我が友、シーシュポスへの頌歌

Anthem for my fellow Sisyphus!

我が友、シーシュポスへの頌歌

Anthem for my fellow Sisyphus!

我が同胞、シジフォス(シー シュポス)への頌歌

(α)クソッタレ!と岩をせっせと押し上 げるシジフォスに美学を感じる人と、

(β)とぼとぼと麓(ふもと)まで歩いて 降りる間に思索できる愉しみを得たシジフォスに深い共感を抱く人と、

(γ)麓にたどりついた時やれやれという この虚無感がいいという人もいる。

そして、シジフォスの生き様を「恐怖」と 感じる人以外の、これらの3つの彼の生き様の諸相に興味をもつ人たちは、その共通事項として、すべてシジフォスが愛すべき存在として知っているはずなの だ。

★テ クスト(カミユのエッセー)

| Le mythe de Sisyphe. Essai sur l’absurde. (1942) | シジフォスの神話 不条理についてのエッセイ(1942年) |

| Les dieux avaient condamné Sisyphe à rouler sans cesse un rocher jusqu'au sommet d'une montagne d'où la pierre retombait par son pro-pre poids. Ils avaient pensé avec quelque raison qu'il n'est pas de puni-tion plus terrible que le travail inutile et sans espoir. | 神々はシジフォスに、山の頂上まで延々と玉石を転がし続け、そこから自 重で石が落ちるように宣告した。神々は、無意味で絶望的な仕事ほど恐ろしい罰はない と考えたのだ。 |

| Si l'on en croit Homère, Sisyphe était le plus sage et le plus pru-dent des mortels. Selon une autre tradition cependant, il inclinait au métier de brigand. Je n'y vois pas de contradiction. Les opinions dif-fèrent sur les motifs qui lui valurent d'être le travailleur inutile des enfers. On lui reproche d'abord quelque légèreté avec les dieux. Il livra leurs secrets. Egine, fille d'Asope, fut enlevée par Jupiter. Le père s'étonna de cette disparition et s'en plaignit à Sisyphe. Lui, qui avait connaissance de l'enlèvement, offrit à Asope de l'en instruire, à la condition qu'il donnerait de l'eau à la citadelle de Corinthe. Aux foudres célestes, il préféra la bénédiction de [164] l'eau. Il en fut pu-ni dans les enfers. Homère nous raconte aussi que Sisyphe avait en-chainé la Mort. Pluton ne put supporter le spectacle de son empire dé-sert et silencieux. Il dépêcha le dieu de la guerre qui délivra la Mort des mains de son vainqueur. | ホメロスによれば、シジフォスは人間の中で最も賢く、思慮深かった。し かし、別の伝承によれば、彼は強盗になる傾向があった。私はここに矛盾はないと思 う。なぜ彼が冥界の役立たずとなったかについては、意見が分かれるところである。まず第一に、彼は神々に対して軽率な振る舞いをしたと非難された。彼は神 々の秘密を漏らした。イソップの娘エギナはユピテルに誘拐された。父親は彼女の失踪に驚き、シジフォスに訴えた。誘拐のことを知っていたシジフォスは、コ リントの城塞に水を与えることを条件に、イソップにそのことを話すと申し出た。シジフォスは天の雷の代わりに、水の祝福 [164] を好んだ。彼は冥界で気絶させられた。ホメロスはまた、シジフォスが死を鎖でつないだとも語っている。冥王星は、荒れ果て沈黙した自分の帝国を見るに忍び なかった。彼は戦いの神を派遣し、征服者の手から死を救い出した。 |

| On dit encore que Sisyphe étant près de mourir voulut imprudem-ment éprouver l'amour de sa femme. Il lui ordonna de jeter son corps sans sépulture au milieu de la place publique. Sisyphe se retrouva dans les enfers. Et là, irrité d'une obéissance si contraire à l'amour humain, il obtint de Pluton la permission de retourner sur la terre pour châtier sa femme. Mais quand il eut de nouveau revu le visage de ce monde, goûté l'eau et le soleil, les pierres chaudes et la mer, il ne voulut plus retourner dans l'ombre infernale. Les rappels, les colères et les aver-tissements n'y firent rien. Bien des années encore, il vécut devant la courbe du golfe, la mer éclatante et les sourires de la terre. Il fallut un arrêt des dieux. Mercure vint saisir l'audacieux au collet et l'ôtant à ses joies, le ramena de force aux enfers où son rocher était tout prêt. | また、シジフォスが死を目前にしたとき、無謀にも妻の愛を試そうとした とも言われている。そして、埋葬されていない自分の死体を広場の真ん中に投げ捨てる よう妻に命じた。シジフォスは気がつくと冥界にいた。そしてそこで、人間の愛にあまりにも反する服従に怒り、妻を罰するために地上に戻る許可を冥王星から 得た。しかし、いったんこの世の顔を再び見て、水と太陽、暖かい石と海を味わうと、彼はもはや地獄の影に戻ろうとはしなかった。督促や癇癪や警告は何の役 にも立たなかった。それから何年もの間、彼は湾のカーブ、明るい海、土地の笑顔とともに暮らした。神々は彼を止めなければならなかった。マーキュリーが やってきて、この大胆な男の襟首をつかみ、喜びから遠ざけ、岩が用意されている冥界に強制的に連れ戻した。 |

| On a compris déjà que Sisyphe est le héros absurde. Il l'est autant par ses passions que par son tourment. Son mépris des dieux, sa haine de la mort et sa passion pour la vie, lui ont valu ce supplice indicible où tout l'être s'emploie à ne rien achever. C'est le prix qu'il faut payer pour les passions de cette terre. On ne nous dit [165] rien sur Sisyphe aux enfers. Les mythes sont faits pour que l'imagination les anime. Pour celui-ci on voit seulement tout l'effort d'un corps tendu pour soulever l'énorme pierre, la rouler et l'aider à gravir une pente cent fois recommencée ; on voit le visage crispé, la joue collée contre la pierre, le secours d'une épaule qui reçoit la masse couverte de glaise, d'un pied qui la cale, la reprise à bout de bras, la sûreté tout humaine de deux mains pleines de terre. Tout au bout de ce long effort mesuré par l'espace sans ciel et le temps sans profondeur, le but est atteint. Sisyphe regarde alors la pierre dévaler en quelques instants vers ce monde inférieur d'où il faudra la remonter vers les sommets. Il redes-cend dans la plaine. | シジフォスが不条理な英雄であることはすでに理解した。彼は苦悩と同様 に情熱においても不条理である。神々を軽蔑し、死を憎み、生に情熱を燃やしたがゆえ に、言いようのない苦悩を味わうことになった。これが、この世の情熱の代償なのだ。冥界のシジフォスについては何も語られていない。神話は想像力を喚起す るために作られる。緊張した顔、石に押しつけられた頬、粘土で覆われた塊を受け止める肩の力、石にくさびを打ち込む足の力、腕の長さでの再開、両手いっぱ いの土の人間的な安心感。空のない空間と深さのない時間で測られるこの長い努力の果てに、ゴールに到達する。そしてシジフォスは、石が下界のほうへあっと いう間に転がり落ちるのを見届ける。彼は平原に戻る。 |

