的要素を組み合わせた作品だった。ガボはタトリンの設計を公に批判し、「機能的な家や橋を作 るか、純粋な芸術を作るか、両方ではない」と述べた。これは1920年にガボとペヴスナーの『現実主義宣言』が運動の精神的核を主張した際、モスクワグ ループ内で既に大きな論争を引き起こしていた。これはタトリンとロドチェンコが主張する実用的で適応可能な構成主義の立場とは対立するものだった。タトリ ンの作品はドイツの芸術家たちから即座に芸術革命として称賛された。1920年の写真にはゲオルク・グロスとジョン・ハートフィールドが「芸術は死んだ― タトリンの機械芸術万歳」と書かれたプラカードを掲げる姿が収められている。塔の設計図はブルーノ・タウトの雑誌『フルーリヒト』に掲載された。しかし革 命後の資金不足により、塔は結局建設されなかった。[5] タトリンの塔はモスクワとベルリンの間の思想交流の時代を幕開けさせた。この交流はエル・リシツキーとイリヤ・エーレンブルクのソビエト・ドイツ共同雑誌 『ヴェーシュ・ゲゲンスタンデ・オブジェ』によって強化され、「構築芸術」の思想を広めた。同様に、リシツキーが主催した1922年のベルリンにおける 「ロシア展」での構成主義展覧会もその役割を果たした。1922年にはドイツでダダイストやデ・ステイルの芸術家たちと会合した「構成主義インターナショ ナル」が結成された。この短命な国際組織の参加者にはリシツキー、ハンス・リヒター、ラースロー・モホリ=ナギらが名を連ねた。しかし「芸術」という概念 はロシア構成主義者にとって忌むべきものとなりつつあった。1920年から22年にかけてのINKhUK論争は、オシプ・ブリックらが提唱した生産主義理 論へと発展し、産業への直接参加とイーゼル絵画の終焉を要求したのである。タトリンは自らの才能を工業生産へ転用しようとした先駆者の一人であり、経済的 なストーブ、労働者用オーバーオール、家具の設計を手がけた。構成主義のユートピア的要素は、1930年代まで開発を続けた飛行機械「レタトリン」によっ て維持された。 |

| Constructivism and consumerism In 1921, the New Economic Policy was established in the Soviet Union, which opened up more market opportunities in the Soviet economy. Rodchenko, Stepanova, and others made advertising for the co-operatives that were now in competition with other commercial businesses. The poet-artist Vladimir Mayakovsky and Rodchenko worked together and called themselves "advertising constructors". Together they designed eye-catching images featuring bright colours, geometric shapes, and bold lettering. The lettering of most of these designs was intended to create a reaction, and function emotionally – most were designed for the state-owned department store Mosselprom in Moscow, for pacifiers, cooking oil, beer and other quotidian products, with Mayakovsky claiming that his 'nowhere else but Mosselprom' verse was one of the best he ever wrote. Additionally, several artists tried to work with clothes design with varying success: Varvara Stepanova designed dresses with bright, geometric patterns that were mass-produced, although workers' overalls by Tatlin and Rodchenko never achieved this and remained prototypes. The painter and designer Lyubov Popova designed a kind of Constructivist flapper dress before her early death in 1924, the plans for which were published in the journal LEF. In these works, Constructivists showed a willingness to involve themselves in fashion and the mass market, which they tried to balance with their Communist beliefs. |

構成主義と消費主義 1921年、ソビエト連邦で新経済政策が確立され、ソビエト経済においてより多くの市場機会が開かれた。ロドチェンコ、ステパノワらは、他の商業企業と競 合するようになった協同組合のための広告を手がけた。詩人兼芸術家のウラジーミル・マヤコフスキーとロドチェンコは共同で活動し、自らを「広告の構築者」 と呼んだ。彼らは鮮やかな色彩、幾何学模様、大胆な文字を特徴とした目を引くイメージを共同でデザインした。これらのデザインの文字の大半は反応を引き出 し、感情的に機能するよう意図されていた。その多くはモスクワの国営百貨店モセルプロム、乳首、食用油、ビール、その他の日用品向けにデザインされ、マヤ コフスキーは自身の「モセルプロム以外にはない」という詩句を、自身が書いた中で最高の作品の一つだと主張した。さらに、複数の芸術家が衣服デザインに挑 戦したが、成果はまちまちだった。ヴァルヴァーラ・ステパノワは鮮やかな幾何学模様を施したドレスをデザインし、大量生産に成功した。一方、タトリンとロ ドチェンコによる労働者用オーバーオールは試作段階に留まり、実現しなかった。画家兼デザイナーのリュボフ・ポポワは、1924年に若くして亡くなる前 に、ある種の構成主義的なフラッパードレスをデザインした。その設計図は雑誌『レフ』に掲載された。こうした作品において、構成主義者たちはファッション や大衆市場に関与しようとする意欲を示し、それを自らの共産主義的信念と調和させようとしたのである。 |

