シャルル・フーリエ

François Marie Charles Fourier, 1772-1837

Françoise

Foliot - Jean Gigoux - Portrait de Charles Fourrier

☆ フランソワ・マリー・シャルル・フーリエ(/ˈfɪ, -iər/ [1] French: [⠚l fu↪Ll_281je; 1772年4月7日 - 1837年10月10日)はフランスの哲学者で、影響力のある初期の社会主義思想家であり、ユートピア社会主義の創始者の一人である[2]。例えば、フー リエは1837年にフェミニズムという言葉を生み出したとされている[3]。 フーリエの社会的見解や提案は、意図主義的共同体の運動全体を刺激した。アメリカでは、オハイオ州ユートピア、テキサス州ダラス近郊のラ・レユニオン、イ リノイ州チューリッヒ湖、ニュージャージー州レッドバンクのノースアメリカン・ファランクス、マサチューセッツ州ウェスト・ロックスベリーのブルック・ ファーム、ニューヨーク州のコミュニティ・プレイスとソダス・ベイ・ファランクス、カンザス州シルクヴィルなどがある。フランスのギーズでは、ギーズ・ ファミリス[fr; de; pt]に影響を与えた。フーリエはその後、さまざまな革命思想家や作家に影響を与えた。

| François Marie

Charles Fourier (/ˈfʊrieɪ, -iər/;[1] French: [ʃaʁl fuʁje]; 7 April 1772

– 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early

socialist thinker, and one of the founders of utopian socialism.[2]

Some of his views, held to be radical in his lifetime, have become

mainstream in modern society. For instance, Fourier is credited with

having originated the word feminism in 1837.[3] Fourier's social views and proposals inspired a whole movement of intentional communities. Among them in the United States were the community of Utopia, Ohio; La Reunion near present-day Dallas, Texas; Lake Zurich, Illinois; the North American Phalanx in Red Bank, New Jersey; Brook Farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts; the Community Place and Sodus Bay Phalanx in New York State; Silkville, Kansas, and several others. In Guise, France, he influenced the Familistery of Guise [fr; de; pt]. Fourier later inspired a diverse array of revolutionary thinkers and writers. |

フランソワ・マリー・シャルル・フーリエ(/ˈfɪ, -iər/

[1] French: [⠚l fu↪Ll_281je; 1772年4月7日 -

1837年10月10日)はフランスの哲学者で、影響力のある初期の社会主義思想家であり、ユートピア社会主義の創始者の一人である[2]。例えば、フー

リエは1837年にフェミニズムという言葉を生み出したとされている[3]。 フーリエの社会的見解や提案は、意図主義的共同体の運動全体を刺激した。アメリカでは、オハイオ州ユートピア、テキサス州ダラス近郊のラ・レユニオン、イ リノイ州チューリッヒ湖、ニュージャージー州レッドバンクのノースアメリカン・ファランクス、マサチューセッツ州ウェスト・ロックスベリーのブルック・ ファーム、ニューヨーク州のコミュニティ・プレイスとソダス・ベイ・ファランクス、カンザス州シルクヴィルなどがある。フランスのギーズでは、ギーズ・ ファミリス[fr; de; pt]に影響を与えた。フーリエはその後、さまざまな革命思想家や作家に影響を与えた。 |

| Life Fourier was born in Besançon, France, on 7 April 1772.[4] The son of a small businessman, Fourier was more interested in architecture than in his father's trade.[4] He wanted to become an engineer, but the local military engineering school accepted only sons of noblemen.[4] Fourier later said he was grateful that he did not pursue engineering because it would have taken too much time away from his efforts to help humanity.[5] When his father died in 1781, Fourier received two-fifths of his father's estate, valued at more than 200,000 francs.[6] This enabled Fourier to travel throughout Europe at his leisure. In 1791 he moved from Besançon to Lyon, where he was employed by the merchant M. Bousquet.[7] Fourier's travels also brought him to Paris, where he worked as the head of the Office of Statistics for a few months.[4] From 1791 to 1816 Fourier was employed in Paris, Rouen, Lyon, Marseille, and Bordeaux.[8] As a traveling salesman and correspondence clerk, his research and thought was time-limited: he complained of "serving the knavery of merchants" and the stupefaction of "deceitful and degrading duties". He began writing. His first book was published in 1808 but sold few copies. After six years, it fell into the hands of Monsieur Just Muiron, who eventually became Fourier's patron. Fourier produced most of his writings between 1816 and 1821. In 1822, he tried to sell his books again but with no success.[9][self-published source?] Fourier died in Paris in 1837.[7][10] |

生涯 フーリエは1772年4月7日にフランスのブザンソンで生まれた。[4] 小さな商人の息子であったフーリエは、父親の商売よりも建築に興味があった。[4] 彼はエンジニアになりたいと思ったが、地元の軍事工学学校は貴族の息子しか受け入れていなかった。 [4] フーリエは後年、工学の道を志さなかったことを感謝していると述べている。なぜなら、工学の勉強に時間を取られ、人類の救済に専念できなくなったからだと 言う。[5] 1781年に父親が死去すると、フーリエは父親の遺産の5分の2、20万フラン以上の財産を相続した。[6] これにより、フーリエはヨーロッパ中を自由に旅することができるようになった。1791年、彼はベサンソンからリヨンに移り、商人M. ブスクエに雇われた。[7] フーリエの旅は彼をパリにも導き、そこで数ヶ月間統計局の局長を務めた。[4] 1791年から1816年まで、フーリエはパリ、ルーアン、リヨン、マルセイユ、ボルドーで働いた。 [8] 旅の商人兼書簡係として働いていたため、彼の研究と思想は時間的制約を受けていた。彼は「商人の悪事の手先として働くこと」と「欺瞞的で卑劣な職務の麻 痺」を嘆いていた。 彼は執筆を開始した。最初の著作は1808年に刊行されたが、販売部数は少なかった。6年後、その本はムイロン氏の手元に渡り、彼は最終的にフーリエのパ トロンとなった。フーリエは1816年から1821年の間にほとんどの著作を執筆した。1822年、彼は再び本を販売しようとしたが、成功しなかった。 [9][自己出版の出典?] フーリエは1837年にパリで死去した。[7][10] |