| C'est pendant ce retour, cette pause, que Sisyphe m'intéresse. Un visage qui peine si près des pierres est déjà pierre lui-même ! Je vois cet homme redescendre d'un pas lourd mais égal vers le tourment dont il ne connaîtra pas la fin. Cette heure qui est comme une respiration et qui revient aussi sûrement que son malheur, cette heure est celle de la conscience. À chacun de ces instants, où il quitte les sommets et s'en-fonce peu à peu vers les tanières des dieux, il est supérieur à son des-tin. Il est plus fort que son rocher. | シジフォスが私に興味を抱かせるのは、この帰還の間、この休止の間であ る。石のすぐそばでもがく顔は、すでに石そのものだ!私には、この男が決して終わる ことのない苦悩へと下っていくのが見える。呼吸のように、不幸と同じように確実に戻ってくるこの時間、この時間こそが良心の時間なのだ。山頂を離れ、神々 の隠れ家に向かって徐々に沈んでいくこの瞬間、彼はそのデスチンよりも優れている。彼は岩よりも強い。 |

| Si ce mythe est tragique, c'est que son héros est conscient. Où se-rait en effet sa peine, si à chaque pas l'espoir de réussir le soutenait ? [166] L'ouvrier d'aujourd'hui travaille, tous les jours de sa vie, aux mêmes tâches et ce destin n'est pas moins absurde. Mais il n'est tra-gique qu'aux rares moments où il devient conscient. Sisyphe, prolétai-re des dieux, impuissant et révolté, connaît toute l'étendue de sa mi-sérable condition : c'est à elle qu'il pense pendant sa descente. La clairvoyance qui devait faire son tourment consomme du même coup sa victoire. Il n'est pas de destin qui ne se surmonte par le mépris. | この神話が悲劇的であるとすれば、それは主人公に意識があるからであ る。成功への希望が彼を一歩一歩支えていたとしたら、彼の苦しみに何の意味があろう か。[166] 現代の労働者は毎日同じ仕事に従事しており、その運命もまた不条理である。しかし、それが悲劇的であるのは、それが意識化されるまれな瞬間だけである。神 々のプロレタリアであり、無力で反抗的なシジフォスは、自分の半 惨めな境遇の全容を知っている。彼の苦悩となるはずだった千里眼は、彼の勝利を完成させる。軽蔑に打ち勝たない運命などない。 |

| Si la descente ainsi se fait certains jours dans la douleur, elle peut se faire aussi dans la joie. Ce mot n'est pas de trop. J'imagine encore Sisyphe revenant vers son rocher, et la douleur était au début. Quand les images de la terre tiennent trop fort au souvenir, quand l'appel du bonheur se fait trop pressant, il arrive que la tristesse se lève au coeur de l'homme : c'est la victoire du rocher, c'est le rocher lui-même. L'immense détresse est trop lourde à porter. Ce sont nos nuits de Gethsémani. Mais les vérités écrasantes périssent d'être re-connues. Ainsi, Oedipe obéit d'abord au destin sans le savoir. A partir du moment où il sait, sa tragédie commence. Mais dans le même ins-tant, aveugle et désespéré, il reconnaît que le seul lien qui le rattache au monde, c'est la main fraîche d'une jeune fille. Une parole démesu-rée retentit alors : « Malgré [167] tant d'épreuves, mon âge avancé et la grandeur de mon âme me font juger que tout est bien. » L'Oedipe de Sophocle, comme le Kirilov de Dostoïevsky, donne ainsi la formule de la victoire absurde. La sagesse antique rejoint l'héroïsme moderne. | 下降が時に苦痛であるなら、それは喜びでもある。この言葉は強すぎな い。私はシジフォスが岩に戻る姿を今でも想像することができる。大地のイメージがあま りにも強く記憶に残るとき、幸福の呼び声があまりにも強くなるとき、人の心には時に悲しみが湧き上がる。それは岩の勝利であり、岩そのものなのだ。これが 私たちのゲッセマネの夜である。しかし、砕け散るような真実は、再認識されたときに消え去る。だからオイディプスはまず、それを知らずに運命に従う。それ を知った瞬間から、彼の悲劇は始まる。しかし同時に、盲目で絶望的なオイディプスは、自分と世界を結びつけているのは少女のみずみずしい手だけだと気づ く。そして彼は、「[167]これほど多くの苦難にもかかわらず、私の高齢と魂の偉大さが、すべてがうまくいっていると信じさせてくれる」と、とんでもな いことを言うのである。ソフォクレスの『オイディプス』は、ドストエフスキーの『キリロフ』のように、こうして不条理な勝利の方程式を示す。古代の知恵と 現代のヒロイズムの出会い。 |

| On ne découvre pas l'absurde sans être tenté, d'écrire quelque ma-nuel du bonheur.. « Eh ! quoi, par des voies si étroites... ? » Mais il n'y a qu'un monde. Le bonheur et l'absurde sont deux fils de la même ter-re. Ils sont inséparables. L'erreur serait de dire que le bonheur naît forcément de la découverte absurde. Il arrive aussi bien que le senti-ment de l'absurde naisse du bonheur. « Je juge que tout est bien », dit Oedipe, et cette parole est sacrée. Elle retentit dans l'univers fa-rouche et limité de l'homme. Elle enseigne que tout n'est pas, n'a pas été épuisé. Elle chasse de ce monde un dieu qui y était entré avec l'in-satisfaction et le goût des douleurs inutiles. Elle fait du destin une affaire d'homme, qui doit être réglée entre les hommes. | 不条理を発見するには、幸福のマニュアルを書きたくなるものだ。「こん な狭い道を通って?しかし、世界はひとつしかない。幸福と不条理は同じ糸で結ばれて いる。切り離すことはできない。幸福は不条理を発見することによって必然的に生まれるというのは間違いだ。幸福は不条理を感じることによっても生まれる。 「オイディプスは言う。この言葉は人間の限られた空虚な宇宙に響く。この言葉は、人間の限られた空虚な宇宙に響き渡る。満足せず、無意味な苦痛を味わいな がらこの世に入り込んだ神をこの世から追い出す。運命は人間同士の問題であり、人間同士で決着をつけるべきものなのだ。 |

| Toute la

joie silencieuse de Sisyphe est là. Son destin lui

appar-tient. Son rocher est sa chose. De même, l'homme absurde, quand

il contemple son tourment, fait taire toutes les idoles. Dans l'univers

soudain rendu à son silence, les mille petites voix émerveillées de la

terre s'élèvent. Appels inconscients et secrets, invitations de tous

les visages, ils sont l'envers nécessaire et le prix de la victoire. Il

n'y a pas de soleil sans ombre, [168] et il faut connaître la nuit.

