チェ・ゲバラ

Ernesto "Che" Guevara,

1928-1967

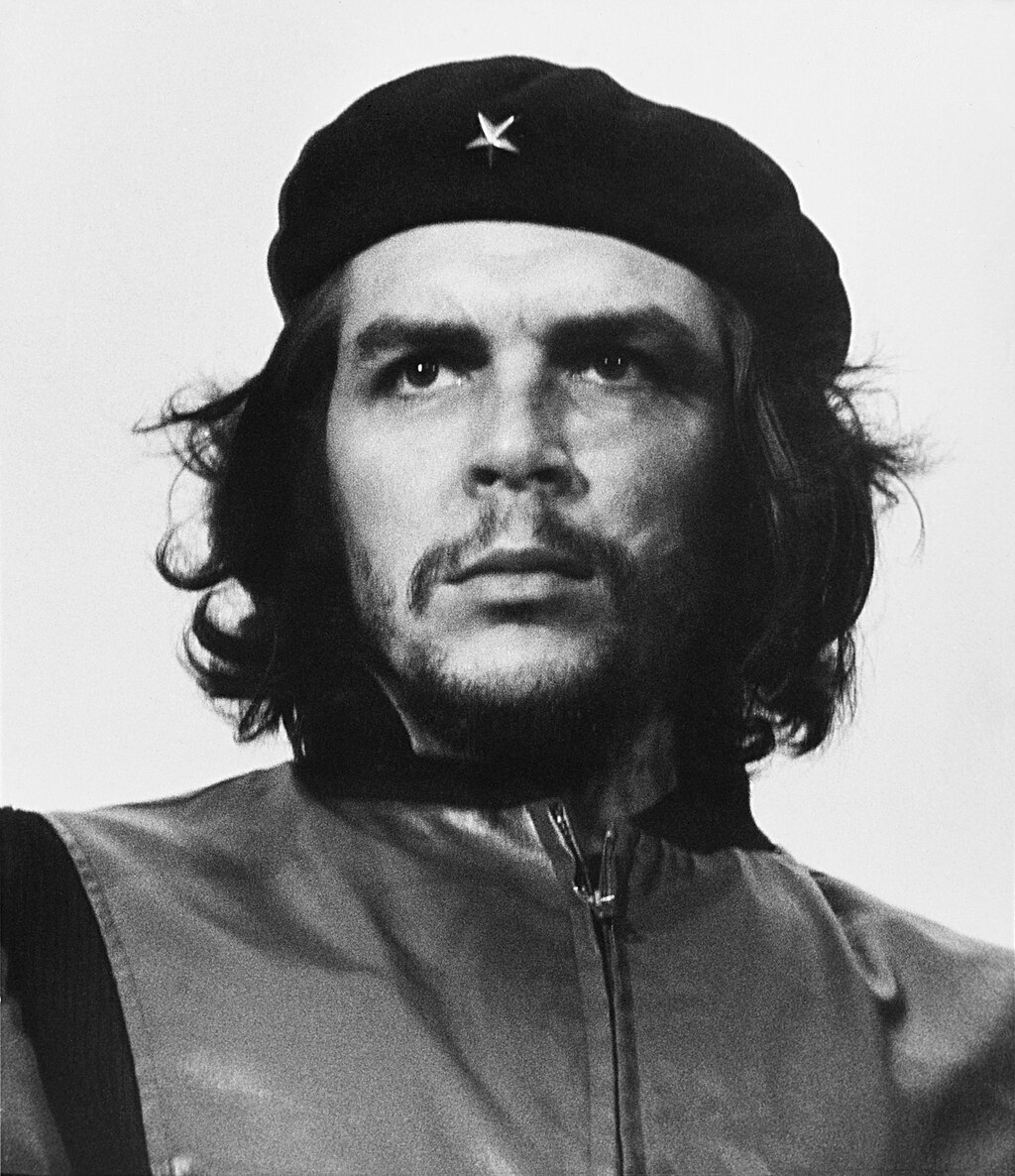

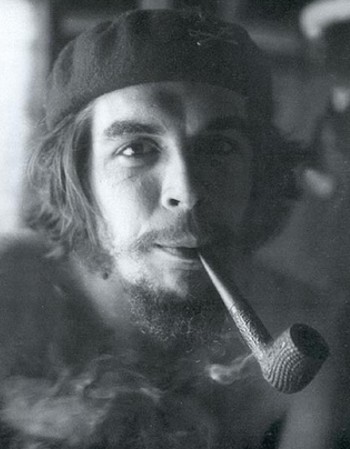

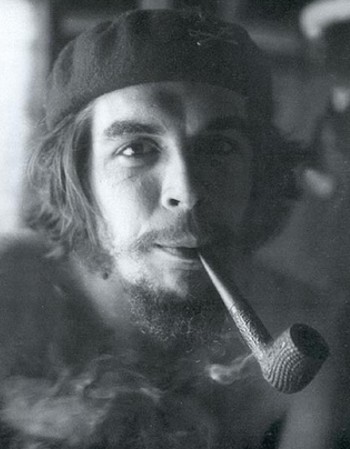

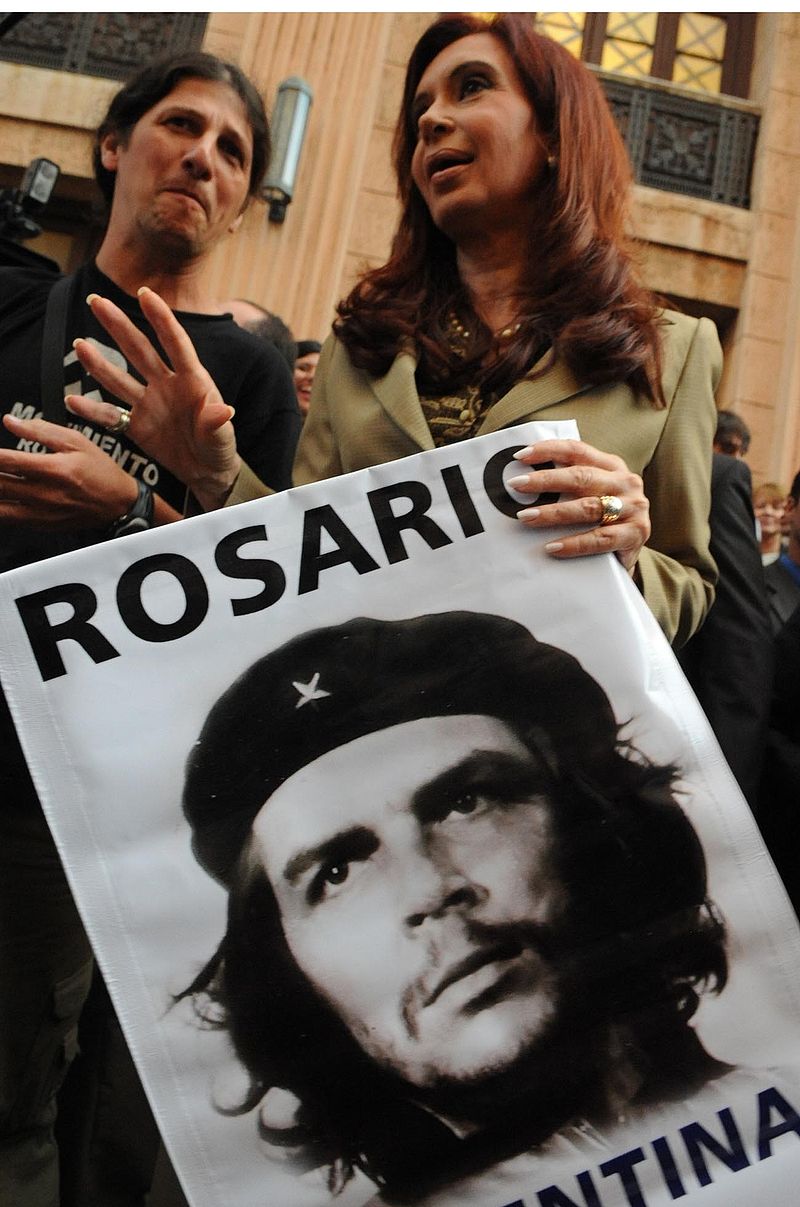

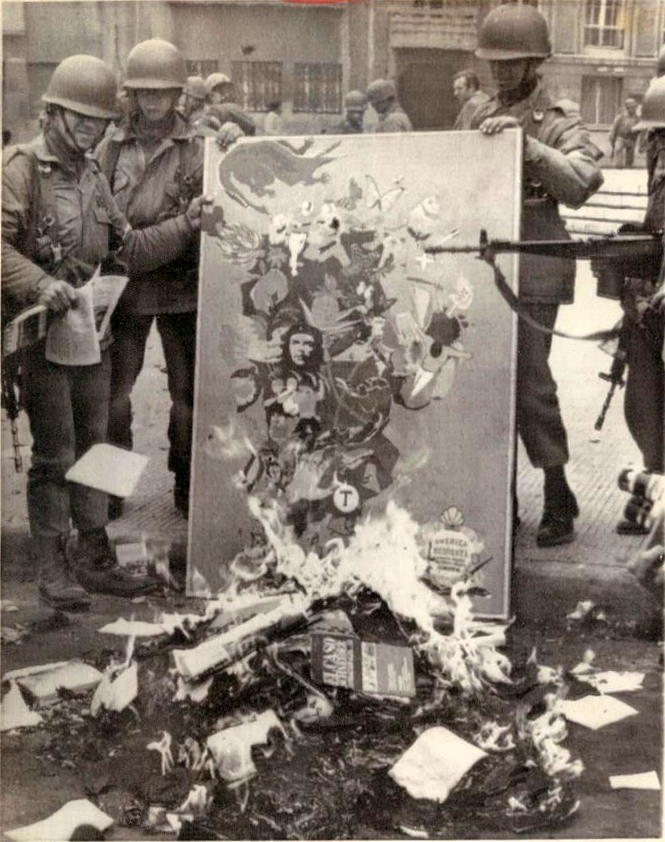

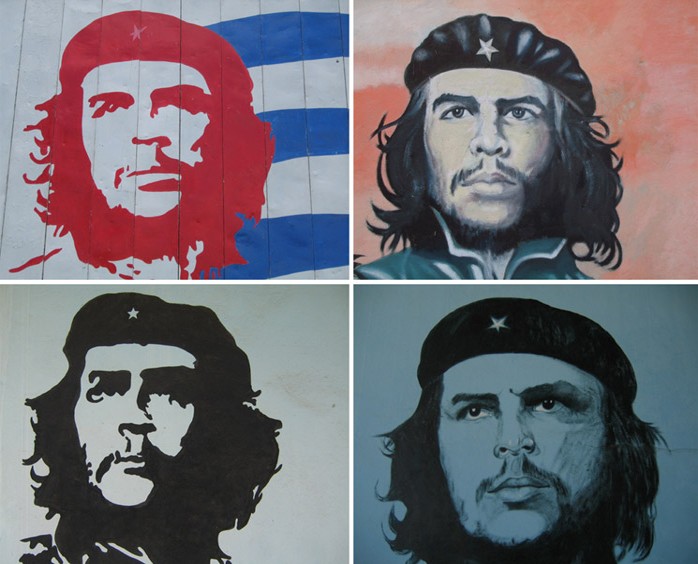

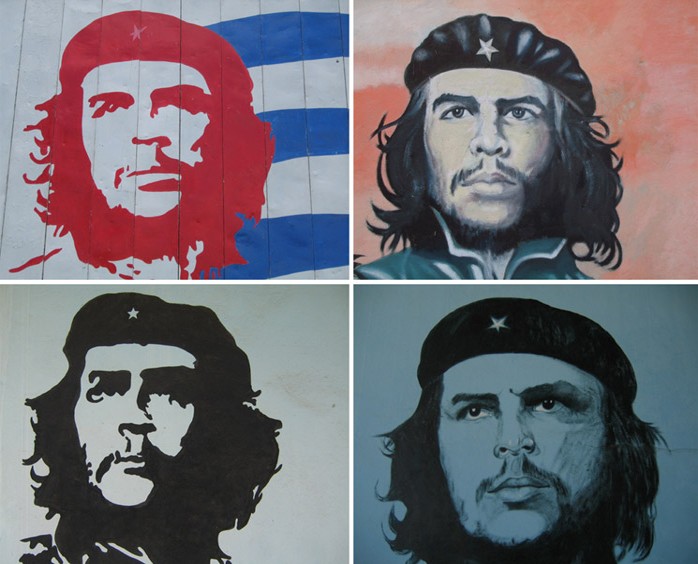

☆エルネスト・チェ・ゲバラ[チェはニックネーム](1928年5月14 日 - 1967年10月9日)は、アルゼンチンのマルクス主義革命家、医師、作家、ゲリラ指導者、外交官、政治家、軍事理論家。キューバ革命の主要人物であり、 その様式化された肖像は、反文化の象徴として、また大衆文化における世界的なシンボルとして広く知られている(→エルネスト・チェ・ゲバラ年譜)。

| Ernesto "Che" Guevara[b]