| Ideas Fourier declared that concern and cooperation are the keys to social success. He believed that a society that cooperated would see an immense improvement in its productivity. Workers would be recompensed for their labor according to their contribution. Fourier saw such cooperation occurring in communities he called "phalanxes", based upon structures called Phalanstères or "grand hotels". These buildings were four-level apartment complexes where the richest had the uppermost apartments and the poorest had ground-floor residences. Wealth was determined by one's job; jobs were assigned based on interest and desire. There were incentives: jobs people might not enjoy doing would receive higher pay. Fourier considered trade, which he associated with Jews, the "source of all evil", and advocated that Jews be forced to perform farm work in the phalansteries.[11] By the end of his life, Fourier advocated the return of Jews to Palestine with the assistance of the Rothschilds.[12] John K. Roth and Richard L. Rubenstein see Fourier as motivated by economic and religious antisemitism rather than the racial antisemitism that emerged later in the century.[12] |

アイデア フーリエは、社会的成功の鍵は関心と協力にあると宣言した。彼は、協力し合う社会は生産性が飛躍的に向上すると信じていた。労働者はその貢献度に応じて労 働の対価を得ることができる。フーリエは、このような協力が、ファランステール(グランドホテル)と呼ばれる建築物を基礎とした、彼が「ファランクス」と 呼ぶ共同体の中で起こることを考えた。この建物は4階建ての集合住宅で、富裕層は最上階に、貧困層は1階に住んでいた。富は仕事によって決まり、仕事は興 味と欲望に基づいて割り当てられた。人民が楽しくない仕事でも高い給料がもらえるというインセンティブがあった。フーリエは、ユダヤ人と結びついた貿易を 「諸悪の根源」とみなし、ユダヤ人にファランステリでの農作業を強制することを提唱した[11]。フーリエは、その生涯の終わりには、ロスチャイルド家の 援助によるユダヤ人のパレスチナへの帰還を提唱した[12]。ジョン・K・ロスとリチャード・L・ルーベンスタインは、フーリエは、今世紀後半に出現した 人種的反ユダヤ主義ではなく、経済的・宗教的反ユダヤ主義によって動機づけられたと見ている[12]。 |

| Attack on civilization Fourier characterized poverty (not inequality) as the principal cause of disorder in society, and proposed to eradicate it by sufficiently high wages and a "decent minimum" for those unable to work.[13] He used the word "civilization" in a pejorative sense; as such, "Fourier's contempt for the respectable thinkers and ideologies of his age was so intense that he always used the terms philosopher and civilization in a pejorative sense. In his lexicon civilization was a depraved order, a synonym for perfidy and constraint ... Fourier's attack on civilization had qualities not to be found in the writing of any other social critic of his time."[14] |

文明への攻撃 フーリエは貧困(不平等ではない)を社会の無秩序の主な原因とみなし、十分に高い賃金と、働くことのできない人々のための「まともな最低賃金」によって、 貧困を根絶することを提案した[13]。彼は「文明」という言葉を侮蔑的な意味で使用した。彼の辞書では、文明とは堕落した秩序であり、背徳と束縛の代名 詞であった。フーリエの文明に対する攻撃は、同時代の他のどの社会批評家の文章にも見られない性質を持っていた」[14]。 |

| Work and liberated passions For Herbert Marcuse "The idea of libidinal work relations in a developed industrial society finds little support in the tradition of thought, and where such support is forthcoming it seems of a dangerous nature. The transformation of labor into pleasure is the central idea in Fourier's giant socialist utopia."[15]: 217 Fourier insists that this transformation requires a complete change in the social institutions: distribution of the social product according to need, assignment of functions according to individual faculties and inclinations, constant mutation of functions, short work periods, and so on. But the possibility of "attractive labor" (travail attrayant) derives above all from the release of libidinal forces . Fourier assumes the existence of an attraction industrielle which makes for pleasurable co-operation. It is based on the attraction passionnée in the nature of man, which persists despite the opposition of reason, duty, prejudice. This attraction passionnée tends toward three principal objectives: the creation of "luxury, or the pleasure of the five senses"; the formation of libidinal groups (of friendship and love); and the establishment of a harmonious order, organizing these groups for work in accordance with the development of the individual "passions" (internal and external "play" of faculties).[15]: 217 Fourier believed that there were 12 common passions, which resulted in 810 types of character, so the ideal phalanx would have 1,620 people.[16] One day there would be six million of these, loosely ruled by a world "omniarch", or (later) a World Congress of Phalanxes. He had a concern for the sexually rejected; jilted suitors would be led away by a corps of fairies who would soon cure them of their lovesickness, and visitors could consult the card-index of personality types for suitable partners for casual sex. He also defended homosexuality as a personal preference for some people. Anarchist Hakim Bey describes Fourier's ideas as follows: In Fourier's system of Harmony all creative activity including industry, craft, agriculture, etc. will arise from liberated passion—this is the famous theory of "attractive labor". Fourier sexualizes work itself—the life of the Phalanstery is a continual orgy of intense feeling, intellection, & activity, a society of lovers & wild enthusiasts.[17] |