L'homme absurde dit oui et son effort n'aura plus de cesse. S'il y a un

destin personnel, il n'y a point de destinée supérieure ou du moins il

n'en est qu'une dont il juge qu'elle est fatale et méprisable. Pour le

reste, il se sait le maître de ses jours. À cet instant subtil où

l'homme se retour-ne sur sa vie, Sisyphe, revenant vers son rocher,

contemple cette suite d'actions sans lien qui devient son destin, créé

par lui, uni sous le re-gard de sa mémoire, et bientôt scellé par sa

mort. Ainsi, persuadé de l'origine tout humaine de tout ce qui est

humain, aveugle qui désire voir et qui sait que la nuit n'a pas de fin,

il est toujours en marche. Le rocher roule encore. |

これがシジフォスの静かな喜びである。彼の運命は彼のものである。彼の 岩は彼のものなのだ。同じように、不条理な人間は、自分の苦悩を考えるとき、すべて の偶像を沈黙させる。突如として静まり返った宇宙では、大地からの千の小さな驚嘆の声が立ち上がる。無意識のうちに密かに呼びかける声、あらゆる顔からの 誘い、それらは必要な裏返しであり、勝利の代償である。影のない太陽はなく [168] 、夜を知らなければならない。不条理な人間はイエスと言い、その努力は決して止むことはない。個人的な運命があるとすれば、それ以上の運命は存在しない か、少なくとも彼が致命的で卑劣だと考えるものしか存在しない。それ以外は、自分が自分の日々の主人であることを知っている。人間が自分の人生を振り返る その微妙な瞬間に、岩に戻ったシジフォスは、自分の運命となる一連のつながりのない行為を熟考する。こうして、人間的なものの起源はすべて人間的なもので あることを確信した盲人は、見ることを望み、夜に終わりがないことを知りながら、なおも行進を続ける。岩は転がり続けている。 |

| Je laisse Sisyphe au bas de, la montagne ! On retrouve toujours son fardeau. Mais Sisyphe enseigne la fidélité supérieure qui nie les dieux et soulève les rochers. Lui aussi juge que tout est bien. Cet univers désormais sans maître ne lui paraît ni stérile ni futile. Chacun des grains de cette pierre, chaque éclat minéral de cette montagne pleine de nuit, à lui seul, forme un monde. La lutte elle-même vers les som-mets suffit à remplir un coeur d'homme. Il faut imaginer Sisyphe heu-reux. | 私はシジフォスを山の麓に置き去りにする!あなたはいつも自分の重荷を 見つける。しかし、シジフォスは神々を否定し、岩を持ち上げるより高い忠誠を教え る。彼もまた、すべてはうまくいくと信じている。今や主を失ったこの宇宙は、彼にとって不毛でも無益でもない。この石の一粒一粒が、この夜に満ちた山の鉱 物の一片一片が、それだけで世界を形成している。頂上を目指す闘いそのものが、人の心を満たすのに十分なのだ。シジフォスの幸せを想像しなければならな い。 |

★シーシュポス(Sisyphus or Sisyphos)

| In

Greek mythology, Sisyphus or Sisyphos (/ˈsɪsɪfəs/ ⓘ; Ancient Greek:

Σίσυφος, romanized: Sísyphos) is the founder and king of Ephyra (now

known as Corinth). He reveals Zeus's abduction of Aegina to the river

god Asopus, thereby incurring Zeus's wrath. His subsequent cheating of

death earns him eternal punishment in the underworld, once he dies of

old age. The gods forced him to roll an immense boulder up a hill only

for it to roll back down every time it neared the top, repeating this

action for eternity. Through the classical influence on contemporary

culture, tasks that are both laborious and futile are therefore

described as Sisyphean (/sɪsɪˈfiːən/).[2] |

ギリシャ神話において、シーシュポス

(Sisyphus/Sisyphos、/ˈsɪsɪfəs/ ⓘ、古代ギリシャ語: Σίσυφος、ローマ字表記:

Sísyphos)はエフィラ(現在のコリント)の創始者であり王である。彼はゼウスがアイギナを誘拐したことを川の神アソポスに告げ、それによってゼウ

スの怒りを買った。その後、死を免れた彼は老衰で死ぬと、冥界で永遠の罰を受けることになった。神々は彼に巨大な岩を丘の上まで転がすよう命じたが、頂上

に近づくたびに岩は転がり落ちてしまう。この行為を永遠に繰り返すのだ。古典文化が現代文化に与えた影響により、労苦が多く無益な作業は「シーシュポスの

ような」(/sɪsɪˈfiːən/)と表現されるようになった。[2] |

| Etymology R. S. P. Beekes has suggested a pre-Greek origin and a connection with the root of the word sophos (σοφός, "wise").[3] German mythographer Otto Gruppe thought that the name derived from sisys (σίσυς, "a goat's skin"), in reference to a rain-charm in which goats' skins were used.[4] Family Sisyphus was formerly a Thessalian prince as the son of King Aeolus of Aeolia and Enarete, daughter of Deimachus.[5] He was the brother of Athamas, Salmoneus, Cretheus, Perieres, Deioneus, Magnes, Calyce, Canace, Alcyone, Pisidice and Perimede. Sisyphus married the Pleiad Merope by whom he became the father of Ornytion (Porphyrion[6]), Glaucus, Thersander and Almus.[7] He was the grandfather of Bellerophon through Glaucus;[8][9] and of Minyas, founder of Orchomenus, through Almus.[10] Another account related that Minyas was Sisyphus's son instead.[11] In other versions of the myth, Sisyphus was the true father of Odysseus by Anticleia instead of Laërtes.[12] |