(14 May 1928[a] – 9 October 1967) was an Argentine Marxist

revolutionary, physician, author, guerrilla leader, diplomat,

politician and military theorist. A major figure of the Cuban

Revolution, his stylized visage has become a countercultural symbol of

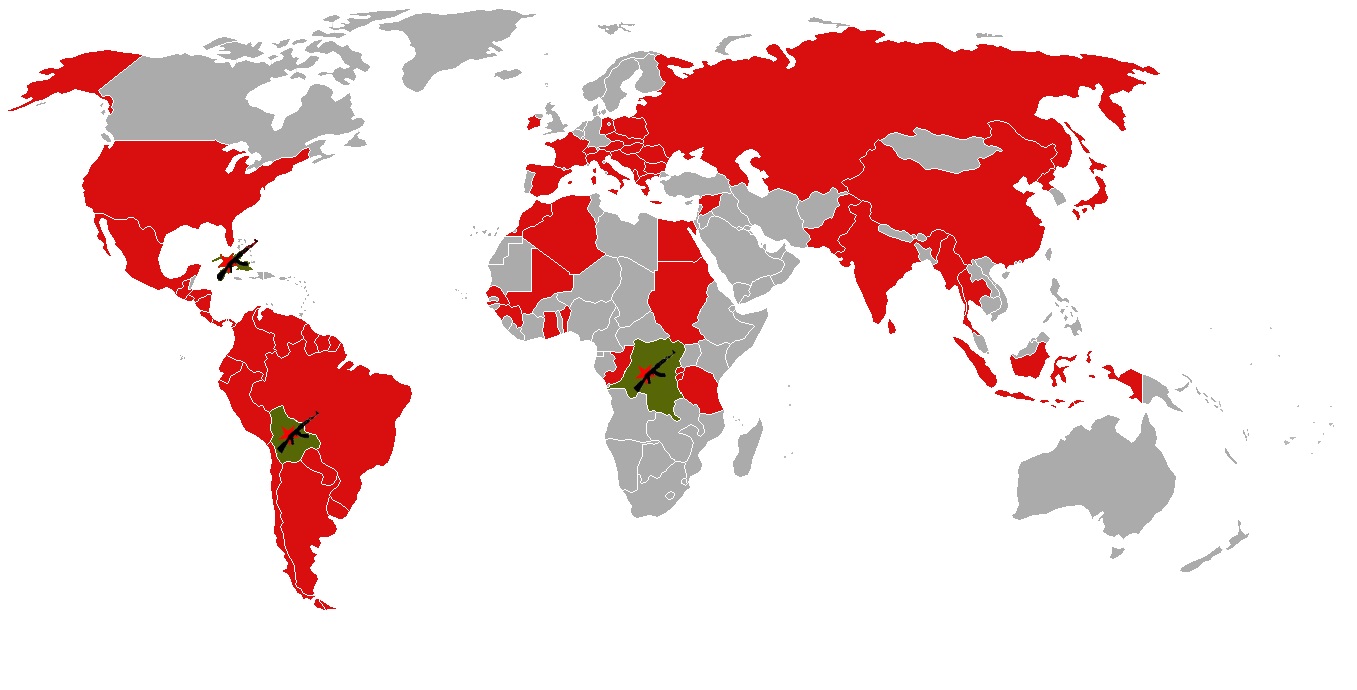

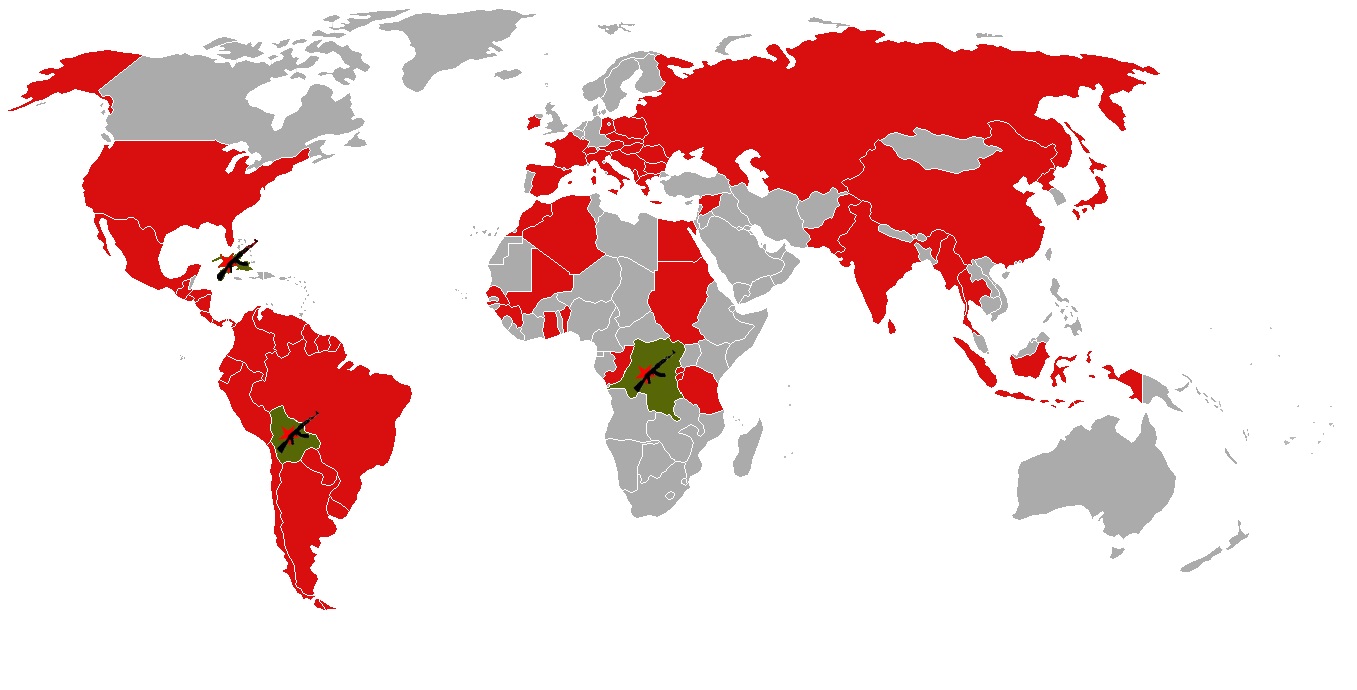

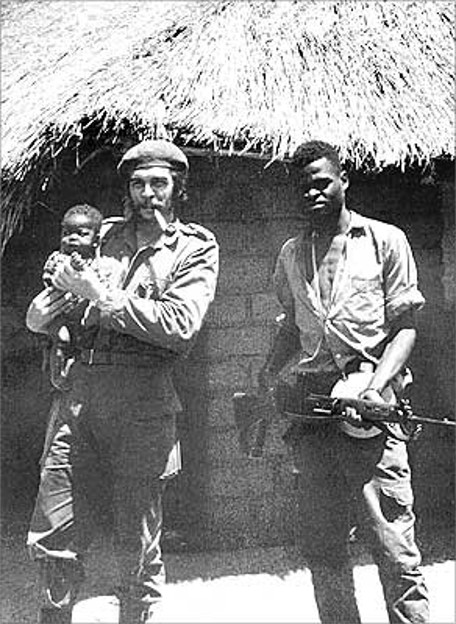

rebellion and global insignia in popular culture.[6] As a young medical student, Guevara travelled throughout South America and was appalled by the poverty, hunger, and disease he witnessed.[7][8] His burgeoning desire to help overturn what he saw as the capitalist exploitation of Latin America by the United States prompted his involvement in Guatemala's social reforms under President Jacobo Árbenz, whose eventual CIA-assisted overthrow at the behest of the United Fruit Company solidified Guevara's political ideology.[7] Later in Mexico City, Guevara met Raúl and Fidel Castro, joined their 26th of July Movement, and sailed to Cuba aboard the yacht Granma with the intention of overthrowing US-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista.[9] Guevara soon rose to prominence among the insurgents, was promoted to second-in-command, and played a pivotal role in the two-year guerrilla campaign which deposed the Batista regime.[10] After the Cuban Revolution, Guevara played key roles in the new government. These included reviewing the appeals and death sentences for those convicted as war criminals during the revolutionary tribunals,[11] instituting agrarian land reform as minister of industries, helping spearhead a successful nationwide literacy campaign, serving as both president of the National Bank and instructional director for Cuba's armed forces, and traversing the globe as a diplomat on behalf of Cuban socialism. Such positions also allowed him to play a central role in training the militia forces who repelled the Bay of Pigs Invasion,[12] and bringing Soviet nuclear-armed ballistic missiles to Cuba, a decision which ultimately precipitated the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.[13] Additionally, Guevara was a prolific writer and diarist, composing a seminal guerrilla warfare manual, along with a best-selling memoir about his youthful continental motorcycle journey. His experiences and studying of Marxism–Leninism led him to posit that the Third World's underdevelopment and dependence was an intrinsic result of imperialism, neocolonialism, and monopoly capitalism, with the only remedies being proletarian internationalism and world revolution.[14][15] Guevara left Cuba in 1965 to foment continental revolutions across both Africa and South America,[16] first unsuccessfully in Congo-Kinshasa and later in Bolivia, where he was captured by CIA-assisted Bolivian forces and summarily executed.[17] Guevara remains both a revered and reviled historical figure, polarized in the collective imagination in a multitude of biographies, memoirs, essays, documentaries, songs, and films. As a result of his perceived martyrdom, poetic invocations for class struggle, and desire to create the consciousness of a "new man" driven by moral rather than material incentives,[18] Guevara has evolved into a quintessential icon of various leftist movements. In contrast, his critics on the political right accuse him of promoting authoritarianism and endorsing violence against his political opponents. Despite disagreements on his legacy, Time named him one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century,[19] while an Alberto Korda photograph of him, titled Guerrillero Heroico, was cited by the Maryland Institute College of Art as "the most famous photograph in the world".[20] |

エルネスト・チェ・ゲバラ[チェはニックネーム](1928年5月14

日 -

1967年10月9日)は、アルゼンチンのマルクス主義革命家、医師、作家、ゲリラ指導者、外交官、政治家、軍事理論家。キューバ革命の主要人物であり、

その様式化された肖像は、反文化の象徴として、また大衆文化における世界的なシンボルとして広く知られている。[6] 若い医学生だったゲバラは、南米を旅し、そこで目にした貧困、飢餓、病気の現実に衝撃を受けた。[7][8] 彼が目にしたアメリカ合衆国によるラテンアメリカへの資本主義的搾取を覆すための援助への強い願望が、ゲバラをグアテマラの社会改革に参画させるきっかけ となった。この改革は、ジャコボ・アルベンス大統領の下で行われたが、最終的にアメリカ合衆国中央情報局(CIA)の支援を受けたユナイテッド・フルー ツ・カンパニーの要請によりアルベンス政権が転覆されたことで、ゲバラの政治思想が固まった。[7] その後、メキシコシティでラウル・カストロとフィデル・カストロと出会い、彼らの「7月26日運動」に参加し、米国が支援する独裁者フルヘンシオ・バティ スタを転覆させる目的で、ヨット「グランマ」に乗ってキューバに渡った。[9] ゲバラはすぐに反乱軍の中で頭角を現し、副司令官に昇進し、2年にわたるゲリラ戦において、バティスタ政権を転覆させる上で重要な役割を果たした。 [10] キューバ革命後、ゲバラは新政府で重要な役割を果たした。その中には、革命裁判で戦争犯罪者として有罪判決を受けた者たちの控訴と死刑判決の見直し [11]、産業大臣として農業土地改革の実施、全国的な識字運動の成功の指揮、国立銀行総裁およびキューバ軍教育担当長官の職務、キューバ社会主義の外交 官として世界中を飛び回る活動などが含まれる。これらの役職を通じて、彼はピッグス湾侵攻を撃退した民兵部隊の訓練[12]や、ソ連の核搭載弾道ミサイル のキューバ配備を推進する役割を果たした。この決定は、1962年のキューバミサイル危機を招くことになった。[13] ゲバラは多作な作家兼日記作家でもあり、ゲリラ戦術の古典的なマニュアルを執筆し、若き日の大陸横断モーターサイクル旅行のベストセラー回顧録も残した。 マルクス・レーニン主義の研究を通じて、彼は第三世界の後進性と依存は帝国主義、新植民地主義、独占資本主義の必然的な結果であり、唯一の解決策はプロレ タリア国際主義と世界革命であると主張した。[14][15] グエバラは1965年にキューバを離れ、アフリカと南米で大陸規模の革命を扇動した[16]。まずコンゴ・キンシャサで失敗し、その後ボリビアでCIAの 支援を受けたボリビア軍に捕らえられ、即決処刑された[17]。 ゲバラは、数多くの伝記、回顧録、エッセイ、ドキュメンタリー、歌、映画などで、集団的想像力の中で二極化され、尊敬と非難の両方を浴びる歴史上の人物と して今なお残っています。彼の殉教とみなされる死、階級闘争を唱える詩的な呼びかけ、物質的な動機ではなく道徳的な動機によって「新しい人間」の意識を創 造したいという願望[18] の結果、ゲバラはさまざまな左翼運動の象徴的な人物へと進化しました。一方、政治的な右派は、ゲバラを権威主義を助長し、政敵に対する暴力を容認した人物 だと非難している。彼の遺産については意見が分かれているが、タイム誌はゲバラを 20 世紀の最も影響力のある 100 人の 1 人に選び[19]、アルベルト・コルダが撮影したゲバラの写真「ゲリレロ・エロイコ」は、メリーランド芸術大学から「世界で最も有名な写真」に選ばれた [20]。 |

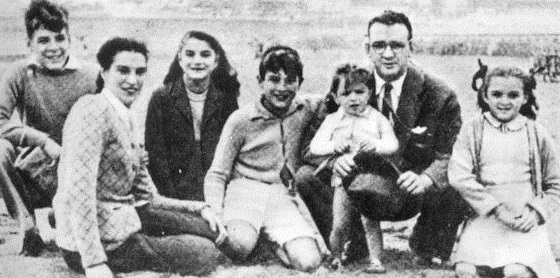

Early life A teenage Ernesto (left) with his parents and siblings, c. 1944, seated beside him from left to right: Celia (mother), Celia (sister), Roberto, Juan Martín, Ernesto (father) and Ana María Ernesto Guevara was born to Ernesto Guevara Lynch and Celia de la Serna y Llosa, on 14 May 1928,[a] in Rosario, Argentina. Although the legal name on his birth certificate was "Ernesto Guevara", his name sometimes appears with "de la Serna" or "Lynch" accompanying it.[21] He was the eldest of five children in an upper-class Argentine family of pre-independence immigrants that have Spanish, Basque, and Irish ancestry.[22][23][c] Two of Guevara's notable 18th-century ancestors included Luis María Peralta, a prominent Spanish landowner in colonial California, and Patrick Lynch, who emigrated from Ireland to the Río de la Plata Governorate.[24][25] Referring to Che's "restless" nature, his father declared "the first thing to note is that in my son's veins flowed the blood of the Irish rebels".[26] Che Guevara was fond of Ireland, and according to Irish actress Maureen O'Hara, "Che would talk about Ireland and all the guerilla warfare that had taken place there. He knew every battle in Ireland and all of its history" and told her that everything he knew about Ireland he learned on his grandmother's knee.[27] Early on in life, Ernestito (as he was then called) developed an "affinity for the poor".[28] Growing up in a family with leftist leanings, Guevara was introduced to a wide spectrum of political perspectives even as a boy.[29] His father, a staunch supporter of Republicans from the Spanish Civil War, would host veterans from the conflict in the Guevara home.[30] As a young man, he briefly contemplated a career selling insecticides, and set up a laboratory in his family's garage to experiment with effective mixtures of talc and gammaxene under the brand name Vendaval, but was forced to abandon his efforts after suffering a severe asthmatic reaction to the chemicals.[31] Despite numerous bouts of acute asthma that were to affect him throughout his life, he excelled as an athlete, enjoying swimming, football, golf, and shooting, while also becoming an "untiring" cyclist.[32][33] He was an avid rugby union player.[34] Several sources say he first played for Estudiantes of Córdoba, then San Isidro Club (1947), Yporá Rugby Club (1948), and Atalaya Polo Club (1949),[35][36][37] although other sources claim he played for Club Universitario de Buenos Aires (CUBA),[38] at fly-half. His rugby playing earned him the nickname "Fuser"—a contraction of El Furibundo (furious) and his mother's surname, de la Serna—for his aggressive style of play.[39] |

幼年時代 1944年頃、両親と兄弟たちと一緒に写る10代のエルネスト(左)。左から右へ、セリア(母)、セリア(姉)、ロベルト、フアン・マルティン、エルネスト(父)、アナ・マリア。 エルネスト・ゲバラは、1928年5月14日、アルゼンチンのロサリオで、エルネスト・ゲバラ・リンチとセリア・デ・ラ・セルナ・イ・ロサの間に生まれ た。出生証明書上の正式な名前は「エルネスト・ゲバラ」だったが、名前には「デ・ラ・セルナ」または「リンチ」が付くこともある。[21] 彼は、スペイン、バスク、アイルランド系の祖先を持つ、独立前の移民のアルゼンチン人上流階級の家庭で5人兄弟の長男として生まれた。[22][23] [c] グエラの18世紀の著名な先祖には、植民地時代のカリフォルニアで著名なスペインの土地所有者であったルイス・マリア・ペラルタと、アイルランドからリ オ・デ・ラ・プラタ総督府に移住したパトリック・リンチが含まれる。[24][25] チェの「落ち着きのない」性格について、彼の父親は「まず最初に指摘すべきは、私の息子の血管にはアイルランドの反乱軍の血が流れていることだ」と述べ た。[26] チェ・ゲバラはアイルランドを愛し、アイルランドの女優モーリーン・オハラによると、「チェはアイルランドとそこで行われたゲリラ戦争についてよく話し た。彼はアイルランドのすべての戦いと歴史を知っていた」と語り、アイルランドについて知っていることはすべて祖母の膝の上で学んだと彼女に話した。 [27] 幼少期から、エルネスト(当時の名前)は「貧しい人々への親近感」を育んだ。[28] 左派傾向のある家庭で育ったゲバラは、少年時代から幅広い政治的見解に触れた。[29] スペイン内戦では共和派を熱烈に支持していた父親は、ゲバラの家に内戦退役軍人を宿泊させていた[30]。若い頃、彼は殺虫剤の販売職を短期間検討し、家 族のガレージに実験室を設立して、タルクとガンマキセンの有効な混合物を「ベンダバル」という商品名で開発したが、化学物質による重度の喘息発作に悩まさ れ、その努力を断念せざるを得なかった。[31] 生涯にわたって何度も急性喘息の発作に悩まされたにもかかわらず、彼は水泳、サッカー、ゴルフ、射撃などのスポーツに秀で、また「疲れ知らずの」サイクリ ストとしても知られていた。[32][33] 彼は熱心なラグビーユニオン選手だった。[34] いくつかの情報源によると、彼は最初にコルドバのエストゥディアンテスでプレーし、その後、サン・イシドロ・クラブ(1947年)、イポラ・ラグビー・ク ラブ(1948年)、アタラヤ・ポロ・クラブ(1949年)でプレーした。[35][36][37] 他の資料では、ブエノスアイレス大学クラブ(CUBA)でフライハーフとしてプレーしたとされている。[38] ラグビーでのプレーから、彼の攻撃的なプレイスタイルから「フサー」というニックネームが付けられた。これは「エル・フリブンド(激しい)」と母親の姓 「デ・ラ・セルナ」を組み合わせたもの。[39] |

| Intellectual and literary interests Guevara learned chess from his father and began participating in local tournaments by the age of 12. During adolescence and throughout his life, he was passionate about poetry, especially that of Pablo Neruda, John Keats, Antonio Machado, Federico García Lorca, Gabriela Mistral, César Vallejo, and Walt Whitman.[40] He could also recite Rudyard Kipling's If— and José Hernández's Martín Fierro by heart.[40] The Guevara home contained more than 3,000 books, which allowed Guevara to be an enthusiastic and eclectic reader, with interests including Karl Marx, William Faulkner, André Gide, Emilio Salgari, and Jules Verne.[41] Additionally, he enjoyed the works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Franz Kafka, Albert Camus, Vladimir Lenin, and Jean-Paul Sartre, as well as Anatole France, Friedrich Engels, H. G. Wells, and Robert Frost.[42] As he grew older, he developed an interest in the Latin American writers Horacio Quiroga, Ciro Alegría, Jorge Icaza, Rubén Darío, and Miguel Asturias.[42] Many of these authors' ideas he cataloged in his own handwritten notebooks of concepts, definitions, and philosophies of influential intellectuals. These included composing analytical sketches of Buddha and Aristotle, along with examining Bertrand Russell on love and patriotism, Jack London on society, and Nietzsche on the idea of death. Sigmund Freud's ideas fascinated him as he quoted him on a variety of topics from dreams and libido to narcissism and the Oedipus complex.[42] His favorite subjects in school included philosophy, mathematics, engineering, political science, sociology, history, and archaeology.[43][44] A CIA "biographical and personality report", dated 13 February 1958 and declassified decades later, made note of Guevara's range of academic interests and intellect – describing him as "quite well read", while adding that "Che is fairly intellectual for a Latino".[45] |

