論証理論

Argumentation theory

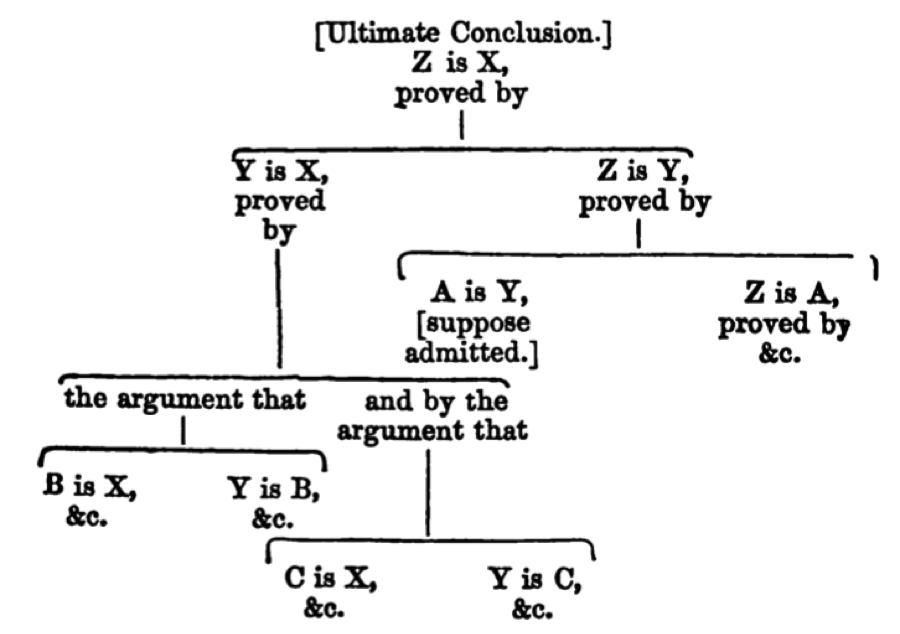

Example

of an early argument map, from Richard Whately's Elements of Logic

(1852 edition)

☆

論証理論(Argumentation theory)とは、前提が論理的推論を通じて結論を支持または弱体化させる仕組みを学際的に研究する学問である。その歴史的起源は論理学、弁証法、修辞学にあ

り、市民的討論、対話、会話、説得の技法と科学を含む。人工的環境と現実世界の両方で、推論規則、論理、手続き規則を研究する。[1][2]

議論には、共同意思決定手続きに関わる熟議や交渉など様々な対話形式が含まれる。[3]

また、相手に対する勝利を主目的とする社会討論の一分野である論争的対話や、教育に用いられる教示的対話も包含する。[2]

この学問は、人民が意見の相違を表明し、合理的に解決、あるいは少なくとも管理する手段についても研究する。[4]

議論は日常的に発生する現象であり、公の討論、科学、法廷などがその例である。[5]

法廷では、裁判官、当事者、検察官が証拠の提示と有効性の検証を行う際に議論が行われる。また、議論の研究者は、組織内の行為者が非合理的に下した決定を

正当化しようとする事後合理化も研究対象とする。

議論は、説明、描写、叙述と並ぶ四つの修辞的様式(言説様式とも呼ばれる)の一つである。

| Argumentation theory

is the interdisciplinary study of how conclusions can be supported or

undermined by premises through logical reasoning. With historical

origins in logic, dialectic, and rhetoric, argumentation theory

includes the arts and sciences of civil debate, dialogue, conversation,

and persuasion. It studies rules of inference, logic, and procedural

rules in both artificial and real-world settings.[1][2] Argumentation includes various forms of dialogue such as deliberation and negotiation which are concerned with collaborative decision-making procedures.[3] It also encompasses eristic dialogue, the branch of social debate in which victory over an opponent is the primary goal, and didactic dialogue used for teaching.[2] This discipline also studies the means by which people can express and rationally resolve or at least manage their disagreements.[4] Argumentation is a daily occurrence, such as in public debate, science, and law.[5] For example in law, in courts by the judge, the parties and the prosecutor, in presenting and testing the validity of evidences. Also, argumentation scholars study the post hoc rationalizations by which organizational actors try to justify decisions they have made irrationally. Argumentation is one of four rhetorical modes (also known as modes of discourse), along with exposition, description, and narration. |

論証理論とは、前提が論理的推論を通じて結論を支持または弱体化させる

仕組みを学際的に研究する学問である。その歴史的起源は論理学、弁証法、修辞学にあり、市民的討論、対話、会話、説得の技法と科学を含む。人工的環境と現

実世界の両方で、推論規則、論理、手続き規則を研究する。[1][2] 議論には、共同意思決定手続きに関わる熟議や交渉など様々な対話形式が含まれる。[3] また、相手に対する勝利を主目的とする社会討論の一分野である論争的対話や、教育に用いられる教示的対話も包含する。[2] この学問は、人民が意見の相違を表明し、合理的に解決、あるいは少なくとも管理する手段についても研究する。[4] 議論は日常的に発生する現象であり、公の討論、科学、法廷などがその例である。[5] 法廷では、裁判官、当事者、検察官が証拠の提示と有効性の検証を行う際に議論が行われる。また、議論の研究者は、組織内の行為者が非合理的に下した決定を 正当化しようとする事後合理化も研究対象とする。 議論は、説明、描写、叙述と並ぶ四つの修辞的様式(言説様式とも呼ばれる)の一つである。 |

| Key components of argumentation Some key components of argumentation are: Understanding and identifying arguments, either explicit or implied, and the goals of the participants in the different types of dialogue. Identifying the premises from which conclusions are derived. Establishing the "burden of proof" – determining who made the initial claim and is thus responsible for providing evidence why their position merits acceptance. For the one carrying the "burden of proof", the advocate, to marshal evidence for their position in order to convince or force the opponent's acceptance. The method by which this is accomplished is producing valid, sound, and cogent arguments, devoid of weaknesses, and not easily attacked. In a debate, fulfillment of the burden of proof creates a burden of rejoinder. One must try to identify faulty reasoning in the opponent's argument, to attack the reasons/premises of the argument, to provide counterexamples if possible, to identify any fallacies, and to show why a valid conclusion cannot be derived from the reasons provided for their argument. For example, consider the following exchange, illustrating the No true Scotsman fallacy: Argument: "No Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge." Reply: "But my friend Angus, who is a Scotsman, likes sugar with his porridge." Rebuttal: "Well perhaps, but no true Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge." In this dialogue, the proposer first offers a premise, the premise is challenged by the interlocutor, and so the proposer offers a modification of the premise, which is designed only to evade the challenge provided. |

議論の主要な構成要素 議論の主要な構成要素は以下の通りである: 明示的または暗示的な議論を理解し特定すること、そして異なる対話形態における参加者の目的を把握すること。 結論が導かれる前提条件を特定すること。 「立証責任」を確立すること――誰が最初に主張したのかを決定し、したがって自らの立場が受け入れられるに値する理由を示す証拠を提供する責任を負う者を特定すること。 「立証責任」を負う側、すなわち主張者は、自らの立場を支持する証拠を提示し、相手を説得または強制的に受け入れさせる必要がある。これを達成する方法は、弱点がなく、容易に反駁されない、妥当で、論理的かつ説得力のある議論を展開することである。 討論において、立証責任の履行は反論責任を生む。相手側の論証における誤った推論を特定し、その論証の根拠/前提を攻撃し、可能であれば反例を示し、あらゆる誤謬を指摘し、提示された根拠から有効な結論が導き出せない理由を示す必要がある。 例えば、以下のやり取りは「真のスコットランド人詭弁」を例示している: 主張:「真のスコットランド人はオートミールに砂糖をかけない」 反論:「でも、スコットランド人の友人アンガスは、お粥に砂糖をかけるのが好きだ」 再反論:「まあそうかもしれないが、真のスコットランド人はお粥に砂糖をかけない」 この対話では、主張者がまず前提を提示し、対話者がその前提に異議を唱える。すると主張者は、提示された異議を回避するためだけに設計された前提の修正案を提示する。 |

| Internal structure of arguments This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Typically an argument has an internal structure, comprising the following: 1. a set of assumptions or premises, 2. a method of reasoning or deduction, and 3. a conclusion or point. An argument has one or more premises and one conclusion. Often classical logic is used as the method of reasoning so that the conclusion follows logically from the assumptions or support. One challenge is that if the set of assumptions is inconsistent then anything can follow logically from inconsistency. Therefore, it is common to insist that the set of assumptions be consistent. It is also good practice to require the set of assumptions to be the minimal set, with respect to set inclusion, necessary to infer the consequent. Such arguments are called MINCON arguments, short for minimal consistent. Such argumentation has been applied to the fields of law and medicine. A non-classical approach to argumentation investigates abstract arguments, where 'argument' is considered a primitive term, so no internal structure of arguments is taken into account.[citation needed] |

議論の内部構造 この節は出典を一切示していない。信頼できる出典を引用してこの節を改善してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。(2023年6月)(このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) 議論は通常、以下の要素からなる内部構造を持つ: 1. 一連の前提または前提条件、 2. 推論または演繹の方法、 3. 結論または主張。 議論は一つ以上の前提と一つの結論を持つ。 多くの場合、古典論理が推論の方法として用いられる。これにより結論は前提や支持から論理的に導かれる。一つの課題は、前提の集合が矛盾している場合、論 理的に何であれ矛盾から導き出せる点だ。したがって、前提の集合が矛盾しないことを要求するのが一般的である。また、前提の集合が、後件を推論するために 集合包含に関して最小限の集合であることを要求するのも良い慣行である。このような議論はMINCON議論(最小限の一貫性を意味する)と呼ばれる。この ような議論法は法学や医学の分野に応用されてきた。 非古典的な議論法へのアプローチは、抽象的な議論を調査する。ここで「議論」は原始的な用語と見なされるため、議論の内部構造は考慮されない。[出典が必要] |

| Types of dialogue In its most common form, argumentation involves an individual and an interlocutor or opponent engaged in dialogue, each contending differing positions and trying to persuade each other, but there are various types of dialogue:[6] Persuasion dialogue aims to resolve conflicting points of view of different positions. Negotiation aims to resolve conflicts of interests by cooperation and dealmaking. Inquiry aims to resolve general ignorance by the growth of knowledge. Deliberation aims to resolve a need to take action by reaching a decision. Information seeking aims to reduce one party's ignorance by requesting information from another party that is in a position to know something. Eristic aims to resolve a situation of antagonism through verbal fighting. |