語源 R. S. P. ビーケスは、この語がギリシャ以前の起源を持ち、語根「ソフォス(σοφός、賢い)」との関連性を示唆している。[3] ドイツの神話学者オットー・グルッペは、この名が「シシス(σίσυς、山羊の皮)」に由来すると考えた。これは山羊の皮を用いた雨乞いの呪術に由来する ものである。[4] 家族 シーシュポスは、かつてテッサリアの王子であった。父はアイオリアの王アイオロス、母はデイマコスの娘エナレテである。[5] 彼はアタマオス、サルモネオス、クレテオス、ペリエーレス、デイオネオス、マグネス、カリケ、カナケ、アルキオーネ、ピシディケ、ペリメデスの兄弟であっ た。 シシュフォスはプレアデスの一人メロペと結婚し、オルニュティオン(ポルフィリオン[6])、グラウコス、テュルサンデル、アルムスの父となった。[7] 彼はグラウコスを通じてベレロフォン[8][9]の祖父であり、アルムスを通じてオルコメノスの創始者ミニアス[10]の祖父でもあった。別の説では、ミ ニアスはシシュフォスの息子であったとされている[11]。 神話の他の版本では、シシュフォスはラエルテスの代わりにアンティクレアとの間にオデュッセウスの実の父であったとされる[12]。 |

| Reign Sisyphus was the founder and first king of Ephyra (supposedly the original name of Corinth).[8] While king, according to Pausanias, he founded the Isthmian games in honor of Melicertes, whose dead body was brought to shore on the Isthmus of Corinth by a dolphin.[13] In a fragment of Pindar, he instead founds the games (in honour of Melicertes) upon the instructions of a group of nymphs.[14] Conflict with Salmoneus Sisyphus and his brother Salmoneus were known to hate each other, and Sisyphus consulted the Oracle of Delphi on just how to kill Salmoneus without incurring any severe consequences for himself. From Homer onward, Sisyphus was famed as the craftiest of men. He seduced Salmoneus's daughter Tyro in one of his plots to kill Salmoneus, only for Tyro to slay their children when she discovered that Sisyphus was planning on using them to eventually dethrone her father. Cheating death Sisyphus betrayed one of Zeus's secrets by revealing the whereabouts of the Asopid Aegina to her father, the river god Asopus, in return for causing a spring to flow on the Corinthian acropolis.[8] Zeus ordered Thanatos to chain Sisyphus in Tartarus. Sisyphus was curious as to why Charon, whose job it was to guide souls to the underworld, had not appeared on this occasion. Sisyphus slyly asked Thanatos to demonstrate how the chains worked. As Thanatos was granting him his wish, Sisyphus seized the opportunity and trapped Thanatos in the chains instead. Once Thanatos was bound by the strong chains, no one died on Earth, causing an uproar. Ares, the god of war, was annoyed that his battles had become less diverting because his opponents would not die. The exasperated Ares intervened, freeing Thanatos, enabling deaths to happen again, and turned Sisyphus over to him.[15] In some versions, Hades was sent to chain Sisyphus and was chained himself. As long as Hades was trapped, nobody could die. Consequently, sacrifices could not be made to the gods, and those that were old and sick were suffering. The gods finally threatened to make life so miserable for Sisyphus that he would wish he were dead. He then had no choice but to release Hades.[16] Before Sisyphus died, he had told his wife to throw his naked corpse into the middle of the public square (purportedly as a test of his wife's love for him). This caused Sisyphus to end up on the shores of the river Styx when he was brought to the underworld. Complaining to Persephone that this was a sign of his wife's disrespect for him, Sisyphus persuaded her to allow him to return to the upper world. Once back in Ephyra, the spirit of Sisyphus scolded his wife for not burying his body and giving it a proper funeral as a loving wife should. When Sisyphus refused to return to the underworld, he was forcibly dragged back there by Hermes.[17][18] In another version of the myth, Persephone was tricked by Sisyphus that he had been conducted to Tartarus by mistake, and so she ordered that he be released.[19] In Philoctetes by Sophocles, there is a reference to the father of Odysseus (rumoured to have been Sisyphus, and not Laërtes, whom we know as the father in the Odyssey) upon having returned from the dead.[clarification needed] Euripides, in Cyclops, also identified Sisyphus as Odysseus's father. |

統治 シーシュポスはエフィラ(コリントの旧称とされる)の創始者であり初代王であった。[8] パウサニアスによれば、彼は王位にある間、メリケルテスを称えてイストミア競技会を創設した。メリケルテスの遺体はイルカによってコリント地峡の岸辺に運 ばれたという。[13] ピンダロスの断片では、代わりにニンフたちの指示に従って(メリケルテスを称えて)競技会を創設したと記されている。[14] サルモネウスとの争い シシュフォスとその弟サルモネウスは互いに憎み合っていたことで知られており、シシュフォスはデルフォイの神託に、自身に重い罰が下ることなくサルモネウ スを殺す方法を相談した。ホメロス以降、シーシュポスは最も狡猾な男として名高い。サルモネウス殺害計画の一環で、彼はサルモネウスの娘ティロを誘惑し た。ところがティロは、シーシュポスがやがて父を廃位させるために自分たちの子供を利用しようとしていると知ると、その子供たちを殺してしまった。 死を欺く シーシュポスは、コリントのアクロポリスに泉を湧き出させる見返りに、アソポス川の神である父にアソポスの娘エギナの居場所を明かすことで、ゼウスの秘密を裏切った。[8] ゼウスはタナトスに命じ、シシュフォスをタルタロスに鎖で縛らせた。シシュフォスは、死者の魂を冥界へ導く役目を持つカロンが、なぜ今回は現れないのかと 不審に思った。シシュフォスは狡猾にも、タナトスに鎖の仕組みを見せてほしいと頼んだ。タナトスが彼の願いを聞き入れた瞬間、シシュフォスは機会を逃さ ず、逆にタナトスを鎖で縛り上げた。タナトスが強力な鎖で縛られると、地上では誰も死ななくなり、大騒ぎとなった。戦神アレスは、敵が死なないため戦いが 面白くなくなったことに腹を立てた。苛立ったアレスは介入し、タナトスを解放して再び死をもたらし、シシュフォスを彼に引き渡した。[15] 別の伝承では、ハデスがシーシュポスを鎖で縛りに行くが、逆に自らを縛られてしまう。ハデスが囚われている間は誰も死ねず、神々への生贄も捧げられず、老 いや病に苦悩する者たちが増えた。ついに神々は、シーシュポスに死を願うほどの人生を送りつけると脅した。彼は仕方なくハデスを解放した。[16] シシュフォスは死ぬ前に、妻に自分の裸の死体を公共広場の中央に投げ捨てるよう命じていた(妻の愛を試すためだという)。このため、冥界に連れて行かれた シシュフォスは、冥河の岸辺に流れ着くことになった。シシュフォスはペルセポネに、これは妻が自分を軽んじている証拠だと訴え、地上に戻ることを許すよう 説得した。エフィラに戻ったシシュフォスの霊は、妻が愛する妻として当然の義務である遺体の埋葬と葬儀を行わなかったことを叱責した。シシュフォスが冥界 へ戻ることを拒むと、ヘルメスに強制的に連れ戻された。[17][18] 別の神話では、シシュフォスがペルセポネを騙し、自分が誤ってタルタロスに連行されたと告げたため、彼女は彼の解放を命じたという。[19] ソフォクレスの『フィロクテテス』には、死から蘇ったオデュッセウスの父(オデュッセイアで父とされるレアルトスではなく、シシュフォスとの噂がある)への言及がある。[説明が必要] エウリピデスの『キュクロプス』でも、シシュフォスがオデュッセウスの父とされている。 |

| Punishment in the underworld As a punishment for his crimes, Hades made Sisyphus roll a huge boulder endlessly up a steep hill in Tartarus.[8][20][21] The maddening nature of the punishment was reserved for Sisyphus due to his hubristic belief that his cleverness surpassed that of Zeus himself. Hades accordingly displayed his own cleverness by enchanting the boulder into rolling away from Sisyphus before he reached the top which ended up consigning Sisyphus to an eternity of useless efforts and unending frustration. Thus, pointless or interminable activities are sometimes described as "Sisyphean". Sisyphus was a common subject for ancient writers and was depicted by the painter Polygnotus on the walls of the Lesche at Delphi.[22] |