知的・文学的関心 ゲバラは父親からチェスを学び、12歳の頃から地元のトーナメントに出場し始めた。青年期から生涯を通じて、彼は詩、特にパブロ・ネルーダ、ジョン・キー ツ、アントニオ・マチャド、フェデリコ・ガルシア・ロルカ、ガブリエラ・ミストラル、セサル・ヴァレーホ、ウォルト・ホイットマンの詩に情熱を注いだ。 [40] また、ラドヤード・キップリングの『もし』とホセ・エルナンデスの『マルティン・フィエロ』を暗唱することもできた。[40] グエバラの自宅には3,000冊以上の本があり、グエバラはカール・マルクス、ウィリアム・フォークナー、アンドレ・ジッド、エミリオ・サルガリ、ジュー ル・ヴェルヌなど、幅広い分野に熱心な読書家だった。[41] さらに、ジャワハルラール・ネルー、フランツ・カフカ、アルベール・カミュ、ウラジーミル・レーニン、ジャン=ポール・サルトル、アナトール・フランス、 フリードリヒ・エンゲルス、H. G. ウェルズ、ロバート・フロストなどの作品も好んだ。[42] 年を重ねるにつれて、彼はラテンアメリカの作家、オラシオ・キロガ、シロ・アレグリア、ホルヘ・イカサ、ルベン・ダリオ、ミゲル・アストゥリアスに興味を 持つようになった。[42] これらの作家の考えの多くは、影響力のある知識人の概念、定義、哲学を自分の手書きのノートにまとめました。その中には、仏陀やアリストテレスの分析的ス ケッチ、バートランド・ラッセルによる愛と愛国心、ジャック・ロンドンによる社会、ニーチェによる死の概念についての考察などが含まれていた。彼は、夢や 性欲からナルシシズム、エディプスコンプレックスに至るまで、さまざまなトピックについて引用しながら、ジークムント・フロイトの思想に魅了されていた [42]。学校での好きな科目には、哲学、数学、工学、政治学、社会学、歴史、考古学があった。[43][44] 1958年2月13日付のCIAの「経歴および性格報告書」は、数十年後に機密解除され、ゲバラの幅広い学問的関心と知性を指摘し、彼を「かなり博識」と 評し、「ラテン系としてはかなり知的な人物」と付け加えている。[45] |

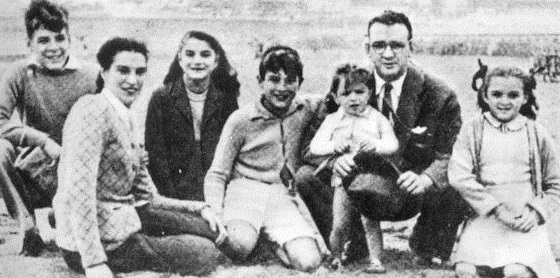

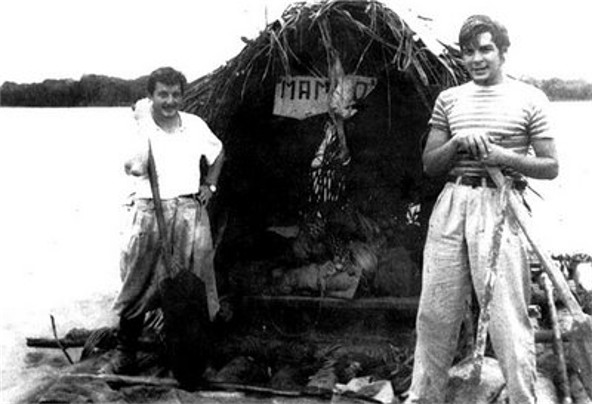

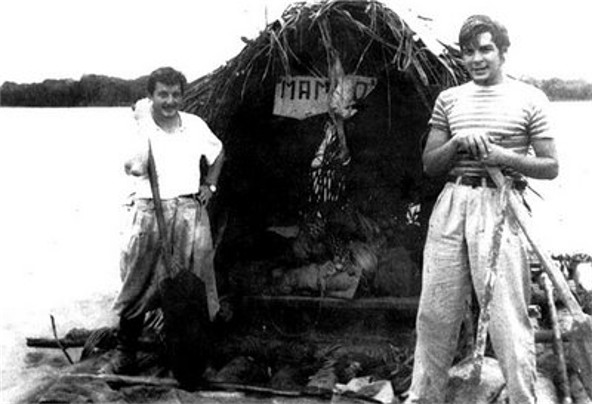

| Motorcycle journey Main article: The Motorcycle Diaries (book)  black and white photograph of two men on a raft, fitted with a large hut. The far bank of the river is visible in the far distance Guevara (right) with Alberto Granado (left) in June 1952 on the Amazon River aboard their "Mambo-Tango" wooden raft, which was a gift from the lepers whom they had treated[46] In 1948, Guevara entered the University of Buenos Aires to study medicine. His "hunger to explore the world"[47] led him to intersperse his collegiate pursuits with two long introspective journeys that fundamentally changed the way he viewed himself and the contemporary economic conditions in Latin America. The first expedition, in 1950, was a 4,500-kilometer (2,800 mi) solo trip through the rural provinces of northern Argentina on a bicycle on which he had installed a small engine.[48] Guevara then spent six months working as a nurse at sea on Argentina's merchant marine freighters and oil tankers.[49] His second expedition, in 1951, was a nine-month, 8,000-kilometer (5,000 mi) continental motorcycle trek through part of South America. For the latter, he took a year off from his studies to embark with his friend, Alberto Granado, with the final goal of spending a few weeks volunteering at the San Pablo leper colony in Peru, on the banks of the Amazon River.[50]  A map of Guevara's 1952 trip with Alberto Granado (The red arrows correspond to air travel.) In Chile, Guevara was angered by the working conditions of the miners at Anaconda's Chuquicamata copper mine, moved by his overnight encounter in the Atacama Desert with a persecuted communist couple who did not even own a blanket, describing them as "the shivering flesh-and-blood victims of capitalist exploitation".[51] On the way to Machu Picchu he was stunned by the crushing poverty of the remote rural areas, where peasant farmers worked small plots of land owned by wealthy landlords.[52] Later on his journey, Guevara was especially impressed by the camaraderie among the people living in a leper colony, stating, "The highest forms of human solidarity and loyalty arise among such lonely and desperate people."[52] Guevara used notes taken during this trip to write an account (not published until 1995), titled The Motorcycle Diaries, which later became a New York Times best seller,[53] and was adapted into a 2004 film of the same name. A motorcycle journey the length of South America awakened him to the injustice of US domination in the hemisphere, and to the suffering colonialism brought to its original inhabitants. —George Galloway, British politician, 2006[54] The journey took Guevara through Argentina, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, and Miami, Florida, for 20 days,[55] before returning home to Buenos Aires. By the end of the trip, he came to view Latin America not as a collection of separate nations, but as a single entity requiring a continent-wide liberation strategy. His conception of a borderless, united Hispanic America sharing a common Latino heritage was a theme that recurred prominently during his later revolutionary activities. Upon returning to Argentina, he completed his studies and received his medical degree in June 1953.[56][57] Guevara later remarked that, through his travels in Latin America, he came in "close contact with poverty, hunger and disease" along with the "inability to treat a child because of lack of money" and "stupefaction provoked by the continual hunger and punishment" that leads a father to "accept the loss of a son as an unimportant accident". Guevara cited these experiences as convincing him that to "help these people", he needed to leave the realm of medicine and consider the political arena of armed struggle.[7] |

オートバイの旅 主な記事:オートバイ日記(書籍)  2人の男性が大きな小屋を付けた筏に乗っている白黒写真。遠くには川の対岸が見える 1952年6月、アマゾン川で「マンボ・タンゴ」と名付けた木製の筏に乗ったゲバラ(右)とアルベルト・グラナド(左)。この筏は、彼らが治療したハンセン病患者たちから贈られたものだった[46] 1948年、ゲバラはブエノスアイレス大学に入学し、医学を学んだ。彼の「世界を探求したいという渇望」[47]は、大学での学業と並行して、2度の長い 内省的な旅を挟むことになり、これが彼自身とラテンアメリカにおける当時の経済状況に対する見方を根本から変えることになった。最初の旅は1950年で、 アルゼンチン北部の農村地帯を自転車に小型エンジンを装着して4,500キロメートル(2,800マイル)を単独で走破した。[48] ゲバラはその後、アルゼンチンの商船の貨物船と石油タンカーで6ヶ月間、看護師として働いた。[49] 1951年の2度目の探検は、南米の一部を横断する9ヶ月間、8,000キロメートル(5,000マイル)のモーターサイクルの旅だった。この旅のため、 彼は学業を1年間休学し、友人アルベルト・グラナドと共に、ペルーのアマゾン川沿いにあるサン・パブロのハンセン病コロニーで数週間ボランティア活動を行 うことを最終目標として出発した。[50]  1952年にアルベルト・グラナドと行った旅の地図(赤い矢印は航空路)。 チリでは、アナコンダ社のチュキカマタ銅山で働く鉱夫たちの労働条件に怒りを覚えた。アタカマ砂漠で、毛布一つ持たない迫害された共産党員夫婦と一夜を共 に過ごし、彼らを「資本主義的搾取の震える生身の人間」と表現した。[51] マチュピチュに向かう途中、彼は、貧しい農民たちが裕福な地主が所有する小さな農地を耕作している、辺鄙な農村部の極度の貧困に衝撃を受けた[52]。旅 の途中、ゲバラは、ハンセン病の患者たちが暮らすコロニーで、彼ら間の仲間意識に特に感銘を受け、「このような孤独で絶望的な人々の中に、人間としての連 帯と忠誠の最高形態が生まれる」と述べた。[52] ゲバラはこの旅で取ったメモを基に、1995年に初めて出版された『モーターサイクル・ダイアリーズ』という著作を執筆した。この作品はのちにニューヨー ク・タイムズのベストセラーとなり、2004年に同名の映画化もされた。 南米を縦断するオートバイの旅は、この半球における米国の支配の不正と、その先住民たちに与えた植民地主義の苦悩に彼の目を覚まさせた。 —ジョージ・ギャロウェイ、英国の政治家、2006年[54] この旅は、ゲバラをアルゼンチン、チリ、ペルー、エクアドル、コロンビア、ベネズエラ、パナマ、そしてフロリダ州マイアミへと20日間かけて導き [55]、その後彼はブエノスアイレスの自宅に戻った。旅の終わりには、彼はラテンアメリカを別々の国民が集合した集合体ではなく、大陸全体の解放戦略を 必要とする単一の団体として捉えるようになった。共通のラテンアメリカの遺産を共有する、国境のない統一されたヒスパニック系アメリカという彼の構想は、 その後の革命活動において繰り返し登場するテーマとなった。アルゼンチンに戻った彼は、学業を修了し、1953年6月に医学の学位を取得した[56]。 [57] ゲバラは後に、ラテンアメリカを旅して、「貧困、飢餓、病気」に直面し、「お金がないために子供たちを治療できない」状況や、「絶え間ない飢餓と罰によっ て引き起こされる麻痺状態」が父親たちに「息子の死を些細な事故として受け入れる」ように仕向けることを知ったと語っている。ゲバラは、これらの経験か ら、「これらの人々を助ける」ためには、医学の分野を離れ、武力闘争という政治の分野に目を向ける必要があると確信したと述べている[7]。 |

| Early political activity Activism in Guatemala Main article: 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état Ernesto Guevara spent just over nine months in Guatemala. On 7 July 1953, Guevara set out again, this time to Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, and El Salvador. On 10 December 1953, before leaving for Guatemala, Guevara sent an update to his aunt Beatriz from San José, Costa Rica. In the letter Guevara speaks of traversing the dominion of the United Fruit Company, a journey which convinced him that the company's capitalist system was disadvantageous to the average citizen.[58] He adopted an aggressive tone to frighten his more conservative relatives, and the letter ends with Guevara swearing on an image of the then-recently deceased Joseph Stalin, not to rest until these "octopuses have been vanquished".[59] Later that month, Guevara arrived in Guatemala, where President Jacobo Árbenz headed a democratically elected government that, through land reform and other initiatives, was attempting to end the latifundia agricultural system. To accomplish this, President Árbenz had enacted a major land reform program, where all uncultivated portions of large land holdings were to be appropriated and redistributed to landless peasants. The largest land owner, and the one most affected by the reforms, was the United Fruit Company, from which the Árbenz government had already taken more than 225,000 acres (91,000 ha) of uncultivated land.[60] Pleased with the direction in which the nation was heading, Guevara decided to make his home in Guatemala to "perfect himself and accomplish whatever may be necessary in order to become a true revolutionary".[60][61]  A map of Che Guevara's travels between 1953 and 1956, including his journey aboard the Granma In Guatemala City, Guevara sought out Hilda Gadea Acosta, a Peruvian economist who was politically well-connected as a member of the left-leaning, Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana (APRA). She introduced Guevara to a number of high-level officials in the Árbenz government. Guevara then established contact with a group of Cuban exiles linked to Fidel Castro through the 26 July 1953 attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba. During this period, he acquired his famous nickname, due to his frequent use of the Argentine filler expression che (a multi-purpose discourse marker, like the syllable "eh" in Canadian English).[62] During his time in Guatemala, Guevara was hosted by other Central American exiles, one of whom, Helena Leiva de Holst, provided him with food and lodging,[63] discussed her travels to study Marxism in Russia and China,[64] and to whom Guevara dedicated a poem, "Invitación al camino".[65] In May 1954, a ship carrying infantry and light artillery weapons was dispatched by communist Czechoslovakia for the Árbenz government and arrived in Puerto Barrios.[66] As a result, the United States government—which since 1953 had been tasked by President Eisenhower to remove Árbenz from power in the multifaceted CIA operation code-named PBSuccess—responded by saturating Guatemala with anti-Árbenz propaganda through radio and air-dropped leaflets, and began bombing raids using unmarked airplanes.[67] The United States also sponsored an armed force of several hundred anti-Árbenz Guatemalan refugees and mercenaries headed by Carlos Castillo Armas to help remove the Árbenz government. On 27 June, Árbenz chose to resign.[68] This allowed Armas and his CIA-assisted forces to march into Guatemala City and establish a military junta, which elected Armas as president on 7 July.[69] The Armas regime then consolidated power by rounding up and executing suspected communists,[70] while crushing the previously flourishing labor unions[71] and reversing the previous agrarian reforms.[72] Guevara was eager to fight on behalf of Árbenz, and joined an armed militia organized by the communist youth for that purpose. However, frustrated with that group's inaction, Guevara soon returned to medical duties. Following the coup, he again volunteered to fight, but soon after, Árbenz took refuge in the Mexican embassy and told his foreign supporters to leave the country. Guevara's repeated calls to resist were noted by supporters of the coup, and he was marked for murder.[73] After Gadea was arrested, Guevara sought protection inside the Argentine consulate, where he remained until he received a safe-conduct pass some weeks later and made his way to Mexico.[74] The overthrow of the Árbenz government and establishment of the right-wing Armas dictatorship cemented Guevara's view of the United States as an imperialist power that opposed and attempted to destroy any government that sought to redress the socioeconomic inequality endemic to Latin America and other developing countries.[60] In speaking about the coup, Guevara stated: The last Latin American revolutionary democracy – that of Jacobo Árbenz – failed as a result of the cold premeditated aggression carried out by the United States. Its visible head was the Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, a man who, through a rare coincidence, was also a stockholder and attorney for the United Fruit Company.[73] Guevara's conviction strengthened that Marxism, achieved through armed struggle and defended by an armed populace, was the only way to rectify such conditions.[75] Gadea wrote later, "It was Guatemala which finally convinced him of the necessity for armed struggle and for taking the initiative against imperialism. By the time he left, he was sure of this."[76] |

