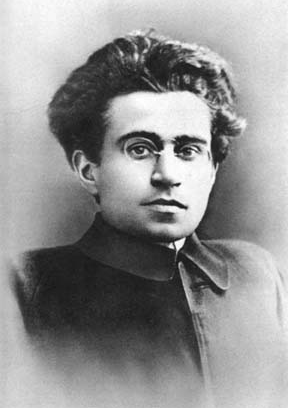

アントニオ・グラムシ

Antonio Gramsci, 1891-1937

☆ アントニオ・フランチェスコ・グラムシ(Antonio Francesco Gramsci , 英語発音:/ˈɡræmʃi/ GRAM-shee、[2] /ˈɡrɑːmʃi/ GRAHM-shee、[3] イタリア語発音:[anˈtɔːnjo franˈtʃesko ˈɡramʃi] ⓘ; 1891年1月22日 – 1937年4月27日)は、イタリアのマルクス主義哲学者、政治家。イタリア共産党の創設メンバーであり、一時党首を務めた。ベニート・ムッソリーニと ファシズムを激しく批判し、1926年に投獄され、1937年に死去する直前に釈放された。 収監中、グラムシは30冊を超えるノートと3,000ページに及ぶ歴史と分析の著作を残した。彼の『監獄ノート』は、20世紀の政治理論に極めて独創的な 貢献をした作品とされている。[4] グラムシは、マルクス主義者だけでなく、ニコロ・マキャヴェッリ、ヴィルフレド・パレート、ジョルジュ・ソレール、ベネデット・クローチェなど、多様な思 想家から洞察を得た。ノートには、イタリアの歴史とイタリアのナショナリズム、フランス革命、ファシズム、テイラー主義とフォード主義、市民社会、国家、 歴史的唯物論、民俗学、宗教、高雅文化と大衆文化など、幅広いトピックが網羅されている。 グラムシは、資本主義社会において国家と支配階級であるブルジョアジーが、文化機関を利用して富と権力を維持する仕組みを説明した文化ヘゲモニー論で最も よく知られている。グラムシの視点では、ブルジョアジーは暴力、経済力、強制ではなく、イデオロギーを用いてヘゲモニー文化を発展させる。彼はまた、正統 派マルクス主義の経済決定論から脱却を試みたため、新マルクス主義者と称されることもある。[5] 彼はマルクス主義を、伝統的な唯物論と伝統的な観念論を超越した実践の哲学であり、絶対的歴史主義であると捉える人間主義的な理解を持っていた。

| Antonio Francesco

Gramsci (UK: /ˈɡræmʃi/ GRAM-shee,[2] US: /ˈɡrɑːmʃi/ GRAHM-shee;[3]

Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo franˈtʃesko ˈɡramʃi] ⓘ; 22 January 1891 – 27 April

1937) was an Italian Marxist philosopher and politician. He was a

founding member and one-time leader of the Italian Communist Party. A

vocal critic of Benito Mussolini and fascism, he was imprisoned in

1926, and remained in prison until shortly before his death in 1937. During his imprisonment, Gramsci wrote more than 30 notebooks and 3,000 pages of history and analysis. His Prison Notebooks are considered a highly original contribution to 20th-century political theory.[4] Gramsci drew insights from varying sources—not only other Marxists but also thinkers such as Niccolò Machiavelli, Vilfredo Pareto, Georges Sorel, and Benedetto Croce. The notebooks cover a wide range of topics, including the history of Italy and Italian nationalism, the French Revolution, fascism, Taylorism and Fordism, civil society, the state, historical materialism, folklore, religion, and high and popular culture. Gramsci is best known for his theory of cultural hegemony, which describes how the state and ruling capitalist class—the bourgeoisie—use cultural institutions to maintain wealth and power in capitalist societies. In Gramsci's view, the bourgeoisie develops a hegemonic culture using ideology rather than violence, economic force, or coercion. He also attempted to break from the economic determinism of orthodox Marxist thought, and so is sometimes described as a neo-Marxist.[5] He held a humanistic understanding of Marxism, seeing it as a philosophy of praxis and an absolute historicism that transcends traditional materialism and traditional idealism. |

アントニオ・フランチェスコ・グラムシ(英語発音:/ˈɡræmʃi/

GRAM-shee、[2] /ˈɡrɑːmʃi/ GRAHM-shee、[3] イタリア語発音:[anˈtɔːnjo franˈtʃesko

ˈɡramʃi] ⓘ; 1891年1月22日 –

1937年4月27日)は、イタリアのマルクス主義哲学者、政治家。イタリア共産党の創設メンバーであり、一時党首を務めた。ベニート・ムッソリーニと

ファシズムを激しく批判し、1926年に投獄され、1937年に死去する直前に釈放された。 収監中、グラムシは30冊を超えるノートと3,000ページに及ぶ歴史と分析の著作を残した。彼の『監獄ノート』は、20世紀の政治理論に極めて独創的な 貢献をした作品とされている。[4] グラムシは、マルクス主義者だけでなく、ニコロ・マキャヴェッリ、ヴィルフレド・パレート、ジョルジュ・ソレール、ベネデット・クローチェなど、多様な思 想家から洞察を得た。ノートには、イタリアの歴史とイタリアのナショナリズム、フランス革命、ファシズム、テイラー主義とフォード主義、市民社会、国家、 歴史的唯物論、民俗学、宗教、高雅文化と大衆文化など、幅広いトピックが網羅されている。 グラムシは、資本主義社会において国家と支配階級であるブルジョアジーが、文化機関を利用して富と権力を維持する仕組みを説明した文化ヘゲモニー論で最も よく知られている。グラムシの視点では、ブルジョアジーは暴力、経済力、強制ではなく、イデオロギーを用いてヘゲモニー文化を発展させる。彼はまた、正統 派マルクス主義の経済決定論から脱却を試みたため、新マルクス主義者と称されることもある。[5] 彼はマルクス主義を、伝統的な唯物論と伝統的な観念論を超越した実践の哲学であり、絶対的歴史主義であると捉える人間主義的な理解を持っていた。 |

| Life Early life Gramsci was born in Ales, in the province of Oristano, on the island of Sardinia, the fourth of seven sons of Francesco Gramsci (1860–1937) and Giuseppina Marcias (1861–1932).[6] Francesco Gramsci was born in the small town of Gaeta, in the province of Latina, Lazio (today in the central Italian region of Lazio but at the time Gaeta was still part of Terra di Lavoro of Southern Italy), to a well-off family from the southern Italian regions of Campania and Calabria and of Arbëreshë (Italo-Albanian) descent.[7][8] Gramsci himself believed that his father's family had left Albania as recently as 1821.[9][10][11] The Albanian origin of his father's family is attested in the surname Gramsci, an Italianised form of Gramshi, which stems from the definite noun of the placename Gramsh, a small town in central-eastern Albania.[12] Gramsci's mother belonged to a Sardinian landowning family from Sorgono, in the province of Nuoro.[13] Francesco Gramsci worked as a low-level official,[7] and his financial difficulties and troubles with the police forced the family to move about through several villages in Sardinia until they finally settled in Ghilarza.[14]  Former Gymnasium Carta-Meloni in Santu Lussurgiu, which Gramsci attended from 1905 to 1907 In 1898, Gramsci's father was convicted of embezzlement and imprisoned, reducing his family to destitution. The young Gramsci had to abandon schooling and work at various casual jobs until his father's release in 1904.[15] As a boy, Gramsci suffered from health problems, particularly a malformation of the spine that stunted his growth, as his adult height was less than 5 feet,[16] and left him seriously hunchbacked. For decades, it was reported that his condition had been due to a childhood accident—specifically, having been dropped by a nanny—but more recently it has been suggested that it was due to Pott disease,[17] a form of tuberculosis that can cause deformity of the spine. Gramsci was also plagued by various internal disorders throughout his life. Gramsci started secondary school in Santu Lussurgiu and completed it in Cagliari,[18] where he lodged with his elder brother Gennaro, a former soldier whose time on the mainland had made him a militant socialist. At the time, Gramsci's sympathies did not yet lie with socialism but rather with Sardinian autonomism,[19] as well as the grievances of impoverished Sardinian peasants and miners, whose mistreatment by the mainlanders would later deeply contribute to his intellectual growth.[20][21][22] They perceived their neglect as a result of privileges enjoyed by the rapidly industrialising Northern Italy, and they tended to turn to a growing Sardinian nationalism, brutally repressed by troops from the Italian mainland,[23] as a response.[24] |

生涯 幼少期 グラムシは、サルデーニャ島オリスターノ県アレスで、フランチェスコ・グラムシ(1860年~1937年)とジュゼッピーナ・マルシアス(1861年 ~1932年)の7人の息子の4番目として生まれた。[6] フランチェスコ・グラムシは、ラツィオ州ラティーナ県(現在のイタリア中部ラツィオ州だが、当時は南イタリアのテラ・ディ・ラヴォロの一部だった)の小さ な町ガエタで、南イタリアのカンパニア州とカラブリア州、およびアルベレシェ(イタリア系アルバニア人)の裕福な家庭に生まれた。[7][8] グラムシ自身は、父親の家族がアルバニアを1821年に移住したと信じていた。[9][10][11] 父親の家族のアルバニア起源は、イタリア語化した姓「グラムシ」に由来する「グラムシ」という地名から派生した「グラムシ」という姓に裏付けられている。 [12] グラムシの母親は、ヌオロ県ソルゴノ出身のサルデーニャの土地所有者家族出身だった。[13] フランチェスコ・グラムシは下級官僚として働いていたが、経済的困難と警察とのトラブルにより、家族はサルデーニャのいくつかの村を転々とし、最終的にギ ラルツァに定住した。[14]  1905年から1907年までグラムシが通った、サント・ルッスルギウにある旧カルタ・メローニ・ギムナジウム 1898年、グラムシの父親は横領罪で有罪判決を受け、投獄され、家族は貧困に陥った。若いグラムシは学校を辞め、1904年に父親が釈放されるまで、さ まざまな臨時職を転々とする生活を送った。[15] 少年時代、グラムシは健康問題、特に脊椎の奇形に悩まされ、成長が阻害され、成人後の身長は 150 センチにも満たなかった[16] ほか、深刻な猫背になった。長年、彼の状態は幼少期の事故——具体的には乳母に落とされたこと——が原因だとされてきたが、最近ではポッテ病[17](脊 椎の変形を引き起こす結核の一種)が原因だった可能性が指摘されている。グラムシは生涯にわたって様々な内臓疾患に悩まされた。 グラムシはサンタ・ルッスールギウで中学校に通い、カリアリで卒業した[18]。そこで、本土での経験から過激な社会主義者となった兄ジェンナーロの家に 下宿した。当時、グラムシの思想は社会主義ではなく、サルデーニャの自治主義[19]や、本土の住民から虐待を受けていた貧困層のサルデーニャの農民や鉱 山労働者の不満に傾いていた。これらの経験は、のちに彼の思想形成に深く影響を与えることになった。[20][21][22] 彼らは、自分たちが無視されているのは、急速な工業化が進む北イタリアが享受する特権の結果だと考え、その対応として、イタリア本土の軍隊によって残酷に 抑圧されていた、高まりつつあったサルデーニャのナショナリズムに傾倒する傾向があった[23][24]。 |