冥界における罰 シシュフォスは自らの罪に対する罰として、ハデスによってタルタロスにある急峻な丘の上へ巨大な岩を永遠に転がし続けるよう命じられた。[8][20] [21] この狂気を誘う罰は、自らの知恵がゼウスをも凌ぐという傲慢な信念を抱いたシシュフォスにのみ与えられた。ハデスはこれに応じ、岩を魔法で操り、頂上に到 達する前にシシュフォスから転がって離れるように仕組んだ。その結果、シシュフォスは永遠に無益な努力と終わりのない苛立ちに苛まれることとなった。こう して、無意味あるいは終わりのない活動は時に「シシュフォスの労働」と形容されるようになった。シシュフォスは古代の作家たちにとって一般的な題材であ り、画家ポリグノトスによってデルフィのレスケの壁面に描かれた。[22] |

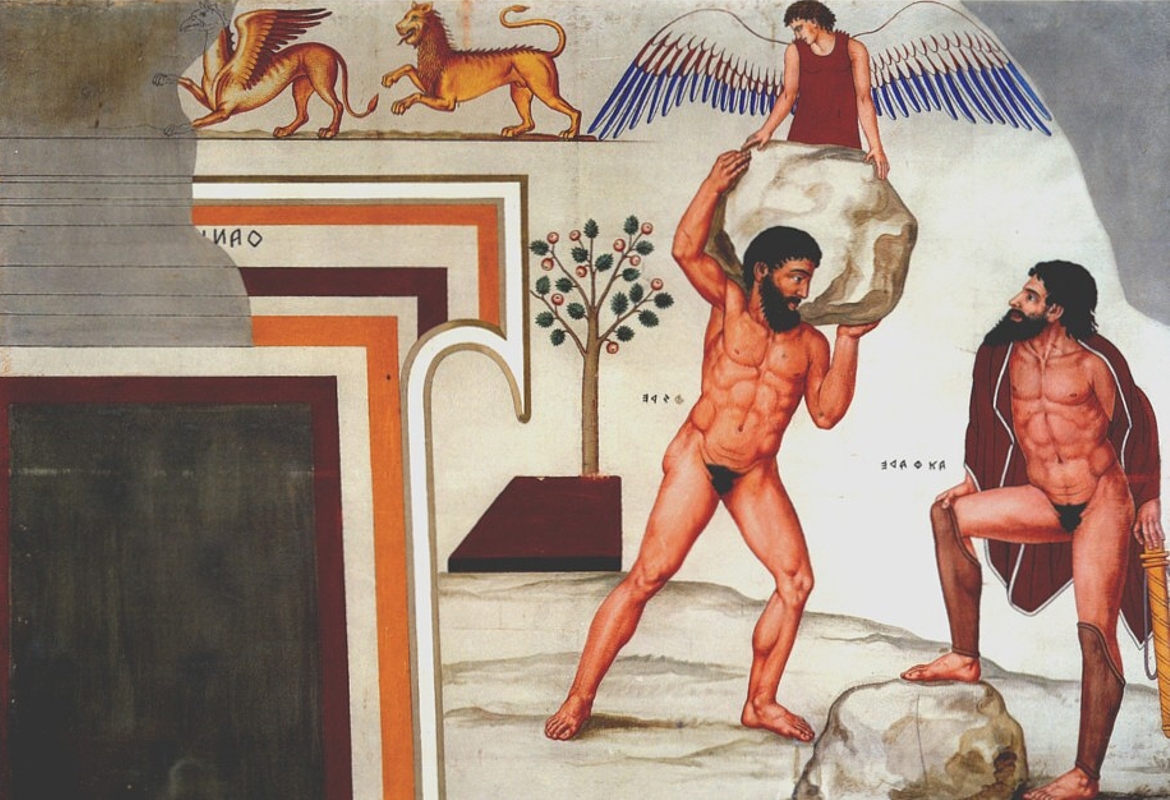

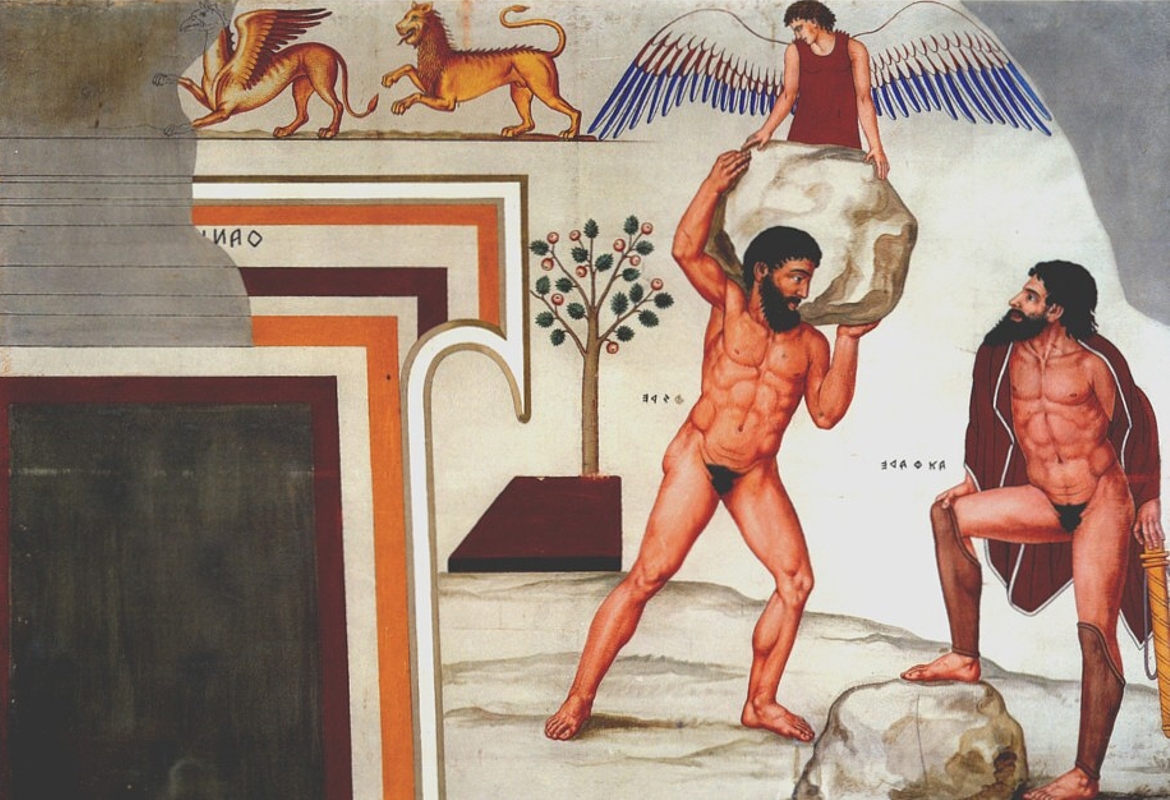

Sisyphus and Amphiaraus, copy of mural in François Tomb from Vulci made in 4th century BC |