| LEF and Constructivist cinema The Soviet Constructivists organised themselves in the 1920s into the 'Left Front of the Arts', who produced the influential journal LEF, (which had two series, from 1923 to 1925 and from 1927 to 1929 as New LEF). LEF was dedicated to maintaining the avant-garde against the critiques of the incipient Socialist Realism, and the possibility of a capitalist restoration, with the journal being particularly scathing about the 'NEPmen', the capitalists of the period. For LEF the new medium of cinema was more important than the easel painting and traditional narratives that elements of the Communist Party were trying to revive then. Important Constructivists were very involved with cinema, with Mayakovsky acting in the film The Young Lady and the Hooligan (1919), Rodchenko's designs for the intertitles and animated sequences of Dziga Vertov's Kino Eye (1924), and Aleksandra Ekster designs for the sets and costumes of the science fiction film Aelita (1924). The Productivist theorists Osip Brik and Sergei Tretyakov also wrote screenplays and intertitles, for films such as Vsevolod Pudovkin's Storm over Asia (1928) or Victor Turin's Turksib (1929). The filmmakers and LEF contributors Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein as well as the documentarist Esfir Shub also regarded their fast-cut, montage style of filmmaking as Constructivist. The early Eccentrist movies of Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg (The New Babylon, Alone) had similarly avant-garde intentions, as well as a fixation on jazz-age America which was characteristic of the philosophy, with its praise of slapstick-comedy actors like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, as well as of Fordist mass production. Like the photomontages and designs of Constructivism, early Soviet cinema concentrated on creating an agitating effect by montage and 'making strange'. |

LEFと構成主義映画 ソビエトの構成主義者たちは1920年代に「芸術の左翼戦線」を結成した。彼らは影響力のある雑誌『LEF』を発行した(1923年から1925年まで と、1927年から1929年まで『新LEF』として二つのシリーズがあった)。LEFは、萌芽期の社会主義リアリズムの批判や資本主義復古の可能性に対 し、前衛芸術の維持に尽力した。特に当時の資本家層である「NEPメン」に対しては、同誌は痛烈な批判を加えた。LEFにとって、新たなメディアである映 画は、共産党の一部が当時復活を図っていたイーゼル絵画や伝統的物語形式よりも重要であった。重要な構成主義者たちは映画に深く関わった。マヤコフスキー は映画『お嬢さんとチンピラ』(1919年)に出演し、ロドチェンコはジガ・ヴェルトフの『キノ・アイ』(1924年)のインタータイトルとアニメーショ ンシーケンスをデザインし、アレクサンドラ・エクスターはSF映画『アエリタ』(1924年)のセットと衣装をデザインした。 生産主義理論家のオシプ・ブリックとセルゲイ・トレチャコフも、ヴセヴォロド・プードフキンの『アジアの嵐』(1928年)やヴィクトル・トゥーリンの 『トルクシブ』(1929年)などの映画で脚本やインタータイトルを手がけた。映画作家でありLEFの寄稿者であるジガ・ヴェルトフやセルゲイ・エイゼン シュテイン、そしてドキュメンタリー作家エスフィル・シュブも、彼らの高速カットとモンタージュによる映画制作スタイルを構成主義と見なしていた。グリゴ リー・コジンツェフとレオニード・トラウベルグによる初期のエキセントリスト映画(『新バビロン』『孤独』)も同様に前衛的な意図を持ち、ジャズ時代のア メリカへの執着が特徴的だった。これはチャーリー・チャップリンやバスター・キートンのようなスラップスティック・コメディ俳優や、フォード式大量生産を 称賛する哲学の表れである。構成主義のフォトモンタージュやデザインと同様に、初期ソビエト映画はモンタージュと「異化」によって扇動的な効果を生み出す ことに集中していた。 |