対話の種類 最も一般的な形では、議論とは個人と対話者または相手方が対話を行い、それぞれが異なる立場を主張し互いを説得しようとするものである。しかし対話には様々な種類がある:[6] 説得的対話は、異なる立場の対立する見解を解決することを目的とする。 交渉は、協力と取引によって利害の対立を解決することを目的とする。 探究は、知識の増進によって一般的な無知を解消することを目指す。 熟議は、決定を下すことで行動の必要性を解消することを目指す。 情報探索は、何かを知っている立場にある相手から情報を求めることで、一方の無知を減らすことを目指す。 論争的対話は、言葉による争いを通じて敵対的な状況を解消することを目指す。 |

| Argumentation and the grounds of knowledge Argumentation theory had its origins in foundationalism, a theory of knowledge (epistemology) in the field of philosophy. It sought to find the grounds for claims in the forms (logic) and materials (factual laws) of a universal system of knowledge. The dialectical method was made famous by Plato and his use of Socrates critically questioning various characters and historical figures. But argument scholars gradually rejected Aristotle's systematic philosophy and the idealism in Plato and Kant. They questioned and ultimately discarded the idea that argument premises take their soundness from formal philosophical systems. The field thus broadened.[7] One of the original contributors to this trend was the philosopher Chaïm Perelman, who together with Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca introduced the French term la nouvelle rhetorique in 1958 to describe an approach to argument which is not reduced to application of formal rules of inference. Perelman's view of argumentation is much closer to a juridical one, in which rules for presenting evidence and rebuttals play an important role. Karl R. Wallace's seminal essay, "The Substance of Rhetoric: Good Reasons" in the Quarterly Journal of Speech (1963) 44, led many scholars to study "marketplace argumentation" – the ordinary arguments of ordinary people. The seminal essay on marketplace argumentation is Ray Lynn Anderson's and C. David Mortensen's "Logic and Marketplace Argumentation" Quarterly Journal of Speech 53 (1967): 143–150.[8][9] This line of thinking led to a natural alliance with late developments in the sociology of knowledge.[10] Some scholars drew connections with recent developments in philosophy, namely the pragmatism of John Dewey and Richard Rorty. Rorty has called this shift in emphasis "the linguistic turn". In this new hybrid approach argumentation is used with or without empirical evidence to establish convincing conclusions about issues which are moral, scientific, epistemic, or of a nature in which science alone cannot answer. Out of pragmatism and many intellectual developments in the humanities and social sciences, "non-philosophical" argumentation theories grew which located the formal and material grounds of arguments in particular intellectual fields. These theories include informal logic, social epistemology, ethnomethodology, speech acts, the sociology of knowledge, the sociology of science, and social psychology. These new theories are not non-logical or anti-logical. They find logical coherence in most communities of discourse. These theories are thus often labeled "sociological" in that they focus on the social grounds of knowledge. |

論証と知識の根拠 論証理論は、哲学の分野における知識論(エピステモロジー)である基礎づけ主義に起源を持つ。それは普遍的な知識体系の形式(論理)と材料(事実法則)に おいて、主張の根拠を見出そうとした。弁証法的手法はプラトンによって有名となり、彼はソクラテスを用いて様々な人物や歴史的実在を批判的に問い詰めた。 しかし論証研究者たちは次第に、アリストテレスの体系的哲学やプラトン・カントの理想主義を拒絶するようになった。彼らは、論証の前提が形式的な哲学体系 から正当性を得るという考えを疑問視し、最終的に放棄した。こうしてこの分野は広がっていった。 この潮流の先駆者たる一人に哲学者シャイム・ペレルマンがいる。彼は1958年、ルーシー・オルブレヒト=ティテカと共に「ラ・ヌーヴェル・レトリク(新 しい修辞学)」というフランス語概念を提唱した。これは形式的推論規則の適用に還元されない議論手法を指す。ペレルマンの議論観は司法的アプローチに近 く、証拠提示と反論の規則が重要な役割を果たす。 カール・R・ウォレスの画期的な論文「レトリックの本質:正当な理由」『Quarterly Journal of Speech』(1963)44 は、多くの学者に「市場における議論」、つまり普通の人々の日常的な議論の研究を促した。市場における議論に関する先駆的な論文は、レイ・リン・アンダー ソンと C. デビッド・モーテンセンによる「論理と市場における議論」『Quarterly Journal of Speech』53 (1967): 143–150 である。[8][9] この考え方は、知識社会学における最近の展開と自然に結びついた。[10] 一部の学者は、哲学における最近の展開、すなわちジョン・デューイとリチャード・ローティの実用主義との関連性を指摘した。ローティは、この重点の移行を 「言語学的転回」と呼んだ。 この新たなハイブリッド的アプローチでは、道徳的・科学的・認識論的、あるいは科学だけでは答えられない性質の問題について、説得力のある結論を導くため に、実証的証拠の有無にかかわらず議論が用いられる。実用主義と人文社会科学における多くの知的発展から、「非哲学的」議論理論が生まれた。これらは議論 の形式的・実質的根拠を特定の知的領域に位置づけた。これらの理論には、非形式論理学、社会認識論、エスノメソドロジー、発話行為理論、知識社会学、科学 社会学、社会心理学などが含まれる。これらの新理論は非論理的でも反論理的でもない。ほとんどの言説共同体において論理的整合性を見出す。したがって、知 識の社会的基盤に焦点を当てる点で、これらの理論はしばしば「社会学的」と称される。 |

| Kinds of argumentation Conversational argumentation Main articles: Conversation analysis and Discourse analysis The study of naturally occurring conversation arose from the field of sociolinguistics. It is usually called conversation analysis (CA). Inspired by ethnomethodology, it was developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s principally by the sociologist Harvey Sacks and, among others, his close associates Emanuel Schegloff and Gail Jefferson. Sacks died early in his career, but his work was championed by others in his field, and CA has now become an established force in sociology, anthropology, linguistics, speech-communication and psychology.[11] It is particularly influential in interactional sociolinguistics, discourse analysis and discursive psychology, as well as being a coherent discipline in its own right. Recently CA techniques of sequential analysis have been employed by phoneticians to explore the fine phonetic details of speech. Empirical studies and theoretical formulations by Sally Jackson and Scott Jacobs, and several generations of their students, have described argumentation as a form of managing conversational disagreement within communication contexts and systems that naturally prefer agreement. |

議論の種類 会話における議論 主な記事: 会話分析と言説分析 自然発生的な会話の研究は社会言語学の分野から生まれた。通常、会話分析(CA)と呼ばれる。エスノメソドロジーに触発され、1960年代後半から 1970年代初頭にかけて、主に社会学者ハーヴェイ・サックスと、その近しい協力者であるエマニュエル・シェグロフやゲイル・ジェファーソンらによって発 展した。サックスはキャリアの早い段階で亡くなったが、彼の業績は同分野の他の研究者によって継承され、CAは現在では社会学、人類学、言語学、音声コ ミュニケーション学、心理学において確立された学問領域となっている。[11] 特に相互作用社会言語学、談話分析、談話心理学において影響力が大きく、それ自体が首尾一貫した学問領域でもある。近年では音声学者らが、CAの逐次分析 技法を用いて話し言葉の微細な音声的特徴を解明している。 サリー・ジャクソンとスコット・ジェイコブス、そして彼らの数世代にわたる弟子たちによる実証研究と理論構築は、議論を「合意を自然に好むコミュニケーション文脈やシステム内における対話的不一致を管理する形態」として描き出している。 |

| Mathematical argumentation Main article: Philosophy of mathematics The basis of mathematical truth has been the subject of long debate. Frege in particular sought to demonstrate (see Gottlob Frege, The Foundations of Arithmetic, 1884, and Begriffsschrift, 1879) that arithmetical truths can be derived from purely logical axioms and therefore are, in the end, logical truths.[12] The project was developed by Russell and Whitehead in their Principia Mathematica. If an argument can be cast in the form of sentences in symbolic logic, then it can be tested by the application of accepted proof procedures. This was carried out for arithmetic using Peano axioms, and the foundation most commonly used for most modern mathematics is Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory, with or without the Axiom of Choice. Be that as it may, an argument in mathematics, as in any other discipline, can be considered valid only if it can be shown that it cannot have true premises and a false conclusion. |

数学的論証 主な記事: 数学哲学 数学的真理の基盤は長きにわたる議論の主題となってきた。特にフレーゲは(ゴットロップ・フレーゲ『算術の基礎』1884年、『概念記号』1879年参 照)、算術的真理は純粋に論理的な公理から導出可能であり、したがって究極的には論理的真理であることを示そうとした。[12] この試みはラッセルとホワイトヘッドによる『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』で発展した。論証が記号論理の文の形で表せるならば、それは認められた証明手順 の適用によって検証可能となる。これはペアーノ公理を用いて算術に対して行われ、現代数学の大半で最も一般的に用いられる基礎は、選択公理の有無にかかわ らずツェルメロ=フレーンケル集合論である。いずれにせよ、数学における議論は他の分野と同様、真の前提と偽の結論を同時に持つことが不可能であると示せ るときにのみ、有効と見なされる。 |

| Scientific argumentation Main articles: Philosophy of science and Rhetoric of science Perhaps the most radical statement of the social grounds of scientific knowledge appears in Alan G.Gross's The Rhetoric of Science (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990). Gross holds that science is rhetorical "without remainder",[13] meaning that scientific knowledge itself cannot be seen as an idealized ground of knowledge. Scientific knowledge is produced rhetorically, meaning that it has special epistemic authority only insofar as its communal methods of verification are trustworthy. This thinking represents an almost complete rejection of the foundationalism on which argumentation was first based. |

科学的論証 主な記事: 科学哲学と科学の修辞学 科学的知識の社会的基盤に関する最も過激な主張は、アラン・G・グロスの『科学の修辞学』(ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局、1990年)に見られ る。グロスは、科学は「完全に」修辞的であると主張する[13]。これは、科学的知識そのものが知識の理想化された基盤とは見なせないことを意味する。科 学的知識は修辞的に生成される。つまり、その共同的な検証方法が信頼できる範囲においてのみ、特別な認識論的権威を持つのである。この考え方は、議論が最 初に依拠していた基礎づけ主義をほぼ完全に否定するものだ。 |

| Interpretive argumentation Main article: Interpretive discussion Interpretive argumentation is a dialogical process in which participants explore and/or resolve interpretations often of a text of any medium containing significant ambiguity in meaning. Interpretive argumentation is pertinent to the humanities, hermeneutics, literary theory, linguistics, semantics, pragmatics, semiotics, analytic philosophy and aesthetics. Topics in conceptual interpretation include aesthetic, judicial, logical and religious interpretation. Topics in scientific interpretation include scientific modeling. |