| Turin In 1911, Gramsci won a scholarship to study at the University of Turin, sitting the exam at the same time as Palmiro Togliatti.[25] At Turin, he read literature and took a keen interest in linguistics, which he studied under Matteo Bartoli. Gramsci was in Turin while it was going through industrialization, with the Fiat and Lancia factories recruiting workers from poorer regions. Trade unions became established, and the first industrial social conflicts started to emerge.[26] Gramsci frequented socialist circles as well as associating with Sardinian emigrants on the Italian mainland. Both his earlier experiences in Sardinia and his environment on the mainland shaped his worldview. Gramsci joined the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) in late 1913, where he would later occupy a key position and observe from Turin the Russian Revolution.[27]  The Rectorate at the University of Turin, where Gramsci studied Although showing a talent for his studies, Gramsci had financial problems and poor health. Together with his growing political commitment, these led to him abandoning his education in early 1915, at age 24. By this time he had acquired an extensive knowledge of history and philosophy. At university, he had come into contact with the thought of Antonio Labriola, Rodolfo Mondolfo, Giovanni Gentile, and most importantly, Benedetto Croce, possibly the most widely respected Italian intellectual of his day. Labriola especially propounded a brand of Hegelian Marxism that he labelled "philosophy of praxis".[28] Although Gramsci later used this phrase to escape the prison censors, his relationship with this current of thought was ambiguous throughout his life. From 1914 onward, Gramsci's writings for socialist newspapers such as Il Grido del Popolo (The Cry of the People [it]) earned him a reputation as a notable journalist. In 1916 he became co-editor of the Piedmont edition of Avanti!, the Socialist Party official organ. An articulate and prolific writer of political theory, Gramsci proved a formidable commentator, writing on all aspects of Turin's social and political events.[29] Gramsci was at this time also involved in the education and organisation of Turin workers; he spoke in public for the first time in 1916 and gave talks on topics such as Romain Rolland, the French Revolution, the Paris Commune, and the emancipation of women. In the wake of the arrest of Socialist Party leaders that followed the revolutionary riots in August 1917, Gramsci became one of Turin's leading socialists; he was elected to the party's provisional committee and also made editor of Il Grido del Popolo.[30] In April 1919, with Togliatti, Angelo Tasca and Umberto Terracini, Gramsci set up the weekly newspaper L'Ordine Nuovo (The New Order). In October of the same year, despite being divided into various hostile factions, the PSI moved by a large majority to join the Third International. Vladimir Lenin saw the L'Ordine Nuovo group as closest in orientation to the Bolsheviks, and it received his backing against the anti-parliamentary programme of a left communist, Amadeo Bordiga.[31] In the course of tactical debates within the party, Gramsci's group mainly stood out due to its advocacy of workers' councils, which had come into existence in Turin spontaneously during the large strikes of 1919 and 1920. For Gramsci, these councils were the proper means of enabling workers to take control of the task of organising production, and saw them as preparing "the whole class for the aims of conquest and government".[32] Although he believed his position at this time to be in keeping with Lenin's policy of "All Power to the Soviets",[33] his stance that these Italian councils were communist rather than just one organ of political struggle against the bourgeoisie, was attacked by Bordiga for betraying a syndicalist tendency influenced by the thought of Georges Sorel and Daniel De Leon. By the time of the defeat of the Turin workers in spring 1920, Gramsci was almost alone in his defence of the councils. |

トリノ 1911年、グラムシはトリノ大学に奨学金を得て入学し、パルミロ・トリアッティと同じ時期に試験を受けた[25]。トリノでは文学を学び、マッテオ・バ ルトリのもとで言語学に熱心に打ち込んだ。グラムシがトリノにいた頃、この都市は工業化が進んでおり、フィアットやランチアなどの工場は貧しい地域から労 働者を募集していた。労働組合が組織され、最初の産業紛争が勃発し始めた。[26] グラムシは社会主義者の集まりに出入りする一方、イタリア本土のサルデーニャ島出身移民とも交流した。サルデーニャでの経験と本土の環境は、彼の世界観を 形成した。グラムシは1913年末にイタリア社会党(PSI)に入党し、後に同党の要職に就き、トリノからロシア革命を観察した。[27]  グラムシが学んだトリノ大学 学業に才能を発揮したグラムシだったが、経済的な問題と健康上の問題を抱えていた。政治への関心が強まる中、1915年初頭、24歳の若さで学業を断念し た。この頃には、歴史と哲学に関する幅広い知識を獲得していた。大学では、アントニオ・ラブリオラ、ロドルフォ・モンドルフォ、ジョヴァンニ・ジェン ティーレ、そして最も重要なベネデット・クローチェ(おそらく当時最も尊敬されていたイタリアの知識人)の思想と接触した。特にラブリオラは、ヘーゲル主 義的マルクス主義の一派を「実践の哲学」と称して提唱した。[28] グラムシは後にこの表現を刑務所の検閲を逃れるために使用したが、この思想潮流との関係は生涯を通じて曖昧なままだった。 1914年以降、グラムシは、Il Grido del Popolo(人民の叫び)などの社会主義新聞に記事を執筆し、著名なジャーナリストとしての評判を得た。1916年には、社会党の機関紙である Avanti! のピエモンテ版共同編集者になった。政治理論の明晰で多作な作家として、グラムシは強力な評論家として頭角を現し、トリノの社会・政治情勢のあらゆる側面 について執筆した。[29] グラムシはこの時期、トリノの労働者の教育と組織化にも関与し、1916年に初めて公の場で演説し、ロマン・ロラン、フランス革命、パリ・コミューン、女 性の解放などについて講演した。1917年8月の革命的暴動に続く社会党指導部の逮捕後、グラムシはトリノの主要な社会主義者の一人となり、党の臨時委員 会に選出され、『イル・グリド・デル・ポポロ』の編集長にも就任した。[30] 1919年4月、グラムシはトリアッティ、アンジェロ・タスカ、ウンベルト・テラチーニとともに、週刊新聞『L'Ordine Nuovo(新しい秩序)』を創刊した。同年10月、PSIは様々な対立する派閥に分裂していたものの、大多数の賛成で第三インターナショナルへの加入を 決議した。ウラジーミル・レーニンは『オルディネ・ヌオーヴォ』グループをボリシェヴィキに最も近い立場と見なし、左派共産主義者アマデオ・ボルディガの 反議会主義的プログラムに対して支援を表明した。[31] 党内の戦術的議論の中で、グラムシのグループは主に、1919年と1920年の大規模なストライキ中にトリノで自発的に生まれた労働者評議会の支持で目 立った。グラムシにとって、これらの評議会は労働者が生産の組織化を掌握するための適切な手段であり、これらが「征服と統治の目的のために全階級を準備す る」ものと見なしていた。[32] 彼はこの時点での自身の立場がレーニンの「ソビエトにすべての権力」政策と一致していると信じていたが、[33] これらのイタリアの評議会がブルジョアジーに対する政治的闘争の単なる一機関ではなく共産主義的であるとの主張は、ジョルジュ・ソレルとダニエル・デ・レ オンの思想に影響を受けたシンジカル主義的傾向を裏切るものとしてボルディガから批判された。1920年春、トリノの労働者が敗北した頃には、評議会を擁 護する者はグラムシほぼ一人だけになっていた。 |

Communist Party of Italy Julia Schucht with sons The failure of the workers' councils to develop into a national movement convinced Gramsci that a Communist party in the Leninist sense was needed. The group around L'Ordine Nuovo declaimed incessantly against the PSI's centrist leadership and ultimately allied with Bordiga's far larger abstentionist faction. On 21 January 1921, in the town of Livorno (Leghorn), the Communist Party of Italy (Partito Comunista d'Italia, PCd'I) was founded. In opposition to Bordiga, Gramsci supported the Arditi del Popolo, a militant anti-fascist group which struggled against the Blackshirts. Gramsci would be a leader of the party from its inception but was subordinate to Bordiga, whose emphasis on discipline, centralism and purity of principles dominated the party's programme until the latter lost the leadership in 1924.[34] In 1922, Gramsci travelled to Russia as a representative of the new party. Here, he met Julia Schucht (Yulia Apollonovna Schucht, 1896–1980), a young Jewish[35] violinist whom he married in 1923 and with whom he had two sons, Delio (1924–1982) and Giuliano (1926–2007).[36] Gramsci never saw his second son.[37]  A commemorative plaque for Gramsci in Mokhovaya Street 16, Moscow. Translated, the inscription reads: "In this building in 1922–1923 worked the eminent figure of international communism and the labour movement and founder of the Italian Communist Party, Antonio Gramsci." The Russian mission coincided with the advent of fascism in Italy, and Gramsci returned with instructions to foster, against the wishes of the PCd'I leadership, a united front of leftist parties against fascism. Such a front would ideally have had the PCd'I at its centre, through which Moscow would have controlled all the leftist forces, but others disputed this potential supremacy, as socialists had a significant, while communists seemed relatively young and too radical. Many believed that an eventual coalition led by communists would have functioned too remotely from political debate, and thus would have run the risk of isolation. In late 1922 and early 1923, Benito Mussolini's government embarked on a campaign of repression against the opposition parties, arresting most of the PCd'I leadership, including Bordiga. At the end of 1923, Gramsci travelled from Moscow to Vienna, where he tried to revive a party torn by factional strife. In 1924, Gramsci, now recognised as head of the PCd'I, gained election as a deputy for the Veneto. He started organizing the launch of the official newspaper of the party, called L'Unità (Unity), living in Rome while his family stayed in Moscow. At its Lyon Congress in January 1926, Gramsci's theses calling for a united front to restore democracy to Italy were adopted by the party. In 1926, Joseph Stalin's manoeuvres inside the Bolshevik party moved Gramsci to write a letter to the Comintern in which he deplored the opposition led by Leon Trotsky but also underlined some presumed faults of the leader. Togliatti, in Moscow as a representative of the party, received the letter, opened it, read it, and decided not to deliver it. This caused a difficult conflict between Gramsci and Togliatti which they never completely resolved.[38] |