労働と解放された情熱 ヘルベルト・マルクーゼによれば、「先進工業社会におけるリビドー的労働関係の考え方は、思想の伝統にはほとんど支持が見られず、支持が見られる場合でも 危険な性質のもののように見える。労働を快楽に変えることは、フーリエの巨大な社会主義的ユートピアの中心的な考えである」[15]: 217 フーリエは、この変革には社会制度の根本的な変革が必要だと主張している:社会的産物の必要に応じての分配、個人の能力と傾向に応じての役割の割り当て、 役割の継続的な変化、短い労働時間など。しかし、「魅力的な労働」(travail attrayant)の可能性は、何よりもリビドーの力の解放から生じる。フーリエは、協力の喜びを生む「産業的吸引力」の存在を仮定している。これは、 理性、義務、偏見の反対にもかかわらず持続する、人間の性質に内在する「情熱的な吸引力」に基づいている。この情熱的な吸引力は、三つの主要な目標 towards 向かっている:五感の快楽である「贅沢」の創造;リビドー的なグループ(友情と愛のグループ)の形成;そして、個人の「情熱」(内部と外部の「能力の遊 び」)の発展に応じて、これらのグループを労働のために組織化する調和のとれた秩序の確立。[15]: 217 フーリエは、12 の共通の情熱があり、それが 810 種類の性格を生み出していると信じていたため、理想的なファランクスは 1,620 人の人民で構成されることになる。[16] いつの日か、600 万人もの人民が、世界「オムニアーク」または(後に)世界ファランクス会議によって緩やかに統治されることになるだろう。彼は、性的に拒絶された人々にも 関心を持っいた。失恋した求婚者は、妖精たちの集団に連れ去られ、すぐに失恋の痛手を癒やすことができ、訪問者は、カジュアルなセックスの相手を探すため に、性格タイプのカードインデックスを調べることができた。また、彼は、一部の人々の個人的な嗜好として同性愛を擁護した。アナキストのハキム・ベイは、 フーリエの考えを次のように説明している。 フーリエの調和のシステムでは、産業、職人技、農業など、すべての創造的活動は解放された情熱から生まれる——これが有名な「魅力的な労働」の理論だ。 フーリエは労働そのものを性化している——ファランステリーの生活は、激しい感情、知性、活動が絶え間なく続く乱交の宴であり、愛し合う者たちと野生の熱 狂者たちの社会だ。[17] |

| Women's rights Fourier supported women's rights. He believed that all important jobs should be open to women on the basis of skill and aptitude rather than closed on account of gender. He spoke of women as individuals, not as half the human couple. Fourier saw that "traditional" marriage could potentially hurt woman's rights as human beings and thus never married.[18] Writing before the advent of the term "homosexuality", he held that both men and women have a wide range of sexual needs and preferences, which may change throughout their lives, including same-sex attraction and androgénité. He argued that all sexual expressions should be enjoyed as long as people are not abused, and that "affirming one's difference" can actually enhance social integration.[19] Fourier's concern was to liberate every human being, in two senses: through education and by liberating human passion.[20] |

女性の権利 フーリエは女性の権利を支持した。彼は、重要な仕事は性別によって閉ざされるのではなく、技能や適性に基づいて女性に開かれるべきだと考えていた。彼は、 女性を人間の半分ではなく、個人として捉えていた。フーリエは、「伝統的な」結婚が女性の権利を侵害する可能性があると見なし、結婚しなかった。[18] 「同性愛」という用語が生まれる前に、彼は男性も女性も、人生を通じて変化する可能性のある多様な性的欲求や嗜好を持ち、その中には同性愛やアンドロジェ ニテ(両性具有)も含まれると主張した。彼は、人々が虐待されない限り、あらゆる性的表現は享受されるべきであり、「自分の違いを肯定すること」は、実際 には社会的統合を促進すると主張した[19]。 フーリエの関心は、教育と人間の情熱の解放という 2 つの意味で、すべての人間を解放することだった[20]。 |

| Children and education Fourier felt that "civilized" parents and teachers saw children as little idlers.[21] But he himself believed that children as early as age two and three were very industrious. He listed children's dominant tastes as including: Rummaging or inclination to handle everything, examine everything, look through everything, to constantly change occupations; Industrial commotion, taste for noisy occupations; Aping or imitative mania. Industrial miniature, a taste for miniature workshops. Progressive attraction of the weak toward the strong.[21] |

子供と教育 フーリエは、「文明化された」親や教師は子供たちを怠け者だと見なしていたと述べている[21]。しかし、彼自身は、2、3歳の子供たちは非常に勤勉であると信じていた。彼は、子供たちの主な嗜好として、次のようなものを挙げている。 あらゆるものを手当たり次第に探したり、調べたり、見たり、絶えず職業を変えたがる傾向。 騒々しい職業を好む、騒々しい職業への嗜好。 模倣や模倣の熱中。 工業的なミニチュア、ミニチュア工房への嗜好。 弱いものから強いものへの段階的な吸引。[21] |