解釈的議論 主な記事: 解釈的議論 解釈的議論とは、参加者が意味に重大な曖昧性を含むあらゆる媒体のテキストについて、解釈を探求し、あるいは解決するダイアロジックなプロセスである。 解釈的議論は、人文科学、解釈学、文学理論、言語学、意味論、語用論、記号論、分析哲学、美学に関連する。概念的解釈の主題には、美的解釈、司法的解釈、論理的解釈、宗教的解釈が含まれる。科学的解釈の主題には、科学的モデリングが含まれる。 |

| Legal argumentation By lawyers Main articles: Oral argument and Closing argument Legal arguments are spoken presentations to a judge or appellate court by a lawyer, or parties when representing themselves of the legal reasons why they should prevail. Oral argument at the appellate level accompanies written briefs, which also advance the argument of each party in the legal dispute. A closing argument, or summation, is the concluding statement of each party's counsel reiterating the important arguments for the trier of fact, often the jury, in a court case. A closing argument occurs after the presentation of evidence. By judges Main articles: Judicial opinion, Legal opinion, and Ratio decidendi A judicial opinion or legal opinion is in certain jurisdictions a written explanation by a judge or group of judges that accompanies an order or ruling in a case, laying out the rationale (justification) and legal principles for the ruling.[14] It cites the decision reached to resolve the dispute. A judicial opinion usually includes the reasons behind the decision.[14] Where there are three or more judges, it may take the form of a majority opinion, minority opinion or a concurring opinion.[15] |

法的論証 弁護士による 主な記事:口頭弁論と最終弁論 法的論証とは、弁護士、あるいは自らを代理する当事者が、裁判官や上訴裁判所に、自らが勝訴すべき法的理由を口頭で提示するものである。上訴段階における 口頭弁論は、書面による弁論書と併せて行われる。弁論書もまた、法的紛争における各当事者の主張を展開するものである。最終弁論、あるいは総括弁論とは、 裁判において各当事者の弁護人が、事実認定者(多くの場合陪審員)に向けて重要な主張を再確認する最終陳述である。最終弁論は証拠提示の後に実施される。 裁判官による 主な項目:司法意見、法的意見、判例法理 司法意見または法的意見とは、特定の法域において、裁判官または裁判官グループが事件の命令または判決に付随して作成する書面による説明であり、判決の根 拠(正当性)と法的原則を明示するものである。[14] これは紛争解決のために下された決定を引用する。司法意見には通常、決定の背景にある理由が含まれる。[14] 3人以上の裁判官がいる場合、多数意見、少数意見、または補足意見の形式をとることもある。[15] |

| Political argumentation Main article: Political argument Political arguments are used by academics, media pundits, candidates for political office and government officials. Political arguments are also used by citizens in ordinary interactions to comment about and understand political events.[16] The rationality of the public is a major question in this line of research. Political scientist Samuel L. Popkin coined the expression "low information voters" to describe most voters who know very little about politics or the world in general. In practice, a "low information voter" may not be aware of legislation that their representative has sponsored in Congress. A low-information voter may base their ballot box decision on a media sound-bite, or a flier received in the mail. It is possible for a media sound-bite or campaign flier to present a political position for the incumbent candidate that completely contradicts the legislative action taken in the Capitol on behalf of the constituents. It may only take a small percentage of the overall voting group who base their decision on the inaccurate information to form a voter bloc large enough to swing an overall election result. When this happens, the constituency at large may have been duped or fooled. Nevertheless, the election result is legal and confirmed. Savvy Political consultants will take advantage of low-information voters and sway their votes with disinformation and fake news because it can be easier and sufficiently effective. Fact checkers have come about in recent years to help counter the effects of such campaign tactics. |

政治的議論 主な記事: 政治的議論 政治的議論は、学者、メディア評論家、公職候補者、政府高官によって用いられる。また、市民も日常的な交流の中で政治的事件について意見を述べ理解するた めに政治的議論を用いる。[16] この研究分野における主要な疑問は、大衆の合理性である。政治学者サミュエル・L・ポプキンは、政治や世界情勢についてほとんど知識を持たない大多数の有 権者を指す「低情報有権者」という表現を考案した。 実際、「低情報有権者」は、自らが選んだ代表者が議会で提出した法案すら知らない場合がある。低情報有権者は、メディアの短い発言や郵便で受け取ったチラ シに基づいて投票判断を下すことがある。メディアの発言や選挙運動のチラシが、現職候補者の政治的立場を、有権者のために議会で採られた立法措置と完全に 矛盾する形で提示する可能性もある。不正確な情報に基づいて判断する有権者が全体のわずかな割合であっても、選挙結果を左右するほどの大きな有権者ブロッ クを形成しうる。このような事態が生じると、有権者全体が欺かれたことになる。それでも選挙結果は合法として確定する。政治コンサルタントは、低情報層の 有権者を巧みに利用し、偽情報やフェイクニュースで投票行動を誘導する。それがより容易で十分な効果を発揮するからだ。近年では、こうした選挙戦術の影響 を相殺するため、ファクトチェッカーが登場している。 |

| Psychological aspects Psychology has long studied the non-logical aspects of argumentation. For example, studies have shown that simple repetition of an idea is often a more effective method of argumentation than appeals to reason. Propaganda often utilizes repetition.[17] "Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth" is a law of propaganda often attributed to the Nazi politician Joseph Goebbels. Nazi rhetoric has been studied extensively as, inter alia, a repetition campaign. Empirical studies of communicator credibility and attractiveness, sometimes labeled charisma, have also been tied closely to empirically occurring arguments. Such studies bring argumentation within the ambit of persuasion theory and practice. Some psychologists such as William J. McGuire believe that the syllogism is the basic unit of human reasoning. They have produced a large body of empirical work around McGuire's famous title "A Syllogistic Analysis of Cognitive Relationships". A central line of this way of thinking is that logic is contaminated by psychological variables such as "wishful thinking", in which subjects confound the likelihood of predictions with the desirability of the predictions. People hear what they want to hear and see what they expect to see. If planners want something to happen they see it as likely to happen. If they hope something will not happen, they see it as unlikely to happen. Thus smokers think that they personally will avoid cancer, promiscuous people practice unsafe sex, and teenagers drive recklessly. |

心理学的側面 心理学は長年、議論における非論理的側面を研究してきた。例えば、単純な反復が理性に訴えるよりも効果的な議論法となることが研究で示されている。プロパ ガンダはしばしば反復を利用する。「嘘を繰り返し続ければ真実となる」というプロパガンダの法則は、ナチス政治家ヨーゼフ・ゲッベルスに帰せられることが 多い。 ナチスのレトリックは、とりわけ反復キャンペーンとして広く研究されてきた。 発信者の信頼性や魅力(カリスマ性と呼ばれることもある)に関する実証的研究も、実際に発生する議論と密接に関連している。こうした研究は、議論を説得理論と実践の範囲内に位置づけるものである。 ウィリアム・J・マクガイアら一部の心理学者は、三段論法が人間の推論の基本単位だと考えている。彼らはマクガイアの著名な論文「認知関係の三段論法的分 析」を中心に膨大な実証研究を生み出した。この考え方の核心は、論理が「願望的思考」といった心理的変数に汚染される点にある。被験者は予測の実現可能性 と予測の望ましさを見誤るのだ。人民は聞きたいことを聞き、見たいものを見る。計画者が何かを望めば、それが起きると見なす。起きないことを望めば、起き ないと見なす。だから喫煙者は自分だけは癌にならないと思い込み、性的に奔放な者は安全でない性行為を続け、若者は無謀な運転をするのだ。 |

| Theories Argument fields Stephen Toulmin and Charles Arthur Willard have championed the idea of argument fields, the former drawing upon Ludwig Wittgenstein's notion of language games, (Sprachspiel) the latter drawing from communication and argumentation theory, sociology, political science, and social epistemology. For Toulmin, the term "field" designates discourses within which arguments and factual claims are grounded.[18] For Willard, the term "field" is interchangeable with "community", "audience", or "readership".[19] Similarly, G. Thomas Goodnight has studied "spheres" of argument and sparked a large literature created by younger scholars responding to or using his ideas.[20] The general tenor of these field theories is that the premises of arguments take their meaning from social communities.[21] |

理論 議論の領域 スティーブン・トゥルーミンとチャールズ・アーサー・ウィラードは議論の領域という概念を提唱した。前者はルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタインの言語ゲー ム(Sprachspiel)の概念に依拠し、後者はコミュニケーション理論、議論理論、社会学、政治学、社会認識論から着想を得ている。トゥルーミンに とって「領域」という用語は、議論や事実主張が基盤を置く言説を指す。[18] ウィラードにとって「分野」という用語は「共同体」「聴衆」「読者層」と置き換え可能である。[19] 同様に、G・トーマス・グッドナイトは議論の「領域」を研究し、彼の考えに応答したり利用したりする若手学者たちによって生み出された膨大な文献を生み出 した。[20] これらの分野理論の一般的な趣旨は、議論の前提が社会的共同体からその意味を得るというものである。[21] |

| Stephen E. Toulmin's contributions One of the most influential theorists of argumentation was the philosopher and educator, Stephen Toulmin, who is known for creating the Toulmin model of argument. His book The Uses of Argument is regarded as a seminal contribution to argumentation theory.[22] |

スティーブン・E・トゥルーミンの貢献 議論理論において最も影響力のある理論家の一人が、哲学者であり教育者でもあるスティーブン・トゥルーミンである。彼はトゥルーミン・モデルの創始者として知られる。彼の著書『議論の用途』は、議論理論への画期的な貢献と評価されている。[22] |

| Alternative to absolutism and relativism This section is transcluded from Stephen Toulmin. (edit | history) Throughout many of his works, Toulmin pointed out that absolutism (represented by theoretical or analytic arguments) has limited practical value. Absolutism is derived from Plato's idealized formal logic, which advocates universal truth; accordingly, absolutists believe that moral issues can be resolved by adhering to a standard set of moral principles, regardless of context. By contrast, Toulmin contends that many of these so-called standard principles are irrelevant to real situations encountered by human beings in daily life. To develop his contention, Toulmin introduced the concept of argument fields. In The Uses of Argument (1958), Toulmin claims that some aspects of arguments vary from field to field, and are hence called "field-dependent", while other aspects of argument are the same throughout all fields, and are hence called "field-invariant". The flaw of absolutism, Toulmin believes, lies in its unawareness of the field-dependent aspect of argument; absolutism assumes that all aspects of argument are field invariant. In Human Understanding (1972), Toulmin suggests that anthropologists have been tempted to side with relativists because they have noticed the influence of cultural variations on rational arguments. In other words, the anthropologist or relativist overemphasizes the importance of the "field-dependent" aspect of arguments, and neglects or is unaware of the "field-invariant" elements. In order to provide solutions to the problems of absolutism and relativism, Toulmin attempts throughout his work to develop standards that are neither absolutist nor relativist for assessing the worth of ideas. In Cosmopolis (1990), he traces philosophers' "quest for certainty" back to René Descartes and Thomas Hobbes, and lauds John Dewey, Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, and Richard Rorty for abandoning that tradition. |