初期の政治活動 グアテマラでの活動 主な記事:1954年のグアテマラのクーデター エルネスト・ゲバラはグアテマラに9ヶ月余りを過ごした。1953年7月7日、ゲバラは再び出発し、今回はボリビア、ペルー、エクアドル、パナマ、コスタ リカ、ニカラグア、ホンジュラス、エルサルバドルへ向かった。1953年12月10日、グアテマラへ向かう前に、ゲバラはコスタリカのサンホセから叔母の ベアトリスに近況報告を送った。その手紙でゲバラは、ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーの支配下にある地域を traversing した経験について述べ、その旅が同社の資本主義システムが一般市民に不利であることを確信させたと言及している。[58] 彼は保守的な親戚を脅かすために攻撃的なトーンを採用し、手紙は「これらの『タコ』が打ち倒されるまで休まない」と、当時最近死去したヨシフ・スターリン の肖像画に誓う言葉で結ばれている。[59] その月の後半、ゲバラはグアテマラに到着した。同国では、ジャコボ・アルベンス大統領が民主的に選出された政府を率い、土地改革をはじめとする措置を通じ て、大土地所有制(ラティフンディア)を廃止しようとしていた。この目的のため、アルベンス大統領は主要な土地改革プログラムを実施し、大規模な土地所有 者の未開墾地を没収し、土地を持たない農民に再分配する方針を打ち出した。最大の土地所有者であり、改革で最も影響を受けたのはユナイテッド・フルーツ・ カンパニーで、アルベンツ政権は既に同社から22万5,000エーカー(9万1,000ヘクタール)の未開墾地を接収していた。[60] 国の進む方向性に満足したゲバラは、グアテマラに定住し、「自分自身を完成させ、真の革命家になるために必要なことをすべて達成する」ことを決意した。 [60][61]  1953年から1956年にかけてのチェ・ゲバラの旅行ルート。グランマ号での航海も含まれる。 グアテマラシティで、ゲバラはペルーの経済学者で、左派の「アメリカ人民革命同盟」(APRA)のメンバーとして政治的に影響力のあるヒルダ・ガデア・ア コスタと出会った。彼女はゲバラをアルベンツ政権の高官たちに紹介した。その後、ゲバラは、1953年7月26日にサンティアゴ・デ・クーバのモンカダ兵 舎を襲撃した事件に関わった、フィデル・カストロと関係のあるキューバ亡命者たちとの接触を確立した。この期間、彼は、アルゼンチンでよく使われる間投詞 「チェ」(カナダ英語での「え」のような、さまざまな意味を持つ言説のマーカー)を頻繁に使用していたことから、その有名なニックネームを授けられた。 [62] グアテマラ滞在中、ゲバラは他の中央アメリカ亡命者たちから支援を受け、その一人であるヘレナ・レイバ・デ・ホルストからは食料と住居を提供された [63]。彼女はロシアと中国でマルクス主義を学ぶための旅について語り[64]、ゲバラは彼女に詩「Invitación al camino」を捧げた。[65] 1954年5月、共産主義のチェコスロバキアは、アルベンツ政権のために歩兵と軽砲兵の武器を積んだ船を派遣し、プエルト・バリオスに到着した。[66] これに対し、1953年からアイゼンハワー大統領の指示で、CIAの多面的な作戦「PBSuccess」を通じてアーベンツ政権の打倒を任務としていたア メリカ政府は、ラジオや空から散布されたビラを通じて反アーベンツ宣伝をグアテマラ全土に展開し、無標識の航空機による爆撃を開始した。[67] アメリカ合衆国はまた、カルロス・カスティージョ・アルマス率いる数百人の反アルベンツ派グアテマラ難民と傭兵からなる武装勢力を支援し、アルベンツ政権 の打倒を支援した。6月27日、アーベンツは辞任を表明した。[68] これにより、アルマスとCIAの支援を受けた勢力はグアテマラシティに進軍し、軍事政権を樹立。7月7日にアルマスが大統領に選出された。[69] アルマス政権は、共産主義者と疑われる人物を逮捕・処刑し、[70] 以前繁栄していた労働組合を弾圧し、[71] これまでの農業改革を撤回することで権力を固めた。[72] ゲバラはアルベンツのために戦うことを熱望し、その目的のために共産主義の若者たちによって組織された武装民兵に加わった。しかし、そのグループの無為無 策に不満を抱いたゲバラは、すぐに医療業務に戻った。クーデター後、彼は再び戦闘に参加することを志願したが、その直後、アルベンツはメキシコ大使館に避 難し、外国の支援者たちに国を離れるよう指示した。ゲバラの抵抗を呼びかける繰り返しの呼びかけはクーデター支持者に注目され、彼は暗殺対象に指定された [73]。ガデアが逮捕されると、ゲバラはアルゼンチン領事館内に保護を求め、数週間後に安全通行証を取得するまでそこに留まり、その後メキシコへ移動し た。[74] アルベンツ政権の打倒と、右翼のアルマス独裁政権の樹立は、ゲバラの、米国はラテンアメリカやその他の発展途上国に蔓延する社会経済的不平等を是正しよう とするあらゆる政権に反対し、その破壊を試みる帝国主義大国であるという見解を固めた。[60] クーデターについて、ゲバラは次のように述べている。 ラテンアメリカ最後の革命的民主主義政権——ヤコボ・アルベンツ政権——は、アメリカ合衆国によって計画的に実行された冷酷な侵略により崩壊した。その表 向きの首謀者は国務長官ジョン・フォスター・ダレスで、彼は偶然にもユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーの株主兼弁護士でもあった。[73] ゲバラの信念は、武装闘争を通じて達成され、武装した民衆によって守られるマルクス主義が、このような状況を是正する唯一の道であるとの考えを強めた。 [75] ガデアは後に、「彼に武装闘争の必要性と帝国主義に対して主導権を握る必要性を確信させたのは、結局グアテマラだった。彼がグアテマラを去る頃には、彼は それを確信していた」と書いている。[76] |

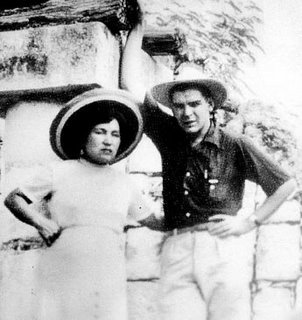

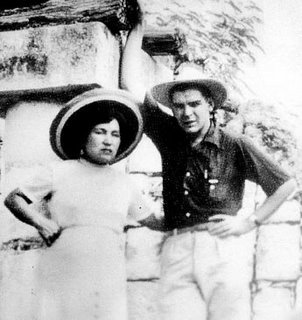

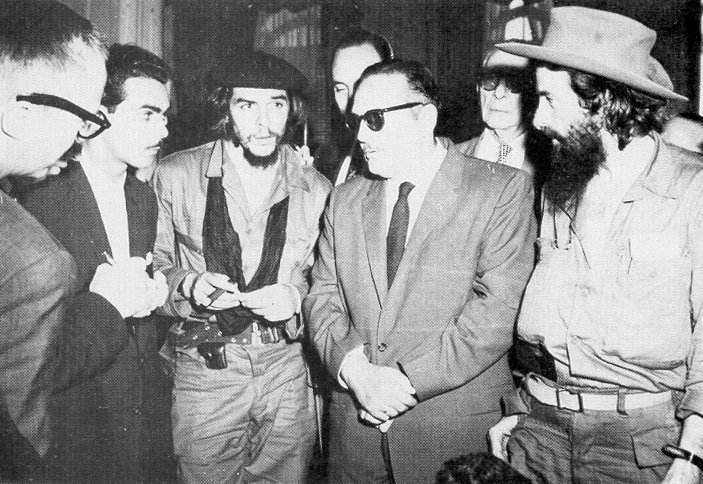

Exile in Mexico Guevara with his first wife Hilda Gadea at Chichen Itza during their honeymoon trip Guevara arrived in Mexico City on 21 September 1954, and worked in the allergy section of the General Hospital and at the Hospital Infantil de Mexico.[77][78] In addition he gave lectures on medicine at the Faculty of Medicine in the National Autonomous University of Mexico and worked as a news photographer for Latina News Agency.[79][80] His first wife Hilda notes in her memoir My Life with Che, that for a while, Guevara considered going to work as a doctor in Africa and that he continued to be deeply troubled by the poverty around him.[81] In one instance, Hilda describes Guevara's obsession with an elderly washerwoman whom he was treating, remarking that he saw her as "representative of the most forgotten and exploited class". Hilda later found a poem that Che had dedicated to the old woman, containing "a promise to fight for a better world, for a better life for all the poor and exploited".[81] During this time he renewed his friendship with Ñico López and the other Cuban exiles whom he had met in Guatemala. In June 1955, López introduced him to Raúl Castro, who subsequently introduced him to his older brother, Fidel Castro, the revolutionary leader who had formed the 26th of July Movement and was now plotting to overthrow the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. During a long conversation with Fidel on the night of their first meeting, Guevara concluded that the Cuban's cause was the one for which he had been searching and before daybreak he had signed up as a member of 26 July Movement.[82] Despite their "contrasting personalities", from this point on Che and Fidel began to foster what dual biographer Simon Reid-Henry deemed a "revolutionary friendship that would change the world" as a result of their coinciding commitment to anti-imperialism.[83] By this point in Guevara's life, he deemed that US-controlled conglomerates had installed and supported repressive regimes around the world. In this vein, he considered Batista a "U.S. puppet whose strings needed cutting".[84] Although he planned to be the group's combat medic, Guevara participated in the military training with the members of the Movement. The key portion of training involved learning hit and run tactics of guerrilla warfare. Guevara and the others underwent arduous 15-hour marches over mountains, across rivers, and through the dense undergrowth, learning and perfecting the procedures of ambush and quick retreat. From the start Guevara was instructor Alberto Bayo's "prize student" among those in training, scoring the highest on all of the tests given.[85] At the end of the course, he was named "the best guerrilla of them all" by General Bayo.[86] Guevara then married Hilda in Mexico in September 1955, before embarking on his plan to assist in the liberation of Cuba.[87] |

メキシコでの亡命 新婚旅行中のチチェン・イッツァで、最初の妻ヒルダ・ガデアとゲバラ ゲバラは1954年9月21日にメキシコシティに到着し、総合病院のアレルギー科とメキシコ小児病院で働いた[77]。[78] さらに、メキシコ国立自治大学医学部で医学の講義を行い、ラティーナ通信社の報道写真家としても働いた。[79][80] 彼の最初の妻ヒルダは回顧録『My Life with Che』の中で、ゲバラはしばらくの間、アフリカで医師として働くことを考え、周囲の貧困に深く悩んでいたと記している。[81] ある時、ヒルダはゲバラが治療していた高齢の洗濯婦への執着を記述し、彼を「最も忘れ去られ、搾取された階級の代表」と見なしていたと述べている。ヒルダ は後に、チェが老婦人に捧げた詩を発見し、その中で「より良い世界、すべての貧しい者や搾取された者のためのより良い生活のために戦う」という誓いが記さ れていた。[81] この間、彼はグアテマラで出会ったニコ・ロペスや他のキューバ亡命者たちとの友情を再び深めた。1955年6月、ロペスは彼をラウル・カストロに紹介し、 ラウルは彼を、7月26日運動を結成し、フルヘンシオ・バティスタの独裁政権の打倒を企てていた革命指導者である兄のフィデル・カストロに紹介した。最初 の出会いの夜、フィデルとの長い会話の末、ゲバラはキューバの闘いが自分が求めていたものだと確信し、夜明け前に7月26日運動のメンバーとして加入し た。[82] 「対照的な性格」にもかかわらず、この時点から、チェとフィデルは、反帝国主義への共通の決意から、2人の伝記作家サイモン・リード・ヘンリーが「世界を 変える革命的な友情」と表現する関係を築き始めた。[83] この時点でゲバラは、米国が支配する大企業が世界中に抑圧的な政権を樹立し、支援していると判断していた。この観点から、彼はバティスタを「米国が操る傀 儡」と見なし、その「糸を切る」必要があると考えた。[84] ゲバラはグループの戦闘衛生兵となる予定だったが、運動のメンバーとともに軍事訓練に参加した。訓練の核心部分は、ゲリラ戦のヒットアンドラン戦術の習得 だった。ゲバラと他のメンバーは、山を越え、川を渡り、密林を駆け抜ける過酷な15時間の行軍を繰り返し、待ち伏せと迅速な撤退の手順を学び、磨き上げ た。訓練開始から、ゲバラは指導者のアルベルト・バヨの「最優秀生徒」として、すべての試験で最高得点を獲得した。[85] コース終了時、ゲバラはバヨ将軍から「最も優秀なゲリラ」と称賛された。[86] ゲバラは1955年9月、メキシコでヒルダと結婚した後、キューバの解放を支援する計画に着手した。[87] |