| Photography and photomontage Although originated in Germany, photomontage was a popular art form for Constructivists to create visually striking art and a method to convey change; "[6]". The Constructivists were early developers of the techniques of photomontage. Gustav Klutsis' 'Dynamic City' and 'Electrification of the Entire Country' (1919–20) are the first examples of this method of montage, which had in common with Dadaism the collaging together of news photographs and painted sections. Lissitzky's 'The Constructor' is one of many examples of photomontage that utilises photo collage to create a multi-layer composition. This brought forth the Constructor's artistic vision and technique of utilising 2D space with limited technology. However Constructivist montages would be less 'destructive' than those of Dadaism. Perhaps the most famous of these montages was Rodchenko's illustrations of the Mayakovsky poem About This. LEF also helped popularise a distinctive style of photography, involving jagged angles and contrasts and abstract use of light, which paralleled the work of László Moholy-Nagy in Germany: The major practitioners of this included, along with Rodchenko, Boris Ignatovich and Max Penson, among others. Kulagina, collaborating with Klutsis, utilised the use of photomontage to create political and personal posters of representative subjects from women in the workforce to satirise the humour of the local government. This also shared many characteristics with the early documentary movement. |

写真とフォトモンタージュ フォトモンタージュはドイツで生まれたが、構成主義者にとって視覚的に衝撃的な芸術を創造する人気のある芸術形式であり、変化を伝える方法であった。 「[6]」。構成主義者はフォトモンタージュ技術の初期の開発者であった。グスタフ・クルツィスの『動的な都市』と『全国電化』(1919-20年)は、 このモンタージュ技法の最初の例である。ダダ主義と共通して、ニュース写真と描画部分をコラージュしている。リシツキーの『建設者』は、写真コラージュを 用いて多層的な構図を創り出すフォトモンタージュの多くの例の一つだ。これにより、限られた技術で2次元空間を活用するコンストラクターの芸術的ビジョン と技法が生まれた。しかし構成主義のモンタージュはダダイズムのものより「破壊的」ではなかった。おそらく最も有名なモンタージュは、ロドチェンコによる マヤコフスキーの詩『これについて』の挿絵だろう。 LEFはまた、鋭角的な構図やコントラスト、光の抽象的利用といった独特の写真スタイルの普及に貢献した。これはドイツのラースロー・モホリ=ナギの作風 と並行するもので、ロドチェンコに加え、ボリス・イグナトヴィチやマックス・ペンソンらが主要な実践者であった。クラギナはクルツィスと共同で、フォトモ ンタージュを用いて政治的・個人的なポスターを制作した。労働する女性といった代表的な主題から、地方政府のユーモアを風刺するものまで多岐にわたった。 これは初期のドキュメンタリー運動とも多くの特徴を共有していた。 |