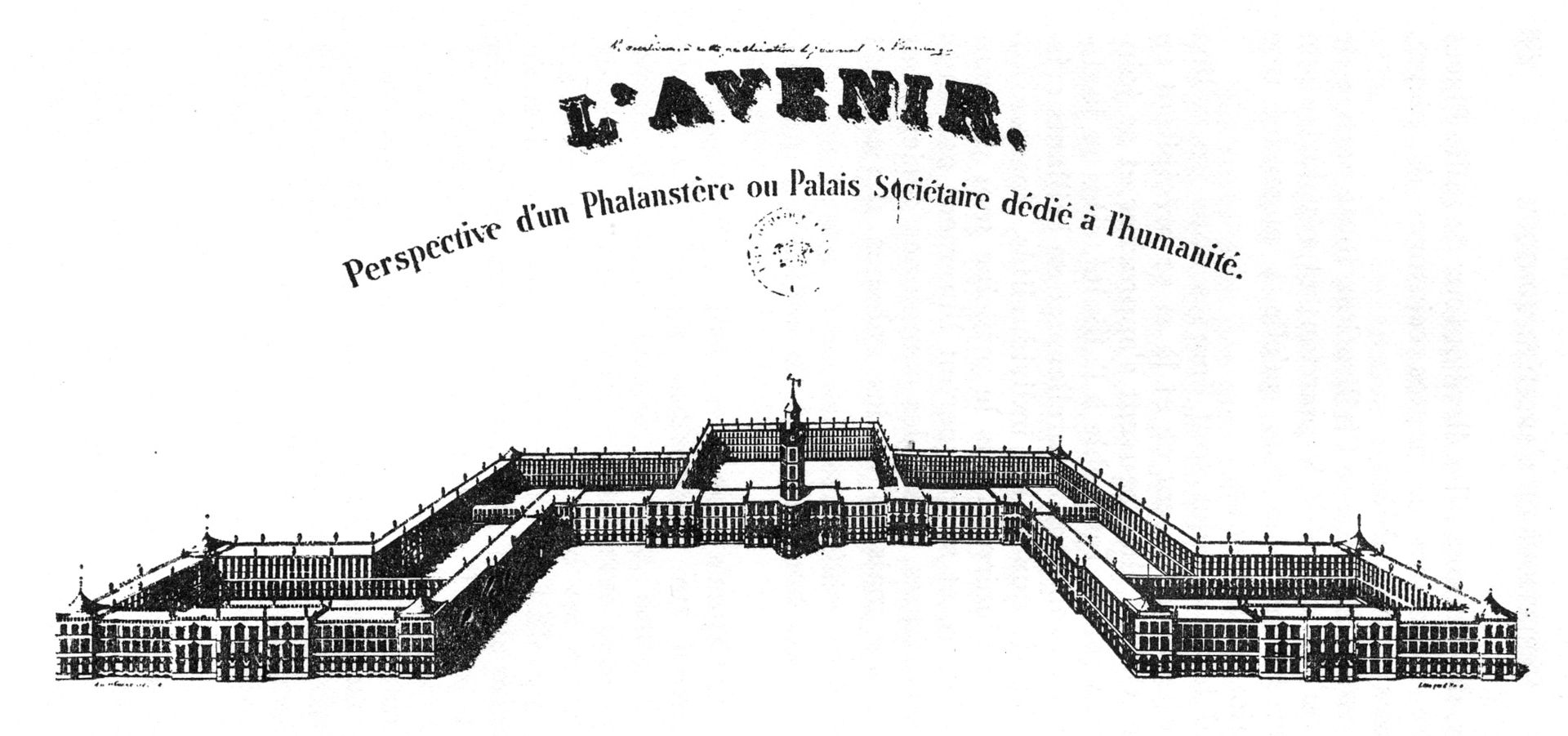

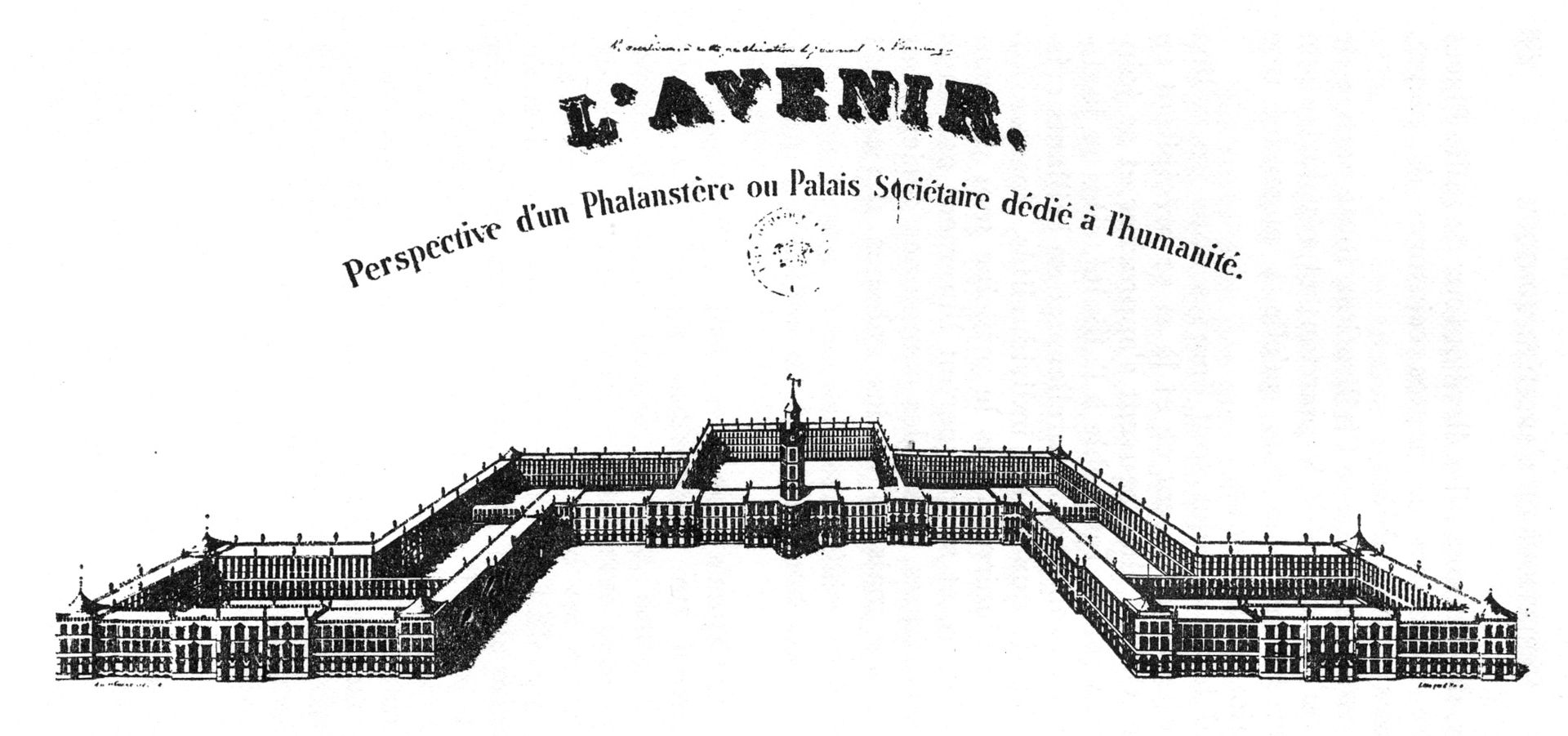

| Utopian aspirations Fourier was deeply disturbed by the disorder of his time and wanted to stabilize the course of events. He saw a world full of strife, chaos, and disorder.[22] Fourier is best remembered for his writings on a new world order based on unity of action and harmonious collaboration.[4] He is also known for certain utopian pronouncements, such as that the seas would lose their salinity and turn to lemonade,[23] and a coincidental view of climate change,[24] that the North Pole would be milder than the Mediterranean in a future phase of Perfect Harmony.[21][25][failed verification]  Perspective view of Fourier's Phalanstère |

ユートピア的理想 フーリエは、当時の混乱に深く悩まされ、事態の安定化を切望していた。彼は、争い、混沌、混乱に満ちた世界を見ていた[22]。 フーリエは、行動の統一と調和のとれた協力に基づく新しい世界秩序に関する著作で最もよく知られている。 [4] また、海が塩分を失ってレモネードに変わる[23] といったユートピア的な主張や、気候変動に関する偶然の一致した見解[24](完璧な調和の段階に達した未来には、北極は地中海よりも温暖になる)でも知 られている。[21][25][検証失敗]  フーリエのファランステールの透視図 |

| Antisemitism See also: Antisemitism Fourier said Jews were "the leprosy and the ruin of the body politic".[26] He criticized the government for being weak and "prostrate" when confronted with what he called a "secret and indissoluble league" of Jews. Post-Medieval antisemitic rhetoric often accused Jews of being unable to assimilate into a unitary national culture (highly valued by the French nationalists). Fourier was one of the writers to argue that Jews were disloyal and would not make good French citizens. Like others, he placed great significance on the religious restrictions prohibiting Jews from eating at the same table as non-Jews:[27] he confined himself to sitting down at table and drinking; he refused to eat any of the dishes, because they were prepared by Christians. Christians have to be very patient to tolerate such impertinence. In the Jewish religion it denotes a system of defiance and aversion for other sects. Now, does a sect which wishes to carry its hatred as far as the table of its protectors, deserve to be protected? |

反ユダヤ主義 関連項目:反ユダヤ主義 フーリエは、ユダヤ人は「政治の体におけるハンセン病であり、破滅である」と述べた[26]。彼は、ユダヤ人の「秘密の、そして不可分な同盟」と彼が呼ん だものに対して、政府が弱く「屈服している」と批判した。中世以降の反ユダヤ主義のレトリックは、ユダヤ人が(フランスのナショナリストたちが高く評価す る)単一の国民文化に同化できないと非難することが多かった。フーリエは、ユダヤ人は不忠実で良きフランス国民にはなれないと主張した作家の一人だった。 他の者たちと同様、彼は、ユダヤ人が非ユダヤ人と同じ食卓で食事をするのを禁じる宗教的制限を非常に重要視していた[27]。 彼はテーブルに着席し、飲むことだけに留まり、料理を食べることを拒否した。なぜなら、それらの料理はキリスト教徒によって調理されたものだったからだ。 キリスト教徒は、このような無礼を耐えるために非常に忍耐強くなければならない。ユダヤ教では、これは他の宗派に対する反抗と嫌悪のシステムを意味する。 では、保護者の食卓にまで憎しみを持ち込む宗派が、保護に値するだろうか? |

| The

influence of Fourier's ideas in French politics carried forward into

the 1848 Revolution and the Paris Commune by followers such as Victor

Considerant. Numerous references to Fourierism appear in Dostoevsky's political novel Demons, published in 1872.[28] Fourier's ideas also took root in America, with his followers starting phalanxes throughout the country, including one of the most famous, Utopia, Ohio. Fourier is one of three major utopian socialists whose ideas are critiqued in Friedrich Engels's Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Peter Kropotkin, in the preface to his book The Conquest of Bread, considered Fourier the founder of the libertarian branch of socialist thought, as opposed to the authoritarian socialist ideas of Babeuf and Buonarroti.