絶対主義と相対主義の代替案 この節はスティーブン・トゥルーミンの項目から転載されたものである。(編集 | 履歴) トゥルーミンは多くの著作において、絶対主義(理論的または分析的議論によって代表される)には実用的な価値が限られていると指摘した。絶対主義は普遍的 真理を主張するプラトンの理想化された形式論理に由来する。したがって絶対主義者は、文脈に関わらず標準的な道徳原則に従うことで道徳的問題が解決できる と信じる。これに対しトゥルーミンは、こうしたいわゆる標準原則の多くが、人間が日常生活で直面する現実の状況とは無関係だと主張する。 この主張を展開するため、トゥルーミンは議論の領域という概念を導入した。『議論の用途』(1958年)において、彼は議論のいくつかの側面は領域によっ て異なり「領域依存的」と呼ばれる一方、他の側面はあらゆる領域で共通であり「領域不変的」と呼ばれると主張している。トゥルーミンによれば、絶対主義の 欠陥は、議論の分野依存的側面を認識していない点にある。絶対主義は議論のあらゆる側面が分野不変であると仮定するのだ。 『人間の理解』(1972年)においてトゥルーミンは、人類学者が相対主義者に同調しがちなのは、文化的差異が合理的議論に影響を与えることに気づいたた めだと示唆している。つまり、人類学者や相対主義者は、議論の「分野依存的」側面の重要性を過度に強調し、「分野不変的」要素を軽視、あるいは認識してい ない。絶対主義と相対主義の問題に対する解決策を提供するため、トゥルーミンは、その著作全体を通して、アイデアの価値を評価するための、絶対主義でも相 対主義でもない基準の開発を試みている。 『コスモポリス』(1990年)では、哲学者の「確実性の探求」をルネ・デカルトとトマス・ホッブズにまで遡って考察し、その伝統を放棄したジョン・デューイ、ウィトゲンシュタイン、マーティン・ハイデガー、リチャード・ローティを称賛している。 |

| Toulmin model of argument This section is transcluded from Stephen Toulmin. (edit | history)  Toulmin argumentation can be diagrammed as a conclusion established, more or less, on the basis of a fact supported by a warrant (with backing), and a possible rebuttal. Further information: Practical arguments Arguing that absolutism lacks practical value, Toulmin aimed to develop a different type of argument, called practical arguments (also known as substantial arguments). In contrast to absolutists' theoretical arguments, Toulmin's practical argument is intended to focus on the justificatory function of argumentation, as opposed to the inferential function of theoretical arguments. Whereas theoretical arguments make inferences based on a set of principles to arrive at a claim, practical arguments first find a claim of interest, and then provide justification for it. Toulmin believed that reasoning is less an activity of inference, involving the discovering of new ideas, and more a process of testing and sifting already existing ideas—an act achievable through the process of justification. Toulmin believed that for a good argument to succeed, it needs to provide good justification for a claim. This, he believed, will ensure it stands up to criticism and earns a favourable verdict. In The Uses of Argument (1958), Toulmin proposed a layout containing six interrelated components for analyzing arguments: Claim (Conclusion) A conclusion whose merit must be established. In argumentative essays, it may be called the thesis.[23] For example, if a person tries to convince a listener that he is a British citizen, the claim would be "I am a British citizen" (1). Ground (Fact, Evidence, Data) A fact one appeals to as a foundation for the claim. For example, the person introduced in 1 can support his claim with the supporting data "I was born in Bermuda" (2). Warrant A statement authorizing movement from the ground to the claim. In order to move from the ground established in 2, "I was born in Bermuda", to the claim in 1, "I am a British citizen", the person must supply a warrant to bridge the gap between 1 and 2 with the statement "A man born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen" (3). Backing Credentials designed to certify the statement expressed in the warrant; backing must be introduced when the warrant itself is not convincing enough to the readers or the listeners. For example, if the listener does not deem the warrant in 3 as credible, the speaker will supply the legal provisions: "I trained as a barrister in London, specialising in citizenship, so I know that a man born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen". Rebuttal (Reservation) Statements recognizing the restrictions which may legitimately be applied to the claim. It is exemplified as follows: "A man born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen, unless he has betrayed Britain and has become a spy for another country". Qualifier Words or phrases expressing the speaker's degree of force or certainty concerning the claim. Such words or phrases include "probably", "possible", "impossible", "certainly", "presumably", "as far as the evidence goes", and "necessarily". The claim "I am definitely a British citizen" has a greater degree of force than the claim "I am a British citizen, presumably". (See also: Defeasible reasoning.) The first three elements, claim, ground, and warrant, are considered as the essential components of practical arguments, while the second triad, qualifier, backing, and rebuttal, may not be needed in some arguments. |

トゥルーミンの議論モデル この節はスティーブン・トゥルーミンから転載されている。(編集 | 履歴)  トゥルーミンの議論は、保証(裏付け)によって支持された事実と、反論の可能性に基づいて、多かれ少なかれ確立された結論として図式化できる。 詳細情報: 実践的論証 絶対主義には実践的価値がないと主張するトゥルーミンは、実践的論証(実質的論証とも呼ばれる)と呼ばれる異なるタイプの論証を開発しようとした。絶対主 義者の理論的論証とは対照的に、トゥルーミンの実践的論証は、理論的論証の推論機能とは対照的に、論証の正当化機能に焦点を当てることを意図している。理 論的論証が一連の原理に基づいて推論を行い主張に到達するのに対し、実践的論証はまず関心のある主張を見つけ、その後それを正当化する。トゥルーミンは、 推論とは新しい考えを発見する推論活動というより、既存の考えを検証し選別するプロセスであり、正当化の過程を通じて達成可能な行為だと考えた。 トゥルーミンは、優れた議論が成立するためには、主張に対する適切な正当化を提供する必要があると考えた。これにより批判に耐え、好意的な評価を得られる と彼は信じていた。『議論の用途』(1958年)において、トゥルーミンは議論を分析するための相互に関連する六つの構成要素からなる枠組みを提案した: 主張(結論) その妥当性を立証すべき結論。論説文では「テーゼ」と呼ばれることもある。[23] 例えば、ある人格が聞き手に自分が英国市民だと説得しようとする場合、主張は「私は英国市民である」(1)となる。 根拠(事実、証拠、データ) 主張の基盤として訴える事実。例えば、1で紹介した人格は「私はバミューダで生まれた」(2)という裏付けデータで主張を支持できる。 保証 根拠から主張への移行を正当化する文言。2で確立した根拠「私はバミューダで生まれた」から、主張1「私は英国市民である」へ移行するには、1と2の間の隔たりを埋める保証文「バミューダ生まれの男性は法的に英国市民となる」(3)を提示しなければならない。 裏付け 保証文で表明された主張を証明するための証拠。保証文自体が読者や聴衆を十分に納得させられない場合に提示される。例えば、聴衆が3の保証文を信用しない 場合、話者は法的根拠を提示する:「私はロンドンで弁護士として訓練を受け、市民権を専門とした。だからバミューダ生まれの男性が法的に英国市民となるこ とを知っている」。 反論(留保) 主張に対して正当に適用され得る制限を認める声明。例:「バミューダで生まれた男性は、英国を裏切り他国のスパイとなった場合を除き、法的に英国市民となる」 限定語 主張に対する発言者の確信度や確実性を示す語句。例:「おそらく」「可能性」「不可能」「確実に」「おそらく」「証拠の範囲内では」「必然的に」など。 「私は間違いなく英国市民である」という主張は、「おそらく私は英国市民である」という主張よりも強い力を持つ。(参照:反駁可能な推論) 主張、根拠、保証という最初の三要素は、実践的な議論の必須要素と見なされる。一方、修飾語、裏付け、反駁という次の三要素は、一部の議論では必要とされない場合がある。 |

| When Toulmin first proposed it,

this layout of argumentation was based on legal arguments and intended

to be used to analyze the rationality of arguments typically found in

the courtroom. Toulmin did not realize that this layout could be

applicable to the field of rhetoric and communication until his works

were introduced to rhetoricians by Wayne Brockriede and Douglas

Ehninger. Their Decision by Debate (1963) streamlined Toulmin's

terminology and broadly introduced his model to the field of

debate.[24] Only after Toulmin published Introduction to Reasoning

(1979) were the rhetorical applications of this layout mentioned in his

works. One criticism of the Toulmin model is that it does not fully consider the use of questions in argumentation.[25] The Toulmin model assumes that an argument starts with a fact or claim and ends with a conclusion, but ignores an argument's underlying questions. In the example "Harry was born in Bermuda, so Harry must be a British subject", the question "Is Harry a British subject?" is ignored, which also neglects to analyze why particular questions are asked and others are not. (See Issue mapping for an example of an argument-mapping method that emphasizes questions.) Toulmin's argument model has inspired research on, for example, goal structuring notation (GSN), widely used for developing safety cases,[26] and argument maps and associated software.[27] |

トゥルーミンが最初にこの論証の枠組みを提案した時、それは法廷におけ

る議論に基づいており、法廷で典型的に見られる議論の合理性を分析するために用いられることを意図していた。トゥルーミン自身が、この枠組みが修辞学やコ

ミュニケーションの分野に応用可能であることに気づいたのは、ウェイン・ブロックリードとダグラス・エニングアーによって彼の著作が修辞学者たちに紹介さ

れてからのことだった。彼らの『ディベートによる決定』(1963年)は、トゥルーミンの用語体系を整理し、そのモデルをディベート分野に広く紹介した

[24]。トゥルーミン自身が『推論入門』(1979年)を出版して初めて、この枠組みの修辞学的応用が彼の著作で言及されるようになった。 トゥルーミン・モデルの批判の一つは、議論における質問の活用を十分に考慮していない点だ。[25] トゥルーミンモデルは、議論が事実や主張から始まり結論で終わることを前提とするが、議論の根底にある疑問を無視している。「ハリーはバミューダで生まれ たから、ハリーは英国国民であるに違いない」という例では、「ハリーは英国国民か?」という疑問が無視され、特定の疑問が問われ他の疑問が問われない理由 の分析も欠けている。(質問を重視する議論マッピング手法の例については、イシューマッピングを参照のこと。) トゥルーミンの議論モデルは、例えば安全ケース構築に広く用いられる目標構造化表記法(GSN)[26]や、議論マップ及び関連ソフトウェア[27]などの研究に影響を与えている。 |

| Evolution of knowledge This section is transcluded from Stephen Toulmin. (edit | history) In 1972, Toulmin published Human Understanding, in which he asserts that conceptual change is an evolutionary process. In this book, Toulmin attacks Thomas Kuhn's account of conceptual change in his seminal work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962). Kuhn believed that conceptual change is a revolutionary process (as opposed to an evolutionary process), during which mutually exclusive paradigms compete to replace one another. Toulmin criticized the relativist elements in Kuhn's thesis, arguing that mutually exclusive paradigms provide no ground for comparison, and that Kuhn made the relativists' error of overemphasizing the "field variant" while ignoring the "field invariant" or commonality shared by all argumentation or scientific paradigms. In contrast to Kuhn's revolutionary model, Toulmin proposed an evolutionary model of conceptual change comparable to Darwin's model of biological evolution. Toulmin states that conceptual change involves the process of innovation and selection. Innovation accounts for the appearance of conceptual variations, while selection accounts for the survival and perpetuation of the soundest conceptions. Innovation occurs when the professionals of a particular discipline come to view things differently from their predecessors; selection subjects the innovative concepts to a process of debate and inquiry in what Toulmin considers as a "forum of competitions". The soundest concepts will survive the forum of competition as replacements or revisions of the traditional conceptions. From the absolutists' point of view, concepts are either valid or invalid regardless of contexts. From the relativists' perspective, one concept is neither better nor worse than a rival concept from a different cultural context. From Toulmin's perspective, the evaluation depends on a process of comparison, which determines whether or not one concept will improve explanatory power more than its rival concepts. |