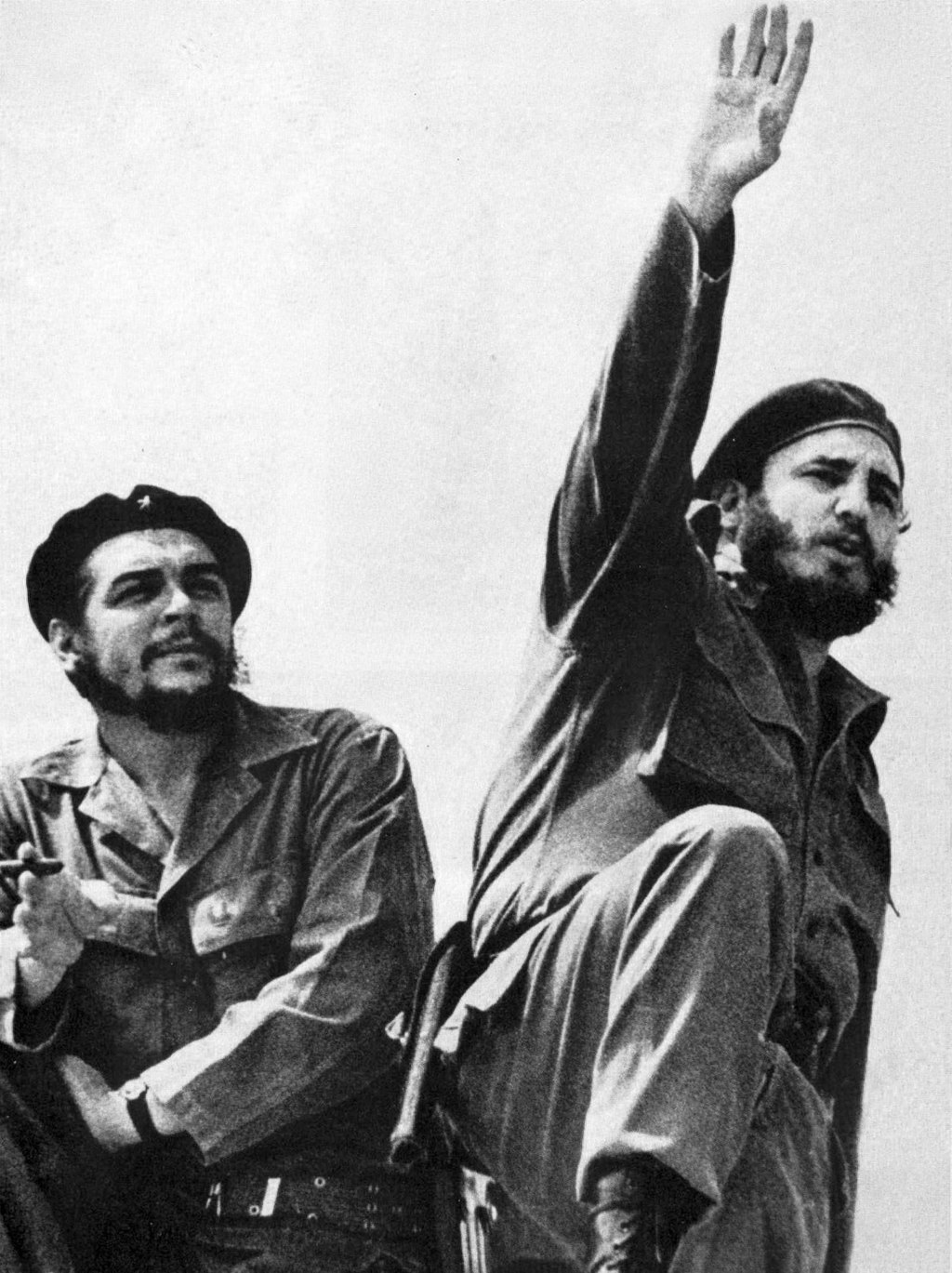

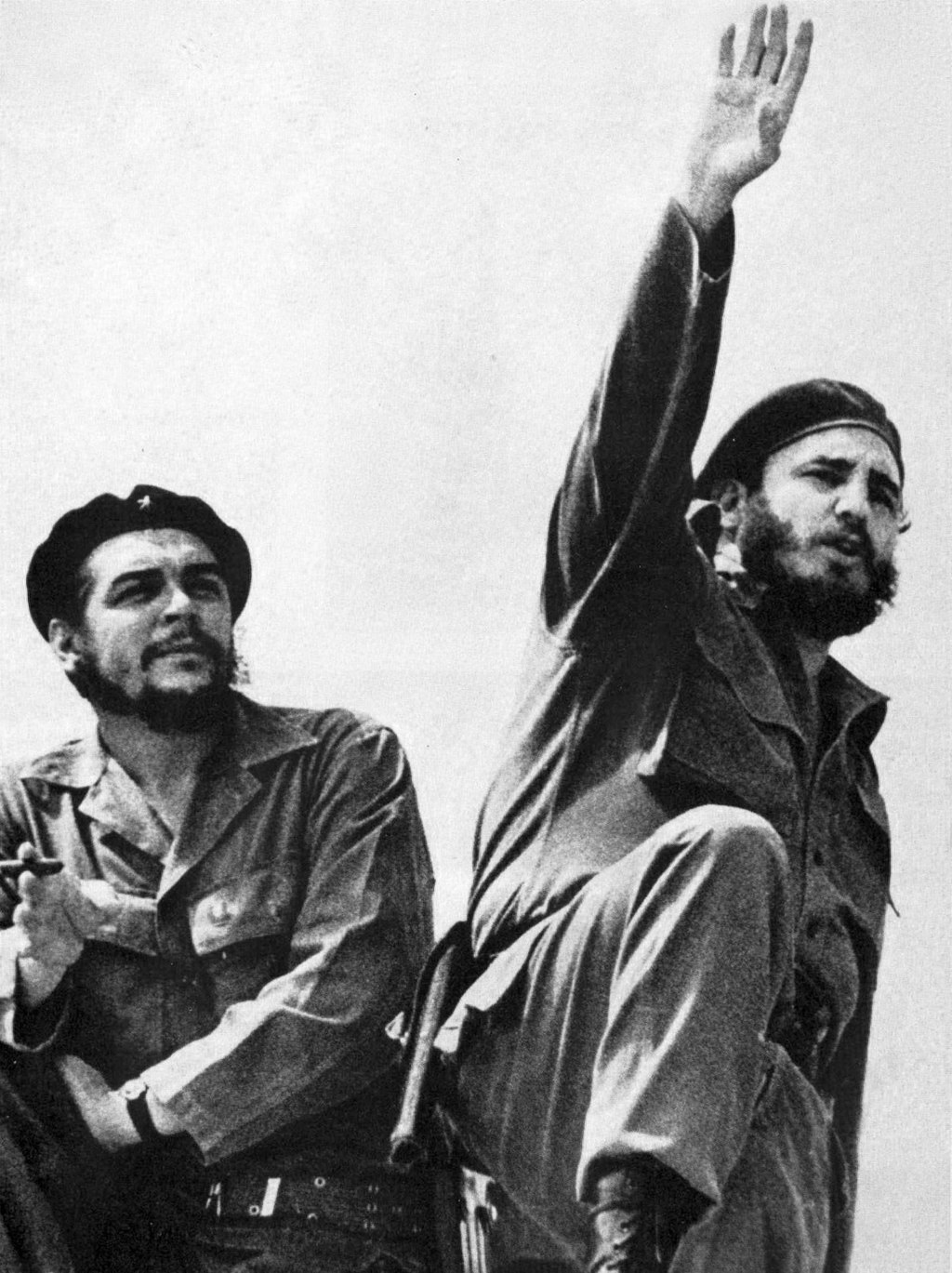

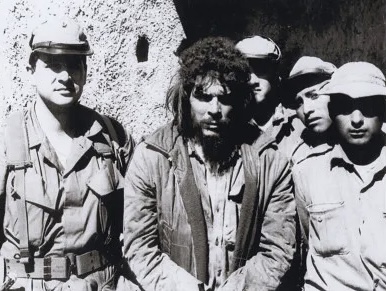

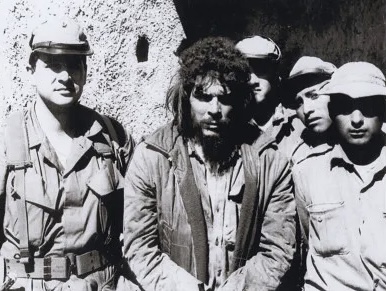

| Cuban Revolution Main article: Cuban Revolution Granma invasion Further information: Landing of the Granma and Battle of Alegría de Pío  Journey of the yacht "Granma", from Mexico to Cuba  Granma survivors in the Sierra Maestra. Fidel Castro stands at center. Che Guevara stands second from left. The first step in Castro's revolutionary plan was an assault on Cuba from Mexico via the Granma, an old, leaky cabin cruiser. They set out for Cuba on 25 November 1956. Attacked by Batista's military soon after landing, many of the 82 men were either killed in the attack or executed upon capture; only 22 found each other afterwards.[88] During this initial bloody confrontation, Guevara laid down his medical supplies and picked up a box of ammunition dropped by a fleeing comrade, proving to be a symbolic moment in Che's life.[89] Only a small band of revolutionaries survived to re-group as a bedraggled fighting force deep in the Sierra Maestra mountains, where they received support from the urban guerrilla network of Frank País, the 26 July Movement, and local campesinos. With the group withdrawn to the Sierra, the world wondered whether Castro was alive or dead until early 1957, when an interview by Herbert Matthews appeared in The New York Times. The article presented a lasting, almost mythical image for Castro and the guerrillas. Guevara was not present for the interview, but in the coming months he began to realize the importance of the media in their struggle. Meanwhile, as supplies and morale diminished, and with an allergy to mosquito bites which resulted in agonizing walnut-sized cysts on his body,[90] Guevara considered these "the most painful days of the war".[91] During Guevara's time living hidden among the poor subsistence farmers of the Sierra Maestra mountains, he discovered that there were no schools, no electricity, minimal access to healthcare, and more than 40 percent of the adults were illiterate.[92] As the war continued, Guevara became an integral part of the rebel army and "convinced Castro with competence, diplomacy and patience".[10] Guevara set up factories to make grenades, built ovens to bake bread, and organized schools to teach illiterate campesinos to read and write.[10] Moreover, Guevara established health clinics, workshops to teach military tactics, and a newspaper to disseminate information.[93] The man whom Time dubbed three years later "Castro's brain" at this point was promoted by Fidel Castro to Comandante (commander) of a second army column.[10] |

キューバ革命 主な記事:キューバ革命 グランマ号侵攻 詳細情報:グランマ号の上陸とアレグリア・デ・ピオの戦い  ヨット「グランマ号」のメキシコからキューバへの航海  シエラ・マエストラのグランマ号生存者たち。中央に立つのがフィデル・カストロ、左から2番目がチェ・ゲバラ。 カストロの革命計画の最初のステップは、古い漏れの多いキャビンクルーザー「グランマ」でメキシコからキューバへの襲撃だった。彼らは1956年11月 25日にキューバに向けて出航した。上陸直後、バティスタの軍隊に攻撃され、82人のうち多くの者が攻撃で死亡または捕虜となり処刑された。その後、22 人だけが再会した。[88] この最初の血なまぐさい戦闘中、ゲバラは医療用品を捨て、逃げる同志が落とした弾薬箱を拾い上げた。これはチェの人生における象徴的な瞬間となった。 [89] ごく少数の革命軍だけが生き残り、シエラ・マエストラ山脈の奥深くで、フランク・パイス、7月26日運動、地元の農民たちによる都市ゲリラネットワークの 支援を受けて、みすぼらしい戦闘部隊として再編成された。グループがシエラに撤退すると、1957年初頭、ハーバート・マシューズによるインタビューが ニューヨーク・タイムズに掲載されるまで、カストロが生きているのか死んでいるのか、世界は疑問に思っていた。この記事は、カストロとゲリラたちにとっ て、永続的でほぼ神話的なイメージを提示した。ゲバラはインタビューには出席しなかったが、その後の数ヶ月で、メディアが彼らの闘争における重要性を認識 し始めた。一方、物資と士気が低下し、蚊の刺咬に対するアレルギーにより、体中にクルミ大の痛みを伴う腫れ物ができた[90] ゲバラは、この期間を「戦争で最も痛ましい日々」と回想している。[91] ゲバラは、シエラ・マエストラ山脈の貧しい自給自足農民たちの間に隠れて暮らしていた頃、学校も電気も、医療もほとんどなく、成人の 40% 以上が無学であることを知った[92]。戦争が続く中、ゲバラは反乱軍の不可欠な一員となり、「その能力、外交手腕、忍耐力によってカストロを納得させ た」[10]。ゲバラは手榴弾を製造する工場を設立し、パンを焼くオーブンを建設し、文盲の農民たちに読み書きを教える学校を組織した[10]。さらに、 保健所、軍事戦術を教えるワークショップ、情報を広める新聞も設立した。[93] 3年後、タイム誌が「カストロの頭脳」と称したこの男は、フィデル・カストロによって第2軍団の司令官(コマンダンテ)に昇進した。[10] |

| Role as commander As second-in-command, Guevara was a harsh disciplinarian who sometimes shot defectors. Deserters were punished as traitors, and Guevara was known to send squads to track those seeking to abandon their duties.[94] As a result, Guevara became feared for his brutality and ruthlessness.[95] During the guerrilla campaign, Guevara was also responsible for the summary executions of a number of men accused of being informers, deserters, or spies.[96] In his diaries, Guevara described the first such execution, of Eutimio Guerra, a peasant who had acted as a guide for the Castrist guerrillas, but admitted treason when it was discovered he accepted the promise of ten thousand pesos for repeatedly giving away the rebels' position for attack by the Cuban air force.[97] Such information also allowed Batista's army to burn the homes of peasants sympathetic to the revolution.[97] Upon Guerra's request that they "end his life quickly",[97] Che stepped forward and shot him in the head, writing "The situation was uncomfortable for the people and for Eutimio so I ended the problem giving him a shot with a .32 pistol in the right side of the brain, with exit orifice in the right temporal [lobe]."[98] His scientific notations and matter-of-fact description suggested to one biographer a "remarkable detachment to violence" by that point in the war.[98] Later, Guevara published a literary account of the incident, titled "Death of a Traitor", where he transfigured Eutimio's betrayal and pre-execution request that the revolution "take care of his children", into a "revolutionary parable about redemption through sacrifice".[98]  Guevara at his guerrilla base in the Escambray Mountains Although he maintained a demanding and harsh disposition, Guevara also viewed his role of commander as one of a teacher, entertaining his men during breaks between engagements with readings from the likes of Robert Louis Stevenson, Miguel de Cervantes, and Spanish lyric poets.[99] Together with this role, and inspired by José Martí's principle of "literacy without borders", Guevara further ensured that his rebel fighters made daily time to teach the uneducated campesinos with whom they lived and fought to read and write, in what Guevara termed the "battle against ignorance".[92] Tomás Alba, who fought under Guevara's command, later stated that "Che was loved, in spite of being stern and demanding. We would (have) given our life for him."[100] His commanding officer, Fidel Castro, described Guevara as intelligent, daring, and an exemplary leader who "had great moral authority over his troops".[101] Castro further remarked that Guevara took too many risks, even having a "tendency toward foolhardiness".[102] Guevara's teenage lieutenant, Joel Iglesias, recounts such actions in his diary, noting that Guevara's behavior in combat even brought admiration from the enemy. On one occasion Iglesias recounts the time he had been wounded in battle, stating "Che ran out to me, defying the bullets, threw me over his shoulder, and got me out of there. The guards didn't dare fire at him ... later they told me he made a great impression on them when they saw him run out with his pistol stuck in his belt, ignoring the danger, they didn't dare shoot."[103] Guevara was instrumental in creating the clandestine radio station Radio Rebelde (Rebel Radio) in February 1958, which broadcast news to the Cuban people with statements by 26 July movement, and provided radiotelephone communication between the growing number of rebel columns across the island. Guevara had apparently been inspired to create the station by observing the effectiveness of CIA supplied radio in Guatemala in ousting the government of Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán.[104] To quell the rebellion, Cuban government troops began executing rebel prisoners on the spot, and regularly rounded up, tortured, and shot civilians as a tactic of intimidation.[105] By March 1958, the continued atrocities carried out by Batista's forces led the United States to stop selling arms to the Cuban government.[93] Then, in late July 1958, Guevara played a critical role in the Battle of Las Mercedes by using his column to halt a force of 1,500 men called up by Batista's General Cantillo in a plan to encircle and destroy Castro's forces. Years later, Major Larry Bockman of the United States Marine Corps analyzed and described Che's tactical appreciation of this battle as "brilliant".[106] During this time Guevara also became an "expert" at leading hit-and-run tactics against Batista's army, and then fading back into the countryside before the army could counterattack.[107] |

指揮官としての役割 副司令官として、ゲバラは厳格な規律主義者であり、脱走者を射殺することさえあった。脱走者は反逆者として処罰され、ゲバラは任務放棄を企てる者たちを捜 索する部隊を派遣することで知られていた。[94] その結果、ゲバラは残虐さと冷酷さで恐れられるようになった。[95] ゲリラ戦中、ゲバラはスパイ、脱走兵、またはスパイの容疑をかけられた複数の男性に対する即決処刑にも責任を負っていた。[96] ゲバラの日記には、最初のそのような処刑の記録がある。対象は、カストロ派ゲリラの案内役を務めていた農民のエウティミオ・ゲラで、キューバ空軍の攻撃の ために反乱軍の位置を繰り返し漏らした見返りに1万ペソの約束を受けたことを自白した。[97] この情報は、バティスタ軍が革命に同情する農民の自宅を焼くのに利用された。[97] ゲラが「早く自分の命を終わらせてくれ」と頼んだところ[97]、チェは前に出て彼の頭を撃ち、次のように書いた。「この状況は、人民にとってもエウティ ミオにとっても不快だったので、私は彼を右側の脳に 32 口径の拳銃で撃ち、右側頭葉から弾丸を抜け出させて、この問題を解決した。[98] 彼の科学的記録と事実を淡々と記述した説明は、ある伝記作家に「戦争のその時点での暴力に対する驚くべき冷静さ」を示唆した。[98] 後にゲバラは、この事件を文学的に描いた『裏切者の死』を出版し、エウティミオの裏切りと処刑前の「革命が私の子供たちを守ってくれ」という願いを、「犠 牲を通じた贖罪の革命的寓話」へと変容させた。[98]  エスカンブレイ山脈のゲリラ基地にいるゲバラ ゲバラは、厳格で厳しい性格を維持していたものの、指揮官としての役割を教師としての役割とも考えており、戦闘の合間には、ロバート・ルイス・スティーブ ンソン、ミゲル・デ・セルバンテス、スペインの叙情詩人などの作品を読んで部下たちを楽しませた。[99] この役割と、ホセ・マルティの「国境のない識字教育」の原則に触発されて、ゲバラはさらに、反乱軍兵士たちが、共に暮らし、共に戦う教育を受けていない農 民たちに、読み書きを教える時間を毎日確保するよう徹底した。ゲバラはこれを「無知との戦い」と呼んでいた。[92] グエバラの指揮下で戦ったトマス・アルバは、後に「チェは厳格で要求が厳しい人物でしたが、愛されていました。私たちは彼のために命を捧げてもよかった」 と述べています。[100] 彼の指揮官であったフィデル・カストロは、グエバラを「知性にあふれ、大胆で、部隊に対して大きな道徳的権威を持つ」模範的な指導者と評しています。 [101] カストロはさらに、ゲバラはリスクを冒しすぎ、甚至「無謀な傾向があった」と指摘している。[102] ゲバラの少年時代の副官、ホエル・イグレシアスは日記に、ゲバラの戦闘中の行動が敵からも称賛されたと記している。ある時、イグレシアスは戦闘で負傷した 時のことを次のように述べています。「チェは弾丸を無視して私の方へ駆け寄り、私を肩に担ぎ上げ、その場から連れ出した。警備兵たちは彼に発砲する勇気が なかった……後で彼らは、彼がベルトに拳銃を差し込んだまま危険を無視して駆け出すのを見て、彼に大きな印象を受けたと言った。」[103] ゲバラは、1958年2月に秘密のラジオ局「ラジオ・レベルデ(反乱軍ラジオ)」の設立に尽力し、7月26日運動の声明とともにキューバ国民にニュースを 放送し、島内で増加する反乱軍部隊間の無線電話通信を確保した。ゲバラは、CIAがグアテマラでヤコボ・アルベンツ・グスマン政権の打倒に効果があったラ ジオを観察し、その効果に感銘を受けてこのラジオ局を設立したらしい。[104] 反乱を鎮圧するため、キューバ政府軍は反乱軍の捕虜をその場で処刑し、威嚇手段として民間人を定期的に一斉検挙、拷問、銃殺した。[105] 1958年3月までに、バティスタ軍による残虐行為が続き、米国はキューバ政府への武器販売を停止した。[93] その後、1958年7月下旬、ゲバラはラス・メルセデス戦において、バティスタのカンティロ将軍がカストロの部隊を包囲・破壊する計画で動員した 1,500人の部隊を、自身の部隊で阻止する重要な役割を果たした。数年後にアメリカ海兵隊のラリー・ボックマン大佐は、この戦いのゲバラの戦術的判断を 「 brillant( brillant)」と分析し、記述した。[106] この時期、ゲバラはバティスタ軍に対する奇襲戦術の「専門家」となり、軍が反撃する前に農村部へ撤退する戦術を確立した。[107] |