[29] In the mid-20th century, Fourier's influence began to rise again among writers reappraising socialist ideas outside the Marxist mainstream. After the Surrealists broke with the French Communist Party, André Breton returned to Fourier, writing Ode à Charles Fourier in 1947. Walter Benjamin considered Fourier crucial enough to devote an entire "konvolut" of his massive, projected book on the Paris arcades, the Passagenwerk, to Fourier's thought and influence. He writes: "To have instituted play as the canon of a labor no longer rooted in exploitation is one of the great merits of Fourier", and notes that "Only in the summery middle of the nineteenth century, only under its sun, can one conceive of Fourier's fantasy materialized."[30] Herbert Marcuse in his influential work Eros and Civilization wrote, "Fourier comes closer than any other utopian socialist to elucidating the dependence of freedom on non-repressive sublimation."[15]: 218 In 1969, Raoul Vaneigem quoted and adapted Fourier's Avis aux civilisés relativement à la prochaine métamorphose sociale in his text Avis aux civilisés relativement à l'autogestion généralisée.[31]  North American Phalanx building in New Jersey Fourier's work significantly influenced the writings of Gustav Wyneken, Guy Davenport (in his work of fiction Apples and Pears), Peter Lamborn Wilson, and Paul Goodman.[citation needed] In Whit Stillman's film Metropolitan, the idealistic Tom Townsend describes himself as a Fourierist, and debates the success of social experiment Brook Farm with another character. Bidding him goodnight, Sally Fowler says, "Good luck with your furrierism." [sic] David Harvey, in the appendix to his book Spaces of Hope, offers a personal utopian vision of the future in cities citing Fourier's ideas. Libertarian socialist and environmentalist thinker Murray Bookchin wrote that "The Greek ideal of the rounded citizen in a rounded environment—one that reappeared in Charles Fourier's utopian works—was long cherished by the anarchists and socialists of the last century...The opportunity of the individual to devote his or her productive activity to many different tasks over an attenuated work week (or in Fourier's ideal society, over a given day) was seen as a vital factor in overcoming the division between manual and intellectual activity, in transcending status differences that this major division of work created, and in enhancing the wealth of experiences that came with a free movement from industry through crafts to food cultivation."[32] Nathaniel Hawthorne in Chapter 7 of his novel The Blithedale Romance gently mocks Fourier, writing: "When, as a consequence of human improvement", said I, "the globe shall arrive at its final perfection, the great ocean is to be converted into a particular kind of lemonade, such as was fashionable at Paris in Fourier's time. He calls it limonade a cedre. It is positively a fact! Just imagine the city docks filled, every day, with a flood tide of this delectable beverage![33] Writers of the post-left anarchy tendency have praised Fourier's work. Bob Black in his work The Abolition of Work advocates Fourier's idea of attractive work as a solution to his criticisms of work conditions in contemporary society.[34] Hakim Bey wrote that Fourier "lived at the same time as De Sade & [William] Blake, & deserves to be remembered as their equal or even superior. Those other two apostles of freedom & desire had no political disciples, but in the middle of the 19th century literally hundreds of communes (phalansteries) were founded on fourierist principles".[17] |