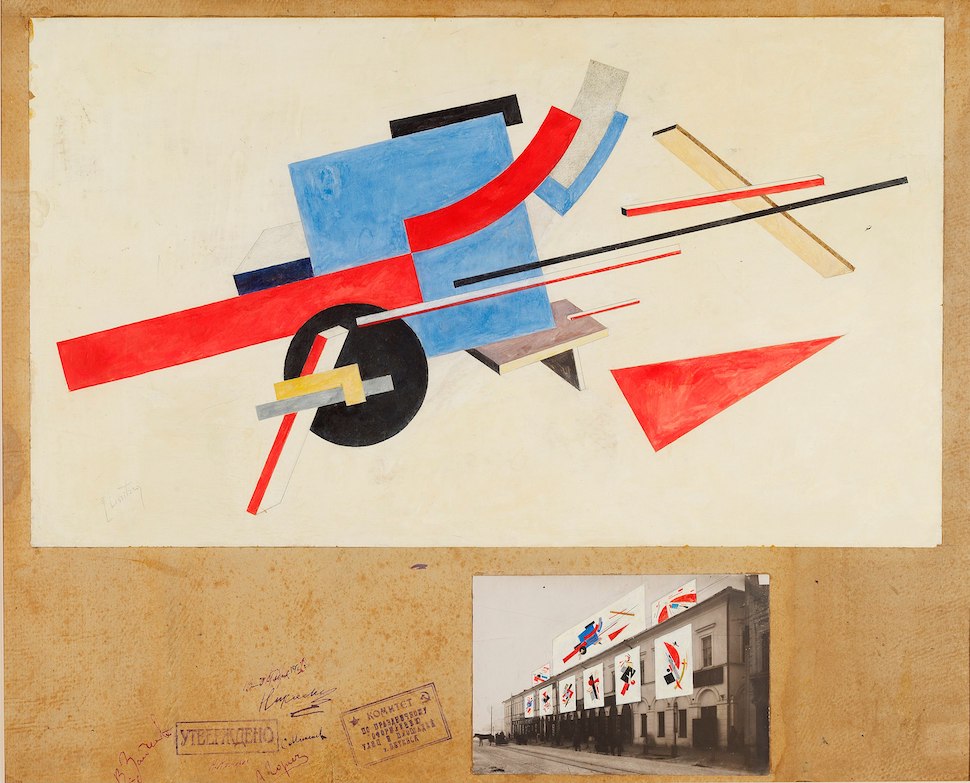

Constructivist graphic design Proposal for a PROUN street celebration, El Lissitzky, 1923. The book designs of Rodchenko, El Lissitzky and others such as Solomon Telingater and Anton Lavinsky were a major inspiration for the work of radical designers in the West, particularly Jan Tschichold. Many Constructivists worked on the design of posters for everything from cinema to political propaganda: the former represented best by the brightly coloured, geometric posters of the Stenberg brothers (Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg), and the latter by the agitational photomontage work of Gustav Klutsis and Valentina Kulagina. In Cologne in the late 1920s Figurative Constructivism emerged from the Cologne Progressives, a group which had links with Russian Constructivists, particularly Lissitzky, since the early twenties. Through their collaboration with Otto Neurath and the Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum such artists as Gerd Arntz, Augustin Tschinkel and Peter Alma affected the development of the Vienna Method. This link was most clearly shown in A bis Z, a journal published by Franz Seiwert, the principal theorist of the group.[7] They were active in Russia working with IZOSTAT and Tschinkel worked with Ladislav Sutnar before he emigrated to the US. The Constructivists' main early political patron was Leon Trotsky, and it began to be regarded with suspicion after the expulsion of Trotsky and the Left Opposition in 1927–28. The Communist Party would gradually favour realist art during the course of the 1920s (as early as 1918 Pravda had complained that government funds were being used to buy works by untried artists). However it was not until about 1934 that the counter-doctrine of Socialist Realism was instituted in Constructivism's place. Many Constructivists continued to produce avant-garde work in the service of the state, such as Lissitzky, Rodchenko and Stepanova's designs for the magazine USSR in Construction. |

構成主義のグラフィックデザイン エル・リシツキーによる「プロウン」街頭祝祭の提案、1923年。 ロドチェンコ、エル・リシツキー、そしてソロモン・テリンガターやアントン・ラヴィンスキーらによる書籍デザインは、西側の急進的なデザイナーたち、特に ヤン・チッホルトの作品に大きな影響を与えた。多くの構成主義者は、映画から政治プロパガンダに至るあらゆる分野のポスターデザインを手がけた。前者はス テンベルグ兄弟(ゲオルギーとウラジーミル・ステンベルグ)の鮮やかな色彩と幾何学的なポスターが代表例であり、後者はグスタフ・クルツィスやヴァレン ティーナ・クラギナによる扇動的なフォトモンタージュ作品が代表例である。 1920年代後半のケルンでは、ケルン・プログレッシブ派から具象的構成主義が生まれた。このグループは1920年代初頭からロシアの構成主義者、特にリ シツキーと繋がりを持っていた。オットー・ノイラートや社会経済博物館との協働を通じて、ゲルド・アルンツ、アウグスティン・チンケル、ペーター・アルマ といった芸術家たちはウィーン方式の発展に影響を与えた。この繋がりは、グループの主要理論家フランツ・ザイヴァルトが発行した雑誌『A bis Z』に最も明確に示されている[7]。彼らはロシアでIZOSTATと活動し、チンケルはラディスラフ・シュトナーが米国へ亡命する前に共に働いた。 構成主義者たちの初期の主要な政治的後援者はレオン・トロツキーであったが、1927年から1928年にかけてトロツキーと左翼反対派が追放されると、疑 いの目で見られるようになった。共産党は1920年代の過程で次第に写実主義芸術を支持するようになる(早くも1918年にはプラウダ紙が、政府資金が未 熟な芸術家の作品購入に使われていると批判していた)。しかし、コンストラクティヴィズムに代わる対抗理論としての社会主義リアリズムが確立されたのは、 1934年頃になってからである。リシツキー、ロドチェンコ、ステパノワらが雑誌『建設中のソ連』のために手掛けたデザインなど、多くのコンストラクティ ヴィストは国家のために前衛的な作品を制作し続けた。 |