知識の進化 この節はスティーブン・トゥルーミンから転載されている。(編集 | 履歴) 1972年、トゥルーミンは『人間の理解』を出版し、概念の変化は進化的プロセスであると主張した。この本でトゥルーミンは、トーマス・クーンの画期的な 著作『科学革命の構造』(1962年)における概念変化の説明を批判している。クーンは概念変化が革命的プロセス(進化的プロセスとは対照的に)であり、 互いに排他的なパラダイムが互いを置き換えるために競合すると考えていた。トゥルーミンはクーンの理論における相対主義的要素を批判し、互いに排他的なパ ラダイムは比較の基盤を提供せず、クーンが「分野変異体」を過度に強調する一方で、全ての議論や科学的パラダイムに共通する「分野不変体」を無視するとい う相対主義者の誤りを犯したと論じた。 クーンの革命的モデルとは対照的に、トゥルーミンはダーウィンの生物学的進化モデルに匹敵する概念変化の進化的モデルを提案した。トゥルーミンによれば、 概念変化には革新と選択のプロセスが伴う。革新は概念的変異の出現を説明し、選択は最も妥当な概念の存続と永続を説明する。革新は特定分野の専門家が先人 とは異なる見解を持つことで生じ、選択は革新的な概念をトゥルーミンが「競争の場」と称する議論と探究のプロセスに晒す。最も妥当な概念は、伝統的概念の 代替または修正として、競争の場の試練を生き残るのである。 絶対主義者の立場では、概念は文脈に関わらず有効か無効かのいずれかである。相対主義者の視点では、異なる文化的文脈に由来する競合概念と比べて、ある概 念が優れているとも劣っているとも言い切れない。トゥルーミンの視点では、評価は比較のプロセスに依存し、ある概念が競合概念よりも説明力を向上させるか どうかを決定するのである。 |

| Pragma-dialectics Main article: Pragma-dialectics Scholars at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands have pioneered a rigorous modern version of dialectic under the name pragma-dialectics. The intuitive idea is to formulate clear-cut rules that, if followed, will yield reasonable discussion and sound conclusions. Frans H. van Eemeren, the late Rob Grootendorst, and many of their students and co-authors have produced a large body of work expounding this idea. The dialectical conception of reasonableness is given by ten rules for critical discussion, all being instrumental for achieving a resolution of the difference of opinion (from Van Eemeren, Grootendorst, & Snoeck Henkemans, 2002, p. 182–183). The theory postulates this as an ideal model, and not something one expects to find as an empirical fact. The model can however serve as an important heuristic and critical tool for testing how reality approximates this ideal and point to where discourse goes wrong, that is, when the rules are violated. Any such violation will constitute a fallacy. Albeit not primarily focused on fallacies, pragma-dialectics provides a systematic approach to deal with them in a coherent way. Van Eemeren and Grootendorst identified four stages of argumentative dialogue. These stages can be regarded as an argument protocol. In a somewhat loose interpretation, the stages are as follows:[citation needed] Confrontation stage: Presentation of the difference of opinion, such as a debate question or a political disagreement. Opening stage: Agreement on material and procedural starting points, the mutually acceptable common ground of facts and beliefs, and the rules to be followed during the discussion (such as, how evidence is to be presented, and determination of closing conditions). Argumentation stage: Presentation of reasons for and against the standpoint(s) at issue, through application of logical and common-sense principles according to the agreed-upon rules Concluding stage: Determining whether the standpoint has withstood reasonable criticism, and accepting it is justified. This occurs when the termination conditions are met (Among these could be, for example, a time limitation or the determination of an arbiter.) Van Eemeren and Grootendorst provide a detailed list of rules that must be applied at each stage of the protocol.[citation needed] Moreover, in the account of argumentation given by these authors, there are specified roles of protagonist and antagonist in the protocol which are determined by the conditions which set up the need for argument. |

プラグマ・ダイアレクティクス 主な記事: プラグマ・ダイアレクティクス オランダのアムステルダム大学の学者たちは、プラグマ・ダイアレクティクスという名称のもと、厳密な現代版弁証法を先駆的に確立した。その直観的な考え方 は、明確な規則を定めて、それに従えば合理的な議論と妥当な結論が得られるというものだ。フランス・H・ファン・エメレン、故ロブ・グルートエンドルス ト、そして彼らの多くの学生や共著者が、この考えを解説する膨大な著作を生み出している。 合理性に関する弁証法的概念は、批判的議論のための十の規則によって示される。これらは全て、意見の相違を解決するために有用である(Van Eemeren, Grootendorst, & Snoeck Henkemans, 2002, p. 182–183)。この理論はこれを理想モデルとして提唱しており、実証的事実として発見されることを期待するものではない。しかしこのモデルは、現実が この理想にどの程度近づいているかを検証し、言説がどこで誤るかを、すなわち規則が破られる点を指摘する重要な発見的手法及び批判的ツールとして機能し得 る。いかなる規則違反も誤謬を構成する。誤謬を主眼とはしないものの、プラグマ・ダイアレクティクスはそれらを一貫した方法で扱う体系的なアプローチを提 供する。 ファン・エメレンとグルートエンドルストは、議論的対話の四段階を特定した。これらの段階は議論のプロトコルと見なせる。やや大まかな解釈では、段階は以下の通りである:[出典が必要] 対立段階:意見の相違の提示。例えば討論の議題や政治的対立など。 開始段階:議論の出発点となる事実・信念の共通基盤、および議論中に従うべきルール(証拠の提示方法や終了条件の決定など)について合意する段階。 論証段階:合意された規則に従い、論理的・常識的原則を適用して、争点となる立場に対する賛否両論の理由を提示する。 結論段階:立場が合理的な批判に耐えたかどうかを判断し、正当であると認める。これは終了条件が満たされた時に発生する(例:時間制限や仲裁人の決定など)。 ヴァン・エメレンとグルートエンドルストは、このプロトコルの各段階で適用すべき規則の詳細なリストを提供している[出典が必要]。さらに、これらの著者 が提示する議論の枠組みにおいては、議論の必要性を生じさせる条件によって決定される、プロトコル内の主張者と反論者の役割が明確に規定されている。 |

| Walton's logical argumentation method Douglas N. Walton developed a distinctive philosophical theory of logical argumentation built around a set of practical methods to help a user identify, analyze and evaluate arguments in everyday conversational discourse and in more structured areas such as debate, law and scientific fields.[28] There are four main components: argumentation schemes,[29] dialogue structures, argument mapping tools, and formal argumentation systems. The method uses the notion of commitment in dialogue as the fundamental tool for the analysis and evaluation of argumentation rather than the notion of belief.[6] Commitments are statements that the agent has expressed or formulated, and has pledged to carry out, or has publicly asserted. According to the commitment model, agents interact with each other in a dialogue in which each takes its turn to contribute speech acts. The dialogue framework uses critical questioning as a way of testing plausible explanations and finding weak points in an argument that raise doubt concerning the acceptability of the argument. Walton's logical argumentation model took a view of proof and justification different from analytic philosophy's dominant epistemology, which was based on a justified true belief framework.[30] In the logical argumentation approach, knowledge is seen as form of belief commitment firmly fixed by an argumentation procedure that tests the evidence on both sides, and uses standards of proof to determine whether a proposition qualifies as knowledge. In this evidence-based approach, knowledge must be seen as defeasible. |

ウォルトンの論理的議論手法 ダグラス・N・ウォルトンは、日常言説や討論・法律・科学分野といった構造化された領域における議論を識別・分析・評価するための実践的手法を核とした、 独自の論理的議論の哲学理論を構築した[28]。主な構成要素は四つある:議論スキーム[29]、対話構造、議論マッピングツール、形式的議論体系であ る。この手法は、議論の分析と評価の根本的な道具として、信念の概念ではなく対話におけるコミットメントの概念を用いる。[6] コミットメントとは、主体が表明または形成し、実行を約束した、あるいは公に主張した発言である。コミットメントモデルによれば、主体は対話において交互 に発話行為を貢献しながら相互作用する。対話枠組みは、妥当な説明を検証し、議論の受け入れ可能性に疑念を生じさせる弱点を見つける手段として、批判的質 問を用いる。 ウォルトンの論理的議論モデルは、正当化された真の信念枠組みに基づく分析哲学の主流認識論とは異なる証明と正当化の観点を採った。[30] 論理的議論アプローチでは、知識は両側の証拠を検証する議論手続きによって確固として固定された信念のコミットメントの一形態と見なされる。証明基準を用 いて命題が知識として適格かどうかを判断する。この証拠に基づくアプローチでは、知識は反駁可能と見なされなければならない。 |