シーシュポスとアンフィアラオス、紀元前4世紀にウルチで制作されたフランソワの墓の壁画の複製 |

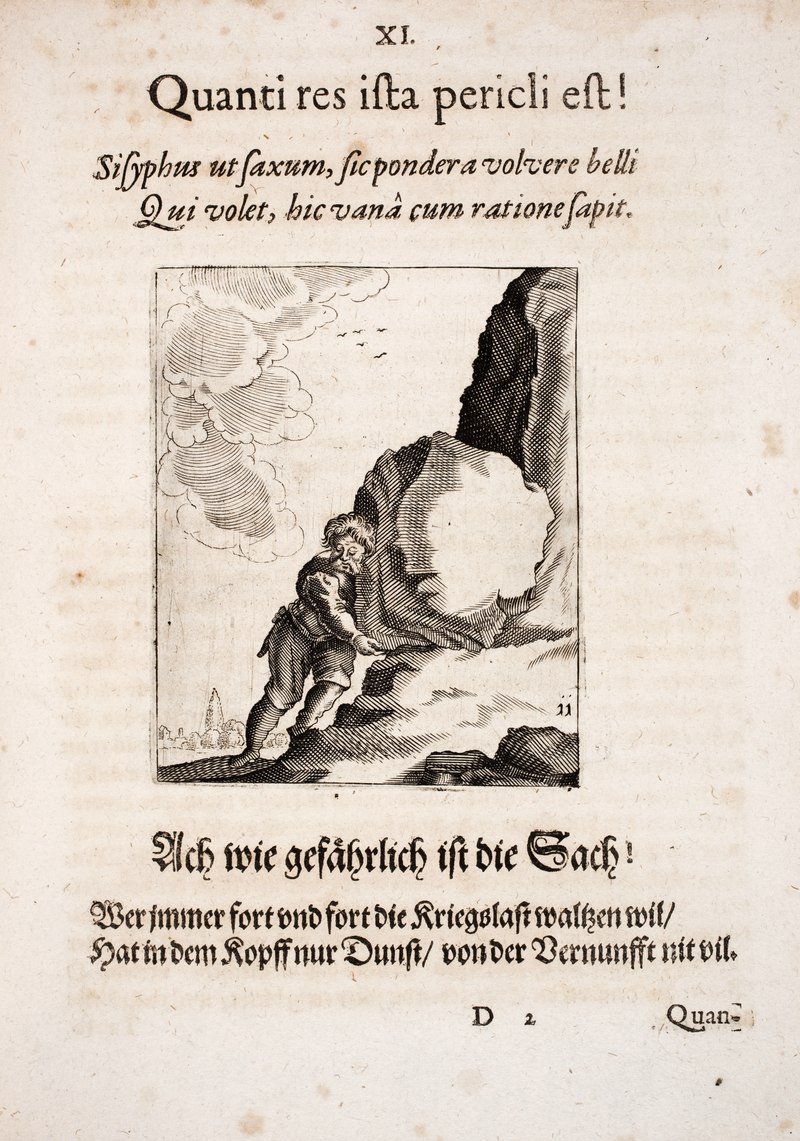

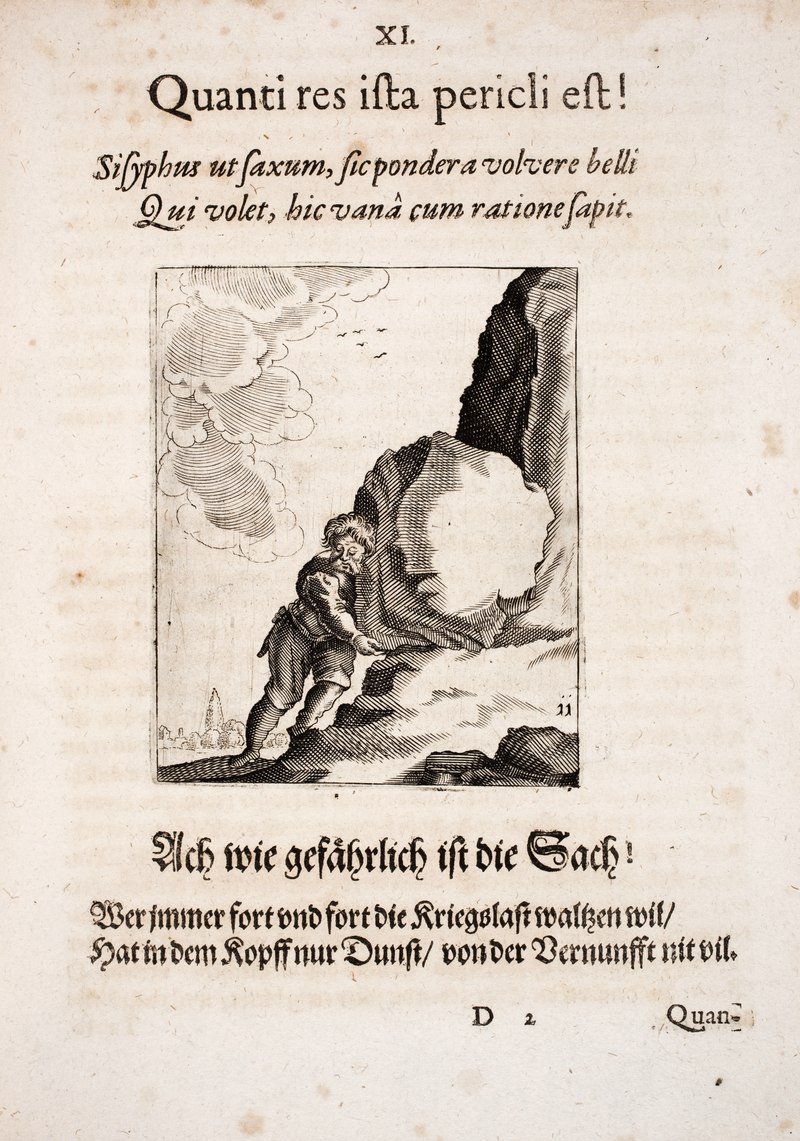

Interpretations Black and white etching of Sisyphus by Johann Vogel Sisyphus as a symbol for continuing a senseless war. Johann Vogel: Meditationes emblematicae de restaurata pace Germaniae, 1649 According to the solar theory, King Sisyphus is the disk of the sun that rises every day in the east and then sinks into the west.[23] Other scholars regard him as a personification of waves rising and falling, or of the treacherous sea.[23] The 1st-century BC Epicurean philosopher Lucretius interprets the myth of Sisyphus as personifying politicians aspiring for political office who are constantly defeated, with the quest for power, in itself an "empty thing", being likened to rolling the boulder up the hill.[24] Friedrich Welcker suggested that he symbolises the vain struggle of man in the pursuit of knowledge, and Salomon Reinach[25] that his punishment is based on a picture in which Sisyphus was represented rolling a huge stone Acrocorinthus, symbolic of the labour and skill involved in the building of the Sisypheum. Albert Camus, in his 1942 essay The Myth of Sisyphus, saw Sisyphus as personifying the absurdity of human life, but Camus concludes "one must imagine Sisyphus happy" as "The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man's heart." In his 1994 The Body of Myth, J. Nigro Sansonese,[26] building on the work of Georges Dumézil, speculates that the origin of the name "Sisyphus" is onomatopoetic of the continual back-and-forth, susurrant sound ("siss phuss") made by the breath in the nasal passages, situating the mythology of Sisyphus in a far larger context of archaic (see Proto-Indo-European religion) trance-inducing techniques related to breath control. The repetitive inhalation–exhalation cycle is described esoterically in the myth as an up–down motion of Sisyphus and his boulder on a hill. In experiments that test how workers respond when the meaning of their task is diminished, the test condition is referred to as the Sisyphusian condition. The two main conclusions of the experiment are that people work harder when their work seems more meaningful, and that people underestimate the relationship between meaning and motivation.[27] |