Constructivist architecture Zuev Workers' Club, 1927–1929 Main article: Constructivist architecture Constructivist architecture emerged from the wider constructivist art movement. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, it turned its attentions to the new social demands and industrial tasks required of the new regime. Two distinct threads emerged, the first was encapsulated in Antoine Pevsner's and Naum Gabo's Realistic manifesto which was concerned with space and rhythm, the second represented a struggle within the Commissariat for Enlightenment between those who argued for pure art and the Productivists such as Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova and Vladimir Tatlin, a more socially oriented group who wanted this art to be absorbed in industrial production.[8] A split occurred in 1922 when Pevsner and Gabo emigrated. The movement then developed along socially utilitarian lines. The productivist majority gained the support of the Proletkult and the magazine LEF, and later became the dominant influence of the architectural group O.S.A., directed by Alexander Vesnin and Moisei Ginzburg. |

構成主義建築 ズエフ労働者クラブ、1927–1929年 詳細記事: 構成主義建築 構成主義建築は、より広範な構成主義芸術運動から生まれた。1917年のロシア革命後、それは新たな社会的要求と新体制に求められる産業的課題へと関心を 向けた。2つの異なる流れが生まれた。1つは、空間とリズムを重視したアントワーヌ・ペブズナーとナウム・ガボの「現実主義宣言」に代表されるものであ り、もう1つは、純粋芸術を主張する者たちと、アレクサンダー・ロドチェンコ、ヴァルヴァーラ・ステパノヴァ、ウラジーミル・タトリンといった、この芸術 を工業生産に吸収させたいと考える、より社会志向の強い生産主義者たちとの、啓蒙人民委員部内での争いを代表するものであった。[8] 1922年、ペブズナーとガボが亡命したことで分裂が起こった。その後、この運動は社会的に実用的な方向へと発展した。生産主義者の多数派は、プロレタリ ア文化(プロレトクルト)や雑誌「LEF」の支持を得て、後にアレクサンダー・ヴェスニンとモイセイ・ギンズバーグが率いる建築グループ O.S.A. の支配的な影響力となった。 |

Legacy The sculpture Toroa (1989) by Peter Nicholls in Dunedin, New Zealand shows the influence of constructivism. A number of Constructivists would teach or lecture at the Bauhaus schools in Germany, and some of the VKhUTEMAS teaching methods were adopted and developed there. Gabo established a version of Constructivism in England during the 1930s and 1940s that was adopted by architects, designers and artists after World War I (see Victor Pasmore), and John McHale. Joaquín Torres García and Manuel Rendón were instrumental in spreading Constructivism throughout Europe and Latin America. Constructivism had an effect on the modern masters of Latin America such as: Carlos Mérida, Enrique Tábara, Aníbal Villacís, Édgar Negret, Theo Constanté, Oswaldo Viteri, Estuardo Maldonado, Luis Molinari, Carlos Catasse, João Batista Vilanova Artigas and Oscar Niemeyer, to name just a few. There have also been disciples in Australia, the painter George Johnson being the best known. In New Zealand, the sculptures of Peter Nicholls show the influence of constructivism. In the 1980s graphic designer Neville Brody used styles based on Constructivist posters that initiated a revival of popular interest. Also during the 1980s designer Ian Anderson founded The Designers Republic, a successful and influential design company which used constructivist principles. Deconstructivism Main article: Deconstructivism So-called Deconstructivist architecture shares elements of approach with Constructivism (its name refers more to the deconstruction literary approach). It was developed by architects Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas and others during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Zaha Hadid by her sketches and drawings of abstract triangles and rectangles evokes the aesthetic of constructivism. Though similar formally, the socialist political connotations of Russian constructivism are deemphasized by Hadid's deconstructivism. Rem Koolhaas' projects revive another aspect of constructivism. The scaffold and crane-like structures represented by many constructivist architects are used for the finished forms of his designs and buildings. |