フーリエの思想は、ヴィクトル・コンシデランなどの追随者たちによって、1848年の革命やパリ・コミューンにも影響を与えた。 1872年に出版されたドストエフスキーの政治小説『悪霊』には、フーリエ主義に関する言及が数多く見られる[28]。 フーリエの思想はアメリカにも根付き、その追随者たちは全国にファランクスを設立し、その中でも最も有名なものの一つがオハイオ州の「ユートピア」だ。 フーリエは、フリードリヒ・エンゲルスの『社会主義:空想的社会主義と科学的社会主義』で批判された3人の主要なユートピア的社会主義者の一人だ。 ピーター・クロポトキンは、自身の著書『パンの征服』の序文で、フーリエをバブーフやブオナロッティの権威主義的社会主義思想に対抗する、社会主義思想の自由主義派の創始者と位置付けた。[29] 20世紀半ば、マルクス主義の主流から離れた社会主義思想の再評価が進む中で、フーリエの影響力が再び高まり始めた。シュルレアリストたちがフランス共産党と決別した後、アンドレ・ブルトンはフーリエに戻り、1947年に『シャルル・フーリエへの賛歌』を執筆した。 ウォルター・ベンヤミンは、フーリエを極めて重要視し、パリのアーケードに関する大規模な未完の著作『パサージュ作品』において、フーリエの思想と影響に 「コンヴォルート」と呼ばれる一章を捧げた。彼は次のように書いている:「搾取に根ざさない労働の規範として遊びを確立したことは、フーリエの大きな功績 の一つだ」と指摘し、「19世紀の夏の真ん中、その太陽の下でしか、フーリエの幻想が現実化した姿を想像することはできない」と述べている。[30] ヘルベルト・マルクーゼは、影響力のある著作『エロスと文明』で、「フーリエは、自由が抑圧的な昇華に依存していることを明らかにした点で、他のどのユートピア的社会主義者よりも近い」と書いている。[15]: 218 1969年、ラウル・ヴァネイグは、彼の著作『Avis aux civilisés relativement à l'autogestion généralisée』の中で、フーリエの『Avis aux civilisés relativement à la prochaine métamorphose sociale』を引用し、改変した。  ニュージャージー州にある北米ファランクスビル フーリエの著作は、グスタフ・ワイネケン、ガイ・ダベンポート(小説『リンゴと梨』)、ピーター・ランボーン・ウィルソン、ポール・グッドマンの著作に大きな影響を与えた。 ウィット・スティルマンの映画『メトロポリタン』では、理想主義者のトム・タウンゼントが、自分自身をフーリエ主義者だと表現し、別の登場人物と社会実験 「ブルック・ファーム」の成功について議論している。サリー・ファウラーは、彼に「おやすみなさい」と別れを告げながら、「あなたの毛皮主義が成功します ように」と付け加える。 デヴィッド・ハーヴェイは、著書『希望の空間』の付録で、フーリエの思想を引用して、都市の未来に関する個人的なユートピア的ビジョンを提示している。 リバタリアン社会主義者であり、環境保護思想家のマレー・ブックチンは、「丸い環境の中で丸く成長した市民というギリシャの理想は、シャルル・フーリエの ユートピア作品にも再び登場し、前世紀のアナキストや社会主義者たちに長く愛されてきた」と書いている。 個人が、短縮された労働時間(フーリエの理想社会では 1 日)の中で、さまざまな仕事に生産的な活動を捧げる機会は、肉体労働と頭脳労働の分業を克服し、この大きな分業によって生じた地位の差を乗り越え、産業か ら工芸、食糧生産に至るまで自由に移動することで得られる豊かな経験を深める上で、重要な要素であると見なされていた」[32]。 ナサニエル・ホーソーンは、小説『ブライトデール・ロマンス』の第7章で、フーリエを優しく嘲笑して次のように書いている: 「人間の進歩の結果として、地球が最終的な完成に達すると、大海洋は、フーリエの時代にパリで流行した、ある種のレモネードに変貌するだろう。彼はそれを 「リモネード・ア・セドル」と呼んでいる。これは事実だ!毎日、このおいしい飲み物が、都市の埠頭に溢れかえる様子を想像してみてください!」[33] ポスト・レフトの無政府主義傾向の作家たちはフーリエの著作を称賛している。ボブ・ブラックは『労働の廃止』において、現代社会の労働条件への批判に対す る解決策として、フーリエの「魅力的な労働」のアイデアを提唱している。[34] ハキム・ベイは、フーリエは「サドと[ウィリアム]・ブレイクと同時代の人物であり、彼らと同等か、あるいはそれ以上の存在として記憶されるに値する」と 書いている。あの二人の自由と欲望の使徒には政治的な弟子はいなかったが、19世紀半ばには、フーリエ主義の原則に基づいて文字通り数百のコミューン (ファランステール)が設立された」と書いている。[17] |