イタリア共産党 ジュリア・シュクトと息子たち 労働者評議会が全国的な運動に発展しなかったことで、グラムシはレーニン主義的な意味での共産党の必要性を確信した。L'Ordine Nuovo を中心としたグループは、PSI の中道的な指導部を執拗に非難し、最終的には、はるかに大きな規模を誇るボルディガの棄権派と提携した。1921年1月21日、リヴォルノ(レグホーン) でイタリア共産党(Partito Comunista d『Italia, PCd』I)が結成された。ボルディガに反対し、グラムシは黒シャツ団と闘った過激な反ファシスト集団「アルディティ・デル・ポポロ」を支持した。グラム シは党の設立時から指導者の一人だったが、ボルディガの規律、中央集権、原則の純粋性を重視する方針が党のプログラムを支配し、1924年にボルディガが 指導権を失うまで、彼に従属していた。[34] 1922年、グラムシは新党の代表としてロシアを訪れた。ここで彼は、ユリア・シュフト(ユリア・アポロンノヴナ・シュフト、1896–1980)という 若いユダヤ人[35]のヴァイオリニストと出会い、1923年に結婚し、2人の息子、デリオ(1924–1982)とジュリアーノ(1926–2007) をもうけた。[36] グラムシは2人目の息子に会うことはなかった。[37]  モスクワのモホヴォヤ通り16番地にあるグラムシの記念碑。碑文は「1922年から1923年まで、この建物で、国際共産主義運動および労働運動の著名人物であり、イタリア共産党の創設者であるアントニオ・グラムシが活動した」と訳される。 ロシアへの派遣はイタリアでのファシズムの台頭と時期を同じくし、グラムシはPCd『I指導部の意向に反して、ファシズムに対抗する左派政党の統一戦線を 築くよう指示を受けて帰国した。この統一戦線は理想的にはPCd』Iを中核とし、モスクワがすべての左派勢力を支配する構造だったが、社会主義者が大きな 勢力を持っていたのに対し、共産党は比較的若く過激すぎると見られていたため、この潜在的な優位性を疑問視する声もあった。多くの人々は、共産党が主導す る連合は政治的議論からあまりにも遠ざかり、孤立する危険性があると信じていた。 1922 年後半から 1923 年前半にかけて、ベニート・ムッソリーニ政権は、ボルディガを含む PCd'I 指導部のほとんどを逮捕し、野党に対する弾圧キャンペーンを開始した。1923年末、グラムシはモスクワからウィーンへ移動し、派閥対立で分裂した党の再 建を試みた。1924年、PCd『Iの指導者として認められたグラムシは、ヴェネト州の代議士に選出された。彼はローマで暮らしながら、党の公式新聞 『L』Unità』(統一)の発行を組織し始めた。1926年1月のリヨン大会で、イタリアに民主主義を回復するための統一戦線を呼びかけたグラムシの論 文が党によって採択された。 1926年、ヨシフ・スターリンのボルシェビキ党内での動きを受けて、グラムシはコミンテルンに手紙を書き、レオン・トロツキーが率いる反対派を非難する とともに、その指導者のいくつかの欠点も指摘した。モスクワに党代表として滞在していたトリアッティは、この手紙を受け取り、開封して読んだ後、配達しな いことを決めた。これにより、グラムシとトリアッティの間で解決されないままの深刻な対立が生じた。[38] |

Imprisonment and death Gramsci's grave at the Cimitero Acattolico in Rome On 9 November 1926, the Fascist government enacted a new wave of emergency laws, taking as a pretext an alleged attempt on Mussolini's life that had occurred several days earlier. The Fascist police arrested Gramsci, despite his parliamentary immunity, and brought him to the Roman prison Regina Coeli. At his trial, Gramsci's prosecutor stated: "For twenty years we must stop this brain from functioning."[39] He received an immediate sentence of five years in confinement on the island of Ustica, and the following year he received a sentence of 20 years' imprisonment in Turi, Apulia, near Bari. Over 11 years in prison, his health deteriorated. Over this period, "his teeth fell out, his digestive system collapsed so that he could not eat solid food ... he had convulsions when he vomited blood and suffered headaches so violent that he beat his head against the walls of his cell."[40][41] An international campaign, organised by Piero Sraffa at Cambridge University and Gramsci's sister-in-law Tatiana, was mounted to demand Gramsci's release.[42] In 1933, he was moved from the prison at Turi to a clinic at Formia;[43] he was still being denied adequate medical attention.[44] Two years later, he was moved to the Quisisana clinic in Rome. He was due for release on 21 April 1937 and planned to retire to Sardinia for convalescence, but a combination of arteriosclerosis, pulmonary tuberculosis, high blood pressure, angina, gout, and acute gastric disorders meant that he was too ill to move.[44] Gramsci died on 27 April 1937, at the age of 46. His ashes are buried in the Cimitero Acattolico in Rome. By moving Gramsci from prison to hospital when he became very ill, the Mussolini regime was attempting to avoid the accusation that it was his incarceration that caused his death. Nevertheless, his death was linked directly to prison conditions.[45] Gramsci's grandson, Antonio Jr., speculated that Gramsci had been working with the Soviet government to facilitate a move to Moscow, but changed course as the political climate in Russia intensified in 1936.[46] |

投獄と死 ローマのカトリック墓地にあるグラムシの墓 1926年11月9日、ファシスト政権は、数日前に起こったムッソリーニの暗殺未遂事件を口実として、新たな緊急事態法を制定した。ファシスト警察は、グ ラムシの議会の免責特権を無視して彼を逮捕し、ローマのレジーナ・コエリ刑務所に収監した。裁判で、グラムシの検察官は「この頭脳の機能を20年間停止さ せなければならない」と述べた。[39] 彼はウスティカ島での5年間の禁固刑を即決で言い渡され、翌年にはバーリ近郊のアプリア州トゥリでの20年間の禁固刑を言い渡された。 11 年以上にわたる刑務所生活で、彼の健康は悪化しました。この期間、「彼は歯が抜け落ち、消化器系が機能しなくなり、固形物を食べることができなくなっ た... 血を吐いて痙攣を起こし、激しい頭痛に悩まされ、独房の壁に頭を打ち付けた」と伝えられています。[40][41] ケンブリッジ大学のピエロ・スラッファとグラムシの義妹タチアナが組織した国際的なキャンペーンが、グラムシの釈放を要求した。[42] 1933年、彼はトゥリ刑務所からフォルミアのクリニックに移送されたが、[43] 適切な医療措置は依然として拒否されていた。[44] 2年後、彼はローマのクイジサナクリニックに移送された。1937年4月21日に釈放予定で、サルデーニャで療養する計画だったが、動脈硬化、肺結核、高 血圧、狭心症、痛風、急性胃腸障害の複合症状により、移動不能な状態だった。[44] グラムシは1937年4月27日、46歳で死去した。彼の遺灰はローマのカトリック墓地に埋葬されている。グラムシが重病になった際に、ムッソリーニ政権 は彼を刑務所から病院に移送することで、彼の死は投獄が原因であるとの非難を回避しようとした。しかし、彼の死は直接的に刑務所の環境と関連していた。 [45] グラムシの孫、アントニオ・ジュニアは、グラムシがソビエト政府と協力してモスクワへの移送を計画していたが、1936年にロシアの政治情勢が緊迫化した ため方針を変更したと推測している。[46] |