遺産 ニュージーランドのダニーデンにあるピーター・ニコルズの彫刻「トロア」(1989年)は、構成主義の影響を示している。 多くの構成主義者がドイツのバウハウス校で教鞭を執り、VKhUTEMASの教育手法の一部がそこで採用・発展した。ガボは1930年代から1940年代 にかけてイギリスで独自の構成主義を確立し、第一次世界大戦後の建築家、デザイナー、芸術家たちに採用された(ヴィクター・パスモア参照)。ジョン・マク ヘイルも同様である。ホアキン・トレス・ガルシアとマヌエル・レンドンは、構成主義をヨーロッパとラテンアメリカ全域に広める上で重要な役割を果たした。 コンストラクティビズムはラテンアメリカの近代巨匠たちにも影響を与えた。カルロス・メリダ、エンリケ・タバラ、アニバル・ビジャシス、エドガー・ネグ レ、テオ・コンスタンテ、オスワルド・ビテリ、エストゥアルド・マルドナド、ルイス・モリナリ、カルロス・カタッセ、ジョアン・バチスタ・ビラノバ・アル ティガス、オスカー・ニーマイヤーなどがその例だ。オーストラリアにも弟子たちがおり、画家ジョージ・ジョンソンが最もよく知られている。ニュージーラン ドでは、ピーター・ニコルズの彫刻が構成主義の影響を示している。 1980年代、グラフィックデザイナーのネヴィル・ブロディは、構成主義のポスターを基にしたスタイルを使用し、大衆の関心の復活のきっかけを作った。ま た、1980年代、デザイナーのイアン・アンダーソンは、構成主義の原則を用いた、成功し影響力のあるデザイン会社「ザ・デザイナーズ・リパブリック」を 設立した。 脱構築主義 主な記事:脱構築主義 いわゆる脱構築主義建築は、構成主義とアプローチの要素を共有している(その名称は、脱構築という文学的アプローチをより指している)。これは、20 世紀後半から 21 世紀初頭にかけて、建築家のザハ・ハディッド、レム・コールハースらによって発展した。ザハ・ハディッドは、抽象的な三角形や四角形のスケッチやドローイ ングによって、構成主義の美学を呼び起こしている。形式的には似ているものの、ロシアの構成主義の社会主義的な政治的意味合いは、ハディッドの脱構築主義 によって軽視されている。レム・コールハースのプロジェクトは、構成主義の別の側面を復活させている。多くの構成主義建築家が表現した足場やクレーンのよ うな構造が、彼のデザインや建築物の完成形に使用されている。 |

| Artists closely associated with Constructivism Ella Bergmann-Michel – (1896–1971) Norman Carlberg, sculptor (1928–2018) Avgust Černigoj – (1898–1985) John Ernest – (1922–1994) Naum Gabo – (1890–1977) Moisei Ginzburg, architect (1892–1946) Hermann Glöckner, painter and sculptor (1889–1987) Erwin Hauer – (1926–2017) Anthony Hill - (1930-2020) Hildegard Joos, painter (1909–2005) Gustav Klutsis – (1895–1938) Katarzyna Kobro – (1898–1951) Srečko Kosovel – (1904–1926) Jan Kubíček – (1927–2013) El Lissitzky – (1890–1941) Ivan Leonidov – architect (1902–1959) Richard Paul Lohse – painter and designer (1902–1988) Peter Lowe – (1938–) Louis Lozowick – (1892–1973) Berthold Lubetkin – architect (1901–1990) Thilo Maatsch – (1900–1983) Estuardo Maldonado – (1930–2023) Kenneth Martin – (1905–1984) Mary Martin – (1907–1969) Konstantin Medunetsky – (1899–1935) Konstantin Melnikov – architect (1890–1974) Vadim Meller – (1884–1962) László Moholy-Nagy – (1895–1946) Murayama Tomoyoshi – (1901–1977) Victor Pasmore – (1908–1998) Laszlo Peri – artist and architect (1899–1967) Antoine Pevsner – (1886–1962) Lyubov Popova – (1889–1924) Alexander Rodchenko – (1891–1956) Kurt Schwitters – (1887–1948) Franz Wilhelm Seiwert - (1894-1933) Manuel Rendón Seminario – (1894–1982) Willi Sandforth - (1922-2017) - German painter and designer Vladimir Shukhov – architect (1853–1939) Anton Stankowski – painter and designer (1906–1998) Jeffrey Steele – (1931–2021) Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg – poster designers and sculptors (1900–1933, 1899–1982) Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958) Władysław Strzemiński – painter (1893–1952) Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953) Joaquín Torres García (1874–1949) Vasiliy Yermilov (1894–1967) Alexander Vesnin – architect, painter and designer (1883–1957) Marlow Moss - painter and sculptor (1889–1958) |