解釈 ヨハン・フォーゲル作 シシュフォスの白黒エッチング 無意味な戦争の継続を象徴するシシュフォス。ヨハン・フォーゲル『ドイツ和平回復に関する寓意的瞑想録』1649年 太陽説によれば、シシュフォス王は毎日東から昇り西に沈む太陽の円盤である。[23] 他の学者たちは彼を、打ち寄せては引く波、あるいは危険な海の擬人化と見なしている。[23] 紀元前1世紀のエピクロス派哲学者ルクレティウスは、シシュフォスの神話を、政治的地位を渇望しながら絶えず敗北する政治家たちの擬人化と解釈した。権力 への追求そのものが「空虚なもの」であることは、岩を丘の上へ転がす行為に例えられる。[24] フリードリヒ・ヴェルカーは、彼が知識追求における人間の虚しい闘争を象徴すると示唆した。またサロモン・レーナッハ[25]は、その罰はシシュフォスが アクロコリントスへ巨大な石を転がす図像に基づくものだと主張した。この石はシシュフォス神殿建設に要した労力と技術を象徴している。アルベール・カミュ は1942年の論文『シシュフォスの神話』で、シシュフォスを人間生活の虚無を体現する存在と見なした。しかしカミュは「頂点への闘いそのものが、人の心 を満たすのに十分である」として「シシュフォスは幸福であると想像せねばならない」と結論づけた。1994年の『神話の身体』において、J・ニグロ・サン ソネーゼ[26]はジョルジュ・デュメジルの研究を発展させ、「シーシュポス」という名の起源は、鼻腔内で息が作り出す絶え間ない往復する、ささやくよう な音(「シス・ファス」)の擬音語であると推測している。これによりシーシュポスの神話は、より広範な古代(プロト・インド・ヨーロッパ宗教参照)のトラ ンス状態の文脈に位置づけられる。鼻腔内の息が作り出すささやき声(「シッス・ファス」)の擬音語に由来すると推測している。これにより、シシュフォスの 神話は、呼吸制御に関連する原始的な(プロト・インド・ヨーロッパ宗教参照)トランス誘導技術というはるかに大きな文脈に位置づけられる。反復的な吸気・ 呼気のサイクルは、神話においてシシュフォスと岩の丘の上での上下運動として秘儀的に描写されている。 労働者が作業の意味を喪失した際の反応を検証する実験では、その試験条件を「シーシュポス的条件」と呼ぶ。実験の主な結論は二つある。作業に意味を見出せれば人はより懸命に働くこと、そして人は意味と動機付けの関係性を過小評価していることだ。[27] |

Literary interpretations Painting of Sisyphus by Titian Sisyphus (1548–49) by Titian, Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain Homer describes Sisyphus in both Book VI of the Iliad and Book XI of the Odyssey.[9][21] Ovid, the Roman poet, makes reference to Sisyphus in the story of Orpheus and Eurydice. When Orpheus descends and confronts Hades and Persephone, he sings a song so that they will grant his wish to bring Eurydice back from the dead. After this song is sung, Ovid shows how moving it was by noting that Sisyphus, emotionally affected for just a moment, stops his eternal task and sits on his rock, the Latin wording being inque tuo sedisti, Sisyphe, saxo ("and you sat, Sisyphus, on your rock").[28] In Plato's Apology, Socrates looks forward to the after-life where he can meet figures such as Sisyphus, who think themselves wise, so that he can question them and find who is wise and who "thinks he is when he is not."[29] Albert Camus, the French absurdist, wrote an essay entitled The Myth of Sisyphus, in which he elevates Sisyphus to the status of absurd hero. Franz Kafka repeatedly referred to Sisyphus as a bachelor; Kafkaesque for him were those qualities that brought out the Sisyphus-like qualities in himself. According to Frederick Karl: "The man who struggled to reach the heights only to be thrown down to the depths embodied all of Kafka's aspirations; and he remained himself, alone, solitary."[30] The philosopher Richard Clyde Taylor uses the myth of Sisyphus as a representation of a life made meaningless because it consists of bare repetition.[31] Wolfgang Mieder has collected cartoons that build on the image of Sisyphus, many of them editorial cartoons.[32] Hollis Robbins, reading Ovid against Camus, proposes that the punishment was not a punishment but a recognition and making legible of Sisyphus's essential nature: his compulsion to push against the rules.[33] |