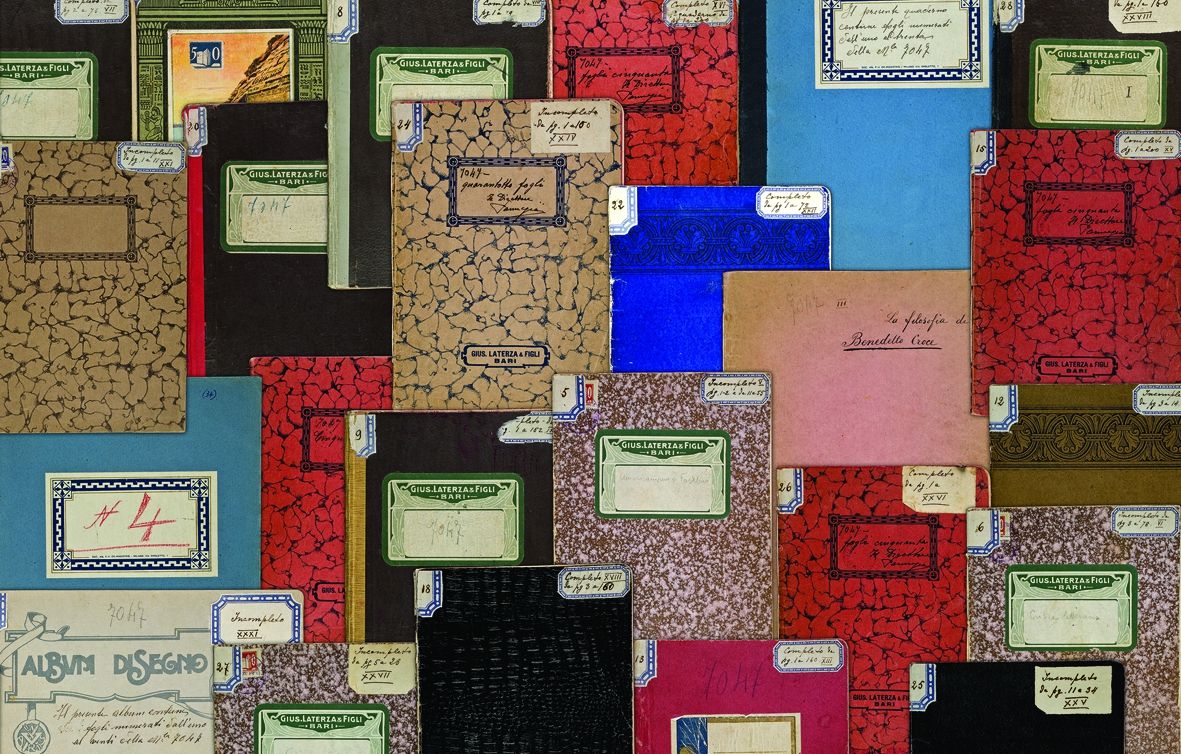

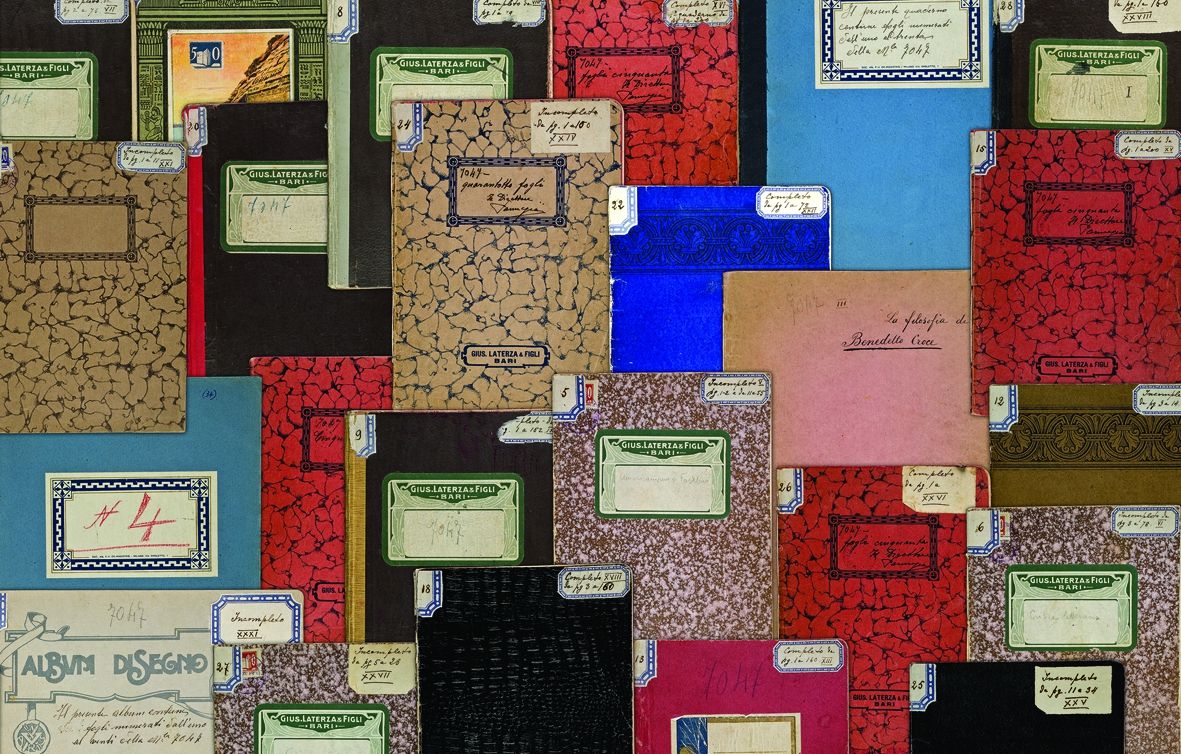

Philosophical work Gramsci's many prison notebooks Gramsci was one of the most influential Marxist thinkers of the 20th century, and a particularly key thinker in the development of Western Marxism. He wrote more than 30 notebooks and 3,000 pages of history and analysis during his imprisonment. These writings, known as the Prison Notebooks, contain Gramsci's tracing of Italian history and nationalism, as well as some ideas in Marxist theory, critical theory, and educational theory associated with his name, such as: Cultural hegemony as a means of maintaining and legitimising the capitalist state The need for popular workers' education to encourage the development of intellectuals from the working class An analysis of the modern capitalist state that distinguishes between political society, which dominates directly and coercively, and civil society, where leadership is constituted through consent Absolute historicism A critique of economic determinism that opposes fatalistic interpretations of Marxism A critique of philosophical materialism |

哲学的著作 グラムシの多くの刑務所ノート グラムシは、20 世紀で最も影響力のあるマルクス主義思想家の一人であり、西洋マルクス主義の発展において特に重要な思想家でした。彼は、投獄中に 30 冊以上のノートと 3,000 ページ以上に及ぶ歴史と分析の文章を残しました。これらの著作は「刑務所ノート」として知られており、イタリアの歴史とナショナリズムの軌跡、そしてマル クス主義理論、批判理論、教育理論に関するグラムシの考えが記されている。 資本主義国家を維持し、その正当性を確保する手段としての文化ヘゲモニー 労働者階級から知識人を育成するための、大衆的な労働者教育の必要性 直接的かつ強制的に支配する政治社会と、合意によってリーダーシップが形成される市民社会とを区別する、現代資本主義国家の分析 絶対的歴史主義 マルクス主義の宿命論的解釈に反対する、経済決定論の批判 哲学的唯物論の批判 |

| Hegemony Further information: Cultural hegemony Hegemony was a term previously used by Marxists such as Vladimir Lenin to denote the political leadership of the working class in a democratic revolution.[47]: 15–17 Gramsci greatly expanded this concept, developing an acute analysis of how the ruling capitalist class—the bourgeoisie—establishes and maintains its control.[47]: 20 Classical Marxism had predicted that socialist revolution was inevitable in capitalist societies. By the early 20th century, no such revolution had occurred in the most advanced nations, and those revolutions of 1917–1923, such as in Germany or the Biennio Rosso in Italy, had failed. As capitalism seemed more entrenched than ever, Gramsci suggested that it maintained control not just through violence and political and economic coercion but also through ideology. The bourgeoisie developed a hegemonic culture, which propagated its own values and norms so that they became the common sense values of all. People in the working class and other classes identified their own good with the good of the bourgeoisie and helped to maintain the status quo rather than revolting. To counter the notion that bourgeois values represented natural or normal values for society, the working class needed to develop a culture of its own. While Lenin held that culture was ancillary to political objectives, Gramsci saw it as fundamental to the attainment of power that cultural hegemony be achieved first. In Gramsci's view, a class cannot dominate in modern conditions by merely advancing its own narrow economic interests, and neither can it dominate purely through force and coercion.[48] Rather, it must exert intellectual and moral leadership, and make alliances and compromises with a variety of forces.[48] Gramsci calls this union of social forces a historic bloc, taking a term from Georges Sorel. This bloc forms the basis of consent to a certain social order, which produces and re-produces the hegemony of the dominant class through a nexus of institutions, social relations, and ideas.[48] |

ヘゲモニー 詳細情報:文化的ヘゲモニー ヘゲモニーは、かつてウラジーミル・レーニンなどのマルクス主義者が、民主革命における労働者階級の政治的指導力を指す用語として用いていた[47]: 15–17 。グラムシは、この概念を大幅に拡大し、支配階級であるブルジョアジーがどのように支配を確立し、維持しているかを鋭く分析した。[47]: 20 古典的マルクス主義は、資本主義社会では社会主義革命は避けられないと予測していました。20 世紀初頭までに、先進国ではそのような革命は起こらず、1917 年から 1923 年にかけてのドイツやイタリアの「ビエンニオ・ロッソ」などの革命は失敗に終わりました。資本主義がかつてないほど定着しているように見えたため、グラム シは、資本主義は暴力や政治的・経済的強制だけでなく、イデオロギーによって支配を維持していると指摘した。ブルジョアジーは、自らの価値観や規範を普及 させる覇権的文化を発展させ、それをすべての人の常識的な価値観とした。労働者階級やその他の階級の人々は、自らの幸福をブルジョアジーの幸福と同一視 し、反乱を起こすことなく現状を維持する一翼を担った。 ブルジョアジーの価値観が社会にとって当然の、あるいは正常な価値観であるという考えに対抗するには、労働者階級は独自の文化を育む必要があった。レーニ ンは文化は政治的目的の付随的なものであると主張したが、グラムシは、文化のヘゲモニーをまず確立することが権力の獲得に不可欠であると考えた。グラムシ の見解では、現代の状況では、ある階級は、自らの狭い経済的利益を追求するだけでは支配権を獲得することはできず、また、力や強制力だけで支配することも できない。[48] むしろ、知的、道徳的なリーダーシップを発揮し、さまざまな勢力との同盟や妥協を図らなければならない[48]。グラムシは、この社会勢力の連合を、ジョ ルジュ・ソレルから借用した「歴史的ブロック」と呼んでいる。このブロックは、特定の社会秩序に対する同意の基盤を形成し、制度、社会関係、思想の結びつ きを通じて、支配階級のヘゲモニーを生み出し、再生産する[48]。 |