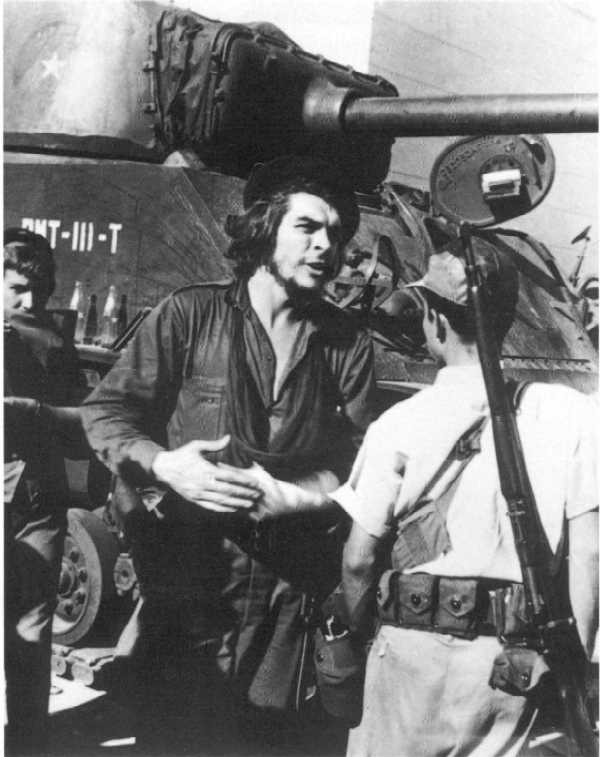

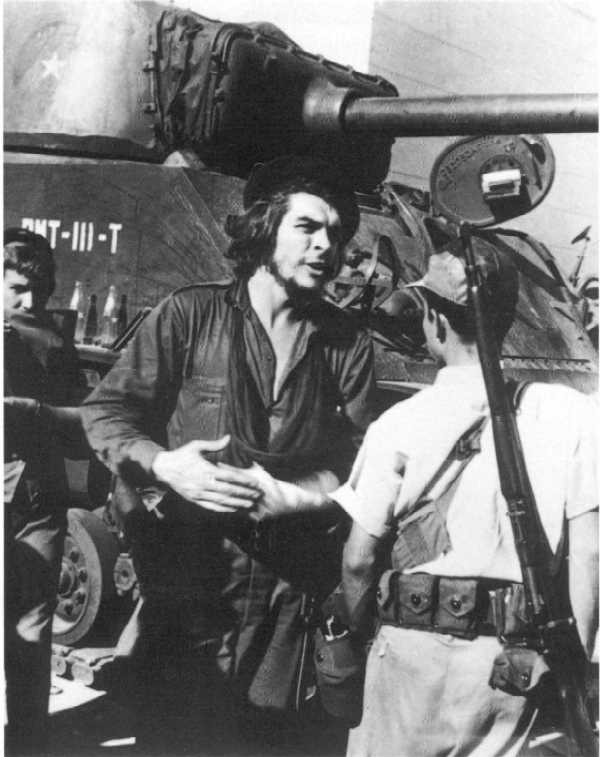

| Final offensive Main article: Battle of Santa Clara  After the Battle of Santa Clara, 1 January 1959 As the war extended, Guevara led a new column of fighters dispatched westward for the final push towards Havana. Travelling by foot, Guevara embarked on a difficult 7-week march, only travelling at night to avoid an ambush and often not eating for several days.[108] In the closing days of December 1958, Guevara's task was to cut the island in half by taking Las Villas province. In a matter of days he executed a series of "brilliant tactical victories" that gave him control of all but the province's capital city of Santa Clara.[108] Guevara then directed his "suicide squad" in the attack on Santa Clara, which became the final decisive military victory of the revolution.[109][110] In the six weeks leading up to the battle, there were times when his men were completely surrounded, outgunned, and overrun. Che's eventual victory despite being outnumbered 10:1 remains in the view of some observers a "remarkable tour de force in modern warfare".[111] Radio Rebelde broadcast the first reports that Guevara's column had taken Santa Clara on New Year's Eve 1958. This contradicted reports by the heavily controlled national news media, which had at one stage reported Guevara's death during the fighting. At 3 am on 1 January 1959, upon learning that his generals were negotiating a separate peace with Guevara, Fulgencio Batista boarded a plane in Havana and fled for the Dominican Republic, along with an amassed "fortune of more than $300,000,000 through graft and payoffs".[112] The following day on 2 January, Guevara entered Havana to finally take control of the capital.[113] Fidel Castro took six more days to arrive, as he stopped to rally support in several large cities on his way to rolling victoriously into Havana on 8 January 1959. The final death toll from the two years of revolutionary fighting was 2,000 people.[114] |

最終攻勢 詳細記事:サンタ・クララの戦い  1959年1月1日、サンタ・クララの戦い後 戦争が長期化する中、ゲバラはハバナへの最終攻勢のため、西へ派遣された新たな戦闘部隊を率いた。徒歩で移動したゲバラは、待ち伏せを避けるため夜間にの み進軍し、数日間食事を摂らないこともあった困難な7週間の行軍を開始した。[108] 1958年12月下旬、ゲバラの任務はラス・ビジャス州を制圧し、島を二分することだった。数日のうちに、彼は「見事な戦術的勝利」を連発し、州都サン タ・クララを除く全地域を制圧した。[108] グエバラはその後、サンタ・クララ攻撃に「自殺部隊」を指揮し、これが革命の最終的な決定的な軍事的勝利となった。[109][110] 戦闘前の6週間には、彼の部隊が完全に包囲され、兵力でも圧倒され、制圧される状況があった。チェが10対1の兵力差を覆して勝利を収めたことは、一部の 観察者からは「現代戦における驚くべき戦術的傑作」と評価されている。[111] ラジオ・レベルデは、1958 年の大晦日にゲバラの部隊がサンタ・クララを占領したという最初の報道を放送した。これは、厳重に統制された全国ニュースメディアの報道と矛盾していた。 全国ニュースメディアは、ある時点で、戦闘中にゲバラが死亡したと報じていた。1959年1月1日午前3時、将軍たちがゲバラと単独和平交渉を行っている ことを知ったフルヘンシオ・バティスタは、ハバナから飛行機でドミニカ共和国へ逃亡した。彼は賄賂と賄賂で蓄えた「3億ドルを超える財産」を携えていた。 [112] 翌1月2日、ゲバラはハバナに入り、ついに首都の支配権を握った。[113] フィデル・カストロは、1959年1月8日にハバナに勝利して入城するまでに、いくつかの大都市で支持を固めるために立ち寄り、到着までにさらに6日間を 要した。2年にわたる革命戦争の最終的な死者数は2,000人にのぼった。[114] |

| Political career in Cuba Further information: Consolidation of the Cuban Revolution Revolutionary tribunals  (Right to left) rebel leader Camilo Cienfuegos, Cuban President Manuel Urrutia Lleó, and Guevara (January 1959) The first major political crisis arose over what to do with the captured Batista officials who had perpetrated the worst of the repression.[115] During the rebellion against Batista's dictatorship, the general command of the rebel army, led by Fidel Castro, introduced into the territories under its control the 19th-century penal law commonly known as the Ley de la Sierra (Law of the Sierra).[116] This law included the death penalty for serious crimes, whether perpetrated by the Batista regime or by supporters of the revolution. In 1959, the revolutionary government extended its application to the whole of the republic and to those it considered war criminals, captured and tried after the revolution. According to the Cuban Ministry of Justice, this latter extension was supported by the majority of the population, and followed the same procedure as those in the Nuremberg trials held by the Allies after World War II.[117] To implement a portion of this plan, Castro named Guevara commander of the La Cabaña Fortress prison for a five-month tenure (2 January through 12 June 1959).[118] Guevara was charged by the new government with purging the Batista army and consolidating victory by exacting "revolutionary justice" against those regarded as traitors, chivatos (informants) or war criminals.[119] As commander of La Cabaña, Guevara reviewed the appeals of those convicted during the revolutionary tribunal process.[11] The tribunals were conducted by 2–3 army officers, an assessor, and a respected local citizen.[120] On some occasions, the penalty delivered by the tribunal was death by firing-squad.[121] Raúl Gómez Treto, senior legal advisor to the Cuban Ministry of Justice, has argued that the death penalty was justified in order to prevent citizens themselves from taking justice into their own hands, as had happened twenty years earlier in the anti-Machado rebellion.[122] Biographers note that in January 1959 the Cuban public was in a "lynching mood",[123] and point to a survey at the time showing 93% public approval for the tribunal process.[11]  Televised execution of Colonel Rojas, ordered by Che Guevara. (7 January 1959). One of the first public executions ordered by Guevara was the execution of Colonel Rojas, which was broadcast on Cuban television. Colonel Rojas was the chief of police in Santa Clara, whose officers had held out against the rebels until the last moment of fighting during the Battle of Santa Clara. After his capture, Rojas' family received a letter of safe departure, inferring he'd be kept alive and released. Soon afterwards, Guevara ordered Rojas to be executed on 7 January 1959. When the footage was aired on television, Rojas' family was at first relieved to see him alive, but after realizing he was being placed in front of a firing squad, they began to scream as he was then shot. The footage was later broadcast around the world, becoming one of the first killings ever aired on television.[124][125] On 22 January 1959, a Universal Newsreel broadcast in the United States narrated by Ed Herlihy featured Fidel Castro asking an estimated one million Cubans whether they approved of the executions, and being met with a roaring "¡Sí!" (yes).[126] With between 1,000[127] and 20,000 Cubans estimated to have been killed at the hands of Batista's collaborators,[128][129][130][131] and many of the accused war criminals sentenced to death accused of torture and physical atrocities,[11] the newly empowered government carried out executions, punctuated by cries from the crowds of "¡al paredón!" ([to the] wall!),[115] which biographer Jorge Castañeda describes as "without respect for due process".[132] |

キューバでの政治活動 詳細情報:キューバ革命の統合 革命裁判所  (右から左)反乱軍の指導者カミーロ・シエンフエゴス、キューバ大統領マヌエル・ウルティア・レオ、ゲバラ(1959年1月) 最初の大きな政治危機は、最悪の弾圧を行ったバティスタ政権の捕虜となった高官たちの処分をめぐって生じた。[115] バティスタ独裁政権に対する反乱中、フィデル・カストロ率いる反乱軍の総司令部は、その支配下にある地域に19世紀の刑法である「シエラ法」(Ley de la Sierra)を導入した。[116] この法律には、バティスタ政権によって犯された犯罪か、革命支持者によって犯された犯罪かを問わず、重大な犯罪に対する死刑が規定されていた。1959 年、革命政府はこの法の適用を共和国全土に拡大し、革命後に捕らえられ裁判にかけられた戦争犯罪者と見なされた者にも適用した。キューバ司法省によると、 この拡大措置は国民の過半数の支持を得ており、第二次世界大戦後に連合国がニュルンベルク裁判で採用した手続きと同様の手続きに従った。[117] この計画の一部を実施するため、カストロはゲバラをラ・カバニャ要塞刑務所の司令官に任命し、5ヶ月間の任期(1959年1月2日から6月12日)を付与 した。[118] 新政府はゲバラに、バティスタ軍を粛清し、裏切り者、チバトス(密告者)、または戦争犯罪者と見なされた者に対して「革命的正義」を執行することで勝利を 固める任務を課した。[119] ラ・カバニャの司令官として、ゲバラは革命裁判所で有罪判決を受けた者の上訴を審査した。[11] 裁判は、2~3人の軍人、1人の評議委員、および尊敬される地元住民によって行われた。[120] いくつかのケースでは、裁判所の判決は銃殺刑だった。[121] キューバ司法省の首席法務顧問だったラウル・ゴメス・トレトは、20年前に反マチャド反乱で起きたように、市民が自警団を結成して正義を執行するのを防ぐ ため、死刑は正当化されると主張している。[122] 伝記作家たちは、1959年1月、キューバ国民は「リンチ気分」に陥っていたと記し[123]、当時の調査で、93%の国民が裁判所の審理を承認していた ことを指摘している[11]。  チェ・ゲバラの命令によるロハス大佐のテレビ中継された処刑(1959年1月7日)。 ゲバラが命じた最初の公開処刑の一つは、ロハス大佐の処刑で、これはキューバのテレビで放送された。ロハス大佐はサンタクララの警察長官で、サンタクララ 戦いの最後の瞬間まで反乱軍に抵抗した警察官たちを指揮していた。捕らえられた後、ロハスの家族は安全な退去を許可する手紙を受け取り、彼が生き残って釈 放されるものと推測していた。その後間もなく、ゲバラはロハスを1959年1月7日に処刑するよう命じた。テレビで映像が放送された際、ロハスの家族は彼 が生きているのを見て最初は安堵したが、彼が銃殺隊の前に立たされていることに気づくと、彼が射殺されるのを見て叫び始めた。この映像は後に世界中に放送 され、テレビで放送された最初の殺害の一つとなった。[124][125] 1959年1月22日、アメリカ合衆国で放送されたユニバーサル・ニュースリール(ナレーター:エド・ハーリヒ)では、フィデル・カストロが推定100万 人のキューバ人に処刑を承認するかどうか尋ね、激しい「¡Sí!」(はい)という返答が返ってくる様子が放送された。[126] バティスタの協力者によって殺害されたキューバ人は1,000人[127]から20,000人と推定され、[128][129][130][131] 拷問や身体的残虐行為の罪で死刑判決を受けた戦争犯罪容疑者の多く[11]に対し、新政権は処刑を実施した。群衆から「¡al paredón!」(壁へ!)という叫び声が響き渡り[115]、伝記作家ホルヘ・カステニャーダはこれを「適正手続きを無視した」と記述している [132]。 |

| I have yet to find a single

credible source pointing to a case where Che executed "an innocent".

Those persons executed by Guevara or on his orders were condemned for

the usual crimes punishable by death at times of war or in its

aftermath: desertion, treason or crimes such as rape, torture or

murder. I should add that my research spanned five years, and included

anti-Castro Cubans among the Cuban-American exile community in Miami

and elsewhere. —Jon Lee Anderson, author of Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, PBS forum[133] Although accounts vary, it is estimated that several hundred people were executed nationwide during this time, with Guevara's jurisdictional death total at La Cabaña ranging from 55 to 105.[134] Conflicting views exist of Guevara's attitude towards the executions at La Cabaña. Some exiled opposition biographers report that he relished the rituals of the firing squad, and organized them with gusto, while others relate that Guevara pardoned as many prisoners as he could.[132] All sides acknowledge that Guevara had become a "hardened" man who had no qualms about the death penalty or about summary and collective trials. If the only way to "defend the revolution was to execute its enemies, he would not be swayed by humanitarian or political arguments".[132] In a 5 February 1959 letter to Luis Paredes López in Buenos Aires, Guevara states unequivocally: "The executions by firing squads are not only a necessity for the people of Cuba, but also an imposition of the people."[135] |

チェが「無実の人」を処刑したという事例を指摘する、信頼できる情報源

は、私はまだ1つも見つけていない。ゲバラによって、あるいは彼の命令によって処刑された人々は、戦争中や戦後において死刑に処せられる通常の犯罪、すな

わち脱走、反逆、あるいは強姦、拷問、殺人などの犯罪で有罪判決を受けた者たちだった。私の調査は5年間に及び、マイアミやその他の地域のキューバ系アメ

リカ人亡命者コミュニティのうち、反カストロ派も対象としたことを付け加えておく。 —ジョン・リー・アンダーソン、『チェ・ゲバラ:革命の人生』著者、PBS フォーラム[133] 報告はさまざまであるが、この間に全国で数百人が処刑され、ゲバラの管轄下にあるラ・カバニャでの処刑者数は 55 人から 105 人に上ると推定されている[134]。ラ・カバニャでの処刑に対するゲバラの態度については、さまざまな見解がある。亡命中の反体制派の伝記作家たちは、 ゲバラは銃殺の儀礼を喜び、熱意をもってそれを組織したと報告している。一方、ゲバラはできるだけ多くの囚人を赦免したと伝える者もいる[132]。すべ ての関係者は、ゲバラが死刑や即決裁判、集団裁判について何の良心の呵責も感じない「冷酷な」人物になっていたことを認めている。「革命を守る唯一の手段 が敵を処刑することであるならば、彼は人道的あるいは政治的議論に左右されることはなかっただろう」[132]。1959年2月5日、ブエノスアイレスの ルイス・パレデス・ロペス宛ての手紙の中で、ゲバラは「銃殺による処刑は、キューバ国民にとって必要なだけでなく、国民が課した義務でもある」と明確に述 べている[135]。 |