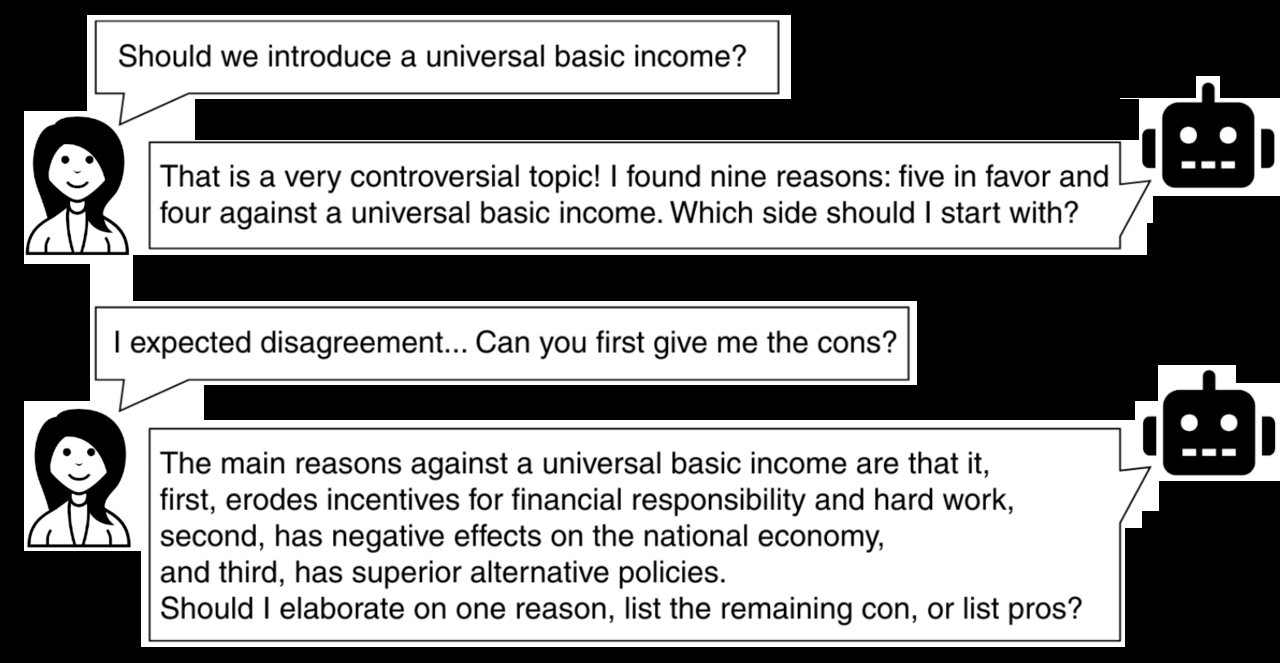

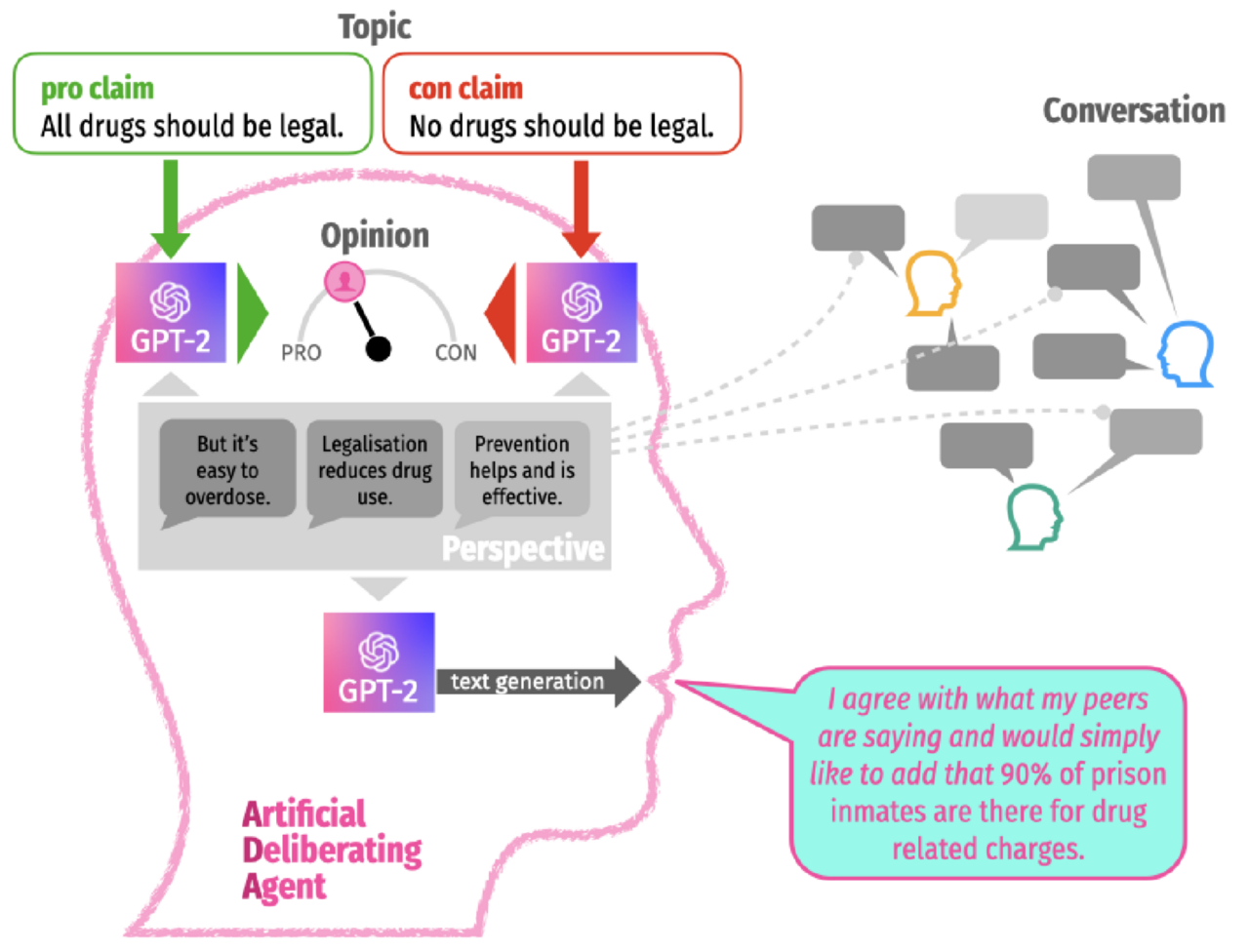

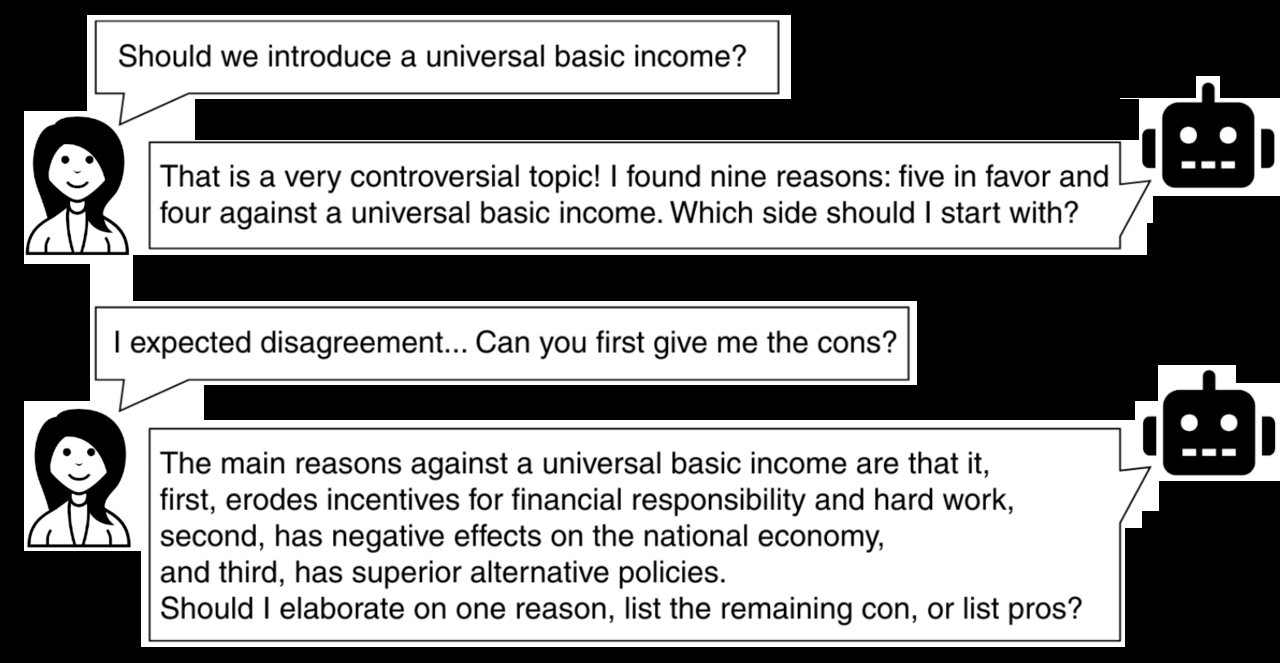

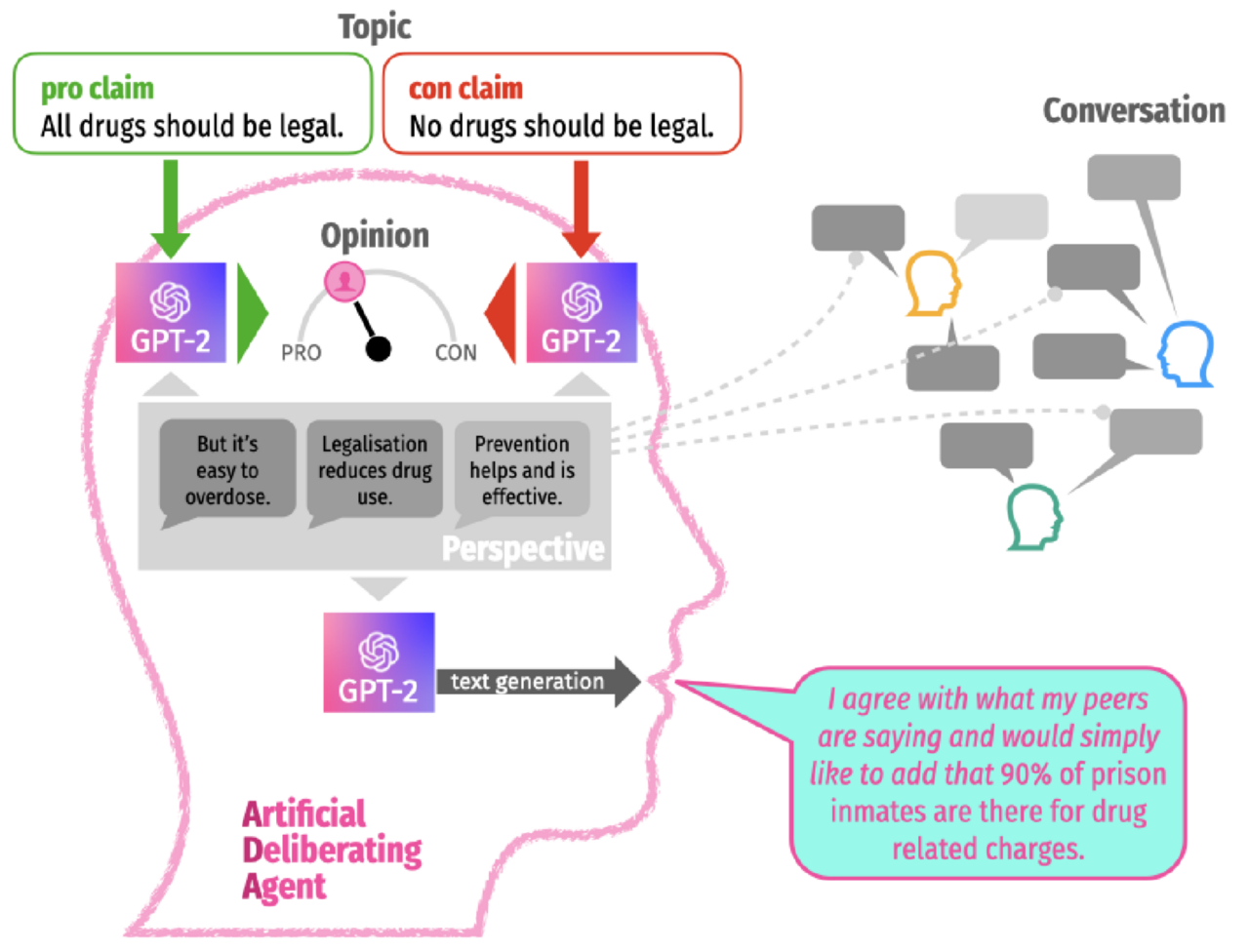

| Artificial intelligence See also: Argument technology, Argument mapping, and Argumentation framework  Structured debates from platforms like Kialo could be used for "artificial deliberative agents" (ADAs) or computational reasoning.[31][32]  Example of an ADA contributing missing information to a debate via crawled Kialo data and selected based on the prior conversation and crawled argument weight ratings[32] Efforts have been made within the field of artificial intelligence to perform and analyze argumentation with computers. Argumentation has been used to provide a proof-theoretic semantics for non-monotonic logic, starting with the influential work of Dung (1995). Computational argumentation systems have found particular application in domains where formal logic and classical decision theory are unable to capture the richness of reasoning, domains such as law and medicine. In Elements of Argumentation, Philippe Besnard and Anthony Hunter show how classical logic-based techniques can be used to capture key elements of practical argumentation.[33] Within computer science, the ArgMAS workshop series (Argumentation in Multi-Agent Systems), the CMNA workshop series,[34] and the COMMA Conference,[35] are regular annual events attracting participants from every continent. The journal Argument & Computation[36] is dedicated to exploring the intersection between argumentation and computer science. ArgMining is a workshop series dedicated specifically to the related argument mining task.[37] Data from the collaborative structured online argumentation platform Kialo has been used to train and to evaluate natural language processing AI systems such as, most commonly, BERT and its variants.[48] This includes argument extraction, conclusion generation,[40][additional citation(s) needed] argument form quality assessment,[49] machine argumentative debate generation or participation,[44][46][47] surfacing most relevant previously overlooked viewpoints or arguments,[44][46] argumentative writing support[42] (including sentence attackability scores),[50] automatic real-time evaluation of how truthful or convincing a sentence is (similar to fact-checking),[50] language model fine tuning[51][47] (including for chatbots),[52][53] argument impact prediction, argument classification and polarity prediction.[54][55] |

人工知能 関連項目:議論技術、議論マッピング、議論フレームワーク  Kialoのようなプラットフォームによる構造化された議論は、「人工審議エージェント」(ADA)や計算推論に活用できる[31][32]。  ADAの例:クロールしたKialoデータから議論に不足情報を補完し、事前会話とクロールした議論の重み付け評価に基づいて選択する[32] 人工知能の分野では、コンピュータによる議論の実行と分析が行われてきた。議論は、Dung(1995)の影響力ある研究を起点として、非単調論理の証明 理論的意味論を提供する手段として用いられてきた。計算論的議論システムは、形式論理や古典的決定理論では捉えきれない豊かな推論が求められる分野、例え ば法学や医学において特に応用されている。『Elements of Argumentation』において、Philippe BesnardとAnthony Hunterは、古典論理に基づく手法を用いて実践的議論の重要な要素をいかに捉えられるかを示している。[33] コンピュータサイエンス分野では、ArgMASワークショップシリーズ(マルチエージェントシステムにおける論証)、CMNAワークショップシリーズ [34]、COMMAカンファレンス[35]が毎年開催され、世界中の参加者を集めている。