| Intellectuals and education Gramsci gave much thought to the role of intellectuals in society.[49] He stated that all men are intellectuals, in that all have intellectual and rational faculties, but not all men have the social function of intellectuals.[50] He saw modern intellectuals not as talkers but as practical-minded directors and organisers who produced hegemony through ideological apparatuses such as education and the media. Furthermore, he distinguished between a traditional intelligentsia, which sees itself (in his view, wrongly) as a class apart from society, and the thinking groups that every class produces from its own ranks organically.[49] Such organic intellectuals do not simply describe social life in accordance with scientific rules but instead articulate, through the language of culture, the feelings and experiences which the masses could not express for themselves. To Gramsci, it was the duty of organic intellectuals to speak to the obscured precepts of folk wisdom, or common sense (senso comune), of their respective political spheres. These intellectuals would represent excluded social groups of a society, or what Gramsci referred to as the subaltern.[51] In line with Gramsci's theories of cultural hegemony, he argued that capitalist power needed to be challenged by building a counter-hegemony. By this, he meant that, as part of the war of position, the organic intellectuals and others within the working-class, need to develop alternative values and an alternative ideology in contrast to bourgeois ideology. He argued that the reason this had not needed to happen in Russia was because the Russian ruling class did not have genuine cultural hegemony. So the Bolsheviks were able to carry out a war of manoeuvre (the Russian Revolution of 1917) relatively easily because ruling-class hegemony had never been fully achieved. He believed that a final war of manoeuvre was only possible, in the developed and advanced capitalist societies, when the war of position had been won by the organic intellectuals and the working class building a counter-hegemony.[citation needed] The need to create a working-class culture and a counter-hegemony relates to Gramsci's call for a kind of education that could develop working-class intellectuals, whose task was not to introduce Marxist ideology into the consciousness of the proletariat as a set of foreign notions but to renovate the existing intellectual activity of the masses and make it natively critical of the status quo. His ideas about an education system for this purpose correspond with the notion of critical pedagogy and popular education as theorized and practised in later decades by Paulo Freire in Brazil, and have much in common with the thought of Frantz Fanon. For this reason, partisans of adult and popular education consider Gramsci's writings and ideas important to this day.[52] |

知識人と教育 グラムシは、社会における知識人の役割について深く考察した[49]。彼は、すべての人は知性と理性を持っているという点で知識人であるものの、すべての 人が知識人の社会的機能を持っているわけではないと述べた[50]。彼は、現代の知識人を、ただ話をする者ではなく、教育やメディアなどのイデオロギー装 置を通じてヘゲモニーを生み出す、現実的な考えを持つ指導者や組織者であると見なした。さらに、彼は、社会から分離した階級として自己認識する伝統的なイ ンテリゲンツィア(彼の見解では誤った認識)と、各階級が自らの内部から有機的に生み出す思考集団とを区別した。[49] こうした有機的知識人は、科学的規則に従って社会生活を単に記述するのではなく、大衆が自ら表現できない感情や経験を、文化の言語を通じて表現する。グラ ムシにとって、有機的知識人の義務は、それぞれの政治分野における民衆の知恵や常識(senso comune)の隠された教訓を語ることだった。こうした知識人は、社会から排除された社会集団、つまりグラムシが「サバルタン」と呼んだ人々を代表する ものだ。[51] グラムシの文化ヘゲモニーの理論に沿って、彼は、反ヘゲモニーを構築することによって資本主義の権力に挑む必要があると主張した。つまり、位置戦争の一環 として、有機的知識人や労働者階級内の他の者たちは、ブルジョアイデオロギーとは対照的な、別の価値観やイデオロギーを育む必要がある、と彼は考えた。彼 は、ロシアではこのようなことが必要なかったのは、ロシアの支配階級が真の文化ヘゲモニーを持っていなかったからだと主張した。そのため、ボルシェビキ は、支配階級のヘゲモニーが完全に確立されていなかったため、比較的容易に機動戦争(1917年のロシア革命)を遂行することができた。彼は、最終的な機 動戦争は、有機的知識人と労働階級が反ヘゲモニーを構築して位置戦争に勝利した場合にのみ、先進資本主義社会で可能になると考えていた。 労働者階級の文化と反ヘゲモニーを構築する必要性は、グラムシが提唱した、労働者階級の知識人を育成する教育と関連している。その知識人の任務は、プロレ タリアートの意識にマルクス主義のイデオロギーを外来の概念として導入することではなく、大衆の既存の知的活動を刷新し、現状に対して本質的に批判的なも のにするということだった。この目的のための教育システムに関する彼の考えは、後年のブラジルでパウロ・フレイレが理論化し実践した批判的教育学と人民教 育の概念と一致し、フランツ・ファノン思想とも多くの共通点がある。このため、成人教育と人民教育の支持者は、グラムシの著作と思想を今日でも重要視して いる。[52] |

| State and civil society Gramsci's theory of hegemony is tied to his conception of the capitalist state. Gramsci does not understand the state in the narrow sense of the government. Instead, he divides it between political society (the police, the army, legal system, etc.)—the arena of political institutions and legal constitutional control—and civil society (the family, the education system, trade unions, etc.)—commonly seen as the private or non-state sphere, which mediates between the state and the economy.[53] He stresses that the division is purely conceptual and that the two often overlap in reality.[54] Gramsci posits that the capitalist state rules through force plus consent: political society is the realm of force and civil society is the realm of consent. He argues that under modern capitalism the bourgeoisie can maintain its economic control by allowing certain demands made by trade unions and mass political parties within civil society to be met by the political sphere. Thus, the bourgeoisie engages in passive revolution by going beyond its immediate economic interests and allowing the forms of its hegemony to change. Gramsci posits that movements such as reformism and fascism, as well as the scientific management and assembly line methods of Frederick Winslow Taylor and Henry Ford respectively, are examples of this. Drawing from Niccolò Machiavelli, Gramsci argues that the modern Prince—the revolutionary party—is the force that will allow the working class to develop organic intellectuals and an alternative hegemony within civil society. For Gramsci, the complex nature of modern civil society means that a war of position, carried out by revolutionaries through political agitation, the trade unions, advancement of proletarian culture, and other ways to create an opposing civil society was necessary alongside a war of manoeuvre—a direct revolution—in order to have a successful revolution without danger of a counter-revolution or degeneration. Despite his claim that the lines between the two may be blurred, Gramsci rejects the state worship that results from equating political society with civil society, as was done by the Jacobins and fascists. He believes the proletariat's historical task is to create a regulated society, where political society is diminished and civil society is expanded. He defines the withering away of the state as the full development of civil society's ability to regulate itself.[53] |

国家と市民社会 グラムシのヘゲモニー理論は、彼の資本主義国家の概念と結びついている。グラムシは、国家を政府という狭い意味では理解していない。代わりに、彼は国家を 政治社会(警察、軍隊、法体系など)——政治的機関と法的憲法的統制の領域——と市民社会(家族、教育制度、労働組合など)——通常、私的または非国家の 領域と見なされ、国家と経済の間に仲介する役割を果たす——に分けます。[53] 彼は、この区分は純粋に概念的なものであり、現実には両者が重なり合うことが多いと強調しています。[54] グラムシは、資本主義国家は力と同意によって支配していると主張している。政治社会は力の領域であり、市民社会は同意の領域である。彼は、現代資本主義の 下では、ブルジョアジーは、市民社会における労働組合や大衆政党の特定の要求を政治領域で満たすことで、経済支配を維持することができると主張している。 このように、ブルジョアジーは、その当面の経済的利益を超えて、そのヘゲモニーの形態の変化を容認することで、受動的革命に関与している。グラムシは、改 革主義やファシズム、フレデリック・ウィンズロー・テイラーやヘンリー・フォードによる科学的管理や組立ライン方式などの運動が、その例だと主張してい る。 ニッコロ・マキャヴェッリから着想を得たグラムシは、現代の「王子」、つまり革命政党は、労働者階級が市民社会の中で有機的な知識層と代替的なヘゲモニー を育成する力をもたらす存在だと主張している。グラムシにとって、現代市民社会の複雑な性質は、革命家が政治的扇動、労働組合、プロレタリア文化の進展、 対立する市民社会を創造する他の手段を通じて行う「位置戦争(陣地戦)」と、直接革命である「機動戦争」を並行して展開する必要があることを意味する。こ れにより、反革命や退廃の危険なしに革命を成功させることができる。 彼は、両者の境界線が曖昧になる可能性を認めつつも、政治社会と市民社会を同列に扱うことで生じる国家崇拝を、ジャコバン派やファシストのように拒否し た。彼は、プロレタリアートの歴史的任務は、政治社会が縮小され市民社会が拡大される規制された社会を創造することだと考えた。彼は、国家の消滅を、市民 社会が自己規制する能力の完全な発展と定義した。[53] |

| Historicism Like the young Marx, Gramsci was an emphatic proponent of historicism.[55] In Gramsci's view, all meaning derives from the relation between human practical activity (or praxis) and the objective historical and social processes of which it is a part. Ideas cannot be understood outside their social and historical context, apart from their function and origin. The concepts by which we organise our knowledge of the world do not derive primarily from our relation to objects, but rather from the social relations between the users of those concepts. As a result, there is no such thing as an unchanging human nature but only historically variable social relationships. Furthermore, philosophy and science do not reflect a reality independent of man. Rather, a theory can be said to be true when, in any given historical situation, it expresses the real developmental trend of that situation. For the majority of Marxists, truth was truth no matter when and where it was known, and scientific knowledge, which included Marxism, accumulated historically as the advance of truth in this everyday sense. In this view, Marxism (or the Marxist theory of history and economics) did not belong to the illusory realm of the superstructure because it is a science. In contrast, Gramsci believed Marxism was true in a socially pragmatic sense: by articulating the class consciousness of the proletariat, Marxism expressed the truth of its times better than any other theory. This anti-scientistic and anti-positivist stance was indebted to the influence of Benedetto Croce. At the same time, it should be underlined that Gramsci's absolute historicism broke with Croce's tendency to secure a metaphysical synthesis of historical destiny. Although Gramsci repudiates the charge, his historical account of truth has been criticised as a form of relativism.[56] |