構成主義と密接な関係のある芸術家 エラ・ベルクマン=ミシェル – (1896–1971) ノーマン・カールバーグ、彫刻家 (1928–2018) アヴグスト・チェルニゴイ – (1898–1985) ジョン・アーネスト – (1922–1994) ナウム・ガボ – (1890–1977) モイセイ・ギンズバーグ、建築家 (1892–1946) ヘルマン・グロックナー、画家、彫刻家 (1889–1987) エルヴィン・ハウアー – (1926–2017) アンソニー・ヒル - (1930-2020) ヒルデガルト・ヨース、画家(1909年~2005年) グスタフ・クルチス(1895年~1938年) カタジナ・コブロ(1898年~1951年) スレチコ・コソヴェル(1904年~1926年) ヤン・クビチェク(1927年~2013年) エル・リシツキー - (1890–1941) イワン・レオニドフ - 建築家 (1902–1959) リチャード・ポール・ローゼ - 画家、デザイナー (1902–1988) ピーター・ロウ - (1938–) ルイ・ロゾウィック – (1892–1973) ベルトルト・ルベトキン – 建築家 (1901–1990) ティロ・マッチャ – (1900–1983) エストゥアルド・マルドナド – (1930–2023) ケネス・マーティン – (1905–1984) メアリー・マーティン – (1907–1969) コンスタンチン・メドゥネツキー – (1899–1935) コンスタンチン・メルニコフ – 建築家 (1890–1974) ヴァディム・メラー – (1884–1962) ラースロー・モホリ=ナジ – (1895–1946) 村山知義 – (1901–1977) ヴィクター・パスモア – (1908–1998) ラースロー・ペリ – 芸術家、建築家 (1899–1967) アントワーヌ・ペブズナー – (1886–1962) リュボフ・ポポワ – (1889–1924) アレクサンドル・ロドチェンコ – (1891–1956) クルト・シュヴィッタース – (1887–1948) フランツ・ヴィルヘルム・ザイヴァルト - (1894-1933) マヌエル・レンドン・セミナリオ – (1894–1982) ウィリー・サンドフォース - (1922-2017) - ドイツの画家、デザイナー ウラジーミル・シュホフ – 建築家 (1853–1939) アントン・スタンコフスキー – 画家、デザイナー (1906–1998) ジェフリー・スティール - (1931–2021) ゲオルギー・ステンバーグとウラジーミル・ステンバーグ - ポスターデザイナー、彫刻家 (1900–1933, 1899–1982) ヴァルヴァーラ・ステパノヴァ (1894–1958) ウワディスワフ・ストシェミンスキ - 画家 (1893–1952) ウラジーミル・タトリン(1885年~1953年) ホアキン・トレス・ガルシア(1874年~1949年) ヴァシーリー・エルミロフ(1894年~1967年) アレクサンドル・ヴェスニン – 建築家、画家、デザイナー(1883年~1957年) マーロウ・モス – 画家、彫刻家(1889年~1958年) |

| Anti-art British Constructivists Cubist sculpture Systems Group |

反芸術 英国構成主義者 キュビズム彫刻 システムズ・グループ |

| References 1. "Constructivism". Tate Modern. Retrieved 9 April 2020. 2. Hatherley, Owen (4 November 2011). "The constructivists and the Russian revolution in art and achitecture". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 April 2020. 3. Catherine Cooke, Russian Avant-Garde: Theories of Art, Architecture and the City, Academy Editions, 1995, page 106. 4. Honour, H. and Fleming, J. (2009) A World History of Art. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, p. 819. ISBN 9781856695848 5. Janson, H.W. (1995) History of Art. 5th edn. Revised and expanded by Anthony F. Janson. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 820. ISBN 0500237018 6. a voice of gesture of his thoughts 7. Benus B. (2013) 'Figurative Constructivism and sociological graphics' in Isotype: Design and Contexts 1925–71 London: Hyphen Press, pp. 216–248 8. Oliver Stallybrass; Alan Bullock; et al. (1988). The Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (Paperback). Fontana press. p. 918 pages. ISBN 0-00-686129-6. |