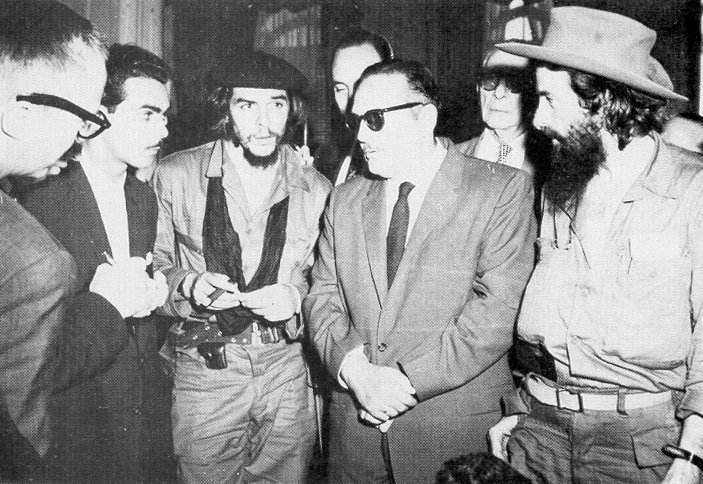

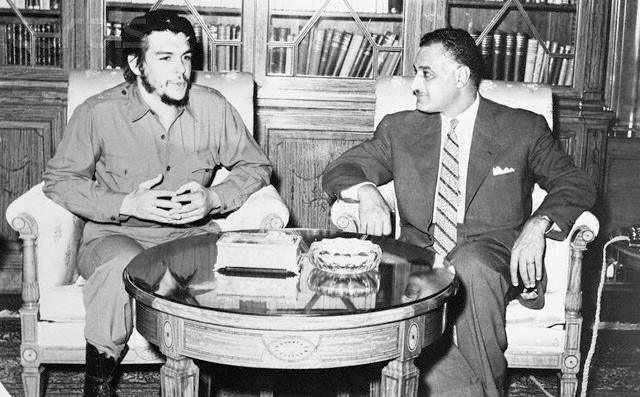

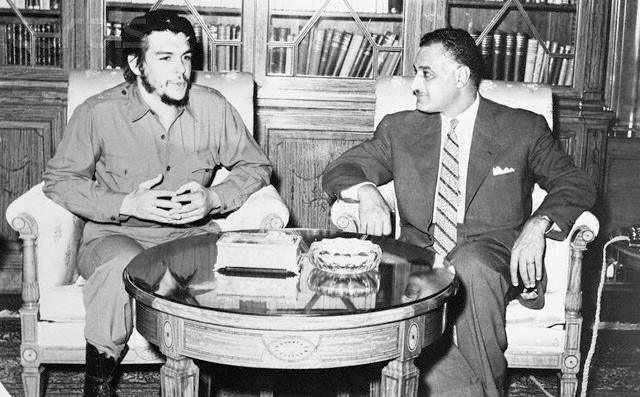

| Early political office Further information: Agrarian reforms in Cuba, Huber Matos affair, and La Coubre explosion In mid-January 1959, Guevara went to live at a summer villa in Tarará to recover from a violent asthma attack.[136] While there he started the Tarará Group, a group that debated and formed the new plans for Cuba's social, political, and economic development.[137] In addition, Che began to write his book Guerrilla Warfare while resting at Tarara.[137] In February, the revolutionary government proclaimed Guevara "a Cuban citizen by birth" in recognition of his role in the triumph.[138] When Hilda Gadea arrived in Cuba in late January, Guevara told her that he was involved with another woman, and the two agreed on a divorce,[139] which was finalized on 22 May.[140] On 27 January 1959, Guevara made one of his most significant speeches where he talked about "the social ideas of the rebel army". During this speech he declared that the main concern of the new Cuban government was "the social justice that land redistribution brings about".[141] A few months later, 17 May 1959, the agrarian reform law, crafted by Guevara, went into effect, limiting the size of all farms to 1,000 acres (400 ha). Any holdings over these limits were expropriated by the government and either redistributed to peasants in 67-acre (270,000 m2) parcels or held as state-run communes.[142] The law also stipulated that foreigners could not own Cuban sugar-plantations.[143]  Guevara in 1960, walking through the streets of Havana with his second wife Aleida March (right) On 2 June 1959, he married Aleida March, a Cuban-born member of 26 July movement with whom he had been living since late 1958. Guevara returned to the seaside village of Tarara in June for his honeymoon with Aleida.[144] A civil ceremony was held at La Cabaña military fortress.[145] In total, Guevara would have five children from his two marriages.[146]  Che Guevara meeting Josip Broz Tito, during Guevara's 1959 diplomatic travels.  Che Guevara visiting Gaza during his diplomatic tour. (1959) On 12 June 1959, Castro sent Guevara out on a three-month tour of mostly Bandung Pact countries (Morocco, Sudan, Egypt, Syria, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, Indonesia, Japan, Yugoslavia, and Greece) and the cities of Singapore and Hong Kong.[147] Sending Guevara away from Havana allowed Castro to appear to distance himself from Guevara and his Marxist sympathies, which troubled both the United States and some of the members of Castro's 26 July Movement.[148] While in Jakarta, Guevara visited Indonesian president Sukarno to discuss the recent revolution of 1945–1949 in Indonesia and to establish trade relations between their two countries. The two men quickly bonded, as Sukarno was attracted to Guevara's energy and his relaxed informal approach; moreover they shared revolutionary leftist aspirations against Western imperialism.[149] Guevara next spent 12 days in Japan (15–27 July), participating in negotiations aimed at expanding Cuba's trade relations with that country. During the visit he refused to visit and lay a wreath at Japan's Tomb of the Unknown Soldier commemorating soldiers lost during World War II, remarking that the Japanese "imperialists" had "killed millions of Asians".[150] Instead, Guevara stated that he would visit Hiroshima, where the American military had detonated an atomic bomb 14 years earlier.[150] Despite his denunciation of Imperial Japan, Guevara considered President Truman a "macabre clown" for the bombings,[151] and after visiting Hiroshima and its Peace Memorial Museum he sent back a postcard to Cuba stating, "In order to fight better for peace, one must look at Hiroshima."[152] Upon Guevara's return to Cuba in September 1959, it became evident that Castro now had more political power. The government had begun land seizures in accordance with the agrarian reform law, but was hedging on compensation offers to landowners, instead offering low-interest "bonds", a step which put the United States on alert. At this point the affected wealthy cattlemen of Camagüey mounted a campaign against the land redistributions and enlisted the newly disaffected rebel leader Huber Matos, who along with the anti-communist wing of the 26 July Movement, joined them in denouncing "communist encroachment".[153] During this time Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo was offering assistance to the "Anti-Communist Legion of the Caribbean" which was training in the Dominican Republic. This multi-national force, composed mostly of Spaniards and Cubans, but also of Croatians, Germans, Greeks, and right-wing mercenaries, was plotting to topple Castro's new regime.[153] At this stage, Guevara acquired the additional position of Minister of Finance, as well as President of the National Bank.[154] These appointments, combined with his existing position as Minister of Industries, placed Guevara at the zenith of his power, as the "virtual czar" of the Cuban economy.[155] As a consequence of his position at the head of the central bank, it became Guevara's duty to sign the Cuban currency, which per custom bore his signature. Instead of using his full name, he signed the bills solely "Che".[156] It was through this symbolic act, which horrified many in the Cuban financial sector, that Guevara signaled his distaste for money and the class distinctions it brought about.[156] Guevara's long time friend Ricardo Rojo later remarked that "the day he signed Che on the bills, (he) literally knocked the props from under the widespread belief that money was sacred."[157] International threats were heightened when, on 4 March 1960, two massive explosions ripped through the French freighter La Coubre, which was carrying Belgian munitions from the port of Antwerp, and was docked in Havana Harbor. The blasts killed at least 76 people and injured several hundred, with Guevara personally providing first aid to some of the victims. Fidel Castro immediately accused the CIA of "an act of terrorism" and held a state funeral the following day for the victims of the blast.[158] At the memorial service Alberto Korda took the famous photograph of Guevara, now known as Guerrillero Heroico.[159] Perceived threats prompted Castro to eliminate more "counter-revolutionaries" and to utilize Guevara to drastically increase the speed of land reform. To implement this plan, a new government agency, the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA), was established by the Cuban government to administer the new agrarian reform law. INRA quickly became the most important governing body in the nation, with Guevara serving as its head in his capacity as minister of industries.[143][need quotation to verify] Under Guevara's command, INRA established its own 100,000-person militia, used first to help the government seize control of the expropriated land and supervise its distribution, and later to set up cooperative farms. The land confiscated included 480,000 acres (190,000 ha) owned by United States corporations.[143] Months later, in retaliation, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower sharply reduced United States imports of Cuban sugar (Cuba's main cash crop), which led Guevara on 10 July 1960 to address over 100,000 workers in front of the Presidential Palace at a rally to denounce the "economic aggression" of the United States.[155] Time Magazine reporters who met with Guevara around this time described him as "guid(ing) Cuba with icy calculation, vast competence, high intelligence, and a perceptive sense of humor".[10] |

初期の政治活動 詳細情報:キューバの農業改革、ウーバー・マトス事件、ラ・クブレ号爆発事件 1959年1月中旬、ゲバラは激しい喘息の発作から回復するため、タララの別荘で療養生活を送った[136]。その間、彼はキューバの社会、政治、経済の 発展に関する新しい計画について議論し、策定する「タララ・グループ」を設立した。[137] さらに、ゲバラはタララで休養中に『ゲリラ戦』の執筆を開始した。[137] 2月、革命政府はゲバラの勝利への貢献を認め、彼を「生まれながらのキューバ市民」と宣言した。[138] 1月下旬、ヒルダ・ガデアがキューバに到着したとき、ゲバラは彼女に別の女性との関係を打ち明け、2人は離婚に合意した[139]、そして5月22日に離 婚が成立した[140]。 1959年1月27日、ゲバラは「反乱軍の社会思想」について語った、最も重要な演説のひとつを行った。この演説で彼は、新キューバ政府の主要な課題は 「土地の再分配がもたらす社会正義」だと宣言した。[141] 数ヶ月後の1959年5月17日、ゲバラが策定した農業改革法が施行され、すべての農場の規模が1,000エーカー(400ヘクタール)に制限された。こ の制限を超える土地は政府によって接収され、67エーカー(270,000平方メートル)の区画に小作農に再分配されるか、国家管理の共同体として保有さ れた。[142] また、この法律は外国人によるキューバの砂糖プランテーションの所有を禁止した。[143]  1960年、ハバナの街を2番目の妻アレイダ・マルチ(右)と歩くゲバラ 1959年6月2日、ゲバラは1958年末から同棲していた、7月26日運動のメンバーでキューバ生まれのアレイダ・マルチと結婚した。ゲバラはアレイダ との新婚旅行のため、6月に海辺の村タララに戻った。[144] 市民結婚式はラ・カバニャ軍事要塞で行われた。[145] グエバラは2回の結婚で合計5人の子供を残した。[146]  1959年の外交旅行中に、ヨシップ・ブロズ・ティトと会うチェ・ゲバラ。  外交旅行中にガザを訪問するチェ・ゲバラ(1959年)。 1959年6月12日、カストロはゲバラを3ヶ月間の旅行に派遣した。主にバンドン協定加盟国(モロッコ、スーダン、エジプト、シリア、パキスタン、イン ド、スリランカ、ビルマ、タイ、インドネシア、日本、ユーゴスラビア、ギリシャ)とシンガポール、香港の都市を訪問した。[147] ゲバラをハバナから遠ざけることで、カストロはゲバラと彼のマルクス主義的傾向から距離を置いているように見せることができ、これは米国とカストロの 7 月 26 日運動の一部のメンバーを不安にさせた。[148] ジャカルタ滞在中、ゲバラはインドネシアのスカルノ大統領を訪問し、1945年から1949年にかけてのインドネシアの革命について話し合い、両国の貿易 関係の確立について協議した。二人はすぐに意気投合した。スカルノはゲバラのエネルギーとリラックスした非公式な態度に惹かれた上、西欧帝国主義に対する 革命的な左翼的志向を共有していたからだ。[149] ゲバラは次に日本(7月15日から27日)で12日間を過ごし、キューバと日本の貿易関係を拡大するための交渉に参加した。訪問中、ゲバラは第二次世界大 戦中の戦没者を追悼する日本の「無名戦士の墓」を訪問し、花輪を献花することを拒否し、日本の「帝国主義者」が「数百万のアジア人を殺した」と述べた。 [150] 代わりに、ゲバラは14年前にアメリカ軍が原子爆弾を投下した広島を訪問すると表明した。[150] 帝国日本を非難したにもかかわらず、ゲバラは原爆投下についてトルーマン大統領を「不気味な道化師」と批判した。[151] 広島と平和記念博物館を訪問した後、キューバに送ったポストカードには「平和のために戦うためには、広島を見なければならない」と記した。[152] ゲバラが1959年9月にキューバに戻った際、カストロがより大きな政治権力を握っていることが明らかになった。政府は農業改革法に基づき土地の接収を開 始したが、土地所有者への補償額を保留し、代わりに低金利の「債券」を提示した。この措置はアメリカを警戒させた。この時点で、カマグエイの富裕な牧場主 たちは土地再分配に反対するキャンペーンを展開し、新たに不満を抱くようになった反乱指導者フベルト・マトスを招き入れた。マトスは、7月26日運動の反 共産主義派と共に、彼らと共に「共産主義の侵食」を非難した。[153] この間、ドミニカ共和国の独裁者ラファエル・トルヒーリョは、ドミニカ共和国で訓練を行っていた「カリブ反共産主義軍」に支援を申し出ていました。この多 国籍軍は、主にスペイン人とキューバ人で構成されていましたが、クロアチア人、ドイツ人、ギリシャ人、右翼の傭兵も参加しており、カストロの新政権の打倒 を企てていたのです。[153] この段階で、ゲバラは財務大臣と国立銀行総裁の職も兼任することになった[154]。これらの任命と、それまでの産業大臣の職を合わせると、ゲバラは キューバ経済の「事実上の最高責任者」として、権力の絶頂に立つことになった。[155] 中央銀行のトップとしての立場から、ゲバラはキューバの通貨に署名する義務を負った。伝統的に通貨には署名が必要だったため、彼は本名ではなく「チェ」と だけ署名した。[156] この象徴的な行為は、キューバの金融界を震撼させた。ゲバラはこれにより、金銭とそれがもたらす階級差別への嫌悪を表明した。[156] ゲバラの長い友人であるリカルド・ロホは後年、「彼が紙幣に『チェ』と署名した日、彼は『お金は神聖なものだ』という広まった信念の土台を文字通り崩し た」と述べた。[157] 国際的な脅威は、1960年3月4日、アントワープ港からベルギーの弾薬を積載し、ハバナ港に停泊中のフランス籍貨物船「ラ・クブル」が2度の巨大な爆発 で破壊されたことで高まった。この爆発により、少なくとも 76 人が死亡、数百人が負傷し、ゲバラは自ら一部の犠牲者に応急処置を施した。フィデル・カストロは直ちに CIA を「テロ行為」と非難し、翌日、爆発の犠牲者のために国葬を行った。[158] 追悼式で、アルベルト・コルダは、現在「ゲリラの英雄」として知られるゲバラの有名な写真を撮影した。[159] 脅威を認識したカストロは、より多くの「反革命分子」を排除し、ゲバラを利用して土地改革のスピードを大幅に加速させることを決定した。この計画を実施す るため、キューバ政府は、新しい土地改革法を施行するための新しい政府機関、国家土地改革研究所(INRA)を設立した。INRA は、ゲバラが産業大臣として所長を務め、すぐに国民にとって最も重要な統治機関となった。[143][要出典] ゲバラの指揮の下、INRA は 10 万人規模の民兵組織を設立し、当初は政府が収用した土地の支配権を確保し、その分配を監督するために活用され、後に協同組合農場を設立するために活用され た。没収された土地には、米国企業が所有していた 48 万エーカー(19 万ヘクタール)も含まれていた。[143] 数ヶ月後、報復措置として、ドワイト・D・アイゼンハワー米国大統領は、キューバの主要現金作物である砂糖の米国への輸入を大幅に削減した。これにより、 1960年7月10日、ゲバラは大統領官邸前で10万人以上の労働者を前に演説し、米国の「経済侵略」を非難した。[155] この頃ゲバラと会ったタイム誌の記者たちは、彼を「冷徹な計算、広範な能力、高い知性、そして鋭いユーモアのセンスでキューバを導いている」と描写した。 [10] |

| Guevara was like a father to me

... he educated me. He taught me to think. He taught me the most

beautiful thing which is to be human. —Urbano (a.k.a. Leonardo Tamayo), fought with Guevara in Cuba and Bolivia[160] Along with land reform, Guevara stressed the need for national improvement in literacy. Before 1959 the official literacy rate for Cuba was between 60 and 76%, with educational access in rural areas and a lack of instructors the main determining factors.[161] As a result, the Cuban government at Guevara's behest dubbed 1961 the "year of education" and mobilized over 100,000 volunteers into "literacy brigades", who were then sent out into the countryside to construct schools, train new educators, and teach the predominantly illiterate guajiros (peasants) to read and write.[92][161] Unlike many of Guevara's later economic initiatives, this campaign was "a remarkable success". By the completion of the Cuban literacy campaign, 707,212 adults had been taught to read and write, raising the national literacy rate to 96%.[161] Accompanying literacy, Guevara was also concerned with establishing universal access to higher education. To accomplish this the new regime introduced affirmative action to the universities. While announcing this new commitment, Guevara told the gathered faculty and students at the University of Las Villas that the days when education was "a privilege of the white middle class" had ended. "The University" he said, "must paint itself black, mulatto, worker, and peasant." If it did not, he warned, the people were going to break down its doors "and paint the University the colors they like."[162] |