歴史主義 若いマルクスと同様に、グラムシは歴史主義の熱烈な支持者だった[55]。グラムシの見解では、すべての意味は、人間の実際的な活動(またはプラクシス) と、それが一部である客観的な歴史的・社会的プロセスとの関係から派生する。アイデアは、その社会的・歴史的文脈から切り離して、その機能や起源から離れ て理解することはできない。私たちが世界の知識を組織化する概念は、主に物体との関係から派生するのではなく、その概念の使用者間の社会的関係から派生す る。その結果、不変の人間性など存在せず、歴史的に変動する社会的関係のみが存在する。さらに、哲学や科学は人間から独立した現実を反映するものではな い。むしろ、ある歴史的状況において、その状況の現実の発展傾向を表現する理論は、真であると言える。 大多数のマルクス主義者にとって、真実はいつどこで知られても真実であり、マルクス主義を含む科学的知識は、この日常的な意味での真実の進展として歴史的 に蓄積されてきた。この見方では、マルクス主義(またはマルクス主義の歴史と経済の理論)は、科学であるため、虚構的な上部構造の領域に属さない。これに 対し、グラムシはマルクス主義が社会的に実践的な意味での真実であると考えた。プロレタリアートの階級意識を表現することで、マルクス主義は他のいかなる 理論よりもその時代の真実をよりよく表現したからだ。この反科学主義的・反実証主義的立場は、ベネデット・クローチェの影響を受けていた。同時に、グラム シの絶対的歴史主義が、クロチェの歴史的運命のメタフィジカルな総合を確立しようとする傾向と決別した点も強調すべきだ。グラムシはこれを否定している が、彼の歴史的真実の叙述は相対主義の一形態として批判されてきた。[56] |

| Critique of economism In a pre-prison article titled "The Revolution against Das Kapital", Gramsci wrote that the October Revolution in Russia had invalidated the idea that socialist revolution had to await the full development of capitalist forces of production.[57] This reflected his view that Marxism was not a determinist philosophy. The principle of the causal primacy of the forces of production was a misconception of Marxism. Both economic changes and cultural changes are expressions of a basic historical process, and it is difficult to say which sphere has primacy over the other. The belief from the earliest years of the workers' movement that it would inevitably triumph due to historical laws was a product of the historical circumstances of an oppressed class restricted mainly to defensive action. This fatalistic doctrine must be abandoned as a hindrance once the working class becomes able to take the initiative. Because Marxism is a philosophy of praxis, it cannot rely on unseen historical laws as the agents of social change. History is defined by human praxis and therefore includes human will. Nonetheless, willpower cannot achieve anything it likes in any given situation: when the consciousness of the working class reaches the stage of development necessary for action, it will encounter historical circumstances that cannot be arbitrarily altered. It is not predetermined by historical inevitability as to which of several possible developments will take place as a result. His critique of economic determinism extended to that practised by the syndicalists of the Italian trade unions. He believed that many trade unionists had settled for a reformist, gradualist approach in that they had refused to struggle on the political front in addition to the economic front. For Gramsci, much as the ruling class can look beyond its own immediate economic interests to reorganise the forms of its own hegemony, so must the working class present its own interests as congruous with the universal advancement of society. While Gramsci envisioned the trade unions as one organ of a counter-hegemonic force in a capitalist society, the trade union leaders simply saw these organizations as a means to improve conditions within the existing structure. Gramsci referred to the views of these trade unionists as vulgar economism, which he equated to covert reformism and liberalism. |

経済主義の批判 刑務所に入る前に書いた「資本論に対する革命」という記事の中で、グラムシは、ロシアの10月革命によって、社会主義革命は資本主義の生産力の発展を待つ 必要があるという考えは誤りであると述べた[57]。これは、マルクス主義は決定論的な哲学ではないという彼の見解を反映したものだった。生産力要因の因 果的優先性の原則は、マルクス主義の誤解だった。経済的変化と文化的変化は、基本的な歴史的過程の表現であり、どちらの領域が優先するかを断定することは 困難だ。 労働者運動の初期から、歴史的法則により必然的に勝利するとの信念は、主に防御的行動に限定された抑圧された階級の歴史的状況の産物だった。この宿命論的 教義は、労働者が主体性を獲得した時点で、障害として放棄されなければならない。マルクス主義は実践の哲学であるため、社会変革のエージェントとして見え ない歴史的法則に依存することはできない。歴史は人間の実践によって定義され、したがって人間の意志を含む。とはいえ、意志力は何でも好きなことを、どん な状況でも達成できるわけではない。労働者階級の意識が行動に必要な発展段階に達すると、恣意的に変更できない歴史的状況に出くわす。その結果、いくつか の可能な展開のうちどれが起こるかは、歴史的必然性によってあらかじめ決まっているわけではない。 彼の経済決定論に対する批判は、イタリアの労働組合のシンジカリストたちが実践していたものにも及んだ。彼は、多くの労働組合活動家が、経済面での闘争だ けでなく、政治面での闘争も拒否し、改革主義的、漸進主義的なアプローチに甘んじているとの見解を示した。グラムシは、支配階級が自らの当面の経済的利益 を超えて、自らのヘゲモニーの形態を再編成することができるのと同様に、労働者階級も、自らの利益が社会の普遍的な進歩と一致するものとして提示しなけれ ばならないと主張した。グラムシは、労働組合を資本主義社会における反ヘゲモニー勢力の機関の一つとして捉えていたが、労働組合の指導者たちは、これらの 組織を既存の構造内での条件改善の手段としてしか見ていなかった。グラムシは、これらの労働組合員の立場を「粗俗な経済主義」と呼び、隠れた改革主義や自 由主義と同等視した。 |

| Critique of materialism By virtue of his belief that human history and collective praxis determine whether any philosophical question is meaningful or not, Gramsci's views run contrary to the metaphysical materialism and copy theory of perception advanced by Friedrich Engels,[58][59] and Lenin,[60] although he does not explicitly state this. For Gramsci, Marxism does not deal with a reality that exists in and for itself, independent of humanity.[61] The concept of an objective universe outside of human history and human praxis was analogous to belief in God.[62] Gramsci defined objectivity in terms of a universal intersubjectivity to be established in a future communist society.[62] Natural history was thus only meaningful in relation to human history. In his view philosophical materialism resulted from a lack of critical thought,[63] and could not be said to oppose religious dogma and superstition.[64] Despite this, Gramsci resigned himself to the existence of this arguably cruder form of Marxism. Marxism was a philosophy for the proletariat, a subaltern class, and thus could often only be expressed in the form of popular superstition and common sense.[65] Nonetheless, it was necessary to effectively challenge the ideologies of the educated classes and to do so Marxists must present their philosophy in a more sophisticated guise and attempt to genuinely understand their opponents' views. |

唯物論の批判 人間史と集団的実践が哲学的問題の意味の有無を決定すると考えるグラムシの見解は、フリードリヒ・エンゲルス[58][59] やレーニン[60] が提唱した形而上学的な唯物論や知覚の複製説とは相反するものですが、彼はそれを明示的には述べていません。グラムシにとって、マルクス主義は人間から独 立して存在し、人間のために存在する現実を扱わない[61]。人間史と人間実践の外にある客観的宇宙の概念は、神への信仰に類似していた[62]。グラム シは、客観性を、未来の共産主義社会で確立される普遍的な相互主観性として定義した[62]。自然史は thus 人間史との関係においてのみ意味を持つ。彼の見解では、哲学的唯物論は批判的思考の欠如から生じ[63]、宗教的教条や迷信と対立するとはいえない [64]。それでも、グラムシはこのより粗雑な形態のマルクス主義の存在を容認した。マルクス主義は、サバルタン階級であるプロレタリアのための哲学であ り、そのため、多くの場合、大衆の迷信や常識という形でしか表現できなかった[65]。それにもかかわらず、教育を受けた階級のイデオロギーに効果的に挑 戦することは必要であり、そのためには、マルクス主義者は、より洗練された形で哲学を提示し、敵対者の見解を真に理解しようと努めなければならない。 |

| Legacy According to the American socialist magazine Jacobin, Gramsci "is one of the most cited Italian authors—certainly the most cited Italian Marxist ever—and one of the most celebrated Marxist philosophers of the twentieth century.", adding that the Prison Notebooks "allowed his unorthodox Marxism to spread worldwide."[66] Gramsci's thought emanates from the organised political left but has also become an important figure in current academic discussions within cultural studies and critical theory. Political theorists from the political centre and the political right have also found insight into his concepts; for instance, his idea of hegemony has become widely cited. His influence is particularly strong in contemporary political science, such as neo-Gramscianism. His critics charge him with fostering a notion of power struggle through ideas. They find the Gramscian approach to philosophical analysis, reflected in current academic controversies, to conflict with open-ended, liberal inquiry grounded in apolitical readings of the classics of Western culture. Some critics have argued that Gramsci's attempt to reconcile Marxism with intellectualism creates an ideological elitism that can be seen as at odds with individual liberty.[67][68] His theory of hegemony has drawn criticism from those who believe that the promotion of state intervention in cultural affairs risks undermining the free exchange of ideas, which is essential for a truly open society.[68][69] As a socialist, Gramsci's legacy has been met with a mixed reception.[47]: 6–7 Togliatti, who led the party (renamed in 1943 as the Italian Communist Party, PCI) after World War II and whose gradualist approach was a forerunner to Eurocommunism, stated that the PCI's practices during this period were congruent with Gramscian thought.[70][71] It is speculated that he would likely have been expelled from his party if his true views had been known, particularly his growing hostility towards Joseph Stalin.[42] One issue for Gramsci related to his speaking on topics of violence and when it might be justified or not. When the socialist Giacomo Matteotti was murdered, Gramsci did not condemn the murder. Matteotti had already called for the rule of law and had been murdered by the fascists for that stance. The murder produced a crisis for the Italian fascist regime that Gramsci could have exploited.[72] The historian Jean-Yves Frétigné argues that Gramsci and the socialists more generally were naïve in their assessment of the fascists and as a result underestimated the brutality of which the regime was capable.[73] In Thailand, Piyabutr Saengkanokkul, an academic, democratic activist, and former Secretary-General of Future Forward Party, cited Gramsci's idea as the main key to establishing a party.[74] |