学術誌『Argument & Computation』[36]は、論証とコンピュータサイエンスの交差点を探求することに特化している。ArgMiningは、関連する論証マイニン グタスクに特化したワークショップシリーズである。[37] 共同構造化オンライン論証プラットフォームKialoのデータは、自然言語処理AIシステムの訓練と評価に利用されている。最も一般的な例はBERTとそ の派生モデルである[48]。これには論証抽出、結論生成[40][追加引用が必要]、論証形式の質評価[49]、機械による論証的討論の生成または参加 [44]、 [46][47] これまで見落とされていた最も関連性の高い視点や議論の抽出[44][46]、議論的ライティング支援[42](文の攻撃可能性スコアを含む)[50]、 文の真実性や説得力の自動リアルタイム評価(ファクトチェックに類似)[50]、言語モデルの微調整[51][47](チャットボット向けを含む)、 [52][53] 議論の影響力予測、議論の分類と極性予測。[54][55] |

| Argument – Attempt to persuade or to determine the truth of a conclusion Argumentum a fortiori – Argument from a yet stronger reason Aristotelian rhetoric – Standard collection of Aristotle's six works on logic Modes of persuasion – Strategies of rhetoric Rhetoric (Aristotle) – Work of literature by Aristotle Topics (Aristotle) – Works by Aristotle Criticism – Practice of judging the merits and faults of something Critical thinking – Analysis of facts to form a judgment Defeasible reasoning – Reasoning that is rationally compelling, though not deductively valid Dialectic – Method of reasoning via argumentation and contradiction Discourse ethics – Argument focused on ethics Essentially contested concept – Problem in philosophy Forensics – Application of science to criminal and civil laws Legal theory – Theoretical study of law Logic and dialectic – Formalisation of dialectic Logic of argumentation – Formalised description of reasoning Logical reasoning – Process of drawing correct inferences Negotiation theory – Study of negotiations Pars destruens and pars construens – Complementary parts of argumentation Policy debate – Form of competitive debate Stock issues – Five subtopical issues in policy debate Presumption – In law, an inference of a particular fact Public sphere – Area in social life with political ramifications Rationality – Quality of being agreeable to reason Rhetoric – Art of persuasion Rogerian argument – Conflict-solving technique Social engineering (political science) – Discipline in social science Social psychology – Study of social effects on people's thoughts, feelings, and behaviors Sophistry – Reasoning with clever but fallacious and deceptive arguments Source criticism – Process of evaluating an information source Straight and Crooked Thinking – Book by Robert H. Thouless |

論証 – 結論の真実性を説得または決定しようとする試み 強弁法 – より強力な理由に基づく論証 アリストテレス修辞学 – アリストテレスの論理学に関する六著作の標準的集成 説得の様式 – 修辞学の戦略 修辞学(アリストテレス) – アリストテレスの著作 トピクス(アリストテレス) – アリストテレスの著作 批判 – 何かの長所と短所を判断する行為 批判的思考 – 判断を形成するための事実分析 反駁可能な推論 – 演繹的に有効ではないが、合理的に説得力のある推論 弁証法 – 議論と矛盾による推論方法 言説倫理学 – 倫理に焦点を当てた議論 本質的に争われる概念 – 哲学における問題 法科学 – 刑事法・民事法への科学の応用 法理論 – 法の理論的研究 論理学と弁証法 – 弁証法の形式化 論証の論理 – 推論の形式化された記述 論理的推論 – 正しい推論を引き出す過程 交渉理論 – 交渉の研究 破壊的論証と構築的論証 – 論証の補完的な部分 政策討論 – 競技形式の討論 ストック問題 – 政策討論における五つのサブトピック 推定 – 法における特定の事実の推論 公共圏 – 政治的影響を伴う社会生活領域 合理性 – 理性に合致する性質 修辞学 – 説得の技法 ロジャー式議論 – 対立解決技法 社会工学(政治学) – 社会科学の分野 社会心理学 – 人民の思考、感情、行動に対する社会的影響の研究 詭弁 – 巧妙だが誤謬的で欺瞞的な論証を用いた推論 情報源批判 – 情報源を評価する過程 直線的思考と曲線的思考 – ロバート・H・トゥーレス著 |