| Fourier's works Fourier, Charles. Théorie des quatre mouvements et des destinées générales (Theory of the four movements and the general destinies), appeared anonymously in Lyon in 1808.[35] Fourier, Charles. Le Nouveau Monde amoureux. Written 1816–18, not published widely until 1967. Fourier, Ch. Œuvres complètes de Ch. Fourier. 6 tomes. Paris: Librairie Sociétaire, 1841-1848. Fourier, Charles. La fausse industrie morcelée, répugnante, mensongère, et l'antidote, l'industrie naturelle, combinée, attrayante, véridique, donnant quadruple produit (False Industry, Fragmented, Repugnant, Lying and the Antidote, Natural Industry, Combined, Attractive, True, giving four times the product), Paris: Bossange. 1835. Fourier, Charles. Oeuvres complètes de Charles Fourier. 12 vols. Paris: Anthropos, 1966–1968. Jones, Gareth Stedman, and Ian Patterson, eds. Fourier: The Theory of the Four Movements. Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1996. Fourier, Charles. Design for Utopia: Selected Writings. Studies in the Libertarian and Utopian Tradition. New York: Schocken, 1971. ISBN 0-8052-0303-6 Poster, Mark, ed. Harmonian Man: Selected Writings of Charles Fourier. Garden City: Doubleday. 1971. Beecher, Jonathan and Richard Bienvenu, eds. The Utopian Vision of Charles Fourier: Selected Texts on Work, Love, and Passionate Attraction. Boston: Beacon Press, 1971. Wilson, Peter Lamborn, Escape from the Nineteenth Century and Other Essays. Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 1998. |

フーリエの著作 フーリエ、シャルル。『四つの運動と一般的な運命の理論』(Théorie des quatre mouvements et des destinées générales)は、1808年にリヨンで匿名で出版された。[35] フーリエ、シャルル。『新しい愛の世界』(Le Nouveau Monde amoureux)。1816年から18年に執筆され、1967年まで広く出版されなかった。 フーリエ、Ch. Œuvres complètes de Ch. Fourier(Ch. フーリエ全集)。6巻。パリ:Librairie Sociétaire、1841-1848年。 フーリエ、シャルル。『La fausse industrie morcelée, répugnante, mensongère, et l'antidote, l'industrie naturelle, combinée, attrayante, véridique, donnant quadruple produit』(『偽りの産業、断片化され、嫌悪感を抱かせる、虚偽の産業と、その解毒剤、自然産業、統合され、魅力的で、真実の産業、四倍の生産をも たらす』)、パリ:ボサンジュ、1835年。 フーリエ、シャルル. 『シャルル・フーリエ全集』. 12巻. パリ:アントロポス, 1966–1968. ジョーンズ、ガレス・ステッドマン、およびイアン・パターソン編. 『フーリエ:四つの運動の理論』. ケンブリッジ政治思想史テキスト. ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局, 1996. フーリエ、シャルル。『ユートピアの設計:選集』 『リバタリアンとユートピアの伝統の研究』 ニューヨーク:Schocken、1971 年。ISBN 0-8052-0303-6 ポスター、マーク編。『ハーモニアマン:シャルル・フーリエの選集』 ガーデンシティ:Doubleday、1971 年。 ビーチャー、ジョナサン、リチャード・ビエンヴニュ編。シャルル・フーリエのユートピア的ビジョン:仕事、愛、そして情熱的な魅力に関する選集。ボストン:ビーコンプレス、1971年。 ウィルソン、ピーター・ラムボーン、19世紀からの脱出およびその他のエッセイ。ブルックリン:オートノメディア、1998年。 |

| Alphadelphia Association Alphonse Toussenel, a disciple of Fourier American Union of Associationists Brook Farm Decent work List of Fourierist Associations in the United States Society of the Friends of Truth |

アルファデラフィア協会 フーリエの弟子、アルフォンス・トゥッセンネル アメリカ連合協会 ブルック・ファーム 適切な労働 アメリカ合衆国のフーリエ主義者協会一覧 真実の友協会 |

| Sources ‹See TfM›Cunliffe, J (2001). "The Enigmatic Legacy of Charles Fourier: Joseph Charlier and Basic Income", History of Political Economy, vol.33, No. 3. ‹See TfM›Denslow, V (1880). Modern Thinkers Principally Upon Social Science: What They Think, and Why, Chicago, 1880. ‹See TfM›Goldstein, L (1982). "Early Feminist Themes in French Utopian Socialism: The St.-Simonians and Fourier", Journal of the History of Ideas, vol.43, No. 1. Hawthorne, Nathaniel (1852). The Blithedale romance. New York: A.L. Burt Co. ISBN 978-0-393-09150-2. OCLC 697899845. OL 7197432M – via Internet Archive. ‹See TfM›Pellarin, C (1846). The Life of Charles Fourier, New York, 1846.Internet Archive Retrieved November 25, 2007 ‹See TfM›Serenyi, P (1967). "Le Corbusier, Fourier, and the Monastery of Ema", The Art Bulletin, vol.49, No. 4. |