遺産 アメリカの社会主義雑誌『ジャコバン』によると、グラムシは「最も引用されるイタリア人作家の一人であり、間違いなく最も引用されるイタリア人マルクス主 義者であり、20世紀で最も称賛されたマルクス主義哲学者の一人」であり、その『監獄ノート』は「彼の非正統的なマルクス主義を世界中に広めるきっかけと なった」と付け加えている[66]。 グラムシの思想は、組織化された政治的な左翼から発祥したものですが、文化研究や批判理論における現在の学術的議論においても重要な存在となっています。 政治理論家の中でも、政治的中道派や右派も彼の概念から洞察を得ています。例えば、彼のヘゲモニーの概念は広く引用されています。彼の影響力は、新グラム シ主義などの現代政治学において特に強いです。彼の批判者は、彼が思想を通じて権力闘争の概念を助長したと非難している。彼らは、現在の学術的論争に反映 されているグラムシの哲学的分析のアプローチが、西洋文化の古典の非政治的な解釈に根ざした開かれた自由な探究と矛盾すると指摘している。一部の批判者 は、グラムシがマルクス主義と知性主義を調和させようとした試みが、個人主義と対立するイデオロギー的エリート主義を生み出したと主張している。[67] [68] 彼のヘゲモニー理論は、文化問題への国家の介入を促進することは、真に開かれた社会にとって不可欠な思想の自由な交流を損なう危険性があるとする人々から批判を受けています。[68][69] 社会主義者として、グラムシの遺産は混血の受け止め方をされている。[47]: 6–7 第二次世界大戦後に党(1943年にイタリア共産党、PCI に改名)を率いたトリアッティは、その漸進主義的アプローチがユーロコミュニズムの先駆けとなった人物で、この期間の PCI の実践はグラムシの思想と一致していると述べている。[70][71] 彼の真意、特にヨシフ・スターリンに対する敵意の高まりが知られていたら、彼は党から追放されていた可能性が高いと推測されています。[42] グラムシに関する問題の一つは、暴力について、そしてそれが正当化される場合とされない場合について彼が述べた発言でした。社会主義者のジャコモ・マッテ オッティが殺害されたとき、グラムシはその殺害を非難しませんでした。マッテオッティは既に法の支配を主張しており、その立場からファシストによって暗殺 された。この暗殺はイタリアのファシスト政権に危機をもたらし、グラムシが利用できた可能性があった。[72] 歴史家のジャン=イヴ・フレティニェは、グラムシと社会主義者たちはファシストの評価においてナイーブであり、その結果、政権が可能な残虐性を過小評価し たと主張している。[73] タイでは、学者、民主活動家、元未来前進党書記長のピヤブット・センカノッククルが、グラムシの考えを政党設立の主な鍵として引用している。[74] |

| Personal life Association football Like fellow Turinese and communist Palmiro Togliatti, Gramsci took an interest in association football, which was becoming a sport with massive following and was elected by the fascist regime in Italy as a national sport, and was said to have been a supporter of Juventus, as were other notable communist and left-wing leaders.[75][76][77] On 16 December 1988, the PCI's newspaper l'Unità published an article on the front page titled "Gramsci Was Rooting for Juve". Signed by Giorgio Fabre, it contained some letters in which Gramsci asked Piero Sraffa for "news from our Juventus". Even though those letters later turned out to be false, the article remains part of the Gramscian bibliography and triggered numerous reactions, including from Giampiero Boniperti, who on behalf of the club the following day told at La Stampa: "We are pleased to know that among our fans there have been personalities who have marked an era from the political, economic, and intellectual point of view. This shows that Juventus truly have something special, a charm that has never lost strength over the years." Gramsci's interest in football dates back to a 16 August 1918 article for the PSI's newspaper Avanti!, titled "Football and Scopone". Fifteen years later, he pointed at the degeneration of stadium cheering, which emerged with the advent of fascism and the consequent nationalisation of the sport that he said extinguished political and trade union commitment.[78] |

私生活 サッカー トリノ出身で共産主義者のパルミロ・トリアッティと同様、グラムシは、大衆的な人気を博し、イタリアのファシスト政権によって国技に指定されたサッカーに 興味を持ち、他の著名な共産主義者や左翼指導者たちと同様、ユベントスのファンだったと言われている[75][76]。[77] 1988年12月16日、イタリア共産党の機関紙『ル・ウンità』は、1面トップに「グラムシはユベントスを応援していた」というタイトルの記事を掲載 した。ジョルジオ・ファブレが署名したこの記事には、グラムシがピエロ・スラッファに「私たちのユベントスの近況を教えてくれ」と書いた手紙が掲載されて いた。これらの手紙は後に偽物であることが判明したが、この記事はグラムシの書誌の一部として残っており、ジャンピエロ・ボニペルティをはじめとする多く の人々から反応が寄せられた。ボニペルティは翌日、クラブを代表してラ・スタンパ紙に「私たちのファンの中に、政治、経済、知的な観点から時代を象徴する 人物たちがいたことを嬉しく思う。これは、ユベントスが真に特別なもの、年月を経ても衰えない魅力を備えていることを示している。」グラムシのサッカーへ の関心は、1918年8月16日にPSIの新聞『アヴァンティ!』に掲載された「サッカーとスコポーネ」という記事に遡る。15年後、彼はファシズムの台 頭とそれに伴うスポーツの国有化により、スタジアムの応援が退廃化し、政治的・労働組合的なコミットメントが消滅したと指摘した。[78] |

| Bibliography Collections Pre-Prison Writings (Cambridge University Press) The Prison Notebooks (three volumes) (Columbia University Press) Selections from the Prison Notebooks (International Publishers) Essays Newspapers and the Workers (1916) Men or machines? (1916) One Year of History (1918) |

参考文献 著作集 刑務所入所前の著作(ケンブリッジ大学出版局) 刑務所ノート(3巻)(コロンビア大学出版局) 刑務所ノートからの抜粋(インターナショナル・パブリッシャーズ) エッセイ 新聞と労働者(1916年) 人間か機械か?(1916年) 1年の歴史(1918年) |

| Articulation (sociology) Liberation theology Praxis School Subaltern (postcolonialism) Subaltern Studies Unification of Italy |

分節化=節合化(社会学) 解放の神学 プラクシス学派 サバルタン(ポストコロニアリズム サバルタン研究 イタリア統一 |

| Cited sources Althusser, Louis (1971), Lenin and Philosophy, London: Monthly Review Press, ISBN 978-1583670392, archived from the original on 18 June 2020, retrieved 16 June 2020. Anderson, Perry (November–December 1976). "The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci". New Left Review. I (100). New Left Review: 5–78. Ebner, Michael (2011). Ordinary Violence in Mussolini's Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 76, 105, 144, 150. Frétigné, Jean-Yves (2021). To Live is To Resist: The Life of Antonio Gramsci. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 156–159, 182–183. Gramsci, Antonio (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0397-X. Gramsci, Antonio (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7178-0397-2. Haralambos, Michael; Holborn, Martin (2013), Sociology Themes and Perspectives (8th ed.), New York: HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-00-749882-6 Hoare, Quintin; Smith, Geoffrey Nowell (1971), Introduction, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, by Gramsci, Antonio, Hoare, Quentin; Smith, Geoffrey Nowell (eds.), New York: International Publishers, pp. xvii–xcvi, ISBN 0-7178-0397-X Jones, Steven (2006), Antonio Gramsci, Routledge Critical Thinkers, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-31947-1. Kiernan, V. G. (1991). "Intellectuals". In Bottomore, Tom; Harris, Laurence; Kiernan, V.G; Miliband, Ralph (eds.). The Dictionary of Marxist Thought (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishers Ltd. p. 259. ISBN 0-631-16481-2. Kołakowski, Leszek (2005). Main Currents of Marxism. London: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32943-8. Santangelo, Federico (2021). "Between Ceasarism and Cosmopolitanism: Julius Ceasar as an Historical Problem in Gramsci". In Zucchetti, Emilio; Cimino, Anna Maria (eds.). Antonio Gramsci and the Ancient World. Taylor & Francis. pp. 201–221. ISBN 978-0429510359. Sassoon, Anne Showstack (1991a). "Antonio Gramsci". In Bottomore, Tom; Harris, Laurence; Kiernan, V.G; Miliband, Ralph (eds.). The Dictionary of Marxist Thought (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishers Ltd. pp. 221–223. ISBN 0-631-16481-2. Sassoon, Anne Showstack (1991b). "Civil Society". In Bottomore, Tom; Harris, Laurence; Kiernan, V.G; Miliband, Ralph (eds.). The Dictionary of Marxist Thought (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishers Ltd. pp. 83–85. ISBN 0-631-16481-2. Sassoon, Anne Showstack (1991c). "Hegemony". In Bottomore, Tom; Harris, Laurence; Kiernan, V.G.; Miliband, Ralph (eds.). The Dictionary of Marxist Thought (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishers Ltd. pp. 229–231. ISBN 0-631-16481-2. Sassoon, Anne Showstack (1991d), "Prison Notebooks", in Bottomore, Tom; Harris, Laurence; Kiernan, V.G.; Miliband, Ralph (eds.), The Dictionary of Marxist Thought (2nd ed.), Blackwell Publishers Ltd., pp. 446–447, ISBN 0-631-16481-2 |