参考文献 1. 「構成主義」. テート・モダン. 2020年4月9日閲覧. 2. Hatherley, Owen (2011年11月4日). 「構成主義者とロシア革命における芸術と建築」. ガーディアン. 2020年4月9日閲覧. 3. キャサリン・クック『ロシア前衛芸術:芸術・建築・都市の理論』アカデミー・エディションズ、1995年、106頁。 4. オーナー、H. と フレミング、J. (2009)『世界美術史』第7版。ロンドン:ローレンス・キング出版、819頁。ISBN 9781856695848 5. ジャンソン、H.W.(1995)『美術史』第5版。アンソニー・F・ジャンソンによる改訂・増補。ロンドン:テムズ&ハドソン、820頁。ISBN 0500237018 6. 彼の思考のジェスチャーの声 7. ベヌス B. (2013) 「具象的構成主義と社会学的グラフィックス」『アイソタイプ:デザインと文脈 1925–71』所収 ロンドン:ハイフン・プレス、216–248頁 8. オリバー・スタリーブラス; アラン・ブロック; 他 (1988). 『フォンタナ現代思想辞典』(ペーパーバック). フォンタナ・プレス. 918ページ. ISBN 0-00-686129-6. |

| Further reading Russian Constructivist Posters, edited by Elena Barkhatova. ISBN 2-08-013527-9. Bann, Stephen. The Documents of 20th-Century Art: The Tradition of Constructivism. The Viking Press. 1974. SBN 670-72301-0 Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter (2005). Design of the 20th Century (25th anniversary ed.). Köln: Taschen. pp. 176–177. ISBN 9783822840788. OCLC 809539744. Heller, Steven, and Seymour Chwast. Graphic Style from Victorian to Digital. New ed. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001. 53–57. Lodder, Christina. Russian Constructivism. Yale University Press; Reprint edition. 1985. ISBN 0-300-03406-7 Rickey, George. Constructivism: Origins and Evolution. George Braziller; Revised edition. 1995. ISBN 0-8076-1381-9 Alan Fowler. Constructivist Art in Britain 1913–2005. University of Southampton. 2006. PhD Thesis. Simon, Joshua (2013). Neomaterialism. Berlin: Sternberg Press. ISBN 978-3-943365-08-5. Gubbins, Pete. 2017. Constructivism to Minimal Art: from Revolution via Evolution (Winterley: Winterley Press). ISBN 978-0-9957554-0-6 Galvez, Paul. “Self-Portrait of the Artist as a Monkey-Hand.” October, vol. 93, 2000, pp. 109–37. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/779159. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023. |

追加文献(さらに読む) ロシア・コンストラクティビズムのポスター、エレナ・バルハトヴァ編。ISBN 2-08-013527-9。 バン、スティーブン。『20世紀美術の文書:コンストラクティビズムの伝統』。バイキング・プレス。1974年。SBN 670-72301-0 フィエル、シャーロット;フィエル、ピーター(2005)。『20世紀のデザイン』(25周年記念版)。ケルン:タッシェン。176–177頁。ISBN 9783822840788。OCLC 809539744。 ヘラー、スティーブン、およびシーモア・クワスト。『グラフィック・スタイル:ヴィクトリア朝からデジタルまで』新版。ニューヨーク:ハリー・N・エイブラムス社、2001年。53–57頁。 ロッダー、クリスティーナ。『ロシア・コンストラクティヴィズム』。イェール大学出版局;再版。1985年。ISBN 0-300-03406-7 リッキー、ジョージ。『構成主義:起源と進化』。ジョージ・ブラジラー社;改訂版。1995年。ISBN 0-8076-1381-9 アラン・ファウラー。『英国における構成主義美術 1913–2005』。サウサンプトン大学。2006年。博士論文。 サイモン、ジョシュア(2013)。『新物質主義』。ベルリン:シュテルンベルク・プレス。ISBN 978-3-943365-08-5。 ガビンズ、ピート。2017。『構成主義からミニマル・アートへ:革命から進化を経て』(ウィンターリー:ウィンターリー・プレス)。ISBN 978-0-9957554-0-6 ガルベス、ポール。「猿の手としての芸術家の自画像」。『オクトーバー』第93巻、2000年、109–137頁。JSTOR、https://doi.org/10.2307/779159。2023年4月15日アクセス。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constructivism_(art) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099