出典 ‹TfM を参照›Cunliffe, J (2001). 「シャルル・フーリエの謎めいた遺産:ジョセフ・シャルリエとベーシック・インカム」『政治経済史』第 33 巻、第 3 号。 ‹TfM を参照›Denslow, V (1880). 『社会科学に関する現代思想家たち:彼らの考えとその理由』シカゴ、1880 年。 ‹TfMを参照›Goldstein, L (1982). 「フランス空想社会主義における初期のフェミニズムのテーマ:サン=シモン派とフーリエ」, Journal of the History of Ideas, vol.43, No. 1. ホーソーン、ナサニエル (1852). 『ブリスデール・ロマンス』. ニューヨーク: A.L. Burt Co. ISBN 978-0-393-09150-2. OCLC 697899845. OL 7197432M – インターネットアーカイブ経由. ‹TfMを参照›ペラリン、C(1846)。『シャルル・フーリエの生涯』、ニューヨーク、1846年。インターネットアーカイブ 2007年11月25日取得 ‹TfMを参照›セレンイ、P(1967)。「ル・コルビュジエ、フーリエ、そしてエマ修道院」、『アート・ブルテン』、第49巻、第4号。 |

| Further reading On Fourier and his works Beecher, Jonathan (1986). Charles Fourier: the visionary and his world. Berkeley: U of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05600-0. Burleigh, Michael (2005). Earthly powers : the clash of religion and politics in Europe from the French Revolution to the Great War. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-058093-3. Calvino, Italo (1986). The Uses of Literature. San Diego: Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 0-15-693250-4. pp. 213–255 Lloyd-Jones, I D."Charles Fourier, The Realistic Visionary " History Today 12#1 (1962): pp198–205. « Portrait : Charles Fourier (1772-1837) ». La nouvelle lettre, n°1070 (12 mars 2011): 8. On Fourierism and his posthumous influence Barthes, Roland Sade Fourier Loyola. Paris: Seuil, 1971. Bey, Hakim (1991). "The Lemonade Ocean & Modern Times". Retrieved January 16, 2017. Brock, William H. Phalanx on a Hill: Responses to Fourierism in the Transcendentalist Circle. Diss., Loyola U Chicago, 1996. Buber, Martin (1996). Paths in Utopia. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-0421-1. Davis, Philip G. (1998). Goddess unmasked : the rise of neopagan feminist spirituality. Dallas, Tex.: Spence Pub. ISBN 0-9653208-9-8. Desroche, Henri. La Société festive. Du fouriérisme écrit au fouriérismes pratiqués. Paris: Seuil, 1975. Engels, Frederick. Anti-Dühring. 25:1-309. Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. Karl Marx, Frederick Engels: Collected Works [MECW]. 46 vols. to date. Moscow: Progress, 1975. Guarneri, Carl J. (1991). The utopian alternative : Fourierism in nineteenth-century America. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2467-4. Heider, Ulrike (1994). Anarchism : left, right, and green. San Francisco: City Lights Books. ISBN 0-87286-289-5. Kolakowski, Leszek (1978). Main Currents of Marxism: The Founders. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-824547-5. Jameson, Fredric. "Fourier; or; Ontology and Utopia" at Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions. London & New York: Verso. 2005. |

さらに読む フーリエとその作品について ビーチャー、ジョナサン(1986)。『シャルル・フーリエ:先見の明のある人物とその世界』。バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版。ISBN 0-520-05600-0。 バーリー、マイケル(2005)。『地上の権力:フランス革命から第一次世界大戦までのヨーロッパにおける宗教と政治の衝突』。ニューヨーク:ハーパーコリンズ出版社。ISBN 0-06-058093-3。 カルヴィーノ、イタロ(1986)。『文学の用途』。サンディエゴ:ハーコート・ブレス・アンド・カンパニー。ISBN 0-15-693250-4。213–255 ページ ロイド=ジョーンズ、I・D.「シャルル・フーリエ、現実的な夢想家」『ヒストリー・トゥデイ』12号1(1962年):pp198–205。 「肖像:シャルル・フーリエ(1772-1837)」『ラ・ヌーヴェル・レター』第1070号(2011年3月12日):8。 フーリエ主義とその死後の影響について バルト、ロラン サド・フーリエ・ロヨラ。パリ:Seuil、1971年。 ベイ、ハキム (1991)。「レモネードの海と現代」。2017年1月16日取得。 ブロック、ウィリアム・H. 丘の上のファランクス:超越主義者サークルにおけるフーリエ主義への反応。論文、ロヨラ大学シカゴ、1996年。 ブーバー、マーティン (1996)。『ユートピアへの道』。ニューヨーク州シラキュース:シラキュース大学出版。ISBN 0-8156-0421-1。 デイヴィス、フィリップ G. (1998)。『女神の仮面の正体:新異教フェミニストの精神性の台頭』。テキサス州ダラス:スペンス出版。ISBN 0-9653208-9-8。 デロッシュ、アンリ。La Société festive. Du fouriérisme écrit au fouriérismes pratiqués. パリ:Seuil、1975年。 エンゲルス、フリードリッヒ。Anti-Dühring. 25:1-309.マルクス、カール、およびフリードリッヒ・エンゲルス。カール・マルクス、フリードリッヒ・エンゲルス:全集 [MECW]。46巻。現在まで。モスクワ:Progress、1975年。 グアルネリ、カール・J. (1991). 『ユートピアの代替案:19 世紀アメリカのフーリエ主義』. ニューヨーク州イサカ:コーネル大学出版局。ISBN 0-8014-2467-4。 ハイダー、ウルリケ(1994)。『アナキズム:左、右、そしてグリーン』。サンフランシスコ:シティ・ライツ・ブックス。ISBN 0-87286-289-5。 コラコフスキー、レシェク(1978)。『マルクス主義の主要潮流:創始者たち』。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 0-19-824547-5。 ジェイムソン、フレデリック。「フーリエ、あるいは存在論とユートピア」『未来の考古学:ユートピアと呼ばれる欲望とその他のサイエンス・フィクション』所収。ロンドンおよびニューヨーク:ヴェルソ。2005年。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Fourier |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