引用元 アルチュセール、ルイ(1971)、『レーニンと哲学』、ロンドン:Monthly Review Press、ISBN 978-1583670392、2020年6月18日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2020年6月16日に取得。 アンダーソン、ペリー(1976年11月~12月)。「アントニオ・グラムシのアンチノミー」。ニュー・レフト・レビュー。I (100)。ニュー・レフト・レビュー:5–78。 エブナー、マイケル (2011)。ムッソリーニのイタリアにおける通常の暴力。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。76、105、144、150 ページ。 フレティグネ、ジャン=イヴ (2021)。生きることは抵抗すること:アントニオ・グラムシの生涯。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。156-159、182-183 ページ。 グラムシ、アントニオ (1971)。刑務所ノートから選集。インターナショナル・パブリッシャーズ。ISBN 0-7178-0397-X。 グラムシ、アントニオ (1971)。『刑務所ノートから選集』 International Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7178-0397-2. Haralambos, Michael; Holborn, Martin (2013), Sociology Themes and Perspectives (8th ed.), New York: HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-00-749882-6 Hoare, Quintin; Smith, Geoffrey Nowell (1971), Introduction, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, by Gramsci, Antonio, Hoare, Quentin; Smith, Geoffrey Nowell (eds.), New York: International Publishers, pp. xvii–xcvi, ISBN 0-7178-0397-X ジョーンズ、スティーブン (2006)、『アントニオ・グラムシ』、Routledge Critical Thinkers、Routledge、ISBN 0-415-31947-1。 キアナン、V. G. (1991)。「知識人」。ボトムモア、トム、ハリス、ローレンス、キアナン、V.G、ミリバンド、ラルフ (編)。The Dictionary of Marxist Thought (第 2 版)。ブラックウェル出版社。259 ページ。ISBN 0-631-16481-2。 コラコフスキ、レシェック (2005)。Main Currents of Marxism。ロンドン:W. W. ノートン&カンパニー。ISBN 978-0-393-32943-8。 サンタンジェロ、フェデリコ (2021)。「シーザー主義とコスモポリタニズムの間:グラムシにおける歴史的問題としてのジュリアス・シーザー」。ズッケッティ、エミリオ、チミノ、 アンナ・マリア (編)。アントニオ・グラムシと古代世界。テイラー&フランシス。201-221 ページ。ISBN 978-0429510359。 サッソン、アン・ショースタック (1991a). 「アントニオ・グラムシ」 『ボトムモア、トム、ハリス、ローレンス、キアナン、V.G、ミリバンド、ラルフ (編)』 『マルクス主義思想辞典』 (第 2 版) ブラックウェル出版社 pp. 221–223. ISBN 0-631-16481-2. サッソン、アン・ショースタック (1991b). 「市民社会」 『ボトムモア、トム、ハリス、ローレンス、キアナン、V.G、ミリバンド、ラルフ (編)』 『マルクス主義思想辞典』 (第 2 版) ブラックウェル出版社 pp. 83–85. ISBN 0-631-16481-2. サッソン、アン・ショスタック (1991c)。「ヘゲモニー」。ボトムア、トム、ハリス、ローレンス、キアナン、V.G.、ミリバンド、ラルフ (編)。『マルクス主義思想辞典』 (第 2 版)。ブラックウェル出版社。229-231 ページ。ISBN 0-631-16481-2。 Sassoon, Anne Showstack (1991d), 「Prison Notebooks」, Bottomore, Tom; Harris, Laurence; Kiernan, V.G.; ミリバンド、ラルフ(編)、『マルクス主義思想辞典』(第 2 版)、ブラックウェル出版社、446-447 ページ、ISBN 0-631-16481-2 |

| Further reading Adamson, Walter L. (2014). Hegemony and Revolution: Antonio Gramsci's Political and Cultural Theory. Brattleboro, VT: Echo Point Books & Media. ISBN 9781626549098. Anderson, Perry (November–December 1976). "The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci". New Left Review. I (100). New Left Review: 5–78. Aqueci, Francesco (September–December 2018). "Il Gramsci di un nuovo inizio" (PDF). Rivista Internazionale di Studi Culturali, Linguistici e Letterari (in Italian) (Quaderno 12, Supplemento al n. 19): 223. Boggs, Carl (1984). The Two Revolutions: Gramsci and the Dilemmas of Western Marxism. London: South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-226-7. Bottomore, Tom (1992). The Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-631-18082-1. Dainotto, Roberto M.; Jameson, Fredric, eds. (28 August 2020). Gramsci in the World. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-4780-0849-1. Davidson, Alastair (2018). Antonio Gramsci: Towards an Intellectual Biography. Haymarket Books. ISBN 9781608468256. Femia, Joseph V. (1981). Gramsci's Political Thought: Hegemony, Consciousness, and the Revolutionary Process. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-827251-0. Fonseca, Marco (2016). Gramsci's Critique of Civil Society. Towards a New Concept of Hegemony. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13-848649-2. Greaves, Nigel (2009). Gramsci's Marxism: Reclaiming a Philosophy of History and Politics. Troubador Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84876-127-8. Harman, Chris (9 April 2007). "Gramsci, the Prison Notebooks and Philosophy". International Socialism. Henderson, Hamish (Winter 1987–1988). Ross, Raymond J. (ed.). "Antonio Gramsci". Cencrastus. 28: 22–26. ISSN 0264-0856. Jay, Martin (1986). Marxism and Totality: The Adventures of a Concept from Lukacs to Habermas. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05742-5. Joll, James (1977). Antonio Gramsci. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-12942-3. Kolakowski, Leszek (1981). Main Currents of Marxism, Vol. III: The Breakdown. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285109-3. Hall, Stuart (June 1986). "Gramsci's relevance for the study of race and ethnicity". Journal of Communication Inquiry. 10 (2): 5–27. doi:10.1177/019685998601000202. S2CID 53782. Maitan, Livio (1978). Il marxismo rivoluzionario di Antonio Gramsci. Milano: Nuove edizioni internazionali. McNally, Mark (11 August 2015). Antonio Gramsci. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-33418-3. Onnis, Omar; Mureddu, Manuelle (2019). Illustres. Vita, morte e miracoli di quaranta personalità sarde (in Italian). Sestu: Domus de Janas. ISBN 978-88-97084-90-7. OCLC 1124656644. Pastore, Gerardo (2011). Antonio Gramsci: Questione sociale e questione sociologica. Gerardo Pastore. ISBN 978-88-7467-059-8. Santucci, Antonio A. (2010). Antonio Gramsci. Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-210-5. Thomas, Peter D. (2009). The Gramscian Moment: Philosophy, Hegemony and Marxism. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-16771-1. Cammett, John M. (1967). Antonio Gramsci and the Origins of Italian Communism. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804701426. |

さらに読む アダムソン、ウォルター L. (2014). ヘゲモニーと革命:アントニオ・グラムシの政治文化論. バーモント州ブラトルボロ:エコーポイントブックス&メディア. ISBN 9781626549098. アンダーソン、ペリー (1976年11月~12月). 「アントニオ・グラムシの矛盾」. ニュー・レフト・レビュー。I (100)。ニュー・レフト・レビュー:5–78。 Aqueci, Francesco (2018年9月–12月). 「Il Gramsci di un nuovo inizio」 (PDF). Rivista Internazionale di Studi Culturali, Linguistici e Letterari (イタリア語) (Quaderno 12, Supplemento al n. 19): 223. ボッグス、カール(1984)。『二つの革命:グラムシと西洋マルクス主義のジレンマ』。ロンドン:サウス・エンド・プレス。ISBN 978-0-89608-226-7。 ボトムア、トム(1992)。『マルクス主義思想辞典』。ブラックウェル・パブリッシャーズ。ISBN 978-0-631-18082-1。 ダイノット、ロベルト M.、ジェイムソン、フレデリック、編(2020年8月28日)。『グラムシの世界』デューク大学出版。ISBN 978-1-4780-0849-1。 デビッドソン、アラステア(2018)。アントニオ・グラムシ:知的な伝記に向けて。ヘイマーケット・ブックス。ISBN 9781608468256。 フェミア、ジョセフ V. (1981)。グラムシの政治思想:ヘゲモニー、意識、そして革命過程。クラレンドン・プレス。ISBN 0-19-827251-0。 フォンセカ、マルコ (2016)。『グラムシの市民社会批判。新しいヘゲモニーの概念に向けて』。Routledge。ISBN 978-1-13-848649-2。 Greaves, Nigel (2009). Gramsci's Marxism: Reclaiming a Philosophy of History and Politics. Troubador Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84876-127-8。 ハーマン、クリス (2007年4月9日)。「グラムシ、刑務所ノート、そして哲学」。国際社会主義。 ヘンダーソン、ハミッシュ (1987年冬~1988年)。ロス、レイモンド J. (編)。「アントニオ・グラムシ」。Cencrastus。28: 22–26。ISSN 0264-0856。 ジェイ、マーティン (1986)。マルクス主義と全体性:ルカーチからハーバーマスまでの概念の冒険。カリフォルニア大学出版。ISBN 978-0-520-05742-5。 ジョール、ジェームズ (1977)。アントニオ・グラムシ。ニューヨーク:バイキング・プレス。ISBN 978-0-670-12942-3。 コラコフスキー、レシェク (1981)。マルクス主義の主な潮流、第 III 巻:崩壊。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-285109-3。 ホール、スチュワート (1986年6月)。「人種と民族の研究におけるグラムシの関連性」。ジャーナル・オブ・コミュニケーション・インクワイアリー。10 (2): 5–27. doi:10.1177/019685998601000202. S2CID 53782. マイタン、リヴィオ (1978)。Il marxismo rivoluzionario di Antonio Gramsci. ミラノ: Nuove edizioni internazionali. マクナリー、マーク (2015年8月11日)。Antonio Gramsci. スプリンガー。ISBN 978-1-137-33418-3。 オニス、オマル;ムレドゥ、マヌエル(2019)。『著名人。40人のサルデーニャの著名人の生涯、死、そして奇跡』(イタリア語)。セスト:ドムス・デ・ジャナス。ISBN 978-88-97084-90-7。OCLC 1124656644。 パストーレ、ジェラルド(2011)。『アントニオ・グラムシ:社会問題と社会学的問題』。ジェラルド・パストーレ。ISBN 978-88-7467-059-8。 サンチュッチ、アントニオ・A.(2010)。『アントニオ・グラムシ』。Monthly Review Press。ISBN 978-1-58367-210-5。 トーマス、ピーター D. (2009)。グラムシの瞬間:哲学、ヘゲモニー、マルクス主義。ブリル。ISBN 978-90-04-16771-1。 キャメット、ジョン M. (1967)。アントニオ・グラムシとイタリア共産主義の起源。スタンフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0804701426。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_Gramsci |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