| Further reading J. Robert Cox and Charles Arthur Willard, eds. (1982). Advances in Argumentation Theory and Research. Dung, Phan Minh (1995). "On the acceptability of arguments and its fundamental role in nonmonotonic reasoning, logic programming and n-person games". Artificial Intelligence. 77 (2): 321–357. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(94)00041-X. Bondarenko, A., Dung, P. M., Kowalski, R., and Toni, F. (1997). "An abstract, argumentation-theoretic approach to default reasoning", Artificial Intelligence 93(1–2), 63–101. Dung, P. M., Kowalski, R., and Toni, F. (2006). "Dialectic proof procedures for assumption-based, admissible argumentation." Artificial Intelligence. 170(2), 114–159. Frans van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, Sally Jackson, and Scott Jacobs (1993). Reconstructing Argumentative Discourse Frans van Eemeren & Rob Grootendorst (2004). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation: The Pragma-Dialectical Approach. Frans van Eemeren, Bart Garssen, Erik C. W. Krabbe, A. Francisca Snoeck Henkemans, Bart Verheij, & Jean H. M. Wagemans (2014). Handbook of Argumentation Theory (Revised edition). New York: Springer. Richard H. Gaskins (1993). Burdens of Proof in Modern Discourse. Yale University Press. Michael A. Gilbert (1997). Coalescent Argumentation. Trudy Govier (1987). Problems in Argument Analysis and Evaluation. Dordrecht, Holland; Providence, RI: Foris Publications. Trudy Govier (2014). A Practical Study of Argument, 7th ed. Australia; Boston, MA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning. (First edition published 1985.) Dale Hample. (1979). "Predicting belief and belief change using a cognitive theory of argument and evidence." Communication Monographs. 46, 142–146. Dale Hample. (1978). "Are attitudes arguable?" Journal of Value Inquiry. 12, 311–312. Dale Hample. (1978). "Predicting immediate belief change and adherence to argument claims." Communication Monographs, 45, 219–228. Dale Hample & Judy Hample. (1978). "Evidence credibility." Debate Issues. 12, 4–5. Dale Hample. (1977). "Testing a model of value argument and evidence." Communication Monographs. 14, 106–120. Dale Hample. (1977). "The Toulmin model and the syllogism." Journal of the American Forensic Association. 14, 1–9. Sally Jackson and Scott Jacobs, "Structure of Conversational Argument: Pragmatic Bases for the Enthymeme." The Quarterly Journal of Speech. LXVI, 251–265. Ralph H. Johnson. Manifest Rationality: A Pragmatic Theory of Argument. Lawrence Erlbaum, 2000. Ralph H. Johnson. (1996). The Rise of Informal Logic. Newport News, VA: Vale Press Ralph H. Johnson. (1999). The Relation Between Formal and Informal Logic. Argumentation, 13(3) 265–74. Ralph H. Johnson. & Blair, J. Anthony. (2006). Logical Self-Defense.First published, McGraw Hill Ryerson, Toronto, ON, 1997, 1983, 1993. Reprinted, New York: Idebate Press. Ralph H. Johnson. & Blair, J. Anthony. (1987). The current state of informal logic. Informal Logic 9, 147–51. Ralph H. Johnson. & Blair, J. Anthony. (1996). Informal logic and critical thinking. In F. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, & F. Snoeck Henkemans (Eds.), Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory. (pp. 383–86). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Ralph H. Johnson, Ralph. H. & Blair, J. Anthony. (2000). "Informal logic: An overview." Informal Logic. 20(2): 93–99. Ralph H. Johnson, Ralph. H. & Blair, J. Anthony. (2002). Informal logic and the reconfiguration of logic. In D. Gabbay, R. H. Johnson, H.-J. Ohlbach and J. Woods (Eds.). Handbook of the Logic of Argument and Inference: The Turn Towards the Practical. (pp. 339–396). Elsevier: North Holland. Chaïm Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca (1970). The New Rhetoric, Notre Dame. Stephen Toulmin (1958). The Uses of Argument. Stephen Toulmin (1964). The Place of Reason in Ethics. Douglas N. Walton (1990). Practical Reasoning: Goal-Driven, Knowledge-Based, Action-Guiding Argumentation. Savage, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Douglas N. Walton (1992). The Place of Emotion in Argument. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. Douglas N. Walton (1996). Argument Structure: A Pragmatic Theory. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Douglas N. Walton (2006). Fundamentals of Critical Argumentation. New York: Cambridge University Press. Douglas N. Walton (2013). Methods of Argumentation. New York: Cambridge University Press. Douglas N. Walton (2016). Argument Evaluation and Evidence. Cham: Springer Joseph W. Wenzel (1990). Three perspectives on argumentation. In R Trapp and J Scheutz, (Eds.), Perspectives on argumentation: Essays in honour of Wayne Brockreide (9–26). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press. John Woods. (1980). What Is informal logic? In J.A. Blair & R. H. Johnson (Eds.), Informal Logic: The First International Symposium .(pp. 57–68). Point Reyes, CA: Edgepress. John Woods. (2000). How Philosophical Is Informal Logic? Informal Logic. 20(2): 139–167. 2000 Charles Arthur Willard (1982). Argumentation and the Social Grounds of Knowledge. University of Alabama Press. Charles Arthur Willard (1989). A Theory of Argumentation. University of Alabama Press. Charles Arthur Willard (1996). Liberalism and the Problem of Knowledge: A New Rhetoric for Modern Democracy. University of Chicago Press. Harald Wohlrapp (2008). Der Begriff des Arguments. Über die Beziehungen zwischen Wissen, Forschen, Glaube, Subjektivität und Vernunft. Würzburg: Königshausen u. Neumann. ISBN 978-3-8260-3820-4 Flagship journals Argumentation Argumentation in Context Informal Logic Argumentation and Advocacy (formerly Journal of the American Forensic Association) Social Epistemology Episteme: A Journal of Social Epistemology Journal of Argument and Computation |

参考文献 J. Robert Cox と Charles Arthur Willard 編(1982)。『論証理論と研究の進展』。 Dung, Phan Minh (1995). 「議論の受容可能性と、非単調推論・論理プログラミング・n人ゲームにおけるその基本的役割について」. Artificial Intelligence. 77 (2): 321–357. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(94)00041-X. Bondarenko, A., Dung, P. M., Kowalski, R., and Toni, F. (1997). 「デフォルト推論への抽象的・議論理論的アプローチ」『人工知能』93(1–2), 63–101. Dung, P. M., Kowalski, R., and Toni, F. (2006). 「仮定に基づく許容可能な議論のための弁証法的証明手順」, Artificial Intelligence. 170(2), 114–159. Frans van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, Sally Jackson, and Scott Jacobs (1993). 論証的言説の再構築 Frans van Eemeren & Rob Grootendorst (2004). 論証の体系的理論:プラグマ・弁証法的アプローチ. Frans van Eemeren, Bart Garssen, Erik C. W. Krabbe, A. Francisca Snoeck Henkemans, Bart Verheij, & Jean H. M. Wagemans (2014). 『議論理論ハンドブック(改訂版)』ニューヨーク:シュプリンガー社。 リチャード・H・ガスキンス(1993)。『現代言説における立証責任』イェール大学出版局。 マイケル・A・ギルバート(1997)。『融合的議論』 トゥルーディ・ゴヴィア(1987)。『議論分析と評価の問題』ドルドレヒト(オランダ)/プロビデンス(ロードアイランド州):フォリス出版。 トゥルーディ・ゴヴィア(2014)。『議論の実践的研究』第7版。オーストラリア;ボストン、マサチューセッツ州:ワズワース/Cengageラーニング。(初版は1985年に出版された。) デール・ハンプル(1979)。「議論と証拠の認知理論を用いた信念と信念変化の予測」。『コミュニケーション・モノグラフ』46、142–146頁。 デール・ハンプル(1978)。「態度は議論可能か?」『価値観探究ジャーナル』12、311–312頁。 デール・ハンプル(1978)。「即時的信念変化と論証主張への固執の予測」。『コミュニケーション・モノグラフ』45、219–228頁。 デール・ハンプル&ジュディ・ハンプル(1978)。「証拠の信頼性」。『ディベート・イシューズ』12、4–5頁。(1978). 「証拠の信頼性」『ディベート・イシューズ』12, 4–5. デール・ハンプル. (1977). 「価値論証と証拠のモデル検証」『コミュニケーション・モノグラフ』14, 106–120. デール・ハンプル. (1977). 「トゥルーミンのモデルと三段論法」 Journal of the American Forensic Association. 14, 1–9. サリー・ジャクソンとスコット・ジェイコブズ、「会話的議論の構造:エンシメームの実用主義的基盤」。The Quarterly Journal of Speech. LXVI, 251–265. ラルフ・H・ジョンソン。『顕在的合理性:議論の実用主義理論』。Lawrence Erlbaum, 2000. ラルフ・H・ジョンソン(1996)。『非形式論理の台頭』。バージニア州ニューポートニューズ:ヴェイル・プレス ラルフ・H・ジョンソン(1999)。「形式論理と非形式論理の関係」。『論証』13(3) 265–74頁。 ラルフ・H・ジョンソン&ブレア、J・アンソニー(2006)。『論理的自己防衛』。初版はマグロウヒルライアーソン社(トロント、オンタリオ州)より1997年、1983年、1993年に刊行。再版はニューヨーク:アイディベート・プレス。 ラルフ・H・ジョンソン&ブレア、J・アンソニー(1987)。『非形式論理の現状』。『非形式論理』9号、147–51頁。 ラルフ・H・ジョンソン&ブレア、J・アンソニー (1996). 非形式論理と批判的思考. F. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, & F. Snoeck Henkemans (編), 議論理論の基礎. (pp. 383–86). ニュージャージー州マホワ: ローレンス・アーボーム・アソシエイツ ラルフ・H・ジョンソン, ラルフ・H. & ブレア, J. アンソニー. (2000) 「非形式論理:概観」『非形式論理』20(2): 93–99. ラルフ・H・ジョンソン、ラルフ・H・&ブレア、J・アンソニー(2002)。非形式論理と論理の再構成。D・ガベイ、R・H・ジョンソン、H.-J・ オールバッハ、J・ウッズ(編)『 『議論と推論の論理ハンドブック:実践への転換』所収(pp. 339–396)。エルゼビア:ノース・ホランド。 シャイム・ペレルマン、ルーシー・オルブレヒト=ティテカ(1970)。『新修辞学』、ノートルダム。 スティーブン・トゥルーミン(1958)。『議論の用途』。 スティーブン・トゥルーミン(1964)。『倫理における理性の位置』。 ダグラス・N・ウォルトン(1990)。『実践的推論:目標指向・知識基盤・行動誘導型議論』。メリーランド州サベージ:ローマン&リトルフィールド。 ダグラス・N・ウォルトン(1992)。『議論における感情の位置』。ペンシルベニア州ユニバーシティパーク:ペンシルベニア州立大学出版局。 ダグラス・N・ウォルトン(1996)。『論証構造:実用理論』。トロント:トロント大学出版局。 ダグラス・N・ウォルトン(2006)。『批判的論証の基礎』。ニューヨーク:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ダグラス・N・ウォルトン(2013)。『論証の方法』。ニューヨーク:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ダグラス・N・ウォルトン(2016)『議論の評価と証拠』シャム:シュプリンガー ジョセフ・W・ウェンツェル(1990)『議論に関する三つの視点』R・トラップ、J・シェウツ編『議論に関する視点:ウェイン・ブロックライドへの献呈論文集』(9–26頁)プロスペクトハイツ:ウェイブランド出版 ジョン・ウッズ(1980).『非形式論理とは何か』.J・A・ブレア&R・H・ジョンソン編『非形式論理:第一回国際シンポジウム』(pp. 57–68).カリフォルニア州ポイントレイエス:エッジプレス. John Woods. (2000). 非形式論理はどれほど哲学的か? Informal Logic. 20(2): 139–167. 2000 Charles Arthur Willard (1982). 論証と知識の社会的基盤. University of Alabama Press. Charles Arthur Willard (1989). 論証の理論. University of Alabama Press. チャールズ・アーサー・ウィラード(1996)。『自由主義と知識の問題:現代民主主義のための新たな修辞学』。シカゴ大学出版局。 ハラルド・ヴォルラップ(2008)。『論証の概念:知識、探究、信念、主観性、理性との関係について』。ヴュルツブルク:ケーニヒスハウゼン・ウー・ノイマン。ISBN 978-3-8260-3820-4 主要学術誌 Argumentation Argumentation in Context Informal Logic Argumentation and Advocacy(旧称 Journal of the American Forensic Association) Social Epistemology Episteme: A Journal of Social Epistemology Journal of Argument and Computation |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argumentation_theory |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099