文学的解釈 ティツィアーノ作『シーシュポス』 ティツィアーノ作『シーシュポス』(1548–49年)、プラド美術館(スペイン・マドリード)所蔵 ホメロスは『イリアス』第6巻と『オデュッセイア』第11巻の両方でシーシュポスについて記述している。 ローマの詩人オウィディウスは、オルフェウスとエウリュディケの物語の中でシーシュポスに言及している。オルフェウスが冥界に降りてハデスとペルセポネと 対峙した時、彼はエウリュディケを死から蘇らせる願いを叶えてもらうため、歌を歌った。この歌が歌われた後、オウィディウスはその感動の深さを示すため、 シシュフォスがほんのひととき感情に打たれ、永遠の作業を止めて岩の上に座り込んだ様子を描いている。ラテン語の原文は「inque tuo sedisti, Sisyphe, saxo」(「そしてお前は、シシュフォスよ、岩の上に座った」)である。[28] プラトンの『ソクラテスの弁明』では、ソクラテスは死後の世界を待ち望んでいる。そこでは、自分こそ賢者だと自負するシシュフォスのような人物と出会えるからだ。そうして彼らに問いかけ、真に賢い者と「賢いと思い込んでいるだけの者」を見極めようとするのである。[29] フランスの不条理主義者アルベール・カミュは『シシュフォスの神話』と題する随筆を書き、その中でシシュフォスを不条理の英雄として称えた。 フランツ・カフカは繰り返しシシュフォスを独身者と呼んだ。彼にとってカフカ的とは、自身の中にシシュフォスのような性質を引き出す特質を指した。 フレデリック・カールによれば「頂点に到達しようと苦闘しながらも深淵へと投げ落とされる男は、カフカのあらゆる願望を体現していた。そして彼はただ一 人、孤独なままだった」[30]。哲学者リチャード・クライド・テイラーは、シシュフォスの神話を、単なる反復に過ぎないために無意味化された人生の象徴 として用いている。 [31] ヴォルフガング・ミーダーは、シーシュポスのイメージを基にした風刺画を収集しており、その多くは社説漫画である。[32] ホリス・ロビンスは、カミュに対してオウィディウスを読み解き、この罰は罰ではなく、シーシュポスの本質的な性質、すなわち規則に逆らう衝動を認識し、可読化することだったと提案している。[33] |

| References Apollodorus, The Library with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website. Evslin, Bernard (2006). Gods, Demigods and Demons: A Handbook of Greek Mythology. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-84511-321-6. Retrieved 21 October 2020. Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2). Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-415-18636-0. Google Books. Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PhD in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library. Homer, The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website. Maehler, Herwig, Pindarus Carmina cum fragmentis. Pars II: Fragmenta. Indices, Bibliotheca Teubneriana, Munich and Leipzig, K. G. Saur Verlag, 1989. ISBN 3-598-71586-2. Morford, Mark P. O.; Lenardon, Robert J. (1999). Classical Mythology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514338-6. Retrieved 21 October 2020. Ovid, Metamorphoses translated by Brookes More (1859–1942). Boston, Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Ovid, Metamorphoses. Hugo Magnus. Gotha (Germany). Friedr. Andr. Perthes. 1892. Latin text available at the Perseus Digital Library. Pausanias, Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library Pausanias, Graeciae Descriptio. 3 vols. Leipzig, Teubner. 1903. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library. |

参考文献 アポロドーロス『神話大全』ジェームズ・ジョージ・フレイザー卿(F.B.A., F.R.S.)英訳、2巻、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ、ハーバード大学出版局;ロンドン、ウィリアム・ハイネマン社、1921年。ペルセウス・デジ タル図書館にてオンライン版公開。同サイトでギリシャ語原文も閲覧可能。 エヴスリン、バーナード(2006)。『神々、半神、悪魔:ギリシャ神話ハンドブック』。ブルームズベリー・アカデミック刊。ISBN 978-1-84511-321-6。2020年10月21日取得。 ガンツ、ティモシー、『初期ギリシャ神話:文学的・芸術的資料ガイド』、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学出版局、1996年、全2巻:ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9(第1巻)、ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3(第2巻)。 ハード、ロビン、『ラウトレッジ・ハンドブック ギリシャ神話:H.J.ローズ著「ギリシャ神話ハンドブック」に基づく』、サイコロジー・プレス、2004年。ISBN 978-0-415-18636-0。Google Books。 ホメロス『イリアス』A.T.マレー博士英訳、全2巻。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ、ハーバード大学出版局;ロンドン、ウィリアム・ハイネマン社、1924年。ペルセウス・デジタル・ライブラリにてオンライン版公開。 ホメロス『ホメロス作品集』全5巻。オックスフォード、オックスフォード大学出版局、1920年。ギリシャ語原文はペルセウス・デジタル・ライブラリにて閲覧可能。 ホメロス『オデュッセイア』A.T.マレー博士英訳、全2巻。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ、ハーバード大学出版局;ロンドン、ウィリアム・ハイネマン社、1919年。ペルセウス・デジタル・ライブラリにてオンライン版公開。同サイトでギリシャ語原文も閲覧可能。 マーラー、ヘルヴィヒ、『ピンダロス詩集と断片集。第二部:断片。索引付き』、テューブナー文庫、ミュンヘン・ライプツィヒ、K. G. ザウアー出版社、1989年。ISBN 3-598-71586-2。 モーフォード、マーク・P・O;レナードン、ロバート・J(1999年)。古典神話。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-514338-6。2020年10月21日取得。 オウィディウス『変身物語』、ブルックス・モア(1859–1942)訳。ボストン、コーンヒル出版会社、1922年。ペルセウス・デジタル・ライブラリでオンライン版が閲覧可能。 オウィディウス『変身物語』。ウーゴ・マグヌス。ゴータ(ドイツ)。フリードリヒ・アンドレアス・ペルテス社。1892年。ラテン語原文はペルセウス・デジタル・ライブラリで閲覧可能。 パウサニアス『ギリシア誌』。W.H.S.ジョーンズ博士(文学)及びH.A.オーメロッド修士による英訳、全4巻。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ、ハーバード大学出版局;ロンドン、ウィリアム・ハイネマン社。1918年。ペルセウス・デジタル・ライブラリ にてオンライン版公開。 パウサニアス『ギリシア誌』。全3巻。ライプツィヒ、テューブナー社。1903年。ギリシア語テキストはペルセウス・デジタル・ライブラリにて公開中。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sisyphus | |

リ ンク

文 献

その他の情報

Sisyphus. 1660-65. Antonio Zanchi. Italian

1631-1722. oil /canvas.

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