ゲバラは私にとって父親のような存在だった…彼は私を教育してくれた。彼は私に考えることを教えてくれた。彼は、人間であることの最も美しいことを教えてくれた。 —ウルバノ(別名レオナルド・タマヨ)、 キューバとボリビアでゲバラとともに戦った[160] ゲバラは、土地改革とともに、国民の識字率の向上も重要だと主張した。1959年以前のキューバの公式の識字率は60%から76%で、農村部の教育へのア クセスと教師の不足が主な要因だった[161]。その結果、ゲバラの指示により、キューバ政府は1961年を「教育の年」と宣言し、10万人を超えるボラ ンティアを「識字部隊」に動員。彼らは農村部に派遣され、学校建設、新規教育者の訓練、主に文盲のグアヒロ(農民)への読み書き教育に従事した。[92] [161] ゲバラの後の多くの経済政策とは異なり、このキャンペーンは「目覚ましい成功」を収めた。キューバの識字キャンペーンが完了するまでに、707,212 人の成人が読み書きを習得し、国民の識字率は 96% に上昇した[161]。 識字教育と並行して、ゲバラは高等教育の普遍的なアクセス確立にも力を入れた。この目標を達成するため、新政権は大学にアファーマティブ・アクションを導 入した。この新たな取り組みを発表するにあたり、ゲバラはラス・ヴィラス大学に集まった教職員と学生たちに、教育が「白人中産階級の特権」であった時代は 終わったと語った。「大学は、黒人、混血、労働者、農民で埋め尽くされなければならない」と彼は述べた。そうしなければ、人民が大学の扉を壊して「大学を 好きな色に塗り替える」だろうと警告した。[162] |

| Economic reforms and the "New Man" See also: Guanahacabibes camp In September 1960, when Guevara was asked about Cuba's ideology at the First Latin American Congress, he replied, "If I were asked whether our revolution is Communist, I would define it as Marxist. Our revolution has discovered by its methods the paths that Marx pointed out."[163] Consequently, when enacting and advocating Cuban policy, Guevara cited the political philosopher Karl Marx as his ideological inspiration. In defending his political stance, Guevara confidently remarked, "There are truths so evident, so much a part of people's knowledge, that it is now useless to discuss them. One ought to be Marxist with the same naturalness with which one is 'Newtonian' in physics, or 'Pasteurian' in biology."[164] According to Guevara, the "practical revolutionaries" of the Cuban Revolution had the goal of "simply fulfill(ing) laws foreseen by Marx, the scientist."[164] Using Marx's predictions and system of dialectical materialism, Guevara professed that "The laws of Marxism are present in the events of the Cuban Revolution, independently of what its leaders profess or fully know of those laws from a theoretical point of view."[164] The merit of Marx is that he suddenly produces a qualitative change in the history of social thought. He interprets history, understands its dynamic, predicts the future, but in addition to predicting it (which would satisfy his scientific obligation), he expresses a revolutionary concept: the world must not only be interpreted, it must be transformed. Man ceases to be the slave and tool of his environment and converts himself into the architect of his own destiny. — Che Guevara, Notes for the Study of the Ideology of the Cuban, October 1960[164] Man truly achieves his full human condition when he produces without being compelled by the physical necessity of selling himself as a commodity. — Che Guevara, Man and Socialism in Cuba[165] |

経済改革と「新人間」 参照:グアナハカビベスキャンプ 1960年9月、ゲバラは第1回ラテンアメリカ会議でキューバのイデオロギーについて尋ねられた際、「私たちの革命が共産主義であるかどうかと尋ねられた 場合、私はそれをマルクス主義と定義するだろう。私たちの革命は、その方法によって、マルクスが指摘した道筋を発見した」と述べた[163]。その結果、 キューバの政策を制定し、提唱する際に、ゲバラは、そのイデオロギー的インスピレーションの源として、政治哲学者カール・マルクスを引用した。ゲバラは、 自らの政治的立場を擁護し、「あまりにも明白で、人々の知識の一部となっている真実がある。物理学で『ニュートン派』であるのと同じように、生物学で『パ スツール派』であるのと同じように、マルクス主義者であるべきだ」と自信を持って述べた。[164] ゲバラによると、キューバ革命の「実践的革命家」の目標は、「科学者マルクスが予見した法則を単に実現すること」であった。[164] マルクスの予測と弁証法的唯物論の体系を用いて、ゲバラは「マルクス主義の法則は、その指導者が理論的にそれらを完全に理解しているかどうか、またはそれ らを公言しているかどうかに関わらず、キューバ革命の出来事の中に存在している」と主張した。[164] マルクスの功績は、社会思想の歴史に質的な変化を突然もたらしたことだ。彼は歴史を解釈し、その動態を理解し、未来を予測するが、予測するだけでなく(こ れは彼の科学的義務を満たすものだ)、革命的な概念を表明する:世界は解釈されるだけでなく、変革されなければならない。人間は、環境の奴隷や道具ではな くなり、自らの運命の建築家へと変貌する。 —チェ・ゲバラ、『キューバのイデオロギーの研究のためのメモ』、1960年10月[164] 人間は、自分自身を商品として売り込むという物理的な必要性に駆られることなく生産を行うときに、真に人間としての完全な状態に達する。 —チェ・ゲバラ、『キューバの人々と社会主義』[165] |

Guevara meeting with French existentialist philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir at his office in Havana, March 1960. Sartre later wrote that Che was "the most complete human being of our time". In addition to Spanish, Guevara was fluent in French.[166] In an effort to eliminate social inequalities, Guevara and Cuba's new leadership had moved to swiftly transform the political and economic base of the country through nationalizing factories, banks, and businesses, while attempting to ensure affordable housing, healthcare, and employment for all Cubans.[167] In order for a genuine transformation of consciousness to take root, it was believed that such structural changes had to be accompanied by a conversion in people's social relations and values. Believing that the attitudes in Cuba towards race, women, individualism, and manual labor were the product of the island's outdated past, all individuals were urged to view each other as equals and take on the values of what Guevara termed "el Hombre Nuevo" (the New Man).[167] Guevara hoped his "new man" to be ultimately "selfless and cooperative, obedient and hard working, gender-blind, incorruptible, non-materialistic, and anti-imperialist".[167] To accomplish this, Guevara emphasized the tenets of Marxism–Leninism, and wanted to use the state to emphasize qualities such as egalitarianism and self-sacrifice, at the same time as "unity, equality, and freedom" became the new maxims.[167] Guevara's first desired economic goal of the new man, which coincided with his aversion for wealth condensation and economic inequality, was to see a nationwide elimination of material incentives in favor of moral ones. He negatively viewed capitalism as a "contest among wolves" where "one can only win at the cost of others" and thus desired to see the creation of a "new man and woman".[168] Guevara continually stressed that a socialist economy in itself is not "worth the effort, sacrifice, and risks of war and destruction" if it ends up encouraging "greed and individual ambition at the expense of collective spirit".[169] A primary goal of Guevara's thus became to reform "individual consciousness" and values to produce better workers and citizens.[169] In his view, Cuba's "new man" would be able to overcome the "egotism" and "selfishness" that he loathed and discerned was uniquely characteristic of individuals in capitalist societies.[169] To promote this concept of a "new man", the government also created a series of party-dominated institutions and mechanisms on all levels of society, which included organizations such as labor groups, youth leagues, women's groups, community centers, and houses of culture to promote state-sponsored art, music, and literature. In congruence with this, all educational, mass media, and artistic community based facilities were nationalized and utilized to instill the government's official socialist ideology.[167] In describing this new method of "development", Guevara stated: There is a great difference between free-enterprise development and revolutionary development. In one of them, wealth is concentrated in the hands of a fortunate few, the friends of the government, the best wheeler-dealers. In the other, wealth is the people's patrimony.[170] A further integral part of fostering a sense of "unity between the individual and the mass", Guevara believed, was volunteer work and will. To display this, Guevara "led by example", working "endlessly at his ministry job, in construction, and even cutting sugar cane" on his day off.[171] He was known for working 36 hours at a stretch, calling meetings after midnight, and eating on the run.[169] Such behavior was emblematic of Guevara's new program of moral incentives, where each worker was now required to meet a quota and produce a certain quantity of goods. As a replacement for the pay increases abolished by Guevara, workers who exceeded their quota now only received a certificate of commendation, while workers who failed to meet their quotas were given a pay cut.[169] Guevara unapologetically defended his personal philosophy towards motivation and work, stating: This is not a matter of how many pounds of meat one might be able to eat, or how many times a year someone can go to the beach, or how many ornaments from abroad one might be able to buy with his current salary. What really matters is that the individual feels more complete, with much more internal richness and much more responsibility.[172] At some point in 1960, Guevara ordered the construction of the Guanahacabibes camp: a labor camp to "rehabilitate" his employees who had committed infractions at work. Historians have had difficulty characterizing the camp, because it was extra-legal and thus poorly documented. There is a general consensus that employees worked at the camp to regain their employment after a negative incident, and were under no legal pressure to work at the camp.[173][174] However, the historian Rachel Hynson has theorized that other poorly documented "Guanahacabibes" camps also existed, that were more brutal and legally binding.[175] In the face of a loss of commercial connections with Western states, Guevara tried to replace them with closer commercial relationships with Eastern Bloc states, visiting a number of Marxist states and signing trade agreements with them. At the end of 1960 he visited Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, North Korea, Hungary, and East Germany and signed, for instance, a trade agreement in East Berlin on 17 December 1960.[176] Such agreements helped Cuba's economy to a certain degree but also had the disadvantage of a growing economic dependency on the Eastern Bloc. It was also in East Germany where Guevara met Tamara Bunke (later known as "Tania"), who was assigned as his interpreter, and who joined him years later, and was killed with him in Bolivia. According to Douglas Kellner, his programs were unsuccessful,[177] and accompanied a rapid drop in productivity and a rapid rise in absenteeism.[178] In a meeting with French economist René Dumont, Guevara blamed the inadequacy of the agrarian reform law enacted by the Cuban government in 1959, which turned large plantations into farm cooperatives or split up land amongst peasants.[179] In Guevara's opinion, this situation continued to promote a "heightened sense of individual ownership" in which workers could not see the positive social benefits of their labor, leading them to instead seek individual material gain as before.[180] Decades later, Che's former deputy Ernesto Betancourt, subsequently the director of the US government-funded Radio Martí and an early ally turned Castro-critic, accused Guevara of being "ignorant of the most elementary economic principles."[181] |

1960年3月、ハバナの事務所でフランスの実存主義哲学者ジャン=ポール・サルトルとシモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールと会うゲバラ。サルトルは後に、チェ は「私たちの時代で最も完璧な人間」だったと書いている。ゲバラはスペイン語に加え、フランス語も流暢に話した。[166] 社会的不平等を排除するため、ゲバラとキューバの新指導部は、工場、銀行、企業を国有化し、すべてのキューバ国民に手頃な住宅、医療、雇用を確保しようと 努めながら、国の政治・経済基盤の迅速な変革を進めた[167]。真の意味での意識の変革を定着させるためには、このような構造改革に、人々の社会関係や 価値観の転換も伴わなければならないと信じられていた。キューバの人種、女性、個人主義、肉体労働に対する考え方は、この島の旧態依然とした過去から生ま れたものであると信じ、すべての国民は、お互いを平等に見なし、ゲバラが「エル・オムブレ・ヌエボ(新しい人間)」と呼んだ価値観を受け入れるよう求めら れた。[167] ゲバラは、彼の「新しい人間」が、最終的には「無私無欲で協力的、従順で勤勉、性別を区別せず、腐敗せず、物質主義的ではなく、反帝国主義的」になること を望んでいた。[167] これを達成するために、ゲバラはマルクス・レーニン主義の教義を強調し、国家を利用して「統一、平等、自由」が新たな格律となる一方で、平等主義や自己犠 牲などの資質を強調したいと考えていました。[167] ゲバラが新人類に最初に望んだ経済目標は、富の集中と経済的不平等に対する嫌悪と一致しており、物質的なインセンティブを全国的に排除し、道徳的なインセ ンティブに置き換えることだった。彼は、資本主義を「狼の争い」と否定的に捉え、「他者を犠牲にしてしか勝てない」と批判し、したがって「新しい男性と女 性」の創造を望んだ。[168] ゲバラは、社会主義経済自体が「集団精神を犠牲にして貪欲と個人主義を助長する」結果になるなら、戦争と破壊の努力、犠牲、リスクに値しないことを繰り返 し強調した。[169] ゲバラの主要な目標の一つは、より良い労働者と市民を育成するため、「個人の意識」と価値観を改革することだった。[169] 彼の見解では、キューバの「新しい人間」は、彼が憎悪し、資本主義社会の人間に特有の特性と見なした「自己中心主義」と「利己主義」を克服できるはずだっ た。[169] この「新しい人間」の概念を推進するため、政府は、労働団体、青年同盟、女性団体、コミュニティセンター、文化会館など、国家が支援する芸術、音楽、文学 を推進する組織を含む、社会全層における一連の政党主導の機関や仕組みを創設した。これに合わせて、教育、マスメディア、芸術に関するすべてのコミュニ ティ施設が国有化され、政府の公式の社会主義イデオロギーを浸透させるために利用された。[167][167] この新しい「開発」手法について、ゲバラは次のように述べている。 自由企業による開発と革命による開発には大きな違いがある。前者は、幸運な少数の人々、政府の友人、最も手練の政治家たちの手に富が集中する。後者は、富は人民の遺産である。 ゲバラは、「個人と集団の統一感」を育むためのさらに重要な要素として、ボランティア活動と意志を挙げていた。これを示すため、ゲバラは「自ら模範を示 す」ことで、省庁の職務に没頭し、建設作業に従事し、休日にはサトウキビの収穫作業まで行った。[171] 彼は36時間連続で働き、真夜中に会議を招集し、移動中に食事を済ませることで知られていた。[169] このような行動は、ゲバラの新たな道徳的インセンティブ制度の象徴だった。この制度では、各労働者は quota(ノルマ)を達成し、一定量の製品を生産することが求められた。ゲバラが廃止した給与引き上げに代わって、ノルマを超えた労働者は表彰状を受け 取るのみとなり、ノルマを達成できなかった労働者は給与カットを科せられた。[169] ゲバラは、モチベーションと仕事に対する自分の哲学を、次のように堂々と擁護した。 これは、1 人あたり何キロの肉を食べられるか、1 年に何回ビーチに行けるか、現在の給料で海外から何個の装飾品を買えるかといった問題ではない。本当に重要なのは、個人がより充実感を感じ、より豊かな内面を持ち、より責任感を持つようになることだ。[172] 1960年のある時点で、ゲバラはグアナハカビベス収容所の建設を命じた。これは、職場で違反行為を行った従業員を「更生」するための労働収容所だった。 この収容所は、法外であり、文書も不十分であったため、歴史家たちはその性格を定義するのに苦労している。従業員は、負の出来事後に雇用を回復するために キャンプで働かされ、法的な強制力はなかったという点では、一般的な合意がある。[173][174] しかし、歴史家のレイチェル・ヒンソンは、より残酷で法的な拘束力のある「グアナハカビベス」キャンプが他にも存在したと推測している。[175] 西側諸国との商業的つながりの喪失に直面したゲバラは、東欧諸国とのより密接な商業関係を築くことでこれを補おうとし、複数のマルクス主義国家を訪問し、 貿易協定を締結した。1960年末にはチェコスロバキア、ソビエト連邦、北朝鮮、ハンガリー、東ドイツを訪問し、例えば1960年12月17日に東ベルリ ンで貿易協定を締結した。[176] これらの協定はキューバの経済に一定程度の支援をもたらしたが、東欧諸国への経済的依存が深まるという欠点もあった。また、ゲバラは東ドイツでタマラ・ブ ンケ(のちに「タニア」として知られる)と出会い、彼女は彼の通訳として任命され、数年後に彼と共にボリビアで殺害された。 ダグラス・ケルナーによると、彼の政策は失敗に終わり[177]、生産性の急激な低下と欠勤の急増を伴った[178]。フランスの経済学者ルネ・デュモン との会談で、ゲバラは、1959年にキューバ政府が制定した、大規模農園を農業協同組合化したり、農民に土地を分割したりする農業改革法の不備を非難し た。[179] グエバラの意見では、この状況は、労働者が自分の労働の社会的利益を見出せない「個人所有意識の高まり」を助長し、その結果、労働者は以前と同じように個 人的な物質的利益を追求するようになったと。[180] 数十年後、チェの元副官であり、その後、米国政府資金によるラジオ・マルティの局長を務め、初期の同盟者からカストロ批判者となったエルネスト・ベタン コートは、ゲバラを「最も基本的な経済原則を知らない」と非難した。[181] |

Guevara fishing off the coast of Havana, on 15 May 1960. Along with

Castro, Guevara competed with expatriate author Ernest Hemingway at

what was known as the "Hemingway Fishing Contest". |

1960年5月15日、ハバナ沖で釣りをするゲバラ。カストロとともに、ゲバラは、いわゆる「ヘミングウェイ・フィッシング・コンテスト」で、亡命作家アーネスト・ヘミングウェイと競い合った. |